Abstract

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is an autosomal dominant vascular dysplastic disorder, characterized by recurrent nosebleeds (epistaxis), multiple telangiectases and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) in major organs. Mutations in Endoglin (ENG or CD105) and Activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ACVRL1 or ALK1) genes of the TGF-β superfamily receptors are responsible for HHT1 and HHT2 respectively and account for the majority of HHT cases. Haploinsufficiency in ENG and ALK1 is recognized at the underlying cause of HHT. However, the mechanisms responsible for the predisposition to and generation of AVMs, the hallmark of this disease, are poorly understood. Recent data suggest that dysregulated angiogenesis contributes to the pathogenesis of HHT and that the vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF, may be implicated in this disease, by modulating the angiogenic–angiostatic balance in the affected tissues. Hence, anti-angiogenic therapies that target the abnormal vessels and restore the angiogenic–angiostatic balance are candidates for treatment of HHT. Here we review the experimental evidence for dysregulated angiogenesis in HHT, the anti-angiogenic therapeutic strategies used in animal models and some patients with HHT and the potential benefit of the anti-angiogenic treatment for ameliorating this severe, progressive vascular disease.

Keywords: angiogenesis, HHT, endoglin, Alk1, VEGF, anti-angiogenic therapy, anti-VEGF, inflammation

HHT IS A SEVERE SYSTEMIC VASCULAR DYSPLASTIC DISEASE

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is an inherited systemic vascular dysplastic disorder, associated with multiple mucocutaneous telangiectases, recurrent nasal and gastrointestinal bleeding episodes and large arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) in lungs, liver and brain. More than 80% of HHT patients carry a mutation in Endoglin (ENG; HHT1) or Activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ACVRL1; HHT2) genes that code for receptors of the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) superfamily. Reduced expression of ENG and ACVRL1 (haploinsufficiency) leads to a similar HHT phenotype. However, there is a higher incidence of pulmonary and cerebral AVMs in HHT1, while hepatic AVMs and gastrointestinal telangiectases are more often diagnosed in HHT2 patients (Friesel et al., 1987; Govani and Shovlin, 2009; Storch and Hoeger, 2010). This suggests that the HHT phenotype is influenced by the tissue distribution and function of ENG and ACVRL1. Although pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a much rarer event than the occurrence of HHT, it has also been associated with ACVRL1 and ENG mutations (Govani and Shovlin, 2009). In these cases, PAH likely results from a dysfunctional relationship between ACVRL1, ENG and the bone morphogenic protein receptor type II, BMPR2, another member of the TGF-β superfamily of receptors, whose mutations are often the cause of inherited as well as sporadic cases of PAH (Atkinson et al., 2002). Despite extensive work in HHT, no cure for this disease exists. Symptomatic treatments, including AVM embolization, offer some relief, yet HHT is a progressive, severe and potentially life-threatening disease. Recent experimental data and some clinical studies suggest that anti-angiogenic therapies targeting the abnormal vasculature may have some benefits in HHT.

DYSREGULATED ANGIOGENESIS IN HHT

In HHT, the mechanisms leading to predisposition and formation of AVMs, the direct connections between arteries and veins, are yet to be determined. One proposed mechanism is defective arteriovenous differentiation, observed in Eng and Alk1 null embryos that develop AVMs (Oh et al., 2000; Sorensen et al., 2003), but absent in the endothelial-targeted Eng (Eng-iKOe) and Alk1 inducible knockout (Alk1-iKOe) mice (Tual-Chalot et al., 2014). Moreover, focal regression of capillaries leading to formation of AVMs has also been postulated in HHT, however, supporting data for this model are still lacking (Lopez-Novoa and Bernabeu, 2010). Recently, it was shown that wound injury was necessary for development of AVMs in adult Alk1-iKOe (Park et al., 2009) and Eng1-iKOe mice (Garrido-Martin et al., 2014). In addition, intracerebral injection of an adenovirus expressing VEGF contributed to pathogenesis of cerebral AVMs in several transgenic Eng KO mice (Choi et al., 2014). Interestingly, AVMs were found more often at the site of vascular injury or turbulent flow, indicating that these local vascular changes may precipitate the development of AVMs.

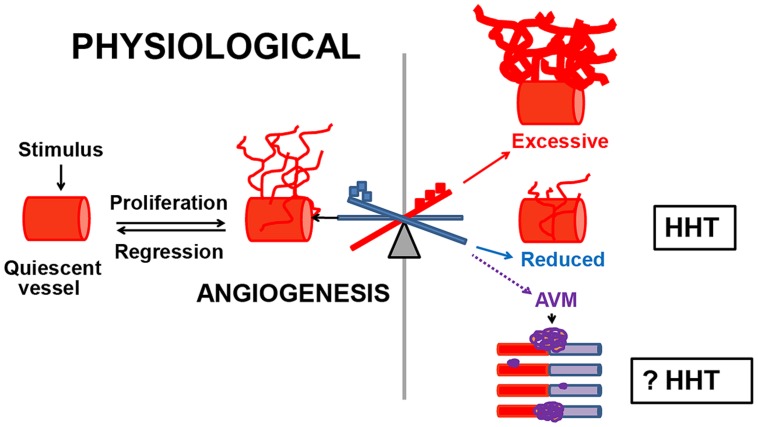

We demonstrated that dysregulated angiogenesis occurs in Eng+/- and Alk1+/- mouse models of HHT. Angiogenesis is the de novo formation of vessels from the pre-existent vascular tree, in response to a stimulus. This biological process is controlled by pro-angiogenic factors that promote vascular growth and angiostatic factors that induce vascular regression. Physiological angiogenesis occurs during development and in healthy individuals, in wound injury and repair, menstruation, pregnancy (Reisinger et al., 2007), and in testis (Collin and Bergh, 1996) and hair follicles (Yano et al., 2003). Under normal conditions, angiogenesis is short-lived, due to finely tuned regulatory mechanisms. In contrast, pathological angiogenesis is abnormal, persists indefinitely and leads to excessive or insufficient generation of new vessels and likely to abnormal ones such as AVMs (Figure 1). Pathological angiogenesis contributes to disease progression in cancer (Nagy et al., 2010), chronic inflammatory and chronic infectious diseases (Carmeliet, 2003). However, the possibility that pathological angiogenesis occurs in HHT has not been explored previously. A few clinical studies showed that vascular endothelial growth factor VEGF, a major angiogenic protein, was elevated in circulation and tissues in HHT patients (Sadick et al., 2005a,b). In addition, it was reported that Alk1+/- mice had higher VEGF mRNA and protein levels in lungs, liver and intestine, when compared to wild type (WT) mice (Shao et al., 2009). These data suggested that VEGF might play a pathogenic role in HHT and that targeting VEGF in animal models of HHT and patients could be beneficial.

FIGURE 1.

Dysregulated angiogenesis in HHT. Normally, when quiescent vessels are activated, they proliferate, migrate and mature until the physiological needs of the organ have been met, and then regress. Pathological angiogenesis commences when the angiogenic–angiostatic balance is disrupted, leading to dysregulated angiogenesis, excessive or reduced tissue MVD and possibly to AVMs. In Eng+/- and Alk1+/- models of HHT, an imbalance in the pulmonary angiostatic TSP-1 and vascular destabilizing factor Ang-2 respectively, led to reduced peripheral lung MVD in both models. However, it is unknown if dysregulated angiogenesis is involved in the development of AVMs in HHT.  Angiogenic factors;

Angiogenic factors;  angiostatic proteins.

angiostatic proteins.

Pathological angiogenesis can be evaluated in experimental models by several approaches, from measuring the levels of angiostatic and angiogenic factors in tissues and circulation to in vitro and in vivo quantification of tissue microvessel density (MVD). To investigate if pathological angiogenesis occurs in HHT, we used the adult Eng+/- and Alk1+/- mice on the C57BL/6 background. Eng+/- and Alk1+/- mice lack AVMs, but develop pulmonary peripheral vascular rarefaction, associated with right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) and spontaneous PAH (Toporsian et al., 2010; Jerkic et al., 2011). Recently, we demonstrated that the lungs are the only organ showing pathological angiogenesis or reduced MVD in both Eng+/- and Alk1+/- mice (Ardelean et al., 2014a). The reduction in peripheral lung MVD was associated with a genotype-specific molecular angiogenic–angiostatic imbalance. Eng+/- lungs had a fourfold increase in the angiostatic factor thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1), which was inversely correlated with the endoglin levels. This finding was confirmed in vitro in endoglin-deficient endothelial cells. In contrast, Alk1+/- lungs showed an augmentation in the vascular destabilizing protein Ang-2, whereas the tissue TSP-1 was normal. However, in both Eng+/- and Alk1+/- lungs, the levels of the major pro-angiogenic and vascular regulator VEGF were unchanged when compared to WT mice, suggesting that factors other than VEGF are implicated in modulation of the tissue angiogenic–angiostatic balance in these mouse models of HHT. These data indicate that an impairment in the molecular balance of angiogenic and angiostatic factors can lead to changes in tissue MVD, in disorders of dysregulated angiogenesis, such as HHT (Figure 1).

Furthermore, a 70% increase in TSP-1 levels was also noted in the liver of Eng+/- mice versus WT littermates, whereas the VEGF levels were normal. This hepatic imbalance in the TSP-1/VEGF levels was not accompanied by an alteration in liver MVD in Eng+/- mice, indicating that a critical molecular threshold must be reached in the levels of angiostatic versus pro-angiogenic factors in order to affect tissue MVD. The liver of Alk1+/- mice had normal MVD and tissue levels of Ang-2 and VEGF.

Surprisingly, even though VEGF does not appear to play a major pathogenic role in Eng+/- and Alk1+/- mice, blocking VEGF with the monoclonal antibody G6-31 led to improvement in the molecular and microvascular phenotype in the affected lungs of these mice (Ardelean et al., 2014a). Anti-VEGF treatment normalized the pulmonary TSP-1 and Ang-2 levels in Eng+/- and Alk1+/- mice respectively, increased and restored the lung peripheral MVD and alleviated the RVH in the treated mice. This suggests that VEGF may be a critical regulator of multiple angiogenic pathways in HHT. Thus, we speculate that the anti-VEGF treatment, by decreasing the pulmonary VEGF levels in both Eng+/- and Alk1+/- mice, reduced the tissue TSP-1 and Ang-2 levels respectively, either (a) directly or (b) possibly via p38 MAPK, a protein involved in signaling transduction for VEGF, some of the TGF-β superfamily of ligands, TSP-1 and Ang-2. However, these currently unknown mechanisms need to be investigated.

In support of the concept that VEGF is a critical angiogenic regulator, G6-31 treatment also led to prevention and reversal of mucocutaneous AVMs in Alk1-iKOe mouse model of HHT (Han et al., 2014), indicating that a reduction in VEGF levels is able to inhibit the growth of AVMs. Thus, anti-VEGF treatment restored the tissue TSP-1 levels and improved the pulmonary microvascular phenotype in Eng+/- and Alk1+/- mice, while it prevented and halted the generation of AVMs in the Alk1 iKOe model of HHT.

ANTI-ANGIOGENIC THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES IN HHT

Judath Folkman, the pioneer of angiogenesis and anti-angiogenic therapy, proposed that angiogenesis can be blocked directly, using drugs that alter EC migration and proliferation or indirectly, via modulation of growth factors that act on the vascular endothelium (Folkman and Klagsbrun, 1987). As HHT is a systemic vascular dysplasia of dysregulated angiogenesis, medication that targets directly or indirectly the abnormal vessels could have beneficial effects in this disease. For example, anti-VEGF treatment and thalidomide that have been tested in HHT exert direct anti-angiogenic properties. Propranolol and timolol are in the process of being tested in HHT and have mostly indirect anti-angiogenic effects. Tacrolimus, interferon (IFN)-α and infliximab, used only in isolated cases of HHT, are predominantly immunomodulatory drugs with some anti-angiogenic capabilities (Table 1). Here, the role of immune system in pathogenesis of HHT is mostly unknown. Whether dysfunctional immune cells contribute directly or indirectly to pathological angiogenesis and whether immunomodulatory therapies could be beneficial in patients diagnosed with HHT, need to be determined.

Table 1.

Mechanisms of several anti-angiogenic and immunomodulatory therapies in HHT.

| Therapy | Angiogenic effects | Evidence | Immuno-modulator | Evidence |

| Tested in patients with HHT | ||||

| Anti-VEGF (G6-31 murine monoclonal antibody) |

+++ | ↑ MVD, ↓ TSP-1, and ↓ Ang-2 in lungs of Eng+/- and Alk1+/- mice, respectively (Ardelean et al., 2014a) ↓ vessel area and density in the skin of Alk1 iKO mouse (Han et al., 2014) |

+ | ↓ inflammation in the colon of DSS-induced Eng+/- colitis (Ardelean et al., 2014b) and the skin of JunB and c-Jun iKO mice (Schonthaler et al., 2009) |

| Thalidomide | ++ |

High dose (200 mg/kg) ↓ vascular area in rabbit cornea (D’Amato et al., 1994) ↓ VEGF, migration and tube formation in EA.hy 926 EC (Komorowski et al., 2006) ↓ VEGFR2 and neuropilin-1 in zebrafish embryos (Yabu et al., 2005) Low dose (75 mg/kg) ↑ pericyte recruitment in neonatal mouse retina (Lebrin et al., 2010) |

++ | ↓ human monocyte-dependent secretion of several cytokines ↑ proliferation and function of circulating human T lymphocytes ↓ number of adhesion molecules in HUVEC ↑ number of NK cells in human multiple myeloma cell lines (Teo, 2005) |

| To be tested in HHT patients | ||||

| Propranolol | ++ | ↓ proliferation and ↑ apoptosis in HUVEC (Xie et al., 2013) ↓ VEGF and MMP-9 in hemangioma-derived EC (Storch and Hoeger, 2010) ↓ endoglin, ACVRL1, PAI-1 in HMEC-1 and HUVEC (Albinana et al., 2012) |

+ | ↑ number of T cells, ↓ NK cell activity in human blood (Maisel et al., 1991) |

| Not yet proposed for HHT patients | ||||

| Tacrolimus | + | ↓ VEGF-induced mouse EC tube formation (Siamakpour-Reihani et al., 2011) ↑ endoglin and Alk1 in HUVEC (Albinana et al., 2011) |

+++ | ↓ T-cell activation in mouse spleen and T cell hybridoma, and in PBMC (Kino et al., 1987; Bierer et al., 1991) |

| IFN-α | + | ↓ EC migration and proliferation in HUVEC (Friesel et al., 1987) |

+++ | Anti-viral in human blood (Neumann et al., 1998), immunomodulation in human blood (Blanco et al., 2001) |

| Infliximab | + | ↓ MVD, VEGF, and EC migration in human intestinal tissue and EC (Rutella et al., 2011) | +++ | Binds soluble and membrane TNF-α in mouse myeloma cells (Scallon et al., 2002) |

DSS, dextran sodium sulfate; HMEC-1, human microvascular endothelial cells; iKO, conditional inducible knockout; MMP-9, matrix metallopeptidase; NK, natural killer cells; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; VEGFR2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2.

ANTI-VEGF TREATMENT

Recently we have shown that G6-31, a monoclonal antibody that blocks VEGF, had unexpected pro-angiogenic effects, reversing the rarefied peripheral lung microvasculature and restoring the tissue TSP-1 and Ang-2 levels in Eng+/- and Alk1+/- mouse models of HHT, respectively (Ardelean et al., 2014a; Table 1).

Several clinical reports noted that HHT patients treated systemically with 5-10 mg/kg of bevacizumab, a humanized anti-VEGF antibody, showed a significant improvement in the frequency of epistaxis, number of required blood transfusions and that some patients no longer needed a liver transplantation (Mitchell et al., 2008; Bose et al., 2009; Oosting et al., 2009; Retornaz et al., 2009). These data were confirmed in a phase 2 clinical trial that included HHT patients with severe liver involvement (Dupuis-Girod et al., 2012). Interestingly, five of the eight patients treated in this trial with the anti-VEGF therapy also showed alleviation of secondary PAH. However, the effects of anti-VEGF therapy on lung and brain AVMs have not been studied to date in HHT patients.

Other studies demonstrated that intranasal topical or submucosal injections of bevacizumab, at 25–100 mg/dose, decreased the frequency of epistaxis in several HHT patients (Simonds et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2011). Yet, the mechanisms through which bevacizumab exerted these effects are poorly understood.

Despite these promising results, anti-VEGF treatment, especially at high dose and/or administered for long-term, can have side effects including hypertension, severe proteinuria, gastrointestinal bleeding, and wound dehiscence (Pavlidis and Pavlidis, 2013). These effects are reversible and possibly avoided with close monitoring, lower doses and shorter regimens of anti-VEGF therapy. For example, systemic bevacizumab at 1 mg/kg showed promising results by reducing nasal and gastrointestinal bleeding in a patient with HHT (Suppressa et al., 2011). Moreover, preliminary results of a phase-1 double-blind single center study, evaluating the safety of a bevacizumab nasal spray in HHT-associated epistaxis, suggested no outcome differences between low (12.5 mg), intermediate (50 and 75 mg), or high (100 mg) doses (Dupuis-Girod et al., 2014). Therefore, lower intranasal anti-VEGF doses may be the preferred therapeutic approach in reducing the nosebleeds in HHT. Overall, off-label use of anti-VEGF therapy showed promising results in HHT. However, caution is warranted, as the mechanisms of AVM formation in HHT are yet to be determined and the effects of this therapy, particularly on lung and brain AVMs, are still unknown.

THALIDOMIDE

Thalidomide and the second-generation analog lenalidomide, are medications with anti-angiogenic and immunomodulatory effects (Table 1), used clinically in multiple myeloma and erythema nodosum of leprosy (Teo, 2005). The anti-angiogenic effects of thalidomide are dose-dependent (Table 1).

In HHT patients, thalidomide given orally at 50–200 mg/day decreased the number of telangiectases, epistaxis and transfusions (Chen et al., 2012; Franchini et al., 2013). However, thalidomide doses ≥100 mg per day can cause peripheral neuropathy, somnolence, constipation and deep vein thrombosis. The side effects of thalidomide can be attenuated by reducing the dose given (Teo, 2005).

In several HHT patients, oral lenalidomide at 10–15 mg/day, reduced the number of gastrointestinal bleeds (Bowcock and Patrick, 2009). Lenalidomide inhibited VEGF production and migration of EC, hence showed anti-angiogenic properties, and had improved immunomodulatory effects and safety profile, when compared to thalidomide. The most common side effects of lenalidomide were anemia, constipation and drowsiness (Teo, 2005).

PROPRANOLOL AND TIMOLOL

Propranolol and timolol are non-selective beta-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) blockers with anti-angiogenic properties (Table 1). Both medications are vasoconstrictive by inhibiting the effects of adrenaline on the endothelial β-AR. Propranolol showed anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects on human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC; Xie et al., 2013), hence, has anti-angiogenic properties (Table 1). In addition, propranolol reduced VEGF and MMP-9 tissue expression (Storch and Hoeger, 2010), thus indirectly inhibiting angiogenesis. Interestingly, propranolol diminished in vitro endoglin and ACVRL1 mRNA and protein levels. It also decreased PAI-1 levels, a downstream protein of the TGF-β1-ALK5-endoglin-mediated signaling pathway, effect that can increase bleeding in HHT (Albinana et al., 2012). Clinical data to confirm these potentially undesirable effects in HHT are lacking. One case report indicated that intranasal timolol (0.5% ophthalmic solution) reduced the frequency and severity of epistaxis in one HHT patient, after 3–4 days of treatment (Olitsky, 2012). The results of a clinical trial testing the effect of topical timolol on cutaneous telangiectases in HHT are pending (http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01752049).

TACROLIMUS (FK506, PROGRAF)

Tacrolimus is an immunomodulator macrolide with anti-angiogenic properties (Table 1), used in organ transplantation (Posadas Salas and Srinivas, 2014), some patients with rheumatoid arthritis, lupus nephritis (Tanaka et al., 2012), ulcerative colitis (Inoue et al., 2013) and topically, in severe eczema and vitiligo.

One case report noted that a woman diagnosed with HHT, hepatic AVMs and high-output cardiac failure, treated in the first year post liver transplantation with sirolimus (rapamycin), an inhibitor of mTOR, low dose tacrolimus (trough levels 2–5 ng/ml/day), prednisone (5 mg/day in the first 6 months) and aspirin (81 mg/day), experienced cessation of mucosal bleeding, normalization of hemoglobin levels and disappearance of cutaneous and gastrointestinal telangiectases. This suggests that the combined immunosuppressive therapy might have exerted anti-angiogenic effects on telangiectases (Skaro et al., 2006). Patients treated with tacrolimus need to be monitored for potential adverse effects, such as severe infections, hypertension, renal and central nervous system dysfunction.

INTERFERON-α

Interferon-α is a cytokine with anti-viral and immunoregulatory properties, used to treat some patients with chronic hepatitis and certain hematological cancers (Platanias, 2005). IFN-α binds to type I IFN receptors, inducing their phosphorylation, stimulation of the transcription factors Stat1 and Stat2, and activation of multiple target genes. However, it is less known that IFN-α also has some anti-angiogenic properties (Friesel et al., 1987; Table 1).

In two patients with HHT and co-morbidities, metastatic renal cancer and chronic hepatitis C respectively, INF-α (3 million units injected subcutaneously three times a week for 3 and 30 months respectively) had beneficial effects on epistaxis and telangiectases (Massoud et al., 2004; Wheatley-Price et al., 2005). Potential side effects of IFN-α include decrease in blood cell count, and liver and thyroid dysfunction.

INFLIXIMAB (REMICADE)

Infliximab is a chimeric anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α monoclonal antibody that binds soluble and membrane-bound TNF-α. Thus, it is used to treat rheumatic and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD; Willrich et al., 2014). Recent in vivo and in vitro data from patients diagnosed with IBD and treated with infliximab indicated that this anti-TNF-α antibody had some anti-angiogenic properties (Rutella et al., 2011; Table 1).

Interestingly, infliximab (5 mg/kg intravenously administered every 8 weeks for a total of 40 infusions) given to a 21 year-old man with refractory Crohn’s disease and HHT, on chronic iron infusions, reduced the frequency of nosebleeds and stabilized the hemoglobin levels after the third dose (Papa et al., 2010). As HHT is a non-inflammatory vasculopathy, this observation supports the concept that infliximab might have intrinsic anti-angiogenic properties that could be beneficial in HHT. Given that infliximab is an immunomodulatory medication, several adverse effects can occur: severe infections, demyelinating diseases and potentially lymphomas (Willrich et al., 2014).

CONCLUSION

Dysregulated angiogenesis, induced by a tissue imbalance in angiogenic and angiostatic factors, plays a role in the pathogenesis of HHT. However, the mechanisms that predispose to and are responsible for AVM formation in HHT are yet to be discovered. Surprisingly, VEGF blockage led to increased MVD and restoration of the TSP-1 and Ang-2 balance in the lungs of Eng+/- and Alk1+/- mice respectively, and prevented or decreased AVM formation in the Alk1 iKOe mice. Hence, even though VEGF is not a major pathogenic factor, it acts as a critical modulator of angiogenesis in HHT.

Drugs that target directly or indirectly the angiogenic vessels and the master angiogenic regulator VEGF, showed promising results in HHT. However, caution is warranted, as systemic anti-angiogenic treatment can also alter the vasculature in the unaffected organs. The potential side effects of systemic anti-angiogenic therapy are generally reversible with discontinuation of treatment. Moreover, the effects of anti-VEGF therapy on human AVMs are currently unknown. Several immunomodulatory agents display some anti-angiogenic properties. In addition, immune modulation, possibly through regulation of common immune and angiogenic pathways, may be an option for patients with HHT and co-morbidities of immune dysregulation. Overall, anti-angiogenic therapies showed some encouraging results in HHT. However, more mechanistic studies and larger clinical trials are required to fully understand the implications of using anti-angiogenic therapies in HHT.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada to ML (T5598). DSA was the recipient of a CIHR/CAG/Abbott fellowship award.

REFERENCES

- Albinana V., Recio-Poveda L., Zarrabeitia R., Bernabeu C., Botella L. M. (2012). Propranolol as antiangiogenic candidate for the therapy of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Thromb. Haemost. 108 41–53 10.1160/TH11-11-0809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albinana V., Sanz-Rodriguez F., Recio-Poveda L., Bernabeu C., Botella L. M. (2011). Immunosuppressor FK506 increases endoglin and activin receptor-like kinase 1 expression and modulates transforming growth factor-beta1 signaling in endothelial cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 79 833–843 10.1124/mol.110.067447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardelean D. S., Jerkic M., Yin M., Peter M., Ngan B., Kerbel R. S., et al. (2014a). Endoglin and activin receptor-like kinase 1 heterozygous mice have a distinct pulmonary and hepatic angiogenic profile and response to anti-VEGF treatment. Angiogenesis 17 129–146 10.1007/s10456-013-9383-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardelean D. S., Yin M., Jerkic M., Peter M., Ngan B., Kerbel R. S., et al. (2014b). Anti-VEGF therapy reduces intestinal inflammation in Endoglin heterozygous mice subjected to experimental colitis. Angiogenesis 17 641–659 10.1007/s10456-014-9421-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson C., Stewart S., Upton P. D., Machado R., Thomson J. R., Trembath R. C., et al. (2002). Primary pulmonary hypertension is associated with reduced pulmonary vascular expression of type II bone morphogenetic protein receptor. Circulation 105 1672–1678 10.1161/01.CIR.0000012754.72951.3D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierer B. E., Schreiber S. L., Burakoff S. J. (1991). The effect of the immunosuppressant FK-506 on alternate pathways of T cell activation. Eur. J. Immunol. 21 439–445 10.1002/eji.1830210228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco P., Palucka A. K., Gill M., Pascual V., Banchereau J. (2001). Induction of dendritic cell differentiation by IFN-alpha in systemic lupus erythematosus. Science 294 1540–1543 10.1126/science.1064890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose P., Holter J. L., Selby G. B. (2009). Bevacizumab in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. N. Engl. J. Med. 360 2143–2144 10.1056/NEJMc0901421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowcock S. J., Patrick H. E. (2009). Lenalidomide to control gastrointestinal bleeding in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: potential implications for angiodysplasias? Br. J. Haematol. 146 220–222 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07730.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P. (2003). Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nat. Med. 9 653–660 10.1038/nm0603-653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. H., Hsu H. H., Hu R. H., Lee P. H., Ho C. M. (2012). Long-term therapy with thalidomide in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: case report and literature review. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 52 1436–1440 10.1177/0091270011417824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. T., Karnezis T., Davidson T. M. (2011). Safety of intranasal bevacizumab (Avastin) treatment in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia-associated epistaxis. Laryngoscope 121 644–646 10.1002/lary.21345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi E. J., Chen W., Jun K., Arthur H. M., Young W. L., Su H. (2014). Novel brain arteriovenous malformation mouse models for type 1 hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. PLoS ONE 9:e88511 10.1371/journal.pone.0088511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin O., Bergh A. (1996). Leydig cells secrete factors which increase vascular permeability and endothelial cell proliferation. Int. J. Androl. 19 221–228 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1996.tb00466.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato R. J., Loughnan M. S., Flynn E., Folkman J. (1994). Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91 4082–4085 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis-Girod S., Ambrun A., Decullier E., Samson G., Roux A., Fargeton A. E., et al. (2014). ELLIPSE Study: a phase 1 study evaluating the tolerance of bevacizumab nasal spray in the treatment of epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. MAbs 6 794–799 10.4161/mabs.28025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis-Girod S., Ginon I., Saurin J. C., Marion D., Guillot E., Decullier E., et al. (2012). Bevacizumab in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia and severe hepatic vascular malformations and high cardiac output. JAMA 307 948–955 10.1001/jama.2012.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J., Klagsbrun M. (1987). Angiogenic factors. Science 235 442–447 10.1126/science.2432664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchini M., Frattini F., Crestani S., Bonfanti C. (2013). Novel treatments for epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: a systematic review of the clinical experience with thalidomide. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 36 355–357 10.1007/s11239-012-0840-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesel R., Komoriya A., Maciag T. (1987). Inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation by gamma-interferon. J. Cell Biol. 104 689–696 10.1083/jcb.104.3.689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido-Martin E. M., Nguyen H. L., Cunningham T. A., Choe S. W., Jiang Z., Arthur H. M., et al. (2014). Common and distinctive pathogenetic features of arteriovenous malformations in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia 1 and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia 2 animal models–brief report. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 34 2232–2236 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govani F. S., Shovlin C. L. (2009). Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: a clinical and scientific review. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 17 860–871 10.1038/ejhg.2009.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C., Choe S. W., Kim Y. H., Acharya A. P., Keselowsky B. G., Sorg B. S., et al. (2014). VEGF neutralization can prevent and normalize arteriovenous malformations in an animal model for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia 2. Angiogenesis 17 823–830 10.1007/s10456-014-9436-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T., Murano M., Narabayashi K., Okada T., Nouda S., Ishida K., et al. (2013). The efficacy of oral tacrolimus in patients with moderate/severe ulcerative colitis not receiving concomitant corticosteroid therapy. Intern. Med. 52 15–20 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.8555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerkic M., Kabir M. G., Davies A., Yu L. X., Mcintyre B. A., Husain N. W., et al. (2011). Pulmonary hypertension in adult Alk1 heterozygous mice due to oxidative stress. Cardiovasc. Res. 92 375–384 10.1093/cvr/cvr232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kino T., Hatanaka H., Miyata S., Inamura N., Nishiyama M., Yajima T., et al. (1987). FK-506, a novel immunosuppressant isolated from a Streptomyces. II. Immunosuppressive effect of FK-506 in vitro. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 40 1256–1265 10.7164/antibiotics.40.1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komorowski J., Jerczynska H., Siejka A., Baranska P., Lawnicka H., Pawlowska Z., et al. (2006). Effect of thalidomide affecting VEGF secretion, cell migration, adhesion and capillary tube formation of human endothelial EA.hy 926 cells. Life Sci. 78 2558–2563 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrin F., Srun S., Raymond K., Martin S., Van Den Brink S., Freitas C., et al. (2010). Thalidomide stimulates vessel maturation and reduces epistaxis in individuals with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Nat. Med. 16 420–428 10.1038/nm.2131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Novoa J. M., Bernabeu C. (2010). The physiological role of endoglin in the cardiovascular system. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 299 H959–H974 10.1152/ajpheart.01251.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisel A. S., Murray D., Lotz M., Rearden A., Irwin M., Michel M. C. (1991). Propranolol treatment affects parameters of human immunity. Immunopharmacology 22 157–164 10.1016/0162-3109(91)90040-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoud O. I., Youssef W. I., Mullen K. D. (2004). Resolution of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia and anemia with prolonged alpha-interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 38 377–379 10.1097/00004836-200404000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell A., Adams L. A., Macquillan G., Tibballs J., Vanden Driesen R., Delriviere L. (2008). Bevacizumab reverses need for liver transplantation in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Liver Transpl. 14 210–213 10.1002/lt.21417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy J. A., Chang S. H., Shih S. C., Dvorak A. M., Dvorak H. F. (2010). Heterogeneity of the tumor vasculature. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 36 321–331 10.1055/s-0030-1253454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann A. U., Lam N. P., Dahari H., Gretch D. R., Wiley T. E., Layden T. J., et al. (1998). Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science 282 103–107 10.1126/science.282.5386.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S. P., Seki T., Goss K. A., Imamura T., Yi Y., Donahoe P. K., et al. (2000). Activin receptor-like kinase 1 modulates transforming growth factor-beta 1 signaling in the regulation of angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 2626–2631 10.1073/pnas.97.6.2626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olitsky S. E. (2012). Topical timolol for the treatment of epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Am.J.Otolaryngol. 33 375–376 10.1016/j.amjoto.2011.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosting S., Nagengast W., De Vries E. (2009). More on bevacizumab in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. N. Engl. J. Med. 361 931–932 10.1056/NEJMc091271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa A., Felice C., Marzo M., Guidi L. (2010). A case of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia associated with Crohn’s disease successfully treated with infliximab. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 105:1904 10.1038/ajg.2010.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. O., Wankhede M., Lee Y. J., Choi E. J., Fliess N., Choe S. W., et al. (2009). Real-time imaging of de novo arteriovenous malformation in a mouse model of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J. Clin. Invest. 119 3487–3496 10.1172/JCI39482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis E. T., Pavlidis T. E. (2013). Role of bevacizumab in colorectal cancer growth and its adverse effects: a review. World J. Gastroenterol. 19 5051–5060 10.3748/wjg.v19.i31.5051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platanias L. C. (2005). Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5 375–386 10.1038/nri1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posadas Salas M. A., Srinivas T. R. (2014). Update on the clinical utility of once-daily tacrolimus in the management of transplantation. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 8 1183–1194 10.2147/DDDT.S55458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger K., Baal N., Mckinnon T., Munstedt K., Zygmunt M. (2007). The gonadotropins: tissue-specific angiogenic factors? Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 269 65–80 10.1016/j.mce.2006.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retornaz F., Rinaldi Y., Duvoux C. (2009). More on bevacizumab in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. N. Engl. J. Med. 361 931; author reply 931–932 10.1056/NEJMc091271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutella S., Fiorino G., Vetrano S., Correale C., Spinelli A., Pagano N., et al. (2011). Infliximab therapy inhibits inflammation-induced angiogenesis in the mucosa of patients with Crohn’s disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 106 762–770 10.1038/ajg.2011.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadick H., Naim R., Gossler U., Hormann K., Riedel F. (2005a). Angiogenesis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: VEGF165 plasma concentration in correlation to the VEGF expression and microvessel density. Int. J. Mol. Med. 15 15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadick H., Riedel F., Naim R., Goessler U., Hormann K., Hafner M., et al. (2005b). Patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia have increased plasma levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta1 as well as high ALK1 tissue expression. Haematologica 90 818–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scallon B., Cai A., Solowski N., Rosenberg A., Song X. Y., Shealy D., et al. (2002). Binding and functional comparisons of two types of tumor necrosis factor antagonists. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 301 418–426 10.1124/jpet.301.2.418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonthaler H. B., Huggenberger R., Wculek S. K., Detmar M., Wagner E. F. (2009). Systemic anti-VEGF treatment strongly reduces skin inflammation in a mouse model of psoriasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 21264–21269 10.1073/pnas.0907550106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao E. S., Lin L., Yao Y., Bostrom K. I. (2009). Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor is coordinately regulated by the activin-like kinase receptors 1 and 5 in endothelial cells. Blood 114 2197–2206 10.1182/blood-2009-01-199166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siamakpour-Reihani S., Caster J., Bandhu Nepal D., Courtwright A., Hilliard E., Usary J., et al. (2011). The role of calcineurin/NFAT in SFRP2 induced angiogenesis–a rationale for breast cancer treatment with the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus. PLoS ONE 6:e20412 10.1371/journal.pone.0020412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonds J., Miller F., Mandel J., Davidson T. M. (2009). The effect of bevacizumab (Avastin) treatment on epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Laryngoscope 119 988–992 10.1002/lary.20159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaro A. I., Marotta P. J., Mcalister V. C. (2006). Regression of cutaneous and gastrointestinal telangiectasia with sirolimus and aspirin in a patient with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Ann. Intern. Med. 144 226–227 10.7326/0003-4819-144-3-200602070-00030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen L. K., Brooke B. S., Li D. Y., Urness L. D. (2003). Loss of distinct arterial and venous boundaries in mice lacking endoglin, a vascular-specific TGFbeta coreceptor. Dev. Biol. 261 235–250 10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00158-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch C. H., Hoeger P. H. (2010). Propranolol for infantile haemangiomas: insights into the molecular mechanisms of action. Br. J. Dermatol. 163 269–274 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppressa P., Liso A., Sabba C. (2011). Low dose intravenous bevacizumab for the treatment of anaemia in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Br. J. Haematol. 152 365 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08481.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H., Tsuruga K., Aizawa-Yashiro T., Watanabe S., Imaizumi T. (2012). Treatment of young patients with lupus nephritis using calcineurin inhibitors. World J. Nephrol. 1 177–183 10.5527/wjn.v1.i6.177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo S. K. (2005). Properties of thalidomide and its analogues: implications for anticancer therapy. AAPS J. 7 E14–E19 10.1208/aapsj070103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toporsian M., Jerkic M., Zhou Y. Q., Kabir M. G., Yu L. X., Mcintyre B. A., et al. (2010). Spontaneous adult-onset pulmonary arterial hypertension attributable to increased endothelial oxidative stress in a murine model of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30 509–517 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.200121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tual-Chalot S., Mahmoud M., Allinson K. R., Redgrave R. E., Zhai Z., Oh S. P., et al. (2014). Endothelial depletion of Acvrl1 in mice leads to arteriovenous malformations associated with reduced endoglin expression. PLoS ONE 9:e98646 10.1371/journal.pone.0098646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley-Price P., Shovlin C., Chao D. (2005). Interferon for metastatic renal cell cancer causing regression of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 39 344–345 10.1097/01.mcg.0000155137.73433.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willrich M. A., Murray D. L., Snyder M. R. (2014). Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: clinical utility in autoimmune diseases. Transl. Res. 165 270–282 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W., Xie H., Liu F., Li W., Dan J., Mei Y., et al. (2013). Propranolol induces apoptosis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells through downregulation of CD147. Br. J. Dermatol. 168 739–748 10.1111/bjd.12193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabu T., Tomimoto H., Taguchi Y., Yamaoka S., Igarashi Y., Okazaki T. (2005). Thalidomide-induced antiangiogenic action is mediated by ceramide through depletion of VEGF receptors, and is antagonized by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Blood 106 125–134 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano K., Brown L. F., Lawler J., Miyakawa T., Detmar M. (2003). Thrombospondin-1 plays a critical role in the induction of hair follicle involution and vascular regression during the catagen phase. J. Invest. Dermatol. 120 14–19 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]