Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To describe the roles of family members in older men’s depression treatment from the perspectives of older men and primary care physicians (PCPs).

METHODS

Cross-sectional, descriptive qualitative study conducted from 2008–2011 in primary care clinics in an academic medical center and a safety-net county teaching hospital in California’s Central Valley. Participants in this study were 1) 77 age ≥ 60, non-institutionalized men with a one-year history of clinical depression and/or depression treatment who were identified through screening in primary care clinics and 2) a convenience sample of 15 PCPs from same recruitment sites. Semi-structured, in-depth qualitative interviews were conducted and audiotaped, then transcribed and analyzed thematically.

RESULTS

Treatment-promoting roles of family included providing an emotionally supportive home environment, promoting depression self-management and facilitating communication about depression during primary care visits. Treatment impeding roles of family included triggering or worsening men’s depression, hindering depression care during primary care visits, discouraging depression treatment and being unavailable to assist men with their depression care. Overall, more than 90% of the men and the PCPs described one or more treatment-promoting roles of family and over 75% of men and PCPs described one or more treatment-impeding roles of family.

CONCLUSIONS

Families play important roles in older men’s depression treatment with the potential to promote as well as impede care. Interventions and services need to carefully assess the ongoing roles and attitudes of family members and to tailor treatment approaches to build on the positive aspects and mitigate the negative aspects of family support.

Keywords: depression, primary care, men, family, qualitative

INTRODUCTION

Despite the public health and policy importance of family in the care of persons with depression and other chronic illnesses, family engagement in the delivery of primary healthcare for depression has received remarkably little attention (Wolff, 2012). This knowledge gap is particularly striking given that family members are considered to be important partners in patient-centered care (Bodenheimer et al., 2002, Epstein et al., 2010) and the primary care medical home model (Rittenhouse and Shortell, 2009, Stange et al., 2010). Failure to consider the role of family (both positive and negative) in depression treatment may lead to contextual errors (i.e. failure to consider clinically-relevant aspects of the patient’s psychosocial and environmental context) in medicine (Schwartz et al., 2010, Weiner et al., 2010).

Understanding the role(s) of family may be particularly important for older adults, many of whom are accompanied by family members during primary care visits or rely on family members for health-related assistance in the home (Wolff and Roter, 2011, Sayers et al., 2006), and for older men, who may be more reticent to disclose depressive symptoms (Hinton et al., 2006, Apesoa-Varano et al., 2010). Depression is a common, disabling and often chronic condition for which we have effective treatments (Park and Unutzer, 2011). Men are at increased risk for depression under-treatment, possibly contributing to higher male rates of suicide (Hinton et al., 2006, Crystal et al., 2003, Moller-Leimkuhler, 2002). Several factors may underpin depression under-treatment in older men, including masculinity and gender norms (Addis and Mahalik, 2003). Because men prefer family involvement in their depression treatment (Dwight-Johnson et al., 2013), family engagement is a promising strategy to reduce this gender disparity. Identifying the role(s) of family in depression treatment may also help clinicians more effectively mobilize family to improve older men’s depression care. While relatively few studies have focused on clinician perspectives on treatment of late life depression, two prior studies have highlighted physician views of the important role of family in strengthening care (Apesoa-Varano et al., 2010; Hinton et al., 2006).

To begin to describe the role(s) of family involvement in older men’s depression care, we examined data collected during a qualitative study that elicited the perspectives of both depressed older men and their primary care physicians (PCPs). To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore systematically the multiple roles of family in a primary-care based sample of depressed older men.

METHODS

This study was part of a larger mixed-method, cross-sectional study (Men’s Health and Aging Study). Participants were recruited from primary care outpatient clinics in California’s Central Valley, including four clinics in a large academic medical center and its affiliated primary care network and two clinics in a safety-net, teaching county hospital (Hinton et al., 2012). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both participating institutions.

The authors are an interdisciplinary team that includes two geriatric and one general psychiatrist, social scientists (medical sociologist and medical anthropologist) and a nurse. This study was part of a larger NIMH funded research project that sought to understand broadly the role of sociocultural and gender factors as they influence pathways to depression treatment for older men from the perspectives of both older men and primary care physicians. The theme of family emerged early and prominently in the analysis process, leading us to examine this theme in more depth in this paper.

Recruitment of older men and primary care physicians

To generate a sample as representative as possible of depressed older men (treated and untreated) in this predominantly rural area, a two-step depression screening process was used to identify older men with a one-year history of clinical depression and/or depression treatment (Hinton et al., 2012). Additional study inclusion criteria were 1) age 60 years or older, 2) Mexican origin or U.S. born non-Hispanic whites, 3) non-psychotic, 4) non-demented, and 5) non-institutionalized. First, men were approached at their scheduled primary care visit and asked to complete a brief socio-demographic form, a modified version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-revised (PHQ-2) (Kroenke et al., 2003, Unutzer et al., 2001) and a question on past-year depression care use (i.e., “In the past 12 months, have you had any treatment such as medications or counseling for stress, depression, or problems with sleep, appetite, or energy?) (Unutzer et al., 2001).

Men who screened positive were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (i.e. SCID) major depression module assessing the occurrence of an episode of major depression during the past month and the past year (First et al., 2002) as well as additional questions for chronic depression. Chronic depression was assessed based on endorsement of three or more SCID items and including at least one of two core symptoms of major depression (i.e. anhedonia or depressed mood) on most days over the past two years. From the same clinics that were used to recruit older men, we recruited a convenience sample of primary care physicians (PCPs) through email, flyers posted in the participating clinics and presentations at staff meetings. Information is not available to compare the characteristics of PCPs who were aware of the study (through the flyer or by email) but chose not to participate with those who did participate. Men and PCPs were each compensated $100 for completing the qualitative interview.

Interviews with older men and primary care physicians

In-depth qualitative interviews were conducted with older men (in their homes or in the clinic) and primary care physicians (in the clinic) by highly trained (PhD or MD). All but 5 of the interviews with older men and all of the PCP interviews were conducted by a female interviewer who was bilingual (CAV) and the remaining interviews were conducted by a male interviewer (LH). The interview guide for older men covered the following domains: conceptions of masculinity, depression explanatory model, family and social responses to illness, suicide, and help-seeking in primary care and general help-seeking. Interviews with PCPs covered formal training and experience, general approaches to diagnosis and treatment of depression (including the role of family), perceptions of gender and ethnic differences in depression, and strategies to improve the diagnosis of depression. It should be noted that while the interview guides for PCPs and older men differed in a number of respects, both included an open-ended query about family responses to men’s depression. Consistent with standard approaches to in-depth interviews, the interviewer had considerable latitude in conducting the interview, including the order in which interview domains were explored and the flexibility to ask follow-up clarifying questions (Britten 1995). Interviews with men ranged from 1.5 to 2.5 hours and were conducted in Spanish or English per participant preference. Interviews with primary care providers lasted 1–2 hours and all were conducted in English. All interviews were audio taped, transcribed verbatim by bilingual research staff and de-identified. Spanish language interviews were also translated into English. CAV reviewed translations for accuracy and quality.

Data analysis

Computer-assisted data analysis (i.e. data management and coding) was conducted using NVIVO® 7.0 (QSR International) and involved multiple steps that included open-coding and constant comparison, following an accepted approach for descriptive qualitative studies (Chenail, 2011, Sandelowski, 2000, Merriam, 2009). First, three researchers systematically read and coded the 77 interviews conducted with older men for major topics: psychosocial and emotional distress, family, suicide, coping and self-management, formal help-seeking, masculinity, and substance use/abuse. These topics were both anticipated, based on the design and content of the interview guide, and emergent, based on reading the commentaries and discussion of whole transcripts by the research team. Family roles in older men’s depression care was one of the emergent themes. A similar process was used to code the 15 primary care physician interviews for the following topics: background, approach to diagnosis of depression, ethnic and differences in depression, family involvement in depression care, approach to treatment of depression, gender differences in depression, improving depression care, and suicide.

Next, interview material coded as “family” (for depressed older men) and “family involvement in depression care” (PCPs) was further reviewed and open-coded by three members of team (LH, CAV, MP) to identify and refine emergent themes related to the role of family members in depression treatment. The coding included men’s and PCP’s statements about their own experiences and attitudes related to family involvement. Through a consensus process, a final list of themes was identified which the lead author (LH) consolidated into a codebook with theme definitions. The coded family material was then reviewed independently by two additional trained coders and discrepancies resolved through a consensus process. Consistent with the goals of the study, coding reached a point at which new categories related to family involvement in older men’s depression care were not appearing in the data.

Participant selection and characteristics

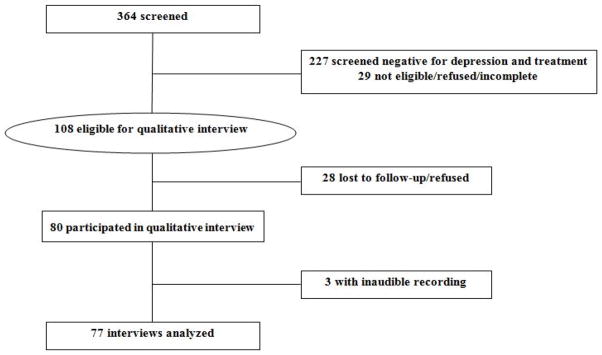

Screening process results are summarized in Figure 1 and are summarized elsewhere (Hinton et al, 2012). Of 108 qualified men, 80 agreed to qualitative interviews. Three interviews were lost to technical issues, leaving 77 interviews for analysis. Compared to the 28 men who qualified but did not complete the qualitative interview, the 80 men who completed the qualitative interviews were more likely (p>.05) to be white non-Hispanic and not to report past year depression treatment (p<.10) and but not differ significantly (p>.10) in terms of the other characteristics. Among the 18 PCPs interviewed, fifteen transcripts were complete and useable (3 were excluded due to technical difficulties). Characteristics of the older men and PCPs are shown in Tables 1 and 2 respectively.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of recruitment of older men with one year depression and/or deprssion treatment

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of older men

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 77 (100) |

| Female | 0 (0) |

| Age | |

| 60–64 | 39 (51) |

| >64 | 38 (49) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 47 (61) |

| Mexican origin | 30 (39) |

| Education | |

| None | 3 (4) |

| Grades 1–6 | 11 (14) |

| Grades 7–11 | 15 (20) |

| Grade 12 or GED | 21 (27) |

| College 1–3 years | 15 (20) |

| College 4 years or more | 8 (10) |

| Graduate Degree | 4 (5) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 46 (60) |

| Divorced, separated, widowed, cohabitating | 31 (40) |

| Self-reported health | |

| Good to excellent | 27 (35) |

| Fair | 30 (39) |

| Poor | 20 (26) |

| Language of interview | |

| English | 60 (78) |

| Spanish | 17 (22) |

| Clinical depression | |

| Past year clinical depression | 60 (78) |

| No past year clinical depression | 17 (22) |

| Clinical depression treatment | |

| Past year depression treatment | 46 (60) |

| No past year depression treatment | 31 (40) |

| Recruitment Site | |

| Academic medical center clinics | 33 (43) |

| County hospital clinics | 44 (57) |

| Income | |

| <$10,000 | 22 (28) |

| $10,000–$25,000 | 29 (38) |

| $26,000–$50,000 | 13 (17) |

| $51,000–$75,000 | 3 (4) |

| $76,000 – $100,000 | 6 (8) |

| >$100,000 | 3 (4) |

| No answer | 1 (1) |

| Employment | |

| Retired | 63 (82) |

| Unemployed but seeking work | 3 (4) |

| Employed part/full-time | 11 (14) |

Age range: 60 to 80 years; median: 64 years.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of primary care physicians

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 9 (60) |

| Female | 6 (40) |

| Age-group* | |

| 24–34 | 7 (47) |

| 35–44 | 5 (33) |

| >44 | 3 (20) |

| Employment | |

| Full-time | 15 (100) |

| Part-time | 0 (0) |

| Type of clinic | |

| Academic medical center and affiliated primary care network | 3 (20) |

| County hospital clinics | 12 (80) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 4 (27) |

| Hispanic | 1 (7) |

| Asian | 10 (66) |

| East Asian (Chinese) | 1 |

| Southeast Asian (Vietnamese, Burmese) | 2 |

| South Asian (Indian) | 6 |

| Asian, Unspecified | 1 |

| Specialty | |

| Family medicine | 14 (93) |

| Geriatrics | 1 (7) |

| Current Position | |

| Clinical faculty | 11 (73) |

| Resident | 4 (27) |

Age range: 28 to 56 years; median: 35 years.

RESULTS

Overview of family influences on older men’s depression care

Treatment-promoting and treatment-impeding influences of family on older men’s depression care were identified. Overall, one or more examples of treatment promoting influences of family emerged in more than 90% of the interviews with men and the PCPs and one or more examples of treatment-impeding influences of family emerged in over 75% of the interviews with men and PCPs. Each of the individual themes emerged in more than 25% of the interviews with both older men and PCPs with one exception. Only 3 depressed older men (4%) discussed how family had discouraged depression treatment. It is also important to note that within a given family, treatment promoting and treatment impeding roles were not mutually exclusive. In other words, there were examples of particular men for whom family members were reported to respond in ways that both facilitated and impeded depression care.

Treatment promoting roles of family

Family provides emotional support and encouragement

Family members buffered men’s depression by supporting them emotionally, assisting men in coping with depressive symptoms or providing moral encouragement. Several men, for example, described how their wives would counter their feelings of being worthless or useless by emphasizing to men their intrinsic value. Other men described how family members instilled a sense of hope for the future when they felt hopeless. Family members also helped men solve stressful problems or simply encouraged men to talk about their distress. Finally, men described family as emotionally supportive because they were simply “there”, providing companionship and attention that alleviated men’s sense of being isolated, lonely or disvalued.

Family promotes depression self-management in the home

Family’s involvement in older men’s depression treatment often occurred in the broader context of the treatment men received for other chronic illnesses. Men relied on family members, often spouses or daughters, to help them with a variety of aspects of illness management that extended the depression treatment men were receiving in primary care, such as antidepressants or behavioral activation. The family role in illness management included assistance with organization, advice and persuasion and drawing men’s attention to their depressive symptoms. For example, family members organized antidepressants and encouraged or reminded men to take them. When men ignored or minimized depressive symptoms, family members told men their symptoms were serious and encouraged them to talk to their doctors. Family members also helped with other practical aspects of illness management, such as tracking appointments, arranging transportation to doctor’s visits and helping men implement lifestyle changes (e.g. exercise, nutrition, social activity) their doctors recommended.

Family facilitates communication about depression during primary care visits

Family support in the clinic often occurred as part-and-parcel of their participation in older men’s general healthcare. During primary care visits, family members sometimes disclosed information to providers about the man’s depressive symptoms. Family members also supported men in other ways, such as helping men understand doctor’s instructions, translating when an interpreter was not available or simply by being a supportive presence during discussions with doctors about health matters, including depression. In addition, primary care providers emphasized that the family member’s perspective was often helpful in getting a more accurate descriptions of older men’s behavior, particularly when the older man had a tendency to minimize their depression.

Treatment impeding roles of family

Family triggers or worsens depression

Family relationships were also a potential source of stress for depressed older men that contributed to the onset of depression or worsened ongoing symptoms. Men’s depression could, for example, be triggered interpersonal stress, such as marital discord, intergenerational conflict and a sense that family was not caring or attentive. Alternatively, men’s distress could be amplified when family members blamed men for their depression or held stigmatized views of depression or depression treatment. For example, one man expressed distress because his family viewed his depression as a personal moral failing while another complained about how his family viewed depression as “craziness”. These negative perceptions contributed to men’s feelings of being useless or worthless and worsened their depression.

Family hinders depression care during clinic visits

Older men and primary care providers also described how family presence during the primary care visit could hinder communication about depression. In some cases, men were sometimes reluctant to discuss their depression in the presence of family members, either because of concerns about privacy or because they didn’t want to worry or burden their family members. In other situations, family members were perceived as being disruptive during the clinic visits because they were too controlling, critical or because their relationships with older men were simply too dysfunctional.

Family discourages depression treatment

Family members were also described as a source of negative attitudes towards depression and/or depression treatment that discouraged men from seeking help or adhering to treatment. As an example, several men said that family members discouraged adherence to antidepressant medications because they were viewed as “addictive” or for “locos.” In other cases, family members discouraged help-seeking because they viewed depression as a “normal” response to life circumstances and not as a medical issue.

Family is unavailable to help with depression

For some men, family involvement was not an option. Reasons for family unavailability included distance, lack of time, or lack of interest. In other cases, older men had difficult relationships with their family member, making participation in treatment unrealistic. Family views of depression (e.g. as a “normal” part of aging or as “craziness”) were also perceived as barriers contributing to family’s lack of participation in older men’s depression treatment.

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that from the perspectives of both depressed older men and primary care providers, family members play multiple roles in older men’s depression care. The involvement of family members is like the proverbial “double-edged sword” in the sense that it has the potential to promote and/or to impede depression treatment and outcomes. The supportive family roles identified in this study included emotional support, assistance with depression self-management and enhancing care for depression in the clinic by facilitating communication during the clinical encounter with the primary care physician. Unsupportive or treatment impeding roles for family members included triggering or worsening depression, hinder depression care during clinic visits, discouraging and being unavailable to help with depression care. Individual family members sometimes played multiple roles, including those that were both treatment promoting and treatment impeding. These roles are played out in both clinic and also in the home or community.

Our findings are consistent with a larger literature on the positive and negative impact of family support to adults with chronic health conditions (Revenson et al., 1991, Martire et al., 2004), including one study of depression (Martinez et al., 2013). Depression, however, differs from other chronic illnesses in two important respects. First, depression carries considerable social stigma, especially when compared with other many other chronic medical conditions (e.g., lung-related smoking disease). For older men, depression may carry a double-stigma as it can connote both ‘craziness’ and unmanliness (Hinton et al., 2006). Some of the men who were interviewed described how family members had sought to minimize the stigma of depression and to bolster men’s self-esteem. In other instances, family members expressed stigmatized views of depression and discouraged men’s care-seeking and compliance with antidepressants. Second, family troubles and interpersonal conflicts play a much larger direct role in the etiology of clinical depression compared with other common health conditions, such as diabetes, heart disease, and arthritis.

The broad categories identified in this analysis may provide a useful framework for assessing family roles in men’s depression care and have important implications for services research and interventions for depressed older adults. Based on their roles in supporting older men’s depression self-management and their interactions with primary care physicians, family members are natural allies in primary care who can be mobilized to strengthen care within evidence-based models such as collaborative care. Interventions that involve family may, for example, lead to improved treatment adherence (Bolkan et al., 2013) and other positive outcomes. Decisions about family involvement in depression interventions and services should be based on men’s preferences as well as the availability, role(s), preferences and skills of family members.

Family-based interventions also need to take into account the possible adverse impact of family members on older men’s depression treatment or their role in triggering older men’s depression. Family members may, for example, be playing (or have the potential to play) multiple roles in older men’s depression treatment, some of which are treatment promoting and other which are treatment impeding. Identifying and addressing the treatment impeding roles and attitudes of family members may improve outcomes. For example, family members may view depression or depression treatment in stigmatizing terms presenting opportunities for psychoeducation and negotiation of more treatment-promoting roles and attitudes. In some cases, however, the risks of family involvement may outweigh the benefits. Our study suggests the hypotheses that inattention to the role(s) of family may adversely impact older men’s depression care, either by missing opportunities to fully engage family members or to address the negative impact of family members on men’s depression treatment. An important direction for future work is to examine how older men, family members and primary care providers can most productively negotiate family involvement in depression care.

These results must be viewed within the context of our study’s strengths and limitations. Our findings are strengthened because of the convergence of both the primary care physicians’ and older men’s views about the importance and nature of family roles in older men’s depression treatment. Most primary care physicians and older men, for example, identified at least one depression treatment-promoting and one treatment-hindering role of family. It is also important to note that we did not systematically query men or primary care providers about the specific categories reported in this manuscript, but rather these categories emerged during the course of open-ended conversations about older men’s depression. One limitation of our study is that it was conducted in one geographic (rural) region and included only Mexican-origin and white non-Hispanic men of lower socioeconomic status. Therefore, caution must be used in drawing conclusions about older men in other regions, ethnic groups or socioeconomic strata. In addition, our PCPs are a convenience sample and are likely not representative of all the PCPs practicing in these settings or PCPs more generally. Finally, it is important to view the results of this descriptive, qualitative study as exploratory and hypothesis-generating and to highlight the need for further in-depth and theoretically-grounded qualitative research to inform services and interventions.

Our findings highlight the sometimes complex nature of family involvement in older men’s depression care and the kinds of issues that may need to be addressed in both clinical care and in the development of family-centered interventions to close gaps in care for depressed older men. Greater awareness of family roles may assist researchers and primary care physicians in tailoring clinical interventions to meet the needs of older men and more effectively engaging family members as allies in depression treatment. Optimizing family involvement may also help lead to primary care based interventions and services that are both more patient and family-centered (Bodenheimer et al., 2002, Mitnick et al., 2009, Wolff, 2012).

Table 3.

Treatment promoting roles of family members

| Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Family provides emotional support and encouragement | Then my kid, she picked my spirits back up again. You know, hollering at me, ‘you dummy, you are worth more than what you say you are’. Because all of my life, my old man told me that I wasn’t worth shit. I was worthless. (Man) When I am depressed, my wife picks me up. She always has. She’s just a master, you know… My wife will pat me on the head and say, ‘It’ll be better. You are going to see the doctor today. He’ll work something out for you.’ (Man) I mean, she is trying to encourage him, like I have, to try to be a little bit more social, which he hasn’t really been doing. He does tend to sort of isolate himself. There are apparently family members and friends that have tried to get him to go out and do things. (PCP) You can’t deal with depression on your own, you can’t. You have to talk to your spouse or someone that you trust (PCP). |

| Family promotes depression self-management in the home | My son really got on me [when I stopped anti-depressants]. My son told me, ‘You’ve lost the will to live. Get on that medicine! What’s wrong with you?’ He scolded me…(Man) My wife is the pillar of my strength. She labels all of my medicines. She organizes how to take them, how many time, I mean how many milligrams…So she is the driving force as far as my medical support. (Man) P: If the family is there, then you can explain to them, like keep an eye on them. So how is he doing at home? Any improvement? Is he able to go out in a social group? You can make sure he’s doing the right thing. (PCP) [Have the family] tell him if he doesn’t go to church, to go to church, or social activities where he can get involved. Engage him so like he doesn’t go into this isolation mode. I think it’s beneficial to have family involved. (PCP) |

| Family facilitates communication about depression during primary care visits | She [daughter] goes with me when I go see my doctor. If my doctor asks me any questions, she will say, ‘Yes, he was. He was very agitated a couple of days ago,” and stuff like that. I said, ‘it’s just normal stuff.’ She just said that he’s been depressed, and he’s running around crazy.. So the doctor started to ask me question. (Man) She takes care of drugs because she can talk. What if I get mad, I don’t know what to say. She does. (Man) Sometimes, you know, I find it particularly helpful when someone is resistance to their depression to interview the other significant other and get some input from that person. Usually that helps in terms of bringing them on board (PCP) Or some men, they will come in and they will just talk up, “Oh, the weather is great. Fishing is great.” When we talk depression, they don’t want to talk about it…The wife will help. “He’s not going fishing. He’s not doing good.” (PCP) |

TABLE 4.

Treatment impeding roles of family members

| Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Family triggers or worsens depression | The most support one could have is the support of the family, but I don’t know, because of their ignorance, because they don’t have time, or for any reason, but no, they don’t pay attention to me… (Man) But a lot of it [depression] is brought on by things that have happened to me. My experience with my son, you know. That’s a big, for me, it’s like a big betrayal. I expected a lot more from him. (Man) Somebody can have three or four kids, a wife, and maybe 20 or 25 people in the family, but if none of them can understand him or what his problems are, then that does not help at all. It actually worsens the problem. (PCP) Often I see with the depressed, family members are the one that are causing all the stressors. They cause the stressors cause the depression. (PCP) |

| Family presence hinders depression care during clinic visits | I don’t share the whole problem [depression—with family]. I keep it mostly to myself… because I don’t want them to feel sorry for me, I guess. Maybe. [Family will think] ‘He’s feeling bad,’ ‘he’s off,’ you know. (Man) It’s none of their business. It’s mine, my business…They’ve got enough problems. (Man) That could be a big part for the men if it is an older man, and they may not want to talk about it in front of family or even the wife. So I want them to have room to talk about it, so I just ask the family member to step out… (PCP) If it is like a very overbearing family member or they are kind of getting into fights or stuff, then I will ask them to just step out so that I can get the whole story from the patient. (PCP) |

| Family discourages depression treatment | The worse thing about them [family] is that they don’t take into consideration the depression that I have. What I feel they see as something very normal. (Man) Oh, those around [family] say, ‘don’t take that [anti-depressant], that’s for locos [crazies],’ this and that… (Older man) I quit the Effexor, yeah, because my wife was telling me I’m taking too many drugs, too many of this. So I stopped and that and I was like whatever, you know. (Man) He says he’s tired, but he is out there working in the yard. Yeah, he’ll come in and take a nap, but he is 80-something or whatever. So she is sort of trying to normalize it. (PCP) |

| Family is unavailable to help with depression | You see, I have always wanted them to come with me [to the doctor], but no one wants to. (Man) I can call them up or stuff, but they won’t come visit me and they don’t have nothing to do with me at all. I have a son and a daughter, and four grandchildren, and they don’t have nothing to do with me. (Man) I would say less than 10 percent have support or a family member coming in. (PCP) Well, the family is really important because if an older man is lonely or alone, and he is just going to kill himself because there’s very little support around him. There is no anchor, I guess, to a point. (PCP) |

Key points.

Seven different types of roles were identified for family members,

Family roles may be either treatment promoting or treatment impeding,

Depression interventions and services that include family members need to consider both positive and negative aspects of family involvement.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grant R01-MH080067 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Ladson Hinton and Carolina Apesoa-Varano received support from the UC Davis Latino Aging Research Resource Center (Resource Center for Minority Aging Research) under NIH/NIA Grant P30-AG043097 and NIH/NIMH R34-MH099296. The content of this article does not represent the official views of NIMH, NIA or NIH. The sponsors did not participate in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Rachel Turner M.S.W., Emily He B.A. and Cindy Tran M.P.H. in data analysis (all of whom received funding from R01-MH080067).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to report.

Ladson Hinton had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Contributor Information

Ladson Hinton, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of California Davis.

Ester Carolina Apesoa-Varano, Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing, University of California Davis.

Jurgen Unutzer, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington.

Megan Dwight-Johnson, Rand Group Los Angeles.

Mijung Park, School of Nursing, University of Pittsburgh.

Judith C. Barker, Department of Anthropology, History & Social Medicine, University of California San Francisco.

References

- Addis ME, Mahalik JR. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychologist. 2003;58:5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apesoa-Varano EC, Hinton L, Barker JC, Unutzer J. Clinician approaches and strategies for engaging older men in depression care. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2010;18:586–595. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181d145ea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. Journal of American Medical Association. 2002;288:2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolkan CR, Bonner LM, Campbell DG, Lanto A, Zivin K, Chaney E, Rubenstein LV. Family involvement, medication adherence, and depression outcomes among patients in veterans affairs primary care. Psychiatric Services. 2013;64:472–478. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittin N. Qualitative interviews in medical research. British Medical Journal. 1995;311:251–253. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenail RJ. How to conduct clinical qualitative research on the patient’s experience. The Qualitative Report. 2011;16:1173–1190. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal S, Sambamoorthi U, Walkup JT, Akincigil A. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in the elderly medicare population: predictors, disparities, and trends. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51:1718–1728. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwight-Johnson M, Apesoa-Varano C, Hay J, Unutzer J, Hinton L. Depression treatment preferences of older white and Mexican origin men. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2013;35:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, Stange KC. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Affairs. 2010;29:1489–1495. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L, Apesoa-Varano EC, Gonzalez HM, Auguilar-Gaxiola S, Dwight-Johnson M, Barker J, Tran C, Zuniga R, Unutzer J. Falling through the cracks: gaps in depression treatment among older Mexican-origin and white men. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012;27:1283–1290. doi: 10.1002/gps.3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L, Zweifach M, Oishi S, Unutzer J. Gender disparities in the treatment of late-life depresion: qualitative and quantitative findings from the IMPACT trial. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14:884–892. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000219282.32915.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care. 2003;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez I, Interian A, Guarnaccia PJ. Antidepressant adherence among Latinos: the role of the family. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2013;10:63–85. [Google Scholar]

- Martire LM, Lustig AP, Schulz R, Miller GE, Helgeson VS. Is it beneficial to involve a family member? A meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for chronic illness. Health Psychology. 2004;23:559–611. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam SB. Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mitnick S, Leffler C, Hood VL. Family caregivers, patients and physicians: ethical guidance to optimize relationships. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;25:255–260. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1206-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller-Leimkuhler AM. Barriers to help-seeking by men: a review of sociocultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;71:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00379-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M, Unutzer J. Geriatric depression in primary care. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2011;34:469–488. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revenson TA, Schiaffino KM, Majerovitz DS, Gibofsky A. Social support as a double-edged sword: the relation of positive and problematic support to depression among rheumatoid arthritis patients. Social Science and Medicine. 1991;33:807–813. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90385-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM. The patient-centered medical home: will it stand the test of health reform? JAMA. 2009;301:2038–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods: whatever happened to the qualitative description. Research in Nursing and Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers SL, White T, Zubritsky C, Oslin DW. Family involvement in the care of healthy medical outpatients. Family Practice. 2006;23:317–324. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz A, Weiner SJ, Harris IB, Binns-Calvey A. An educational intervention for contextualizing patient care and medical students’ abilities to probe for contextual issues in simulated patients. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304:1191–1197. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange KC, Miller WL, Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Stewart EE, Jaen CR. Context for understanding the National Demonstration Project and the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(Suppl 1):S2–8. S92. doi: 10.1370/afm.1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unutzer J, Katon W, Williams JWJ, Callahan CM, Harpole L, Hunkeler EM, Hoffing M, Arean P, Hegel MT, Schoenbaum M, Oishi SM, Langston CA. Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multicenter randomized trial. Medical Care. 2001;39:785–799. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner SJ, Schwartz A, Weaver F, Goldberg J, Yudkowsky R, Sharma G, Binns-Calvey A, Preyss B, Schapira MM, Persell S, Jacobs E, Abrams RI. Contextual errors and failures in individual patient care: a multicenter study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2010;153:69–75. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-2-201007200-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JL. Family matters in health care delivery. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;308:1529–1530. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.13366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JL, Roter DL. Older adults’ mental health function and patient-centered care: Does the presence of a family companion help or hinder communication? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2011;27:661–668. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1957-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]