Abstract

Human obesity has been linked to genetic factors and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) SNPs have been associated with up to 6% frequency in morbidly obese children and adults. A potential therapy for individuals possessing such genetic modifications is the identification of molecules that can restore proper receptor signaling and function. These compounds could serve as personalized medications improving quality of life issues as well as alleviating diseases symptoms associated with obesity including type 2 diabetes. Several hMC4 SNP receptors have been pharmacologically characterized in vitro to have a decreased, or a lack of response, to endogenous agonists such as α-, β-, and γ2-melanocyte stimulating hormones (MSH) and adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH). Herein we report the use of a mixture based positional scanning combinatorial tetrapeptide library to discover molecules with nM full agonist potency and efficacy to the L106P, I69T, I102S, A219V, C271Y, and C271R hMC4Rs. The most potent compounds at all these hMC4R SNPs include Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2, Ac-His-(pCl)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2, Ac-His-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2, and Ac-Arg-(pCl)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2, revealing new ligand pharmacophore models for melanocortin receptor drug design strategies.

Introduction

The melanocortin system is comprised of five G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) that stimulate the adenylate cyclase signal transduction pathway.1−7 The endogenous ligands are derived by post-translational processing of the pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) protein by prohormone convertases PC1 and PC2 to generate the endogenous melanocortin agonist peptides α-, β-, and γ2-melanocyte stimulating hormones (MSH) and adrenocorticotropin (ACTH).8−10 The human melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) has been identified by genomic wide association studies as well as in individual morbidly obese humans to be a locus connected to obesity.11,12 Greater than 100 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified to date in obese and nonobese human control adults and children. Substantial efforts have been undertaken to characterize these hMC4R SNPs both physiologically and in vitro to determine molecular deficits associated with each hMC4R SNP. The most common molecular defects that have been identified in vitro include the lack of the hMC4R SNP to (a) traffic to the cell membrane surface for expression, (b) decreased endogenous agonist binding and/or molecular recognition, and (c) reduced/absent endogenous agonist potency and/or efficacy. Several hMC4R SNPs have been pharmacologically characterized to possess one or more of these molecular defects. Once these in vitro pharmacological characterizations have been performed for individual hMC4R SNPs, the next goal is to determine strategies to restore normal function to the SNP as a pathway toward the development of therapeutic approaches to return afflicted individuals to an increased quality of life and decrease their genetic predisposition toward an insatiable hunger and obesity. Toward this objective, we hypothesized that we could identify molecules that could target hMC4R SNPs that are expressed at the cell surface but do not respond normally to the endogenous agonists α-, β-, and γ2-MSH and ACTH. Different experimental approaches are available including a rational ligand design/discovery strategy,13 however, this is limited by the known structure–activity relationships (SAR) and the assumptions and limitations of our current knowledge. An alternative unbiased approach involves the screening of synthetic combinatorial libraries that are designed with no preconceived ligand SAR assumptions. This approach has previously been described for the discovery of novel ligands,14 and in particular for μ, δ, and κ opioid receptors15 as well as formyl peptide receptors (FPR1 and FPR2)16 among others.

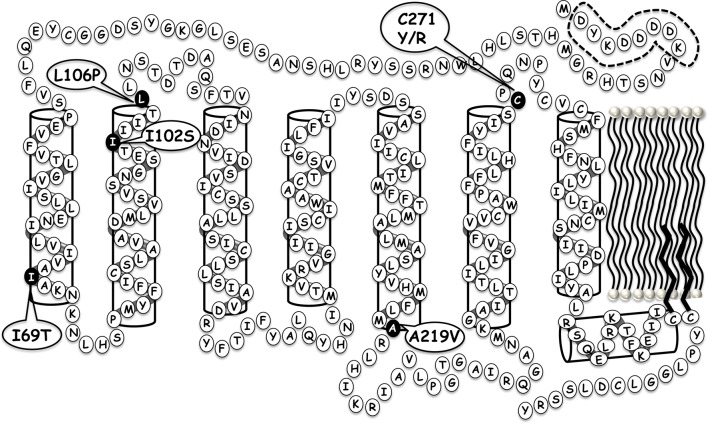

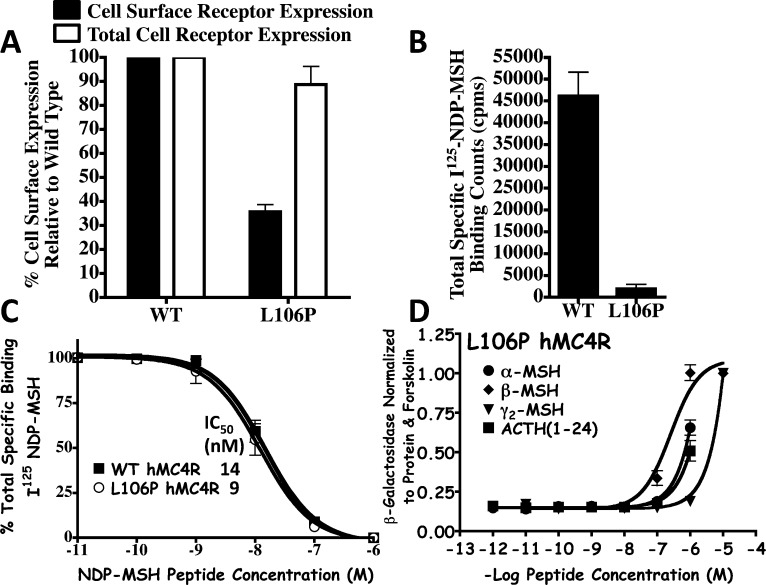

To test this hypothesis and validate this experimental approach for polymorphic hMC4 receptors, the L106P hMC4R (Figure 1) was selected as a rigorous target for the study herein. The L106P hMC4R SNP was identified in an individual included in a 350 patient study of severe early onset obesity (including 108 control patients) and pharmacologically characterized in vitro to modify cell surface expression levels as well as affect ligand function.17,18 Studies by our laboratory pharmacologically characterized this L106P hMC4R SNP to possess reduced cell surface expression, normal NDP-MSH ligand binding affinity, and significantly impaired endogenous agonist potency (Figure 2 and Table 1).19 Upon the basis of the location at the juncture of the receptor TM domain and the extracellular portion, as well as the substitution from the flexible aliphatic Leu amino acid to the constrained Pro residue that is known to be a “helix breaker,” it could be envisioned that this particular SNP might be modifying the putative receptor binding pocket important for molecular recognition and ligand accessibility crucial for the formation of the ligand–receptor complex required for initiating the intracellular signal transduction process. Further characterization of the L106P hMC4R in attempts to identify ligands based upon rational design approaches13 resulted in the discovery that the tetrapeptides JRH887-9 (1), JRH420-12 (2), and JRH322-18 (3) possessed nM full agonist potencies whereas the endogenous agonists did not (Table 1).20,21 The tetrapeptides were designed based upon the common melanocortin core His-Phe-Arg-Trp conserved sequence (Table 1) present in all the endogenous melanocortin agonists reported to date. These core tetrapeptide residues have been widely accepted to contain the critical pharmacophore domain for melanocortin receptor selectivity (versus other GPCRs) and agonist induced cAMP signal transduction. Thus, this polymorphic L106P hMC4R presented itself as an opportunity to test our hypothesis. Herein, we present the successful application of this approach to identify molecules that can not only restore full functional signaling and efficacy of the L106P hMC4R SNP but results in the discovery of previously unidentified chemotypes for further melanocortin based drug discovery and development efforts. It is worthy of note that some of these chemotypes are more potent than the lead tetrapeptides previously reported in the literature. As it has been established that hMC4R SNPs constitute 1–6% of the genetic modifications identified in morbidly obese (BMI > 30%) human patients and to further explore the applicability of the newly discovered tetrapeptides to extend to other hMC4 polymorphic receptors that do not respond normally to the endogenous agonists, the additional five hMC4R SNP receptors, I69T, I102S, A219V, C271Y, and C271R, distributed at different positions within the protein (Figure 1), were examined with the eight selected L106P “hit” ligands. Melanocortin receptor subtype selectivity profiles at the mouse MC1R, MC3R, MC4R, and MC5R was also characterized for the eight “hit” tetrapeptides.

Figure 1.

Putative locations of the I69T, I102S, L106P, A219V, C271Y, and C271R SNPs within the serpentine structure of the hMC4R.

Figure 2.

Summary of the previously reported in vitro pharmacological characterization of the L106P hMC4R SNP as compared with the wild-type (WT) hMC4R control stably expressed in HEK293 cells.13,19 (A) Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) demonstrating that both the WT and L106P hMC4R proteins are expressed within the cell at approximately the same levels (white box) yet reduced cell surface expression is observed for the L106P hMC4R (black box). (B) Represents the total specific binding counts per minute (cpm) of radiolabeled I125-NDP-MSH agonist binding to the cells stably expressing the WT and L106P hMC4Rs. (C) Illustrates the ligand binding affinity curves of the WT and L106P hMC4Rs competing I125-NDP-MSH and unlabeled NDP-MSH in a dose–response fashion that result in the same IC50 values, within experimental error. (D) Illustrates the pharmacological agonist dose–response curves for the endogenous melanocortin agonists α-, β-, and γ2-MSH and ACTH at the L106P hMC4R.

Table 1. Amino Acid Sequences of the Endogenous and Synthetic Melanocortin Ligands Characterized at the Wild-Type (WT) and L106P hMC4R.

| name | amino acid sequence |

|---|---|

| α-MSH | Ac-Ser-Tyr-Ser-Met-Glu-His-Phe-Arg-Trp-Gly-Lys-Pro-Val-NH2 |

| β-MSH | Ala-Glu-Lys-Lys-Asp-Glu-Gly-Pro-Tyr-Arg-Met-Glu-His-Phe-Arg-Trp-Gly-Ser-Pro-Pro-Lys-Asp |

| γ2-MSH | Tyr-Val-Met-Gly-His-Phe-Arg-Trp-Asp-Arg-Phe-Gly |

| ACTH(1-24) | Ser-Tyr-Ser-Met-Glu-His-Phe-Arg-Trp-Gly-Lys-Pro-Val-Gly-Lys-Lys-Arg-Arg-Pro-Val-Lys-Tyr-Pro-Asn |

| (1) JRH887-9 | Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 |

| (2) JRH420-12 | Ac-Anc-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 |

| (3) JRH322-18 | Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 |

| peptide | WT hMC4R agonist EC50a (nM) | L106P hMC4R agonist EC50a (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| α-MSH | 0.65 ± 0.19 | 50% @ 1 μM |

| β-MSH | 0.42 ± 0.13 | 356 ± 53 |

| γ2-MSH | 73 ± 24 | 2660 ± 370 |

| ACTH(1-24) | 0.65 ± 0.15 | 40% @ 1 μM |

| (1) JRH887-9 | 0.93 ± 0.3 | 191 ± 15 |

| (2) JRH420-12 | 2.17 ± 0.82 | 60 ± 12 |

| (3) JRH322-18 | 1.25 ± 0.25 | 52 ± 10 |

Previously published values from refs (13) and (19). The mean of at least three independent experiments ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) is provided. A % indicates that at the highest concentration tested, some stimulatory response was observed, but not the full efficacy observed for the nonreceptor dependent forskolin control.

Results and Discussion

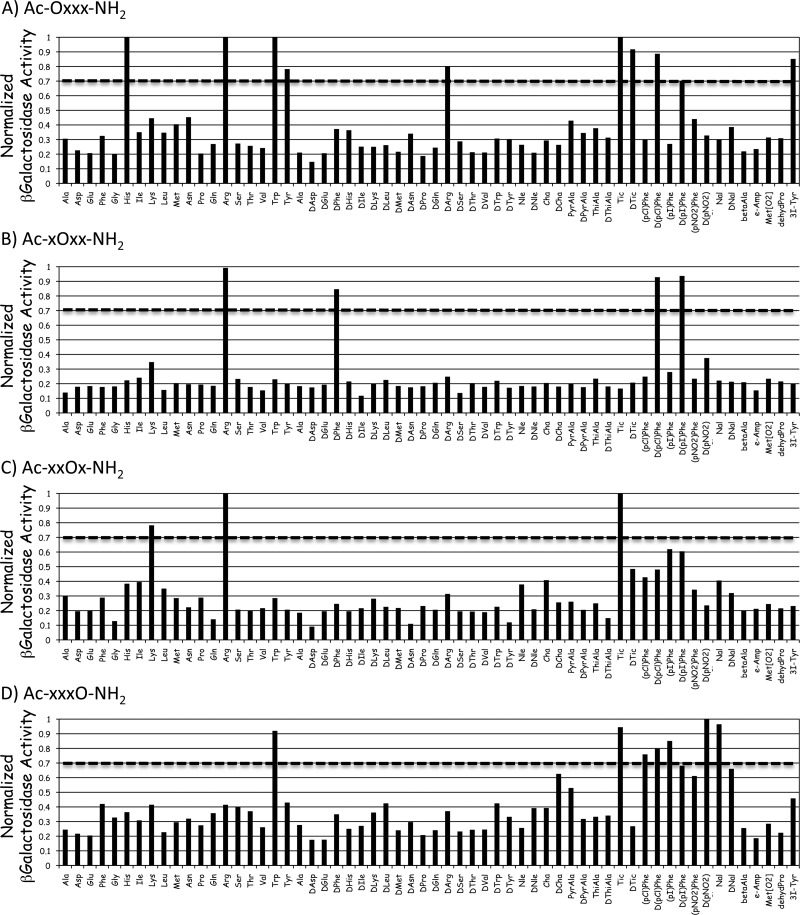

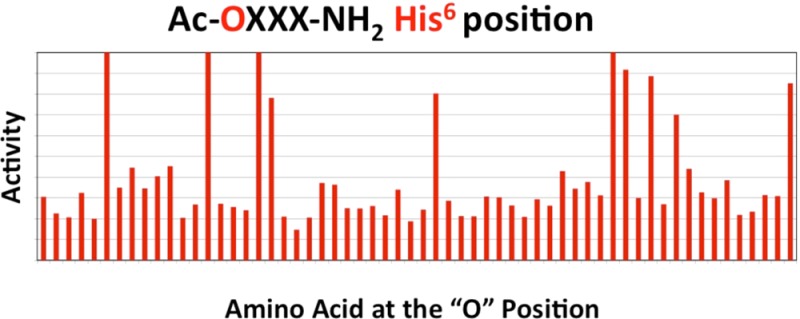

The wild type and L106P, I69T, I102S, A219V, C271Y, and C271R hMC4R stably expressing HEK293 cells previously characterized by our laboratory were used for the studies presented herein.13,19,22 A mixture based positional scanning combinatorial library (TPI 924), consisting of the Ac-tetrapeptide-NH2 template composed of 60 different amino acids (comprised of natural l-amino acids, their d-isomers, and unnatural amino acids) at each position and containing a total of 12960000 tetrapeptides was screened at the L106P hMC4R at 100 μg/mL concentrations in a 96-well plate format. Figure 3 illustrates the results from the primary agonist functional screen with the average of duplicate wells that have been normalized to the protein content of each well as well as the average of quadruple wells for the nonreceptor dependent forskolin control. Forskolin was selected as a positive control as it is well established to stimulate a cAMP signal transduction response directly and is not dependent upon the melanocortin receptor. Results with an agonist stimulation response greater than 0.7 were considered “hits” at the indicated position. These are summarized in Table 2. The threshold of 0.7 was selected to increase the chances for the identification of potent full agonist compounds while balancing the resource considerations of time, labor, and expense regarding the number of individual ligands that would need to be synthesized and analytically and pharmacologically characterized.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the primary screening results of the TPI 924 tetrapeptide library at the L106P hMC4R. The primary screen was assayed using a rough approximation at 100 μg/mL concentrations. The X-axis represents the amino acid residue that was held constant at that position (O) of the tetrapeptide library with the three remaining positions composed of mixtures of the 60 amino acids (X), and the Y-axis represents the functional agonist activity observed. The agonist activity (average of duplicate wells) was determined using a β-galactosidase colorimetric reporter gene bioassay that has been normalized to both relative protein content as well as the maximal value observed for the nonreceptor dependent forskolin control (average of four wells). A value of 1 indicates a result that is able to generate the same maximal stimulation level observed for the forskolin control. The dotted line for each position indicates the criteria of >0.7 that was used as the cut-off point for classification as deconvolution “hits”.

Table 2. Summary of the Primary Screening Deconvolution Hits at Each Position That Resulted in the Criterion of a Stimulatory Response >0.7.

| Ac-AA1 | AA2 | AA3 | AA4-NH2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| His | Arg | Lys | Trp |

| Arg | DPhe | Arg | Tic |

| Trp | (pCl)DPhe | Tic | (pCl)Phe |

| DArg | (pI)DPhe | (pCl)DPhe | |

| Tyr | (pI)Phe | ||

| Tic | (pNO2)DPhe | ||

| DTic | Nal | ||

| (pCl)DPhe | |||

| (pI)DPhe | |||

| (3I)Tyr |

AA represents amino acid and the position in the tetrapeptide template.

Of first importance is to validate the overall screening experiment. This validation is supported by the fact that this mixture based positional scanning library approach identified active mixtures that contained amino acids in defined positions that corresponded to Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 (1) and Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 (3) tetrapeptides that were previously reported to stimulate the L106P hMC4R at nM concentrations.13 The Anc residue of tetrapeptide 2 was not included in the library screened. Furthermore, additional mixtures defined with other residues were consistent with previously reported SAR studies of similar tetrapeptides at the mouse melanocortin receptors.20,21,23−25 The library screening also identified the mixtures fixed with (pI)DPhe and (pCl)DPhe at the second amino acid position of the tetrapeptide as active, confirming previous in vitro SAR studies20,21 and in vivo feeding studies26 demonstrating the Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 (3) tetrapeptide as a pharmacological tool and implicating a role for the centrally expressed MC3R to be involved in the regulation of food intake.26 At this juncture, we took two parallel approaches. First, we synthesized tetrapeptides with the amino acids identified at the respective positions from the tetrapeptide library screening (Tables 2 and 3) into the tetrapeptide template Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 (1). Using this approach, we did not identify any new sequences with agonist EC50 values less than 40 nM at the L106P hMC4R.

Table 3. Summary of the Individually Synthesized Tetrapeptides Incorporating Amino Acids Identified from the Primary Screen into the Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 Melanocortin Agonist Templatea.

| compd | EMH reference peptide | sequence | WT hMC4R agonist EC50 (nM) | L106P hMC4R agonist EC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | control (JRH887-9) | Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 | 2.6 ± 1.6 | 215 ± 83 |

| EMH4-91 | Ac-Arg-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 | 1.06 ± 0.24 | 124 ± 28 | |

| EMH4-92 | Ac-Trp-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 | 32 ± 8 | 170 ± 114 | |

| EMH4-93 | Ac-Tyr-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 | 6.2 ± 2 | 540 ± 195 | |

| EMH4-94 | Ac-DArg-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 | 40 ± 5 | 1242 ± 360 | |

| EMH4-95 | Ac-His-Arg-Arg-Trp-NH2 | 75 ± 19 | 4940 ± 770 | |

| EMH4-96 | Ac-His-DPhe-Lys-Trp-NH2 | 40 ± 16 | 6240 ± 506 | |

| EMH4-97 | Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-(pCl)Phe-NH2 | 17 ± 5 | 2096 ± 695 | |

| EMH4-98 | Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-(pCl)DPhe-NH2 | 46 ± 26 | 8230 ± 4810 | |

| EMH4-99 | Ac-Tic-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 | 15 ± 7 | 4940 ± 1980 | |

| EMH4-100 | Ac-DTic-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 | 297 ± 59 | 17920 ± 1150 | |

| EMH4-101 | Ac-(pCl)DPhe-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 | 48 ± 4 | 4440 ± 830 | |

| EMH4-102 | Ac-(pI)DPhe-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 | 76 ± 35 | 4910 ± 2630 | |

| EMH4-103 | Ac-(3I)Tyr-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 | 1.9 ± 0.40 | 43 ± 7 | |

| 12 | EMH4-104 | Ac-His-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 | 0.28 ± 0.04 | 48 ± 16 |

| 3 | EMH4-105 | Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 | 1.3 ± 0.47 | 97 ± 48 |

| EMH4-106 | Ac-His-DPhe-Tic-Trp-NH2 | 204 ± 73 | 18800 ± 5170 | |

| EMH4-107 | Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Tic-NH2 | >10,000 | >100,000 | |

| EMH4-108 | Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 5.3 ± 1.3 | 680 ± 150 | |

| EMH4-109 | Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-(pNO2)Phe-NH2 | 195 ± 20 | 23000 ± 9400 | |

| EMH4-110 | Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Nal(1′)-NH2 | 28 ± 1 | 4280 ± 1120 |

The indicated errors represent the standard error of the mean determined from at least three independent experiments; >10000 and >100000 indicates that agonist or antagonist activity was not observed for these compounds at up to 10 and 100 μM concentrations respectively.

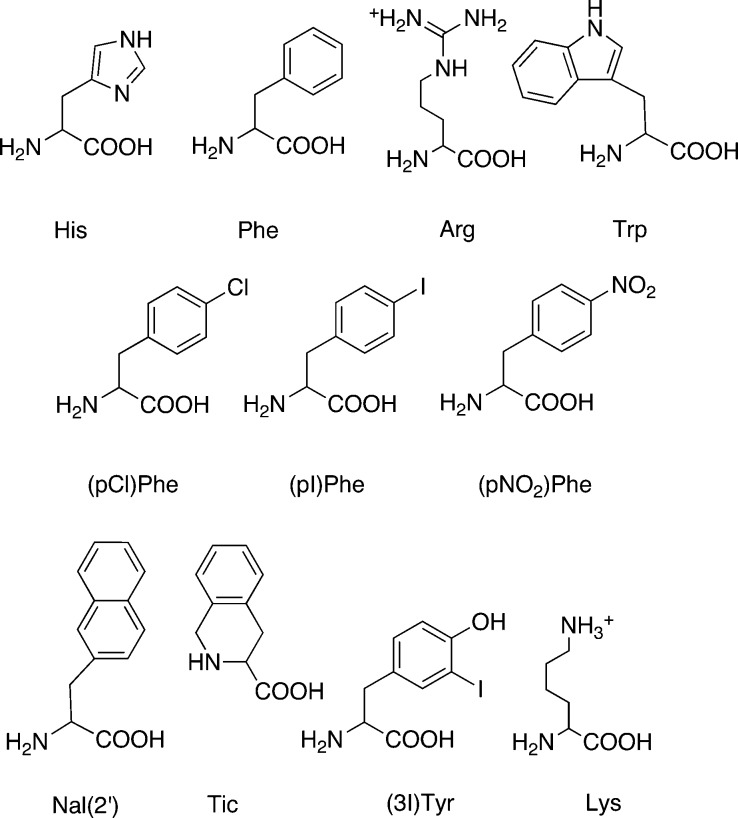

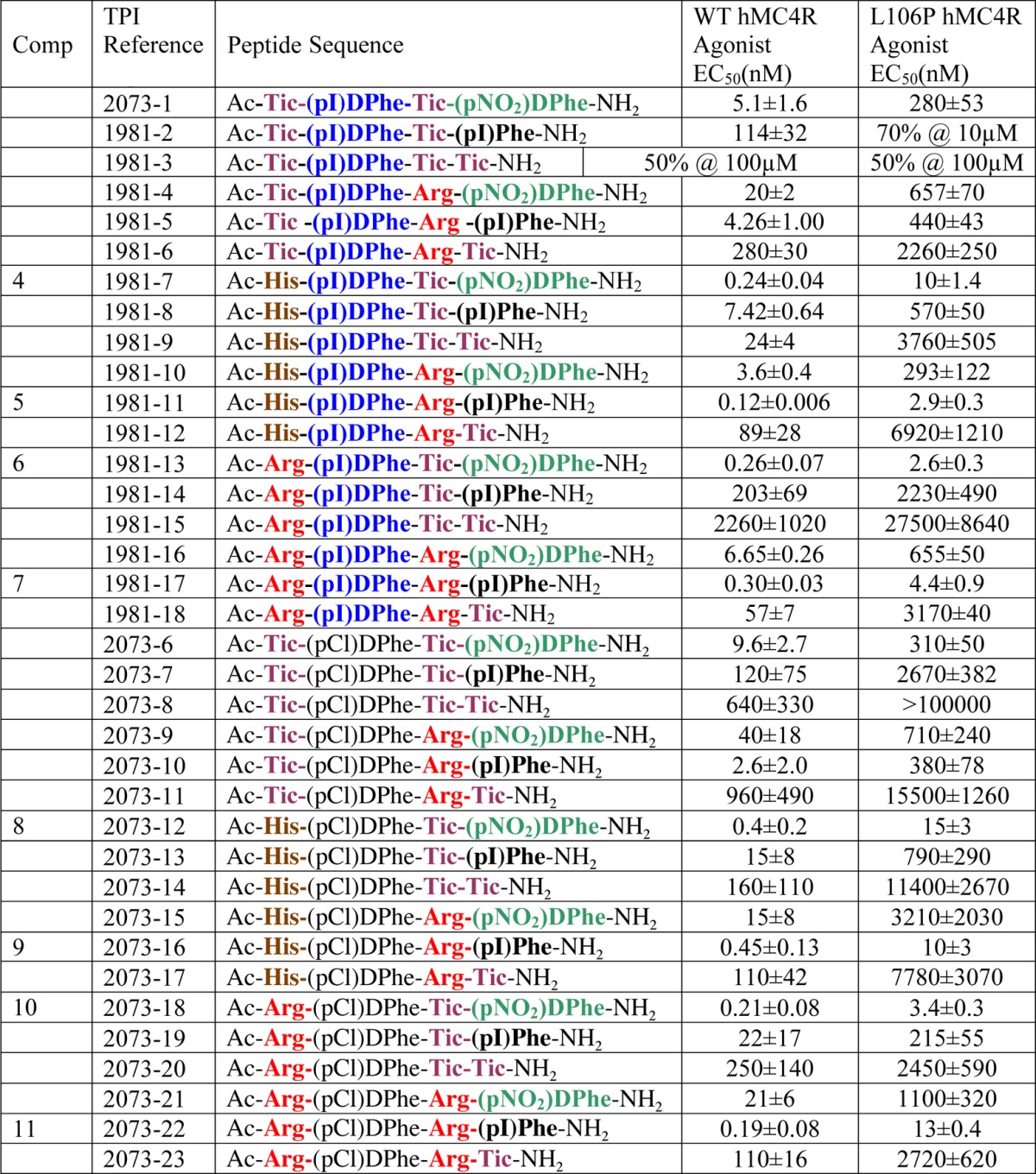

The second approach was to utilize the deconvolution of the positional scanning library, where the individual tetrapeptides were selected for synthesis by combining the defined functionalities of the most active mixtures at each position (Figure 3 and Table 2). This was done by testing the active mixtures from the library in a dose–response manner in order to identify the most active mixtures at each of the four positions of the tetrapeptide library. By ranking these mixtures at each position by the activities, one can then select the amino acid that is defined in each active mixture at each position. In this case, three amino acids were selected from position 1 (Tic, His, Arg), two amino acids from position 2 [(pI)DPhe, (pCl)DPhe], two amino acids from position 3 (Tic, Arg), and three amino acids from position 4 [(pNO2)DPhe, (pI)Phe, Tic], Figure 4. The combinations of these amino acids were used to design a set of tetrapeptides and resulted in 36 (3 × 2 × 2 × 3) unique sequences. These tetrapeptides were synthesized, and the results of the agonist pharmacology are summarized in Table 4 for the L106P and wild type control hMC4Rs. This series of tetrapeptides resulted in identification of the tetrapeptides Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 (1981-11, 5), Ac-Arg-(pI)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 (1981-13, 6), and Ac-Arg-(pI)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 (1981-17, 7) possessing 2–4 nM full agonist EC50 values at the L106P hMC4R and Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 (1981-7, 4) that possessed a 10 nM full agonist EC50 value at the L106P hMC4R, as it could be anticipated based upon the results of the primary screen (Figure 3). Also, peptides containing (pCl)DPhe at the second position resulted in the tetrapeptide Ac-Arg-(pCl)Phe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 (2073-18, 10) that possessed ca. 3 nM full agonist efficacy at the L106P hMC4R while the Ac-His-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 (2073-16, 9), Ac-Arg-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 (2073-22, 11), and Ac-His-(pCl)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 (2073-12, 8) possessed 10, 13, and 15 nM full agonist EC50 values at the L106P hMC4R, respectively. Thus, we have provided conclusive experimental data to support the hypothesis that novel and potent molecules could be identified to target hMC4R SNPs that are expressed at the cell surface but do not respond normally to the endogenous agonists α-, β-, and γ2-MSH and ACTH using an unbiased mixture based positional scanning combinatorial library screening approach.

Figure 4.

Summary of the key amino acid structures used in this study.

Table 4. Summary of the Individually Synthesized Tetrapeptides Based upon the Screening Data Obtained from the Positional Scanning Library TPI924a.

The indicated errors represent the standard error of the mean determined from at least three independent experiments. A % indicates that at the highest concentration tested, some stimulatory response was observed, but not the full efficacy observed for the nonreceptor dependent forskolin control; >100000 indicates that agonist or antagonist activity was not observed for these compounds at up to 100 μM concentrations.

Effects at Other Polymorphic hMC4Rs

Our laboratory has previously reported the side-by-side pharmacological comparison of 70 polymorphic hMC4Rs.13,19,22 Because the above tetrapeptides 4–11 were identified as possessing full agonist nM potency at the L106P polymorphic hMC4R, we wanted to evaluate these selected ligands at other polymorphic hMC4Rs that did not respond normally to the endogenous agonists (Table 5). The I69T,17,22,27 I102S,13,19,28−30 A219V,22,31 C271Y,13,17−19,32,33 and C271R17,22 hMC4Rs were selected (Figure 1) to be characterized with the eight tetrapeptides summarized in Table 5. These polymorphic hMC4R amino acid substitutions are located in distinct regions of the receptor and putatively have different molecular features important for the hMC4R molecular recognition and functional agonist stimulation. Four (4, 8, 9, and 10) of the eight tetrapeptides could stimulate nM to μM full agonist functional response at these additional five polymorphic hMC4Rs. The other four tetrapeptides were able to stimulate a full agonist response at the I69T, I102S, and A219V hMC4Rs with 6, a weak μM full agonist at the C271Y hMC4R. Clearly, the C271Y/R polymorphic receptors are the most challenging of the polymorphic hMC4Rs examined in this study to restore full agonist nM efficacy with the tetrapeptides examined. Although we present here the determination of agonist activity at multiple polymorphic receptors for ligands identified for the L106P hMC4R, the identification of ligands that restore agonist activity of more than one polymorphic receptor could be explored directly using the screening results of a combinatorial library with the polymorphic hMC4Rs of interest.

Table 5. Summary of the Selected Tetrapeptides at Other hMC4R Polymorphic Receptorsa.

| compd | structure | WT hMC4R agonist EC50(nM) | L106P hMC4R agonist EC50(nM) | I69T hMC4R agonist EC50(nM) | I102S hMC4R agonist EC50(nM) | A219V hMC4R agonist EC50(nM) | C271Y hMC4R agonist EC50(nM) | C271R hMC4R agonist EC50(nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1b | Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 | 0.93 ± 0.3 | 191 ± 15 | 40.7 ± 5.1 | 720 ± 28 | 9.78 ± 1.12 | 1200 ± 110 | 1600 ± 1060 |

| 4 | Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 10 ± 1.4 | 3.8 ± 0.22 | 14 ± 2.3 | 4.5 ± 0.34 | 190 ± 42 | 295 ± 90 |

| 5 | Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | >100000 | >100000 |

| 6 | Ac-Arg-(pI)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 0.26 ± 0.07 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 1.5 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 6.1 ± 0.93 | 19650 ± 6410 | >100000 |

| 7 | Ac-Arg-(pI)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 0.29 ± 0.03 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 14 ± 1.4 | >100000 | >100000 |

| 8 | Ac-His-(pCl)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 0.40 ± 0.20 | 15 ± 3 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 1.7 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 82 ± 7 | 130 ± 8 |

| 9 | Ac-His-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 0.45 ± 0.13 | 10 ± 3 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 20 ± 6 | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 260 ± 120 | 210 ± 72 |

| 10 | Ac-Arg-(pCl)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 0.21 ± 0.08 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 5.2 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 470 ± 260 | 3390 ± 2460 |

| 11 | Ac-Arg-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 0.19 ± 0.08 | 13 ± 0.4 | 8.2 ± 1.2 | 13 ± 1.9 | 17 ± 6 | >100000 | >100000 |

Melanocortin Receptor Subtype Profiles at the Mouse MC1R and MC3-5Rs and Unanticipated Structure Activity Relationships (SAR)

The mouse melanocortin receptor isoforms, versus the human, were selected to characterize differences in ligand–receptor subtype profiles as any interesting compounds in our laboratory are examined subsequently in vivo in the wild-type and/or melanocortin knockout receptor mouse models.26,34−39 Table 6 summarizes the selected eight tetrapeptides at the mouse MC1, MC3, MC4, and MC5 receptors. All these tetrapeptides are full agonists with potencies ranging from ca. 0.5 to 94 nM at these mouse melanocortin receptors examined. As both the MC3 and MC4 receptors are expressed in the hypothalamus of the brain, selectivity between these two isoforms could be important for the interpretation of physiological in vivo data. The tetrapeptides in Table 6 exhibited modest MC4R versus MC3R selectivity profiles with the 4, 5, and 6 possessing 15–17-fold selectivity. At the mMC1R, which is expressed primarily in the skin, the full agonist potency EC50 values of these compounds range from ∼3 to 40 nM. At the mMC3R, which is expressed both centrally and peripherally, the full agonist potency EC50 values range from 12 to 94 nM. At the mMC4R, expressed primarily in the brain and CNS, full agonist potency EC50 values range from 0.7 to less than 8 nM. At the mMC5R, which is the most widely expressed subtype both in the brain, CNS, and periphery, full agonist potency EC50 values range from 0.45 to ∼5 nM and possessed the greatest ligand potency versus the other receptor isoforms.

Table 6. Summary of the Selected Tetrapeptides at the Mouse Melanocortin Receptors for Subtype Selectivity Profilesa.

| peptide | structure | mMC1R EC50 (nM) | mMC3R EC50 (nM) | mMC4R EC50 (nM) | mMC5R EC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDP-MSH | Ac-Ser-Tyr-Ser-Nle-Glu-His-DPhe- Arg-Trp-Gly-Lys-Pro-Val-NH2 | 0.088 ± 0.031 | 0.33 ± 0.08 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.05 |

| 4 | Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 35 ± 5 | 2.4 ± 1 | 0.84 ± 0.15 |

| 5 | Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 12 ± 3.8 | 11.7 ± 1.0 | 0.70 ± 0.13 | 0.45 ± 0.13 |

| 6 | Ac-Arg-(pI)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 2.7 ± 1.3 | 47 ± 8 | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 1.1 ± 0.24 |

| 7 | Ac-Arg-(pI)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 40 ± 11 | 22 ± 9 | 4.3 ± 1.1 | 3.0 ± 1.3 |

| 8 | Ac-His-(pCl)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 55 ± 13 | 5.2 ± 1.1 | 0.63 ± 0.2 |

| 9 | Ac-His-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 19 ± 0.9 | 19 ± 8 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.6 |

| 10 | Ac-Arg-(pCl)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 22 ± 16 | 94 ± 16 | 7.6 ± 2 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| 11 | Ac-Arg-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 24 ± 7 | 21 ± 4 | 7.4 ± 1.1 | 5.1 ± 0.9 |

The indicated errors represent the standard error of the mean from at least three independent experiments.

The tetrapeptide 3 containing the single (pI)DPhe at the second position has been previously reported to result in partial agonist/antagonist mMC3R and full agonist mMC4R pharmacological profiles.21,24 Additionally, in the NDP–MSH 13 amino acid peptide template, the (pI)DPhe7 (α-MSH numbering) containing peptide was reported to result in partial agonist/antagonist pharmacological profiles at both the hMC3 and hMC4 receptors.40 Incorporation of the (pI)DPhe into a chimeric AGRP–melanocortin template resulted in a mMC3R antagonist with partial agonist/antagonist pharmacology at the mMC4R.41 Despite the previously reported melanocortin ligand SAR, the four multiple substitution containing tetrapeptides possessing the (pI)DPhe at the second position examined at the mouse MCRs resulted in full agonists at the mMC3R (Table 6). Furthermore, on the basis of melanocortin receptor mutagenesis studies and the majority of ligand SAR, presence of the Arg residue has been previously hypothesized as important for ligand potency, molecular recognition, and putative ligand–receptor interactions important for agonist induced signal transduction.42−56 However, it was noted in a few reports that the Arg residue could be replaced by Ala or other residue/side chain modifications and still retain agonist functionality at the melanocortin receptors.25,55,57 Herein, the 4 and 8 are further unanticipated examples of melanocortin ligands; specifically, they are tetrapeptides that do not contain the Arg side chain moiety and are still full agonists at the melanocortin receptors. Surprisingly, these two tetrapeptides are not only sub-nM to nM full agonists at the mMC1, mMC3–5Rs (Table 6), but they also possess nM full agonist potency at all the six the polymorphic hMC4Rs examined in this study (Tables 4 and 5). To further probe their ligand biophysical properties in attempts to identify a common ligand feature between these Arg deficient ligands and the other tetrapeptides examined in this study, the following computational biophysical analysis was performed.

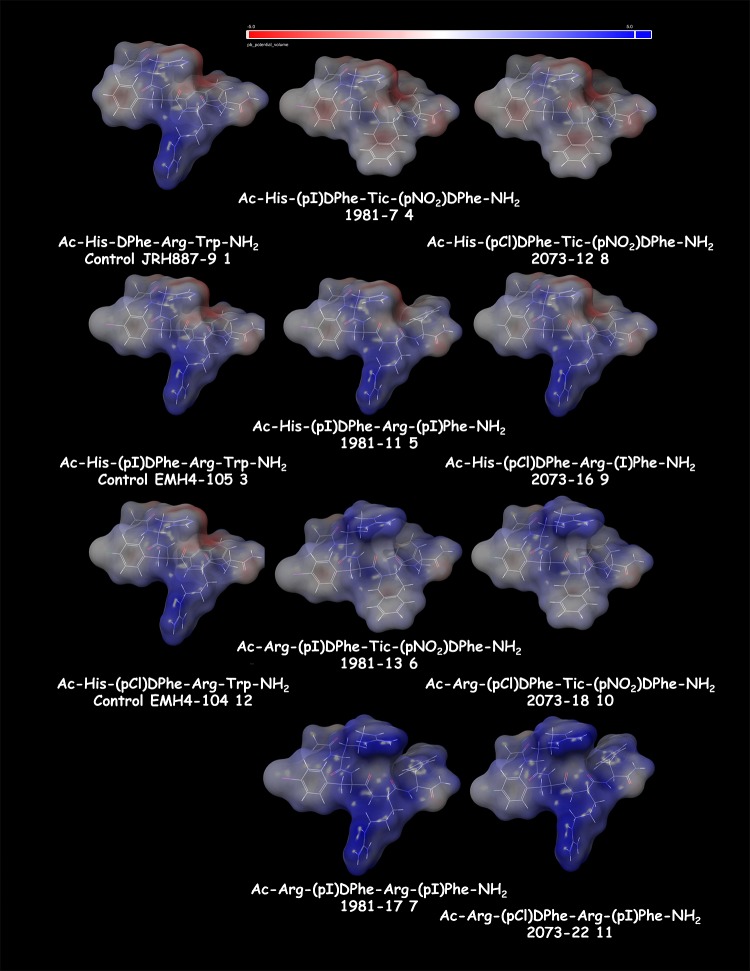

Tetrapeptide Computational Analysis of Biophysical Properties

Computational modeling studies of a previous tetrapeptide SAR study had allowed us to hypothesize differences in the ligand electrostatic surface biophysical properties as a correlation with melanocortin receptor pharmacology as opposed to differences in putative ligand–receptor interactions.21 Thus, we wanted to apply a similar approach for the tetrapeptides examined herein in attempts to identify any potential biophysical properties that might facilitate the development of a new ligand design hypothesis to explain the observed receptor pharmacology data that could be subsequently tested. Using Pipeline Pilot, the tetrapeptides were input as SMILES strings and processed as indicated in Figure 5. For the NDP–MSH, 1 and 3 control peptides, and the 36 TPI combination tetrapeptides, the following biophysical properties were calculated and summarized in the Supporting Information: ALogP, number of H acceptors, number of atoms, number of rotatable bonds, number of rings, number of aromatic rings, Log D, molecular surface area, minimized energy, and molecular 3D SASA. These properties were then individually evaluated to determine if there was any correlation with either polymorphic hMC4Rs and/or mouse melanocortin receptor subtype functional pharmacology profiles using the GraphPad Prism software. There were no observed correlations in activity with respect to molecular weight, number of H bond donors or acceptors, number of aromatic rings, molecular surface area, and 3D solvent accessible surface area. Figure 6 illustrates the electrostatic surface area for the control Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 (1), Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 (3), and Ac-His-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 (12) control tetrapeptides as well as the eight tetrapeptides (4–11) that were tested at all the polymorphic hMC4Rs and mouse MCRs examined in this study (Tables 3–6). It is relatively easy to envision how the tetrapeptide Arg amino acid side chain (shown in blue) could be putatively interacting with the key acidic melanocortin receptor resides Glu (TM2) and two Asp residues (TM3) previously postulated to form a network of ionic and potential hydrogen bonds between the ligand and receptor important for the L–R complex activation of the agonist signal transduction pathway. Remarkably however, 4 and 8, the most potent overall compounds at all the polymorphic hMC4 receptors examined herein, do not possess an Arg side chain. Thus, on the basis of the studies performed herein, it is difficult to conclude if these ligands are interacting at the receptors within the orthosteric binding pocket or at alternative allosteric receptor binding sites that may overlap, or be distinct from, the orthosteric site. Furthermore, putative ligand–receptor interactions may be either overlapping or distinct for each ligand at the different polymorphic hMC4R and mouse receptor subtypes. Additional studies, outside the scope of the current work, would need to be performed to determine the molecular mechanism for these putative ligand–melanocortin receptor molecular recognition, binding, and agonist stimulation interactions.

Figure 5.

Summary of the Pipeline Pilot experimental design modular approach that was utilized in this study.

Figure 6.

Electrostatic surface area for the control Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 (JRH887-9 1), Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 (EMH4-105 3), and Ac-His-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 (EMH4-104 12) control tetrapeptides as well as the 8 tetrapeptides (4–11) that were tested at all the polymorphic hMC4Rs and mouse MCRs examined in this study (Tables 5 and 6). The His/Arg residue at the first position is oriented at the top of the molecule, and the Arg/amino acid side chain at the third position is oriented down. The electrostatic surfaces were calculated using Maestro 9.5 (Schr̈odinger) with red (−5.0) to blue (+5.0) using the solute dielectric constant of 10 and the solvent dielectric constant of 80.

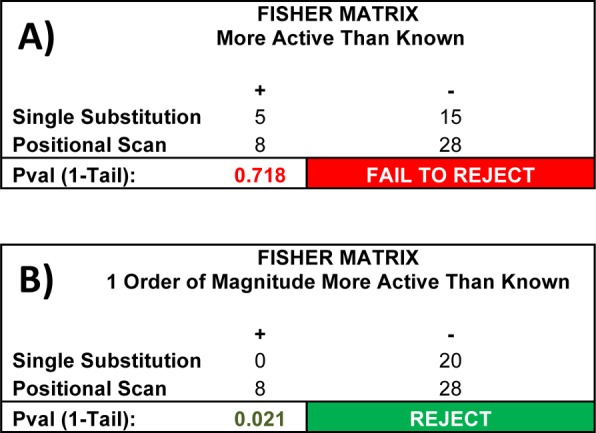

Positional Scanning Deconvolution

The results presented herein offer an excellent comparison of the usage of the data that result from screening a positional scanning combinatorial library. In particular, while the use of these data to make single-substitutions to a known ligand did result in increases in activity, no resulting ligand was >10-fold more active than the Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 (1) ligand control (Table 3). In contrast, proper deconvolution of the positional scanning library resulted in compounds representing an order of magnitude, or greater (up to 80-fold) improvement in activity. Indeed, while a 1-tail Fisher’s Exact Test categorizing ligands based on improvement in activity over Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 (1, EC50 < 215 nM) could not distinguish between the single substitution ligands and the positional scanning deconvolution ligands (p = 0.718), an analogous 1-tail Fisher’s Exact Test categorizing ligands based on an order of magnitude improvement in activity over Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 (EC50 < 21.5 nM) showed a significant positive difference in the positional scanning deconvolution of ligands over the single substitution ligands (p = 0.021), Figure 7. These results are not surprising because the individual peptides resulting from a positional scanning deconvolution are precisely those which the most active mixtures have in common and are therefore the most likely to be driving the activity in those mixtures. In contrast, a single substitution essentially implies total independence of activity between positions, which need not be the case. In fact, the resulting data clearly shows two different structural families associated with different combinations of amino acids in the third and fourth positions (Table 7); while four of the six peptides having Arg at the third and (pI)Phe in the fourth position were more active than Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2, and likewise, four of six of the peptides having Tic at the third position and (pNO2)DPhe in the fourth position, were more active than Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2, not a single positional scanning peptide tested was more active than Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 when the third and fourth position combinations were reversed (Arg in the third with (pNO2)DPhe in the fourth or Tic in the third with (pI)Phe in the fourth). This activity driven by a multipositional combination of amino acids perfectly illustrates the need for a full positional scanning deconvolution approach. It should be noted that the two potent arginine lacking peptides 4 and 8 are members of the Tic in the third position and (pNO2)DPhe in the fourth position family, perhaps further supporting the hypothesis of a different ligand–protein binding mode for these peptides as discussed in the previous section.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the single substitution (Table 3) and positional scanning deconvolution approaches (Table 4) using the L106P hMC4R pharmacological data. (A) When considering only improvements on the activity of the known ligand Ac-His- DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 (1, EC50 < 215 nM), there is no statistical difference between single substitution and positional scanning deconvolution; 5 of the 20 single substitution compounds had an EC50 < 215, comparable to the 8 of the 36 positional scanning deconvolution compounds (Fisher’s Exact Test, 1-tail, p = 0.718). (B) When considering improvements an order of magnitude or greater over the known ligand (EC50 < 21.5 nM), the difference is readily apparent and statistically significant; none of the 20 single substitution compounds had an EC50 <21.5 nM, but 8 of the 36 positional scanning deconvolution compounds did (Fisher’s Exact Test, 1-tail, p = 0.021).

Table 7. Tetrapeptide Structural Families Based on Position 3 and 4 Substitutionsa.

| peptide | sequence | L106P hMC4R agonist EC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| P3 Arg and P4 (pI)Phe | ||

| 1981-5 | Ac-Tic-(pI)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 440 ± 43 |

| 1981-11 | Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 2.9 ± 0.3 |

| 1981-17 | Ac-Arg-(pI)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 4.4 ± 0.9 |

| 2073-10 | Ac-Tic-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 380 ± 78 |

| 2073-16 | Ac-His-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 10 ± 3 |

| 2073-22 | Ac-Arg-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 13 ± 0.4 |

| P3 Tic and P4 (p NO2)DPhe | ||

| 2073-1 | Ac-Tic-(pI)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 280 ± 53 |

| 1981-7 | Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 10 ± 1.4 |

| 1981-13 | Ac-Arg-(pI)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 2.6 ± 0.3 |

| 2073-6 | Ac-Tic-(pCl)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 310 ± 50 |

| 2073-12 | Ac-His-(pCl)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 15 ± 3 |

| 2073-18 | Ac-Arg-(pCl)DPhe-Tic-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 3.4 ± 0.3 |

| P3 Arg and P4 (p NO2)DPhe | ||

| 1981-4 | Ac-Tic-(pI)DPhe-Arg-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 657 ± 70 |

| 1981-10 | Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Arg-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 293 ± 122 |

| 1981-16 | Ac-Arg-(pI)DPhe-Arg-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 655 ± 50 |

| 2073-9 | Ac-Tic-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 710 ± 240 |

| 2073-15 | Ac-His-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 3210 ± 2030 |

| 2073-21 | Ac-Arg-(pCl)DPhe-Arg-(pNO2)DPhe-NH2 | 1100 ± 320 |

| P3 Tic and P4 (pI)Phe | ||

| 1981-2 | Ac-Tic-(pI)DPhe-Tic-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 70% @ 10 μM |

| 1981-8 | Ac-His-(pI)DPhe-Tic-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 570 ± 50 |

| 1981-14 | Ac-Arg-(pI)DPhe-Tic-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 2230 ± 490 |

| 2073-7 | Ac-Tic-(pCl)DPhe-Tic-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 2670 ± 382 |

| 2073-13 | Ac-His-(pCl)DPhe-Tic-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 790 ± 290 |

| 2073-19 | Ac-Arg-(pCl)DPhe-Tic-(pI)Phe-NH2 | 215 ± 55 |

Selected peptides from positional scanning deconvolution were sorted by functionality in the 3rd and 4th positions. The indicated errors represent the standard error of the mean determined from at least three independent experiments. A % indicates that at the highest concentration tested, some stimulatory response was observed, but not the full efficacy observed for the nonreceptor dependent forskolin control.

Conclusions

The study performed herein, using a nonbiased tetrapeptide ligand discovery positional scanning library approach, has identified four tetrapeptide ligands that were able to restore full nM agonist potency to the L106P, I69T, I102S, A219V, C271Y, and C271R polymorphic hMC4Rs identified in obese human patients, expressed at the cell surface, and did not respond normally to the endogenous melanocortin receptor agonists. Two tetrapeptides that were the most potent at the polymorphic hMC4Rs examined in this study, 4 and 8 did not contain an Arg amino acid previously postulated as important for melanocortin ligand–receptor molecular recognition and agonist potency/efficacy. The results of this study have generated new SAR and pharmacophore templates for the further development of melanocortin receptor molecular probes and potential therapeutic molecules. One can also envision using the positional scanning library approach to identify ligands specific for each SNP based upon deconvolution specifically for each SNP that was screened.

Experimental Section

The TPI 924 N-acetylated C-amidated tetrapeptide positional scanning library is composed of four sublibraries in which each of the four positions are defined with a single amino acid (O) with the three remaining positions made up of a mixture of 60 different l-, d-, and unnatural amino acids (X). The 60 different amino acids are Ala, Asp, Glu, Phe, Gly, His, Ile, Lys, Leu, Met, Asn, Pro, Gln, Arg, Ser, Thr, Val, Trp, Tyr, DAla, DAsp, DGlu, DPhe, DHis, DIle, DLys, DLeu, DMet, DAsn, DPro, DGln, DArg, DSer, DThr, DVal, DTrp, DTyr, Nle, DNle, Cha, DCha, PyrAla, DPyrAla, ThiAla, DThiAla, Tic, DTic, (pCl)Phe, (pCl)DPhe, (pI)Phe, (pI)DPhe, (pNO2)Phe, (pNO2)DPhe, 2-Nal, 2-DNal, β-Ala, ε-Aminocaproic acid, Met[O2], dehydPro, and (3I)Tyr.58,59 Thus, there are 60 acetylated tetrapeptide mixtures per positional sublibrary totaling 240 acetylated tetrapeptide mixtures, each made up of 216000 acetylated tetrapeptides, with the library containing a diversity of 12960000 acetylated tetrapeptides. The 240 aceylated tetrapeptide mixtures were synthesized using the solid-phase simultaneous multiple peptide synthesis (SMPS) approach on p-methylbenzhydrylamine (MBHA) polystyrene resin.60 Mixture positions (X) were prepared using chemical mixtures of t-Boc protected amino acids, yielding close to equimolar coupling of each amino acid as previously described.61 Acetylation was achieved by treating the resin bound tetrapeptide mixtures with excess amounts of acetyl imidazole (40× excess) in dimethylformamide (0.3M) overnight. Completion of all coupling reactions, amino acid and acetylation, were monitored by ninhydrin. Side chain deprotection and cleavage from the resin support were achieved using low-HF and high-HF procedures.62,63 The 240 mixtures were individually extracted with 95% acetic acid in water, lyophilized, and resuspended three additional times using 50:50 (acetonitrile:water). The 240 mixture samples were then individually brought up in 50% DMF/water at a final concentration of 20 mg/mL. Individual acetylated tetrapeptides identified from the results of the library screening were synthesized using the SMPS approach, and the purity (>95%) and identity of each compound were confirmed by LCMS (Supporting Information).

The EMH single tetrapeptide synthesis was performed using standard 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) methodology in a CEM Discover SPS microwave peptide synthesizer.64,65 The amino acids Fmoc-His(trt), Fmoc-DPhe, Fmoc-Arg(Pbf), Fmoc-Trp(Boc), Fmoc-Tyr(tBu), Fmoc-DArg(Pbf), Fmoc-Tic (Synthetech), Fmoc-DTic (Synthetech), Fmoc-(pCl)DPhe, Fmoc-(pI)DPhe (Synthetech), Fmoc-(3I)-Tyr(tBu) (Anaspec), Fmoc-Lys(Boc), Fmoc-(pCl)Phe, Fmoc-(pNO2)DPhe, and Fmoc-Nal(1′) were purchased from Peptides International (Louisville, KY, USA) unless specified. The tetrapeptides were assembled on Rink-amide-p-methylbenzylhydrylamine (Rink-amide-MBHA, 0.37meq/g substitution, 0.3mmol scale). The resin was placed in a reaction vessel (25 mL CEM reaction vessel) and allowed to swell for 2 h to overnight in dichloromethane (DCM). All reagents were ACS grade or better. The Fmoc protecting groups were removed using 20% piperidine (Sigma-Aldrich) in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) outside the instrument for 2 min and then deprotection solution was washed away. Additional 20% piperidine/DMF solution was added to the resin and further deprotected using the following conditions: temperature = 75 °C, power = 30 W (W), time = 4 min with nitrogen bubbling the solution. After 3–5 min of a cooling down period, the reaction vessel was removed from the instrument to continue with synthesis. Amino acid coupling (3-fold excess) was accomplished using 2-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU, 3-fold excess) with a 6-fold addition of N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) and the desired amino acid (3-fold excess) dissolved in minimum DMF (DCM was not used in microwave synthesis). The microwave synthesizer conditions for amino acid coupling conditions varied for cysteine and histidine (50 °C, 30W, 5 min), arginine (75 °C, 30 W, 10 min), and for all the other amino acids used (75 °C, 30W, 5 min). After a 3–5 min cool down period, the resin was washed and the method of deprotection and coupling was repeated until the desired chain was synthesized.

After each amino acid coupling and Fmoc deprotection step, the peptide sequence was monitored using the Kaiser/ninhydrin test.66 All peptides were N-terminally acetylated with a 3:1 mixture of acetic anhydride and pyridine that bubbled with the resin bound peptide for 30–45 min. Final peptide cleavage from the resin and amino acid side chain protecting group removal was performed using 95% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), 2.5% triisopropylsilane (TIS), and 2.5% water for 2–3 h at room temperature. After cleavage and side chain deprotection, the solution was concentrated and the peptide was precipitated and washed using cold (4 °C), anhydrous diethyl ether. Ligands were purified by reverse phase-high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) using a Shimadzu chromatography system with a photodiode array detector and a semipreparative RP-HPLC C18 bonded silica column (Vydac 218TP1010, 1.0 cm × 25 cm) and lyophilized. The purified peptides were analyzed using RP-HPLC with an analytical Vydac C18 column (Vydac 218TP104). The purified peptides were at least >95% pure as determined by RP-HPLC in two diverse solvent systems (10% acetonitrile in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid/water and a gradient to 90% acetonitrile over 35 min or 10% methanol in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid/water and a gradient to 90% methanol over 35 min). Molecular mass was determined by mass spectrometry (Voyager-DE Pro, University of Florida Protein Core Facility), see Supporting Information.

Bioassay

cAMP Based Functional Bioassay

Peptide ligands were dissolved in DMSO at a stock concentration of 10–2 M and stored at −20 °C until assayed. HEK-293 cells stably expressing the mutant and wild-type melanocortin receptors were transiently transfected with 4 μg of CRE/β-galactosidase reporter gene as previously described.13,19,42,67 Briefly, 5000–15000 post transfection cells were plated into collagen treated 96-well plates (Nunc) and incubated overnight. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, the cells were stimulated with 50 μL of peptide (10–5–10–12 M for single tetrapeptides in dose–response or ca. 100 μg/mL for screening) or forskolin (10–4 M) control in assay medium (DMEM containing 0.1 mg/mL BSA and 0.1 mM isobutylmethylxanthine) for 6 h. [For screening, each plate was visually inspected under a microscope to determine if cells were healthy or had been killed during the compound stimulation process. All the cells were observed to be normal and healthy after the 6 h stimulation in the screening assays involving the TPI 924 library.] The assay media was aspirated, and 50 μL of lysis buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl pH = 8.0 and 0.1% Triton X-100) was added. The plates were stored at −80 °C overnight. The plates containing the cell lysates were thawed the following day. Aliquots of 10 μL were taken from each well and transferred to another 96-well plate for relative protein determination. To the cell lysate plates, 40 μL of phosphate-buffered saline with 0.5% BSA was added to each well. Subsequently, 150 μL of substrate buffer (60 mM sodium phosphate, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mg/mL ONPG) was added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37 °C. The sample absorbance, OD405, was measured using a 96-well plate reader (Molecular Devices). The relative protein was determined by adding 200 μL of 1:5 dilution Bio Rad G250 protein dye:water to the 10 μL of cell lysate sample taken previously, and the OD595 was measured on a 96-well plate reader (Molecular Devices). Data points were normalized to forskolin and the relative protein content. The EC50 values represent the mean of three or more independent experiments. The EC50 estimates, and their associated standard errors of the mean, were determined by fitting the data to a nonlinear least-squares analysis using the PRISM program (v4.0, GraphPad Inc.).

Ligand Biophysical Computational Analysis

Pipeline Pilot 8.5 was used to calculate a series of biophysical properties on the tetrapeptides examined in this study. These calculated values were used to probe the structure–activity relationship. A protocol developed in Pipeline Pilot allowed for the importation of molecular data, calculation of the biophysical properties, and output into an Excel format (Figure 5). The protocol started with the importation of the tetrapeptide SMILES from an Excel file. From this, Pipeline Pilot converted the SMILES into a 2D molecular representation. The ligand preparation component ionized each of the peptides to a pH of 7.4, fixed bad valencies, and generated a 3D structure. The next three components calculated ALogP, molecular weight, number of H bond donors and acceptors, number of rotatable bonds, number of rings and aromatic rings, Log D at pH 7.4, and molecular surface area. Following these calculations, 3D coordinates were assigned to each peptide. The energy was then minimized using a maximum number of 1000 steps and a convergence energy difference of 0.0001, and the 3D coordinates were then updated. The surface area and volume component then calculated the molecular 3D solvent accessible surface area. All of the calculated properties were then assembled into an Excel file and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 4. The measured functional activity for each of the peptides was plotted as a −Log10(EC50) value with respect to the above-described biophysical properties.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported in part by the Minnesota Supercomputing Insititute and NIH grants RO1DK064250 (C.H.L.), R01DK091906 (C.H.L.), and RO1DA031370 (R.A.H.), and the State of Florida, Executive Office of the Governor’s Office of Tourism, Trade, and Economic Development (R.A.H.).

Supporting Information Available

Pipeline Pilot biophysical properties and analytical information for the single tetrapeptides synthesized and characterized in this study. Purity for these compounds is >95%. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Chhajlani V.; Wikberg J. E. S. Molecular Cloning and Expression of the Human Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone Receptor cDNA. FEBS Lett. 1992, 3093417–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountjoy K. G.; Robbins L. S.; Mortrud M. T.; Cone R. D. The Cloning of a Family of Genes that Encode the Melanocortin Receptors. Science 1992, 257, 1248–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli-Rehfuss L.; Mountjoy K. G.; Robbins L. S.; Mortrud M. T.; Low M. J.; Tatro J. B.; Entwistle M. L.; Simerly R. B.; Cone R. D. Identification of a Receptor for g Melanotropin and Other Proopiomelanocortin Peptides in the Hypothalamus and Limbic System. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993, 90, 8856–8860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountjoy K. G.; Mortrud M. T.; Low M. J.; Simerly R. B.; Cone R. D. Localization of the Melanocortin-4 Receptor (MC4-R) in Neuroendocrine and Autonomic Control Circuits in the Brain. Mol. Endocrinol. 1994, 8, 1298–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantz I.; Konda Y.; Tashiro T.; Shimoto Y.; Miwa H.; Munzert G.; Watson S. J.; DelValle J.; Yamada T. Molecular Cloning of a Novel Melanocortin Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268118246–8250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantz I.; Miwa H.; Konda Y.; Shimoto Y.; Tashiro T.; Watson S. J.; DelValle J.; Yamada T. Molecular Cloning, Expression, and Gene Localization of a Fourth Melanocortin Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 2682015174–15179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantz I.; Shimoto Y.; Konda Y.; Miwa H.; Dickinson C. J.; Yamada T. Molecular Cloning, Expression, and Characterization of a Fifth Melanocortin Receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994, 20031214–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eipper B. A.; Mains R. E. Structure and Biosynthesis of Pro-ACTH/Endorphin and Related Peptides. Endocrinol. Rev. 1980, 1, 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. I.; Funder J. W. Proopiomelanocortin Processing in the Pituitary, Central Nervous System and Peripheral Tissues. Endocr. Rev. 1988, 9, 159–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard L. E.; Turnbull A. V.; White A. Pro-opiomelanocortin Processing in the Hypothalamus: Impact on Melanocortin Signalling and Obesity. J. Endocrinol. 2002, 1723411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willer C. J.; Speliotes E. K.; Loos R. J.; Li S.; Lindgren C. M.; Heid I. M.; Berndt S. I.; Elliott A. L.; Jackson A. U.; Lamina C.; Lettre G.; Lim N.; Lyon H. N.; McCarroll S. A.; Papadakis K.; Qi L.; Randall J. C.; Roccasecca R. M.; Sanna S.; Scheet P.; Weedon M. N.; Wheeler E.; Zhao J. H.; Jacobs L. C.; Prokopenko I.; Soranzo N.; Tanaka T.; Timpson N. J.; Almgren P.; Bennett A.; Bergman R. N.; Bingham S. A.; Bonnycastle L. L.; Brown M.; Burtt N. P.; Chines P.; Coin L.; Collins F. S.; Connell J. M.; Cooper C.; Smith G. D.; Dennison E. M.; Deodhar P.; Elliott P.; Erdos M. R.; Estrada K.; Evans D. M.; Gianniny L.; Gieger C.; Gillson C. J.; Guiducci C.; Hackett R.; Hadley D.; Hall A. S.; Havulinna A. S.; Hebebrand J.; Hofman A.; Isomaa B.; Jacobs K. B.; Johnson T.; Jousilahti P.; Jovanovic Z.; Khaw K. T.; Kraft P.; Kuokkanen M.; Kuusisto J.; Laitinen J.; Lakatta E. G.; Luan J.; Luben R. N.; Mangino M.; McArdle W. L.; Meitinger T.; Mulas A.; Munroe P. B.; Narisu N.; Ness A. R.; Northstone K.; O’Rahilly S.; Purmann C.; Rees M. G.; Ridderstrale M.; Ring S. M.; Rivadeneira F.; Ruokonen A.; Sandhu M. S.; Saramies J.; Scott L. J.; Scuteri A.; Silander K.; Sims M. A.; Song K.; Stephens J.; Stevens S.; Stringham H. M.; Tung Y. C.; Valle T. T.; Van Duijn C. M.; Vimaleswaran K. S.; Vollenweider P.; Waeber G.; Wallace C.; Watanabe R. M.; Waterworth D. M.; Watkins N.; Witteman J. C.; Zeggini E.; Zhai G.; Zillikens M. C.; Altshuler D.; Caulfield M. J.; Chanock S. J.; Farooqi I. S.; Ferrucci L.; Guralnik J. M.; Hattersley A. T.; Hu F. B.; Jarvelin M. R.; Laakso M.; Mooser V.; Ong K. K.; Ouwehand W. H.; Salomaa V.; Samani N. J.; Spector T. D.; Tuomi T.; Tuomilehto J.; Uda M.; Uitterlinden A. G.; Wareham N. J.; Deloukas P.; Frayling T. M.; Groop L. C.; Hayes R. B.; Hunter D. J.; Mohlke K. L.; Peltonen L.; Schlessinger D.; Strachan D. P.; Wichmann H. E.; McCarthy M. I.; Boehnke M.; Barroso I.; Abecasis G. R.; Hirschhorn J. N. Six New Loci Associated with Body Mass Index Highlight a Neuronal Influence on Body Weight Regulation. Nature Genet. 2009, 41125–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorleifsson G.; Walters G. B.; Gudbjartsson D. F.; Steinthorsdottir V.; Sulem P.; Helgadottir A.; Styrkarsdottir U.; Gretarsdottir S.; Thorlacius S.; Jonsdottir I.; Jonsdottir T.; Olafsdottir E. J.; Olafsdottir G. H.; Jonsson T.; Jonsson F.; Borch-Johnsen K.; Hansen T.; Andersen G.; Jorgensen T.; Lauritzen T.; Aben K. K.; Verbeek A. L.; Roeleveld N.; Kampman E.; Yanek L. R.; Becker L. C.; Tryggvadottir L.; Rafnar T.; Becker D. M.; Gulcher J.; Kiemeney L. A.; Pedersen O.; Kong A.; Thorsteinsdottir U.; Stefansson K. Genome-Wide Association Yields New Sequence Variants at Seven Loci that Associate with Measures of Obesity. Nature Genet. 2009, 41118–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Z.; Pogozheva I. D.; Sorenson N. B.; Wilczynski A. M.; Holder J. R.; Litherland S. A.; Millard W. J.; Mosberg H. I.; Haskell-Luevano C. Peptide and Small Molecules Rescue the Functional Activity and Agonist Potency of Dysfunctional Human Melanocortin-4 Receptor Polymorphisms. Biochemistry 2007, 46288273–8287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghten R. A.; Pinilla C.; Giulianotti M. A.; Appel J. R.; Dooley C. T.; Nefzi A.; Ostresh J. M.; Yu Y.; Maggiora G. M.; Medina-Franco J. L.; Brunner D.; Schneider J. Strategies for the Use of Mixture-Based Synthetic Combinatorial Libraries: Scaffold Ranking, Direct Testing in Vivo, and Enhanced Deconvolution by Computational Methods. J. Comb. Chem. 2008, 1013–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley C. T.; Ny P.; Bidlack J. M.; Houghten R. A. Selective Ligands for the Mu, Delta, and Kappa Opioid Receptors Identified from a Single Mixture Based Tetrapeptide Positional Scanning Combinatorial Library. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 2733018848–18856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinilla C.; Edwards B. S.; Appel J. R.; Yates-Gibbins T.; Giulianotti M. A.; Medina-Franco J. L.; Young S. M.; Santos R. G.; Sklar L. A.; Houghten R. A. Selective Agonists and Antagonists of Formylpeptide Receptors: Duplex Flow Cytometry and Mixture-Based Positional Scanning Libraries. Mol. Pharmacol. 2013, 843314–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqi I. S.; Keogh J. M.; Yeo G. S.; Lank E. J.; Cheetham T.; O’Rahilly S. Clinical Spectrum of Obesity and Mutations in the Melanocortin 4 Receptor Gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348121085–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo G. S.; Lank E. J.; Farooqi I. S.; Keogh J.; Challis B. G.; O’Rahilly S. Mutations in the Human Melanocortin-4 Receptor Gene Associated with Severe Familial Obesity Disrupts Receptor Function Through Multiple Molecular Mechanisms. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003, 125561–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Z.; Litherland S. A.; Sorensen N. B.; Proneth B.; Wood M. S.; Shaw A. M.; Millard W. J.; Haskell-Luevano C. Pharmacological Characterization of 40 Human Melanocortin-4 Receptor Polymorphisms with the Endogenous Proopiomelanocortin-Derived Agonists and the Agouti-Related Protein (AGRP) Antagonist. Biochemistry 2006, 45237277–7288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder J. R.; Bauzo R. M.; Xiang Z.; Haskell-Luevano C. Structure–Activity Relationships of the Melanocortin Tetrapeptide Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 at the Mouse Melanocortin Receptors: Part 2 Modifications at the Phe Position. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 3073–3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proneth B.; Pogozheva I. D.; Portillo F. P.; Mosberg H. I.; Haskell-Luevano C. Melanocortin Tetrapeptide Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 Modified at the Para Position of the Benzyl Side Chain (DPhe): Importance for Mouse Melanocortin-3 Receptor Agonist Versus Antagonist Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51185585–5593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Z.; Proneth B.; Dirain M. L.; Litherland S. A.; Haskell-Luevano C. Pharmacological Characterization of 30 Human Melanocortin-4 Receptor Polymorphisms with Endogenous Proopiomelanocortin Derived Agonists, Synthetic Agonists, and the Endogenous Agouti-Related Protein (AGRP) Antagonist. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 4583–4600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder J. R.; Bauzo R. M.; Xiang Z.; Haskell-Luevano C. Structure–Activity Relationships of the Melanocortin Tetrapeptide Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 at the Mouse Melanocortin Receptors: I. Modifications at the His Position. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2801–2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder J. R.; Xiang Z.; Bauzo R. M.; Haskell-Luevano C. Structure–Activity Relationships of the Melanocortin Tetrapeptide Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 at the Mouse Melanocortin Receptors: Part 4. Modifications at the Trp Position. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 5736–5744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder J. R.; Xiang Z.; Bauzo R. M.; Haskell-Luevano C. Structure–Activity Relationships of the Melanocortin Tetrapeptide Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 at the Mouse Melanocortin Receptors: Part 3. Modifications at the Arg Position. Peptides 2003, 24, 73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irani B. G.; Xiang Z.; Yarandi H. N.; Holder J. R.; Moore M. C.; Bauzo R. M.; Proneth B.; Shaw A. M.; Millard W. J.; Chambers J. B.; Benoit S. C.; Clegg D. J.; Haskell-Luevano C. Implication of the Melanocortin-3 Receptor in the Regulation of Food Intake. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 660180–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K.; Pogozheva I. D.; Yeo G. S.; Hadaschik D.; Keogh J. M.; Haskell-Luevano C.; O’Rahilly S.; Mosberg H. I.; Farooqi I. S. Functional Characterization and Structural Modeling of Obesity Associated Mutations in the Melanocortin 4 Receptor. Endocrinology 2009, 1501114–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubern B.; Clement K.; Pelloux V.; Froguel P.; Girardet J. P.; Guy-Grand B.; Tounian P. Mutational Analysis of Melanocortin-4 Receptor, Agouti-Related Protein, and a-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone Genes in Severely Obese Children. J. Pediatr. 2001, 1392204–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubrano-Berthelier C.; Durand E.; Dubern B.; Shapiro A.; Dazin P.; Weill J.; Ferron C.; Froguel P.; Vaisse C. Intracellular Retention is a Common Characteristic of Childhood Obesity-Associated MC4R Mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003, 122145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y. X.; Segaloff D. L. Functional Analyses of Melanocortin-4 Receptor Mutations Identified from Patients with Binge Eating Disorder and Nonobese or Obese Subjects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 90105632–5638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen L. H.; Echwald S. M.; Sorensen T. I.; Andersen T.; Wulff B. S.; Pedersen O. Prevalence of Mutations and Functional Analyses of Melanocortin 4 Receptor Variants Identified Among 750 men with Juvenile-Onset Obesity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 901219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqi I. S.; Yeo G. S.; Keogh J. M.; Aminian S.; Jebb S. A.; Butler G.; Cheetham T.; O’Rahilly S. Dominant and Recessive Inheritance of Morbid Obesity Associated with Melanocortin 4 Receptor Deficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 2000, 1062271–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y. X.; Segaloff D. L. Functional Characterization of Melanocortin-4 Receptor Mutations Associated with Childhood Obesity. Endocrinology 2003, 144104544–4551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atalayer D.; Robertson K. L.; Haskell-Luevano C.; Andreasen A.; Rowland N. E. Food Demand and Meal Size in Mice with Single or Combined Disruption of Melanocortin Type 3 and 4 Receptors. Am. J. Physiol.: Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2010, 2986R1667–R1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland N. E.; Fakhar K. J.; Robertson K. L.; Haskell-Luevano C. Effect of Serotonergic Anorectics on Food Intake and Induction of Fos in Brain of Mice with Disruption of Melanocortin 3 and/or 4 Receptors. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 2010, 97, 107–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland N. E.; Schaub J. W.; Robertson K. L.; Andreasen A.; Haskell-Luevano C. Effect of MTII on Food Intake and Brain c-Fos in Melanocortin-3, Melanocortin-4, and Double MC3 and MC4 Receptor Knockout Mice. Peptides 2010, 31122314–2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan C. H.; Moore M. C.; Haskell-Luevano C.; Rowland N. E. Meal Patterns and Foraging in Melanocortin Receptor Knockout Mice. Physiol. Behav. 2005, 841129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan C. H.; Haskell-Luevano C.; Andreasen A.; Rowland N. E. Effects of Oral Preload, CCK or Bombesin Administration on Short Term Food Intake of Melanocortin 4-Receptor Knockout (MC4RKO) Mice. Peptides 2006, 27123226–3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan C.; Moore M.; Haskell-Luevano C.; Rowland N. E. Food Motivated Behavior of Melanocortin-4 Receptor Knockout Mice Under a Progressive Ratio Schedule. Peptides 2006, 27112829–2835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruby V. J.; Lu D.; Sharma S. D.; Castrucci A. M. L.; Kesterson R. A.; Al-Obeidi F. A.; Hadley M. E.; Cone R. D. Cyclic Lactam a-Melanotropin Analogues of Ac-Nle4-c[Asp5, DPhe7, Lys10]-a-MSH(4–10)-NH2 With Bulky Aromatic Amino Acids at Position 7 Show High Antagonist Potency and Selectivity at Specific Melanocortin Receptors. J. Med. Chem. 1995, 38, 3454–3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynski A.; Wilson K. R.; Scott J. W.; Edison A. S.; Haskell-Luevano C. Structure–Activity Relationships of the Unique and Potent Agouti-Related Protein (AGRP)-Melanocortin Chimeric Tyr-c[β-Asp-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-Asn-Ala-Phe-Dpr]-Tyr-NH2 Peptide Template. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 4883060–3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskell-Luevano C.; Cone R. D.; Monck E. K.; Wan Y.-P. Structure–Activity Studies of the Melanocortin-4 Receptor by in Vitro Mutagenesis: Identification of Agouti-Related Protein (AGRP), Melanocortin Agonist and Synthetic Peptide Antagonist Interaction Determinants. Biochemistry 2001, 40206164–6179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai B. X.; Pogozheva I. D.; Lai Y. M.; Li J. Y.; Neubig R. R.; Mosberg H. I.; Gantz I. Receptor–Antagonist Interactions in the Complexes of Agouti and Agouti-Related Protein with Human Melanocortin 1 and 4 Receptors. Biochemistry 2005, 4493418–3431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.; Aprahamian C. J.; Celik A.; Georgeson K. E.; Garvey W. T.; Harmon C. M.; Yang Y. Molecular Characterization of Human Melanocortin-3 Receptor Ligand–Receptor Interaction. Biochemistry 2006, 4541128–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan K.; Peluso S.; Gould S.; Parsons I.; Ryan D.; Wu L.; Visiers I. Mapping the Binding Site of Melanocortin 4 Receptor Agonists: a Hydrophobic Pocket Formed by I3.28(125), I3.32(129), and I7.42(291) is Critical for Receptor Activation. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 493911–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.-K.; Dickinson C.; Haskell-Luevano C.; Gantz I. Molecular Basis for the Interaction of [Nle4, DPhe7] Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone with the Human Melanocortin-1 Receptor (Melanocyte a-MSH Receptor). J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 23000–23010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Fong T. M.; Dickinson C. J.; Mao C.; Li J. Y.; Tota M. R.; Mosley R.; Van Der Ploeg L. H.; Gantz I. Molecular Determinants of Ligand Binding to the Human Melanocortin-4 Receptor. Biochemistry 2000, 394814900–14911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek M. A.; MacNeil T.; Kalyani R. N.; Tang R.; Van der Ploeg L. H.; Weinberg D. H. Analogs of MTII, Lactam Derivatives of a-Melanotropin, Modified at the N-terminus, and their Selectivity at Human Melanocortin Receptors 3, 4, and 5. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 2611209–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek M. A.; MacNeil T.; Kalyani R. N.; Tang R.; Van der Ploeg L. H.; Weinberg D. H. Analogs of Lactam Derivatives of a-melanotropin with Basic and Acidic Residues. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 272123–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek M. A.; Silva M. V.; Arison B.; MacNeil T.; Kalyani R. N.; Huang R. R.; Weinberg D. H. Structure–Function Studies on the Cyclic Peptide MT-II, Lactam Derivative of a-melanotropin. Peptides 1999, 203401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco P.; Balse P. M.; Weinberg D.; MacNeil T.; Hruby V. J. d-Amino Acid Scan of γ-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone: Importance of Trp(8) on Human MC3 Receptor Selectivity. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43264998–5002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco P.; Balse-Srinivasan P.; Han G.; Hruby V. J.; Weinberg D.; MacNeil T.; Van Der Ploeg L. H. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation on hMC3, hMC4 and hMC5 Receptors of g-MSH Analogs Substituted with L-Alanine. J. Pept. Res. 2002, 595203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahm U. G.; Olivier G. W. J.; Branch S. K.; Moss S. H.; Pouton C. W. Influence of a-MSH Terminal Amino Acids on Binding Affinity and Biological Activity in Melanoma Cells. Peptides 1994, 15, 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Obeidi F.; Castrucci A. M.; Hadley M. E.; Hruby V. J. Potent and Prolonged Acting Cyclic Lactam Analogues of a-Melanotropin: Design Based on Molecular Dynamics. J. Med. Chem. 1989, 32, 2555–2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung A.; Danho W.; Swistok J.; Qi L.; Kurylko G.; Franco L.; Yagaloff K.; Chen L. Structure–Activity Relationship of Linear Peptide Bu-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-Gly-NH(2) at the Human Melanocortin-1 and -4 Receptors: Arginine Substitution. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002, 12172407–2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schioth H. B.; Mutulis F.; Muceniece R.; Prusis P.; Wikberg J. E. Discovery of Novel Melanocortin-4 receptor Selective MSH Analogues. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998, 124175–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph C. G.; Sorensen N. B.; Wood M. S.; Xiang Z.; Moore M. C.; Haskell-Luevano C. Modified Melanocortin Tetrapeptide Ac-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2 at the Arginine Side Chain with Ureas and Thioureas. J. Pept. Res. 2005, 665297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinilla C.; Appel J. R.; Blanc P.; Houghten R. A. Rapid Identification of High Affinity Peptide Ligands using Positional Scanning Synthetic Peptide Combinatorial Libraries. Biotechniques 1992, 136901–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley C. T.; Houghten R. A. The Use of Positional Scanning Synthetic Peptide Combinatorial Libraries for the Rapid Determination of Opioid Receptor Ligands. Life Sci. 1993, 52181509–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghten R. A. General Method for the Rapid Solid-Phase Synthesis of Large Numbers of Peptides: Specificity of Antigen–Antibody Interaction at the Level of Individual Amino Acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1985, 82155131–5135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostresh J. M.; Winkle J. H.; Hamashin V. T.; Houghten R. A. Peptide Libraries: Determination of Relative Reaction Rates of Protected Amino Acids in Competitive Couplings. Biopolymers 1994, 34121681–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam J. P.; Heath W. F.; Merrifield R. B. An SN2 Deprotection of Synthetic Peptides with a Low Concentration of Hydrofluoric Acid in Dimethyl Sulfide: Evidence and Application in Peptide Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105216442–6455. [Google Scholar]

- Houghten R. A.; Bray M. K.; Degraw S. T.; Kirby C. J. Simplified Procedure for Carrying Out Simultaneous Multiple Hydrogen Fluoride Cleavages of Protected Peptide Resins. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1986, 276673–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpino L. A.; Han G. Y. The 9-Fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl Function, a New Base-Sensitive Amino-Protecting Group. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92195748–5749. [Google Scholar]

- Singh A.; Wilczynski A.; Holder J. R.; Witek R. M.; Dirain M. L.; Xiang Z.; Edison A. S.; Haskell-Luevano C. Incorporation of a Bioactive Reverse-Turn Heterocycle into a Peptide Template Using Solid-Phase Synthesis To Probe Melanocortin Receptor Selectivity and Ligand Conformations by 2D (1)H NMR. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 5451379–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser E.; Colescott R. L.; Bossinger C. D.; Cook P. I. Color Test for Detection of Free Terminal Amino Groups in the Solid-Phase Synthesis of Peptides. Anal. Biochem. 1970, 34, 595–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Shields T. S.; Stork P. J. S.; Cone R. D. A Colorimetric Assay for Measuring Activation of Gs- and Gq-Coupled Signaling Pathways. Anal. Biochem. 1995, 226, 349–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.