Abstract

Objective

The purpose of the study was to investigate the perceptions of administrators and clinicians regarding a public health facilitated collaborative supporting the translation into practice of the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) Adult Obesity Guideline.

Design and Sample

This qualitative study was conducted with ten healthcare organizations participating in a voluntary, interprofessional obesity management collaborative. A purposive sample of 39 participants included two to three clinicians and an administrator from each organization. Interview analysis focused on how the intervention affected participants and their practices.

Results

Four themes described participant experiences of obesity guideline translation: 1) a shift from powerlessness to positive motivation, 2) heightened awareness coupled with improved capacity to respond, 3) personal ownership and use of creativity, and 4) a sense of the importance of increased interprofessional collaboration.

Conclusions

The investigation of interprofessional perspectives illuminates the feelings and perceptions of clinician and administrator participants regarding obesity practice guideline translation. These themes suggest that positive motivation, improved capacity, personal creative ownership, and interprofessional collaboration may be conducive to successful evidence-based obesity guideline implementation. Further research is needed to evaluate these findings relative to translating the ICSI obesity guideline and other guidelines into practice in diverse clinical settings.

Keywords: Primary care, Obesity, Underserved populations, Rural health, Health care delivery, Collaboration, Public health nursing practice

Background

Obesity is a public health issue of epidemic proportions with costly health and social consequences (Finkelstein, Trogdon, Cohen, & Dietz, 2009; Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012; United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013a). Worldwide the prevalence of obesity has nearly doubled since 1980 (World Health Organization, 2013). Related health disparities are well documented: minority and socially disadvantaged populations suffer disproportionately from obesity (Lee, Harris, & Lee, 2013; United States Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health, 2014).

Global health leadership organizations have responded by recommending a multifaceted approach to decrease obesity using a public health approach. The World Health Organization (WHO) calls all stakeholders to take action at global, regional and local levels to improve diet and physical activity patterns of populations and community at the system level (Flodgren, Deane, Dickinson, et al., 2010; World Health Organization, 2014). In the United States, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) designated obesity as a public health priority with large-scale impact on health and urges the adoption of known, effective strategies to address the underlying causes of obesity in childcare, schools, hospitals, and workplaces (United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). Collaboration of multiple sectors is needed to address the obesity issue. The Institute of Medicine, Affordable Care Act, and National Public Health Performance Standards advocate for cooperation between public health and clinical partners to promote population health (Institute of Medicine, 2012; Affordable Care Act, 2012; National Public Health Performance Standards, 2013). Clinician practice is central to the obesity management effort, given that clinicians impact obesity-related health behaviors through clinical obesity management and prevention interventions (Farran, Ellis, Lee Barron, 2013; Fitch, Everling, Fox, et al., 2013).

Obesity stigma contributes to health disparities and poor health outcomes (Puhl & Heuer, 2010). The stigma and blame associated with being obese is a serious ethical and emotional issue for clinicians as well as patients. The global call to address obesity as a public health threat may thus marginalize individuals and bias practice within healthcare settings (Warin & Gunson, 2013). For example, diet, exercise, and weight-related counseling declined between 1995 and 2008, especially among patients with obesity and related comorbidities (Kraschnewski, Sciamanna, & Stuckey et al., 2013). Non-overweight physicians and nurses are more likely to engage in obesity management and prevention than overweight physicians and nurses (Bleich, Bennett, Gudzune, & Cooper, 2012; Zhu, Norman, & While, 2011). Furthermore, numerous evidence-based clinical obesity guidelines have been developed but not consistently translated into practice (Fitch, Everling, Fox, et al., 2013; Strategies to Overcome and Prevent Obesity Alliance, 2010).

In the Midwest United States, a voluntary, interprofessional partnership formed as a community response to these urgent obesity-related social and health issues. This partnership developed between local public health departments and clinical healthcare organizations in a four-county region with racially diverse populations characterized by a high prevalence of poverty and obesity. Their collaborative project addressed clinical practice deficiencies among healthcare systems, particularly those serving disadvantaged populations, by translating the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) Prevention and Management of Adult Obesity Guideline into clinical practice. The ICSI Guideline promotes routine assessment of Body Mass Index (BMI); comprehensive assessment of co-morbid conditions; and use of motivational interviewing techniques to assess readiness for change to assist in finding reasons for change, and build confidence in the ability to change (Fitch, Everling, Fox, et al., 2013). An evaluation of project outcomes was completed after 3 years of intervention, and findings are detailed in a separate publication (Erickson, Attleson, Monsen, et al., in review).

Research Purpose

Despite the pivotal role of clinicians in addressing obesity, clinician perspectives regarding translation of obesity guidelines have not been examined (Flodgren et al. 2010; Kraschnewski et al., 2013). The purpose of this study was to investigate the experience of obesity practice guideline translation of administrators and clinicians from diverse healthcare professions and settings.

Methods

Design and Sample

This qualitative research was conducted through a university-community partnership. The research was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Minnesota and and the Minnesota Department of Health. Informed written and verbal consent was obtained from all participants by the research assistant prior to the interview using institutional review board-approved consent process. All aspects of the study were described to the participants, and specific details were provided about the use of interview data to illuminate participant perspectives on guideline translation.

Administrators and clinicians (N=39) were recruited from the ten healthcare organizations by the public health nurse facilitating the government-funded interprofessional collaborative project. The healthcare organizations consisted of five primary care organizations, four local public health departments, and one independently owned physical and occupational therapy clinic. Of the primary care organizations, three were privately funded, one was a federally qualified health center (FQHC), and one was a migrant health service. The total unduplicated number of patients served was 70,138 (range 75 – 24,320). The average percentage of patients on Medicare, Medicaid and self-pay was 53.9% (range 12.3% – 99.48%). Demographic characteristics of the patients, counties, region, and United States are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Participating Organizations, Counties, Region, and Country.

Administrators and clinicians (N=39) were recruited from the ten healthcare organizations by the public health nurse facilitating the government-funded interprofessional collaborative project. The healthcare organizations consisted of five primary care organizations, four local public health departments, and one independently owned physical and occupational therapy clinic. Of the primary care organizations, three were privately funded, one was a federally qualified health center (FQHC), and one was a migrant health service. The total unduplicated number of patients served was 70,138 (range 75 – 24,320). The average percentage of patients on Medicare, Medicaid and self-pay was 53.9% (range 12.3% – 99.48%).

| Demographic Characteristics | Participating Organizations | Study Counties | Study Region | Study Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population, 2012 estimate | 70,138a | 157,028b | 5,379,646b | 313,873,685b |

| Persons self-identified as female, 2012 estimate | Not available | 49.9% b | 50.3% b | 50.8% b |

| Persons under 18 years, 2012 estimate | Not available | 23.2% b | 23.7% b | 23.5% b |

| Persons over 65 years, 2012 estimate | Not available | 17.6%b | 13.6% b | 13.7% b |

| Persons self-identified as Caucasian, 2012 estimate | 69.2% a | 93.9% b | 86.5% b | 77.9% b |

| Median household income, 2008–2012 estimate | Not available | $50,461b | $59,126 b | $53,046 b |

| Persons below poverty level, 2008–2012 | Not available | 12.0%c | 11.2% b | 14.9% b |

| Persons on Medicare, Medicaid, self-pay and/or uninsured | 53.9% a | 45.2%d | 36.8%e | 46.1%e |

| Persons with obesity (BMI > 30) | Not available | 29.4%f | 24.8%g | 35.7%h |

United States Census Bureau. (2014). State & county quickfacts. 2012 estimate. Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/27000.html

United States Census Bureau. (2013a). 2006–2010 American community survey 5-year estimates. Table S1701. Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk

United States Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.) Community health status indicators 2009. Community health status indicators report. Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://wwwn.cdc.gov/CommunityHealth/homepage.aspx?j=1

United States Census Bureau. (2013b). Health insurance historical tables. Health insurance coverage status and type of coverage by state – all persons: 1999 to 2012. 2009 data. Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/hlthins/data/historical/HIB_tables.html

United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013c). Obesity prevalence. Minnesota. 2010 county obesity prevalence. Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/atlas/countydata/County_EXCELstatelistOBESITY.html

United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013b). Adult obesity facts. 2010 state obesity rates. Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html

Ogden, C., Carroll, M., Kit, B., & Flegal, K. (2012). Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS data brief, no 82. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Participants interviewed included licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, public health nurses, nurse practitioners, physicians, physician assistants, registered dieticians, and physical/occupational therapists and assistants. All participants were recruited because of their organization’s participation in the project. Arrangements were made with the organizations to conduct interviews during the participants’ work day to ensure that no loss of wages or benefits resulted from participation.

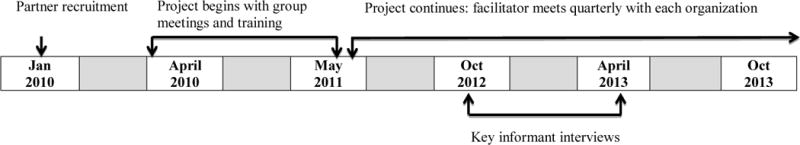

The research team consisted of five individuals: a university researcher, a graduate student research assistant, a public health director and a public health nurse from the project, and a trained research assistant who was a public health professional from the community. The research assistant conducted semi-structured interviews at the convenience of the participants over a six month period, beginning at the time point of two years into participation in the project (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(Thorson, D.R., Erickson, K.J., Attleson, I.S., Monsen, K.A., 2014)

This figure captures both the project intervention and the study timeline. In January of 2010, health care organizations, also known as project partners, were recruited to participate in a collaborative effort to implement evidence-based clinical obesity guidelines into practice. Group meeting and training opportunities were held over a 12 month period, followed by on-site quarterly meetings with the public health nurse project facilitator. The key informant interviews began about 18 months into the intervention and were completed approximately 6 months later.

Measures and Analytic Strategy

Content analysis of interview transcripts was completed by the members of the research team with content expertise (KE & DT), training in qualitative research methods (KM), and public health systems improvement (DT & IA). Rigor was assured through triangulation, inter-rater reliability, member checking, and reflexivity. Possible bias of the team members involved in the project was addressed through the assignment of interview role to the research assistant; and primary analysis roles to the university researcher and research assistant. The university research assistant completed the initial coding and analysis using Dedoose software (Dedoose, 2014). Field notes were provided from the research assistant interviewer regarding observations made throughout the interview process. The entire research team reviewed initial coding individually and then resolved differences through discussion. This process was repeated with an updated review of the initial themes, the raw data, and the field notes. The final themes were approved by all team members. Triangulation was possible through evidence of changes in clinician knowledge, behavior, and status measured using the Omaha System Problem Rating Scale for Outcomes (Martin, 2005; reported separately in Erickson, et al. in review).

Results

Four primary themes emerged from the interview data related to the participant perceptions of their experiences with obesity practice guideline translation: 1) a shift from powerlessness to positive motivation, 2) heightened awareness coupled with improved capacity to respond, 3) personal ownership and use of creativity, and 4) a sense of the importance of increased interprofessional collaboration. Concepts embedded across themes were personal self-respect and self-efficacy.

A Shift from Powerlessness to Positive Motivation

Initially, the participants expressed feeling powerless against the enormity of the problem. Some of these challenges were due to the difficult circumstances and comorbidities of the clients with obesity:

If a client is homeless, they don’t care what their BMI is. Basic needs get in the way. If they’re about to be evicted, they don’t care about what their BMI is. There are certain things that, unfortunately, take precedence for them. Or if they are so depressed that they’re not moving, that they’re hardly getting out of bed that makes it difficult to move forward. So it’s not so much that we don’t bring it up, it’s just that we feel that we’re not able to move it forward.

Some participants expressed personal barriers due to their own obesity:

So I found it hard, I found it hard initially to talk to people about it when I was obese myself, so that was probably one of my biggest stumbling blocks.

When resources and assistance became available through the project, powerlessness transformed into a feeling of personal power that fueled motivation to address the problem.

and throughout this I’ve worked on myself, and I’ve been able to now implement better education with my patients because I have done some of my own weight reduction, so that’s kind of helped me to feel like I can talk to people.

Another clinician reported:

Probably 2 or 3 years ago, I wasn’t real comfortable addressing it. And part of it was because I have weight to lose, and I know what a sensitive subject it is.

Participants noted newfound motivation because of the project:

We didn’t supersize overnight, and McDonald’s didn’t get rich overnight, but by golly, we really need to do something, so we can start a trend here. And I think that’s kind of where we’re at, and I think that [the project] has started some great momentum here.

Momentum built as the project progressed. Addressing obesity with clients became easier because of the tools and supports. There was less powerless blaming; instead there was a feeling of self-efficacy to change how things are done.

This is about the client, this isn’t about me as the nurse. I’m only a tool to help the client to get the resources to have better quality of life, I call it… because, let’s face it, if you’re a little bit healthier, you feel better, and if you feel better, you have a little bit better quality of life, right?

Less blaming and judgment was, in turn, noted by clients:

The feedback I’ve gotten from the clients is that they feel like they’re not being judged, and so then they feel more ready to make a change… when it’s coming from them… and not from an outside source that’s judging them.

Heightened Awareness Coupled with Improved Capacity to Respond

Participants perceived increased awareness of obesity: “I do see this as a problem throughout this region and the U.S., and I think it is going to be really good to start taking these small steps to fight against it” and “it’s something we can’t ignore anymore.”

Capacity to respond increased due to the project resources:

[The public health nurse project facilitator] has been very supportive – they’ve given us a lot of education, they’ve given us a lot of resources, just kind of organized that information for us, supported our staff, sharing best practices among other clinics with us, which we have found to be very valuable.

Participants from all organizations identified learning how to respond:

But I learned how to approach them, and make it a little bit lighter mood, and help them implement smaller changes, to get to the goal where they’re at. And I tried to change myself, saying “OK, look. I’ve been exercising this much. If I can do it, anyone can.” And I kind of partnered with them, rather than trying to tell them what to do. So we go through the options and I tell them why… or what it would do, and I show them stuff. And it’s just easier for me to talk to them now.

Incorporating charting prompts, reminders, and follow-up and referral information for each client within the health record based upon the guideline elements was supportive of guideline adherence. This including use of neutral standardized terms:

I also know that I like the fact that we approach this using the terminology of ‘nutrition’, and ‘physical activity’. We don’t talk about weight, and exercise…And when you stay away from those loaded words, it’s seems to be much more effective.

The cues or prompts most often mentioned were related to BMI screening “it’s your vital sign – you can’t miss it, you have to address it.”

The majority of participants described the importance and usefulness of the teaching materials and resources obtained from the project such as portion control plates and food models of portion sizes. Clinicians used these materials to facilitate weight management conversations with patients: “those kind of things really help our clients be able to visualize it, and it makes sense to them that way, rather than reading them a brochure.” Training in motivational interviewing was also key to practice transformation:

My practice has transformed itself with my learning and developing skill in using motivational interviewing with my visits. It has been the top tool in my toolbox with my patient work, and it has… utterly transformed my practice, and changed that dynamic with my work with patients.

They perceived increased feasibility and likelihood of having a clinician-client weight management conversation: “the more we talk about it, and the more we do this, the easier it is.”

However, limitations were mentioned in regard to capacity for obesity practice guideline adherence:

Really, it comes down to time. There are a lot of things that we can do that patients can say or do that they’ll remember, but when it comes to pure time involved, focusing on obesity, or health in general – physical health, dietary health – you know. Our Lifestyle Medicine people have much more time to focus on it, and give them more detailed information.

Participants also described additional capacity challenges that occurred when organizations experienced turnover in staff trained in implementing the guideline.

Personal Ownership and Use of Creativity

Participants described ownership and creativity relative to how guideline translation was designed and led within each organization.

I think I did mention, but I would say again, having that outside support… having someone… a nurse in another county, checking in with us, reminding… you know, coming and visiting us, and talking with us about our goal setting, and having met them, and “What kind of goal do you want to set next?“… it’s easy to think you’re going to do something, but then work happens, and you kind of forget this stuff, but then because we’ve had [the public health nurse project facilitator] coming, checking in with us, and reminding us of things, and reviewing previously set goals, and assisting us in setting future goals… it’s helped us stay on track, and it’s helped us continue to be mindful of the process. And it’s also been useful, too, to have other public health agencies in our region attempting to do the same kinds of things, because there’s a lot of support from that, a lot of sharing of ideas.

An administrator described the process in her organization: “There’s a real buy-in by the public health nurses. They are engaged, and they’re taking ownership, and they’re coming up with ideas, and thinking of things to do.” Ownership was intentional and collective:

We’re really trying to walk the talk, and we’re trying to be a clinical environment that promotes health and well-being for patients and staff.

Participants from primary care clinics described adapting guideline implementation to address issues with poverty, literacy, and access to care:

We happened to have a nutrition intern that comes in for 4–6 weeks, and they’re just preparing for their dietetics exam, so she developed a plate method brochure, that was really low literacy focused – colorful and easy to read. That was pretty well received by patients. So, that’s standard issue in English and Spanish at all of our sites.

A public health administrator described the thought process behind customizing strategies for the organization: “So, what we really looked at is ‘How can we incorporate even some of that terminology into our [services]?’”

A Sense of The Importance of Increased Interprofessional Collaboration

Participants from nine organizations mentioned the practical and inspirational effects of interprofessional collaboration on guideline adherence: it’s always better to feel like you’re part of a bigger group, trying to accomplish something.” A primary care provider described benefits of everyone involved in patient care prioritizing obesity prevention:

I think that the thing that has helped the most with that, is that the patients are identified when they come in – on certain visits – particularly physicals and follow-ups for chronic disease patients – and that the nurse has already identified that patient as falling into the obese category, and that information is identified as being… she’s already set out information for the patient, so I identify that, and so when it comes to the process end, they start it, and then I kind of go from there. So we work together as a team from the beginning of when they come in to when they get to the room. The diabetic educator does good, too, for the diabetic patients that are overweight – she can help me a lot with them. Otherwise, physical therapy has been helpful too. I’ve had a lot of patients that are overweight, but their ability to have certain activity and to exercise is limited due to knee pain or hip pain or things like that. Physical therapy has really gotten involved a lot and has helped work with patients doing exercises that they still can do, despite the hip pain, knee pain, whatever it may be. And that’s hard for me to teach, and physical therapy really does a good job helping me with that.

Referrals to professionals such as dieticians, registered nurse health coaches, and diabetic educators were also mentioned as helpful for guideline adherence: If they’re really ready to make a lot of changes, I send them to a dietician, and recommend them seeing an athletic trainer as well.” A nurse clinician noted: “We’ve added a lot more referrals to our dietician, and we just try and make it more of a priority to make a change.”

A dietician noted:

Then the next day we have a huddle. It’s myself, the provider, and the provider’s nurse. And we just go through all the patients that I have on my list, and we go through everything. We point out BMI when they’re above 25, and anything above 30, we point out at that point in time. So the provider’s already aware by the time the patient comes in. Unless they’ve had a significant weight decrease from their last visit, because this is from their previous visit… their most recent BMI. So, the provider and the nurse will see them, and then if the provider wants me to see them, then we will address it at my visit also.

The benefits of collaboration extend from the patient level to the population and system levels: “So we’ve been kind of working together, all of us that work with those specific populations, and try to tell each other, ‘Well, this works,’ or ‘This works.’

Participants also noted barriers to guideline adherence due to a lack of communication between professionals, related to either the absence of systemic information sharing or insufficient buy-in: “We try to link them up to some other sources for ongoing [care]… just because we’re not able to do that, the way that our visit structures is.” A lack of access to these interprofessional resources was described as a barrier to guideline adherence:

We also made sure that we refer to [Women, Infants, and Children] WIC, if they qualify for the WIC [program]… some of that takes care of the nutrition piece. But it’s kind of limited.

The interviewer field notes included the following summary statement. “All of the agency/organization’s administrators/supervisors that were interviewed supported the implementation of the evidence-based guidelines within their respective organization and were working with staff to incorporate these guidelines within their practice. For the most part, the agency/clinic staff interviewed appeared to be willing participants. The majority of those interviewed were very responsive and voiced that they were striving to implement the guidelines. Many of the clinicians stated that the Motivational Interviewing training that they attended was excellent and felt all direct staff should have it available to them. However, there were individuals who voiced that the obesity guidelines were nothing new. That addressing obesity issues is just a part of their clinical/medical process in which they have already received much training.”

Discussion

Participants from diverse healthcare organizations serving disadvantaged clients from areas with a high prevalence of obesity shared their experiences of translating obesity practice guidelines. Four themes emerged from the analysis: 1) a shift from powerlessness to positive motivation, 2) heightened awareness coupled with improved capacity to respond, 3) personal ownership and use of creativity, and 4) a sense of the importance of increased interprofessional collaboration. These themes describe the personal and collective emotional investment of participants as they changed health system practice related to this serious health problem and ethical issue over a three year period. Feelings of self-respect and self-efficacy were overarching concepts that were repeated across the themes, as participants described shifting from feeling powerless to having resources and skills to co-creating a new norm of evidence-based, interprofessional obesity management practice.

Participants had prior knowledge of global obesity trends; however, this knowledge was not sufficiently motivating to catalyze practice change. Instead, participants felt powerless, possibly related to the sensitive ethical and emotional concerns that relate to obesity. The project’s collaborative response to these issues overcame perceived barriers to addressing obesity with clients, and created shared motivation to improve obesity management. The project became the vehicle by which powerless was transformed to self-respect and self-efficacy. It brought the issue to the forefront, and provided tools, methods, and training. Participants responded positively to the project, feeling respected and feeling self-respect. This created a collective experience of pride, confidence, dignity, and honor vs. stigma, judgment, and blame.

Administrators and clinicians engaged in the creative design of guideline implementation within their organizations. Participant comments indicated a sense of ownership that developed from specifically tailoring the system’s support for the guideline and how it was incorporated within the system and workflow. This engagement in the change effort resulted in a feeling of self-efficacy, a belief in their ability to achieve guideline translation in their organizations.

The project fostered interprofessional collaboration and connections around the goal of guideline translation. Participant comments demonstrated that the project transcended silos in practice within and among organizations through collective effort and increased interprofessional connection. This created a shift in responsibility from clinicians as sole actors to the coordinated professional response of the organization. Clinicians were energized and expressed a desire for even more interdisciplinary interaction and communication beyond the project. The project also fostered a wider awareness of community resources to address obesity, and of personal experiences and goals for healthy weight, nutrition, and physical activity. These findings suggest that the PHN facilitator role may be key to supporting the implementation of obesity guidelines in clinical settings as well as within their own public health agencies.

Blame and stigma associated with obesity extended to healthcare clinicians as they described a sense of helplessness in managing population obesity. In the special case of clinician participants with obesity, the clinicians adapted and used the non-judgmental approaches that they were learning to use with clients in their own lives. Personal health changes such as weight reduction and increased physical activity were key to their feeling of success in counseling others. Further research is needed to understand the perspectives of obese clinicians regarding relationships between blame, stigma, and powerlessness and the transformation to self-efficacy and self-respect.

The collaborative guideline translation project and the ten participating organizations created a novel and diverse context for this qualitative research. The findings suggest that there may be generalizable concepts that should be further explored in other health systems to promote the ideals of interprofessional collaboration and to support clinicians charged with improving obesity management and population health. This transformation may be needed within an organization to support the same transformation in individual clinicians so they in turn can support the same transformation in their obese patients.

In order to successfully address the obesity epidemic and improve population health, public health agencies must be seen as a valued resource and respected partner in the community. Local public health agencies should create and nurture interprofessional collaboratives for the mutual benefit of all partners and their patients. Further research is needed to develop methods for linking system-level PHN interventions to population health outcomes.

Conclusion

An investigation of interprofessional perspectives regarding obesity practice guideline translation described four themes that illuminate the feelings and perceptions of clinicians and administrators involved in a project translating obesity guidelines in clinical practice. The themes suggested a transformation from powerlessness to having resources and skills to co-creating a new norm of evidence-based, interprofessional obesity management practice. Further research is needed to evaluate these findings relative to translating the ICSI obesity guideline and other guidelines in diverse clinical settings.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Support from Grant Number 1UL1RR033183-01 (National Center for Research Resources (NCRR)) and Grant Number 8UL1TR000114-02 (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS)) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to the University of Minnesota Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI); and Minnesota Department of Health Statewide Health Improvement Program (SHIP).

Contributor Information

Karen A. Monsen, University of Minnesota.

Ingrid S. Attleson, University of Minnesota, School of Public Health.

Kristin J. Erickson, Otter Tail County Department of Public Health, Fergus Falls, Minnesota.

Claire Neely, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, Bloomington, Minnesota.

Gary Oftedahl, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, Bloomington, Minnesota.

Diane R. Thorson, Otter Tail County Department of Public Health, Fergus Falls, Minnesota.

References

- Dedoose Software. Dedoose: Great research made easy. 2014 Retrieved June 15 2014 from http://dedoose.com.

- Erickson K, Attleson I, Monsen KA, Radosevich DM, Neely C, Oftedahl G, Thorson D. Translating evidence-based obesity guidelines into interdisciplinary practice: Measurement and evaluation, Midwestern United States, 2010–2013 (in review) [Google Scholar]

- Farran N, Ellis P, Lee Barron M. Assessment of provider adherence to obesity treatment guidelines. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 25. 2013;3:147–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2012.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual Medical Spending Attributable To Obesity: Payer-And Service-Specific Estimates. Health Affairs. 2009;28(5):w822–w831. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch A, Everling L, Fox C, Goldberg J, Heim C, Johnson K, Kaufman T, Kennedy E, Kestenbaun C, Lano M, Leslie D, Newell T, O’Connor P, Slusarek B, Spaniol A, Stovitz S, Webb B. Prevention and management of obesity for adults. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; 2013. Updated May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Flodgren G, Deane K, Dickinson HO, et al. Interventions to change the behaviour of health professionals and the organisation of care to promote weight reduction in overweight and obese people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000984.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) Primary care and public health: Exploring integration to improve population health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraschnewski JL, Sciamanna CN, Stuckey HL, Chuang CH, Lehman EB, Hwang KO, Sherwood LL, Nembhard HB. A silent response to the obesity epidemic: decline in US physician weight counseling. Medical Care. 2013;51:186–92. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182726c33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Harris KM, Lee J. Multiple levels of social disadvantage and links to obesity in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of School Health. 2013;83:139–149. doi: 10.1111/josh.12009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin KS. The Omaha System: A key to practice, documentation, and information management. Omaha, NE: Health Connections Press; 2005. Reprinted 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- National Public Health Performance Standards Program. Local public health system performance assessment version 2.0. Model Standards. 2008–2013 Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://www.cdc.gov/nphpsp/documents/final-local-ms.pdf.

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. p. 11. (NCHS data brief, no 82). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity stigma: Important considerations for public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1019–1028. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strategies to Overcome and Prevent Obesity (STOP) Alliance. Research and Policy, Research Center, Survey Results. Provider/patient survey on obesity in primary care setting. 2010 Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://www.stopobesityalliance.org/research-and-policy/research-center/survey-results.

- Thorson DR, Erickson KJ, Attleson IS, Monsen KA. Transforming an evidenced-based adult obesity guideline into clinical practice. Otter Tail County Public Health (MN) 2014 https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/16553143/m/PS4H.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2014.

- United States Census Bureau. 2006–2010 American community survey 5-year estimates. Table S1701. 2013a Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk.

- United States Census Bureau. Health insurance historical tables. Health insurance coverage status and type of coverage by state – all persons: 1999 to 2012. 2009 data. 2013b Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/hlthins/data/historical/HIB_tables.html.

- United States Census Bureau. State & county quickfacts. 2012 estimate. 2014 Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/27000.html.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity — United States, 1999–2010. MMWR 2013. 2013a;62(Suppl 3):120–128. [Google Scholar]

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult obesity facts. 2010 state obesity rates. 2013b Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity prevalence. Minnesota. 2010 county obesity prevalence. 2013c Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/atlas/countydata/County_EXCELstatelistOBESITY.html.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Winnable battles: Nutrition, physical activity, and obesity. 2014 Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://www.cdc.gov/winnablebattles/obesity/index.html.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Affordable Care Act and Reconciliation Act. Title IX: Revenue provisions. 2010 Section 9007. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Community health status indicators 2009. Community health status indicators report. 2009 Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://wwwn.cdc.gov/CommunityHealth/homepage.aspx?j=1.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Minority Health. Obesity Data/Statistics. 2014 Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=550.

- Warin MJ, Gunson JS. The weight of the word: Knowing silences in obesity research. Qualitative Health Research. 2013;23:1686–1696. doi: 10.1177/1049732313509894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. 2013 Retrieved June 15, 2014 from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/