Abstract

During the past century, diverse studies have focused on the development of surgical strategies to restore function of a decentralized bladder after spinal cord or spinal root injury via repair of the original roots or by transferring new axonal sources. The techniques included end-to-end sacral root repairs, transfer of roots from other spinal segments to sacral roots, transfer of intercostal nerves to sacral roots, transfer of various somatic nerves to the pelvic or pudendal nerve, direct reinnervation of the detrusor muscle, or creation of an artificial reflex pathway between the skin and the bladder via the central nervous system. All of these surgical techniques have demonstrated specific strengths and limitations. The findings made to date already indicate appropriate patient populations for each procedure, but a comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of each technique to restore urinary function after bladder decentralization is required to guide future research and potential clinical application.

Introduction

Lower urinary tract dysfunction can occur after severe spinal cord injury (SCI), sacral root injury as occurs with cauda equina syndrome, or traumatic injury to the pelvic plexus as can occur with hip or pelvic fracture. Such injuries can disrupt the urinary bladder’s main functions of storing urine (urinary continence) and emptying (micturition). Survey studies demonstrate that urological problems due to neurogenic bladder dysfunction (NBD) after SCI have a high prevalence and long-term consequences for the wellbeing of these patients, such as detrusor muscle hyperactivity and detrusor–external sphincter dyssynergia,1–4 resulting in impairment of urine storage and voiding. The current management of these urologic problems can entail simple techniques, such as the Credé manoeuvre, intermittent bladder catheterization, and pharmacological management.5 Other surgical management methods include sacral rhizotomy to decrease detrusor muscle contractions, sphincterotomy or pudendal nerve section to decrease sphincter tone,4 and vesicostomy to maintain an empty bladder.6 Each technique is intended to improve the efficiency of bladder emptying as well as decrease the risk of secondary urinary tract infections (UTIs) and damage to the upper urinary tract that could threaten the patient’s life.

In patients with spinal cord and cauda equina injuries, the public focus has generally centred on the need to regain the ability to stand and walk. However, in a survey study performed in 2004, restoration of bladder function was rated by patients as having greater importance, listed as the second priority after sexual function in paraplegic patients, and as the third priority after hand function and sexual function in quadriplegic patients.1 Regaining bladder continence not only aids reintegration into the community, but also helps to prevent clinical complications, because it enables low-pressure storage and efficient bladder emptying at low detrusor pressure, avoids stretch injury to the bladder from repeated overdistension, and prevents hydronephrosis.7 Loss of one or more of these functions is the major urological complication in patients with NBD that is caused by upper or lower motor neuron lesions in the spinal cord.8–14 Before 1977, epidemiological studies identified renal disease as a complication of lower urinary tract dysfunction as the major cause of death in patients with SCI.8, 9 Although the level of morbidity from urinary tract related complications has been considerably reduced, owing to modern techniques as described above, patient quality of life remains remarkably low However, patient wellbeing could be markedly improved if restoration of urinary bladder function were accomplished. Thus, effective methods for improved management of the NBD and restoration of urinary functions after SCI are needed.

Restoration of urinary bladder control using surgical methods of reinnervation was first attempted more than 100 years ago in dog models by suturing the proximal end of lower extremity nerves to the distal end of the nerves innervating the bladder and rectum.15–17 Although these original experiments were not completely successful, variations of this strategy have been used numerous times in animal models and in patients, with variable success. In the past three decades, several reports of successful nerve transfer methods in animal models and patients for restoration of bladder function have been published.15–47 This Review describes the different nerve transfer strategies performed in the past century, discusses their strengths and limitations, and defines the optimal target populations for each procedure, when possible.

Bladder innervation

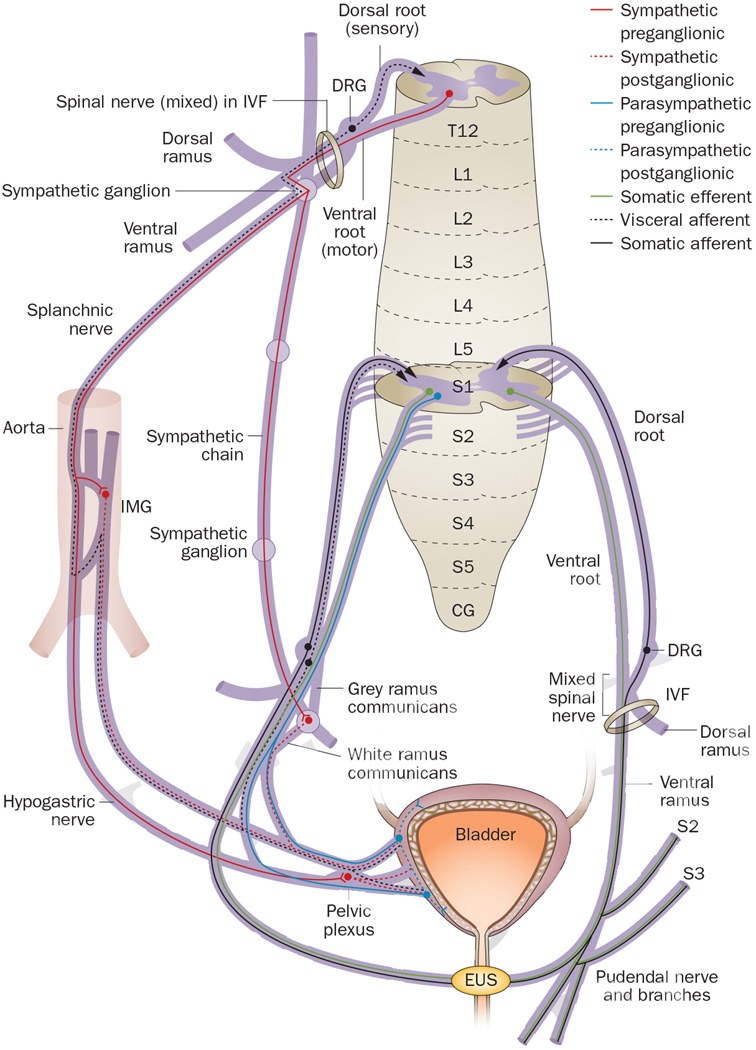

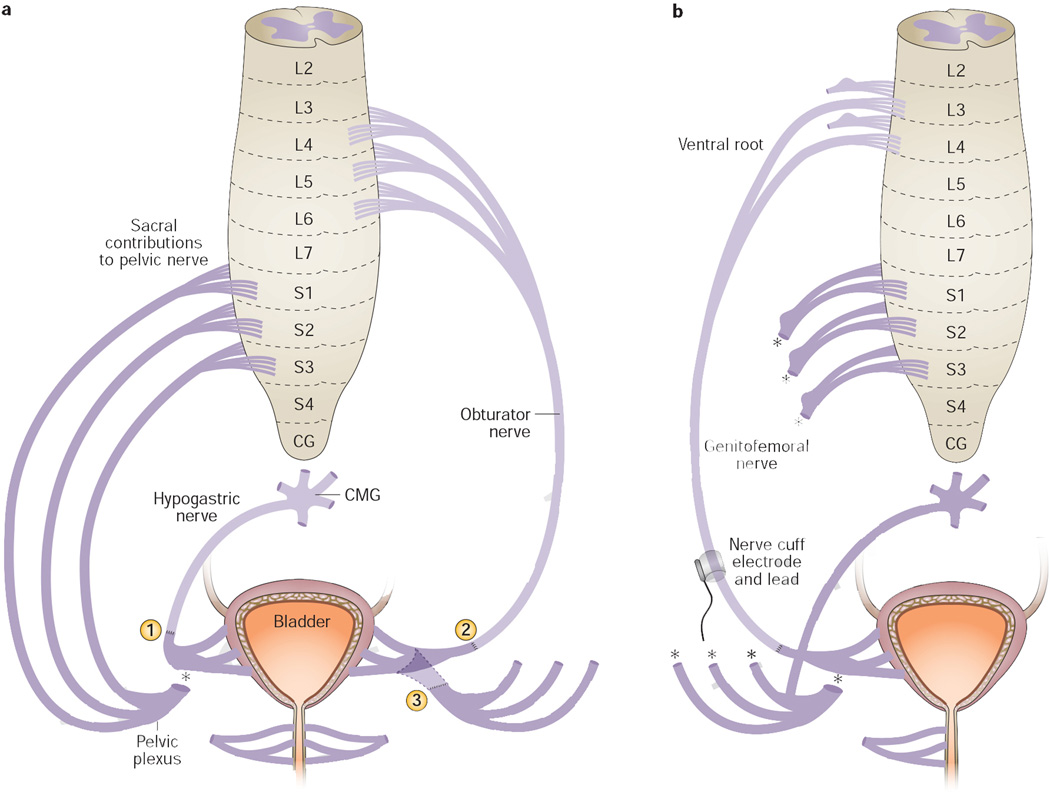

In this Review, the classic terminology for spinal cord neuroanatomy is used and matched to terms used in the cited publications. Of note, the term ‘roots’ does not refer to the mixed spinal nerve origins of brachial plexus trunks, but instead refers to dorsal spinal roots, which carry sensory axons only, and ventral spinal roots, which carry motor axons only. Sensory dorsal roots enter the dorsal root entry zone of the spinal cord and motor ventral roots exit the ventral root entry zone of the spinal cord (Figure 1). The dorsal and ventral roots then join into a mixed spinal nerve (also called radicular nerves), which is located within the intervertebral foramen. After exiting the intervertebral foramen, the spinal nerve immediately divides into four parts: a dorsal ramus which carries axons that innervate dorsal somatic structures, for example, back muscles and skin; a ventral ramus which carries axons that innervate ventral somatic structures, for example, trunk and leg musculature and skin, and the external urethral sphincter (EUS); connections to sympathetic ganglia from spinal nerves located in thoracic and lumbar regions (via the gray and white rami communicantes); splanchnic nerves in thoracolumbar and sacral regions that carry preganglionic sympathetic or parasympathetic axons, respectively, to ganglia located on the abdominal aorta or on or near the end organs. In these latter ganglia, preganglionic axons synapse on postganglionic neuronal cell bodies. Sympathetic bladder innervation consists of preganglionic axons that project from thoracic level 10 (T10) to lumbar level 2 (L2) spinal cord segments through splanchnic nerves to the inferior mesenteric ganglion on the aorta (Figure 1). Within these ganglia, axons synapse on postganglionic neurons that then project axons to the bladder on one or more nerve branches that are collectively termed the hypogastric nerve. Other preganglionic sympathetic axons descend within the sympathetic chain to upper sacral ganglia, where they synapse on neurons that project axons to the bladder. Parasympathetic innervation of the bladder via pelvic splanchnic nerves consists of preganglionic axon projections from upper sacral spinal cord segments (S2–S4 in most mammalian species) to ganglia located near the bladder wall. The exact sacral segments from which parasympathetic innervation arises vary between mammalian species. Visceral and somatic structures send sensory feedback to the spinal cord. These sensory afferents ‘hitchhike’ on the various autonomic and somatic motor nerves innervating end organs. From the bladder, sensory afferents project back to both thoracic and sacral spinal cord regions, as well as to lumbar spinal cord regions.48, 49 Lastly, the pelvic plexus comprises parasympathetic and sympathetic motor nerve branches to the bladder, and visceral sensory nerve branches from the bladder to the spinal cord (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Spinal cord neuroanatomy and bladder innervation in humans and other mammals. After exiting the spinal cord, dorsal and ventral roots (which consist of small rootlets that unite to form the large root) join into a mixed spinal nerve that divides into a dorsal ramus, a ventral ramus, the sympathetic chain, and splanchnic nerves. The bladder is innervated via sympathetic axons that project from T10 to L2 (only T12 contributions are illustrated) through either splanchnic nerves to the inferior mesenteric ganglion on the aorta or descend within the sympathetic chain to upper sacral ganglia, where they synapse on neurons that project to the bladder. Parasympathetic bladder innervation from pelvic splanchnic nerves consists of preganglionic axon projections from S2 to S4 (only S2 contributions are illustrated) in most mammalian species to ganglia located near the bladder wall. Sensory feedback travels to the spinal cord from visceral and somatic structures by ‘hitchhiking’ on autonomic and somatic motor nerves. Abbreviations: CG, coccygeal segment; DRG, dorsal root ganglion; EUS, external urethral sphincter; IMG, inferior or caudal mesenteric ganglion; IVF, intervertebral foramen; L, lumbar; S, sacral; T, thoracic.

Strategies for bladder reinnervation

Sacral root repair

Homotopic repair

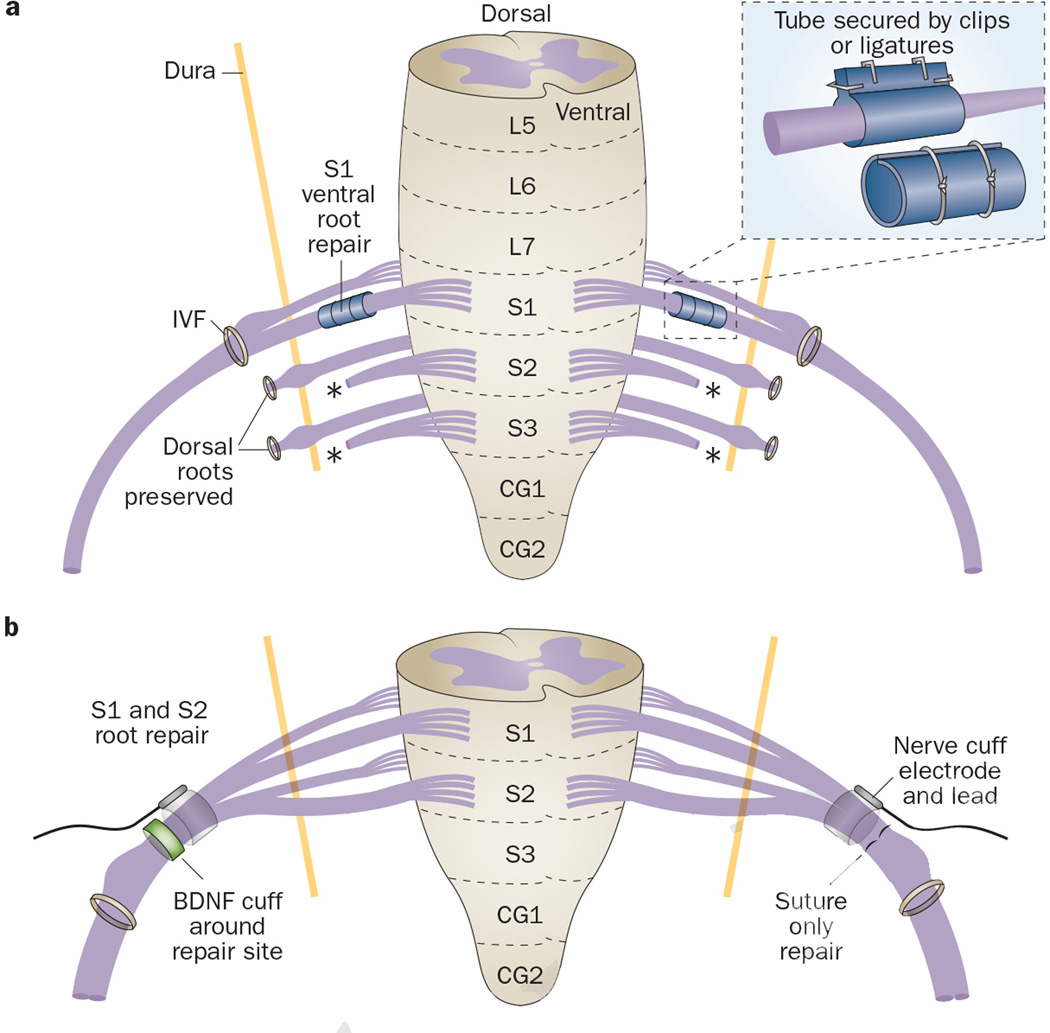

In the late 1960s, Sundin and Carlsson23 explored homotopic intradural reconstruction of severed sacral ventral roots S1 and S2 in a cat model, using direct repair combined with a (then) novel tubulation technique (Figure 2a, Table 1). S1, S2 and S3 ventral roots were transected bilaterally, while dorsal sacral roots were preserved. Proximal ends of the severed S1 ventral roots were then sutured intradurally and homotopically to the distal ends of the S1 ventral roots in two cats, whereas a bilateral S2 to S2 repair was performed in two other cats. Severed ends were not sutured, but realigned end-on-end, encircled by a stainless steel mesh cylinder impregnated with filter material, and secured by circular silk ligatures or silver clips (Figure 2a).50–52 Between 4–6 months after surgery, bladder contractions were observed after direct stimulation of both S1 and S2 ventral roots, indicating that functional recovery of the micturition reflex could be achieved by homotopic reconnection of transected S1 and S2 ventral roots. In addition, histological analysis of the repaired roots showed axonal regrowth across the repair site in all animals.

Figure 2.

Homotopic root repair.23, 25, 26, 36 a | Intradural repair of ventral roots S1 and S2 in a cat model using a tubulation technique (exemplified for S1). The cylinder consists of mesh sheets and filter material, rolled into a tube around nerves and secured by ligatures or silver clips. b | Extradural bilateral repair of S1 and S2 ventral and dorsal roots in a canine model using end-on-end realignment and suturing (exemplified for ventral S1 and S2). One site is surrounded by a silicone sheath to enable delivery of BDNF. Bilaterally, a nerve cuff electrode is placed immediately proximal to the repair site to assess neurally evoked bladder emptying via FES. Abbreviations: BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CG, coccygeal segment; FES, functional electrical simulation; IVF, intervertebral foramen; L, lumbar; S, sacral.

Table 1.

Homotopic root repair surgeries

| Study | Procedure | Functional recovery (time) |

Evidence | Limitations | Possible application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carlsson et al. (1968)23 |

S1 or S2 v, bilateral Intradural, secured by tubulation Feline model |

Yes (4–6 months) |

Recovery of micturition reflex and axonal regrowth across repair site |

Small study (n = 2 per type of repair); limited utility of tubulation |

S root or cauda equina injuries |

| Meier et al. (1977, 1978)53, 54 |

L5 or S1 dv, bilateral Intradural Porcine model |

Not tested (3 months) |

Axonal regrowth across repair site (v > r) |

Bladder function not assessed |

S root or cauda equina injuries |

| Conzen et al. (1982)25 |

S2–S4 v, bilateral S2 and S3 dv, unilateral or bilateral S2, dv, unilateral or bilateral Intradural Porcine model |

Yes (4–7 months) |

Recovery of micturition reflex after complete decentralization or sacral de- efferentation and bilateral dv repair; axonal regrowth across repair site |

Function assessed in 1 animal per type of repair; unilateral repair less effective than bilateral |

S root or cauda equina injuries |

| Ruggieri et al. (2006)36 |

S1 and S2 v, bilateral extradural; bilateral FES, unilateral BDNF canine model |

Yes (5–12 months) |

Increased bladder pressure and/or flow of saline out of urethra after FES axonal regrowth from spinal cord across repair site to bladder |

NCE failure in several dogs; BDNF induced neuroma formation at repair site |

S root or cauda equina injuries |

Abbreviations: BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; d, dorsal; dv, dorsal and ventral; FES, functional electrical stimulation; L, lumbar; NCE, nerve cuff electrode; S, sacral; SCI, spinal cord injury; v, ventral.

Similar studies were performed by Sollmann and colleagues between 1977 and 1982. 25, 53, 54 They explored microsurgical repair of sacral roots immediately after transection in a porcine model, using intradural root reconstruction after homotopic end-on-end alignment. In two studies, the researchers transected and repaired L5 or S1 dorsal and ventral roots in 18 pigs (Table 1).53, 54 The roots were collected 3 months after surgery and examined using electron microscopy. Axonal regeneration was evident across all dorsal and ventral repair sites, although regrowth was more advanced in repaired ventral motor roots than in dorsal sensory roots. Unfortunately, longer survival times would have been required to enable full assessment of axonal regrowth, and recovery of bladder function was not examined in these two studies. Thus, the importance of the integrity of L5 or S2 signalling on bladder function remained unclear.

In 1982, Conzen and Sollmann25 extended these studies by examining the effects of immediate bilateral versus unilateral reconstruction of a mix of sacral roots (Table 1). One pig underwent transection (de-efferentation) followed by immediate reconstruction of S2, S3 and S4 ventral roots only, bilaterally. In this animal, the lost micturition reflex returned after 4 months, in contrast to another animal that underwent similar transection of S2, S3 and S4 ventral roots, but no reconstruction. Five additional pigs underwent complete sacral decentralization via bilateral transection of the S2, S3 and S4 ventral and dorsal roots. In each animal, the micturition reflex disappeared after these transections. In two of the five pigs, bilateral or unilateral reconstruction of the S2 and S3 ventral and dorsal roots resulted in a return of the micturition reflex by 4.5 months or 7 months, respectively, but bladder capacity remained increased at 7 months in the pig with unilateral reconstruction. In another pig, in which only S2 roots were reconstructed bilaterally, return of micturition without increased bladder capacity was observed after 5 months. However, in one animal, in which the S2 roots were reconstructed unilaterally only, the micturition reflex did not recover. In the remaining animal, complete initial decentralization could not be determined. Although the authors reported histological evidence of axonal regrowth across the repair site, the histology was not shown in their report. Overall, these results indicate that integrity of signalling across S2—and perhaps also S3— ventral roots, even if only unilateral, is important for preservation or recovery of the micturition reflex. Over the course of these studies, the researchers observed that spared thoracic and lumbar sympathetic input to the bladder was still present in the hypogastric nerve after sacral de-efferentation (that is, after bilateral transection of S2 to S4 ventral roots) and that this input does not produce detrusor muscle contractions in pigs,25 similar to humans but different from rats.29

In 2006, we assessed the feasibility of functional bladder reinnervation in 11 dogs after bilateral transection and immediate extradural homotopic reconstruction of S1 and S2 ventral and dorsal roots, which induced urinary bladder contraction as confirmed by intraoperative electrical stimulation (Figure 2b; Table 1).36 Bladder decentralization was achieved in all animals by bilateral transection. In 10 dogs, roots were then repaired in the extradural space using end-on-end realignment and suturing of the epineurium. The remaining dog served as a denervated control. One repair site in each animal was surrounded by a silicone sheath connected to an osmotic pump (Figure 2b) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF, 2.5 µg/h) given for 14 days to determine effects on neuronal regeneration. Bilaterally and immediately proximal to the repair site, a nerve cuff electrode (NCE) was placed around the sutured root bundles. In around 60-day intervals, the electrodes were stimulated to assess whether neurally evoked bladder emptying had been achieved. Fluid flow from the urethra was observed in five dogs during functional electrical stimulation (FES) of repaired roots located contralateral to the BDNF delivery side. In 10 dogs, retrograde nerve tracing and histological examination at 1 year after surgery showed axonal regrowth from the spinal cord to the bladder, although only contralateral to the BDNF delivery side. By contrast, the BDNF delivery site showed circuitous axonal outgrowth into the delivery sheath and surrounding connective tissue, suggesting neuroma formation rather than improved growth of axons across the repair site. Based on the results of the contralateral side, we concluded that transected and repaired S1 and S2 ventral roots are capable of functional reinnervation of the bladder, and that FES could be used to stimulate bladder emptying.

Heterotopic repair

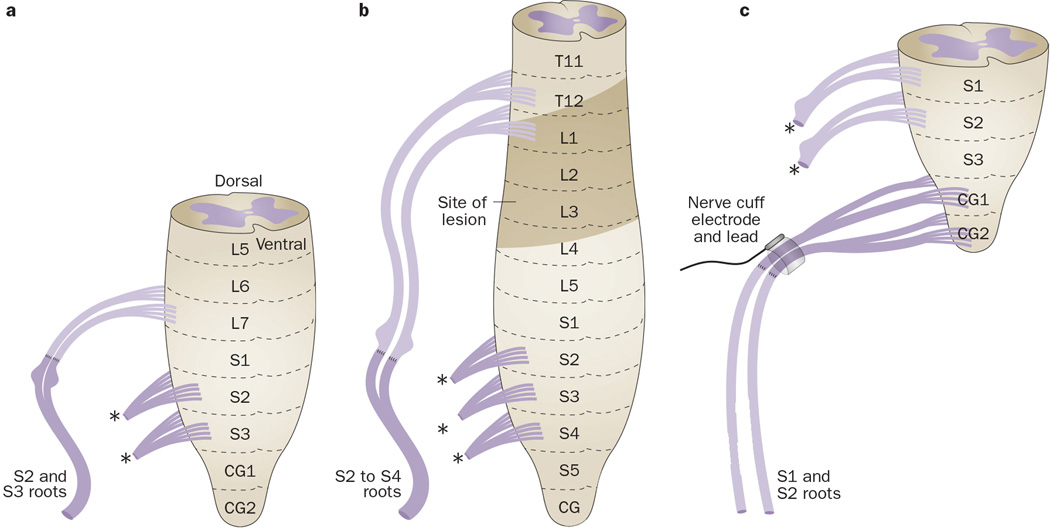

In 1907, one of the pioneers of peripheral nerve repair methods, Kilvington, performed a study in three dogs to determine whether dorsal or ventral spinal roots could regenerate after transfer to heterotopic dorsal or ventral roots (Table 2).15 In the first dog, the left S1 dorsal and ventral roots were isolated intradurally and sectioned. In the second dog, the left L7 ventral root was sectioned. Then, the proximal ends of each were sutured to the distal ends of ipsilateral S2 and S3 dorsal and ventral roots. In the third dog, the left L7 dorsal and ventral roots were sectioned and sutured to ipsilateral S2 and S3 dorsal and ventral roots(Figure 3a). At 4–6 months after repair, the spinal canal, but not the dura, was reopened and the repaired roots were isolated extradurally. In the first dog, faradic stimulation of the left S1 repaired roots, but not the contralateral severed S1 nerve, elicited strong tail movement, contraction of the pelvic diaphragm, and expulsion of bladder contents. In the second dog, after transection of the spinal cord at L6, faradic stimulation of the transferred L7 roots elicited contraction of pelvic muscles, contraction of the anal sphincter with defecation, and partial expulsion of bladder contents. In the third dog, similar results, and additionally, leg contractions, were observed when faradic current was applied to the transferred L7 roots after transection of the spinal cord at L6. As a control, stimulation of contralateral S2 and S3 roots produced slightly more forceful bladder contractions. Thus, an intradural transfer of L7 or S1 dorsal roots to S2 and S3 mixed dorsal and ventral roots can provide at least partial return of bladder emptying, although forceful bladder contractions were not observed in any of the three dogs.

Table 2.

Heterotopic root repair surgeries

| Study | Procedure | Functional recovery (time) |

Evidence | Limitations | Possible application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kilvington (1907)15 |

S1 dv → S2 and S3 dv L7 v → S2 and S3 dv L7 dv → S2 and S3 dv Intradural, unilateral Canine model |

Yes (4–6 months) |

Partial or complete expulsion of bladder contents after faradic stimulation |

Small study (n = 3); weak bladder contractions |

S SCI, S root or cauda equina injuries |

| Kilvington (1907)15 |

T12 or L1 d → S2 and S3 dv Intradural, unilateral, 2-stage surgery Patient with SCI and cadaver |

Surgery abandoned |

na | Scar tissue formation between surgeries prevented repair |

Not recommended owing to scar formation |

| Carlsson et al. (1968)23 |

L7 v → S1 or S2 v L6 v →S1 v Intradural, bilateral, secured by tubulation Feline model |

Yes (5 months) |

Recovery of micturition reflex after L7 → S1 and L6 → S1 repair; axonal regrowth across repair site. |

limited utility of tubulation |

S root or cauda equina injuries |

| Ruggieri et al. (2008)35 |

CG1 and CG2 dv → S1 and S2 dv Extradural, bilateral Canine model |

Yes (6 months) |

Increased bladder pressure under FES |

Not suitable for humans due to vestigial coccyx |

na |

Abbreviations: →, transfer to; CG, coccygeal; d, dorsal; dv, dorsal and ventral; FES, functional electrical stimulation; L, lumbar; na, not applicable; S, sacral; SCI, spinal cord injury; v, ventral.

Figure 3.

Heterotopic root repair.15, 27, 34 a | Unilateral transfer of the L7 dorsal and ventral roots to ipsilateral S2 and S3 dorsal and ventral roots in a dog. b | Unilateral intradural transfer of T12 or L1 dorsal roots to combined dorsal and ventral roots at S2 to S4 in a patient with a SCI extending from T12 thru L4. c | Bladder decentralization by severing S1 and S2 ventral and dorsal roots intradurally and bilaterally in a dog, followed by extradural end-on-end repair, using proximal ends of transected CG1 and CG2 ventral roots, and placement of a NCE around the root bundles. Abbreviations: CG, coccygeal; DRG, dorsal root ganglion; ; L, lumbar; NCE, nerve cuff electrode; S, sacral; SCI, spinal cord lesion; T, thoracic.

These results encouraged Kilvington to attempt the same surgical strategy in a human cadaver and then in a patient with a spinal cord lesion as high as the T12 dorsal root on one side and the T11 dorsal root on the other side, and extending for three vertebral levels (Figure 3b, Table 2).15 Kilvington attempted to reinnervate the bladder by intradural transfer of T12 or L1 dorsal roots to combined dorsal and ventral roots at S2 to S4. In the first operation, he identified the level of the SCI and dissected out feasible spinal roots near to the intervertebral foramen with enough length to transfer to sacral roots.15 Unfortunately, 10 days later in the second surgery, the root transfer could not be completed owing to scar tissue formation around the previously dissected roots. Kilvington concluded that this kind of surgical technique should be performed as a single procedure to avoid complications from scar tissue formation.

In 1968, Carlsson and Sundin23 also explored heterotopic reconstruction of severed sacral ventral roots in 6 adult female cats by intradural transfer of L6 or L7 ventral roots to S1 or S2 ventral roots, bilaterally (L6 or L7 to S1, or L7 to S2), using their tubulation technique (Table 2). At 5 months after surgery, bladder contractions were observed after direct stimulation of either the L6 or the L7 ventral roots, indicating that functional recovery of the micturition reflex could be achieved by transferring L6 or L7 to S1 and S2 ventral roots. Histological analysis showed axonal regrowth across the repair site in all animals, further supporting the evidence for regeneration of transected and repaired sacral ventral roots.

In 2008, we examined whether bladder reinnervation could be achieved by extradural (yet still within the vertebral column) transfer of coccygeal roots to severed sacral roots in a dog model (Figure 3c, Table 2).35 First, ventral roots of S1 and S2 segments shown to trigger bladder contractions were severed bilaterally to decentralize the bladder, which involved severing the dorsal roots because ventral and dorsal roots join together before exiting the dura. Then, in 3 dogs, ventral roots that induced only tail movement during intraoperative FES (that is, coccygeal (CG) 1 and CG2 roots) were transected and their proximal ends sutured to the distal ends of transected S1 and S2 ventral roots using bilateral end-on-end repair. Last, a NCE was placed around the root bundles, immediately proximal to the repair site. Abdominal vesicostomies enabled bladder emptying during the recovery period.6 In one dog, FES on day 178 after surgery induced increased bladder pressure and urethral fluid flow.35 Stimulation of the anterior vesical branch of the pelvic nerve after surgery also resulted in a substantial increase in bladder pressure with urethral fluid flow in 3 dogs on days 450, 373 and 426 after surgery. Retrograde dye tracing showed labelled neuronal cell bodies in ventral coccygeal cord segments, demonstrating growth of motor axons from the coccygeal cord segment to the bladder across the repair site. These results indicate that bladder reinnervation can be achieved by heterotopic transfer of somatic motor roots that usually innervate skeletal muscle to sacral roots subserving bladder function. However, transfer of coccygeal roots to sacral roots is not suitable for humans owing to the presence of only vestigial coccygeal segments in humans.

In summary, homotopic and heterotopic end-to-end root repair seems most suitable for patients with sacral vertebrae fracture in which the sacral roots and maybe the cauda equina are injured, but the spinal cord remains intact.

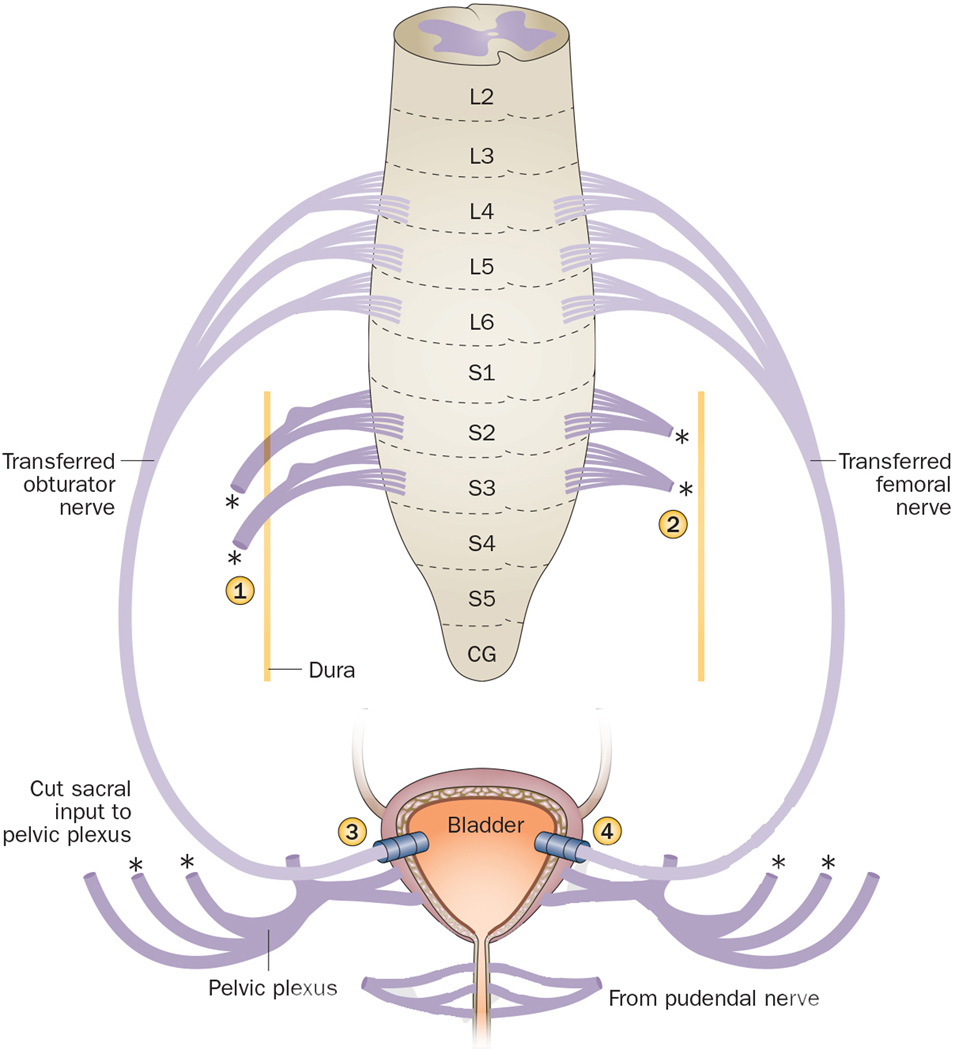

Transfer of peripheral nerves to sacral roots

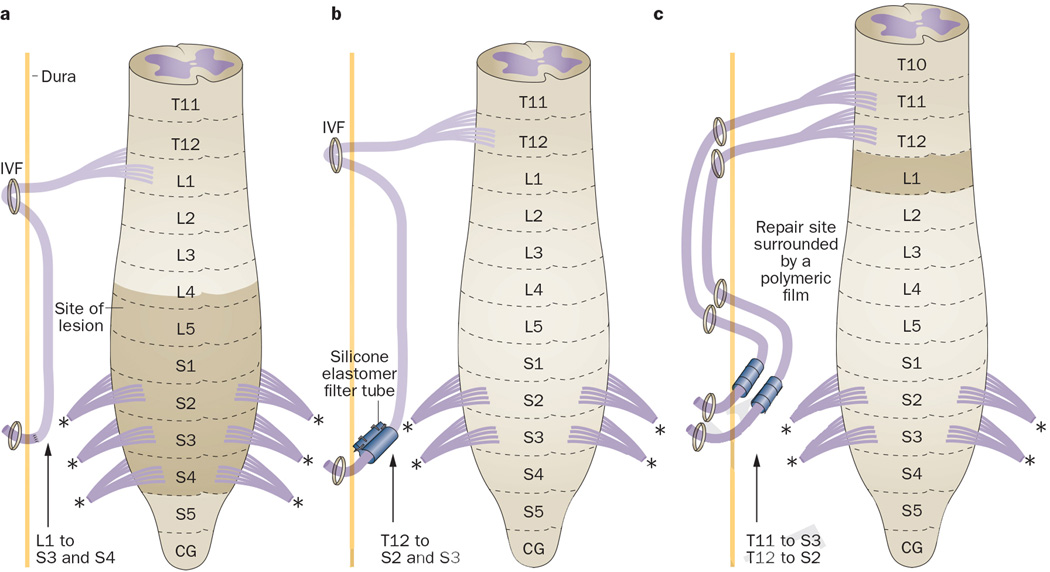

Several groups have examined the feasibility of using intercostal and spinal nerves as donors in nerve coaptation surgeries in animal models, cadavers and in patients with injuries to caudal spinal cord segments or to the cauda equina (Figure 4, Table 3).22, 24, 27, 30, 39

Figure 4.

Extradural-to-intradural transfer of spinal nerves to sacral roots.24, 27, 30. a | After extradural transection of the L1 nerve in its IVF, the nerve is moved back into the dural sac and sutured to the proximal ends of S3 and S4 dorsal and ventral roots. b | T12 nerves are extradurally transected, moved intradurally and anastomosed end-to-end to S2 and S3 ventral and dorsal roots, using a silicone elastomer filter formed into a tube and secured with silver clips. c | Extradurally neurolysed T11 and T12 nerves are reintroduced into the vertebral canal at the upper sacral level and aligned to S2 and S3 ventral roots, using a polymeric film secured with biological glue. Abbreviations: CG, coccygeal; IVF, intervertebral foramen; L, lumbar; S, sacral; T, thoracic.

Table 3.

Extradural to intradural transfer of nerves to spinal roots

| Study | Procedure | Functional recovery (time) |

Evidence | Limitations | Possible application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frazier et al. (1912)27 |

T12 or L1 nerves → S3 and S4 dv roots Unilateral 1 patient with SCI |

Only with mechanical pressure (8 months after L1 transfer) |

Partial recovery of bladder emptying |

T12 nerve too short to reach sacral roots; Valsalva manoeuvre required for bladder emptying |

SCI in lower L and S segments |

| Carlsson et al. (1980)24 |

T12 nerves → S2 and S3 dv roots Bilateral, secured with silicone elastomer filter and silver clips Model: Human 2 patients with SCI |

Yes (8–12 months; improved further by 30–36 months) |

Recovery of penile sensation; With full bladder, one patient able to initiate micturition, the other able to empty with abdominal straining. |

Nerve graft needed to link T12 to sacral roots; Possibility of developing detrusor–EUS dyssynergia. |

SCI in lower L and upper S segments |

| Vorstman et al. (1987)42 |

T10 or T12 nerves → S3 v roots Cadavers |

na | na | Nerve graft needed to link T12 to S3 roots |

SCI in lower L and upper S segments |

| Livshits et al. (2004)30 |

T1 and T12 nerves → S2 and S3 dv roots Unilateral, secured with polymeric film tube and biological glue 11 patients with chronic SCI |

Yes (10–12 months) |

Recovery of reflex voiding in all patients; Re- established bulbocavernous, cremasteric and anal reflexes in 8 patients |

Paresthesias in the groin and scrotum; 3 patients needed Valsalva manoeuvre to empty bladder |

SCI in lower L and S segments, spina bifida, and S root injury |

Abbreviations: →, transfer to; d, dorsal; dv, dorsal and ventral; EUS, external urethral sphincter; L, lumbar; na, not applicable; S, sacral; SCI, spinal cord injury; T, thoracic; v, ventral.

In 1912, Frazier and Mills27 attempted to relieve urinary and faecal incontinence in a patient with SCI at lower lumbar and sacral levels and performed a extradural-to-intradural transfer of L1 spinal nerves to S3 and S4 dorsal and ventral sacral roots (Figure 4a, Table 3). After laminectomy, initially the T12 ventral root was transected extradurally , but this root was not long enough to reach the conus medullaris. Thus, the surgeons transected one L1 nerve extradurally within its intervertebral foramen, moved it back into the dural sac through a transverse incision, and sutured its distal end to the proximal ends of S3 and S4 dorsal and ventral roots intradurally. At 8 months after the operation, the patient was able to partially empty the bladder using suprapubic mechanical pressure.27 Findings from this study are limited by the small sample size and the absence of specific evaluation of detrusor function, and its success is weakened by the requirement of a Valsalva manoeuvre for bladder emptying; yet, these data held promise for future surgeons.

In 1980, Carlsson and Sundin24 performed similar nerve transfer surgeries in two patients with traumatic lesions to their caudal vertebral column (Figure 4b, Table 3). The patients underwent laminectomy from T11–L2 at 10–14 days after vertebral fracture injury. During surgical exploration, there were signs of inflammation in the caudae equinae and residual small haemorrhages and lacerations in cauda equina nerves up to the entrance of the L1 roots. During surgery, the T12 intercostal nerves were extradurally bilaterally transected at 2–3 cm distal to their dorsal root ganglion (DRG), and moved intradurally and downwards to transected S2 and S3 ventral and dorsal roots emerging from the injured cord area. The T12 nerves were then anastomosed end-to-end to the sacral roots without sutures, using a silicone elastomer filter formed into a tube and secured with silver clips.

One patient had repeated UTIs between 3 months and 8 months after surgery and by 8 months the patient had hypersensitivity at the base of the penis on the left side, but also detrusor–sphincter dyssynergia during cystometry. By 12 months, the patient had sensitivity to touch and pain at the base of the penis on the left side, and felt urgency to void. When his bladder was full the patient could initiate micturition voluntarily and the residual urine was 35 ml. Reinnervation of the urethral sphincter was detected using electromyography, and detrusor contractions were detected by cystometry. Between 18 months to 30 months, the patient was able to achieve erection on local stimulation and voluntary voiding with a residual volume between 40 ml and 70 ml.24

In the second patient, the neurological status was unchanged between 2 months and 8 months after surgery, and the patient had persistent UTIs. By 11 months, the patient was able to initiate voiding voluntarily by abdominal straining. We hypothesize that, as T12 innervates abdominal musculature, contracting these muscles should be the appropriate trigger to activate the newly innervated detrusor muscle. Between 12 months to 30 months after surgery, residual volume ranged from 20 ml to 120 ml and UTIs occurred frequently, although the patient was still able to initiate the micturition reflex by abdominal straining using the Valsalva manoeuvre. At 30 months, he underwent a transurethral external sphincterotomy to alleviate the UTIs attributed to large residual urine volumes. At 32 months and 36 months, the patient felt the desire to void and could initiate voiding voluntarily, although by 36 months an external catheter was needed owing to slight incontinence. In conclusion, by about 32 months after surgery, both patients could feel the urge to void, initiate micturition voluntarily, and empty their bladders satisfactorily. These results indicate restoration of bladder function is possible by transferring mixed extradural suprasacral nerves to intradural dorsal and ventral sacral roots that innervate the bladder. However, an improved surgical method was needed to avoid sphincter dyssynergia.

To meet this need, Vorstman et al.42 explored different approaches for this method in four human cadavers (Table 3). After a laminectomy to expose the dura and spinal nerves from T8 to S4, intercostal nerves were traced extradurally from the posterior axillary line to their origin to estimate the length of nerve available for a transfer to the ventral root of S3. A more limited approach was also investigated, with a T-shaped incision at the T9 vertebral body and extending caudally for five vertebral segments. The intervertebral foramen was enlarged to enable transfer of the T10 spinal nerve from an extradural position into the spinal canal to a position proximal to the DRG of the ipsilateral S3 ventral root.42 The T10 intercostal nerve was long enough for this transfer. Upon assessment whether transfer of the T12 nerve to the S3 ventral root was possible, they determined that a nerve graft, such as 3 cm of the sural nerve, was needed to bridge the gap between the T12 nerve and the S3 ventral root.

Livshits and colleagues30 also coapted intercostal nerves in eleven patients with chronic SCI at the L1 level (Figure 4c, Table 3). Patients underwent surgery 1–3 years after SCI (mean 2 years). Neurolysis of T11 and T12 intercostal nerves was carried out at a distance of 20–21 cm from the costal angle where the nerves divide onto smaller diameter branches The nerves were then transferred into the vertebral canal intradurally at the upper sacral level, and sutured to the ventral roots of S2 and S3, which were identified by intraoperative FES as evoking increased intravesical pressure. The nerve roots were secured using a tube created from polymeric film secured with biological glue. At 10–12 months after surgery, all patients showed signs of restoration of the voiding reflex and improved urodynamics (voiding pressure was restored to 30.5 cmH2O ± 4.9 cmH2O). Eight patients had reappearance of their bulbocavernous, cremasteric and anal reflexes, and improved urodynamic parameters, although paraesthesias in the groin and scrotum also developed. Livshits et al.30 concluded that decentralized bladders can be recentralized and voiding recovered if input is provided via transfer of lower thoracic intercostal nerves to sacral ventral roots that innervate the bladder, and that this procedure would be most suitable for patients with SCI in lumbar regions and children with spina bifida (Table 3).

Thus, it is possible to restore bladder function by transferring intercostal or lumbar nerves within the vertebral canal and dura to sacral ventral roots innervating the bladder. However, such procedures have limitations: patients might need to use Valsalva straining to empty the bladder; an intervening nerve graft might be needed when transferring T12 nerves to sacral roots; patients might develop paraesthesias and detrusor–sphincter dyssynergia.

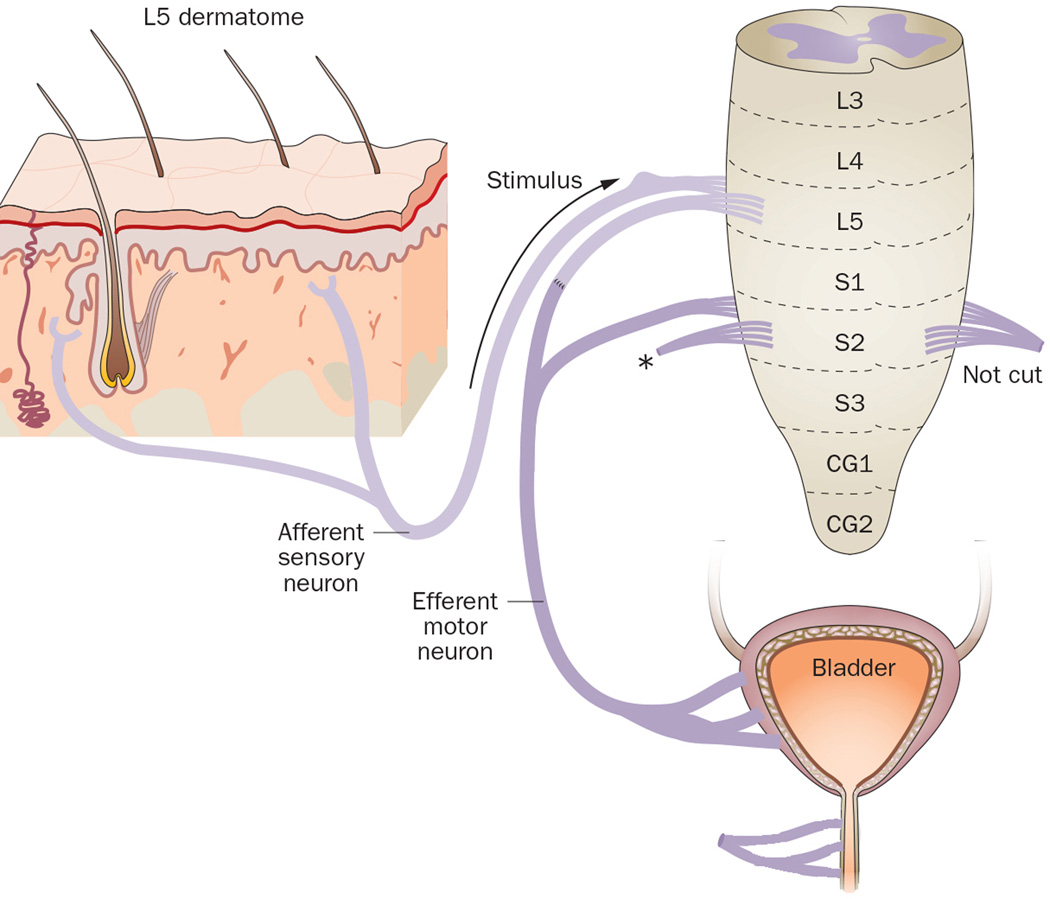

Transfer of roots to sacral spinal nerves

Sundin and Carlsson38 explored afferent fibre regeneration for functional recovery of bladder reflexes in a cat model (Figure 5a, Table 4). They transferred L7 or S1 dorsal sensory roots to S1 or S2 mixed (dorsal and ventral) spinal nerves, using their tubulation method (specifically, L7 to S1 in five cats and S1 to S2 in 4 cats ). L7 or S1 dorsal roots were transected immediately distal to their DRG, sparing the ventral motor roots. The remaining dorsal sacral roots were transected intradurally for deafferentation of the pelvic and pudendal nerves. In addition, only the efferent fibres of the recipient S1 or S2 roots were transected, leaving the remaining sacral efferent fibres intact. At 8–11 months after surgery, the micturition reflex returned in cystometrograms in five of nine cats, which was a lower proportion than they had previously found after ventral root repair.23 They concluded that in the L7 to S1 anastomosis group, the presence of a micturition reflex indicates that L7 dorsal root afferents had synaptic connections with the efferent limb of this reflex in the S1 spinal segment. However, it is unclear whether the efferent limb was carried by new, reinnervated motor fibres in the S1 spinal nerve or through the other remaining ventral sacral roots that were not transected. Polysynaptic multisegmental reflex circuits are probably involved in the micturition reflex, similar to other reflexes. With regard to the storage reflex, the average bladder capacity increased twofold to fourfold from 34 ml preoperatively during the first 2 months after nerve transection and reconstructive surgery. At 8–11 months after surgery, the average bladder capacity rose to 92 ml. Notably, the capacity further increased after transection of the previously reconstructed dorsal roots, indicating that reinnervation had occurred. In addition, intravesical pressure elevation or bladder volume decrease could be elicited in half of the reconstructed animals after FES of their pelvic and pudendal nerves. The researchers also observed propagated axon potentials in the L7 or S1 dorsal roots after stimulation of the pudendal and pelvic nerves. After transection of the reconstructed roots, the storage reflex and propagated axon potentials were no longer observed. FES of the spared hypogastric nerve (which arises from low thoracic segments; Figure 1) resulted in bladder relaxation. Transection of the hypogastric nerve abolished this response. Although this could indicate utilization of existing afferent pathways in the hypogastric nerves for the storage reflex, other studies in cats have shown that the afferent limb of this reflex is in sacral dorsal roots, and that the efferent limb is in the hypogastric nerve.48, 49, 55–57 Thus, adaptive reorganization of circuitry after heterogeneous root repair reconstruction might occur, in which both micturition and storage reflexes show functional recovery.23, 38

Figure 5.

Intradural-to-extradural transfer of lumbar or sacral roots to sacral spinal nerves.37, 38, 41. a | Transfer of L7 or S1 dorsal sensory roots to S1 or S2 spinal nerves, respectively, in a cat model, using a tubulation method. Ventral motor roots and sacral efferent fibres other than indicated S1 and S2 roots are left intact. b | Transfer of L7 dorsal and ventral roots to the S1 spinal nerve, after extradural unilateral transection of L7 to S3 roots, in a cat model, using a bridging S2 root graft in some animals. Abbreviations: CG, coccygeal; L, lumbar; S, sacral.

Table 4.

Transfer of spinal roots to spinal nerves

| Study | Procedure | Functional recovery (time) |

Evidence | Limitations | Possible application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sundin et al. (1972)38 |

L7 d roots → S1 nerves S1 d roots → S2 nerves Secured by tubulation Feline model |

Yes (8–11 months) |

Recovery of micturition and storage reflexes; propagated axon potentials during FES of pudendal and pelvic nerves |

Functional recovery after afferent fibre regeneration is less than in study of efferent fibre regeneration23 |

S SCI, S root or cauda equina injuries |

| Vorstman et al. (1986)40, 41 |

L7 dv roots → S1 nerves Feline model |

Yes (7 months) |

Observed recovered micturition reflex during FES |

Nerve graft might be needed; detrusor muscle should be intact |

SCI in L segments, spina bifida |

Abbreviations: →, transfer to; d, dorsal; dv, dorsal and ventral; FES, functional electrical stimulation; L, lumbar; S, sacral; SCI, spinal cord injury.

Vorstman and colleagues40, 41 examined the feasibility of transferring dorsal and ventral roots of lumbar segments to sacral mixed spinal nerves for reinnervation of unilaterally decentralized bladders in cats (Figure 5b, Table 5). In one study, 11 adult female cats underwent unilateral transection of L7–S3 roots at an extradural site distal to the DRG, followed by immediate transfer of L7 dorsal and ventral roots to the S1 spinal nerve.41 In six animals, a 4–6 mm portion of the ipsilateral S2 root was interposed into the repair site as a bridge. Each repair site was secured by microsutures. At 7 months after surgery, the repair sites were surgically exposed to evaluate if the bladder had regained function, using cystometric and electrophysiological methods. Detrusor contractions were observed in seven cats during maximum stimulation of the isolated roots, demonstrating that suprasacral mixed axons (specifically, L7 sensory and motor roots) transferred to a mixed sacral nerve (S1) can recentralize a unilaterally decentralized bladder in cats. No significant differences were observed between cats with and without the intervening nerve graft.41 In a second study, the researchers reported that the average bladder response to stimulation of the transferred root was 40% lower than that of a normal (nonoperated) S1 cystometric response. Similar to the results of Sundin and Carlsson,38 these data also support a return of the micturition and storage reflexes after heterogeneous sensory and motor root transfers to sacral spinal nerves innervating the bladder—at least in cats. This type of procedure could be used in patients with NBD as a consequence of SCI or spina bifida, provided detrusor muscle viability is preserved.40, 41

Table 5.

Coaptation of peripheral nerves to pelvic or pudendal nerves

| Study | Procedure | Functional recovery (time) |

Evidence | Limitations | Possible application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer of peripheral nerves to pelvic nerves | |||||

| Trumble (1935)17 |

Hypogastric nerve → pelvic nerve on one side Obturator nerve → pelvic nerve on other side Canine model |

No (hypogastric nerve) Yes(obturator nerve) (6–12 months) |

FES of obturator nerve induced bladder contractions |

Limited motor nerve regeneration (hypogastric nerve) |

Lesion of cauda equina |

| Kimmel (1966)29 |

Hypogastric nerve → pelvic nerve Obturator nerve → pelvic nerve Pelvic nerve repair Arterial sleeve method Rat model |

No (hypogastric nerve) Yes (obturator nerve) Yes (repair) (2–8 months) |

Recovery of bladder function after obturator nerve transfer and pelvic nerve transfer |

Atonic bladder (hypogastric nerve → pelvic nerve) |

Lesion of cauda equina |

| Transfer of peripheral nerves to pudendal or pelvic nerves | |||||

| Ruggieri et al. (2008)34, 35 |

Genitofemoral nerve → anterior ventral branch of pelvic nerve Vesicostomy Canine model |

Yes (4–6 months) |

Retrograde dye evidence of axon regrowth from cord to bladder |

Sustained abdominal contraction could result in unintentional voiding; indwelling FES electrodes need improved design |

SCI in lower L and S segments, and cauda equina; patient needs control of abdominal muscles if FES not used |

| Brown et al. (2011)33 |

Motor branches of femoral nerve → pudendal nerve Cadavers or canine model |

Yes (dogs) (3–6 months) |

Reinnervation of EUS and anal sphincter |

Not yet tested in patients |

SCI in lower L and S segments; lesion of cauda equina |

| Brown et al. (2012, 2013)20, 21 |

Ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve → pelvic nerve Femoral nerve → pelvic nerve Cadavers |

na | na | Not yet tested in patients |

SCI in lower L and S segments; lesion of cauda equina |

| Direct detrusor muscle reinnervation by somatic nerve transfer | |||||

| Rao et al. (1971)32 |

Obturator or femoral nerves implanted directly into detrusor muscle Intramuscular tunnel (arterial sleeve) Canine and rat model |

No (7.5–10 months) |

na | Neuroma formation; no regeneration of motor end plate; increased frequency of UTIs |

Lesion of cauda equina |

Abbreviations: →, transfer to; EUS, external urethral sphincter; ES, electrical stimulation; L, lumbar; na, not applicable; S, sacral; SCI, spinal cord injury.

Based on these studies, intradural root crossover or nerve-to-root crossover techniques for root repair are more suitable for patients with spinal cord or cauda equina injury, as they enable the surgeon to bypass the injured spinal cord segments. The use of intercostal nerves or lumbar nerves for crossover surgeries seems to be limited to patients with lower lumbar or upper sacral SCI or spina bifida.

Peripheral nerve transfer

Peripheral nerves to pelvic nerves

Nerve transfer as a method for bypassing an injured spinal cord region and reinnervation of bladders was first conceptualized in 3 dogs in 1907,15 and experimental results in 5 dogs were reported by Trumble in 1935 (Table 5).17 A study in 1907 by Elliott58 in a variety of animal species demonstrated that FES of pelvic parasympathetic splanchnic nerves induced strong and sustained contractions of the detrusor muscle causing voiding. FES of the hypogastric nerve, which originates from thoracic spinal segments and the sympathetic splanchnic nerve to the bladder, induced a slight transitory increase of intravesical pressure, before relaxation of the detrusor muscle and a decrease in intravesical pressure.58 These latter results were confirmed in subsequent studies.59–62

Based on Elliott’s findings, Trumble17 performed a two-stage surgical procedure as a possible means of restoration of the micturition and storage reflexes. Using a canine model, he first sectioned the hypogastric and pelvic splanchnic nerves unilaterally (between the spinal cord and the pelvic plexus) and transferred the proximal end of the hypogastric nerve to the distal end of the transected pelvic nerve on that side. Then, after several months of recovery, he transferred the obturator nerve to the distal end of the transected pelvic nerve on the contralateral side(Figure 6a). After 6–12 months, FES of the transferred obturator nerve induced bladder contractions, documented using a manometer, whereas stimulation of the hypogastric nerve that was transferred in the first operation produced only weak bladder contraction.

Figure 6.

Transfer of peripheral nerves to pelvic nerves.17, 29,33–35. a | Transfer of the hypogastric or obturator nerves to the pelvic splanchnic nerves (transected between the spinal cord and the pelvic plexus), or repair of the transected pelvic nerve ends. b | Transfer of the genitofemoral nerve to the anterior vesical branch of the pelvic nerve after bilateral transection of the dorsal and ventral sacral roots to the bladder. Abbreviations: CMG, caudal mesenteric ganglion; L, lumbar; NCE, nerve cuff electrode; S, sacral.

Trumble hypothesized that transfer of the hypogastric nerve led to more limited recovery owing to its reduced numbers of motor axons, compared with transfer of the obturator nerve—a somatic nerve with numerous myelinated motor axons.17 These results suggest that nerve transfer is suitable for patients with a lesion in the cauda equina. However, limitations of this procedure include that coaptation of the obturator nerve might cause paralysis of thigh abductor muscles, and coaptation of the hypogastric nerve may only produce weak contractions that are not under voluntary control.

In 1966, Kimmel29 extended Trumble’s idea by performing three variations of this nerve coaptation method in rats. First, the right pelvic splanchnic nerve was transected in all animals in all three experimental groups (Figure 6a). Then, in the first group, the proximal end of both hypogastric nerves were transferred to the distal end of the right pelvic nerve; in the second group, the proximal end of the right obturator nerve was transferred to the distal end of the right pelvic nerve; and in the third group, the transected pelvic nerve ends were repaired. Results were compared to three control groups that had undergone one of the following procedures: severance of right and left pelvic splanchnic nerves; severance of right and left pelvic splanchnic nerves, as well as the superior hypogastric nerve plexus; severance of right and left pelvic splanchnic nerves, superior hypogastric plexus, and all nerves supplying the ventrolateral abdominal wall. In the experimental groups, an arterial sleeve method was used for repair.63

At 12 weeks after surgery, Kimmel performed a second procedure in the experimental groups to transect the—until then intact—left pelvic splanchnic nerve.29 Most animals died of UTIs and, overall, survival ranged from 7–35 weeks. In the control groups, rats with both pelvic nerves severed were incontinent, whereas rats with one intact pelvic splanchnic nerve maintained good urinary function, based on palpated bladder emptiness and absence of incontinence. Rats with a transfer of hypogastric nerve to pelvic nerve showed nerve regeneration in histological analysis, but did not regain bladder function and developed atonic bladders. Rats with transfer of obturator nerve to pelvic nerve also showed nerve regeneration and recovered urinary function close to normal levels. However, animals in this group that had died of UTIs only had limited nerve regeneration. Finally, rats with pelvic nerve repair regained more robust urinary function than animals with obturator nerve to pelvic nerve transfer.29

These results indicate that it is possible to retain bladder function in rats with just one intact pelvic parasympathetic splanchnic nerve, or by transfer of somatic motor nerves, such as the obturator nerve, to the distal ends of transected pelvic nerves. However, severing both pelvic nerves resulted in not only incontinence and urine retention but also severe UTIs and consequential death of most animals.

We explored transfer of somatic nerves to the vesical branch of the pelvic nerve in a series of studies in a canine model (Table 5).19, 34, 35 In an initial study using intercostal nerves as donor nerves in one dog,35 the immediate postoperative recovery was poor. We next examined the feasibility of transferring the ilioinguinal or iliohypogastric nerves, but each was too short to reach the bladder base. Therefore, we decided to transfer the genitofemoral nerve, a mixed sensory and motor nerve, to the anterior vesical branch of the pelvic nerve (transected between the pelvic plexus and the bladder dome) in two intra-abdominal surgical conditions (Figure 6b): transection of the dorsal and ventral sacral roots within the spine followed by immediate transfer versus transection followed by a 1-month or 3-month delay before transfer.34, 35 NCEs were implanted bilaterally in 2 of the 4 dogs with immediately GFNT and in all the dogs with 1month (n=4) and 3months (n=6) delay GFNT. At 32–138 days after surgery (mean 66 days), evidence of reinnervation included increased bladder pressure and urethral fluid flow after FES of the NCEs implanted on 2 of the 4 the immediately transferred nerves, and of four out of 20 NCEs implanted on the nerves that were transferred after a delay. At the time of the terminal surgery, direct bilateral FES of the transferred nerve immediately proximal to the repair site induced bladder pressure and urethral fluid flow in three of four animals with immediate transfer, in three of four animals with a 1-month delay before transfer, and in five of six animals with a 3-month delay before transfer. Three weeks after injection of the fluorogold into the bladders for retrograde dye tracing, abundant retrograde transport of fluorogold to motor neurons in the upper lumbar cord was observed in three of four dogs with immediate transfer, and in all 10 animals that underwent delayed transfer, except unilaterally in one animal. Histochemical evidence of nerve regrowth across the repair site,34, 35 and anterograde axonal tracing, further confirmed regrowth of axons from the transferred genitofemoral nerve into the bladder detrusor muscle, resulting in successful bladder reinnervation in the majority of animals in all groups.

This surgical procedure, in which somatic nerves are transferred to pelvic nerves, might enable restoration of bladder function (specifically emptying) in a subset of patients who can still control their lower abdominal musculature (for example, patients with caudal SCI or isolated injury to bladder nerves). Following the transfer procedure, prolonged activation of the lower abdominal muscles could be used to stimulate initiation of a micturition reflex, supplying the sustained input signal required by the detrusor. The patient could be trained to activate this reflex; however, it might be activated unintentionally in some circumstances, in which the intra-abdominal pressure is increased (such as, coughing fits or sneezing).

To address neurogenic sphincter incontinence, we performed pilot studies in cadavers and then in dogs to determine the feasibility of transferring femoral nerve motor branches to the pudendal nerve for re-establishment of EUS and anal sphincter function after sacral spinal cord or root injury (Table 5).18, 33 In the cadavers, we exposed branches of the femoral nerve to the vastus medialis and intermedialis muscles using an anterior thigh approach. Then, the pudendal nerve was exposed in the Alcock (pudendal) canal using a perineal approach, before transferring the femoral nerve branches medially and superiorly to the pudendal nerve.18

This study was then repeated in two canine cadavers, and in three live dogs.33 Sacral ventral roots were selected using intraoperative FES to demonstrate their ability to stimulate bladder, EUS and anal sphincter contraction. These roots were then transected to decentralize the end organs. Motor branches of the femoral nerve were identified bilaterally using an anterior thigh approach, then tunnelled to the perineum and sutured end-on-end to transected pudendal nerve branches located in the Alcock canal. The proximal portion of the transferred nerve was enclosed in NCEs. After surgery, FES was performed at monthly intervals. At 72 days, 120 days or 187 days, nerve stimulation induced increased anal and urethral sphincter pressures in five of six transferred nerves in three dogs. Retrograde neurotracing from the external urethral and anal sphincter resulted in labelled neurons in the ventral horns of L2–L4 cord segments (but not S1–S3), consistent with reinnervation of these structures by the transferred femoral nerve motor branches. By contrast, a non-operated control dog had labelled neurons only in S1 to S3 spinal cord segments Post-mortem neurotracing studies further confirmed axonal regrowth across the nerve repair site. Combined, these results indicate that return of EUS and anal sphincter function is possible using this femoral nerve-to-pudendal nerve approach.

We also explored the feasibility of translating similar somatic nerve-to-pelvic nerve transfer methods to human patients (Table 5).20, 21 In pilot studies in 20 cadavers (female or male), the intercostal, ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, and femoral nerves were exposed, carefully dissected to obtain the longest possible length, and then transected. These nerves, rather than the genitofemoral nerve, were chosen for transfer owing to their greater content of motor axons. First, the main branches of the vesical branches of the pelvic nerve were exposed in the pelvic cavity, and transected. The vesical branches of the pelvic nerve were detected as one or two main trunks at the base of the bladder, inferior to the ureter, and accompanied by inferior vesical vessels in all examined cadavers,20, 21 We first examined feasibility of transferring the eleventh and twelfth intercostal nerve directly to the vesical branch of the pelvic nerve , but both intercostal nerves were too short for this type of transfer. Therefore, use of a femoral cutaneous nerve branch as a nerve graft was suggested .20 Next, the use of ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves for transfer to pelvic nerves was explored in 11 cadavers . Each could be dissected from the abdominal wall with enough length to reach the bladder, before branching extensively to the abdominal muscles. They were transferred using an intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal approach to the main vesical branches of the pelvic nerve.20 Last, in 20 cadavers, a motor branch of the femoral nerve (which originates in L2–L4 ventral rami) was dissected using an anterior thigh approach . Two nerve branches to the vastus medialis and intermedialis muscles were split from the main trunk of the femoral nerve. They were transected with enough length to reach the interior of the pelvic cavity, and then moved superiorly and tunneled inferior to the inguinal ligament, before moving one branch to the ipsilateral vesical pelvic nerve at the base of the bladder and one branch to the contralateral vesical pelvic nerve.21 In all studies, the cross-sectional areas of each nerve were of sufficient and similar size for surgical coaptation.

These cadaveric studies show that the ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric and motor branches of the femoral nerve are candidates for transfer to the dominant (vesical) nerve branch of the pelvic nerve that innervates the bladder. However, further studies in animals, which are currently underway in our laboratories, or patients are required for confirmation.

Zhang and colleagues have published a summary of suggested procedures for bladder reinnervation using peripheral nerve rerouting. Specifically, they suggest isolating and rerouting intercostal nerves to sural nerves, and then connecting the intercostal–sural combination to the pudendal nerve.64 Unfortunately, no histological or functional outcome data showing evidence recovery was included in this or other reports from this group.64,65

Direct detrusor muscle reinnervation

In 1971, Rao and colleagues32 investigated the feasibility of direct reinnervation of the decentralized urinary bladder by transfer of suprasacral nerves (femoral and obturator nerve) to the detrusor muscle wall in animals (Figure 7, Table 5). Bladder decentralization was accomplished by bilateral pelvic nerve neurectomy in three of 15 dogs, intradural sacral rhizotomy of S2 and S3 roots in 12 dogs, and pelvic neurectomy in 80 rats. At 10 days after surgery, decentralization was confirmed using cystometrograms with bethanechol injections, and then either the obturator or femoral nerve was sectioned. The distal ends of these sectioned nerves were implanted directly into the detrusor muscle through a 1-cm-long intramuscular tunnel close to the ureterovesical junction. All dogs and 22 rats survived until the end of the study; the high mortality in the rats was due to severe UTIs. In six dogs at 8 weeks of recovery, the implanted nerves were still fixed to the bladder and had a normal appearance , although no bladder contractions were observed in response to stimulation of the implanted nerves. After an additional 12 weeks, the same six dogs were retested, but again no bladder contractions could be induced. The remaining nine dogs were tested at 30 weeks and 40 weeks after nerve transfer.. Action potentials were detectable in the regenerated nerve proximal to its entry into the bladder, although no increase in bladder pressure was observed. The results in the surviving 22 rats were similar to those seen in the latter nine dogs. In both dogs and rats, although neuromas had formed at the implantation site, there was little histological evidence that the growing axons entered the smooth muscle bundles of the bladder and no structures resembling myoneural junctions were visible.32 These results suggest that direct transfer and implantation of nerves into the bladder wall can result in nerve regeneration, but not restoration of bladder function.

Figure 7.

Direct detrusor muscle reinnervation by somatic nerve transfer.32 In a canine model, the bladder is decentralized by bilateral pelvic nerve neurectomy (1) or intradural sacral rhizotomy of S2 and S3 roots (2). 10 days later, either the obturator nerve (3) or femoral nerve (4) is sectioned and their distal ends implanted directly into the detrusor muscle close to the ureterovesical junction, using an arterial sleeve. Abbreviations: L, lumbar; S, sacral.

In summary, somatic nerves within the abdomen can also be coapted to the pelvic nerve in nerve transfer surgeries. However, use of the hypogastric nerve, a sympathetic autonomic nerve, has not proved successful in this type of surgery. The somatic nerve cross-over surgeries using genitofemoral nerve, motor branches of the femoral nerve, ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves would be limited to patients with a very caudal SCI or isolated injury to the nerves subserving bladder function unless FES is utilized, because the patient must have retained active control over lower abdominal musculature so that successful bladder emptying can be triggered by sustained activation of the abdominal musculature. Somatic nerves in the thigh region can also be coapted to the pudendal nerve, although further studies in animals or patients are required.

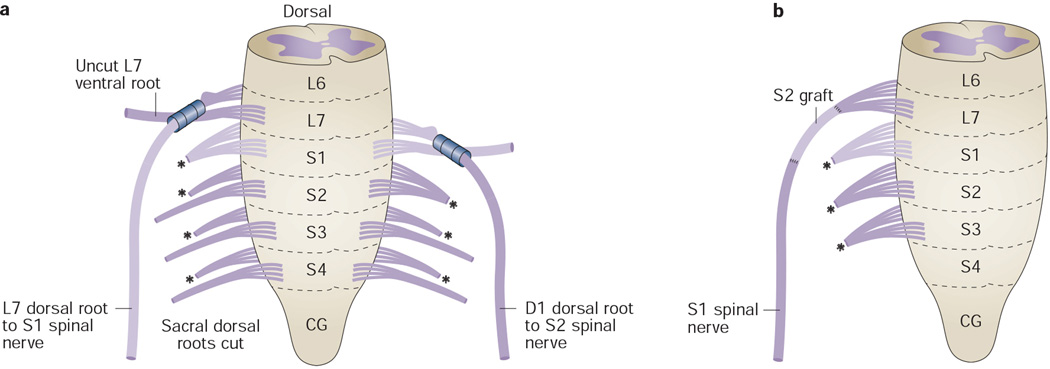

Artificial somatic-to-autonomic reflex pathway

Xiao et al. performed a series of studies with the goal of restoring the micturition reflex after SCI without the need for FES by creating an artificial reflex pathway via the central nervous system (CNS) (Figure 10, Table 6).43–47, 65 These investigators hypothesized that a skin–CNS–bladder pathway could be created by rerouting the efferent portion of a normal somatic reflex, for example, the patellar or Achilles66 reflex arcs. They believed a reflex circuit could be created that would enable bladder emptying in response to somatic sensory stimuli, by intradurally transferring the ventral root containing the somatic motor portion of the reflex arc to the ventral root that controls bladder emptying, while keeping the sensory portion of the somatic reflex arc intact (that is, the dorsal root). The success of this hypothetical model hinged on the ability of somatic motor nerve fibres to regenerate within an autonomic nerve.

Table 6.

Creation of an artificial skin–CNS–bladder pathway

| Study | Procedure | Functional recovery (time) |

Evidence | Limitations | Possible application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xiao et al. (1994) 65 |

L4 v → L6 v (L4 d intact) Intradural, unilateral Rat model |

Yes (3–12 months) |

Dorsal rhizotomy not required; Ipsilaterally, FES of sciatic nerve or scratching skin of legs induced bladder contraction |

Less promising results inpatients in other studies 67,68 |

SCI upper S segments and spina bifida |

| Xiao et al. (1999)43 |

L7 v → S1 v (L7 d intact) Intradural, unilateral Feline model |

Yes (3–7 months) |

Detrusor contractions induced by FES or scratching of the L7 dermatome;Voiding stimulated without detrusor–EUS dyssynergia |

Less promising results in patients in other studies 67,68 |

SCI upper S segments and spina bifida |

| Xiao et al. (2013)45 and Tuite et al. (2013)67 |

L5 v → S2 and S3 v L4 v → S2 v S1 v → S3 v Depending on level of injury; d roots intact Patients with SCI |

Yes (Xiao) (12–18 months) Not long-term (Tuite) |

Recovery of bladder storage and emptying |

Neuroma formation; little nerve growth across suture site, and recovery not long-term67 |

SCI in upper S segments |

| Lin et al. (2009)83 |

S1 v → S2 v (S1 d intact) Patients with SCI |

Yes (12 months) |

Elimination of detrusor– EUS dyssynergia; increased bladder capacity; decreased residual urine |

Recovery not long- term |

SCI in S segments below S1, or cauda equina |

| Xiao et al. (2005)46 and Peters et al. (2010)68 |

L5 v → S3 v Intradural, unilateral Children with spina bifida |

Yes (6–24 months) |

Increased bladder capacity and decreased residual urine (Xiao) Increased bladder pressure with stimulation of related dermatome; increased bowel function (Peters) |

No patient completely continent of urine;68 Partial loss of motor function in lower limb in 1 patient68 (Peters) |

Spina bifida |

Abbreviations: →, transfer to; d, dorsal; EUS, external urethral sphincter; FES, functional electrical stimulation; L, lumbar; S, sacral; SCI, spinal cord injury; v, ventral.

To test their hypothesis, they first explored this surgical method in 24 rats.44 First, all rats received a left hemilaminectomy to expose the spinal cord from L4 to S1, followed by transection of the ventral roots of these segments. Then, the proximal end of the L4 ventral root was transferred to the distal end of the L6 ventral root, while the L4 dorsal root was kept intact. At 3 months and 1 year after surgery, a strong bladder contraction could be initiated by FES of the left L4 ventral roots. In addition, at 1 year after surgery, bladder contractions were also observed after FES of the left sciatic nerves and by scratching the skin of the rats’ left legs (the dermatome related to L4). Neural tract tracing studies 3 months after nerve transfer indicated successful regeneration of the L4 ventral root axons into the ventral root of L6. The researchers concluded that this procedure was practical in rats and might have potential clinical application.44

In a subsequent study, the team tested a similar method in cats (Table 6).43 In six animals, the left L7 ventral root was intradurally transferred and sutured to the left S1 ventral root. For triggering the micturition reflex, the left L7 dorsal root was left intact to conduct afferent signals from the skin innervated by L7. At 11 weeks after operation, detrusor contractions of short latency could be induced after scratching or percutaneous electrical stimulation of the dermatome related to L7. FES of the L7 nerve also increased bladder pressure. Urodynamic studies demonstrated that voiding could be stimulated without generating detrusor–EUS dyssynergia. Skin-stimulated bladder contractions were reduced after administration of the antimuscarinic agent atropine or the ganglion-blocking agent trimethaphan. Thus, the researchers could demonstrate that the skin–CNS–bladder reflex arc of L7 to S1 could effectively induce detrusor muscle contractions after bladder decentralization, that the new pathway was mediated by cholinergic transmission involving both muscarinic and ganglionic nicotinic receptors, and that somatic motor axons could innervate bladder parasympathetic ganglion cells and thereby transfer somatic reflex activity to the bladder smooth muscle, resulting in bladder contractions.43

In 2003, Xiao and colleagues45 published the results of the first clinical study of the skin–CNS–bladder procedure (Figure 8, Table 6). 15 male patients with hyperreflexic NBD caused by complete suprasacral SCI volunteered for this study. Bladder function was evaluated preoperatively using urodynamic methods, which showed that each subject had hyperreflexic bladders with detrusor–sphincter dyssynergia. All patients underwent a limited hemilaminectomy from L4 to S3. The dura was opened to expose the dorsal and ventral roots from L5 to S3. The ventral roots of L5, S2 and S3 were identified, separated from their respective dorsal roots by microdissection, and their function tested by FES before sectioning. Then, the proximal end of the L5 ventral root was sutured to the distal end of the S2 ventral root. The technique was modified as needed based on the length and function of the roots, and extent of cord damage (for example, transfer of the L5 ventral root to S2 and S3 ventral roots, or L4 or S1 ventral roots to S2 or S3 ventral roots). At 12–18 months after surgery, 10 patients (66%) recovered bladder storage and emptying functions. After 1 year, they were able to initiate voiding using the skin–CNS–bladder reflex pathway of L5 to S2. Their average residual urine was markedly decreased (from 332 ml to 31 ml), and UTIs and overflow incontinence ceased. Two patients had no improvement with surgery, one was lost to follow-up and two only had a partial reflex, which required them to electrically stimulate the sensory dermatome to initiate voiding.45 These findings suggest that a somatic to autonomic reflex arc can be established via an intradural nerve transfer procedure, resulting in voluntary voiding, improvement of detrusor–sphincter dyssynergia, and increased bladder capacity. Xiao and colleagues proposed this method as an effective technique for restoring bladder function in patients with suprasacral SCI.

Figure 8.

Artificial skin–CNS–bladder reflex pathway methods.43–47. After hemilaminectomy from L4–S3, the dorsal and ventral roots from L5–S3 are exposed, the ventral roots of L5 and S2 separated from their respective dorsal roots and sectioned. Then, the proximal end of the L5 ventral root is sutured to the distal end of the S2 ventral root in human subjects. Variations included transfer of the L4 to L6 ventral roots, L5 ventral root to S3 ventral roots, L7 to S1 ventral roots, or S1 to S1 and/or S2 ventral roots. Abbreviations: CG, coccygeal; CNS, central nervous system; L, lumbar; S, sacral. Not sure why some changes were made - are you, the editor intending to focus on human only? I added human and animal subject variations (Barbe)

In 2009, Lin and colleagues66 published the results of a confirmatory clinical study, using a slight variation on the Xiao procedure. 12 paraplegic patients with hyperreflexic NBD and detrusor–EUS dyssynergia caused by complete suprasacral SCI underwent an intradural transfer of S1 to S2 ventral roots, leaving the S1 dorsal root intact. The investigators chose the S1 nerve root instead of the L5 root to enable initiation of the somatic–CNS–autonomic reflex by tapping on the Achilles tendon in addition to skin stimulation, creating an Achilles tendon-to-bladder reflex pathway. Nine patients (75%) regained bladder control within 6–12 months after surgery. Urodynamic testing of these nine patients around 1 year after operation showed elimination of detrusor–sphincter dyssynergia, increased bladder capacity (258 ml to 350 ml) and decreased residual urine (214 ml to 45 ml). The remaining three patients showed no improvement after surgery.

Tuite and colleagues67 performed the Xiao procedure in a 10-year-old boy with chronic T10–T11 paraplegia under the direct supervision of C. G. Xiao, but failed to reproduce previously reported results (Table 6). The L5 ventral root was transferred intradurally to the S2 and S3 nerve roots, leaving the L5 dorsal root intact. At 6–12 months after surgery, the patient reported improvement in his ability to control his voiding. However, by 24 months, he felt that he had no improvement in bladder or bowel control compared to his condition before surgery. During urodynamic testing, voiding and bladder contractions could not be consistently initiated after stimulating the L5 dermatome. When a separate lumbosacral intradural procedure was performed 3 years later, the previously performed L5 to S2-S3 transfer was found to be anatomically intact. However, FES proximal and distal to the repair site produced no bladder contractions, and nerve action potentials could not be demonstrated across the repair site. Histological analysis showed neuroma formation with very little nerve growth across the repair site. As reinnervation was not evident, the patient’s transient improvements in bladder control were not related to a functional skin–CNS–bladder reflex.

Xiao and colleagues46 also used the Xiao procedure as a treatment for neurogenic voiding dysfunction in 20 children with spina bifida and documented NBD (Table 6). In each child, the spinal defect had been surgically closed within the first 48 h after birth. Preoperative urodynamic studies showed two types of bladder dysfunction. 14 patients had an areflexic detrusor with small bladder capacity and incontinence—findings typical of a lower motor neuron lesion. The other six patients had hyperreflexic bladders with detrusor–EUS dyssynergia and overflow incontinence—findings typical of an upper motor neuron lesion. A limited laminectomy was performed between L4 and S2 vertebrae, followed by exposure of the dorsal and ventral roots of L4 and L5 and all sacral segments. The ventral roots of L4, L5, S2 and S3 segments were microdissected from their respective dorsal nerve roots, and the proximal end of the L5 ventral root was sutured to the distal end of the S3 ventral root, leaving the L5 dorsal root intact. As early as 6 months after surgery, 17 patients were able to initiate voiding and had regained continence, but the three remaining patients failed to show any improvement. All 14 patients that had initially presented with urological signs of a lower motor neuron lesion showed increased bladder capacity and decreased residual urine in urodynamic studies at 1 year after operation. Five of the six patients that presented with urological signs of an upper motor neuron lesion were able to void voluntarily, had decreased detrusor pressure and residual urine, and increased bladder capacity by 9 months after surgery.46 These results provide clinical evidence that somatic motor axons can grow into autonomic nerves, and that an artificial skin-to-bladder reflex pathway can be established in patients with SCI and spina bifida.

In 2010, Peters and colleagues68 reported the results of a similar study in children with spina bifida (Table 6). Nine patients with NBD related to spina bifida underwent the Xiao procedure, with Xiao directly participating in the surgeries. By 1 year after surgery, seven patients (78%) had a reproducible increase in bladder pressure during urodynamic testing with stimulation of the dermatome related to the nerve root used for coaptation. No patient was completely continent of urine, but the majority reported improved bowel function. As a result of the operation, one patient had a persistent foot drop at 1 year after surgery. Because these 1-year results68 were not as encouraging as those reported by Xiao et al.,45, 46, 66 more studies and longer follow-up periods were recommended by the authors.68

In summary, the Xiao procedure, in which efferent portions of a normal somatic reflex, such as the patellar or Achilles reflex arcs, are rerouted to motor nerves involved in autonomic bladder function was successful in some studies,45, 46, 66 but disappointing in others,68 particularly when success was evaluated after >2 years after surgery.67

Of note, the study in the neurally intact cat43 should be repeated in both neurally intact and spinal-transected cats to mimic the clinical state of human patients for which this surgery is intended. It is well known that, following spinal cord transection, spinal reflexes below the transection become hyperactive. Thus, control groups of spinal-transected animals with sham nerve transfer need to be studied to determine whether these hyperactive reflexes initiate micturition following dermatome scratching or FES even in the absence of nerve transfer. Ideally, the researchers performing the urodynamic examination of the cats following the surgery should be unaware of the type of surgery the cats had received.

Alternative management of NBD

Application of FES

FES describes the use of electrical current in excitable tissue to supplement or replace functions that have been lost in neurological injuries and assist or substitute an individual’s voluntary ability. In general, activation of neuromuscular tissue requires at least two electrodes, placed near the peripheral nerve to be stimulated, to enable current flow. A localized electric field is established, which depolarizes the cell membranes of adjacent nerves, followed by an increased influx of extracellular sodium ions into the intracellular space generating action potentials.69 To generate muscle contraction, the stimulus has to be applied along the length of the peripheral nerve, but not to the muscle itself. The number of nerve fibres that become activated and the force of the muscle contraction is determined by the strength of the electrical stimulus (amplitude and duration). In addition, the pulse frequency and waveform are important. To activate small-diameter, high-threshold autonomic nerves and generate contraction of a smooth muscle, the pulse amplitude has to be considerably higher than the amplitude required for activation of large-diameter, low-threshold motor axons that innervate striated muscle. The pulse height needs to be enough to generate a smooth muscle contraction. The stimulus itself can be monophasic or biphasic, but in the clinical setting, a balanced biphasic stimulus usually enables better control of the force of the muscle contraction and is less likely to cause tissue damage.70 A balanced biphasic stimulus consist of a cathodic phase, in which the action potentials are initiated and the neural reaction is elicited, followed by an anodic phase that cancels the accumulated charge on the electrode and prevents electrolysis with dissolution of the electrode and tissue damage.71

Finetech-Brindley FES system

Spinal cord simulation for NBD treatment is based on unexpected observations following spinal cord stimulation to control pain in patients with multiple sclerosis 72. Stimulation of the cord region that contains the micturition centre generated not only contraction of the detrusor muscle, but also contraction of the urethral sphincter, increasing outflow resistance and inhibiting voiding.73 Based on these findings, an implantable device with tripolar electrodes, wires and a receiver generator controlled and powered by an external portable unit was developed.74 The device could be programmed to generate a strong contraction of both detrusor muscle and striated muscle of the urethra, followed by a sphincter fatigue while the detrusor muscle was still contracting, resulting in effective voiding immediately after cessation of stimulation.74

Multiple studies of selective FES of sacral roots have been performed in dogs.73, 75–77 The results of these studies indicate that unwanted spinal reflexes that facilitate pain and sphincter contraction during stimulation are greatly diminished after dorsal root rhizotomy.76 In addition, because voiding is controlled by both parasympathetic preganglionic neurons controlling the bladder and somatic motor neurons controlling the sphincter, pudendal neurotomy, in combination with dorsal rhizotomy, can eliminate neural influences on the sphincter, producing more efficient micturition in response to FES of ventral roots.77