Abstract

Background

Patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) should be relatively well informed about the disorder to control their condition and prevent flare-ups. Thus far, there is no accurate information about the disease awareness levels and therapeutic behavior of AD patients.

Objective

To collect data on patients' knowledge about AD and their behavior in relation to seeking information about the disease and its treatment.

Methods

We performed a questionnaire survey on the disease awareness and self-management behavior of AD patients. A total of 313 patients and parents of patients with AD who had visited the The Catholic University of Korea, Catholic Medical Center between November 2011 and October 2012 were recruited. We compared the percentage of correct answers from all collected questionnaires according to the demographic and disease characteristics of the patients.

Results

Although dermatologists were the most frequent disease information sources and treatment providers for the AD patients, a significant proportion of participants obtained information from the Internet, which carries a huge amount of false medical information. A considerable number of participants perceived false online information as genuine, especially concerning complementary and alternative medicine treatments of AD, and the adverse effects of steroids. Some questions on AD knowledge had significantly different answers according to sex, marriage status, educational level, type of residence and living area, disease duration, disease severity, and treatment history with dermatologists.

Conclusion

Dermatologists should pay more attention to correcting the common misunderstandings about AD to reduce unnecessary social/economic losses and improve treatment compliance.

Keywords: Awareness, Complementary therapies, Dermatitis, atopic, Disease management, Information seeking behavior

INTRODUCTION

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by periods of exacerbation and remission. As the treatment of AD is based on avoiding exposure to triggering factors and educating the patient about proper skin care, environmental control, and application of topical corticosteroids and emollient, disease control is highly dependent on patients' self-management1.

To control their disease, many AD patients and the parents of patients attempt to seek information on the etiology and treatment of AD2. These days, medical information can be easily accessed online, and false information about AD is prevalent on the Internet and in other media sources2,3,4. Thousands of AD-related sites exist on the Internet; however, 97% of these sites are advertisements for AD-related products, with some containing incorrect or exaggerated information2,5. Moreover, most of the remaining 3% of these AD-related sites are advertisements for oriental medicine clinics or contain information from unknown sources. For example, untested complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies, such as pyroligneous liquor6 and lacquer7 for ingestion or topical application, as well as herbal medicines for improving AD symptoms, are being offered online2,8.

Few studies have focused on the disease awareness and treatment behavior of AD patients worldwide. This study was performed to determine how much correct knowledge AD patients have on AD and to establish an important focus area for the development of educational resources for AD patients. In this study, we investigated the information- and treatment-seeking behavior of AD patients through a survey on their AD knowledge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was based on a questionnaire survey about AD knowledge. A total of seven university-affiliated hospitals (St. Paul's Hospital, St. Mary's Hospital, Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital, St. Vincent's Hospital, Bucheon St. Mary's Hospital, Incheon St. Mary's Hospital, and Seoul St. Mary's Hospital) participated. The study was approved by the institutional review board of each center (IRB No. XC11QIMI0119P), and all the participants gave informed consent. All patients whose AD was diagnosed based on the Hanifin-Rajka criteria9, by dermatologists in the The Catholic University of Korea, Catholic Medical Center between November 2011 and October 2012, were asked to complete the questionnaire. A total of 320 patients and parents of patients were enrolled. The response rate varied from 90% to 100% according to hospital. A total of 313 patients/parents completed the questionnaire without physician assistance. The average age of the patients was 28.5 years (range, 8~70 years).

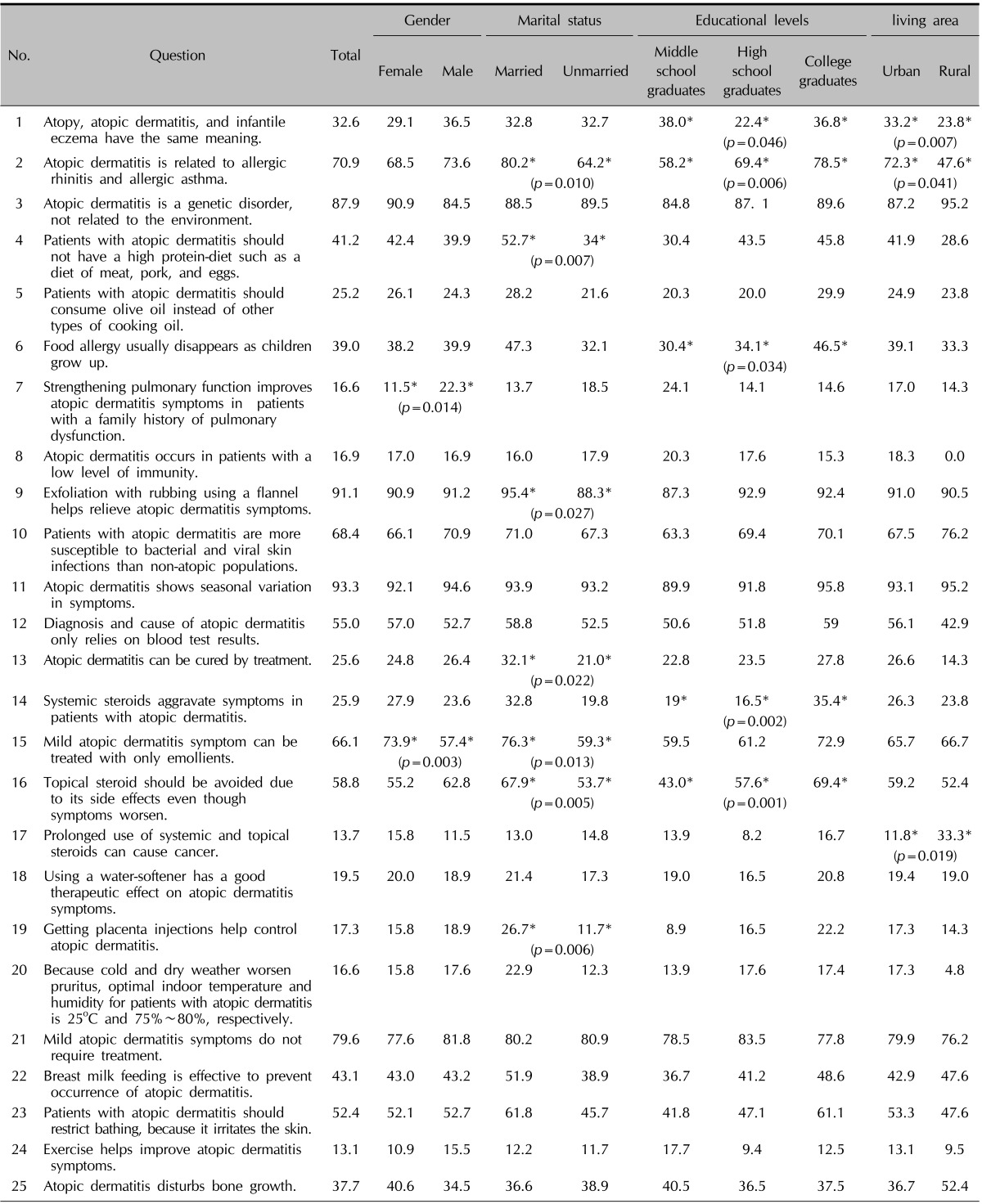

The AD knowledge questionnaire consisted of 25 questions, including 1 question about AD definition, 5 questions about clinical manifestations, 4 about cause or triggering factor, 6 about treatment, 1 about diagnosis, and 8 about skin and environmental care (Table 1). The questionnaires consisted of polar questions about scientifically proven facts; common misunderstandings; and unproven, false, and exaggerated advertisements for commercial purposes.

Table 1.

Percentage of correct answers of all questionnaires according to demographic characteristics

*Chi-squared test, A p-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

We investigated the demographic information of patients, including sex, age, time of onset of AD, disease duration, and the three-item score (TIS) calculated on the day of the survey. All the participants were required to write down their personal information, including educational level, marital status, employment status, area of residence, and self-assessed disease severity at the beginning of the questionnaire. Disease severity was categorized according to the TIS as follows: <3, mild; 3~6, moderate; and ≥6, severe. For the question about sources of AD information, the participants were asked to choose from among general physician, dermatology specialist, oriental medicine clinic, and personal acquaintance, with permission for duplication. For the question about the treatment methods they relied on, the options were treatment methods prescribed by a general physician, a dermatology specialist, or an oriental medicine clinic, or treatment with folk remedies. Treatment given in oriental medicine clinics and folk remedies were considered CAM.

The percentage of correct answers and the AD knowledge scores from all collected questionnaires were compared according to demographic characteristics and disease severity and duration, and whether treatment had been given by specialized dermatologists or not.

For analysis of intergroup comparisons, the chi-square test was used for categorical variables. Student's t-test and one-way analysis of variance were used to compare the mean AD knowledge scores. A p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

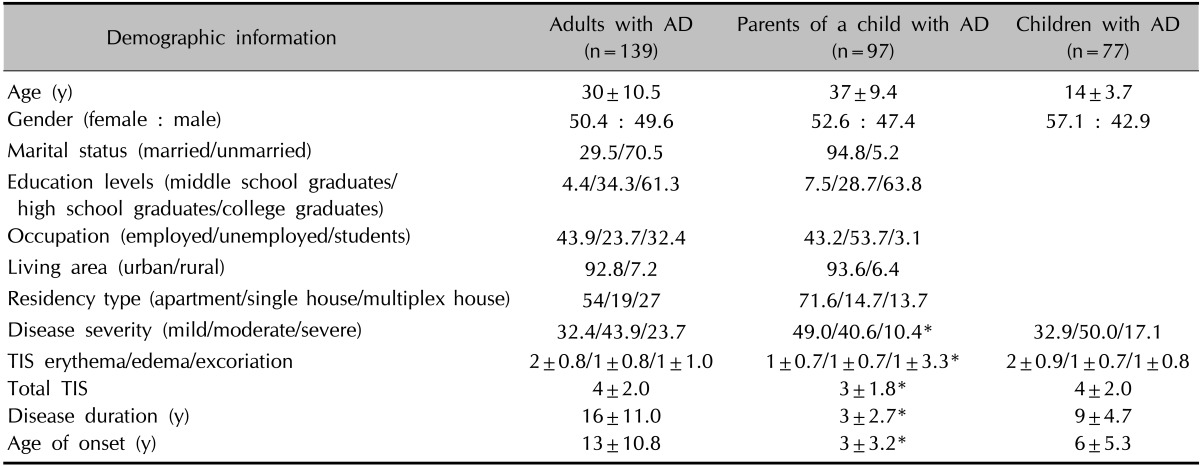

A total of 313 respondents (male, 148; female, 165) completed this questionnaire survey. One hundred thirty-nine adults and 174 children with AD were included in the study. Among the children, 77 patients completed the survey by themselves; for the remaining 97 children, their parents answered the survey. The demographic information of the patients is described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic information of respondents

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or percentage. AD: atopic dermatitis, TIS: three item score. *Information about a child with AD.

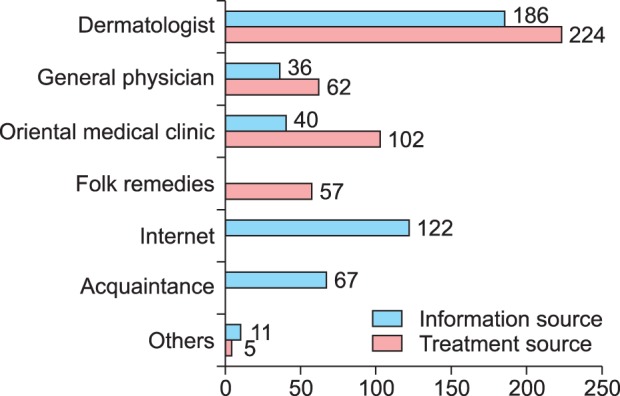

Information and treatment sources of AD patients

Fig. 1 shows the information and treatment sources of the participants. Dermatologists were the most frequent source (59.4%) of AD information. About 40% of the participants relied on information from the Internet. Dermatologists were also the most frequent treatment provider (71.6% of the AD patients). However, >30% of the participants had received treatment in oriental medicine clinics. About one-fifth of our patients had received CAM treatment.

Fig. 1.

The information and treatment sources of the patients and parents with atopic dermatitis.

Top 5 and bottom 5 questions

The top 5 questions that received the highest percentage of correct answers were as follows: question 11, "AD shows seasonal variation in symptoms" (93.3%); question 9, "exfoliation by rubbing with a flannel cloth helps in relieving AD symptoms" (91.1%); question 3, "AD is a genetic disorder, not related to the environment" (87.9%); question 21, "mild AD symptoms do not require treatment" (79.6%); and question 2, "AD is related to allergic rhinitis and allergic asthma" (70.9%).

The questions that received a low percentage of correct answers were as follows: "exercise helps AD symptoms" (13.1%); "prolonged use of systemic and topical steroids can cause cancer" (13.7%); "strengthening the pulmonary function improves AD symptoms in patients with a family history of pulmonary dysfunction" (16.6%); "because cold and dry weather worsens pruritus, the optimal indoor temperature and humidity for patients with AD is 25℃ and 75%~80%, respectively" (16.6%); "AD occurs in patients with a low level of immunity" (16.9%); and "getting placenta injection helps control AD" (17.3%).

Comparison of the AD knowledge of participants according to demographic characteristics

Table 1 shows the percentage of correct answers in the AD knowledge questionnaire according to demographic characteristics. With regard to food restriction, natural course of food allergy, usefulness of emollient and usefulness of bath, the parents of patients showed significantly higher percentage of correct answers than the patients (p=0.015, 0.010, 0.032, and 0.002, respectively).

More males (22.3%) than females (11.5%) (p=0.014) gave correct answers about the therapeutic effect of strengthening the pulmonary function. For the usefulness of emollients in treating mild AD, 73.9% of the females gave the correct answer, which is significantly higher than the proportion of males who answered correctly (57.4%; p=0.003). Married persons had a significantly higher percentage of correct answers to some questions than unmarried persons. Those questions included allergic march, food restriction, harmfulness of exfoliating the skin, potential for treating AD, usefulness of emollients and usefulness of topical steroids, and the effect of placenta injections (p=0.010, 0.007, 0.027, 0.022, 0.013, 0.005, and 0.006, respectively). Several questions had a high level of difficulty depending on education levels. Those questions included AD definition, allergic march, food allergy, beneficial effects of topical and systemic steroids, and adverse effects of topical and systemic steroids (p=0.046, 0.006, 0.034, 0.002, and 0.001, respectively).

A higher percentage of participants living in the city (33.2%) answered correctly about the definition of AD than those living in a rural area (23.8%; p=0.007). Also, more urban residents (72.3%) than rural residents (47.6%; p=0.041) had the correct knowledge about allergic march. However, more urban residents (11.8%) than rural residents (33.3%; p=0.019) gave incorrect answers about the potential carcinogenic effects of systemic and topical steroids.

Apartment residents (37.9%) gave more correct answers than residents living in a single-detached house (28.3%) or a multiplex house (20.3%) concerning the definition of AD (p=0.049).

Several questions showed significant differences in the percentage of correct answers according to disease duration and severity. Patients/parents of patients with chronic AD had a significantly lower percentage of correct answers than patients/parents of patients with acute AD about the usefulness of emollients in treating mild AD (acute: 84.6% vs. chronic: 65.4%) and the lack of usefulness of placenta injections (acute: 34.6% vs. chronic: 15.8%). Similarly, fewer patients with moderate to severe symptoms than those with mild symptoms gave correct answers on the potential for treating AD (mild: 32.5%; moderate: 25%; severe: 11.1%) and the lack of usefulness of placenta injections (mild: 24.4%; moderate: 11.8%; severe: 14.8%).

Participants with higher education levels showed significantly higher mean AD knowledge scores (middle school graduates: 10.13±3.61, high school graduates: 10.49±3.47, and college school graduates: 11.08±3.28; p=0.000). Comparison of AD knowledge scores according to sex, marital status, living area, residency type, and disease severity and duration did not show significant differences.

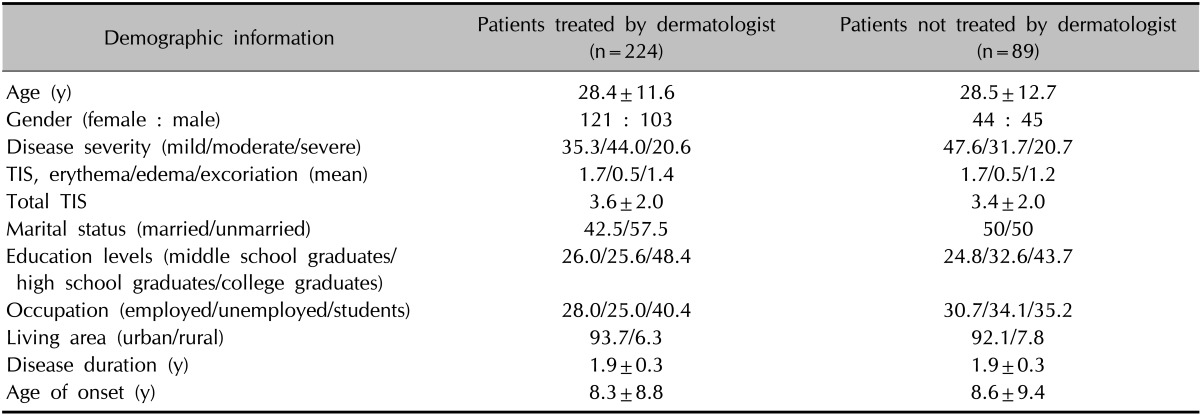

Comparison of AD knowledge of the participants according to treatment history with a dermatologist

A total of 224 patients had received treatment from a dermatologist, whereas 89 had not. The baseline demographic characteristics did not differ between the two groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographic information of patients with atopic dermatitis according to the treatment history by dermatology specialists

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or percentage. TIS: three item score.

Only one question showed a significant difference in the percentage of correct answers between the two groups. In question 3, "AD is a genetic disorder, not related to the environment," patients/parents with a treatment history with dermatology specialists gave the correct answer (91.1%) more often than those without a history of treatment from dermatology specialists (79.8%; p=0.006).

The mean AD knowledge scores were not significantly different between the two groups (treated by a dermatologist: 11.17±3.45; not treated by a dermatologist: 10.83±3.66).

DISCUSSION

The patients' knowledge about their disease could affect their behavior, which, in turn, could decide the outcome of the disease. This study addressed the level of awareness and treatment behavior of AD patients and parents of AD patients. Dermatologists ranked as the most frequent AD information source and the most frequent treatment provider; however, only one question showed a significant difference in the percentage of correct answers between patients who had a treatment history with dermatologists and those who do not. The results suggest that the current AD education being given in outpatient dermatology clinics might be insufficient to change the patients' behavior and that a more comprehensive education is needed. Almost 40% of the participants answered that they obtain information from the Internet. Many of the AD patients reported that they believe the unproven online information to be genuine. False information about CAM and steroid use was found to be widespread among the participants. Education about overall environmental care should be given in detail. Several questions showed a significantly different percentage of correct answers according to demographic characteristics, disease duration and severity, and whether the respondents are patients or parents of patients. Many of the participants expressed lack of knowledge about the standard treatment of AD. More than half of our participants have tried untested CAM to relieve their symptoms.

Nearly 70% of the participants in this study expressed confusion between AD and infantile eczema. Infantile eczema encompasses transient nonspecific skin rashes of infancy, AD, and seborrheic dermatitis, and it should be differentiated from AD. The lack of knowledge among the public about the definition of AD can be abused for commercial purposes, and this results in unnecessary expenditure on skin care, as well as unneeded food restriction and environmental control.

Most of the participants (87.9%) had the correct knowledge that AD results from the interaction between genetic susceptibility and the environment. AD patients are prone to environmental allergens and microbial infections because of decreased skin barrier function9, which was well known among 68.4% of the participants.

The relationship between AD, allergic rhinitis, and asthma was well known among the participants (70.9%). Because about 50%~80% of AD patients develop allergic rhinitis or asthma later in childhood, early management of AD is important9.

About 45% of AD patients/parents think that a diagnosis of AD can be confirmed by means of laboratory testing. For the diagnosis of AD, the presence of pruritus and chronic remitting eczematous dermatitis with a typical morphology and distribution is essential. Laboratory findings such as elevated immunoglobulin E are associated features9.

Many participants had awareness about the therapeutic effect of emollients (66.1%) and the necessity for persistent self-management (79.6%). AD patients need to use emollients appropriately to restore the defective skin barrier and to decrease the frequent use of topical corticosteroids even if they have no evident AD lesion on the skin10. Skin hydration with appropriate baths, which enhance the penetration and efficacy of topical treatment, helps control acute AD flare-ups as long as an emollient is applied after the bath11. However, 47.6% of AD patients/parents think that baths should be restricted. The fact that rubbing irritates AD-affected skin11 was well known to 91.1% of the participants. A recent study revealed that use of ion-exchange water softeners did not have additional benefits for AD patients because they cannot remove chlorine from tap water12. Nevertheless, 81.5% of the respondents in this study believe that water softeners are beneficial.

Children with allergy to pork and chicken meat should consume vegetable protein. About 60% of the participants believe that an extensive elimination diet is needed, which might lead to nutritional deficiencies and growth retardation. A food allergy should be confirmed with a food challenge and an elimination diet13. Although there is no evidence that any particular kind of oil is associated with AD flare-ups, 74.8% of the participants believe that vegetable oil needs to be used. Common food allergies except those resulting from nut products and shellfish tend to disappear as children age13. These facts are poorly recognized only in 39.0% of AD patients/parents.

Seasonal variation of AD symptoms was well known in 93.3% of the participants. Pruritus of AD patients may worsen during winter and pollen seasons. Of the participants, 83.4% did not know the optimal indoor temperature range and humidity for their activities. House dust mites grow well at warm temperatures >25℃ and a humidity of 75%~80%. To avoid exacerbation, the maintenance of an optimal indoor temperature and humidity is important. Although perspiration irritates AD skin, normal activities such as exercise is recommended for children9. Only 13.1% of participants had exact knowledge about exercise.

Steroid phobia could lead to poor compliance with treatment and has an impact on disease outcome. Unfortunately, 41.2% of the participants believe that they should not use topical steroids, although dermatologists consider topical steroids as a mainstay of treatment. Topical corticosteroid phobia was seen in 86.3% of our participants. Concordantly, Aubert-Wastiaux et al.14 reported that topical corticosteroid phobia was present in 80.7% of AD patients/parents regardless of disease severity and duration. Irrational fear of steroids was more frequently seen among urban residents (88.2%) than in others (66.7%). This might be because urban residents are exposed to much more advertisements about AD, some of which may be exaggerated and skewed.

The awareness that AD cannot be cured with occidental medicine and the presence of steroid phobia have led most AD patients to try CAM. More than half of our patients have tried CAM to relieve their symptoms. More than 30% of our participants answered that they had received oriental medicine treatment. A previous report stated that 84% of Korean AD patients have tried CAM, with herbal remedies being the most frequent (73.8%)15. Many oriental medicine clinics insist that strengthening immunity or pulmonary function with herbal remedies, which do not contain steroids, can cure AD. Remarkably, >80% of the participants in this study believed that AD results from a low level of immunity and that strengthening the pulmonary function improves the symptoms. However, the therapeutic effects of herbal remedies prescribed in oriental clinics have been reported in only 25.3% of patients; others experienced no change or even an aggravation of their condition15. The annual per capita operation expense for AD is 2,646,372 won (US $2,600) and a considerable portion of this expense is attributable to CAM. Supposing the gross national product of Korea was US $20,000 in 2010, the estimated per capita nonoperation expense is US $1,500. The annual per capita social loss for AD is an estimated US $4,000, which was calculated by summing the operation and nonoperation expenses16. Untested CAM is sometimes not useful and incurs huge social costs. Patients with more severe symptoms and longer disease duration tend to have more doubts about the curability of AD, and to be more dependent on CAM. The lack of knowledge about these facts may be the cause of the severity and chronicity of their disorder. Education about AD should be started in patients with mild disease to reduce the severity and needless medical costs.

More than 60% of our participants think that AD disturbs bone growth. Although growth impairment may theoretically result from sleep disorders related to pruritus, AD itself or adequate topical corticosteroid use was not found to affect the overall height of children with AD17.

Persistent breastfeeding for at least 4 months decreased the development of AD in infants with a genetic background of atopy18. Surprisingly, less than half of the participants answered this question correctly.

In this study, 70% of the participants had received treatment from a dermatologist. Because all respondents were recruited from general hospitals, selection bias may be present. We tried to establish a validated AD knowledge questionnaire; however, there was some debate about what the right answers are. Because of the lack of questionnaire validation, the usability of the AD knowledge score in this study as a standard measure of AD knowledge is limited.

A well-structured education on AD treatment can help establish a good rapport between physicians and patients and encourage treatment adherence1,19,20,21. Dermatologists should be at the forefront of public education about AD and of the quality control of information available on the Internet and in mass media, to attain better therapeutic results and reduce unnecessary social costs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported in part by the Dermatology Alumni Fund of The Catholic University of Korea made in the 2011 program year.

References

- 1.Cork MJ, Britton J, Butler L, Young S, Murphy R, Keohane SG. Comparison of parent knowledge, therapy utilization and severity of atopic eczema before and after explanation and demonstration of topical therapies by a specialist dermatology nurse. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:582–589. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwon HJ, Kim YJ, Park SB, Yu DS, Kim JW. Study of atopic dermatitis information on the internet in Korea. Korean J Dermatol. 2006;44:137–140. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoo JH, Sohn AR. Evaluation of obesity health information internet sites in Korea. J Korea Sport Res. 2004;15:249–258. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SY. Internet health information. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2002;23:281–290. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim DH, Li K, Seo SJ, Jo SJ, Yim HW, Kim CM, et al. A survey on understanding of atopic dermatitis among Korean patients. Korean J Dermatol. 2012;50:201–211. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keck CM, Anantaworasakul P, Patel M, Okonogi S, Singh KK, Roessner D, et al. A new concept for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: silver-nanolipid complex (sNLC) Int J Pharm. 2014;462:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elias PM. Lipid abnormalities and lipid-based repair strategies in atopic dermatitis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1841:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SY, Lee SD, Kim HO, Park YM. A survey of the awareness, knowledge, and behavior of topical steroid use in dermatologic outpatients of the university hospital. Korean J Dermatol. 2008;46:473–479. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donald L, Lawrence FE, Mark B. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ring J, Alomar A, Bieber T, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, Gelmetti C, et al. European Dermatology Forum (EDF); European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV); European Federation of Allergy (EFA); European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis (ETFAD); European Society of Pediatric Dermatology (ESPD); Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN) Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN). Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1045–1060. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katayama I, Kohno Y, Akiyama K, Ikezawa Z, Kondo N, Tamaki K, et al. Japanese Society of Allergology. Japanese guideline for atopic dermatitis. Allergol Int. 2011;60:205–220. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.11-rai-0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas KS, Dean T, O'Leary C, Sach TH, Koller K, Frost A, et al. SWET Trial Team. A randomised controlled trial of ion-exchange water softeners for the treatment of eczema in children. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forbes LR, Saltzman RW, Spergel JM. Food allergies and atopic dermatitis: differentiating myth from reality. Pediatr Ann. 2009;38:84–90. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20090201-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aubert-Wastiaux H, Moret L, Le Rhun A, Fontenoy AM, Nguyen JM, Leux C, et al. Topical corticosteroid phobia in atopic dermatitis: a study of its nature, origins and frequency. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:808–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chin HW, Jang HS, Jang BS, Jo JH, Kim MB, Oh CK, et al. A study on utilization of alternative medicine for patients with atopic dermatitis. Korean J Dermatol. 2005;43:903–911. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seo SJ. Research of understanding and social loss of atopic dermatitis in Korea. Seoul: Chung-Ang University; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas MW, Panter AT, Morrell DS. Corticosteroids' effect on the height of atopic dermatitis patients: a controlled questionnaire study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:524–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, Chew P, Magula N, DeVine D, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2007;(153):1–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ricci G, Bendandi B, Aiazzi R, Patrizi A, Masi M. Three years of Italian experience of an educational program for parents of young children affected by atopic dermatitis: improving knowledge produces lower anxiety levels in parents of children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong AW, Kim RH, Idriss NZ, Larsen LN, Lio PA. Online video improves clinical outcomes in adults with atopic dermatitis: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:502–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kupfer J, Gieler U, Diepgen TL, Fartasch M, Lob-Corzilius T, Ring J, et al. Structured education program improves the coping with atopic dermatitis in children and their parents-a multicenter, randomized controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]