Abstract

Background

NHL (non-Hodgkin lymphoma) consists of over 60 subtypes, ranging from slow-growing to very aggressive. The three largest subtypes are DLBCL (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), FL (follicular lymphoma), and CLL/SLL (chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma). For each subtype, different racial groups have different presentations, etiologies, and prognosis patterns.

Methods

SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) data on DLBCL, FL, and CLL/SLL patients diagnosed between 1992 and 2010 were analyzed. Racial groups studied included NHW (non-Hispanic whites), HW (Hispanic whites), blacks, and API (Asians and Pacific Islanders). Patient characteristics, age-adjusted incidence rate, and survival were compared across races. Stratification and multivariate analysis were conducted.

Results

There are significant racial differences for patients’ characteristics, including gender, age at diagnosis, stage, lymph site, and age, and the patterns vary across subtypes. NHWs have the highest incidence rates for all three subtypes, followed by HWs (DLBCL and FL) and blacks (CLL/SLL). The dependence of the incidence rate on age and gender varies across subtypes. For all three subtypes, NHWs have the highest five-year relative survival rates, followed by HWs. When stratified by stage, racial difference is significant in multiple multivariate Cox regression analyses.

Conclusions

Racial differences exist among DLBCL, FL, and CLL/SLL patients in the U.S. in terms of characteristics, incidence, and survival. The patterns vary across subtypes. More data collection and analysis are needed to more comprehensively describe and interpret the across-race and subtype differences.

Keywords: non-Hodgkin lymphoma, racial differences, subtype, SEER

1. Introduction

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative malignancies. In recent years, the incidence rate of NHL in American men and women has been the highest in the world [1]. It is the fifth-most-common cancer in both men and women in the U.S., with an estimated 70,800 new cases and 18,990 deaths in 2014 [2]. NHL has over 60 subtypes. DLBCL (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), the most common subtype, is an aggressive cancer of the B cells and comprises approximately 30% of all cases. FL (follicular lymphoma), the second-most-common subtype, is generally indolent. It is a lymphoma of the follicle center B cells, which has at least a partially follicular pattern. CLL (chronic lymphocytic leukemia) is a stage of SLL (small lymphocytic lymphoma), a type of B-cell lymphoma. They are considered to be the same underlying disease with different appearances. They were merged into an aggregate category by the 2001 WHO (World Health Organization) classification scheme and are the third-most-common subtype of NHL. There are also a large number of smaller subtypes [3]. Some studies have analyzed NHL overall, while with the significant heterogeneity across subtypes, others have conducted subtype-specific analyses. For NHL overall and the multiple subtypes, race has been identified as an important risk factor in multiple aspects [4,5].

The goal of this study is to systematically describe the racial differences for DLBCL, FL, and CLL/SLL patients in the U.S. Those are the three largest subtypes and are all B-cell lymphomas, which account for about 85% of NHL [6]. Racial differences have been studied for multiple cancer types, including NHL overall and individual subtypes [7,8,9,10,11]. However, the existing studies may be limited by focusing on a specific subtype (for example, some studies [8] focus on DLBCL only), a narrow spectrum of racial groups (for example, Koshiol et al. [12] only compared whites and blacks), or specific outcomes (for example, treatment and survival [8]). In this study, we conducted a unified analysis of racial differences for the three largest NHL subtypes using the SEER database and applying the same analysis approach. The analysis results were expected to be more comparable across subtypes than those in the literature, which are based on different databases using different analysis methods. They can reveal the similarity or dissimilarity in racial difference patterns across subtypes. In addition, for each subtype, this study aims to be more comprehensive by comparing a wider spectrum of racial groups, including NHW (non-Hispanic whites), HW (Hispanic whites), blacks, and API (Asians and Pacific Islanders), and by analyzing multiple aspects, including patients’ characteristics, clinical-pathological features, incidence rate, and survival rates. Analyzing and comparing multiple cancer types and subtypes can provide critical clues for future epidemiological investigation and more insights than single-(sub)type analysis [13,14].

2. Methods

2.1 Source Population

The population-based sample was obtained from the SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results, http://seer.cancer.gov/) database. The SEER 9, 13, and 18 registries were analyzed in this study and cover approximately 9.5%, 14%, and 28% of the U.S. population, respectively. For each case, the first matching record was selected for analysis. Patients with DLBCL, FL, and CLL/SLL were identified and categorized using ICD-O-3 (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition). Specifically, DLBCL patients were classified as four histology types with corresponding codes: DLBCL, NOS except site C49.9 (9680, 9688, 9737-9738, 9684), intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with site C49.9 (9680, 9688, 9737-9738, 9712), primary effusion lymphoma (9678), and mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (9679). FL patients had histology codes 9690-9691, 9695, and 9698. And CLL/SLL patients had histology codes 9670 and 9823.

Different SEER registry groupings were used to maximize sample size. For the analysis of patients’ characteristics and clinical-pathological features, SEER 9 contains data on cancers diagnosed between 1973 and 2010, as well as information on gender, age at diagnosis, age group (0-39 years, 40-64 years, 65-84 years, 85 years), survival time, stage (I-IV), and lymph node site (nodal, extranodal). For the analysis of incidence rate, SEER 13 data contains detailed race and incidence information for cancers diagnosed between 1992 and 2010. For the analysis of survival rate, SEER 18 data contains information for cancers diagnosed between 1973 and 2005 and followed up to December 31, 2010.

The definitions of NHL subtypes have been evolving. In addition, more effective treatments have been developed and have had a significant impact on survival rates. With such considerations, we limited our analysis to cancers diagnosed after 1992 [15]. In addition, we also conducted additional survival analysis on cancers diagnosed after 1999 to better accommodate the more recent treatment regimens.

2.2 Statistical Analysis

Data on each subtype were analyzed separately. In the analysis of patients’ characteristics and clinical-pathological features, Chi-squared tests and ANOVA were used to compare across racial groups. The analysis was conducted using SAS version 9.3. Age-adjusted incidence rates were computed using SEER*Stat, and United States Census data from 2000 were used for age-standardization. Incidence rates were also computed for specific age and gender groups. Five-year relative survival rates were calculated using SEER*Stat and an actuarial method [16]. Multivariate Cox regression analyses were conducted on racial differences in survival rates, stratified by stage at diagnosis. Confounders (including age at diagnosis, gender, and extranodal involvement) were accounted for.

Similar to other large databases, SEER has missing measurements. Some analyzed variables, such as race, do not have any missingness. Other variables in general have a low missing rate. For example, for stage, the missing rates are 4.25% (DLBCL), 4.44% (FL), and 2.43% (CLL/SLL). A literature search did not suggest missingness to be race-related. With the low missing rate, we simply removed missing records from the analysis.

SEER also contains data on multiple other subtypes. In principle, more subtypes can be analyzed using the same approach. However, for subtypes other than the three analyzed, sample sizes (especially for the small racial groups) are small. This creates a problem, particularly in stratified analysis. To ensure the overall reliability of the analysis, we focused on the three largest subtypes.

3. Results

3.1 Patients’ Characteristics and Clinical-Pathological Features

Results are presented in Table 1. Only DLBCL had a significant racial difference in gender distribution (p<0.0001), with blacks having the highest percentage of males (58.31%) and APIs having the lowest (52.92%). All three subtypes exhibit significant racial differences in the distribution of age at diagnosis. The pattern is consistent across subtypes, with NHWs having the highest age at diagnosis, followed by APIs and then HWs. Overall, CLL/SLLs have a higher age at diagnosis. For all three subtypes, the age distribution is significantly different across races. For DLBCL, NHWs tended to be older than the other races. For FL, NHWs and APIs were older than HWs and blacks. This is also true for CLL/SLL. For all three subtypes, the distributions of stage are significantly different across races. CLL/SLLs were diagnosed at higher stages than DLBCL and FL. Extranodal involvement is significantly different across races for DLBCL and CLL/SLL but not FL. For DLBCL, blacks have the highest rate of extranodal involvement (70.52%), whereas for CLL/SLL, APIs have the highest rate (92.22%).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics and clinical-pathologic features for different subtypes and racial groups.

| NHW N=27745 |

HW N=2113 |

Black N=2490 |

API N=2634 |

P | NHW N=15377 |

HW N=825 |

Black N=736 |

API N=732 |

P | NHW N=26248 |

HW N= 824 |

Black N=1922 |

API N= 638 |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLBCL | FL | CLL/SLL | |||||||||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||||||

| male | 54.68 | 57.55 | 58.31 | 52.92 | <.0001 | 49.31 | 47.15 | 51.77 | 50.41 | 0.3018 | 59.07 | 58.01 | 59.47 | 58.93 | 0.9157 |

| female | 45.32 | 42.45 | 41.69 | 47.08 | 50.69 | 52.85 | 48.23 | 49.59 | 40.93 | 41.99 | 40.53 | 41.07 | |||

| Age at diagnosis | 65.4±17.0 | 58.1±18.6 | 52.9±17.6 | 64.1±17.8 | <.0001 | 63.5±14.2 | 58.6±15.0 | 57.0±15.0 | 62.6±14.3 | <.0001 | 70.4±13.7 | 67.7±13.6 | 66.8±13.2 | 68.1±13.4 | <.0001 |

| Age group | |||||||||||||||

| 0-39 | 9.11 | 18.93 | 24.22 | 11.05 | <.0001 | 5.09 | 11.27 | 11.96 | 6.83 | <.0001 | 0.91 | 2.55 | 2.39 | 2.82 | <.0001 |

| 40-64 | 31.98 | 38.38 | 48.39 | 32.76 | 45.51 | 51.27 | 54.89 | 44.81 | 29.94 | 35.92 | 38.55 | 34.33 | |||

| 65-84 | 48.97 | 37.43 | 24.14 | 47.27 | 43.84 | 34.67 | 31.11 | 43.85 | 57.02 | 52.06 | 50.99 | 53.13 | |||

| ≥85 | 9.93 | 5.25 | 3.25 | 8.92 | 5.56 | 2.79 | 2.04 | 4.51 | 12.13 | 9.47 | 8.06 | 9.72 | |||

| Survival tiime (months) | 41.0±1.0 | 46.0±4.9 | 25.0±2.6 | 42.0±4.2 | 0.020 | 127.0±2.1 | 159.0±18.6 | 120.0±11.4 | 145.0±11.8 | 0.168 | 83.0±0.9 | 83.0±5.1 | 64.0±2.3 | 93.0±9.7 | <.0001 |

| Stage | |||||||||||||||

| I | 33.53 | 33 | 27.92 | 33.84 | 33.04 | 30.84 | 30.14 | 30.19 | 4.77 | 5.2 | 5.72 | 7.62 | |||

| II | 18.75 | 21.89 | 17.2 | 24.98 | <.0001 | 15.54 | 18.4 | 14.08 | 19.31 | 0.0012 | 2.39 | 3.22 | 2.91 | 2.76 | <.0001 |

| III | 14.07 | 14.89 | 16.74 | 13.54 | 21.06 | 24.37 | 22.11 | 22.6 | 3.34 | 3.72 | 6.51 | 2.76 | |||

| IV | 33.66 | 30.22 | 38.14 | 27.64 | 30.36 | 26.4 | 33.66 | 27.9 | 89.5 | 87.86 | 84.86 | 86.87 | |||

| Lymph site | |||||||||||||||

| nodal | 32.59 | 30.36 | 29.48 | 31.65 | 0.0037 | 53.24 | 52.86 | 48.1 | 53.44 | 0.0646 | 8.04 | 8.55 | 12.12 | 7.78 | <.0001 |

| extranodal | 67.41 | 69.64 | 70.52 | 68.35 | 46.76 | 47.14 | 51.9 | 46.56 | 91.96 | 91.45 | 87.88 | 92.22 | |||

Cancers diagnosed 1992-2010 in the SEER 9 database. Age at diagnosis (mean±standard deviation); Survival time in months (median±standard deviation); For a categorical variable, percentage. NHW: non-Hispanic white. HW: Hispanic white. API: Asian/Pacific Islander.

3.2 Incidence Rates

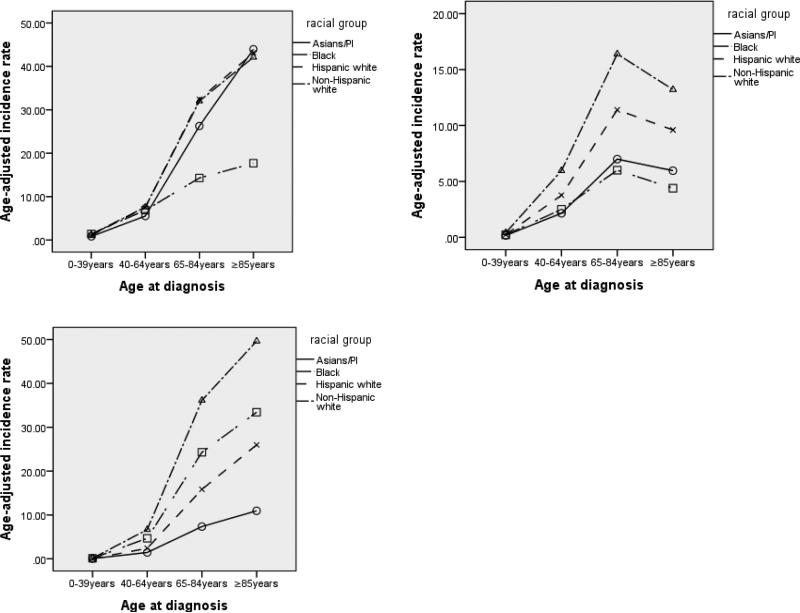

The age-adjusted incidence rates are shown in Table 2 and Figure A1 (Appendix). Overall, DLBCL and CLL/SLL have much higher incidence rates. The age patterns are different across subtypes. For DLBCL and CLL/SLL, the incidence rates increase strictly with age for all races, whereas for FL, the 85+ age group has lower incidence rates than the 65-84 age group. In addition, the racial patterns are different for different subtypes. Specifically, for DLBCL, NHWs, HWs, and APIs have similar incidence rates, while blacks have a significantly lower rate for the 65-84 and 85+ age groups. For FL, for the 65-84 and 85+ age groups, blacks have the lowest incidence rates, which are close to those of APIs. NHWs and HWs have much higher incidence rates. For CLL/SLL, the first two age groups have similar low incidence rates. For the two older age groups, there is a clear separation, with NHWs having the highest incidence rate followed by blacks and then HWs. For DLBCL, male NHWs have a higher incidence rate than HWs, while the order is revised for females. For FL, male NHWs have the highest incidence rate, while APIs have the lowest. Female NHWs also have the highest incidence rate, while blacks have the lowest. For CLL/SLL and both genders, NHWs have the highest incidence rate, followed by blacks and then HWs.

Table 2.

Age-adjusted incidence rates per 100,000 person-years for different racial groups, stratified by age and gender.

| NHW | HW | Black | API | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLBCL | |||||

| All ages | 7.25(7.18-7.33) | 7.16(6.95-7.38) | 4.76(4.59-4.93) | 5.75(5.58-5.93) | 6.87(6.81-6.93) |

| 0-39 | 1.31(1.26-1.35) | 1.07(1.00-1.14) | 1.42(1.32-1.53) | 0.83(0.75-0.91) | 1.2(1.17-1.23) |

| 40-64 | 7.59(7.45-7.73) | 7.55(7.23-7.88) | 6.88(6.54-7.24) | 5.55(5.27-5.85) | 7.29(7.18-7.40) |

| 65-84 | 32.02(31.54-32.51) | 32.39(30.95-33.88) | 14.3(13.32-15.34) | 26.27(25.12-27.47) | 30.11(29.71-30.51) |

| ≥85 | 42.12(40.73-43.54) | 43.13(38.18-48.56) | 17.7(14.64-21.21) | 43.95(39.58-48.67) | 40.80(39.59-42.05) |

| Gender | |||||

| male | 8.99(8.86-9.12) | 8.41(8.07-8.77) | 6.14(5.85-6.45) | 6.81(6.52-7.11) | 8.49(8.38-8.59) |

| female | 5.81(5.72-5.91) | 6.08(5.83-6.35) | 3.65(3.45-3.85) | 4.93(4.72-5.16) | 5.56(5.48-5.63) |

| FL | |||||

| All ages | 4.07(4.01-4.13) | 2.69(2.57-2.83) | 1.62(1.52-1.72) | 1.62(1.53-1.71) | 3.44(3.40-3.48) |

| 0-39 | 0.41(0.38-0.44) | 0.24(0.21-0.28) | 0.22(0.18-0.26) | 0.17(0.14-0.21) | 0.33(0.31-0.34) |

| 40-64 | 5.96(5.84-6.09) | 3.76(3.53-4.00) | 2.50(2.30-2.72) | 2.15(.97-2.34) | 4.92(4.83-5.01) |

| 65-84 | 16.39(16.04-16.74) | 11.40(10.57-12.29) | 6.00(5.38-6.67) | 6.99(6.40-7.61) | 14.19(13.91-14.47) |

| ≥85 | 13.21(12.43-14.01) | 9.60(7.35-12.34) | 4.39(2.94-6.30) | 5.96(4.42-7.85) | 11.90(11.25-12.58) |

| Gender | |||||

| male | 4.42(4.33-4.51) | 2.82(2.62-3.02) | 1.85(1.69-2.03) | 1.83(1.69-1.99) | 3.76(3.70-3.83) |

| female | 3.78(3.71-3.86) | 2.61(2.45-2.77) | 1.43(1.31-1.56) | 1.46(1.34-1.58) | 3.18(3.13-3.24) |

| CLL/SLL | |||||

| All ages | 6.88(6.80-6.95) | 2.92(2.78-3.06) | 4.70(4.52-4.88) | 1.45(1.34-1.55) | 5.82(5.76-5.88) |

| 0-39 | 0.13(0.11-0.14) | 0.05(0.04-0.07) | 0.12(0.09-0.15) | 0.05(0.03-0.07) | 0.10(0.09-0.11) |

| 40-64 | 6.68(6.55-6.81) | 2.41(2.22-2.60) | 4.68(4.39-4.97) | 1.45(1.31-1.61) | 5.47(5.37-5.57) |

| 65-84 | 36.14(35.62-36.65) | 15.84(14.83-16.89) | 24.29(23.00-25.63) | 7.35(6.74-7.99) | 30.79(30.38-31.20) |

| ≥85 | 49.64(48.14-51.19) | 25.98(22.16-30.25) | 33.43(29.16-38.14) | 10.96(8.83-13.44) | 44.22(42.96-45.52) |

| Gender | |||||

| male | 9.40(9.26-9.53) | 3.89(3.63-4.16) | 6.63(6.29-7.00) | 2.05(1.89-2.21) | 7.99(7.88-8.09) |

| female | 4.97(4.89-5.05) | 2.24(2.09-2.41) | 3.38(3.19-3.59) | 1.00(0.90-1.10) | 4.21(4.14-4.27) |

Diagnoses in the period of 1992-2010 in the SEER 13 database. In each cell, estimate (95% CI). Rates were age-adjusted using the U.S. 2000 Census population.

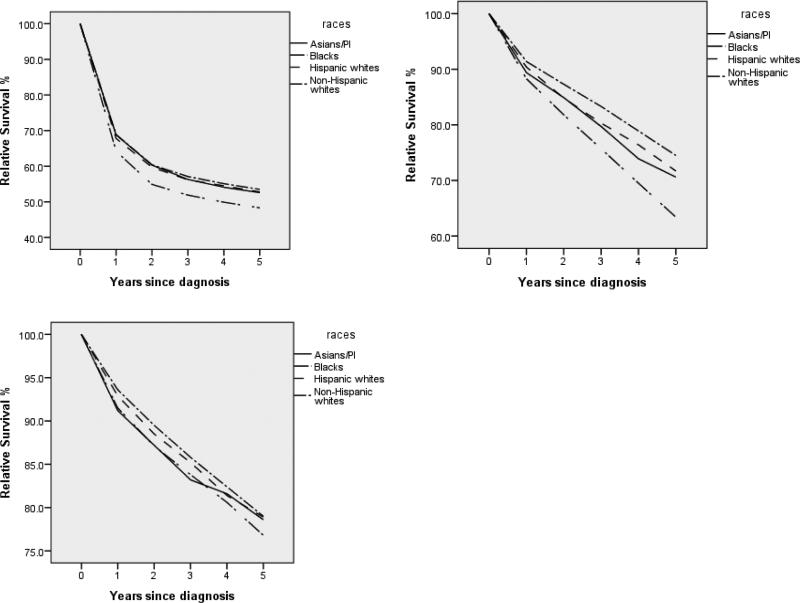

3.3 Survival Rates

For cancers diagnosed in the period of 1992-2005, the five-year relative survival rates, stratified by stage at diagnosis, are shown in Table 3. The survival curves for up to five years are shown in Figure A2 (Appendix). The detailed multivariate Cox regression analysis results are shown in Table A1 (Appendix). For cancers diagnosed in the period of 1999-2005, the five-year relative survival rates are shown in Table A2 (Appendix), and the multivariate Cox regression analysis results are shown in Table A3 (Appendix).

Table 3.

Five-year relative survival rates for different racial groups, stratified by stage at diagnosis.

| NHW | HW | Black | API | Total | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLBCL | ||||||

| Stage I | 67.3(66.3-68.2) | 61.9(59.3-64.4) | 60.0(56.8-63.1) | 65.3(62.3-68.1) | 66.2(65.3-67.0) | <.0001 |

| Stage II | 64.2(62.9-65.4) | 66.4(63.3-69.2) | 61.4(57.6-65.0) | 63.8(60.4-67.0) | 64.3(63.2-65.3) | 0.001 |

| StageIII | 53.2(51.7-54.6) | 52.9(49.3-56.4) | 44.9(40.6-49.1) | 50.3(45.6-54.9) | 52.4(51.1-53.6) | <.0001 |

| StageIV | 41.3(40.3-42.2) | 38.1(35.8-40.4) | 37.2(34.7-39.8) | 34.9(32.0-37.8) | 40.2(39.4-41.0) | <.0001 |

| All stages | 53.5(53.0-54.0) | 52.8(51.5-54.1) | 48.3(46.7-49.8) | 52.6(51.0-54.2) | 53.1(52.7-53.5) | |

| FL | ||||||

| Stage I | 91.5(90.4-92.6) | 90.6(86.4-93.5) | 89.5(84.1-93.1) | 89.8(84.8-93.4) | 91.4(90.4-92.3) | 0.054 |

| Stage II | 84.1(82.4-85.6) | 78.3(72.8-82.7) | 84.6(76.2-90.2) | 80.9(73.6-86.4) | 83.5(82.0-84.9) | 0.011 |

| StageIII | 77.4(75.9-78.8) | 80.2(75.8-83.8) | 71.9(64.9-77.8) | 76.0(69.5-81.3) | 77.5(76.2-78.8) | 0.008 |

| StageIV | 72.2(70.9-73.4) | 70.0(66.0-73.6) | 68.1(62.7-72.9) | 71.1(65.5-76.0) | 71.8(70.7-72.9) | 0.001 |

| All stages | 79.0(78.4-79.6) | 78.9(76.9-80.8) | 76.8(74.1-79.3) | 78.6(76.0-81.0) | 79.0(78.4-79.5) | |

| CLL/SLL | ||||||

| Stage I | 82.1(79.1-84.7) | 78.5(65.7-87.0) | 73.2(62.7-81.1) | 85.7(71.8-93.1) | 81.4(78.7-83.7) | 0.001 |

| Stage II | 70.4(66.1-74.2) | 63.9(44.4-78.1) | 66.6(53.1-77.0) | 75.8(52.0-88.9) | 70.0(66.2-73.5) | 0.056 |

| StageIII | 68.4(65.1-71.5) | 57.0(42.0-69.5) | 65.2(55.6-73.2) | 57.4(37.5-73.0) | 67.3(64.2-70.1) | 0.467 |

| StageIV | 77.1(76.5-77.8) | 72.7(69.8-75.3) | 63.6(61.3-65.9) | 71.1(67.2-74.7) | 76.4(75.8-76.9) | <.0001 |

| All stages | 74.5(74.0-75.0) | 71.7(69.2-74.1) | 63.4(61.5-65.2) | 70.6(67.3-73.7) | 73.9(73.4-74.4) |

Cancers diagnosed in the period of 1992-2005 and followed up to 12/31/2010 in the SEER 18 database. In each cell, estimated rate (95% CI). P-values were generated from multivariate Cox models. Details results are provided in Appendix.

For cancers diagnosed between 1992 and 2005, for DLBCL, significant racial differences were observed for all four stages. There was no consistent pattern across stages. For example, for stage I, NHWs have the best five-year survival rate (67.3%), while blacks have the worst (60.0%). In contrast, for stage IV, NHWs still have the best survival rate (41.3%), while APIs have the worst (34.9%). For FL, the racial difference for stage I is not significant. For the other three stages, significant racial differences were observed; however, there is a lack of a clear pattern across stages. For stages II-IV, the groups with the best survival rates are blacks, HWs, and NHWs, respectively. For CLL/SLL, there is no significant racial difference for stages II and III. For stages I and IV, the groups with the best survival rates are APIs and NHWs, respectively. Figure A2 further shows that the racial differences have different patterns across subtypes. For cancers diagnosed between 1999 and 2005, overall, an improved survival rate was observed compared to the period of 1992 to 2005. Table A2 shows that, for DLBCL, there are significant racial differences for stages I, II, and IV. For FL, significant racial differences were observed for stages III and IV. For CLL/SLL, racial differences were observed for stages I and IV. In general, these observations are different from those presented in Table 3.

4. Discussion

Epidemiologic studies on NHL have been conducted extensively. Most of the existing studies have focused on homogeneous samples. However, multiple studies [17,18,19,20,21] have indicated that the characteristics, incidence rates, and survival rates of certain racial groups are different from others. Examples include observations made on the European population [17], the Koreans [18], the Lebanese [20], the Polish population [21], and others. A limitation shared by some of the existing studies related to racial differences is that the study authors only conducted detailed analyses of a single racial group and made statements on racial difference based on published summary statistics. In contrast, the SEER database analyzed in this study contains data on multiple racial groups collected under the same protocol. In addition, as data on different races are analyzed using the same statistical approach and directly compared, observations made in this study can be found to be more informative than in some previously published studies. The analysis in this study reconfirms the racial differences in multiple aspects. As the analyzed data and statistical approach differ from the previously published studies, we did not try to make a direct comparison with existing results.

4.1 Main Findings on Patients’ Characteristics, Incidence Rates, and Survival Rates

Racial differences were observed for most of the patient characteristics examined in Table 1. In addition, the patterns are not consistent across subtypes. The development of NHL is an extremely complex process, and the etiologic heterogeneity among subtypes has been noted [14]. The observed differences across races and across subtypes reflect the complex interactions of genetic makeup, occupational exposures, infectious conditions, the development of autoimmune diseases, family history, and socioeconomic status [22,23]. The interaction between gender and race and its effect on DLBCL has been noted in the literature [24]. Overall, CLL/SLLs were diagnosed at older ages and later stages, reflecting the indolent nature of the disease and the fact that early-stage CLL/SLLs may not need treatment or be documented.

The incidence rate patterns vary across subtypes and races. A large number of risk factors have been suggested as potentially associated with the etiology of NHL [4]. Evidence scattered in the literature suggests that different subtypes are associated with different sets of risk factors, which may interact with race in varied manners. Immune system suppression has been linked with the risk of aggressive NHLs such as DLBCL, but the evidence is not conclusive for indolent ones such as FL. Further, immune dysregulation differs across races [25]. Environmental and occupational exposures and lifestyle factors are associated with the risk of NHL in a subtypeand race-specific manner. Cigarette smoking, for instance, was associated with an increased risk of FL [26], but the evidence is less clear for some other subtypes. Alcohol consumption was associated with a reduced risk of NHL overall, and the association varies across subtypes [27]. An increased risk of FL and CLL/SLL was found among women who used hair dye [28]. Other potential risk factors include ultraviolet radiation, BMI (body mass index), occupational exposure to organic solvents, dietary intake, and others [28]. Different racial groups have different rates of smoking, drinking, and drug use [29,30], occupations, and lifestyles. The observed differences in incidence rate can be at least partly explained by the differences in such factors. In addition, a large number of genetic, genomic, and epigenetic risk factors for NHL have been suggested, and the molecular markers for different subtypes differ. For example, the t(14;18) chromosomal translocation is the most common cytogenetic abnormality in NHL. It occurs in 70-90% of FLs but only 30-50% of DLBCLs [31]. In contrast, the t(3;22) translocation is the hallmark of DLBCL but less common in FL. More systematic discussions are available in the literature [4,5]. For NHL overall, it has been suggested that the associations between genetic variants and risk vary across races [32]. There are also studies that examine the racial differences in specific genetic variants. For example, a study found a lower percentage of t(11;14) translocation in Chinese people than in other races [33]. However, for most genetic variants, the racial differences still need to be examined. Another possible contributing factor is the variation in diagnosis. Different subtypes are diagnosed at different stages. The racial differences in diagnosis have been reported in the literature [34].

Survival patterns differ across races and subtypes. Some analysis results (for example, those for stages I-III of CLL/SLL) should be interpreted with caution because of the small sample sizes. NHL is highly heterogeneous, with DLBCL mostly being aggressive and FL mostly being indolent. For NHL overall, there has been progress in reducing disparities in survival rates across races; however, such differences still exist [35]. For NHL overall, the IPI (International Prognostic Index) consists of five factors: age, tumor stage, serum concentration of lactate dehydrogenase, performance status, and number of sites of extranodal disease. Patients of different races and subtypes differ in terms of age, tumor stage, and extranodal involvement.

Information on lactate dehydrogenase and ECOG performance status is not available in SEER. For specific subtypes, prognostic indices have also been developed, and the factors involved can vary across races. For example, the FLIPI (Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index) also includes age, extranodal involvement, and stage. Furthermore, multiple environmental risk factors have been implicated in NHL prognosis, and these factors may vary across races. Smoking, for example, has been associated with NHL survival [4]. The evidence is the strongest for FL and possibly for CLL/SLL but weaker for DLBCL, and the rate of smoking varies across races [29,30]. Drinking has been associated with NHL survival, and there is racial difference in drinking rates [36]. Another potential risk factor for survival is BMI. The interaction between race and BMI and its effect on NHL survival was discussed in a recent study [37]. There are a few putative risk factors, including UV radiation and dietary and occupational exposures. Lifestyle and occupation also vary across races. A large number of molecular risk factors have been suggested. In data analysis, race is often included as a controlling variable. However, the interaction between race and molecular risk factors has not been well investigated. Overall, a better survival rate was observed for cancers diagnosed between 1999 and 2005. Such an improvement can be attributed to the effectiveness of newer treatment regimens, as well as changes in environmental risk factors, diagnosis techniques, and others.

4.2 Limitations

This study focused on the three largest subtypes of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which are all B-cell lymphomas. Examining racial differences for other subtypes is potentially of interest. However, an examination of the database suggests that sample sizes for smaller subtypes are small. This can be especially problematic in stratified analysis and can lead to unreliable results. Hence, only the largest three subtypes were analyzed in this study. Additionally, with multiple sites, errors may arise in tumor classification and staging. However, we do not expect a series of systematic errors correlated with ethnicity.

This study may have also been hindered by the multiple coexisting classification schemes. Patients diagnosed before 2001 may have diagnosis codes from earlier ICD-O versions that need to be converted to the ICD-O-3, which may have resulted in a higher proportion of unclassified cases. Clarke and others [38] compared computer-converted ICD-O-3 codes with ICD-O-3 codes generated directly from diagnostic pathology reports and found that the classification might have a reliability problem. Furthermore, data collected in SEER may not be comprehensive enough. Quite a few variables that are potentially associated with etiology and prognosis are not available. Treatment plays an important role in survival. However, SEER only contains information on surgery and radiation but not chemotherapy and other treatments. In addition, information on insurance status, socioeconomic status, and treatment availability, which can all be relevant, is not available. Also, all samples are from the U.S. Although it is of interest to compare the analysis results with the published ones from other countries, this is not pursued because of concerns regarding differences in sample characteristics and statistical methods.

Possible causes for the across-race and subtype differences are discussed. However, it is noted that research on racial differences is still limited. For example, although a large number of genetic risk factors have been suggested, their interactions with race for different subtypes have not been examined. More comprehensive data collection and analysis are needed.

4.3 Summary

The analysis of the SEER data shows that racial differences exist among DLBCL, FL, and CLL/SLL patients in the U.S. in terms of patients’ characteristics, incidence rates, and survival rates. The racial difference patterns vary across subtypes of NHL. Plausible causes of such differences are discussed. More comprehensive data collection and analysis are needed to fully interpret the observed differences. Despite certain limitations, the findings of this study can help researchers better understand the major subtypes of NHL.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor and reviewers for careful review and insightful comments, which have led to a significant improvement of the article.

Funding

This work was supported by Yale Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30 CA16359 from NIH) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 71301162. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Appendix

Figure A1.

Age-adjusted incidence rates. Left-upper panel: DLBCL; Right-upper panel: FL; Left-lower panel: CLL/SLL. Cancers diagnosed between 1992 and 2010 in the SEER 13 database.

Figure A2.

Relative survival up to five years for different racial groups. Left-upper panel: DLBCL; Right-upper panel: FL; Left-lower panel: CLL/SLL. Cancers diagnosed from 1992 to 2005, and followed up to 12/31/2010.

Table A1.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis, stratified by stage at diagnosis.

| Stage I | Stage II | StageIII | StageIV | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | |

| DLBCL | ||||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| male | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||||

| female | 0.811 | 0.770-0.854 | 0.000 | 0.862 | 0.804-0.923 | 0.000 | 0.881 | 0.816-0.951 | 0.001 | 0.834 | 0.796-0.873 | 0.000 |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.037 | 1.035-1.039 | 0.000 | 1.044 | 1.042-1.047 | 0.000 | 1.035 | 1.032-1.038 | 0.000 | 1.027 | 1.025-1.028 | 0.000 |

| Lymph node site | ||||||||||||

| nodal | ref | |||||||||||

| extranodal | 1.239 | 1.175-1.306 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| Ethnicity group | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||||

| Hispanic white | 1.281 | 1.148-1.429 | 0.000 | 0.948 | 0.817-1.101 | 0.486 | 0.991 | 0.834-1.177 | 0.751 | 1.287 | 1.165-1.422 | 0.000 |

| Black | 1.648 | 1.480-1.836 | 0.000 | 1.331 | 1.146-1.547 | 0.000 | 1.457 | 1.265-1.677 | 0.000 | 1.397 | 1.284-1.521 | 0.000 |

| Asian | 0.982 | 0.888-1.086 | 0.730 | 0.966 | 0.856-1.0.91 | 0.581 | 0.999 | 0.862-1.159 | 0.994 | 1.147 | 1.045-1.259 | 0.004 |

| FL | ||||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| male | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||||

| female | 0.819 | 0.748-0.896 | 0.000 | 0.732 | 0.646-0.830 | 0.000 | 0.757 | 0.679-0.844 | 0.000 | 0.751 | 0.691-0.816 | 0.000 |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.073 | 1.068-1.077 | 0.000 | 1.065 | 1.059-1.071 | 0.000 | 1.060 | 1.055-1.065 | 0.000 | 1.051 | 1.047-1.054 | 0.000 |

| Lymph node site | ||||||||||||

| nodal | Ref | ref | ||||||||||

| extranodal | 0.861 | 0.775-0.956 | 0.005 | 1.199 | 1.046-1.375 | 0.009 | ||||||

| Ethnicity group | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||||

| Hispanic white | 1.132 | 0.871-1.472 | 0.345 | 1.363 | 1.018-1.826 | 0.038 | 1.025 | 0.789-1.332 | 0.853 | 1.203 | 0.965-1.501 | 0.101 |

| Black | 1.277 | 0.979-1.666 | 0.071 | 1.437 | 1.037-1.993 | 0.029 | 1.556 | 1.210-2.000 | 0.001 | 1.441 | 1.184-1.753 | 0.000 |

| Asian | 0.784 | 0.603-1.019 | 0.069 | 0.806 | 0.595-1.092 | 0.164 | 1.008 | 0.783-1.297 | 0.951 | 1.018 | 0.814-1.273 | 0.879 |

| CLL/SLL | ||||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| male | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||||

| female | 0.683 | 0.590-0.790 | 0.000 | 0.746 | 0.607-0.917 | 0.005 | 0.716 | 0.599-0.856 | 0.000 | 0.904 | 0.873-0.936 | 0.000 |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.060 | 1.052-1.067 | 0.067 | 1.061 | 1.050-1.071 | 0.000 | 1.056 | 1.048-1.065 | 0.000 | 1.009 | 1.009-1.009 | 0.000 |

| Lymph node site | ||||||||||||

| nodal | ref | |||||||||||

| extranodal | 0.861 | 0.733-1.011 | 0.067 | |||||||||

| Ethnicity group | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | ref | ref | ref | |||||||||

| Hispanic white | 1.349 | 0.910-2.000 | 0.136 | 0.939 | 0.549-1.604 | 0.818 | 1.024 | 0.919-1.140 | 0.671 | |||

| Black | 1.641 | 1.254-2.148 | 0.000 | 1.647 | 1.140-2.380 | 0.008 | 1.457 | 1.364-1.557 | 0.000 | |||

| Asian | 0.716 | 0.444-1.152 | 0.169 | 0.850 | 0.435-1.660 | 0.634 | 0.972 | 0.855-1.105 | 0.664 | |||

Cancer diagnosed from 1992-2005, and followed up to 12/31/2010. HR: hazard ratio.

Table A2.

Five-year relative survival rates for different racial groups, stratified by stage at diagnosis.

| NHW | HW | Black | API | Total | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLBCL | ||||||

| Stage I | 71.1(69.9-72.3) | 65.5(62.-68.2) | 65.4(61.7-68.9) | 38.1(34.7-43.7) | 69.8(68.8-70.8) | <.0001 |

| Stage II | 67.8(66.4-69.2)) | 68.6(65.2-71.8) | 64.0(59.7-67.9) | 54.5(48.9-59.7) | 67.8(66.6-69.0) | 0.009 |

| StageIII | 58.3(56.6-60.0) | 57.0(52.8-60.9) | 48.3(43.4-53.1) | 68.3(64.2-72.0) | 57.2(55.7-58.6) | 0.781 |

| StageIV | 46.2(45.0-47.3) | 41.6(38.9-44.2) | 40.7(37.8-43.7) | 66.8(63.3-70.1) | 44.7(43.7-45.6) | <.0001 |

| All stages | 60.0(59.4-60.7) | 56.7(55.1-58.2) | 53.3(51.4-55.1) | 56.7(54.7-58.6) | 59.0(58.4-59.5) | |

| FL | ||||||

| Stage I | 93.5(92.1-94.7) | 89.3(84.4-92.8) | 89.8(83.4-93.8) | 93.3(86.3-96.7) | 93.2(91.9-94.3) | 0.168 |

| Stage II | 87.2(85.3-88.9) | 79.2(73.1-84.1) | 90.3(79.9-95.4) | 82.6(73.8-88.6) | 86.5(84.8-88.0) | 0.065 |

| StageIII | 80.9(79.2-82.5) | 82.8(78.0-86.6) | 77.1(68.9-83.5) | 81.7(74.4-87.2) | 81.1(79.6-82.5) | 0.028 |

| StageIV | 76.3(74.9-77.7) | 73.1(68.6-77.0) | 67.6(60.9-73.4) | 76.3(59.8-81.6) | 75.6(74.3-76.9) | 0.041 |

| All stages | 84.4(83.7-85.1) | 81.0(78.8-83.1) | 80.1(76.7-83.1) | 83.8(80.6-86.5) | 84.0(83.3-84.6) | |

| CLL/SL | ||||||

| Stage I | 84.8(80.7-88.1) | 78.1(59.1-89.1) | 80.9(66.8-90.0) | 77.7(56.6-89.5) | 84.1(80.4-87.1) | 0.017 |

| Stage II | 72.8(67.6-77.4) | 72.5(44.7-88.0) | 68.9(52.5-80.7) | 78.2(43.2-93.0) | 72.8(68.0-76.9) | 0.430 |

| StageIII | 71.5(67.6-75.0) | 62.5(45.3-75.7) | 61.5(50.0-71.1) | 56.6(33.8-74.2) | 69.5(66.0-72.7) | 0.094 |

| StageIV | 78.5(77.7-79.2) | 75.7(72.4-78.8) | 66.2(63.4-68.8) | 74.0(69.2-78.2) | 78.0(77.3-78.7) | <.0001 |

| All stages | 78.3(77.6-79.0) | 75.2(72.1-78.1) | 66.8(64.3-69.3) | 73.3(68.9-77.3) | 77.8(77.1-78.4) |

Cancers diagnosed in the period of 1999-2005 and followed up to 12/31/2010 in the SEER 18 database. In each cell, estimated rate (95% CI). P-values were generated from multivariate Cox models

Table A3.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of survival, stratified by stage at diagnosis.

| Stage I | Stage II | StageIII | StageIV | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | |

| DLBCL | ||||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| male | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||||

| female | 0.842 | 0.784-0.905 | 0.000 | 0.857 | 0.782-0.939 | 0.001 | 0.872 | 0.790-0.962 | 0.006 | 0.861 | 0.811-0.915 | 0.000 |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.047 | 1.044-1.050 | 0.000 | 1.051 | 1.047-1.055 | 0.000 | 1.037 | 1.033-1.041 | 0.000 | 1.034 | 1.031-1.036 | 0.000 |

| Lymph node site | ||||||||||||

| nodal | ref | |||||||||||

| extranodal | 1.247 | 1.157-1.344 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| Ethnicity group | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||||

| Hispanic white | 1.392 | 1.195-1.622 | 0.000 | 0.955 | 0.784-1.164 | 0.650 | 0.969 | 0.777-1.208 | 0.781 | 1.348 | 1.188-1.529 | 0.000 |

| Black | 1.640 | 1.403-1.917 | 0.000 | 1.394 | 1.145-1.697 | 0.001 | 1.506 | 1.260-1.800 | 0.000 | 1.578 | 1.413-1.763 | 0.000 |

| Asian | 1.105 | 0.971-1.258 | 0.130 | 0.983 | 0.841-1.148 | 0.826 | 1.097 | 0.919-1.310 | 0.306 | 1.250 | 1.113-1.404 | 0.000 |

| FL | ||||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| male | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||||

| female | 0.876 | 0.764-1.004 | 0.057 | 0.736 | 0.616-0.878 | 0.001 | 0.817 | 0.704-0.949 | 0.008 | 0.752 | 0.666-0.848 | 0.000 |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.079 | 1.072-1.086 | 0.000 | 1.080 | 1.071-1.089 | 0.000 | 1.064 | 1.057-1.071 | 0.000 | 1.059 | 1.054-1.065 | 0.000 |

| Lymph node site | ||||||||||||

| nodal | ref | |||||||||||

| extranodal | 1.300 | 1.087-1.553 | 0.004 | |||||||||

| Ethnicity group | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | ref | ref | ref | |||||||||

| Hispanic white | 1.505 | 1.032-2.195 | 0.034 | 1.092 | 0.795-1.499 | 0.587 | 1.260 | 0.943-1..685 | 0.119 | |||

| Black | 1.576 | 0.922-2.694 | 0.096 | 1.544 | 1.124-2.121 | 0.007 | 1.436 | 1.080-1.909 | 0.013 | |||

| Asian | 0.932 | 0.622-1.396 | 0.731 | 0.790 | 0.533-1.170 | 0.240 | 1.054 | 0.776-1.431 | 0.735 | |||

| CLL/SLL | ||||||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| male | ref | ref | ref | ref | ||||||||

| female | 0.657 | 0.526-0.821 | 0.000 | 0.580 | 0.425-0.792 | 0.000 | 0.679 | 0.535-0.861 | 0.001 | 0.912 | 0.868-0.957 | 0.000 |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.064 | 1.053-1.075 | 0.000 | 1.064 | 1.049-1.079 | 0.001 | 1.059 | 1.047-1.071 | 0.000 | 1.008 | 1.008-1.009 | 0.000 |

| Lymph node site | ||||||||||||

| nodal | ||||||||||||

| extranodal | ||||||||||||

| Ethnicity group | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | ref | ref | ||||||||||

| Hispanic white | 1.788 | 0.918-3.483 | 0.088 | 1.442 | 0.808-2.576 | 0.216 | 1.021 | 0.881-1.182 | 0.785 | |||

| Black | 1.679 | 1.160-2.431 | 0.006 | 1.329 | 0.948-1.863 | 0.099 | 1.390 | 1.272-1.519 | 0.000 | |||

| Asian | 1.235 | 0.611-2.500 | 0.557 | 1.736 | 0.922-3.270 | 0.088 | 1.006 | 0.851-1.190 | 0.941 | |||

Cancer diagnosed from 1999-2005, and followed up to 12/31/2010. HR: hazard ratio.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authorship contribution statement

SM designed the study; YL, YW, and ZW conducted data analysis; All authors were involved in writing and approved the final draft.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet] International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon, France: 2013. [December 2013]. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/non-hodgkin.

- 3.Leukemia and Lymphoma Society http://www.lls.org/diseaseinformation/lymphoma/nonhodgkinlymphoma/nhlsubtypes/

- 4.Zhang Y, Dai Y, Zheng T, Ma S. Risk Factors of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Expert Opin Med Diagn. 2011 Nov 1;5(6):539–550. doi: 10.1517/17530059.2011.618185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma S. Risk Factors of Follicular Lymphoma. Expert Opin Med Diagn. 2012 Jul 1;6(4):323–333. doi: 10.1517/17530059.2012.686996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dotan E, Aggarwal C, Smith MR. Impact of Rituximab (Rituxan) on the Treatment of B-Cell Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. PT. 2010;35:148–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shenoy PJ, Malik N, Nooka A, et al. Racial differences in the presentation and outcomes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the United Status. Cancer. 2010;117(11):2530–2540. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffiths R, Gleeson M, Knopf K, Danese M. Racial differences in treatment and survival in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). BMC Cancer. 2010;12(10):625. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flowers CR, Shenoy PJ, Borate U, et al. Examining racial differences in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presentation and survival. Vol. 54. Leukemia & Lymphoma; 2013. pp. 268–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evens AM, Antillón M, Aschebrook-Kilfoy B, et al. Racial disparities in Hodgkin's lymphoma: a comprehensive population-based analysis. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2128–2137. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nabhan C, Byrtek M, Taylor MD, et al. Racial differences in presentation and management of follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the United States: report from the National LymphoCare Study. Cancer. 2012;118:4842–4850. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koshiol J, Lam TK, Gridley G, Check D, Brown LM, Landgren O. Racial differences in chronic immune stimulatory conditions and risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in veterans from the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(4):378–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato I, Booza J, Quarshie WO, Schwartz K. Persistent socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival in the United States: 1973-2007 surveillance, epidemiology and end results (SEER) data for breast cancer and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Registry Manag. 2012;39(4):158–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, Hartge P, Weisenburger DD, Linet MS. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992-2001. Blood. 2006;107(1):265–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shenoy PJ, Malik N, Sinha R, Nooka A, Nastoupil LJ, Smith M, Flowers CR. Racial differences in the presentation and outcomes of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and variants in the United States. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011;11(6):498–506. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ederer F, Axtell LM, Cutler SJ. The relative survival rate: a statistical methodology. NCI Monograph. 1961;6:101–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcos-Gragera R, Allemani C, Tereanu C, De Angelis R, Capocaccia R, Maynadie M, et al. Survival of European patients diagnosed with lymphoid neoplasms in 2000-2002: results of the HAEMACARE project. Haematologica. 2011;96(5):720–8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.034264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoon SO, Suh C, Lee DH, Chi HS, Park CJ, Jang SS, et al. Distribution of lymphoid neoplasms in the Republic of Korea: analysis of 5318 cases according to the World Health Organization classification. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(10):760–4. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith A, Howell D, Patmore R, Jack A, Roman E. Incidence of haematological malignancy by sub-type: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(11):1684–92. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sader-Ghorra C, Rassy M, Naderi S, Kourie HR, Kattan J. Type distribution of lymphomas in Lebanon: five-year single institution experience. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(14):5825–8. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.14.5825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szumera-Ciećkiewicz A, Gałązka K, Szpor J, Rymkiewicz G, Jesionek-Kupnicka D, Gruchała A, et al. Distribution of lymphomas in Poland according to World Health Organization classification: analysis of 11718 cases from National Histopathological Lymphoma Register project - the Polish Lymphoma Research Group study. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(6):3280–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koshiol J, Lam TK, Gridley G, Check D, Brown LM, Landgren O. Racial differences in chronic immune stimulatory conditions and risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in veterans from the United States. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:378–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smedby KE, Hjalgrim H. Epidemiology and etiology of mantle cell lymphoma and other non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes. Seminar in Cancer Biology. 2011;21:293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komrokji RS, Al Ali NH, Beg MS, et al. Outcome of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma in the United States Has Improved Over Time but Racial Disparities Remain: Review of SEER Data. Clinical Lymphoma Myeloma and Leukemia. 2011;11:257–260. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McFall AM, Dowdy DW, Zelaya CE, Murphy K, Wilson TE, Young MA, Gandhi M, Cohen MH, Golub ET, Althoff KN. Women's Interagency HIV Study. Understanding the disparity: predictors of virologic failure in women using highly active antiretroviral therapy vary by race and/or ethnicity. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(3):289–98. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a095e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morton LM, Hartge P, Holford TR, et al. Cigarette smoking and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a pooled analysis from the international lymphoma epidemiology consortium (InterLymph) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:925–933. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morton LM, Zheng T, Holford TR, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a pooled analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:469–476. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70214-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Sanjose SD, Bracci PM, et al. Personal use of hair dye and the risk of certain subtypes of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:1321–1331. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bachman JG, Wallace JM, Jr, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Kurth CL, Neighbors HW. Racial/Ethnic differences in smoking, drinking, and illicit drug use among American high school seniors, 1976-89. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(3):372–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.3.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/nhsda/ethnic/ethn1010.htm.

- 31.Chang CM, Wang SS, Dave BJ, Jain S, Vasef MA, Weisenburger DD, Cozen W, Davis S, Severson RK, Lynch CF, Rothman N, Cerhan JR, Hartge P, Morton LM. Risk factors for non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes defined by histology and t(14;18) in a population-based case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(4):938–47. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skibola CF, Bracci PM, Nieters A, Brooks-Wilson A, de Sanjosé S, Hughes AM, et al. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and lymphotoxin-alpha (LTA) polymorphisms and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the InterLymph Consortium. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;171:267–76. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong KF, Chan JK. Cytogenetic abnormalities in chronic B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders in Chinese patients. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1999;111:55–60. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(98)00216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang M, Burau KD, Fang S, Wang H, Du XL. Ethnic variations in diagnosis, treatment, socioeconomic status, and survival in a large population-based cohort of elderly patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2008;113(11):3231–41. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pulte D, Redaniel MT, Brenner H, Jeffreys M. Changes in survival by ethnicity of patients with cancer between 1992-1996 and 2002-2006: is the discrepancy decreasing? Ann Oncol. 2012;23(9):2428–34. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herd D, Grube J. Black identity and drinking in the US: a national study. Addiction. 1996;91(6):845–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.91684510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leo QJ, Ollberding NJ, Wilkens LR, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Le Marchand L, Maskarinec G. Obesity and non-Hodgkin lymphoma survival in an ethnically diverse population: the Multiethnic Cohort study. Cancer Causes Control. 2014 Jul 29; doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0447-6. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clarke CA, Undurraga DM, Harasty PJ, Glaser SL, Morton LM, Holly EA. Changes in cancer registry coding for lymphoma subtypes: reliability over time and relevance for surveillance and study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:630–638. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]