Abstract

The impact of three different sources of stress—environmental, familial (e.g., low parental investment), and interpersonal (i.e., racial discrimination)—on the life history strategies (LHS) and associated cognitions of African American adolescents were examined over an 11-year period (five waves, from age 10.5 to 21.5). Analyses indicated that each one of the sources of stress was associated with faster LHS cognitions (e.g., tolerance of deviance, willingness to engage in risky sex), which, in turn, predicted faster LHS behaviors (e.g., frequent sexual behavior). LHS then negatively predicted outcome (resilience) at age 21.5; i.e., faster LHS → less resilience. In addition, presence of the risk (“sensitivity”) alleles of two monoamine-regulating genes, the serotonin transporter gene (5HTTLPR) and the dopamine D4 receptor gene (DRD4) moderated the impact of perceived racial discrimination on LHS cognitions: Participants with more risk alleles (higher “sensitivity”) reported: faster LHS cognitions at age 18 and less resilience at age 21, if they had experienced higher amounts of discrimination ; and slower LHS and more resilience if they had experienced smaller amounts of discrimination. Implications for LHS theories are discussed.

Keywords: Life History Strategy, Discrimination, Stress, Cognition, African American

African American (Black) adolescents growing up in the U.S. face significant challenges that are more taxing, on average, than those faced by European Americans (Whites) and other minority groups. Those stressors emanate from two primary sources. First, is the environment: Black adolescents are much more likely than those of other racial/ethnic (r/e) groups to live in neighborhoods that are dangerous due to high crime rates, substance availability, and poverty and scarce resources associated with lower SES (Keppel, Pearcy, & Wagener, 2002; McArdle, Osypuk, & Acevedo-Garcia, 2007). The second is social: Black adolescents experience levels of discrimination —due to their race—that exceed those reported by adolescents of any other minority group, and, of course, much higher than those of White adolescents (Coker et al., 2009). These stressors take their toll on developmental outcomes. For example, incarceration rates of Black young adult males are six times those of Whites (West, Sabol, & Greenman, 2010), a problem that negatively affects development throughout the lifespan—well after release. Black adolescents are nine times more likely than Whites to be murdered (Gibbs, 1998), nearly three times as likely to drop out of school (Chapman, Laird, & KewalRamani, 2010), and more than three times as likely to live in a family with an income below the poverty line (FIFCFS, 2010).

Discrimination is stressful at any age, but its impact appears to be especially pronounced when it is experienced in early adolescence (Gibbons et al., 2007). Black adolescents as young as 10 report significant experience with racial discrimination (Coker et al., 2009), and these experiences are associated with elevated depression and anxiety, as well as anger (Gibbons et al., 2004; 2010); rates of conduct disorder are also much higher for Black adolescents who report having experienced more discrimination (Gibbons et al., 2007). Less intuitive, but just as serious, is the (increasing) evidence of a relation between discrimination and physical health in Black adults. The link can be seen in elevated rates of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and many types of cancer (AHA, 2010; UCSC, 2010). There is also evidence of an indirect effect among Black adolescents and adults: Discrimination correlates with unhealthy behavior, including smoking, drinking, and drug use (Bennett, Wolin, Robinson, Flower, & Edwards, 2005; Martin, Tuch, & Roman, 2003). Recent studies have also documented prospective relations between racial discrimination and substance abuse in Black adolescents (and adults) that are mediated by affect (anger), cognitions (e.g., deviance tolerance; Gibbons et al., 2004; 2010), and reduced self-control (Gibbons et al., in press). Similar relations have been found between perceived discrimination and increases in risky sexual behavior, also mediated by negative affect and “risky” cognitions (Roberts et al., in press). Once again, this relation is particularly strong when the discrimination is experienced early (by age 10).

Regarding the long-term health impact of the cumulative levels of stress experienced by many Black adolescents, the results are mixed. On one hand, rates of depression among Black adolescents are consistent with national age norms (Merikangas et al., 2010). Given the disproportionate levels of stress they experience, this suggests that Black adolescents may be particularly resilient from a mental health perspective. On the other hand, the physical health status of Black young adults and even adolescents is generally worse than that of other r/e groups—i.e., higher rates of physical injury, diabetes, and obesity (AHA, 2010; CDC, 2009). The current paper concerns the impact that different forms of stress have on the “life history strategies” (LHS) of Black adolescents; i.e., the kinds of behaviors that Black adolescents adopt in an effort to get along in environments that present significant risk for long-term survival and flourishing, as well as threats to both physical and mental health.

Evolutionary-Developmental Psychology

Life History Strategies

Life History Theory is a framework developed by evolutionary biologists, which describes strategic patterns in allocating resources among different components of fitness (i.e., growth, maintenance, and reproduction; Gadgil & Bossert, 1970). These patterns of strategies are described along a continuum of “speed” (Charnoff, 1993). Slow strategies (referred to as “K-selected” LHS in life history theory; Figueredo, 2005) reflect more of a focus on the future and long-term survival. They include behaviors such as greater parental investment in a smaller number of offspring, delayed parenthood, commitment to (long-term) relationships, and “somatic effort,” defined as (self) health care (e.g., nutrition, exercise). Slow strategies are more common in environments that can “afford” them—those with adequate resources in which life expectancies are relatively long. Slow strategies are more adaptive in these environments (we use the evolutionary psychology definition of adaptive as behaviors that promote an individual’s fitness—i.e., the contribution of offspring to future generations) because they allow individuals to accumulate resources, maximize development of offspring, and, therefore, maximize long-term reproductive success.

LHS: Fast

Fast strategies (“r-selected”), generally speaking, include the opposite of these behaviors: less commitment to long-term relationships, early sexual behavior with multiple partners, “advantage taking” (of others), and perhaps risk taking (e.g., drug use) associated with these behaviors1 (Belsky, Steinberg, & Draper, 1991; Figueredo et al., 2005). In harsh environments, fast strategies allow individuals to adopt adult roles, including procreation, before they are killed or incapacitated, thereby improving reproductive fitness in the context of poor long-term prospects. From an evolutionary perspective, there has been a gradual shift among humans toward slower LHS (“K-selection;” Figueredo et al., 2006). This reflects an increase in the availability of resources necessary for survival, which means a much higher likelihood of individual children living through reproductive age, and a corresponding decrease in need for multiple offspring. In environments that are relatively well-off, slower LHS make sense from both an evolutionary and a quality-of-life perspective. That is not true, or as true, in harsher environments, in which faster LHS generally are thought to be more adaptive.

Behavior and cognition

LHS involve not just behaviors, but also the cognitions (“style of thinking,” Bjorklund & Bering, 2002) that underlie those behaviors (Cosmides & Tooby, 1987; Kenrick, Maner, & Li, 2005). In other words, the strategies are reflected in certain value systems (e.g., future orientation) that sustain and promote the behavior (Figueredo et al., 2006). In fact, the specific behaviors associated with LHS may not necessarily benefit the organism’s fitness (e.g., aggression, mate-poaching), but the motivation underlying the behavior may be adaptive (Daly & Wilson, 2005a). This does not imply that humans are aware of the “reasons” for their LHS behaviors or have specific fitness-driven plans of action to be implemented—most evolutionary psychologists think not (Bjorklund & Kipp, 1996; Massar, Buunk, & Dechesne, 2009). But it does suggest that these attendant attitudes/cognitions can be assessed (and have been; Brumbach et al., 2009; Figueredo et al., 2005), and that there may be some temporal ordering of cognitions vis a vis behavior — i.e., adolescents show some evidence of cognitive antecedents to LHS prior to manifestation of the behavior. Important as these issues (awareness of LHS and the relation between cognitions and behaviors within specific LHS) appear to be, however, they have received relatively little empirical attention (Cosmides & Tooby, 1987).

Genetics

Another factor that is a critical component of LHS, but has also received little empirical attention, is their genetic substrate. There is some evidence of a direct association between genes and behaviors included in both fast and slow LHS repertoires (G main effects; Ellis et al., 2009). For example, functional polymorphisms in the dopamine receptor (type 4) gene, DRD4 (7 repeat allele), have been associated with risk-taking, impulsivity, and increased sensitivity to reward (Dreber et al., 2009; Harpending & Cochran, 2002), hallmarks of a fast LHS. However, most of the work done in this area has taken an epigenetic perspective, focusing on G x E interactions, typically indicating that G effects–at least in terms of phenotypic evidence --are significant only within certain environments. That work has focused more on behavior and outcome (e.g., resilience) than LHS, but the behaviors involved are linked with strategy “speed.” Evidence of this can be seen in studies of functional polymorphisms in the serotonin transporter gene, including regulatory variation in the 5HTT promoter region (5HTTLPR). The risk (short) allele for 5HTT is associated with increased sensitivity to threat and punishment; as a result, adolescents with this allele react more to aversive experiences. Brody et al. (2010), for example, found Black adolescents with the risk allele reacted to stressors such as perceived racial discrimination by engaging in more risky behaviors, maintaining low academic investment, and affiliating with deviant peers—all elements of a fast LHS.

Sensitivity to context

Similar to Brody et al., Simons et al. (in press) found that Black adolescents with both DRD4 and 5HTT risk alleles responded to “maltreatment” (i.e., abuse, discrimination) with more aggressive attitudes and behaviors. Of some interest, Simons et al. also found evidence that the “at-risk” adolescents tended to do better in environments that were positive—i.e., low in maltreatment. They suggested these adolescents are actually more responsive to their environments, what Belsky and Pleuss (2009) have labeled “ differential susceptibility,” and Ellis and Boyce (2008; Ellis, Jackson & Boyce, 2006)term biological sensitivity to context (i.e., increased sensitivity to both reward and punishment). There is increasing evidence that this perspective may present a more complete picture of G x E (i.e., genes, LHS, and reactions to environmental stress) than the more traditional “diathesis-stress” model, which focuses more on negative reactions to difficult environments. In addition, there may be some evolutionary benefit to maintaining both types of alleles in the gene pool. The future is always unpredictable, and so diversity in level of susceptibility to context increases the odds of some individuals being well suited for their environments: a sort of “bet-hedging” scenario, whereby resilient individuals will fare better if the environment is harsh, and more sensitive individuals will thrive if the environment is nurturing (Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg & Ijzendoorn, 2010). As Ellis et al. (2009) point out, however, the question of how environments and genes affect LHS is still an open one —in need of additional longitudinal studies that include genetic information along with measures of LHS behaviors(cf. Figueredo, 2005). Studies of this nature can examine the relative and combined effects of genes and environment on the adoption and manifestation of different LHS.

LHS among Black Adolescents

Defining fitness

Black adolescents are more likely than other r/e groups to adopt fast LHS —earlier sex, more partners, higher levels of “advantage-taking” (i.e., maintaining “street cred,” Anderson, 1997; more delinquency; Bjorklund & Pelligrini, 2000). This approach appears to be adaptive, given the harsh environments they often experience (Daly & Wilson, 2005b). To date, very few studies within the evolutionary-developmental psychology literature have focused on Black adolescents, however; so the question of fitness vis a vis LHS has not been addressed within this group. In this respect, the evolutionary psychology literature has done a very effective job of explaining why certain LHS emerge in certain environments, but the question of whether these strategies are adaptive in different environments is one that is easier to conceptualize than to examine empirically (as opposed to historically). In describing the utility of adaptive behavior, some have suggested a perspective that includes both long-term function (i.e, producing as many offspring as possible over the reproductive lifespan; Kaplan & Gangestaad, 2005) and short-term benefit (i.e., advantages that accrue to the organism during its lifespan that promote fitness, such as resource control and mating opportunities; Hinde, 1982). From this perspective, the behaviors that cluster together within a fast LHS may include some that are currently adaptive and some that were adaptive, but currently are not (Bjorklund & Blasi, 2005; Toby & Cosmides, 2005), in part, because, of course, environments change over time just as species do (Ehrlich & Friedman, 2003). Aggressive behavior or bullying, for example, may have “ultimate function” if it leads to the accrual of resources necessary to survive and to nurture offspring (or at least keep them alive through reproductive years) and increases access to potential mates, but not if it leads to incarceration, serious injury or illness, or premature death, all of which are likely to interfere with reproduction.

Measuring resilience

Determining which behaviors are adaptive on a short-term basis is difficult. To address this question, we first turned to the literature on resilience. Research in this area focuses on positive or successful adaptation to adversity (Luthar & Brown, 2007), and so is particularly applicable to Black adolescents. Some have argued that definitions adaptive behavior include some acknowledgement of culture and values (Luthar & Zelazo, 2003; Sameroff, Guttman, & Peck, 2003). More specifically, Masten and her colleagues have defined resilience in terms of demonstrating competence, i.e., meeting societal expectations for individuals of the same gender and developmental stage, in spite of significant risk or adversity (Masten & Coatsworth, 1998). Consistent with this definition, resilience research has represented competence or adaptation in multiple domains relevant to young adults, including physical health (Rink & Tricker, 2005; Zautra, Hall & Murry, 2010), mental health (Brennan, Le Brocque, & Hammen, 2003), avoiding harm (Fergas & Zimmerman, 2005), the ability to make and maintain social relationships (Cicchetti & Garmezy, 1993), and academic achievement (Garmezy, Masten & Taylor, 1984). With the possible exception of the last criterion, all of these factors are associated with standard definitions of fitness.

The Current Study

Overview

Because of their unique experiences-- in terms of environmental stress emanating from multiple sources-- Black adolescents are a particularly useful population for an examination of LHS theory and its hypotheses. Using structural equation modeling (SEM), we examined two central elements of LHS theory: the effects of stress on LHS, and the relation between different LHS and early adulthood outcomes (resilience). This was done using data from a panel of 889 Black adolescents over a period of 11 years-- five waves of data collection, from age 10/11 to age 21/22. Stress was defined in three ways: environmental risk (e.g., dangerous neighborhood), low parental investment (which has been associated with faster LHS; Ellis et al., 2009), and interpersonal threat (racial discrimination). Each of the three was assessed at Waves 1 and 3 (W1, W3), which allowed for an examination of change in amount of stress from each source. LHS included separate components of cognition (LHS/cog; e.g., deviance tolerance, perceptions of risk-takers) and behavior (e.g., “risky” sex, substance use). Outcome was defined in a manner congruent with the perspectives associated with researchers in both the areas of resilience and evolutionary-developmental psychology, in other words, factors that promote fitness and also reflect societal values shared by those in the Black American subculture: positive mental and physical health, presence of a supportive social network, and avoidance of incarceration. Construct indicators were drawn from both literatures. The following hypotheses were made:

All three sources of stress will predict (faster) LHS/cog, which, in turn, will predict faster LHS (behaviors).

The stress → LHS/cog relations will be moderated by genetic “sensitivity:” Those with more sensitivity genes (alleles) will respond to stressful environments by adopting faster LHS/cog, but they will respond with slower LHS/cog when in salutary environments.

LHS speed will negatively predict outcome (resilience).

Analytic plan

First, a measurement model that included all indicators of constructs (see Appendix A for a list) was fit to the data. Then a structural model was fit that included the three stressors at W1 and W3 to illustrate their effects on LHS/cog. Finally, an SEM was run in which G x E interactions were entered for each stressor to examine moderation by genetic sensitivity.

Methods

Sample

Data came from the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS), which is an ongoing study of psychosocial factors related to the mental and physical health of a panel of 889 Black families, half from Iowa and half from Georgia. Each family had an adolescent who was in 5th grade at W1 (M age: W1 = 10.5; W5 = 21.5) and self-identified as African American or Black; and a primary caregiver (referred to as parent), defined as a person living in the same household as the adolescent who was primarily responsible for his/her care. Most of the parents (92%) were female; 84% were the mother of the adolescent. At T1, the parents had a mean age of 37 (SD = 8.2), and a mean level of education of 3.3 (SD = 1.1) on a 6-point scale, which was slightly above high school level; approximately 65% of them were single mothers. The sample was generally representative of the demographic—Black families in lower and middle SES neighborhoods in Iowa and Georgia.

Recruitment and Procedure

Recruitment

Families were recruited from 259 block group areas (BGAs) in Iowa and Georgia that varied in terms of racial composition. Sites included rural communities, suburbs, and small metropolitan areas with mostly lower and middle class families. School liaisons and community coordinators compiled lists of all families in the area that included a fifth-grade Black child. Potential participant families, chosen randomly from the lists, received an introductory letter followed by a recruitment phone call. Written informed consent was obtained. Complete data were gathered from 72% of the families on the recruitment lists. Those who declined to participate usually cited the amount of time the interview took (up to 3 hours per visit) as the reason. Relevant characteristics of the neighborhoods from which the sample was chosen were: M percentage of families with children living below the poverty line: 25% (range = < 20% to > 50%); M proportion of single parent s: 19% (range = 3% to 57%); M proportion African American: 44% (range = 1% to > 90%) (further description of the FACHS sample and recruitment can be found in Gerrard, Gibbons, Stock, Vande Lune, & Cleveland, 2005; Simons et al., 2002; Wills, Gibbons, Gerrard & Brody, 2000).

Procedure

All interviewers were Black; most lived in the communities where the study took place. They received extensive training in interview techniques. Interviews were conducted in participants’ homes or nearby locations. Interviews required two interviewers and two visits, each lasting about 90 minutes. They included structured psychiatric diagnostic assessments (the Univ. of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview; Kessler, 1991, for parents; and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children [DISC-R IV], Shaffer et al., 1993). For W1–W4, questions were presented using the Computer Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI) technique. At W5, the Audio Computer Assisted Self Interview (ACASI)technique was used. Parents received $100 for their participation at W1–W3. Adolescents’ compensation ranged from $70 at W1 to $135 at W5. Average time between interviews was: W1–W2 = 22 months; W2–W3, W3–W4, and W4–W5 = 36 months. All procedures were approved by university IRBs.

Measures

Wave of measurement for each construct is noted in parentheses. A full list of items (and their reliabilities) is presented in Appendix A along with indication of which items were trimmed based on the measurement model. High scores on each measure except outcome reflect risk and/or fast LHS.

Perceived racial discrimination (W1, W3)

Participants completed a 13-item, modified version of the Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996).2 This measure, commonly used in the discrimination literature (Pascoe & Richman, 2009; Williams et al., 2003), describes various discriminatory events and asks participants how often they have experienced each type of event in the past; e.g., “How often has someone said something insulting to you just because you are African American?” (from 1 = never to 4 = several times).

Parental investment (W1, W3) was assessed with four scales. Subscales for Parent-and adolescent-reported monitoring included five items from the youths and four from the parents (e.g., “How often [does your parent/do you] know what [you do/your child does] after school?”). All items were followed by a 4-point scale from never to always. For Parent substance use, our focus was on problematic use more than occasional drug use and/or “social” drinking. The CIDI contained four questions about experiencing problems due to alcohol use within the last two years (e.g., fighting, problems at home; yes/no), as well as a list of 21 drugs; parents indicated if they had used each more than five times within the past 24 months. The 25 items were summed to create an overall score (0 to 25). Parent negative affect (NA) had the stem: “During the past week, how much have you felt..?” followed by five depression and three anxiety items (each from 1 = not at all to 3 = extremely).3

Environmental stress (W1, W3) had four indicators. Victimization was assessed by asking parents and adolescents how often they or a family member had been the victim of a violent crime. Neighborhood poverty was determined from U.S. Census data, weighted for the number of residents living in the BGA. Items included the proportion of vacant houses, and the percentage of families with income below the poverty level. For neighborhood risk, Parents were asked three questions about their perceived safety of the neighborhood.

LHS/cog (W3)

Four scales assessed adolescent’s LHS cognitions. The Tolerance of Deviance scale began with “How wrong do you think it is for someone your age to…” followed by 17 deviant behaviors (e.g., cheat on a test, have a baby; from 1 = very wrong, 4 = not at all wrong). Toughness focused on the extent to which adolescents believed that being tough is necessary to achieve respect and obtain fair treatment (e.g., “It is important to show other people that you cannot be intimidated”). Two items assessed Future Orientation (e.g., “I often think about the goals that I have for the future.” from 1 = never to 5 = always). Prototype/Willingness items came from the Prototype model of health risk (Gibbons, Gerrard & Lane, 2003); they included 20 questions about risk prototypes or images (e.g., perceptions of “the type of kid your age who uses drugs, ”the “type of girl your age who gets pregnant;” Gibbons, Gerrard, & Boney McCoy, 1995), and six questions about willingness to engage in risky behavior (e.g., use drugs, have unprotected sex).

LHS: Behavior (W4)

LHS behaviors were assessed with three scales, each on a continuum from slow to fast. Education was a single item asking how far participants had gone in school (from < high school to some college). Five items assessed risky sexual behavior, defined as behaviors that increase risk for unplanned pregnancies and STDs; e.g., number of sexual partners, frequency of unprotected sex, and frequency of sex under the influence of alcohol or drugs. Adolescents who were still virgins at T4 were given a score of zero for all items in the scale. Lastly, substance use included four items, one each for heavy alcohol consumption (> 3 drinks at one occasion)and marijuana use, and two for cigarette use.

Outcome (W5)

There were four measures intended to represent resilience, i.e., outcomes that were both adaptive and indicative of culturally-valued success.4 Physical health included four items: overall health and STI history (based on adolescent reports); and systolic/diastolic blood pressure and BMI, measured by the interviewer. Items for mental health were based on the DISC-R IV, and included 13 depression items (e.g., “In the past year, was there ever a two week period when you lost interest in things?”), which were combined with three suicide items (e.g., “In the past year, was there ever a two week period when you felt so low that you thought about committing suicide?”). Trouble with the law was a 3 -point scale: 0 = been in jail or prison, 1 = arrested but never in jail, 2 = never arrested. Finally, social relationships was assessed with six items; three concerned important, but non-romantic social bonds (e.g., “I have a lot of friends,” 1 = not at all true, 4 = always true), and three concerned the relationship with the Parent (“How happy are you with the way things are between you and your Parent?”).

Trimming

Three indicators had low loadings with their constructs (< .10) and were trimmed: Father absence for Parental investment; Somatic effort (two items each for exercise and nutrition) for LHS; and Employment (job and monthly income) for Outcome.5

Genes

DNA was collected at W5 from 576 people.6 It was prepared from saliva samples using the Oragene™ (DNA Genotek, Canada) saliva sample containers (Philibert et al., 2008). The concentration of resulting DNA solution was determined using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer, adjusted to 50 ng/ul and stored at −20°C until use. The 5HTT LPR and DRD4 exon 3 variable number of tandem repeat (VNTR) genotypes for each of the samples were determined as previously described (Beach et al., 2010). For 5HTTLPR, the locus was amplified using the following primers F-GGCGTTGCCGCTCTGAATGC and R-GAGGGACTGAGCTGGACAACCAC, and standard PCR buffers conditions supplemented by 5% DMSO and 100 μM 7-deaza GTP (Boehringer Mannheim, USA). For DRD4, DNA products were produced using the primers F-CGCGACTACGTGGTCTACTCG and R-AGGACCCTCATGGCCTTG, standard Taq polymerase and buffer, standard dNTPs in combination 100 μM 7-deaza GTP and 10% DMSO. The resulting PCR products representing each of these loci were electrophoresed across a standard 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel and then visualized by silver staining. Genotype was called by two individuals blind to genotype. For analyses, the two genotypes were summed to form a measure of cumulative sensitivity. Respondents with a sensitivity allele (either one or two) on both genes --the 7 repeat allele DRD4 and the s-allele 5HTT--received a score of 2; those with a sensitivity allele (one or two) on either gene received a score of 1; and those with no sensitivity alleles received a score of 0. The distribution of scores was: 0 = 195 (34%); 1 = 280 (49%); 2 = 101 (18%). Genotypes were available for both genes for a total of 576 people. Percentages of respondents at each level of sensitivity (high/low for each gene) can be seen in Table 1. Genotypes of both polymorphisms conformed to Hardy Weinberg equilibrium (both χ2 < .7, ps > .65).

Table 1. Percentage of respondents with no, low, and high amounts of selected items and constructs.

(time of assessment indicated in parentheses).

| Construct | No | Low | High |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Discriminationa (W1) | 10 | 83 | 7 |

| Discriminationa (W3) | 8 | 80 | 12 |

| Par recent substance useb (W3) | 96 | 4 | < 1 |

| Par NAc (W3) | 39 | 42 | 19 |

| Adolescent Victimizationd (W3) | 78 | 22 | <1 |

| Par Victimizationd (W3) | 85 | 14 | 1 |

| Families in the neighborhood with incomes below the poverty levele (W3) | 5 | 34 | 61 |

| Willingness for alc., drugs, unprotected sexc (W3) | 54 | 32 | 14 |

| Tolerance of deviancea (W3) | 21 | 71 | 8 |

| Highest level of education completedf (W4) | 58 | 27 | 15 |

| Number of sex partners g (W4) | 15 | 29 | 56 |

| Frequency of condom useh (W4) | 5 | 32 | 63 |

| Substance usei (W4) | 48 | 23 | 29 |

| High blood pressurej (W5) | 61 | 28 | 11 |

| Overweightk | 42 | 25 | 33 |

| NAc (W5) | 15 | 54 | 31 |

| Trouble with the lawl (W5) | 66 | 6 | 28 |

| Has a lot of friendsa (W5) | 11 | 27 | 62 |

| Genotype (5HTTLPR)m | 44 | - | 56 |

| Genotype (DRD4)m | 39 | - | 61 |

| Genotype (5HTT + DRD4)n | 34 | 48 | 18 |

Notes: Par= Parent (i.e., the Primary Caregiver), BP = blood pressure, W3 = Wave 3, NA = Depression + Anxiety.

1–4 scale, where none= 1, low is between 1–2.5, and high > 2.5.

1–26 scale, where none= 1, low is between 1–3.5, and high > 3.5.

1–3 scales, where none = 1, low is between 1–1.5, and high > 1.5.

none = no victimization, low = 1–2 types of incidents, high > 2 types of incidents.

By percentages, where none= 0%, low ≤ 10%, and high> 10%.

none = did not complete high school, low = high school or GED, high = at least one year of college.

none = virgins, low = between 1–2 partners, high > 2 partners.

none = never use condom, low= sometimes or most of the time, high = always or still virgins.

none = no recent use, low = use of one substance, high = use of more than one substance.

none = BP is at or below 120/80, low= systolic BP is between 121–139 and/or BP is between 81–89, high = systolic BP is above 139 and/or diastolic BP is above 89.

none = BMI < 25, low = BMI is between 25–29.9 (“overweight”), high = BMI is ≥ 30 (“obese”).

none = never been arrested or gone to jail, low = arrested but hasn’t gone to jail, high = has been in jail.

none = no risk (sensitivity) allele,, high = one or two risk (sensitivity) alleles.

none = homozygous for the non-risk alleles for both genes, low= carries the risk allele for 1 of the genes, high = carries the risk allele for both genes.

Results

Correlations and Levels of Constructs

Descriptives

Table 1 presents the percentages of participants reporting high, medium, and low (or none) levels of the focal measures. Adolescents’ reports of discrimination were high, even at T1 (90% reported some experience). Some victimization was reported by 22% of the adolescents and 15% of the Parents at T3. Parent problematic use and both depression and anxiety were consistent with national norms at W1, and then somewhat above those norms at W3 (Merikangis et al., 2010). At W3, 61% of the families lived in neighborhoods in which > 10% of the families lived below the poverty line. By W4, 83% had completed high school, 85% were sexually active, and 37% reported more than occasional risky sexual behavior. Some substance use was reported by 52% at W4. Overall, both mental and physical health status were somewhat below national norms; e.g., only 42% had normal level BMIs; 11% had high blood pressure; 31% reported elevated negative affect (scores >1.5 on the 1 – 3 scale). Rates of incarceration were very high compared to national age norms (34% had been arrested; 28% had been incarcerated; West et al., 2010).

Correlations

Table 2 presents the correlations for all of the construct indicators and the two waves of discrimination. Several correlations are worth noting. W1 (adolescent) discrimination was correlated with W1 Parent NA, as well as both risky sex and substance use at W4 (all ps < .01). W3 Parental Monitoring was correlated with most of the LHS, LHS/cog, and resilience measures (e.g., with incarceration: r = .20, p < .01). Similarly, T3 victimization was correlated with LHS and T5 NA.

Table 2. Correlation matrix of model indicators.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 & 3- Stressors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. W1Disc | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. W3 Disc | .31** | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. W1 mon | .16** | - | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. W3 mon | - | - | .27** | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. W1 Par. use | - | .10* | - | .17** | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. W3 Par. use | - | - | - | .09 | .14** | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7. W1 Par. NA | .14** | - | .14** | .09 | .13** | .10* | ||||||||||||||||||

| 8. W3 Par. NA | .11* | - | .08 | .11* | .11* | - | .39** | |||||||||||||||||

| 9. W1 Vict | .16** | - | - | - | −.12* | .07 | .12* | - | ||||||||||||||||

| 10. W3 Vict | .10* | .09 | - | - | - | - | .08 | .11* | .07 | |||||||||||||||

| 11. W1 Neigh. poverty | .10* | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | .08 | ||||||||||||||

| 12. W3 Neigh. poverty | .10* | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | .08 | .63** | |||||||||||||

| 13. W1 Neigh. risk | .10* | - | .10* | - | - | - | .14** | .12* | .08 | .10* | .31** | .21** | ||||||||||||

| 14. W3 Neigh. risk | - | - | - | .12* | - | - | .12* | .18** | - | .10* | .11* | .18** | .29** | |||||||||||

| Wave 3 - LHS Cognitions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15. PW | .08 | .19** | - | .15** | −.11* | - | - | - | - | .13** | - | −.10* | - | - | ||||||||||

| 16. Tol Of Dev | .08 | .20** | - | .21** | - | - | - | - | - | .09 | −.08 | - | - | - | .23** | |||||||||

| 17. Toughness | .10* | .11* | - | .09 | - | - | - | - | - | .08 | .10* | - | - | - | .08 | .20** | ||||||||

| 18. Future Or. | - | - | .16** | .22** | .11* | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | .18** | - | ||||||||

| Wave 4 - LHS behaviors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19. Education | - | −.10 | .10 | .09 | - | .11* | - | - | .12* | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||||||

| 20. Risky Sex | .14** | .17** | - | .17** | .13** | - | - | - | .10* | .10* | - | - | - | - | .18** | .22** | .10* | - | - | |||||

| 21. Sub. Use | .17** | .16** | .10* | .26** | - | - | - | - | - | .15** | - | - | - | - | .22** | .23** | .08 | - | .09 | .41** | ||||

| Wave 5 - Outcomes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22. Phys. health | - | - | - | −.11* | −.12* | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −.10 | - | - | - | - | −.08 | −.10 | |||

| 23. NA | −.25** | −.21** | −.15** | −.10 | - | - | −.12* | - | - | −.11** | - | - | - | - | −.09 | - | −.14* | - | - | −.13* | −.26** | .13* | ||

| 24. Jail | −.08 | −.14* | - | −.20** | - | −.08 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −.19 | - | −.13* | −.11* | −.22** | −.27** | - | .17** | |

| 25. Relations | - | - | −.13* | −.16** | - | −.08 | −.09 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | −.17** | −.09 | −.14* | −.09 | - | .26** | - |

For all correlations shown: no asterisk: p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Notes: Disc = Discrimination, Mon = Parental Monitoring (Parent and Adolescent report), Par = Parent, NA = Depression +Anxiety, Vict = Victimization, Neigh. = Neighborhood, PW = Prototype/Willingness Model Constructs, Tol of Dev = Tolerance of deviance, Future Or. = Orientation, Sub. = Substance, Phys. = Physical. Outcomes are coded such that a high score = positive outcome; all other variables are coded such that a high score = high risk..

SEM: Measurement Model

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was conducted to determine if the indicators loaded on the constructs as expected. The CFA with all nine constructs correlated provided a good fit to the data: χ2 (478) = 874.06; Fit indices were: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = .031; Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = .90; Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = .92.

SEM: Full Model

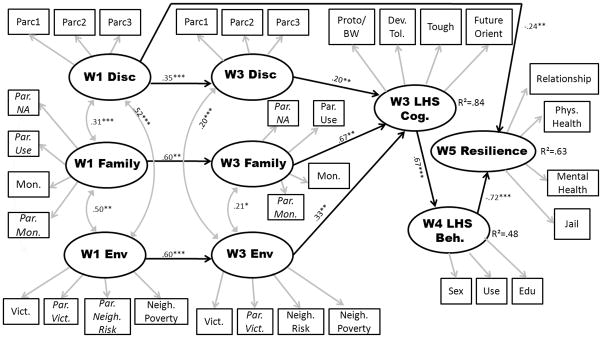

Direct relations among exogenous and endogenous constructs

Mplus Version 3.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007) with FIML was used for the SEM. Paths were specified in the model according to hypotheses and are presented in Fig. 1. Age was included as a covariate. Modification indices were used to identify nonspecified, significant paths; there was only one (see description below). The full model fit the data well: χ2 (489, N = 889) = 908.1; χ2/degrees of freedom ratio = 1.86; TLI = .90; CFI = .91; RMSEA = .030. Stability of the three stressor constructs was reasonable across the five-year lag for discrimination and environment (zs > 4.0, ps < .001). It was somewhat more modest for family (z = 2.73, p < .01), mostly due to the parental monitoring measure, which reflected an increase in variance from W1 to W3 (not surprising for the age: 10/11 to 15/16). Finally, repeated measures ANOVAs indicated that absolute levels of each of the three stressors increased over time (ps < .05).

Figure 1.

SEM showing LHS mediation of the effects of stress on resilience.

Notes: N=889 χ 2/degrees of freedom ratio = 1.86 RMSEA=0.030, TLI=0.90, CFI=0.91, PARAM=131;* p < .05, ** p < .01, * ** p <.001. The model controls for age. Parc= Parcel, W1= Wave 1, Disc= Discrimination, Family = Parental Investment; Par.= Parents (Parent-reported indicators italicized), NA=Negative Affect, Mon.= Monitoring, Env= Environment, Vict.= Victimization, Neigh.= Neighborhood, Use= Substance Use, Proto/BW= Prototype Favorability/Behavioral Willingness, Dev. Tol.= Deviance Tolerance, Tough= Toughness, LHS= Life History Strategies, Sex=Risky Sexual Behavior, Edu= Education completed. Parent-reported measures are in italics.

As anticipated, paths from each of the three W3 stressors to LH/cog were significant, explaining 84% of the variance in the construct. Thus, changes in discrimination and both parental investment and environmental stress were all associated with faster LH/cog, with the strongest relation involving discrimination (zs= 3.28 disc, 2.95family, 3.06environment; ps ≤ .001, .005, and .003, respectively). Faster LHS/cog., in turn, predicted faster LHS at age 18.5: β = .67, z = 7.24, p < .001). The path from LHS to outcome was negative and significant, as faster LHS were associated with less resilience at age 21.5; β = −.72, z = −4.91, p < .001; 63% of the variance in outcome was explained by constructs in the model.

T1 effects

A modification index identified a direct path from W1 discrimination to W5 outcome: β = −.24, z = −2.92, p < .005. Thus, experiences with discrimination in early adolescence (by age 10 or 11) were directly related to decreased resilience in early adulthood.

Indirect effects

Indirect paths through LHS/cog and LHS to outcome were also estimated from W1 and W3 for each one of the stressors. First, the total effect of early (T1) discrimination (direct + indirect paths) was significant: z = −3.25, p < .002. As can be seen in Table 3, the indirect effect for each of the W1 stressors was significant: Environment, p = .02; Discrimination and family, ps < .007. The same was true for W3 versions of the stressors; all ps ≤ .01. Thus, early stress emanating from all three sources and changes (increases) in stress from each source were associated with reduced resilience at T5, and, as expected, these effects were mediated by faster LH/cog and faster LHS.

Table 3. Direct, indirect and total effects on resilience.

| Direct effect | Indirect effect | Total effect | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| W1 Disc | −0.24** | −.03** | −.27** |

| W1 Fam | −.19** | −.19** | |

| W1 Env | −.10* | −.10* | |

| W3 Disc | −.09** | −.09** | |

| W3 Fam | −.32** | −.32** | |

| W3 Env | −.16** | −.16** | |

| W3 LHS cog | −.48*** | −.48*** | |

| W4 LHS beh | −.72*** | −.72*** | |

Notes: Coefficients are Betas. W1 = Wave 1, Disc = Discrimination, Fam = Family Stress (parental investment), Env = Environmental Stress, LHS cog = Life History Strategies: Cognitive, LHS beh = Life History Strategies: Behavioral.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

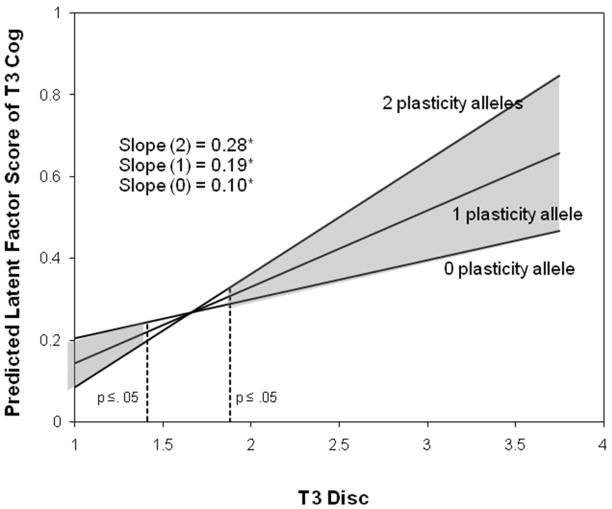

G x E: Cumulative Genetic Sensitivity and Stress

To examine the anticipated moderation of the effect of stress on LHS/cog by cumulative genetic sensitivity, new SEMs were conducted that included (manifest) interaction terms for sensitivity (G) with each one of the three sources of stress (E). There were no G main effects, as neither of the genes, nor their combination, was correlated with any of the three sources of stress (all ps > .20). The G x E interaction term was significant, but only for discrimination: β = .39, z = 2.01, p < .05 (all other ps > .70). The model including the Discrimination x Sensitivity interaction term fit the data well: χ2/degrees of freedom ratio = 1.39; TLI = .93; CFI = .94; RMSEA = .026. Post hoc analyses of significant interaction terms were then conducted using the Johnson-Neyman technique (Hayes & Matthes, 2009; Johnson & Neyman, 1936). This procedure identifies regions of significance for interactions between continuous (stress) and categorical variables (genotypes). Figure 2 presents results of this analysis: i.e., graphs of the relation between discrimination and LHS/cog for each level of sensitivity. The slopes of all three lines are significantly different from zero (ps < .001); thus discrimination → fast LHS/cog for all participants. However, the cross-over pattern of the graphs also indicates that the slopes vary as a function of level of sensitivity. More specifically, cumulative sensitivity significantly increased LHS/cog (p <.05) at higher levels of discrimination : mean values > 1.88 (on the 4-point scale). In contrast, sensitivity decreased LHS/cog when discrimination was low: values < 1.41. Thus, at higher levels of perceived discrimination, the more “sensitive” adolescents responded by adopting faster LHS cognitions. However, adolescents with the same genetic structure actually developed slower LHS cognitions if they had experienced very little discrimination.

Figure 2.

Moderation of the Discrimination to LHScog Relation by Genetic Sensitivity.

* p ≤ .001 Notes: Shaded area = Significant difference in LHScog as a f(level of genetic sensitivity and discrimination).

Discussion

The census data and their self-reports suggested that many of these Black adolescents were experiencing elevated levels of stress emanating from the environments in which they were being raised. Their self -reports also indicate that this stress was associated with faster LHS cognitions and then faster LHS behaviors. Each one of the three stressors appeared to have some influence. High environmental risk and poverty, low parental investment (“monitoring”), and perceived racial discrimination all contributed to the cumulative stress that led some of these adolescents to adopt a perspective that reflected a focus on the present more than the future, and concern with short-term outcomes and reproduction, rather than “maintenance” and “growth,” trade-offs that are indicative of a fast LHS (Gadgil & Bossert, 1970). As in previous studies with this sample, discrimination appeared to have an impact on the risky cognitions and behaviors of these adolescents that was at least as strong, if not stronger, than those associated with the other types of stress (Gibbons et al., 2004). Moreover, this impact can be seen in reports of discrimination at W1, when the adolescents were only 10 or 11 years old. The relations with W1 discrimination provided evidence of the early development of the cognitions and perspectives that would appear as fast LHS eight years later. Apparently, the roots of LHS can be seen at an early age.

LHS and Evolutionary – Developmental Psychology

Cognition vs. behavior

From a developmental perspective, there appears to be some advantage in separating cognition and behavior into two LHS components-- in spite of the strong relation between them. This is an age range (15 to 18) in which adult-like LHS are still emerging; but, apparently, many of the associated cognitions are already in place. Unlike LHS behaviors, comparison of cognitions from W3 with those at W4 showed no meaningful change (increase). In fact, there was not a lot of change in level of cognitions from W2 to W4 even though the LHS “speed” at that early age (12.5) was uniformly slow. By age 15 or 16, these adolescents had adopted a perspective that they can and did acknowledge when asked, but had not yet been manifested in behavior. These cognitions fully mediated the impact of stress on their LHS; the cognitions also mediated the G x E effects for discrimination.

Previous work with this sample has also indicated that whether these cognitions translate into behaviors that put adolescents at risk depends to some extent on risk opportunity, e.g., available substances, peers’ and/or older siblings’ behavior (Gibbons, Gerrard, Vandelune et al., 2004; Pomery et al., 2005). In other words, these fast cognitions do not necessarily evolve into fast LHS. There are a number of factors that may moderate the developmental track of LHS/cog → LHS behavior, including a changing environment—either outside the home (reduced risk in the neighborhood, success in school) or inside the home (increased investment by the parent, addition of a new caregiver or stepparent). Moreover, LHS/cognitions are malleable (Gerrard et al., 2006). In short, although the LHS/cog to LHS pathway is strong, it can be altered--which provides reason for optimism when it comes to designing effective preventive-interventions aimed at reducing risk.

Utility of a fast LHS?

It is also possible that with age and experience, some adolescents may begin to realize what our data suggest-- that there appear to be few stable benefits associated with faster LHS. Acting (and thinking) tough; seeking multiple, low-commitment sexual relationships; and hanging out with others who engage in unconventional and self-serving behaviors (i.e., “advantage-taking”) may make sense for a child who is threatened on a regular basis by his/her environment and others in it; and that is especially true if there is not an adult at home who can provide the emotional, economic, and/or physical support the child needs and (may) want. But, from either a developmental or an evolutionary perspective, it does not appear that the fast LHS that some adolescents had adopted were adaptive; i.e., they were not associated with any indicators of resilience that we assessed, including number of offspring (albeit by age 22). Of course, adopting a slower LHS under tough circumstances is easier said than done; some environments make such an approach very difficult (e.g., avoiding risky peers and risky relationships, acquiring more education); the ultimate question, however, is whether these strategies increase inclusive fitness in modern societies, as they did in societies many years ago. It may be a while before the data to answer such a basic question are available.

Early Stress and LHS

Discrimination

Being able to discriminate between ingroup and outgroup members has historically been critical to survival for humans. And, in fact, it has been suggested that prejudice and discrimination may be residual effects of what was once adaptive cognition and behavior (Kurzban, Tooby, & Cosmides, 2001; Navarrete, McDonald, Molina, & Sidanius, 2010). Although it would be difficult to argue that is still true today, it is likely that racial discrimination often presents young Black children with their first (aversive) experience informing them that they are different from others in their environments, and that this difference has important, and usually undesirable, consequences for them. Our data have suggested that very early experiences with discrimination are associated with anxiety and depression for Black children, but that affective response soon evolves into anger (Gibbons, Gerrard, & Pomery, 2010; Stock et al., in press), which remains the predominant response through adulthood. Thus, before Black children are old enough to fully appreciate the physical risks associated with their neighborhoods, they are aware that there are others who present threats to their well-being and that they may have to assume significant responsibility for dealing with those threats themselves. In this respect, there is some irony in the fact that the physical risks which emanate from their own neighborhoods and are usually perpetrated by other Black adolescents (Harrell, 2007) may have no more impact on their LHS than the interpersonal risks associated with prejudice-- risks that are seldom life-threatening, but may have more of an impact on expectations for the future (Mattis, Fontenot, & Hatcher-Kay, 2003) and therefore on LHS.

Parental investment

Comparing the zero-order correlations at W1 vs. W3 between stress and both LHS and outcome suggests that the same is true for parental investment—low investment at W1 and W3, as well as a decline in investment from W1 to W3, were all associated with faster LHS and less resilience at W5. Even before initial exposure to racial discrimination, the lack of close supervision/investment from the mother may be the first indication the child gets of the risk and support provided by his/her environment, just as early discrimination may be his/her first indication of threat. These early realizations appear to be important in initiating a LHS perspective that unfolds over the next few years.

Genetic Sensitivity

Adolescents with risk alleles for either DRD4 or 5HTT, or both, were more responsive to the discrimination they had experienced. For these adolescents, who are especially sensitive to environmental factors that involve or signal risk and threat, aversive experiences like those associated with racial discrimination are likely to elicit a stronger reaction (e.g., anger; Gibbons et al., 2010; perceived threat, discouragement). This reaction appears to include an acceleration of their LHS thinking--focusing more on the present and the need to reproduce—which then leads to faster LHS behaviors consistent with that perspective. On the other hand, when adolescents with this same “sensitivity” genotype were faced with a more benign interpersonal environment, characterized by relatively few experiences with the pain of discrimination, they developed LHS that were actually somewhat slower than adolescents without this heightened sensitivity. In light of the extensive literature linking discrimination with unhealthy behavior and worse mental health, this G x E interaction appears to be worthy of future research.

Interestingly, there was no evidence that sensitivity moderated (LHS) reactions to other kinds of stress, including physical risk and parental detachment. That is consistent with data from the parents of these FACHS adolescents indicating that perceived discrimination had more impact on health behavior than any of the (extensive array of) stressors that were assessed, including those associated with economic, familial (relationship problems), and other negative life events (e.g., death of a loved one, loss of a job; Gibbons et al., 2004). We suspect the interpersonal nature and long-term negative implications of this particularly pernicious and unfair type of stress may be the reason, but, again, this question shall remain for future research.

Resilience

Our definition of resilience was based on the evolutionary psychology and resilience literatures (as well as reports from FACHS parents and adolescents; see Footnote 2). All four outcomes are related to inclusive fitness—e.g., maintaining good relations with potential caregivers and sex partners (mother, friends), staying physically and mentally healthy, staying out of jail—and also related to general success for Black (and other) young adults. Surprisingly, when we looked at the correlations between number of offspring at T5 (age 21/22) and each one of these measures as well as the aggregate, none of them was significant; of course, this could change as they get older. However, the outcome measure was clearly negatively related to LHS speed (both cognitions and behavior). Looking at the overall model, one can get a clear sense of why many of these Black adolescents adopted the LHS perspectives and strategies that they did—in response to environments that for many, were discouraging, toxic, and perhaps life-threatening. But, once again, it does not appear that these fast strategies were adaptive, at least in a traditional sense. Put another way, there was no evidence that Black adolescents in equally stressful environments who did not adopt these strategies fared any worse. Finally, it is worth mentioning that, unlike most studies of Black adolescents, participants in this study—i.e., members of the FACHS panel-- were not living in inner-city areas where crime rates and rates of morbidity and mortality are even higher. The pattern of results might be even stronger for those Black populations.

Limitations

Measurement

Several limitations of the study need to be acknowledged. First, some factor loadings were low, and yet the indicators were retained for conceptual/theoretical reasons. In some instances, that reflects the diverse nature of the construct (e.g., STIs and high blood pressure are both indicators of health problems, but they aren’t correlated); but it most likely also reflects some measurement error, which is an issue--especially at early participant ages. Also, some of the constructs included only one or two items (e.g., education and future orientation). These issues are likely to work against the hypotheses; regardless, replication with more extensive measures is called for. Third, although the age of the sample was ideal for assessing LHS/cog and, to a lesser extent, LHS; it was a bit young for assessing actual fitness (very few of them had children by the age of 18; only 30% had children by age 22).

Sample

Fourth, the sample comprised only Black adolescents living in two states (at W1), which raises a question of generalizability. LHS theory is not unique to any one population, and so we would expect the pattern of relations to be similar among other r/e groups, or among Black adolescents living in other environments (either more or less stressful); i.e., stress → faster LHS cognitions → faster LHS → less resilience. That does not mean that the models would be identical across groups, however, because both the sources and amounts of stress are likely to differ considerably. As suggested earlier, Black adolescents experience more stress, on average, than do White adolescents, in part, because they face the burden of discrimination. In short, cross-validation with other r/e groups is needed.

Genetic admixture

Finally, there are reasons to expect that the G x E interaction pattern might differ across r/e groups. First, different r/e groups have different genetic architectures. African Americans, for example, have significant European genetic admixture (as much as 25%; Collins-Scram et al., 2002; Shriver et al., 2003). Moreover, the allele frequencies of both 5HTTLPR and DRD4 vary by r/e and geographic region (Esau, Kaur, Adonis, & Arieff, 2008). This raises the possibility that our findings were driven partly by additional genes that covary with both of our candidate genes and with admixture. Also, discrimination was the only one of the three sources of stress that produced a G x E interaction. There may be other kinds of stress that interact with either gene (or other genes) to produce evidence of sensitivity for other r/e groups. This also appears to be an empirical question well worth pursuing in future research.

Future Directions

Clearly, there is a need for additional research with Black adolescents and young adults in the area of evolutionary-developmental psychology. Examining the impact of LHS on resilience later in adulthood will be one goal of the FACHS project in the future. We also have DNA from the parents, which will allow us to further examine genetic and epigenetic influences on these young adults as they continue to develop and have children. Another epigenetic process of interest involves methylation. Stressors like those assessed in this study (including, perhaps, the stress associated with discrimination) can affect methylation (alterations of gene expression without actual changes in the underlying DNA sequence; Beach, Brody, Todorov, Gunter, & Philibert, 2010). Such changes can affect reproduction, and may have implications for the study of evolution. Also, there are important gender differences in LHS, and that was the case in the current sample. The relation between LHS and outcome, for example, was significantly stronger for males. A discussion of these differences is beyond the scope of the current paper, but they are definitely worthy of empirical attention in the future. Finally, future studies should incorporate methods, such as estimation with Ancestry Informative Markers (AIM; e.g., Halder et al., 2009; Reiner et al., 2005), to adjust for correlated variation in European admixture among African Americans. This will provide a more precise indication of the role of the two candidate genes in the G x E interactions we detected.

Conclusions

Black adolescents, on average, are exposed to significant environmental and interpersonal stressors, including (especially) perceived racial discrimination, that lead some of them to adopt fast LHS cognitions, by mid-adolescence, and then fast LHS behaviors in late adolescence. These behaviors, in turn, are negatively related to successful outcomes (resilience) in early adulthood. This important relation between discrimination and LHS/cognitions is moderated by genetic structure, such that adolescents with a predisposition toward environmental “sensitivity” (Ellis & Boyce, 2008) are more likely to respond with fast cognitions when they experience high amounts of discrimination, but less likely to develop these cognitions when they experience low amounts of discrimination. Finally, it is concluded that useful information, from a developmental and an evolutionary perspective, can be provided by examination of LHS cognitions and LHS behaviors separately over time, during adolescence.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIDA grantsDA018871 and DA021898; and NIMH grant # MH062668.

Appendix

Table A1.

All items used in the structural equation model, separated by construct (wave assessed), and indicators within each construct. Alphas for indicators included.

| Indicator | Item |

|---|---|

| Discrimination (W1, W3) αs = .86 and .90 | |

| Parcel 1a | How often has/have….. You been treated unfairly just because of your race or ethnic background? Your close friends been treated unfairly just because of their race or ethnic background? Someone ignored you or excluded you from some activity just because of your race or ethnic background? Someone discouraged you from trying to achieve an important goal just because of your race or ethnic background? |

|

|

|

| Parcel 2a | Someone said something insulting to you just because of your race or ethnic background? A store-owner, sales clerk, or person working at a place of business treated you in a disrespectful way just because of your race or ethnic background? Someone suspected you of doing something wrong just because of your race or ethnic background? The police hassled you just because of your race or ethnic background? |

|

|

|

| Parcel 3a | Members of your family been treated unfairly just because of their race or ethnic background? Someone yelled a racial slur or racial insult at you just because of your race or ethnic background? Someone threatened to harm you physically just because of your race or ethnic background? You encountered people who are surprised that you, given your race or ethnic background, did something really well? You encountered people who didn’t expect you to do well just because of your race or ethnic background? |

|

|

|

| Parental Investment (W1, W3) | |

| Par-reported Monitoringb αs = .62, .77 | How often do you know… What [child’s name] does after school? Where [child’s name] is and what he/she is doing? How well [child’s name] is doing in school? If [child’s name] does something wrong? |

|

|

|

| Adolescent-reported Monitoringa αs = .59, .75 | How often does your [PAR name] know… What you do after school? Where you are and what you are doing? How well you are doing in school? If you do something wrong? How often can you do whatever you want after school without you [PAR relationship] knowing what you are doing? |

|

|

|

| Par Substance Useb αs = .80, .40 | Was there ever a time/times in your life when….. Your drinking or being hung over frequently interfered with your work at school, on a job, or at home? You frequently got into physical fights while drinking? You were arrested for disturbing the peace or for driving while under the influence of alcohol? You have often been under the influence of alcohol in situations where you could get hurt, for example, when riding a bicycle, driving, operating a machine, or anything else? Have you in your life taken___more than five times? betel nuts, inhalents, opium, pot, gasoline, cocaine, coca leaves, toluene, crack, hashish, peyote, heroin, khat, mescaline, DMT, ganja, LSD, PCP, bhang, psilocybin, glue |

|

|

|

| Par Negative Affectb αs = .85, .87 | During the past week, how much have you felt ? depressed, discouraged, hopeless, like a failure, worthless, tense or “high strung”, uneasy, keyed up or “on edge” |

|

|

|

| Environmental Stress (W1, W3) | |

| Adolescent Victimizationa αs = .39, .48 | While you have lived in this neighborhood, has anyone ever used violence (such as in a mugging, fight, or sexual assault) against you or any member of your household anywhere in your neighborhood? If so, how many times? In the past 12 months, was a family member a victim of a violent crime? In the past 12 months, were you a victim of a violent crime? |

|

|

|

| Par Victimizationb αs = .52,.57 | In the past 12 months… were you robbed or burglarized? did you have something valuable lost or stolen? were you sexually molested, assaulted, or raped? were you seriously physically attacked or assaulted? did you witness someone being badly injured or killed? were you threatened with a weapon, held captive, or kidnapped? |

|

|

|

| Neighborhood Povertyc αs = .79, .82 | Ratio of vacant housing: number of housing units % people aged 25 and older without a high school degree % civilian males unemployed % civilian females unemployed % households receiving public assistance income % families with income below the poverty level |

|

|

|

| Neighborhood Riskb αs = .56, .57 | The park or playground closest to where you live is safe during the day. The park or playground closest to where you live is safe at night. How safe do you feel your neighborhood is? |

|

|

|

| Life History Strategies: Cognitive (W3) | |

| Prototype-Willingness Constructsa α = .89 | How __ are the type of kids your age who frequently drink alcohol? Popular, smart, cool, good-looking How __ are the type of kids your age who use drugs Popular, smart, cool, good-looking How __ are the type of girls/boys your age who choose NOT to have sex at all (until they’re older) [reversed] Popular, smart, cool, good-looking How __ is the type of girl your age who gets pregnant… Popular, smart, cool, good-looking How __ is the type of boy your age who gets a girl pregnant Popular, smart, cool, good-looking Suppose you were with a group of friends and there was some alcohol there that you could have if you wanted. How willing would you be to …drink one drink …more than one drink …get drunk Suppose you were with a group of friends and there were some drugs there that you could have if you wanted. How willing would you be to …take some and use it … use enough to get high Suppose you were alone with your boyfriend/girlfriend boy/girl [phrased so that asked about persons of the opposite gender]. He/she wants to have sex, but neither of you has a condom. In this situation, how willing would you be to go ahead and have sex? |

|

|

|

| Tolerance of Deviancea α = .94 | How wrong do you think it is for someone your age to….. Drink alcohol? Purposely damage or destroy property that does not belong to them? Hit someone with the idea of hurting them? Steal something worth less than $25? Use marijuana or other illegal drugs? Steal something worth more than $25? Take a car or motorcycle for a ride without the owner’s permission? Skip school without an excuse? Shoplift something from a store? Smoke or chew tobacco? Cheat on a test? Lie to teachers or parents? Sell marijuana or other illegal drugs? Have sexual intercourse? Have oral sex? Have sex without using a condom? Have a baby? |

|

|

|

| Toughnessa α = .76 | Sometimes you have to use physical force or violence to defend your rights. People will take advantage of you if you don’t let them know how tough you are. People who get into fights are bullies. Sometimes you need to threaten people in order to get them to treat you fairly. People do not respect a person who is afraid to fight physically for his or her rights. Behaving aggressively is often an effective way of dealing with someone who is taking advantage of you. If you don’t let people know you will defend yourself, they will think you are weak and take advantage of you. It is important to show other people that you cannot be intimidated. People tend to respect a person who is tough and aggressive. |

|

|

|

| Future Orientationa αs = .60 | I know what I need to do to reach my most important goals I often think about the goals that I have for the future |

|

|

|

| Life History Strategies: Behavior (W4) | |

| Educationa | What is the highest level of education you have completed? |

|

|

|

| Risky Sexual Behaviora αs = .78 | With how many people have you had sex? In the last 3 months, how many times have you had sex with a boy/girl [phrased so that asked about persons of the opposite gender] In the last 3 months, how many times have you had sex without using a condom (rubber)? When you have sex, how often do you use a condom? When you have sex, how often do you have some alcohol or drugs beforehand? |

|

|

|

| Substance Usea αs = .50 | During the past 12 months, how often have you had a lot to drink, that is 3 or more drinks at one time? How many cigarettes have you smoked in the last 3 months? How much do you smoke cigarettes now? During the past 12 months, how often have you used Marijuana in order to get high? |

|

|

|

| Outcome (Resilience) (W5) | |

| Physical Healthe αs = .38 | How would you describe your health right now? Have you ever been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted disease (STD) like herpes, gonorrhea, or chlamydia? Systolic blood pressure Diastolic blood pressure BMI |

|

|

|

| Mental Healtha αs = .86 | In the past year, was there ever a two week period when you….. Felt sad, empty, or depressed most of the day? Lost interest in things? Woke up at least two hours before you wanted to? Slept too much almost every day? Couldn’t sit still and paced up and down or couldn’t keep your hands still when sitting? Felt worthless nearly every day? Felt guilty? Felt like you were not as good as other people? Had so little self-confidence that you wouldn’t try to have your say about anything? Were a lot less interested in sex than usual? Lost the ability to enjoy having good things happen to you, like winning something or being praised or complimented? Took medication for depression? Were so depressed or sad that it interfered with your ability to do your job, take care of your house or family, or take care of yourself? Thought a lot about death? Felt so low that you thought about committing suicide? Attempted suicide? |

|

|

|

| Trouble with the lawa | Have you been arrested in the last 12 months? Have you been in jail/prison in the last 12 months |

|

|

|

| Social relationshipsa αs = .62 | I find it hard to make friends. I have a lot of friends. I am not liked by very many others. In the past 12 months, how often have you and your Par been in contact either in person or by phone, email, or letter writing? How satisfied are you with your relationship with your Par? How happy are you with the way things are between you and your Par? |

|

|

|

| Constructs Trimmed from the Model | |

| Father Absent (W1)b | Is the secondary caregiver [child’s name]’s father or stepfather? |

|

|

|

| Somatic Effort (W4)a | During the past 7 days… how many times did you eat a whole piece of fruit (for example, an apple, orange or banana) or drink a glass of 100% fruit juice (do not count punch, Kool-Aid, or sports drinks)? During the past 7 days, how many times did you eat vegetables like green salad, carrots or potatoes (do not count French fries, fried potatoes, or potato chips)? On how many of the past 7 days did you exercise or participate in physical activity for at least 30 minutes that made you breathe hard (such as basketball, soccer, running, or riding a bicycle hard)? On how many of the past 7 days did you exercise or participate in physical activity for at least 30 minutes that did not make you breathe hard, but was still exercise (such as fast walking, slow bicycling, skating, pushing a lawn mower or doing active household chores)? |

|

|

|

| Employment (W5)a | What is your present work situation? Approximately how much do you earn per week at your job(s)? |

Notes: Par = Primary Caregiver.

Adolescent-reported;

Par-reported;

block group data from the 2000 Census;

health and STD history were adolescent-reported; blood pressure, height, and weight were measured by the interviewer.

All but two indicators were created by aggregating all items: Par substance use was created by summing the dichotomous items, and mental health was created by summing the average of the 13 items unrelated to suicide with the average of the 3 related to suicide.

Footnotes

There is some disagreement in the evolutionary-developmental psychology literature as to whether risk-taking per se (e.g., substance use) is necessarily part of LHS (Brumbach et al., 2009). We chose to include it in the LHS construct for conceptual and empirical reasons: a) substance use is often associated with “risky” sexual behavior (which clearly is part of a fast LHS); and b) consistent with that, substance use cognitions did load well with other LHS/cog measures, and substance use loaded well with other LHS behaviors.

Modifications from the original scale were minor and involved simplifying the language (for administration to adolescents) and replacing some of the items assessing workplace discrimination with perceived discrimination in the community.

Substance abuse problems and negative affect do not necessarily reflect low investment motivation by the parents, but they are likely to interfere with the parents’ ability to actually invest in their children, spend time with them, and parent them.

Culturally-valuedsuccess for African Americans was determined by: a) a review of the relevant literature (e.g., Farmer et al., 2006); b) a pilot study with participants from FACHS (N = 39) who were asked to describe what they thought constituted success for young Black adults; and c) a series of five focus groups conducted with Black adolescents (N = 19) and adults (N = 15) who were asked the same questions about success.

There were also several constructs with low loadings (i.e., < .20) that were retained for theoretical/conceptual reasons — i.e., they were thought to be critical to the relevant construct even though they did not load highly with the other factors; those were: education completed, physical health (at T5), Parent victimization and problematic use, and neighborhood poverty levels. Eliminating these indicators did not improve the fit of the model significantly.

The primary reason for the lower N for DNA was sample attrition, as > 90% of those who participated in W5 provided samples. A comparison on the key constructs of those in W5 who did vs. those who did not provide samples indicated that nonproviders reported: more substance use at T4 (t = 2.60, p = .01), less education (marginal: p < .09), and much more jail/prison experience (t = 5.20, p < .001); there were no other significant differences on any measures (e.g., T3 Discrimination, T4 risky sex, negative affect, and relationship satisfaction, and T5 health status).

References

- American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.americanheart.org/downloadable/heart.

- Anderson E. Violence and the inner city street code. In: McCord J, editor. Violence and Childhood in the Inner City. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Beach SR, Brody GH, Lei MK, Philibert RA. Differential susceptibility to parenting among African American youths: Testing the DRD4 hypothesis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:513–521. doi: 10.1037/a0020835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Brody GH, Todorov AA, Gunter TD, Philibert RA. Methylation at SLC6A4 is linked to family history of child abuse: An examination of the Iowa Adoptee Sample. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B. 2010;153B:710–713. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pleuss Beyond diathesis-stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(6):885–908. doi: 10.1037/a0017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Steinberg L, Draper P. Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: An evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Development. 1991;62:647–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GG, Wolin KY, Robinson EL, Fowler S, Edwards CL. Perceived racial/ethnic harassment and tobacco use among African American young adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:238–240. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.037812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund DF, Bering JM. The evolved child: Applying evolutionary developmental psychology to modern schooling. Learning and Individual Differences. 2002;12:347–373. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund DF, Blasi CH. Evolutionary developmental psychology. In: Buss DM, editor. The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2005. pp. 828–850. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund DF, Kipp K. Parental investment theory and gender differences in the evolution of inhibition mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;120:163–188. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund DF, Pelligrini AD. Child development and evolutionary psychology. Child Development. 2000;71:1687–1708. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan P, Le Brocque R, Hammen C. Maternal depression, parent-child relationships and resilient outcomes in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:1469–1477. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200312000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Beach SR, Chen Y, Philibert RA, Kogan SM, Simons RL. Perceived discrimination, 5-HTTLPR status, and conduct problems: A differential susceptibility analysis. Developmental Psychology in press. [Google Scholar]

- Brumbach BH, Figuerdo AJ, Ellis BJ. Effects of harsh and unpredictable environments in adolescence on development of life history strategies: A longitudinal test of an evolutionary model. Human Nature. 2009;20:25–51. doi: 10.1007/s12110-009-9059-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Health Disparities and Racial/Ethnic Minority Youth. 2009 Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/Features/HealthDisparities.

- Chapman C, Laird J, KewalRamani A. Trends in high school dropout and completion rates in the United States: 1972–2008 (NCES 2011–012) National Center for Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Garmezy N. Prospects and promises in the study of resilience. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:497–502. [Google Scholar]

- Coker TR, Elliott MN, Kanouse DE, Grunbaum JA, Schwebel DC, Gilliland, Schuster MA. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination among fifth-grade students and its association with mental health. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:878–884. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]