Abstract

Objective

The hypothesis that the ability to construct a coherent account of personal experience is reflective, or predictive, of psychological adjustment cuts across numerous domains of psychological science. It has been argued that coherent accounts of identity are especially adaptive. We tested these hypotheses by examining relations between narrative coherence of personally significant autobiographical memories and three psychological well-being components (Purpose and Meaning; Positive Self View; Positive Relationships). We also examined the potential moderation of the relations between coherence and well-being by assessing the identity content of each narrative.

Method

We collected two autobiographical narratives of personally significant events from 103 undergraduate students and coded them for coherence and identity content. Two additional narratives about generic/recurring events were also collected and coded for coherence.

Results

We confirmed the prediction that constructing coherent autobiographical narratives is related to psychological well-being. Further, we found that this relation was moderated by the narratives’ relevance to identity and that this moderation held after controlling for narrative ability more generally (i.e. coherence of generic/recurring events).

Conclusion

These data lend strong support to the coherent narrative identity hypothesis and the prediction that unique events are a critical feature of identity construction in emerging adulthood.

Keywords: coherence, identity, well-being, autobiographical memory, narrative, emerging adulthood

In recent decades psychology has seen the substantial growth of a narrative based perspective in the development of theory and methodological tools. Narrative features prominently in theories of cognition (e.g. Bruner, 1986; 1990), cognitive development (e.g. Fivush & Nelson, 2006), social development (e.g. Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985), personality (e.g. McAdams, 1995; 1996), consciousness (e..g Damasio, 1999), self and identity (e.g. Brockmeier & Carbaugh, 2001; Gazzaniga 1998), emotion regulation (e.g. Oppenheim, Nir, Warren, & Emde, 1997), and clinical and intervention research (e.g. Pennebaker & Chung, 2011; McLeod, 1997; White & Epston, 1990).

Cutting across these domains of scientific inquiry is the fundamental assumption that how we talk about the significant events of our lives is reflective, or predictive, of our psychological adjustment. There is an assumed benefit to talking about our past in a coherent way. Prevailing integrative approaches to narrative coherence define it as telling a narrative that incorporates time and place information, presents events in an orderly fashion, provides a resolution, and incorporates subjective perspective (e.g. Baerger & McAdams, 1999; Reese, et al., 2011). It is a longstanding hypothesis that the coherence of our accounts of personally significant events is a critical feature of psychological health, especially when identity construction is a salient developmental task (i.e. adolescence and emerging adulthood).

Dating back to the earliest days of psychology, Freud (1905; 1953) famously noted in his case study of Dora: “[that] the patient’s inability to give an ordered history of their lives … is not merely characteristic of the neurosis. It also possesses great theoretical significance” (pp.16). Building on these ideas, Erikson (1950; 1968) argued that the creation of a coherent account of who we are and how we came to be that way was the critical developmental task of adolescence. McAdams (1985) went on to suggest that the coherence of what he termed “nuclear episodes”, single unique events happening in one time and place, were critical in the development of psychological functioning and well-being (see also Blagov & Singer, 2004 for discussion of a similar event type).

Failure to develop this kind of coherent account of identity across the adolescent and emerging adulthood period is thought to result in the loss of a sense of purpose and meaning in life, a feeling of helplessness, and possibly even result in the inability/failure to develop positive intimate relationships (e.g. Erikson, 1950; 1968; McAdams, 1993; 1996). With such high stakes and widespread endorsement of these ideas the body of empirical evidence directly testing these predictions is only recently emerging.

We note at the outset that our focus is on narrative coherence. There is a growing literature examining relations between multiple aspects of narrative meaning-making and well-being (see McLean, Pasupathi, & Pals, 2007; Park, 2010; Singer, 2004 for discussion of these issues). This literature focuses on expression of life lessons and/or redemptive meaning within narratives in ways that facilitate both identity growth and psychological well-being. Complimenting this literature is the idea of coherence per se, that telling a narrative in a well-structured format is itself a critical aspect of narrative identity. As reviewed by Reese et al. (2011), although narrative coherence has been operationalized in many ways, three critical dimensions emerge theoretically and empirically from this literature: chronology, context and theme. For a narrative to be coherent, it must be told in a way that clearly delineates the temporal order of actions (chronology), it must orient the event in time and place (context), and it must provide enough detail and elaboration to link component actions together in a meaningful way (theme).

Baerger and McAdams (1999) investigated relations between the narrative coherence of adults’ life stories and several aspects of psychological well-being. They found that individuals who told more coherent life stories reported lower levels of depression and higher life satisfaction. Within the clinical literature, low levels of coherence in autobiographical narratives are thought to be characteristic of psychiatric problems (e.g. Adler, 2012; Hermans, 2006; Lysaker & Lysaker, 2006). As such, there have been several investigation into relations between narrative coherence and psychiatric symptoms and psychological well-being in the context of psychotherapy. Adler, Chin, Kolisetty, and Oltmanns (2012) found the life story coherence of an adult sample was negatively associated with Borderline Personality Disorder symptoms in a clinical sample. Further, coherence predicted higher levels of relationship quality in a follow-up assessment six months later. Adler, Wagner, and McAdams (2007) asked adult patients to write narratives about their experiences in psychotherapy post-treatment. They found that the coherence of the psychotherapy narratives was positively associated with ego development, but not with a psychological well-being composite. Adler, Skalina, and McAdams (2008) similarly found that the coherence of psychotherapy narratives was related to ego development, but not to psychological well-being per se (see also Adler, Harmeling, & Walder-Biesanz, 2013).

Although the studies investigating relations between coherence of autobiographical narratives and psychological well-being discussed above represent critical advancements in our understanding of the hypothesized relations between narrative coherence, identity, and well-being they bring up several issues which we aim to address here. Specifically, studies: (1) typically assume that the collected narratives are inherently relevant to identity, but provide no independent assessment of this; (2) measure adjustment/well-being within a relatively narrow scope, with limited measures aimed to assess the two core components of well-being (hedonic and eudaimonic); and (3) typically do not attempt to control for general narrative ability.

Waters, Bauer, and Fivush (2013) have argued that there are tremendous individual differences in the extent to which “personally significant” autobiographical narratives are used to define self/identity, so an assessment of the extent to which identity is represented in the narrative itself may be critical if the major goal of the study is to assess the importance of constructing coherent narrative accounts of self and identity. Second, given the use of a relatively small set of well-being measures, the extant literature has been unable to address the claim that coherent autobiographical narratives are associated with well-being in specific theoretically predicted domains of adjustment, especially a greater sense of purpose and meaning in life, positive self view, and more intimate and satisfying social relationships in a single study. Instead, few measures are typically employed to assess different domains of well-being in any particular study and focus largely on levels of positive affect (e.g. depression or happiness) and/or clinical symptomology. However, relations between narrative coherence and ego development (a feature of eudaimonic well-being) have consistently emerged.

Although ego development is thought to be an important contributing factor to psychological adjustment (King, Scollon, Ramsey, & Williams, 2000), it typically yields small relations to other measures of psychological well-being in narrative studies (e.g. Adler et al., 2007; Adler et al., 2008). We argue that the best test of the coherent narrative identity hypothesis would include a broader swath of well-being measures aimed to assess both hedonic and eudaimonic domains, and the use of data reduction techniques in an effort to use empirically derived facets of psychological adjustment believed to be associated with the construction of a coherent narrative identity.

It is plausible that relations between narrative coherence and adjustment stem from something akin to General Intelligence or general verbal ability. As it stands, narrative research suggests that relations between coherence and verbal intelligence/ability are modest (e.g. Reese et al., 2011). However, these findings cannot rule out the possibility that association between the coherence of “nuclear episodes”, believed to be critically relevant to identity, and well-being can be explained away by a more general ability to construct coherent narratives rooted in generalized verbal ability.

Finally, we believe it important to note that the current literature examining relations between coherence, narrative identity and well-being is largely focused on adulthood. We argue that an examination of the coherent narrative identity hypothesis during the developmental period when identity construction is most salient (i.e. adolescence and emerging adulthood) is critical for our understanding of this process as it occurs across the lifespan.

Thus the major aim of this research was to build on the current literature examining the hypothesized relations between narrative coherence, identity, and psychological well-being in a sample of emerging adults. We accomplished this by (1) using a well validated and theoretically motivated measure of narrative coherence, (2) by independently assessing the manifestation of identity relevant content in each narrative, (3) by collecting a broad range of well-validated and theoretically motivated well-being measures aimed at capturing the relevant indices of psychological adjustment (i.e. hedonic and eudaimonic), and (4) measuring coherence on a set of generic/recurring event narratives for inclusion as a covariate in an effort to control for general narrative ability.

Based on the long tradition of theoretical work, and the extant empirical research, we predicted that narrative coherence would be positively correlated with psychological well-being. Further, we predicted that the interaction between narrative coherence and the extent to which the narrative discusses changes in self-understanding and/or identity development (identity content) would be positively associated with well-being, and account for additional variance. Specifically, those narratives that more fully reflect an individual’s sense of identity, and are more coherent, would be more strongly associated with measures of psychological well-being, particularly in the case of a sense of purpose and meaning.

Method

Participants

103 undergraduate students (56 females) were recruited from introductory level social science courses at a mid-sized private university, and given extra credit by their instructor for participation. 41 participants self-identified as Caucasian, 32 as Asian, 16 as African American/Black, 4 as South Asian, 2 as Hispanic, and 8 did not provide ethnicity information, or described themselves as multi-racial. Participants ages ranged from 18–28 (M = 18.87, SD = 1.41). All participants gave informed consent as approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Procedure

The data were collected as part of a larger study during the regularly scheduled meeting time of four undergraduate classes, with the instructor’s permission. Only those students who signed informed consent participated. Of the 109 students who received extra credit for attending the data collection sessions, six asked that their data not be used for research. These workbooks were destroyed following data collection.

Each class consisted of roughly 25 participants who were seated in a 60-person university lecture hall. As each participant arrived they were given a narrative workbook and instructed to write narratives about several personally significant events from their lives. For more information on the larger study please contact the authors. Participants were also asked to complete two sets of well-being questionnaires, one set to measure well-being in terms of self evaluation, and the other to measure the quality and functioning of social relationships. Participants were given 60–90 minutes to complete the workbook. The content of the booklets was counterbalanced.

Narrative elicitation and coding

Participants were asked to write four narratives about highly significant events in their lives, two defined as “nuclear episodes” or single unique events, and two generic or recurring events (order counterbalanced). Participants were encouraged to provide as much detail as possible about each:

“As you write about the event you have in mind please describe, in detail, what happened, where you were, who was involved, what you did, and what you were thinking and feeling during the event. Also, try to convey what impact this [single unique or recurring] event has had on you, and why it is an important event in your life. Try to be specific and provide as much detail as you can.”

All narratives were transcribed verbatim from the written workbooks into word documents, which were then spot checked for accuracy before coding. Narratives were coded in two ways. First, narratives were coded for coherence based on Reese et al.’s (2011) coding scheme. Second, narratives were coded for the extent to which the participant expressed features of, or insights into, their identity based on Waters et al.’s (2013) self-function coding scheme.

Narrative coherence

Narrative coherence was coded along three separate dimensions, theme, context, and chronology. Reese et al., (2011) argued that theme, context, and chronology each represent a theoretically, and developmentally, independent aspect of narrative structure, each being central to overall narrative coherence. As a result, each dimension was coded separately along a 0 to 3-point scale, 0 being the absence of the characteristics of the particular dimension of coherence, and 3 indicating that all of the characteristics of that dimension of coherence are present in the narrative. These scores were then summed to create an overall coherence score that could range from 0–9 (single events, α = .57; generic/recurring events, α = .52). Thematic coherence was defined as the extent to which a clear topic is introduced, developed, and resolved; context as the extent to which the narrative provides specific time and place information; and chronology as the level of temporal sequencing in the narrative. Reliability for each coherence scale was established between two independent coders on a subset of 60 (14.7%) narratives. Reliability analysis for each dimension of coherence produced intraclass correlations coefficients of .80 for theme, .96 for context, and .90 for chronology. Following reliability coding the remaining narratives were coded by the reliable coders independently.

Identity

Each narrative was coded on the Self Function Scale (Waters et al., 2013), a 4-point scale (Table 1) assessing the extent to which the event being narrated was relevant to one’s identity or sense of self. The coding scheme focused on content related specifically to aspects of identity including increased self-understanding, growth, and/or changes in perspectives on self, contained in the narrative (e.g. “His death changed me a lot. I became more open, understanding, started to let people in and to get to know me. I matured and carried a heavy load…This event changed me from a boy to a man”). Each narrative received a score on the self function scale, which was then summed across the two events to create an Identity Content score for each participant.

Table 1.

Identity Content coding scheme.

| 0 – | No content suggesting the memory functions to define or enhance identity |

| 1 – | Any mention of self enhancing or self deprecation due to reflection or remembering the experience, any mention of similarity or difference of self and other, any labeling of self as a member of a group, identification with an individual or group without further elaboration, identification of personal goals, or explicit mention of personal traits. |

| 2 – | Any mention of a turning point, milestone, eye opening experience, change in perspective regarding identity –OR – elaboration on the content listed in scoring criteria for a “1” |

| 3 – | Elaboration on why event/experience was a turning point, milestone, eye opening experience, or an explanation of how an experience led to a change in perspective in relation to identity –OR–elaboration of the impact of the event on identity –OR- elaboration of change in personal goals or attitudes relevant to identity. |

Reliability was established between two independent coders on a subset of 69 (17%) narratives. The intraclass correlation was .77. Following reliability the remaining narratives were divided between the two coders and coded independently.

Measures: Well-being and self

Well-being derived from a positive self image, individual accomplishments, and positive functioning, was assessed using three well validated and reliable questionnaires: 1) Satisfaction With Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larson, & Griffin, 1985); 2) Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965); and 3) Psychological Well-Being Scale (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). These scales were selected to capture well-being in both hedonic and eudaimonic domains.

Satisfaction With Life scale

Diener et al. (1985) developed this scale to assess an individuals’ satisfaction with their life as a whole. This brief questionnaire includes five Likert-type items rated on a 1 to 7 scale (e.g. “In most ways my life is close to ideal”). This scale has demonstrated good discriminant validity from other measures of well-being, and has been established as a reliable measure of well-being (Pavot & Diener, 1993; 2008).

Self-esteem

Rosenberg (1965) developed this scale to assess individuals’ positive/negative view of themselves. The questionnaire includes 10 statements that participants are asked to rate from 1 to 4, “4” being strongly disagree, and “1” being strongly agree (e.g. “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself”). This scale has well established test-retest reliability, concurrent, predictive, and construct validity (Rosenberg, 1979).

Psychological Well-Being

Ryff and Keyes (1995) developed this scale to assess six theoretically distinct well-being constructs: Autonomy, Environmental Mastery, Personal Growth, Purpose in Life, Self Acceptance, and Positive Relations. The 54 item Likert-type scale is well validated for both construct and predictive validity (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). Items include “I feel confident and positive about myself” (Self Acceptance item), “I have a sense that I have developed a lot as a person over time” (Personal Growth item).

Measures: Well-being and positive intimate relationships

Well-being derived from positive appraisal of one’s social relationships and functioning was assessed using three well validated and reliable questionnaires: 1) Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988); 2) Social Well-Being Scale (Keyes, 1998); and 3) Loyola Generativity Scale (McAdams & de St. Aubin, 1992). These measures were selected to capture well-being in a more social context/domain within two broad categories, hedonic and eudaimonic (Keyes & Magyar-Moe, 2003).

Perceived Social Support

Zimet et al. (1988) developed the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) in order to assess an individual’s appraisal of the adequacy of their social support in three domains of personal relationships; friends, family, and romantic partners. The 12-item Likert-type scale yields three subscale scores, one for each domain of personal relationships. These subscales have demonstrated good reliability, construct validity, and subscale reliability (Zimet et al., 1988; Zimet, Powell, Farley, Werkman, & Berkoff, 1990).

Social Well-Being Scale (SWB)

The 50-item Social Well-Being Scale developed by Keyes (1998) was designed to assess five theoretically proposed dimensions of social well-being based on the kinds of tasks encountered by individuals in their social networks and communities. The five subscales include: 1) Social Integration, 2) Social Contribution, 3) Social Coherence, 4) Social Acceptance, and 5) Social Actualization. These scales have been well validated and show strong convergent and discriminant validity (Keyes, 1998).

Loyola Generativity Scale (LGS)

Generativity refers to both an individual’s positive view of their relationship with their community, but also a motivation to give back to that community. The LGS assesses generativity by asking participants to rate 20 statements on a scale of 0–3 on how well statements apply to the individual (e.g. “I try to pass along the knowledge I have gained through my experiences”). This scale has shown good retest reliability, construct validity, and relations to autobiographical narratives (McAdams & de St. Aubin, 1992).

Results

Our analyses aimed to address three major questions: 1) Is the coherence of autobiographical narratives related to psychological well-being? 2) Is the relation between narrative coherence and psychological well-being moderated by the extent to which the individual uses those coherent accounts to inform identity or self-understanding? 3) Do the observed relations change when a proxy for general narrative ability is introduced as a control? To address these questions our analyses first focused on data reduction for the well-being measures included in this study using principle components analysis (PCA). To foreshadow, we obtained three components. We then examined the correlation between narrative coherence and those three well-being components. Finally, we tested for moderation effects of identity relevance, on the relations between coherence and psychological well-being.

Data Reduction

All 17 well-being scales/subscales were entered into an initial PCA with an oblique rotation (Promax), allowing the components to be correlated. Following the recommendations of MacCallum, Widaman, Zhang, and Hong (1999), and based on our sample size to variable ratio (N:p = 6.06), all scales with an initial communality less than .6 were dropped from analyses. Based on this criterion, the Family subscale from the MSPSS, and the Social Actualization and Social Coherence subscales from the SWB scale were dropped and PCA was re-run. This produced a solution of four components accounting for 74.82% of the total variance. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2(91) = 894.25, p < .001) and the KMO measure of sampling adequacy was well above threshold (KMO = .87). We, therefore, considered the data reduction analysis appropriate. Component loadings are presented in Table 2. The fourth component was dropped from analyses as it contained only one variable, and several secondary component loadings. Once components were determined, we calculated estimates of each component by summing Z-scores for each measure contained within that component (Floyd & Widaman, 1995). The Integration subscale from the SWB scale was not included in the component estimates as it was significantly cross-loaded on components 1 and 4 (Floyd & Widaman, 1995). The three component estimates used in all further analyses were found to be reliable (Component 1, α = .86; Component 2, α = .88; Component 3, α = .77).

Table 2.

Component Loadings for Well-being Measures Using PCA with Promax Rotation

| Component 1 |

Component 2 |

Component 3 |

Component 4 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosenberg Self-Esteem | .875 | |||

| Satisfaction with Life | .806 | |||

| Psychological Well-being | ||||

| Autonomy | .818 | |||

| Environmental Mastery |

.683 | |||

| Self Acceptance | .742 | |||

| Positive Relations | .406 | |||

| Purpose in Life | .658 | |||

| Personal Growth | .832 | |||

| Perceived Social Support | ||||

| Friends | .931 | |||

| Significant Other | .937 | |||

| Social Well-being | ||||

| Contribution | .935 | |||

| Acceptance | .910 | |||

| Generativity | .773 |

The Purpose in Life, Personal Growth, Contribution, and Generativity scales made up Component 1. These variables indicated a sense of purpose, a belief that they are valued by their community, and an orientation toward making contributions to their community. As a result, this component was labeled Purpose and Meaning. Self-Esteem, Satisfaction with Life, Autonomy, Environmental Mastery, and Self Acceptance were grouped under Component 2. These variables indicated a positive self evaluation and a sense that the individual is capable and in control. We labeled Component 2 as Positive Self View. Finally, Component 3 contained the scales Positive Relations, and the Social Support subscales for Friends and Significant Others. These scales all suggested that the relationships an individual has are positive, reliable, and meaningful. We labeled Component 3 Positive Relationships.

Relations Between Narrative Variables and Psychological Well-being

To test the hypothesis that narrative coherence would be related to psychological well-being we ran a series of bivariate correlations. The results are summarized in Table 3. Narrative coherence was significantly related to both Purpose and Meaning and Positive Relationships, and was marginally related to Positive Self View. The Identity Content score was not related to the well-being components.

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlations Examining Relations Between Narrative Coherence and Identity Content to Psychological Well-being Components

|

Purpose and Meaning |

Positive Self View |

Positive Relationships |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Coherence | .22* | .19† | .35*** |

| Identity Content |

.13 | −.04 | .06 |

Note: n's ranged from 99–102.

p < . 10

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

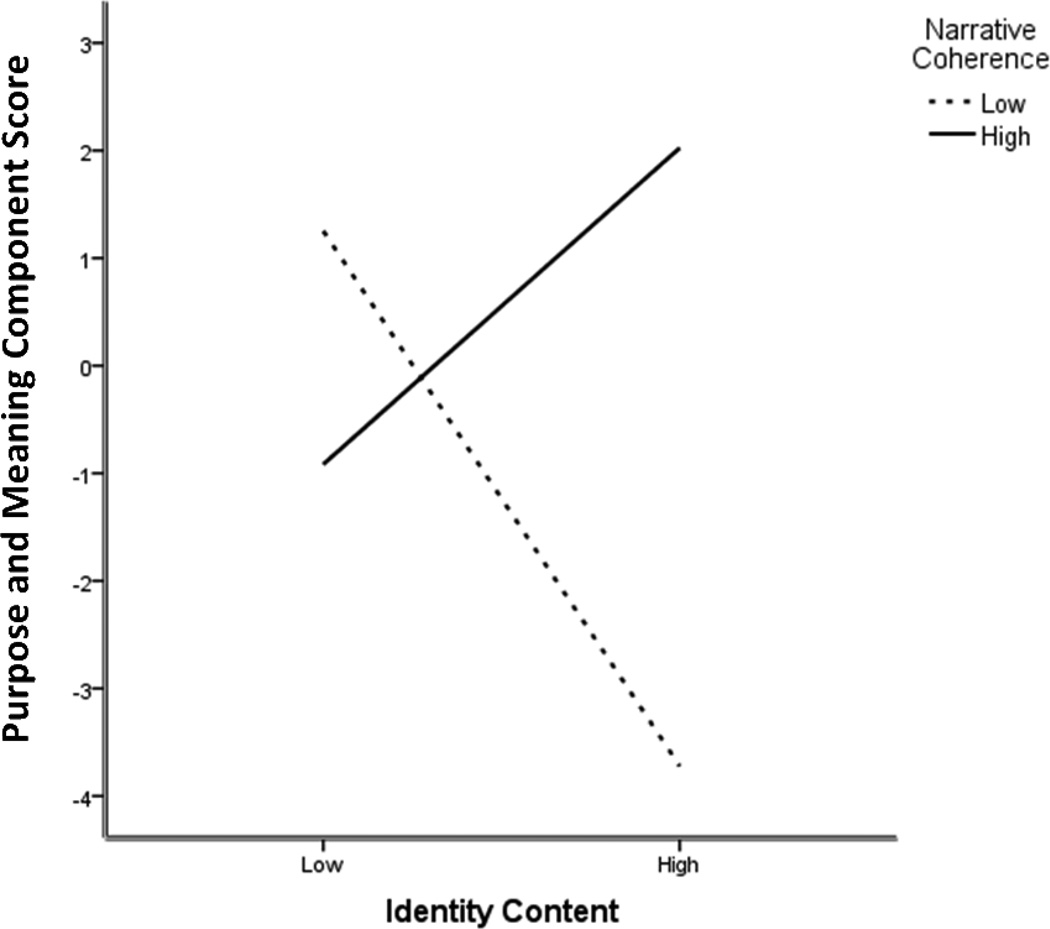

Moderation Effects

Following the correlational analyses we tested our prediction that identity content would moderate the relation between coherence and the three well-being components. Narrative coherence and Identity Content scores were all centered, then an interaction term was calculated by multiplying the two. We then examined potential moderation effects of identity on the relations between coherence and well-being using multiple regression. Results are summarized in Table 4. As predicted, the identity content significantly moderated the observed relation between narrative coherence and Purpose and Meaning. However, there was no evidence to suggest moderation for the relation between coherence and Positive Relationships or Positive Self View. To further explore the nature of the significant interaction between coherence and identity content, as it related to Purpose and Meaning, we split the coherence and identity content scores each into two groups, high and low (high = 1 SD above the mean, low = 1 SD below the mean) and plotted them in Figure 1 (see also Appendix A for narrative examples). Individuals who told coherent narratives with high levels of identity content reported the highest levels of Purpose and Meaning, while those individuals who told incoherent narratives with high levels of identity content reported the lowest levels of Purpose and Meaning.

Table 4.

Regression Analysis Examining Moderation of Coherence to Well-being Relations by Identity Content

| Purpose and Meaning (n = 96) |

Positive Self View (n = 98) |

Positive Relationships (n = 98) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | ΔR2 | β | Predictor | ΔR2 | β | Predictor | ΔR2 | β |

| Step 1 | .060† | Step 1 | .034 | Step 1 | .121** | |||

| Coherence | .206* | Coherence | .180† | Coherence | .343*** | |||

| Identity Content | .124 | Identity Content | −.053 | Identity Content | .041 | |||

| Step 2 | .060* | Step 2 | .005 | Step 2 | .000 | |||

| Coh*Identity | .248* | Coh*Identity | .074 | Coh*Identity | .011 | |||

| Total R2: 120** | Total R2: .040 | Total R2: 121** | ||||||

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

Figure 1.

Depiction of the interaction between narrative coherence and identity content in relation to the Purpose and Meaning psychological well-being component. High represents all individuals scoring 1 SD above the mean, Low represents all individuals scoring 1 SD below the mean.

Finally, we repeated the moderation analyses but with the addition of the average narrative coherence score obtained from the two generic/recurring event narratives produced by the participants. We would argue that controlling for this variable allows us to isolate the effect of coherence and identity content contained within nuclear episodes, which have been the primary focus of theoretical and empirical work on relations between narratives and well-being. Further, it allows us to assess the extent to which a more general narrative ability may contribute to associations between narrative coherence, identity content, and well-being. The results of these analyses are summarized in Table 5. The results were largely the same following the inclusion of a narrative control at step 1 of the regression analyses. Narrative coherence of the nuclear episodes significantly predicted Purpose and Meaning and Positive Social Relationships well-being components. The modest association between narrative coherence and the Positive Self View well-being component remained marginal. Further, identity content continued to moderate the relation between coherence and Purpose and Meaning. Of note, the coherence of the recurring/generic events did not predict well-being and suggests that a generally coherent narrative style does not account for the associations observed here.

Table 5.

Regression Analyses Examining Associations Between Narrative Coherence and Psychological Well-being and Moderation by Identity Content in Nuclear Episodes with Coherence Control

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| β |

β |

β |

|

| DV: Purpose and Meaning (n = 96) | |||

| Coherence Control (generic events) | −.016 | −.060 | −.109 |

| Coherence | .220* | .195† | |

| Idenitity Content | .120 | .093 | |

| Coh*Identity | .267** | ||

| ΔR2 | .000 | .064* | .067** |

| Total R2 | .000 | .064 | .131* |

| DV: Positive Self View (n = 98) | |||

| Coherence Control (generic events) | .063 | .014 | .001 |

| Coherence | .176† | .172 | |

| Idenitity Content | −.052 | −.059 | |

| Coh*Identity | .074 | ||

| ΔR2 | .004 | .030 | .005 |

| Total R2 | .004 | .034 | .040 |

| DV: Positive Social Realtionships (n = 98) | |||

| Coherence Control (generic events) | .025 | −.068 | −.071 |

| Coherence | .361*** | .359*** | |

| Idenitity Content | .037 | .035 | |

| Coh*Identity | −.016 | ||

| ΔR2 | .001 | .124** | .000 |

| Total R2 | .001 | .125** | .125* |

Note.

Note. p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

DV = Dependent Variable in regression model; Coherence Control = Mean centered coherence score of the two generic/recurring event narratives.

Discussion

Our results replicate and extend previous literature linking narrative coherence and psychological well-being. We found that the ability to produce coherent autobiographical narratives in emerging adulthood was modestly related to psychological well-being in terms of Positive Self View, and, importantly, extended these findings to include Purpose and Meaning, and Positive Social Relationships. Our results provide critical empirical support for the coherent narrative identity hypothesis (e.g. Erikson, 1950; 1968; McAdams, 1993) during an important developmental time period for identity construction. Most intriguing, we demonstrated that the ability to tell coherent autobiographical narratives that explicitly address identity is linked to a higher sense of Purpose and Meaning. We did not find support for moderation in the case of Positive Self View or Positive Social Relations. Overall, these data suggested that it is not only important how things are narrated but also the interaction with what is narrated (i.e. coherence with respect to our autobiographical accounts of identity; see McAdams, 2006 for similar theoretical arguments). It is also important to note that the relations between coherence and psychological well-being were, as argued by McAdams and colleagues (e.g. Blagov & Singer, 2004; McAdams, 1985; 1993), specific to narratives of nuclear episodes and was not seen for generic/recurring type events.

Although we are unable to directly address the direction of effects (narrative to well-being v. well-being to narrative) with these data there is some research to suggest a causal role for autobiographical narratives. We point to the expressive writing and clinical literatures which have found that changes in narrative do precede changes in well-being, which supports the argument that narratives play a causal role in psychological well-being (Adler, 2012; see Pennebaker & Chung 2011, for a review of expressive writing). This suggests that the direction of effects is from narrative to well-being, not from well-being to narrative. Given the theoretical importance of the direction of this effect, future research should employ longitudinal or intervention designs to more fully examine this question.

Moving beyond coherence alone, our results suggested that a significant amount of variance can be accounted for by examining the interaction between content (i.e. identity) and quality (i.e. coherence), even above and beyond what each construct accounts for independently. Analytic approaches to autobiographical narrative have largely focused on one construct domain over the other. We would argue that favoring either the content or quality may result in leaving explainable variance on the table. Interestingly, the interaction observed between coherence and identity content suggested that not only is it beneficial to tell coherent narratives about identity, but that it can be detrimental to tell incoherent narratives focused on identity (Figure 1). This fits well with Eriksonian predictions that adolescents and emerging adults who resolve identity issues in a coherent manner develop a sense of purpose while those who do not experience identity confusion and psychological distress. It is also interesting, and perhaps surprising, that identity content did not predict psychological well-being in its own right. This further supports the idea that creating a coherent explanatory narrative framework around issues of self and identity is a crucial aspect of healthy adjustment.

As for the specific mechanism that may underlie the observed relations/interaction between narrative coherence, identity content, and well-being, there are several potential accounts. One account, stemming from the clinical and developmental literatures, argues that narrative coherence itself is not causal in terms of psychological adjustment. Instead, it is argued that a breakdown in coherence is reflective of an inability to regulate the emotions associated with the event being recalled (e.g. Main, 2000). According to these accounts, narrative incoherence is an indirect indicator of ineffective coping, and this inability to cope with experiences that challenge our understanding of self accounts for the relation between coherence, identity, and adjustment.

Alternatively, the researchers from cognitive psychology argued for a more causal role for narrative coherence (see Medved and Brockmeier, 2010 for a review). They argue that the creation of a causal and explanatory framework in which to understand ourselves and our experiences results in that experience no longer infringing on cognitive and regulatory resources. The act of telling a coherent narrative, complete with a resolution, results in the event essentially becoming understood and integrated into existing knowledge which frees up cognitive and regulatory resources and reduces rumination (Schank, 1995). The telling of a coherent narrative stops the telling of other versions of that narrative and allows the mind to move forward. Further research is required to differentiate between these accounts of the role of narrative coherence in psychological adjustment.

The methodology employed by this study may be useful to future research in several ways. Currently, studies examining relations between narrative coherence and psychological well-being do so using methodologies/coding which may only be appropriate for adults. For example, the life story approach requires participants to produce a narrative history of their entire lives, something quite difficult up until early adulthood (Habermas & Bluck, 2000; McAdams, 1985; Singer, 2004). Our approach, however, is amenable to samples across development as the coherence measure employed here was developed and validated using developmental samples starting in childhood and moving into late adolescence and adulthood (Reese et al., 2011). This provides the opportunity to track the relation between coherence and well-being longitudinally beginning early in development. As well, researchers and clinicians may benefit from examining both coherence and identity content in autobiographical memories/narratives, as we have found a significant moderation effect (see Boals, Steward, & Schuettler, 2010, for further discussion of this issue).

Our methods further point to the theoretical and empirical importance of broadening operationalizations of well-being. We found that relations between narrative coherence and psychological well-being cannot be assumed to cut across all domains of well-being. The same can be said of the interaction observed here between coherence and identity content. Theory and research on psychological well-being continue to emphasize the importance of hedonic well-being (i.e. high levels of positive affectand/or low levels of psychiatric symptomology) in healthy functioning, but also point to the positive aspects of creating purpose and meaning and building satisfying social relationships referred to as eudaimonic well-being (e.g. Keyes & Magyar-Moe, 2003; Ryff & Keyes, 1995). Future research would benefit from including broader assessments of well-being in an effort to better understand what ways narrative coherence may or may not be beneficial.

In terms of narrative coding, we believe the measure used to assess identity content (Self Function Scale; SFS) presented here represents an important contribution to the available coding schemes employed by narrative researchers interested in self and identity. The SFS is unique from other more prevalent narrative coding schemes (e.g. Autobiographical Reasoning – Habermas & Bluck, 2000; Habermas & Köber, 2014; Self-Event Connections – Banks & Salmon, 2013) that have been used to study relations between autobiographical narratives and identity or well-being in several ways. The SFS takes the perspective that a narrative is a representational structure and targets aspects of the narrative that reflect an individual’s representation of self or identity (from simple traits and group memberships to highly elaborated and nuanced accounts of identity). Autobiographical reasoning, in contrast, can be thought of as a more domain general cognitive ability, one that supports the kinds of content coded for with the SFS but also other kinds of narrative content (e.g. using autobiographical memories to reason about relationships or the world). Other measures such as the Self-Event Connections coding scheme captures the prevalence of links between an autobiographical memory and self, but does not distinguish between levels of sophistication of those connections, which the SFS does. Although we believe these measures to be unique and each representing a meaningful level of narrative analysis, factor analytic work is necessary to determine how distinct the coding schemes discussed here (as well as others) actually are (see Waters, Shallcross, & Fivush, 2013 for discussion of these issues).

Acknowledgments

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number F32HD078250. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors would like to thank Lawrence Barsalou, Patricia Bauer, Scott Lilienfeld, Joseph Manns, and Corey Keyes for their thoughtful comments during the conceptualization of this project. We would also like to thank John Shallcross, Chanie Howard, Yaa Cheremateng, and Lauren Albers for their assistance with data collection, transcription, and coding.

Appendix A

High Coherence and High Identity

“The most memorable event I would talk about as an international student is coming to the United Stated for study abroad. I was only 16 years old when I was separated from my parents at the airport and attended a high school where I was confronted with different language, culture, and ethnic groups. I experienced a sort of cultural shock that I was afraid to approach anyone and even participate in class. There was one friend who saved me [from] this circumstance [and] taught me how to study, participate, make friends, and even [slang]. With this support, I was able to adjust myself to a new environment quickly and eventually I found myself speaking a new language fluently. This event made me a person who would not get afraid of trying new things and finding the best outcomes from it.”

“When I was in 6th grade, my grandfather on my mom’s side was diagnosed with liver cancer. When he was diagnosed, the cancer cells had already taken up his entire liver and many of other organs as well. The doctor told us that my grandfather would live about one year at best. Everyone in the family was greatly despaired at first, but as the time went on, we all tried to be the best sons/daughters /grandsons/grandaughters we could be and make his last days as peaceful and comfortable as possible. After being diagnosed with cancer, my grandfather, a vehement former Buddhist, accepted Christ and converted to Christianity. And he daily devoted himself to reading the Bible and praying and deepening his relationship with God. Witnessing his conversion, many of my family members and I realized the reality of God and His power in our lives. My grandfather spent many months in devotion to God while receiving chemotherapy and other medications. Months of chemotherapy finally wore him out eventually, and he came to the point where he could not get out of his bed. His once healthy body was left with nothing but bones and skin. His face was dark and bony. One day, in his bed, he called me over to his bed side. He had no energy to call me audibly, so he had to use his weakened and bony arm to call me to his side. Seeing his withered arm calling me to his bed, I was engrossed with fear. I felt like he was gonna breathe his last breath and leave me forever. Being so filled with terror, I ignored his calling and left the room. And that was the last moment I got to spend with him. This last memory of my grandfather has a significant meaning to me because it taught me what a wicked and sinful person I am that I ignored my ill grandfather merely because of my fear. Even till this day, it is the biggest regret of my life.”

Low Coherence and High Identity

“This may be shallow, but getting my driver’s license has to be a single event that is important to me. I regard my license as a physical symbol of my coming of age, because driving safely is a thing that requires great responsibility and maturity. It is also a symbol of freedom, as I was lucky enough to have my own car. Before, where I had to ask my parents to drive me, walk or take the bus (or other means of transportation), now I could go out any time that I felt like it. Driving is almost an escape mechanism for me, because I feel free and unbound.”

“One of the experiences that I had that had huge influence on me was my parents’ divorce. When I first heard about it, I was shocked and didn’t know what to do. I often saw my parents arguing and I would be the one who always [tried] to make things ok and settle things down between them. This event made me think deeper even though I was like 6th or 7th grader, and I would say I was bit more mature than other kids that were around my age. Also, I was an outgoing and confident kid that didn’t fear that much, however this event made me change into [a] more shy and quiet guy. But now I try to be more friendly and outgoing to other people because that’s what people did to me when I was in big depression and going through the hard times.”

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Adler JM. Living into the story: Agency and coherence in a longitudinal study of narrative identity development and mental health over the course of psychotherapy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102(2):367–389. doi: 10.1037/a0025289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler JM, Chin ED, Kolisetty AP, Oltmanns TF. The distinguishing characteristics of narrative identity in adults with features of Borderline Personality Disorder: An empirical investigation. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2012;26:498–512. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2012.26.4.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler JM, Harmeling LH, Walder-Biesanz I. Narrative meaning-making is associated with sudden gains in clients' mental health under routine clinical conditions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(5):839–845. doi: 10.1037/a0033774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler JM, Skalina LM, McAdams DP. The narrative reconstruction of psychotherapy and psychological health. Psychotherapy Research. 2008;18(6):719–734. doi: 10.1080/10503300802326020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler JM, Wagner JW, McAdams DP. Personality and the coherence of psychotherapy narratives. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41(6):1179–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Baerger DR, McAdams DP. Life story coehrence and its relations to psychological well-being. Narrative Inquiry. 1999;9(1):69–96. [Google Scholar]

- Banks MV, Salmon K. Reasoning about the self in positive and negative ways: Relationship to psychological functioning in young adulthood. Memory. 2013;21(1):10–26. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2012.707213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boals A, Steward JM, Schuettler D. Advancing our understanding of posttraumatic growth by considering event centrality. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2010;15:518–533. [Google Scholar]

- Brockmeier J, Carbaugh D. Narrative and indentity: The conference and charge. In: Brockmeier J, Carabaugh D, editors. Narrative and identity: Studies in autobiography, self, and culture. Philadelphia: John Benjamins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner J. Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner J. Acts of meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio A. The Feeling of What Happens: Body, Emotion and the Making of Consciousness. New York: Harcourt Brace; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Childhood and society. New York: Norton; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Nelson K. Parent-child reminiscing locates the self in the past. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2006;24:235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Widaman KF. Factor analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:286–299. [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. In: Strachey J, translator. Fragment of an analysis of a case of hysteria. 1901–1905. VII. London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psychoanalysis; 1905/1953. pp. 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaniga MS. The Mind’s Past. University of California Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas T, Bluck S. Getting a life: The emergence of the life story in adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:748–769. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habermas T, Köber C. In: Autobiographical reasoning is constitutive for narrative identity: The role of the life story for personal continuity. McLean KC, Syed M, editors. The Oxford handbook of identity development Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans HJM. The self as a theater of voices: Disorganization and reorganization of a position repertoire. Journal of Constructivist Psychology. 2006;19(2):147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM. Social well-being. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1998;61:121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM, Magyar-Moe JL. The measurement and utility of adult subjective well-being. In: Lopez SJ, Snyder CR, editors. Positive psychological assessment: A handbook of models and measures. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 411–425. [Google Scholar]

- Lilgendahl JP, McAdams DP. Constructing stories of self-growth: How individual differences in patterns of autobiographical reasoning relate to well-being in midlife. Journal of personality. 2011;79(2):391–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Lysaker JT. A typology of narrative impoverishment in schizophrenia: Implications for understanding the processes of establishing and sustaining dialogue in individual psychotherapy. Counseling Psychology Quarterly. 2006;19:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Widaman KF, Zhang S, Hong S. Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:84–99. [Google Scholar]

- Main M. The organized categories of infant, child, and adult attachment: Flexible vs. inflexible attention under attachment-related stress. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association. 2000;48(4):1055–1096. doi: 10.1177/00030651000480041801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monographs of the society for research in child development. 1985:66–104. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP. Power, intimacy, and the life story: Personological inquiries into identity. New York: Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP. The stories we live by. New York: Harper Collins; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP. What do we know when we know a person? Journal of Personality. 1995;63(3):365–396. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP. Personality, modernity, and the storied self: A contemporary framework for studying persons. Psychological Inquiry. 1996;7:295–321. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP, de St Aubin E. A theory of generativity and its assessment through self-report, behavioral acts, and narrative themes in autobiography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:1003–1015. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP, Reynolds J, Lewis M, Patten AH, Bowman PJ. When bad things turn good and good things turn bad: Sequences of redemption and contamination in life narrative and their relation to psychosocial adaptation in midlife adults and in students. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27(4):474–485. [Google Scholar]

- McLean KC, Pasupathi M, Pals JL. Selves creating stories creating selves: A process model of narrative self development in adolescence and adulthood. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2007;11:262–278. doi: 10.1177/1088868307301034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod J. Narrative and psychotherapy. London: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Medved M, Brockmeier J. Weird stories. In: Hyvärinen M, Hyden LC, Saarenheimo M, Tamboukou M, editors. Beyond narrative coherence. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins; 2010. pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim D, Nir A, Warren S, Emde RN. Emotion regulation in mother-child narrative co-construction: Associations with children’s narratives and adaptation. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:284–294. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. Making sense of the meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological bulletin. 2010;136(2):257. doi: 10.1037/a0018301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavot W, Diener E. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:164–172. [Google Scholar]

- Pavot W, Diener E. The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. Journal of Positive Psychology. 2008;3:137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Chung CK. Expressive writing and its links to mental and physical health. In: Friedman HS, editor. Oxford handbook of health psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 417–437. [Google Scholar]

- Reese E, Haden CH, Baker-Ward L, Bauer PJ, Fivush R, Ornstein PA. Coherence in personal narratives: A multidimensional model. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2011;12(4):1–38. doi: 10.1080/15248372.2011.587854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricoeur P. Time and narrative. Vol. 1. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, translated by Kathleen McGlaughlin and David Pellaver; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Keyes CLM. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:719–727. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schank RC. Tell me a story: Narrative and intelligence. Northwestern Univ Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JA. Narrative identity and meaning making across the lifespan: An introduction. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:437–459. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters TEA, Bauer PJ, Fivush R. Autobiographical memory functions for single, recurring, and extended events. Journal of Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2014;28:185–195. [Google Scholar]

- Waters TEA, Shallcross JF, Fivush R. The many facets of meaning making: Comparing multiple measures of meaning making and their relations to psychological distress. Memory. 2013;21:11–124. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2012.705300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White M, Epston D. Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York: Norton; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52:30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1990;55:610–617. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]