Abstract

In mice that fail to express the phagolysosomal endonuclease, DNase II, and the type I IFN receptor, excessive accrual of undegraded DNA results in a STING-dependent, TLR-independent inflammatory arthritis. These double knockout (DKO) mice develop additional indications of systemic autoimmunity, including anti-nuclear autoantibodies and splenomegaly, not found in Unc93b1−/− DKO mice and therefore TLR-dependent. The DKO autoantibodies predominantly detect RNA-associated autoantigens, commonly targeted in TLR7-dominated SLE-prone mice. To determine whether an inability of TLR9 to detect endogenous DNA could explain the absence of dsDNA-reactive autoantibodies in DKO mice, we used a novel class of bifunctional autoantibodies, IgM/DNA DVD-Ig™ molecules, to activate B cells through a BCR/TLR9-dependent mechanism. DKO B cells could not respond to the IgM/DNA DVD-Ig™ molecule, despite a normal response to both anti-IgM and CpG ODN 1826. Thus DKO B cells only respond to RNA-associated ligands because DNase II-mediated degradation of self-DNA is required for TLR9 activation.

Introduction

DNase II is a lysosomal endonuclease known to play a critical role in the degradation of the extracellular DNA debris generated by homeostatic erythropoiesis and apoptosis. In mice, DNase II deficiency leads to the overproduction of type I IFN and results in an embryonically lethal anemia (1). DnaseII−/− Ifnar1−/− double knockout (DKO)2 mice that do not express a functional type I IFN receptor survive to adulthood but then develop a form of inflammatory arthritis associated with the production of anti-nuclear antibodies (ANAs) (2). Both embryonic lethality and arthritis appear to depend on cytosolic DNA sensors that converge on the adaptor molecule STING, as STING-deficient DnaseII−/− mice survive to adulthood without evidence of arthritis (3).

We and others have proposed that autoantibody production depends on the adjuvant-like activity of autoantigens (4–6). In the context of SLE and related diseases, detection of endogenous nucleic acid-associated autoantigens by B cell endosomal TLRs is required for the production of ANAs (4, 7–10). However, neither TLR9 or TLR7 is required for the development of arthritis in DKO mice, as mice that fail to express TLR downstream signaling components MyD88 and TRIF still develop arthritis (11). Prior studies have also shown that DKO mice can make anti-DNA autoantibodies (2), and implicated STING in DNA autoantibody production. Nevertheless, our own autoantigen array data has shown that DKO mice make antibodies against an extensive panel of nuclear autoantigens, and that autoantibody production, even in this model, is TLR-dependent (12). The current study was undertaken to gain a better understanding of DKO autoantibody specificities and the role of endosomal and cytosolic nucleic acid sensors in DKO autoantibody production.

Materials and Methods

Mice

RF and Tlr9−/− mice have been described previously (13). DNase II-deficient mice on a C57BL/6 background were kindly provided by Dr. S. Nagata and obtained from the RIKEN Institute. IFNαR1- and Unc93b1-deficient mice were obtained from Jackson Lab. DnaseII+/− IfnarI−/− (Het), DnaseII−/− IfnarI−/− (DKO), and DnaseII−/− IfnarI−/− Unc93b1−/− (TKO), were bred at UMMS. All mice were maintained at the UMMS Department of Animal Medicine in accordance with the regulations of the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

DVD-Ig™ Molecules

The variable heavy (VH) and variable light (VL) regions were PCR-cloned from a hybridoma producing a mouse-anti-DNA mAb using oligo mixtures of NLH5/NLH3 for VH and oligo mixtures of NLK5/NLK3 for VL which are slightly modified primer sets based on Mouse Ig-Primer Set (Novagen, Cat#69831-3). The variable heavy (VH) and variable light (VL) regions from a hybridoma producing a rat anti-mouse IgM mAb (B7-6) (14) were cloned by 5′ RACE. The VH/VL PCR fragments were then subcloned into mammalian expression plasmids containing the human IgG1 constant region sequence, expressed in HEK293-6E cells, purified using standard protein A, and physically (SEC, MS) and functionally characterized along side hybridoma-derived mAbs. The VH and VL sequences of each mAb were then used to design DVD-Ig molecules as described previously (15). The DVD-Ig molecules were synthesized, subcloned into mammalian expression plasmids containing IgG1 constant region, expressed and purified to homogeneity for further characterization.

ANA

HEp-2 human tissue culture substrate slides were incubated with 5 μg/ml of the anti-DNA-IgG2a or the DVD-Ig™ molecule and bound antibodies were detected with Alexa-488-coupled or DyLight 488-coupled detecting reagents.

IgM binding ELISA

Titrations of the DVD-Ig™ proteins (10μg/ml to 0.01μg/ml) were assayed on ELISA plates coated with murine IgM. Bound antibody was detected with biotinylated anti-human IgG and streptavidin-HRP. EC50 were calculated from the titration curve using Prism6.

B cell proliferation

B cells were purified and stimulated as described previously (16) with goat anti-mouse IgM F(ab′)2 (Jackson ImmunoResearch), ODN 1826 (CpG; Idera Pharmaceuticals), anti-DNA-mAb (4) or DVD-Ig proteins (1 ug/ml). Proliferation was assessed by 3H-thymidine (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) incorporation at 24 hr post-stimulation.

FACS

Multicolor flow cytometry analysis was carried out using a BD LSR II with DIVA software (BD Biosciences). Analysis was conducted with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA). Immature B cell were identified with Pacific Blue-B220 and APC-AA4.1 (eBioscience). Mouse erythroid lineage cells were stained with APC-Ter119 (BD Biosciences). Dead cells and debris were excluded by forward- and side-scatter.

Statistical analysis

Experiments are reported as the means ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were made using a Student t test GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software). A p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

Autoantibodies produced by DKO mice primarily detect RNA-associated autoantigens

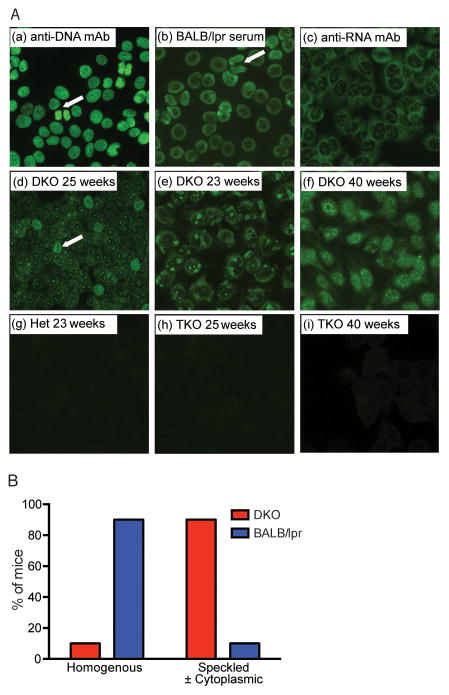

DNA is a highly charged molecule and direct DNA binding assays often detect relatively non-specific interactions. To better characterize the autoantibodies produced by DKO mice, we screened sera by immunofluorescent staining of HEp-2 cells. Considering that the primary defect of DKO mice is an inability to degrade DNA, we anticipated a staining pattern indicative of antibodies reactive with dsDNA or other chromatin components; that is a homogeneous nuclear stain with clear delineation of mitotic plates, as commonly visualized with monoclonal autoantibodies (mAb) reactive with dsDNA, or with sera obtained from autoimmune prone Fas-deficient mice (17)(Fig. 1A-a,b). Antibodies reactive with RNA-associated autoantigens frequently exhibit a more speckled nuclear or cytoplasmic staining pattern, as seen by RNA-reactive mAbs (Fig. 1A-c). We found that the vast majority of DKO sera (20 out of 23) collected between 20–40 weeks of age reacted strongly with HEp2 cells. However, quite unexpectedly, the DKO sera consistently gave speckled nuclear and/or cytoplasmic staining patterns (Fig. 1A-d–f, 1B), and in some cases, the staining pattern showed clear exclusion of the mitotic plate (Fig. 1A-d). By contrast, sera from DnaseII+/− heterozygous Ifnar1−/− (Het) mice were completely ANA negative at early time points (Fig. 1A-g) and only a limited number became very weakly positive at later time points. Anti-nucleolar, and other speckled nuclear patterns, are commonly found in TLR9-deficient or TLR7-overexpressing SLE-prone mice where TLR7, an RNA-specific receptor, plays a prominent role (8, 17, 18). Unc93b1 is a chaperone protein required for the proper function of nucleic acid sensing TLRs (19). As predicted by prior studies (12), sera from DnaseII−/− Ifnar1−/− Unc93b1−/− triple knockout (TKO) mice also failed to stain HEp2 cells (Fig. 1A-h,i). Overall, these results support the notion that autoantibodies produced by DKO mice through a TLR-dependent mechanism predominantly recognize RNA-associated autoantigens, and not dsDNA.

Figure 1. DKO mice make RNA-biased ANAs through a TLR-dependent mechanism.

A. Monoclonal autoantibodies (mAb) reactive with dsDNA (a) or RNA (c) or sera from BALB Fas-deficient (BALB/lpr, b) or RNA (c), DKO (d–f), Het (g), and TKO (h–i) mice were evaluated for ANA staining on HEp-2 coated slides by immunofluorescence. White arrows indicate examples of mitotic plates. (B) ANA staining patterns of serum from BALB/lpr (n=12) and DKO (n=23) mice were classified as nuclear homogenous or nuclear speckled and/or cytoplasmic.

Splenomegaly in DKO mice is TLR-dependent

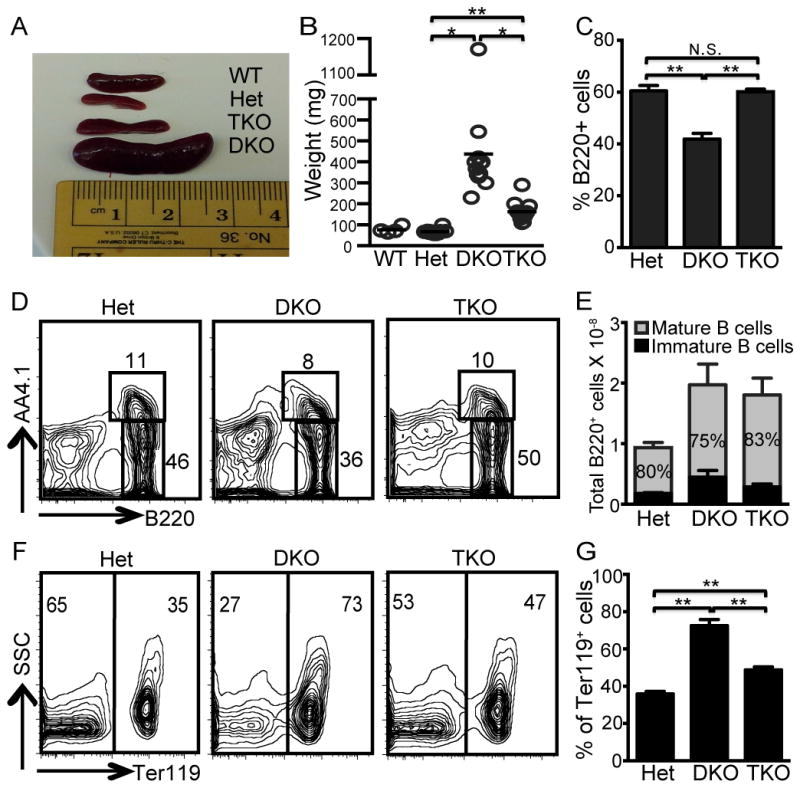

In addition to arthritis and ANA production, autoimmune manifestations of DKO mice include profound splenomegaly, evident at even a very early age. Splenomegaly has been attributed to extramedullary hematopoiesis, resulting from the inability to degrade nuclei extruded from RBC precursors during late stage erythropoiesis and the subsequent blockade of RBC development (2). Although, STING-deficiency does not reduce the extent of splenomegaly (3), quite remarkably Unc93b1−/− TKO spleens were dramatically less enlarged (Fig. 2A, B). To fairly evaluate DKO B cell responses, it was necessary to ensure that both the control and DKO spleens, despite their different sizes, contained comparable B cell populations. To quantify the number of mature B cells, Het, DKO and TKO splenic B cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of B220 and AA4.1. Although the DKO spleens contained a somewhat reduced percentage of B cells compared to the Het and TKO spleens (Fig. 2C), all three strains contained similar ratios of mature to immature B cells (Fig. 2D, E). Moreover, B cells from both the control and DKO mice failed to express B cell activation markers such as CD69 or CD86 (data not shown). Therefore we could detect no unusual features of the B cell compartment of 10 week old DKO mice.

Figure 2. Splenomegaly is TLR-dependent.

(A–B) Spleen weights from DNase Het, DKO and TKO mice were determined at 10 weeks of age. Each dot represents 1 mouse, n=12 for all groups. (C) Percentage of B220+ cells in total spleen cells. (D) Representative FACS plots of spleen cells stained for B220 and AA4.1 and (E) average total number of splenic B cells and % mature B cells (grey portion of the bar and inserted number) n=8 mice for all groups. (F) Representative FACS plots of spleen cells stained for Ter119 vs side scatter (SSC). (G) Percentage of splenic Ter119+ cells in Het, DKO, and TKO mice. n=8 mice. N.S. is not significant, P>0.05; *, P < 0.005; and **, P < 0.00005 by Student’s t-test.

The reduced percentage of B220+ cells in the DKO spleens was at least partly due to the increased frequency of erythroid lineage cells, as indicated by the pan-erythroid lineage marker Ter119+ (Fig. 2F, G), a feature of extramedullary hematopoiesis (20). In line with the reduced spleen weight, the frequency of Ter119+ cells was also significantly reduced in the TKO spleens (Fig. 2F, G). These observations indicate that the DKO splenic phenotype does not simply result from compromised bone marrow erythropoiesis resulting from the inability of DNase II-deficient macrophages to degrade extruded erythroblast nuclei. Rather, pathways dependent on Unc93 promote both splenomegaly and extramedullary hematopoiesis.

IgM/DNA DVD-Ig™ molecules stimulate polyclonal B cell populations through a TLR9 dependent mechanism

The clearance of extruded RBC nuclei and apoptotic debris most likely leads to the initial accumulation of nucleic acids in phagocytic compartments associated with DNA- and RNA-reactive endosomal TLRs. Therefore it was not surprising to find evidence of endosomal TLR activation. However, the RNA-autoantigen bias observed in a model of systemic autoimmunity triggered by excessive DNA accrual was perplexing. The absence of dsDNA-reactive antibodies pointed to a defect in TLR9 activity. We had previously documented a role for TLR detection of endogenous ligands in B cells expressing a transgene-encoded low affinity BCR specific for autologous IgG2a. These rheumatoid factor (RF) B cells can be activated by IgG2a DNA-reactive monoclonal autoantibodies, through a mechanism that is DNase I-sensitive and entirely TLR9-dependent (4). The DNA-reactive autoantibodies spontaneously bind DNA-associated cell debris, released from damaged or dying cells, and facilitate delivery of the endogenous ligand to a TLR9+ endosomal compartment. While these RF B cells have provided an extremely useful experimental model, their application is limited to cells expressing the correct BCR transgene, requiring extensive intercrossing to evaluate multi-gene genetically targeted mice (16).

To expedite these analyses, we developed bifunctional immunoglobulins that incorporate both DNA and IgM binding domains, and thereby direct a DNA-reactive autoantibody (and bound autoantigen), to all IgM expressing B cells. These, DVD-Ig™ molecules, consist of conventional heavy and light chains that incorporate two distinct VL and VH domains, fused in tandem by a short linker (21)(Fig 3A). DVD-Ig molecules can be constructed with either one of the binding domains at the N-terminus, and with linkers of distinct lengths between the two domains. The orientation and linker combination that allows for the optimal binding activity of both V domains can vary, depending on V domain combinations. To identify a DVD-Ig™ molecule that expressed both IgM and DNA reactivity, 8 different DVD-Ig molecules with either the IgM or the DNA V domain at the N-terminus, connected with 5 different linkers, were evaluated for their capacity to bind IgM as determined by a direct binding ELISA, and to bind DNA as determined by an immunofluorescent HEp-2 staining assay. In general DVD-Ig™ molecules with an N-terminal anti-IgM domain bound IgM with higher affinity, although internal anti-IgM domains were also functional (Fig 3B). By contrast, only the DVD-Ig™ molecules with an N-terminal anti-DNA domain were positive by ANA, and the intensity of staining varied within this group based on the linker between the V1 and V2 domains (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. DVD-Ig™ molecules bind both IgM and DNA and induce non-Tg B cells to proliferate through a TLR9-dependent mechanism.

(A) Schematic diagram of bifunctional DVD-Ig™ molecules. (B) IgM-binding ELISA of representative DVD-Ig™ molecules, with anti-IgM domain as V1 (DVD3756, blue), or with the anti-IgM domain as V2 (DVD3751, red; DVD3754, green), compared to the original anti-IgM antibody. (C) ANA staining patterns of the original anti-DNA mAb compared to the DVD-Ig molecules depicted in B. (D) Composite plot of EC50 and ANA score with capacity of each DVD-Ig molecule to activate B cells, as determined by 3H-thymidine incorporation, indicated by the size of the circle; (proliferation index, large circle >20-fold; medium circle 10–20 fold; small circle <10-fold). The color of the circle corresponds to the DVD-Ig molecules depicted in B and C, additional DVD-Ig molecules depicted as open black circles, and original mAbs indicated by filled black circles. (E) WT or Tlr9−/− B cells were stimulated with the DVD3754 or anti-DNA mAb for 24hr and compared to medium control. Proliferation was assessed by 3H-thymidine incorporation. The data represent the average of 3 separate experiments +/− the SEM.

One particular DVD-Ig™ molecule, 3754, with a high ANA score and intermediate IgM binding affinity, stimulated BALB/c B cells more strongly than the rest, as determined by 3H-thymidine incorporation (Fig. 3D). DVD3754 and the original IgG2a anti-DNA mAb were then evaluated for their capacity to activate Tlr9+/+ and Tlr9−/− RF Tg and non-Tg B cells (Fig. 3E). As shown previously, the anti-DNA mAb only activated the Tlr9+/+ RF B cells. By contrast, DVD3754 induced a comparable level of proliferation in both Tlr9+/+ RF and Tlr9+/+ non-Tg BALB/c B cells, but not Tlr9−/− RF or Tlr9−/− BALB/c B cells (Fig 3E). Therefore, DVD3754 activation of polyclonal B cells recapitulated the mechanism through which anti-DNA IgG2a mAbs activate RF B cells, and could be used to interrogate the response of DKO B cells to a physiologically relevant form of DNA.

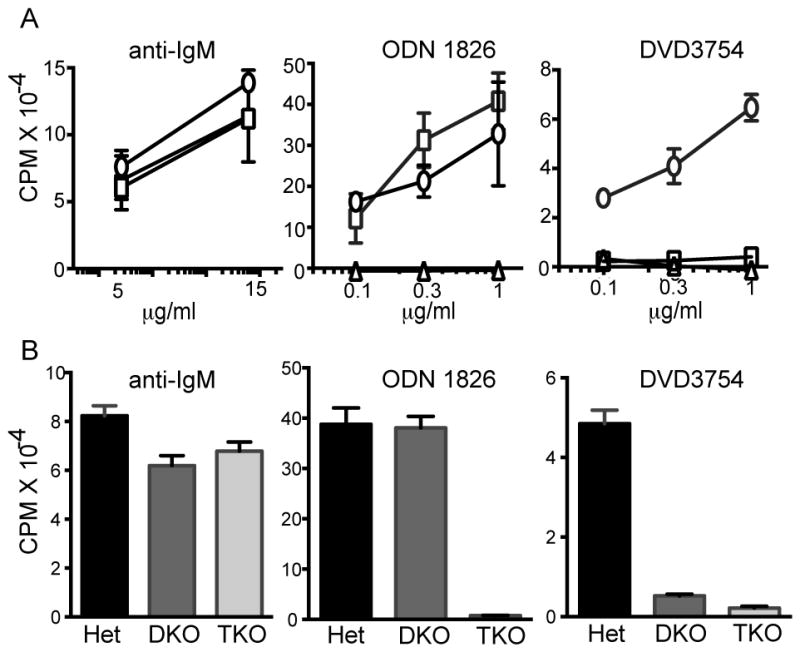

DVD3754 IC activation of B cells requires DNase II

B cells obtained from 10 wk old DnaseII+/− Ifnar−/− (Het), DKO, and DnaseII−/− Ifnar−/− Unc93b1−/− triple knockout (TKO) B cells, were stimulated with anti-IgM F(ab′)2, the small molecule TLR9 ligand ODN 1826 and DVD3754 (Fig. 4A, B). As expected, B cells from all 3 strains responded comparably to anti-IgM, and the TKO B cells did not respond to either ODN 1826 or DVD3754. However, the DKO B cells completely failed to respond to DVD3754 (Fig. 4A, B), despite a normal response to ODN 1826. DNase II has previously been shown to play a critical role in engulfment-mediated DNA degradation (22), while in C. elegans, effective degradation of cell corpses requires expression of a DNase II homologue in both the original apoptotic cell, and in the phagocytic cell that engulfs the cell corpse (23). Presumably, TLR9 is available and functional in the DKO B cells because they still respond to ODN 1826, which does not require degradation. However, the inability of DKO B cells to respond to DVD3754 points to a B cell intrinsic role for DNase II in the degradation and therefore detection of endogenous DNA fragments delivered through the BCR, thereby explaining the absence of dsDNA-reactive autoantibodies.

Figure 4. B cell response to DNA ICs requires DNase II.

(A–B) B cells from Het (circle), DKO (square), and TKO (triangle) mice were stimulated with anti-IgM, ODN 1826 or DVD3754 for 24 hr and proliferation was determined by 3H-thymidine incorporation. Results in (A) are representative of 3 independent experiments and (B) are average of separate experiments include 8 mice/group and are summarized as CPM +/− SEM.

The question is why DKO mice make autoantibodies directed against RNA-associated antigens. We propose that the excessive accumulation of undegraded DNA interferes with the capacity of macrophages or other phagocytic cells to appropriately clear cell debris containing both RNA- as well, as DNA-associated autoantigens, thereby triggering the production of autoantibodies through a mechanism dependent on RNA-reactive TLRs. Notably, in the context of the inflammatory environment resulting from DNase II deficiency, ANA production must be independent of type I IFN, because the DKO mice do not express the type I IFN receptor.

Although TLR9 is required for the production of anti-dsDNA antibodies in autoimmune-prone mice, SLE-prone Tlr9−/− mice invariably develop more severe clinical disease than their TLR9-sufficient littermates (8, 10, 24). It has been proposed that TLR9 is required for the production of protective antibodies that are important in the clearance of apoptotic or other forms of cell debris that serve as the trigger for systemic autoimmunity (25). Alternatively, TLR7-driven B cell responses are inherently limited by the co-expression of TLR9, and autoantibodies directed at RNA-associated autoantigens are simply more pathogenic due to distinct activation pathways, or unique properties of antibodies directed to the RNA associated autoantigens. The inability of DKO mice to respond to endogenous TLR9 ligands adds this model to the list of predominantly RNA-driven TLR-dependent systemic autoimmune diseases. While we assume that the relevant TLR is TLR7, formal proof will require intercrossing of the DKO TLR7-deficient strains. Overall the data suggest that there are two overlapping disease processes taking place in DKO mice, an inflammatory arthritis driven by a STING dependent pathway, and an SLE-like syndrome, associated with autoantibody production, splenomegaly, and extramedullary hematopoiesis, driven by a TLR7-dependent or potentially TLR8-dependent, pathway. Additional studies will be needed to determine whether the same, or distinct cell types, promote arthritis and other aspects of systemic autoimmunity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. S. Nagata for kindly providing the DNase II-deficient mice, and Tara Robidoux for exceptional technical assistance.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: ANA, anti-nuclear antibody; DVD-Ig™, Dual variable domain immunoglobulin; DKO, DnaseII−/−Ifnar1−/− double knockout; Het, DnaseII+/−Ifnar1−/−; TKO, DnaseII−/−Ifnar1−/−Unc93b1−/− triple knockout; RF, rheumatoid factor.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Yoshida H, Okabe Y, Kawane K, Fukuyama H, Nagata S. Lethal anemia caused by interferon-beta produced in mouse embryos carrying undigested DNA. Nature immunology. 2005;6:49–56. doi: 10.1038/ni1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawane K, Ohtani M, Miwa K, Kizawa T, Kanbara Y, Yoshioka Y, Yoshikawa H, Nagata S. Chronic polyarthritis caused by mammalian DNA that escapes from degradation in macrophages. Nature. 2006;443:998–1002. doi: 10.1038/nature05245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn J, Gutman D, Saijo S, Barber GN. STING manifests self DNA-dependent inflammatory disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:19386–19391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215006109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leadbetter EA, Rifkin IR, Hohlbaum AM, Beaudette BC, Shlomchik MJ, Marshak-Rothstein A. Chromatin-IgG complexes activate B cells by dual engagement of IgM and Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2002;416:603–607. doi: 10.1038/416603a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plotz PH. The autoantibody repertoire: searching for order. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:73–78. doi: 10.1038/nri976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busconi L, Lau CM, Tabor AS, Uccellini MB, Ruhe Z, Akira S, Viglianti GA, Rifkin IR, Marshak-Rothstein A. DNA and RNA autoantigens as autoadjuvants. J Endotoxin Res. 2006;12:379–384. doi: 10.1179/096805106X118816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau CM, Broughton C, Tabor AS, Akira S, Flavell RA, Mamula MJ, Christensen SR, Shlomchik MJ, Viglianti GA, Rifkin IR, Marshak-Rothstein A. RNA-associated autoantigens activate B cells by combined B cell antigen receptor/Toll-like receptor 7 engagement. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1171–1177. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christensen SR, Shupe J, Nickerson K, Kashgarian M, Flavell RA, Shlomchik MJ. Toll-like receptor 7 and TLR9 dictate autoantibody specificity and have opposing inflammatory and regulatory roles in a murine model of lupus. Immunity. 2006;25:417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kono DH, Haraldsson MK, Lawson BR, Pollard KM, Koh YT, Du X, Arnold CN, Baccala R, Silverman GJ, Beutler BA, Theofilopoulos AN. Endosomal TLR signaling is required for anti-nucleic acid and rheumatoid factor autoantibodies in lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12061–12066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905441106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson SW, Scharping NE, Kolhatkar NS, Khim S, Schwartz MA, Li QZ, Hudkins KL, Alpers CE, Liggitt D, Rawlings DJ. Opposing Impact of B Cell-Intrinsic TLR7 and TLR9 Signals on Autoantibody Repertoire and Systemic Inflammation. J Immunol. 2014;192:4525–4532. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawane K, Tanaka H, Kitahara Y, Shimaoka S, Nagata S. Cytokine-dependent but acquired immunity-independent arthritis caused by DNA escaped from degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:19432–19437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010603107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baum R, Sharma S, Carpenter S, Li Q-Z, Busto P, Fitzgerald KA, Marshak-Rothstein A, Gravallese E. Cutting Edge: AIM2 and endosomal TLRs differentially regulate arthritis and autoantibody production in DNase II–deficient mice. J Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402573. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uccellini MB, Busconi L, Green NM, Busto P, Christensen SR, Shlomchik MJ, Marshak-Rothstein A, Viglianti GA. Autoreactive B cells discriminate CpG-rich and CpG-poor DNA and this response is modulated by IFN-alpha. J Immunol. 2008;181:5875–5884. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Julius MH, Heusser CH, Hartmann KU. Induction of resting B cells to DNA synthesis by soluble monoclonal anti-immunoglobulin. Eur J Immunol. 1984;14:753–757. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830140816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu C, Ying H, Bose S, Miller R, Medina L, Santora L, Ghayur T. Molecular construction and optimization of anti-human IL-1alpha/beta dual variable domain immunoglobulin (DVD-Ig) molecules. mAbs. 2009;1:339–347. doi: 10.4161/mabs.1.4.8755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nundel K, Busto P, Debatis M, Marshak-Rothstein A. The role of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in the development and BCR/TLR-dependent activation of AM14 rheumatoid factor B cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:865–875. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0313126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christensen SR, Kashgarian M, Alexopoulou L, Flavell RA, Akira S, Shlomchik MJ. Toll-like receptor 9 controls anti-DNA autoantibody production in murine lupus. J Exp Med. 2005;202:321–331. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolland S, Yim YS, Tus K, Wakeland EK, Ravetch JV. Genetic modifiers of systemic lupus erythematosus in FcgammaRIIB(−/−) mice. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1167–1174. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tabeta K, Hoebe K, Janssen EM, Du X, Georgel P, Crozat K, Mudd S, Mann N, Sovath S, Goode J, Shamel L, Herskovits AA, Portnoy DA, Cooke M, Tarantino LM, Wiltshire T, Steinberg BE, Grinstein S, Beutler B. The Unc93b1 mutation 3d disrupts exogenous antigen presentation and signaling via Toll-like receptors 3, 7 and 9. Nature immunology. 2006;7:156–164. doi: 10.1038/ni1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kina T, Ikuta K, Takayama E, Wada K, Majumdar AS, Weissman IL, Katsura Y. The monoclonal antibody TER-119 recognizes a molecule associated with glycophorin A and specifically marks the late stages of murine erythroid lineage. British journal of haematology. 2000;109:280–287. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu C, Ying H, Grinnell C, Bryant S, Miller R, Clabbers A, Bose S, McCarthy D, Zhu RR, Santora L, Davis-Taber R, Kunes Y, Fung E, Schwartz A, Sakorafas P, Gu J, Tarcsa E, Murtaza A, Ghayur T. Simultaneous targeting of multiple disease mediators by a dual-variable-domain immunoglobulin. Nature biotechnology. 2007;25:1290–1297. doi: 10.1038/nbt1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawane K, Fukuyama H, Kondoh G, Takeda J, Ohsawa Y, Uchiyama Y, Nagata S. Requirement of DNase II for definitive erythropoiesis in the mouse fetal liver. Science. 2001;292:1546–1549. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5521.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans CJ, Aguilera RJ. DNase II: genes, enzymes and function. Gene. 2003;322:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu P, Wellmann U, Kunder S, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Jennen L, Dear N, Amann K, Bauer S, Winkler TH, Wagner H. Toll-like receptor 9-independent aggravation of glomerulonephritis in a novel model of SLE. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1211–1219. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoehr AD, Schoen CT, Mertes MM, Eiglmeier S, Holecska V, Lorenz AK, Schommartz T, Schoen AL, Hess C, Winkler A, Wardemann H, Ehlers M. TLR9 in peritoneal B-1b cells is essential for production of protective self-reactive IgM to control Th17 cells and severe autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2011;187:2953–2965. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]