Abstract

Background

Left ventricular (LV) diameter is routinely measured on the echocardiogram but has not been jointly evaluated with the ejection fraction (EF) for risk stratification of sudden cardiac death (SCD).

Methods and Results

From a large ongoing community‐based study of SCD (The Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study; population ≈1 million), SCD cases were compared with geographic controls. LVEF and LV diameter, measured using the LV internal dimension in diastole (categorized as normal, mild, moderate, or severe dilatation using American Society of Echocardiography definitions) were assessed from echocardiograms prior but unrelated to the SCD event. Cases (n=418; 69.5±13.8 years), compared with controls (n=329; 67.7±11.9 years), more commonly had severe LV dysfunction (EF ≤35%; 30.5% versus 18.8%; P<0.01) and larger LV diameter (52.2±10.5 mm versus 49.7±7.9 mm; P<0.01). Moderate or severe LV dilatation (16.3% versus 8.2%; P=0.001) and severe LV dilatation (8.1% versus 2.1%; P<0.001) were significantly more frequent in cases. In multivariable analysis, severe LV dilatation was an independent predictor of SCD (odds ratio 2.5 [95% CI 1.03 to 5.9]; P=0.04). In addition, subjects with both EF ≤35% and severe LV dilatation had higher odds for SCD compared with those with low EF only (odds ratio 3.8 [95% CI 1.5 to 10.2] for both versus 1.7 [95% CI 1.2 to 2.5] for low EF only), suggesting that severe LV dilatation additively increased SCD risk.

Conclusion

LV diameter may contribute to risk stratification for SCD independent of the LVEF. This readily available echocardiographic measure warrants further prospective evaluation.

Keywords: ejection fraction, LV diameter, risk stratification, sudden cardiac death

Introduction

Heart disease continues to be a leading cause of mortality in the United States, with sudden cardiac death (SCD) representing about 50% of this burden. The average US national survival rate from out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest remains <5%.1 Large, multicenter trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) in reducing mortality due to sudden death,2–3 and the primary prevention ICD is currently recommended for most patients with left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) of ≤35%. However, it has been established that subjects with low EF comprise a minority of the cases of SCD in the general population.4–5 Furthermore, not all people with low EF are equally at risk of SCD, as reflected by the relatively high number needed to treat in the ICD trials and by current real‐world experience3,6 Also, since ICD therapy is not without risk,7 there is an urgent need to optimize this treatment modality to maximize benefit and minimize harm. In this context, it is important to develop clinically meaningful markers that can help us address the heterogeneity of risk within the population with left ventricular (LV) dysfunction.

The LV diameter is a measure that can be easily obtained during echocardiography at the time of LVEF measurement. Previous studies have established the importance of LV size with regard to cardiac mortality. In the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) registry, increased LV end‐systolic diameter was associated with cardiovascular death.8 Similarly, an analysis from the MADIT‐CRT trial showed a graded reduction in risk of death or heart failure with decreasing LV diastolic volumes.9 Some studies in selected populations have suggested that LV diameter could be useful in SCD risk assessment10–11; however, there is a lack of studies evaluating the role of LV diameter in SCD in the general population, especially when considered along with LVEF. Consequently, we evaluated whether this simple index adds to the LV EF in the context of estimating SCD risk.

Methods

The Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study is a prospective study of out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in the Portland, Oregon, metropolitan area (population ≈1 million), ongoing since 2002. Cases of sudden cardiac arrest were identified using reports from first responders, local hospitals, or the county medical examiner's office. SCD was defined as an unexpected pulseless condition occurring within 1 hour of a witnessed collapse or within 24 hours of the subject last being seen in a usual state of health if unwitnessed. Noncardiac etiologies of SCD such as trauma or drug overdose were excluded, and SCD was diagnosed based on detailed analysis of available records, using a process of adjudication by 3 physicians. Earlier studies have reported that at least 80% of SCD cases will have associated significant coronary artery disease (CAD), even in the absence of prior clinically documented CAD.12 Therefore, the control group was selected to consist predominantly of subjects with CAD in an effort to identify risk factors that are specific to SCD and not merely reflective of CAD risk. Controls were recruited from the same geographic location to constitute a mix of subjects with stable and nonstable CAD and a smaller group with no prior documented CAD. CAD was defined as ≥50% stenosis of a major coronary artery or history of myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, or percutaneous coronary intervention. Control subjects were ascertained between 2002 and 2011 from multiple sources that included (1) individuals who called 911 and received ambulance transport for symptoms of acute ischemia; (2) those who visited the cardiology clinic or who had angiography (with ≥50% stenosis noted on a coronary artery) at one of the participating hospitals; and (3) members of the region's Kaiser Permanente health maintenance organization (HMO; enrolled 2009 to the present), half of whom had prior documented CAD and half of whom did not. Control subjects were enrolled if they provided consent and had no history of ventricular arrhythmias. Detailed demographic and clinical information was obtained for all cases and controls. Only adults (aged ≥18 years) with relevant echocardiographic information available were included in the present analysis; therefore, all subjects in the present study had an echocardiogram. No other specific matching was performed while selecting controls.

Echocardiographic Information

Echocardiograms for both cases and controls were obtained from existing hospital records. Echocardiograms performed prior (but unrelated) to the SCD event were used; if >1 echocardiogram was available, the test closest to the SCD event was used. The LVEF and LV internal dimension in diastole (LVIDD), in millimeters were obtained from the same echocardiogram. EF was calculated using Simpson's method, and the LVIDD was obtained using the standard M mode. LV size index was calculated as the LVIDD normalized for body surface area. Severe LV dysfunction was defined as EF ≤35%. The American Society of Echocardiography criteria were used to categorize subjects based on LVIDD.13 These criteria classify the LV size as normal (men: 42 to 59 mm; women: 39 to 53 mm), mildly dilated (men: 60 to 63 mm; women: 54 to 57 mm), moderately dilated (men: 64 to 68 mm; women: 58 to 61 mm), or severely dilated (men: ≥69 mm; women: ≥62 mm).

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were compared using t tests, and categorical variables were compared using chi‐square tests. Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for association of SCD with LV dilatation and severe LV dysfunction. In addition, dummy variables were created for combination of severe LV dysfunction with different categories of LV size. Odds of SCD associated with these combinations (compared with the rest of the population) were calculated. Logistic regression was used to derive adjusted ORs for SCD associated with severe LV dilatation. Additional models were used to estimate odds for SCD associated with low EF only and presence of both low EF and severe LV dilatation (using a dummy variable) after adjusting for the other covariates considered in the first model. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corporation).

Results

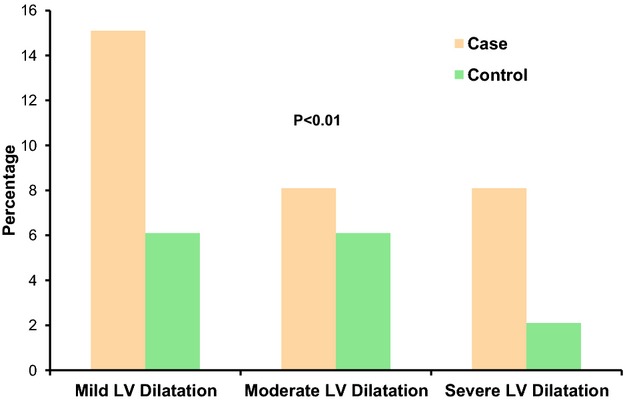

A total of 747 subjects (418 cases and 329 controls) were studied. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics and the echocardiographic parameters of cases and controls. Cases were slightly older than controls (P=0.06) with a greater proportion of black subjects (P≤0.01). There was no significant difference in the mean body mass index, proportion of systemic hypertension, or use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors. Cases were more likely to have LVEF ≤35% (P=0.01) and more likely to have larger LV size compared with controls. The mean LVIDD (52.2±10.5 versus 49.7±7.9 mm; P<0.01) and LVIDD adjusted for body surface area (26.6±5.3 versus 25.4±4.2 mm; P<0.01) was significantly higher in cases. Mild, moderate, or severe LV dilatation was found significantly more often in cases compared with controls (Figure).

Table 1.

Demographic and Echocardiographic Characteristics of Cases and Controls

| Cases (n=418) | Controls (n=329) | P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 69.5±13.8 | 67.7±11.9 | 0.06 |

| Male | 270 (64.6) | 205 (62.3) | 0.52 |

| Black race* | 49 (11.8) | 13 (4.2) | <0.01 |

| Body mass index* | 29.8±9 | 29.9±6.7 | 0.93 |

| Hypertension | 321 (76.8) | 249 (75.7) | 0.72 |

| Smoking* status | |||

| Current | 89 (21.3) | 59 (17.9) | 0.14 |

| Former | 140 (33.5) | 107 (32.5) | |

| Nonsmoker | 97 (23.2) | 67 (20.4) | |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL* | 170.5±46.5 | 173.1±52.4 | 0.55 |

| Use of ACE inhibitors* | 200 (49.3) | 149 (47.9) | 0.72 |

| Mean LVEF, % | 46.9±16.8 | 51.3±14.3 | <0.01 |

| LVEF ≤35%* | 115 (28.0) | 53 (16.4) | <0.01 |

| LVIDD in mm | 52.2±10.5 | 49.7±7.9 | <0.01 |

| LVIDD/BSA, mm/m2 | 26.6±5.3 | 25.4±4.2 | <0.01 |

| Moderately or severely dilated LV* | 68 (16.3) | 27 (8.2) | <0.01 |

| Severely dilated LV* | 34 (8.1) | 7 (2.1) | <0.01 |

ACE indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme; BSA, body surface area; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVIDD, left ventricular internal dimension in diastole.

Using t test for continuous variables and chi‐square test for categorical variables.

Race data available for 416 cases and 312 controls.

Body mass index data available for 380 cases and 324 controls.

Smoking status available for 326 cases and 233 controls.

Cholesterol data available for 245 cases and 263 controls.

ACE inhibitor use information available for 406 cases and 311 controls.

Data available for 410 cases and 324 controls.

Defined as LVIDD ≥58 mm for women and ≥64 mm for men.

Defined as LVIDD ≥62 mm for women and ≥69 mm for men.

Figure 1.

Proportions of cases and controls with different categories of LV dilatation based on magnitude of dilatation. LV indicates left ventricular.

In univariate comparisons, black race, severe LV dysfunction, and LV dilatation were all significant predictors of SCD case status. The presence of either moderate or severe LV dilatation doubled the odds of SCD, whereas considering only severe LV dilatation quadrupled the odds. An EF of ≤35% also doubled the SCD odds. We also assessed the effect of LV dilatation within the group with EF ≤35%. The subgroup with low EF and normal or mildly dilated LV did not have significantly increased odds of SCD when compared with the rest of the population (OR 1.5; 95% CI 1.0 to 2.3; P=0.06). However, combinations of low EF with either moderate or severe LV dilatation (OR 2.6; 95% CI 1.4 to 4.7; P<0.01) or severe LV dilatation alone (OR 4.9; 95% CI 1.9 to 12.7; P<0.01) were associated with progressively greater SCD odds (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unadjusted Odds Ratios for Sudden Cardiac Death

| Parameter | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Black race | 3.0 (1.6 to 5.7) | <0.01 |

| Moderate or severely dilated LV vs normal | 2.1 (1.3 to 3.4) | <0.01 |

| Severely dilated LV vs moderately or mildly dilated or normal | 4.0 (1.7 to 9.3) | <0.01 |

| LVEF ≤35% | 2.0 (1.4 to 2.9) | <0.01 |

| LVEF ≤35% with normal LV size or mild LV dilatation* | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.3) | 0.06 |

| LVEF ≤35% and either moderate or severe LV dilatation* | 2.6 (1.4 to 4.7) | <0.01 |

| LVEF ≤35% and severe LV dilatation* | 4.9 (1.9 to 12.7) | <0.01 |

EF indicates ejection fraction; LV, left ventricle; OR, odds ratio.

Compared with the rest of the study population.

In multivariate analysis, severe LV dilatation was an independent predictor of SCD after adjusting for age, black race, and severe LV dysfunction (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable Odds Ratios for Sudden Cardiac Death*

| Parameter | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02) | 0.02 |

| Black race | 3.06 (1.61 to 5.83) | <0.01 |

| EF ≤35% | 1.57 (1.06 to 2.32) | 0.03 |

| Severe LV dilatation | 2.65 (1.11 to 6.37) | 0.03 |

EF indicates ejection fraction; LV, left ventricle; OR, odds ratio.

Multivariable analysis performed on 715 subjects with complete information on all variables in the model.

In separate multivariate models adjusted for age and black race, the OR for severe LV dysfunction alone was 1.8 (95% CI 1.2 to 2.6; P<0.01), whereas for subjects with both severe LV dysfunction and severe LV dilatation, the OR was 4.0 (95% CI 1.5 to 10.7; P<0.01), showing that presence of severe LV dilatation additively increased the odds for SCD in patients with severe LV dysfunction.

Normal‐EF Versus Low‐EF Subjects

We performed a sub‐analysis comparing LV diameter in cases and controls stratified by normal LVEF (≥50%) versus reduced LVEF (<50%) (Table 4). As shown in the table, significant differences in LV diameter were observed only in the subgroup with reduced EF.

Table 4.

Case Control Comparison of LV Diameter Stratified by Normal Versus Low LVEF

| Case (n=228) | Control (n=214) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF ≥50% (n=442) | |||

| LVIDD, mm | 47.8±8.7 | 47.3±6.5 | 0.5 |

| LVIDD/BSA, mm/m2 | 24.6±4.6 | 24.3±3.7 | 0.4 |

| Moderate or severe LV dilatation | 9 (3.9%) | 4 (1.9%) | 0.2 |

| Severe LV dilatation | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.2 |

| Case (n=181) | Control (n=105) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF <50% (n=286) | |||

| LVIDD, mm | 57.9±9.7 | 54.4±8.2 | <0.01 |

| LVIDD/BSA, mm/m2 | 29.3±5.1 | 27.5±4.3 | <0.01 |

| Moderate or severe LV dilatation | 58 (32%) | 20 (19%) | 0.02 |

| Severe LV dilatation | 16 (9.6%) | 1 (1%) | <0.01 |

BSA indicates body surface area; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVIDD, left ventricular internal dimension in diastole.

Discussion

The findings from this community‐based study suggest that LV size may have additional value beyond LVEF as a risk marker for SCD in the community. Although the role of EF has been studied extensively, the LV diameter obtained routinely along with LVEF has not been considered for potential use in risk stratification. The current findings indicate that we could significantly add to risk stratification by using this simple measure. Low EF clearly increases overall risk of sudden death, but it is not clear why the risk is variable within subjects with low EF. It is possible that LV dilation may explain this to some extent because people with a low EF but normal or only mildly dilated LV did not appear to be at significantly greater risk of SCD in this study; however, presence of moderate or severe LV dilation along with low EF was associated with significantly higher odds of SCD.

It could be argued that subjects with moderate or severe LV dilatation merely represent those with relatively lower EFs among the population with LV dysfunction. Indeed, LVEF and LV dilatation are closely related. However, a potential limitation of EF is significant interobserver variability and limited accuracy, especially when endocardial borders are not well defined in all phases of the cardiac cycle.14 Reports have suggested that such variability in EF could be in the range of 10% or greater.15 Consequently, attempting to subclassify categories of EF within the group with LVEF ≤35% may be subject to error and difficult to apply in actual clinical practice. LV size assessed using M mode may be less prone to error. In addition, although there is no consensus on risk‐stratification based on progressive reduction in EF, categorization using LV diameter may provide a practical alternative for refinement of risk assessment. LVEF is also prone to temporal changes, and the prognostic implications of such changes are not well understood. It would be worthwhile to study whether LV size would provide a more stable, robust measure in this regard. Lee et al, in a group of heart failure patients, determined that LV dilatation was an independent predictor of overall and sudden death.16 In addition, in a subgroup of patients, EF improved but moderate or severe LV dilatation did not change significantly. The authors suggest that LV dilatation is an important risk marker and can be used to guide aggressive therapies.

Earlier studies have shown that most cases of SCD in the community have structurally normal LV.12,17 As is evident from the comparisons of LV diameter stratified by LVEF, significant LV dilatation is unlikely to be found in patients with structurally normal LV. The utility of LV size as a risk marker is likely to help mainly in patients with structural heart disease.

An analysis of patients in a congestive heart failure database revealed that subjects with sudden death had a higher mean LV diastolic diameter. The authors suggested that a combination of brain natriuretic peptide and LV dimensions could be useful for SCD risk assessment.10 Yetman et al, in a follow‐up study of patients with Marfan syndrome, found sudden death to be more frequent in those with a dilated LV.11

The ability of LV size to help further refine EF‐based risk prediction could have important implications for primary prevention of SCD. In a small study of patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and ICDs implanted for primary prevention, the highest rate of appropriate ICD interventions was seen in the group that had both low EF and severely dilated LV.18 ICD shocks have been potentially linked to adverse outcomes,7 and inappropriate shocks have a significant adverse impact on quality of life. According to current guidelines, which are based on EF alone, it is likely that a subgroup of ICD recipients do not derive significant benefit.19 The findings from this study suggest that among those with severe LV dysfunction, subjects with a normal or slightly dilated LV may not be at significant risk for SCD. So far, none of the major ICD trials have considered LV size in determining entry criteria. Among the cardiac resynchronization therapy trials, the CARE‐HF trial used LV end‐diastolic dimension of at least 30 mm (indexed to height) as an inclusion criterion.20 A subsequent analysis showed LV end‐diastolic volume to be a univariate predictor of SCD, whereas randomization to cardiac resynchronization therapy reduced SCD risk.21

How does a dilated LV predispose to sudden death? Fatal arrhythmogenesis in SCD is the end result of a complex interplay of several factors that include an arrhythmogenic substrate and an appropriate trigger. Dilatation of the LV could potentially create a favorable milieu for re‐entrant ventricular arrhythmias. Alterations in parameters of repolarization such as the QT dispersion have also been proposed as a potential mechanism of sudden death in patients with heart failure and a dilated LV.22 Consequently, in addition to risk stratification, LV diameter, also warrants investigation as a therapeutic target.

Limitations

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. Although this evaluation was community based, the present analysis was restricted to those who had an echocardiogram performed. We cannot exclude potential bias with this approach because these subjects are likely to have cardiovascular risk factors or disease. However, this study design provided feasible numbers to address the question of whether LV size adds prognostic information to LVEF. The population studied is clinically relevant group, and we believe that these results hold relevance for a large segment of heart disease patients at risk of SCD; for whom current risk stratification approaches and decision making for primary prevention ICDs are imperfect. The echocardiograms were not read in a standardized manner because they were obtained from existing hospital records from the study region; however, these measurements reflect the real‐world scenario in actual clinical practice. Moreover, LVIDD measurement using M‐mode is a very simple, standardized measurement, making significant interobserver variations unlikely.23 Although multivariable models were performed and suggest that LV size appears to improve risk prediction beyond EF alone, other factors could potentially confound the results. In addition, whether LV size can actually improve risk prediction clinically will need further prospective studies with additional analyses focused on parameters such as discrimination and reclassification aimed at evaluating the performance of LV size as a diagnostic test.

Conclusion

Assessment of LV size could potentially add value to EF in risk prediction for SCD. Further investigation directed toward better understanding of the mechanisms underlying the deleterious effects of LV dilatation and evaluating its utility as a clinical risk marker, may pave the way for incorporation of this measurement into risk‐stratification algorithms for sudden death.

Sources of Funding

Funded in part, by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01HL088416 and HL105170 to Dr Chugh. Dr Chugh holds the Pauline and Harold Price Chair in Cardiac Electrophysiology Research at the Heart Institute, Cedars‐Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the significant contribution of American Medical Response, Portland/Gresham fire departments, and the Oregon State Medical Examiner's office.

References

- 1.Nichol G, Thomas E, Callaway CW, Hedges J, Powell JL, Aufderheide TP, Rea T, Lowe R, Brown T, Dreyer J, Davis D, Idris A, Stiell IResuscitation Outcomes Consortium I. Regional variation in out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. JAMA. 2008; 300:1423-1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Brown MW, Andrews MLMulticenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial III. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:877-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, Domanski M, Troutman C, Anderson J, Johnson G, McNulty SE, Clapp‐Channing N, Davidson‐Ray LD, Fraulo ES, Fishbein DP, Luceri RM, Ip JHSudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial I. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352:225-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stecker EC, Vickers C, Waltz J, Socoteanu C, John BT, Mariani R, McAnulty JH, Gunson K, Jui J, Chugh SS. Population‐based analysis of sudden cardiac death with and without left ventricular systolic dysfunction: two‐year findings from the Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 47:1161-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Vreede‐Swagemakers JJ, Gorgels AP, Dubois‐Arbouw WI, van Ree JW, Daemen MJ, Houben LG, Wellens HJ. Out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in the 1990's: a population‐based study in the Maastricht area on incidence, characteristics and survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997; 30:1500-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moss AJ, Schuger C, Beck CA, Brown MW, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Estes NA, III, Greenberg H, Hall WJ, Huang DT, Kautzner J, Klein H, McNitt S, Olshansky B, Shoda M, Wilber D, Zareba WInvestigators M‐RT. Reduction in inappropriate therapy and mortality through ICD programming. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367:2275-2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poole JE, Johnson GW, Hellkamp AS, Anderson J, Callans DJ, Raitt MH, Reddy RK, Marchlinski FE, Yee R, Guarnieri T, Talajic M, Wilber DJ, Fishbein DP, Packer DL, Mark DB, Lee KL, Bardy GH. Prognostic importance of defibrillator shocks in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:1009-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinones MA, Greenberg BH, Kopelen HA, Koilpillai C, Limacher MC, Shindler DM, Shelton BJ, Weiner DH. Echocardiographic predictors of clinical outcome in patients with left ventricular dysfunction enrolled in the SOLVD registry and trials: significance of left ventricular hypertrophy. Studies of left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000; 35:1237-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon SD, Foster E, Bourgoun M, Shah A, Viloria E, Brown MW, Hall WJ, Pfeffer MA, Moss AJInvestigators M‐C. Effect of cardiac resynchronization therapy on reverse remodeling and relation to outcome: multicenter automatic defibrillator implantation trial: cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circulation. 2010; 122:985-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watanabe J, Shiba N, Shinozaki T, Koseki Y, Karibe A, Komaru T, Miura M, Fukuchi M, Fukahori K, Sakuma M, Kagaya Y, Shirato K. Prognostic value of plasma brain natriuretic peptide combined with left ventricular dimensions in predicting sudden death of patients with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005; 11:50-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yetman AT, Bornemeier RA, McCrindle BW. Long‐term outcome in patients with marfan syndrome: is aortic dissection the only cause of sudden death? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003; 41:329-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adabag AS, Peterson G, Apple FS, Titus J, King R, Luepker RV. Etiology of sudden death in the community: results of anatomical, metabolic, and genetic evaluation. Am Heart J. 2010; 159:33-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJChamber Quantification Writing G, American Society of Echocardiography's G, Standards C, European Association of E. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005; 18:1440-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hundley WG, Kizilbash AM, Afridi I, Franco F, Peshock RM, Grayburn PA. Administration of an intravenous perfluorocarbon contrast agent improves echocardiographic determination of left ventricular volumes and ejection fraction: comparison with cine magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998; 32:1426-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thavendiranathan P, Grant AD, Negishi T, Plana JC, Popovic ZB, Marwick TH. Reproducibility of echocardiographic techniques for sequential assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction and volumes: application to patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 61:77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee TH, Hamilton MA, Stevenson LW, Moriguchi JD, Fonarow GC, Child JS, Laks H, Walden JA. Impact of left ventricular cavity size on survival in advanced heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1993; 72:672-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinhaus DA, Vittinghoff E, Moffatt E, Hart AP, Ursell P, Tseng ZH. Characteristics of sudden arrhythmic death in a diverse, urban community. Am Heart J. 2012; 163:125-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zecchin M, Di Lenarda A, Proclemer A, Faganello G, Facchin D, Petz E, Sinagra G. The role of implantable cardioverter defibrillator for primary vs secondary prevention of sudden death in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Europace. 2004; 6:400-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myerburg RJ. Implantable cardioverter‐defibrillators after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:2245-2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cleland JG, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D, Kappenberger L, Tavazzi LCardiac Resynchronization‐Heart Failure Study I. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352:1539-1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uretsky BF, Thygesen K, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D, Kappenberger L, Tavazzi L, Cleland JG. Predictors of mortality from pump failure and sudden cardiac death in patients with systolic heart failure and left ventricular dyssynchrony: results of the CARE‐HF trial. J Card Fail. 2008; 14:670-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranade V, Molnar J, Khokher T, Agarwal A, Mosnaim A, Somberg JC. Effect of angiotensin‐converting enzyme therapy on QT interval dispersion. Am J Ther. 1999; 6:257-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee CK, Margossian R, Sleeper LA, Canter CE, Chen S, Tani LY, Shirali G, Szwast A, Tierney ES, Campbell MJ, Golding F, Wang Y, Altmann K, Colan SDPediatric Heart Network I. Variability of M‐mode versus two‐dimensional echocardiography measurements in children with dilated cardiomyopathy. Pediatr Cardiol. 2014; 35:658-667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]