Abstract

Background

Muscle weakness in old age is associated with physical function decline. Progressive resistance strength training (PRT) exercises are designed to increase strength.

Objectives

To assess the effects of PRT on older people and identify adverse events.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group Specialized Register (to March 2007), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2007, Issue 2), MEDLINE (1966 to May 01, 2008), EMBASE (1980 to February 06 2007), CINAHL (1982 to July 01 2007) and two other electronic databases. We also searched reference lists of articles, reviewed conference abstracts and contacted authors.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials reporting physical outcomes of PRT for older people were included.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials, assessed trial quality and extracted data. Data were pooled where appropriate.

Main results

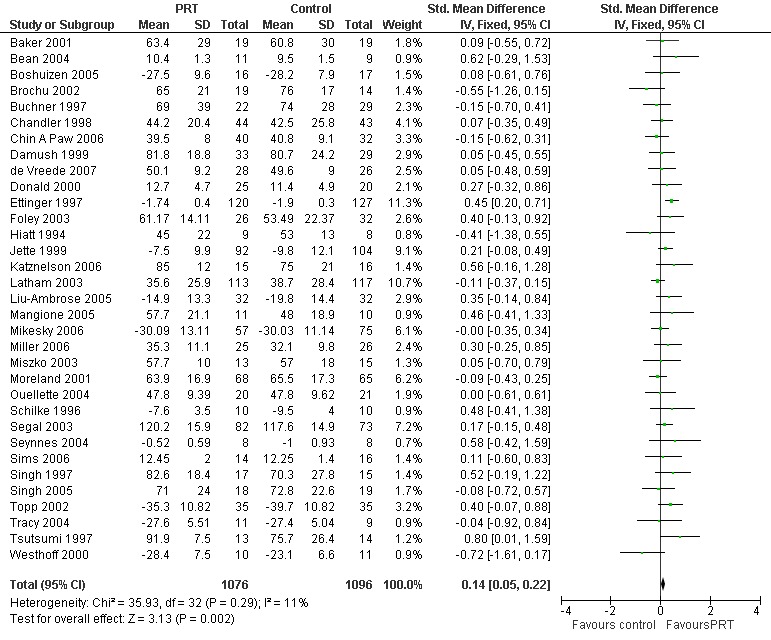

One hundred and twenty one trials with 6700 participants were included. In most trials, PRT was performed two to three times per week and at a high intensity. PRT resulted in a small but significant improvement in physical ability (33 trials, 2172 participants; SMD 0.14, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.22). Functional limitation measures also showed improvements: e.g. there was a modest improvement in gait speed (24 trials, 1179 participants, MD 0.08 m/s, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.12); and a moderate to large effect for getting out of a chair (11 trials, 384 participants, SMD ‐0.94, 95% CI ‐1.49 to ‐0.38). PRT had a large positive effect on muscle strength (73 trials, 3059 participants, SMD 0.84, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.00). Participants with osteoarthritis reported a reduction in pain following PRT(6 trials, 503 participants, SMD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐0.48 to ‐0.13). There was no evidence from 10 other trials (587 participants) that PRT had an effect on bodily pain. Adverse events were poorly recorded but adverse events related to musculoskeletal complaints, such as joint pain and muscle soreness, were reported in many of the studies that prospectively defined and monitored these events. Serious adverse events were rare, and no serious events were reported to be directly related to the exercise programme.

Authors' conclusions

This review provides evidence that PRT is an effective intervention for improving physical functioning in older people, including improving strength and the performance of some simple and complex activities. However, some caution is needed with transferring these exercises for use with clinical populations because adverse events are not adequately reported.

Plain language summary

Progressive resistance strength training for improving physical function in older adults

Older people generally lose muscle strength as they age. This reduction in muscle strength and associated weakness means that older people are more likely to have problems carrying out their daily activities and to fall. Progressive resistance training (PRT) is a type of exercise where participants exercise their muscles against some type of resistance that is progressively increased as their strength improves. The exercise is usually conducted two to three times a week at moderate to high intensity by using exercise machines, free weights, or elastic bands.This review sets out to examine if PRT can help to improve physical function and muscle strength in older people.

Evidence from 121 randomised controlled trials (6,700 participants) shows that older people who exercise their muscles against a force or resistance become stronger. They also improve their performance of simple activities such as walking, climbing steps, or standing up from a chair more quickly. The improvement in activities such as getting out of a chair or stair climbing is generally greater than walking speed. Moreover, these strength training exercises also improved older people's physical abilities, including more complex daily activities such as bathing or preparing a meal. PRT also reduced pain in people with osteoarthritis. There was insufficient evidence to comment on the risks of PRT or long term effects.

Background

Description of the condition

Muscle strength is the amount of force produced by a muscle. The loss of muscle strength in old age is a prevalent condition. Muscle strength declines with age such that, on average, the strength of people in their 80s is about 40% less than that of people in their 20s (Doherty 1993). Muscle weakness, particularly of the lower limbs, is associated with reduced walking speed (Buchner 1996), increased risk of disability (Guralnik 1995) and falls in older people (Tinetti 1986).

Description of the intervention

Progressive resistance training (PRT) is often used to increase muscle strength. During the exercise, participants exercise their muscles against some type of resistance that is progressively increased as strength improves. Common equipment used for PRT includes exercise machines, free weights, and elastic bands.

How the intervention might work

Contrary to long held beliefs, the muscles of older people (i.e. people aged 60 years and older) continue to be adaptable, even into the extremes of old age (Frontera 1988). Trials have revealed that older people can experience large improvements in their muscle strength, particularly if their muscles are significantly overloaded during training (Brown 1990; Charette 1991; Fiatarone 1994).

Why it is important to do this review

Despite evidence of benefit from PRT in terms of improving muscle strength, there is still uncertainty about how these effects translate into changes in substantive outcomes such a reduction in physical disability (Chandler 1998). Most studies have been under‐powered to determine the effects of PRT on these outcomes or have included PRT as part of a complex intervention. In addition, there is uncertainty about the effects of PRT when more pragmatic, home or hospital‐based programmes are used, and the safety and effectiveness of this intervention in older adults who have health problems and/or functional limitations. Finally, there is uncertainty about the relative benefits of PRT compared with other exercise programmes, or the effectiveness of varying doses of PRT (i.e. programmes of varying intensity and duration). This update of our review (Latham 2003a) has continued to assess and summarise the evidence for PRT.

Objectives

To determine the effects of progressive resistance strength training (PRT) on physical function in older adults through comparing PRT with no exercise, or another type of care or exercise (e.g. aerobic training). Comparisons of different types (e.g. intensities, frequencies, or speed) of PRT were included also. We considered these effects primarily in terms of measures of physical (dis)ability and adverse effects, and secondary measures of functional impairment (muscle strength & aerobic capacity) and limitation (e.g. gait speed).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Any randomised clinical trials meeting the specifications below were included. All non‐randomised controlled trials (e.g. controlled before and after studies) were excluded. Also excluded were trials for which details were provided that indicated these used quasi‐randomised methods, such as allocation based on date of birth.

Types of participants

Older people, resident in institutions or at home in the community. Trials were included if the mean age of participants was 60 or over, but excluded if participants aged less than 50 were enrolled. The participants could include frail or disabled older people, people with identified diseases or health problems, or fit and healthy people.

Types of interventions

Any trial that had one group of participants who received PRT as a primary intervention was considered for inclusion. PRT was defined as a strength training programme in which the participants exercised their muscles against an external force that was set at specific intensity for each participant, and this resistance was adjusted throughout the training programme. The type of resistance used included elastic bands or tubing (i.e. therabands), cuff weights, free weights, isokinetic machines or other weight machines. This type of training could take place in individual or group exercise programmes, and in a home‐based or gymnasium/clinic setting. Studies that utilised only isometric exercises were excluded. Studies that included balance, aerobic or other training as part of the exercise intervention (and not simply part of the warm‐up or cool‐down) were also excluded.

We found the following comparisons between groups in the trials:

PRT versus no exercise (greatest difference between groups was expected)

Different types of PRT: high intensity versus low intensity, high frequency versus low frequency, or higher speed (power training) versus regular speed (greatest effect expected in the higher intensity groups). Power training refers to the type of PRT that emphasizes speed.

PRT versus regular care (including regular therapy or exercise)

PRT versus another type of exercise (smaller difference between groups expected)

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

This review assessed physical function in older adults at the level of impairment, functional limitation and disability. The primary outcome of this review was physical disability. This was assessed as a continuous variable. The outcomes were categorized based on the Nagi model of health states (Nagi 1991). In this model, disability is considered to be a limitation in performance of socially defined roles and tasks that can relate to self‐care, work, family etc. In this review, the primary assessment of physical disability included the evaluation of self‐reported measures of activities of daily living (ADL, i.e. the Barthel Index) and the physical domains of health‐related quality of life (HRQOL, i.e. the physical function domain of the SF‐36). Data from these measures were pooled for the main analysis of physical disability. However, because these two types of measures (ADL and physical domains of HRQOL) evaluate different health concepts, they were also evaluated in separate analyses. The Nagi model also includes firstly, the domain of 'functional limitations' which are limitations in performance at the level of the whole person and includes activities such as walking, climbing or reaching, and secondly, 'impairments' that are defined as anatomical or physiological abnormalities.

Since the protocol of this review was written, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Handicap (ICF) has been released (WHO 2001). Under this system, disability is an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions. Using the ICF, the outcome measures evaluated in this review fall under the domains of impairments, limitations in simple activities (similar to 'functional limitations' in Nagi's system) and limitations in complex activities (similar to some aspects of disability in Nagi's model).

Secondary outcomes

Measures of impairment (outcome comparisons 2 and 3)

The following secondary outcomes were assessed as continuous variables:

muscle strength (e.g. 1 repetition maximum test, isokinetic and isometric dynamometry)

aerobic capacity (e.g. 6 minute walk test, VO2 max: maximal oxygen uptake during exercise)

Measures of functional limitation (simple physical activities)

The following secondary outcomes were assessed as continuous variables:

balance (e.g. Berg Balance Scale, Functional Reach Test)

gait speed, timed walk

timed 'up‐and‐go' test

chair rise (sit to stand)

stair climbing (added in 2008)

The balance outcome is also reviewed in a separate Cochrane review (Howe 2007).

Other outcomes

The dichotomous secondary outcomes assessed were adverse events, admission to hospital and death. The effect of PRT on falls was also evaluated, although these outcomes are considered in a separate Cochrane review (Gillespie 2003). Pain and vitality measures were evaluated as continuous outcomes, and were used to provide additional information about the potential adverse effects or benefits of PRT.

Outcomes removed after the protocol

In the original protocol for this review, measures of fear of falling and participation in social activities were also included as outcomes. However, when the size and complexity of this review became apparent, the authors decided to limit this review to assessments of physical disability as this was the prespecified primary aim of the review. Therefore, these outcomes are not included in the current review. In addition, the protocol also stated that assessments of disability using the Barthel Index and Functional Independence Measure (FIM) would be dichotomised. However, as no trials included the FIM as an outcome and only three trials used the Barthel Index, the decision was made to report these data as continuous outcomes only.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group Specialised Register (March 2007), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2002, Issue 2; February 2007), MEDLINE (1966 to May 01, 2008), EMBASE (1980 to February 06, 2007), CINAHL (1982 to July 01, 2007), SPORTDiscus (1948 to February 07, 2007), PEDro ‐ The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (accessed February 07, 2007) and Digital Dissertations (accessed February 01, 2007). No language restrictions were applied.

In MEDLINE (OVID Web) the subject specific search strategy was combined with the first two phases of the Cochrane optimal search strategy (Higgins 2006). This search strategy, along with those for EMBASE (OVID Web), The Cochrane Library (Wiley InterScience), CINAHL (OVID Web), SPORTDiscus (OVID Web) and PEDro, can be found in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We contacted authors and searched reference lists of identified studies, and reviews (Anonymous 2001; Buchner 1993; Chandler 1996; Fiatarone 1993; Keysor 2001; King 1998; King 2001; Mazzeo 1998; Singh 2002).

We also handsearched the following conference proceedings:

16th International Association of Gerontology World Congress; 1997; Adelaide (Australia).

17th International Association of Gerontology World Congress; 2001; Vancouver (Canada).

Proceedings of the 13th World Congress of Physical Therapy; 1995; Washington (DC).

Proceedings of the 14th World Congress of Physical Therapy; 1999; Japan.

New Zealand Association of Gerontology Conferences ‐ 1996 Dunedin, 1999 Wellington and 2002 Auckland (New Zealand).

The 60th annual scientific meeting of the Gerontological Society of America; 2007, San Francisco, CA.

The American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine ‐ American Society of Neurorehabilitation Joint Conference; 2006, Boston, MA.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For this update (Issue 3, 2009), one author (CJL) conducted the searches. Both listed authors (CJL, NL) reviewed the titles, descriptors or abstracts identified from all literature searches to identify potentially relevant trials for full review. A copy of the full text of all trials that appeared to be potentially suitable for the review was obtained. Both authors independently used previously defined inclusion criteria to select the trials. In all cases, the reviewers reached a consensus when they initially disagreed about the inclusion of a trial. Before this update, the same method of identifying and assessing studies was used, although other members of the previous review team assisted (Latham 2003a).

Data extraction and management

Two authors independently extracted the data and recorded information on a standardised paper form. They considered all primary and secondary outcomes. If the data were not reported in a form that enabled quantitative pooling, the authors were contacted for additional information. If the authors could not be contacted or if the information was no longer available, the trial was not included in the pooling for that specific outcome.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of each trial was independently assessed by two authors (NL, CS in the first review; CJL, NL in the update) using a scoring system that was based on the Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group's former evaluation tool. The review authors were blinded to the trial authors' institution, journal that the trial was published in and the results of the trial. A third review author (CA) was consulted in the first review if a consensus about the trial quality could not be reached. No third review author was involved in the review update. The criteria for assessing internal and external validity can be found in Table 11.

1. Assessment of methodological quality scheme.

| Items | Scores | Notes |

| A. Was the assigned treatment adequately concealed prior to allocation? | 2 = method did not allow disclosure of assignment. 1 = small but possible chance of disclosure of assignment or unclear. 0 = quasi‐randomised or open list/tables. | |

| B. Were the outcomes of patients/participants who withdrew described and included in the analysis (intention‐to‐treat)? | 2 = withdrawals well described and accounted for in analysis. 1 = withdrawals described and analysis not possible. 0 = no mention, inadequate mention, or obvious differences and no adjustment. | |

| C. Were the outcome assessors blind to treatment status? | 2 = effective action taken to blind assessors. 1 = small or moderate chance of un blinding of assessors. 0 = not mentioned, or not possible. | |

| D. Were the participants blinded to the treatment status? | 2 = effective action taken to blind assessors. 1 = small or moderate chance of un blinding of assessors. 0 = not mentioned, or not possible. | |

| E. Were the treatment and control group comparable at entry? Specifically, were the groups comparable with respect to age, medical co‐morbidities (one or more of history of coronary artery disease, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, chronic lung disease), pre‐entry physical dependency (independent vs dependent in self‐care ADL) and mental status (clinical evidence of cognitive impairment, yes or no)? | 2 = good comparability of groups, or confounding adjusted for in analysis. 1 = confounding small; mentioned but not adjusted for. 0 = large potential for confounding, or not discussed. | |

| F. Were care programmes, other than the trial options, identical? | 2 = care programmes clearly identical. 1 = clear but trivial differences. 0 = not mentioned or clear and important differences in care programmes. | |

| G. Were the inclusion and exclusion criteria clearly defined? | 2 = clearly defined. 1 = inadequately defined. 0 = not defined. | |

| H. Were the interventions clearly defined? | 2 = clearly defined interventions are applied with a standardised protocol. 1 = clearly defined interventions are applied but the application protocol is not standardised. 0 = intervention and/or application protocol are poorly or not defined. | |

| I. Were the outcome measures used clearly defined? | 2 = clearly defined measures and the method of data collection and scoring are clearly described 1 = inadequately defined measures 0 = not defined. | For our primary outcome, physical disability in terms of self‐report measures of physical function, we considered the outcome clearly defined if a validated and standardised scale was used and the method of data collection was clearly described. Our secondary outcome measures included gait speed, muscle strength (e.g. one repetition maximum test, isokinetic and isometric dynamometry), balance (e.g. Berg Balance Scale, Functional Reach Test), aerobic capacity, and chair rise. These secondary outcomes were considered well defined if validated and standardised measures were used, and the method of data collection and scoring of any scales was clearly described. |

| J. Was the surveillance active and of clinically appropriate duration (i.e. at least 3 months)? | 2 = active and appropriate duration (three months follow‐up or greater). 1 = active but inadequate duration (less than three months follow‐up). 0 = not active or surveillance period not defined. |

Assessment of heterogeneity

The chi2 test was used to assess heterogeneity. In future updates, we will also assess heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plots and consideration of the I2 statistic.

Data synthesis

Where it was thought appropriate, the results from the studies were combined. Data synthesis was carried out using MetaView in Review Manager version 5.0. For continuous outcomes, mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated when similar measurement units were used. To pool outcomes using different units, standardised units (i.e. standardised mean differences, SMD) were created as appropriate. We calculated risk ratios and 95% CI for dichotomous outcomes, where possible.

If minimal statistical heterogeneity (P < 0.1) existed, fixed‐effect meta‐analysis was performed.

For trials that compared two or more different dosages of PRT versus a control group, data from the higher or highest intensity group were used in the analyses of PRT versus control.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If substantial statistical heterogeneity existed, the review authors looked for possible explanations. Specifically, we considered differences in age and baseline disability of the study participants, the methodological quality of the trials and the intensity and duration of the interventions. If the statistical heterogeneity could be explained, we considered the possibility of presenting the results as subgroup analyses. If the statistical heterogeneity could not be explained, we considered not combining the studies at all, using a random‐effects model with cautious interpretation or using both fixed‐effect and random‐effects models to assist in explaining the uncertainty around an analysis with heterogeneous studies.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the effect of differences in methodological quality. These included allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors, statements of intention‐to‐treat analysis and use of attention control.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Please see the 'Characteristics of included studies'.

One hundred and twenty‐one trials with 6700 participants at entry were included in this review. Four studies were published only as abstracts and/or theses (Collier 1997; Fiatarone 1997; Moreland 2001; Newnham 1995).

Included studies

There was variation across the trials in the characteristics of the participants, the design of the PRT programmes, the interventions provided for the comparison group and the outcomes assessed. More detailed information is provided in the 'Characteristics of included studies'; however, a brief summary is provided here.

Language

All reviewed trials were published in English.

Location

Sixty‐eight trials were conducted in the USA, 13 in Canada, 9 in Australia or New Zealand, and 31 in various European countries.

Study size

Most of these studies were small, with less than 40 participants in total, but 14 studies had 100 or more participants in total in a PRT group and a control group (Buchner 1997; Chandler 1998; Chin A Paw 2006; de Vos 2005; Ettinger 1997; Jette 1996; Jette 1999; Judge 1994; Latham 2003; Maurer 1999; McCartney 1995; Mikesky 2006; Moreland 2001; Segal 2003).

Participants

Health status

The participants in 59 trials were healthy older adults. In the remaining 62 trials, the participants had a health problem, functional limitation and/or were residing in a hospital or residential care. Thirty‐two trials included older people with a specific medical condition, including diabetes (Brandon 2003), prostate cancer (Segal 2003), osteoarthritis (Baker 2001; Ettinger 1997; Foley 2003; Maurer 1999; Mikesky 2006; Schilke 1996; Topp 2002), osteoporosis/osteopenia (Liu‐Ambrose 2005), peripheral arterial disease (Hiatt 1994; McGuigan 2001), recent stroke (Moreland 2001; Ouellette 2004), congestive heart failure (Brochu 2002; Pu 2001; Selig 2004; Tyni‐Lenne 2001), chronic airflow limitation (Casaburi 2004; Kongsgaard 2004; Simpson 1992), clinical depression (Sims 2006; Singh 1997; Singh 2005), low bone‐mineral density (Parkhouse 2000), hip replacement due to osteoarthritis (Suetta 2004), hip/lower limb fracture (Mangione 2005; Miller 2006), obesity (Ballor 1996), chronic renal insufficiency (Castaneda 2001; Castaneda 2004) and coronary artery bypass graft surgery three or more months before exercise training (Maiorana 1997). Nineteen other trials recruited participants who did not have a specific health problem, but were considered frail and/or to have a functional limitation (Bean 2004; Boshuizen 2005; Chandler 1998; Fiatarone 1994; Fiatarone 1997; Fielding 2002; Hennessey 2001; Jette 1999; Krebs 2007; Latham 2003; Manini 2005; McMurdo 1995; Mihalko 1996; Miszko 2003; Newnham 1995; Skelton 1996; Sullivan 2005; Topp 2005; Westhoff 2000). In nine trials, the participants resided in a rest‐home or nursing home (Baum 2003; Bruunsgaard 2004; Chin A Paw 2006; Fiatarone 1994; Hruda 2003; McMurdo 1995; Mihalko 1996; Newnham 1995; Seynnes 2004). In addition, two trials included participants who were in hospital at the time the exercise programme was carried out (Donald 2000; Latham 2001). In the other trials, most or all of the participants lived in the community.

Gender

Most studies included both men and women, although 10 trials included men only (Fatouros 2002; Hagerman 2000; Haykowsky 2000; Hepple 1997; Izquierdo 2004; Katznelson 2006; Kongsgaard 2004; Maiorana 1997; Segal 2003; Sousa 2005) and 22 trials included women only (Bean 2004; Brochu 2002; Charette 1991; Damush 1999; Fahlman 2002; Flynn 1999; Frontera 2003; Haykowsky 2005; Jones 1994; Kallinen 2002; Liu‐Ambrose 2005; Macaluso 2003; Madden 2006; Nelson 1994; Nichols 1993; Parkhouse 2000; Pu 2001; Rhodes 2000; Sipila 1996; Skelton 1995; Skelton 1996; Taaffe 1996).

Age

In 49 studies the mean or median age of the participants was between 60 and 69 years old; in 57 studies, the mean/median age was between 70 and 79 years old; and in 20 studies, it was 80 years old or over.

Lifestyle

Fifteen studies specifically recruited participants with a sedentary lifestyle (Ades 1996; Beneka 2005; Charette 1991; Fatouros 2002; Fatouros 2005; Frontera 2003; Kalapotharakos 2005; Katznelson 2006; Malliou 2003; Mihalko 1996; Parkhouse 2000; Pollock 1991; Rhodes 2000; Topp 1996; Tsutsumi 1997).

PRT Programmes

Settings

Most training programmes took place in gym or clinic settings with all sessions fully supervised. Ten studies were entirely home‐based (Baker 2001; Chandler 1998; Fiatarone 1997; Jette 1996; Jette 1999; Katznelson 2006; Krebs 2007; Latham 2003; Mangione 2005; McMurdo 1995), while 12 additional studies carried out some of the training at home and some in gym/clinic settings (Boshuizen 2005; Ettinger 1997; Jones 1994; Mikesky 2006; Simoneau 2006; Skelton 1995; Skelton 1996; Topp 1993; Topp 1996; Topp 2002; Topp 2005; Westhoff 2000).

Intensity

The resistance training programmes in most trials (i.e. 83 trials) involved high intensity training. Most of these trials used specialized exercise machines for training. Thirty‐six trials used low‐intensity to moderate‐intensity training, with most using elastic tubing or bands. All of the high‐intensity training was carried out at least in part in gym or clinic based settings, with the exception of two published trials (Baker 2001; Latham 2003) and a trial published as an abstract (Fiatarone 1997).

Frequency and duration

The frequency of training was consistent across studies, with the exercise programme carried out two to three times a week in almost all trials. Two exceptions to this were the two trials conducted in hospital which carried out the exercises on a daily basis (Donald 2000; Latham 2001). In contrast, there was large variation in the duration of the exercise programmes and the number of exercises performed in each programme. Although most of the programmes (i.e. 71 trials) were eight to 12 weeks long, the duration ranged from two to 104 weeks. In 54 trials the exercise programme was longer than 12 weeks. The number of exercises performed also varied, from one to more than 14.

Adherence

Data about adherence to the PRT programme are reported in the 'Characteristics of included studies'. These data are difficult to interpret because different definitions for adherence or compliance were used across the trials. In most trials, adherence referred to the percentage of exercise sessions attended compared with the total number of prescribed sessions and in this case the reported adherence rate is high (i.e. greater than 75%). Many trials only included participants that completed the entire trial (i.e. excluded drop‐outs), while some trials reported these data with drop‐outs included.

Comparison interventions

Comparisons were conducted between a PRT group and a control group and between a PRT group and a group that received other type of intervention. In addition, comparisons between high intensity or frequency and low intensity or frequency, different sets, and different types of contraction training were also conducted. Multiple comparisons within a trial were possible when the trial included more than two groups that were relevant to the review. Twenty‐eight trials had three groups. Among these trials, 14 included an aerobic training group in addition to a PRT group and a control group (Ettinger 1997; Fahlman 2002; Fatouros 2002; Haykowsky 2005; Hiatt 1994; Jubrias 2001; Kallinen 2002; Madden 2006; Malliou 2003; Mangione 2005; Pollock 1991; Sipila 1996; Topp 2005; Wood 2001), and seven included two PRT groups that exercised at different intensities in addition to a control group (de Vos 2005; Fatouros 2005; Hortobagyi 2001; Hunter 2001; Kalapotharakos 2005; Seynnes 2004; Singh 2005). One trial had a PRT group, a functional training group, and a PRT with functional training group (Manini 2005). The other six trials either had a balance training group (Judge 1994), functional training group (Chin A Paw 2006; de Vreede 2007), an endurance training group (Sipila 1996), a mobility training group (McMurdo 1995), or a power training group (Miszko 2003) in addition to a PRT group and a control group. One trial had three groups that exercised at three different frequencies in addition to a control group (Taaffe 1999).

PRT versus controls

One hundred and four trials compared PRT with a control group. The control group might receive no exercise, regular care, or attention control (i.e. the control group receives matching attention as the intervention group).

Comparisons of PRT dosage

High intensity versus low intensity

Ten studies compared PRT programmes at high intensity versus low intensity (Beneka 2005; Fatouros 2005; Harris 2004; Hortobagyi 2001; Seynnes 2004; Singh 2005; Sullivan 2005; Taaffe 1996; Tsutsumi 1997; Vincent 2002).

Different frequencies of PRT

Two trials ( DiFrancisco 2007 ; Taaffe 1999) compared PRT performed at different frequencies (i.e. once, twice, or three times per week).

Different sets

One study compared PRT at different sets, i.e. 3‐sets versus 1‐set (Galvao 2005). One set of exercise means several continuous repeated movements.

Concentric versus eccentric training

One study (Symons 2005) compared PRT at two types of contraction training: concentric versus eccentric training. During concentric training, speed was added at concentric contraction phase and vise versa for eccentric training.

PRT versus aerobic training

PRT was compared with aerobic (endurance) training in 17 trials (Ballor 1996; Buchner 1997; Earles 2001; Ettinger 1997; Fatouros 2002; Hepple 1997; Hiatt 1994; Izquierdo 2004; Jubrias 2001; Kallinen 2002; Madden 2006; Malliou 2003; Mangione 2005; Pollock 1991; Sipila 1996; Topp 2005; Wood 2001).

PRT versus balance training

One study compared PRT with balance training (Judge 1994). Balance training included training on a computerized balance platform and non‐platform training (i.e. balancing on different surfaces, with varying bases of support, with different perturbations). Both exercise programmes were performed in a research center three times per week for three months.

PRT versus functional training

Three studies compared PRT to functional training (Chin A Paw 2006; de Vreede 2007; Manini 2005). Functional training involves game‐like activities or exercise movements in various directions. In Chin A Paw 2006, functional training involved game‐like or cooperative activities; and in de Vreede 2007, functional training involved moving with a vertical or horizontal component, carrying an object, and changing position between lying, sitting, and standing.

PRT versus flexibility training

One study compared PRT with flexibility training (Barrett 2002).

Power training

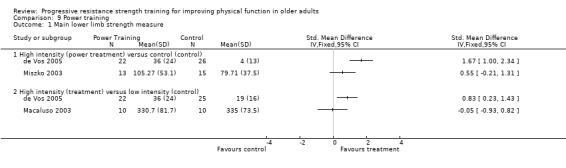

Power training refers to the type of PRT that emphasizes speed. Three studies applied this type of training (de Vos 2005; Macaluso 2003; Miszko 2003).

Outcomes

A variety of outcomes were assessed in these studies: the primary outcomes of physical function and secondary outcomes of measures of impairment and functional limitation.

Excluded studies

The excluded studies and their reasons for exclusion are listed in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies'. The main reasons for exclusion were that the study was not a randomised controlled trial or that the study design caused serious threats to its internal validity (57 trials); the studies used a combination of exercise interventions (i.e. not resistance training alone) (51 trials); the strength training programme did not use a progressive resistance approach (32 trials); and some participants were not elderly (i.e. did not have a mean age of at least 60 years and/or included some participants below 50 years of age) (25 trials).

Studies awaiting assessment

Nine trials were identified on a search update to May 2008, and a further trial was added after a referee's comment.

Risk of bias in included studies

Methodological quality scores of each item for all included studies are given in Table 12. A summary of the findings of key indicators of internal validity are listed below.

2. Quality rating of trials.

| Study | Concealed allocation | ITT | Assessor blind | Participants blind | Compable at entry | Identical care | Inclusion/ exclusion | Interventions defined | Outcomes defined |

| Ades 1996 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Baker 2001 | 2 | 2/0 | 2/0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Balagopal 2001 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Ballor 1996 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Barrett 2002 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Baum 2003 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Bean 2004 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Beneka 2005 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Bermon 1999 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Boshuizen 2005 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Brandon 2000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Brandon 2003 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Brochu 2002 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Bruunsgaard 2004 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Buchner 1997 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Casaburi 2004 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Castaneda 2001 | 1 | 1 | 2/0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Castaneda 2004 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Chandler 19981 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Charette 1991 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Chin A Paw 2006 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Collier 1997 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Damush 1999 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| de Vos 20051 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| de Vreede 2007 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| DeBeliso 2005 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| DiFrancisco 2007 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Donald 2000 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Earles 2001 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ettinger 1997 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Fahlman 2002 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Fatouros 2002 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Fatouros 2005 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Fiatarone 1994 | 1 | 2 | 2/0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Fiatarone 1997 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Fielding 2002 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Flynn 1999 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Foley 2003 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Frontera 2003 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Galvao 2005 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Hagerman 2000 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Harris 2004 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Haykowsky 2005 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Haykowsky 2000 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Hennessey 2001 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Hepple 1997 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Hiatt 1994 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Hortobagyi 2001 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Hruda 2003 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Hunter 2001 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Izquierdo 2004 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Jette 1996 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Jette 1999 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Jones 1994 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Jubrias 2001 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Judge 1994 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Kalapotharakos 2005 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Kallinen 2002 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Katznelson 2006 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Kongsgaard 2004 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Krebs 2007 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Lamoureux 2003 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Latham 2001 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Latham 2003 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Liu‐Ambrose 2005 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Macaluso 2003 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Madden 2006 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Maiorana 1997 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Malliou 2003 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Mangione 2005 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Manini 2005 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Maurer 1999 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| McCartney 1995 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| McGuigan 2001 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| McMurdo 1995 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Mihalko 1996 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Mikesky 2006 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Miller 2006 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Miszko 2003 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Moreland 2001 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nelson 1994 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Newnham 1995 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Nichols 1993 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Ouellette 2004 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Parkhouse 2000 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Perrig‐Chiello 1998 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pollock 1991 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Pu 2001 | 1 | 2 | 2/0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Rall 1996 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Reeves 2004 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Rhodes 2000 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Schilke 1996 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Schlicht 1999 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Segal 2003 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Selig 2004 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Seynnes 2004 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Simons 2006 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Simoneau 2006 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Simpson 1992 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Sims 2006 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Singh 1997 | 1 | 0 | 2/0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Singh 2005 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Sipila 1996 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Skelton 1995 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Skelton 1996 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Sousa 2005 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Suetta 2004 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Sullivan 2005 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0/2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Symons 2005 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Taaffe 1996 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Taaffe 1999 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Thielman 2004 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Topp 1993 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Topp 1996 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Topp 2002 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Topp 2005 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Tracy 2004 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Tsutsumi 1997 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Tyni‐Lenne 2001 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Vincent 2002 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Westhoff 2000 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Wieser 2007 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Wood 2001 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Note: 2/0 indicates that different standards used to assess different outcomes in the same study NA = not available, no full report published

Allocation concealment

Eleven studies provided some information about the method of randomisation that suggested that randomisation was probably concealed (i.e. the use of concealed envelopes or the randomisation was generated by an independent person) (Baker 2001; Chin A Paw 2006; Donald 2000; Foley 2003; Jette 1999; Latham 2001; Latham 2003; McMurdo 1995; Moreland 2001; Sims 2006; Sullivan 2005). Nineteen studies used randomisation list/table but allocation concealment was unclear (Barrett 2002; Baum 2003; Buchner 1997; de Vos 2005; de Vreede 2007; DiFrancisco 2007; Ettinger 1997; Krebs 2007; Liu‐Ambrose 2005; Maurer 1999; Miller 2006; Schilke 1996; Segal 2003; Singh 1997; Singh 2005; Skelton 1995; Suetta 2004; Vincent 2002; Wieser 2007).

Loss to follow‐up

Some trials had high drop‐out rates, with several studies reporting more than 20% of their participants were lost to follow‐up (Bruunsgaard 2004; Chin A Paw 2006; DeBeliso 2005; Donald 2000; Katznelson 2006; Kongsgaard 2004; Mangione 2005; Mikesky 2006; Topp 1996). In some studies there was clear evidence of bias associated with the deliberate exclusion of patients such as those who failed to adhere to the exercise programme (Izquierdo 2004; Madden 2006; Topp 1996; Vincent 2002) or those who had adverse responses (Hagerman 2000).

Intention‐to‐treat analysis

Twenty‐two studies stated that they used intention‐to‐treat analysis (Baker 2001; Barrett 2002; Baum 2003; Buchner 1997; Chin A Paw 2006; Ettinger 1997; Fiatarone 1994; Foley 2003; Judge 1994; Katznelson 2006; Latham 2003; Liu‐Ambrose 2005; Macaluso 2003; Mikesky 2006; Miller 2006; Moreland 2001; Nelson 1994; Ouellette 2004; Pu 2001; Segal 2003; Sims 2006; Sullivan 2005).

Blinded outcome assessment

Thirty‐three studies stated that they used a blinded assessor for all outcome measures (Barrett 2002; Baum 2003; Bean 2004; Boshuizen 2005; Buchner 1997; Casaburi 2004; Castaneda 2004; Chin A Paw 2006; de Vreede 2007; Ettinger 1997; Foley 2003; Haykowsky 2005; Jette 1996; Jette 1999; Jones 1994; Judge 1994; Kalapotharakos 2005; Katznelson 2006; Krebs 2007; Latham 2003; Liu‐Ambrose 2005; Mangione 2005; Maurer 1999; McMurdo 1995; Mikesky 2006; Miller 2006; Moreland 2001; Newnham 1995; Segal 2003; Sims 2006; Singh 2005; Sullivan 2005; Westhoff 2000).

Eight additional studies used a blinded outcome assessor for some, but not all outcome assessments (Baker 2001; Castaneda 2001; de Vos 2005; Fiatarone 1994; Ouellette 2004; Pu 2001; Singh 1997; Suetta 2004).

Blinding of participants

Blinding of participants is difficult in studies of exercise interventions. However, the use of attention control groups can help to minimise bias. Thirty‐six studies used some type of attention programme for the control group (Baker 2001; Baum 2003; Bean 2004; Brochu 2002; Bruunsgaard 2004; Castaneda 2001; Castaneda 2004; Chin A Paw 2006; Damush 1999; Ettinger 1997; Fiatarone 1994; Fiatarone 1997; Foley 2003; Judge 1994; Kongsgaard 2004; Latham 2003; Liu‐Ambrose 2005; Mangione 2005; Maurer 1999; McCartney 1995; McMurdo 1995; Mihalko 1996; Mikesky 2006; Miller 2006; Miszko 2003; Moreland 2001; Newnham 1995; Ouellette 2004; Pu 2001; Seynnes 2004; Simons 2006; Sims 2006; Singh 1997; Suetta 2004; Topp 1993; Topp 1996). In 10 of these studies, the control group received 'sham' exercise programmes (Bean 2004; Brochu 2002; Castaneda 2001; Castaneda 2004; Kongsgaard 2004; Liu‐Ambrose 2005; Mikesky 2006; Ouellette 2004; Pu 2001; Seynnes 2004).

Duration of follow‐up

Five studies continued to follow up the participants after intervention had ended (Buchner 1997; Fiatarone 1994; Moreland 2001; Newnham 1995; Sims 2006). Two of these followed up falls for more than one year (Buchner 1997; Fiatarone 1994).

Effects of interventions

Eleven studies did not report final means and standard deviations for some or all of their outcome measures but instead reported baseline mean scores and mean change in scores from baseline (Baum 2003; Bean 2004; Buchner 1997; Chandler 1998; Fiatarone 1994; Hiatt 1994; Jette 1996; Lamoureux 2003; Madden 2006; Sullivan 2005; Topp 1996). If additional data could not be obtained from the investigators, the final mean score was estimated by adding the change in score to the baseline score, and the standard deviation of the baseline score was used for the final score.

Four studies did not report standard deviations for some or all of their outcome measures but instead reported standardized errors (Ouellette 2004; Seynnes 2004; Suetta 2004; Topp 2002). The standard deviations were estimated based on reported standardized errors and sample sizes.

Eight studies did not report numerical results of outcomes of interest for the purpose of this review and additional data were not provided by the investigators (Castaneda 2004; Fielding 2002; Harris 2004; Haykowsky 2005; Krebs 2007; Miller 2006; Topp 2005; Wieser 2007).

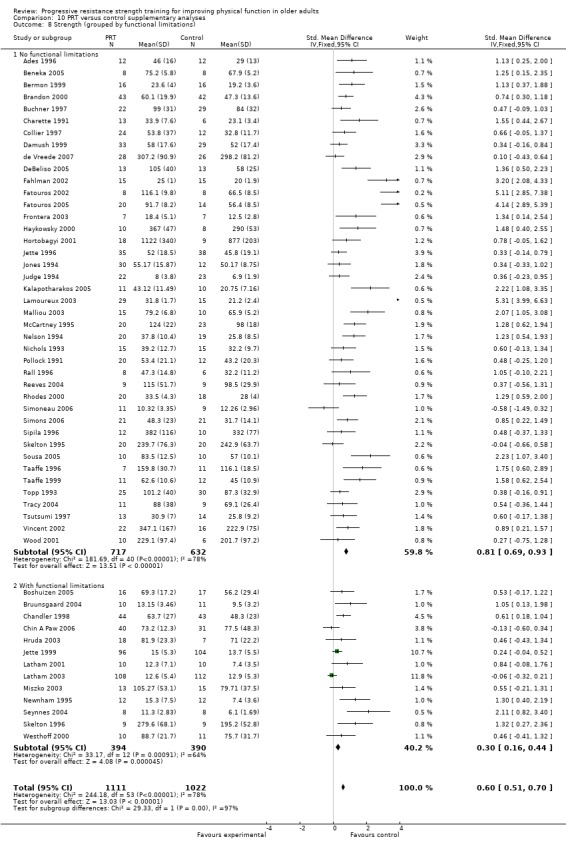

PRT versus control

Measures of physical (dis)ability/HRQOL (complex physical activities)

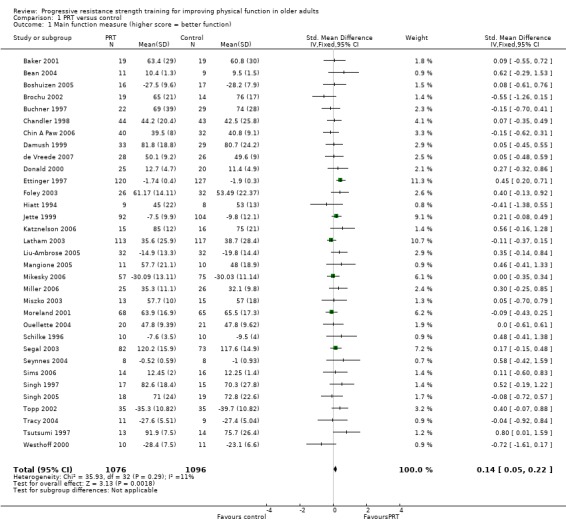

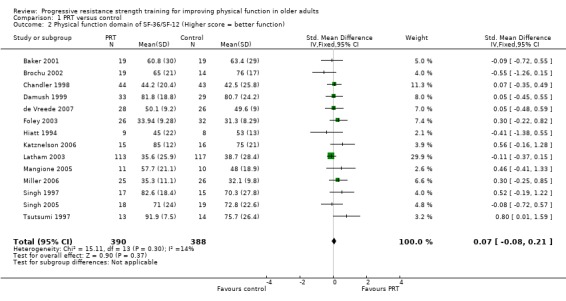

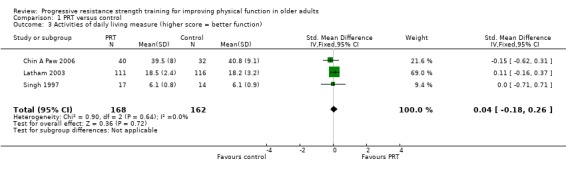

The main function (disability) measures from trials that had appropriate data were pooled using the standardised mean difference (SMD) and a fixed‐effect model. Because studies measured function in scales with different directions, a higher score indicates either less disability/better function or more disability/poor function, a transformation was conducted to make all the scales point in the same direction. Mean values from trials in which a higher score indicates more disability/poor function were multiplied by ‐1. There is a significant effect of PRT in decreasing disability (seeFigure 1; Analysis 1.1 : 33 trials, 2172 participants; SMD 0.14, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.22). When the physical function domain of SF‐36 or SF‐12 was pooled from 14 studies (n = 778) using a fixed‐effect model, no difference was found (Analysis 1.2 : SMD 0.07, 95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.21). No difference was found from the pooled results of three trials for activity of daily living measures (Analysis 1.3). A number of studies had function measures (i.e. measures of activity, function or HRQOL) that could not be pooled. The available data from these measures are reported in Table 13.

1.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 PRT versus control, outcome: 1.1 Main function measure (higher score = better function).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 1 Main function measure (higher score = better function).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 2 Physical function domain of SF‐36/SF‐12 (Higher score = better function).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 3 Activities of daily living measure (higher score = better function).

3. Functional or quality of life measures that could not be pooled.

| Study | Outcome Measure | Treatment Group | Control Group |

| Baum 2003 | Physical performance test at 6 month. Mean = baseline score + change score. SD was not reported. | 9.2 | 8.1 |

| Buchner 1997 | mean change in number of independent IADL's | mean 0.1 (SD 0.7) | mean 0.2 (SD 0.7) |

| Donald 2000 | Barthel Index (actual data not in paper) | no significant difference | |

| Fiatarone 1994 | ankle activity monitors (counts/day) | mean change 3412 (SD 1700) | mean change ‐1230 (SD 1670) |

| Fiatarone 1997 | overall self‐reported activity level (measure not specified) | significant improvement (p<0.05) in exercise group | NR |

| Fielding 2002 | SF‐36‐PF | No significant differences between high intensity and low intensity groups | |

| Jette 1996 | SF‐36 ‐ PF (actual data not reported) | no significant difference between groups (data not reported) | |

| Kongsgaard 2004 | three ADLs of a questionnaire developed by the Danish Institute of Clinical Epidemiology | Actual data not reported. The author stated that the self‐reported ADL level was significantly higher in the Ex group than in the control group | |

| Krebs 2007 | SF‐36. 7 people (2 in PRT, 5 in Functional training) reported improvement in the SF‐36 items | ||

| Maiorana 1997 | Physical Activity Questionnaire (no reference) self report | mean 209.8 (SD 142.9) kJ/kg | mean 250.1 (SD 225) kJ/kg |

| Maurer 1999 | SF‐36 PF (no SD/SE reported) | mean 50.3 | mean 49.2 |

| Maurer 1999 | WOMAC section C (no SD/SE reported) | 464.4 | 606.6 |

| Maurer 1999 | Aims Mobility (no SD/SE reported) | 1.28 | 1.21 |

| McMurdo 1995 | Barthel Index (medians reported) | median change 0 (range ‐1 to 2) | median change control 0 (range ‐1 to 1) |

| Mihalko 1996 | adapted version of Lawton and Brody's IADL scale (higher = better, not pooled because study was cluster randomised) | mean 105 (SD 12) | mean 68 (SD 25) |

| Mikesky 2006 | SF‐36 physical function at 30 month (the intervention was 1 ‐ year) | n =81, mean = 65.37 (SD = 25.05) | n = 79, mean = 63.88 (SD = 25.48) |

| Nichols 1993 | Blair Seven‐day recall Caloric Expenditure (KCalories) | not significantly altered | not significantly altered |

| Schilke 1996 | AIMS mobility score (actual data not reported) | "no significant differences between or within groups" | |

| Singh 1997 | IADL (Lawton Brody Scale) | mean 23.4 (SD 0.4) | mean 23.9 (SD 0.1) |

| Skelton 1996 | Human Activity Profile ‐ (only reported training groups % change and the P‐value of the change) | 3.9% change3.9% change | NR |

| Skelton 1996 | Human Activity Profile ‐ Max Activity Score | 0% change | NR |

| Skelton 1995 | Human Activity Profile | no difference from baseline | no difference from baseline |

| Thielman 2004 | Rivermead Motor Assessment | Significant improvement was found for people in the control group with low‐level function | |

| Tyni‐Lenne 2001 | Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (lower score = better QOL, medians reported) | median 19 (range 0‐61) | median 44 (range 3‐103) |

Measures of impairment

Strength

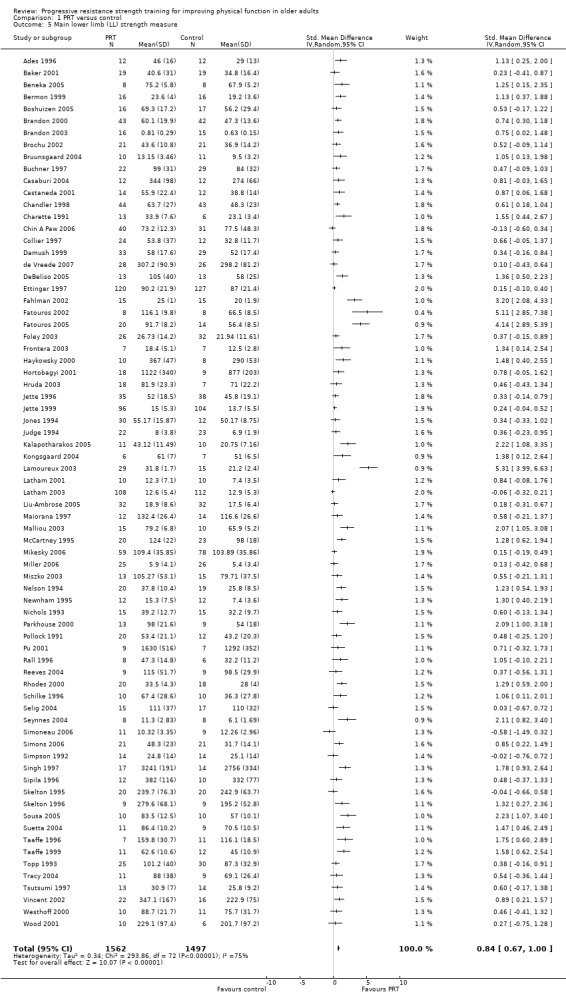

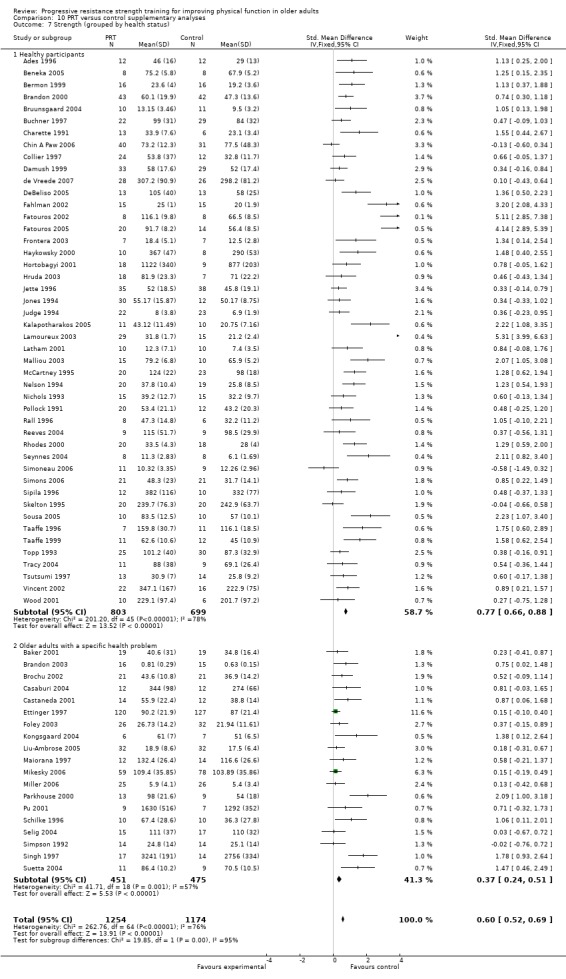

Many different muscle groups were tested and a number of methods were used to evaluate muscle strength in these trials. To minimise clinical heterogeneity, data were pooled from one muscle group. The leg extensor group of muscles was selected since this group was the most frequently evaluated. The effect size was calculated using standardised mean difference (SMD) to allow the pooling of data that used different units of measurement. Seventy‐three studies involving 3059 participants reported the effect of resistance training on a lower‐limb extensor muscle group and provided data that allowed pooling. A moderate‐to‐large beneficial effect was found (Analysis 1.5: SMD 0.84, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.00, random‐effects model; fixed‐effect model: SMD 0.53, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.61).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 5 Main lower limb (LL) strength measure.

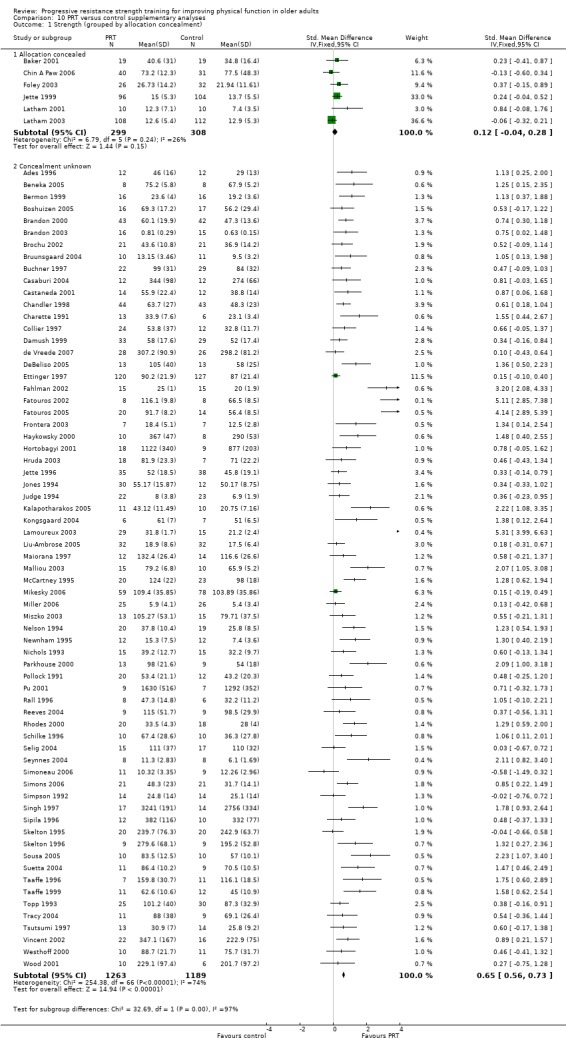

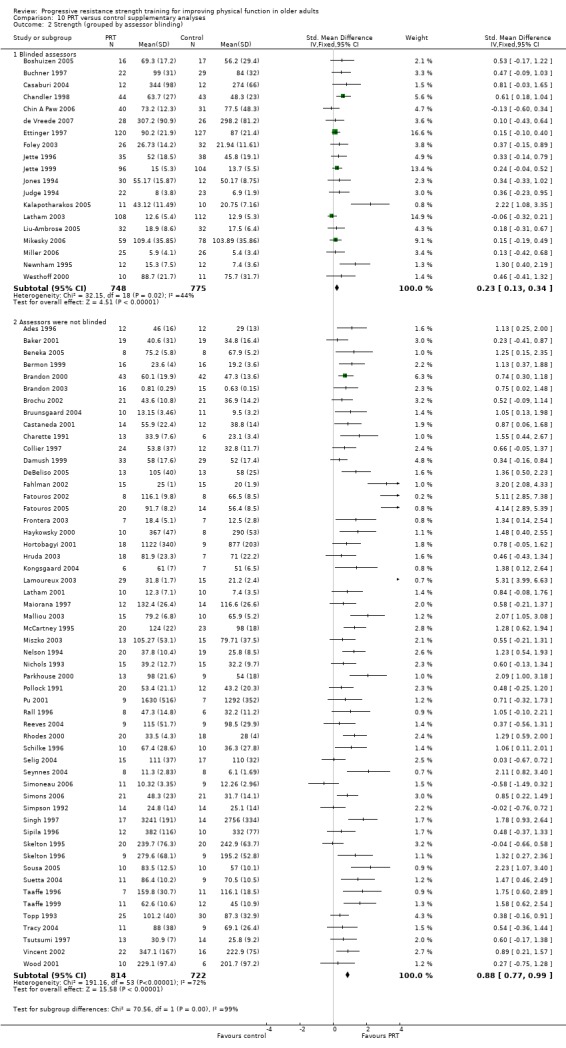

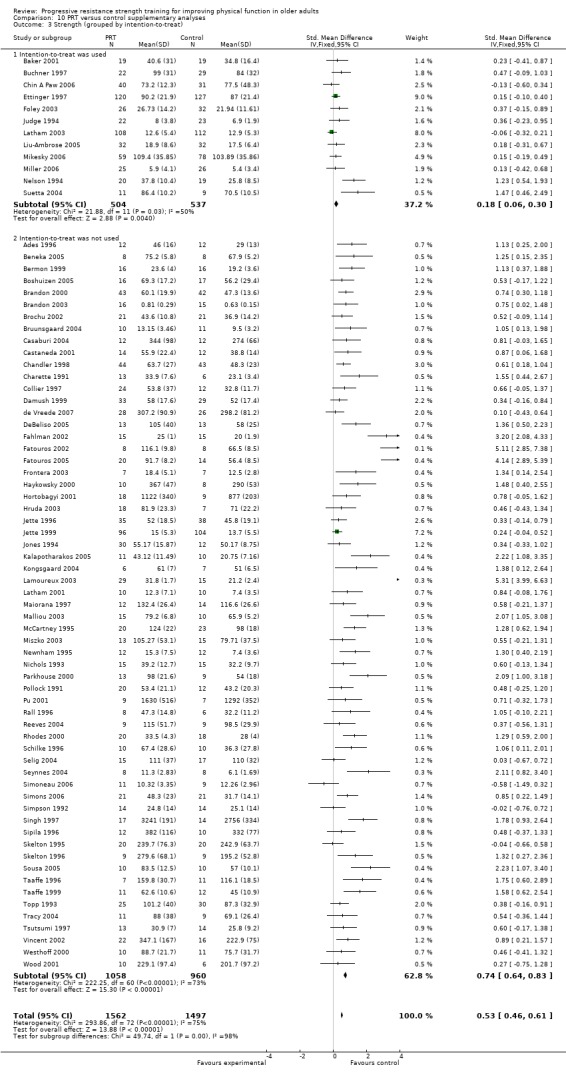

Supplementary analyses

Significant statistical heterogeneity was apparent in these data (P < 0.0001). Since a large number of studies assessed this outcome, it was possible to explore this heterogeneity by stratifying the data. Differences in treatment effects due to the quality of the trials were investigated. We also explored subgroups of trials that were based on the design of the treatment programmes and the characteristics of the participants.

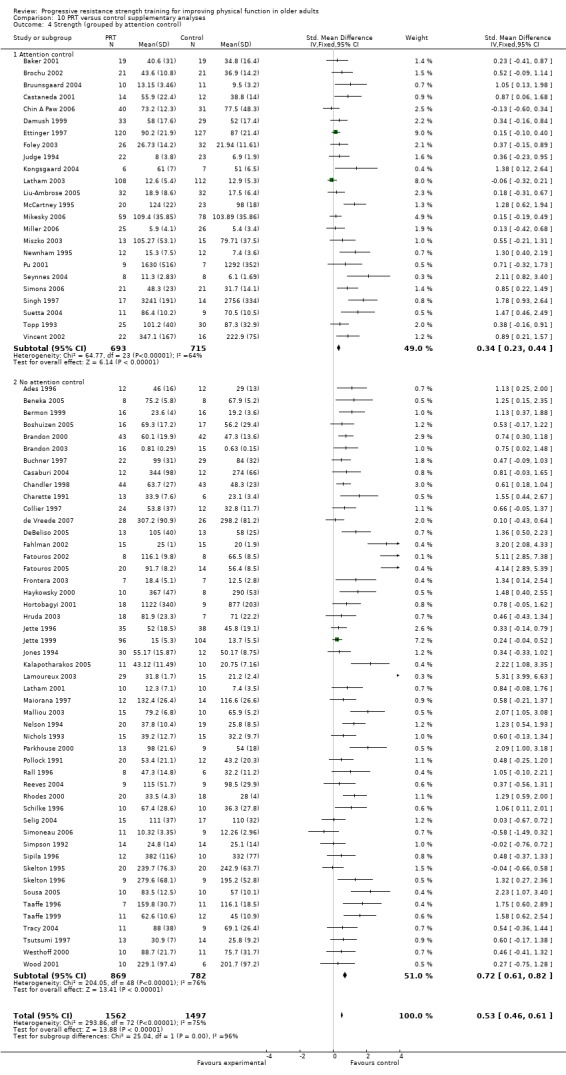

To explore the effect of data quality on treatment effects, data were stratified by four design features that are associated with internal validity. These are allocation concealment; blinded assessors; intention‐to‐treat analysis (ITT); and attention control groups. The fixed‐effect model was used throughout in order to obtain the results for the test for subgroup differences. The effect was smaller in the few studies with clear allocation concealment (6 trials, 607 participants) compared with studies with unknown concealment of allocation (67 trials, 2452 participants): Analysis 10.1: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 32.69, df = 1 (P < 0.00001). The effect was also smaller in studies that used blinded assessors (19 trials, 1523 participants) compared with studies that did not use blinded assessors (54 trials, 1536 participants): Analysis 10.2: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 70.56, df = 1 (P < 0.00001). This was also true for studies that used intention‐to‐treat analysis (ITT) (12 trials, 1041 participants) versus no ITT (61 trials, 2018 participants): Analysis 10.3: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 49.74, df = 1 (P < 0.00001). It is noticable that trials that applied better design features tend to be the larger trials. The effect was smaller when attention control groups were used (attention control: 24 studies, 1408 participants, no attention control: 49 studies, 1651 participants): Analysis 10.4: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 25.04, df = 1 (P < 0.00001).

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 PRT versus control supplementary analyses, Outcome 1 Strength (grouped by allocation concealment).

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 PRT versus control supplementary analyses, Outcome 2 Strength (grouped by assessor blinding).

10.3. Analysis.

Comparison 10 PRT versus control supplementary analyses, Outcome 3 Strength (grouped by intention‐to‐treat).

10.4. Analysis.

Comparison 10 PRT versus control supplementary analyses, Outcome 4 Strength (grouped by attention control).

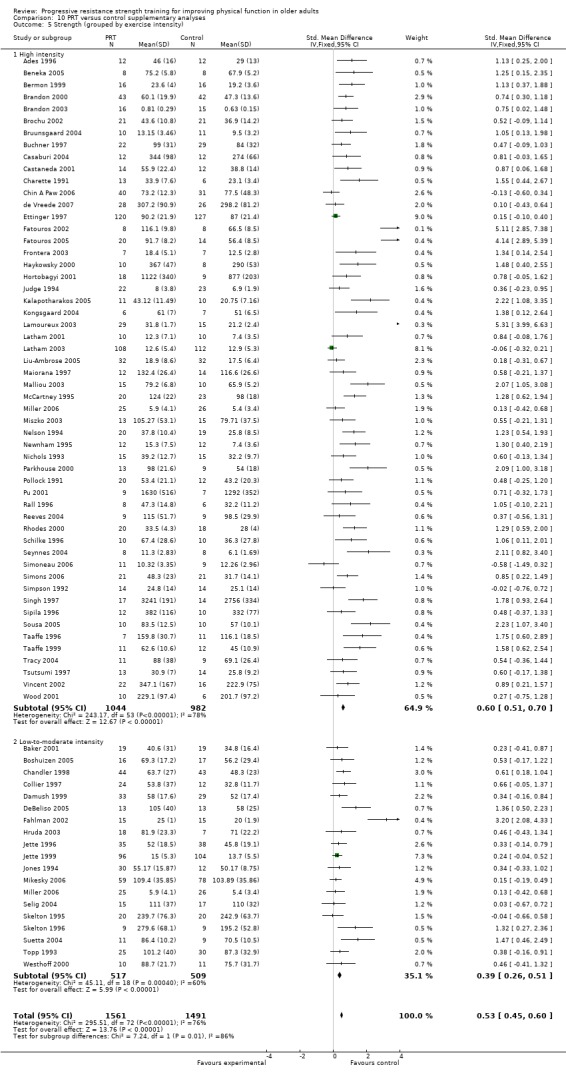

Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore the effect of PRT when the design of the exercise programme and the characteristics of the participants differed. The effect of differences in the exercise programme was explored by examining effect estimates in studies that used different intensity and duration. High intensity strength training was compared with low to moderate intensity training. This analysis suggests that while both training approaches are probably effective in improving strength, higher intensity training (54 trials, 2026 participants) has a larger effect on strength than low to moderate intensity training (19 trials, 1033 participants): Analysis 10.5: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 7.24, df = 1 (P = 0.007). Longer duration programmes (i.e. greater than 12 weeks) were also compared with shorter duration programmes (less than 12 weeks). The duration of the trial appeared to have minimal effect on the strength outcome (< 12 weeks: 20 trials, 828 participants; > 12 weeks: 36 trials, 1736 participants): Analysis 10.6: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.04, df = 1 (P = 0.85).

10.5. Analysis.

Comparison 10 PRT versus control supplementary analyses, Outcome 5 Strength (grouped by exercise intensity).

10.6. Analysis.

Comparison 10 PRT versus control supplementary analyses, Outcome 6 Strength (grouped by exercise duration).

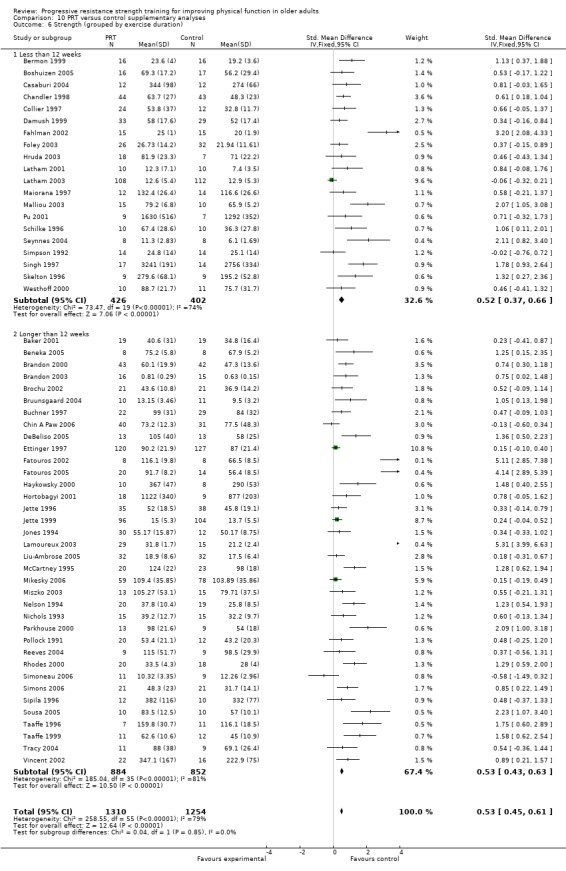

Treatment effects in older people with and without a chronic disease (or functional limitation) were also assessed. Again, resistance training appeared to be effective in improving strength in both groups of older people, but there was statistical heterogeneity in the effects. Studies that included participants who had specific health problems and/or functional limitations were compared with studies that included only healthy older people. The effect in older adults who were healthy has a larger effect size than older adults with specific health problems (healthy older adults: 46 trials, 1502 participants; older adults with specific health problems: 19 trials, 926 participants): Analysis 10.7: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 19.85, df = 1 (P < 0.00001). In addition, PRT in studies that included older adults who had a physical disability or functional limitation appeared to be less effective than in those that included older adults who did not have functional limitations (people with functional limitations: 13 studies, 784 participants; people with no functional limitations: 41 studies, 1349 participants): Analysis 10.8: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 29.33, df = 1 (P < 0.00001). However, this result could be confounded by the intensity of the PRT programmes, as almost all programmes that included people with functional limitations were carried out at a low to moderate intensity. There were insufficient data available to compare the results by gender (men only: 5 trials with 107 participants; women only: 15 trials with 486 participants) .

10.7. Analysis.

Comparison 10 PRT versus control supplementary analyses, Outcome 7 Strength (grouped by health status).

10.8. Analysis.

Comparison 10 PRT versus control supplementary analyses, Outcome 8 Strength (grouped by functional limitations).

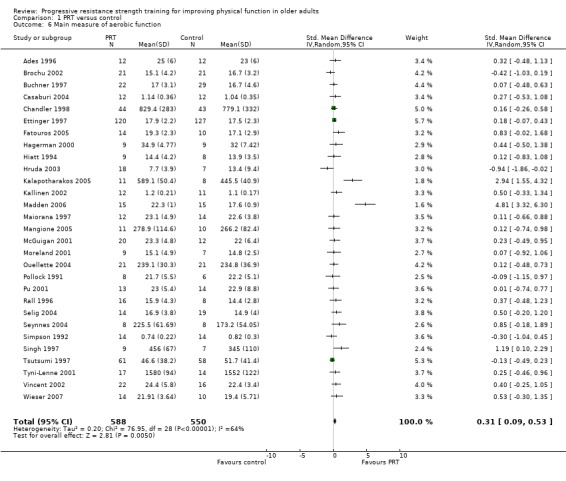

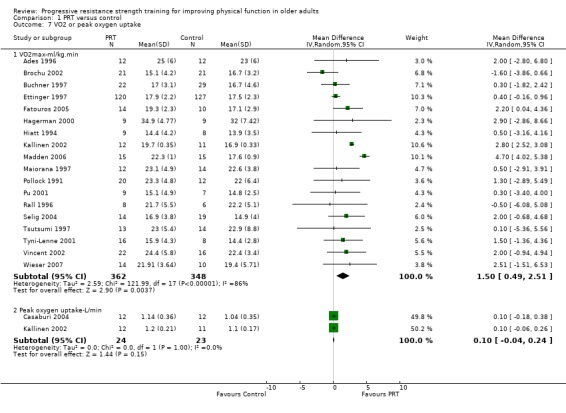

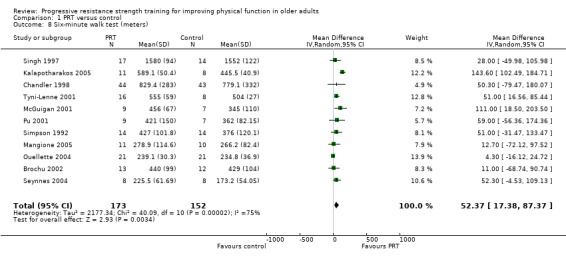

Aerobic capacity

The main measure of aerobic capacity was pooled from 29 studies (n = 1138) using a random‐effects model. These results suggest that PRT has a significant effect on aerobic capacity (Analysis 1.6 : SMD 0.31, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.53). Further analyses were performed for three specific measures of aerobic capacity: VO2 max (ml/kg/min), peak oxygen uptake (L/min) and the six‐minute walk test (meters). A consistent significant effect was found for VO2 max (Analysis 1.7: 18 trials, n = 710, MD 1.5 ml/kg/min, 95% CI 0.49 to 2.51). Similarly, a significant positive effect was found for the six‐minute walk test (Analysis 1.8: 11 trials, n = 325, MD 52.37 meters, 95% CI 17.38 to 87.37).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 6 Main measure of aerobic function.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 7 VO2 or peak oxygen uptake.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 8 Six‐minute walk test (meters).

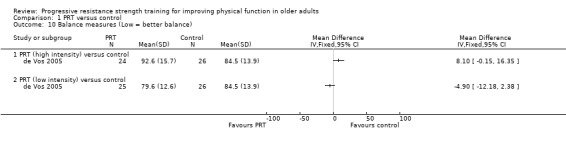

Measures of functional limitations (simple physical activities)

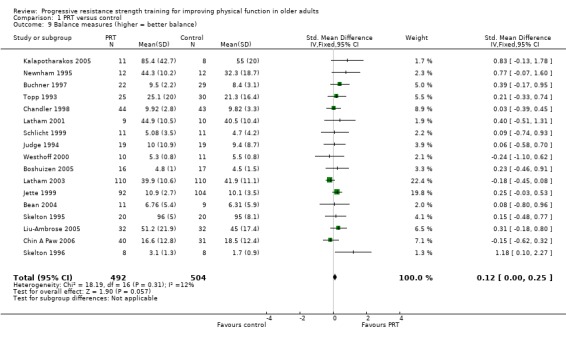

Balance/postural control

Results from all balance performance measures were pooled using SMD and a fixed‐effect model. Data pooled from 17 studies with 996 participants showed a small but non‐significant benefit (higher score indicates better balance) for balance (Analysis 1.9: SMD 0.12 (95% CI 0.00 to 0.25).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 9 Balance measures (higher = better balance).

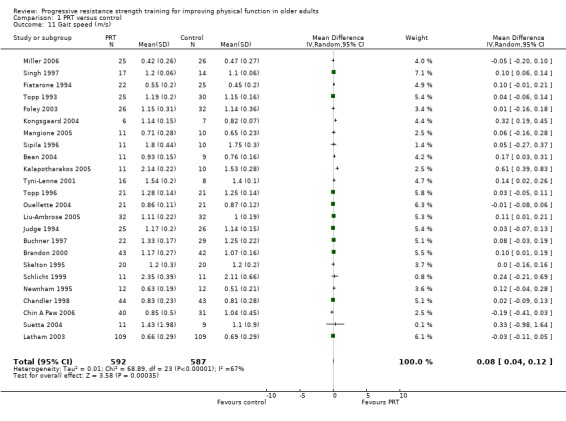

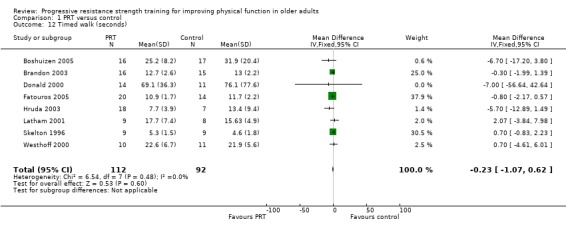

Gait speed

Two different measures of walking speed were used: gait speed (measured in meters per second) and timed walk (i.e. time to walk a set distance, measured in seconds). A higher gait speed score indicates faster mobility, while a higher timed walk score indicates slower mobility. Because of this difference, these data were analyzed separately. Data for gait speed were available from 24 studies that included 1179 participants (Analysis 1.11 : MD 0.08 m/s, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.12, random‐effects). This indicated that PRT has a modest but significant beneficial effect on gait speed. Only eight trials measured the timed walk (seconds) as an outcome measure and no evidence of an effect was found (Analysis 1.12; 204 participants, MD ‐0.23 seconds, 95% CI ‐1.07 to 0.62, fixed‐effect).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 11 Gait speed (m/s).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 12 Timed walk (seconds).

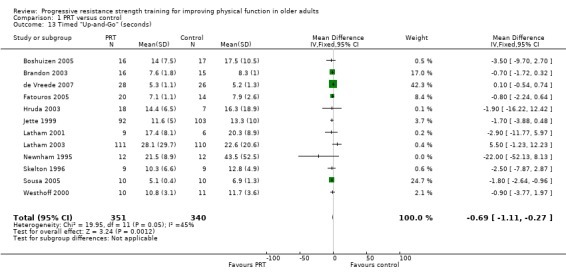

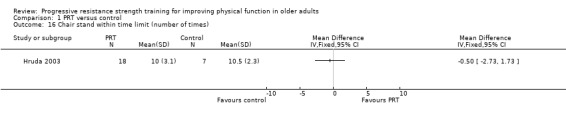

Timed up‐and‐go

Timed up‐and‐go (i.e. time to stand from a chair, walk three meters, turn, and return to sitting, measured in seconds) was analysed using a fixed‐effect model. Data, available from 12 trials and a total of 691 participants, showed the PRT group took significantly less time to complete this mobility task (Analysis 1.13: MD ‐0.69 seconds, 95% CI ‐1.11 to ‐0.27).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 13 Timed "Up‐and‐Go" (seconds).

Timed chair rise

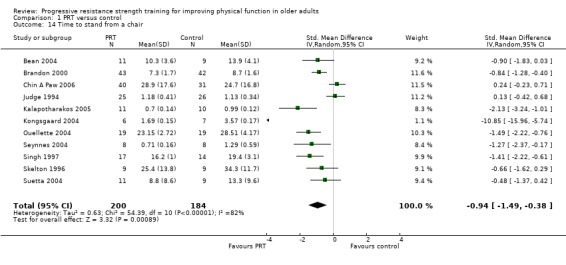

Time to stand up from a sitting position data were available in 11 studies (n = 384). Because different numbers of sit‐to‐stand were counted, SMD and a random‐effects model was used to pool these results. These showed a significant, moderate to large effect on this task in favour of the PRT group (Analysis 1.14: SMD ‐0.94, 95% CI ‐1.49 to ‐0.38).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 14 Time to stand from a chair.

Stair climbing

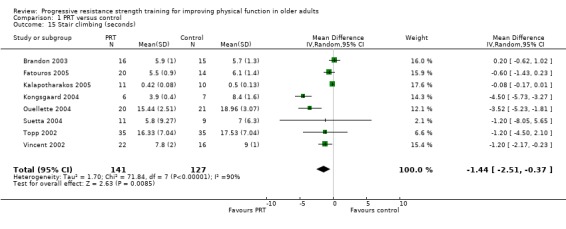

Time to climb stairs data, which were available from eight trials, also favoured PRT (Analysis 1.15). However, these results were highly heterogenous.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 15 Stair climbing (seconds).

Falls

Thirteen studies collected data about the effect of resistance training on falls or reported the incident of falls, but the outcomes reported did not allow pooling of the data. The available data is reported in Table 14. Three of these studies (Buchner 1997; Fiatarone 1994; Judge 1994) were part of the FICSIT trial, a prospective preplanned meta‐analysis to determine the effectiveness of exercise to prevent falls in older people (Province 1995). The data were extracted from the main FICSIT paper, because papers published about the individual exercise programmes did not provide useful data about the effect of resistance training alone on falls. One additional trial investigated the effect of resistance training on falls in older people while they were in hospital (Donald 2000). Another trial also assessed the effect of PRT on frail older people following discharge from hospital (Latham 2003). There is a more comprehensive review of the effect of exercise on falls in a separate Cochrane review (Gillespie 2003).

4. Falls.

| Study | Fall Statistic | PRT | Control |

| Buchner 1997 | 1) Cox regression analysis, time to first fall, 0.53, 95% CI 0.3‐0.91 for exercise group (including endurance exercise groups) | ||

| 2) proportion of people who fell in one year | all exercise groups: 42% | 60% | |

| 3) fall rate (falls/year) | all exercise: 0.81 falls/year | 0.49 falls/year | |

| Donald 2000 | 1) number of falls | 7 (n = 32) | 4 (n = 27) |

| 2) number of people who fell | 6 (n = 32) | 2 (n = 27) | |

| * Fiatarone 1994 | 1) average falls/subject | 2.32 | 2.77 |

| 2) covariance adjusted treatment incidence ratio (PRT vs control) | 0.95 (95% CI 0.64, 1.41) | ||

| Fiatarone 1997 | falls | no difference between groups (no data provided) | |

| * Judge 1994 | 1) Average falls/subject | 0.82 | 1.22 |

| 2) Co‐variate adjusted treatment incidence ratio (PRT vs control) | 0.61 (95%CI 0.34,1.09) | ||

| * Buchner 1997 | 1) Average falls/subject | 0.68 | 1.6 |

| 2) Co‐variate adjusted treatment incidence ratio (PRT vs control) | 0.91 (95%CI 0.48,1.74) | ||

| Krebs 2007 | 1 in the PRT group sustained an unrelated fall halfway through the 6‐week intervention, resulting in injury of her dominate shoulder. Exercise was modified for her. | 1 | 0 |

| Latham 2001 | total falls | 164 | 149 |

| Latham 2003 | 1) number of people who fell | 60 | 64 |

| 2) fall‐rate, person years | 1.02 | 1.07 | |

| Liu‐Ambrose 2005 | the frequency of falls (excluded falls occurred in exercise classes) | 18 (1 subject fell 7 times) | 0 |

| Mangione 2005 | Reported the number of participants fell during post‐training examination (n = 1 ‐ group was not reported) | ||

| Miszko 2003 | Report number of people | 5 | 1 |

| Singh 2005 | Numbers per person, no statistical difference between groups | .15 (.37) | 0 |

Note: Data marked with * were obtained from Province 1995

With the exception of Latham 2003, all of these trials were small (i.e. less than 80 participants in the resistance training and control groups). Only Donald 2000 found a significant reduction in falls, but there were few fall events in this trial.

Adverse events

Adverse events are reported for all trials in the review at the end of the results section.

Vitality

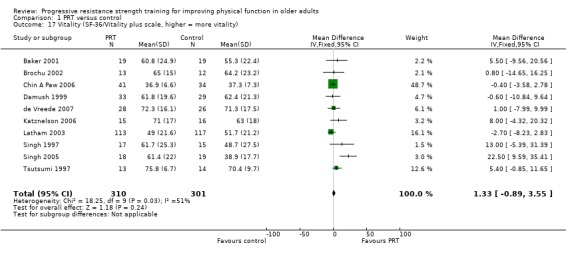

The vitality (VT) domain of the SF‐36 health status measure was assessed in 10 studies involving 611 participants. For this measure, a higher score indicates better health (i.e. more vitality): there was no evidence of an effect of PRT from the pooled data (Analysis 1.17: MD 1.33 95% CI ‐0.89 to 3.55).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 17 Vitality (SF‐36/Vitality plus scale, higher = more vitality).

Pain

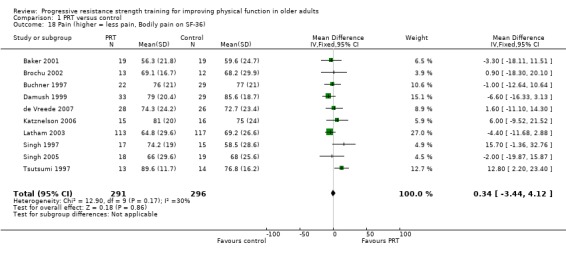

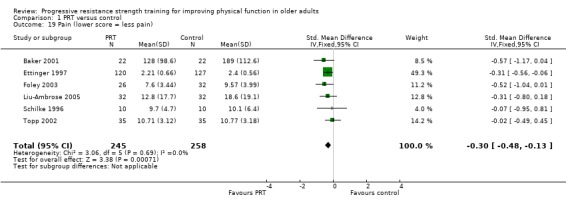

Data of bodily pain (BP) domain of the SF‐36 health status measure were provided by 10 studies involving 587 participants. For this measure, a higher score indicates better health (i.e. less pain), there was no evidence that PRT had an effect on bodily pain (Analysis 1.18 : MD 0.34, 95% CI ‐3.44 to 4.12). In contrast, six studies with 503 participants included pain measures where a higher score indicates more pain, and found evidence to support a modest reduction in pain following PRT (Analysis 1.19: SMD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐0.48 to ‐0.13). These six studies all included participants with osteoarthritis and used pain measures designed specifically for this population, which could have increased their sensitivity to change.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 18 Pain (higher = less pain, Bodily pain on SF‐36).

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 19 Pain (lower score = less pain).

Health service use, hospitalization and death

Five studies provided data about hospitalization rates, length of stay and/or outpatient visits. Donald 2000 reported that people who received PRT in addition to regular in‐hospital physiotherapy had a length of stay of 27 days compared with 32 days for the control group. Latham 2003 found that 42/120 people in the PRT group were admitted to hospital over six months compared to 35/123 in the control group. The third trial by Singh 1997 reported that, over a 10 week period, people in the PRT group had mean 2.1 (SD 0.4) visits to a health professional and mean 0.24 (SD 0.2) hospital days compared to controls mean of 2.0 (SD 0.5) visits and mean 0.53 (0.4) hospital days. The fourth study by Singh 2005 reported visits to a health professional over the study (average numbers per person): high intensity group, 2 (2); low intensity group, 2 (1.8); controls, 5 (1.8). The fifth study by Miller 2006 reported participants' discharge destinations but did not specify the group: 52 participants were discharged to a rehabilitation programme, 12 were transferred to a community hospital, 16 were discharged to higher level care, and 20 returned directly to their pre‐injury admission accommodation. An additional study, Buchner 1997, provided data about health service use, but only reported data that were pooled to include participants in aerobic training, combined aerobic training and PRT and PRT alone. This study found no change in hospital admissions between those in the exercise and control groups, but an increased number of outpatient visits by those in the control group. Finally, two studies stated that there was no difference in health care visits (Fiatarone 1997) or hospitalization (Pu 2001) but no specific data were provided.

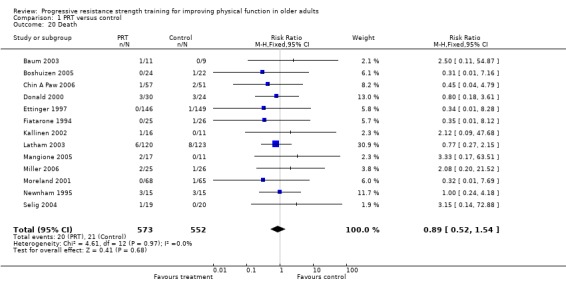

Thirteen studies provided data about participant deaths that allowed pooling (Baum 2003; Boshuizen 2005; Chin A Paw 2006; Donald 2000; Ettinger 1997; Fiatarone 1994; Kallinen 2002; Latham 2003; Mangione 2005; Miller 2006; Moreland 2001; Newnham 1995; Selig 2004). The risk ratio of death in the PRT group was not significantly different from the control group (Analysis 1.20: 20 deaths versus 21 deaths; RR = 0.89, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.54).

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PRT versus control, Outcome 20 Death.

Comparisons of PRT dosage

Thirteen trials investigated the effects of different doses of PRT. Note that data from medium intensity were not examined in the following.

High versus low intensity PRT

Physical function, pain and vitality

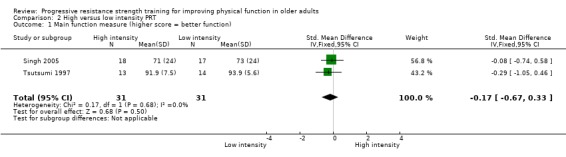

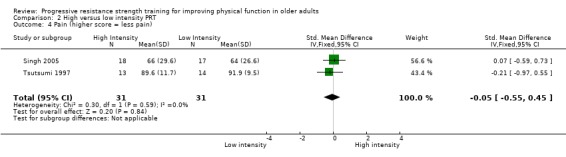

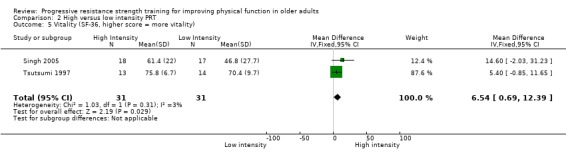

Of the 10 studies comparing high versus low intensity PRT, only two (Singh 2005; Tsutsumi 1997), evaluated physical function, pain and vitality using the domains of the SF‐36. No significant difference was found for physical function (Analysis 2.1) or pain (Analysis 2.4), but vitality scores were statistically significantly higher for high intensity (Analysis 2.5: MD = 6.54, 95% CI 0.69 to 12.39).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High versus low intensity PRT, Outcome 1 Main function measure (higher score = better function).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High versus low intensity PRT, Outcome 4 Pain (higher score = less pain).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High versus low intensity PRT, Outcome 5 Vitality (SF‐36, higher score = more vitality).

Strength

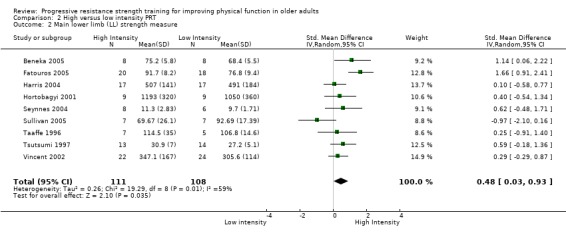

Data from all nine studies (n = 219) were available to examine the effect of high versus low intensity PRT on lower limb strength (Beneka 2005; Fatouros 2005; Harris 2004; Hortobagyi 2001;Seynnes 2004; Sullivan 2005; Taaffe 1996; Tsutsumi 1997; Vincent 2002). The results indicate that high intensity training results in greater lower limb strength, as a moderate effect was seen (Analysis 2.2: SMD = 0.48, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.93; random‐effects model).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High versus low intensity PRT, Outcome 2 Main lower limb (LL) strength measure.

Aerobic capacity

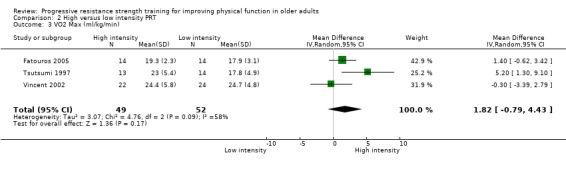

Three studies compared the effect of high versus low intensity PRT on aerobic capacity (Fatouros 2005; Tsutsumi 1997; Vincent 2002). These studies (n = 101) did not show greater benefit from high intensity compared with low intensity training (Analysis 2.3: MD 1.82 ml/kg/min, 95% CI ‐0.79 to 4.43; higher score favours high‐intensity group).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High versus low intensity PRT, Outcome 3 VO2 Max (ml/kg/min).

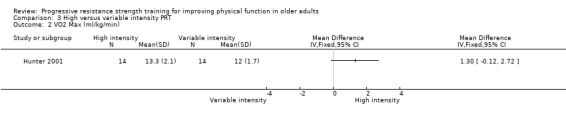

High intensity versus variable intensity PRT

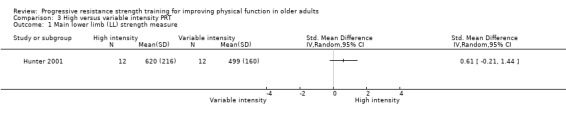

One trial (Hunter 2001) comparing high intensity PRT with variable intensity PRT showed no statistically significant differences for strength (Analysis 3.1: n = 24, MD = 0.61, 95% CI ‐0.21 to 1.44) and aerobic capacity (Analysis 3.2).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High versus variable intensity PRT, Outcome 1 Main lower limb (LL) strength measure.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High versus variable intensity PRT, Outcome 2 VO2 Max (ml/kg/min).

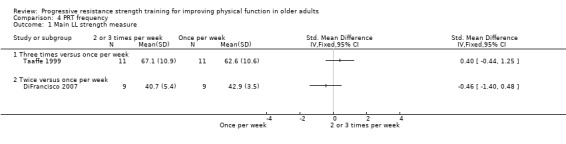

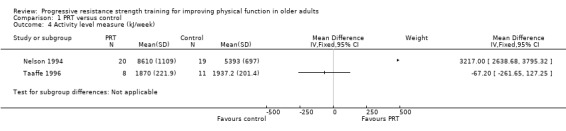

Frequency

Taaffe 1999 and DiFrancisco 2007 compared PRT at different frequencies, respectively three times a week versus once a week, and twice a week versus once a week. Both studies recruited few participants and applied high intensity intervention. There were no significant differences between the two exercise frequencies in muscle strength (Analysis 4.1: MD = 0.40, 95% CI ‐0.44 to 1.25; MD = ‐0.46, 95% CI ‐1.40 to 0.48).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 PRT frequency, Outcome 1 Main LL strength measure.

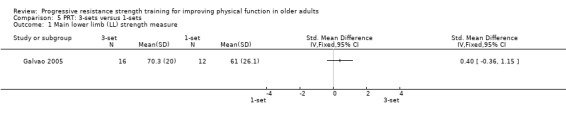

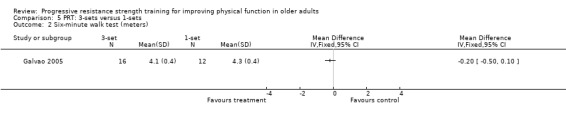

Sets

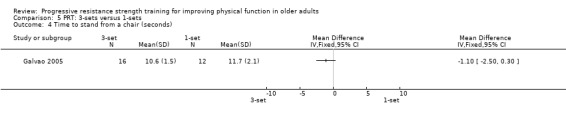

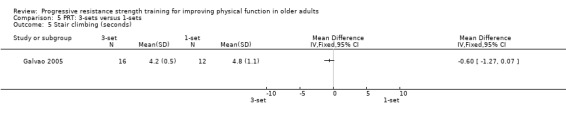

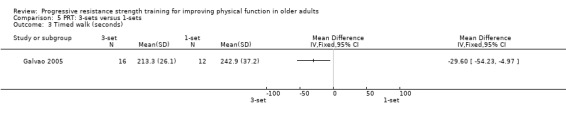

Galvao 2005 compared PRT at 3‐sets versus 1‐set in 28 participants. No significant differences between the two groups were found for muscle strength (Analysis 5.1), six minute walk test (Analysis 5.2), sit‐to‐stand (Analysis 5.4) and stair climbing (Analysis 5.5). However, participants who exercised at 3‐sets walked significantly faster than those who exercised at 1‐set (Analysis 5.3: MD = ‐29.6 seconds, 95% ‐54.23 to ‐4.97).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 PRT: 3‐sets versus 1‐sets, Outcome 1 Main lower limb (LL) strength measure.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 PRT: 3‐sets versus 1‐sets, Outcome 2 Six‐minute walk test (meters).

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 PRT: 3‐sets versus 1‐sets, Outcome 4 Time to stand from a chair (seconds).

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 PRT: 3‐sets versus 1‐sets, Outcome 5 Stair climbing (seconds).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 PRT: 3‐sets versus 1‐sets, Outcome 3 Timed walk (seconds).

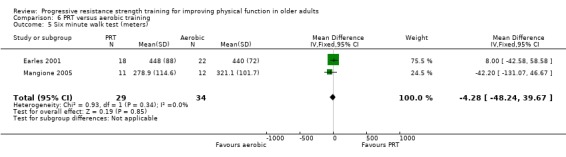

PRT versus aerobic training

Physical function

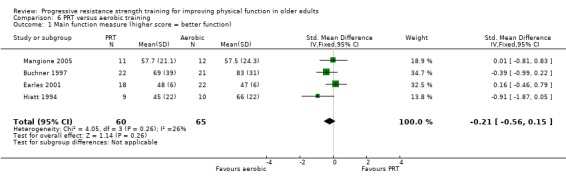

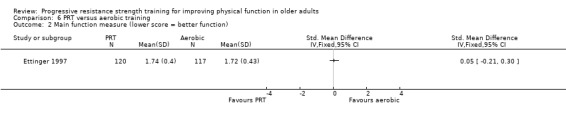

Five studies evaluated the effect of PRT compared with aerobic training on physical function. Four studies (Buchner 1997; Earles 2001; Hiatt 1994; Mangione 2005) used outcomes in which a higher score indicates less disability (n = 125), and found no significant difference (see Analysis 6.1: SMD ‐0.21, 95% CI ‐0.56 to 0.15; lower score favours the aerobic training group). The other study (Ettinger 1997) (n = 237) also found no significant difference between the groups for function (see Analysis 6.2: SMD 0.05, 95% CI ‐0.21 to 0.30; higher score favours aerobic group).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 PRT versus aerobic training, Outcome 1 Main function measure (higher score = better function).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 PRT versus aerobic training, Outcome 2 Main function measure (lower score = better function).

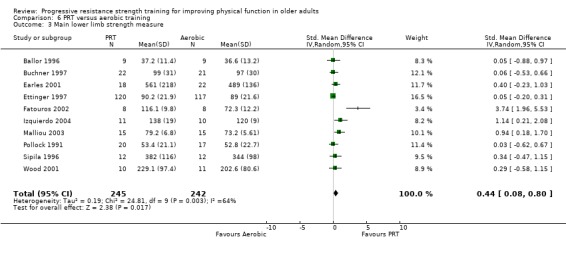

Strength

Data on lower extremity strength were available from 10 studies (n = 487) (Ballor 1996; Buchner 1997; Earles 2001; Ettinger 1997; Fatouros 2002; Izquierdo 2004; Malliou 2003; Pollock 1991; Sipila 1996; Wood 2001). These data when pooled using a random‐effects model showed that PRT had a significant benefit compared with aerobic training on strength (see Analysis 6.3: SMD 0.44, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.80; higher score favours PRT).

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 PRT versus aerobic training, Outcome 3 Main lower limb strength measure.

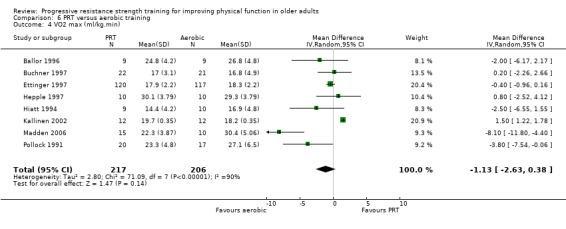

Aerobic capacity

Aerobic capacity was evaluated in eight studies involving 423 participants (Ballor 1996; Buchner 1997; Ettinger 1997; Hepple 1997; Hiatt 1994; Kallinen 2002; Madden 2006; Pollock 1991). This was measured using VO2 max in ml/kg/min. Using the random‐effects model, aerobic training had a non‐significant benefit compared to PRT for this outcome (Analysis 6.4: MD ‐1.13 ml/kg/min, 95% CI ‐2.63 to 0.38; higher values favours PRT).

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 PRT versus aerobic training, Outcome 4 VO2 max (ml/kg.min).

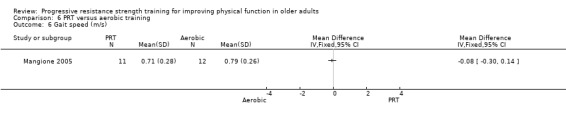

Gait speed

Mangione 2005 reported on gait speed (m/s) and found no significant difference between groups (Analysis 6.6: MD ‐0.08 m/s, 95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.14; higher speed favours PRT group)

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6 PRT versus aerobic training, Outcome 6 Gait speed (m/s).

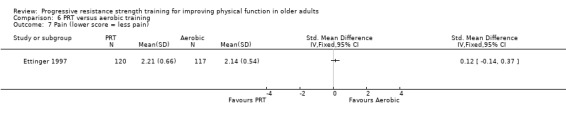

Pain

Ettinger 1997 found no significant difference between groups in pain (Analysis 6.7: MD 0.12; 95% CI ‐0.14 to 0.37; lower score favours PRT).

6.7. Analysis.

Comparison 6 PRT versus aerobic training, Outcome 7 Pain (lower score = less pain).

PRT versus balance

One study (Judge 1994) compared PRT with balance retraining (n = 55). This study found that strength improved in the PRT group, but not in the balance training group. Chair rise time and gait speed did not improve in any group, with gait speed actually declining in the balance training group. However, balance improved in the balance training group compared with the PRT group.

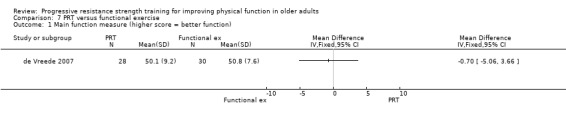

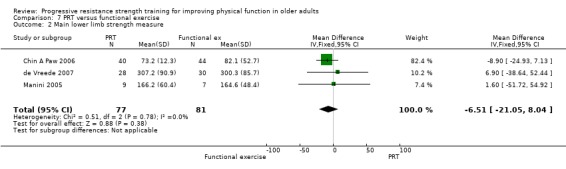

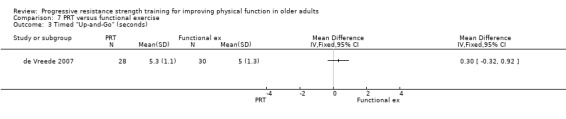

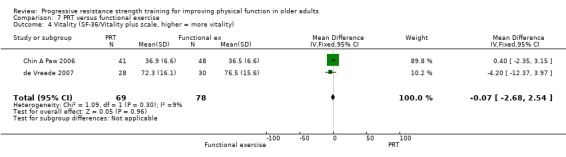

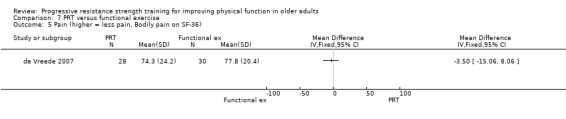

PRT versus functional training

Three studies compared PRT with functional training (Chin A Paw 2006; de Vreede 2007; Manini 2005). No significant differences between the two interventions were found for the reported outcomes (see: Analysis 7.1 physical function; Analysis 7.2 strength; Analysis 7.3 timed up and go; Analysis 7.4 vitality; Analysis 7.5 pain).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 PRT versus functional exercise, Outcome 1 Main function measure (higher score = better function).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 PRT versus functional exercise, Outcome 2 Main lower limb strength measure.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 PRT versus functional exercise, Outcome 3 Timed "Up‐and‐Go" (seconds).

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 PRT versus functional exercise, Outcome 4 Vitality (SF‐36/Vitality plus scale, higher = more vitality).

7.5. Analysis.

Comparison 7 PRT versus functional exercise, Outcome 5 Pain (higher = less pain, Bodily pain on SF‐36).

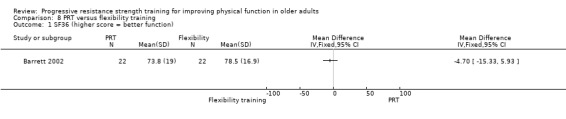

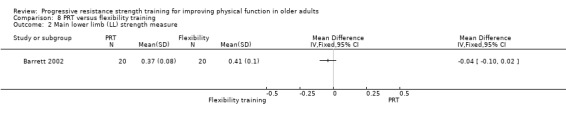

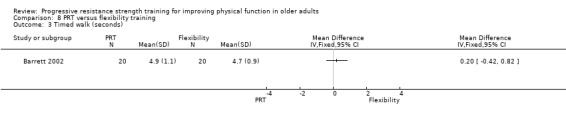

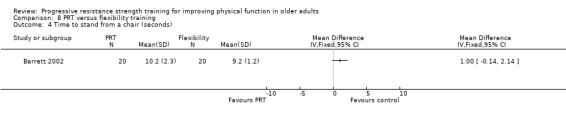

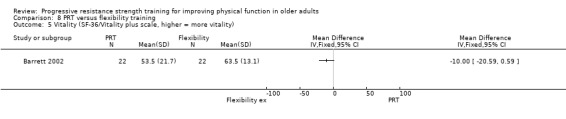

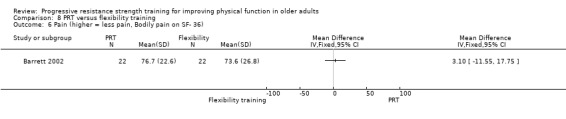

PRT versus flexibility training

Barrett 2002 (n = 40) compared a group of older adults who undertook PRT with a control group who did mainly stretching for the major muscle groups (flexibility training). No statistically significant differences were found for any of the reported outcomes (see: Analysis 8.1: SF‐36 physical function; Analysis 8.2: strength; Analysis 8.3: timed walk; Analysis 8.4: chair stand; Analysis 8.5: vitality; Analysis 8.6: pain).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 PRT versus flexibility training, Outcome 1 SF36 (higher score = better function).

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 PRT versus flexibility training, Outcome 2 Main lower limb (LL) strength measure.

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 PRT versus flexibility training, Outcome 3 Timed walk (seconds).

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 PRT versus flexibility training, Outcome 4 Time to stand from a chair (seconds).

8.5. Analysis.

Comparison 8 PRT versus flexibility training, Outcome 5 Vitality (SF‐36/Vitality plus scale, higher = more vitality).

8.6. Analysis.

Comparison 8 PRT versus flexibility training, Outcome 6 Pain (higher = less pain, Bodily pain on SF‐ 36).