Abstract

AIM: To compare the efficacy and palatability of 4 L polyethylene glycol electrolyte (PEG) plus sugar-free menthol candy (PEG + M) vs reduced-volume 2 L ascorbic acid-supplemented PEG (AscPEG).

METHODS: In a randomized controlled trial setting, ambulatory patients scheduled for elective colonoscopy were prospectively enrolled. Patients were randomized to receive either PEG + M or AscPEG, both split-dosed with minimal dietary restriction. Palatability was assessed on a linear scale of 1 to 5 (1 = disgusting; 5 = tasty). Quality of preparation was scored by assignment-blinded endoscopists using the modified Aronchick and Ottawa scales. The main outcomes were the palatability and efficacy of the preparation. Secondary outcomes included patient willingness to retake the same preparation again in the future and completion of the prescribed preparation.

RESULTS: Overall, 200 patients were enrolled (100 patients per arm). PEG + M was more palatable than AscPEG (76% vs 62%, P = 0.03). Completing the preparation was not different between study groups (91% PEG + M vs 86% AscPEG, P = 0.38) but more patients were willing to retake PEG + M (54% vs 40% respectively, P = 0.047). There was no significant difference between PEG + M vs AscPEG in adequate cleansing on both the modified Aronchick (82% vs 77%, P = 0.31) and the Ottawa scale (85% vs 74%, P = 0.054). However, PEG + M was superior in the left colon on the Ottawa subsegmental score (score 0-2: 94% for PEG + M vs 81% for AscPEG, P = 0.005) and received significantly more excellent ratings than AscPEG on the modified Aronchick scale (61% vs 43%, P = 0.009). Both preparations performed less well in afternoon vs morning examinations (inadequate: 29% vs 15.2%, P = 0.02).

CONCLUSION: 4 L PEG plus menthol has better palatability and acceptability than 2 L ascorbic acid- PEG and is associated with a higher rate of excellent preparations; Clinicaltrial.gov identifier: NCT01788709.

Keywords: Colonoscopy, Bowel preparation, Efficacy, Tolerability, Menthol

Core tip: Colon preparations are generally poorly tolerated. As a result, suboptimal bowel preparation can occur in as many as 25%-40% of cases. Volume and palatability of the purgative are important determinants of tolerability and adherence and, consequently of efficacy. In this randomized controlled trial, we investigate the efficacy and palatability of two colonic preparations (4 L PEG + menthol candy vs 2 L ascorbic acid supplemented -PEG) given as split-dose and with minimal dietary restrictions. Both preparations were similarly effective at achieving adequate colon preparation but 4 L PEG + M had superior palatability and tolerability and was associated with more excellent ratings.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer continues to be one of the leading causes of death worldwide[1]. A combination of early detection and removal of precursor lesions has proven beneficial in decreasing its incidence and mortality[2,3]. However and despite the advent of several screening modalities[4-7], optical colonoscopy remains the preferred procedure due to its superior diagnostic sensitivity[8], unique capability that allows sampling and removal of luminal pathology[9], and cost-effectiveness[10]. These performance characteristics are, however, highly dependent on the quality of colon preparation[11,12]. Suboptimal preparations are associated with a higher adenoma miss rate, prolonged procedure time, incomplete examinations[11], and increased cost due to need for an earlier repeat examination[13].

Polyethylene glycol electrolyte (PEG) solution is the most commonly used purgative for colon cleansing due to its superior safety profile[14] and high efficacy[15]. In a recent meta-analysis, 4 L split-dose PEG was found to be superior to other bowel preparation comparators suggesting it should be the standard against which new bowel preparations should be compared[15]. However, the unpalatable taste and large volume required for proper cleansing are the most commonly reported reasons to avoid colonoscopy[12]. The preparation is poorly tolerated by patients resulting in incomplete adherence and consequently low-quality preparations[16]. An important development was the concept of dose splitting, where as much as half of the preparation is consumed on the day of the examination, leading to improved efficacy[17] and tolerability[18]. Further refinements[19-21], adjuvants[18,22], and modifications[23-25] of PEG solutions followed. The addition of high-dose ascorbic acid to PEG (AscPEG) improved taste and helped reduce the volume of the preparation to 2 L, making it one of the most commonly prescribed purgatives in the United States. Another simple refinement involves the addition of menthol candy to 4 L split PEG resulting in significant benefit in terms of patient tolerability, acceptability and compliance, and leading to a higher rate of excellent preparations[26]. In this study, we aim to directly compare two tested modifications of the split-dose PEG preparation, namely 4 L PEG with menthol candy (PEG + M) vs 2 L AscPEG.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

The study was conducted at the American University of Beirut Medical Center between February and December 2013. Patients seen in the outpatient clinics requiring elective colonoscopies were approached about the study by their respective endoscopist. Exclusion criteria included age less than 18, pregnant or lactating women, prior intestinal resection or bariatric surgery, chronic renal disease (creatinine clearance < 60 mL/min), severe congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association class III or IV), dehydration, history of severe constipation (< 1 bowel movement every 3 d), chronic laxative abuse, and history of inflammatory bowel disease. Patients with phenylketonuria, known significant gastroparesis, known or suspected bowel obstruction were also excluded. Due to potential for priming by a previous colonoscopy experience in the past 5 years that might alter anticipation and response, patients who had a colonoscopy within the last 5 years were also excluded.

After informed consent was obtained, patients were referred to the study coordinator where they received one of the two regimens based on a previously computer-generated 1:1 randomization list. Detailed written instructions and verbal explanations were provided to all patients. On the day of the colonoscopy, patients were interviewed by an independent investigator prior to the procedure. Colonoscopies were performed by one of five endoscopists blinded to the preparation. All exams were performed under conscious sedation in the endoscopy unit between 9:00 am and 4:00 pm. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the American University of Beirut on December 2012, and the study was registered with Clinicaltrial.gov identifier: NCT01788709.

Preparation instructions

Detailed written instructions and verbal explanations were provided to all patients at the time of colonoscopy scheduling, emphasizing the importance of complete intake of the solution to ensure a more effective procedure. On the day preceding the colonoscopy, patients were allowed to consume an unrestricted breakfast and lunch till 3 pm, followed by a full-fluid dinner (e.g., milk, water, soda, clear broth, tea, or yoghurt) until 7 pm. Only clear fluids were allowed after 7 pm (e.g., water, clear soda, tea).

Patients in the first arm received 4 L PEG (Fortrans®, Ibsen, Paris, France) divided into 2 L consumed from 7-9 pm on the day preceding the colonoscopy, and 2 L on the day of the colonoscopy, taken no earlier than 4 h before the scheduled appointment, and completed a minimum of 90 min before the procedure. Patients in this arm were provided with sugar-free, colorless, menthol candy (Halls®, Cadbury Adams, NJ, United States) and instructed to suck on a candy while drinking the PEG solution (PEG + M). Patients in the second arm received 2 L reduced-volume ascorbic acid-supplemented PEG-electrolyte solution (AscPEG) (MoviPrep®, Norgine, Harefield, United Kingdom) mixed according the manufacturer’s instructions plus 1L of clear fluids of the patient’s choice and dose-split over 2 d. The first liter of AscPEG was consumed at 7 pm the day before colonoscopy with a minimum of 500 mL of clear fluids, and another 1 L of AscPEG plus a minimum of 500 mL of clear fluids on the day of the colonoscopy, to be completed no more than 4 h before the procedure and at least 90 min before the procedure.

Data collection

Immediately before colonoscopy, patients were interviewed by an independent investigator. Patients were asked to report their perception of the solution’s palatability by checking a linear scale on a boxed diagram from 1 to 5 (disgusting, moderately poor taste, slightly poor taste, acceptable, and tasty) and express the degree of willingness to take the preparation again in the future. An assessment of compliance and adherence was also performed with the volume remaining of the solution recorded. The quality of bowel cleansing was graded immediately following colonoscopy by the performing endoscopist who was blinded to the preparation assigned. Endoscopists were asked to provide a score for each patient using the modified Aronchick scale and Ottawa scale.

Study design and endpoints

The primary end points of the study were the quality of the preparation and the palatability of the administered solution. Secondary endpoints included willingness to retake the same preparation again in the future, and completion of the preparation. The solutions were considered palatable if they received 4 or 5 on the 5-point palatability scale (acceptable or tasty) and unpalatable for a score of 1-3 (disgusting, moderately poor taste, or slightly poor taste). Patients with an Aronchick score of excellent or good were considered to have an adequate preparation, whereas those with poor, inadequate, and fair were considered to have an inadequate preparation. On the Ottawa scale, segmental scores were collected and an overall score was calculated. A total score of > 8 was considered to indicate an inadequate preparation and a score of ≤ 7 was deemed adequate. Preparations with a total score of ≤ 4 were considered excellent, provided that no individual colonic segment received a score higher than 1. Patients were considered to have completed the preparation if they consumed ≥ 90% of the preparation volume.

Sample size calculation was based on published data showing 90% adequate preparation with menthol-enhanced PEG (PEG + M)[26] and 65%-85% (average: 75%) for reduced volume AscPEG[24,27,28]. Using α of 0.05 and a power of 0.80, the sample size required to show significance was calculated to be 97 patients per arm. Hence, it was decided to recruit 100 patients per arm taking into account possible withdrawals. SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States) was used for data entry and analysis. The proportions in 2 × 2 contingency tables were compared by the Chi-square test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. The primary investigator and co-authors had access to the study data and had reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

RESULTS

Two hundred patients successfully completed the study with 100 patients enrolled in each arm. Nine patients cancelled appointments for reasons unrelated to the quality or taste of the preparation and were replaced by a similar number of patients. Additionally, 4 patients took a different preparation or unauthorized adjuvants, 3 patients were found to have IBD at the time of colonoscopy, 1 patient forgot to use the menthol candy, 1 patient was found to have a history of laxative abuse, and 1 patient could not be scoped beyond the left colon. All of these cases were excluded. Two patients both belonging to the AscPEG arm had cancelled procedure due to bad preparation quality. These patients were included in the study and received the worst scoring on both scales. The mean age of enrolled patients was 54.5 ± 13.7 years (range: 21-85) with 52% males. Patients’ characteristics and indications for colonoscopy were not different between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| PEG + M | AscPEG | P value | |

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 55 ± 13.8 | 54 ± 13.7 | 0.88 |

| Male subjects | 54% | 50% | 0.74 |

| BMI (mean ± SD, kg/m2) | 27 ± 4.7 | 27 ± 4.9 | 0.54 |

| Indication | |||

| Screening | 46% | 43% | 0.70 |

| Hematochezia | 13% | 13% | 0.95 |

| Abdominal pain | 14% | 12% | 0.75 |

| Change in bowel habits | 10% | 6% | 0.41 |

| Surveillance | 7% | 9% | 0.53 |

| Positive FOBT | 4% | 5% | 0.74 |

| Weight loss | 2% | 1% | 0.27 |

| Anemia | 2% | 5% | 0.31 |

| Diverticular disease | 0% | 2% | 0.20 |

| Others | 2% | 4% | 0.28 |

PEG + M: PEG electrolyte solution + menthol; AscPEG: Ascorbic acid PEG electrolyte solution.

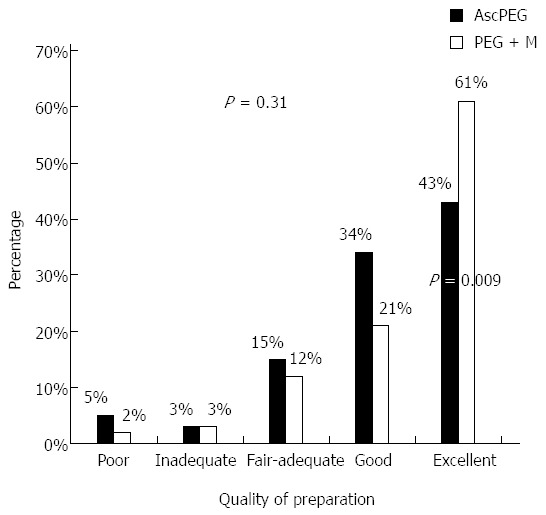

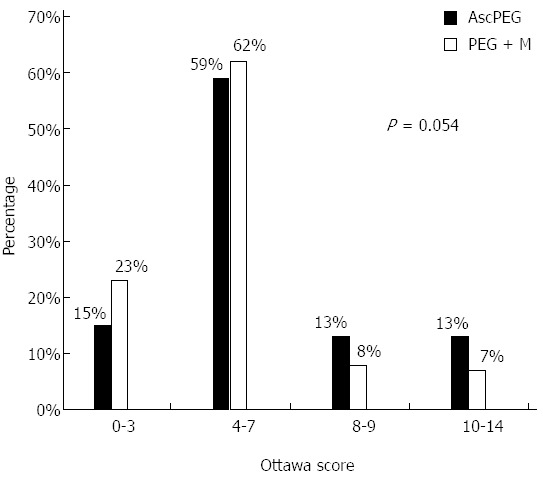

There was no difference between the two preparations in the rate of adequate preparations on the Aronchick scale (82% for PEG + M vs 77% for AscPEG, P = 0.31) (Figure 1). On the same scale, a significantly higher number of patients receiving PEG + M were found to have an excellent preparation (61% vs 43% AscPEG, P = 0.009). The mean score on the Ottawa scale was better for PEG + M vs AscPEG (5.1 ± 2.4 vs 5.8 ± 3.0, P = 0.09) as was the rate of adequate preparations (overall score ≤ 7: 85% vs 74%, P = 0.054) but these were not statistically significant (Figure 2). Table 2 shows the Ottawa scores according to colonic segment. Using a segmental score of 0-2 as indication of an adequate cleansing[29] there was no significant difference between preparations in the right and mid-colon. However, PEG + M was superior in the left colon (94% for PEG + M vs 81% for AscPEG, P = 0.005).

Figure 1.

Quality of bowel preparation on the modified Aronchick scale. P-value for the difference between AscPEG and PEG + M Aronchick scores is 0.31; P-value for the difference between excellent results with PEG + M and AscPEG is 0.009. PEG + M: PEG electrolyte solution + menthol; AscPEG: Ascorbic acid PEG electrolyte solution.

Figure 2.

Overall preparation score according to the Ottawa score (a lower score indicates a better preparation). P-value for the difference between AscPEG and PEG + M Ottawa scores is 0.054. PEG + M: PEG electrolyte solution + menthol; AscPEG: Ascorbic acid PEG electrolyte solution.

Table 2.

Percentage adequate preparation by colonic segment using the Ottawa scale

| PEG + M | AscPEG | P value | |

| Right | 84% | 79% | 0.340 |

| Mid | 95% | 89% | 0.110 |

| Left | 94% | 81% | 0.0051 |

| Overall | 85% | 74% | 0.054 |

Significant P-value. PEG + M: PEG electrolyte solution + menthol; AscPEG: Ascorbic acid PEG electrolyte solution.

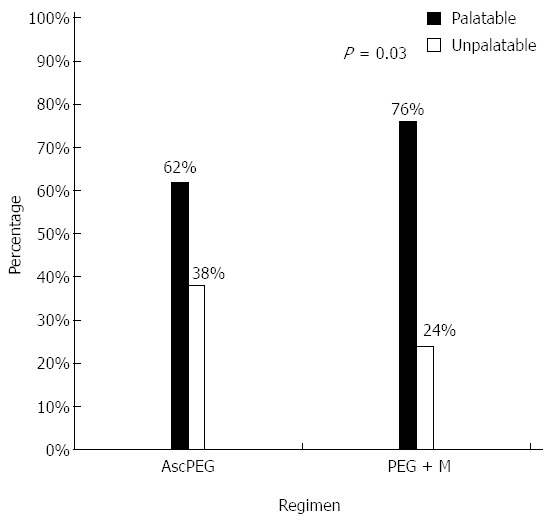

PEG + M was significantly more palatable than AscPEG (76% vs 62%, P = 0.03) (Figure 3). Similarly, a significantly higher number of patients were willing to retake PEG + M again in the future compared to AscPEG (54% vs 40%, P = 0.047). Patients in the PEG + M arm had a lower rate of non-compliance with the prescribed volume compared to AscPEG, but this difference was not significant (9% vs 14%, P = 0.38).

Figure 3.

Palatability of the colon preparation (score ≤ 3: Unpalatable; 4 or 5: Palatable). P-value for the difference in palatability between AscPEG and PEG + M is 0.03. PEG + M: PEG electrolyte solution + menthol; AscPEG: Ascorbic acid PEG electrolyte solution.

There was no difference in the number of patients undergoing colonoscopy in the afternoon between study groups (40% PEG + M vs 35% AscPEG, P = NS). However, PM colonoscopies had a higher rate of inadequate preparation compared to AM colonoscopies (29% vs 15.2%, P = 0.02) with no significant difference between study groups. On univariate analysis, BMI, age, and gender were not associated with inadequate preparations.

DISCUSSION

The ideal bowel preparation should be simple to administer, palatable, well tolerated, safe and effective. Despite the unquestionable need for adequate colon cleansing, suboptimal bowel preparation occurs with surprising frequency in as many as 25% to 40% of cases[12]. Inadequate bowel preparation is associated with canceled procedures, prolonged procedure time, incomplete examination, increased cost, and missed pathology. Split-dose 4 L PEG is superior to other comparator preparations and is considered the gold standard against which other regimens should be compared[15,30]. Although highly effective even with minimal dietary restriction, split-dose 4 L PEG is limited by the high volume and unpleasant taste leading to poor acceptability by patients. To circumvent the volume and taste issue, a new formulation of PEG including ascorbic acid was developed (AscPEG). The added megadose of ascorbic acid is not completely absorbed, exerting an osmotic effect in the colon thereby reducing the necessary effective volume of cleansing solution to 2 L. When compared to split-dose 4 L PEG in a “quasi-randomized” study, AscPEG was similar in achieving adequate bowel preparation[28]. However, more excellent preparations were reported in the 4 L PEG arm (79% vs 52% for AscPEG, P < 0.001). No significant difference was found between the two preparations in terms of taste, tolerability or acceptability.

Another successful way to circumvent the aforementioned limitation of the split-dose 4 L PEG standard was the simple use of menthol candy (PEG + M) as an adjunct resulting in enhanced palatability, acceptability as well as a higher number of excellent preparations[26]. The results of this study confirm that this simple addition not only results in a high rate of adequate preparations, but also in improved palatability and acceptability (including willingness to retake in the future) over AscPEG so far considered a more patient-friendly preparation in terms of volume and taste.

The importance of this study is in showing that split-dose PEG + M is arguably the new and improved gold standard for combining efficacy (providing more excellent preparations), palatability, tolerability, and acceptability. Our study did not show a significant difference between the two preparations on the Ottawa scale perhaps due a type II error and/or to inherent limitations of the Ottawa scale. Current bowel preparation scales have significant limitations in distinguishing effective preparations and, with the exception of the relatively simple yet highly subjective modified Aronchick scale, in providing a validated and clinically relevant separation between distinct stages of the full spectrum of bowel cleanliness. For example, the Ottawa scale is overly sensitive to the presence of residual liquid in the colon (even when that liquid is clear) leading to a final score that may not necessarily reflect visualization of the mucosa[31] and which is not readily convertible into the relevant subjective ratings generally used by endoscopists. In our study this limitation of the Ottawa scale was evident when we tried defining broad categories (adequate vs inadequate or excellent vs less than excellent) based on numerical clustering. In practice, clinicians are not interested in such complex scoring systems and prefer to rely instead on a simple subjective dichotomous scoring system: adequate vs inadequate. The limitations of the various bowel preparations scales and the non-inferiority design of most studies of bowel preparation are equally important considerations as small, yet important differences, may go unnoticed in clinical trials.

A recent editorial by Rex ushered in an era of increased expectations for the efficacy of bowel preparations noting that “efficacy and tolerability are related, and together constitute the main ingredients of effectiveness”[30]. The performance characteristics of colonoscopy are highly dependent on the quality of the preparation. A recent study showed that a fair bowel preparation is associated with 18-fold increase in the odds of receiving a post-colonoscopy surveillance recommendation that is inconsistent with current guidelines[32]. Narrowing the gap by shifting to safe, palatable, tolerable, and highly effective preparations is therefore a necessity that appears increasingly achievable.

Our study has few limitations. The study was conducted at a single center limiting the generalizability of the results and the sample size may have underestimated some true differences between the two interventions. Patients receiving PEG + M were provided with free packets of sugar-free menthol candy and it is unclear if, outside of clinical trials, patients will realize the value of this simple addition, purchase the menthol candy (retail price of about $2 for a packet of 25 candies), and follow the simple instructions for use. An accurate estimate of patient compliance to dietary changes was not recorded but is likely a minimal factor given the largely unrestricted diet. Lastly, we did not examine intra or interobserver variability, however, a scoring bias is unlikely given the random study design and the blinding of the endoscopists.

In summary, this study confirms that both split-dose preparations are effective at achieving adequate colon cleansing with minimal dietary restrictions. Menthol-enhanced split-dose 4 L PEG (PEG + M) was superior to split-dose 2 L AscPEG in terms of palatability, acceptability, and excellence in quality. The simple addition of menthol candy is an easy and safe strategy and leads to improved effectiveness of split-dose 4L PEG and to a favorable quality improvement that should further enhance the power of colonoscopy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Robert H Habib for assistance with the statistical analysis.

COMMENTS

Background

Colon preparations are poorly tolerated.

Research frontiers

Improving palatability and tolerability of bowel purgative solutions are key elements to effective bowel cleansing.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Both bowel preparations are effective. However, polyethylene glycol electrolyte (PEG) plus menthol candy is more palatable than ascorbic-acid PEG and is associated with better tolerability and high quality bowel preparation.

Applications

The simple adjuvant use of menthol candy with PEG improves tolerability and adherence.

Peer-review

The authors have performed a well conducted single blind randomized study comparing menthol-enhanced PEG vs PEG-ascorbic acid for colonoscopy preparation. They’ve carried out an important study in the realm of colonoscopy bowel preparation and have done an excellent job of conveying its importance not only in regards to the necessity of an effective bowel preparation for a good colonoscopy exam, but the role palatability has in this respect and the implications of a poor exam including inappropriate surveillance exam intervals. The study is novel in that examination of two well-tolerated and effective bowel preparations have not been examined head-to-head previously, with findings that should have a significant impact in the future administration of an effective and tolerable bowel preparation.

Footnotes

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: August 8, 2014

First decision: August 27, 2014

Article in press: November 19, 2014

P- Reviewer: Greenspan M, Ianiro G, Tang D S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O’Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Bond JH, Panish JF. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977–1981. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Bond J, Dash C, Giardiello FM, Glick S, Johnson D, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570–1595. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkin W, Dadswell E, Wooldrage K, Kralj-Hans I, von Wagner C, Edwards R, Yao G, Kay C, Burling D, Faiz O, et al. Computed tomographic colonography versus colonoscopy for investigation of patients with symptoms suggestive of colorectal cancer (SIGGAR): a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, Laheij RJ, van Oijen MG, Fockens P, van Krieken HH, Verbeek AL, Jansen JB, Dekker E. Random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer in a screening population. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:82–90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sacher-Huvelin S, Coron E, Gaudric M, Planche L, Benamouzig R, Maunoury V, Filoche B, Frédéric M, Saurin JC, Subtil C, et al. Colon capsule endoscopy vs. colonoscopy in patients at average or increased risk of colorectal cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1145–1153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segnan N, Armaroli P, Bonelli L, Risio M, Sciallero S, Zappa M, Andreoni B, Arrigoni A, Bisanti L, Casella C, et al. Once-only sigmoidoscopy in colorectal cancer screening: follow-up findings of the Italian Randomized Controlled Trial--SCORE. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1310–1322. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, Bond J, Burt R, Ferrucci J, Ganiats T, Levin T, Woolf S, Johnson D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:544–560. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rex DK, Johnson DA, Lieberman DA, Burt RW, Sonnenberg A. Colorectal cancer prevention 2000: screening recommendations of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:868–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vijan S, Hwang EW, Hofer TP, Hayward RA. Which colon cancer screening test? A comparison of costs, effectiveness, and compliance. Am J Med. 2001;111:593–601. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00977-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:378–384. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02776-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharara AI, Abou Mrad RR. The modern bowel preparation in colonoscopy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42:577–598. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rex DK, Imperiale TF, Latinovich DR, Bratcher LL. Impact of bowel preparation on efficiency and cost of colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1696–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connor A, Tolan D, Hughes S, Carr N, Tomson C. Consensus guidelines for the safe prescription and administration of oral bowel-cleansing agents. Gut. 2012;61:1525–1532. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enestvedt BK, Tofani C, Laine LA, Tierney A, Fennerty MB. 4-Liter split-dose polyethylene glycol is superior to other bowel preparations, based on systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1225–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lichtenstein GR, Cohen LB, Uribarri J. Review article: Bowel preparation for colonoscopy--the importance of adequate hydration. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:633–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aoun E, Abdul-Baki H, Azar C, Mourad F, Barada K, Berro Z, Tarchichi M, Sharara AI. A randomized single-blind trial of split-dose PEG-electrolyte solution without dietary restriction compared with whole dose PEG-electrolyte solution with dietary restriction for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:213–218. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Sayed AM, Kanafani ZA, Mourad FH, Soweid AM, Barada KA, Adorian CS, Nasreddine WA, Sharara AI. A randomized single-blind trial of whole versus split-dose polyethylene glycol-electrolyte solution for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:36–40. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clarkston WK, Tsen TN, Dies DF, Schratz CL, Vaswani SK, Bjerregaard P. Oral sodium phosphate versus sulfate-free polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution in outpatient preparation for colonoscopy: a prospective comparison. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:42–48. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamilton D, Mulcahy D, Walsh D, Farrelly C, Tormey WP, Watson G. Sodium picosulphate compared with polyethylene glycol solution for large bowel lavage: a prospective randomised trial. Br J Clin Pract. 1996;50:73–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Palma JA, Rodriguez R, McGowan J, Cleveland Mv. A randomized clinical study evaluating the safety and efficacy of a new, reduced-volume, oral sulfate colon-cleansing preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2275–2284. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdul-Baki H, Hashash JG, Elhajj II, Azar C, El Zahabi L, Mourad FH, Barada KA, Sharara AI. A randomized, controlled, double-blind trial of the adjunct use of tegaserod in whole-dose or split-dose polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:294–300; quiz 334, 336. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Froehlich F, Fried M, Schnegg JF, Gonvers JJ. Low sodium solution for colonic cleansing: a double-blind, controlled, randomized prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:579–581. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(92)70521-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bitoun A, Ponchon T, Barthet M, Coffin B, Dugué C, Halphen M. Results of a prospective randomised multicentre controlled trial comparing a new 2-L ascorbic acid plus polyethylene glycol and electrolyte solution vs. sodium phosphate solution in patients undergoing elective colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1631–1642. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hjelkrem M, Stengel J, Liu M, Jones DP, Harrison SA. MiraLAX is not as effective as GoLytely in bowel cleansing before screening colonoscopies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:326–332.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharara AI, El-Halabi MM, Abou Fadel CG, Sarkis FS. Sugar-free menthol candy drops improve the palatability and bowel cleansing effect of polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:886–891. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ell C, Fischbach W, Bronisch HJ, Dertinger S, Layer P, Rünzi M, Schneider T, Kachel G, Grüger J, Köllinger M, et al. Randomized trial of low-volume PEG solution versus standard PEG + electrolytes for bowel cleansing before colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:883–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corporaal S, Kleibeuker JH, Koornstra JJ. Low-volume PEG plus ascorbic acid versus high-volume PEG as bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1380–1386. doi: 10.3109/00365521003734158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katz PO, Rex DK, Epstein M, Grandhi NK, Vanner S, Hookey LC, Alderfer V, Joseph RE. A dual-action, low-volume bowel cleanser administered the day before colonoscopy: results from the SEE CLEAR II study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:401–409. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rex DK. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: entering an era of increased expectations for efficacy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:458–462. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerard DP, Foster DB, Raiser MW, Holden JL, Karrison TG. Validation of a new bowel preparation scale for measuring colon cleansing for colonoscopy: the chicago bowel preparation scale. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2013;4:e43. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2013.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menees SB, Elliott E, Govani S, Anastassiades C, Judd S, Urganus A, Boyce S, Schoenfeld P. The impact of bowel cleansing on follow-up recommendations in average-risk patients with a normal colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:148–154. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]