Abstract

This article applies a culture-centered approach to analyze the dietary health meanings for Asian Indians living in the United States. The data were collected as part of a health promotion program evaluation designed to help Asian Indians reduce their risk of chronic disease. Community members who used two aspects of the program participated in two focus groups to learn about their health care experiences and to engage them in dialogue about how culture impacts their overall health. Using constructionist grounded theory, we demonstrate that one aspect of culture, the discourses around routine dietary choice, is an important, but under-recognized, aspect of culture that influences community members’ experiences with health care. We theorize community members’ dietary health meanings operate discursively through a dialectic tension between homogeneity and heterogeneity, situated amid culture, structure, and agency. Participants enacted discursive homogeneity when they affirmed dietary health meanings around diet as an important means through which members of the community maintain a sense of continuity of their identity while differentiating them from others. Participants enacted discursive heterogeneity when they voiced dietary health meanings that differentiated community members from one another due to unique life-course trajectories and other membership affiliations. Through this dialectic, community members manage unique Asian Indian identities and create meanings of health and illness in and through their discourses around routine dietary choice. Through making these discursive health meanings audible, we foreground how community members’ agency is discursively enacted and to make understandable how discourses of dietary practice influence the therapeutic alliance between primary care providers and members of a minority community.

As ethnic and cultural diversity increase in the United States, health care providers are increasingly called to understand the ways in which cultural context influences how health meanings are constructed and employed in practice (Airhihenbuwa, 1995; Dutta, 2008; Lupton, 1994). According to the 2000 U.S. Census, more than 2.5 million Asian Indians1 live in the United States (Smedley et al., 2003). In comparison with other Asian groups, Asian Indians are known to have higher rates of diabetes (Wang et al., 2011) and cardiovascular disease (Holland et al., 2011; Kandula et al., 2008) and to be at higher risk for obesity (Lauderdale & Rathouz, 2000). Poor diet is a major risk factor for these diseases (Dixit et al., 2011), and dietary changes are known to improve risk, both in India (Ramachandran et al., 2006) and the United States (Kandula, Lauderdale, & Baker, 2007). Immigration and acculturation are associated with health behaviors, beliefs and even disease outcomes in Asian Americans (Kandula et al., 2008; Kandula, Lauderdale, & Rathouz, 2000; Poulsen, Karuppaswamy, & Natrajan, 2005).

Although the density and growth rate of Asian Indians in the United States is high compared to other minorities, little guidance is available for clinical care tailored to the Asian Indian community's needs and preferences. This article is the result of an evaluation of a health care program at the Palo Alto Medical Foundation (PAMF), a large, ambulatory health care system in northern California that targets the Asian Indian community. Asian Indians comprise 12% of the total PAMF membership. In 2006, PAMF started a health promotion program called “Prevention and Awareness for Asian Indians” (PRANA) to address the epidemic-level incidence of diabetes and heart disease within the Asian Indian community. For patients, the PRANA program offers a website with culturally tailored resources and information, prevention screening, and wellness education, such as physical activity and nutrition consultations to help support patients with one or more chronic illness. For providers, PRANA educates allied health professionals about the unique biomedical and psychosocial needs of Asian Indian patients.

In 2008, the PAMF Quality and Planning Division invited community members to focus groups in order to learn about the local context of the community's health care experiences in general as well as to evaluate their experience with the PRANA program in particular. The ultimate goal of the evaluation was to provide guidance and feedback about which aspects of the program were effective to expand those areas and to prune those areas that proved ineffective. Because community-level involvement has been integral to developing and implementing the program, community members who participated in one or more PRANA program components were invited to participate in two focus groups. Through examining participants’ experience with the program, this analysis seeks to answer the following research question:

RQ: What aspects of day-to-day dietary choice impact Asian Indians’ experience of health care in the United States?

Using constructionist grounded theory, we used a culture-centered approach (Dutta, 2008) to examine the Asian Indian experience of communication about dietary health meanings in a clinical setting. We argue that the health care experiences of community members who emigrated from India or whose cultural heritage derives from India affect agency and negatively impact participation within the existing structure of the U.S. primary care.

DIET AS IDENTITY

Anthropologists have long recognized the significance of food in defining cultural differences, particularly the selection, preparation, and serving of food as a socially organized behavior (Levi-Strauss, 1966a/1969; 1966b). Scholarship on the anthropology of food recognizes that dietary choice is a marker of ethnic identity through cuisine characterized by “particular flavor and [food] type, recipes that combine food elements in particular ways, meal formats that aggregate the dishes in predictable manners and meal cycles that alternate meal formats into ordinary and festival meals” (Messer, 1984, p. 226). Socially, food helps to (re-)create interpersonal and nonpersonal relationships and social meanings among group members. For example, Bisogni et al. (2002) found that decisions about food choices were imbued with multiple meanings, including eating behaviors, personal traits, and social categories. Their analysis shows multiple relationships between food and identity resulting in a complex picture in which the individuals can discursively mobilize different identities, including role identities, such as caretaker or parent, and group membership of one or more social or cultural groups.

Daily food decisions also play a role in (re-)creating and maintaining social identities. Mintz and Du Bois (2002) suggest that food helps to solidify group membership and to set groups apart from one another. Appadurai (1981) codifies this dialectic discursively through a set of contradictory social relations between and among Hindus living in India. According to this analysis, diet provides a means for homogeneity in which food increases intimacy, equality, or solidarity among group members. Simultaneously, diet provides a means for heterogeneity in which food emphasizes distance, inequality, or fragmentation between group members. These analyses point to the significance of food and dietary choice in creating identity as it is socialized in and through cultural, religious, and social norms (Lambert, 1992).

Sobal and Bisogni (2009) argue that multiple factors influence an individual's dietary choice, including lived experiences, life course trajectories, taste, healthfulness, cost, convenience, and social relationships. When individuals immigrate to a new social context, the food items selected to eat take on particular meaning in terms of identity maintenance and renovation (Kalra et al., 2004; Lawton et al., 2008). Chapman, Ristovski-Slijepcevica, and Beagan (2010) show that community members of Punjabi Sikhs origin living in Canada experience a tension in their food choices between the knowledge about food as handed down in the Sikh religious community of practice and about food as part of a medico-scientific discourse related to epidemiological processes of chronic disease risk. Older participants who were born in India but later immigrated to Canada preferred eating Indian foods daily, whereas younger participants who were born in Canada preferred limiting Indian food consumption to a few times per week in favor of a more diverse diet locally available. This suggests that dietary choice is a dynamic form of cultural practice that is influenced by both individual and community values as they historically unfold according to environmental, social, and cultural contexts.

THE CULTURE-CENTERED APPROACH

The culture-centered approach to health communication is a methodological and theoretical framework that provides a lens for analyzing and interpreting the lived experiences of minority communities. This approach treats communication as the articulation of shared meaning of health experiences as integral to cultural members’ socially constructed identities, relationships, and social norms (Dutta, 2008). Through dialogic engagements with locally constituted stories, culture-centered interrogations seek to understand the ways in which community members at the margins of mainstream health care negotiate meanings of health and constitute their actions located within dominant structures of meaning.

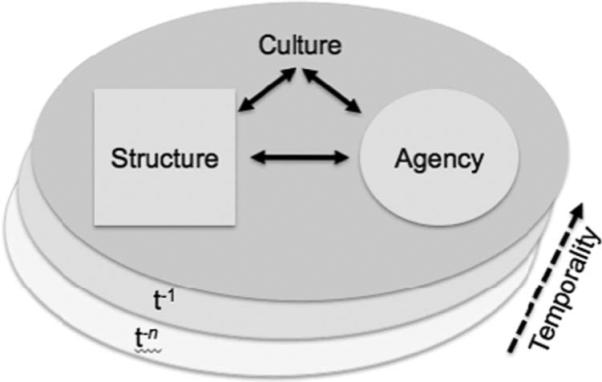

The culture-centered approach builds on structuration and subaltern studies theories. Structuration theory (Giddens, 1984) recognizes the dialectical tensions between structure and agency. Structure refers “to the constellation of institutional and organizational networks that constrain the availability of resources” (Dutta & Basu, 2007), while agency refers to “a temporally embedded process of social engagement” (Emirbayer & Miche, 1998, p. 963), which includes the competency to make practical and normative choices in response to the emerging demands of real-time situations (p. 971). For example, religious Hindus adhere to a strict vegetarian diet that requires constant vigilance in daily dietary choices to maintain ethical and religious values in everyday life. The food choices an individual makes can “signal caste or sect affiliation, life-cycle stages, gender distinctions, and aspirations towards a higher status” (Appadurai, 1981, p. 495), thereby showing how normative choice can demonstrate agency in locally situated contexts. The culture-centered approach proposes that structure and agency are embedded within culture, which is an ever-changing system of values that influences attitudes, perception, and behaviors that enable and constrain social action (see Figure 1). While the culture-centered approach places agency at the theoretical core, Dutta and Basu (2007) recognize that culture “emerges as the strongest determinant of the context of life that shapes knowledge creation, sharing of meanings, and behavior changes” (p. 561). Situating agency within a cultural context adds personal and social history to the structure–agency framework, where different “contexts support particular agentic orientations, which in turn constitute different structuring relationships of actors towards their environments” (Emirbayer & Miche, 1998, p. 1004). Agency, then, creates the possibility for actors to transform their relationship to structure and offers the possibility for social change through time (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The culture-centered approach proposes a conceptual framework that integrates the dynamic interaction between structure and agency as embedded in a cultural context that evolves through time.

Subaltern studies theory (Guha, 1988; Spivak, 1988) proposes that historical, economic, and ideological forces silence marginalized communities by imposing a “one size fits all” set of values offered by the dominant paradigm, thereby excluding endogenous community values. Subaltern subjects are rendered marginalized through systematic institutional mechanisms that are invisibly enacted through the ideologies of the health care system. As a result, the subaltern sectors are rendered absent from the dominant spaces of knowledge. Whenever a discourse is not afforded equal presence or equal authority, this results in exclusion and marginalization (Cheek, 2004). As an antidote to these processes, the culture-centered approach proposes the notion of voice. de Souza (2009) writes that in the health care setting, “Having a voice refers to a condition in which marginalized communities speak for themselves, make their own decisions and contest claims that do not resonate with a sense of who they are” (p. 696). Marginalization is the effect of one discourse being voiced while another discourse is silenced. Voice affirms cultural members’ agency by literally articulating epistemological questions among identity, experience, and point of view (Keane, 2001) to connecting micro and macro scales of power, thereby enabling enables cultural members to critique the status quo as a means to break marginalizing practices through reflexivity.

METHODS

Sampling and Recruitment

Prospective Asian Indian participants were identified using the PAMF electronic health record that included classification of self-reported (Palaniappan et al., 2009b) or name-inferred (Wong et al., 2010) race/ethnicity. Participants were eligible if they had experienced at least two aspects of the PRANA program mentioned earlier (i.e., web-site, nutritional consultations, group medical appointments, etc.), and if they felt comfortable speaking English. A private contractor specializing in market research was hired to recruit and facilitate the focus groups.

Fifteen participants participated in two focus groups during fall 2008. Demographically, participants were representative of the catchment area: They were mostly foreign born (78%), speaking a language other than English at home (90%), married (76%), with most having a bachelor's degree or higher (79%) and employed (66%) in mainly management and professional occupations (73%), with household income of more than $50,000 (92%). All participants had health insurance. Because some South Asian cultures maintain strict gender role divisions, separate groups were held for men (n = 7) and women (n = 8) to encourage candid participation. Participants were paid $85 and were provided dinner. During the focus groups, participants were asked about their health care experiences in general as well as their reactions to specific modalities of the program (see Table 1 for example questions). Focus groups were audiovisually recorded for later analysis. Participants signed a voluntary consent form, which included the provision that names used in reporting be pseudonyms. The PAMF Institutional Review Board approved this research.

TABLE 1.

Example Questions From the Focus-Group Interview Guide

| Research Domain | Illustrative Questions |

|---|---|

| Perceptions of health care | How does being Asian Indian affect your health care? |

| What aspects of health care you find particularly lacking? | |

| Experiences with specific health problems | What are some specific health issues related to being Asian Indian that you have experienced? |

| How have you dealt with them? | |

| Improving medical care | What might help improve medical care delivered to Asian Indians in the US? |

| How has your health care provider addressed your specific needs? | |

| Reaction to the PRANA program | How would you describe PRANA in your own words? |

| What benefit has your participation in the PRANA program provided you? | |

| What could the program do better? |

Data Management and Analysis

Two forms of data were collected from the focus groups: ethnographic field notes and video recordings. To document the overall communicative ecology of the events (Roberts & Sarangi, 2005), two authors (CJK and LP) observed the live focus groups behind a one-way mirror and wrote condensed ethnographic field notes (Spradley, 1979). The second form of data was two 90-minute video recordings of the focus groups themselves. The audio components of the recording were professionally transcribed resulting in 85 pages of transcript for both groups. Transcripts were uploaded to Atlas.ti software (Muhr, 1999) to facilitate data management and analysis.

Charmaz's (2006) constructionist grounded theory was particularly well suited for this analysis. Constructionist grounded theory is sensitive to language not merely as a reflection of members’ views and values but as part of an active social process that constructs them. When language is used in combination with other actions, interactions, ways of thinking, believing, and valuing to enact a socially recognizable identity, it can be called discourse (Gee, 2011). For example, when discussing a health care encounter a participant can simultaneously describe it, reflect on the relationships within it, and recognize how it fits into a personal narrative. What participants say and how they say it can be used to empirically ground how discourse constructs multiple social and medical phenomena into more abstract terms, which is one goal for middle-range theorizing (Charmaz, 2006).

To construct these discourses, we first expanded our field notes (Spradley, 1979) to generate initial analytic findings. Field notes indicated that participants repeatedly initiated discussions about diet as relevant to nearly every research domain. Thus, we used diet as a sensitizing concept to begin our analysis (Charmaz, 2006). Next, we segmented each transcript into individual speaker turns at talk (Sacks, Schegloff, & Jefferson, 1979), our basic unit of analysis. We watched each focus group three times to reimmerse ourselves into the event. While watching, we open-coded transcripts to identify candidate instances of participants’ talk about diet, dietary habits, and nutrition. Using the recordings and transcripts together allowed us access to spoken meanings, such as marked intonation, pauses, and humor, that might not have been represented using the transcript alone. We compared candidate instances for similarities and differences and then sorted similar items into collections (ten Have, 1999), a tentative grouping using maximal variation sampling of data to provide a subset of cases for further analysis. By paying close attention to deviant cases, we integrated the collection theoretically using Appadurai's (1981) dialectic between homogeneity and heterogeneity. Throughout the process, two physicians with clinical and research expertise in Asian Indian communities (LP, NK) provided help contextualizing findings within the communicative ecology of both cultural community and medical practice (Roberts & Sarangi, 2005). Through our analysis we show how cultural members construct discourses about the importance of diet and its relationship to health and their interpersonal encounters with health care providers.

ANALYSIS

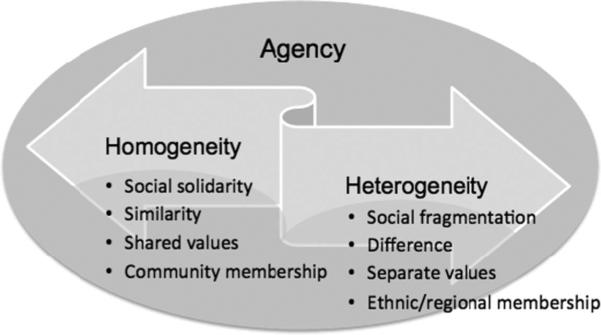

Our analysis demonstrates that community members associated health meanings around diet as an important component of creating and maintaining community identity. However, Asian Indian community members’ dietary health meanings are contradictory discursive constructions whose complexity is not understood by U.S. health care providers. When reflecting on their experiences with health care, participants critiqued medical providers because they emphasized biomedical dietary values while simultaneously deemphasized the community's cultural dietary values. We expose this discursive marginalization by documenting community members’ lived experience to open a communicative space that provides community members the opportunity to voice the impact of being silenced on community-level health. We use Appadurai's dialectic between homogeneity and heterogeneity (see Figure 2) to show how the community members’ agency is constrained by biomedical dietary health meanings.

FIGURE 2.

Dietary health meanings are a form of social practice through which community members enact agency as a dialectic between homogeneity, or social solidarity, and heterogeneity, or social fragmentation, as a discursive form of agency.

Dietary Solidarity in Everyday Asian Indian Life

Throughout the focus groups, participants discursively constructed themselves as culturally similar to one another. Participants expressed discursive homogeneity when they affirmed common community values and a unified Indian cultural identity that differentiated them from other American cultures. Dristi, a researcher from a large, local university, articulated these community values through a critique of U.S. health care providers:

Extract 1. Dristi (32-year-old female, 8 years in United States) I think, fundamentally, they [providers] do not understand that we are not [like] Americans—that our bodies are different. They are understanding, they try to help but . . . because our metabolism is different, our diet is different, our stress levels are different, our family life is different. So they want to help but I just think that they . . . simply were not educated on those things. I mean, for example, doctors in India, how would they know how a typical American body is? I think you would get much better health care if the doctors would really know where you're coming from.

Dristi critiques medicine as an institutional practice in two ways. From her perspective, health care providers do not recognize biological differences between populations. While routine medical practice is informed by research findings that assume consistency across populations, she recognizes that at least one biological difference—metabolic rate— differentiates the American from Asian Indian body. She uses first-person plural pronouns to demonstrate shared membership and differentiates what is “ours” from other “Americans.” Note that diet is specifically mentioned as one aspect of what unifies her community while differentiating it from others.

Second, while acknowledging the system's beneficent intentions, Dristi recognizes that providers may not understand how sociocultural context, such as dietary patterns, stress levels, and family life, may affect her community's health. From her perspective biomedicine does not recognize the dynamic nature of culture and the situational nature of context as significant for community members and their associated health status. For Dristi, context matters because she feels providers do not “really know where you're coming from.” She illustrates her critique through a rhetorical perspective shift: How would an Indian doctor know what a typical American body would be like? Because health care providers use a normative model of medicine that fits neither her nor her community's health care needs, Dristi's articulates how cultural members experience the absence of voice. This provides an entry point for foregrounding narratives within health care structures by highlighting the differences between the community and biomedical cultures as a locus for social action.

One of the main ways participants felt their voices silenced was through lack of awareness of culturally unique dietary patterns, which often resulted in inappropriate dietary advice during health care encounters. Primary care providers often recommend dietary modification to help manage and improve chronic health conditions, such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes. Many participants recounted experiences in which providers recommended inappropriate dietary advice, assuming that the community members’ dietary choices were identical to the average American's diet. A computer engineer from North India, Ratnesh, critiques the assumption that community members adhere to dietary habits similar to other Americans:

Extract 2. Ratnesh (35-year-old male, years in United States unknown) They [i.e., providers] use examples where it was not really meant for South Asians. Their advice is totally way off, like generally, we don't eat pizzas or burgers, you know, all kinds of pastries and chocolate. And all of those things we don't eat. So . . . it doesn't really make any sense.

While Ratnesh understands that certain foods should be avoided to maximize health, he problematizes moments when providers might employ examples of “American” foods because many community members do not consume these foods. Where other Americans eat pizza or burgers, members of the Asian Indian community differentiate themselves through what “we don't eat,” specifically, pizza, burgers, pastries, and chocolate. For Ratnesh, culture is articulated through his ability to make practical, normative dietary choices in response to multiple competing demands of real-time situations. While he displays knowledge that daily dietary choices have health consequences, he recognizes that not all discourses are equal within the health care structure. Because providers recommend dietary choices rooted in biomedicine rather than community preferences, Ratnesh feels his voice—and the voice of his community—to be excluded from the dominant space of medical practice.

Other participants upgraded this critique by affirming that U.S. health care providers did not understand a particular aspect of their routine dietary behavior—their dietary restrictions. Many Asian Indians voluntarily restrict their diet by omitting all meat and animal-derived products as external signs of internal ethical considerations. Several participants considered dietary restrictions an important aspect of their cultural identities and a daily form of social action that had cascading effects on every aspect of routine dietary behavior. Community members displayed mistrust of providers who lacked knowledge of significant diet-related habits, such as dietary restrictions. Vaishali, an emigrée who frequently returns to India, emphasized how providers’ lack of knowledge undermined a working therapeutic alliance:

Extract 3. Vaishali (35-year-old female, years in United States unknown) Is this person [i.e., provider] going to have a clue about what my eating habits are, what foods I eat, what restrictions I have, right? And even things like plant oil versus fish oil . . . So, I want to know what their awareness is.

Vaishali rhetorically asks whether providers will have “a clue” about her dietary habits, including the foods she does and does not eat as well as her dietary restrictions. She articulates her critique by using a specific example—plant oil versus fish oil. Primary care providers commonly recommend dietary supplements, such as fish oil, to many patients to help reduce risk of heart disease and high blood pressure. However, for many Asian Indians, fish oil is unacceptable due to dietary restrictions that prohibit consumption of animal-derived products of any kind. By contrasting plant oil with fish oil, Vaishali actively resists the taken-for-granted biomedical recommendation. From her perspective, providers are the ones who must prove themselves knowledgeable before they can relevantly help co-manage her health. Using her own experience as the crucible of relevance, she interrogates the assumptions of biomedical practice as the dominant structure of dietary health meanings and creates a discursive space of resistance that ruptures the dominant discourse of routine medical practice.

This section showed that diet plays a significant role in cultural members’ daily lives. Health meanings around diet were constructed through discursive homogeneity in which dietary solidarity framed community members as fundamentally similar to one another but in contrast to other Americans and normative biomedical practice. This contrast was evident from participants’ perceptions that providers have limited knowledge about their everyday dietary practice. Participants reported that providers disattended local dietary health meanings by prioritizing biomedical dietary health meanings, thereby excluding community members’ voice. Through their accounts, participants foregrounded their dietary experience and exposed a communication rift between cultural and biomedical community cultures. Participants demonstrated themselves as willing participants to make important dietary changes. However, in order to do so, health care structures must be open to critical interrogation by the community to create a shared communicative space in which the silenced voices may speak for themselves.

Dietary Fragmentation in Everyday Asian Indian Life

While participants discursively constructed their dietary practice as culturally similar to one another through dietary solidarity, they contradictorily constructed their dietary practice as culturally different from one another as well. Participants enacted heterogeneity when they discursively emphasized dietary differences from one another, which served to fragment community members from one another, but not necessarily from biomedical dietary norms. Asian Indian communities can be fragmented along multiple dimensions, as Reneeka, an emigrée from Mumbai, articulated:

Extract 4. Reneeka (33-year-old female, 7.5 years in the United States) It's very difficult [even] as Indians to understand what people are eating in North India and what people are eating in South India. If they [e.g., providers] talk to Indian patients, not the American South Asians, I think they will have a good understanding of what kind of food we have.

Reneeka uses diet as a key locus to articulate at least two aspects of difference within the community. First, she differentiates dietary diversity based on regional differences within India. North, Central, and South Indian regions all have unique languages, identities, and dietary habits and customs. Being a community member means knowing about the differences between regions and learning not to make assumptions about cultural similarities between groups. Second, Reneeka recognizes another source of difference when she distinguishes between “Indian patients” and “American South Asians.” As a separate source of diversity, this distinction differentiates community members who have lived major portions of their lives in India from either those who have lived in the United States for a long period of time or those who may claim Asian Indian identity through heritage. Diet exemplifies a second source of difference by identifying a tension between regional and global differences based in an explicit recognition of the plurality of dietary practice within the community. From this perspective, dietary practice is firmly grounded in cultural politics not only within India but also within the Indian diaspora. In contrast to the discursive solidarity elaborated in the previous section, heterogeneity contributes to another aspect of the complex and contradictory discursive constructions around dietary health meanings for the Asian Indian community through dietary fragmentation, which providers may not know and which may lead to misunderstanding about Asian Indian dietary practice.

While regional differences among Asian Indian populations may be a more familiar form of heterogeneity, participants articulated unique forms of dietary fragmentation based in differences in life-course trajectories, transnational migration experiences, and length of stay both inside and outside India. Three types of dietary discourse were evident. Participants making up a first group were born in and lived in India for much of their lives and articulated health meanings rooted in religious and folk medical traditions. Those in a second group of participants may have been born in India but grew up and lived outside India for the majority of their lives and espoused mixed diets based on the cultural influences they may have experienced due to living in different cultural environments in different periods of their lives. Participants making up a final group were born and lived outside India and retained an Asian Indian identity, and employed biomedical critiques of what they considered received community cultural norms around diet. Each group formulated distinct values according to distinct theories of health and illness as enacted by routine dietary habits.

Participants who lived much of their lives in India and immigrated to the United States as adults perceived their dietary practices to be at odds with contemporary medical practice. These participants were more likely to espouse religious Hinduism and adhered to stringent vegetarian dietary restrictions. Nandini, who lived much of her life in Hyderabad, South India, articulates dietary health meanings that establish continuity between her and her ancestors:

Extract 5. Nandini (64-year-old female, 20 years in the United States) I think the way we eat there [in India] suits there. It suited very much. The typical, after coming to the U.S., everything we eat, everything we do turns out to be wrong. [laughter] But then, what I noticed when we watched our grandparents and our in-laws and everybody who almost lived up to almost close to 90 or middle 80s, I started to think, you know.

Nandini valorizes a time-honored Hindu diet because relatives who adhered to a similar diet live long, healthy lives. However, this diet appears only to be valid in India, as these patterns “turn out to be wrong” from a biomedical perspective. The result is that this participant finds it difficult to reconcile what she considers a healthy diet according to biomedical and cultural traditions. Other members of this group similarly challenged biomedical dietary values because cultural dietary values help provide stability and cultural uniqueness amid modernization and change. From this perspective, culture and habit may be at odds with contemporary biomedical practice because diet is more than a combination of nutrients. Rather, diet is an important way to nourish a way of being in the world that affirms not only established cultural values as expressed through daily dietary choice, but also a vital link with the past. Nandini contextualizes her critique in her personal history, thereby challenging the dominant discourse in light of what she has observed in her own family. Through this skepticism, she actively questions the relevance of biomedical knowledge in light of what is culturally familiar, which transforms her relationship to structure.

Participants who were born in India but immigrated as children differentiated themselves from the previous group by embracing a mixed diet that combined cultural and Western influences. Their dietary practices tended to blend aspects of Asian Indian culture with the culture(s) in which they grew up and currently live in as adults. Members of this group felt their voices being silenced through “typecasting,” or stereotyping. Stereotyping occurred when providers perceived members to be both “more Indian” or “less Indian” than their actual behavior demonstrated. Kajit, who was born in and lived in India but grew up in the Philippines before immigrating to the United States, demonstrated sensitivity to stereotyping:

Extract 6. Kajit (40-year-old male, 30 years in the United States) I think one of the problems . . . is that you're typecast. Okay, for instance if one guy says that his kids were born in India but [they] don't like Indian food, okay? If they were to go to the doctor, and he would see “South Asian,” and [the doctor would] send him off to PRANA. And they would say, “Okay, don't eat those spicy leaves or whatever.” And the kid would just say, “Hey, I don't eat that anyway.”

Kajit presents a hypothetical scenario to illustrate the process through which he feels providers stereotype individuals like himself. In this scenario, an imaginary child of Asian Indian parents who does not like Indian food, despite having been born in India, visits a physician. When the physician learns of the child's ethnicity and life-course trajectory, Kajit proposes the physician would presume a purely Indian diet and refer him to a health program designed to help recent Asian Indian immigrants. Once in the program, this child would likely receive advice that does not fit his actual dietary practices. This scenario shows the ways in which different contexts support different forms of agency, including dietary choice, which changes over time and circumstances. Because providers often are not aware of how context shapes agency through a life course, they often make recommendations based on stereotypical assumptions about community members based on little personal information. Kajit's critique is that providers are not often aware of the ways in which agency and social context are constitutive elements of culture that constructs different kinds of relationships toward structure, which impacts health both at an individual and at a community level.

Finally, participants born outside of India differentiated themselves from the two other groups by voicing health meanings that affirmed the dominant biomedical and American cultural discourses. While these participants asserted an Asian Indian identity, they also expressed biomedical values by critiquing community norms around dietary practice. In the following extract, Somila, who was born in the United States and identifies herself as both “American” and “Indian,” adopted a critical attitude towards her received culture:

Extract 7. Somila (30-year-old female, born in the United States) What I've noticed with family and family friends, is the fat in the Indian food and lack of portion control. Even though I'm not in India, I mean, even here or whenever we got our friends or family friends and my in-laws, it's all about, “You need to eat, you're not eating, you're not eating.” I'm like, “Well, I'm eating. I'm done.” One of those little gluten wheat things is more than enough, but they don't understand that one is enough or half a cup of one of these vegetable entrees is more than enough. But they don't understand that.

Similar to other community members, Somila recognizes the health importance of diet. However, although other participants affirmed the social solidarity of dietary choices, Somila articulated two factors that limit her community's health: knowledge of basic nutritional principles and oppressive social customs. She employs the language of nutrition, specifically, the nutrient (fat) and portion size (one-half cup), as a way to affirm her alignment with the biomedical perspective. Additionally, she mentions the guest–host relationship as a social factor that contributes to difficulties of being Asian Indian, namely, that hosts encourage guests to eat heartily to solidify rapport and show respect. Together, she experiences these two received dietary values as oppressive and as contributing to unhealthy dietary behavior. For Somila, received cultural values—rather than biomedicine—are the source of marginalization that constrains her individual agency and negatively influences community health. Participants in this group supported biomedical dietary discourses as a means to critique received community values. This excerpt demonstrates that, despite affirming an Asian Indian identity, not all community members adopt received or mixed dietary choices, but create ad hoc dietary arrangements to support unique situational contingencies. Rather, some may enact dietary habits closer to other Americans whose health meanings about diet embrace dominant biomedical dietary values.

While the previous section showed that diet can be a source of solidarity, this section contradictorily showed that dietary practice based in life-course trajectories can also serve to fragment community members from one another. As a result of this diversity, participants felt marginalized because health meanings were largely constructed as a result of their various life-course trajectories, many of which were largely unrecognized by normative medical practice. Each member of the community may simultaneously affirm membership in multiple social and cultural groups that serves to fragment a unified Asian Indian identity. While some groups reported that providers emphasize biomedical over community dietary health meanings, some of those who emigrated early in life or who were born outside India also embraced dominant health care structure meanings against received community values. This further shows the contradictory discursive construction of diet as a source of health meaning within the Asian Indian community. Because dietary choice is grounded in multiple geographical contexts over time, it is a pastiche of social practice that includes multiple phenomenological distinctions, including place of birth, past and current residences, and immigration history, within a diverse community. The interrelationships among discourses of dietary fragmentation show that both context and life-course trajectory across time influence community members’ orientation to structure, which varies individual by individual.

Bridging Dietary Solidarity and Dietary Fragmentation in Clinical Practice

This article has argued that Asian Indian dietary health meanings are complex, contradictory discourses that are not well understood by U.S. health care providers. Overall, we argue that health care providers’ lack of knowledge about the cultural context of diet health meanings constrains community members’ agency and marginalizes their voices in health care settings. Participants managed voicelessness by regarding providers with suspicion until providers displayed themselves as knowledgeable about community dietary habits, exposing a rift between patient and provider health communication. Although participants resisted dominant biomedical dietary health meanings, they simultaneously demonstrated themselves to be willing partners in their health care. Participants who critiqued medical practice did so as a first step to co-construct a solution to bridge the communication rift. In the following extract Nagdhar, who was born in the United States to Asian Indian parents, voices how providers can partner with him as an active participant in his health care:

Extract 8. Nagdhar (45-year-old male, born in the United States) If they [providers] understand what our food needs are—and I'll call it that, food needs—then we'll be able to attune what they're trying to get us to do, then that's much better. You know, for instance, a [provider] told me you have to eat this for breakfast or this for lunch or this for dinner, and [it] was out of the realm of what I normally eat, I said forget it. I don't want to try it.

Nagdhar emphasizes the importance of being aware of the community's “food needs” as a way to partner with the community and help improve their overall health. He tells a story about a provider who recommended dietary changes. Because the provider recommended modifications that were incongruent with Nagdhar's usual diet, he disregarded the recommendation. Without basic knowledge of community dietary values, providers cannot tailor their recommendations in ways that are useful to patients. In this sense, the discursive exclusion of community health meanings has material consequences. When biomedical discourse is prioritized over the community's, participants exercise their agency in actively disregarding, and thereby resisting, providers’ recommendations, which can compromise individual and community health. This critique displays resistance as a form of community agency and a response to being rendered voiceless. Supporting previous extracts, this participant recounts a case where biomedical and cultural community discourses around diet are ruptured, and the status quo therapeutic alliance is ineffective. Further, it implies that while participants want to be active partners in their own health care, they want to be partners on their own terms and according to the cultural values that underlie their dietary behavior. This demonstrates a positive transformation to the participant's orientation to the health care structure through mutual understanding of cultural health meanings, which may have significant implications not only for the Asian Indian diaspora, potentially regardless of geographical location, but also for other immigrant populations in diaspora for whom diet plays a significant role in identity, such as Latinos in the United States (Napoles-Springer et al., 2005).

DISCUSSION

In this critical health communication study, we applied a culture-centered framework to understand the complexities of Asian Indian community dietary behavior. Given participants’ emphasis on diet in the focus groups, we examined dietary practice as an important aspect of community members’ everyday lives and identity. We show that health care providers typically encouraged biomedical health meanings, which silenced community voices and discursively marginalized community health. Through our analysis, we interpret Asian Indian dietary choice as a form of identity that is discursively constructed through a dialectical tension between homogeneity, or dietary solidarity, and heterogeneity, or dietary fragmentation. Through these contradictions, we help to make audible health meanings through various discourses about diet.

Community members enacted discursive homogeneity because dietary health meanings differentiated them from other populations living in the United States. Participants perceived that providers often lacked knowledge about Asian Indian culture in general and dietary patterns in particular. Similar to results in Teal and Street (2009), participants in our study wanted options that reflected their preferences and needs around diet, but they often felt they were getting inappropriate dietary advice, which discursively marginalized community members’ voices.

Second, community members’ health meanings enacted discursive heterogeneity because diet served to fragment participants’ health meanings around diet due to differences in life course experience and subgroup membership, which served to differentiate community members from one another. Participants perceived providers to be relatively unaware that birthplace and immigration were important forms of diversity, which were a significant part of their ongoing health care. Effective health communication with Asian Indians must recognize the fluidity of life course events and how these factors can impact communication with Asian Indians’ about health beliefs and behaviors.

The culture-centered approach is a theoretical and methodological framework that advocates a participatory approach to research with the community. This approach rejects imposing health practices to transform behavior from the outside in and advocates affirming cultural members’ worldviews, beliefs, and values as building blocks for meaningful and sustainable change from the inside out (Dutta & Basu, 2007; Ford & Yep, 2003; Guha, 1988; Spivak, 1988). This article contributes to the culture-centered approach in several ways.

First, this article extends how the culture-centered approach can be applied. Although previous research using the culture-centered approach has been conducted outside the United States and within community settings (Basu & Dutta-Bergman, 2007; de Souza, 2009; Dutta-Bergman, 2004a, 2004b; Dutta & Basu, 2007), this study was conducted inside the United States within a medical setting. These innovations demonstrate that the culture-centered approach can be applied both internationally and domestically within the United States as well as in community and medical settings.

Second, this study contributes to the culture-centered approach theoretically through the discursive analysis of agency. By incorporating Appadurai's (1981) dialectic between homogeneity and heterogeneity as analytic technology, we expose the discursive contradictions within a specific cultural community and make them understandable. We emphasize the cultural nature of agency as contextualizing past habits with future action according to the contingencies of the moment, which Emirbayer and Mische (1998) designate as the practical-evaluative element of agency. This conception facilitates the notion of agency not as a potential set of abstract choices, but as part of daily experiences in which cultural participants must make practical and normative judgments in real time. Because cultural members are confronted with biomedical discourses that are largely outside of the community health meanings, participants can articulate a critique of the dominant discourses by recognizing what is absent from the institution, but present for them in their everyday lives. In this sense, diet provides a lens for theorizing the reflexive relationship between community and structure by encouraging cultural members to explore important health meanings in their everyday lives as compared to the health meanings they encounter in institutional health care structures. Because diet is a cultural frame through which experience can be systematically compared, cultural members can affirm their agency by articulating those absences as a response to dominant biomedical discourses based in the actual experience of culturally alternative possibilities.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this study uses a small sample; the study is limited to 15 participants in two focus groups. Additional focus groups or semistructured interviews with community members would likely generate additional findings that could confirm and expand these findings. Second, the study took place in a geographical area where a significant Asian Indian community exists. The health systems that serve this minority population may have structural features that may be unique to this location. Third, although the study is limited to participants from India or whose cultural heritage is Indian, findings may be of limited value for other South Asian ethnicities, such as Pakistanis, Bangaladeshis, Nepalis, and Sri Lankans, who share some dietary characteristics with India. Finally, because we used constructionist grounded theory as an interpretive theoretical framework, other interpretations may be possible.

Conclusion

This exploratory study shows that participants’ experiences with health care offer insight into the relationship between culture, structure, and agency in negotiating discursive health meanings around diet. Our analysis shows that diet is an important aspect of Asian Indian lived experience, but cultural members perceive that providers do not understand their dietary preferences, nor do providers understand the dietary diversity within the community. As a result, cultural members experience an absence from the structural environment of the health care system, which serves to discursively marginalize community members’ voices. By exposing this absence, we help create a discursive space to give voice to community values that are not recognized by the status quo in an effort to transform community health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Palo Alto Medical Foundation Quality and Planning Division for commissioning the focus groups. The authors also thank Elsie Wong for her insightful comments on previous drafts of this article.

Footnotes

Previous research has used the term “South Asian” to refer to people with origins in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, and may include Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bhutan. However, because more than 85% of the South Asian population in the United States derives ancestry from India, the U.S. Census has adopted “Asian Indian” in its Asian subcategories to refer to this group.

Contributor Information

Christopher J. Koenig, Department of Medicine University of California, San Francisco

Mohan J. Dutta, Department of Communication Purdue University

Namratha Kandula, Department of Medicine Feinberg School of Medicine.

Latha Palaniappan, Department of Health Policy Research Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute.

REFERENCES

- Airhihenbuwa C. Health and culture: Beyond the Western paradigm. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai A. Gastro-politics of Hindu South Asia. American Ethnologist. 1981;8:494–511. [Google Scholar]

- Basu A, Dutta-Bergman M. Centralizing context and culture in to co-construction of health: Localizing and vocalizing health meanings in rural India. Health Communication. 2007;21:187–196. doi: 10.1080/10410230701305182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogni CA, Connors M, Devine CM, Sobal J. Who we are and how we eat: A qualitative study of identities in food choice. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2002;34:128–139. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman GE, Ristovski-Slijepcevica S, Beagan BL. Meanings of food, eating and health in Punjabi families living in Vancouver, Canada. Health Education Journal. 2010;70:102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practice guide through qualitative analysis. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cheek J. At the margins? Discourse analysis and qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research. 2004;14:1140–1150. doi: 10.1177/1049732304266820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza R. Creating “communicative spaces”: A case of NGO community organizing for HIV/AIDS prevention. Health Communication. 2009;24:692–702. doi: 10.1080/10410230903264006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit AA, Azar KM, Gardner CD, Palaniappan LP. Incorporation of whole, ancient grains into modern Asian Indian diet to reduce the burden of chronic disease. Nutrition Review. 2011;69:479–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00411.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta MJ, Basu A. Health among men in rural Bengal: Exploring meanings through a culture-centered approach. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17:38–48. doi: 10.1177/1049732306296374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta-Bergman M. Poverty, structural barriers and health: A Santali narrative of health communication. Qualitative Health Research. 2004a;14:1–16. doi: 10.1177/1049732304267763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta-Bergman M. The unheard voices of Santalis: Communicating about health from the margins of India. Communication Theory. 2004b;14:237–263. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta M. Communicating health: A culture-centered approach. Polity Press; London: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Emirbayer M, Mische A. What is agency? American Journal of Sociology. 1998;103:962–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Ford LA, Yep G. Working along the margins: Developing community-based strategies for communicating about health with marginalized groups. In: Thompson T, Dorsey A, Miller K, Parrott R, editors. Handbook of health communication. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. A241–261. [Google Scholar]

- Gee JP. An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory & method. 3rd ed. Routledge; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Polity Press; Cambridge, UK: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Guha R. The prose of counter-insurgency. In: Guha R, Spivak GC, editors. Subaltern studies. Oxford University Press; New Delhi, India: 1988. pp. 45–86. [Google Scholar]

- Holland AT, Wong EC, Lauderdale DS, Palaniappan LP. Spectrum of cardiovascular diseases in Asian American racial/ethnic subgroups. Annals of Epidemiology. 2011;8:608–614. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra P, Srinivasan S, Ivey S, Greenlund K. Knowledge and practice: The risk of cardiovascular disease among Asian Indians. Results from focus groups conducted in Asian Indian communities in Northern California. Ethnicity and Disease. 2004;14:497–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandula NR, Diez-Roux AV, Chan C, Daviglus ML, Jackson SA, Ni H, Schreiner PJ. Association of acculturation levels and prevalence of diabetes in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1621–1628. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandula NR, Lauderdale DS, Baker DW. Differences in self-reported health among Asians, Latinos, and non-Hispanic whites: The role of language and nativity. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;3:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane W. Voice. In: Duranti A, editor. Key terms in language and culture. Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2001. pp. 268–271. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert H. The cultural logic of Indian medicine: Prognosis and etiology in Rajasthani popular therapeutics. Social Science & Medicine. 1992;34:1069–1076. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton J, Ahmad N, Hanna L, Douglas M, Bains H, Hallowell N. ‘We should change ourselves, but we can’t’: Accounts of food and eating practices amongst British Pakistanis and Indians with type 2 diabetes. Ethnicity & Health. 2008;13:305–319. doi: 10.1080/13557850701882910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauderdale DS, Rathouz PJ. Body mass index in a US national sample of Asian Americans: Effects of nativity, years since immigration and socioeconomic status immigration and socioeconomic status. International Journal of Obesity. 2000;24:1188–2000. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss C, Wightman J, Weightman D. Trans. Penguin; New York: 1966a/1969. The raw and the cooked. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss C, Brooks P. The culinary triangle. Partisan Review. 1966b;33:586–596. [Google Scholar]

- Lupton D. Toward the development of a critical health communication praxis. Health Communication. 1994;6:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Palaniappan L, Wong EC, Shin J, Fortmann SP, Lauderdale DS. Asian Americans have a greater prevalence of metabolic syndrome despite lower body mass index. Circulation. 2009a;119(10):E363–E63. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palaniappan LP, Wong EC, Shin JJ, Moreno MR, Otero-Sabogal R. Collecting patient race/ethnicity and primary language data in ambulatory care settings: A case study in methodology. Health Services Research. 2009b;44:1750–1761. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen S, Karuppaswamy N, Natrajan R. Immigration as a dynamic experience: Personal narratives and clinical implications for family therapists. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2005;27:403–414. [Google Scholar]

- Messer E. Anthropological perspectives on diet. Annual Review of Anthropology. 1984;13:205–249. [Google Scholar]

- Mintz SW, Du Bois CM. The anthropology of food and eating. Annual Review of Anthropology. 2002;31:99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Muhr T. Atlas.ti (release 6.1) software. Scientific Software; Berlin, Germany: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Napoles-Springer AM, Santoyo J, Houston K, Perez-Stable EJ, Stewart AL. Patients’ perceptions of cultural factors affecting the quality of their medical encounters. Health Expectations. 2005;8:4–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Mary S, Mukesh B, Bhaskar AD, Vijay V, Indian Diabetes Prevention Program (IDPP) The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programe shows that lifestyle modification and metformin prevent type 2 diabetes in Asian Indian subjects with impaired glucose tolerance (IDPP-1). Diabetologia. 2006;49:289–297. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0097-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C, Sarangi S. Theme-oriented discourse analysis of medical encounters. Medical Education. 2005;39:632–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks H, Schegloff EA, Jefferson G. A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language. 1979;50:696–735. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Institute of Medicine; Washington, DC: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spivak GC. Can the subaltern speak? In: Nelson C, Grossberg L, editors. Marxism and the interpretation of culture. University of Illinois Press; Urbana: 1988. pp. 271–313. [Google Scholar]

- Sobal J, Bisogni CA. Constructing food choice decisions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;38(Supp1):S37–S46. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradley JP. The ethnographic interview. Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.; San Francisco, CA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Teal CR, Street RL. Critical elements of culturally competent communication in the medical encounter: A review and model. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:533–543. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Have P. Doing conversation analysis: A practical guide. Sage; London: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wang EJ, Wong EC, Dixit AA, Fortmann SP, Linde RB, Palaniappan LP. Type 2 diabetes: Identifying high risk Asian American subgroups in a clinical population. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2011;93:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong EC, Palaniappan LP, Lauderdale DS. Using name lists to infer Asian racial/ethnic subgroups in the healthcare setting. Medical Care. 2010;48:540–546. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d559e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]