Abstract

We reported previously on a vaccine approach that conferred apparent sterilizing immunity to SIVsmE660. The vaccine regimen employed a prime-boost using vectors based on recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) and an alphavirus replicon expressing either SIV Gag or SIV Env. In the current study, we tested the ability of vectors expressing only the SIVsmE660 Env protein to protect macaques against the same high-dose mucosal challenge. Animals developed neutralizing antibody levels comparable to or greater than seen in the previous vaccine study. When the vaccinated animals were challenged with the same high-dose of SIVsmE660, all became infected. While average peak viral loads in animals were slightly lower than those of previous controls, the viral set points were not significantly different. These data indicate that Gag, or the combination of Gag and Env are required for the generation of apparent sterilizing immunity to the SIVsmE660 challenge.

Keywords: SIVsmE660, vesicular stomatitis virus, virus-like vesicles, rhesus macaque, neutralizing antibody

Introduction

Recent reports have demonstrated that “functional” cures for HIV infection might sometimes be possible [1, 2]. Cessation of antiretroviral therapy, with or without allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, however, often leads only to a delay in the rebound of viral loads [3, 4]. Even if some individuals can maintain control of their viral loads throughout their lifetime, the limitations of using these strategies globally are apparent. Development of a prophylactic vaccine is still an essential component of any strategy to eradicate HIV infection worldwide.

Recombinant rhesus cytomegalovirus (RhCMV) vaccine vectors expressing Gag, Pol, Env, and a Rev-Tat-Nef fusion protein have been shown to induce immunity that can control and eventually clear a pathogenic SIVmac239 challenge virus in roughly half of the vaccinated rhesus macaques [5, 6]. A variety of other vaccine vectors have also achieved varying levels of apparent sterilizing protection in multiple low dose challenges [7–10]. Multiple low-dose challenge models closely mimic a heterosexual exposure to HIV because of the transmission of a small number of founder viruses from the challenge stock [11, 12]. In men who have sex with men (MSM), however, multiple founder viruses are often transmitted during the time of initial exposure [12, 13]. Since a greater number of founder viruses are transmitted during a high-dose challenge, this model may more accurately predict the efficacy of vaccines to prevent the transmission of HIV in MSM.

We previously described a vaccine regimen that resulted in apparent sterilizing immunity to a high-dose mucosal challenge with the pathogenic SIVsmE660 quasispecies. This vaccine used a heterologous prime-boost vaccine strategy with vectors based on recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) and virus-like vesicles (VLVs) derived from a Semliki Forest Virus (SFV) replicon packaged with VSV G (SFV-G). These vectors encoded Gag and Env proteins derived from the SIVsmE660 viral swarm [14]. Four out of six animals challenged never showed detectable viral loads, and the two that were infected rapidly controlled their viral loads to below the limit of detection. Control of viral loads in the infected animals was mediated by CD8+ T cells, as evidenced by the rebound in viral loads when CD8+ T cells were depleted from these animals [14]. The 4 protected animals showed no rebound in viral loads upon CD8+ T cell depletion implying that the vaccine generated sterilizing immunity. These animals had high neutralizing antibody (nAb) to E660 Envs prior to challenge, but only marginal or undetectable CD8+ T-cell responses to Env and Gag. These results suggested that antibody to Env might be sufficient for protection. Therefore, in the current study, we asked if the same vaccine regimen expressing Env alone would generate similar sterilizing immunity.

Materials and Methods

Animals, vaccination dosage, and sample preparation

In the current study, five previously protected and eight naïve Indian-origin rhesus macaques were enrolled. Of the protected animals, animal EF30 received a VSV vector expressing granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor at the time of prime [15], and the other four, CJ98, CM17, DT03, and FP72 [14] did not. The eight naïve macaques were selected based on their lack of restrictive Trim 5α and MHC class I genotypes (Table 1). All animals were negative for serum antibodies to herpes B virus, SRV, and simian T-lymphotropic virus. The naïve animals were negative for serum antibodies to simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV). The animals were fed and housed according to regulations set forth by the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [3] and the Animal Welfare Act at the Tulane National Primate Research Center (TNPRC). All animals were born and raised at the TNPRC. Every procedure was approved by the TNPRC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and was in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Animal Welfare Act. The TNPRC maintains an AAALAC-I accredited animal care and use program. The animals are maintained on a 12 hour light/dark cycle and fed a commercially available nonhuman primate chow twice daily and water is available ad libitum. Nonhuman primate animal rooms are maintained at a temperature of 64–84°F with a humidity range of 30–70%. The rooms are provided 10–15 fresh air changes per hour. All animals receive enrichment as part of the TNPRC Policy on Environmental Enrichment. Enrichment includes durable and destructible objects in their cage, perches, various food supplements (fruit, vegetables, treats) foraging or task-oriented feeding methods fed a minimum of three times weekly, and human interaction with caretakers. Animals are observed twice daily by care staff and a veterinarian is notified if abnormalities are present. Procedures were conducted with the use of ketamine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg intramuscularly; Ketaset, Fort Dodge Laboratories). Animals are administered buprenorphine hydrochloride (0.03 mg/kg intramuscularly twice daily; Buprenex, Reckitt & Colman) for any procedures expected to induce pain or distress. Tissue and serum samples were shipped cryogenically frozen to Yale University and were stored in liquid nitrogen upon arrival.

Table 1.

Genotypes of animals in the Env-only study. The sex of each animal is denoted in parentheses.

| Animal ID | A01 | A02 | A08 | A11 | B01 | B03 | B04 | B08 | B17 | DRB* w201 | Trim 5α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BJ42 (M) | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | TFP/TFP |

| BV15 (M) | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | TFP/Q |

| CC61 (M) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | TFP/Q |

| CD71 (M) | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | TFP/Q |

| CK48 (F) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | TFP/Q |

| CR43 (F) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | TFP/Q |

| DR07 (F) | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | TFP/Q |

| EL27 (F) | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | TFP/Q |

Because vaccinees generally develop a strong neutralizing antibody against the VSV glycoprotein (G), our vaccine regimen employs glycoprotein exchange vectors [16]; the serotypes of which are indicated in parentheses at the time of prime and boosts in Figures 1A and 2A. For the re-challenge experiments, the animals were boosted with a Chandipura (Ch) glycoprotein exchange VSV vector expressing the E660 Env only, VSV(Ch)-EnvG [16]. Animals received a total of 1×108 VSV plaque forming units (PFU)—6×107 PFU intramuscularly (IM) and 4×107 intranasally (IN) per vaccination. The previously published vaccine schedule [14] was used for the naïve animals. As before, the SFV-G VLV boosting vectors were delivered IM at a concentration of 1×107 infectious units (IU) per animal. Animals were challenged intrarectally with the same stock of SIVsmE660 at a high titer (TCID50=4000). Quantitative PCR of plasma viral RNA was conducted by the University of Wisconsin core facility.

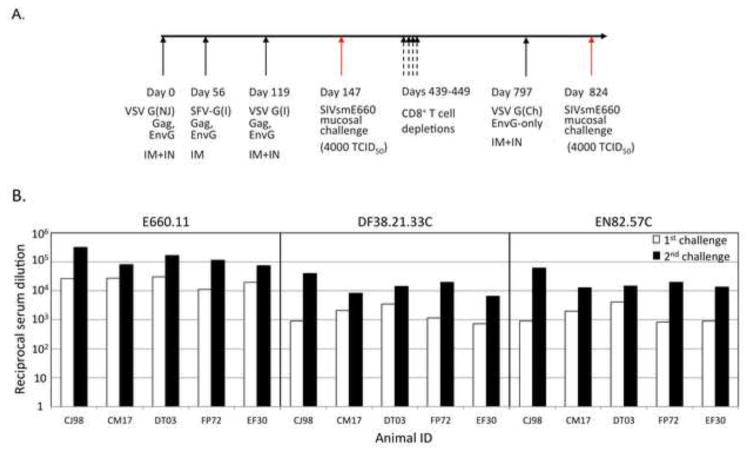

Figure 1. Re-challenge of protected animals.

(A) Complete vaccination and challenge history of the protected animals. The G serotype of the vector is indicated within parentheses: Indiana (I), New Jersey (NJ), or Chandipura (Ch). The route of immunization is also indicated: intramuscular (IM) or intranasal (IN). (B) Neutralizing antibody titer of SIVsmE660 envelopes on the day of first (white bars) and second (black bars) challenge. The three envelopes tested, E660.11 (left), DF38.21.33C (center), and EN82.57C (right) are indicated. IFN-γ by PBMCs is shown in response to the Env (C) and Gag (D) vaccine antigens. The days of boost and re-challenge are indicated by the black and red arrows, respectively. (D) Plasma viral RNA loads for the re-challenged animals. All animals remained protected against a second high dose challenge. Average control viral loads shown in orange for reference.

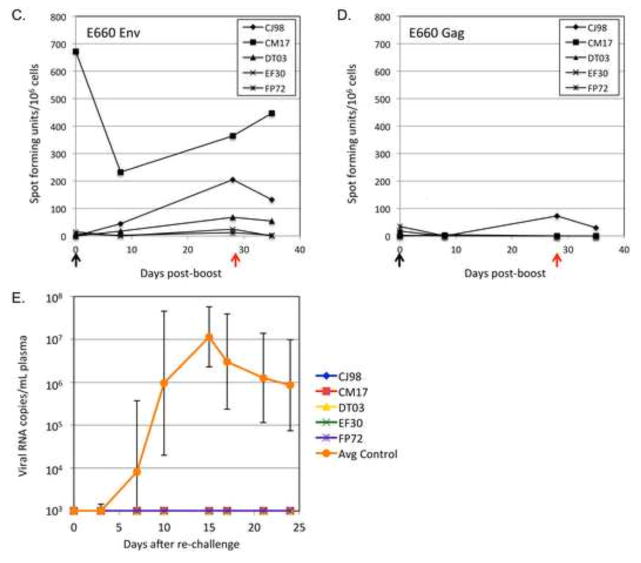

Figure 2. Vaccination schedule and plasma virus loads.

(A) Vaccination schedule with vectors expressing Env alone for the eight naïve macaques. The G serotype of the vector is indicated within parentheses. Animals were challenged rectally with a high dose (TCID50=4000) of the SIVsmE660 viral stock at day 147. (B) Plasma virus loads for individual animals in the current study. (C) Average plasma virus loads for Env-only vaccine group animals in the current study (green); the fully protected animals (orange) or infected animals (red) from the previous Gag+Env vaccine study [14] and unvaccinated control animals (blue).

Neutralization Assays, gp140 ELISAs, and ELISPOT assays

The methods used to measure serum antibody and cellular immunity have been reported previously [14]. For the neutralization assays, TZM-bl cells and plasmids for generating the HIV pseudoviruses were kindly provided by David Montefiori (Duke University, Durham, NC). The target vaccine SIVsmE660 gp140 antigen used for ELISAs was generated using a recombinant vaccinia virus (rVV) encoding the EnvG gene [17]. The rVVs expressing the full-length SIVsmE660 vaccine antigens used in the ELISPOT assays were also generated using this system. Plasmids and small plaque forming vaccinia virus (Rb12) used to generate rVVs were kindly provided by Bernard Moss. Codon-optimized genes encoding founder virus Envs EN82.57C and DF38.21.33C [14] were synthesized by Genscript (Piscataway, NJ) and have been deposited in GenBank (accession numbers KJ130318 and KJ130319, respectively).

Surface Plasmon Resonance

Binding studies were performed at 25°C, as described by others [18], using a Biacore T100 optical biosensor equipped with a CM5 research-grade sensor chip (GE Healthcare, Biacore). Neutravidin was amine-coupled to approximately 15,000 response units (RU) on the CM5 chip. A synthetic peptide of the V2 loop sequence present in the vaccine (CIKNNSCAGLEQEPMIGCKFNMTGLKRDKRIEYNETWYSRDLICEQSANESESKCY) was generated, biotinylated, and cyclized under thermodynamically controlled conditions by JPT peptides (Berlin, Germany). The peptide was captured to 1,000–3,000 RUs on cells 3 and 4 of the chip. Cell 2 was used as a Neutravidin-biotin negative control to assess the quality of referencing. Loosely associated peptides were removed from the chip by an injection of 10 mM HCl. Unbound biotin was saturated with amino-PEG-biotin (Pierce Biotechnology Inc.) and rinsed with 10 mM HCl. Sera diluted 50-fold in running buffer (25 mM Tris, 137 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.4) were injected for 240 seconds (s) at a flow rate of 30 μL/min. After 60s of dissociation time, anti-rhesus IgG or IgA secondary antibodies (20 μg/mL) were injected for 120s (10 μl/min). The chip was regenerated by subsequent injections of 50 mM HCl and EDTA, each for 30s at 30 μl/min, followed by an injection of running buffer for 60s at 30 μl/min. The level of serum anti-V2 antibody was estimated as the amplitude of the binding of anti-isotype antibody (anti-IgG or -IgA) captured during injection of the diluted macaque sera. The anti-serotype binding responses were double-referenced against nonspecific binding to neutravidin alone (cell 1) and responses generated by injections of buffer rather than diluted sera.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed by performing a two-tailed T test with the statistical analysis software Prism 6 (GraphPad).

Results

Rechallenge of protected animals

We decided to first test if the previously protected animals would maintain their sterilizing immunity against an additional high-dose mucosal challenge with SIVsmE660 [14, 15]. Because of the high titers of neutralizing antibodies, and relatively low levels of cell-mediated responses produced by these animals, we suspected that the sterilizing protection seen was antibody mediated. Therefore, prior to the re-challenge (650 days after the initial challenge), the protected animals received a boost with a recombinant VSV vector expressing an SIVsmE660 Env protein that has its cytoplasmic domain replaced with the cytoplasmic domain of VSV G (EnvG). A full historical timeline for these animals is shown in Figure 1A. The boost increased neutralizing antibody titers to the tier 1 Env, E660.11, as well as two transmitted founder virus Envs (DF38.21.33C and EN82.57C) in each animal to levels higher than those at the time of initial challenge (Fig. 1B). Only one animal, CM17 showed high levels of Env responsive PBMCs at the time of boost (Fig. 1C) as assayed by IFN-γ ELISPOT. After the boost, two animals, CJ98 and DT03, showed an increase in the numbers of circulating Env responsive PBMCs. Only one animal, CJ98, showed an appreciable level of Gag responsive circulating PBMCs at the time of re-challenge (Fig. 1D). The animals were re-challenged with the original stock of SIVsmE660 at a high dose (TCID50=4000) and all remained protected (Fig. 1E).

Vaccination schedule, SIVsmE660 challenge, and plasma viral loads of naïve animals

We next wanted to test the hypothesis that the sterilizing protection we previously demonstrated for a VSV/SFV-G heterologous prime boost vaccine regimen [14, 15] was provided by the high level of neutralizing antibodies to Env induced by the vaccine. Eight rhesus macaques that lacked SIVsmE660-restrictive Trim5α TFP/CypA [19] and MHC alleles were selected for the study. Their genotypes are shown in Table 1. The vaccination scheme was the same as in the previous study [14], except that we omitted vectors encoding Gag (Fig. 2A). Animals were primed (day 0) with a VSV vector expressing an SIVsmE660 Env protein that has its cytoplasmic domain replaced with the cytoplasmic domain of VSV G (EnvG). They were boosted with the SFV-G virus-like vesicle (VLV) vector encoding EnvG (day 56) and then given a second boost with a VSV vector encoding EnvG (day 119).

The animals were then challenged intrarectally at day 147 with the same high dose (TCID50=4000) of the SIVsmE660 quasispecies used above and in the previous study [14, 15]. As shown in Figure 2B, all eight animals became infected after the challenge. Average plasma viral loads for the previously published vaccine and control groups are compared in Figure 2C. The Env-only (Fig. 2C, green line) vaccine regimen tested here suppressed peak viral loads about 10-fold, but the peak loads were about 10-fold higher than the infected animals from the previous Gag+Env vaccine group (Fig. 2C, red line). None of the animals in the Env-only vaccine group controlled their infection, and their viral set points were even slightly higher than control animals (Fig. 2C, blue line).

ELISA titers of gp140 specific antibodies

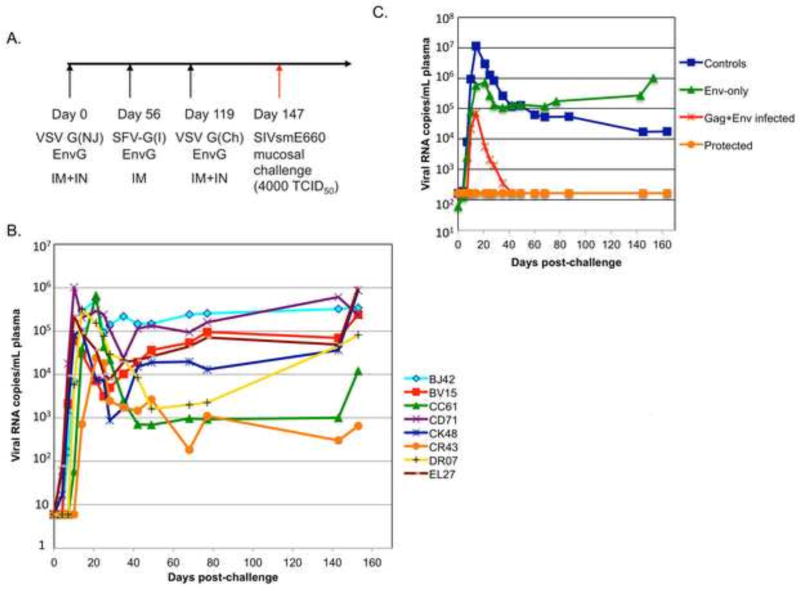

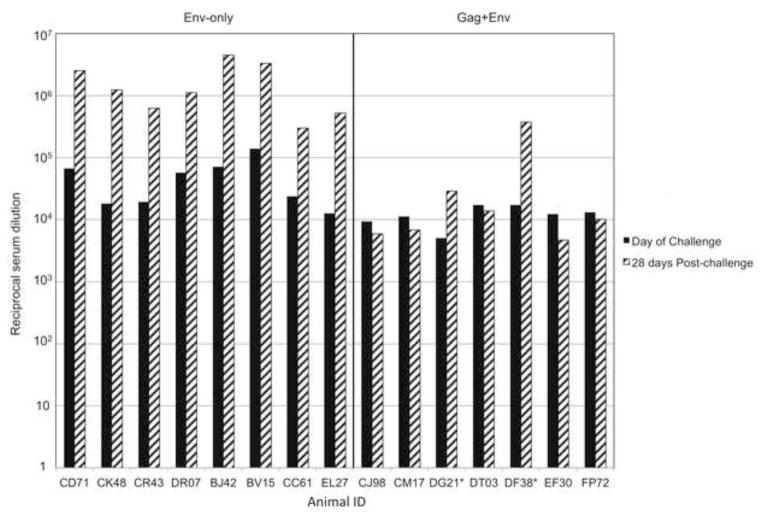

To determine if the animals receiving the Env-only vaccine generated levels of Env-specific antibodies comparable to animals from the previous study using Env and Gag antigens [14], we initially performed ELISA assays using sera collected at the day of challenge and 28 days post-challenge. At the time of challenge, the animals that received the Env-only vaccine (Fig. 3, left panel) generated comparable or higher titers of antibodies to gp140 to those that received the Gag+Env vaccine (Fig. 3, right panel). The average titers were significantly higher in the Env-only group (p<0.04). Consistent with the animals from the Env-only vaccine group becoming infected, all showed an anamnestic antibody response to gp140 28 days post-challenge. Only those animals that were not protected from infection in the previous Gag+Env vaccine study (DF38 and DG21, denoted by an asterisk in Fig. 3, right panel) showed an anamnestic antibody response.

Figure 3. Anti-gp140 serum antibody titers.

Serum antibody titers from the day of original challenge (black bars) and 28 days post-challenge (striped bars) are shown for each animal. Sera from animals that received the Env-only (left panel), and those that received the combination Gag+Env (right panel) were tested in parallel. Animals DF38 and DG21 were infected in the original study and are denoted by asterisks. The reciprocal serum dilution that gave a reading of O.D.=0.2 was used as the endpoint for defining the titer.

The Env-only vaccine generated high titers of neutralizing antibodies

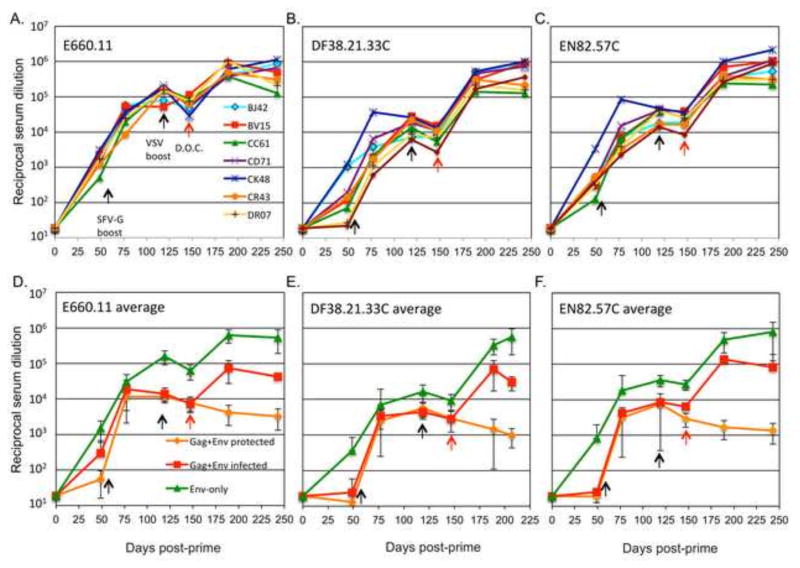

We next tested the ability of the sera from the Env-only vaccine animals to neutralize an SIV envelope from the viral swarm (E660.11), and transmitted/founder (T/F) envelopes isolated from infected animals from a previous study (EN82.57C and DF38.21.33C) [14]. As shown in Figure 4A, animals from the Env-only vaccine group had neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) against the tier 1 E660.11 envelope by the time of the first boost (day 56). Following the boost with the VLV-EnvG vector E660.11 at day 56, nAbs titers rose approximately 100-fold by day 119. The final VSV boost at day 119 did not increase the titers of nAb against E660.11.

Figure 4. Neutralization of SIVsmE660 envelopes.

Serum samples from animals that received the Env-only vaccine and serum samples from the Gag+Env vaccine study were tested for their ability to neutralize pseudovirions carrying different Env proteins derived from the viral swarm or founder viruses from infected animals [14]. Pre-and post-challenge serum nAb titers for individual animals in the Env-only vaccine group using Envs E660.11 (A), DF38.21.33C (B) and EN82.57C (C). For each Env tested, a comparison of the average neutralizing titers from the Env-only group in the present study (green), and the previous Gag+Env vaccine group (orange, protected animals; red, infected animals) are shown in panels D–F. Days of vaccine boosts (black arrows), and the day of challenge (red arrows) are indicated.

When the Env-only animals were compared to the previous Gag+Env animals, similar neutralization titers against E660.11 were seen over the vaccination course. In Figure 4D, the average neutralization of E660.11 envelope is shown for the Env-only (green line) and Gag+Env vaccinated animals. The Gag+Env group was divided into protected (orange line) and infected (red line) animals. By the time of the VSV boost (day 119), the Env-only animals had developed significantly higher titers of nAbs against E660.11 envelope than either the protected or infected animals of the Gag+Env group as determined by a two-tailed T test (p<0.0006, and p<0.02, respectively). This significant difference in nAb titers between the two groups was maintained through the day of challenge (day 147). Only those animals that were unprotected (green and red lines) showed an anamnestic nAb response after the challenge.

We also tested the ability of the sera from the Env-only animals to neutralize two T/F virus envelopes isolated from an infected control animal (EN82), and a Gag+Env vaccinated animal that became infected (DF38) [14]. The two T/F envelopes, DF38.21.33C and EN82.57C, are more difficult to neutralize than E660.11 (Fig 4 A–C). The serum nAb titers against both DF38.21.33C (Fig. 4B) and EN82.57C (Fig. 4C) averaged about 10-fold lower than those against E660.11 on the day of challenge. Consistent with the results from the E660.11 neutralization, the Env-only vaccine regimen elicited higher average levels of nAb against both the DF38.21.33C and EN82.57C envelopes, than did the Gag+Env vaccine regimen (Fig. 4 E and F).

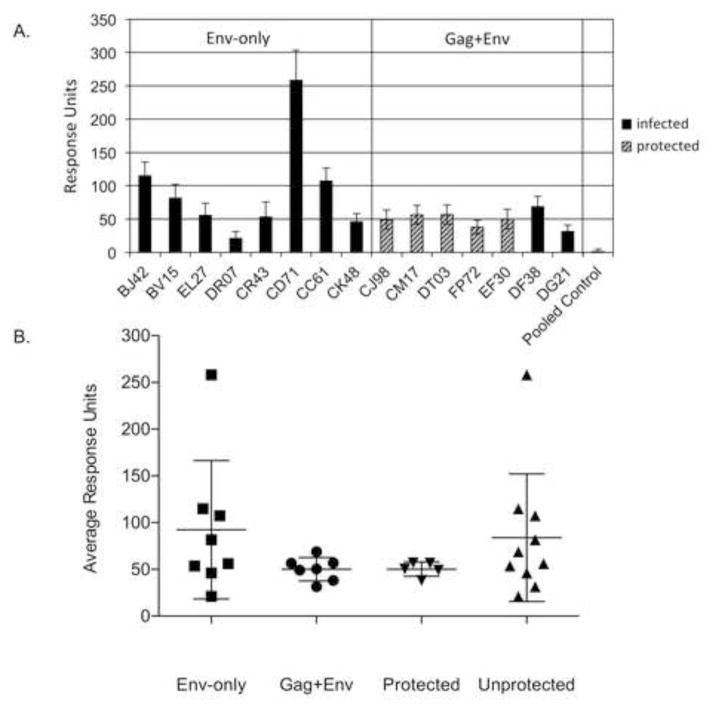

Antibody specific for the gp120 V2 loop does not correlate with protection

Previous SIV vaccine studies have shown a correlation between V2 loop-binding antibodies and vaccine protection [7, 20]. We therefore determined if either vaccine regimen, Gag+Env or Env-only, elicited V2-binding antibodies, and if they correlated with protection. Following the approach used by others [7], we used a synthetic, cyclized V2 loop corresponding to the amino acid sequence present in the vaccine envelope. Day of challenge antibody binding to this synthetic V2 loop was then measured by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) for each animal. Antibody binding to the cyclized V2 peptide, presented as response units in Figure 5A. (n=4), was higher in most animals that received the Env-only vaccine as compared to those that received the Gag+Env vaccine. The average response for each group is shown in Figure 5B. Although the Env-only group had higher average IgG binding to the peptide, this antibody did not confer protection from infection. The lack of correlation with protection is also clear when the mean V2 Ab binding of the five protected and ten unprotected animals from the Gag+Env and Env-only groups are compared (Fig. 5B). No animals from either group showed anti-V2 serum IgA binding.

Figure 5. Anti-V2 loop IgG antibodies.

(A) Sera from animals of the Env-only group, Gag+Env group, or pooled sera from unvaccinated animals were tested for their ability to bind a cyclized V2 peptide using surface plasmon resonance. Infected animals are represented by black bars. The animals protected in the previous Gag+Env study are represented by striped bars. The data shown are averaged binding response units collected for each serum sample on two cells of a CM5 chip containing the V2 peptide, during two separate experiments (n=4); error bars represent single standard deviations. (B) The average binding response for each vaccine group, and for protected or infected animals combined from both studies is represented.

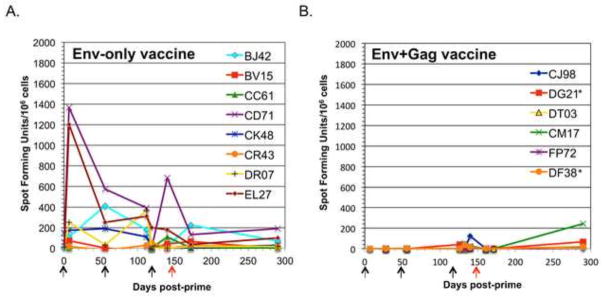

Cellular interferon gamma response to the Env vaccine antigen

To determine if the Env-only vaccine induced a cellular immune response to the SIV envelope, we used an ELISPOT assay to measure IFN-γ produced in response to the Env antigen. The responses of individual animals are shown in Figure 6A. Five out of eight of the animals generated significant cellular immune responses to the vaccine Env antigen. These responses were higher than we saw previously for the animals given the Gag+Env vaccine, shown in Figure 6B. and [14]. We also did not observe any correlation between the cellular immune response to Env and the viral loads. The Env-only animals did not show IFN-γ responses to the cloned E660 Gag antigen used in the previous studies (data not shown).

Figure 6. Cellular immune responses to Env.

IFN-γ ELISPOT assay of SIV Env specific responses for all animals in the Env-only (A) and Gag+Env (B) groups. Data are represented as spot forming cells (SFC) per 1×106 cells. Arrows represent times of priming and boosting vaccinations (black) and day of challenge (red). Asterisks denote the two animals in the Gag+Env group from the previous study that were infected.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that a heterologous prime-boost vaccine based on VSV and hybrid SFV-VSV (SFV-G) virus-like vesicle vectors could provide sterilizing immunity to a high-dose mucosal challenge with SIVsmE660 [14, 15]. The vectors encoded Gag and Env proteins derived from the SIVsmE660 viral swarm. We hypothesized, based on the immune responses detected, that the protection could be due to Env neutralizing antibodies preventing infection. Therefore, we boosted the previously protected animals from the prior study [14, 15] with a recombinant VSV vector expressing Env alone almost two years after the original challenge (Fig. 1A). By the day of re-challenge, the boost had increased neutralizing antibodies against the tier 1 Env, E660.11, as well as two T/F virus Envs from the original study to titers higher than that seen on the day of the first challenge (Fig. 1B). Only one animal, CM17, showed high numbers of PBMCs that produced IFN-γ to Env antigen at the time of boost. After the boost, two additional animals showed Env responsive PBMCs. The decrease in Env responsive PBMCs in animal CM17 most likely represented an efflux of these cells into the tissues and lymph nodes after the boost (Fig. 1C). Every animal remained completely protected against a second high dose mucosal challenge, TCID50=4000 (Fig. 1E).

To determine if the protection was due to immune responses to Env alone, we vaccinated eight rhesus macaques with the same VSV and SFV-G vectors encoding only the recombinant Env gene. We found that this “Env-only” vaccine did not provide protection because all animals became infected and had viral set-points comparable to previously infected animals that did not control their loads (Fig. 2) [14, 15].

The Env-only vaccine generated significantly higher levels of pre-challenge Env specific antibodies than the Gag+Env vaccine, as measured by ELISA (Fig. 3). The Env-only vaccine regimen also elicited higher levels of nAbs to the tier 1 E660.11 Env, and to two harder to neutralize T/F Envs (Fig. 4) isolated from infected animals in our previous study [14]. By the day of challenge (147 days post-prime), the Env-only vaccine recipients had significantly higher average serum nAb against E660.11, DF38.21.33C, and EN82.57C when compared to the serum from either the infected or protected animals from the Gag+Env study (Fig. 4 D–F). While we did see low levels of nAb against the more difficult to neutralize tier 2 Env CR54PK.2A5 in the sera of animals from the Env-only group, none neutralized to the 50 percent threshold [15] (data not shown). The higher antibody responses most likely resulted from employing the same total vector titers in prime and boosts, while eliminating the vectors expressing Gag. This eliminates competing response to Gag while doubling the Env vector dose. Both Gag and Env expressing vectors replicate to similar titers and expressed similar amounts of protein (data not shown).

Although V2-loop binding antibodies correlated with protection against a low-dose SIVmac251 heterologous challenge model for an adeno/poxvirus based vaccine [7], we did not see a correlation between the presence of V2-binding antibodies and protection in our high-dose challenge model employing a viral swarm. The Env-only vectors generated similar or higher levels of V2-binding antibodies in most animals than in those that received the Gag+Env vectors (Fig. 5). V2-binding antibodies might be important for protection in low-dose heterologous challenges [7], or during the course of some natural exposures [21, 22], but might not be effective during a high-dose challenge.

Roederer, et al. have recently reported a four amino acid signature within the C1 domain of SIVsmE660 Env that correlated with neutralization sensitivity (VTRN) or resistance (IAKN) of transmitted/founder (T/F) viruses [23]. In our previous Gag+Env vaccine study we saw transmission of only the sensitive VTRN signature in the single T/F virus Env sequences found in the only two infected animals, DG21 and DF38 (accession numbers KM496659-KM496961), in the vaccine group [14, 24]. We have not yet performed the single genome amplification and sequence analysis from the animals in this Env-only vaccine study to determine if there was any selection for neutralization resistant viruses. Both cloned founder virus Envs (EN82.57C and DF38.21.33C) used in this study have neutralization sensitive C1 amino acid signatures, VTRS and VTRN, respectively.

Even though the Env vectors generated high levels of nAb against tier 1 Envs, they did not elicit broadly nAbs against heterologous Envs (data not shown). Recent published studies have shown that the generation of broadly nAbs is slow to develop in infected patients because of the extent of hypermutation required to modify the germline sequence [23]. Broadly nAbs can act as a therapeutic in controlling an established infection in both humans and macaques [24, 25]. Enhancing the immunogenicity of Env [26, 27], or designing innovative strategies to produce and deliver broadly nAbs [25, 28–31] are alternative strategies for vaccination.

We also noted an increase in cellular immune responses to Env in this study compared the Env+Gag study (Fig. 6). This increase could again be due to the increased Env vector titer, but also to lack of competition from immunodominant Gag epitopes. It has been reported that CD8+ T cell responses to immuno-dominant SIV Gag epitopes are capable of suppressing responses to Env [32].

Our results indicate that vectors encoding Gag are a critical component of our vaccine that provides sterilizing protection against high dose mucosal challenge with SIVsmE660. It is certainly possible that undetected mucosal cellular immune responses to Gag rather than antibody to Env were important in the vaccine protection [33]. To determine if there is some synergy between Gag and Env immune responses in the protective vaccine, it will now be critical to determine if Gag alone can provide the same level of protection as Gag+Env. These experiments could be informative for design of future clinical trials of HIV vaccines.

A vaccine expressing Env and Gag proteins protects against SIV infection.

The same vaccine expressing Env alone does not.

Gag or the combination of Gag and Env are important for protection.

Vaccine protection did not correlate with Env antibodies.

Vaccine protection did not correlate with cellular responses to Env.

Acknowledgments

We thank Philip Johnson for supplying the SIVsmE660 challenge stock. This work was supported by NIH grants AI-45510, AI-40357, and F32 AI085767, the Tulane National Primate Research Center grant RR000164, and NIAID contract AI8534. The T100 Biacore instrumentation was supported by NIH Award S10RR026992-0110.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Saez-Cirion A, Bacchus C, Hocqueloux L, Avettand-Fenoel V, Girault I, Lecuroux C, et al. Post-treatment HIV-1 controllers with a long-term virological remission after the interruption of early initiated antiretroviral therapy ANRS VISCONTI Study. PLoS pathogens. 2013;9:e1003211. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutter G, Nowak D, Mossner M, Ganepola S, Mussig A, Allers K, et al. Long-term control of HIV by CCR5 Delta32/Delta32 stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:692–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henrich TJ, Hu Z, Li JZ, Sciaranghella G, Busch MP, Keating SM, et al. Long-term reduction in peripheral blood HIV type 1 reservoirs following reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2013;207:1694–702. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Persaud D, Gay H, Ziemniak C, Chen YH, Piatak M, Jr, Chun TW, et al. Absence of detectable HIV-1 viremia after treatment cessation in an infant. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1828–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansen SG, Ford JC, Lewis MS, Ventura AB, Hughes CM, Coyne-Johnson L, et al. Profound early control of highly pathogenic SIV by an effector memory T-cell vaccine. Nature. 2011;473:523–7. doi: 10.1038/nature10003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen SG, Piatak M, Jr, Ventura AB, Hughes CM, Gilbride RM, Ford JC, et al. Immune clearance of highly pathogenic SIV infection. Nature. 2013;502:100–4. doi: 10.1038/nature12519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barouch DH, Liu J, Li H, Maxfield LF, Abbink P, Lynch DM, et al. Vaccine protection against acquisition of neutralization-resistant SIV challenges in rhesus monkeys. Nature. 2012;482:89–93. doi: 10.1038/nature10766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel V, Jalah R, Kulkarni V, Valentin A, Rosati M, Alicea C, et al. DNA and virus particle vaccination protects against acquisition and confers control of viremia upon heterologous simian immunodeficiency virus challenge. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:2975–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215393110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flatz L, Cheng C, Wang L, Foulds KE, Ko SY, Kong WP, et al. Gene-based vaccination with a mismatched envelope protects against simian immunodeficiency virus infection in nonhuman primates. Journal of virology. 2012;86:7760–70. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00599-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Letvin NL, Rao SS, Montefiori DC, Seaman MS, Sun Y, Lim SY, et al. Immune and Genetic Correlates of Vaccine Protection Against Mucosal Infection by SIV in Monkeys. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:81ra36. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keele BF, Li H, Learn GH, Hraber P, Giorgi EE, Grayson T, et al. Low-dose rectal inoculation of rhesus macaques by SIVsmE660 or SIVmac251 recapitulates human mucosal infection by HIV-1. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2009;206:1117–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, Bar KJ, Wang S, Decker JM, Chen Y, Sun C, et al. High Multiplicity Infection by HIV-1 in Men Who Have Sex with Men. PLoS pathogens. 2010;6:e1000890. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tully D, Power K, Bedard H, Boutwell C, Charlebois P, Ryan E, et al. A deeper view of transmitted/founder viruses using 454 whole genome deep sequencing. Retrovirology. 2012;9:O58. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schell JB, Rose NF, Bahl K, Diller K, Buonocore L, Hunter M, et al. Significant protection against high-dose simian immunodeficiency virus challenge conferred by a new prime-boost vaccine regimen. Journal of virology. 2011;85:5764–72. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00342-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schell JB, Bahl K, Rose NF, Buonocore L, Hunter M, Marx PA, et al. Viral vectored granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor inhibits vaccine protection in an SIV challenge model: protection correlates with neutralizing antibody. Vaccine. 2012;30:4233–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rose NF, Roberts A, Buonocore L, Rose JK. Glycoprotein exchange vectors based on vesicular stomatitis virus allow effective boosting and generation of neutralizing antibodies to a primary isolate of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Journal of virology. 2000;74:10903–10. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.10903-10910.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blasco R, Moss B. Selection of recombinant vaccinia viruses on the basis of plaque formation. Gene. 1995;158:157–62. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00149-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pegu P, Vaccari M, Gordon S, Keele BF, Doster M, Guan Y, et al. Antibodies with high avidity to the gp120 envelope protein in protection from simian immunodeficiency virus SIV(mac251) acquisition in an immunization regimen that mimics the RV-144 Thai trial. Journal of virology. 2013;87:1708–19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02544-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds MR, Sacha JB, Weiler AM, Borchardt GJ, Glidden CE, Sheppard NC, et al. TRIM5{alpha} genotype of Rhesus macaques affects acquisition of SIVsmE660 infection after repeated limiting-dose intrarectal challenge. Journal of virology. 2011 doi: 10.1128/JVI.05074-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rolland M, Edlefsen PT, Larsen BB, Tovanabutra S, Sanders-Buell E, Hertz T, et al. Increased HIV-1 vaccine efficacy against viruses with genetic signatures in Env V2. Nature. 2012;490:417–20. doi: 10.1038/nature11519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottardo R, Bailer RT, Korber BT, Gnanakaran S, Phillips J, Shen X, et al. Plasma IgG to Linear Epitopes in the V2 and V3 Regions of HIV-1 gp120 Correlate with a Reduced Risk of Infection in the RV144 Vaccine Efficacy Trial. PloS one. 2013;8:e75665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zolla-Pazner S, deCamp AC, Cardozo T, Karasavvas N, Gottardo R, Williams C, et al. Analysis of V2 antibody responses induced in vaccinees in the ALVAC/AIDSVAX HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. PloS one. 2013;8:e53629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwong PD, Mascola JR. Human antibodies that neutralize HIV-1: identification, structures, and B cell ontogenies. Immunity. 2012;37:412–25. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trkola A, Kuster H, Rusert P, Joos B, Fischer M, Leemann C, et al. Delay of HIV-1 rebound after cessation of antiretroviral therapy through passive transfer of human neutralizing antibodies. Nature medicine. 2005;11:615–22. doi: 10.1038/nm1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barouch DH, Whitney JB, Moldt B, Klein F, Oliveira TY, Liu J, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of potent neutralizing HIV-1-specific monoclonal antibodies in SHIV-infected rhesus monkeys. Nature. 2013;503:224–8. doi: 10.1038/nature12744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar R, Tuen M, Liu J, Nadas A, Pan R, Kong X, et al. Elicitation of broadly reactive antibodies against glycan-modulated neutralizing V3 epitopes of HIV-1 by immune complex vaccines. Vaccine. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kassa A, Dey AK, Sarkar P, Labranche C, Go EP, Clark DF, et al. Stabilizing Exposure of Conserved Epitopes by Structure Guided Insertion of Disulfide Bond in HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein. PloS one. 2013;8:e76139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCoy LE, Quigley AF, Strokappe NM, Bulmer-Thomas B, Seaman MS, Mortier D, et al. Potent and broad neutralization of HIV-1 by a llama antibody elicited by immunization. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2012;209:1091–103. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdel-Motal UM, Sarkis PT, Han T, Pudney J, Anderson DJ, Zhu Q, et al. Anti-gp120 minibody gene transfer to female genital epithelial cells protects against HIV-1 virus challenge in vitro. PloS one. 2011;6:e26473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balazs AB, Bloom JD, Hong CM, Rao DS, Baltimore D. Broad protection against influenza infection by vectored immunoprophylaxis in mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:647–52. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shingai M, Donau OK, Plishka RJ, Buckler-White A, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ, et al. Passive transfer of modest titers of potent and broadly neutralizing anti-HIV monoclonal antibodies block SHIV infection in macaques. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2014;211:2061–74. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manuel ER, Yeh WW, Seaman MS, Furr K, Lifton MA, Hulot SL, et al. Dominant CD8+ T-lymphocyte responses suppress expansion of vaccine-elicited subdominant T lymphocytes in rhesus monkeys challenged with pathogenic simian-human immunodeficiency virus. Journal of virology. 2009;83:10028–35. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01015-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansen SG, Sacha JB, Hughes CM, Ford JC, Burwitz BJ, Scholz I, et al. Cytomegalovirus vectors violate CD8+ T cell epitope recognition paradigms. Science. 2013;340:1237874. doi: 10.1126/science.1237874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]