Abstract

Over 100 broadly neutralizing antibodies have been isolated from a minority of HIV infected patients, but the steps leading to the selection of plasmacells producing such antibodies remain incompletely understood, hampering the development of vaccines able to elicit them. Rhesus macaques have become a preferred animal model system used to study SIV/HIV, for the characterization and development of novel therapeutics and vaccines as well as to understand pathogenesis. However, most of our knowledge about the dynamics of antibody responses is limited to the analysis of serum antibodies or monoclonal antibodies generated from memory B cells. In a vaccine setting, relatively little is known about the early cellular responses that elicit long-lived plasma cells and memory B cells and the tools to dissect plasmablast responses are not available in macaques. In the current study, we show that the majority (>80%) of the vaccine-induced plasmablast response are antigen-specific by functional ELISPOT assays. While plasmablasts are easily defined and isolated in humans, those same phenotypic markers have not been useful for identifying macaque plasmablasts. Here we describe an approach that allows for the isolation and single cell sorting of vaccine-induced plasmablasts. Finally, we show that isolated plasmablasts can be used to efficiently recover antigen-specific monoclonal antibodies through single cell expression cloning. This will allow detailed studies of the early plasmablast responses in rhesus macaques, enabling the characterization of both their repertoire breadth as well as the epitope specificity and functional qualities of the antibodies they produce, not only in the context of SIV/HIV vaccines but for many other pathogens/vaccines as well.

Keywords: Macaque plasmablasts, phenotype, sorting, monoclonal antibodies

Introduction

While more than 30 years has passed since the discovery of HIV as the etiology of AIDS, there is no efficient vaccine available yet. Initial efforts to develop a vaccine against HIV were directed towards generating antibody-mediated responses, but as the virus could readily escape from them, the HIV vaccine field turned largely in the direction of T cell-mediated vaccine development (reviewed by (Koup and Douek, 2011)). However, recent progress dissecting B cell responses in chronically HIV infected patients has led to the identification and analysis of several broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) that eventually develop in a small fraction of patients (reviewed by (West et al., 2014)). These antibodies display a remarkable breadth of neutralization, appear late in infection (reviewed by (Haynes et al., 2012) and are specific for several different epitopes of Env gp120 or gp41 (Walker et al., 2009). As a group, these bnAbs often share certain unusual attributes such as long CDR3 regions, extremely high levels of somatic hypermutation and polyreactivity against self and non-self antigens (Liao et al., 2011; West et al., 2014). These broadly neutralizing antibodies can prevent simian/human immunodeficiency (SHIV) virus infection in a macaque model after passive immunization (Hessell et al., 2009), and their therapeutic administration has been shown to reduce viral titers to undetectable levels, comparable to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) (Barouch et al., 2013; Shingai et al., 2013). Even though recent papers (Liao et al., 2013; Doria-Rose et al., 2014; Fera et al., 2014) have elegantly described the evolution of these broadly neutralizing antibodies in concert with the evolution of the virus, from the early to a late chronic stage of infection, it still remains an open question if and indeed how a vaccine can be designed that can induce similar responses.

In order to design novel vaccines that are able to induce B cell responses focused on the epitopes targeted by these broadly neutralizing antibodies, both new and improved immunogens are needed, as well as a better understanding of the early B cell responses induced by these novel vaccine candidates (Burton et al., 2012). One way to study these early B cell responses is through the use of antigen-probes designed to stain antigen-specific memory B cells (Scheid et al., 2009b; Franz et al., 2011; Kardava et al., 2014). This approach has proven to be very powerful in order to identify the bnAbs described above (Scheid et al., 2009a; Walker et al., 2011; Sundling et al., 2012a). Another attractive route to characterize the early B cell responses is through the analysis of plasmablasts appearing in the peripheral blood as a consequence of vaccination (Wrammert et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2011; Liao et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012) or infection, such as HIV (Doria-Rose et al., 2009; Liao et al., 2011), influenza (Wrammert et al., 2011), dengue (Wrammert et al., 2012), cholera (Rahman et al., 2013), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (Lee et al., 2010) and nosocomial bacteria (Band et al., 2014). During a recall response, human plasmablasts numbers peak around 7 days post-vaccination (Wrammert et al., 2008; Mei et al., 2009; Li et al., 2012) with a preference for IgG- or IgA-secreting cells, suggesting a memory B cell-derived origin. This notion is also supported by a very high level of somatic hypermutation in these cells. Furthermore, the magnitude of the plasmablast response has been shown to correlate directly with the induction of neutralizing antibody titers and thus the potential to clear infection (Balakrishnan et al., 2011; Nakaya et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012). Finally, since the majority of plasmablasts are antigen-specific at the peak of their response, they represent an excellent source of material to produce antigen-specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). The characterization of those mAbs in terms of repertoire breadth, binding affinity, epitope specificity and neutralizing activity provides a snapshot of the early ongoing antibody response at a single cell level (Wrammert et al., 2008; Wrammert et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2012; Nakamura et al., 2013).

Rhesus macaques have emerged as a major model for studies of HIV (or SIV and SHIV) pathogenesis, evaluation of novel therapeutics or antivirals, as well as for vaccine development (Hansen et al., 2013; Ling et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2013; Roederer et al., 2014). In addition, this model is widely used to investigate many other human pathogens as well as the efficacy of new vaccine candidates (reviewed by (Gujer et al., 2011)). Although several studies have evaluated B cells in animal models for HIV infection or vaccination, plasmablast responses in macaques remain poorly characterized, both in terms of the kinetics of their appearance after vaccination and suitable phenotypic markers to identify them. In one study, plasmablast responses could be detected by ELISPOT in macaque peripheral blood 7 days after vaccination, similar to what is observed in humans, however a detailed kinetic analysis was not performed (Sundling et al., 2010). Another publication showed that plasmablasts could be detected 2 weeks after booster immunization during ART treatment in macaques chronically infected with SIV (Demberg et al., 2012), however it is unclear how these results would translate into that of a vaccinated, non-infected host. In addition, a lack of suitable surface markers to identify and isolate functional, non-permeabilized plasmablasts in macaques, have hampered their further characterization. Finally, the relatively poor annotation of the macaque Ig locus, as compared to the human counterpart, has also been a major obstacle. However, recent progress has been made in annotating the macaque Ig locus and designing primers for amplification of macaque single cell Ig rearrangements (Sundling et al., 2012b) leading to an efficient isolation of CD4 binding site specific antibodies from macaques vaccinated with an HIV antigen (Sundling et al., 2014).

In this study, we characterize antigen-specific plasmablast responses in macaque peripheral blood after booster immunizations with SIV gp140 protein combined with a potent adjuvant that consists of poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) based nanoparticles (NP adjuvant) containing TLR4 and TLR7/8 agonists (MPL and R848), respectively (Kasturi et al., 2011). This vaccination induces a plasmablast response that appears rapidly, even earlier than in humans, and almost all these cells are antigen-specific. Phenotypic characterization of these vaccine-induced plasmablasts, in combination with cell sorting and functional readouts, allowed for their isolation as either bulk or single cells. The isolated bulk cells were used to confirm their phenotype by functional ELISPOT assays, while the single cells were used both for repertoire analysis and for generation of monoclonal antibodies. About half of the mAbs produced in this fashion were SIV gp140-specific, clearly illustrating the efficacy of this approach. The establishment of this technology for use in macaques will provide a novel tool for analysis of vaccine- or infection-induced plasmablast responses and a better understanding of the antibodies that these cells produce.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Animals and Immunizations

Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) of Indian origin were housed at Yerkes National Primate Research Center. The animals were cared for in conformance to the guidelines of the Committee on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals ((U.S.), 1996). All experimental protocols and procedures were reviewed and approved by the Emory Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Animals were immunized as previously described (Kasturi et al., 2011), with some minor modifications. Twenty milligrams of PLGA nanoparticles (Sigma Aldrich) containing 50µg of MPL (TLR 4 agonist; Avanti Polar Lipids) and 750µg of R848 (TLR 7/8 agonists; Enzo Life Sciences) were mixed with 50µg of SIV gp140 (Immune Technologies) and 50µg of recombinant SIV Gag (Protein Science) proteins, in a total volume of 1.5mL, and was administered subcutaneously in the vicinity of the popliteal lymph node of the right leg every 8 weeks for a total of 4 immunizations.

2.2. Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)

Peripheral blood was collected in CPT tubes containing sodium citrate (BD Vacutainer: REF362761) at different time points after immunizations from animals sedated with 10mg/Kg Ketamine administered i.m. Tubes were centrifugated at 1,600×g for 30 min at slow acceleration and deceleration at room temperature and plasma and PBMCs were collected. Remaining red blood cells (RBCs) in the PBMC preparation were lysed by incubation with ACK lysis buffer (Quality Biological) for 5 min at room temperature and washed with PBS 2% FBS solution 4–5 times. Cells were resuspended in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS and Penicillin/Streptomycin (1X) culture medium for ELISPOT assays or in PBS 2% FBS solution for cell staining.

2.3. ELISPOT assay

ELISPOT assays were performed as previously described (Wrammert et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2009), with some modifications. Briefly, ninety-six well multi-screen HTS filter plates (Millipore; MSHAN4B50) were coated with 10µg/mL of anti-monkey IgG, IgA, or IgM (H&L) goat antibody (Rockland) or with 2µg/mL of recombinant SIV gp140 or gag protein (Immune Technology Corp.) overnight at 4°C for enumeration of total or antigen-specific antibody secreting cells (ASCs) respectively. Wells were washed 4 times with PBS 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and 4 times with PBS, and blocked with complete RPMI medium (supplemented with 10% FBS Penicillin/Streptomycin) for 2 hours in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Whole PBMC preparations or PBMC-derived sorted cells were diluted in complete RPMI medium, plated in serial 3-fold dilutions and incubated overnight in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Wells were washed 4 times with PBS and 4 times with PBS-T, followed by incubation with either anti-monkey IgG-, IgA-, or IgM-biotin conjugated antibodies (Rockland), diluted 1:1000 in PBS-0.05% Tween 20 1% FBS solution (PBS-T-F), for 2 hours at room temperature. Wells were again washed 4 times with PBS-T before adding Avidin D-HRP (Vector labs) diluted 1:1000 in PBS-T-F. After a 3-hour incubation at room temperature, wells were washed 4 times with PBS-T and 4 times with PBS. Spots were developed with filtered 3-amino 9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) substrate (0.3mg/mL AEC diluted in 0.1M of sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0), containing a 1:1000 dilution of 3% hydrogen peroxide). To stop the reaction, wells were washed with water. Spots were documented and counted using the Immunospot CTL counter and Image Acquisition 4.5 software (Cellular Technology). Once counted, the number of spots specific for each Ig isotype was reported as the number of either total or antigen-specific ASCs per million PBMCs.

2.4. Analytical flow cytometry and cell sorting

Cell staining was essentially performed as previously described (Wrammert et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2009), with some modifications. For analytical flow cytometry, PBMCs were surface stained with a cocktail of antibodies for 30 minutes in the dark at 4°C, washed twice with PBS/2% FBS solution and re-suspended in 2% PFA. When appropriate, intracellular staining was done after surface staining. Cells were permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD) for 20 minutes at room temperature and washed twice with Perm wash buffer (BD). Antibodies for intracellular staining were added and incubation was performed for 30 minutes in the dark at 4°C. Cells were washed twice with Perm wash buffer and twice with PBS (1X), before re-suspension in 2% PFA solution.

For sorting of macaque plasmablasts, 25–50 million fresh PBMCs were surface stained with antibodies specific for the following surface markers (CD3, CD16, CD20, CD14, HLA-DR, CD11c, CD123 and CD80 (clone details - Table 1). These cells, defined here as CD3− CD16− CD20−/int HLA-DR+ CD14− CD11c− CD123− CD80+, were sorted in a two step-process. In the 1st step, the cells were enriched for CD80+, while the 2nd step was a high purity sort either as bulk cells, for subsequent functional assays, or as single cells into 96-well plates containing 10µL of RNAse-inhibitor/reverse transcription (RT)-PCR catch buffer (Smith et al., 2009). While bulk sorted cells were maintained on ice until utilization in ELISPOT assays, single cells were flash-frozen on dry ice and plates were immediately transferred to −80°C.

Table 1.

Antibodies used for analytical flow cytometry and/or cell sorting.

| Antigen | Clone | Fluorophore | Supplier | Staining | Reactivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD3 | SP-34-2 | AF700 | BD Pharmingen | Surface | Human |

| CD16 | 3G8 | AF700 | Biolegend | Surface | Human |

| CD20 | Leu-16 | PerCP | Becton Dickinson | Surface | Human |

| CD20 | L27 | V450 | BD Horizon | Surface | Human |

| HLA-DR | Tu36 | PE-TxR | Invitrogen | Surface | Human |

| CD14 | M5E2 | PE-Cy7 or V500 | BD Pharmingen | Surface | Human |

| CD11c | 3.9 | APC | Biolegend | Surface | Human |

| CD123 | 7G3 | PerCP-Cy5.5 | BD Pharmingen | Surface | Human |

| IgG | G18-145 | FITC / PE | BD Pharmingen | Intracellular | Human |

| CD80 | L307.4 | PE / Biotin | BD Pharmingen | Surface | Human |

| CD38 | AT-1 | FITC | Stem Cell Technologies | Surface | Human |

| CD19 | CB19 | PE | Abcam | Surface | Human |

| CD27 | M-T2T1 | APC | BD Horizon | Surface | Human |

| Ki67 | B56 | PE-Cy7 | BD Pharmingen | Intracellular | Human |

| CD29 | MAR4 | PE | BD Pharmingen | Surface | Human |

| CD49d | 9F10 | PE | Biolegend | Surface | Human |

| CD93 | VIMD2 | PE | Biolegend | Surface | Human |

| CD126 | PE | Beckman Coulter | Surface | Human | |

| CD138 | DL-101 MI15 |

PE PE |

eBioscience BD Pharmingen |

Surface Surface |

Human Human |

| PCA | VS38c | FITC | Dako | Intracellular | Human |

| Total Ig | Polyclonal | FITC | Rockland | Intracellular | Monkey |

| CD8 | RPA-T8 | APC | BD Pharmingen | Surface | Human |

| CD10 | HI10a | PE | BD | Surface | Human |

| Isotype IgG1 K | MOPC-21 | FITC / PE | BD Pharmingen | Surface | Mouse |

2.5. Isolation and cloning of single cell immunoglobulin V(D)J rearrangements from vaccine-induced plasmablasts

The entire antibody cloning process was divided in various sequential steps: cDNA production, nested PCR, sequencing of nested PCR products (search for cloning primers), cloning PCR, plasmid construction, bacteria transformation, plasmid sequencing (search for open reading frames (ORFs)), 293A cell transfection and mAb purification as previously described (Smith et al., 2009; Sundling et al., 2012a; Sundling et al., 2012b) with some modifications. For cDNA production, plates containing single sorted plasmablasts were thawed on ice and 1.5µL of 400µg/µL random hexamers (Invitrogen), 0.5µL of Sensiscript reverse transcriptase (Qiagen), 1.5µL of 10× buffer RT and 1.5µL of 5mM dNTP mix (Qiagen) were added per well, giving a final volume of 15 µL. cDNA synthesis was performed for 10 min at 25°C, 60 min at 37°C, 5 min at 95°C and cooling at 4°C according to the enzyme manufacturer instructions.

Using a multiplex nested PCR, either IgG, IgA or IgM heavy chain and kappa or lambda immunoglobulin (Ig) light chain fragments were amplified from the cDNA using primers recently described (Sundling et al., 2012b). The 1st round PCR mix was composed of 2µL of cDNA, 10µL of 2× HotStarTaq Plus Master mix (Qiagen), 0.5µL of outer primers (25µM and 20µM respectively for forward L1 and reverse primers), 0.5µL of 25mM MgCl2 (Promega) and 6.5µL of water, with a final reaction volume of 20µL per well. The 2nd round PCR mix contained the same basic reagents as the first one, except for the MgCl2 and PCR primers. Using less than 0.5µL of 1st round PCR product as template, inner primers (25µM and 20µM respectively for forward SE and reverse primers respectively) and water were added up to a total volume of 20µL. The PCR cycling conditions for both 1st and 2nd round PCRs as well as the primer sequences were the same as previously described (Sundling et al., 2012b), except that 40 cycles were performed instead of 50 for each amplification. Amplicons (nearly 500bp for heavy and 450bp for light Ig chains) were evaluated by electrophoresis in 1–1.2% agarose gels, purified using QIAquick spin columns (Qiagen) and sequenced using inner reverse primers (Sundling et al., 2012b).

Cloning PCRs were performed similar to the 2nd PCRs described above, but with cloning PCR primers (20µM) instead of inner primers. Their products were purified and digested with the following combination of restriction enzymes (Heavy – Age I HF / Sal I HF; Kappa – Age I HF / BsiWI; Lambda – Age I HF and Xho I) as recommended by the manufacturer (New England Biolabs). The cloning vectors used were PBR322-based Ab-Vec DNA plasmids: NCBI GenBank accession numbers: FJ475055 (heavy), FJ475056 (kappa) and FJ517647 (lambda). These vectors were digested with the same restriction enzymes as described above, purified using QIAquick spin columns (Qiagen) and dephosphorylated with Antarctic Phosphatase (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The ligations of digested cloning PCR products and vectors were performed with T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. XL-10-Gold competent bacteria (Agilent) were transformed with the ligation products by heat shock and individual colonies were grown in small scale using LB broth/ampicillin (0.1µg/mL) medium. Plasmids were isolated and sequenced to confirm identity with the original PCR fragment.

2.6. V(D)J gene family usage analysis

Sequencing data from the nested PCR products were analyzed with DNAStar softwares (SeqMan, EditSeq and MegAlign). To identify the V(D)J family genes usage from the sorted individual plasmablasts, the sequences were queried against rhesus macaque heavy Ig chain sequences or human kappa and lambda Ig chain sequences as previously reported (Sundling et al., 2012b) using the IMGT/V-Quest (Brochet et al., 2008; Giudicelli et al., 2011) and Joinsolver (Souto-Carneiro et al., 2004) softwares respectively.

2.7. Monoclonal antibody expression and purification

Heavy and light Ig chains-containing DNA plasmids from individual plasmablasts were amplified, purified (Qiagen Maxiprep) and used to transfect 293A cells as previously described (Smith et al., 2009). Antibody-containing supernatants of transfected cells were harvested after 4–5 days and purified with Protein A agarose beads (Pierce) packed in gravity flow chromatography columns. After running the supernatants, columns were washed with PBS and 1M NaCl solutions and mAbs were eluted with 0.1M Glycine (pH2.7). Eluted material was harvested in a 30K Amicon protein concentrator with Tris solution (pH9.0) for neutralization. Concentrated protein was buffer-exchanged twice in PBS by centrifugation for 30 min at 2,000×g. Protein was quantified using the Nanodrop 2000C spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and the quality of the produced mAbs (presence of heavy and light Ig chains) was verified by electrophoresis in mini-protean TGX gels (Biorad) under reducing conditions.

2.8. ELISA assay

Plasmablast-derived mAbs were evaluated using an SIV gp140-specific ELISA. One µg/mL of SIV gp140 (mac239) recombinant protein diluted in PBS was used to coat ELISA plates overnight at 4°C. Serial dilutions of the mAbs in PBS-0.2% Tween 20–10% FBS were tested, starting with a concentration of 10µg/mL. Peroxidase coupled affinipure F(ab')2 fragment goat anti-human IgG, Fc gamma fragment specific (Jackson Immunoresearch) was used for detection. Washing steps in between the antibody incubations were done with PBS-0.5% Tween 20. The substrate solution was prepared by dissolving 1 citrate buffer tablet (Sigma) per 10mL of water, followed by the addition of 1 OPD tablet (Life Technologies) and 40µL of 3% H2O2. The reaction was stopped after 5 min with 1N HCl solution (Fisher Scientific). Optical density (OD) values were determined using an iMark microplate reader (Biorad) with a 490nm filter. The minimum positive concentration of a mAb to bind the specific antigen was defined as a value 3 times higher than the OD observed with 10µg/mL of the Dengue-specific monoclonal antibody (31.3C04 - negative control).

3. Results

3.1. Potent antigen-specific plasmablast responses in immunized rhesus macaques

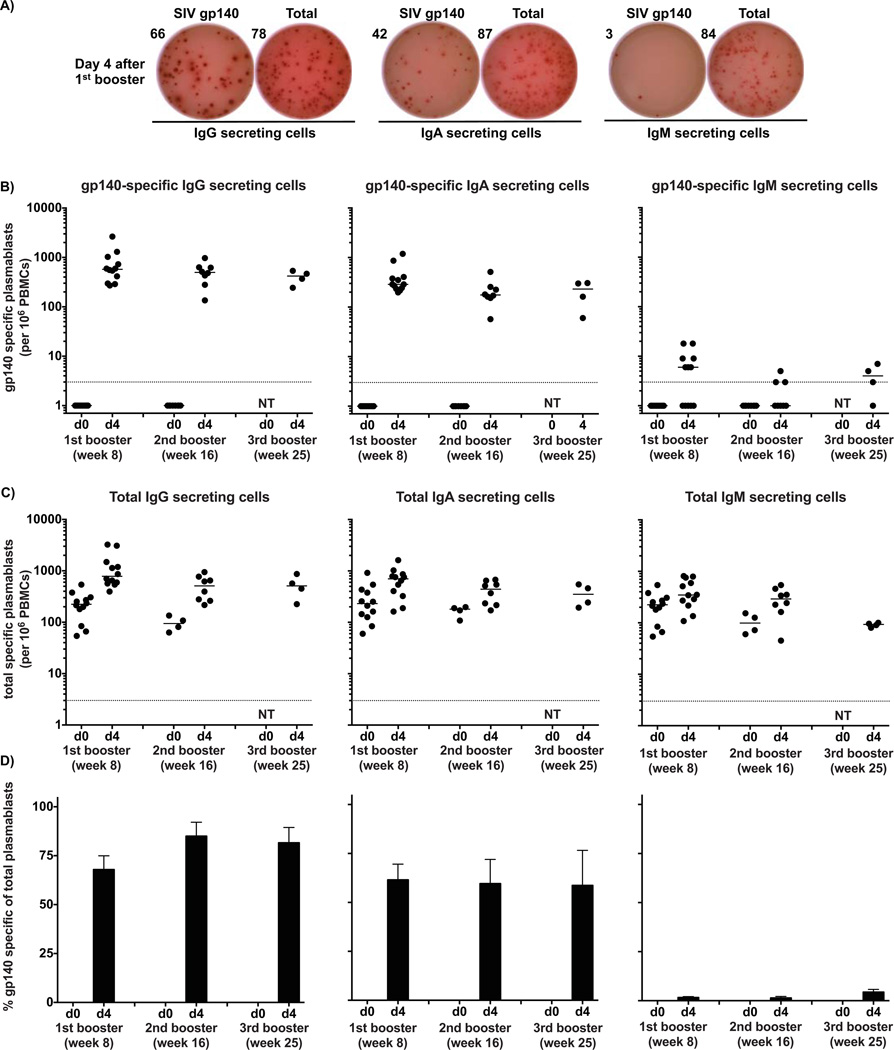

In order to characterize the dynamics of plasmablast responses in macaques, in terms of magnitude and isotype usage, we focused on animals vaccinated with four doses of SIV gp140 + gag proteins plus NP adjuvant. We concentrated our efforts on time points after the booster immunizations since the SIV gp140-specific plasmablast response was barely detected after the primary immunization (Wrammert & Kasturi et al. – unpublished personal communication; Sundling et al., 2010) and would thus not be a time point suitable for single cell expression cloning. Using ELISPOT assays as a readout of plasmablasts in the peripheral blood, we found that the booster responses were dominated by specific IgG- and IgA-secreting cells with very few IgM-secreting cells (Figure 1A). In contrast to what has previously been observed for recall responses in humans (Wrammert et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012), the magnitude of SIV gp140-specific plasmablast responses following a booster vaccination was significantly higher at day 4 than at day 7 in macaques (Supplemental Figure 1A and Kasturi SP et al. - manuscript in preparation), and thus our analyses below were focused on this time point. Similar kinetics have also been observed after immunization with different antigens and adjuvants in macaques (Supplemental Figure 1B and Kasturi SP et al. - manuscript in preparation), suggesting that this finding is not simply the effect of a particular adjuvant, but a general property of macaque recall responses.

Figure 1. Potent and rapid plasmablast responses in rhesus macaques after protein booster immunizations.

Macaques were immunized with SIV gp140 + gag proteins plus NP adjuvant and the antigen-specific plasmablast response was measured in the peripheral blood at different time points. A) A representative example of the ELISPOT assay results for SIV gp140-specific plasmablasts at day 4. The wells shown in the figure were plated with 1×105 PBMCs.

The magnitudes of SIV gp140-specific (B) and total (C) plasmablast response were measured at days 0 and 4 after booster immunizations for IgG, IgA and IgM-secreting cells. Data points represent the plasmablast numbers observed per million PBMCs and the bars represent the median. D) SIV gp140-specific responses expressed as percentage of total Ig-secreting cells for each Ig isotype respectively. Values represent the average percentage ± SEM of SIV gp140-specific plasmablasts for IgG, IgA and IgM of total Ig-secreting cells of same isotype. The experiment was initiated with 12 animals with 4 sacrificed after each booster vaccination, thus n=12 for 1st boost; n=8 for 2nd boost; n=4 for 3rd boost. NT=Not tested.

Based on the results above, we focused on characterizing the plasmablast response against SIV gp140 and gag protein in immunized macaques in more detail, focusing on day 4. Overall, there was an average of 771 (range 270–2646), 508 (range 135–972) and 404 (range 243–536) SIV gp140-specific IgG-secreting cells per million PBMCs after the first, second and third booster immunizations respectively (Figures 1B–C), similar to what we have observed in humans after influenza vaccination (Wrammert et al., 2008; Li et al., 2012). SIV gp140-specific IgA responses presented a lower magnitude than the IgG responses and SIV-gp140-specific IgM-secreting cells were barely detected after both booster vaccinations, similar to human recall responses. Interestingly, even though the magnitude of the SIV gp140-specific plasmablast response was similar after each booster vaccination, the number of antigen-specific plasmacells present in the bone marrow increased after each booster vaccination (Kasturi SP et al. - manuscript in preparation). In contrast to the potent gp140 specific responses detected, gag-specific plasmablast responses were often smaller by an order of magnitude or more (Supplemental figure 2). The frequency of SIV gp140-specific IgG-secreting cells represented 68%, 85% and 81% of the total number of IgG-secreting cells at day 4 after the first, second and third booster immunizations, respectively (Figure 1D). SIV gp140-specific IgA-secreting cells represented 62%, 60% and 59%, while SIV gp140-specific IgM-secreting cells accounted for less than 5% of total IgM-secreting cells. The high percentage of SIV gp140-specific plasmablasts early on in the immune response is important as it illustrates the feasibility of using the vaccine-induced cells to either study Ig repertoire usage or to use them as a source for generating mAbs, as detailed below.

3.2. Phenotypic characterization of vaccine-induced macaque plasmablasts

Plasmablasts have been carefully characterized and studied in humans. Well defined phenotypic markers used for the identification of these cells have allowed for a better understanding of the plasmablast role in immune responses after either immunization or infection (Wrammert et al., 2008; Blanchard-Rohner et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2011), both in terms of repertoire analysis as well as to dissect the ongoing response by generating and characterizing plasmablast-derived mAbs. These cells can be defined in humans as CD3− CD19+ CD20−/low CD27hi CD38hi cells (Wrammert et al., 2008; Doria-Rose et al., 2009). However, these markers did not translate into a useful approach for the analysis of macaque plasmablasts. In addition, the limited literature about the phenotype of macaque plasmablasts is generally derived from studies of animals chronically infected with SIV, which may differ from a vaccine response in naïve animals (Gujer et al., 2011; Demberg et al., 2012; Demberg et al., 2014).

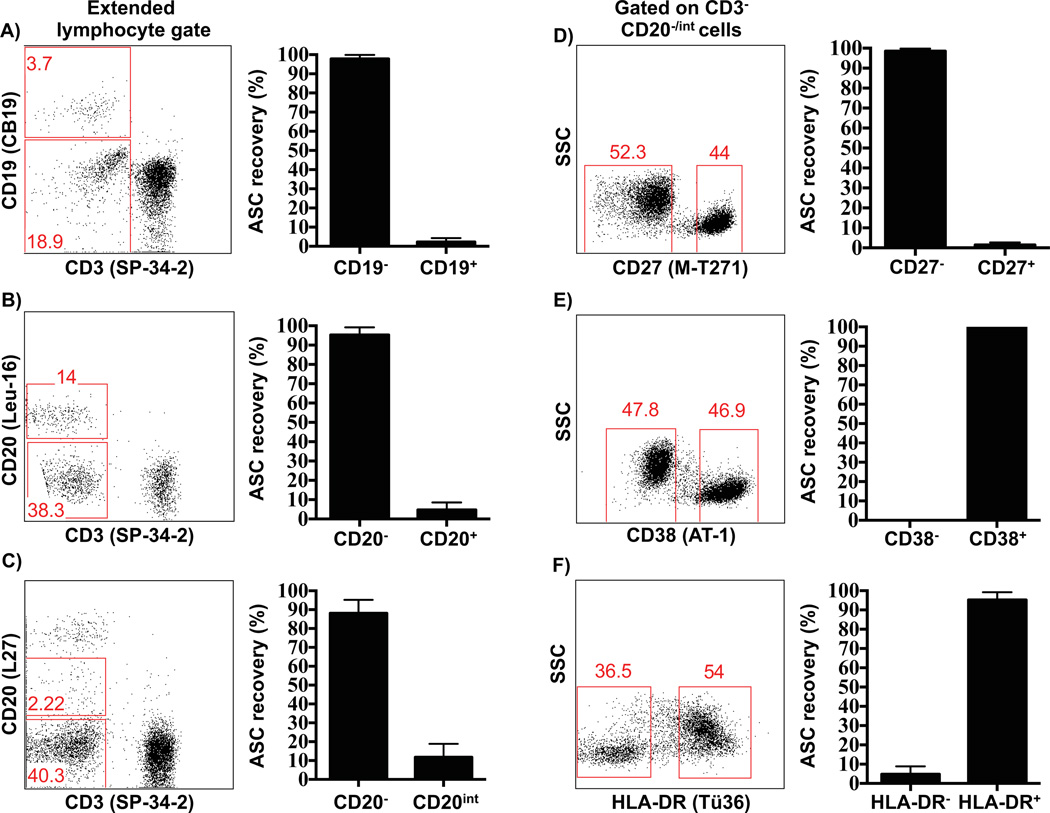

To phenotypically characterize plasmablasts in macaques, different populations of PBMCs were initially sorted from non-immunized animals (testing for Ig producing total baseline plasmablasts (Figure 1C)) based on the positive and negative expression of several human plasmablast markers, such as CD19, CD20, CD27, CD38 and HLA-DR. Sorted cells were tested by ELISPOT to determine which of these markers are expressed by antibody-secreting cells (IgG+, IgA+ or IgM+) in blood. Given the different size of the various cell subsets, these data are presented as a percentage of recovered ASC per population, rather than absolute numbers. These initial efforts clearly demonstrated that macaque plasmablasts are phenotypically distinct from their human counterparts (Figure 2). This analysis showed that macaque plasmablasts are primarily CD19−, since more than 95% of the ASC activity was recovered from the CD19− cells (Figure 2A). The expression of CD20 molecule in macaque plasmablasts matched that of human cells as they were mainly CD20−/low (Figures 2B–C). Although CD27 is a marker expressed by both macaque and human memory B cells and is highly upregulated on human plasmablasts, surprisingly, the macaque plasmablasts were CD27− with more than 95% of the ASC activity recovered from that cell subset (Figure 2D). Furthermore, macaque plasmablasts were also characterized as CD38+ (Figure 2E), although this marker was not discriminatory as it is expressed at similar high levels on other B cell subsets in macaques (Supplemental Figure 2B). HLA-DR+ was also expressed on macaque plasmablasts (Figure 2F), as previously described for their human counterpart (Wrammert et al., 2008) Other surface antigens tested were CD8 and CD10 and most of the ASC activity was recovered from CD8− or CD10− cells (data not shown).

Figure 2. Rhesus macaque plasmablasts are phenotypically distinct from their human counterpart.

Expression patterns of markers commonly used to distinguish human plasmablasts were tested on PBMCs of non-immunized macaques through cell sorting followed by ELISPOT analysis. PBMCs were stained with individual surface markers and sorted before being added to ELISPOT plates to track the antibody-secreting cells (ASCs). Representative flow cytometry data shows cells gated with an extended lymphocyte gate that includes blasting cells (A–C), or cells further sub-gated on CD3− CD20−/int cells (D–F). Cells were sorted based on the positive or negative expression of CD19 (A), CD20 (B and C), CD27 (D), CD38 (E) or HLA-DR (F) and subsequently tested by ELISPOT assay. Two different CD20 clones were used (B and C), since L27 (C) presented a higher resolution, allowing the gating for the CD20int cells. Antibody clones used for each staining are indicated in parentheses after each CD marker. Values represent the percentage average of total Ig-secreting plasmablasts recovered from each population ± SEM (right plots). Each experiment was repeated a minimum of two times with similar results.

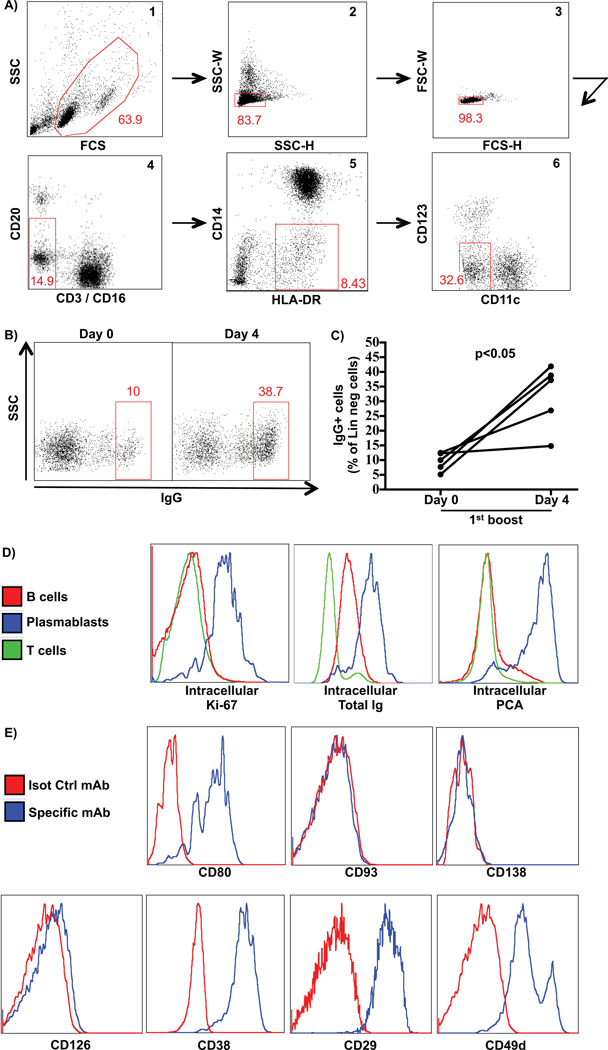

Since the traditional markers used for the characterization of human plasmablasts could not be readily used in macaques, we decided to define novel markers to identify these cells. For this, we designed a strategy to gate away most lineage positive markers, and then stain remaining HLA-DR+ cells for intracellular Ig. Thus we gated away B cells (CD20+), T cells (CD3+), monocytes (CD14+), plasmacytoid (CD123+) or myeloid dendritic cells (CD11c+) from a singlet lymphocyte gate, which was extended to include blasting cells and HLA-DR+ cells (Figure 3A). When the remaining cells were stained for intracellular IgG (icIgG), we found an average of 9% icIgG+ cells at the pre-vaccination baseline. This frequency increased to about 32% four days after vaccination (p<0.05), closely mirroring the fold increase of total Ig-secreting cells observed using whole PBMC ELISPOT assays (Figures 3B–C). Surface IgG staining on those gated cells showed no positive staining (data not shown), suggesting that these cells express little or no IgG on their surface, similar to human plasmablasts. To confirm that the vaccine-induced icIgG+ cells were indeed plasmablasts, these cells were also analyzed for human or mouse plasmablast- and plasmacell-associated markers such as intracellular Ki67 (Drach et al., 1992), total Ig and PCA (Jernberg et al., 1987). As expected, icIgG+ cells were uniformly Ki67+, as well as total Ig+ and PCA+ in contrast to either total B or T cells (Figure 3D), strongly supporting their plasmablast identity. In addition, icIgG+ cells were also CD19− and CD20−/low (data not shown), corroborating our previous ELISPOT data of sorted subsets (Figures 2A–C). We concluded that this gating strategy allowed us to capture total IgG secreting plasmablasts and that we could use this strategy to identify additional cell surface markers expressed on these cells, to allow the isolation of viable, non-permeabilized plasmablasts. Thus, we analyzed the icIgG+ plasmablasts for expression of several plasmablast- or plasmacell-associated surface antigens described in mice and/or humans, such as CD80 (Pelletier et al., 2010; Good-Jacobson et al., 2012), CD93 (Chevrier et al., 2009), CD138 (Sanderson et al., 1989; O'Connell et al., 2004; Demberg et al., 2012; Demberg et al., 2014), CD126 (Barille et al., 1999; Rawstron et al., 2000; Tarte et al., 2003; Gonzalez-Garcia et al., 2006), CD38 and the CD38-associated integrins CD29 and CD49d (Medina et al., 2002; Gonzalez-Garcia et al., 2006; Zucchetto et al., 2012). Among the markers tested, the icIgG+ cells stained positively for CD80, CD38, CD29 and CD49d and negatively for CD93, CD138 and CD126 (Figure 3E). Although the icIgG+ plasmablasts have a high expression of CD38, this molecule is broadly and uniformly expressed on many macaque cell types, including most of B cell subsets (Supplemental Figure 3B). This makes it less useful for defining the plasmablast subset in macaques. Since the CD49d/CD29 integrins have been described to be expressed as a protein complex physically and functionally associated with CD38 (Zucchetto et al., 2012), we decided not to pursue them for the current purpose. In contrast, CD80 is expressed on macaque as well as on human plasmablasts and with a better resolution than CD38 (Supplemental Figures 3A–B).

Figure 3. Phenotypic characterization of rhesus macaque plasmablasts.

A gating strategy to exclude lineage cells was designed and the remaining cells were analyzed for intracellular IgG. Subsequently, IgG+ cells were analyzed for several cell surface markers A) Representative flow cytometry data showing a sequential gating strategy to enrich for plasmablasts: 1) extended lymphocyte including blasting cells; 2–3) singlets; 4) CD3− CD16− CD20−/int cells; 5) HLA-DR+ CD14− cells and 6) CD11c− CD123− cells. B) Representative flow cytometry data of IgG intracellular staining after the sequential gating at days 0 and 4 of booster immunization. C) Percentage of IgG+ cells of the lineage negative cells (step 6 – right plot) (n=5) at days 0 and 4 after 1st boost immunization. D) Intracellular staining for plasmablast- or plasma cell-associated markers on plasmablasts (IgG+ gated cells), T or B cells from the same sample. E) Surface staining for plasmablast- or plasma cell-associated markers on IgG+ gated cells.

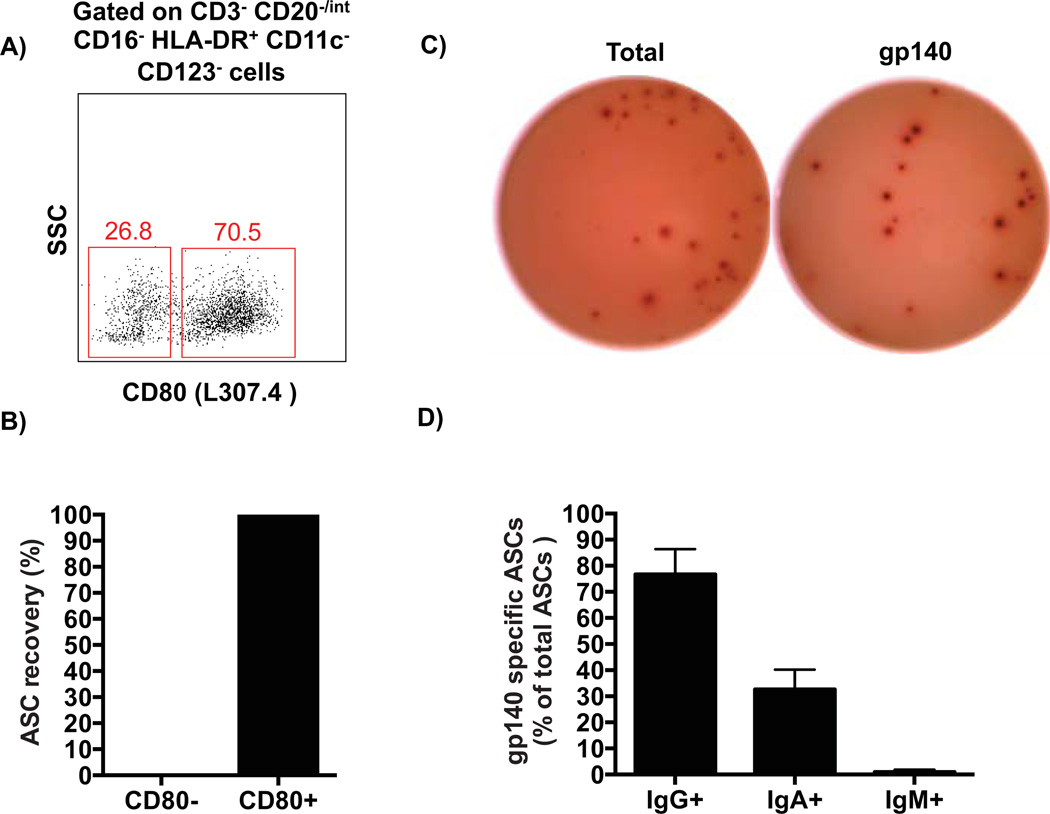

To confirm the findings from the intracellular analysis and determine whether CD80 could be a reliable surface marker to identify plasmablasts, CD80− or CD80+ cells were sorted (Figure 4A) from the negative lineage gate as described above, and tested for antibody secretion using an ELISPOT assay. All ASC activity was indeed observed within the CD80+ cells (Figure 4B) and thus, CD80 was used as a surface marker to identify and sort macaque plasmablasts. Based on these findings, both bulk and single plasmablasts were sorted at day 4 after vaccination from several animals. As expected, the sorted cells largely mirrored the high frequency of antigen-specific cells observed in whole PBMCs, with 79 ± 27% (average ± SD) of the total IgG-secreting plasmablasts being SIV gp140-specific (Figures 4C–D). Therefore, we concluded that CD80 and HLA-DR positive expression combined with a lineage negative gate can be used to isolate vaccine-induced plasmablasts in macaques (defined herein as CD3− CD16− CD20−/int HLA-DR+ CD14− CD11c− CD123− CD80+ cells).

Figure 4. Functional confirmation of plasmablast phenotype in rhesus macaques.

A) Representative flow cytometry data showing CD80 expression after the sequential gating described in Figure 3 for plasmablasts. Cells were sorted based on the positive or negative expression of CD80 and tested by ELISPOT assay. The antibody clone used for CD80 staining is indicated in the parenthesis. B) Percentage of total Ig-secreting plasmablasts recovered from each population as assayed by ELISPOT. C) Representative ELISPOT data shows that the majority of sorted IgG-secreting plasmablasts were SIV gp140-specific in the immunized animals. D) Percentage (average ± SEM) of gp140-specific plasmablasts over total Ig-secreting cells for each isotype at day 4 after boost immunizations (n=7).

3.3 Generation of monoclonal antibodies from single plasmablasts

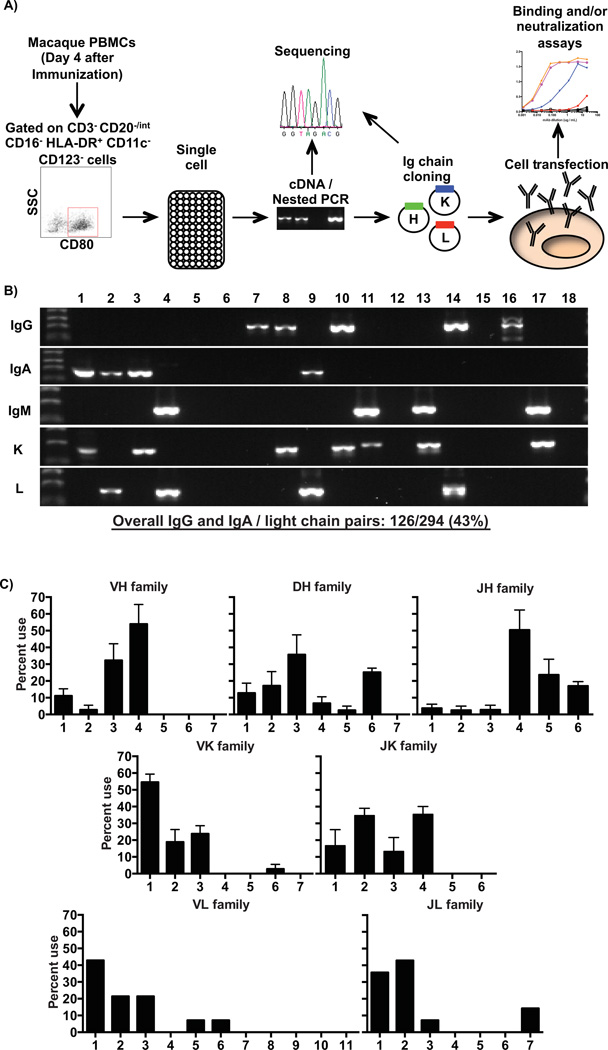

In order to identify macaque Ig rearrangements from individual sorted plasmablasts, we used a similar approach to what was recently described to study antigen-specific memory B cell responses in HIV vaccinated macaques combined with our previous methodology established in humans. Although the macaque Ig locus remains relatively poorly annotated, the single cell primer sets used here allow for adequate coverage of all variable (V) gene families (Sundling et al., 2012b). Single cell plasmablasts were collected and frozen on day 4 after booster immunization from a total of 4 animals and were used to generate cDNA. Subsequently, the cDNAs were used as templates in multiplex nested PCRs with macaque Ig chains-specific primers (Figure 5A) as previously described (Sundling et al., 2012b). Overall, heavy Ig chain amplicons (IgG+ or IgA+ only) were obtained from an average of 54% of the wells. Matching the ELISPOT data with total PBMCs outlined above (Figure 1), the highest amplicon frequency was observed for IgG heavy chain fragments (58% of heavy Ig chain amplicons). Although IgM amplicons could also be detected from sorted individual plasmablasts (Figure 5B) at low frequencies, they were excluded from the analysis. Light chain Ig amplicons (kappa or lambda) were detected from 58% of the analyzed cells, with a slight predominance for kappa chain (60% of overall light chain amplicons). Finally, cognate pairs of heavy and light amplicons were observed from 43% of the tested cells (Figure 5B). Given that the IgG+ cells contained the highest frequency of antigen-specific cells (Figure 4D), we focused our analysis on these cells for the repertoire analysis and the generation of mAbs.

Figure 5. Single cell antibody cloning and repertoire analysis of rhesus macaque plasmablasts.

A) Outline of the strategy used to sort plasmablasts and produce specific monoclonal antibodies from individual cells. At day 4 after booster immunization, plasmablasts were sorted into 96-well plates containing lysis buffer. Single cell cDNA was prepared and used as template for multiplex nested PCR to identify individual Ig rearrangements. Each rearrangement was cloned and expressed in 293A cells by transient transfection. Finally, the produced mAbs were tested for binding to the vaccine antigen by ELISA. B) Example of a single experiment, chosen to illustrate all possible heavy and light chain re-arrangements that can be detected in the single cell RT-PCR from individual sorted plasmablasts. Overall, 43% of all the analyzed wells gave cognate heavy and light chain pairs of either IgG or IgA. C) V(D)J gene family usage from sorted IgG-secreting plasmablasts of rhesus macaques. A total of 66 heavy and 37 kappa sequences were analyzed from 4 rhesus macaques, while 14 lambda sequences were inspected from a single animal. Sequences were evaluated with IMGT-V/Quest (heavy chain) and Joinsolver (kappa and lambda chains) softwares. Values represent average ± SEM (heavy and kappa chains) or average (lambda chain).

To investigate the Ig repertoire breadth of vaccine-induced sorted total plasmablasts, we analyzed the V(D)J or VJ gene family usage of all paired sequences between IgG heavy and light chains respectively from 4 rhesus macaques. For this analysis, amplicon sequences were queried against rhesus macaque (IMGT-V/Quest database for heavy Ig chain - http://www.imgt.org/IMGT_vquest/vquest?livret=0&Option=macacaIg) or human (Joinsolver database for light Ig chains - http://joinsolver.niaid.nih.gov) databases. A total of 66 heavy, 37 kappa and 14 lambda sequences from IgG amplicons of 4 animals were analyzed. The frequency of heavy Ig chain V(D)J genes was similar in all animals and predominantly used either VH4 or VH3, with a smaller number using VH1 rearrangements. These V genes were predominantly re-arranged with JH4, JH5 or JH6 segments. Interestingly, similar results were also observed for IgA-secreting plasmablasts (Supplemental Figure 4). For the light Ig chains, the most prevalent genes were VK1 and VL1, rearranged with J2 or J4 and J2 or J1, respectively (Figure 5C). This pattern of V(D)J or VJ gene family usage by the total IgG+ plasmablasts was very similar to the one showed by naïve and memory B cells and HIV specific-memory B cells recently described (Sundling et al., 2012a; Sundling et al., 2012b). Furthermore, in contrast to what has been observed in humans (Wrammert et al., 2008), this preliminary analysis showed no evidence of a clonally restricted repertoire (data not shown).

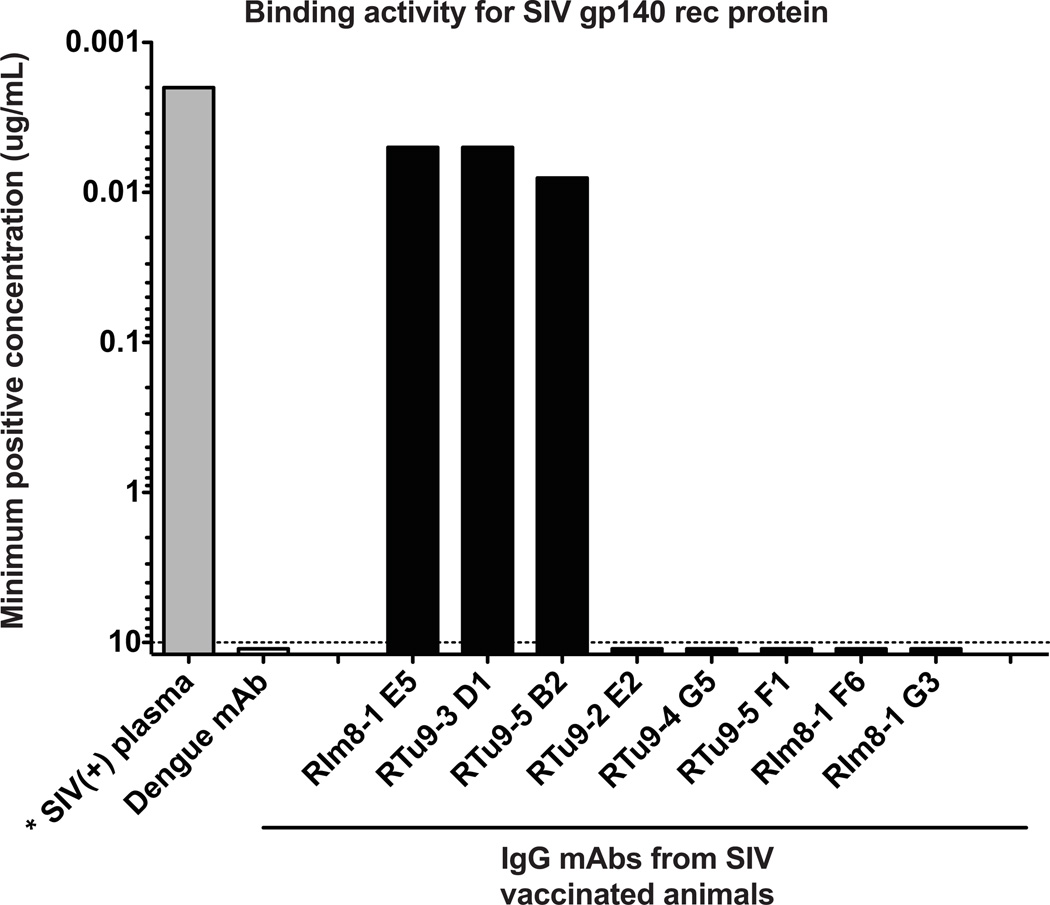

As a proof of concept that the isolated Ig rearrangements from individual plasmablasts could be used as a source of mAbs, allowing a snapshot insight into the ongoing immune responses, a small number of paired V(D)J or VJ sequences from heavy and light IgG chains of macaque plasmablasts were cloned into human antibody expression vectors as previously described (Wrammert et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2009; Sundling et al., 2012b). After co-transfection in 293A cells of these vectors, 8 chimeric IgG mAbs were successfully produced from two macaques vaccinated with SIV gp140 plus NP adjuvant. The minimal effective concentration value for binding against the same SIV gp140 protein utilized as vaccine immunogen was determined for these mAbs using an ELISA assay (Figure 6). Those values represent the antibody concentration that scored three times the baseline signal against SIV gp140 protein by a negative control, dengue-specific mAb. Three out of the eight mAbs bound to the SIV gp140 protein, with minimal effective concentration values of less then 0.01µg/ml. These results illustrate that the approach outlined above can be efficiently utilized to isolate antigen-specific plasmablasts and that these isolated cells can be used for the generation and characterization of antigen-specific mAbs.

Figure 6. Plasmablast-derived monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) isolated from immunized macaques display binding activity against SIV gp140 recombinant protein.

mAbs were produced from individual sorted plasmablasts of 2 macaques immunized with SIV gp140 protein plus NP adjuvant and subsequently tested for binding to the vaccine antigen by ELISA. Values represent the minimum positive concentration of the antibodies (Background: > 3 times the OD of the lowest dilution for a negative control antibody (Dengue mA b).

4. Discussion

The identification of broadly neutralizing antibodies in a subset of chronically infected and viremic HIV patients has led to renewed interest in B cell biology in this disease. Overall, this new focus has led to several major technological advances in the field, allowing for the analysis of B cell responses both at a cellular and a single cell level, at an unprecedented level of resolution. The use of these novel broadly neutralizing antibodies for therapeutic or prophylactic purposes have shown great promise in animal models (Hessell et al., 2009; Barouch et al., 2013; Shingai et al., 2013) and major efforts are now being brought towards designing novel vaccines able to induce this type of antibody response. Understanding the early immune responses induced by these novel vaccine candidates is essential for developing and optimizing this type of highly targeted vaccines.

Non-human primates are an important model system for evaluating novel experimental vaccines or prophylactic and therapeutic interventions for HIV/SIV/SHIV infection as well as for several other pathogens. Although some cellular aspects of the B cell response have been explored in this animal model, little information is available about the plasmablast response after infection or vaccination. Many of the tools routinely used to dissect human B cell responses have only recently begun to be adapted for use in macaques. Although these cells can readily be detected by functional assays like ELISPOT, neither their kinetics nor their phenotype have been analyzed in detail after immunization. Moreover, these cells have not been used for the generation and analysis of mAbs, as demonstrated using human samples.

The isolation of individual human plasmablasts has allowed for the development of technologies to efficiently produce mAbs against different antigens. Together with studies of memory B cell responses, significant differences between the antibody repertoires of memory B cells and acutely induced plasmablasts have been outlined (Wrammert et al., 2008; Wrammert et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2012). Thus, a detailed comprehension of the ongoing immune response generated in both compartments is needed to understand the mechanisms that elicit protective immunity after infection or vaccination.

In the current study, we find very potent plasmablast responses for which the majority of the cells are antigen-specific, and dominated by IgG and IgA secreting cells. These responses occur earlier than in humans, and thus we focused our analyses on day 4 post-vaccination (Supplemental Figure 1A and Kasturi SP et al. - manuscript in preparation). Earlier studies of vaccine-induced HIV-specific plasmablast response in macaques may have underestimated the overall magnitude, as these responses were evaluated 7 days after vaccination (Sundling et al., 2010). Other studies analyzed vaccine-induced plasmablast responses in a chronic infection setting after antiretroviral therapy (ART) (Demberg et al., 2012) or SIV infection-induced plasmablasts/plasmacells (Demberg et al., 2014). A direct comparison between chronic SIV infection and vaccination of healthy animals herein is difficult. This highlights the importance of kinetic analyses and may impact the design and timing of samplings in future vaccine studies conducted in macaques. The high frequency of antigen-specific plasmablasts illustrates that the generation and analysis of plasmablast-derived mAbs in macaques is quite feasible.

An important contribution of this study is the characterization of a macaque plasmablast phenotype. Earlier attempts to characterize plasmablasts in macaques have been reported, but those studies were not confirmed by functional antibody-secretion activity or were based only on intracellular staining (Gujer et al., 2011; Demberg et al., 2012; Demberg et al., 2014). Furthermore, these studies were largely done in a chronic viral infection setting, where it would be difficult to differentiate between an acutely induced plasmablast, and a previously generated plasmacell. Our initial experiments characterized the expression patterns of the markers used to identify human plasmablasts. This analysis showed that those markers could not readily be used to identify macaque plasmablasts. The most striking differences were observed for CD19 and CD27 expression levels (Figures 2A and 2D). While human plasmablasts express high levels of both markers, macaque plasmablasts were negative for both. In contrast to our findings here, recent studies described that both macaque bone marrow and intestinal plasmacells express CD19 on the cell surface (Demberg et al., 2012; Demberg et al., 2014). In humans, both CD19+ and CD19− subsets of bone marrow-derived plasmacells can be identified (Szyszko et al., 2011) (Frances Eun-Hyung Lee; unpublished personal communication), and it is currently unclear if the discrepancy observed here is simply due to differences between the reagents used or if there is a difference in CD19 expression based on the location of the cell, the presence/absence of chronic infection, or a difference between plasmablasts and plasma cells. In addition, macaque plasmablasts were CD20−/low, and although they were CD38+ (Figures 2B–C and 2E), so are other B cell subsets (Supplemental Figure 3B), thereby limiting their usefulness for isolating macaque plasmablasts.

In order to enrich for macaque plasmablasts we used a different approach, based on initial exclusion of multiple cell subsets, including B and T cells, monocytes, macrophages, plasmacytoid and myeloid dendritic cells (Figure 3A). In addition, we also used the expression of HLA-DR on the plasmablasts for this panel and the remaining cells were stained for intracellular IgG (icIgG). This strategy allowed us to identify a population of icIgG+ cells that increased significantly in numbers on day 4 after vaccination (Figures 3B–C). The identity of these icIgG+ cells was confirmed by their expression of Ki67 and the plasma cell antigen PCA (Figure 3D). Because viable non-permeabilized plasmablasts are required both for functional characterization as well as single cell expression cloning, we used the above strategy to identify additional surface antigens that could be used for their purification (Figure 3E). Among those markers, CD138 is a commonly used human plasmacell marker, but has been shown to not be expressed at all, or only on a subset of human plasmablasts in the peripheral blood (Qian et al., 2010). Recently, this marker was shown to be expressed on bone marrow and mucosal plasmacells, as well as on blood plasmablasts in SIV infected macaques after staining with the clone DL-101 of anti-human CD138 antibody (Demberg et al., 2012; Demberg et al., 2014). However, we did not observe CD138 expression on vaccine-induced, blood borne plasmablasts after staining with the same clone above or with clone MI15 (Table 1). For the reasons above we did not pursue this marker further. Finally, CD80 was found to be highly expressed on plasmablasts. This marker has been described as a regulator of germinal center development as well as antibody-forming cells in mice (Pelletier et al., 2010; Good-Jacobson et al., 2012) and is expressed on human and macaque plasmablasts (Supplemental Figures 2A–B). Based on the above findings we decided to use the phenotype CD3− CD16− CD20−/int HLA-DR+ CD14− CD11c− CD123− CD80+ to define macaque plasmablasts.

To confirm this phenotype and ensure that a majority of the isolated cells remained functional, sorted cell were used to enumerate ASCs, again by ELISPOT assays. In those functional experiments, we could account for 30–50% of the sorted ASCs. The fact that we cannot account for all of the sorted cells, we ascribe primarily to loss of function during the 2-step sorting process. Among the cells that produced detectable amounts of antibody, we found that almost all of the IgG-secreting cells were antigen-specific (Figure 4). This is similar to what was observed in total PBMCs, confirming the phenotype we had defined above as well as the utility of these cells as a reliable source for single cell expression cloning. In addition, single cell immunoglobulin re-arrangements were obtained from about 60% of the sorted cells using multiplex nested RT-PCR (Figure 5B). The amplification efficiency was similar to what we and others have observed with sorted human plasmablasts or macaque B cells (Tiller et al., 2008; Wrammert et al., 2008; Sundling et al., 2012b). Overall, the percentage of cells for which paired single heavy (IgG or IgA) and light Ig chain amplicons were successfully obtained (43%) was also equivalent to earlier experiences with human (Tiller et al., 2008; Wrammert et al., 2008) and macaque samples (Sundling et al., 2012a; Sundling et al., 2012b). The remaining single cells represent either IgM-secreting cells (Figure 1A) or cells for which only a heavy chain, only a light chain or no re-arrangement could be detected.

The paired IgG re-arrangements obtained from the sorted plasmablasts were evaluated in terms of the V(D)J gene family usage. Plasmablast-derived Ig sequences showed a similar V(D)J family gene usage (Figure 5C) compared to published data obtained from total B cells (Sundling et al., 2012b), and total HIV-specific or CD4bs-specific cells (Sundling et al., 2012a), for both heavy and light Ig chains. The human plasmablast responses observed after influenza vaccination have been shown to be clonally restricted (Wrammert et al., 2008). However, a preliminary analysis of the relatively small number of macaque plasmablast sequences generated herein showed no evidence of clonally related cells, perhaps due to the nature of the antigen and epitope dominance. This analysis will need to be done on larger numbers of sequences and donors, and be limited to only the sequences that encode vaccine-specific antibodies. Since more than 75% of the sorted IgG+ cells were antigen-specific by ELISPOT assays, it does suggest that the envelope-specific responses seen here after vaccination are less clonally restricted than what is observed in humans after influenza vaccination.

As a proof of concept, we expressed a handful of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) from the paired heavy and light chain PCR amplicons. After purification of the antibodies expressed through transient co-transfection, they were tested for binding affinity against the vaccine antigen, SIV gp140. Three out of eight antibodies, produced from 2 different animals, recognized the antigen with high affinity (Figure 6). This reactivity was SIV specific since none of the antibodies recognized the HIV gp140 protein (data not shown). The frequency of recombinant antigen-specific mAbs isolated seems somewhat lower than what was observed in the starting PBMC samples, however this is based on very small numbers of antibodies. True estimates of cloning efficacies will require many more antibodies from multiple donors. This initial proof-of-principle experiment does however clearly illustrate that this is a viable and efficient approach to isolate and subsequently analyze monoclonal antibodies from acutely induced plasmablasts after vaccination or infection in macaques. This technique will allow the efficient generation and subsequent analysis of antibody panels representing an unselected “snapshot” of the ongoing immune response. We are currently generating large panels of SIV-specific antibodies derived from several different vaccine studies, and are also expanding these tools to also include analysis of plasmablasts or plasmacells in both lymphoid and mucosal tissues. The characterization of these antibodies in terms of binding affinity, potency, breadth and neutralizing capability will shed light not only on how the B cell response is mounted after vaccination in non-human primates, but may also provide important insights towards the development of an efficient vaccine against HIV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to the Yerkes veterinary and Research Resource personnel for providing excellent technical assistance and all the colleagues in the Emory SIV B cell consortium. Grant support was provided from NIH grant U19-AI096187, Consortium for AIDS vaccine research in nonhuman primates (CAVR-NHP): “B-cell Biology of Mucosal Immune Protection from SIV Challenge”, with Eric Hunter and Rama Rao Amara as co-Principal investigators as well as the base grant to the Yerkes National Primate Research Center OD 51POD1113.

We are thankful for expert assistance with the cell sorting needs for this manuscript, provided by the Emory Vaccine Center sorter facility (Kiran Gill and Barbara Cervasi) and the Emory School of Medicine cell sorter facility (Robert Karaffa and Sommer Durham)

We thank Robert Kauffmann for discussions and critical reading of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

There were no competing financial interests among all authors.

References

- (U.S.), I.o.l.a.r. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan T, Bela-Ong DB, Toh YX, Flamand M, Devi S, Koh MB, Hibberd ML, Ooi EE, Low JG, Leo YS, Gu F, Fink K. Dengue virus activates polyreactive, natural IgG B cells after primary and secondary infection. PloS one. 2011;6:e29430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Band VI, Ibegbu C, Kaur SP, Cagle SM, Trible R, Jones CL, Wang YF, Kraft CS, Ray SM, Wrammert J, Weiss DS. Induction of human plasmablasts during infection with antibiotic-resistant nosocomial bacteria. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2014;69:1830–1833. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barille S, Thabard W, Robillard N, Moreau P, Pineau D, Harousseau JL, Bataille R, Amiot M. CD130 rather than CD126 expression is associated with disease activity in multiple myeloma. British journal of haematology. 1999;106:532–535. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barouch DH, Whitney JB, Moldt B, Klein F, Oliveira TY, Liu J, Stephenson KE, Chang HW, Shekhar K, Gupta S, Nkolola JP, Seaman MS, Smith KM, Borducchi EN, Cabral C, Smith JY, Blackmore S, Sanisetty S, Perry JR, Beck M, Lewis MG, Rinaldi W, Chakraborty AK, Poignard P, Nussenzweig MC, Burton DR. Therapeutic efficacy of potent neutralizing HIV-1-specific monoclonal antibodies in SHIV-infected rhesus monkeys. Nature. 2013;503:224–228. doi: 10.1038/nature12744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard-Rohner G, Pulickal AS, Jol-van der Zijde CM, Snape MD, Pollard AJ. Appearance of peripheral blood plasma cells and memory B cells in a primary and secondary immune response in humans. Blood. 2009;114:4998–5002. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochet X, Lefranc MP, Giudicelli V. IMGT/V-QUEST: the highly customized and integrated system for IG and TR standardized V-J and V-D-J sequence analysis. Nucleic acids research. 2008;36:W503–W508. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton DR, Ahmed R, Barouch DH, Butera ST, Crotty S, Godzik A, Kaufmann DE, McElrath MJ, Nussenzweig MC, Pulendran B, Scanlan CN, Schief WR, Silvestri G, Streeck H, Walker BD, Walker LM, Ward AB, Wilson IA, Wyatt R. A Blueprint for HIV Vaccine Discovery. Cell host & microbe. 2012;12:396–407. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevrier S, Genton C, Kallies A, Karnowski A, Otten LA, Malissen B, Malissen M, Botto M, Corcoran LM, Nutt SL, Acha-Orbea H. CD93 is required for maintenance of antibody secretion and persistence of plasma cells in the bone marrow niche. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:3895–3900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809736106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demberg T, Brocca-Cofano E, Xiao P, Venzon D, Vargas-Inchaustegui D, Lee EM, Kalisz I, Kalyanaraman VS, Dipasquale J, McKinnon K, Robert-Guroff M. Dynamics of memory B-cell populations in blood, lymph nodes, and bone marrow during antiretroviral therapy and envelope boosting in simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac251-infected rhesus macaques. Journal of virology. 2012;86:12591–12604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00298-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demberg T, Mohanram V, Venzon D, Robert-Guroff M. Phenotypes and distribution of mucosal memory B-cell populations in the SIV/SHIV rhesus macaque model. Clin Immunol. 2014;153:264–276. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doria-Rose NA, Klein RM, Manion MM, O’Dell S, Phogat A, Chakrabarti B, Hallahan CW, Migueles SA, Wrammert J, Ahmed R, Nason M, Wyatt RT, Mascola JR, Connors M. Frequency and phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus envelope-specific B cells from patients with broadly cross-neutralizing antibodies. Journal of virology. 2009;83:188–199. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01583-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doria-Rose NA, Schramm CA, Gorman J, Moore PL, Bhiman JN, DeKosky BJ, Ernandes MJ, Georgiev IS, Kim HJ, Pancera M, Staupe RP, Altae-Tran HR, Bailer RT, Crooks ET, Cupo A, Druz A, Garrett NJ, Hoi KH, Kong R, Louder MK, Longo NS, McKee K, Nonyane M, O’Dell S, Roark RS, Rudicell RS, Schmidt SD, Sheward DJ, Soto C, Wibmer CK, Yang Y, Zhang Z, Mullikin JC, Binley JM, Sanders RW, Wilson IA, Moore JP, Ward AB, Georgiou G, Williamson C, Abdool Karim SS, Morris L, Kwong PD, Shapiro L, Mascola JR, Becker J, Benjamin B, Blakesley R, Bouffard G, Brooks S, Coleman H, Dekhtyar M, Gregory M, Guan X, Gupta J, Han J, Hargrove A, Ho SL, Johnson T, Legaspi R, Lovett S, Maduro Q, Masiello C, Maskeri B, McDowell J, Montemayor C, Mullikin J, Park M, Riebow N, Schandler K, Schmidt B, Sison C, Stantripop M, Thomas J, Thomas P, Vemulapalli M, Young A. Developmental pathway for potent V1V2-directed HIV-neutralizing antibodies. Nature. 2014;509:55–62. doi: 10.1038/nature13036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drach J, Gattringer C, Glassl H, Drach D, Huber H. The biological and clinical significance of the KI-67 growth fraction in multiple myeloma. Hematological oncology. 1992;10:125–134. doi: 10.1002/hon.2900100209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fera D, Schmidt AG, Haynes BF, Gao F, Liao HX, Kepler TB, Harrison SC. Affinity maturation in an HIV broadly neutralizing B-cell lineage through reorientation of variable domains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409954111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz B, May KF, Jr, Dranoff G, Wucherpfennig K. Ex vivo characterization and isolation of rare memory B cells with antigen tetramers. Blood. 2011;118:348–357. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-341917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giudicelli V, Brochet X, Lefranc MP. IMGT/V-QUEST: IMGT standarized analysis of the immunoglobulin (IG) and T cell receptor (TR) nucleotide sequences. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;2011:695–715. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Garcia I, Ocana E, Jimenez-Gomez G, Campos-Caro A, Brieva JA. Immunization-induced perturbation of human blood plasma cell pool: progressive maturation, IL-6 responsiveness, and high PRDI-BF1/BLIMP1 expression are critical distinctions between antigen-specific and nonspecific plasma cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:4042–4050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good-Jacobson KL, Song E, Anderson S, Sharpe AH, Shlomchik MJ. CD80 expression on B cells regulates murine T follicular helper development, germinal center B cell survival, and plasma cell generation. J Immunol. 2012;188:4217–4225. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujer C, Sundling C, Seder RA, Karlsson Hedestam GB, Lore K. Human and rhesus plasmacytoid dendritic cell and B-cell responses to Toll-like receptor stimulation. Immunology. 2011;134:257–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03484.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen SG, Piatak M, Jr, Ventura AB, Hughes CM, Gilbride RM, Ford JC, Oswald K, Shoemaker R, Li Y, Lewis MS, Gilliam AN, Xu G, Whizin N, Burwitz BJ, Planer SL, Turner JM, Legasse AW, Axthelm MK, Nelson JA, Fruh K, Sacha JB, Estes JD, Keele BF, Edlefsen PT, Lifson JD, Picker LJ. Immune clearance of highly pathogenic SIV infection. Nature. 2013;502:100–104. doi: 10.1038/nature12519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes BF, Kelsoe G, Harrison SC, Kepler TB. B-cell-lineage immunogen design in vaccine development with HIV-1 as a case study. Nature biotechnology. 2012;30:423–433. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessell AJ, Poignard P, Hunter M, Hangartner L, Tehrani DM, Bleeker WK, Parren PW, Marx PA, Burton DR. Effective, low-titer antibody protection against low-dose repeated mucosal SHIV challenge in macaques. Nature medicine. 2009;15:951–954. doi: 10.1038/nm.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernberg H, Nilsson K, Zech L, Lutz D, Nowotny H, Scheirer W. Establishment and phenotypic characterization of three new human myeloma cell lines (U-1957, U-1958, and U-1996) Blood. 1987;69:1605–1612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardava L, Moir S, Shah N, Wang W, Wilson R, Buckner CM, Santich BH, Kim LJ, Spurlin EE, Nelson AK, Wheatley AK, Harvey CJ, McDermott AB, Wucherpfennig KW, Chun TW, Tsang JS, Li Y, Fauci AS. Abnormal B cell memory subsets dominate HIV-specific responses in infected individuals. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:3252–3262. doi: 10.1172/JCI74351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasturi SP, Skountzou I, Albrecht RA, Koutsonanos D, Hua T, Nakaya HI, Ravindran R, Stewart S, Alam M, Kwissa M, Villinger F, Murthy N, Steel J, Jacob J, Hogan RJ, Garcia-Sastre A, Compans R, Pulendran B. Programming the magnitude and persistence of antibody responses with innate immunity. Nature. 2011;470:543–547. doi: 10.1038/nature09737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koup RA, Douek DC. Vaccine design for CD8 T lymphocyte responses. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2011;1:a007252. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee FE, Falsey AR, Halliley JL, Sanz I, Walsh EE. Circulating antibody-secreting cells during acute respiratory syncytial virus infection in adults. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2010;202:1659–1666. doi: 10.1086/657158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee FE, Halliley JL, Walsh EE, Moscatiello AP, Kmush BL, Falsey AR, Randall TD, Kaminiski DA, Miller RK, Sanz I. Circulating human antibody-secreting cells during vaccinations and respiratory viral infections are characterized by high specificity and lack of bystander effect. J Immunol. 2011;186:5514–5521. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GM, Chiu C, Wrammert J, McCausland M, Andrews SF, Zheng NY, Lee JH, Huang M, Qu X, Edupuganti S, Mulligan M, Das SR, Yewdell JW, Mehta AK, Wilson PC, Ahmed R. Pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine induces a recall response in humans that favors broadly cross-reactive memory B cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:9047–9052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118979109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao HX, Chen X, Munshaw S, Zhang R, Marshall DJ, Vandergrift N, Whitesides JF, Lu X, Yu JS, Hwang KK, Gao F, Markowitz M, Heath SL, Bar KJ, Goepfert PA, Montefiori DC, Shaw GC, Alam SM, Margolis DM, Denny TN, Boyd SD, Marshal E, Egholm M, Simen BB, Hanczaruk B, Fire AZ, Voss G, Kelsoe G, Tomaras GD, Moody MA, Kepler TB, Haynes BF. Initial antibodies binding to HIV-1 gp41 in acutely infected subjects are polyreactive and highly mutated. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208:2237–2249. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao HX, Lynch R, Zhou T, Gao F, Alam SM, Boyd SD, Fire AZ, Roskin KM, Schramm CA, Zhang Z, Zhu J, Shapiro L, Mullikin JC, Gnanakaran S, Hraber P, Wiehe K, Kelsoe G, Yang G, Xia SM, Montefiori DC, Parks R, Lloyd KE, Scearce RM, Soderberg KA, Cohen M, Kamanga G, Louder MK, Tran LM, Chen Y, Cai F, Chen S, Moquin S, Du X, Joyce MG, Srivatsan S, Zhang B, Zheng A, Shaw GM, Hahn BH, Kepler TB, Korber BT, Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Haynes BF. Co-evolution of a broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody and founder virus. Nature. 2013;496:469–476. doi: 10.1038/nature12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling B, Rogers L, Johnson AM, Piatak M, Lifson J, Veazey RS. Effect of combination antiretroviral therapy on Chinese rhesus macaques of simian immunodeficiency virus infection. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2013;29:1465–1474. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina F, Segundo C, Campos-Caro A, Gonzalez-Garcia I, Brieva JA. The heterogeneity shown by human plasma cells from tonsil, blood, and bone marrow reveals graded stages of increasing maturity, but local profiles of adhesion molecule expression. Blood. 2002;99:2154–2161. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei HE, Yoshida T, Sime W, Hiepe F, Thiele K, Manz RA, Radbruch A, Dorner T. Blood-borne human plasma cells in steady state are derived from mucosal immune responses. Blood. 2009;113:2461–2469. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-153544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura G, Chai N, Park S, Chiang N, Lin Z, Chiu H, Fong R, Yan D, Kim J, Zhang J, Lee WP, Estevez A, Coons M, Xu M, Lupardus P, Balazs M, Swem LR. An in vivo human-plasmablast enrichment technique allows rapid identification of therapeutic influenza A antibodies. Cell host & microbe. 2013;14:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaya HI, Wrammert J, Lee EK, Racioppi L, Marie-Kunze S, Haining WN, Means AR, Kasturi SP, Khan N, Li GM, McCausland M, Kanchan V, Kokko KE, Li S, Elbein R, Mehta AK, Aderem A, Subbarao K, Ahmed R, Pulendran B. Systems biology of vaccination for seasonal influenza in humans. Nature immunology. 2011;12:786–795. doi: 10.1038/ni.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell FP, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS. CD138 (syndecan-1), a plasma cell marker immunohistochemical profile in hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic neoplasms. American journal of clinical pathology. 2004;121:254–263. doi: 10.1309/617D-WB5G-NFWX-HW4L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier N, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Wong KA, Urich E, Fazilleau N, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Plasma cells negatively regulate the follicular helper T cell program. Nature immunology. 2010;11:1110–1118. doi: 10.1038/ni.1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y, Wei C, Eun-Hyung Lee F, Campbell J, Halliley J, Lee JA, Cai J, Kong YM, Sadat E, Thomson E, Dunn P, Seegmiller AC, Karandikar NJ, Tipton CM, Mosmann T, Sanz I, Scheuermann RH. Elucidation of seventeen human peripheral blood B-cell subsets and quantification of the tetanus response using a density-based method for the automated identification of cell populations in multidimensional flow cytometry data. Cytometry. Part B, Clinical cytometry. 2010;78(Suppl 1):S69–S82. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Rashu R, Bhuiyan TR, Chowdhury F, Khan AI, Islam K, LaRocque RC, Ryan ET, Wrammert J, Calderwood SB, Qadri F, Harris JB. Antibody-secreting cell responses after Vibrio cholerae O1 infection and oral cholera vaccination in adults in Bangladesh. Clinical and vaccine immunology : CVI. 2013;20:1592–1598. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00347-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawstron AC, Fenton JA, Ashcroft J, English A, Jones RA, Richards SJ, Pratt G, Owen R, Davies FE, Child JA, Jack AS, Morgan G. The interleukin-6 receptor alpha-chain (CD126) is expressed by neoplastic but not normal plasma cells. Blood. 2000;96:3880–3886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roederer M, Keele BF, Schmidt SD, Mason RD, Welles HC, Fischer W, Labranche C, Foulds KE, Louder MK, Yang ZY, Todd JP, Buzby AP, Mach LV, Shen L, Seaton KE, Ward BM, Bailer RT, Gottardo R, Gu W, Ferrari G, Alam SM, Denny TN, Montefiori DC, Tomaras GD, Korber BT, Nason MC, Seder RA, Koup RA, Letvin NL, Rao SS, Nabel GJ, Mascola JR. Immunological and virological mechanisms of vaccine-mediated protection against SIV and HIV. Nature. 2014;505:502–508. doi: 10.1038/nature12893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson RD, Lalor P, Bernfield M. B lymphocytes express and lose syndecan at specific stages of differentiation. Cell regulation. 1989;1:27–35. doi: 10.1091/mbc.1.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Feldhahn N, Seaman MS, Velinzon K, Pietzsch J, Ott RG, Anthony RM, Zebroski H, Hurley A, Phogat A, Chakrabarti B, Li Y, Connors M, Pereyra F, Walker BD, Wardemann H, Ho D, Wyatt RT, Mascola JR, Ravetch JV, Nussenzweig MC. Broad diversity of neutralizing antibodies isolated from memory B cells in HIV-infected individuals. Nature. 2009a;458:636–640. doi: 10.1038/nature07930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Feldhahn N, Walker BD, Pereyra F, Cutrell E, Seaman MS, Mascola JR, Wyatt RT, Wardemann H, Nussenzweig MC. A method for identification of HIV gp140 binding memory B cells in human blood. Journal of immunological methods. 2009b;343:65–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingai M, Nishimura Y, Klein F, Mouquet H, Donau OK, Plishka R, Buckler-White A, Seaman M, Piatak M, Jr, Lifson JD, Dimitrov DS, Nussenzweig MC, Martin MA. Antibody-mediated immunotherapy of macaques chronically infected with SHIV suppresses viraemia. Nature. 2013;503:277–80. doi: 10.1038/nature12746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K, Garman L, Wrammert J, Zheng NY, Capra JD, Ahmed R, Wilson PC. Rapid generation of fully human monoclonal antibodies specific to a vaccinating antigen. Nature protocols. 2009;4:372–384. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souto-Carneiro MM, Longo NS, Russ DE, Sun HW, Lipsky PE. Characterization of the human Ig heavy chain antigen binding complementarity determining region 3 using a newly developed software algorithm, JOINSOLVER. J Immunol. 2004;172:6790–6802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundling C, Forsell MN, O’Dell S, Feng Y, Chakrabarti B, Rao SS, Lore K, Mascola JR, Wyatt RT, Douagi I, Karlsson Hedestam GB. Soluble HIV-1 Env trimers in adjuvant elicit potent and diverse functional B cell responses in primates. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207:2003–2017. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundling C, Li Y, Huynh N, Poulsen C, Wilson R, O’Dell S, Feng Y, Mascola JR, Wyatt RT, Karlsson Hedestam GB. High-resolution definition of vaccine-elicited B cell responses against the HIV primary receptor binding site. Science translational medicine. 2012a;4 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003752. 142ra96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundling C, Phad G, Douagi I, Navis M, Karlsson Hedestam GB. Isolation of antibody V(D)J sequences from single cell sorted rhesus macaque B cells. Journal of immunological methods. 2012b;386:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundling C, Zhang Z, Phad GE, Sheng Z, Wang Y, Mascola JR, Li Y, Wyatt RT, Shapiro L, Karlsson Hedestam GB. Single-cell and deep sequencing of IgG-switched macaque B cells reveal a diverse Ig repertoire following immunization. J Immunol. 2014;192:3637–3644. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyszko EA, Brun JG, Skarstein K, Peck AB, Jonsson R, Brokstad KA. Phenotypic diversity of peripheral blood plasma cells in primary Sjogren's syndrome. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 2011;73:18–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarte K, Zhan F, De Vos J, Klein B, Shaughnessy J., Jr Gene expression profiling of plasma cells and plasmablasts: toward a better understanding of the late stages of B-cell differentiation. Blood. 2003;102:592–600. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiller T, Meffre E, Yurasov S, Tsuiji M, Nussenzweig MC, Wardemann H. Efficient generation of monoclonal antibodies from single human B cells by single cell RT-PCR and expression vector cloning. Journal of immunological methods. 2008;329:112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LM, Huber M, Doores KJ, Falkowska E, Pejchal R, Julien JP, Wang SK, Ramos A, Chan-Hui PY, Moyle M, Mitcham JL, Hammond PW, Olsen OA, Phung P, Fling S, Wong CH, Phogat S, Wrin T, Simek MD, Koff WC, Wilson IA, Burton DR, Poignard P. Broad neutralization coverage of HIV by multiple highly potent antibodies. Nature. 2011;477:466–470. doi: 10.1038/nature10373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LM, Phogat SK, Chan-Hui PY, Wagner D, Phung P, Goss JL, Wrin T, Simek MD, Fling S, Mitcham JL, Lehrman JK, Priddy FH, Olsen OA, Frey SM, Hammond PW, Kaminsky S, Zamb T, Moyle M, Koff WC, Poignard P, Burton DR. Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an African donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science. 2009;326:285–289. doi: 10.1126/science.1178746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AP, Jr, Scharf L, Scheid JF, Klein F, Bjorkman PJ, Nussenzweig MC. Structural insights on the role of antibodies in HIV-1 vaccine and therapy. Cell. 2014;156:633–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrammert J, Koutsonanos D, Li GM, Edupuganti S, Sui J, Morrissey M, McCausland M, Skountzou I, Hornig M, Lipkin WI, Mehta A, Razavi B, Del Rio C, Zheng NY, Lee JH, Huang M, Ali Z, Kaur K, Andrews S, Amara RR, Wang Y, Das SR, O’Donnell CD, Yewdell JW, Subbarao K, Marasco WA, Mulligan MJ, Compans R, Ahmed R, Wilson PC. Broadly cross-reactive antibodies dominate the human B cell response against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208:181–193. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrammert J, Onlamoon N, Akondy RS, Perng GC, Polsrila K, Chandele A, Kwissa M, Pulendran B, Wilson PC, Wittawatmongkol O, Yoksan S, Angkasekwinai N, Pattanapanyasat K, Chokephaibulkit K, Ahmed R. Rapid and massive virus-specific plasmablast responses during acute dengue virus infection in humans. Journal of virology. 2012;86:2911–2918. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06075-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrammert J, Smith K, Miller J, Langley WA, Kokko K, Larsen C, Zheng NY, Mays I, Garman L, Helms C, James J, Air GM, Capra JD, Ahmed R, Wilson PC. Rapid cloning of high-affinity human monoclonal antibodies against influenza virus. Nature. 2008;453:667–671. doi: 10.1038/nature06890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]