Abstract

Background

Many MSM acquire HIV while in a same-sex relationship. Studies with gay male couples have demonstrated that relationship characteristics and testing behaviors are important to examine for HIV prevention. Recently, an in-home rapid HIV test (HT) has become available for purchase in the US. However, HIV-negative partnered men’s attitudes toward using an HT, and whether characteristics of their relationship affect their use of HTs remain largely unknown. This information is relevant for development of HIV prevention interventions targeting at-risk HIV-negative and discordant male couples.

Methods

To assess HIV-negative partnered men’s attitudes and associated factors toward using an HT, a cross-sectional Internet-based survey was used to collect dyadic data from a national sample of 275 HIV-negative and 58 HIV-discordant gay male couples. Multivariate multilevel modeling was used to identify behavioral and relationship factors associated with 631 HIV-negative partnered men’s attitudes toward using an HT.

Results

HIV-negative partnered men were “very likely” to use an HT. More positive attitudes toward using an HT were associated with being in a relationship of mixed or nonwhite race and with one or both men recently having had sex with a casual male partner. Less positive attitudes toward using an HT were associated with both partners being well educated, with greater resources (investment size) in the relationship, and with one or both men having a primary care provider.

Conclusions

These findings may be used to help improve testing rates via promotion of HTs among gay male couples.

Keywords: gay male couples, MSM, in-home rapid HIV test (HT), relationship characteristics

INTRODUCTION

As HIV rates among men who have sex with men (MSM) continue to increase in the US [1], additional prevention efforts are needed to avert new infections. HIV testing is and remains an essential cornerstone component for HIV prevention and, to access treatment and care. One of the primary goals of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy of the US is to increase the percentage of persons who are aware of their HIV-positive serostatus [2]. People who know they are HIV-positive engage in less risky sexual behaviors compared to those who are unaware [3, 4]. Early initiation of treatment can also improve treatment outcomes [5–7] and decrease the viral reservoir [8].

The CDC recommends annual HIV testing for men who have same-sex partners, with more regular testing (every 3 to 6 months) for those with identifiable risk factors (e.g., using substances, having multiple or anonymous sex partners) [9]. Moreover, between one-third and two-thirds of HIV infections among US MSM are transmitted within same-sex primary relationships (i.e., male couples) [10, 11]. Given these estimates, recent attention has focused on studying the dynamics and behaviors of gay male couples’ relationships, including their HIV testing rates and interest in using newer testing methods.

HIV testing rates among HIV-negative men in concordantly negative and discordant same-sex relationships remain low in the US [12–15], although men are more likely to have unprotected anal sex (UAS) with main partners [14, 16, 17]. The few studies that have assessed male couples’ testing behaviors indicate their testing rates vary considerably in light of UAS being practiced within and/or outside the relationship. A US study with HIV-negative partnered MSM who had engaged in UAS within and outside of their relationships noted that 31% would only test if they felt they were at-risk, 33% would test approximately once a year, and 6% of the men reported they would test every 3-4 months [14]. A different study with a similar population found that 25% of men who recently engaged in UAS with an outside partner of discordant or unknown serostatus had been tested within the previous three months and 60% had been tested within the past year [13]. A study with HIV-negative gay couples noted that men who recently tested for HIV (e.g., < 3 months) were more likely to have had UAS with a casual MSM partner during the same timeframe, suggesting that these men might have been aware of their risk for acquiring HIV and were using testing as an approach to harm-reduction [12]. In a separate study, men who believed their primary male partners had recently tested for HIV were more likely to have had UAS within and outside of their relationship [17].

Couples-based HIV testing and counseling (CHTC) and over-the-counter in home testing (HT) are newer modes of HIV testing. During CHTC, male couples participate in the whole cycle of testing together, which includes receiving pretest information, counseling and risk assessment, results from the test(s), and post-test counseling, together [18]. CHTC has been found to be acceptable in surveys of MSM in the US [19] and abroad [20, 21]. In a nation-wide dyadic study with 275 HIV-negative male couples, findings revealed couples were “somewhat” to “very likely” to use CHCT; positive attitudes toward using this service were associated higher levels of relationship satisfaction and commitment toward their sexual agreement, and among those who had at least one partner having had sex outside of the relationship [22]. In that study, less positive attitudes toward using CHTC were observed in couples who had higher levels of trust toward their partners.

HT provides an additional method for single and partnered MSM to test for HIV, but in the comfort of their home or another private setting. Recent studies have examined men’s willingness to use an HT, whether they would use an HT to screen potential sexual partners, and how their use of an HT impacts their engagement in UAS, and changes in their attitudes and behaviors related to sexual risk for HIV infection [23–29]. In one US study prior to HT becoming available for over-the-counter sale, over 80% of MSM said they would use a HT to self-test themselves and/or sexual partners [25]. Research conducted in Australia, England and France also found MSM to have a high interest in using an HT [23, 24, 26].

Research has assessed whether the use of an HT would alter sexual behaviors, in particular engagement in UAS. In a study with 27 MSM who regularly engage in UAS, men were given 16 HT kits to use over a 3-month period; in seven occasions where a potential sexual partner received a positive test result, the sexual encounter ended [27]. Many participants experienced potential sexual partners refusing to take an HT, which resulted in more than 50% of the sexual encounters ending [27]. In total, participants reported 10 positive test results: 6 were unaware of their positive serostatus, 7 were potential sex partners, and 3 were acquaintances of the study participants [28]. For some participants, the use of an HT to screen potential sex partners helped to heighten their awareness of, and commitment to, reducing their risk for HIV [29]. The men also reported being able to use the HT in both private and public spaces with little to no problems, and had a strong desire to continue to use HTs with a willingness to buy them [28].

While much is known about MSM’s use of an HT, little is known about male couples’ attitudes toward using an HT. The present study sought to help fill this knowledge gap by using dyadic data collected in 2011 from a nation-wide US Internet study with 333 male couples comprised of 275 HIV-negative and 58 HIV-discordant dyads. Our aims are to describe 631 HIV-negative partnered men’s attitudes toward using an HT, and to assess which within and between couple-level factors are associated with their attitudes towards HT. Between couple-level factors pertain to characteristics of the couple that are used to compare to other couples, such as whether one or both men are employed in the relationship compared to couples where neither partner is employed. Within couple-level factors indicate the difference in reported scores between two partners of the couple, such as how their satisfaction level with being in the relationship may differ from one another.

METHODS

Protocol

The BLINDED Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. Recruitment for this study sample was conducted through Facebook banner advertising; methods have been previously described [blinded refs]. In 2011, advertisements targeted partnered men who reported in their Facebook profile being ≥ 18 years of age, living in the US, interested in men, and being in a relationship, engaged, or married. Banner advertisements briefly described the purpose of the study and included a picture of a male couple. Of a total of 7,994 Facebook users who clicked on an advertisement, 4,056 (51%) answered eligibility questions; 722 (18%), representing both men of 361 MSM couples provided consent and completed the original study questionnaire. A total of 606 HIV-negative and 25 unknown serostatus MSM, representing 275 concordantly negative and 58 HIV-discordant male couples (N = 333 dyads), are included in this analysis; 28 concordant HIV-positive male couples were excluded from the present analysis. Men were eligible to participate if they: were ≥18 years of age; lived in the U.S.; were in a sexual relationship with another male; and reported oral and/or anal sex with this partner within the previous three months.

A referral system was embedded in the survey to enable data collection from both primary partners in the couple. Post-hoc analyses of response consistency were used to verify couples’ relationships. Every fifth couple that completed the survey was modestly compensated.

Measures

Outcome variable

Participants’ attitudes toward use of a home-based rapid HIV test (HT) were assessed by 1-item with a 5-point Likert-type scale that had response options ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely likely). Participants were asked"Hypothetically, if the following service became readily available, how likely would you use a rapid HIV test at home if it provided your test result within 20 minutes?”

Independent Variables

Demographic factors, relationship characteristics, and sexual and drug use related behaviors were assessed. Men self-reported their perceived HIV status, their primary partner’s perceived HIV status, UAS within the relationship (e.g., with main partners), sex with any casual MSM partners in the past three months and, if so, whether they had UAS. Participants reported whether they used any substances during or before sex within and/or outside of their relationship within the three months prior to assessment. Relationship characteristics assessed were relationship and cohabitation length, and validated scales regarding participant’s level of trust [30] and relationship commitment [31]. Details about these validated scales have been reported elsewhere [15].

Data analysis

Dyadic data from 333 dyads with 631 HIV-negative partnered men were analyzed using Stata v12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) following guidelines provided by Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal [32]. Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, rates, and percentages were calculated, as appropriate, for measures. To assess how couple-level factors may affect participants’ attitudes towards HT use, we examined a variety of couple-level demographic, behavioral and relationship characteristics, including relationship commitment and trust. These particular relationship characteristics were chosen because prior research has identified these factors to be associated with gay male couples’ attitudes toward using other testing options (e.g., CHTC) and HIV risk. Relationship characteristics of commitment and trust were assessed in two ways at the couple-level. The average of both partners’ scores on each relationship factor were calculated and then entered into a multilevel regression model to assess differences that existed between couples in the sample regarding participants’ attitudes toward use of an HT. The absolute difference between the two partners’ scores for each of the relationship factors was also calculated to examine differences that existed within couples with respect to participants’ attitudes toward use of an HT.

Independent couple-level variables that were significantly (P < 0.05) associated with outcomes in bivariate analyses were included in a multivariate random-effects multilevel regression model with maximum likelihood estimation. For the final model, we used backward elimination to remove independent variables that remained non-significant until all variables, excluding the pre-determined confounders, remained significant. We included couples’ age (i.e., difference between partners), HIV-status, and relationship duration as potential confounders for the model. We report the coefficients, standard errors, and statistical significance for the factors in the bivariate and multivariate models.

RESULTS

The average age of men was 32.2 years; the average age difference between partners was 4.9 years (Table 1). Couples’ relationship length averaged nearly 5 years. About a third of couples were nonwhite or mixed race; another third had both partners who earned at least a Bachelor’s degree. Most couples reported being employed, having at least one partner with a primary care provider (PCP), being concordantly HIV-negative, and living together. Partners were, on average, committed to their relationship and trusting of one another. Within couple-level relationship characteristics (i.e., differences in partners’ scores on trust and commitment level) indicated both partners of the couple reported similar scores, with few factors having a range greater than one between partners.

Table 1.

Characteristics 275 HIV negative concordant and 58 HIV discordant gay male couples recruited online, United States, 2011.

| Couple-level demographic characteristic | % (N = 333 dyads) |

|---|---|

| YMSM: One or both men were 29 years or younger | 57% (190) |

| HIV status of relationship | |

| In HIV discordant relationship | 17% (58) |

| In concordantly HIV negative relationship | 83% (275) |

| Mixed or nonwhite race | 34% (113) |

| Education level: Both men had at least a Bachelor’s degree | 34% (112) |

| Employment status: Both men employed | 66% (220) |

| Had primary care provider: One or both men reported yes | 61% (203) |

| Establishment of sexual agreement: Both men concurred yes | 51% (171) |

| Geographical location: Urban / suburban | 88% (279) |

| US region a | |

| West | 30% (201) |

| Midwest | 25% (163) |

| South | 28% (186) |

| Northeast | 17% (116) |

| Mean (SD) | |

| Age difference between partners | 4.9 (5.7) |

| Individual age [range: 18 – 68 years] | 32.2 (10.6) |

| Relationship length [range: 0.25 – 35 years] | 4.8 (5.4) |

| Cohabitation length [range: 0.08 – 31.7 years] b | 5.0 (5.7) |

| Between couple-level relationship characteristicc | Mean (SD) |

| Investment model for relationship commitment [range: 0 – 6] | |

| Commitment level | 5.40 (0.67) |

| Satisfaction | 4.92 (0.88) |

| Investment size d | 4.72 (0.81) |

| Quality of alternatives d | 3.72 (1.07) |

| Trust scale [range: 0 – 6] | |

| Dependability | 5.61 (0.83) |

| Faith | 6.03 (0.80) |

| Predictability | 5.33 (0.96) |

| Within couple-level relationship characteristicc | Mean (SD) |

| Investment model for relationship commitment | |

| Commitment level | 0.69 (0.79) |

| Satisfaction | 0.95 (0.89) |

| Investment size d | 0.93 (0.75) |

| Quality of alternatives d | 1.15 (1.02) |

| Trust scale | |

| Dependability | 1.03 (0.87) |

| Faith | 0.88 (0.81) |

| Predictability | 1.07 (0.85) |

Note

Regional data represent the individual men because not all couples reported living together.

Data represents participants who reported living with their main partner for at least one month or longer.

Between couple-level relationship characteristics represent the average of both partners responses to a factor whereas within couple-level relationship characteristics represent the absolute difference between partners’ responses to a factor.

Investment size refers to the existence of concrete or tangible resources in the relationship that would be lost or greatly reduced if the relationship ends. Quality of alternatives is the perception that being single or an attractive alternative partner existed outside of the main relationship, and that this alternative would provide superior outcomes when compared with the current relationship.

Most couples practiced UAS within their relationship (Table 2). About a third of couples had one or both partners who had sex outside of the relationship. Of these, 63% had one or both partners who had UAS with a casual partner and 53% had one or both partners who had UAS within and outside of their relationship. Some male couples had one or both partners who reported using substances with sex. Alcohol, marijuana, and erectile dysfunction medication (EDM) were the three most commonly reported substances used within couples’ relationships. Alcohol, amyl nitrates, and EDM were the three most commonly reported substances used with sex outside of couples’ relationships.

Table 2.

Behaviors of 275 HIV negative concordant and 58 HIV discordant gay male couples recruited online, United States, 2011.

| Couple-level sexual behavior | % (N = 333 dyads) |

|---|---|

| UAS practiced within relationship | 83% (278) |

| Sex outside of relationship | 30% (101) |

| UAS outside of relationship a | 63% (64) |

| UAS within & out of relationship a | 53% (54) |

| Couple-level substance use with sex – main partner | % (N = 333 dyads) |

| Party drugs b | 11% (35) |

| EDM c | 18% (61) |

| Amyl nitrate (e.g., poppers) | 14% (46) |

| Marijuana | 30% (101) |

| Alcohol | 83% (278) |

| Couple-level substance use with sex – casual partner | % (N = 333 dyads) |

| Party drugs b | 3% (11) |

| EDM c | 9% (30) |

| Amyl nitrate (e.g., poppers) | 10% (32) |

| Marijuana | 8% (28) |

| Alcohol | 17% (58) |

Notes.

With the exception of UAS practiced within the relationship, all reported behaviors include male couples in which one or both men in the relationship self-reported `engaging in that behavior (e.g., amyl nitrate with sex – main partner).

Data reflects among the couples who had one or both partners that had sex outside of their relationship.

Party drugs include ecstasy, ketamine, GHB, cocaine, and methamphetamine.

EDM represents erectile dysfunction medication.

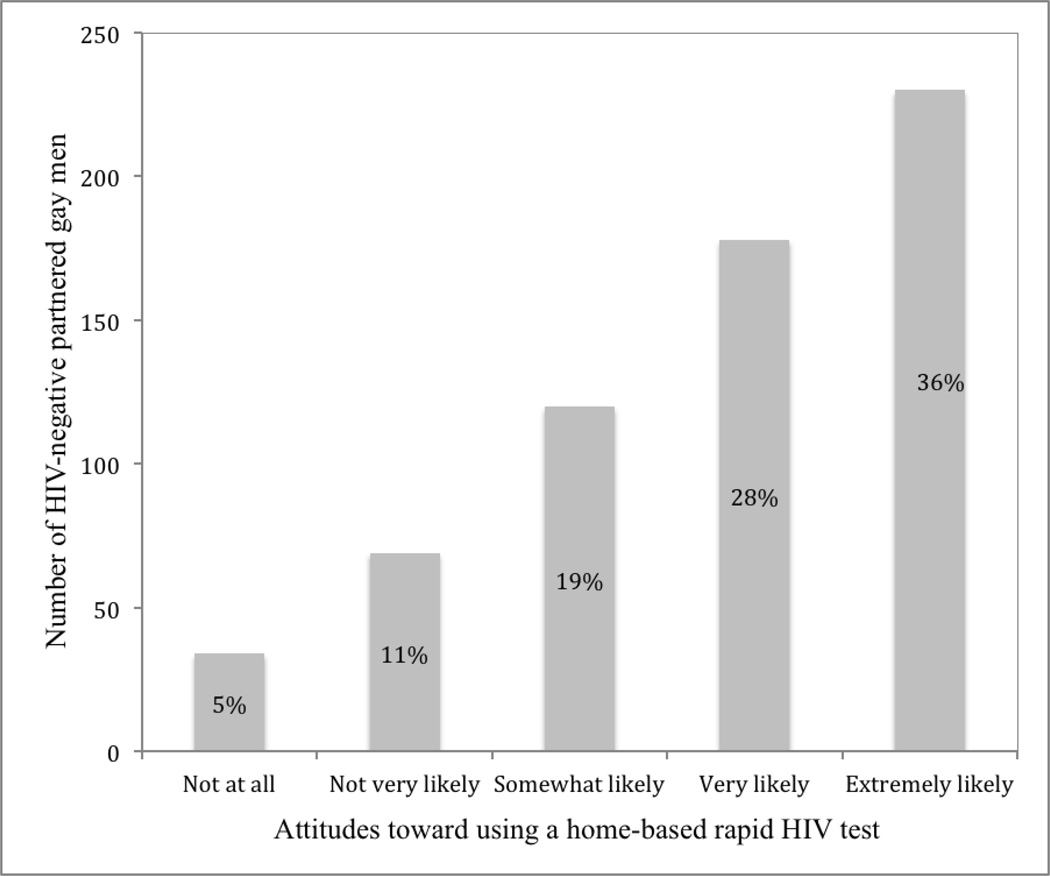

Most HIV-negative partnered men were likely or extremely likely to use an HT; the modal response was extremely likely (36%; Figure 1). The average reported attitude toward using an HT was 2.8 (SD 1.2).

Figure 1.

HIV-negative partnered gay men’s attitude toward using a home-based rapid HIV test

Bivariate and final multivariate random-effects multilevel regression models are illustrated in Table 3. In bivariate analyses, more positive attitudes toward HT use were associated with having an HIV-positive partner, being in a mixed-race relationship, being in a couple where one or both partners also had casual sex partners, and being in a couple where UAS was practiced by one or both partners both within and outside the relationship. More positive attitudes toward using an HT were also associated with using party drugs or using marijuana during sex with the main partner. Less positive attitudes toward using an HT were associated with being in a couple where both partners had at least Bachelor’s degree; couples where at least one partner having a primary care provider; and greater resources (i.e., investment size) in the relationship.

Table 3.

Factors significantly associated with attitude toward use of an HT among 631 HIV-negative partnered gay men in 275 HIV-negative and 58 HIV-discordant male couples: Results from bivariate and final multivariate random-effects multilevel regression models

| Bivariate models |

Final multivariate model |

|

|---|---|---|

| Couple-level demographic | β(SE) | β(SE) |

| Relationship length | ||

| 5 years and less (ref) | 0.21 (0.12) | 0.11 (0.12) |

| Greater than 5 years | ||

| Age difference between partners | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) |

| HIV status of relationship | ||

| Discordant (ref) | 0.16 (0.08)* | 0.12 (0.08) |

| Negative concordant | ||

| Race | ||

| Mixed or nonwhite (ref) | 0.32 (0.11)** | 0.27 (0.11)* |

| White | ||

| Education level | ||

| Both men had Bachelor’s or higher degree (ref) | −0.31 (0.11)** | −0.26 (0.11)* |

| One or neither partner had a Bachelor’s degree | ||

| Has primary care provider | ||

| One or both men reported yes (ref) | −0.27 (0.11)* | −0.25 (0.11)* |

| Both partners reported no | ||

| Couple-level sexual behavior | β(SE) | β(SE) |

| Sex outside of relationship | ||

| One or both men reported yes (ref) | 0.40 (0.11)*** | 0.49 (0.11)*** |

| Both partners reported no | ||

| UAS within and outside of relationship | ||

| One or both men reported yes (ref) | 0.36 (0.14)* | -- |

| Both partners reported no | ||

| Couple-level substance use with sex – main partner | β(SE) | β(SE) |

| Party drugs a | ||

| One or both men reported yes (ref) | 0.40 (0.18)* | -- |

| Both partners reported no | ||

| Marijuana | ||

| One or both men reported yes (ref) | 0.26 (0.12)* | -- |

| Both partners reported no | ||

| Couple-level relationship characteristic | β(SE) | β(SE) |

| Investment model for relationship commitment | ||

| Investment size – between couples b | −0.25 (0.07)*** | −0.24 (0.07)*** |

Notes.

Results from final random-effects multilevel regression model controlled for couples’ relationship duration, HIV serostatus, and age difference between partners. 597 obs., 315 dyads, χ2 (8) = 56.43, P < 0.001, Log likelihood = −916.76

Party drugs include ecstasy, ketamine, GHB, cocaine, and methamphetamine.

Investment size refers to the existence of concrete or tangible resources in the relationship that would be lost or greatly reduced if the relationship ends.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001

The final random-effects multilevel regression model controlled for couples’ relationship length, HIV serostatus, and age difference between partners. In this model, more positive attitudes toward using an HT were associated with being in a mixed or nonwhite race relationship and being in a relationship where one or both men had recent casual sex partners. Less positive attitudes toward using an HT were associated with being in a relationship in which both partners having earned at least a Bachelor’s degree; in which one or both men had a primary care provider; and in which men reported greater investment size of resources.

DISCUSSION

Testing for HIV remains a critical first step to preventing new infections and among HIV-negative partnered men in HIV-negative concordant and HIV-discordant gay male couples’ relationships. The frequency that partnered men test for HIV remains low [12–15]. Given newer HIV testing options (e.g., CHTC and HT), it is important to understand the attitudes towards these testing modes and the characteristics of partnered gay men who could benefit from more frequent testing. Here, we assess and identify key behavioral and relationship factors associated with HIV-negative partnered men’s attitudes toward using an HT among a sample of 333 gay male couples. Most men in couples reported high interest in using an HT device.

Among HIV-negative partnered gay men, more positive attitudes toward using an HT were significantly associated with being in a mixed race or nonwhite relationship. Other studies have reported higher HIV testing rates among black and other non-white MSM [33]. Black and Hispanic MSM have higher prevalence of HIV than White men; increasing HIV testing rates for partnered gay men who are in a mixed race or nonwhite same-sex relationship is critical, and our data suggest that an HT may be an acceptable testing approach for such men. Some potential strategies may include using HTs as incentives for current and future research projects, including interventions and clinical trials, distribution of HT kits, and providing subsidies or vouchers for HT purchase [34]. Although prior research has indicated some racially and ethnically diverse MSM would be willing to pay for an HT, male couples’ willingness to pay for an HT has not been reported.

More positive attitudes toward using an HT were also associated with being in a non-monogamous relationship. Male couples with one or both men who had engaged in sex with an outside casual MSM partner could use an HT to help navigate choices they may make regarding sex, such as whether to engage in UAS with outside partners or one another. MSM who do not regularly use condoms for anal sex are interested in using HTs, feel comfortable screening potential sex partners with an HT and have encountered few problems with using this type of risk-reduction strategy to screen others and for deciding whether to have sex and/or use a condom for anal sex [26–28]. Using an HT to screen potential sex partners has had an added benefit of increasing men’s awareness about their risk for HIV, and to some degree altering their partner choices [29, 30]. It is possible that HIV-negative and HIV-discordant male couples who use a HT may have similar experiences; research that explores this possibility is warranted.

In contrast, less positive attitudes toward using an HT were associated with being well educated, access to a PCP, and greater investment in resources. Partnered gay men who have greater access to resources might prefer to use other HIV testing options, such as being tested directly by their PCP. Although we did not assess couples HIV testing preferences, we recommend that prevention programs offer multiple testing options for gay men and male couples. As prior HT studies with MSM have noted, most participants indicated they would be willing to use an HT and the availability of an HT would help them test for HIV more frequently [19–25].

Limitations

Our study had important limitations. The use of a cross-sectional study design with a US convenience sample does not allow for casual inference and these results cannot be generalized to all Internet-using US male couples or those who do not use Facebook. Although we did not collect identifying information, biases of participation, social desirability, and recall may have influenced participants to inaccurately self-report information about their HIV status and risky behaviors. The factors we assessed for association with attitudes toward using an HT were not exhaustive. Additional research should explore how other factors could affect male couples’ use of a HT, including their mental health, presence or history of intimate partner violence, knowledge of HIV transmission related behaviors, and perceived risk for acquiring HIV. Future studies may benefit from the inclusion of these limitations to assess male couples’ willingness to use a HT to help increase HIV testing rates.

Our results have several implications for public health practice and research. First, there are existing at-home test distribution programs (e.g., www.itestathome.org) and research studies of at-home test kit distribution [35]. These efforts should take steps to assess the extent to which men in couples are using at-home test kits. Further, our data on factors associated with willingness to use HT kits can be used by health departments, community-based organizations, and other HIV testing providers to target kit distribution programs.

SUMMARY.

This study presents findings in support of promoting in-home rapid HIV tests (HT) to at-risk gay male couples who are of mixed or nonwhite race and/or behaviorally non-monogamous.

Acknowledgments

Data collection for this manuscript was supported by the center (P30-MH52776; PI J. Kelly) and NRSA (T32-MH19985; PI S. Pinkerton) grants from the National Institute of Mental Health. This work was facilitated by the Center for AIDS Research at Emory University (P30AI050409).

Footnotes

No financial or ethical conflicts of interest exist among the authors for the present study.

REFERENCES

- 1.CDC. HIV incidence. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated on May 22, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/surveillance/incidence/index.html.

- 2.Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States. 2010 Available from: www.whitehouse.gov/onap.

- 3.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, et al. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: Implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from person aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS. 2006;20(10):1447–1450. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000233579.79714.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG, et al. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1815–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DHHS. HIV treatment guidelines. 2014 Available from: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines.

- 7.Okulicz JF, Le TD, Agan BK, et al. Influence of the timing of antiretroviral therapy on the potential for normalization of immune status in human immunodeficiency virus 1-infected individuals. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4010. ePub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ananworanich J, Schuetz A, Vandergeeten C, et al. Impact of multi-targeted antiretroviral treatment on gut T cell depletion and HIV reservoir seeding during acute HIV infection. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC. Gay and bisexual men’s health – HIV/AIDS. [Updated on November 26, 2013];Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/msmhealth/HIV.htm.

- 10.Sullivan PS, Salazar L, Buchbinder S, et al. Estimating the proportion of HIV transmissions from main sex partners among men who have sex with men in five US cities. AIDS. 2009;23(9):1153–1162. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832baa34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodreau SM, Carnegie NB, Vittinghoff E, et al. What drives the US and Peruvian epidemics in men who have sex with men (MSM)? PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e50522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell JW, Petroll AE. HIV testing rates and factors associated with recent HIV testing among male couples. . Sex Trans Dis. 2012;39(12):1–3. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182479108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakravarty D, Hoff CC, Neilands TB, Darbes LA. Rates of testing for HIV in the presence of serodiscordant UAI among HIV-negative gay men in committed relationships. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(7):1944–1948. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0181-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell JW, Petroll AE. Patterns of HIV and sexually transmitted infection testing among men who have sex with men couples in the United States. Sex Trans Dis. 2012;39(11):871–876. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182649135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell JW, Horvath KJ. Factors associated with regular HIV testing among a sample of US MSM with HIV-negative main partners. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(4):417–423. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a6c8d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoff CC, Chakravarty D, Beougher SC, et al. Relationship characteristics associated with sexual risk behavior among MSM in committed relationships. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26:738–745. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell JW, Petroll AE. Factors associated with men in HIV-negative gay couples who practiced UAI within and outside of their relationship. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(4):1329–1337. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0255-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hageman KH, Tichacek A, Allen S. Couples voluntary counseling and testing. In: Mayer KH, Pizer HF, editors. HIV prevention: A comprehensive approach. London: Academic Press; 2009. pp. 240–266. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagenaar BH, Christiansen-Lindquist L, Khosropour C, et al. Willingness of US men who have sex with men (MSM) to participate in couples HIV voluntary counseling and testing (CVCT) PLoS One. 2012;7:e42953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stephenson R, Rentsch C, Sullivan PS. High levels of acceptability of couples-based HIV testing among MSM in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2012;24:529–535. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.617413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephenson R, Chard A, Finneran C, et al. Willingness to use couples voluntary counseling and testing services among men who have sex with men in seven countries. AIDS Care. 2014;26(2):191–198. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.808731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell JW. Gay male couples’ attitudes toward using couples-based voluntary HIV counseling and testing. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(1):161–171. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0211-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greacen T, Friboulet D, Blachier A, et al. Internet-using men who have sex with men would be interested in accessing authorized HIV self-tests available for purchase online. AIDS Care. 2013;25(1):49–54. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.687823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Llewellyn C, Pollard A, Smith H, et al. Are home sampling kits for sexually transmitted infections acceptable among men who have sex with men? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2009;14(1):35–43. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2008.007065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carballo-Diéguez A, Frasca T, Dolezal C, et al. Will gay and bisexually active men at high risk of infection use over-the-counter rapid HIV tests to screen sexual partners? J Sex Res. 2012;49(4):379–387. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.647117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bavinton BR, Brown G, Hurley M, et al. Which gay men would increase their frequency of HIV testing with home self-testing? AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2084–2092. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0450-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balán I, Carballo-Diéguez A, Frasca T, et al. The impact of rapid HIV home test use with sexual partners on subsequent sexual behavior among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(2):254–262. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0497-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carballo-Diéguez A, Frasca T, Balán I, et al. Use of a rapid HIV home test prevents HIV exposure in a high risk sample of men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(7):1753–1760. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0274-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frasca T, Balán I, Ibitoye M, et al. Attitude and behavior changes among gay and bisexual men after use of rapid home HIV tests to screen sexual partners. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(5):950–957. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0630-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rempel JK, Holmes JG, Zanna MP. Trust in close relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;49:95–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rusbult CE, Martz JM, Agnew CA. The investment model scale: Measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Pers Relatsh. 1998;5:357–391. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maulsby C, Millett G, Lindsey K, et al. HIV among black men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States: A review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(1):10–25. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marlin R, Young S, Ortiz J, et al. Feasibility of HIV self-test vouchers to raise community-level serostatus awareness, Los Angeles. Presented at: STD Prevention Conference; Atlanta: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan PS. Evaluation of Rapid HIV Self-testing Among MSM (eSTAMP) [online research protocol]. Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT02067039. 2014 Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02067039. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6PM7Fq6oN)