Abstract

INTRODUCTION

By regulating cell fate, proliferation, and survival, Notch pathway signaling provides critical input into differentiation, organization, and function of multiple tissues. Notch signaling is also becoming an increasingly recognized feature in malignancy, including prostate cancer, where it may play oncogenic or tumor suppressive roles.

METHODS

Based on an electronic literature search from 2000 to 2013 we identified, summarized, and integrated published research on Notch signaling dynamics in prostate homeostasis and prostate cancer.

RESULTS

In benign prostate, Notch controls the differentiation state and architecture of the gland. In prostate cancer, similar features correlate with lethal potential and may be influenced by Notch. Increased Notch1 can confer a survival advantage on prostate cancer cells, and levels of Notch family members, such as Jagged2, Notch3, and Hes6 increase with higher cancer grade. However, Notch signaling can also antagonize growth and survival of both benign and malignant prostate cells, possibly through antagonistic effects of the Notch target HEY1 on androgen receptor function.

DISCUSSION

Notch signaling can dramatically influence prostate development and disease. Determining the cellular contexts where Notch promotes or suppresses prostate growth could open opportunities for diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Notch pathway, tumor progression, prostate cancer, active surveillance, targeted therapy

HOW NOTCH REGULATES CELL FATE AND TISSUE ORGANIZATION

General Roles for Notch in Biology

Named for the notched wing phenotype of mutant Drosophila and encoding a family of evolutionarily conserved cell surface receptors, Notch is one of the most widely studied pathways in biology [1]. Notch signaling has especially dramatic effects on cell fate, determining the shape and composition of organs and tissues throughout the animal [2]. For example, Notch signaling in intestinal stem cells favors enterocyte rather than endocrine differentiation [3], whereas in lymphopoietic precursors, Notch activation favors the development of T cell over B cell progeny [4]. These cell fate decisions typically occur in a specialized stem cell niche where stem cells and progeny monitor each other’s differentiation states. Notch signaling requires direct contact between the sending and receiving cells (see below), and is therefore well suited for this purpose.

GENERAL MECHANISMS OF NOTCH SIGNALING

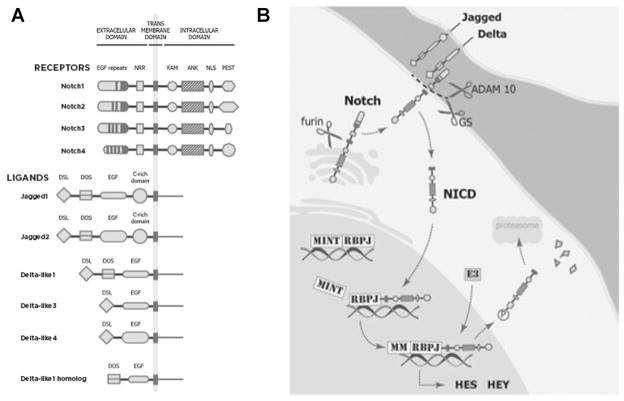

In mammals, the pathway is composed of four receptors (Notch1 through Notch4) and five ligands (Jagged1 and 2 and Delta-like 1, 3, and 4) (Fig. 1A). To initiate Notch signaling, a membrane-bound ligand on the sending cell binds to a receptor on the receiving cell. Ligand binding catalyzes a unique series of proteolytic cleavages that convert the full-length membrane-bound receptor into a smaller transcriptional transactivator, the notch intracellular domain (NICD), which is released from the cell surface and translates into the nucleus (Fig. 1B). NICDs bind to RBPJ/CBP transcription factors to activate Notch target genes [5], including those encoding transcriptional repressors belonging to the Hairy and enhancer of split (HES) and the Hairy/enhancer-of-split related with YRPW motif (HEY) protein families (Fig. 1B). Notably, these well-established pathway components have less well-known counter parts with emerging roles in the prostate. Two examples of particular interest are DLK1 and HES6. Delta-like 1 homolog (DLK1) is highly related to delta ligands, but lacks the Delta-Serrate-LAG-2 (DSL) activating domain and is therefore likely a naturally occurring antagonist of Notch signaling [6]. HES6 is structurally related to other HES family members, such as HES1, but is not a direct target of canonical Notch signaling. In fact, HES6 determines an opposite cell fate in neural stem cells compared to HES1, a well-established Notch target in neural progenitors [7,8].

Fig. 1.

A: Both ligands and receptors are single-pass transmembrane proteins composed of different structural domains. Ligands have an extracellular domain with three related structural motifs: 1) the Delta/Serrate/LAG-2 (DSL) motif; 2) the Delta and OSM-11-like protein (DOS) motif and 3) a third motif is composed of EGF-like repeats, both calcium binding and non calcium-binding, that can affect signaling efficiency. Jagged ligands also have a cytosine-rich (C-rich) domain. The extracellular domain of DLK1 has only a DOS motif and EGF repeats. The structure of the transmembrane and intracellular portions of the ligands remain largely unknown. Notch receptors have an extracellular domain that contains EGF-like repeats and a negative regulatory region, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular domain. The intracellular domain contains an RBPJ association module (RAM) that binds the transcription complex, a nuclear localization sequence (NLS), seven ankyrin repeats (ANK), and a proline (P)/glutamic acid (E)/serine (S)/threonine (T) (PEST) motif that targets the protein for degradation. B: The receptor is activated in a juxtacrine manner through its interaction with a ligand presented by an adjacent cell. Appropriate ligand binding produces a conformational change in the Notch receptor, exposing the extracellular domain for ADAM10 enzyme cleavage [92]. Subsequently, there is a second cleavage within the transmembrane domain [93], performed by the gamma-secretase (GS) complex. GS cleavage releases the active form of the receptor—Notch intracellular domain (NICD)—into the cytoplasm from which it translocates into the nucleus. Here NICD complexes with the DNA-binding transcription activator factor RBPJ (also known as CBF1 and CSL) to displace the transcriptional repressor Mint. This displacement facilitates the recruitment of activators such as Mastermind (MM) and thereby the transcription of pathway target genes. The main targets of the Notch pathway are two families of transcriptional repressors: the Hairy and enhancer of split (HES) and the Hairy/enhancer-of-split related with YRPW motif (HEY) proteins. Although it remains unknown if HES6 is a target of Notch pathway, recent studies reveal that HES6 may play an important role in prostate cancer progression. To quench Notch pathway activation, the NICD is phosphorylated on the PEST domain by E3 ubiquitin ligases, thereby targeting it for proteosomal degradation [94].

Research into Notch function in the prostate and other organs has been skewed toward Jagged1, Delta-like 1, and Notch1. Because members of these gene families can have opposite effects on signaling, more complete understanding of Notch function will require additional attention to other Notch receptors and ligands.

NOTCH PATHWAY IN CANCER

The T-ALL Link

Physiologic roles for the Notch pathway were established in the 1920s, but it took another 70 years to link genetic alterations that directly activate Notch signaling to cancer. In the 1990s, Ellisen et al. [9] found a translocation that generated a ligand-independent, autonomously activated form of the Notch receptor (NICD) in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) cells. Bringing together chromosomes 7 and 9, the translocation placed NICD under the transcriptional control of T-cell receptor β. By engineering the t(7,9) translocation into transgenic mice, Pear and colleagues demonstrated that NICD1 overexpression could cause leukemia [10]. Data from human patients show that NOTCH1 overexpression correlates with poor survival, although it derives only rarely from t(7,9) translocation. Instead, Notch1 activation usually occurs through mutations in the receptor that render it constitutively active and/or resistant to degradation [11,12]. These and other experiments laid the ground work for Notch signaling became a popular topic in cancer research with the ascendance of the idea that embryonic pathways may be reactivated in the development of cancer [13–15], and with the identification of Notch pathway expression in common solid tumors (Table I).

TABLE I.

A Partial List of Oncogenic and Tumor Suppressive Effects of Several Notch Pathway Members in Solid Tumors

| Tumor type | Notch pathway member | Role in tumor biology | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oncogenic | |||

| Mammary | JAGGED1 and JAGGED2 | Critical for breast cancer tumor progression and bone metastasis | [95,96] |

| NOTCH1 and NOTCH4 | In mouse mammary tumor virus models contributed to breast tumor cell initiation | [23,97–99] | |

| NOTCH1 and NOTCH2 | Gene rearrangements with MAST kinase family members confered tumor growth advantage | [18] | |

| Ovary cancer | JAGGED1, JAGGED2, NOTCH3 | Somatic mutations and copy number alterations were important for proliferation of ovarian cancer cells | [16] |

| Lung Cancer | NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 | NOTCH3 translocation in human lung cancers. NOTCH1 promoted tumor cell growth and survival through regulation of IGF pathway | [100,101] |

| Kidney | JAGGED1 and NOTCH1 | Pathway was constitutively active and promoted growth of renal cell carcinoma | [102] |

| Tumor suppressive | |||

| Head and neck | NOTCH1 | Exome sequencing revealed NOTCH1 inactivation suggesting it may function as a tumor suppressor gene | [103] |

| Skin | NOTCH1 | Deletion in keratinocytes caused skin cancer through microenviroment | [104] |

NOTCH IN SOLID TUMORS

Mechanisms of Notch Activation in Solid Tumors

Notch signaling can be aberrantly activated in tumor cells through different mechanisms, including genetic and epigenetic alterations or crosstalk with other oncogenic pathways. Over the last decade, several studies showed that DNA coding sequence alterations can activate Notch signaling in a variety of solid tumors. For example, ovary and breast cancers have somatic mutations, copy number alterations [16], amplifications [17], and gene rearrangements [18] implicating Notch pathway members in tumor pathophysiology. In addition, histone methylation, which regulates the dynamics of gene transcription can also induce Notch signaling during tumorigenesis [19]. Lastly, Notch can be activated by intracellular cross talk with other pathways. For example, Notch activation in a human B cell leukemia/lymphoma model resulted from direct activation of the gene encoding JAGGED2 ligand by the oncogenic transcription factor MYC [20]. Alternatively, Notch activity can be directly potentiated by other transcription factors. For example, in mouse cell lines hypoxia-inducible transcriptional factor 1 alpha (HIF1A) can directly bind to cleaved Notch receptors, modulate activation of Notch-responsive promoters, and increase the expression of Notch downstream targets [21]. Since both Myc and HIF1A have established roles in prostate cancer these alternative routes to Notch activation may play a role in the disease.

Effects of Notch Activation in Solid Tumors

Once activated, Notch signaling can promote cell growth in a variety of human solid tumors (Table I). Of these, breast (mammary gland) cancer has drawn the most attention and may serve as a paradigm for understanding the effects of Notch signaling. Enforced activation of Notch1 in transgenic mice disrupts mammary gland homeostasis—interfering with normal expansion, differentiation, and regression programs associated with pregnancy and lactation [22]. Enforced activation can also induce breast cancer, as shown by oncogenic activity of Notch1 in the mouse mammary gland [22–24]. In human breast cancers, high levels of JAGGED1 and NOTCH1 proteins have been linked to particularly aggressive cases [25]. The poor prognosis seen in these tumors may derive from a role for Notch in the development of drug-resistance. In particular, Notch signaling levels increase in cultured breast cancer cells that acquire resistance to endocrine therapy, such as the estrogen receptor antagonist tamoxifen, as well as to therapies targeting the EGFR axis, such as the HER2 receptor antagonist trastuzumab (Herceptin), and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antagonists gefitinib and lapatinib [26–29]. Within the heterogeneity of breast tumors, there are subpopulations of breast cancer stem cells that are responsible for tumor repopulation after chemotherapy and the generation of metastasis [30]. Although, resistant to chemotherapy, recent evidence shows that breast cancer stem cells are sensitive to HER2 targeting agents [31,32]. Moreover, breast cancer stem cells appear to rely on Notch signaling for survival and self-renewal [33,34]. In the laboratory, an exciting result of these interactions is that resistance to HER2 targeted therapy can be delayed or overcome by combining these agents with Notch antagonists (gamma secretase inhibitors), and effective dosing can be attained in vivo. If Notch function in other cancers is similar to that found in breast cancer, Notch antagonism might be useful in treating solid tumors that become resistant to targeted therapies, including therapies that target endocrine pathways. Given the central role of endocrine therapy in treating prostate cancer, this indication deserves further attention.

NOTCH SIGNALING IN THE PROSTATE

Notch Signaling in Prostate Development and Homeostasis

Prostate development is an excellent model system to study cell fate, and not surprisingly, Notch signaling has been studied in this context. Prior to discussing Notch in the prostate, we will first review general principles of prostate development and differentiation. The embryonic prostate rudiment is called the urogenital sinus (UGS). It begins as a simple epithelial-lined cavity surrounded by undifferentiated mesenchymal cells. At 10 weeks gestation in humans and at embryonic day 17.5 in mice, rising male hormone (androgen) levels initiate prostate formation by inducing the outgrowth of epithelial buds [35–37]. Through complex and carefully orchestrated proliferation, invasion, and differentiation, these buds evolve into complex glands. The shape and function of the gland, furthermore, require a series of cell-fate decisions that generate the main epithelial cell types, basal and luminal cells [38]. Each of these two cell types resides in a separate cell layer and contains stem cells capable of regenerating themselves as well as the cells in the other layer [39,40]. Transdifferentiation from basal to luminal phenotype appears to be the rule in humans [41,42], but may occur infrequently in experimental systems [43,44]. Notably, basal and luminal populations can each contribute the cell of origin for experimentally induced prostate cancers [40,43].

Notch signaling is induced during times of rapid prostate growth corresponding to the formation of the organ in the embryo and its regeneration upon exogenous androgen administration after castration. However, whether Notch promotes or restrains growth is controversial. One of the earliest mouse studies [45] showed that Notch1 mRNA was upregulated in embryonic and postnatal prostate epithelia and dramatically downregulated upon maturation of the gland. By visualizing green fluorescent protein (GFP) knocked into the Notch1 gene locus, this group further delineated Notch1 expression in the mouse prostate [45]. The investigators concluded that in mice Notch1 was concentrated in basal cells, however, by in situ hybridization, Notch1 appeared more luminal than basal. Despite this inconsistency, this study clearly demonstrated a dynamic expression pattern for Notch1 in prostate mice epithelium that coincided with key phases of organogenesis and epithelial differentiation.

In adult mice, the expression levels of the receptors and functional role of the pathway appear slightly different from those described during neonatal stage. Both basal and luminal cells express Notch ligands and receptors (Table II), but expression is higher in luminal cells. Engineering Notch activation in mouse prostate induces proliferation of luminal cells, but has the opposite effect on basal cells [46]. Luminal differentiation and proliferation are inter-related processes driven by androgen [47]. The opposite effects of driving Notch signaling in basal cells and luminal cells support a model wherein Notch ligands presented by basal epithelial cells activates the Notch pathway in adjacent luminal cells and by doing so, supports differentiation and proliferation [3].

TABLE II.

Expression of Notch Ligands and Receptor in Normal Prostate

| Notch member | Mouse

|

Human

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal layer | Luminal layer | Basal layer | Luminal layer | |

| Notch1 | + | + | + | + |

| Notch2 | + | + | − | − |

| Notch3 | − | + | − | − |

| Notch4 | − | − | − | − |

| Jagged1 | + | − | − | + |

| Jagged2 | + | − | − | − |

| Delta-like 1 | − | − | + | − |

The expression of other Delta-like ligands has not yet been described. The expression of Notch receptors and ligands in each layer is represented by (+), whereas (−) represents the absence of expression.

As mentioned above, during prostate development, androgens and signaling pathways such as Notch determine the differentiation states of cells in the prostate primordium. However, members of other pathways, namely transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) family members, can control Notch signaling. Doing so appears to be required to properly balance growth and branching of prostate glands. In investigating epithelial differentiation in the mouse prostate, Valdez and collaborators discovered a positive feedback loop between stromal TGFβ and Notch signaling in basal cells. This loop appears to diminish prostate growth by limiting basal cell proliferation. Another study using explants of mouse UGS supported a link between signaling by TGFβ family members and Notch inhibition by showing that the TGFβ family member Bone morphogenetic protein 7 (BMP7), decreases cleaved Notch1 and Hes1 expression in embryonic and postnatal prostate [48]. Interestingly, previous studies performed on mouse prostate suggest that Notch1 differentially regulates Hes1 and Hey1. In fact, conditional knockout of Notch1 gene in mouse prostate decreased Hey1 expression by half, but did not affect Hes1 levels [49]. Therefore, the capacity of BMP7 to disturb Notch signaling at the receptor and target levels demonstrates the importance of crosstalk between several pathways that orchestrate prostate development. Overall, Hey1 expression may be a better readout for Notch activation in the prostate than Hes1, but can modulate the action of Notch signaling on pathway targets.

Notch signaling may also play a role in the involution of the prostate that is seen upon androgen withdrawal following castration. Under these conditions, Notch1 expression rises [50]. Accordingly, pharmacologic or genetic Notch inhibition slowed prostate epithelial differentiation and accelerated proliferation [49]. Since adult male prostates encounter high levels of growth promoting hormones, growth suppression through Notch and/or TGFβ may be an important factor in limiting prostate overgrowth. If this finding were to be confirmed in human studies, enhancing Notch signaling could be used therapeutically to help control benign prostate hyperplasia, a major cause of morbidity in many older men.

However, unlike the mouse studies described above, subsequent work [51], in human tissue found that Notch signaling promoted prostate growth. In adult human tissue samples, expression of DLK1, a noncanonical Notch ligand that inhibits Notch signaling, was found in basal cells, whereas the NOTCH1 receptor and JAGGED1 ligand were co-expressed in luminal secretory cells. This arrangement suggested that the cell types sending and receiving Notch signals were switched in relation to the mouse. Using an antibody specific for activated NICD1, Notch signaling activity was detected in endothelial cells lining blood vessels, but not in epithelial cells, indicating that Notch was inactive in adult quiescent prostate. However, through expression of NOTCH1, mature human prostate epithelial cells had the capacity to activate the Notch signaling, whereas immature/stem cells used DLK1 to restrain the pathway. The investigators confirmed this scenario by studying prostate growth in a human organ culture model. In growing prostate epithelium, a cell type with features that were intermediate between basal and luminal cells emerged. In these intermediate cells, Notch was dramatically activated, with downregulation of the Notch inhibitor DLK1, as well as increased NOTCH1 and nuclear accumulation of its activated product, NICD1 [51]. Importantly, as demonstrated by culture with Notch antagonist (gamma secretase inhibitor, or GSI), Notch inhibition blocked human prostate epithelial cell growth [51]. This work indicates that studies to reconcile mouse and human functions for Notch signaling in the prostate will require additional focus on intermediate cells, a transient and relatively difficult cell type to study.

Studies by Thomson and colleagues shifted the focus to another cell type, prostate stromal cells, and their dramatic effects on Notch function in the prostate. In their studies, Notch modulation had modest effects on human prostate epithelial cells cultured alone, whereas Notch dramatically enhanced epithelial cell growth when co-cultured with human prostate cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs). Of additional interest, growth stimulation by CAFs could be blocked pharmacologically with a GSI or by engineering CAFs to express the endogenous Notch antagonist, DKL1 [52,53]. Most investigators study Notch function in isolated epithelial or cancer cells. However, these studies indicate that parallel investigation of stromal interactions will play a critical role in future efforts to unravel roles of Notch signaling in the prostate.

Aside from inattention to stromal interactions, why might the roles of Notch in prostate growth appear to switch polarity from one study to the next? Additional work will need to be carried out to answer this question, but it seems likely to be a question of experimental technique. An explanation may lie in the use of tissues at different stages of maturation by different groups. One group inhibited Notch in mouse postnatal prostate, at a time when many epithelial cells in the prostate had not yet matured [50]. Others used human mature prostates in these assays [51]. The observed data to date might fit a model in which Notch signaling drives proliferation and maturation in mature cells, but prevents these processes in immature cells.

Notch Suppresses Two Central Pathways in Prostate Development and Disease: Androgen Receptor and PI3K/AKT

Notch interacts with two signaling mechanisms that are central to prostate development, growth, homeostasis, and carcinogenesis: the androgen receptor (AR) pathway and the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3k)/Akt pathway [54,55]. AR signaling is sufficient to promote prostate growth and differentiation in the embryo and to support glandular homeostasis throughout adulthood. Androgen binding to AR in the cytoplasm induces receptor homodimerization and translocation to the nucleus. The homodimers bind to the DNA at specific regulatory elements and recruit coactivators (such as steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC1) and p300/CBP) to transcribe AR target genes [55]. Humans with genetic mutations that disrupt AR signaling do not develop a prostate and never get prostate cancer [56]. In the mouse prostate, AR activation induces carcinogenesis [57] and in advanced human cases, AR signaling is not only maintained, but it can become promiscuous—triggered by a variety of steroid hormones—or even ligand-independent. Thus, signaling by this pathway is a cardinal feature of prostate cancers, and interfering with AR signaling is one of the first examples of targeted therapy in oncology.

A recent study suggested a role for Notch in the acquisition of castration resistance. Belandia et al. [58] observed that the Notch target HEY1 directly bound the N-terminal activation domain of AR, suppressing androgen signaling. NICD also suppressed AR activity, was active in cells with different origins—myoblasts, prostate and breast cancer—and suppressed AR activity more effectively than HEY1 alone. The latter effect occurred most likely as a consequence of the induction of related transcriptional repressors, such as HES1 [58]. In contrast to these in vitro interactions between Notch and AR, the real process in the prostate may be more complex. Using immunohistochemistry, strong nuclear HEY1 staining was observed in benign prostate hyperplasia, but in prostate cancer this transcription factor localized only to the cytoplasm, indicating reduced nuclear activity of HEY1 in cancer and supporting the idea that cancers downregulate Notch signaling [58]. In the same study, however, AR always localized to the cell nucleus in both benign and malignant tissues [58]. Thus although HEY1 has the ability to inhibit AR signaling when expressed at high levels in cell lines, in actual human cancers, HEY1 appeared to be excluded from the nucleus, leaving AR free to transcribe its target genes.

PI3K/AKT activates growth and migration in the prostate [59,60]. This pathway is triggered when G protein-coupled or tyrosine kinase receptors activate PI3-Kinase. PI3K subsequently phosphorylates cell membrane proteins necessary for AKT binding so it can be phosphorylated by additional activating kinases. PI3K/AKT signaling is suppressed by the phosphatase activity of the Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), which is likely the most important tumor suppressor gene in the prostate. Deletions in PTEN gene and consequent deregulation of PI3K/mTOR signaling contribute to malignant transformation of prostate cells in vitro and in mouse models and are common features of advanced human prostate cancers [61–63]. Whelan et al. [64] found decreased expression of Notch1 in prostate cancer compared with benign prostate and further observed that NICD1 directly induced PTEN expression, resulting in diminished PI3K/AKT activity. These data support the possibility of a previously unrecognized tumor suppressive effect of Notch signaling, particularly when triggered by Notch1.

Interestingly, a reciprocal feedback mechanism has been recently described that links the PI3/AKT and AR pathways. Carver et al. [65] found that suppression of either pathway induces activity in the other. Thus, inactivation of PI3K/AKT lead to increased AR activity, whereas suppressing AR lead to increased PI3K/AKT. It is well established that PI3K/AKT signaling increases in advanced prostate cancer [66]. Thus, one might speculate that decreased Notch signaling can facilitate this increase.

NOTCH SIGNALING IN PROSTATE CANCER

Notch Pathway Expression and Function in Prostate Cancer Cell Lines

A number of studies agree on the expression of Notch components in prostate cancer cell lines [45,67]. However, the functional significance of Notch signaling in prostate cancer is controversial. Studies from different laboratories consistently detect high-level constitutive expression of NOTCH1 and NICD1 in all four frequently studied human prostate cancer cell lines (PC3, DU145, 22Rν1, and LNCaP) [45,67]. In these cells, knockdown of NOTCH1 levels by small interfering RNA can suppress malignant properties, including cell invasion [67], survival, and proliferation [68]. The latter result was surprising, given that earlier work had shown that Notch pathway activation, as achieved through engineered overexpression of NICD, also had a growth inhibitory effect [45]. One possible reason for both inhibition and activation of the pathway to inhibit growth is that Notch pathway activation could have different effects at different levels, a so-called “Goldilocks effect” [69]. Moderate Notch signaling could support growth whereas extreme levels of pathway activity (high or low) may inhibit growth. If this phenomenon were confirmed, it could magnify disparate results of studies that inhibit or activate Notch signaling, particularly if the methods used produced heterogeneous levels of pathway modulation in the cells under investigation.

Another potential contributor to different laboratories having different results stems from the vagaries of research using cultured cells. In particular, calcium levels vary significantly in different commonly used culture media components and can have dramatic effects on signaling pathways and on epithelial cell growth and differentiation [70]. Indeed, high levels of calcium can promote cell autonomous Notch receptor cleavage, producing the active NICD form without ligand presentation by adjacent cells [71]. These results indicate the need for additional studies that carefully titrate levels of Notch signaling while controlling for calcium levels and culture conditions. Until then, the roles of the pathway in prostate cancer are likely to remain controversial. In the meantime, examining research done on prostate cancer tissues might provide some insight.

Expression of Pathway Components in Prostate Cancer Tissue

Most studies demonstrate an upregulation of Notch pathway members in prostate cancer compared to benign tissue. In the TRansgenic Adenocarcinoma of the Mouse Prostate (TRAMP) model, Notch1 mRNA levels rose upon metastasis to regional lymph nodes [45], suggesting a role for the pathway in metastasis. In humans, however, an analysis of mRNA expression databases showed decreased mRNA levels of NOTCH1 and HEY1 in prostate cancer compared to benign glands [49]. Studies focusing on protein levels, in contrast have found increasing levels of Notch pathway members in human cancers along the progression spectrum. Using immunohistochemistry, Bin Hafeez et al. [67] found that levels of NOTCH1 protein increased with increasing Gleason grade. Their finding that NOTCH1 levels were particularly high in cancer cells surrounding capillaries provided further support to the idea that Notch signaling might enhance the ability of such cells to escape into the bloodstream and metastasize. Indeed, when compared to localized tumor or benign tissue, metastases showed distinctly elevated levels of JAGGED1 protein [72], mirroring findings in TRAMP mice (see above). Intriguingly, tumors with highest levels of JAGGED1 were least likely to be cured by radical prostatectomy, suggesting that JAGGED1 contributes to the ability of these cancers to metastasize prior to surgery. Thus, bearing in mind contradictory evidence in mice [45], the preponderance of evidence supports upregulation rather than downregulation of Notch components with human prostate cancer progression. While far from proof, this increased level of pathway expression is consistent with a functional role for Notch in prostate cancer progression. Approaches to further explore Notch function in this disease could include conditional knockout of Notch pathway members in mouse models of prostate cancer and trials of Notch antagonists in prostate cancer-bearing mice and humans (see below).

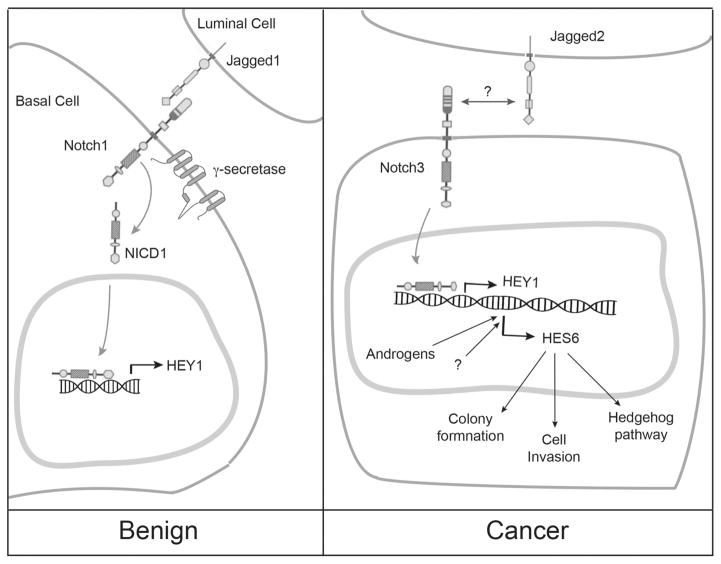

Notch Pathway Members Distinguish High Grade From Low Grade Prostate Cancers and Serve as Biomarkers to Improve Biopsy Accuracy

When considering the potential function of any signaling pathway in prostate cancer, it is useful to do so in the context of Gleason Grade. In particular, it is only Gleason grades of 7 and above that have the potential to metastasize and kill [73,74]. Thus, when properly evaluated (i.e., through comprehensive examination of a surgically removed prostate gland), the Gleason grade accurately distinguishes between indolent from aggressive prostate cancers. Unfortunately, biopsies often do not accurately distinguish indolent cancers from their more aggressive counterparts [75,76], leading to frequent “overtreatment” of cancers that do not warrant treatment. At the other end of the spectrum, regardless of primary treatment, high-grade tumors can rapidly recur and kill patients. Expression profiling studies indicate that members of the Notch pathway are distinctive features of aggressive prostate cancers with high Gleason grade. For example, comparing gene expression profiles from purely high-grade (Gleason 4 + 4 =8) versus purely low-grade (Gleason 3 + 3 =6) microdissected cancer cells, Notch signaling was the foremost distinguishing feature [77]. This observation was confirmed in a meta-analysis using gene profiling data form other laboratories [77–79]. In particular, cancer cells with metastatic potential (Gleason 4 + 4 =8) upregulated the Notch ligand JAGGED2, the NOTCH3 receptor, and the potential Notch target gene, Hairy enhancer of split family member, HES6 [77] (Fig. 2). Thus, a particular Notch ligand, receptor, and response gene, appeared to distinguish aggressive prostate cancers. The arrangement of these components into a potential signaling cascade suggests that the pathway is functional in aggressive prostate cancers.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of possible Notch signaling dynamics in benign and malignant (cancer) prostate cells.

These findings raise new questions regarding potential uses of Notch pathway members as diagnostic and therapeutic targets in prostate cancer. One such question is whether Notch signaling might be a useful drug target in aggressive prostate cancers.

NOTCH PATHWAY INHIBITORS

Gamma-Secretase Inhibitors

The compounds most widely used to inhibit Notch pathway activity are gamma-secretase inhibitors (GSIs). These drugs were initially developed in an effort to reduce amyloid-β protein aggregates in Alzheimer’s disease. GSIs were subsequently found to be an attractive potential treatment for cancers involving active Notch signaling. Initially tested in T-ALL lines and later in prostate, breast, and lung cell lines and xenografts, GSI treatment was found suppress cancer growth [12,26,68,80,81]. In early mouse studies, it quickly became evident that these drugs caused toxicity in Notch-dependent tissues, particularly the gastrointestinal tract and the thymus [82,83]. However, alternative dosing strategies have been found to limit this toxicity. For example, intermittent dosing, as well as co-administration of dexamethasone has been shown to reduce gastrointestinal toxicity in animals exposed to GSIs without compromising anti-tumor effects [84,85].

Selective Notch Inhibitors

More precisely targeted approaches have emerged to selectively shut down the Notch pathway. By focusing on individual ligands or receptors, these agents have the potential to avoid side effects associated with pan-Notch inhibition [86]. Antibodies binding the receptors Notch1 and Notch2, and the ligand Delta-like 4, have been used experimentally and shown to inhibit cancer cell proliferation with minimal intestinal toxicity [87,88]. These approaches rely on cancer cells having relatively more stringent requirements for the targeted ligand or receptor compared to intestinal enterocytes. A second approach utilized synthetic peptides that inhibit Notch1 from engaging the transcriptional machinery. Stabilized alpha-helical peptides have been produced that can specifically block NICD1 binding to RBPJ. Used in vivo in a Notch1 driven mouse leukemia model, these peptides repressed Notch1 target gene expression and leukemogenesis while avoiding gastrointestinal toxicity [89]. This agent could have lower toxicity than GSIs because it does not affect signaling by other Notch receptors (Notch2, 3, or 4), or because it spares other GSI targets outside of the Notch pathway. Ultimately, it will be critical to explore whether cancer cells and enterocytes have differential requirements for signaling by each of the 4 Notch receptors. These differential requirements may form the basis for enhancing the therapeutic index of strategies to more safely and effectively target Notch signaling.

Clinical Trials With Notch Inhibitors

There are currently 28 clinical trials registered at the NIH recruiting patients to study the effects of Notch inhibitors, mainly GSI, in cancer. Among these, there is one specific for prostate cancer patients: it combines the anti-androgen bicalutamide with a GSI in patients whose cancers recur after surgery (prostatectomy) or prostate radiation. There are another seven trials recruiting patients with unspecified metastatic solid tumors that can enroll patients with prostate cancer. Results from two Phase I clinical trials with escalate doses of GSI recently published reported that these drugs were well tolerated and there was potential clinical benefit in brain tumor (glioma), colorectal adenocarcinoma and melanoma patients [90,91]. No benefits, however, have been reported for prostate cancer patients. As mentioned above, the lack of consistent experimental data about the role of Notch on prostate cancer makes it difficult to predict the therapeutic effects of GSIs or to pinpoint the types of patients that will benefit most from these drugs. A better understanding of differential activities of individual Notch ligands and receptors—within the pathway and in interactions with other pathways—will reveal whether these drugs should be added to the therapeutic armamentarium of prostate cancer and how best to do so.

CONCLUSION

Evidence increasingly supports the notion that the Notch pathway interacts with many different signaling cascades to regulate critical cellular processes in both normal and neoplastic tissues. In the prostate, there is evidence that Notch is important for the normal development of the gland and that its deregulation is a feature of tumorigenesis. It remains unclear, however, whether the pathway stimulates or inhibits prostate cancer progression. Thus, despite the emergence of effective and non-toxic inhibitors of Notch signaling, it is not currently clear what to expect when these agents are used in prostate cancer patients. Future studies should clarify this critically important issue. In the meantime, the pathway appears to be upregulated in more aggressive prostate cancers compared to indolent cases. This differential expression pattern could be exploited in selecting patients who need treatment as opposed to those who can be maintained in active surveillance programs.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: Fundação para Ciência e Tecnologia; Grant number: SFRH/BD/69819/2010.

This study was supported by PhD grant from Fundação para Ciência e Tecnologia (SFRH/BD/69819/2010 to F.L.F.C.).

References

- 1.Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Muskavitch MA. Notch: The past, the present, and the future. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;92:1–29. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)92001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ. Notch signaling: Cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;284(5415):770–776. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohlstein B, Spradling A. Multipotent Drosophila intestinal stem cells specify daughter cell fates by differential notch signaling. Science. 2007;315(5814):988–992. doi: 10.1126/science.1136606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radtke F, Wilson A, Stark G, Bauer M, van Meerwijk J, MacDonald HR, Aguet M. Deficient T cell fate specification in mice with an induced inactivation of Notch1. Immunity. 1999;10(5):547–558. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hori K, Sen A, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Notch signaling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 10):2135–2140. doi: 10.1242/jcs.127308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falix FA, Aronson DC, Lamers WH, Gaemers IC. Possible roles of DLK1 in the Notch pathway during development and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822(6):988–995. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jhas S, Ciura S, Belanger-Jasmin S, Dong Z, Llamosas E, Theriault FM, Joachim K, Tang Y, Liu L, Liu J, Stifani S. Hes6 inhibits astrocyte differentiation and promotes neurogenesis through different mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2006;26(43):11061–11071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1358-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaiano N, Fishell G. The role of notch in promoting glial and neural stem cell fates. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:471–490. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.030702.130823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellisen LW, Bird J, West DC, Soreng AL, Reynolds TC, Smith SD, Sklar J. TAN-1, the human homolog of the Drosophila notch gene, is broken by chromosomal translocations in T lymphoblastic neoplasms. Cell. 1991;66(4):649–661. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90111-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pear WS, Aster JC, Scott ML, Hasserjian RP, Soffer B, Sklar J, Baltimore D. Exclusive development of T cell neoplasms in mice transplanted with bone marrow expressing activated Notch alleles. J Exp Med. 1996;183(5):2283–2291. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu YM, Zhao WL, Fu JF, Shi JY, Pan Q, Hu J, Gao XD, Chen B, Li JM, Xiong SM, Gu LJ, Tang JY, Liang H, Jiang H, Xue YQ, Shen ZX, Chen Z, Chen SJ. NOTCH1 mutations in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Prognostic significance and implication in multifactorial leukemogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(10):3043–3049. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, Morris JPt, Silverman LB, Sanchez-Irizarry C, Blacklow SC, Look AT, Aster JC. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306(5694):269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beachy PA, Karhadkar SS, Berman DM. Tissue repair and stem cell renewal in carcinogenesis. Nature. 2004;432(7015):324–331. doi: 10.1038/nature03100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taipale J, Beachy PA. The Hedgehog and Wnt signalling pathways in cancer. Nature. 2001;411(6835):349–354. doi: 10.1038/35077219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414(6859):105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474(7353):609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park JT, Li M, Nakayama K, Mao TL, Davidson B, Zhang Z, Kurman RJ, Eberhart CG, Shih Ie M, Wang TL. Notch3 gene amplification in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66(12):6312–6318. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson DR, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Wu YM, Shankar S, Cao X, Ateeq B, Asangani IA, Iyer M, Maher CA, Grasso CS, Lonigro RJ, Quist M, Siddiqui J, Mehra R, Jing X, Giordano TJ, Sabel MS, Kleer CG, Palanisamy N, Natrajan R, Lambros MB, Reis-Filho JS, Kumar-Sinha C, Chinnaiyan AM. Functionally recurrent rearrangements of the MAST kinase and Notch gene families in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2011;17(12):1646–1651. doi: 10.1038/nm.2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liefke R, Oswald F, Alvarado C, Ferres-Marco D, Mittler G, Rodriguez P, Dominguez M, Borggrefe T. Histone demethylase KDM5A is an integral part of the core Notch-RBP-J repressor complex. Genes Dev. 2010;24(6):590–601. doi: 10.1101/gad.563210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yustein JT, Liu YC, Gao P, Jie C, Le A, Vuica-Ross M, Chng WJ, Eberhart CG, Bergsagel PL, Dang CV. Induction of ectopic Myc target gene JAG2 augments hypoxic growth and tumorigenesis in a human B-cell model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(8):3534–3539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901230107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gustafsson MV, Zheng X, Pereira T, Gradin K, Jin S, Lundkvist J, Ruas JL, Poellinger L, Lendahl U, Bondesson M. Hypoxia requires notch signaling to maintain the undifferentiated cell state. Dev Cell. 2005;9(5):617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu C, Dievart A, Lupien M, Calvo E, Tremblay G, Jolicoeur P. Overexpression of activated murine Notch1 and Notch3 in transgenic mice blocks mammary gland development and induces mammary tumors. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(3):973–990. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dievart A, Beaulieu N, Jolicoeur P. Involvement of Notch1 in the development of mouse mammary tumors. Oncogene. 1999;18(44):5973–5981. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Politi K, Feirt N, Kitajewski J. Notch in mammary gland development and breast cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14(5):341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reedijk M, Odorcic S, Chang L, Zhang H, Miller N, McCready DR, Lockwood G, Egan SE. High-level coexpression of JAG1 and NOTCH1 is observed in human breast cancer and is associated with poor overall survival. Cancer Res. 2005;65(18):8530–8537. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rizzo P, Miao H, D’Souza G, Osipo C, Song LL, Yun J, Zhao H, Mascarenhas J, Wyatt D, Antico G, Hao L, Yao K, Rajan P, Hicks C, Siziopikou K, Selvaggi S, Bashir A, Bhandari D, Marchese A, Lendahl U, Qin JZ, Tonetti DA, Albain K, Nickol-off BJ, Miele L. Cross-talk between notch and the estrogen receptor in breast cancer suggests novel therapeutic approaches. Cancer Res. 2008;68(13):5226–5235. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandya K, Meeke K, Clementz AG, Rogowski A, Roberts J, Miele L, Albain KS, Osipo C. Targeting both Notch and ErbB-2 signalling pathways is required for prevention of ErbB-2-positive breast tumour recurrence. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(6):796–806. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piechocki MP, Yoo GH, Dibbley SK, Lonardo F. Breast cancer expressing the activated HER2/neu is sensitive to gefitinib in vitro and in vivo and acquires resistance through a novel point mutation in the HER2/neu. Cancer Res. 2007;67(14):6825–6843. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osipo C, Patel P, Rizzo P, Clementz AG, Hao L, Golde TE, Miele L. ErbB-2 inhibition activates Notch-1 and sensitizes breast cancer cells to a gamma-secretase inhibitor. Oncogene. 2008;27(37):5019–5032. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu S, Wicha MS. Targeting breast cancer stem cells. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(25):4006–4012. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korkaya H, Paulson A, Iovino F, Wicha MS. HER2 regulates the mammary stem/progenitor cell population driving tumorigenesis and invasion. Oncogene. 2008;27(47):6120–6130. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korkaya H, Wicha MS. HER2 and breast cancer stem cells: More than meets the eye. Cancer Res. 2013;73(12):3489–3493. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrison H, Farnie G, Brennan KR, Clarke RB. Breast cancer stem cells: Something out of notching? Cancer Res. 2010;70(22):8973–8976. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pannuti A, Foreman K, Rizzo P, Osipo C, Golde T, Osborne B, Miele L. Targeting Notch to target cancer stem cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(12):3141–3152. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P, Santti R, Pelliniemi LJ. Correlation of early cytodifferentiation of the human fetal prostate and Leydig cells. Anat Rec. 1980;196(3):263–273. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091960302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Timms BG, Mohs TJ, Didio LJ. Ductal budding and branching patterns in the developing prostate. J Urol. 1994;151(5):1427–1432. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35273-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cunha GR. The role of androgens in the epithelio-mesenchymal interactions involved in prostatic morphogenesis in embryonic mice. Anat Rec. 1973;175(1):87–96. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091750108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Hayward S, Cao M, Thayer K, Cunha G. Cell differentiation lineage in the prostate. Differentiation. 2001;68(4–5):270–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2001.680414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leong KG, Wang BE, Johnson L, Gao WQ. Generation of a prostate from a single adult stem cell. Nature. 2008;456(7223):804–808. doi: 10.1038/nature07427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X, Kruithof-de Julio M, Economides KD, Walker D, Yu H, Halili MV, Hu YP, Price SM, Abate-Shen C, Shen MM. A luminal epithelial stem cell that is a cell of origin for prostate cancer. Nature. 2009;461(7263):495–500. doi: 10.1038/nature08361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blackwood JK, Williamson SC, Greaves LC, Wilson L, Rigas AC, Sandher R, Pickard RS, Robson CN, Turnbull DM, Taylor RW, Heer R. In situ lineage tracking of human prostatic epithelial stem cell fate reveals a common clonal origin for basal and luminal cells. J Pathol. 2011;225(2):181–188. doi: 10.1002/path.2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaisa NT, Graham TA, McDonald SA, Poulsom R, Heidenreich A, Jakse G, Knuechel R, Wright NA. Clonal architecture of human prostatic epithelium in benign and malignant conditions. J Pathol. 2011;225(2):172–180. doi: 10.1002/path.2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi N, Zhang B, Zhang L, Ittmann M, Xin L. Adult murine prostate basal and luminal cells are self-sustained lineages that can both serve as targets for prostate cancer initiation. Cancer Cell. 2012;21(2):253–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ousset M, Van Keymeulen A, Bouvencourt G, Sharma N, Achouri Y, Simons BD, Blanpain C. Multipotent and unipotent progenitors contribute to prostate postnatal development. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(11):1131–1138. doi: 10.1038/ncb2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shou J, Ross S, Koeppen H, de Sauvage FJ, Gao WQ. Dynamics of notch expression during murine prostate development and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61(19):7291–7297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valdez JM, Zhang L, Su Q, Dakhova O, Zhang Y, Shahi P, Spencer DM, Creighton CJ, Ittmann MM, Xin L. Notch and TGFbeta form a reciprocal positive regulatory loop that suppresses murine prostate basal stem/progenitor cell activity. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11(5):676–688. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martinez HD, Hsiao JJ, Jasavala RJ, Hinkson IV, Eng JK, Wright ME. Androgen-sensitive microsomal signaling networks coupled to the proliferation and differentiation of human prostate cancer cells. Genes Cancer. 2011;2(10):956–978. doi: 10.1177/1947601912436422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grishina IB, Kim SY, Ferrara C, Makarenkova HP, Walden PD. BMP7 inhibits branching morphogenesis in the prostate gland and interferes with Notch signaling. Dev Biol. 2005;288(2):334–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang XD, Leow CC, Zha J, Tang Z, Modrusan Z, Radtke F, Aguet M, de Sauvage FJ, Gao WQ. Notch signaling is required for normal prostatic epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation. Dev Biol. 2006;290(1):66–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang XD, Shou J, Wong P, French DM, Gao WQ. Notch1-expressing cells are indispensable for prostatic branching morphogenesis during development and re-growth following castration and androgen replacement. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(23):24733–24744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401602200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ceder JA, Jansson L, Helczynski L, Abrahamsson PA. Delta-like 1 (Dlk-1), a novel marker of prostate basal and candidate epithelial stem cells, is downregulated by notch signalling in intermediate/transit amplifying cells of the human prostate. Eur Urol. 2008;54(6):1344–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orr B, Grace OC, Vanpoucke G, Ashley GR, Thomson AA. A role for notch signaling in stromal survival and differentiation during prostate development. Endocrinology. 2009;150(1):463–472. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Orr B, Grace OC, Brown P, Riddick AC, Stewart GD, Franco OE, Hayward SW, Thomson AA. Reduction of pro-tumorigenic activity of human prostate cancer-associated fibroblasts using Dlk1 or SCUBE1. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6(2):530–536. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. Molecular genetics of prostate cancer: New prospects for old challenges. Genes Dev. 2010;24(18):1967–2000. doi: 10.1101/gad.1965810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sarker D, Reid AH, Yap TA, de Bono JS. Targeting the PI3K/AKT pathway for the treatment of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(15):4799–4805. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Batch JA, Williams DM, Davies HR, Brown BD, Evans BA, Hughes IA, Patterson MN. Androgen receptor gene mutations identified by SSCP in fourteen subjects with androgen insensitivity syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1992;1(7):497–503. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.7.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Han G, Foster BA, Mistry S, Buchanan G, Harris JM, Tilley WD, Greenberg NM. Hormone status selects for spontaneous somatic androgen receptor variants that demonstrate specific ligand and cofactor dependent activities in autochthonous prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(14):11204–11213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Belandia B, Powell SM, Garcia-Pedrero JM, Walker MM, Bevan CL, Parker MG. Hey1, a mediator of notch signaling, is an androgen receptor corepressor. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(4):1425–1436. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.4.1425-1436.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ghosh S, Lau H, Simons BW, Powell JD, Meyers DJ, De Marzo AM, Berman DM, Lotan TL. PI3K/mTOR signaling regulates prostatic branching morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2011;360(2):329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stiles B, Groszer M, Wang S, Jiao J. Wu H. PTENless means more Dev Biol. 2004;273(2):175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Davies MA, Koul D, Dhesi H, Berman R, McDonnell TJ, McConkey D, Yung WK, Steck PA. Regulation of Akt/PKB activity, cellular growth, and apoptosis in prostate carcinoma cells by MMAC/PTEN. Cancer Res. 1999;59(11):2551–2556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang S, Gao J, Lei Q, Rozengurt N, Pritchard C, Jiao J, Thomas GV, Li G, Roy-Burman P, Nelson PS, Liu X, Wu H. Prostate-specific deletion of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene leads to metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;4(3):209–221. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McMenamin ME, Soung P, Perera S, Kaplan I, Loda M, Sellers WR. Loss of PTEN expression in paraffin-embedded primary prostate cancer correlates with high Gleason score and advanced stage. Cancer Res. 1999;59(17):4291–4296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whelan JT, Kellogg A, Shewchuk BM, Hewan-Lowe K, Ber-trand FE. Notch-1 signaling is lost in prostate adenocarcinoma and promotes PTEN gene expression. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107(5):992–1001. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carver BS, Chapinski C, Wongvipat J, Hieronymus H, Chen Y, Chandarlapaty S, Arora VK, Le C, Koutcher J, Scher H, Scardino PT, Rosen N, Sawyers CL. Reciprocal feedback regulation of PI3K and androgen receptor signaling in PTEN-deficient prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(5):575–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lotan TL, Gurel B, Sutcliffe S, Esopi D, Liu W, Xu J, Hicks JL, Park BH, Humphreys E, Partin AW, Han M, Netto GJ, Isaacs WB, De Marzo AM. PTEN protein loss by immunostaining: Analytic validation and prognostic indicator for a high risk surgical cohort of prostate cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(20):6563–6573. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bin Hafeez B, Adhami VM, Asim M, Siddiqui IA, Bhat KM, Zhong W, Saleem M, Din M, Setaluri V, Mukhtar H. Targeted knockdown of Notch1 inhibits invasion of human prostate cancer cells concomitant with inhibition of matrix metallopro-teinase-9 and urokinase plasminogen activator. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(2):452–459. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Y, Wang Z, Ahmed F, Banerjee S, Li Y, Sarkar FH. Down-regulation of Jagged-1 induces cell growth inhibition and S phase arrest in prostate cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(9):2071–2077. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Drabick JJ, Schell TD. Poking CD40 for cancer therapy, another example of the Goldilocks effect. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10(10):994–996. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.10.13976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hager B, Bickenbach JR, Fleckman P. Long-term culture of murine epidermal keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;112(6):971–976. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dalrymple S, Antony L, Xu Y, Uzgare AR, Arnold JT, Savaugeot J, Sokoll LJ, De Marzo AM, Isaacs JT. Role of notch-1 and E-cadherin in the differential response to calcium in culturing normal versus malignant prostate cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(20):9269–9279. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Santagata S, Demichelis F, Riva A, Varambally S, Hofer MD, Kutok JL, Kim R, Tang J, Montie JE, Chinnaiyan AM, Rubin MA, Aster JC. JAGGED1 expression is associated with prostate cancer metastasis and recurrence. Cancer Res. 2004;64(19):6854–6857. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Han M, Partin AW, Pound CR, Epstein JI, Walsh PC. Long-term biochemical disease-free and cancer-specific survival following anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy. The 15-year Johns Hopkins experience. Urol Clin North Am. 2001;28(3):555–565. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stephenson AJ, Kattan MW, Eastham JA, Bianco FJ, Jr, Yossepowitch O, Vickers AJ, Klein EA, Wood DP, Scardino PT. Prostate cancer-specific mortality after radical prostatectomy for patients treated in the prostate-specific antigen era. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(26):4300–4305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Davies JD, Aghazadeh MA, Phillips S, Salem S, Chang SS, Clark PE, Cookson MS, Davis R, Herrell SD, Penson DF, Smith JA, Jr, Barocas DA. Prostate size as a predictor of Gleason score upgrading in patients with low risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 2011;186(6):2221–2227. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kvale R, Moller B, Wahlqvist R, Fossa SD, Berner A, Busch C, Kyrdalen AE, Svindland A, Viset T, Halvorsen OJ. Concordance between Gleason scores of needle biopsies and radical prostatectomy specimens: A population-based study. BJU Int. 2009;103(12):1647–1654. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ross AE, Marchionni L, Vuica-Ross M, Cheadle C, Fan J, Berman DM, Schaeffer EM. Gene expression pathways of high grade localized prostate cancer. Prostate. 2011;25:1–11. doi: 10.1002/pros.21373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.True L, Coleman I, Hawley S, Huang CY, Gifford D, Coleman R, Beer TM, Gelmann E, Datta M, Mostaghel E, Knudsen B, Lange P, Vessella R, Lin D, Hood L, Nelson PS. A molecular correlate to the Gleason grading system for prostate adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(29):10991–10996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603678103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tomlins SA, Mehra R, Rhodes DR, Cao X, Wang L, Dhanasekaran SM, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Wei JT, Rubin MA, Pienta KJ, Shah RB, Chinnaiyan AM. Integrative molecular concept modeling of prostate cancer progression. Nat Genet. 2007;39(1):41–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rasul S, Balasubramanian R, Filipovic A, Slade MJ, Yague E, Coombes RC. Inhibition of gamma-secretase induces G2/M arrest and triggers apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(12):1879–1888. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Konishi J, Kawaguchi KS, Vo H, Haruki N, Gonzalez A, Carbone DP, Dang TP. Gamma-secretase inhibitor prevents Notch3 activation and reduces proliferation in human lung cancers. Cancer Res. 2007;67(17):8051–8057. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.van Es JH, van Gijn ME, Riccio O, van den Born M, Vooijs M, Begthel H, Cozijnsen M, Robine S, Winton DJ, Radtke F, Clevers H. Notch/gamma-secretase inhibition turns proliferative cells in intestinal crypts and adenomas into goblet cells. Nature. 2005;435(7044):959–963. doi: 10.1038/nature03659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wong GT, Manfra D, Poulet FM, Zhang Q, Josien H, Bara T, Engstrom L, Pinzon-Ortiz M, Fine JS, Lee HJ, Zhang L, Higgins GA, Parker EM. Chronic treatment with the gamma-secretase inhibitor LY-411,575 inhibits beta-amyloid peptide production and alters lymphopoiesis and intestinal cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(13):12876–12882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Real PJ, Tosello V, Palomero T, Castillo M, Hernando E, de Stanchina E, Sulis ML, Barnes K, Sawai C, Homminga I, Meijerink J, Aifantis I, Basso G, Cordon-Cardo C, Ai W, Ferrando A. Gamma-secretase inhibitors reverse glucocorticoid resistance in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Med. 2009;15(1):50–58. doi: 10.1038/nm.1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wei P, Walls M, Qiu M, Ding R, Denlinger RH, Wong A, Tsaparikos K, Jani JP, Hosea N, Sands M, Randolph S, Smeal T. Evaluation of selective gamma-secretase inhibitor PF-03084014 for its antitumor efficacy and gastrointestinal safety to guide optimal clinical trial design. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(6):1618–1628. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wu Y, Cain-Hom C, Choy L, Hagenbeek TJ, de Leon GP, Chen Y, Finkle D, Venook R, Wu X, Ridgway J, Schahin-Reed D, Dow GJ, Shelton A, Stawicki S, Watts RJ, Zhang J, Choy R, Howard P, Kadyk L, Yan M, Zha J, Callahan CA, Hymowitz SG, Siebel CW. Therapeutic antibody targeting of individual Notch receptors. Nature. 2010;464(7291):1052–1057. doi: 10.1038/nature08878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Noguera-Troise I, Daly C, Papadopoulos NJ, Coetzee S, Boland P, Gale NW, Lin HC, Yancopoulos GD, Thurston G. Blockade of Dll4 inhibits tumour growth by promoting non-productive angiogenesis. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1032–1037. doi: 10.1038/nature05355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ridgway J, Zhang G, Wu Y, Stawicki S, Liang WC, Chanthery Y, Kowalski J, Watts RJ, Callahan C, Kasman I, Singh M, Chien M, Tan C, Hongo JA, de Sauvage F, Plowman G, Yan M. Inhibition of Dll4 signalling inhibits tumour growth by deregulating angiogenesis. Nature. 2006;444(7122):1083–1087. doi: 10.1038/nature05313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moellering RE, Cornejo M, Davis TN, Del Bianco C, Aster JC, Blacklow SC, Kung AL, Gilliland DG, Verdine GL, Bradner JE. Direct inhibition of the NOTCH transcription factor complex. Nature. 2009;462(7270):182–188. doi: 10.1038/nature08543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tolcher AW, Messersmith WA, Mikulski SM, Papadopoulos KP, Kwak EL, Gibbon DG, Patnaik A, Falchook GS, Dasari A, Shapiro GI, Boylan JF, Xu ZX, Wang K, Koehler A, Song J, Middleton SA, Deutsch J, Demario M, Kurzrock R, Wheler JJ. Phase I study of RO4929097, a gamma secretase inhibitor of Notch signaling, in patients with refractory metastatic or locally advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(19):2348–2353. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Krop I, Demuth T, Guthrie T, Wen PY, Mason WP, Chinnaiyan P, Butowski N, Groves MD, Kesari S, Freedman SJ, Blackman S, Watters J, Loboda A, Podtelezhnikov A, Lunceford J, Chen C, Giannotti M, Hing J, Beckman R, Lorusso P. Phase I pharmacologic and pharmacodynamic study of the gamma secretase (Notch) inhibitor MK-0752 in adult patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(19):2307–2313. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hartmann D, de Strooper B, Serneels L, Craessaerts K, Herreman A, Annaert W, Umans L, Lubke T, Lena Illert A, von Figura K, Saftig P. The disintegrin/metalloprotease ADAM 10 is essential for Notch signalling but not for alpha-secretase activity in fibroblasts. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(21):2615–2624. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.21.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.De Strooper B, Annaert W, Cupers P, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Mumm JS, Schroeter EH, Schrijvers V, Wolfe MS, Ray WJ, Goate A, Kopan R. A presenilin-1-dependent gamma-secretase-like protease mediates release of Notch intracellular domain. Nature. 1999;398(6727):518–522. doi: 10.1038/19083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fryer CJ, White JB, Jones KA. Mastermind recruits CycC:CDK8 to phosphorylate the Notch ICD and coordinate activation with turnover. Mol Cell. 2004;16(4):509–520. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sethi N, Dai X, Winter CG, Kang Y. Tumor-derived JAGGED1 promotes osteolytic bone metastasis of breast cancer by engaging notch signaling in bone cells. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(2):192–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xing F, Okuda H, Watabe M, Kobayashi A, Pai SK, Liu W, Pandey PR, Fukuda K, Hirota S, Sugai T, Wakabayshi G, Koeda K, Kashiwaba M, Suzuki K, Chiba T, Endo M, Mo YY, Watabe K. Hypoxia-induced Jagged2 promotes breast cancer metastasis and self-renewal of cancer stem-like cells. Oncogene. 2011;30(39):4075–4086. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gallahan D, Callahan R. Mammary tumorigenesis in feral mice: Identification of a new int locus in mouse mammary tumor virus (Czech II)-induced mammary tumors. J Virol. 1987;61(1):66–74. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.1.66-74.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jhappan C, Stahle C, Wolff M, Merlino G, Pastan I. An epidermal growth factor receptor promoter construct selectively expresses in the thymus and spleen of transgenic mice. Cell Immunol. 1993;149(1):99–106. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1993.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Raafat A, Bargo S, Anver MR, Callahan R. Mammary development and tumorigenesis in mice expressing a truncated human Notch4/Int3 intracellular domain (h-Int3sh) Oncogene. 2004;23(58):9401–9407. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dang TP, Gazdar AF, Virmani AK, Sepetavec T, Hande KR, Minna JD, Roberts JR, Carbone DP. Chromosome 19 translocation, overexpression of Notch3, and human lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(16):1355–1357. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.16.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Eliasz S, Liang S, Chen Y, De Marco MA, Machek O, Skucha S, Miele L, Bocchetta M. Notch-1 stimulates survival of lung adenocarcinoma cells during hypoxia by activating the IGF-1R pathway. Oncogene. 2010;29(17):2488–2498. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sjolund J, Johansson M, Manna S, Norin C, Pietras A, Beckman S, Nilsson E, Ljungberg B, Axelson H. Suppression of renal cell carcinoma growth by inhibition of Notch signaling in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(1):217–228. doi: 10.1172/JCI32086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Agrawal N, Frederick MJ, Pickering CR, Bettegowda C, Chang K, Li RJ, Fakhry C, Xie TX, Zhang J, Wang J, Zhang N, El-Naggar AK, Jasser SA, Weinstein JN, Trevino L, Drummond JA, Muzny DM, Wu Y, Wood LD, Hruban RH, Westra WH, Koch WM, Califano JA, Gibbs RA, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE, Papadopoulos N, Wheeler DA, Kinzler KW, Myers JN. Exome sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma reveals inactivating mutations in NOTCH1. Science. 2011;333(6046):1154–1157. doi: 10.1126/science.1206923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Demehri S, Turkoz A, Kopan R. Epidermal Notch1 loss promotes skin tumorigenesis by impacting the stromal micro-environment. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(1):55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]