Abstract

In spite of substantial advances in defining the immunobiology and function of structural cells in lung diseases there is still insufficient knowledge to develop fundamentally new classes of drugs to treat many lung diseases. For example, there is compelling need for new therapeutic approaches to address severe persistent asthma that is insensitive to inhaled corticosteroids. Although the prevalence of steroid-resistant asthma is 5–10%, severe asthmatics require a disproportionate level of health care spending and constitute a majority of fatal asthma episodes. None of the established drug therapies including long-acting beta agonists or inhaled corticosteroids reverse established airway remodeling. Obstructive airways remodeling in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), restrictive remodeling in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and occlusive vascular remodeling in pulmonary hypertension are similarly unresponsive to current drug therapy. Therefore, drugs are needed to achieve long-acting suppression and reversal of pathological airway and vascular remodeling. Novel drug classes are emerging from advances in epigenetics. Novel mechanisms are emerging by which cells adapt to environmental cues, which include changes in DNA methylation, histone modifications and regulation of transcription and translation by noncoding RNAs. In this review we will summarize current epigenetic approaches being applied to preclinical drug development addressing important therapeutic challenges in lung diseases. These challenges are being addressed by advances in lung delivery of oligonucleotides and small molecules that modify the histone code, DNA methylation patterns and miRNA function.

Keywords: Asthma, COPD, DNA methylation, fibrosis, histone code, noncoding RNA

1. Introduction

Epigenetic regulation of gene expression and protein abundance is carried out by a set of highly conserved processes that contribute to normal development and adaptation to changes in cellular and organ homeostasis. Any disease that alters the cellular milieu to the point of triggering adaptive changes in phenotype will likely involve one or more epigenetic mechanisms. Transcription is regulated by DNA methylation, often at CpG islands in promoters of protein-coding genes, and by posttranslational modification of histones. Noncoding RNAs also modify transcription, mRNA processing and mRNA stability to modulate protein abundance. Because DNA methylation, the histone code and microRNA-mediated gene silencing are highly conserved processes many clinically diverse conditions should respond to drugs that modify these epigenetic regulatory systems. It is also clear that epigenetic modifications can be cell and tissue specific, which suggests epigenetic therapies might be designed to be directed to particular diseases. It is also very important to note that changes in epigenetic modifications of DNA and histones and changes in miRNA expression may be a consequence of a disease as well as cause the disease. Substantial effort is now being spent defining the timing and the necessity of epigenetic adaptations in lung diseases. Many of those studies have identified potential new drug targets which are summarized in this review. The working hypothesis is that antagonizing causative epigenetic features of disease or antagonizing adaptive epigenetic responses might favor a return to more normal structure and function of the lung. There are two processes of particular interest in this regard - lung inflammation and subsequent lung remodeling. Lung inflammation is often well controlled by corticosteroid therapy, but in severe asthmatics may require additional approaches including novel antibody-based therapies targeting IgE, thymic stromal lymphopoietin or interleukin-5. For more information on these important developments in asthma therapy the reader is referred to recent advances in antibody-based antiinflammatory therapies (Gauvreau et al., 2014; Humbert et al., 2014; Bel et al., 2014; Ortega et al., 2014). In this review we will cite studies of epigenetic modifiers in lung disease as well as other diseases when they provide proof of key principles, but the focus will be on novel therapy of pulmonary hypertension, restrictive lung diseases and obstructive lung diseases. The reader should consult other recent reviews for a general appreciation of advances in epigenetic therapy in other organ systems (Dhanak & Jackson, 2014; Haldar & McKinsey, 2014; Natarajan, 2011; Tao et al., 2014).

In all cases the appeal of targeting epigenetic mechanisms is that they are reversible biochemical processes amenable to manipulation with small molecule drugs, and in some cases small oligonucleotides. This contrasts with mutations in genomic and mitochondrial DNA most of which are uncorrectable in a clinical setting. Identifying the best epigenetic targets and developing the best therapeutic strategies is a topic of great interest and high significance for developing novel drugs for lung diseases. In addition to targeting inflammation we suggest targeting tissue remodeling will be a fruitful strategy. Tissue remodeling is a common feature of pulmonary vascular disorders as well as obstructive and restrictive diseases of the airways. The key aspects of pathology of each disease will be described along with some emerging epigenetic targets. Recent progress in preclinical studies of small molecule and oligonucleotide modifiers will be summarized with the goal of focusing attention on promising therapeutic approaches that may add to the current standards of care.

2. Tissue remodeling in lung diseases

2.1 Pulmonary hypertension

Patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH) suffer from abnormally high pulmonary artery blood pressure that leads to right ventricular dysfunction.. In severe pulmonary arterial hypertension (Group I PH, PAH), the normally thin-walled, highly compliant pulmonary arteries become thickened, stiffer and hypercontractile (Chan & Loscalzo, 2008; Humbert et al., 2004; Rabinovitch, 2008). Peripheral pulmonary arteries become occluded by neointimal and plexiform lesions which are hypothesized to contribute to disease severity (Pietra et al., 2004; Tuder et al., 2007; Yi et al., 2000). Pathological vascular remodeling is due to increased proliferation and decreased apoptosis of endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and adventitial fibroblasts. The resulting wall hypertrophy may also be due to disrupted autophagy, enhanced progenitor cell migration and differentiation as well as immune cell migration and differentiation. The biochemical processes that regulate these diverse processes are the subject of intense study, and are targets of numerous drugs in preclinical development (Morrell et al., 2013; Tuder et al., 2013). In addition to small molecule inhibitors of cell signaling pathways, microRNAs (miRNA) have become intensely studied molecular targets for novel anti-remodeling therapy (White et al., 2012). There is also emerging evidence for altered DNA methylation (Archer et al., 2010) and histone posttranslational modifications (Xu et al., 2010) in pulmonary hypertension, both of which are targets for new drug development (Saco et al., 2014).

2.2 Obstructive lung diseases – Asthma and COPD

Remodeling of the airways occurs in asthma and COPD resulting in obstruction of airflow. The pathophysiology of the two diseases is quite different, but there are some common features relevant to identifying novel targets for anti-remodeling drug therapy. Asthma is a multifactorial syndrome triggered by allergens, infections, aspirin, exercise or cold air that results in symptoms of obstruction. The wheezing, and shortness of breath is frequently, but not always, reversible with bronchodilators. Treatment with inhaled corticosteroids usually controls allergic inflammation and prevents asthma episodes. Acute therapy with beta agonists relaxes airway smooth muscle and relieves the symptoms in most subjects. However, in a significant minority of asthmatics (5–10%) airway obstruction is not reversible (Chipps et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2007). In severe cases steroid resistance and lack of response to beta agonists can result in potentially fatal attacks (Wenzel, 2005). The lack of adequate treatment of severe asthma makes a compelling case for developing new therapies. Recent progress in novel anti-inflammatory therapy is described elsewhere (Bel et al., 2014; Humbert et al., 2014; Gauvreau et al., 2014; Ortega et al., 2014). The goal of our prospective analysis is to describe potential targets for anti-remodeling therapy.

Aside from bronchial thermoplasty there are no clinically proven therapies to reverse airway obstruction in severe asthmatics, whether they are steroid-resistant or not. What is needed is an effective way to prevent or reverse airway smooth muscle hyperplasia and hypertrophy, mucosal metaplasia, submucosal and parenchymal fibrosis and persistent inflammation. This is a challenging task because multiple cell types contribute to airway and vascular remodeling and no single agent is likely to reverse all features of pathological remodeling. Thus, it is imperative that we identify drug targets that affect those cells most responsive to treatment.

Therapy of COPD overlaps with asthma therapy in that corticosteroids are used for their anti-inflammatory effects and beta agonists for bronchodilation. A key difference between asthma and COPD is that obstruction is not fully reversible in COPD. Patients with COPD often present with emphysema, bronchitis or both. Smoking is a common insult that elicits mucosal hyperplasia and excess mucous production as well as smooth muscle hypertrophy in the small airways. In both asthma and COPD inflammation is a proximal event leading to symptoms, but there are key differences in the immune cell infiltrates; eosinophilia in many asthmatics versus neutrophils in COPD. Another key difference is destruction of elastin in the lung parenchyma in COPD by neutrophil elastases coincident with increased collagen deposition. This suggests that optimal therapy of COPD would include drugs to enhance parenchymal repair. In both COPD and asthma significant structural changes occur in the airways secondary to cell proliferation, cellular hypertrophy and fibrosis. The initiating insults are different, but there are common cellular targets (epithelial cells, smooth muscle, fibroblasts and immune cells) (Figure 1). Common cell types suggests there might be common molecular events required for remodeling and repair that will be suitable targets for novel anti-remodeling drugs.

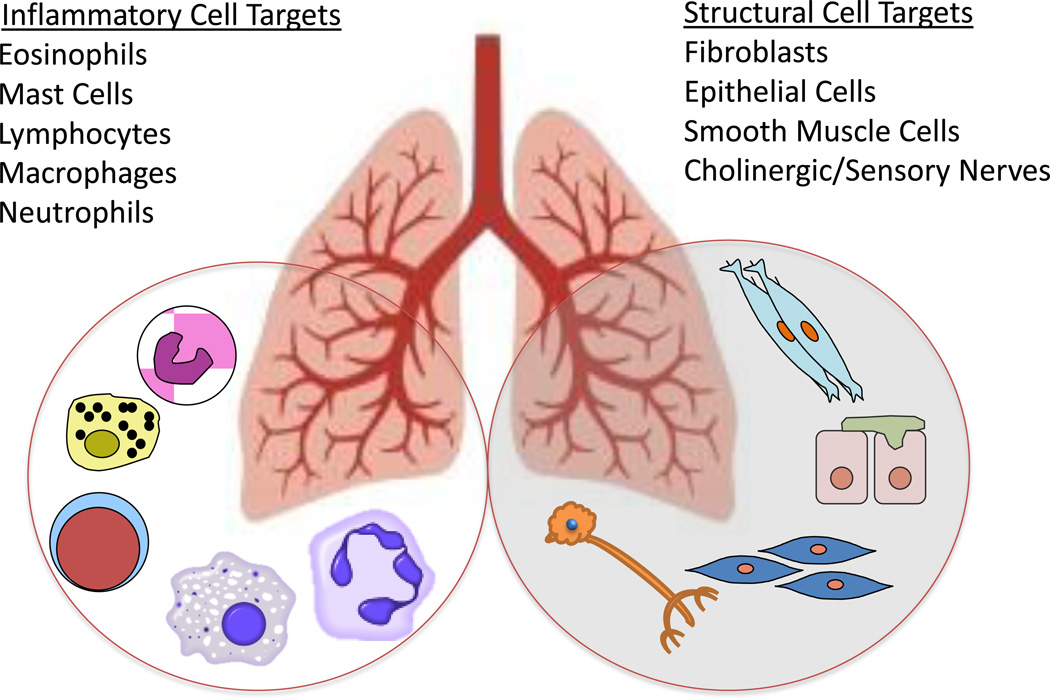

Figure 1.

Lung cells involved in airway, vascular and parenchymal remodeling are potential targets for novel epigenetic therapies designed to prevent or repair remodeling. Both inflammatory and structural cells contribute to remodeling in asthma, COPD, IPF and pulmonary hypertension. The contributions of epigenetic processes to the function of each cell type in the lung is a topic of intense interest and rapid progress in lung cell biology.

2.3 Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)

IPF is a syndrome characterized by diffuse damage to alveoli of unknown etiology. It is thought to involve interstitial pneumonia and repeated bouts of alveolitis. Inflammation, oxidative stress and proteases of the coagulation cascade are thought to increase proliferation and reduce apoptosis of fibroblasts which synthesize inappropriate amounts of extracellular matrix proteins. There are several recent reviews of the mechanisms and novel targets of drug therapy for IPF that should be consulted for a broader perspective (Barkauskas & Noble, 2014; Baroke et al., 2013; Blackwell et al., 2014; Lota & Wells, 2013).

Several fundamental questions arise about targeting tissue remodeling in lung diseases. What are the cell types that should be targeted in epigenetic therapy (Figure 1)? What are the epigenetic processes contributing to lung remodeling (Figure 2)? Are there drug targets common to all remodeling lung tissues – eg. proteins promoting immune cell differentiation? Are there unique targets that could be hit to elicit disease-specific effects, such as regulation of bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 (BMPR2) for therapy of pulmonary vascular remodeling, smooth muscle contractile proteins in asthma and COPD, or matrix remodeling enzymes in IPF? Our view is that druggable targets involved in lung remodeling and repair include enzymes that catalyze DNA methylation and demethylation, enzymes that catalyze posttranslational modifications of histones, and the noncoding RNAs - both microRNAs and long noncoding RNAs. We describe below potential targets as well as existing drugs that target each class of epigenetic regulator. Most studies are early stage preclinical trials or in many cases extrapolation of studies of lung cancer. In spite of the daunting complexities of multigenic, multifactorial chronic lung diseases there are opportunities presented by advances in epigenetics combined with advances in lung-directed delivery of small molecules and oligonucleotides. Examples of epigenetic targets are organized by biochemical and molecular classes and current progress in drug development is described for each clinical syndrome.

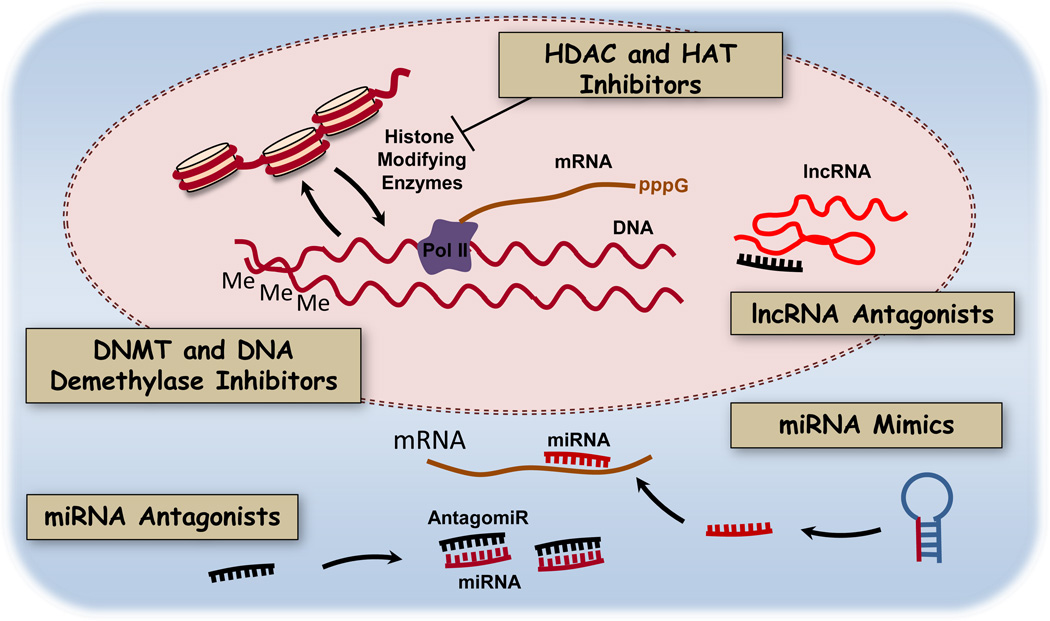

Figure 2.

Epigenetic processes in lung cells that mediate cell adaptation and tissue remodeling. Conserved biochemical processes in lung cells may be valid therapeutic targets for small molecule inhibitors of DNA methylation and histone modifications or oligonucleotide antagonists of short and long noncoding RNAs (miRNAs, lncRNAs). MiRNA mimics could be delivered to rescue miRNA function when it is dysregulated in disease.

3. Epigenetic control of gene expression in lung tissue remodeling

3.1 DNA methylation and inhibitors

DNA methylation normally regulates access of the transcriptional machinery to promoter loci and thus determines the set of genes expressed in a given tissue at any particular time (Figure 2). There has been rapid progress in studies of DNA methytransferase (DNMT) inhibitors and demethylase inhibitors, particularly in cancer chemotherapy (Gros et al., 2012). The data on DNA methylation patterns in lung diseases other than lung cancer are less extensive, but some interesting patterns have emerged that are relevant to new molecular interventions in asthma, COPD and IPF.

3.1.1 Asthma

In patients with asthma hypermethylation and hypomethylation of DNA have been reported in a number of genes in lung biopsies and postmortem samples. In some cases, differences in methylation correlated with functionally important differences in gene expression. For example, increased methylation of the STAT5A gene correlated with decreased expression of STAT5A in the asthmatic samples (Stefanowicz et al., 2012). Differences in DNA methylation might be intrinsic to asthma phenotypes, but they also might have been induced by allergen exposure. The latter possibility is supported by results from mouse models of asthma showing dynamic changes in DNA methylation from allergen challenge (Cheng et al., 2014; Shang et al., 2013). In support of allergen-induced changes in DNA methylation, ovalbumin sensitization of mice decreased DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) mRNA abundance which correlated with increased methylation of the DNMT1 gene (Verma et al., 2013). HDM sensitization of mice reduced global methylation and increased global hydroxymethylation which correlated with decreased DNA methyltransferase 3A (DMT3A) and increased ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenase 1 respectively (Cheng et al., 2014). Furthermore, mice deficient in DMT3A in T-cells exhibit a higher degree of eosinophilia, more severe inflammation, and increased IL-13 secretion from splenocytes following ovalbumin challenge (Yu et al., 2012). These results indicate that DNMT activity limits asthma severity. However, acute inhibition of DNMT activity with 5-azacytidine, a nonselective inhibitor of DNA methyltransferases reduced airway hyperreactivity and inflammation in ovalabumin (OVA)-challenged mice, possibly due to increased numbers of regulatory T cells (Wu et al., 2013). Experiments using 5-azacytidine are informative but is possible some effects might be unrelated to DNMT inhibition. Additional studies utilizing more selective drugs are warranted. Taken together these studies demonstrate that DNA methylation is altered in asthma, possibly due to differential expression of DNMTs. The role of DNA methylation in asthma pathogenesis is complex and requires further investigation to identify appropriate drug targets.

3.1.2 COPD

In patients with COPD DNA methylation is also altered in a complex pattern similar to that seen in asthma in which there is hypermethylation of some loci and hypomethylation of others (Guzmán et al., 2012; Qiu et al., 2012; Vucic et al., 2014). Genes that have been identified as differentially regulated in COPD include components of the PI3K/Akt and anti-oxidant NFE2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) pathways (Vucic et al., 2014). Both pathways have been identified as treatment targets for COPD (Boutten et al., 2011; Bozinovski et al., 2006; Hosgood et al., 2009). CpG hypermethylation was observed in the PTEN and NFE2L2 (Nrf2) genes which correlated with reduced expression of their respective gene products. The Nrf2 pathway is anti-inflammatory and protects against oxidative stress in COPD (Boutten et al., 2011). PTEN is a negative regulator of PI3K/AKT signaling. PI3K/AKT signaling is thought to contribute to inflammation, remodeling, and proteolysis in COPD (Bozinovski et al., 2006). Thus, CpG hypermethylation appears to antagonize protective pathways and promote pathogenic pathways in COPD. Conversely, hypomethylation of the HDAC6 promoter has been linked to elevated expression of HDAC6 in COPD (Lam et al., 2013). HDAC6 is thought to contribute to cigarette smoke-mediated epithelial dysfunction in COPD by promoting autophagy (Lam et al., 2013). In addition, cigarette smoke has been linked to altered expression of DNMTs and alterations in CpG methylation highlighting its role in DNA structure in COPD (Liu et al., 2010). When DNA is hypermethylated therapies targeting DNMT may be beneficial, but further work is needed to determine whether altered DNA methylation is a cause or consequence of COPD.

3.1.3 IPF

Studies of DNMTs in IPF have reported either increased expression or enhanced promoter binding of DNMT-1 and DNMT-3a. Both DNA hypermethylation and hypomethylation have been observed in IPF (Cisneros et al., 2012; Coward et al., 2014; Dakhlallah et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2010; Rabinovich et al., 2012; Sanders et al., 2012). Many of these alterations in DNA methylation correlate with differences in gene expression. Some examples include hypermethylation of the cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and PTGER2 promoters correlating with reduced gene expression (Coward et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2010). Interestingly, the miR-17~92 cluster promoter was hypermethylated in IPF correlating with reduced expression of miR-17~92 but also increased expression of DNMT-1, a target of miRNAs in the miR-17~92 cluster (Dakhlallah et al., 2013). This example highlights the multi-layered complexity of epigenetic regulation and begs the question of whether an alteration in miR-17~92 cluster expression or DNMT-1 expression was the initiating event in this imbalanced regulatory loop. The key question for epigenetic therapy of IPF is how to intervene to reestablish a normal regulatory circuit.

Studies of nucleoside inhibitors of DNMT suggest that molecular intervention is a tractable problem. Bleomycin-treated mice exhibited reduced expression of miR-17~92, elevated DNMT-1 expression and DNA hypermethylation (Dakhlallah et al., 2013). Inhibition of DNMT by 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (decitabine) enhanced miR 17~92 expression and reduced expression of profibrotic genes including collagen 1A1 and connective tissue growth factor (Dakhlallah et al., 2013). In a separate study, treatment of IPF fibroblasts with decitabine abrogated prostaglandin E2 resistance in these cells by increasing expression of the E prostanoid 2 receptor (encoded by PTGER2) which has a hypermethylated promoter in IPF (Huang et al., 2010). Furthermore, decitabine treatment of IPF fibroblasts reduced collagen I expression and reduced proliferation in response to prostaglandin E2 (Huang et al., 2010). These initial cell based studies and preclinical animal studies indicate that IPF may respond to treatment with DNMT inhibitors. However, it should be noted that even though decitabine is an inhibitor of DNMT, it also has effects independent of DNA methylation that enhance apoptosis. Thus, further investigations are warranted using more selective inhibitors of DNA methyltransferases to determine whether altered DNA methylation is a cause or consequence of IPF pathogenesis.

3.2 Histone modifications and inhibitors

Histone post-translation modifications such as acetylation and methylation are profoundly important regulators of transcription comprising key components of the “histone code” initially described in 1964 by Vincent Allfrey (Allfrey et al., 1964; Jenuwein & Allis, 2001). These post-translational modifications regulate chromatin structure directly, presumably by charge effects, or by recruiting chromatin remodeling enzymes (Bannister & Kouzarides, 2011). Typically, histone lysine acetylation is permissive for transcription. Histone methylation can be permissive or restrictive depending upon the methylated residue. As an example, H3K4 di/tri-methylation is permissive while H3K9 di/tri-methylation is restrictive. These modifications are regulated by enzymes that are targets of small molecule inhibitors (Rodríguez-Paredes & Esteller, 2011). Histone acetylation is regulated by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs). Histone methylation is regulated by histone lysine or arginine methyltransferases and histone demethylases. Serine residues on histones can also be phosphorylated but this area is less well studied than histone methylation and acetylation. Disease-specific differences in the histone code have been assigned to changes in activity or expression of histone modifying enzymes. Many studies suggest these differences are significant contributors to asthma, COPD, and IPF. Typically differences in histone acetylation and methylation have been linked to either a difference in enzyme activity or chromatin binding in a disease state. Essentially, an imbalance of the enzymes responsible for maintaining the “on” and “off” chromatin states exists in many disease states including lung diseases (see Figure 2).

3.2.1 Asthma

In asthmatic humans, HDAC activity is reduced and HAT activity is elevated in alveolar macrophages and bronchial biopsies (Cosío et al., 2004; Ito et al., 2002). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with severe asthma have even less histone deacetylase activity than non-severe asthmatic samples which correlated with steroid insensitivity (Hew et al., 2006). The reduction in histone deacetylase activity correlated with decreases in HDAC1 and HDAC2 protein abundance, but no difference in histone acetyltransferase protein abundance was observed. Also, elevated HATs (CBP, PCAF, p300) bound to chromatin at the CXCL8 promoter correlated with elevated histone H3 pan-acetylation and enhanced expression of CXCL8 in airway smooth muscle cells from patients with asthma (John et al., 2009). Reduced G9A methyltransferase bound to chromatin at the VEGF promoter correlated with reduced H3K9 trimethylation and enhanced expression of VEGF in airway smooth muscle cells from patients with asthma (Clifford et al., 2012). Taken together, these studies indicate that histone modifying enzyme expression, binding, and activity are altered in asthma and correlate with altered post-translational modifications. Reduced HDAC activity in asthma may promote enhanced expression of pro-inflammatory and pro-remodeling genes which presumably worsens symptoms. The correlations of histone modifications and asthma pathogenesis are provocative, but further work is needed to establish whether alterations in histone acetylation are a cause or consequence of asthma phenotypes.

In either case there is preclinical evidence that altering HDAC activity alters airway hyperreactivity, a hallmark of asthma in humans and in mouse models of asthma. Treatment of mice with trichostatin A, a non-selective HDAC inhibitor, reduced airway hyperresponsiveness and remodeling, but conflicting results exist regarding effects on inflammation (Banerjee et al., 2012; Choi et al., 2005; Royce et al., 2012). The effects of trichostatin A on experimental asthma in mice appeared to be due to alterations in calcium signaling thus discounting the role of epigenetic effects (Banerjee et al., 2012). Recent studies support the notion that HDAC inhibitors may prove to be effective bronchodilators by enhancing acetylation of substrates other than histones such as HSP20 and cortactin (Li et al. AJP Cell 2014; Chen et al. 2013 ; Karolczak-Byatti et al. 2011). Beneficial effects of HDAC inhibitors is paradoxical in asthma because histone acetylation is increased in disease. The evidence to date suggests the benefit of HDAC inhibition in asthma may be primarily due to acetylation of non-histone substrates. This raises interesting questions about the future role of HDAC inhibition as acute bronchodilators versus long term epigenetic modifiers.

Higher histone acetylation in asthma suggests a better approach for chronic epigenetic therapy will be drugs targeting HATs. However, development of clinically useful HAT inhibitors has lagged that of HDAC inhibitors due in part to the poor selectivity of natural product inhibitors such as curcumin and the low druggability of the catalytic domain of histone acetyltransferases (reviewed by Arrowsmith et al., 2012). One of the most promising candidates is C646, a competitive inhibitor of p300 that reduces histone acetylation, radiosensitizes lung cancer cells and causes cell cycle arrest in leukemia cells (Bowers et al., 2010; Gao et al., 2013; Oike et al., 2014). The effects of HAT inhibition with siRNA or C646 need to be tested in cells from asthmatics and in animal models of asthma.

3.2.2 COPD

As seen in patients with asthma, samples from patients with COPD also exhibit alterations in histone modifying enzymes that correlate with alterations in histone post-translational modifications. Reductions in mRNA abundance for HDACs 2, 5 and 8 as well as a reduction in HDAC2 protein abundance and HDAC activity were observed in lung tissue and macrophages (Ito et al., 2005). Reduced HDAC expression correlated with elevated IL-8 expression and greater H4 pan-acetylation at the IL-8 promoter (Ito et al., 2005). Conversely elevated HDAC1 expression was observed in epithelial biopsies from patients with COPD and positively correlated with the expression of beta-defensin 1 (Andresen et al., 2011). Interestingly, smoking alone was sufficient to elevate H4 pan-acetylation and reduce the expression of some HDAC isoforms (Ito et al., 2005). Cigarette smoke alone is a powerful modulator of histone post-translational modifications because it reduces HDAC activity and reduces HDAC expression, highlighting the importance for indicating whether samples were obtained from smokers or non-smokers (Adenuga et al., 2009; Lakshmi et al., 2014; Szulakowski et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2006). Elevated H3 pan-acetylation and H4 pan-acetylation have also been observed in lung tissue and airway smooth muscle cells (H4 pan-acetylation only) from patients with COPD. (Raidl et al., 2007; Szulakowski et al., 2006). Elevated H4 pan-acetylation in the VEGF promoter, typically considered a “permissive” transcription modification, correlated with reduced VEGF expression in airway smooth muscle from patients with COPD, illustrating the complex nature of the histone code. Sirtuin-1 (SIRT1) expression and deacetylase activity were reduced in peripheral lung tissues from patients with COPD (Nakamaru et al., 2009; Rajendrasozhan et al., 2008). Reduced SIRT1 activity correlated with increased expression of MMP9 and H4 pan-acetylation (Nakamaru et al., 2009). It should be noted that non-histone substrates for SIRT1 and HDAC2 have also been linked to the pathophysiology of COPD. FOXO3, TIMP-1, and RelA are substrates for SIRT1 (Rajendrasozhan et al., 2008; Yao et al., 2012; Yao et al., 2013). Nrf2 and the glucocorticoid receptor are substrates for HDAC2 (Ito et al., 2006; Mercado et al., 2011). Taken together these studies indicate that a deficiency in histone deacetylase activity may exist in COPD and that an imbalance between histone acetylases and deacetylases contributes to disease specific alterations in gene expression. Additional studies are warranted to determine whether these alterations in enzyme activity are a cause or consequence of COPD. In addition, non-histone protein modifications catalyzed by HDACs may also contribute to inflammation and remodeling in COPD. Epigenetic studies of asthma and COPD indicate a trend towards transcriptionally “permissive” histone modifications due to differences in enzymatic activity or binding to chromatin. If these epigenetic changes contribute to disease (either as a cause or consequence) then reversing or preventing the epigenetic changes might have therapeutic benefit. From this hypothesis one would predict drugs that inhibit HATs, histone methyltransferases or DNMTs may be appropriate candidates for further preclinical studies (Table 1). Conversely, compounds that selectively upregulate the activity and/or expression of HDACs or histone demethylases might also be therapeutically useful and should also be investigated in preclinical studies. Evidence from the COPD literature highlights the potential of natural products to upregulate histone deacetylase expression. In a mouse model of COPD, treatment with the plant flavonoid quercetin increased SIRT1 expression, reduced MMP9 and MMP12 expression, and reduced acetylation at their respective promoters in vitro (Ganesan et al., 2010). In addition, theophylline activates HDAC2 by inhibiting PI3K-δ and in combination with corticosteroids abrogates corticosteroid insensitivity in COPD (Cosio et al., 2004; Ford et al., 2010; Ito et al., 2002; To et al., 2010). Whether other small molecule drugs are able to upregulate HDAC activity or expression is an open question with high translational significance.

Table 1.

Epigenetic modifiers of lung disease in preclinical studies

| Mechanism | Disease/model | Drug | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT inhibitors | Asthma, OVA mouse | 5-azacytidine | Wu et al., 2013 |

| IPF, bleomycin mouse model | Decitabine | Dakhlallah et al., 2013 | |

| IPF fibroblasts | Decitabine | Huang et al., 2010 | |

| Histone acetyltransferase inhibitors | Lung cancer | C646 | Gao et al., 2013 |

| HDAC inhibitors | Asthma, OVA mouse | Trichostatin A | Banerjee et al., 2012 |

| Airway smooth muscle | OSU-HDAC-44 | Li et al., 2014 | |

| IPF fibroblasts | LBH589 and SAHA | Coward et al., 2009 | |

| IPF fibroblasts | Trichostatin A | Huang et al., 2013 | |

| IPF, bleomycin mouse model | SAHA | Sanders et al., 2014 | |

| IPF fibroblasts | SAHA | Zhang et al., 2013 | |

| HDAC upregulation | COPD, elastase mouse model | Quercetin | Ganesan et al., 2010 |

| COPD | Theophylline | Cosio et al., 2004 | |

| Histone methyltransferase inhibitors | IPF fibroblasts | BIX-01294 and 3-Deazaneplanocin |

Coward et al., 2010 Coward et al., 2014 |

| Bromodomain protein inhibitor | IPF fibroblasts | JQ1 | Filippakopoulos, et al., 2010 |

3.2.3 IPF

In contrast to asthma and COPD, which are predominantly characterized by increases in “permissive” histone post-translational modifications, IPF is characterized by increases in “restrictive” histone post-translational modifications that result in reduced anti-fibrotic and reduced pro-apoptotic gene expression. Reduced expression of COX-2 in IPF may be the result of elevated H3K9 and H3K27 trimethylation as well as reduced H3 and H4 pan-acetylation at the COX-2 promoter (Coward et al., 2009; Coward et al., 2014). Elevated H3K9 and H3K27 trimethylation correlated with elevated binding of G9A and EZH2, respectively, at the COX-2 promoter. Reduced H3 and H4 pan-acetylation correlated with reduced binding of HATs (CBP, p300 and PCAF), and increased binding of transcription-inhibitory complexes CoREST, NCoR and mSin3a. There was also reduced binding of heterochromatin-associated proteins (HP1, PRC1, MECP2) at the COX-2 promoter (Coward et al., 2009). Expression of the antiinflammatory cytokine CXCL10 is reduced in IPF, possibly due to elevated H3K9 trimethylation and reduced H3 and H4 pan-acetylation (Coward et al., 2010). Fas expression is also reduced in IPF and has been linked to elevated H3K9 trimethylation and reduced H3 pan-acetylation at the Fas promoter (Huang et al., 2013). Altogether these studies indicate that an imbalance in both histone acetylation and methylation exists in IPF which prevents the transcriptional activation of anti-fibrotic and pro-apoptotic genes. Further studies are needed to determine if these alterations in epigenetic modifications are cause or consequence of IPF. Nonetheless, current studies indicate that epigenetic dysregulation of the expression of these genes permits an exaggerated repair response leading to fibrosis.

Inhibitors targeting HDACs or histone methyltransferases responsible for “restrictive” histone acetylation and methylation patterns should correct the “restrictive” imbalance in IPF. This prediction was borne out by pre-clinical evidence demonstrating efficacy of HDAC inhibitors. In fibroblasts from patients with IPF, treatment with HDAC inhibitors LBH589 and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) elevated the expression of COX-2 to levels similar to those observed in control cells (Coward et al., 2009). Trichostatin-A treatment of human IPF fibroblasts restored Fas expression to levels similar to those observed in control cells thereby increasing their ability to undergo apoptosis (Huang et al., 2013). Trichostatin A is not clinically useful but is a very useful broad-spectrum HDAC inhibitor for in vitro studies (Rodríguez-Paredes & Esteller, 2011). SAHA (Vorinostat) is a more promising candidate because it is currently approved for treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (Slingerland et al., 2014). SAHA treatment of bleomycin-treated mice reduced lung fibrosis, collagen III abundance, and improved lung function (Zhang et al., 2013; Sanders et al., 2014). LBH589 (Panobinostat) is another promising HDAC inhibitor in phase 3 clinical trials for therapy of multiple myeloma (San-Miguel et al., 2014). Vorinostat and Panobinostat along with other HDAC inhibitors in earlier stages of development may become effective anti-fibrotic therapy in IPF. In contrast to asthma and COPD, targeting HDACs appears to be the most promising therapeutic approach for IPF.

In addition to promising results with HDAC inhibitors there is some preclinical evidence for beneficial effects of histone methyltransferase inhibitors in IPF. Two inhibitors of the G9a and EZH2 histone methyltransferases (BIX-01294 and 3-Deazaneplanocin) increased COX-2 expression in IPF fibroblasts, which may enhance production of the anti-fibrotic prostanoid, PGE2 (Coward et al., 2014). BIX-01294 treatment of fibroblasts from patients with IPF restored CXCL10 expression to levels similar to those observed in control cells (Coward et al., 2010). Restoration of normal CXCL10 levels may have a beneficial anti-angiogenic effect in IPF. Additional EZH2 inhibitors have been developed including GSK126, EPZ005687, and UNC1999 that may also prove useful for preclinical testing for IPF treatment (Campbell & Tummino, 2014). Whether these newer agents upregulate COX-2 and CXCL10 expression in IPF cell and animal studies remains to be established.

Bromodomain-containing proteins of the histone code “reader” machinery bind acetylated lysine residues on histones and function as transcriptional coactivators (Arrowsmith et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012b). Inhibition of Bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) with JQ1 in bleomycin-treated mice reduced lung fibrosis in vivo (Filippakopoulos et al., 2010). JQ1 also reduced proliferation and migration of IPF fibroblasts (Tang et al., 2013). The effect of blocking BRD4 binding to acetylated histones is consistent with the observations that reduced histone acetylation correlates with reduced COX-2, CXCL10, and Fas expression in IPF fibroblasts (Coward et al., 2010; Coward et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2013). It seems likely that inhibiting BRD4 and other bromodomain proteins will be a useful strategy to rescue the expression of repressed genes in IPF. Additional inhibitors of the BET family bromodomain proteins are currently being developed as epigenetic modifiers for use in cancer chemotherapy (GSK-I-BET151 and PFI-1, GSK I-BET762). These agents might also have efficacy as anti-fibrotic therapy of IPF. Further preclinical trials in the bleomycin mouse model and in human IPF fibroblasts are required to test this idea.

3.3 MicroRNAs

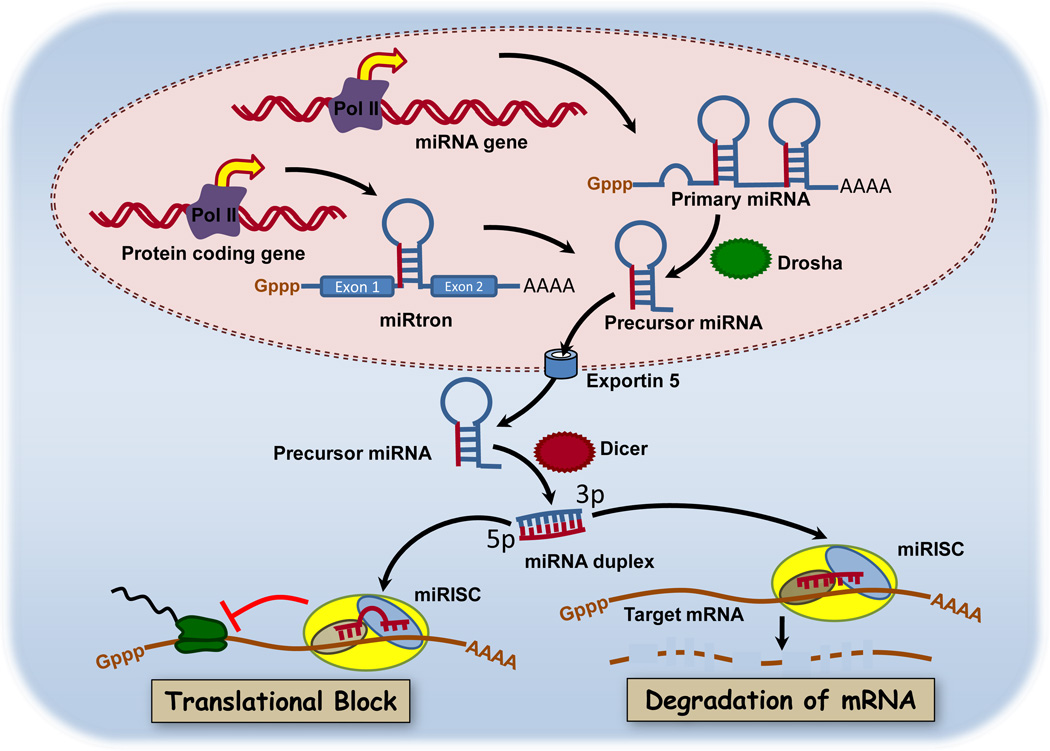

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are 21–23 nucleotide, non-coding single stranded RNAs that negatively regulate post-transcriptional gene expression via mRNA destabilization or/and degradation. miRNA were first described in Caenorhabditis elegans, where lin-4 and let-7 were identified as novel regulators of developmental timing whose loss results in reiteration of cell lineages due to post-transcriptional silencing of lin-14 and lin-28 (Reinhart et al., 2000; Wightman et al., 1993). Both cloning and bioinformatics approaches have been used to identify individual miRNA or polycistronic clusters in introns, exons or intragenic regions (Lagos-Quintana et al., 2001; Rodriguez et al., 2004). Computational analysis estimates that miRNAs regulate >60% of the protein-coding genes in the human genome (Friedman et al., 2009). MiRNAs are generated by transcription of primary RNA transcripts by RNA polymerases II and III. The primary transcripts are processed into stem-loop structures of 70–100 nucleotides by the double-strand-RNA specific RNase Drosha (Figure 3). This pre-miRNA is transported into the cytoplasm via exportin-5, where it is digested by a second RNase Dicer (Chendrimada et al., 2005). This mature miRNA is then bound by a miRNA-associated RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) (Chendrimada et al., 2005). Within this complex, the miRNA can bind to the 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) or in some cases the 5’UTR of target mRNA to either repress translation or induce cleavage (Lytle et al., 2007). For more information, the interested reader is directed to a recent detailed review of miRNA biogenesis and activity (Hausser & Zavolan, 2014).

Figure 3.

MicroRNA biogenesis and mechanisms of gene silencing. The primary RNA transcript of miRNA genes and intronic primary miRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II and processed by Drosha to pre-miRNA. Pre-miRNAs are transported from the nucleus via exportin-5 where they are further processed by Dicer. The mature miRNA is then bound to miRNA-associated RNA-induced silencing complexes (miRISC). Within miRISC, the miRNA can bind to the 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) of target mRNA to either repress translation or induce cleavage. This simplified schematic does not show other known interactions of miRNAs with 5’UTRs or with long noncoding RNAs, both of which are known to regulate expression of some proteins. Reprinted under terms of the Creative Commons license from Joshi et al., 2011.

3.3.1 Normal functions in development and organogenesis of the lung

Normal lung development requires the temporal and spatial regulation of a complex set of genes, including transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1), fibroblast growth factors, hedgehogs and Wnts (Ramasamy et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2005; White et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2012). Lung epithelial cells are initially differentiated from the endoderm to form an epithelial tube surrounded by mesenchymal cells that branch to form bronchioles. The epithelial cells subsequently differentiate into the respiratory epithelium. The first evidence that miRNA played a role in lung development came from the conditional knockout of Dicer in cells that express sonic hedgehog, which include lung epithelial cells (Harris et al., 2006). The loss of Dicer in these cells caused defective airway branching and continued distal epithelial cell proliferation. These changes correlated with abnormal distribution and increased expression of fibroblast growth factor 10 in the mesenchyme, which is thought to act as chemoattractant for epithelial branching.

Indeed, subsequent experiments have highlighted the function of miRNA in epithelial cell differentiation and branching during lung development. Microarray profiling experiments identified 21 miRNA with varying expression patterns during the different phases of rat lung development (Bhaskaran et al., 2009). Of these miRNA, miR-127 expression was highest at the later stages of development, having gradually shifted from mesenchymal cells to epithelial cells. Overexpression of miR-127 in early stages of fetal lung organ culture led to improper bud development. A semi-quantitative PCR-based approach was used to compare differential miRNA expression during mouse and human lung development (Williams et al., 2007). The overall expression profile was similar between mouse and human tissue, which suggested conservation of miRNA expression during lung development, with differences in expression patterns of miR-29a, -29b and -154. MiR-154 is of particular interest because it is found in a maternally imprinted miRNA cluster upregulated in IPF (Milosevic et al., 2012), while miR-29 directly targets the de novo DNMTs, DNMT3A and 3B (Fabbri et al., 2007). Moreover, the expression of miR-29 is decreased by TGF-β1 in human lung fibroblasts and blocks activation of phosphoinositide-3 kinase/Akt signaling (Yang et al., 2013b).

The miR-17~92 cluster was identified as a potential oncogene that is markedly overexpressed in several cancers and occasionally undergoes gene amplification in non-small cell lung carcinomas (Hayashita et al., 2005). This cluster contains miR-17, miR-18a, miR-19a, miR-20a, miR-19b-1, and miR-92-1, which are highly expressed in embryonic stem cells and early stages of lung development, gradually decreasing as development progresses with little expression seen in the adult lung (Lu et al., 2007). Transgenic overexpression of the miR-17~92 cluster in lung epithelial cells caused delayed differentiation and hyperplasia in distal epithelial cells, while targeted deletion resulted in early post-natal mortality due to lung hypoplasia but no specific branching defects (Ventura et al., 2008).

Studies of miRNA expression and function have progressed rapidly in many areas of lung biology. Initial efforts concentrated on profiling differential miRNA expression between healthy and diseased tissues or isolated cells, generating lists of miRNA with limited utility. This was due to the need to identify target mRNAs and to understand the complexity of networks of gene expression that interact in different tissues during disease pathogenesis. Each disease is associated with changes in expression and function of particular miRNAs that have become important therapeutic targets. A summary of the miRNA studied in lung diseases described below is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

MicroRNAs involved in obstructive and restrictive lung diseases

3.3.2 Pulmonary hypertension

The role of miRNA in pulmonary hypertension has been studied largely in rat models of chronic hypoxia and monocrotaline treatment with correlations in human PAH samples. Initial studies identified up- and down-regulation of miRNA expression in both rat models, although significant differences in down-regulation of miR-21 that correlated with human PAH samples were observed only in the monocrotaline-treated animals. (Caruso et al., 2010). Expression profiling experiments in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells from PAH patients and monocrotaline-treated rats identified down-regulation of miR-204 (Courboulin et al., 2011), whose expression was confined to pulmonary arteries with little expression seen in pulmonary endothelial cells, veins or surrounding bronchi. Expression of miR-204 correlated with PAH severity and miR-204 inhibition increased proliferation and resistance to apoptosis. Targets of miR-204 include, among others, SHP2, an upstream activator of Src tyrosine kinase and nuclear factor of activated T cells (Courboulin et al., 2011) and TGF-β1 receptor 2 (Wang et al., 2010). The role of miR-204 in PAH and vascular remodeling events may be mediated by effects of proliferative signaling pathways since loss of miR-204 activates the small GTPase Rac1 to stimulate actin reorganization via Akt/mTOR in cancer cells (Imam et al., 2012). Several miRNA clusters have also been suggested to play a role in PAH. BMPR2 protein expression is reduced in PAH animal models via STAT3-mediated expression of the miR-17~92 cluster, which directly targets BMPR2 (Brock et al., 2009). The miR-143~145 cluster, which plays a key role in smooth muscle cell phenotype, has also been implicated in PAH. MiR-145-5p is elevated in PAH patients, which correlates with increased miR-145-5p expression in the hypoxic mouse model of PH (Caruso et al., 2010). In contrast, inhibition or knockout of miR-145 protects animals from hypoxia-induced PH (Caruso et al., 2012). A thorough analysis of miRNA expression in PAH lesions in human lungs found miR-143 and miR-145 expression was reduced (Bockmeyer et al., 2012), underscoring the contribution of smooth muscle cell phenotype and remodeling in PAH progression.

3.3.3 Asthma

MiRNAs have been implicated in all key features of asthma including proliferation, migration, inflammation and hyper-contractility in animal models and isolated human cells. Evidence linking miRNAs to the development and pathogenesis of asthma are mainly derived from mouse models of asthma. Garbacki and colleagues identified a large panel of miRNAs that were dynamically regulated in acute, intermediate and chronic murine models of asthma (Garbacki et al., 2011). Additional studies by other research groups have highlighted individual miRNAs for their contributions to asthma pathogenesis (see Table 2). It should be noted there are contradictory results concerning contributions of let-7 and miR-21 to asthma pathogenesis (Collison et al., 2011;Kumar et al., 2011;Lu et al., 2009; Polikepahad et al., 2010). Animal studies are supported by profiling studies identifying differentially expressed miRNAs in tissues, cells and exosomes from human subjects with asthma (Jardim et al., 2012; Jude et al., 2012; Levanen et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2012; Nakano et al., 2013; Perry et al., 2014; Qin et al., 2012; Solberg et al., 2012; Suojalehto et al., 2014). The evidence clearly shows that miRNA expression changes in asthma which may cause disease-related alterations in cell phenotypes that contribute to tissue remodeling and inflammation.

Altered expression in microRNAs in samples from patients with asthma have been linked to numerous features of asthma pathogenesis. Reduced expression of miR-140-3p in asthmatic airway smooth muscle was linked to elevated expression of CD38 which may contribute to altered calcium dynamics in asthma (Jude et al., 2010; Jude et al., 2012). MiR-221 expression was observed to be elevated in airway smooth muscle from severe asthmatics and was linked to hyperproliferation and hypersecretion of IL-6 in these cells (Perry et al., 2014). CD4+ T-Cells from patients with asthma exhibit reduced expression of miR-15a and elevated expression of its validated target VEGFA highlighting the possible role for microRNA dysregulation to the increased vascularization observed in asthma (Nakano et al., 2013). Epithelial cells from patients with asthma exhibit an altered miRNA expression profile including reduced expression of miR-203 that correlated with elevated expression of aquaporin-4, a predicted target of miR-203 (Jardim et al., 2012; Solberg et al., 2012). The pro-inflammatory miRNA, miR-155, was also observed to be upregulated in asthmatic human epithelial and airway smooth muscle cells (Jardim et al., 2012; Comer et al. 2014a). MiR-155−/− mice subjected to ovalbumin sensitization and challenge had reduced eosinophilia and mucus hypersecretion along with a reduced Th2 cell numbers and cytokines (Malmhall et al., 2014). In vitro studies of miR-155 in human airway smooth muscle support its role in promoting pro-inflammatory gene expression (Comer et al. 2014a) These examples demonstrate the mechanism by which miRNAs contribute to the pathogenesis of asthma. Potential pathogenic mechanisms include dysregulation of inflammatory protein expression, altered cell signaling proteins and changes in T-cell differentiation patterns. The evidence suggests either rescue or inhibition of select miRNAs may serve as a beneficial treatment for patients with severe asthma who do not respond to current therapies.

A growing body of cell-based evidence and preclinical animal studies focuses interest on therapies that reduce inflammation, airway hyperreactivity, mucus hypersecretion, and airway remodeling. Inhibition of miR-106a, miR-126, miR-145, miR-221, and Let-7 in mouse models of asthma have successfully reduced several of these pathological features of asthma. Inhibition of miR-106a in a mouse model of asthma reduced Th2 cytokine production, reduced airway hyperreactivity, reduced mucin content, and reduced subepithelial collagen (Sharma et al., 2012). Inhibition of miR-126 in a mouse model of asthma reduced airway inflammation, airway hyperresponsiveness, and mucus hypersecretion (Collison et al., 2011). Inhibition of miR-145 alleviated the hallmark features of allergic inflammation such as eosinophilic inflammation, mucus hyper-secretion, Th2 differentiation and airway hyperreactivity (Collison et al., 2011; Mattes et al., 2009). Inhibition of miR-221 reduced airway inflammation in a mouse model (Qin et al., 2012). MiR-221 regulates mast cell activation, which is consistent with reduced inflammation in mice treated with a miR-221 inhibitor (Mayoral et al., 2011).

MiR-25, miR-133a, and miR-146a/b are additional miRNAs that are promising targets for asthma therapy. These miRNAs target contractile proteins and inflammatory proteins, RhoA and immune signaling respectively. Study of miR-25 in human airway smooth muscle cells demonstrated its broad role in regulating contractile, proliferative and inflammatory phenotype through negative regulation of Kruppel like factor-4 (Kuhn et al., 2010; Petty & Singer, 2012). Transgenic smooth-muscle targeted overexpression of miR-25 in mice appears to ameliorate asthmatic changes in lung function in preliminary studies (Copley-Salem et al., 2013). Moreover, miR-25 expression was significantly down-regulated following chronic sensitization of mice with ovalbumin (Garbacki et al., 2011). In the ovalbumin mouse model of asthma miR-133a was also down-regulated resulting in increased expression of RhoA, a target of miR-133a (Chiba et al., 2009). Transfection of human bronchial smooth muscle cells with a miR-133a antagonist upregulated Rho A suggesting endogenous miR-133a normally restrains RhoA expression. The study by Chiba and colleagues highlights the potential for a miR-133a rescue therapy of asthma using miRNA mimics.

In contrast to miR-25 and miR-133a, which are downregulated, miR miR-146a and miR-146b are upregulated in the ovalbumin mouse model of asthma and miR-146a expression in elevated in human airway smooth muscle from patients with asthma (Garbacki et al., 2011; Comer et al. 2014b). MiR-146a/b inhibits innate immune and IL-1 receptor-mediated signaling and the expression of HuR, an RNA binding protein that typically stabilizes pro-inflammatory transcripts (Cheng et al., 2013; Larner-Svensson et al., 2010; Perry et al., 2009; Taganov et al., 2006; Comer et al., 2014b). Upregulation of miR146a/b in the ovalbumin mouse model may reflect a compensatory mechanism to blunt airway inflammation. As a therapeutic approach miR-146a/b mimics would be expected to antagonize the development of allergic airway inflammation. In cultured human airway smooth muscle cells miR-146a was induced by a mixture of IL1-β, TNFα and IFNγ (Comer et al., 2014b) consistent with induction by ovalbumin in the mouse asthma model. A mir-146a mimic reduced expression of HuR, which was associated with downregulation of COX-2 and downregulation of IL1-β expression. Therefore, a miR-146a mimic or strategies to upregulate miR-146a expression should antagonize allergic airway inflammation and provide a novel therapeutic approach based on RNA interference.

3.3.4 COPD

While there are a variety of environmental, genetic and epigenetic factors that contribute to COPD, cigarette smoke is the most important risk factor that correlates with dysregulation of several miRNAs even though only 20% of smokers will eventually develop COPD (Pauwels & Rabe, 2004). The expression of miRNAs are generally downregulated in smokers compared to non-smokers in airway epithelium (De Flora et al., 2012), alveolar macrophages (Graff et al., 2012) and in lung tissue (Ezzie et al., 2012). This down regulation of miRNA expression in smokers may be due to reduced Dicer activity following sumoylation of Dicer (Gross et al., 2014). Thus, as with histone modifications and DNA methylation, cigarette smoke has profound effects on miRNA expression by directly affecting the expression of enzymes that regulate the levels of the epigenetic modifiers. Microarray-based studies have been performed by a number of labs and have identified a large number of differentially expressed miRNAs in primary fibroblasts and lung tissue from patients with COPD (Chatila et al., 2014; Ezzie et al., 2012; Gross et al., 2014; Molina-Pinelo et al., 2014; Sato et al., 2010). In addition studies of BALF cells, sputum, serum, and plasma samples from patients with COPD have identified numerous differentially expressed miRNAs (Akbas et al., 2012; Soeda et al., 2013; Van Pottelberge et al., 2011). Many of the miRNAs implicated in COPD have also been associated with various cancers, and COPD is associated with increased risk of squamous cell non-small cell lung carcinoma (Papi et al., 2004). To determine whether miRNA expression was differentially expressed between lung cancer and COPD patients, microarray experiments were performed from whole blood RNA (Leidinger et al., 2011) and plasma (Sanfiorenzo et al., 2013). Both studies identified a subset of miRNA that discriminated COPD from lung cancer, including miRNAs 26a, 641, 383, 940, 662, 92a, 369-5p, and 636 (Leidinger et al., 2011) and miRNAs 20a, 24, 25, 152, 145, 199a (Sanfiorenzo et al., 2013). These results suggest patterns of miRNA expression might be developed as clinical biomarkers to assess cancer risk and progression.

The miRNAs dysregulated in COPD modulate expression of genes that contribute to pathogenesis of the disease. Decreased expression of let-7c and miR-126a was observed in sputum of COPD patients who continued to smoke compared to smokers without COPD. Reduced let-7c correlated with increased tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNFR2) (Van Pottelberge et al., 2011), which is increased in the sputum of COPD patients. Increased TNFR2 indicates continued inflammation even when the patients stop smoking (Vernooy et al., 2002). The expression of miR-101 is elevated in the lungs of patients with COPD and in mice treated with cigarette smoke. Elevated miR-101 expression correlates with reduced expression of CFTR in COPD which may contribute to mucus accumulation, chronic infection, and inflammation (Hassan et al., 2014). A microarray analysis of cytokine-stimulated fibroblasts from COPD patients identified downregulation of miR146a. Decreased miR-146a was shown to upregulate COX-2 expression which increases prostaglandin E2 and increases disease severity (Sato et al., 2010).

Cellular heterogeneity in expression patterns is a complicating factor in establishing the role of a particular miRNA in COPD pathology. Expression of miR-199a-5p has been observed to be elevated in some studies and reduced in different cell types in patients with COPD (Chatila et al., 2014; Hassan et al., 2014; Mizuno et al., 2012). Previously, Lindsay and colleagues observed cell specific miRNA profiles in human lung samples indicating that in disease different cell types can exhibit differential expression of a particular miRNA (Williams et al., 2007). Reduced expression of miR-199a-5p in COPD was linked to miR-199a-2 promoter CpG hypermethylation in monocytes from patients with COPD and may contribute to enhancement of the unfolded protein response in patients with α1-antitrypsin deficiency (Chatila et al., 2014). Furthermore, reduced expression of miR-199a-5p was observed in regulatory T cells from patients with COPD and transcriptome analysis revealed that a number of miR-199a-5p targets are expressed in regulatory T cells including members of the TGFβ superfamily (Chatila et al., 2014). Reduced miR-199a-5p expression in regulatory T cells in COPD may enhance regulatory T cell function resulting in abnormal bias towards Th1 immune responses (Kalathil et al., 2014). In contrast, elevated miR-199a-5p expression was observed in lung tissue from patients with COPD that correlated with reduced expression of hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF1α). HIF1α is a validated target of miR-199a-5p that is reduced in COPD (Mizuno et al., 2012; Yasuo et al., 2011). Reduced HIF1α is hypothesized to impair the normal “lung structure maintenance program” (Yasuo et al., 2011). Mizuno and colleagues later observed elevated miR-34a expression in COPD, and in vitro experiments demonstrated that miR-34a controls expression of miR-199a-5p (Mizuno et al., 2012). Thus, in COPD, altered expression of miRNAs contributes to changes in both protein coding and miRNA coding genes that each contribute to pathogenesis. These dysregulated miRNAs appear to be ideal treatment targets in COPD although additional studies are warranted to help determine whether observed differences in miRNAs are a cause or consequence of COPD.

3.3.5 IPF

Studies of miRNA expression in IPF have estimated that 10% of all miRNA are dysregulated in IPF lungs (Pandit et al., 2010), including let-7d, miR-15b, miR-26a/b and miR-29, as well as miR-17~92 cluster, miR-29a/b/c, and miR-30c. An additional study identified a large number of differential expressed miRNAs including 43 upregulated miRNAs in samples from patients with IPF (Milosevic et al., 2012). MicroRNA profiling in bleomycin-treated mice (Xie et al., 2011) support human profiling studies and suggest temporal differences in miRNA expression may exist during the development and progression of IPF. Furthermore, differential miRNA expression was observed in lung biopsies from patients with rapidly progressing IPF when compared to slow progressing IPF (Oak et al., 2011). Interestingly, the expression of argonaute 1 mRNA was reduced in both slow and rapidly progressing IPF lung biopsies. The expression of arogonaute 2 mRNA was elevated in rapidly progressing IPF lung biopsies but argonaute 2 immunoreactivity was lowest in rapidly progressing IPF. Oak and colleagues were unable to detect argonaute 1 immunoreactivity reliably. In cultured IPF fibroblasts, cells from rapidly progressing IPF had reduced expression of DICER1 and argonaute 1 compared to slow progressing IPF and control fibroblasts. Reduced DICER1 expression is hypothesized to reduce miRNA biogenesis while reduced Argonaute expression is hypothesized to reduce both miRNA biogenesis and miRNA-mediated silencing of gene expression (Diederichs et al. 2007) Taken together, these studies indicate that differential miRNA expression occurs in IPF in human subjects and alterations in miRNA biogenesis and function may also contribute to rapidly progressing IPF.

The function of numerous miRNAs that are elevated in IPF have been investigated to establish relevance to disease pathogenesis. Many miRNAs associated with IPF regulate TGF-β1 expression or function, inflammation, actin expression or cell signaling pathways, all of which contribute to fibrosis. MiR-155 expression is also elevated in IPF in human subjects and in the lungs of bleomycin-treated mice (Pandit et al., 2010; Pottier et al., 2009). Interestingly, miR-155 is a negative regulator of TGF-β1 signaling in macrophages by silencing Smad2 (Louafi et al., 2010), but it promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in response to TGF-β1 by silencing RhoA in epithelial cells (Kong et al., 2008). MiR-155 also repressed the expression of keratinocyte growth factor in lung fibroblasts (Pottier et al., 2009) which may promote fibrosis. These results highlight the potential of a miR-155 inhibitor as an anti-fibrotic therapy in IPF.

The functions of several miRNA that are elevated in IPF converge on TGF-β1 signaling. MiR-154 is an example of an miRNA upregulated in IPF and induced by TGF-β1 in human lung fibroblasts (Milosevic et al., 2012). MiR-154 induced proliferation and migration of fibroblasts which was mediated by the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway was shown previously to be upregulated in lungs biopsies obtained from patients with IPF (Königshoff et al., 2008). MiR-21 is another well-studied miRNA that is upregulated in lung fibroblasts of IPF patients (Liu et al., 2010), and is induced by TGF-β1 in primary fibroblasts. Upregulation of alpha smooth muscle actin by miR-145 is another example of a miRNA regulating profibrotic gene expression. MiR-145 is elevated in the lungs of patients with IPF (Yang et al., 2013a), and it promotes fibroblast to myofibroblast transition in response to TGF-β1 treatment. MiR-145 expression is necessary for bleomycin-induced fibrosis because miR-145 −/− mice do not develop pulmonary fibrosis in response to bleomycin (Yang et al., 2013a). The profibrotic mechanism of miR-145 is due in part to upregulation of smooth muscle actin expression by repression of Kruppel-like factor 4, which is a negative regulator of serum response factor-dependent gene expression.

Elements of TGF-β signaling pathways are also influenced by reduced expression of miRNAs, which results in upregulation of target transcripts that drive fibrosis. For example, Let-7d expression is decreased in alveolar epithelium of IPF lungs, correlating with increased high mobility group AT-hook 2 (HMGA2), which is a mediator of TGF-β1 induction of EMT (Pandit et al., 2010; Thuault et al., 2006). Inhibition of Let-7d in mice yielded a lung pathology similar to IPF including alveolar septal thickening, increased collagen 1 expression, increased HMGA2 expression, increased lung collagen deposition, decreased epithelial cells markers (CDH1 and TJP1), and increased numbers of smooth muscle α-actin positive cells. Promotion of fibrosis by let-7d repression suggests a rescue therapy might be beneficial in IPF. Similar arguments can be made for a number of other profibrotic miRNAs downregulated in IPF. MiR-26a expression is reduced in lung tissue from patients with IPF correlating with increased expression of connective tissue growth factor and enhanced collagen production (Liang et al., 2014). MiR-29 expression is lower in patients with IPF and in bleomycin-treated mice (Cushing et al., 2011; Pandit et al., 2010). Reduced miR-29 correlated with increased collagen and extracellular matrix gene expression (Cushing et al., 2011). The expression of miR-200a and -200c are also reduced in IPF lungs (Yang et al., 2012). Members of the miR-200 family inhibit TGF-β1-mediated EMT transitions and reduce smooth muscle α-actin and fibronectin expression (Yang et al., 2012). There is also evidence that miR-326 negatively regulates TGF-β1 expression in IPF and the bleomycin mouse model (Das et al., 2014). Normalizing TGF-β1 signaling in IPF may be possible using a rescue strategy where one or more the downregulated miRNAs are delivered to the lung.

In addition to miRNA regulation of fibrous structural proteins there is evidence for miRNA control of signaling proteins in fibrosis. MiR-199a is elevated in IPF patients and in bleomycin-treated mice (Lino Cardenas et al., 2013), and it is correlated with reduced caveolin-1 expression. MiR-199a promoted human MRC-5 lung fibroblast proliferation, migration, invasion, and differentiation into myofibroblasts in vitro (Lino Cardenas et al., 2013). Caveolin-1 is a validated target of miR-199a that has been was implicated previously in IPF pathogenesis (Wang et al., 2006).

Correlations of miRNA expression and mechanistic validation studies in IPF and the bleomycin mouse model suggest a profibrotic miRNA gene expression program that involves both upregulation (miRNAs 21, 145, 155, 199a) and downregulation of miRNAs (miRNAs Let7d, 17~92, 26a, 29, 200 family and 326). In all cases target proteins regulated by these miRNAs either directly or indirectly promote fibrosis. In many of the preclinical animal studies rescue and inhibition strategies were effective antifibrotic therapies. Translation of these exciting findings to first in human safety and efficacy trials is the next important step.

3.3.6 Extracellular miRNA and miRNA SNPs: New avenues of exploration

The discovery of extracellular miRNA in biological fluids, including serum, plasma, urine and saliva (Weber et al., 2010) has emerged as a growing area of study in the search for non-invasive diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. These extracellular miRNAs are surprisingly resistant to nuclease digestion (Szafranska et al., 2008) and concentrated in circulating exosomes (Gallo et al., 2012). Both up- and down-regulated circulating miRNA were isolated from serum of PAH patients (Rhodes et al., 2013; Schlosser et al., 2013). Five circulating miRNA have been identified in the serum of COPD patients with downregulation of miRNAs 20, 28-3p, 34c-5p and 100 and upreglation of miR-7 compared to healthy controls (Akbas et al., 2012). In the serum of IPF patients, levels of miR-21, miR-101-3p and miR-155 correlates with disease progression, suggesting that these miRNA could be promising biomarkers for IPF prognosis (Li et al., 2014). A report of circulating miRNA relevant to an asthmatic phenotype identified 100 exosomal miRNAs in the serum of mice exposed to HDM extract (Shuichiro et al., 2014). While serum is a convenient, accessible source of miRNA-containing exosomes, the identification of circulating miRNA in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), saliva or sputum could also provide useful information about localized expression of miRNA more relevant to lung diseases. Significant differences in exosomal miRNA isolated from BAL fluid of asthmatic patients identified let-7 and miR-200 family members that could be used to predict asthma severity (Levanen et al., 2013). These intriguing early discovery studies need to be confirmed in new validation cohorts in prospective longitudinal studies. Significant new data are needed to determine specificity and sensitivity of patterns of miRNAs in blood, BALF or sputum before they can be used as prognostic indicators.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are emerging as another important area of study in lung disease. SNPs occur at a frequency of 1200–1500 base pairs in the human genome (Sherry et al., 1999). When they occur in miRNA transcripts, they could alter expression, processing or binding to target mRNA. SNPs in the 3’UTRs of target genes could affect mRNA stability, polyadenylation or regulatory interactions with RNA-binding proteins. SNPs in miRNA target sites, known as miR-SNPs, could lead to heritable defects in miRNA targeting that modifies gene expression. A systemic meta-analysis of genetic association studies determined that polymorphisms of miRNA-196a2 rs11614913 and the basic-loop-helix transcription factor MYCL1 rs3134615 could be potential biomarkers of lung cancer (Chen et al., 2013). Moreover, a SNP identified in the 3’UTR of KRAS altered targeting by let-7 and was significantly associated with increased lung cancer risk (Chin et al., 2008). In asthma, a SNP in the 3’UTR of the asthma susceptibility gene HLA-G affects targeting by the miR-148/152 family (Tan et al., 2007). MiR-SNPs identified in the pre-miRNA of miR-146a and miR-149 were significantly associated with a lower risk of asthma in a Chinese population and among a group of Mexican pediatric patients (Jimenez-Morales et al., 2012). In COPD patients, SNPs in alleles for miR-196a and miR-499 were associated with decreased risk of the disease (Li et al., 2011). Understanding polymorphisms in miRNAs and their target transcripts will become highly relevant as miRNA-based therapies evolve. Designing optimal miRNA antagonists and mimics may eventually require a deep understanding of SNPs in an individual’s protein coding genes as well as SNPs in the noncoding RNA loci being targeted.

3.4 Long noncoding RNAs

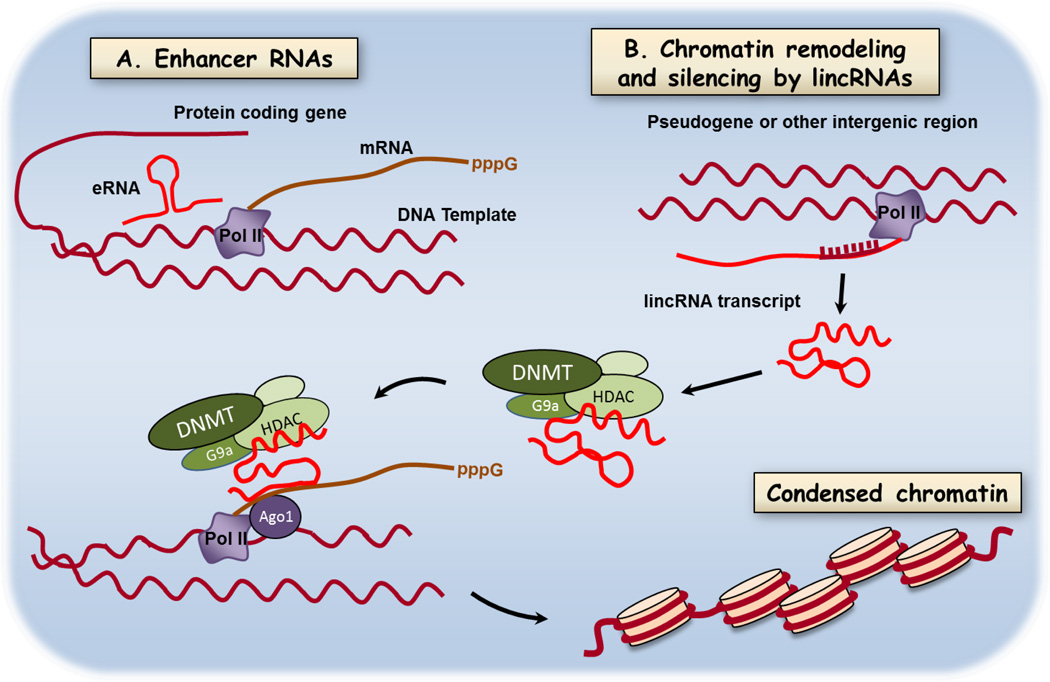

Long noncoding RNAs (lnc RNA) are RNAs >200nt transcribed from genomic sequences that are not translated into proteins. They are transcribed from enhancer sequences of protein coding genes (eRNAs, Natoli & Andrau, 2012), from intergenic, multiexomic regions (lincRNAs, Ulitsky & Bartel, 2013), and from noncoding strands of protein-coding genes (naturally occurring antisense transcripts, NAT, Cabili et al., 2011; Rinn & Chang, 2012) (see Figure 4). We will use the term long noncoding RNAs, abbreviated lncRNA to refer to the set of all noncoding RNAs > 200 nt. Long noncoding RNAs are emerging as versatile adapter molecules that bind to proteins, to DNA, and in some cases other RNAs. Intense investigation into lncRNA function has revealed multiple effects on gene expression that are often tissue-restricted. Functions of lncRNAs include regulation of transcription by controlling gene looping (Natoli & Andrau, 2012; Rinn et al., 2007), regulation of mRNA splicing (Zong et al., 2011), regulation of mRNA decay (Gong & Maquat, 2011; Kretz et al., 2013) and organizing chromosomes into gene neighborhoods (Hacisuleyman et al., 2014) (Figure 4). HOTAIR is a well-studied example of a lncRNA that binds components of the chromatin remodeling machinery. HOTAIR is a lncRNA in the HOXC locus (Rinn et al., 2007) that silences expression of HOXD genes during differentiation of myogenic progenitors (Tsumagari et al., 2013). It acts as a scaffold for assembly of the histone modifying enzyme complexes described above in section 3.2 and shown schematically in Figure 4. Altered histone modifications influence transcription of HOXD genes. In the lung HOXA and HOXB family members are important during development and in disease (Golpon et al., 2001). In non-small cell lung cancer HOTAIR regulates expression of HOXA5 and high expression of HOTAIR is a negative prognostic indicator (Liu et al., 2013). We describe below the rapid progress being made in studies of other lncRNAs in lung development and in nonneoplastic lung diseases.

Figure 4.

Mechanisms of regulation of gene expression by long noncoding RNAs. Long nonprotein coding RNAs are transcribed from a variety of genomic loci including enhancer sequences (eRNAs), intergenic, multiexomic sequences (lincRNAs), and noncoding strands of protein-coding genes (naturally occurring antisense transcripts. Shown here are a few of the rapidly emerging mechanisms by which lncRNAs modify gene expression and protein abundance. A. Binding of RNAs coded in enhancer regions to effect DNA looping and B. lncRNA serving as an adapter molecule in chromatin remodeling by DNA methylation and histone modifications. A salient feature of lncRNAs is the potential bind chromatin remodeling proteins, DNA, and in some cases other RNAs. Two important functions not shown are regulation of mRNA splicing and regulating mRNA decay. Targeting new oligonucleotide drugs to lncRNA function will require identification of key lncRNAs in lung diseases and defining the contribution these mechanisms to pathology.

3.4.1 Normal functions in development and organogenesis of the lung

Several hundred lncRNAs were identified in the developing mouse lung by sequencing polyadenylated RNAs in embryonic (E12.5) and adult lung tissue (Herriges et al., 2014). Analysis of the genomic structure of lncRNA loci in mouse lung revealed many loci contain binding sites for serum response factor, Fox and SP1 transcription factors, which collectively regulate early stages of lung mesoderm and endoderm development. A loss of function strategy was used to validate the role of several lncRNAs at loci close to transcription factors that regulate embryonic lung development. Two of these candidates, NANCI and LL34, were found to regulate expression of hundreds of genes in mouse airway epithelial cell culture. Some of the regulated genes control key steps in differentiation and development of airway epithelial cells. Similar studies in lncRNAs in lung diseases are underway and new data relevant to disease mechanisms and novel targets of therapy are eagerly anticipated.

The mechanistic studies of lncRNAs in mouse lung are highly relevant to the role of lncRNA deletions in the rare lethal neonatal lung disorder, capillary dysplasia and misalignment of pulmonary veins (ACD/MPV) (Szafranski et al., 2013). Lung tissues from subjects with ACD/MPV contain a “shared deletion region” which includes loci for several lncRNAs. The authors speculated that loss of chromatin looping function mediated by lncRNAs in the shared deletion region might underlie loss of forkhead box F1 expression leading to some aspects of the vascular pathology of ACD/MPV. The study illustrates the principle that loss of function of lncRNA can have profound effects on lung structure which includes pathological effects on neovascularization in this example. It remains to be seen whether similar changes in lncRNA expression and function occur in pulmonary vascular remodeling in PAH or bronchial vascular remodeling in asthma (Avdalovic, 2014).

Some of the nonvascular remodeling events in asthma, COPD and IPF might also be due to changes in lncRNA expression or function. Important lncRNA targets in lung diseases will emerge rapidly in the next few years, and much work remains to define relevant lncRNAs in various lung cell types. A good example of early stage lncRNA discovery is a recent survey of noncoding RNAs in human airway smooth muscle (Perry et al., 2014). Several lncRNAs were described that the authors suggest might act as sponges for microRNAs that regulate smooth muscle differentiation (Perry et al., 2014). They also observed expression of a noncoding RNA from the PVT-1 locus. PVT-1 lncRNA is upregulated in many cancers where it is known to interact with c-myc and contribute to dysregulated cell proliferation through an unknown mechanism. Further studies on the lncRNAs expressed in lung cells and the functions of those lncRNAs must be defined to identify valid targets for novel therapy of lung diseases.

3.4.2 Experimental and therapeutic potential of lncRNA inhibitors

The earliest information on lncRNAs in lung cancers suggested they might be drug targets. Changes in expression of lncRNAs is associated with several lung cancers (Enfield et al., 2012; Ji et al., 2003) and lncRNAs have been nominated as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in several cancers. However, the functions of lncRNAs in disease pathogenesis are still being defined. Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT-1) was one of the first lncRNAs described in non-small cell lung cancer (Ji et al., 2003). It is one of the few lncRNAs for which there is mechanistic information. MALAT-1 is associated with greater potential for metastasis, and elevated MALAT-1 was suggested to be a prognostic indicator of lower survival rate (Schmidt et al., 2011). MALAT-1 is necessary for metastasis of lung cancer cells (Gutschner et al., 2013; Ji et al., 2003; Tano et al., 2010). It regulates more than 20 genes required for cancer cell metastasis (Gutschner et al., 2013). Using both in vitro and in vivo antisense knockdown strategies and zinc finger nuclease-mediated gene silencing Gutschner et al. (2013) conducted a preclinical efficacy trial in A549 cells and a xenograft lung cancer model. This important study showed that reducing MALAT-1 expression could prevent metastasis of lung cancer.

In a prior study of HUVECs and Hela cells MALAT-1 was shown to regulate RNA splicing (Lin et al., 2011). Although this activity was not associated with metastatic potential (Gutschner et al., 2013), it suggests the function of MALAT-1 may be relevant to pulmonary hypertension, which is a disease of endothelial dysfunction. The notion that MALAT-1 is relevant to pulmonary hypertension was later explored in a study of lncRNAs in vascular endothelial cells (Michalik et al., 2014). MALAT-1 was increased by hypoxia and inhibited proliferation while promoting endothelial cell migration (Michalik et al., 2014). These findings strongly support the role of MALAT-1 in regulating genes important in signaling, cell communication and cell adhesion, which are processes dysregulated in pulmonary hypertension. Whether MALAT-1 influences other structural cells in the lung, such as airway smooth muscle and lung fibroblasts is unknown. If so, MALAT-1 might be a suitable target for reducing or reversing airway and parenchymal remodeling in both pulmonary vascular and obstructive lung diseases.

The BIC gene transcript is another noncoding RNA that has high potential for influencing lung remodeling and inflammation in asthma, COPD and PAH. After posttranscriptional processing the BIC transcript yields miR-155. MiR-155 is a widely expressed multifunctional miRNA that influences T cell differentiation by modulating development of Th2, Th17 and regulatory T cell subtypes (Seddiki et al., 2013). The effects are complex and can vary with the disease model, but there is evidence miR-155 is necessary for chronic inflammatory responses (Malmhall et al., 2014; Seddiki et al., 2013). Many protein targets of miR-155 have been identified in immune cells including Pu.1, SHIP1, SOCS1 and c-Maf (Lu et al., 2009; Rodriguez et al., 2007). In cultured human airway smooth muscle cells miR-155 expression is enhanced in cells from asthmatics, and a miR-155 mimic enhances COX-2 expression and PGE2 synthesis (Comer et al., 2014a). In an important animal study miR-155 knockout reduced airway inflammation, reduced airway hyperreactivity and reduced Th2 cytokine expression in ovalbumin-sensitized mice (Malmhall et al., 2014). These intriguing results strongly suggest the BIC lncRNA and its miRNA end product, miR-155, are potential targets for novel anti-inflammatory and antiremodeling therapy.