Abstract

Background

Clean dermatologic procedures create wounds with a low risk of infection (usually up to 5%). Whether the use of topical antibiotics is advocated, with regard to its efficacy and safety issues such as antibiotic resistance and sensitizing potential, is controversial. Fusidic acid, a topical antibiotic against gram-positive bacteria, is a rare sensitizer and commonly used in postprocedure care in Korea.

Objective

This is a retrospective study aimed at comparing the efficacy and safety between fusidic acid and petrolatum for the postprocedure care of clean dermatologic procedures.

Methods

Patients were treated with either fusidic acid or petrolatum ointment, applied on the wound created during clean dermatologic procedures such as biopsy of the punch, incisional, excisional, and shave types. The efficacy, adverse events, and subjective level of satisfaction were retrieved from medical records.

Results

A total of 414 patients with a total of 429 wounds were enrolled. The overall rate of adverse events was 0.9%, and the rates of adverse events in the fusidic acid group and the petrolatum group were 1.4% and 0.5%, respectively (p=0.370). There was no wound discharge, pain, tenderness, swelling, induration, or dehiscence in both groups. The patients' self-assessment of the wound was not significantly different between the two treatment groups.

Conclusion

Our findings support the hypothesis that the routine prophylactic use of topical antibiotics is not indicated for clean dermatologic procedures. We recommend the use of petrolatum in the postoperative care of clean dermatologic procedures because of its equivalent efficacy and superior safety profiles.

Keywords: Dermatologic surgical procedures, Fusidic acid, Infection, Petrolatum, Wound healing

INTRODUCTION

Topical antibiotics have been widely used in dermatologic postprocedural care1. Most dermatologic procedures create clean (class I) wounds, which are defined as the primary closure of wounds on clean, noncontaminated skin under sterile conditions2. The rates of wound infection after clean dermatologic procedures are generally very low, ranging from 0.07% to 4.25%3,4,5,6,7,8. Controversy still exists about whether topical antibiotics have a prophylactic potential in patients undergoing clean dermatologic surgery9. Whereas some studies suggested that topical antibiotics can reduce the risk of infection10,11, other studies showed that prophylactic administration of topical antibiotics does not lower the surgical site infection rates in clean skin surgeries12,13,14. Indiscriminate use of topical antibiotics may contribute to the development of antibiotic resistance within the community and in the treated patients15, and may cause allergic contact dermatitis16,17,18. Thus, the establishment of evidence-based, standard-of-care guidelines for the prophylactic use of topical antibiotics is necessary to avoid potential adverse events and to achieve satisfactory wound healing.

Previous investigations on the prophylactic use of topical antibiotics involved the use of topical antibiotics such as aminoglycosides (neomycin, gentamicin), polypeptides (bacitracin, polymyxin B), mupirocin, and chloramphenicol10,12,13,14,19,20. Fusidic acid (sodium fusidate) is an antibiotic agent derived from the fungus Fusidium coccineum and is widely used in Korea. Although its coverage is limited to gram-positive bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, its allergic potential is less than that of neomycin or bacitracin16,18,21. The objective of this study is to compare the efficacy and safety between fusidic acid and petrolatum in the postprocedure management of clean dermatologic procedures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and methods

This retrospective study was conducted in an outpatient setting at the Department of Dermatology, SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. Between March 2012 and February 2013, all patients presenting with a skin lesion for which clean dermatologic procedures were deemed appropriate were considered eligible for the study. The types of dermatologic procedures included punch biopsy, incisional biopsy, excisional biopsy, and shave biopsy. Surgical procedures involving flaps or grafts were excluded. Each wound was classified into clean, clean-contaminated, contaminated, or infected wound according to the site and status of the wound based on the guideline for surgical wound stratification from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention2. Patients with contaminated or dirty wound, traumatic wound, acute or nonpurulent inflammation, foreign body contamination, systemic infections, and use of systemic antibiotics were excluded, and only those with clean (class I) wound were enrolled in this study. Wounds in the axilla or perineal regions were excluded, and the locations treated were classified into seven regions: face and neck, trunk, buttock, arms, legs, hands, and foot. After the procedures, the patients were instructed to apply either fusidic acid ointment (Parason; SK Chemicals, Seongnam, Korea) or pure petrolatum (Vaseline; Unilever PLC, London, UK), leaving a thin covering over the entire wound area, once or twice a day for 1 to 2 weeks. The fusidic acid ointment contains 2% w/w (20 mg/g) of sodium fusidate as the active ingredient, and also includes cetanol, purified lanolin, concentrated glycerin, liquid paraffin, and white paraffin (petrolatum). Subjects with a known hypersensitivity to topical antibiotics were excluded. All procedures were performed in a sterile manner by using sterile gloves, drapes, and surgical sets. The study was approved by SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 26-2013-90) and conducted according to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Outcome assessments

The efficacy and safety were evaluated by using the retrieved medical records. On 7th or 14th days after the procedure, wounds were evaluated for efficacy including evidence of postprocedural infections and appropriate wound healing, as well as adverse events. More specifically, whereas the efficacy of a given agent was determined by evaluating wound discharge, pain, tenderness, swelling, induration, dehiscence, erythema, and general wound appearance, other application-related issues such as erythema, swelling, vesicle, itching, burning, and development of irritant or allergic contact dermatitis were considered as adverse events. Concurrently, each patient's level of satisfaction with the wound, in terms of healing status, cosmetic acceptability, and overall satisfaction, was evaluated at the clinic by using the following five-point scale: 5=very satisfied, 4=satisfied, 3=neutral/not sure, 2=dissatisfied, 1=very dissatisfied. The patients' underlying medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus, malignancy, immunocompromised status, and other chronic consumptive diseases were also recorded.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted on an intention-to-treat basis by using IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Student's t-test was used to compare continuous or ordinal variables. For categorical data, chi-square or Fisher's exact test was used as appropriate. p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

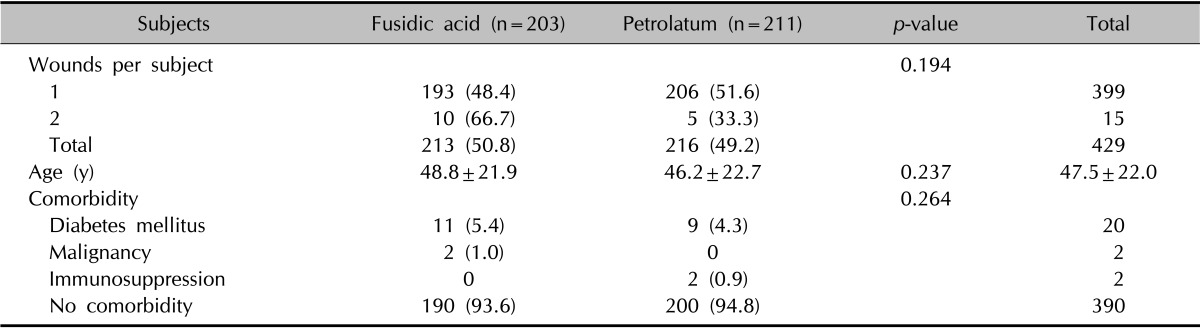

A total of 414 consecutive patients (183 men and 231 women, mean age 47.5±22.0 years; range, 0~95 years) with a total of 429 wounds undergoing clean dermatologic procedures were enrolled in this study. The patients' skin types were either Fitzpatrick skin type III or IV. Fifteen patients had multiple wounds that were allocated to the identical treatment arm and assessed separately (Table 1). Whereas 203 subjects (213 wounds) applied fusidic acid, the remaining 211 subjects (216 wounds) used petrolatum for the postprocedure care. The number of wounds per subject, subject's age, and comorbidities were not significantly different between the two treatment groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of enrolled subjects (n=414)

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±standard deviation.

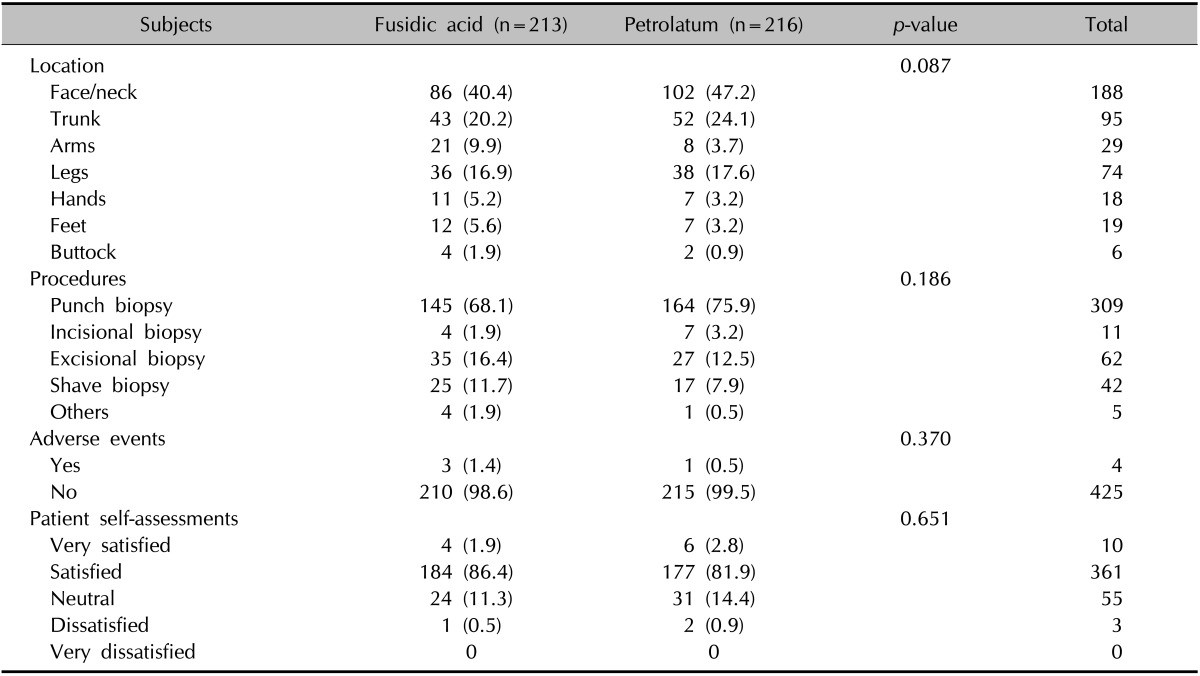

The characteristics and outcomes of wounds are summarized in Table 2. In the fusidic acid and petrolatum groups, skin lesions from the face/neck (40.4% vs. 47.2%), trunk (20.2% vs. 24.1%), and legs (16.9% vs. 17.6%) were common, and the distribution of wound locations were not significantly different. Most wounds were created by punch biopsy (68.1% and 75.9% in the fusidic acid group and the petrolatum group, respectively), followed by excisional biopsy, shave biopsy, and incisional biopsy. The types of procedures were not significantly different between the two groups (p=0.186). The two groups showed a similar distribution of diagnoses: epidermal cyst, seborrheic keratosis, and actinic keratosis (in descending order).

Table 2.

Characteristics and outcomes of wounds (n=429)

Values are presented as number (%).

In terms of efficacy, wounds from both groups underwent a similar wound healing process, and there was no wound discharge, pain, tenderness, swelling, induration, or dehiscence during follow-ups in both groups, indicating comparable efficacy between fusidic acid and petrolatum. The overall number of adverse events was 4 (0.9%), which is consistent with the reported incidence of adverse events associated with clean wounds after dermatologic procedures. The rate of adverse events in the fusidic acid group was 1.4% (three subjects), and that in the petrolatum group was 0.5% (1 subject); however, the difference was not significant (p=0.370). These three subjects treated with fusidic acid showed erythema (two patients) and itching (one patient). On the other hand, one subject treated with petrolatum developed only itching. The patients' self-assessments of wound status were not significantly different between the treatment arms; most were satisfied with their wound (86.4% vs. 81.9%, fusidic acid group vs. petrolatum group). One fusidic acid-treated and one of two petrolatum-treated subjects who reported a dissatisfied rating experienced an itching sensation. The other subject treated with petrolatum complained that the overlying dressing easily fell off after petrolatum application.

DISCUSSION

The current recommendations in wound management emphasize the need for a moist environment to facilitate optimal wound healing22. To this end, various topical emollients containing antibiotics have been used commonly in the belief that they may reduce the risk of infection and help in wound healing23. However, indiscriminate use of topical antibiotics has been associated with the increasing emergence of bacterial resistance15 and the development of allergic contact dermatitis16,17,18. Accordingly, the use of neomycin and bacitracin, common culprits of allergic contact dermatitis, has been discouraged during the last decade.

For the first time in the literature, we report the use of fusidic acid, one of the most commonly used topical antibiotics in Korea and also a rare sensitizer that had exhibited a 0.3% patch test positivity in a contact dermatitis clinic16 as a counterpart to pure petrolatum. Petrolatum, one of the vehicle ingredients of fusidic acid ointment, was used as a control treatment as previously described12,13,14. The rates of adverse events were 1.4% and 0.5% in the fusidic acid group and the petrolatum group, respectively. No significant differences were found in terms of adverse events and patient self-assessments of wound outcomes between the two treatment groups, corroborating previous landmark studies with bacitracin, gentamicin, and mupirocin12,13,14.

Smack et al.14 found no significant difference between postoperative wound infection rates between bacitracin and white petrolatum groups (0.9% and 2.0% in bacitracin and petrolatum group, respectively). Campbell et al.13 also demonstrated no significant differences in infection rate in 147 second-intention wounds after Mohs micrographic auricular surgery between topical gentamicin and white petrolatum; however, gentamicin tended to more frequently produce inflammatory chondritis than petrolatum. Dixon et al.12 compared the efficacy and safety associated with the postoperative use of topical mupirocin, sterile paraffin, and no ointment in 1,801 surgical wounds in 778 patients. There were no significant differences in outcomes for all endpoints, including infection rate, total complication rates, perception of wounds, postoperative pain, degree of inconvenience, and overall level of satisfaction. The mupirocin group showed significantly more cases of skin edge necrosis than the other groups12. Similarly, petrolatum-based ointment resulted in better wound outcomes than did antibiotic-containing treatments24.

Topical antibiotics were the seventh most common source (2.5%) of non-North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) allergens between 2009 and 201017. NACDG antigens such as neomycin and bacitracin still represent the second (8.7%) and fourth (8.3%) most common allergens, respectively, in North America during the same period17. Moreover, almost half of all anaphylactic reactions were attributed to topical antibiotics25. Erythema and pruritus observed in the fusidic acid group may be the symptoms of irritant or allergic contact dermatitis, which warrant further evaluations, including a patch test. Although there were a few case reports on allergic contact dermatitis implicating petrolatum as a cause26,27, the sensitizing risk of petrolatum appears minimal.

Another important concern about the postprocedure use of topical antibiotics is the possibility of an increase of antibiotic-resistant strains such as S. aureus, S. epidermidis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Streptococcus pneumonia, and Propionibacterium acnes in both patients and the community1,20. Recent studies indicate a positive correlation between topical fusidic acid use and the subsequent isolation of fusidic acid-resistant S. aureus28,29,30. For example, in a UK study, a significant association was found between exposure to topical fusidic acid and resistance of an S. aureus isolate to fusidic acid (odds ratio, 2.77; 95% confidence interval, 1.01~7.93)28. The development of resistance to fusidic acid may limit the efficacy of systemic fusidic acid for the treatment of serious staphylococcal infections31. On the other hand, like bacitracin, which eliminated Gram-positive organisms and promoted the growth of Gram-negative bacteria14, fusidic acid has a potential to cause Gram-negative infection that may result in serious complications and treatment challenges.

This study has several limitations. The overall rate of adverse events was 0.9%, and this limited number of patients with adverse events led to underpowering of further analysis. Besides, a patch test was not performed to confirm the relation between fusidic acid and petrolatum concerning the observed adverse events such as erythema and itching sensation.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the routine prophylactic use of topical antibiotics is not indicated for optimal wound healing and reduction of postoperative wound infection. Thus, we recommend the use of petrolatum in the postprocedure care of clean dermatologic procedures because its equivalent efficacy in infection rate and wound healing, excellent safety profiles, and cost-effectiveness.

References

- 1.Del Rosso JQ, Kim GK. Topical antibiotics: therapeutic value or ecologic mischief? Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:398–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garner JS. CDC guideline for prevention of surgical wound infections, 1985. Supersedes guideline for prevention of surgical wound infections published in 1982. (Originally published in November 1985). Revised. Infect Control. 1986;7:193–200. doi: 10.1017/s0195941700064080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dixon AJ, Dixon MP, Askew DA, Wilkinson D. Prospective study of wound infections in dermatologic surgery in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:819–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32167.x. discussion 826-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Futoryan T, Grande D. Postoperative wound infection rates in dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:509–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1995.tb00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook JL, Perone JB. A prospective evaluation of the incidence of complications associated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:143–152. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bencini PL, Galimberti M, Signorini M, Crosti C. Antibiotic prophylaxis of wound infections in skin surgery. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1357–1360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers HD, Desciak EB, Marcus RP, Wang S, MacKay-Wiggan J, Eliezri YD. Prospective study of wound infections in Mohs micrographic surgery using clean surgical technique in the absence of prophylactic antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:842–851. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maragh SL, Brown MD. Prospective evaluation of surgical site infection rate among patients with Mohs micrographic surgery without the use of prophylactic antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:275–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McHugh SM, Collins CJ, Corrigan MA, Hill AD, Humphreys H. The role of topical antibiotics used as prophylaxis in surgical site infection prevention. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:693–701. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heal CF, Buettner PG, Cruickshank R, Graham D, Browning S, Pendergast J, et al. Does single application of topical chloramphenicol to high risk sutured wounds reduce incidence of wound infection after minor surgery? Prospective randomised placebo controlled double blind trial. BMJ. 2009;338:a2812. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dire DJ, Coppola M, Dwyer DA, Lorette JJ, Karr JL. Prospective evaluation of topical antibiotics for preventing infections in uncomplicated soft-tissue wounds repaired in the ED. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:4–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon AJ, Dixon MP, Dixon JB. Randomized clinical trial of the effect of applying ointment to surgical wounds before occlusive dressing. Br J Surg. 2006;93:937–943. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell RM, Perlis CS, Fisher E, Gloster HM., Jr Gentamicin ointment versus petrolatum for management of auricular wounds. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:664–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smack DP, Harrington AC, Dunn C, Howard RS, Szkutnik AJ, Krivda SJ, et al. Infection and allergy incidence in ambulatory surgery patients using white petrolatum vs bacitracin ointment. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;276:972–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Rosso JQ, Leyden JJ. Status report on antibiotic resistance: implications for the dermatologist. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:127–132. v. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gehrig KA, Warshaw EM. Allergic contact dermatitis to topical antibiotics: Epidemiology, responsible allergens, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warshaw EM, Belsito DV, Taylor JS, Sasseville D, DeKoven JG, Zirwas MJ, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2009 to 2010. Dermatitis. 2013;24:50–59. doi: 10.1097/DER.0b013e3182819c51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheth VM, Weitzul S. Postoperative topical antimicrobial use. Dermatitis. 2008;19:181–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor SC, Averyhart AN, Heath CR. Postprocedural woundhealing efficacy following removal of dermatosis papulosa nigra lesions in an African American population: a comparison of a skin protectant ointment and a topical antibiotic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(3 Suppl):S30–S35. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Draelos ZD, Rizer RL, Trookman NS. A comparison of postprocedural wound care treatments: do antibiotic-based ointments improve outcomes? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(3 Suppl):S23–S29. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris SD, Rycroft RJ, White IR, Wakelin SH, McFadden JP. Comparative frequency of patch test reactions to topical antibiotics. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:1047–1051. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eaglstein WH. Moist wound healing with occlusive dressings: a clinical focus. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:175–181. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levender MM, Davis SA, Kwatra SG, Williford PM, Feldman SR. Use of topical antibiotics as prophylaxis in clean dermatologic procedures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trookman NS, Rizer RL, Weber T. Treatment of minor wounds from dermatologic procedures: a comparison of three topical wound care ointments using a laser wound model. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(3 Suppl):S8–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sachs B, Fischer-Barth W, Erdmann S, Merk HF, Seebeck J. Anaphylaxis and toxic epidermal necrolysis or Stevens-Johnson syndrome after nonmucosal topical drug application: fact or fiction? Allergy. 2007;62:877–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tam CC, Elston DM. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by white petrolatum on damaged skin. Dermatitis. 2006;17:201–203. doi: 10.2310/6620.2006.06010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang H, Choi J, Lee AY. Allergic contact dermatitis to white petrolatum. J Dermatol. 2004;31:428–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2004.tb00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mason BW, Howard AJ. Fusidic acid resistance in community isolates of methicillin susceptible Staphylococcus aureus and the use of topical fusidic acid: a retrospective case-control study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2004;23:300–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sule O, Brown NM, Willocks LJ, Day J, Shankar S, Palmer CR, et al. Fusidic acid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (FRSA) carriage in patients with atopic eczema and pattern of prior topical fusidic acid use. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;30:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schöfer H, Simonsen L. Fusidic acid in dermatology: an updated review. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:6–15. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.0833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shah M, Mohanraj M. High levels of fusidic acid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in dermatology patients. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:1018–1020. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]