ABSTRACT

Purpose

Aerobic fitness, as reflected by maximal oxygen (O2) uptake (V˙O2max), is impaired in poorly controlled patients with type 1 diabetes. The mechanisms underlying this impairment remain to be explored. This study sought to investigate whether type 1 diabetes and high levels of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) influence O2 supply including O2 delivery and release to active muscles during maximal exercise.

Methods

Two groups of patients with uncomplicated type 1 diabetes (T1D-A, n = 11, with adequate glycemic control, HbA1c <7.0%; T1D-I, n = 12 with inadequate glycemic control, HbA1c >8%) were compared with healthy controls (CON-A, n = 11; CON-I, n = 12, respectively) matched for physical activity and body composition. Subjects performed exhaustive incremental exercise to determine V˙O2max. Throughout the exercise, near-infrared spectroscopy allowed investigation of changes in oxyhemoglobin, deoxyhemoglobin, and total hemoglobin in the vastus lateralis. Venous and arterialized capillary blood was sampled during exercise to assess arterial O2 transport and factors able to shift the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve.

Results

Arterial O2 content was comparable between groups. However, changes in total hemoglobin (i.e., muscle blood volume) was significantly lower in T1D-I compared with that in CON-I. T1D-I also had impaired changes in deoxyhemoglobin levels and increase during high-intensity exercise despite normal erythrocyte 2,3-diphosphoglycerate levels. Finally, V˙O2max was lower in T1D-I compared with that in CON-I. No differences were observed between T1D-A and CON-A.

Conclusions

Poorly controlled patients displayed lower V˙O2max and blunted muscle deoxyhemoglobin increase. The latter supports the hypotheses of increase in O2 affinity induced by hemoglobin glycation and/or of a disturbed balance between nutritive and nonnutritive muscle blood flow. Furthermore, reduced exercise muscle blood volume in poorly controlled patients may warn clinicians of microvascular dysfunction occurring even before overt microangiopathy.

Key Words: AEROBIC FITNESS, GLYCATED HEMOGLOBIN, OXYGEN DELIVERY, OXYGEN RELEASE, SKELETAL MUSCLE

The beneficial effects of physical activity and the advantages of good physical fitness are well established both in healthy individuals and in those with chronic disease (20,21). Aerobic fitness, as measured by maximal oxygen (O2) uptake (V˙O2max), is a strong predictor of cardiovascular risk (2). In patients with type 1 diabetes, poor fitness represents an important barrier to regular physical activity (9). Consequently, better understanding of the underlying factors involved in the possible impairment of V˙O2max in patients with type 1 diabetes is warranted.

Low aerobic fitness levels have been reported in several (28,32), albeit not all (21,39), studies in adults with type 1 diabetes and seem to be associated with poor glycemic control, as reflected by high glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels (5,24,30). A high HbA1c level is indeed an important factor in the initiation and progression of micro- and macrovascular complications. In turn, these complications may alter the functioning of tissues that are important for exercise adaptations, such as blood vessels, lungs, and heart (11,41) and, consequently, reduce V˙O2max.

However, there may be other factors involved in the impairment of aerobic fitness observed in individuals with poor glycemic control. In this respect, the HbA1c– V˙O2max relation has been found even in the absence of diabetic complications in young patients with type 1 diabetes (24,35). O2 supply, including arterial O2 delivery and O2 release (i.e., oxyhemoglobin (O2Hb) dissociation) to active muscles, is a well-established factor influencing V˙O2max in healthy subjects or subjects with a chronic disease (17,29). In adolescents with type 1 diabetes, one study reported reduction in forearm blood flow after local exercise (rhythmic handgrip) despite the absence of any otherwise clinically detectable vascular disorders (33). To our knowledge, arterial O2 transport capacity has never been investigated during exercise in patients with type 1 diabetes and with different levels of HbA1c.

Several in vitro studies suggest possibly increased O2Hb affinity (i.e., a leftward shift of the O2 dissociation curve) and/or decreased sensitivity of hemoglobin to the allosteric effect of organic phosphates as a result of hemoglobin glycation at a degree corresponding to HbA1c levels in patients with poor glycemic control (i.e., 8%) (10,25,26,36). Some further insight into muscle O2Hb dissociation in type 1 diabetes is required, particularly in vivo during maximal exercise and in accordance with HbA1c levels. In this respect, near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) allows noninvasive and functional monitoring of changes in skeletal muscle oxygenation including O2Hb dissociation (18). Besides hemoglobin glycation, it is important to take into account the erythrocyte 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG) level. This stimulus for a rightward shift of the O2Hb dissociation curve has been found to be, contradictorily, either reduced (15,16) or elevated in patients with type 1 diabetes (8), especially in cases of chronically impaired glycemic control (1).

Therefore, we aimed to determine whether O2 delivery and/or release to an active muscle during maximal exercise is altered in patients with uncomplicated type 1 diabetes and high levels of HbA1c and whether any subsequent relation to impairment in V˙O2max exists.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A written informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion in this study, which was approved by the North Western IV regional ethics committee (N° EudraCT, 2009-A00746-51). Twenty-three patients, age 18–40 yr, who had type 1 diabetes for at least 1 yr and were free from vascular complications, volunteered to participate in this study (Table 1). The absence of microvascular (retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy) and macrovascular (high blood pressure, coronary disease, peripheral arteriopathy) complications was carefully checked by a clinician during the initial examination. The patients were then divided into two groups according to their HbA1c levels measured at inclusion, as follows: adequate glycemic control, T1D-A (n = 11; HbA1c <7% (53 mmol·mol−1)); and inadequate glycemic control, T1D-I (n = 12; HbA1c >8% (64 mmol·mol−1)). Two control groups, CON-A and CON-I, composed of healthy subjects age 18–40 yr, were recruited (as described in the following section) to strictly match the T1D-A and T1D-I groups, respectively.

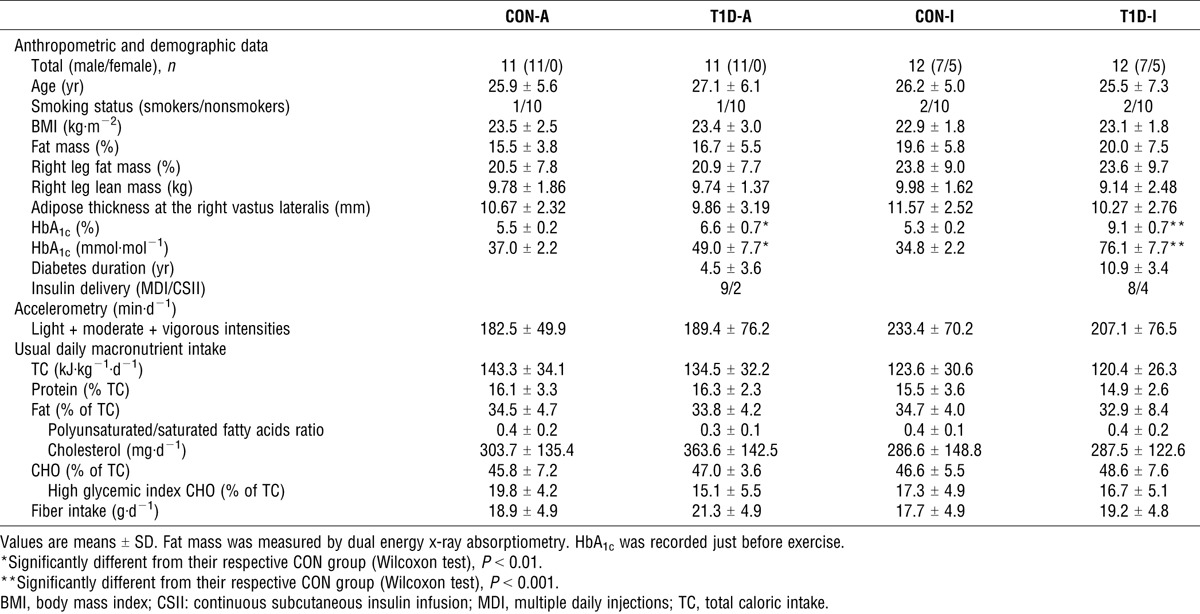

TABLE 1.

Participants’ characteristics.

Selection process of the healthy control subjects.

Healthy participants were selected from a list (n = 250) drawn from patients’ friends and contacts. Each healthy control was chosen to strictly match a patient with type 1 diabetes according to the following preestablished ranges or values: gender, same as the case patient; age, ±7 yr; body mass index, ±4 kg·m−2; moderate-to-vigorous physical activity levels, ±1 h when the patients’ physical activity category was 0 h·wk−1, ±2 h for category 2–6 h·wk−1, ±4 h for category >6 h·wk−1, pairs of patient/control being in the same category, and tobacco status, grouped according to no smoking, <10 cigarettes a day, and >10 cigarettes a day. The healthy controls chosen were then recruited after an oral glucose tolerance test (75 g). Individuals were excluded if they had a fasting blood glucose level of >6.05 mM or an abnormal glucose tolerance test result using World Health Organization criteria (14). The similarity of body composition and physical activity levels between groups was then accurately checked using dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (Hologic, Inc., Waltham, MA) and accelerometry (ActiGraph, model GT1M) over seven consecutive days, respectively (Table 1).

Besides physical activity levels, we added an assessment of lifestyle diet. Dietary data were based on a 3-d diary (based on two weekdays and one weekend day). Written instructions were given to provide detailed information about the quantity and quality of all items consumed. The patients were then interviewed by a research-trained dietitian, who gathered information to supplement the diaries.

Laboratory testing.

Subjects were requested to refrain from vigorous physical activity for 48 h before the test and from using tobacco in the morning of the test. Patients with type 1 diabetes received their usual morning insulin bolus, and all subjects consumed a breakfast (providing 8.5% ± 3.4% proteins, 41.4% ± 16.4% lipids, and 50.1% ± 15.8% CHO) based on their usual breakfast and previously agreed upon by a dietician. The exercise test began 3.8 ± 0.6 h after breakfast. After a 2-min resting period sitting on the cycle ergometer (Excalibur Sport; Lode BV, Groningen, Netherlands), the test started at 30 W and continued with a 20-W increment every 2 min until exhaustion.

Cardiopulmonary response.

An ECG (Ergocard®; Medisoft, Dinant, Belgium) was performed at rest and continually monitored throughout the exercise test by a cardiologist.

Pulmonary gas exchanges were measured continuously throughout exercise (breath-by-breath system, Ergocard®). V˙O2max was determined as the highest 15-s average value during the exercise test. Validation of V˙O2max was obtained at the termination of the test when three of the following five criteria were attained: 1) V˙O2 increase of <100 mL·min−1 with the 20-W increase in power output, 2) an HR >90% of the theoretical HRmax (210 − 0.65 × age), 3) an RPE score ≥19, 4) blood lactate >8 mM, and 5) an RER >1.1 (4). According to these criteria, all subjects achieved their V˙O2max (Table 2).

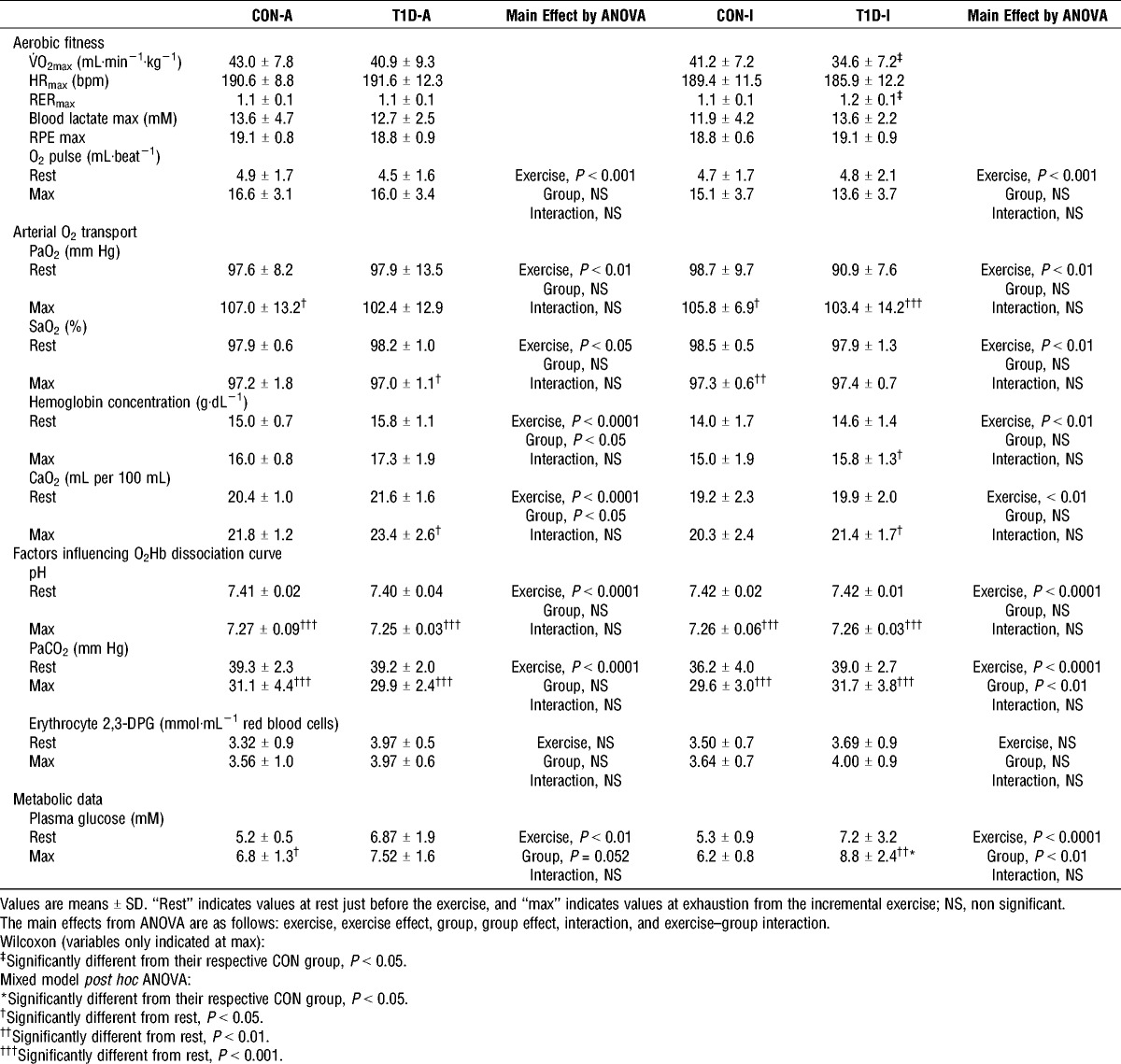

TABLE 2.

Cardiopulmonary and metabolic data from participants during incremental maximal exercise.

The O2 pulse (mL·beat−1) was calculated as the ratio between O2 consumption and HR and was used as an indicator of stroke volume during submaximal and maximal exercise (40).

NIRS measurements.

Subjects were equipped with an NIRS probe to monitor the absorption of light across muscle tissues throughout the exercise test (Oxymon Mk III; Artinis Medical Systems, Zetten, The Netherlands). The emitter-and-detector pair was placed on the belly of the right vastus lateralis muscle, midway between the lateral epicondyle and greater trochanter of the femur. The vastus lateralis muscle is highly active during cycling (23), making it suitable for examining exercise-induced changes in active muscle oxygenation. Adipose tissue thickness has been reported to have substantial confounding influence on in vivo NIRS measurements (18). Therefore, we ensured that the vastus lateralis skinfold was <1.5 cm and that fat mass percentage in the right leg was comparable between groups (Table 1). The interoptode distance was 40 mm. NIRS data were collected with a sampling frequency of 10 Hz.

The Beer–Lambert law was used to calculate changes in tissue oxygenation O2Hb (ΔO2Hb) and deoxyhemoglobin (ΔHHb) across time using optical densities from two continuous wavelengths of NIR light (780 and 850 nm). The change in total hemoglobin (ΔTHb), i.e., the arithmetic sum of ΔO2Hb and ΔHHb, was used as an index of change in regional blood volume (19). ΔHHb was used as a sensitive reflection of relative tissue deoxygenation due to O2 extraction because this measure is closely associated with changes in venous O2 content and is less sensitive to ΔTHb than ΔO2Hb (19). NIRS measurements were normalized to reflect changes from the 1-min baseline period immediately before beginning the exercise protocol (arbitrarily defined as 0 μM) to express the magnitudes of changes throughout exercise.

The use and limitations of NIRS have been extensively reviewed (7,18). Noteworthy, the NIRS technique is unable to differentiate between the amount of O2 released by both hemoglobin and myoglobin because the absorbency signals of these two chromophores overlap in the NIR range. On the basis of data available on hemoglobin/myoglobin ratio in human muscles, one can estimate that myoglobin represents a confounding factor of 10% of the whole hemoglobin signal (18). Consequently, it can be assumed that most of the NIRS signal reflects changes in absorption of ΔO2Hb and ΔHHb (18).

Blood analyses.

Venous blood samples were collected from a forearm catheter at rest and at maximal exercise. HbA1c was measured at rest from EDTA blood (HPLC assay, VARIANT2 Turbo; Bio-Rad) (Table 1). At rest and maximal exercise, fluorinated and heparinized samples were used to analyze blood glucose (hexokinase enzymatic assay, Modular automat) and erythrocyte 2,3-DPG (spectrophotometry; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), respectively.

At rest and immediately at exhaustion, a microcapillary arterialized earlobe blood sample (vasodilator pomade applied 5 min before sampling) was collected to analyze lactate (amperometry, on ABL800 radiometer), factors able to modify the O2Hb dissociation curve (pH, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2), by potentiometry, on ABL800 radiometer), and components of arterial O2 content (CaO2) (27) (arterial O2 saturation (SaO2) by spectrophotometry, partial pressure of O2 (PaO2) by amperometry, hemoglobin concentration by spectrophotometry, on ABL800 Radiometer). CaO2 was calculated as the sum of bound (1.39 (hemoglobin) × SaO2) and dissolved O2 (0.003 PaO2).

Statistical analyses.

Statistics were computed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Results are reported as means ± SD unless otherwise indicated. Normality was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Demographic, anthropometric, and aerobic fitness data were compared between patients with type 1 diabetes and their respective group of healthy controls using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs test. NIRS data, arterialized O2 transport, and blood factors able to influence the O2Hb dissociation curve were compared between patients with type 1 diabetes and their respective control group using a linear mixed model for repeated measurements. In this model, the fixed effects were the group effect (i.e., T1D-A vs CON-A and T1D-I vs CON-I), the exercise effect (repeated measurements corresponding to relative intensity levels—10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100% of V˙O2max)—and the group–exercise interaction. The mixed model is an extension of the classical ANOVA allowing handling of correlations between repeated measurements. The choice of the covariance pattern model was based on the Akaike information criterion. The influence of each individual on the results was investigated using the Cook distance. If significant main effects or an interaction was observed with ANOVA, Bonferroni post hoc pairwise comparisons were applied. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to detect correlations between two continuous parametric variables. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Subjects’ characteristics.

Demographic and physical activity data from patients with type 1 diabetes and their matched healthy controls are summarized in Table 1. On the day of the exercise test, HbA1c levels ranged between 8% and 10.3% in T1D-I and between 5.5% and 7.5% in T1D-A. The latter is explained by the fact that, for four of the 11 patients in the T1D-A group, HbA1c changed from levels <7.0% the day of inclusion to levels between 7.0% and 7.5% on the day of exercise test. Plasma glucose concentrations increased during exercise in all groups (Table 2). None of the patients with type 1 diabetes became hypoglycemic during exercise.

V˙O2max.

T1D-I had lower V˙O2max than CON-I despite comparable levels of habitual physical activity (Table 1) as well as comparable HR achieved at exhaustion (Table 2). No significant difference in V˙O2max was observed between T1D-A and CON-A (Table 2).

Arterial O2 transport.

CaO2, and its components ([hemoglobin], SaO2, PaO2), did not differ significantly between T1D-I and CON-I during the exercise test. T1D-A had higher CaO2 compared with CON-A, which could be explained by higher hemoglobin concentration. Levels and exercise-induced changes in PaO2, SaO2, and O2 pulse were not significantly different between the groups (Table 2).

Muscle oxygenation and deoxygenation profiles.

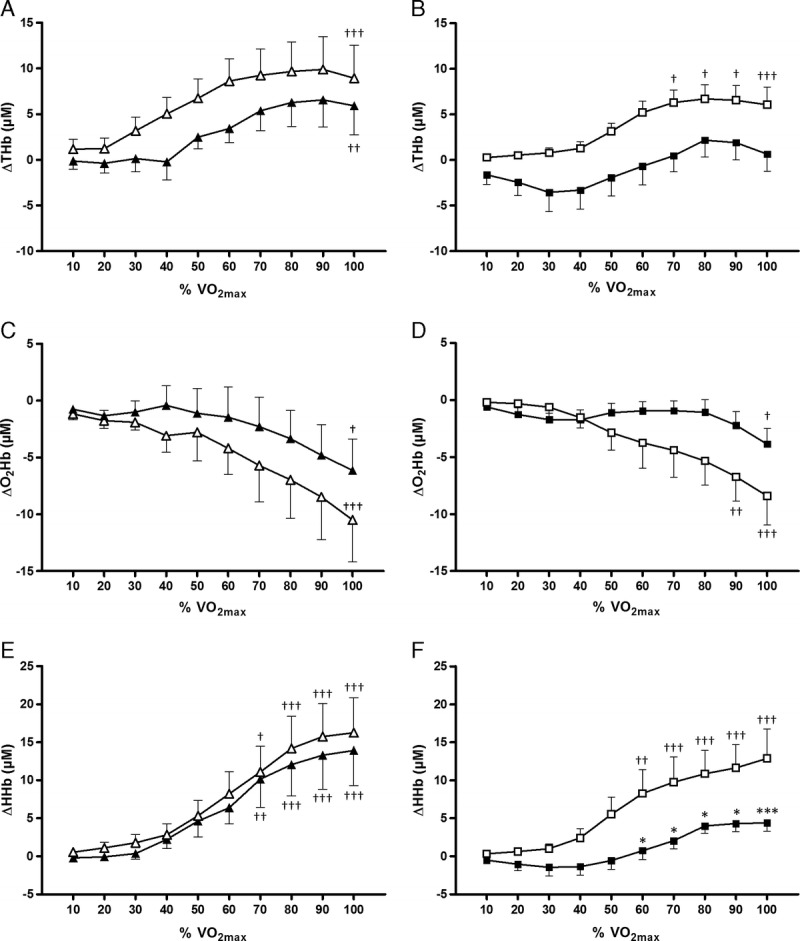

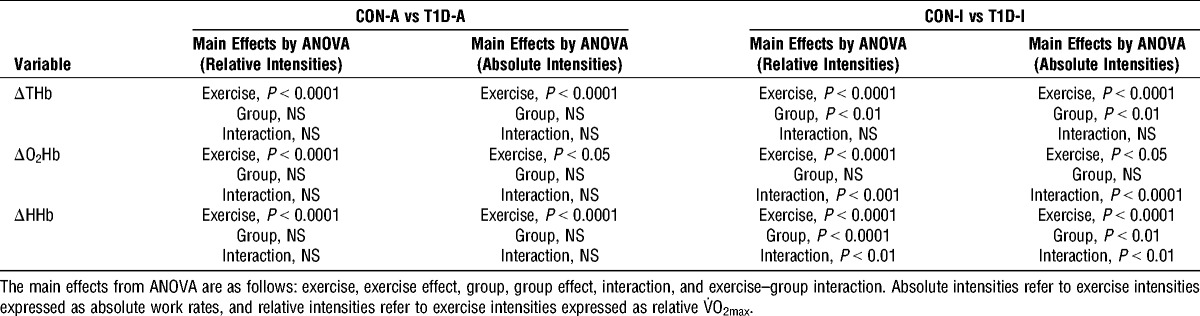

ΔTHb was significantly lower in T1D-I compared with that in CON-I during exercise, whereas no significant difference were observed between T1D-A and CON-A (Fig. 1 and Table 3).

FIGURE 1.

Recordings made by NIRS from the vastus lateralis. Change in ΔTHb (A and B), change in ΔO2Hb (C and D), and change in ΔHHb (E and F). Values are means ± SE. T1D-I, black squares; CON-I, white squares; T1D-A, black triangles; CON-A, white triangles. Post hoc analyses for group effect: significantly different from controls at *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.01. Post hoc analyses for time effect: significantly different from rest at †P <0.05, ††P < 0.01, and †††P < 0.001.

TABLE 3.

Main effects by ANOVA regarding results from NIRS.

ΔO2Hb decreased significantly less with exercise intensity in T1D-I compared with that in CON-I, whereas no intergroup differences were observed between T1D-A and CON-A (Fig. 1 and Table 3).

ΔHHb increased significantly in T1D-I, T1D-A, CON-I, and CON-A throughout the exercise test (Fig. 1 and Table 3). However, the levels of ΔHHb and the increase in ΔHHb were lower in T1D-I compared with those in CON-I (Table 3), particularly at exercise intensities above 60% of V˙O2max (Fig. 1). In contrast, there were no differences in ΔHHb levels and changes between T1D-A and CON-A (Table 3).

Factors able to shift the O2Hb dissociation curve.

HbA1c concentrations were significantly higher in T1D-I compared with those in both CON-I and T1D-A (Table 1).

There were no differences in erythrocyte 2,3-DPG levels and pH during exercise between patients with type 1 diabetes and their respective control groups (Table 2). PaCO2 was higher in T1D-I compared with that in CON-I (Table 2).

In all the previous results sections, we found the same results when females were excluded from statistical analyses. In addition, the use of absolute work rates instead of relative intensity levels for the exercise effect in the mixed models did not change the results’ sense (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

We found that patients with inadequate glycemic control but without any clinically detectable vascular complications displayed impaired aerobic capacity as well as reduction in blood volume and dramatic impairment in HHb increase in active skeletal muscles during intense exercise. However, regardless of their HbA1c levels, patients with type 1 diabetes had adequate CaO2. These results seem all the more relevant, given that this is the first in vivo study to assess all steps from O2 delivery to release in the skeletal muscle during maximal exercise in patients with type 1 diabetes. In addition, the patients were divided into two groups having distinct levels of HbA1c and all were free from clinical micro- and macroangiopathy. Another noteworthy feature of this study lies in the care taken to closely match each patient with a healthy control, taking into account the usual demographic data as well as the exact levels of physical activity (7-d accelerometry) (34). Regular physical activity is one of the major determinants of V˙O2max (21,22) and thus could explain some discrepancies regarding aerobic fitness and type 1 diabetes reported in previous literature.

Aerobic fitness.

Despite being relatively physically active (average of 41.3 ± 23.4 min of moderate to vigorous activities per day), the poorly controlled patients included in our study displayed a level of aerobic fitness (V˙O2max = 34.6 ± 7.2 mL·kg−1·min−1) corresponding to levels usually observed in sedentary subjects (3), suggesting increased risk for cardiovascular diseases (2). In our study, the lower aerobic fitness in poorly controlled patients with type 1 diabetes compared with healthy controls is consistent with several studies in the literature (5,30), in which some patients undoubtedly suffered from micro- and macrovascular complications (30). Thus, besides the indirect effect of HbA1c on aerobic fitness through the presence of chronic hyperglycemia-induced complications, our results raise the possibility of a direct effect of HbA1c levels on V˙O2max. The mechanisms underlying this direct relation may involve muscle O2 delivery (including arterial O2 transport and muscle blood perfusion) and/or O2 release to muscles, which are two main determinants of V˙O2max (6,37).

Arterial O2 transport.

Arterial O2 transport is dependent on two key factors. The first is the ability of the lungs to oxygenate the blood as it passes through the pulmonary capillary network. In the current study, this was reflected by the O2 content of arterialized blood (27). O2 transport also depends on cardiac output, which is determined by the product of stroke volume (as reflected by O2 pulse) and HR. We observed that arterial O2 transport capacity was comparable in poorly controlled patients with type 1 diabetes and their healthy controls. This finding suggests that, in patients with type 1 diabetes but free from clinically detectable microangiopathy, the increase in pulmonary capillary blood flow and alveolar–capillary diffusion induced by high-intensity exercise does not highlight any limitation in lung function. In agreement with our results, Wanke et al. (38) showed that patients with type 1 diabetes, in the absence of overt pulmonary disease, have a normal alveolar–arterial O2 gradient at comparable power outputs.

Blood volume in active skeletal muscles.

Changes in THb are thought to reflect changes in tissue blood volume (19). Therefore, the significant increase in ΔTHb in both groups of healthy controls and of patients with adequate glycemic control in the present study is consistent with the increase in muscle blood volume usually observed with increasing exercise intensity (7). However, in cases of inadequate glycemic control, patients with type 1 diabetes had significantly lower ΔTHb than their healthy controls. Our results supplement those of Pichler et al. (33). In children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes, among whom some were poorly controlled (mean HbA1c, 9.2% ± 1.8%), the authors found lower ΔTHb at the forearm muscle in response to a short submaximal local exercise (1-min rhythmic handgrip) performed in addition to provoked nonphysiological increase in forearm arterial inflow. The latter was artificially set up using brachial venous occlusion (three occlusions of 20 s interspaced by a rest period of 40 s). The current study suggests that, even without a preconditioning stress such as venous occlusion, the physiological condition of maximal exercise was sufficient to induce alteration in muscle perfusion. This alteration is possibly favored by endothelial dysfunction and/or functional alterations of the microcirculation occurring even before overt microvascular complications in cases of chronic hyperglycemia (i.e., high HbA1c levels) and/or in cases of long-term diabetes. The poorly controlled patients, indeed, had longer duration of disease than the well-controlled patients in our study.

The exercise-induced HHb increase in active muscles.

There were no differences in ΔHHb levels and its increase between patients with adequate glycemic control and their healthy controls. These results coincide with those of Peltonen et al. (32), who reported a comparable level of ΔHHb at maximal exercise in patients with type 1 diabetes with an HbA1c of 7.7% ± 0.7% and healthy subjects. We did, however, find that patients with inadequate glycemic control displayed dramatic impairment in exercise-induced ΔHHb increase and reduced ΔHHb levels, especially with intense exercise (>60% V˙O2max).

During a bout of exercise, several factors may explain the reduction in ΔHHb increase. First, a lower ΔHHb may be observed in the case of better matching between muscle O2 delivery (particularly depending on CaO2 and muscle blood perfusion) and muscle O2 use. For example, this scenario is seen at the onset of heavy-intensity exercise in young healthy adults compared with older healthy adults because the former displays better increase in muscle blood volume (as reflected by ΔTHb) for a comparable need for O2 for muscle contraction (13). However, this mechanism does not explain the ΔHHb impairment in our poorly controlled patients with type 1 diabetes, as they otherwise displayed lower ΔTHb rates during the exercise test.

Secondly, the lower ΔHHb may be explained by lower muscle O2 extraction (19). This could occur in two situations, as follows: 1) reduced capacity of O2Hb dissociation, which can occur in pathological circumstances (e.g., CO intoxication) or in sport (e.g., hyperventilation-induced alkalosis in mountaineering), and 2) reduced tissue capacity of O2 use (e.g., mitochondrial dysfunction). The hypothesis of the former situation (i.e., a disturbed O2Hb dissociation rate) is probably involved in the lower exercise level of ΔHHb found in vivo in our poorly controlled (HbA1c, >8%) patients. Indeed, it has been shown in vitro that glycation of hemoglobin, at percentages that might be found in patients with diabetes (i.e., 8% HbA1c), reduced the kinetics of hemoglobin O2 release by 10% in comparison with a 4% HbA1c level (25). In our study, the possibility of higher O2 affinity of HbA1c seems all the more likely, with the consideration that other stimuli, able to shift the O2Hb dissociation curve to the right during intense exercise (Bohr effect) (26), were either comparable (blood pH, erythrocyte 2,3-DPG) or higher (PaCO2) in the poorly controlled patients compared with those in healthy controls.

Thirdly, we cannot exclude the possibility that the exercise-induced switch of muscle blood flow from the “nonnutritive” route (i.e., the flow “reserve” irrigating muscle connective tissues and their associated adipocytes) to the “nutritive” route (i.e., capillaries in intimate contact with the skeletal muscle fibrils) (12) was impaired in our poorly controlled patients with long-standing diabetes, hence reducing overall O2 extraction proportion. This phenomenon has never been investigated in vivo during exercise in humans with type 1 diabetes but can be suggested through previous work on animal models of diabetes (31).

Notwithstanding, the lower HHb increase in the vastus lateralis muscle found in the patients with inadequate glycemic control may contribute to their impaired aerobic fitness because we detected significant positive correlation between V˙O2max and ΔHHb at maximal exercise in all the patients with type 1 diabetes (r = 0.54, P < 0.01).

Further studies are needed to determine whether the blunted HHb increase in muscles observed in patients with poor glycemic control may also be related to impaired muscle mitochondrial function.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the ΔHHb increase in the vastus lateralis during maximal exercise is blunted in patients with type 1 diabetes and with high levels of HbA1c. This result, obtained in vivo during a physiological condition, supports the hypotheses of an increase in O2 affinity induced by hemoglobin glycation and/or of a disturbed balance between nutritive and nonnutritive muscle blood flow routes, as previously put forward by in vitro and animal studies, respectively. This finding is of particular clinical relevance, considering the negative correlation between ΔHHb increase and V˙O2max found in patients with type 1 diabetes in the current study.

Ultimately, from a practical perspective, maximal exercise coupled with NIRS measurement represents a promising noninvasive method of physiologically assessing disorders of muscle perfusion in patients without otherwise clinically detectable microangiopathy. Determining whether these disorders of muscle blood expansion can be reversed with HbA1c improvement will be a challenge for future prospective clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. P. Rasoamanana, F. Dehaut, and A. Watry for laboratory assistance, Pr. A. Duhamel and Dr. H. Béhal for statistical assistance, as well as Dr. K. Volterman and Pr. J. Kerr-Conte for revising the English.

This study was supported by grants from ALFEDIAM-Roche Diagnostics (2009) and from an interregional hospital program of clinical research (PHRC) (2010).

S. T. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. E. L. performed the experiments, contributed to the discussion, and reviewed the manuscript. P. F. contributed to the conception of the experiments, recruited the patients, and reviewed the manuscript. R. M. contributed to the conception of the experiments and reviewed the manuscript. G. M. performed the experiments. J. A. performed the experiments and reviewed the manuscript. A. D. recruited the patients and reviewed the manuscript. A. V. recruited the patients. K. O. performed the experiments. G. B. researched data and reviewed the manuscript. E. H. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. She conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

This study is registered as a clinical trial, NCT02051504, at ClinicalTrial.gov.

The authors have nothing to disclose.

The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by the American College of Sports Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arturson G, Garby L, Robert M, Zaar B. Oxygen affinity of whole blood in vivo and under standard conditions in subjects with diabetes mellitus. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1974; 34 (1): 19– 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aspenes ST, Nilsen TIL, Skaug EA. Peak oxygen uptake and cardiovascular risk factors in 4631 healthy women and men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011; 43 (8): 1465– 73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Astorino TA, White AC, Dalleck LC. Supramaximal testing to confirm attainment of O2max in sedentary men and women. Int J Sports Med. 2009; 30 (4): 279– 84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Astrand PO, Rodahl K, Dahl HA, Stromme SB. Textbook of Work Physiology—4th: Physiological Bases of Exercise. 4th ed Champaign (IL): Human Kinetics; 2003. p. 656. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baldi JC, Cassuto NA, Foxx-Lupo WT, Wheatley CM, Snyder EM. Glycemic status affects cardiopulmonary exercise response in athletes with type I diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010; 42 (8): 1454– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bassett DR, Jr, Howley ET. Limiting factors for maximum oxygen uptake and determinants of endurance performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000; 32 (1): 70– 84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bhambhani YN. Muscle oxygenation trends during dynamic exercise measured by near infrared spectroscopy. Can J Appl Physiol. 2004; 29 (4): 504– 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bodnar PN, Pristupiuk AM. Assessment of the 2,3-diphosphoglycerate content of erythrocytes in diabetes mellitus [in Russian]. Probl Endokrinol (Mosk). 1982; 28 (5): 15– 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brazeau AS, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Strychar I, Mircescu H. Barriers to physical activity among patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008; 31 (11): 2108– 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bunn HF, Briehl RW. The interaction of 2,3-diphosphoglycerate with various human hemoglobins. J Clin Invest. 1970; 49 (6): 1088– 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chance WW, Rhee C, Yilmaz C. Diminished alveolar microvascular reserves in type 2 diabetes reflect systemic microangiopathy. Diabetes Care. 2008; 31 (8): 1596– 601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clark MG, Rattigan S, Clerk LH. Nutritive and non-nutritive blood flow: rest and exercise. Acta Physiol Scand. 2000; 168 (4): 519– 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DeLorey DS, Kowalchuk JM, Paterson DH. Adaptation of pulmonary O2 uptake kinetics and muscle deoxygenation at the onset of heavy-intensity exercise in young and older adults. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2005; 98 (5): 1697– 704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diabetes mellitus. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1985; 727: 1– 113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ditzel J. Affinity hypoxia as a pathogenetic factor of microangiopathy with particular reference to diabetic retinopathy. Acta Endocrinol Suppl (Copenh). 1980; 238: 39– 55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ditzel J, Kjaergaard JJ. Haemoglobin AIc concentrations after initial insulin treatment for newly discovered diabetes. Br Med J. 1978; 1 (6115): 741– 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Esposito F, Mathieu-Costello O, Shabetai R, Wagner PD, Richardson RS. Limited maximal exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure: partitioning the contributors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010; 55 (18): 1945– 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ferrari M, Muthalib M, Quaresima V. The use of near-infrared spectroscopy in understanding skeletal muscle physiology: recent developments. Philos Transact A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2011; 369 (1955): 4577– 90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grassi B, Pogliaghi S, Rampichini S. Muscle oxygenation and pulmonary gas exchange kinetics during cycling exercise on-transitions in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2003; 95 (1): 149– 58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jones MD, Booth J, Taylor JL, Barry BK. Aerobic training increases pain tolerance in healthy individuals. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014; 46 (8): 1640– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Komatsu WR, Barros Neto TL, Chacra AR, Dib SA. Aerobic exercise capacity and pulmonary function in athletes with and without type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010; 33 (12): 2555– 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lakoski SG, Barlow CE, Farrell SW, Berry JD, Morrow JR, Jr, Haskell WL. Impact of body mass index, physical activity, and other clinical factors on cardiorespiratory fitness (from the Cooper Center longitudinal study). Am J Cardiol. 2011; 108 (1): 34– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Laplaud D, Hug F, Grélot L. Reproducibility of eight lower limb muscles activity level in the course of an incremental pedaling exercise. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2006; 16 (2): 158– 66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lukács A, Mayer K, Juhász E, Varga B, Fodor B, Barkai L. Reduced physical fitness in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2012; 13 (5): 432– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marschner JP, Seidlitz T, Rietbrock N. Effect of 2,3-diphosphoglycerate on O2-dissociation kinetics of hemoglobin and glycosylated hemoglobin using the stopped flow technique and an improved in vitro method for hemoglobin glycosylation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994; 32 (3): 116– 21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McDonald MJ, Bleichman M, Bunn HF, Noble RW. Functional properties of the glycosylated minor components of human adult hemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 1979; 254 (3): 702– 7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mollard P, Bourdillon N, Letournel M. Validity of arterialized earlobe blood gases at rest and exercise in normoxia and hypoxia. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010; 172 (3): 179– 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nadeau KJ, Regensteiner JG, Bauer TA. Insulin resistance in adolescents with type 1 diabetes and its relationship to cardiovascular function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010; 95 (2): 513– 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nielsen HB, Madsen P, Svendsen LB, Roach RC, Secher NH. The influence of PaO2, pH and SaO2 on maximal oxygen uptake. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998; 164 (1): 89– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Niranjan V, McBrayer DG, Ramirez LC, Raskin P, Hsia CC. Glycemic control and cardiopulmonary function in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 1997; 103 (6): 504– 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Padilla DJ, McDonough P, Behnke BJ. Effects of Type II diabetes on capillary hemodynamics in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006; 291 (5): H2439– 44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Peltonen JE, Koponen AS, Pullinen K. Alveolar gas exchange and tissue deoxygenation during exercise in type 1 diabetes patients and healthy controls. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2012; 181 (3): 267– 76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pichler G, Urlesberger B, Jirak P. Reduced forearm blood flow in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes (measured by near-infrared spectroscopy). Diabetes Care. 2004; 27 (8): 1942– 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Plasqui G, Westerterp KR. Accelerometry and heart rate as a measure of physical fitness: proof of concept. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005; 37 (5): 872– 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Poortmans JR, Saerens P, Edelman R, Vertongen F, Dorchy H. Influence of the degree of metabolic control on physical fitness in type I diabetic adolescents. Int J Sports Med. 1986; 7 (4): 232– 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Roberts AP, Story CJ, Ryall RG. Erythrocyte 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate concentrations and haemoglobin glycosylation in normoxic type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1984; 26 (5): 389– 91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roca J, Agusti AG, Alonso A. Effects of training on muscle O2 transport at VO2max. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1992; 73 (3): 1067– 76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wanke T, Formanek D, Auinger M, Zwick H, Irsigler K. Pulmonary gas exchange and oxygen uptake during exercise in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 1992; 9 (3): 252– 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wheatley CM, Baldi JC, Cassuto NA, Foxx-Lupo WT, Snyder EM. Glycemic control influences lung membrane diffusion and oxygen saturation in exercise-trained subjects with type 1 diabetes: alveolar-capillary membrane conductance in type 1 diabetes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011; 111 (3): 567– 78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Whipp BJ, Higgenbotham MB, Cobb FC. Estimating exercise stroke volume from asymptotic oxygen pulse in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1996; 81 (6): 2674– 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Womack L, Peters D, Barrett EJ, Kaul S, Price W, Lindner JR. Abnormal skeletal muscle capillary recruitment during exercise in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and microvascular complications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009; 53 (23): 2175– 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]