Abstract

The same clock-genes, including Period (PER) 1 and 2, that show rhythmic expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) are also rhythmically expressed in other brain regions that serve as extra-SCN oscillators. Outside the hypothalamus, the phase of these extra-SCN oscillators appears to be reversed when diurnal and nocturnal mammals are compared. Based on mRNA data, PER1 protein is expected to peak in the late night in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) of nocturnal laboratory rats, but comparable data are not available for a diurnal species. Here we use the diurnal grass rat (Arvicanthis niloticus) to describe rhythms of PER1 and 2 protein in the PVN of animals that either show the species-typical day-active profile, or that adopt a night-active profile when given access to running wheels. For day-active animals housed with or without wheels, significant rhythms of PER1 or PER2 protein expression featured peaks in the late morning; night-active animals showed patterns similar to those expected from nocturnal laboratory rats. Since the PVN is part of the circuit that controls pineal rhythms, we also measured circulating levels of melatonin during the day and night in day-active animals with and without wheels and in night-active wheel runners. All three groups showed elevated levels of melatonin at night, with higher levels during both the day and night being associated with the levels of activity displayed by each group. The differential phase of rhythms in clock-gene protein in the PVN of diurnal and nocturnal animals presents a possible mechanism for explaining species differences in the phase of autonomic rhythms controlled, in part, by the PVN. The present study suggests that the phase of the oscillator of the PVN does not determine that of the melatonin rhythm in diurnal and nocturnal species or in diurnal and nocturnal chronotypes within a species.

Keywords: Chronotype, diurnal grass rat, PVN, pineal, melatonin, Period

1. Introduction

Multiple cell-autonomous oscillators that rhythmically express a multitude of genes comprise the master circadian oscillator of the mammalian suprachiasmatic nucleus (Welsh et al., 2010). The molecular core of these cellular oscillators is an autoregulatory transcriptional and translational feedback loop (Ko and Takahashi, 2006), which includes several clock genes such as Period (PER) 1 and 2. Rhythms in the expression of PER1 and 2 proteins have been reported for many brain regions outside the SCN (Granados-Fuentes et al., 2004, Duncan et al., 2013) and also in several peripheral organs (Scheer et al., 2001, Escobar et al., 2009, Dibner et al., 2010, Bonaconsa et al., 2014). These and other observations suggest that local oscillators outside the SCN may contribute to region and tissue specific rhythmic functions throughout the brain and body.

In the hypothalamus of laboratory rats, rhythmic expression of PER mRNA, but not PER2 mRNA or protein, has been described in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN; Asai et al. 2001; Minana-Solis et al., 2009). The PVN receives direct inputs from the SCN (Munch et al., 2002) and is part of a multi-synaptic pathway that is responsible for the circadian and photic regulation of the pineal gland and the pineal's melatonin rhythm (Moore, 1996). Thus the phase of a local neural oscillator in the PVN could contribute to the phase of the melatonin rhythm.

Irrespective of phase preference for the display of activity, the phase of the melatonin rhythm is more or less the same across mammalian species (Reiter, 1991b), yet recent observations about the phases of extra-SCN, non-hypothalamic oscillators demonstrate that those of diurnal grass rats (Ramanathan et al. 2010b), Octodon degus (Otalora et al., 2013) and humans (Li et al., 2013) are 180° out of phase compared to those of nocturnal rodents (Amir et al., 2004, Amir and Robinson, 2006). Thus, given the common phase of the melatonin rhythm across diurnal and nocturnal mammalian species and the involvement of the PVN in the mediation of that rhythm, one question addressed here relates to potential differences as well as similarities between the phase of the PVN oscillator in diurnal and nocturnal mammalian species. For nocturnal laboratory rats, mRNA for PER1 peaks around zeitgeber time (ZT) 16 (Asai et al., 2001, Minana-Solis et al., 2009); suggesting that the peak of PER 1 protein occurs during the late night, which is the time of peak PER protein expression in several areas of the brain of nocturnal species (Amir et al., 2004, Lamont et al., 2005, Angeles-Castellanos et al., 2007, Feillet et al., 2008); comparable data for the PVN are not available from diurnal mammalian species.

Here we characterized PER1 and PER2 protein expression at two anatomical levels, the anterior and posterior regions of the PVN,(aPVN and pPVN respectively), where pre-autonomic neurons reside (Swanson and Kuypers, 1980, Swanson and Sawchenko, 1980, Swanson et al., 1980, Smale et al., 1989; Teclemariam-Mesbah et al., 1999) in diurnal grass rats (Arvicanthis niloticus) kept in standard laboratory conditions (Experiment 1A). Our aim was to determine if the phase profile of PER1 and 2 rhythms described for other brain regions of the grass rats (Ramanathan et al., 2010a, Ramanathan et al., 2010b) generalize to a nucleus that regulates autonomic functions, including the rhythm of melatonin production by the pineal gland. With respect to control of the pineal gland, the two levels of the PVN used for this analysis contain a significant proportion of the PVN neurons that communicate with the pineal via the sympathetic outflow to the gland (Teclemariam-Mesbah et al., 1999). Thus our aPVN level includes the dorsal and medial parvocellular divisions of the PVN, where third-order pre-autonomic neurons that regulate the pineal gland have been identified with trans-synaptic retrograde tracers (Teclemariam-Mesbah et al., 1999). Similarly, our pPVN level included part of the medial and ventral parvocellular divisions (Saper, 2004), where additional neurons of the PVN that contribute to the hypothalamic-pineal pathway have been identified (see Figure 6C in Teclemariam-Mesbah et al., 1999).

Grass rats are clearly diurnal in their natural habitat (Blanchong and Smale, 2000) and in captivity (Blanchong et al., 1999), but under some conditions they show remarkable plasticity and individual differences in their phase preference for the display of activity. Particularly, when given access to running wheels a proportion of diurnal grass rats become predominantly night-active (NA), whereas other individuals retain their day-active (DA) profile, even when wheels are available (Blanchong et al., 1999). The phase of brain extra-hypothalamic oscillators of NA grass rats appears to be 180° out of phase with respect to that of DA animals, thus resembling the phase typical of nocturnal species (Ramanathan et al., 2010b). However, at least in the ventral subparaventricular zone [vSPZ;(Ramanathan et al., 2006)], the hypothalamic dorsal tuberommamillary nuclei (dTMN) and the dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMN;Nunez et al. 2012), that reversal of phase is not complete, and thus the circadian profile of the hypothalamus of NA grass rats retains features typical of diurnal animals.

In Experiment 1B we compared the rhythmic expression of PER1 and 2 proteins in the aPVN and pPVN of DA and NA grass rats, to determine if the oscillator of the PVN of NA animals adopts a nocturnal profile, as is the case for extra-hypothalamic oscillators (Ramanathan et al., 2010a, Ramanathan et al., 2010b) or, if alternatively, it behaves like other hypothalamic sites that retain diurnal features (Ramanathan et al., 2006, Nunez et al., 2012). Any putative change in the oscillator of the PVN would raise the question of how the nocturnal rise in melatonin would be affected. Therefore, we also measured melatonin during the day or night in diurnal grass rats with or without wheels, as well as in NA animals (Experiment 2), to determine if melatonin profiles remained nocturnal regardless of changes in the preferred phase for the display of activity and the potential reversal of the phase of the PVN oscillator.

2. Methods

Experiment 1A and 1B

Animals and housing

Adult male grass rats (Arvicanthis niloticus) from our breeding colony at Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA, were housed individually in Plexiglas cages (34×28×17 cm3), under a 12:12-h LD cycle [lights on at ZT 0], with a red light (<5 lx) on throughout the dark phase, and with free access to food (PMI Nutrition Prolab RMH 2000, Brentwood, MO, USA) and water. Grass rats were initially divided into two groups: Day active sedentary (DAS; Experiment 1A) and Wheel runners. Wheel runners were housed in the same Plexiglas cages, but equipped with running wheels (26 cm diameter; 8 cm width). Wheel runners underwent chronotype determination in order to be classified as a day or night active grass rats (DA and NA respectively; Experiment 1B) using methods previously published (Blanchong et al., 1999; Ramanathan, 2010b) and described below. All experiments were performed in compliance with guidelines established by the Michigan State University All University Committee on Animal Use and Care, and the National Institute of Health guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Chronotype determination: Experiment 1B

Wheel running data were continuously collected using a DSI Dataquest 3 system (MiniMitter, Sunriver, OR, USA) and actograms were generated using the Vital View program (MiniMitter, Sunriver, OR, USA). Activity profiles were used to classify grass rats as DA or NA after obtaining a stable wheel running rhythm for at least two weeks. An animal was classified as DA if daily activity ceased within 2 h after lights-out and classified as NA if activity continued for more than 4 h after lights-out (Blanchong et al., 1999). Animals exhibiting crepuscular activity patterns were omitted from the study.

PER1 and 2 protein expression in the aPVN and pPVN

Perfusion and tissue preparation

Animals (n=5-8 per ZT for each group of Experiments 1A and 1B) were perfused at ZTs 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22. At the prescribed ZT, the animals were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (Ovation Pharmaceutical, Deerfield, IL, USA) and perfused transcardially with 0.01 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. An aluminum hood covered the heads of the animals perfused during the dark period to prevent exposure to light. Brains were removed and post-fixed for 4 h in 4% paraformaldehyde and transferred to 20% sucrose solution overnight, then stored in cryoprotectant at −20 °C until sectioning. Brains were sectioned coronally at 30 μm using a freezing microtome and the sections stored in cryoprotectant at −20 °C for future processing.

Immunocytochemical procedures

Sections containing the PVN were subjected to Immunocytochemical procedures for detecting either PER1 or PER2 protein expression as previously described (Ramanathan et al., 2006). The procedure was the same for Experiment 1A and 1B, but the two tissue sets were processed separately. Briefly, free-floating sections were rinsed 3×10 min in 0.01 M PBS before the first as well as all subsequent incubations. All sections were incubated in 5% Normal Donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) in 0.01 M PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. The sections were incubated in the primary antibody (mPER1# 1177, made in rabbit, 1:20,000, a gift from Dr. D. R. Weaver, University of Massachusetts Medical School, MA, USA) on a rotator for 48 h at 4 °C. On the third day, they were incubated in biotinylated secondary antibody (Donkey anti Rabbit; 1:200, Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME), followed by Avidin–Biotin peroxidase complex (ABC Vectastain Kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Protein was visualized by reacting with diaminobenzidine (0.5 mg/mL Sigma) in sodium acetate buffer (pH 7.2) and 3% hydrogen peroxide. Nickel sulfate was added to yield a purple reaction product. For detecting PER2 immunoreactivity, the same procedure was followed except that for PER2, the primary antibody (made in rabbit, and generously provided by Dr. D. R. Weaver, University of Massachusetts Medical School, MA, USA) was diluted to 1:10,000. All tissue was mounted onto gelatin-coated slides, dehydrated and cover slipped. To control for non-specific staining resulting from the procedure, all the steps of the protocol were replicated excluding the incubation with the primary antibody. This control procedure produced no staining in any of the anatomical areas examined in the two experiments.

Data collection and analysis

Single sections were selected containing either the anterior or posterior paraventricular nucleus (aPVN and pPVN respectively) using the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 2007). To quantify PER1 and PER2 protein in both brain regions, immunoreactive cell nuclei were counted bilaterally in the aPVN (Bregma=−1.88mm) and pPVN (Bregma=−2.12mm), by an investigator who was not aware of the time of perfusion or of the chronotype of each animal. Even at sampling times of low protein expression, the boundaries of the nucleus were evident at both levels (See Figure 1 and Figure 3 for the boundaries identified respectively for the aPVN and pPVN). There was no apparent segregation of labeled cells with respect to subdivisions of the PVN, thus for both levels, total bilateral counts were used for statistical analysis. For all experiments, statistical significance was set at p value of less than or equal to 0.05, and for all data sets, SPSS version 22 was the software used for all statistical analyses. For the DAS group in Experiment 1A, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the effect of ZT on PER1 and 2 expression in each region. Significant F ratios were followed by comparisons between ZTs using least significant difference (LSD) post hoc tests. For Experiment 1B data from the DA and NA animals were analyzed using individual two-way ANOVAs (ZT×group) for each brain region and each PER protein, using total bilateral counts of labeled cells as the dependent variable. Significant interactions were followed by analyses of simple main effects and, when appropriate, post hoc comparisons of individual means used Fisher's LSD tests.

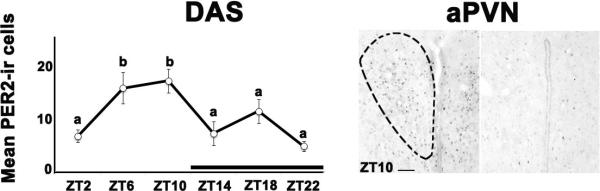

Figure 1. PER2 expression peaks during the late light phase in the anterior paraventricular nucleus (aPVN) of DAS grass rats.

The graph shows mean (± SEM) number of PER2-ir cells (left panel). Significant differences between ZTs are noted by different letters. The black bar indicates the dark phase of the cycle. The right panel shows photomicrographs depicting maximal and minimal PER 2 expression in the aPVN of DAS grass rats. Location of the aPVN is based on Paxinos and Watson (1997); the anatomical boundaries of the nucleus are indicated on the photomicrograph for the ZT 10 sampling time. Scale bar = 200μm. Period, PER; immumnoreactive, ir; zeitgeber time, ZT, SEM, standard error of the mean.

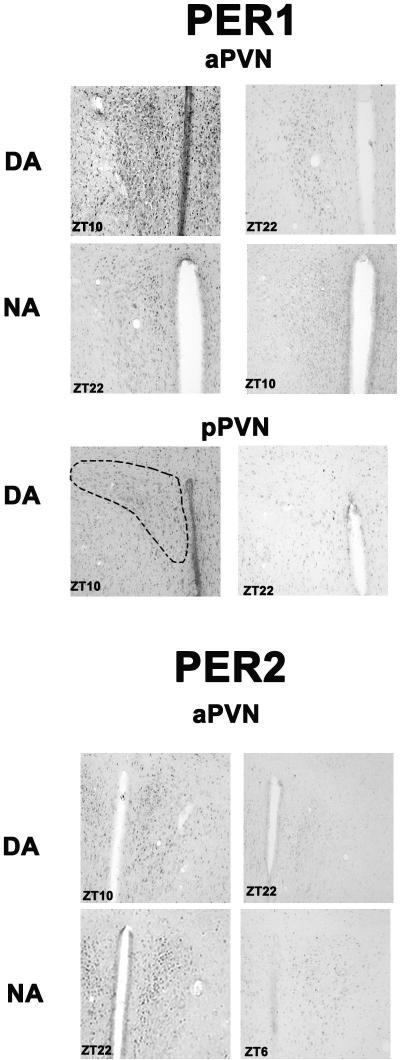

Figure 3. Photomicrographs showing immunostaining for PER1 and PER2 proteins in the anterior (aPVN) and posterior (pPVN) paraventricular nucleus.

The top four panels show maximal and minimal expression of PER1 protein in the aPVN of DA and NA grass rats. Locations for the aPVN and pPVN are based on Paxinos and Watson (1997). The middle panels show maximal and minimal expression of PER1 protein in the pPVN of DA grass rats; the frame on the left also serves to indicate the boundaries of the nucleus at this level. The bottom panels show maximal and minimal expression of PER2 protein in the aPVN of DA and NA grass rats. Scale bar = 200μm. anterior PVN, aPVN; posterior PVN, pPVN; Period, PER; zeitgeber time, ZT; immumnoreactive, ir; day active, DA; night active, NA.

Experiment 2: Plasma melatonin levels in grass rats with and without access to wheels

Adult male grass rats (n=5-8 per group/ZT) from our breeding colony housed and chronotyped as described above were sampled at either ZT6 or ZT18. At the prescribed ZTs, the animals were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (Ovation Pharmaceutical, Deerfield, IL, USA). Whole blood samples were obtained via cardiac puncture using a heparinized 25 gauge needle. Samples were immediately centrifuged for 15min at 1500× g at 4°C. Plasma was removed and stored at −80°C for final processing.

Data collection and analysis

Plasma levels of melatonin were quantified using the competitive enzyme linked immunosorbant assay procedure from a commercial source (Geneway Biotech Inc., San Diego, CA). Initially, each sample was passed through a C18 reversed phase column, extracted with methanol, evaporated to dryness, and reconstituted with water. Next, 50 μl of each sample was pipetted into the corresponding well coated with the goat-anti-rabbit antibody on a microtiter plate. An unknown amount of antigen present in the sample and a fixed amount of enzyme-labeled antigen competed for the binding sites of the antibodies coated onto the wells of the microtiter plate. After incubation for at least 20 hrs at 4°C, the wells were washed three times with a phosphate buffer washing solution. 150 μl of enzyme conjugate was added to each well and the plate was incubated for 120 minutes at room temperature on an orbital shaker set to 500 rpm. A p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate solution was added to the wells, and the plate was incubated for an additional 20 minutes on an orbital shaker set to 500 rpm. Finally, a p-nitrophenyl phosphate stop solution was added into each well to stop the reaction. The concentration of antigen was inversely proportional to the optical density and was measured at 405nm in a photometer. The standard curve and sample values were calculated using Sigma Plot. Melatonin standards provided with the kit were used to construct a calibration curve against which the unknown samples were calculated. The sensitivity of the assay was 1.6 pg/mL.

Two-way ANOVAs (Group × ZT) were used to assess the effect of ZT and group on plasma melatonin levels. A significant interaction was followed by analysis of the simple main effects of Group and ZT, and by comparison of individual means. Fisher's LSD tests were used for comparisons between groups within each ZT and independent-group t-tests (2-tailed) were used for evaluating the effects of ZT within groups.

3. Results

Experiment 1A

For PER1 expressing cells, ANOVAs revealed no significant main effect of ZT in either the aPVN (F5,27=1.343; p=0.277) or the pPVN (F5,29=2.225; p=0.079) of DAS grass rats (data not shown). Figure 1 (left panel) shows the mean (± standard error of the mean (SEM)) number of PER2 positive cells in the aPVN and the right panels show representative photomicrographs depicting the peak and trough of PER2 expression in the aPVN of DAS grass rats. For these data, ANOVAs revealed a significant effect of ZT with a peak at ZT10 within the aPVN (F5,29=5.655; p=0.001). In the pPVN there was an almost significant main effect of ZT on PER2 expression with a peak at ZT10 (F5,29=2.493; p=0.054; data not shown).

Experiment 1B

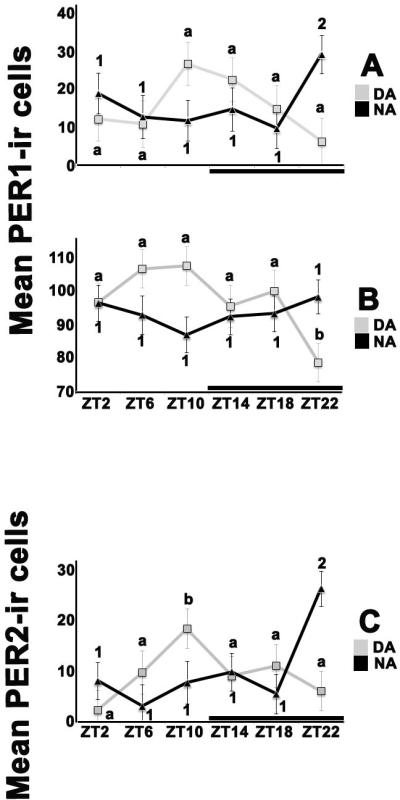

For the number of cells expressing PER1 in the aPVN the two-way ANOVA revealed a significant ZT × chronotype interaction (F5,74=3.192; p=0.012;Figure 2). Follow up analyses of the simple main effect of ZT within group revealed no significant effect of ZT in DA grass rats (F5,33=1.532; p=0.207) and a significant simple main effect of ZT in NA grass rats with a peak at ZT22 (F5,41=2.744; p=0.031). For the number of cells expressing PER1 in the pPVN, the two way ANOVA detected a significant ZT × chronotype interaction (F5,76=2.809; p=0.022). Follow up analyses of the simple main effect of ZT within chronotype found a significant effect of ZT in DA grass rats with a peak between ZT6 and 10(F5,34=2.582; p=0.044) and no significant main effect of ZT in NA grass rats (F5,42=0.554; p=0.735).

Figure 2. Chronotype and time of day differences in PER1 and 2 protein expression within the anterior (aPVN) and posterior (pPVN) paraventricular nucleus of grass rats.

The graphs present means (± SEM) for cell counts for DA (light squares) or NA (black triangles) across ZTs. For all graphs, significant differences between ZTs within chronotype are noted by different letters (for DA) or different numbers (for NA). See text for details of the statistical tests. Black bars indicate the dark phase of the cycle. (A) PER 1 protein expression in the aPVN peaked at ZT 10 in DA grass rats and at ZT 22 in NA ones. (B) In the pPVN ZT only had a significant effect on PER 1 protein expression in DA animals, with a significant drop at ZT 22. (C) For PER 2, the pattern of protein expression in the aPVN was similar to that for PER 1, with a peak at ZT 10 for DA grass rats and one at ZT 22 for NA animals. Period, PER; zeitgeber time, ZT; immumnoreactive, ir; day active, DA; night active, NA; SEM, standard error of the mean.

The two way ANOVA detected a significant ZT × chronotype interaction (F5,72=4.268; p=0.002; Figure 2) in PER2 expression in the aPVN. Follow up analyses found a significant simple main effect of ZT in the DA group with peak expression at ZT10 (F5,34=2.77; p=0.033) and a significant simple main effect of ZT in the NA group with a peak at ZT22 (F5,38=4.114; p=0.004). For PER2 expressing cells in the pPVN, the ANOVA revealed no ZT × chronotype interaction, with no overall effects of ZT or group (F5,71=1.028; p=0.408; data not shown).Figure 3 shows photomicrographs at the maximal and minimal times of expression of PER 1 and PER2, for groups in which a significant effect of ZT was detected.

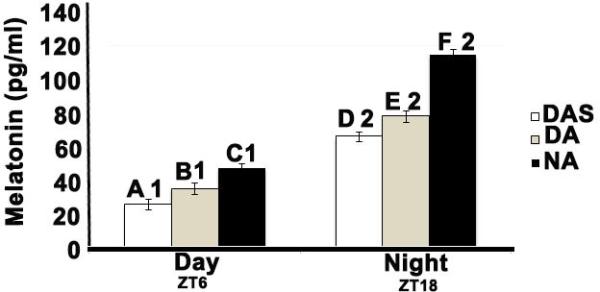

Experiment 2

The two-way ANOVA revealed a significant ZT × group interaction (F 2,32 =10.613; p=0.00; Figure 4). Tests of the simple main effect of ZT showed that for the three groups, night time values were significantly higher than day time ones (all t values with degrees of freedom of 10 or 11= 10.50-13.270, all ps< 0.001). Within ZT, the simple main effect of group was statistically significant both at ZT6 (F2,17=27.265; p < 0.001) and at ZT18 (F2,15=34.591; p < 0.001). Individual group comparisons showed that for both ZTs, the groups differed significantly among themselves, with NA grass rats having the highest and DAS grass rats the lowest levels of melatonin.

Figure 4. Nocturnal activity does not disrupt the nocturnal rise in plasma melatonin in grass rat.

Bar graph showing the mean (± SEM) pg/ml of plasma melatonin for each group (DAS, DA and NA) and ZT (ZT6=Day and ZT18=Night). Significant differences between groups within each ZT are denoted by letters: means with different letters are significantly different from each other. Significant differences between ZTs, within groups are denoted by numbers; means with different numbers are significantly different from each other. See text for details of the statistical comparisons. Day active sedentary, DAS; day active, DA; night active, NA; zeitgeber time, ZT; SEM, standard error of the mean.

4. Discussion

The major finding of Experiment 1A was that when a rhythm in PER2 protein expression was present in the PVN of grass rats, it featured a peak late in the light period (i.e., ZT 10), which is about 12 hours earlier than what the mRNA data predict for PER1 in nocturnal species (Asai et al., 2001, Minana-Solis et al., 2009, Dzirbikova et al., 2011). Since PER 1 and 2 appear to have redundant roles in circadian regulation (for example see (Maywood et al., 2014), these results serve to extend previous observations of phase differences in extra-SCN oscillators between grass rats and nocturnal rodents (Ramanathan et al., 2010b) to a hypothalamic nucleus with connections to autonomic neurons (Swanson and Kuypers, 1980, Swanson and Sawchenko, 1980, Swanson et al., 1980,Teclemariam-Mesbah et al., 1999) and to pre-autonomic brain sites (Stern, 2001, Kalsbeek et al., 2011). Species differences in the phase of the PVN oscillator may be responsible for the divergent phases of diurnal and nocturnal mammalian species with respect to rhythms that are controlled by autonomic outputs (Scheer et al., 1999, Scheer et al., 2001, Duarte et al., 2003, Scheer et al., 2003) Thus, these observations support the hypothesis that the emergence of a diurnal profile in mammals depends, at least in part, upon a reversal of the phase of extra-SCN oscillators from that typical of nocturnal species with respect to the phase of the oscillator of the SCN (Ramanathan et al., 2010a, Ramanathan et al., 2010b) and the light-dark cycle.

The results of Experiment 1B show that access to running wheels increases the amplitude of the PER1 protein rhythm in the PVN of grass rats, and that the phase of that rhythm, as well as that of PER2 protein when present, is associated with the animals’ phase preference for the display of activity. Thus, as grass rats adopt a nocturnal profile, the oscillator of the PVN shows a reversal in phase similar to what is seen in extra-SCN oscillators outside the hypothalamus (Ramanathan et al., 2010b). In contrast to our results, PER1 protein expression in the PVN is unaffected in nocturnal laboratory rats that become active during the day in response to a forced-activity paradigm that emulates the conditions of human shift workers (Salgado-Delgado et al., 2010). Although species differences may be responsible for these divergent outcomes, these observations nevertheless support the view that voluntary reversals of the phase of activity (present study) affect the brain and the circadian system in a fashion that differs from the effects of forced-activity paradigms (Karatsoreos et al., 2011, McDonald et al., 2013, Saderi et al., 2013, Hsieh et al., 2014). In agreement with this view are the results of direct comparisons of the effects on the brain of spontaneous and forced wakefulness (Castillo-Ruiz et al., 2010, Castillo-Ruiz and Nunez, 2011). Thus, in grass rats, voluntary nocturnal wakefulness results in increased neuronal activation, as indicated by Fos expression, in reward areas of the brain (i.e., horizontal diagonal band, ventral tegmental area, and supramammillary nuclei; Castillo-Ruiz et al.,2010), which is an observation not extended to studies using a forced-wakefulness paradigm with the same species (Castillo-Ruiz and Nunez, 2011) The NA grass rat appears to be an attractive model to understand the consequences of activity during the rest phase in a diurnal species, without the effects of the stress associated with forced-wakefulness paradigms (Castillo-Ruiz and Nunez, 2011).

Our observations about the reversal of the phase of the PVN oscillator in NA grass rats contrast with what has been seen in other extra-SCN hypothalamic sites in these animals. For example in the vSPZ, the switch to being active at night is not accompanied by a reversal in either neuronal activity as indicated by cFos (Rose et al., 1999, Mahoney et al., 2000, Mahoney et al., 2001, Smale et al., 2001, Schwartz and Smale, 2005) or PER1 and 2 protein expression (Ramanathan et al., 2010b). A similar preservation of the diurnal like phase of rhythms in PER1 and 2 proteins, in spite of a reversal in the preferred phase for activity, is seen in the DMN and the dTMN of NA grass rats (Nunez et al., 2012). Thus, in the hypothalamus of the NA grass we find a mosaic of phases, and not the uniform phase reversal seen in extra-hypothalamic sites (Ramanathan et al., 2010b). This could signal an internal circadian asynchrony in areas of the brain that regulate important functions such as vigilance [i.e., the dTMN (Gerashchenko et al., 2004, Valdes et al., 2010)], or autonomic functions [i.e., the DMN(Chou et al., 2003) and PVN (Saper et al., 1976, Swanson and Sawchenko, 1980)], that asynchrony could be responsible for the sleep and metabolic pathologies of humans that show chronic enhanced activity at night (Asher and Schibler, 2011, Gamble and Young, 2013).

As expected given the results from many other diurnal species (Reiter, 1991b, a), we found in Experiment 2 that melatonin is elevated at night in grass rats. Combined with the observation of a phase difference in PER protein expression in the PVN of diurnal grass rats and that expected from nocturnal lab rats given the ZT of peak abundance of PER mRNA (Minana-Solis et al., 2009) it is possible that the phase of the local oscillator of the PVN does not modify the circadian signals from the SCN that dictate the phase of the melatonin rhythm. The results from comparisons of DA and NA grass rats also support this interpretation, since both chronotypes showed a nocturnal increase in melatonin, even though they had PER protein rhythms in the PVN that were 180° out of phase. Thus, it is possible that the inputs to the PVN from the SCN that control the pineal gland in all mammalian species and chronotypes are directed to relay neurons of the PVN that lack rhythms in clock-gene expression; note that here the expression of PER 1 and 2 protein was not particularly associated with subdivisions of the PVN that contains neurons of the hypothalamic-pineal pathway (Teclemariam-Mesbah et al. , 1999). Alternatively, the PVN neurons that relay SCN information to the pineal may show a constant phase across species, and within-species chronotypes, even when the majority of the PVN neurons show phase reversals in clock-gene expression when diurnal and nocturnal species or chronotypes are compared.

The retention of a nocturnal elevation of circulating melatonin shown by NA grass rats is consistent with the results of studies with degus (Vivanco et al., 2007), another predominantly diurnal species in which individuals become night-active without losing the nocturnal elevation in circulating melatonin. In these cases, increased secretion of melatonin occurs during the active phase, which is the opposite of what diurnal species normally experience (Reiter, 1991b). NA grass rats, although they show substantial night-time wakefulness, they nevertheless display an increase in sleep-bout duration during the late night, between ZT16 and ZT20 (Schwartz and Smale, 2005), which includes a time of elevated melatonin levels in these animals (i.e., ZT18, present results). In many diurnal species such as birds, fish and non-human primates, melatonin acts as a powerful hypnotic (Mintz et al., 1998; Zhdanova, 2005; Rihel and Schier, 2013). Thus, it is possible that the increased sleep duration of NA grass rats in the late night is due to putative sleep promoting actions of melatonin in diurnal species. However, this possibility remains speculative, since in grass rats pinealectomy does not affect sleep or circadian rhythms (unpublished observations from Smale's laboratory). Interestingly degus that become night-active continue to show responses to melatonin, which include a drop in body temperature, typical of that predominantly diurnal species (Vivanco et al., 2007).

Finally, although the reversal of the phase of the PER protein rhythm of the PVN did not prevent the nocturnal elevation of melatonin in NA grass rats, melatonin levels were higher in these animals compared to those of the other day-active groups, both in the morning and at night. Since we used only two sampling times, we are not able to rule out the possibility of a phase shift in the nevertheless nocturnal melatonin rhythm of the NA grass rats, as is the case for degus that become nocturnal (Otalora et al., 2010). However, since NA grass rats with access to wheels are significantly more active than diurnal grass rats (Blanchong et al., 1999), and since exercise results in elevated levels of melatonin (Escames et al., 2012), one viable alternative explanation is that the elevated levels of melatonin in the NA animals stem from their relatively high levels of activity. This explanation also fits the observation that DA grass rats with running wheels show melatonin levels that, although lower than those of NA grass rats, are significantly higher than those of diurnal sedentary grass rats.

4.1 Conclusion

In summary, we found that the phase of rhythms in PER protein expression in the PVN of diurnal grass rats is 180° out of phase to that expected of nocturnal rodents, thus providing a potential mechanism to explain species phase differences in rhythmic autonomic functions controlled by this nucleus. Since the phase of the melatonin rhythm is more or less the same for diurnal and nocturnal species, the phase of the PVN oscillator does not appear to influence the control of the pineal gland by the SCN. This assertion is supported by the observation that when grass rats adopt a nocturnal activity profile, the nocturnal elevation in melatonin production is retained, even though there is a phase reversal in the rhythm of PER protein expression in the PVN. Taking into account other observations about rhythms in clock-gene proteins in other hypothalamic nuclei in NA animals (Ramanathan et al., 2010b, Nunez et al., 2012), the reversal in the phase of the PER protein rhythm of the PVN of these animals may result in an internal circadian asynchrony affecting the control of sleep and autonomic functions. Thus, the NA grass rat presents itself as a useful model to study the causes of human pathologies associated with the voluntary display of activity during the natural rest phase of diurnal mammalian species (Pietroiusti et al., 2010, Erren, 2013).

Highlights.

PER protein in the PVN peaks in the morning in diurnal grass rats.

PER protein in the PVN peaks in the night in night-active grass rats.

Melatonin is elevated at night in both night- and day-active animals.

Nocturnal activity in diurnal species appears to result in circadian asynchrony.

The night-active grass rat is an attractive model of human shift-work.

Abbreviations

- PER

Period

- SCN

suprachiasmatic nucleus

- PVN

paraventricular nucleus

- aPVN

anterior regions of the PVN

- pPVN

posterior regions of the PVN

- DMN

dorsomedial hypothalamus

- dTMN

dorsal tuberommamillary nuclei

- 3V

third ventricle

- mt

mammillothalamic tract

- Sub

submedius thalamic nucleus

- AHP

anterior hypothalamic area posterior part

- AHC

anterior hypothalamic area central part

- SOX

supraoptic decussation

- OPT

optic tract

- ArcM

Arcuate nucleus medial portion

- ME

median eminence

- ZI

zona incerta

- ir

immumnoreactive

- ZT

Zeitgeber time

- DAS

Day active sedentary

- DA

day active grass rats

- NA

night active grass rats

- LSD

least significant difference

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- vSPZ

ventral subparaventricular zone

- SEM

standard error of the mean

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amir S, Lamont EW, Robinson B, Stewart J. A circadian rhythm in the expression of PERIOD2 protein reveals a novel SCN-controlled oscillator in the oval nucleus of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. J Neurosci. 2004;24:781–790. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4488-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir S, Robinson B. Thyroidectomy alters the daily pattern of expression of the clock protein, PER2, in the oval nucleus of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and central nucleus of the amygdala in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2006;407:254–257. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angeles-Castellanos M, Mendoza J, Escobar C. Restricted feeding schedules phase shift daily rhythms of c-Fos and protein Per1 immunoreactivity in corticolimbic regions in rats. Neuroscience. 2007;144:344–355. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai M, Yoshinobu Y, Kaneko S, Mori A, Nikaido T, Moriya T, Akiyama M, Shibata S. Circadian profile of Per gene mRNA expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, paraventricular nucleus, and pineal body of aged rats. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66:1133–1139. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher G, Schibler U. Crosstalk between components of circadian and metabolic cycles in mammals. Cell Metabolism. 2011;13:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchong JA, McElhinny TL, Mahoney MM, Smale L. Nocturnal and diurnal rhythms in the unstriped Nile rat, Arvicanthis niloticus. J Biol Rhythms. 1999;14:364–377. doi: 10.1177/074873099129000777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchong JA, Smale L. Temporal patterns of activity of the unstriped Nile rat, Arvicanthis niloticus, in its natural habitat. Journal of Mammalogy. 2000;81:595–599. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaconsa M, Malpeli G, Montaruli A, Carandente F, Grassi-Zucconi G, Bentivoglio M. Differential modulation of clock gene expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, liver and heart of aged mice. Experimental Gerontology. 2014;55:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Ruiz A, Nixon JP, Smale L, Nunez AA. Neural activation in arousal and reward areas of the brain in day-active and night-active grass rats. Neuroscience. 2010;165:337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Ruiz A, Nunez AA. Fos expression in arousal and reward areas of the brain in grass rats following induced wakefulness. Physiology & Behavior. 2011;103:384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC, Scammell TE, Gooley JJ, Gaus SE, Saper CB, Lu J. Critical role of dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus in a wide range of behavioral circadian rhythms. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10691–10702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-33-10691.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibner C, Schibler U, Albrecht U. The mammalian circadian timing system: organization and coordination of central and peripheral clocks. Annual Review of Physiology. 2010;72:517–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte DPF, Silva VL, Jaguaribe AM, Gilmore DP, Da Costa CP. Circadian rhythms in blood pressure in free-ranging three-toed sloths (Bradypus variegatus). Brazilian J Med Biol Res. 2003;36:273–278. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000200016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan MJ, Prochot JR, Cook DH, Tyler Smith J, Franklin KM. Influence of aging on Bmal1 and Per2 expression in extra-SCN oscillators in hamster brain. Brain Res. 2013;1491:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzirbikova Z, Kiss A, Okuliarova M, Kopkan L, Cervenka L. Expressions of per1 clock gene and genes of signaling peptides vasopressin, vasoactive intestinal peptide, and oxytocin in the suprachiasmatic and paraventricular nuclei of hypertensive TGR[mREN2]27 rats. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 2011;31:225–232. doi: 10.1007/s10571-010-9612-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erren TC. Shift work and cancer research: can chronotype predict susceptibility in night-shift and rotating-shift workers? Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2013;70:283–284. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2012-100984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escames G, Ozturk G, Bano-Otalora B, Pozo MJ, Madrid JA, Reiter RJ, Serrano E, Concepcion M, Acuna-Castroviejo D. Exercise and melatonin in humans: reciprocal benefits. J Pineal Res. 2012;52:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar C, Cailotto C, Angeles-Castellanos M, Delgado RS, Buijs RM. Peripheral oscillators: the driving force for food-anticipatory activity. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;30:1665–1675. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feillet CA, Mendoza J, Albrecht U, Pevet P, Challet E. Forebrain oscillators ticking with different clock hands. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;37:209–221. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble KL, Young ME. Metabolism as an integral cog in the mammalian circadian clockwork. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2013;48:317–331. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2013.786672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerashchenko D, Chou TC, Blanco-Centurion CA, Saper CB, Shiromani PJ. Effects of lesions of the histaminergic tuberomammillary nucleus on spontaneous sleep in rats. Sleep. 2004;27:1275–1281. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granados-Fuentes D, Saxena MT, Prolo LM, Aton SJ, Herzog ED. Olfactory bulb neurons express functional, entrainable circadian rhythms. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;19:898–906. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2004.03117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh WH, Escobar C, Yugay T, Lo MT, Pittman-Polletta B, Salgado-Delgado R, Scheer F, Shea SA, Buijs RM, Hu K. Simulated shift work in rats perturbs multiscale regulation of locomotor activity. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 2014;11 doi: 10.1098/rsif.2014.0318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalsbeek A, Yi CX, Cailotto C, la Fleur SE, Fliers E, Buijs RM. Piggins HD, Guilding C, editors. Mammalian clock output mechanisms. Essays in Biochemistry: Chronobiology. 2011;49:137–151. doi: 10.1042/bse0490137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatsoreos IN, Bhagat S, Bloss EB, Morrison JH, McEwen BS. Disruption of circadian clocks has ramifications for metabolism, brain, and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1657–1662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018375108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko CH, Takahashi JS. Molecular components of the mammalian circadian clock. Hum Mol Genet 15 Spec No. 2006;2:R271–277. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont EW, Robinson B, Stewart J, Amir S. The central and basolateral nuclei of the amygdala exhibit opposite diurnal rhythms of expression of the clock protein Period2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4180–4184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500901102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JZ, Bunney BG, Meng F, Hagenauer MH, Walsh DM, Vawter MP, Evans SJ, Choudary PV, Cartagena P, Barchas JD, Schatzberg AF, Jones EG, Myers RM, Watson SJ, Jr., Akil H, Bunney WE. Circadian patterns of gene expression in the human brain and disruption in major depressive disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:9950–9955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305814110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney M, Bult A, Smale L. Phase response curve and light-induced fos expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus and adjacent hypothalamus of Arvicanthis niloticus. J Biol Rhythms. 2001;16:149–162. doi: 10.1177/074873001129001854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney MM, Nunez AA, Smale L. Calbindin and Fos within the suprachiasmatic nucleus and the adjacent hypothalamus of Arvicanthis niloticus and Rattus norvegicus. Neuroscience. 2000;99:565–575. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maywood ES, Chesham JE, Smyllie NJ, Hastings MH. The Tau mutation of casein kinase 1epsilon sets the period of the mammalian pacemaker via regulation of Period1 or Period2 clock proteins. J Biol Rhythms. 2014;29:110–118. doi: 10.1177/0748730414520663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RJ, Zelinski EL, Keeley RJ, Sutherland D, Fehr L, Hong NS. Multiple effects of circadian dysfunction induced by photoperiod shifts: Alterations in context memory and food metabolism in the same subjects. Physiology & Behavior. 2013;118:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minana-Solis MC, Angeles-Castellanos M, Feillet C, Pevet P, Challet E, Escobar C. Differential effects of a restricted feeding schedule on clock-gene expression in the hypothalamus of the rat. Chronobiol Int. 2009;26:808–820. doi: 10.1080/07420520903044240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz EM, Phillips NH, Berger RJ. Daytime melatonin infusions induce sleep in pigeons without altering subsequent amounts of nocturnal sleep. Neurosci Lett. 1998;258:61–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00849-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RY. Neural control of the pineal gland. Behav Brain Res. 1996;73:125–130. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munch IC, Moller M, Larsen PJ, Vrang N. Light-induced c-Fos expression in suprachiasmatic nuclei neurons targeting the paraventricular nucleus of the hamster hypothalamus: phase dependence and immunochemical identification. J Comp Neurol. 2002;442:48–62. doi: 10.1002/cne.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez A, Groves T, Martin-Fairey C, Cramm S, Ramanathan C, Stowie A. The cost of nocturnal activity for the diurnal brain.. Poster presented at the Biological Rhythms:Molecular and Cellular Properties poster session; 42nd Annual Conference of the Society for Neuroscience; New Orleans,LA.. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Otalora BB, Hagenauer MH, Rol MA, Madrid JA, Lee TM. Period gene expression in the brain of a dual-phasing rodent, the Octodon degus. J Biol Rhythms. 2013;28:249–261. doi: 10.1177/0748730413495521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otalora BB, Vivanco P, Madariaga AM, Madrid JA, Rol MA. Internal temporal order in the circadian system of a dual-phasing rodent, the Octodon degus. Chronobiol Int. 2010;27:1564–1579. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2010.503294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson CR. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietroiusti A, Neri A, Somma G, Coppeta L, Iavicoli I, Bergamaschi A, Magrini A. Incidence of metabolic syndrome among night-shift healthcare workers. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2010;67:54–57. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.046797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan C, Nunez AA, Martinez GS, Schwartz MD, Smale L. Temporal and spatial distribution of immunoreactive PER1 and PER2 proteins in the suprachiasmatic nucleus and peri-suprachiasmatic region of the diurnal grass rat (Arvicanthis niloticus). Brain Res 1073. 2006;1074:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.11.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan C, Stowie A, Smale L, Nunez A. PER2 rhythms in the amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis of the diurnal grass rat (Arvicanthis niloticus). Neurosci Lett. 2010a;473:220–223. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan C, Stowie A, Smale L, Nunez AA. Phase preference for the display of activity is associated with the phase of extra-suprachiasmatic nucleus oscillators within and between species. Neuroscience. 2010b;170:758–772. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter RJ. Melatonin: the chemical expression of darkness. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1991a;79:C153–158. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(91)90087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter RJ. Neuroendocrine effects of light. Int J Biometeorol. 1991b;35:169–175. doi: 10.1007/BF01049063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rihel J, Schier AF. Sites of action of sleep and wake drugs: insights from model organisms. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2013;23:831–840. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose S, Novak CM, Mahoney MM, Nunez AA, Smale L. Fos expression within vasopressin-containing neurons in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of diurnal rodents compared to nocturnal rodents. J Biol Rhythms. 1999;14:37–46. doi: 10.1177/074873099129000425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saderi N, Escobar C, Salgado-Delgado R. Alteration of biological rhythms causes metabolic diseases and obesity. Rev Neurologia. 2013;57:71–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado-Delgado R, Nadia S, Angeles-Castellanos M, Buijs RM, Escobar C. In a rat model of night work, activity during the normal resting phase produces desynchrony in the hypothalamus. J Biol Rhythms. 2010;25:421–431. doi: 10.1177/0748730410383403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper CB. Central autonomic system. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. 3rd edition Academic Press; New York: 2004. pp. 761–796. [Google Scholar]

- Saper CB, Loewy AD, Swanson LW, Cowan WM. Direct hypothalamo-autonomic connections. Brain Res. 1976;117:305–312. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90738-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer F, Ter Horst GJ, Van der Vliet J, Buijs RM. Physiological and anatomic evidence for regulation of the heart by suprachiasmatic nucleus in rats. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2001;280:H1391–H1399. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.3.H1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer F, van Doornen LJP, Buijs RM. Light and diurnal cycle affect human heart rate: Possible role for the circadian pacemaker. Journal of Biological Rhythms. 1999;14:202–212. doi: 10.1177/074873099129000614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer FA, Kalsbeek A, Buijs RM. Cardiovascular control by the suprachiasmatic nucleus: neural and neuroendocrine mechanisms in human and rat. Biological Chemistry. 2003;384:697–709. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MD, Smale L. Individual differences in rhythms of behavioral sleep and its neural substrates in Nile grass rats. J Biol Rhythms. 2005;20:526–537. doi: 10.1177/0748730405280924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smale L, Castleberry C, Nunez AA. Fos rhythms in the hypothalamus of Rattus and Arvicanthis that exhibit nocturnal and diurnal patterns of rhythmicity. Brain Res. 2001;899:101–105. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02205-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smale L, Cassone VM, Moore RY, Morin LP. Paraventricular nucleus projections mediating pineal melatonin and gonadal responses to photoperiod in the hamster. Brain Res Bull. 1989;22:263–9. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern JE. Electrophysiological and morphological properties of pre-autonomic neurones in the rat hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. The Journal of Physiology. 2001;537:161–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0161k.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, Kuypers HG. The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus: cytoarchitectonic subdivisions and organization of projections to the pituitary, dorsal vagal complex, and spinal cord as demonstrated by retrograde fluorescence double-labeling methods. J Comp Neurol. 1980;194:555–570. doi: 10.1002/cne.901940306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, Sawchenko PE. Paraventricular nucleus: a site for the integration of neuroendocrine and autonomic mechanisms. Neuroendocrinology. 1980;31:410–417. doi: 10.1159/000123111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LW, Sawchenko PE, Wiegand SJ, Price JL. Separate neurons in the paraventricular nucleus project to the median eminence and to the medulla or spinal cord. Brain Res. 1980;198:190–195. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90354-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teclemariam-Mesbah R, Ter Horst GJ, Postema F, Wortel J, Buijs RM. Anatomical demonstration of the suprachiasmatic nucleus-pineal pathway. J Comp Neurol. 1999;406:171–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdes JL, Sanchez C, Riveros ME, Blandina P, Contreras M, Farias P, Torrealba F. The histaminergic tuberomammillary nucleus is critical for motivated arousal. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;31:2073–2085. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivanco P, Ortiz V, Rol MA, Madrid JA. Looking for the keys to diurnality downstream from the circadian clock: role of melatonin in a dual-phasing rodent, Octodon degus. J Pineal Res. 2007;42:280–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh DK, Takahashi JS, Kay SA. Suprachiasmatic nucleus: cell autonomy and network properties. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:551–577. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhdanova IV. Melatonin as a hypnotic: pro. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9:51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]