Abstract

In giant encephalocele, head size is smaller than the encelphalocele. Occipital encephalocele is the commonest of all encephalocele. In our case, there was rare association with giant encephalocele with old hemorrhage in the sac. This was a unique presentation. In world literature, there was rare association with giant encephalocele with hemorrhage.

Keywords: Excision, giant encephalocele, hemorrhage, magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

In the western hemisphere, occipital encephaloceles constitute 80 to 90% of all encephaloceles.[1,2,3] Classically, patient with encephaloceles are born with the swelling at birth. The size and content of the encephalocele are variable. In occipital encephalocele, a globular swelling is noticed over the occipital bone in the midline. Encephaloceles could be pedunculated or sessile.[4,5] The size of the encephalocele is hardly ever indicate of its content. Most of the encephaloceles are brilliantly transilluminant on examination. However, when a large amount of gliosed brain tissue is present inside the sac, there may be variability in the degree of transillumination.

Usually, the head size is small.[6,7] The larger the brain herniation, the smaller is the head size. Sometimes, the encephalocele may be very large and is called giant encephalocele.[8]

Case Report

A 14-day-old neonate, admitted in our unit with a swelling at the back of head since birth. The swelling was increasing in size progressively after birth. Baby was born by lower segment caesarean section (LSCS). History of obstructed labor during birth was observed. There was a history of limb weakness. There was no bladder and bowel dysfunction.

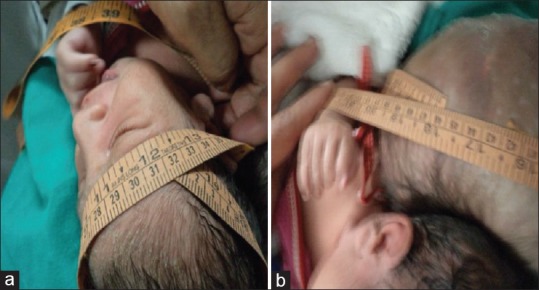

Baby was fourth sibling, others were healthy. No history of any congenital anomaly was recorded in the family. On local examination, swelling was spherical in shape. There was small ulceration at the center, which was partially healed by secondary intention. The circumference of the swelling was 45 cm as compared with head circumference of 31 cm [Figure 1a and 1b] and 21 cm in diameter. A consistency of the swelling was soft. Transillumination test was negative. Fluctuation test was positive. There was no any bruit or murmur over the swelling. Anterior frontanelle and posterior frontanelle were opened.

Figure 1.

(a) The occipito-frontal circumference was 31 cm and (b) encephalocele circumference was 45 cm

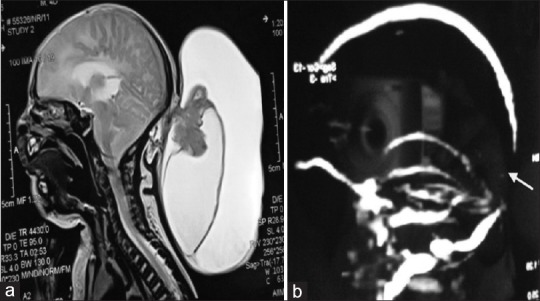

On neurological examination, the patient was conscious and accepting breast feeding normally. There was no limb weakness. Pupils were normal and reacting to light. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain showed a giant encephalocele at the occipital region [Figure 2a and 2b].

Figure 2.

(a) Sagittal MRI of brain, there are two different sac with variegated intensity, (b) MR venography shows there is a gap between the sagittal and transverse sinus

Under general anesthesia with prone position excision and repair of sac was done [Figures 3 and 4]. Following the anesthesia phase and prior to surgery, about 900 cc chronic hemorrhagic dark color fluid was aspirated. Peroperatively, there were two sacs; one sac contained altered hemorrhagic fluid (1000-1100 cc) and other gliosed brain [Figure 5]. Sac contained straw color fluid (400 cc). There were large dilated veins in the wall of the sac [Figure 2a] and occipital lobe on the left side was herniating into the sac along with the occipital horn containing choroid plexus. However, bony defect was not very large (4 × 4 cm).

Figure 3.

Preoperative position of encephalocele under general anaesthesia after aspirating 900cc of old haemorrhagic fluid (dark liquid blood)

Figure 4.

Photograph of the wound after repair

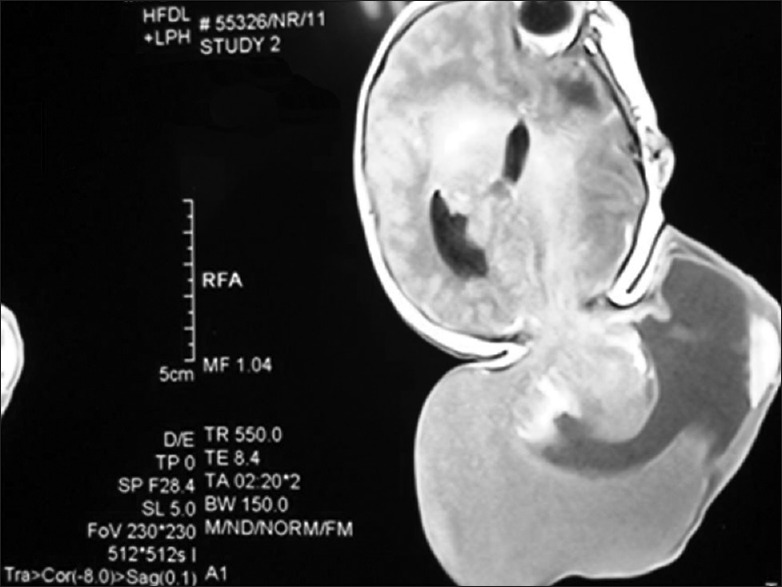

Figure 5.

MRI of brain with giant encephalocele with mild hydrocephalous and sac contain brain tissue and two cavities with different fluid densities

Discussion

In case of giant encephalocele, the head is smaller than the encephalocele. These giant encephaloceles contain a large amount of brain tissue and pose considerable problems during closure.[9]

Generally, patients with an occipital encephalocele are operated upon in the prone position with controlled ventilation and close temperature monitoring. Aspiration of the cerebro spinal fluid (CSF) prior to incision in patients with large encephalocele helps in dissection of the sac. For a circular encephalocele with a small occipital bone defect, a transverse incision is ideal. The sac is separated from the flap. Patients in whom the encephalocele extends above and below the posterior fossa need a vertical incision. Sometimes, the brainstem and occipital lobe are present in the sac. Care must be taken to identify the contents of the sac. Rarely, the sagittal sinus torcular and the transverse sinus are in the vicinity of the sac. It is preferable to preserve the neural tissue. The dura is repaired meticulously to get a water tight closure. The dural defect can be repaired by using the pericranium as a graft. In neonates and infants, no attempt should be made to cover the bone defect by a bone graft.[10,11]

A large number of factors influence the outcome in patients with occipital encephaloceles. These are the site, the size, the amount of brain herniated into the sac, the presence of brainstem or occipital lobe with or without the dural sinuses in the sac and the presence of hydrocephalus.[12,13,14,15]

However, in the present case, patient had approximately 1100 cc of dark hemorrhagic fluid, which was not earlier noticed by the author. It may be due to bleed during the prolonged obstructed labor prior to LSCS. As there was a history of increase in the size of the encephalocele between the time of birth and presentation to our unit, it is possible that a small amount of CSF was getting into the sac and adding to the volume of hemorrhagic fluid, which made the case more interesting and unique.

The source of bleeding was bridging vein and necrosed vessels. We did not use of tentalum mesh to enclose the neural content. As the brain tissue was gliosed and with nonviable choroid plexus, we removed this dead tissue. The child had no other congenital anomalies. After one month follow-up there was no history of seizure, unconsciousness, limb weakness, and pupils were normal in size and reacting to light.

The surgical management of children with large occipital skull defects along with herniation of a brain into the sac, at times can be extremely difficult. Preservation of the herniated brain parenchyma can be possibly by expansive cranioplasty. But it is often observed that microcephalic neonates with sac containing cerebrum, cerebellum, and brain stem structures have poor prognosis, even if a craniotomy is performed around the coronal suture for secondary craniostenosis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Martinez Lage JFR, Garcia Santos JM, Poza M, Puche A, Casas C, Rodriguez Costa T. Neurosurgical management of Walker-Warburg syndrome. Childs Nerv Syst. 1995;11:145–53. doi: 10.1007/BF00570255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morika M, Marabayashi T, Massamitsu T. Basal encephaloceles with morning glory syndrome and progressive hormonal and visual disturbances. Case report and review of literature. Brain Dev. 1995;17:196–201. doi: 10.1016/0387-7604(95)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sargent LA, Seyfer AT, Gunby En. Nasal encephalocele. Definite one stage reconstruction. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:571–5. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.68.4.0571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacob OJ, Rosenfeld JU, Watters DA. The repair of frontal encephalocele in Papua New Guinea. Aust Nz J Surg. 1994;64:856–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1994.tb04564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leong AY, Shaw CM. The pathology of occipital encephalocele and discussion of the pathogenesis. Pathology. 1979;11:223–34. doi: 10.3109/00313027909061948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.French BN. Youman's Neurological Surgery. 2nd ed. VIII. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1982. Midline fusion defect and defects of formation; pp. 1236–380. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cartwright KJ, Eisenberg MB. Tension pneumocephalus associated with rupture of a middle fossa encephalocele. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:292–5. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.76.2.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mealey J, Jr, Dzenitis AJ, Hockley A. The prognosis of encephalocele. J Neurosurg. 1970;32:209–18. doi: 10.3171/jns.1970.32.2.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahapatra AK. Management of encephalocele. In: Ravi Ramamurthi., editor. Text book of operative neurosurgery. Vol. 1. New Delhi: BI Publications Pvt. Ltd; 2005. pp. 279–90. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahapatra AK. Frontoethmoidal encephalocele. A study of 42 patients. In: Samii M, editor. Skull base anatomy, radiology and management. Basel, Switzerland: S Karger Basel; 1994. pp. 220–3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazolla RT. Congenital malformation in the frontonasal areas. Their pathogenesis and classification. Clin Plast Surg. 1976;13:513–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caviness VS, Evrad P. Occipital encephaloceles. A pathological and anatomical analysis. Acta Neurpath. 1995;32:245–55. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Copty M, Vervet S, Langelier R. Intranasal meningoencephalocele with recurrent meningitis. Surg Neurol. 1979;12:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friede RL. Uncommon syndrome of cerebellar vermis aplasia, II Tectocerebellar dysraphia with occipital encephalocele. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1978;20:764–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1978.tb15308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi T, Utsahmiya H, Hashimoto T. Transethmoidal encephaloceles. Surg Neurol. 1985;24:251–5. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(85)90125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]