Abstract

Background

HIV infection is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in men. Whether HIV is an independent risk factor for CVD in women has not yet been established.

Methods and Results

We analyzed data from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study on 2187 women (32% HIV infected [HIV+]) who were free of CVD at baseline. Participants were followed from their first clinical encounter on or after April 01, 2003 until a CVD event, death, or the last follow‐up date (December 31, 2009). The primary outcome was CVD (acute myocardial infarction [AMI], unstable angina, ischemic stroke, and heart failure). CVD events were defined using clinical data, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes, and/or death certificate data. We used Cox proportional hazards models to assess the association between HIV and incident CVD, adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, lipids, smoking, blood pressure, diabetes, renal disease, obesity, hepatitis C, and substance use/abuse. Median follow‐up time was 6.0 years. Mean age at baseline of HIV+ and HIV uninfected (HIV−) women was 44.0 versus 43.2 years (P<0.05). Median time to CVD event was 3.1 versus 3.7 years (P=0.11). There were 86 incident CVD events (53%, HIV+): AMI, 13%; unstable angina, 8%; ischemic stroke, 22%; and heart failure, 57%. Incident CVD/1000 person‐years was significantly higher among HIV+ (13.5; 95% confidence interval [CI]=10.1, 18.1) than HIV− women (5.3; 95% CI=3.9, 7.3; P<0.001). HIV+ women had an increased risk of CVD, compared to HIV− (hazard ratio=2.8; 95% CI=1.7, 4.6; P<0.001).

Conclusions

HIV is associated with an increased risk of CVD in women.

Keywords: AIDS, CVD risk factors, Women

Introduction

HIV infection has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in women.1–3 Whether this association is driven by HIV‐specific or traditional risk factors remains unclear, given that gender‐stratified assessments of the associations between risk factors and CVD have not been performed consistently.1,3–4 Where separate analyses were done for men and women, important risk factors for CVD, including smoking, hepatitis C status, and alcohol and cocaine use, were not included.2 The inclusion of women diagnosed early in the AIDS epidemic may also confound our ability to understand the impact of earlier analyses on women in the current epidemic given that there are significant differences in the timing of antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation, the antiretroviral medications available, and the side effects experienced with treatment.1–3 Finally, a number of the previous analyses have included population comparators who may differ in important ways, such as race and substance use history, from HIV‐infected women.1–3,5 The inclusion of women who are demographically similar, and from the same healthcare system, is of key importance.

We investigated whether HIV and ART are associated with increased CVD events after adjusting for traditional risk factors and substance use and abuse in a cohort of HIV‐infected and uninfected women veterans.

Methods

Sample

The Veterans Aging Cohort Study‐Virtual Cohort (VACS‐VC) is a prospective, longitudinal, observational cohort. Each HIV‐infected Veteran is matched on age, race/ethnicity, and clinical site to 2 uninfected veterans enrolled in general medicine clinics.6 Data for this cohort are extracted from multiple Veterans Health Administration (VHA) sources, including the immunology case registry, national patient care database, and the VHA electronic medical record health factor data set. Deaths were confirmed using the VHA vital status file, the Social Security Administration death master file, the Beneficiary Identification and Records Locator Subsystem, and the VHA Medical Statistical Analysis Systems inpatient data sets. National Death Index data provided cause of death information. This study was approved by institutional review boards at the University of Pittsburgh, Yale University, and the VA Connecticut Healthcare System.

Our analysis was restricted to women. Baseline was defined as the first clinical encounter on or after April 1, 2003. All participants were followed from their baseline date to a CVD event, death, or the last follow‐up date before December 31, 2009.

As reported in an earlier study, VHA data were merged with data from Medicare, Medicaid, and the Ischemic Heart Disease‐Quality Enhancement Research Initiative.7 We excluded participants with prevalent CVD as identified by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) codes for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), stable or unstable angina, cardiovascular revascularization, stroke or transient ischemic attack, peripheral vascular disease, or heart failure (HF) on or before their baseline date (n=66). After these exclusions, our final sample included 2187 women veterans (32% HIV infected). Those women excluded for prevalent CVD were significantly older than those without (47.3±7.8 vs. 43.8±7.7 years, P<0.001, respectively), but did not differ by race (black 65.9%, white 26.1% among those with prevalent CVD, and black 60.0%, white 30.2% in those without; P=0.59).

Independent Variable

We identified HIV infection by the presence of at least 2 outpatient or 1 inpatient ICD‐9‐CM codes for HIV and confirmation in the VHA immunology case registry.6

Dependent Variables

Our primary outcome was total CVD defined as the presence of AMI, unstable angina, ischemic stroke, or congestive HF.7 Despite the lack of data on etiology of HF (ischemic vs. nonischemic), we elected to include HF in the CVD outcome because our earlier work demonstrates an association between HIV and HF8 and because this approach also maximizes power. All primary outcomes were defined using VHA, Medicare, and death certificate data. For AMI events within the VHA, we used adjudicated outcomes from the VHA External Peer Review Program. To identify those AMI events that occurred outside of the VHA in patients who were not transferred to the VHA, a Medicare 410.xx ICD‐9‐CM code was used. For unstable angina, HF, and ischemic stroke, we used 1 inpatient and/or 2 or more outpatient ICD‐9‐CM codes: unstable angina 411.xx; heart failure 428.xx, 429.3, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, and 425.xx; stroke (inpatient) 433.x1, 434.x1, 436, and (outpatient) 438.xx. These CVD ICD‐9‐CM codes were selected based on earlier validation work within and outside the VHA healthcare system.9,8

Covariates

We selected covariates a priori based on clinical relevance, previous work7 within the VACS‐VC, and data availability. We determined age, sex, and race/ethnicity using administrative data. Hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus, renal disease, and anemia were identified using outpatient and clinical laboratory data collected closest to the baseline date. Serum lipid concentrations (low‐density lipoprotein [LDL], high‐density lipoprotein [HDL], and triglycerides [TGs]) were identified using clinical laboratory data. HMG‐CoA (3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl‐coenzyme A) reductase inhibitor and ART use were identified using pharmacy data. Smoking and body mass index (BMI; weight in kg/height in m2) were identified in health factor data that are collected in a standardized form within the VHA.

HTN was categorized based on use of antihypertensive medication and blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg derived from the average of the 3 routine outpatient clinical measurements closest to the baseline date. Diabetes was diagnosed using a previously validated metric that includes glucose measurements, antidiabetic agent use, and/or at least 1 inpatient and/or 2 or more outpatient ICD‐9‐CM codes for this diagnosis.10 Abnormal serum lipid concentrations were defined as LDL ≥160, HDL <50, and TGs ≥150 mg/dL. The HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitor use was within 180 days of the baseline date. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was defined as a positive hepatitis C virus antibody test result or at least 1 inpatient and/or 2 or more outpatient ICD‐9‐CM codes for this diagnosis. Renal disease was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and was obtained from VA laboratory data. Anemia was defined as hemoglobin <12 g/dL. Current, past, and never smoking and BMI were assessed using documentation from the VHA electronic medical record health factor data set, which contains information collected from clinical reminders that clinicians are required to complete for patients. Previous work demonstrates high agreement between health factor documentation and self‐reported smoking survey data.11 History of cocaine and alcohol abuse or dependence was identified using ICD‐9‐CM codes.12 We collected data on baseline CD4+ T‐cell (CD4) counts and HIV‐1 RNA values. Baseline ART was categorized by drug class and types of regimens documented within 180 days of the baseline enrollment date. Antiretroviral regimens were defined as follows: protease inhibitors (PIs) plus nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs); non‐nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) plus NRTIs;, other; and no ART use. We have previously demonstrated that 96% of HIV‐infected veterans obtain all of their ART medications from the VHA.6 Because the analytic sample was not perfectly matched as a result of the exclusion of individuals with prevalent CVD, we also included variables on which the original cohort was matched (age, race, and ethnicity).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for all variables by HIV status were assessed using 2‐sample t tests or the nonparametric counterparts for continuous variables, and the chi‐square or Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables. We calculated the incidence of total CVD per 1000 person‐years, as well as median age at time of CVD event, stratified by HIV status. We used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to assess whether HIV infection was associated with incident total CVD after adjusting for age and race/ethnicity and then for Framingham risk factors.9,13 In a third model, we adjusted for demographic characteristics, Framingham risk factors, comorbid disease, and substance abuse or dependence. We conducted secondary analyses that compared uninfected women to HIV‐infected women stratified by baseline CD4+ T‐cell count, baseline HIV‐1 RNA level, and baseline ART status. On ART at baseline was defined as on any ART regimen (PI+NRTI, NNRTI+ NRTI, or other ART medications) versus not on any ART at baseline. We also examined the rates of CVD among HIV‐infected veterans who were on ART and not on ART at baseline, compared to uninfected veterans. Missing covariate data were included in the analyses using multiple imputation techniques that generated 5 data sets with complete covariate values to increase the robustness and efficiency of the estimated HR.

Results

After restricting the VACS‐VC sample to women (n=2253) and excluding those with baseline CVD (n=66), our final sample included 2187 women, of whom 710 (32%) were HIV infected. Among the HIV‐infected women, 248 (34.9%) were on ART at baseline (Table 1). An additional 393 women initiated ART within a median of 1.14 years (interquartile range [IQR], 0.28, 3.01) after entry into the cohort.

Table 1.

| Characteristic | Uninfected (N=1477) | HIV Infected (N=710) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline, y | 0.04 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 44.0 (7.7) | 43.2 (7.7) | |

| Median (IQR) | 44.0 (40.0 to 48.0) | 44.0 (39.0 to 48.0) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.57 | ||

| African American | 59.3 | 61.6 | |

| White | 30.9 | 28.7 | |

| Other | 9.8 | 9.7 | |

| Framingham risk score | 0.26 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.1 (3.0) | 3.2 (3.2) | |

| Median (IQR) | 3 (1 to 5) | 3 (1 to 5) | |

| Framingham risk factors, % | |||

| Hypertension | 28.0 | 22.9 | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12.6 | 10.4 | 0.14 |

| Lipids, mg/dL | |||

| LDL cholesterol ≥160 | 12.3 | 8.2 | 0.01 |

| HDL cholesterol <50 | 41.1 | 53.8 | <0.001 |

| TGs ≥150 | 23.4 | 33.6 | <0.001 |

| Smoking, % | <0.001 | ||

| Current | 40.4 | 59.2 | |

| Past | 12.3 | 10.2 | |

| Never | 47.2 | 30.6 | |

| Other risk factors, % | |||

| Current HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitor use | 7.3 | 4.7 | 0.02 |

| HCV infection | 5.7 | 24.4 | <0.001 |

| eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, % | 3.7 | 5.6 | 0.048 |

| Body mass index ≥30, % | 44.5 | 25.3 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin <12 g/dL | 17.3 | 29.7 | <0.001 |

| History of substance use, % | |||

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 5.0 | 13.8 | <0.001 |

| Cocaine abuse/dependence | 3.6 | 13.5 | <0.001 |

| HIV‐specific biomarkers | |||

| CD4 cell count, mm3 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 468 (352) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 420 (212 to 654) | ||

| CD4 count ≤200 cells/mm3, % | 24.2 | ||

| HIV‐RNA, copies/mL | |||

| Mean (SD) | 57 866 (150 888) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 1900 (325 to 30 600) | ||

| HIV‐RNA ≥500 copies/mL, % | 59.7 | ||

| On HAART at baseline, % | 34.9 | ||

| ART regimen at baseline, % | |||

| PI+NRTI | 15.2 | ||

| NNRTI+NRTI | 18.0 | ||

| Other | 5.9 | ||

| No ART use | 60.9 |

ART indicates antiretroviral therapy; BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy (3 or more antiretrovirals); HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; HMG‐CoA, 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl‐coenzyme A; IQR, interquartile range; PI, protease inhibitors; NNRTI, non‐nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; TGs, triglycerides; VACS, Veterans Aging Cohort Study.

P<0.05 for all comparisons by HIV status except race (P=0.57), diabetes (P=0.14), and median Framingham risk score (P=0.30).

All variables had complete data except hypertension (HIV− N=1446; HIV+ N=702), LDL cholesterol (HIV− N=1054; HIV+ N=537), HDL‐cholesterol (HIV− N=1080; HIV+ N=558), TGs (HIV− N=1127; HIV+ N=587), smoking (HIV− N=1388; HIV+ N=679), eGFR (HIV− N=1282, HIV+ N=662), BMI (HIV− N=1444; HIV+ N=699), hemoglobin (HIV− N=1275, HIV+ N=651), CD4 cell count (HIV+ N=512), HIV‐1 RNA (HIV+ N=539).

The prevalence of several cardiovascular risk factors differed by HIV status. HIV‐infected women veterans had a higher prevalence of low HDL cholesterol, elevated TGs, smoking, HCV infection, hemoglobin <12 g/dL, alcohol and cocaine abuse/dependence, and a lower prevalence of HTN and obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2; P<0.05 for all).

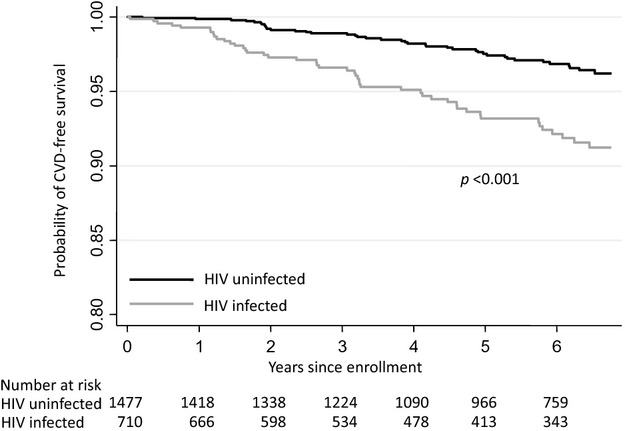

During a median follow‐up of 6.0 years, there were 86 incident CVD events (53% HIV infected). Of these events, 13% were AMI, 8% were unstable angina, 22% were ischemic stroke, and 57% were HF. All events occurred in unique individuals. Median time to CVD event was 3.1 versus 3.7 years (P=0.11) for HIV‐infected, compared to uninfected, women. Incident CVD per 1000 person‐years was significantly higher among HIV‐infected (13.5; 95% CI=10.1, 18.1), compared to uninfected, women (5.3; 95% CI=3.9, 7.3; P<0.001; Figure). The incidence of CVD excluding HF was also higher among HIV‐infected women, compared to uninfected controls (incidence rate ratio [IRR] [95% CI]=2.3 [1.2, 4.5]), as was the incidence of HF excluding CVD (IRR [95% CI]=2.5 [1.5, 4.5]). The median age at time of the CVD event for HIV‐infected versus uninfected women was (49.3 years vs. 52.1 years; P=0.05). The median Framingham risk score was 3 for both HIV‐infected and uninfected women (P=0.3).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted Kaplan‐Meier's curves showing CVD‐free survival by HIV status. CVD indicates cardiovascular disease.

After adjusting for Framingham risk factors (age, lipids, smoking, blood pressure, and diabetes), other comorbidities (renal disease, obesity, HCV infection), substance use and abuse (cocaine and alcohol), and demographic factors, HIV‐infected women veterans had a significantly increased risk of total CVD, compared to uninfected women veterans (HR=2.8; 95% CI=1.7, 4.6; P<0.001; Table 2).

Table 2.

The Association Between HIV and Incident Total CVD*

| Characteristic | Model 1 (Demographics) | Model 2 (Framingham Risk Factors) | Model 3 (All Predictors) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV | 2.8 (1.8, 4.3) | 3.1 (2.0, 4.9) | 2.8 (1.7, 4.6) |

| Age (10‐year increments) | 2.1 (1.6, 2.7) | 1.7 (1.3, 2.3) | 1.7 (1.3, 2.3) |

| White | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Black | 1.4 (0.9, 2.3) | 1.3 (0.8, 2.1) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.2) |

| Other | 0.5 (0.1, 1.6) | 0.4 (0.1, 1.4) | 0.4 (0.1, 1.4) |

| Hypertension | 2.5 (1.6, 4.0) | 2.4 (1.5, 3.8) | |

| Diabetes | 1.6 (1.0, 2.7) | 1.6 (0.9, 2.7) | |

| LDL ≥160 mg/dL | 1.3 (0.7, 2.4) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.5) | |

| HDL <50 mg/dL | 0.9 (0.5, 1.5) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.4) | |

| TGs ≥150 mg/dL | 1.2 (0.7, 2.1) | 1.2 (0.7, 2.1) | |

| Nonsmoker | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Current smoker | 0.9 (0.6, 1.5) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.7) | |

| Past smoker | 1.3 (0.7, 2.4) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.5) | |

| HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitor | 1.1 (0.5, 2.2) | ||

| Hepatitis C | 1.1 (0.6, 2.0) | ||

| eGFR <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 3.0 (1.5, 6.2) | ||

| BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 1.2 (0.7, 1.9) | ||

| Cocaine abuse/dependence | 2.5 (1.1, 5.4) | ||

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 0.5 (0.2, 1.3) | ||

| Hemoglobin <12 g/dL | 1.7 (1.0, 2.8) |

BMI indicates body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; HMG‐CoA, 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl‐coenzyme A; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; TGs, triglycerides.

Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval).

Compared to uninfected women, HIV‐infected women had a significantly increased risk of CVD, regardless of CD4 count at baseline (≥500, 200 to 499, and <200 cells/mm3; Table 3). Among HIV‐infected women, there was a step‐wise increase in point estimates of CVD risk with decreasing baseline CD4 count (HR=2.3 [95% CI=1.2, 4.4]; HR=2.9 [95% CI=1.5, 5.7]; HR=3.8 [95% CI=1.9, 7.6], respectively), but these differences were not statistically significant. In addition, HIV‐infected women with detectable HIV‐1 RNA (≥500 copies/mL) were at greater risk for CVD, compared to uninfected women (HR=3.7 [95% CI=2.1, 6.5]), although CVD risk did not differ by level of HIV‐RNA suppression (P>0.05; Table 3). Being on ART at baseline did not appear to change these relationships (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association Between HIV Status, Baseline HIV‐Specific Covariates, and Incident Total CVD

| Model | HR (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|

| A | HIV− | 1 |

| HIV+, CD4+ T‐cell count ≥500 cells/mm3 | 2.3 (1.2, 4.4)* | |

| HIV+, CD4+ T‐cell count 200 to 499 cells/mm3 | 2.9 (1.5, 5.7)* | |

| HIV+, CD4+ T‐cell count <200 cells/mm3 | 3.8 (1.9, 7.6)* | |

| B | HIV− | 1 |

| HIV+, HIV‐1 RNA <500 copies/mL | 1.6 (0.6, 4.1)* | |

| HIV+, HIV‐1 RNA ≥500 copies/mL | 3.7 (2.1, 6.5)* | |

| C | HIV− | 1 |

| HIV+, HIV‐1 RNA <500 copies/mL, on HAART | 1.6 (0.7, 3.9)* | |

| HIV+, HIV‐1 RNA ≥500 copies/mL, on HAART | 4.4 (2.0, 9.9)* | |

| HIV+, not on HAART | 3.0 (1.8, 5.1)* | |

CI indicates confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy (3 or more antiretrovirals); HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; HR, hazard ratio; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein.

Model HRs adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, hypertension, diabetes, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, HMG‐CoA (3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl‐coenzyme A) reductase use, smoking, hepatitis C, estimated glomerular filtration rate, body mass index, cocaine and alcohol abuse or dependence, and hemoglobin.

Tests for differences in CVD risk among the HIV‐infected women were not statistically significant (P>0.05).

The rates of incident CVD per 1000 person‐years among HIV‐infected women who were on ART at baseline, compared to those who were not, were similar (12.8 [95% CI=8.0, 20.7] vs. 14.0 [95% CI=9.7, 20.1], respectively) but were significantly higher than the rate of incident CVD among uninfected women (5.3; 95% CI=3.9, 7.3; P<0.003).

HIV‐infected women had a more than 2‐fold increased risk of death, compared to uninfected women (HR=2.6; 95% CI, 1.7 to 3.9; P<0.001). For 8 women (5 HIV+), the underlying cause of death was associated with CVD. Of those 8, only 3 (1 HIV+) did not have an identified incident CVD event before death. Causes of death for these 3 women included hemorrhagic stroke (1 woman) and unstable angina (2 women). In a secondary analyses that included CVD death as an outcome, the HR for HIV did not differ substantially from those in primary analyses (HR=2.6; 95% CI, 1.6 to 4.3; P<0.01).

Discussion

HIV‐infected women had higher rates and risks of total CVD, compared to uninfected women. This increased risk persisted after adjustment for demographic factors, Framingham risk factors, other comorbidities, and substance (alcohol and cocaine) use and abuse.

Although multiple earlier studies have linked HIV infection to AMI, coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, and HF, the majority of the participants in these studies were men.7,14 Few studies have focused on women and even fewer included CVD events. Our results are consistent with earlier studies that linked HIV infection to an increased risk of CHD, ischemic stroke, and subclinical atherosclerosis among women.1–2,15

Our findings extend these results by examining this association in a national sample of HIV‐infected and uninfected women from the same healthcare system. In addition, we were able to adjust our analyses for demographic and Framingham risk factors, as well as comorbid conditions, smoking, and substance use and abuse variables (cocaine and alcohol). We assessed incident CVD events and included analyses stratified by HIV‐1 RNA, CD4 count, and ART use.

Our results are consistent with previous studies reporting HIV infection as an independent risk factor for CVD in men, suggesting that HIV infection increases the risk of CVD regardless of gender. In addition, ART, Framingham risk factors, and important comorbidities, such as HTN, renal disease, substance use, and anemia, may all contribute to CVD in men and women.7 Women with HIV‐1 RNA ≥500 copies/mL appear to be at particularly high risk. This finding is consistent with data from male veterans and emphasizes the importance of viral suppression. Future studies should investigate potential mechanisms linking viremia and CVD risk. What remains to be established is whether or not HIV‐infected women are at greater risk for CVD than HIV‐infected men. Among HIV‐infected women, whether those with lower CD4 counts are at greater risk for CVD than those with higher CD4 counts remains unclear. Likewise, whether or not CVD risk among HIV‐infected women with fully suppressed HIV‐1 RNA differs from that of uninfected women or from women with detectable HIV‐1 RNA should be investigated.

Although the exact mechanisms for increased CVD risk in HIV‐infected women are not known, earlier studies in men have suggested inflammation, immune activation, immunodeficiency, altered coagulation, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and endothelial dysfunction as potential mechanisms.16–18 HIV‐infected women also have increased immune activation markers (soluble CD163) that are associated with preclinical CVD, compared to uninfected women.19–20 Previous studies among uninfected women also suggest that depression21–22 (which has a higher prevalence among HIV‐infected vs. uninfected women22), earlier menopause23 (which may be more prevalent among HIV‐infected vs. uninfected women24), and other drivers of decreased estrogen, such as substance use,24–25 are all associated with incident CVD events.26 Whether these factors contribute to the excess risk of CVD among HIV‐infected women, however, is not known.

Currently, women represent 1 of every 4 people living with HIV infection in the United States and 20% of all new infections.5 Minority women are disproportionately affected by the HIV infection epidemic. Heart disease and cerebrovascular disease are the first and third leading causes of death among U.S. women ages 18 or older, respectively. For these reasons, future studies will be needed to elucidate the mechanisms of CVD in this high‐risk population. Without this knowledge, CVD risk stratification strategies for HIV‐infected women will not be optimal.

There are several limitations to this study that warrant discussion. First, unlike earlier studies in HIV‐infected men, we did not find significant associations between several traditional and HIV‐specific risk factors and total CVD. The lack of significance likely reflects our relatively small number of total events (n=86). However, when we compared these results to our larger study among HIV‐infected and uninfected male and female veterans,7 the associations between the majority of these risk factors and CVD risk were of similar direction and/or magnitude. We also did not have sufficient power to examine individual types of CVD events separately in this analysis. However, previous studies among men have demonstrated that HIV is significantly associated with each component of our CVD variable (AMI, unstable angina, ischemic stroke, and HF). Given the earlier associations of HIV with HF and nonadjudicated HF outcomes, ascertainment bias by HIV status for this component of our CVD outcome is possible. However, the HIV uninfected women in this cohort also had important HF risk factors present (eg, HTN or obesity) that could have precipitated a workup for HF. On balance, this study presents data from one of the few cohorts of HIV‐infected women that includes CVD events, detailed information on comorbidities, substance use and abuse, HIV‐specific biomarkers, and a comparator group of uninfected women from the same national healthcare system. Our study also incorporated VHA, Medicare, and National Death Index cause‐of‐death data to maximize our capture of incident CVD events. The contribution of ART to CVD risk among women is an important question that we are unable to assess given the limited sample size and number of events. This is an important question for future analyses.

In addition, it is difficult to know whether women in any cohort are truly representative of U.S. women living with HIV infection. Therefore, our findings should be replicated in cross‐cohort collaborations so that we can better understand the association between HIV and CVD in women.

In summary, HIV‐infected women have increased rates and risk of incident CVD events, as compared to uninfected women, after adjustment for demographic characteristics, Framingham risk factors, other comorbidities, and substance use and abuse. Future studies should focus on the identification of risk factors contributing to this excess risk of CVD among HIV‐infected women and strategies designed to prevent CVD in this high‐risk population.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation and the Clinical and Translational Science Award Grant No. UL1 RR024139 from the National Center for Research Resources; National Institute of Nursing Research Grant No. K01 NR013437; National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Grant No. HL095136; and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant Nos. AA013566‐10, AA020790, and AA020794, all components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Disclosures

The NIH did not participate in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or the interpretation of the data; nor did the NIH prepare, review, or approve of this manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policies of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Veterans for participating in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. Without their participation and the commitment of the study's staff and coordinators, this research would not be possible.

References

- 1.Currier JS, Taylor A, Boyd F, Dezii CM, Kawabata H, Burtcel B, Maa JF, Hodder S. Coronary heart disease in hiv‐infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999; 2003:506-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007; 92:2506-2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durand M, Sheehy O, Baril JG, Lelorier J, Tremblay CL. Association between HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy, and risk of acute myocardial infarction: a cohort and nested case‐control study using Quebec's public health insurance database. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011; 57:245-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lang S, Mary‐Krause M, Cotte L, Gilquin J, Partisani M, Simon A, Boccara F, Bingham A, Costagliola DFrench Hospital Database on H‐AC. Increased risk of myocardial infarction in hiv‐infected patients in France, relative to the general population. AIDS. 2010; 24:1228-1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC. HIV surveillance – epidemiology of HIV infection. Division of HIVx002FAIDS Prevention, national Center for HIVx002FAIDS, Viral Hepatitis, Sexual Transmitted Diseases and Tuberculosis Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, Georgia: 2013.

- 6.Fultz SL, Skanderson M, Mole LA, Gandhi N, Bryant K, Crystal S, Justice AC. Development and verification of a “virtual” cohort using the National VA Health Information System. Med Care. 2006; 44:S25-S30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, Skanderson M, Lowy E, Kraemer KL, Butt AA, Bidwell Goetz M, Leaf D, Oursler KA, Rimland D, Rodriguez Barradas M, Brown S, Gibert C, McGinnis K, Crothers K, Sico J, Crane H, Warner A, Gottlieb S, Gottdiener J, Tracy RP, Budoff M, Watson C, Armah KA, Doebler D, Bryant K, Justice AC. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 2013; 173:614-622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butt AA, Chang CC, Kuller L, Goetz MB, Leaf D, Rimland D, Gibert CL, Oursler KK, Rodriguez‐Barradas MC, Lim J, Kazis LE, Gottlieb S, Justice AC, Freiberg MS. Risk of heart failure with human immunodeficiency virus in the absence of prior diagnosis of coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2011; 171:737-743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998; 97:1837-1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butt AA, Fultz SL, Kwoh CK, Kelley D, Skanderson M, Justice AC. Risk of diabetes in HIV infected veterans pre‐ and post‐HAART and the role of HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2004; 40:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGinnis KA, Brandt CA, Skanderson M, Justice AC, Shahrir S, Butt AA, Brown ST, Freiberg MS, Gibert CL, Goetz MB, Kim JW, Pisani MA, Rimland D, Rodriguez‐Barradas MC, Sico JJ, Tindle HA, Crothers K. Validating smoking data from the Veteran's Affairs Health Factors dataset, an electronic data source. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011; 13:1233-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraemer KL, McGinnis KA, Skanderson M, Cook R, Gordon A, Conigliaro J, Shen Y, Fiellin DA, Justice AC. Alcohol problems and health care services use in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)‐infected and HIV‐uninfected veterans. Med Care. 2006; 44:S44-S51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002; 287:356-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasmussen LD, Engsig FN, Christensen H, Gerstoft J, Kronborg G, Pedersen C, Obel N. Risk of cerebrovascular events in persons with and without HIV: a Danish nationwide population‐based cohort study. AIDS. 2011; 25:1637-1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grunfeld C, Delaney JA, Wanke C, Currier JS, Scherzer R, Biggs ML, Tien PC, Shlipak MG, Sidney S, Polak JF, O'Leary D, Bacchetti P, Kronmal RA. Preclinical atherosclerosis due to HIV infection: carotid intima‐medial thickness measurements from the FRAM study. AIDS. 2009; 23:1841-1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker J, Quick H, Hullsiek KH, Tracy R, Duprez D, Henry K, Neaton JD. Interleukin‐6 and d‐dimer levels are associated with vascular dysfunction in patients with untreated HIV infection. HIV Med. 2010; 11:608-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burdo TH, Lo J, Abbara S, Wei J, DeLelys ME, Preffer F, Rosenberg ES, Williams KC, Grinspoon S. Soluble CD163, a novel marker of activated macrophages, is elevated and associated with noncalcified coronary plaque in HIV‐infected patients. J Infect Dis. 2011; 204:1227-1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ford ES, Greenwald JH, Richterman AG, Rupert A, Dutcher L, Badralmaa Y, Natarajan V, Rehm C, Hadigan C, Sereti I. Traditional risk factors and d‐dimer predict incident cardiovascular disease events in chronic HIV infection. AIDS. 2010; 24:1509-1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitch KV, Srinivasa S, Abbara S, Burdo TH, Williams KC, Eneh P, Lo J, Grinspoon SK. Noncalcified coronary atherosclerotic plaque and immune activation in HIV‐infected women. J Infect Dis. 2013; 208:1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boccara F, Cohen A. Immune activation and coronary atherosclerosis in HIV‐infected women: where are we now, and where will we go next? J Infect Dis. 2013; 208:1729-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferketich AK, Schwartzbaum JA, Frid DJ, Moeschberger ML. Depression as an antecedent to heart disease among women and men in the NHANES I study. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2000; 160:1261-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrison MF, Petitto JM, Ten Have T, Gettes DR, Chiappini MS, Weber AL, Brinker‐Spence P, Bauer RM, Douglas SD, Evans DL. Depressive and anxiety disorders in women with HIV infection. Am J Psychiatry. 2002; 159:789-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kojic EM, Wang CC, Cu‐Uvin S. HIV and menopause: a review. J Women Health. 2007; 16:1402-1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohl J, Partisani M, Demangeat C, Binder‐Foucard F, Nisand I, Lang JM. Alterations of ovarian reserve tests in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)‐infected women. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2010; 38:313-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harlow SD, Cohen M, Ohmit SE, Schuman P, Cu‐Uvin S, Lin X, Greenblatt R, Gurtman A, Khalsa A, Minkoff H, Young MA, Klein RS. Substance use and psychotherapeutic medications: a likely contributor to menstrual disorders in women who are seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 188:881-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosca L, Barrett‐Connor E, Wenger NK. Sex/gender differences in cardiovascular disease prevention: what a difference a decade makes. Circulation. 2011; 124:2145-2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]