Abstract

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a complex and heritable eating disorder characterized by dangerously low body weight. Neither candidate gene studies nor an initial genome wide association study (GWAS) have yielded significant and replicated results. We performed a GWAS in 2,907 cases with AN from 14 countries (15 sites) and 14,860 ancestrally matched controls as part of the Genetic Consortium for AN (GCAN) and the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 3 (WTCCC3). Individual association analyses were conducted in each stratum and meta-analyzed across all 15 discovery datasets. Seventy-six (72 independent) SNPs were taken forward for in silico (two datasets) or de novo (13 datasets) replication genotyping in 2,677 independent AN cases and 8,629 European ancestry controls along with 458 AN cases and 421 controls from Japan. The final global meta-analysis across discovery and replication datasets comprised 5,551 AN cases and 21,080 controls. AN subtype analyses (1,606 AN restricting; 1,445 AN binge-purge) were performed. No findings reached genome-wide significance. Two intronic variants were suggestively associated: rs9839776 (P=3.01×10-7) in SOX2OT and rs17030795 (P=5.84×10-6) in PPP3CA. Two additional signals were specific to Europeans: rs1523921 (P=5.76×10-6) between CUL3 and FAM124B and rs1886797 (P=8.05×10-6) near SPATA13. Comparing discovery to replication results, 76% of the effects were in the same direction, an observation highly unlikely to be due to chance (P=4×10-6), strongly suggesting that true findings exist but that our sample, the largest yet reported, was underpowered for their detection. The accrual of large genotyped AN case-control samples should be an immediate priority for the field.

Keywords: anorexia nervosa, eating disorders, GWAS, genome-wide association study, body mass index, metabolic

Introduction

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a perplexing biologically-influenced psychiatric disorder characterized by the maintenance of dangerously low body weight, fear of weight gain, and seeming indifference to the seriousness of the illness.1 AN affects ∼1% of the population.2, 3 Females are disproportionately afflicted, although males also develop the condition.4 The most common age of onset is 15-19 years;5 however, the incidence appears to be increasing in the pre-pubertal period6 and in older adults.7 AN is often comorbid with major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, and multiple somatic complications.8-12 Although most individuals recover, ∼25% develop a chronic and relapsing course.13 AN ranks among the ten leading causes of disability among young women14 and has one of the highest mortality rates of any psychiatric disorder.15-19 The evidence base for treatment for AN has been described as “weak,”20, 21 and treatment and extended inpatient hospitalizations for weight restoration are costly.22, 23 In sum, the public health impact of AN is considerable, and AN carries substantial morbidity, mortality, and personal, familial, and societal costs.

As with most idiopathic psychiatric disorders, the inheritance of AN is complex. The core features of AN [i.e., the ability and determination to maintain low body mass index (BMI)] are remarkably homogeneous across time and cultures.24, 25 Genetic epidemiological studies have documented the familiality of AN (relative risk 11.3 in first-degree relatives of AN probands)26, 27 and the estimated twin-based heritability of AN ranges from 33 to 84%.28-32 Genome-wide linkage studies did not narrow the genomic search space in a compelling manner.33-35 Findings from candidate gene studies of AN resemble those for most complex biomedical diseases—initial intriguing findings diminished by the absence of rigorous replication.36-38

Given the centrality of weight dysregulation to AN, genes implicated in the regulation of body weight might also be involved in the etiology of AN.39, 40 Therefore genetic variants with a profound effect on BMI are worthy of consideration.38

Two genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of AN have been conducted. One study that used DNA pooling and genotyping with a modest number of microsatellite markers with follow-up genotyping detected evidence for association with rs2048332 on chromosome 1, but this finding did not reach genome-wide significance.41 A GWAS of 1033 AN cases from the USA, Canada, and Europe compared with 3733 pediatric controls yielded no genome-wide significant findings.42 Recently, a sequencing and genotyping study of 152 candidate genes in 1205 AN cases and 1948 controls suggested a novel association of a cholesterol metabolism influencing EPHX2 gene with susceptibility to AN.43

In recognition of the need for large-scale sample collections to empower GWAS, we established the Genetic Consortium for Anorexia Nervosa (GCAN) in 2007—a worldwide collaboration combining existing DNA samples of AN patients into a single resource. As part of the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 3 (WTCCC3), we have conducted the largest GWAS for AN to date.

Materials and Methods

Discovery dataset

We conducted a GWAS across 15 discovery datasets, comprising a total of 2,907 AN cases and 14,860 ancestrally matched controls of European origin (Table 1). All AN cases were female. Diagnostic determination was via semi-structured or structured interview or population assessment strategy based on DSM diagnostic criteria. Cases met DSM-IV criteria for lifetime AN (restricting or binge-purge subtype) or lifetime DSM-IV eating disorders “not otherwise specified” (EDNOS) AN-subtype (i.e., exhibiting the core features of AN). We did not require the presence of amenorrhea as this criterion does not increase diagnostic specificity.44, 45 Given the frequency of diagnostic crossover, a lifetime history of bulimia nervosa was allowed.46 Exclusion criteria included the diagnosis of medical or psychiatric conditions that might have confounded the diagnosis of AN (e.g., psychotic disorders, mental retardation, or a medical or neurological condition causing weight loss). Controls were carefully selected to match for ancestry within each site and chosen primarily from existing GWAS genotypes through collaboration and genotyping repository (dbGAP) access. Each site obtained ethical approval from the local ethics committee, and all participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1. List of ethnicities and numbers of samples for main case control and anorexia nervosa (AN) subtype analyses across discovery and replication datasets.

| Country | Cases (% of females) | AN RESTRICTING subtype cases | AN BINGE-PURGE subtype cases | Controls (% of females) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery dataset* | ||||

| Canada | 54 | 24 | 25 | 417 (46.52) |

| Czech Republic | 72 | 40 | 29 | 331 (35.04) |

| Finland | 131 | 39 | 29 | 404 (100) |

| France | 293 | 137 | 135 | 619 (60.09) |

| Germany | 475 | 147 | 55 | 1,205 (49.13) |

| Greece | 70 | 10 | 5 | 79 (100) |

| Italy-North | 203 | 103 | 99 | 841 (52.19) |

| Italy-South | 75 | 31 | 26 | 52 (100) |

| Netherlands | 348 | 115 | 90 | 593 (51.26) |

| Norway | 82 | 24 | 15 | 602 (67.44) |

| Poland | 175 | 68 | 107 | 564 (29.43) |

| Spain | 186 | 45 | 44 | 185 (75.14) |

| Sweden | 39 | 28 | 11 | 975 (72.10) |

| UK | 213 | 97 | 97 | 5,163 (49.43) |

| USA | 491 | 311 | 165 | 2,830 (41.31) |

| Total discovery | 2,907 | 1,219 | 932 | 14,860 (51.73) |

| In silico replication | ||||

| USA-Hakonarson | 1,033 (97.67) | 0 | 0 | 3,775 (45.85) |

| Estonia | 31 (100) | 0 | 0 | 106 (100) |

| De novo replication | ||||

| Austria | 48 (100) | 0 | 0 | 183 (65.03) |

| Czech Republic | 32 (71.88) | 0 | 0 | 22 (100) |

| Finland | 15 (100) | 0 | 0 | 94 (8.51) |

| France | 55 (100) | 0 | 0 | 123 (100) |

| Germany | 174 (99.43) | 31 | 64 | 380 (66.84) |

| Greece | 16 (100) | 0 | 0 | 53 (100) |

| Italy-South | 156 (96.79) | 32 | 24 | 63 (100) |

| Netherlands | 229 (100) | 45 | 23 | 380 (27.11) |

| Poland | 52 (98.08) | 0 | 0 | 93 (100) |

| Spain | 10 (100) | 0 | 0 | 328 (41.46) |

| UK | 155 (100) | 28 | 55 | 199 (65.83) |

| USA** | 671 (100) | 349 | 272 | 2,830 (41.31) |

| Japan | 458 (100) | 213 | 240 | 421 (100) |

| Total replication | 3,135 (98.72) | 698 | 678 | 9,050 (50.08) |

| Total global meta-analysis | 5,551 | 1,606 | 1,445 | 21,080 |

All AN cases from discovery dataset were females.

USA samples from discovery dataset were merged together with USA replication samples for replication analysis. The same USA control dataset was used.

Genotyping, imputation and quality control

AN cases from the 15 sites were genotyped using Illumina 660W-Quad arrays (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. Funding was available only for genotyping AN cases. Thus, control genotypes were selected from existing datasets matched as closely as possible to the ancestry of cases and Illumina arrays as similar as possible to the 660W array (Table S1). Quality control (QC) of directly typed variants was performed within each of the 15 case-control datasets (Table S2, Supplementary Information).

Phasing and imputation was performed separately for each of the 15 datasets using a common set of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) passing QC (Table S2) using the program Impute2 v2.1.2 (Supplementary Information).47 The imputation reference panel was HapMap 3 release 2. We used all available HapMap3 populations for imputation as it was shown that the increase in the reference panel decreases error.48, 49 Post-imputation filters were applied to remove SNPs with INFO scores < 0.4 or with MAF < 0.05. We observe high imputation accuracy (as captured by the INFO score) across a range of minor allele frequencies (Figure S1). There was high concordance between directly genotyped variants with imputed dosages of the same variants after masking (Figure S2).

Statistical analysis

Single-SNP association analyses were performed under an additive genetic modelseparately within each of the 15 datasets (Supplementary Information). We tested for association across the autosomes and the non-pseudoautosomal region of the X chromosome. Imputation and association analysis of the non-pseudoautosomal region of the chromosome X data were based on females (2,907 AN cases and 10,594 controls). Association analyses were performed using SNPTEST v2.2.049 under an additive model and using a score test. To guard against false positives due to population stratification, we carried out association analysis within each dataset and then combined the results using meta-analysis (for the French dataset, the first principal component was added as a covariate). Fixed-effects meta-analyses were performed using GWAMA.50 All 15 discovery datasets were corrected for the genomic control (GC) inflation factor (λGC) prior to performing meta-analysis (Table S2; Supplementary Information).

Replication

We prioritized directly genotyped and imputed SNPs for replication based on statistical significance (P < 10-4), robust QC metrics, and vicinity to plausible candidate genes. In total 96 SNPs (95 autosomal and one on chromosome X) in 66 genomic regions showed nominal evidence for association. We selected 72 independent, uncorrelated variants representing each of the 66 associated genomic regions and added 4 proxies for the most associated SNPs resulting in 76 SNPs for replication. Cluster plots of all prioritized SNPs were examined using Evoker51 in cases and controls separately to minimize the possibility of spurious association due to genotyping error. We included 27 ancestry-informative markers (AIMs) for genotyping in the replication datasets, to guard against population stratification (Supplementary Information).52

Our replication data included 15 datasets—two existing in silico datasets and 13 datasets for de novo genotyping (Table 1). The in silico dataset from the USA came from an existing GWAS of AN genotyped using the Illumina HumanHap610 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA)53 and the other in silico dataset came from Estonian Genome Center (www.biobank.ee) and was genotyped using the Illumina OmniExpress array. De novo genotyped samples included newly collected AN cases and controls from members of the GCAN and samples from the same sites as the discovery samples that had failed GWAS QC (including saliva and whole genome amplified samples). De novo SNP genotyping was carried out using the iPLEX Gold Assay (Sequenom, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). SNPs with poor Sequenom design metrics were replaced with high-LD proxies. Sample and SNP QC were performed within each replication dataset. QC included checking for sex inconsistencies and exclusions based on sample call rate <80%, SNP call rate <90% and exact Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) p<0.0001. In total, replication genotypes (in silico and de novo) of 76 prioritized SNPs and 27 AIMs were available from 2,677 AN cases and 8,629 controls of European ethnicity and 458 AN cases and 421 controls from Japan.

Association analyses of prioritized SNPs were performed under an additive genetic model within each replication dataset with and without adjustment for AIMs. AIMs that showed nominally significant p-values for allele frequency differences between de novo typed cases and controls were used for conditional analysis (Table S3). As there were no qualitative differences between these results, the main text reports the unadjusted results. The USA replication dataset contained individuals who were related to individuals from the USA discovery dataset. As such, those samples were excluded from the discovery dataset and combined with replication USA samples to correctly account for relatedness between samples for the final global meta-analysis and sign test. Software packages GenABEL54 and GEMMA55 were used for replication analysis of the USA dataset. Fixed-effects meta-analysis across the replication datasets was performed using GWAMA50 (with and without adjustment for AIMs and in samples of European ancestry only, i.e., excluding Japan, also with and without adjustment for AIMs). We also performed meta-analyses across the discovery and replication datasets, comprising a total of 5,551 AN cases and 21,080 controls (USA discovery samples were included only once as part of the replication phase). We calculated the power of the final global meta-analysis using QUANTO.56

Seventy-two independent SNPs were used to compare the direction of effects between the discovery and replication meta-analyses using R.57 For this analysis, the USA samples were used only once as part of the replication meta-analysis.

Additional analyses

We performed three additional analyses: 1) genome-wide complex trait analysis (GCTA), designed to estimate the proportion of phenotypic variance explained by genome-wide SNPs for complex traits,58 a network analysis, and a gene-based association test (Supplementary Information).

AN subtype analyses

Two subtype (Supplementary Information) association analyses were performed for the 76 prioritized SNPs across the discovery and replication datasets (Table 1). In total, the AN restricting subtype global meta-analysis included 1,606 cases and the AN binge-purge subtype analysis included 1,445 cases. Both analyses used the same set of 16,303 controls (Supplementary Information).

Related traits

Using the discovery meta-analysis, we investigated evidence for association using SNP results from published studies: 9 SNPs with nominal evidence of association with AN;42 14 SNPs suggestively associated with eating disorder-related symptoms, behaviors, or personality traits;59, 60 89 SNPs with genome-wide significance in studies of BMI or obesity;61, 62 and 15 SNPs related to morbid obesity.61 We also investigated evidence for association across the 72 replication SNPs using published GWAS results from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (https://pgc.unc.edu) for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder.63-66

Expression studies

We prioritized the top 20 SNPs in terms of statistical significance and quantified the expression of the two nearest genes per SNP (Table S4) in 12 inbred strains of mice. We obtained publicly available RNAseq data from whole brain tissue samples and used standard software to map and count the sequence reads (Supplementary Information).

Results

Main association results

Of 1,185,559 imputed SNPs that passed QC, 287 showed evidence for association in the discovery stage with P < 10-4. These variants represented 66 independent signals and had frequencies and effect sizes commensurate with observations in other common complex diseases. One variant, not surrounded by other SNPs achieving low p-values and for which genotypes were only available in two of the 15 initial study groups, surpassed genome-wide significance (rs4957798, P=1.67×10-12) but was not subsequently replicated in the global meta-analysis across discovery and replication samples. The overall λGC was 1.03 (Figures S3 and S4).Seventy-six SNPs (of which 72 were independent) were prioritized for follow-up through in silico and de novo replication (Table S5). Nine SNPs showed association with P < 0.05 (minimum p-value was 0.003) in the replication dataset meta-analysis (binomial P=0.0135) (Table S5). Based on 72 independent SNPs taken forward, we would expect 0.05×72=3.6 SNPs to reach P=0.05 by chance. The 0.0135 P value reflects this enrichment in signal. No signals surpassed genome-wide significance (P=5×10-8) in the final global meta-analysis across all discovery and replication samples (Table S5) or in the AN subtype analyses (Tables S6-S7).

Of critical importance, we observed significant evidence of SNP effect sizes in the replication data in the same direction as the discovery set (55/72 signals, sign test binomial P=4×10-6). This enrichment was also observed for the AN restricting (58/72, P=8×10-8) and binge-purge (56/72, P=1×10-6) subtype analyses. These results strongly indicate that the prioritized set of variants is likely to contain true positive signals for AN but that the current sample size is insufficient to detect these effects.

Our analysis revealed two notable variants: rs9839776 (P=3.01×10-7) in SOX2OT (SOX2 overlapping transcript) and rs17030795 (P=5.84×10-6) in PPP3CA (protein phosphatase 3, catalytic subunit, alpha isozyme) (Table 2). Two additional signals emerged from the analysis focused on European replication samples only: rs1523921 (P=5.76×10-6) located between CUL3 (cullin 3) and FAM124B (family with sequence similarity 124B) and rs1886797 (P=8.05×10-6) located 18kb from SPATA13 (spermatogenesis associated 13) (Table S5). Four signals were in neurodevelopmental genes regulating synapse and neuronal network formation (SYN2, NCAM2, CNTNAP2 and CTNNA2; Table 2).

Table 2. Global meta-analysis results of SNPs with the greatest evidence of association for the main anorexia nervosa (AN) case-control analysis.

| SNP information | Global meta-analysis across discovery and replication datasets | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHR | POS | MARKER | NEAREST GENE | EA | NEA | EAF | OR | OR_95L | OR_95U | P | I2 | N_st | N_sa |

| 3 | 182794261 | rs9839776 | SOX2OT | T | C | 0.270 | 1.158 | 1.095 | 1.225 | 3.01E-07 | 0 | 27 | 21857 |

| 4 | 102267099 | rs17030795 | PPP3CA | G | A | 0.192 | 1.149 | 1.082 | 1.220 | 5.84E-06 | 0 | 24 | 23111 |

| 8 | 19584542 | rs11204064 | CSGALNACT1 | G | A | 0.477 | 1.118 | 1.063 | 1.176 | 1.57E-05 | 0.008 | 28 | 21477 |

| 3 | 12013264 | rs2618405 | 7.5kb from SYN2 | C | A | 0.218 | 1.152 | 1.079 | 1.229 | 2.03E-05 | 0.244 | 22 | 18566 |

| 13 | 23433988 | rs1886797 | 18kb from SPATA13 | T | C | 0.301 | 1.133 | 1.070 | 1.200 | 2.18E-05 | 0.317 | 25 | 15827 |

| 21 | 21257379 | rs10482915 | 35kb from NCAM2 | A | G | 0.074 | 1.193 | 1.097 | 1.297 | 3.96E-05 | 0 | 28 | 26164 |

| 7 | 106473684 | rs2395833 | PRKAR2B | T | G | 0.334 | 1.101 | 1.051 | 1.154 | 5.62E-05 | 0.132 | 29 | 26511 |

| 2 | 80768625 | rs1370339 | 39kb from CTNNA2 | C | T | 0.472 | 1.098 | 1.049 | 1.149 | 5.68E-05 | 0 | 29 | 26508 |

| 13 | 63470128 | rs9539891 | 255kb from OR7E156P | C | T | 0.332 | 0.891 | 0.842 | 0.942 | 5.88E-05 | 0 | 23 | 20389 |

| 2 | 225017222 | rs1523921 | 26kb from CUL3 / 42kb from FAM124B | T | C | 0.210 | 1.131 | 1.065 | 1.201 | 5.95E-05 | 0.162 | 26 | 21858 |

| 19 | 11650015 | rs206863 | ZNF833P | A | G | 0.899 | 0.864 | 0.804 | 0.928 | 6.47E-05 | 0.076 | 28 | 26402 |

| 23 | 107578961 | rs5929098 | COL4A5 | T | C | 0.771 | 1.135 | 1.066 | 1.210 | 8.37E-05 | 0.002 | 29 | 19249 |

| 7 | 146565029 | rs6943628 | CNTNAP2 | A | G | 0.097 | 1.161 | 1.077 | 1.251 | 9.38E-05 | 0 | 29 | 26377 |

CHR - chromosome; POS - position in hg18; EA - effect allele; NEA - non-effect allele; EAF - effect allele frequency; OR - odds ratio; OR_95L - lower 95% confidence interval; OR_95U - upper 95% confidence interval; P - p-value; I2 - measure of heterogeneity; N_st - number of contributing studies; N_sa - number of contributing samples.

AN subtype analyses

In the AN restricting subtype analyses, the two most significant signals were rs1523921 (as in the main analysis, P=8.39×10-5) and rs10777211 (P=8.95×10-5) located 333kb from ATP2B1 (ATPase, calcium transporting, plasma membrane 1), both detected in the European-only analysis (Table S6). The most significant result for AN binge-purge analysis was rs9839776 (as in the main analysis, P=3.97×10-4) in SOX2OT, also in Europeans only (Table S7). Overall, signals from the main AN case-control analysis display similar levels of association across both AN subtypes (Table S8).

Additional analyses

GCTA is technically challenging when synthesizing data across multiple strata with small individual sample sizes. When we applied it to our data we saw great variability in the estimates of variance and did not judge the results reliable. Results of the gene-based association test and network analysis are presented in their entirety in Supplemental Information and Figure S5, both of which were unremarkable.

Related traits

Nine out of the 11 previously reported variants suggestively associated with AN42 were found in our discovery meta-analysis, and six of these 9 SNPs had the same direction of effect as originally reported (P=0.508) (Table S9). Twelve out of 14 variants previously reported to be associated with eating disorder-related symptoms, behaviors, and personality traits59, 60 were found in our discovery meta-analysis and 7 had the same direction of effect (P=0.774) (Table S10), with one SNP (inside RUFY1) having P<0.05 (binomial P=0.459). We did not find evidence for signal enrichment in the 60 independent SNPs found in the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium data for ADHD, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder63-66 (Table S11).

When we compared 76 (53 independent) SNPs from the AN results with 89 established BMI/obesity SNPs,61, 62 five SNPs (inside NEGR1, PTBP2, TMEM18, FTO and MC4R) had P<0.05 (binomial P=0.1906). Twenty-six of these 53 SNPs had the same direction of effect as originally reported (binomial P value=1) (Table S12). Thirteen of 15 SNPs associated with extreme obesity were extracted from our dataset and 9 of these were independent. Four of these 9 SNPs had the same direction of effect as originally reported (binomial P value=1) (Table S13). Three SNPs (in TMEM18, FTO and MC4R) had P<0.05 (binomial P value=0.0084), indicating modest enrichment of nominally associated SNPs from extreme obesity in our discovery dataset.

Expression studies

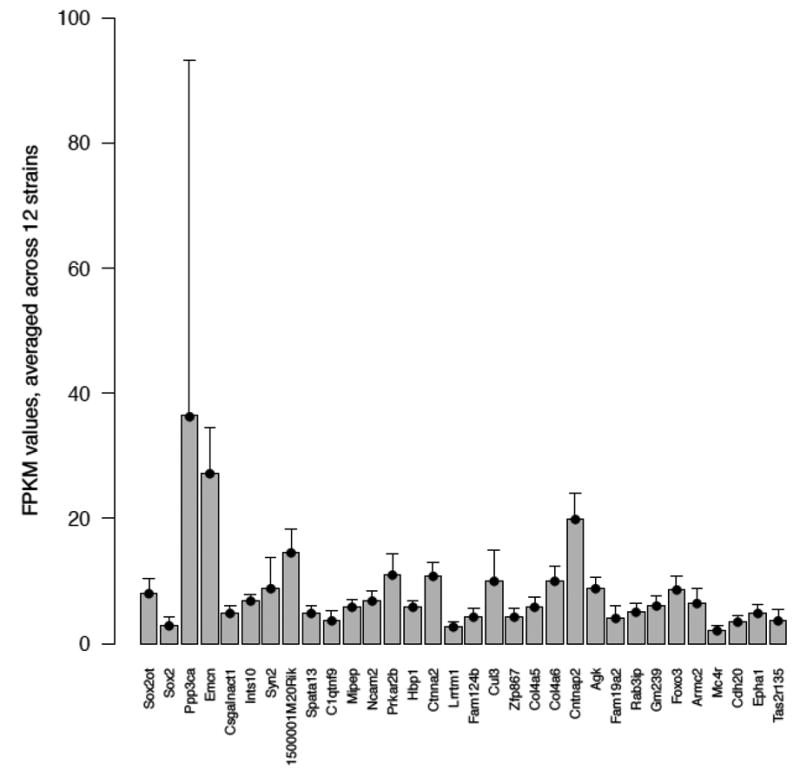

We analyzed RNAseq data for whole-brain tissue obtained from 12 different mouse strains(Figure 1). We performed this analysis for 32 mouse orthologues of the 34 human genes identified (Table S4). All 32 genes were expressed in the brain, above an average of 2 FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of exon per Million fragments mapped). Specifically, we find extremely high expression levels for Ppp3ca (FPKM value 36.40). Further, we find high expression for Sox2ot, with an FPKM value of 8.02, and similar expression values for Cul3 (10.01) and Ctnna2 (10.79).

Figure 1.

Analysis of RNAseq data for whole-brain tissue obtained from 12 different mouse strains for 32 mouse orthologues of the 34 human genes for which association to anorexia nervosa (AN) was identified. The average FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of exon per Million fragments mapped) values for 32 genes across 12 mouse strains are shown.

Discussion

Given that the evidence base for the treatment of AN remains weak and that no effective medications for its treatment exist,20, 67 advances in our understanding of the underlying biology of the disorder are essential in order to develop novel therapeutics and to reduce the loss of life and diminution of quality of life associated with the disorder. The GCAN/WTCCC3 investigation represents an unprecedented international genetic collaboration in the study of AN, which sets the foundation for further genetic studies.

Our final global meta-analysis had 80% power to detect SNPs with allele frequency of 0.35 and genotypic relative risk of 1.15 (α=5×10-8, additive model).68 The AN subtype meta-analysis had 80% power to detect SNPs with allele frequency of 0.35 and genotypic relative risk 1.27 for the AN restricting subtype and 1.28 for the AN binge-purge subtype. Given these limitations in power, our strongest indicator that larger sample sizes could detect genetic variants associated with AN was revealed in the sign tests. The strong and significant evidence for SNP effect sizes in the same direction between discovery and replication sets (P=4×10-6) clearly suggests that larger sample sizes could successfully identify variants associated with AN and with the AN subtypes potentially enabling differentiation on a genetic level between restricting and binge/purge subtypes.

Several genetic variants were suggestively associated with AN (P<10-5) (Table 2). Two variants, rs9839776 in SOX2OT and rs17030795 in PPP3CA, were identified through analysis of all discovery and replication datasets. Two additional variants with P<10-5, rs1523921 located between CUL3 and FAM124B and rs1886797 located near SPATA13, were identified through analysis of individuals of European descent only (Table S5), suggesting either heterogeneity in the effects of these SNPs by ancestry or low power. The genes displayed in Table 2 are discussed in greater detail in the Supplementary Information; however, we highlight that four of these variants are neurodevelopmental genes that regulate synapse and neuronal network formation (SYN2, NCAM2, CNTNAP2 and CTNNA2) and two have been associated with Alzheimer's disease (SOX2OT and PPP3CA). Additionally, one of our prioritized SNPs (rs6558000) (Table S5) is located in close vicinity (9kb upstream) of the EPHX2 gene that was recently identified as a susceptibility locus to AN through candidate gene sequencing study of early-onset severe AN cases and controls.43

Our expression studies further extend the GWAS findings. It is reasonable, althoughperhaps not essential, to expect that genes implicated in AN be expressed in the brain. Supporting this assumption, 32 mouse orthologues of 34 human genes identified as being of interest were expressed at least at a low level in mouse brain. Moreover, genes corresponding to the more strongly associated genetic variants tended to be more highly expressed. For example, high FPKM values for Ppp3ca, Cul3, and Sox2ot underscore that these genes may play a neuropsychiatric role.

AN subtype analyses were included to determine whether differences might exist between the classic restricting subtype of AN and the subtype marked by dysregulation characterized by binge eating and/or purging behavior. These analyses had lower power due to the smaller sample sizes. Only two SNPs, rs1523921 (also found to be suggestively associated in the main case-control analysis) and rs10777211 located 333kb upstream of ATP2B1, showed association at the 10-5 significance level (Table S6). Similarly, subsequent analyses pertaining to associated phenotypes (weight regulation: BMI/obesity loci,40, 61, 69, 70 and loci for extreme obesity;61, 71, 72 psychiatric comorbidities: ADHD, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder) or previous equivocal association findings for AN or eating disorders (AN variants,42 eating disorder related symptoms, behaviors, and personality traits variants59, 60) did not reveal significant findings. More adequately powered analyses that could allow us to detect variants that can distinguish between these two subtypes could be clinically meaningful in predicting clinical course and outcome and eventually in designing targeted therapeutics.

Our understanding of the fundamental genetic architectures of complex medical diseases and psychiatric disorders has expanded rapidly.73 It has also become manifestly clear that genomic searches for common variation via GWAS can successfully uncover biological pathways of etiological relevance. The major limitation to discovery is sample size.74 A recent GWAS for schizophrenia reported the identification of 22 genome-wide significant loci for schizophrenia (21,000 cases and 38,000 controls), and the results yielded multiple themes of clear biological and translational significance (e.g., calcium biology and miR-137 regulation).75 Moreover, given that cases and controls were derived from multiple sources and genotyped on multiple platforms, imputation was essential. Although effective, the preferred approach will always be to have samples genotyped on the same platform to maximize comparability and the capacity to identify genomic associations.

Although the underlying biology of AN remains incompletely understood, the relative homogeneity of the phenotype, replicated heritability estimates, and encouraging results of the sign tests presented herein strongly encourage continuing this path of discovery. Phenotypic refinement and the identification of biomarkers of illness (independent of biomarkers of starvation) could assist with identification of risk loci. We believe that the surest and fastest path to fundamental etiological knowledge about the biological basis of AN is via GWAS in larger samples.74 This path is notably safe given that it relies on off-the-shelf technology whose utility has been proven in empirical results for multiple biomedical and psychiatric disorders. This approach is cost-effective due to recent sharp decreases in genotyping pricing. Therefore, we believe that accrual of large genotyped AN case-control samples should be an immediate priority for the field.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment for Funding, Biomaterials, and Clinical Data

Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute The WTCCC3

This work was funded by a grant from the WTCCC3 WT088827/Z/09 entitled “A genomewide association study of anorexia nervosa.”

Data Analysis Group: Carl A. Anderson1, Jeffrey C. Barrett1, James A.B. Floyd1, Christopher S. Franklin1, Ralph McGinnis1, Nicole Soranzo1, Eleftheria Zeggini1.

UK Blood Services Controls: Jennifer Sambrook2, Jonathan Stephens2, Willem H. Ouwehand2.

1958 Birth Cohort Controls: Wendy L. McArdle3, Susan M. Ring3, David P. Strachan4.

Management Committee: Graeme Alexander5, Cynthia M. Bulik6, David A. Collier7, Peter J. Conlon8, Anna Dominiczak9, Audrey Duncanson10, Adrian Hill11, Cordelia Langford1, Graham Lord12, Alexander P. Maxwell13, Linda Morgan14, Leena Peltonen1, Richard N. Sandford15, Neil Sheerin12, Nicole Soranzo1, Fredrik O. Vannberg11, Jeffrey C. Barrett1 (chair).

DNA, Genotyping, and Informatics Group: Hannah Blackburn1, Wei-Min Chen16, Sarah Edkins1, Mathew Gillman1, Emma Gray1, Sarah E. Hunt1, Cordelia Langford1, Suna Onengut-Gumuscu16, Simon Potter1, Stephen S Rich16, Douglas Simpkin1, Pamela Whittaker1.

The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, Cambridge CB10 1SA, UK

Division of Transfusion Medicine, Department of Haematology, University of Cambridge, NHSBT Cambridge Centre, Long Road, Cambridge, CB2 0PT, UK

Department of Social Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 2BN, UK

St. George's University, Division of Community Health Sciences, London SW19 0RE, UK

Department of Hepatology, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge CB2 0QQ, UK

Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, London SE5 8AF

Department of Nephrology, Beaumont Hospital, Dublin, Ireland and Royal College of Surgeons Dublin, Ireland

BHF Glasgow Cardiovascular Research Centre, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8TA, UK

Gibbs Building, 215 Euston Road, London NW1 2BE, UK

Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 2JA, UK

MRC Centre for Transplantation, King's College London, London SE1 9RT, UK

Belfast City Hospital, Lisburn Road, Belfast BT9 7AB, UK

School of Molecular Medical Sciences, University of Nottingham, Nottingham NG7 2UH, UK

Academic Department of Medical Genetics, Cambridge University, Cambridge CB2 0QQ, UK

Center for Public Health Genomics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA

Additional Wellcome Trust Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the WellcomeTrust (098051).

Eleftheria Zeggini is supported by the Wellcome Trust (098051).

Vesna Boraska is supported by Unity Through Knowledge Fund CONNECTIVITY PROGRAM (“Gaining Experience” Grant 2A), The National Foundation for Science, Higher Education and Technological Development of the Republic of Croatia (BRAIN GAIN- Postdoc fellowship) and the Wellcome Trust (098051).

Christopher S Franklin is supported by the WTCCC3 project, which is supported by the Wellcome Trust (WT090355/A/09/Z, WT090355/B/09/Z).

James A B Floyd is supported by the WTCCC3 project, which is supported by the Wellcome Trust (WT090355/A/09/Z, WT090355/B/09/Z).

Lorraine Southam is supported by the Wellcome Trust (098051).

William N Rayner is supported by the Wellcome Trust (098051).

The Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 3 project is supported by the Wellcome Trust (WT090355/A/09/Z, WT090355/B/09/Z).

We acknowledge use of data from the British 1958 Birth Cohort and the UK National Blood Service.

We obtained High Density SNP Association Analysis of Melanoma: Case-Control and Outcomes Investigation dataset through dbGaP (dbGaP Study Accession: phs000187.v1.p1). Research support to collect data and develop an application to support this project was provided by 3P50CA093459, 5P50CA097007, 5R01ES011740, and 5R01CA133996.

Laura Huckins acknowledges Wellcome Trust (098051) and the MRC (MR/J500355/1) and Ximena Ibarra-Soria for advice on RNA-seq analysis.

Austria. Medical University of Vienna. The study was partly supported by the European Commission, Framework 5 research program, Integrated Project QLK1-CT-1999-00916 “Factors in Healthy Eating” given to the consortium lead by Prof. J. Treasure and Prof. D. Collier, London. We thank Gerald Nobis, Dr. Maria Haidvogl, and Dr. Julia Philipp for help with data collection and interview work.

Canada. Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Zeynep Yilmaz was supported by a CIHR Doctoral Research Award (Genetic Determinants of Low Body Weight in Anorexia Nervosa; funding reference: GSD-111968).The Toronto authors would like to thank Sajid Shaikh, Maria Tampakeras, and Natalie Freeman for DNA preparation and laboratory support.

Canada. The Ontario Mental Health Foundation (OMHF). The collection of the Toronto DNA samples was supported by a grant from the OMHF, awarded to Allan S. Kaplan and Robert D. Levitan (Polymorphism in Serotonin System Genes: Putative Role in Increased Eating Behaviour in Seasonal Affective Disorder and Bulimia Nervosa).

Czech Republic. Charles University. The study was supported by grants IGA MZ ČR NS/10045-4 and IGA NT 14094/3 from the Czech Ministry of Education and Health and PRVOUK P24/LF1/3 and P26/LF1/4 Charles University, Prague, and from the Marie Curie Research Training Network INTACT (MRTN-CT-2006-035988).

Finland. University of Helsinki. Academy of Finland Center of Excellence in Complex Disease Genetics (grant numbers: 213506, 129680), ENGAGE – European Network for Genetic and Genomic Epidemiology, FP7-HEALTH-F4-2007, grant agreement number 201413. Data collection in the Finnish Twin studies has been supported by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grants AA-12502, AA-00145, and AA-09203 to R J Rose and AA15416 and K02AA018755 to D M Dick), the Academy of Finland (grants 100499, 205585, 118555 and 141054, 265240, and 264146 to JK). AR and LK were supported by the Academy of Finland, grants 259764 and 28327, respectively.

France. Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), France. This French cohort was recruited with grants from EC Framework V ‘Factors in Healthy Eating’ (a consortium coordinated by Janet Treasure and David Collier, King's College London), and from INRA/INSERM (4M406D), and the participation of Audrey Versini's work was supported by grants from ‘Région Ile-de-France’. Cases were ascertained from Sainte-Anne Hospital (Paris) and Robert Debre Hospital (Paris).

Genetics of Anorexia Nervosa (GAN), National Institute of Mental Health. The data and collection of biomaterials for the GAN study have been supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants (MH066122, MH066117, MH066145, MH066296, MH066147, MH0662, MH066193, MH066287, MH066288, MH066146). The principal investigators and co-investigators of this study were: University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Walter Kaye, M.D., Bernie Devlin, Ph.D.; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC: Cynthia M Bulik, Ph.D.; Roseneck Hospital for Behavioral Medicine, Prien and Department of Psychiatry, University of Munich, Germany: Manfred M Fichter, M.D.; Kings College London, Institute of Psychiatry, London, UK: Janet Treasure, M.D.; Toronto General Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Allan Kaplan, M.D., D. Blake Woodside, M.D.; Laureate Psychiatric Hospital, Tulsa, OK: Craig L. Johnson, Ph. D.; Weill Cornell Medical College, White Plains, NY: Katherine Halmi, M.D.; Sheppard Pratt Health System, Towson, MD: Harry A. Brandt, M.D., Steve Crawford, M.D.; Neuropsychiatric Research Institute, Fargo, ND; James E. Mitchell, M.D.; University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA: Michael Strober, Ph.D.; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA: Wade Berrettini, M.D., Ph.D.; and University of Birmingham, England: Ian Jones, M.D. We are indebted to the participating families for their contribution of time and effort in support of this study. The authors also wish to thank the Price Foundation for sponsoring the earlier work of this collaboration and would like to thank the study managers and clinical interviewers for their efforts in participant screening and clinical assessments.

Germany. University of Duisburg-Essen. Sample collection was funded by grants from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; EDNET 01GV0602, 01GV0624, 01GV0623 and 01GV0905, NGFNplus: 01GS0820) and the IFORES program of the University of Duisburg-Essen. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Germany. Prof. Ehrlich's work is supported by DFG grant EH 367/5-1 and the SFB 940.

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Leeds (Yorkshire Centre for Eating Disorders). The authors acknowledge the support of the Medical Research Council and GlaxoSmithKline for providing financial support of this project. The support of the Carnegie Trust in the form of a travel award is also acknowledged. We also acknowledge the help and support of the Discovery and Pipeline Genetics, and Translational Medicine and Genetics departments at GSK for their contributions to this study. In particular we would like to acknowledge Mike Stubbins, Julia Perry, Sarah Bujac, David Campbell (at GSK currently or at the time when the study was performed), John Blundell (Leeds University), and Evleen Mann (Yorkshire Centre for Eating Disorders), for their fundamental contribution to the realization of this study.

Greece. Eating Disorders Unit, 1st Department of Psychiatry, Athens University, Medical School. Special thanks goes to Associate Professor Varsou E, Head of Eating Disorders Unit, and Professor Papadimitriou G, Chairman and Director of 1st Department of Psychiatry, Athens University, Medical School, for their advice and support.

Italy. Padua (BIOVEDA). BIOVEDA was funded thanks to a Grant of Veneto Region in 2009. Samples were collected at Padua, Verona, Treviso, Vicenza and Portogruaro hospitals.

Netherlands. Department of Neuroscience and Pharmacology, The Rudolf Magnus Institute of Neuroscience, University Medical Center, Utrecht and Rintveld, Center for Eating Disorders, Altrecht in Zeist. Marek K. Brandys was supported by funding from the Marie Curie Research Training Network INTACT (Individually tailored stepped care for women with eating disorders; reference number: MRTN-CT-2006-035988). Martien Kas was supported by a ZonMW VIDI-grant (91786327) from The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO).

Norway. The National Institute of Public Health Twin Panel (NIPHTP). The NIPHTP was supported in part by grants from The Norwegian Research Council, The Norwegian Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation, The Norwegian Council for Mental Health and The European Commission under the program ‘Quality of Life and Management of the Living Resources’ of 5th Framework Program (no. QLG2-CT-2002-01254).

Poland. Poznan University of Medical Sciences (PUMS). PUMS study was sponsored by KBN scientific grant no. PO5B 12823

Spain. Department of Psychiatry University Hospital of Bellvitge-IDIBELL, Barcelona. Financial support was received from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria -FIS (PI11/210) and AGAUR (2009SGR1554). CIBER Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y Nutrición (CIBERobn) is an initiative of ISCIII.

Sweden. Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm. The Swedish Twin Registry is supported by the Swedish Department of Higher Education. The STR was supported by grants from the Ministry for Higher Education, the Swedish Research Council (M-2005-1112 and 2009-2298), GenomEUtwin (EU/QLRT-2001-01254; QLG2-CT-2002-01254), NIH grant DK U01-066134, The Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (SSF; ICA08-0047), the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation, the Royal Swedish Academy of Science, and ENGAGE (within the European Union Seventh Framework Programme, HEALTH-F4-2007-201413).

United Kingdom. King's College London. Financial support was received from the European Union (Framework-V Multicentre Research Grant, QLK1–1999-916), a Multicentre EU Marie Curie Research Training Network grant, INTACT (MRTN-CT-2006-035988) and a Marie-Curie Intra-European Fellowship (FP-7-People-2009-IEF, No. 254774). Dr. Oliver Davis is supported by a Sir Henry Wellcome Fellowship from the Wellcome Trust (WT088984). Cathryn Lewis is partly supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London.

United States. McLean Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA. The collection of DNA from participants at the McLean Hospital/Harvard Medical School site was supported in part by an investigator-initiated grant from Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs (principal investigator: Dr. Hudson).

United States. University of North Carolina. Sample collection was funded by a grant from the Foundation of Hope, Raleigh, North Carolina. Sara Trace, PhD, Jin Szatkiewicz, PhD, and Jessica Baker, PhD were funded by T32 MH076694 (PI:Bulik). Sara Trace was funded by a 2012–2015 Hilda and Preston Davis Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship Program in Eating Disorders Research Award. Stephanie Zerwas, PhD was funded by a UNC BIRWCH award K12HD001441. The Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program at UNC-Chapel Hill provided additional assistance UL1TR000083.

United States. Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville TN, and the Kartini Clinic for Disordered Eating, Portland, OR. Cases were ascertained from the Kartini Clinic, Portland Oregon. Sample collection and processing was funded by a Bristol-Myers Squibb Freedom to Discover Unrestricted Metabolic Diseases Research Grant to RDC.

Replication Samples

Children's Hospital of Philadelphia/Price Foundation. We gratefully thank all the patients and their families who were enrolled in this study, as well as all the control subjects who donated blood samples to Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) for genetic research purposes. We thank the Price Foundation for their support of the Collaborative Group effort that was responsible for recruitment of patients, collection of clinical information and provision of the DNA samples used in this study. The authors also thank the Klarman Family Foundation for supporting the study. We thank the technical staff at the Center for Applied Genomics at CHOP for producing the genotypes used for analyses and the nursing, medical assistant and medical staff for their invaluable help with sample recruitments. CTB and NJS are funded in part by the Scripps Translational Sciences Institute Clinical Translational Science Award [Grant Number U54 RR0252204-01]. All genome-wide genotyping was funded by an Institute Development Award to the Center for Applied Genomics from the CHOP. 2011 - 2014 Davis Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship Program in Eating Disorders Research Award, Yiran Guo, PhD; 2012 - 2015 Davis Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship Program in Eating Disorders Research Award, Dong Li, PhD.

Estonia. Estonian Genome Center of the University of Tartu (EGCUT). EGCUT received targeted financing from Estonian Government SF0180142s08, Center of Excellence in Genomics (EXCEGEN) and University of Tartu (SP1GVARENG). We acknowledge EGCUT technical personnel, especially Mr. V. Soo and S. Smit. Data analyzes were carried out in part in the High Performance Computing Center of University of Tartu.

Japan. National Institute of Mental Health, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry. The data and sample collection have been supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research 20390201 and 23390201 to G. Komaki from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan. We are indebted to the members of the Japanese Genetic Research Group For Eating Disorders for their contribution of time and effort in collecting samples and clinical data.

The Price Foundation Collaborative Group. Harry Brandt, Steve Crawford, Scott Crow, Manfred M. Fichter, Katherine A. Halmi, Craig Johnson, Allan S. Kaplan, Maria La Via, James Mitchell, Michael Strober, Alessandro Rotondo, Janet Treasure, D. Blake Woodside, Cynthia M. Bulik, Pamela Keel, Kelly L. Klump, Lisa Lilenfeld, Laura M. Thornton, Kathy Plotnicov, Andrew W. Bergen, Wade Berrettini, Walter Kaye, and Pierre Magistretti.

Acknowledgements for Controls

Austria. Controls in Vienna were collected with support to Harald Aschauer by Österreichische Nationalbank (ÖNB Project Nr. 5777 and 13198), Austrian Science Fund (Pr. Nr. P7639), European Science Foundation (ESF Programme MNMI) and European Commission (Biomed 1, J1182E25A).

Canada. NIH grant No. - U24 CA074783 to S. Gallinger. This work was made possible through collaboration and cooperative agreements with the Colon Cancer Family Registry and PIs. The content of this manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Cancer Institute or any of the collaborating institutions or investigators in the Colon CFR, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government or the Colon CFR.

Czech Republic. Support came from the European Regional Development Fund and the State Budget of the Czech Republic (RECAMO, CZ.1.05/2.1.00/03.0101).

dbGAP DAC. Research support to collect data and develop an application to support this project was provided by 3P50CA093459, 5P50CA097007, 5R01ES011740, and 5R01CA133996.

Germany. We thank all probands from the community-based cohorts of PopGen, KORA, and the Heinz Nixdorf Recall (HNR) study. This study was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), within the context of the National Genome Research Network plus (NGFNplus), and the MooDS-Net (grant 01GS08144 to S.C.). The KORA research platform was initiated and financed by the Helmholtz Center Munich, German Research Center for Environmental Health, which is funded by the BMBF and by the State of Bavaria. The Heinz Nixdorf Recall cohort was established with the support of the Heinz Nixdorf Foundation.

Greece. This research has been co-financed by the European Union (European Social Fund – ESF) and Greek national funds through the Operational Program “Education and Lifelong Learning” of the National Strategic Reference Framework (NSRF) - Research Funding Program: Heracleitus II. Investing in knowledge society through the European Social Fund.

Italy (North), Verona. The INCIPE study was co-sponsored by Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Verona, Azienda Ospedaliera di Verona, and University of Verona. Samples were collected in Verona, Padua, Monselice and Dolo. Co-principal investigators were Antonio Lupo and Giovanni Gambaro.

Netherlands. Genotyping of controls was funded by NIH/NIMH R01 MH078075, granted to Roel Ophoff.

Spain. Spanish Plan Nacional SAF2008-00357 (NOVADIS); the Generalitat de Catalunya AGAUR 2009 SGR-1502; the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FIS/FEDER PI11/00733); and the European Commission 7th Framework Program, Project N. 261123 (GEUVADIS), and Project N. 262055 (ESGI).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Patrick F. Sullivan was on the SAB of Expression Analysis (Durham, NC).

Cynthia Bulik was a consultant for Shire Pharmaceuticals at the time the manuscript was written.

Federica Tozzi was full time employee of GSK at the time when the study was performed.

David A. Collier was employed by Eli Lilly UK for a portion of the time that this study was performed.

James L. Kennedy has received honoraria from Eli Lilly and Roche.

Robert D. Levitan has received honorarium from Astra-Zeneca.

Supplementary information is available at Molecular Psychiatry's website.

References

- 1.Klump KL, Bulik CM, Kaye WH, Treasure J, Tyson E. Academy for Eating Disorders position paper: eating disorders are serious mental illnesses. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:97–103. doi: 10.1002/eat.20589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoek H, van Hoeken D. Review of the prevalence and incidence of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34:383–396. doi: 10.1002/eat.10222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition Text Revision. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucas AR, Beard CM, O'Fallon WM, Kurland LT. 50-year trends in the incidence of anorexia nervosa in Rochester, Minn.: a population-based study. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:917–922. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.7.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholls DE, Lynn R, Viner RM. Childhood eating disorders: British National Surveillance Study. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198:295–301. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.081356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bueno B, Krug I, Bulik C, Jiménez-Murcia S, Granero R, Thornton L, Penelo E, Menchón J, Sánchez I, Tinahones F, Fernández-Aranda F. Late onset eating disorders in Spain: Clinical characteristics and therapeutic implications. J Clin Psychol. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22006. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katzman D. Medical complications in adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:S52–59. doi: 10.1002/eat.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharp C, Freeman C. The medical complications of anorexia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:452–462. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.4.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaye W, Bulik C, Thornton L, Barbarich BS, Masters K Group PFC. Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2215–2221. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Godart N, Flament M, Perdereau F, Jeammet P. Comorbidity between eating disorders and anxiety disorders: A review. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32:253–270. doi: 10.1002/eat.10096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez-Aranda F, Pinheiro AP, Tozzi F, Thornton LM, Fichter MM, Halmi KA, Kaplan AS, Klump KL, Strober M, Woodside DB, Crow S, Mitchell J, Rotondo A, Keel P, Plotnicov KH, Berrettini WH, Kaye WH, Crawford SF, Johnson C, Brandt H, La Via M, Bulik CM. Symptom profile of major depressive disorder in women with eating disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41:24–31. doi: 10.1080/00048670601057718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Outcomes of eating disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:293–309. doi: 10.1002/eat.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathers CD, Vos ET, Stevenson CE, Begg SJ. The Australian Burden of Disease Study: measuring the loss of health from diseases, injuries and risk factors. Med J Aust. 2000;172:592–596. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb124125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sullivan PF. Mortality in anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1073–1074. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, Nielsen S. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:724–731. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birmingham C, Su J, Hlynsky J, Goldner E, Gao M. The mortality rate from anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38:143–146. doi: 10.1002/eat.20164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millar HR, Wardell F, Vyvyan JP, Naji SA, Prescott GJ, Eagles JM. Anorexia nervosa mortality in Northeast Scotland, 1965-1999. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:753–757. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zipfel S, Lowe B, Reas DL, Deter HC, Herzog W. Long-term prognosis in anorexia nervosa: lessons from a 21-year follow- up study. Lancet. 2000;355:721–722. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bulik CM, Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Sedway JA, Lohr KN. Anorexia nervosa treatment: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:310–320. doi: 10.1002/eat.20367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eating disorders: Core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders. [Accessed November 15, 2013];2004 http://www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o=101239. [PubMed]

- 22.McKenzie JM, Joyce PR. Hospitalization for anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 1992;11:235–241. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krauth C, Buser K, Vogel H. How high are the costs of eating disorders - anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa - for German society? Eur J Health Econ. 2002;3:244–250. doi: 10.1007/s10198-002-0137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Striegel-Moore RH, Bulik CM. Risk factors for eating disorders. Am Psychol. 2007;62:181–198. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kas M, Kaye W, Mathes W, Bulik C. Interspecies genetics of eating disorders traits. Am J Med Genets Part B; Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B:318–327. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strober M, Freeman R, Lampert C, Diamond J, Kaye W. Controlled family study of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: evidence of shared liability and transmission of partial syndromes. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:393–401. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lilenfeld L, Kaye W, Greeno C, Merikangas K, Plotnikov K, Pollice C, Rao R, Strober M, Bulik C, Nagy L. A controlled family study of restricting anorexia and bulimia nervosa: comorbidity in probands and disorders in first-degree relatives. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:603–610. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bulik C, Sullivan P, Tozzi F, Furberg H, Lichtenstein P, Pedersen N. Prevalence, heritability and prospective risk factors for anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:305–312. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klump KL, Miller KB, Keel PK, McGue M, Iacono WG. Genetic and environmental influences on anorexia nervosa syndromes in a population-based twin sample. Psychol Med. 2001;31:737–740. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wade TD, Bulik CM, Neale M, Kendler KS. Anorexia nervosa and major depression: shared genetic and environmental risk factors. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:469–471. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kortegaard LS, Hoerder K, Joergensen J, Gillberg C, Kyvik KO. A preliminary population-based twin study of self-reported eating disorder. Psychol Med. 2001;31:361–365. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bulik CM, Thornton LM, Root TL, Pisetsky EM, Lichtenstein P, Pedersen NL. Understanding the relation between anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in a Swedish national twin sample. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grice DE, Halmi KA, Fichter MM, Strober M, Woodside DB, Treasure JT, Kaplan AS, Magistretti PJ, Goldman D, Bulik CM, Kaye WH, Berrettini WH. Evidence for a susceptibility gene for anorexia nervosa on chromosome 1. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:787–792. doi: 10.1086/339250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Devlin B, Bacanu S, Klump K, Bulik C, Fichter M, Halmi K, Kaplan A, Strober M, Treasure J, Woodside DB, Berrettini WH, Kaye WH. Linkage analysis of anorexia nervosa incorporating behavioral covariates. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:689–696. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.6.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bacanu S, Bulik C, Klump K, Fichter M, Halmi K, Keel P, Kaplan A, Mitchell J, Rotondo A, Strober M, Treasure J, Woodside D, Bergen A, Berrettini W, Kaye W, Devlin B. Linkage analysis of anorexia and bulimia nervosa cohorts using selected behavioral phenotypes as quantitative traits or covariates. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;139:61–68. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slof-Op't Landt M, van Furth E, Meulenbelt I, Slagboom P, Bartels M, Boomsma D, Bulik C. Eating disorders: From twin studies to candidate genes and beyond. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2005;16:467–482. doi: 10.1375/183242705774310114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bulik CM, Slof-Op't Landt MC, van Furth EF, Sullivan PF. The genetics of anorexia nervosa. Ann Rev Nutr. 2007;27:263–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hinney A, Scherag S, Hebebrand J. Genetic findings in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2010;94:241–270. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-375003-7.00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hebebrand J, Remschmidt H. Anorexia nervosa viewed as an extreme weight condition: genetic implications. Hum Genet. 1995;95:1–11. doi: 10.1007/BF00225065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muller TD, Greene BH, Bellodi L, Cavallini MC, Cellini E, Di Bella D, Ehrlich S, Erzegovesi S, Estivill X, Fernandez-Aranda F, Fichter M, Fleischhaker C, Scherag S, Gratacos M, Grallert H, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Herzog W, Illig T, Lehmkuhl U, Nacmias B, Ribases M, Ricca V, Schafer H, Scherag A, Sorbi S, Wichmann HE, Hebebrand J, Hinney A. Fat mass and obesity-associated gene (FTO) in eating disorders: evidence for association of the rs9939609 obesity risk allele with bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. Obes Facts. 2012;5:408–419. doi: 10.1159/000340057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakabayashi K, Komaki G, Tajima A, Ando T, Ishikawa M, Nomoto J, Hata K, Oka A, Inoko H, Sasazuki T, Shirasawa S. Identification of novel candidate loci for anorexia nervosa at 1q41 and 11q22 in Japanese by a genome-wide association analysis with microsatellite markers. J Hum Genet. 2009;54:531–537. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang K, Zhang H, Bloss CS, Duvvuri V, Kaye W, Schork NJ, Berrettini W, Hakonarson H. A genome-wide association study on common SNPs and rare CNVs in anorexia nervosa. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:949–959. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scott-Van Zeeland AA, Bloss CS, Tewhey R, Bansal V, Torkamani A, Libiger O, Duvvuri V, Wineinger N, Galvez L, Darst BF, Smith EN, Carson A, Pham P, Phillips T, Villarasa N, Tisch R, Zhang G, Levy S, Murray S, Chen W, Srinivasan S, Berenson G, Brandt H, Crawford S, Crow S, Fichter MM, Halmi KA, Johnson C, Kaplan AS, La Via M, et al. Evidence for the role of EPHX2 gene variants in anorexia nervosa. Mol Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gendall K, Joyce P, Carter F, McIntosh V, Jordan J, Bulik C. The psychobiology and diagnostic significance of amenorrhea in patients with anorexia nervosa. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1531–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pinheiro A, Thornton L, Plotonicov K, Tozzi T, Klump K, Berrettini W, Brandt H, Crawford S, Crow S, Fichter M, Goldman D, Halmi K, Johnson C, Kaplan A, Keel P, LaVia M, Mitchell J, Rotondo A, Strober M, Treasure J, Woodside D, Kaye W, Bulik C. Patterns of menstrual disturbance in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:424–434. doi: 10.1002/eat.20388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tozzi F, Thornton L, Klump K, Bulik C, Fichter M, Halmi K, Kaplan A, Strober M, Woodside D, Crow S, Mitchell J, Rotondo A, Mauri M, Cassano C, Keel P, Plotnicov K, Pollice C, Lilenfeld L, Berrettini W, Kaye W. Symptom fluctuation in eating disorders: correlates of diagnostic crossover. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:732–740. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, Dermitzakis E, Schaffner SF, Yu F, Bonnen PE, de Bakker PI, Deloukas P, Gabriel SB, Gwilliam R, Hunt S, Inouye M, Jia X, Palotie A, Parkin M, Whittaker P, Chang K, Hawes A, Lewis LR, Ren Y, Wheeler D, Muzny DM, Barnes C, Darvishi K, Hurles M, Korn JM, Kristiansson K, Lee C, McCarrol SA, et al. Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature. 2010;467:52–58. doi: 10.1038/nature09298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marchini J, Howie B. Genotype imputation for genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nrg2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Magi R, Morris AP. GWAMA: software for genome-wide association meta-analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:288. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morris JA, Randall JC, Maller JB, Barrett JC. Evoker: a visualization tool for genotype intensity data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1786–1787. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huckins L, Boraska V, Franklin C, Floyd J, Southam L, Nervosa GCfA, 3 WTCCC. Sullivan P, Bulik C, Collier D, Tyler-Smith C, Zeggini E, Tachmazidou I. Using ancestry-informative markers to identify fine structure across 15 populations of European origin. Eur J Hum Genet. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.1. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang K, Zhang H, Bloss CS, Duvvuri V, Kaye W, Schork NJ, Berrettini W, Hakonarson H Price Foundation Collaborative Group. A genome-wide association study on common SNPs and rare CNVs in anorexia nervosa. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:949–959. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aulchenko YS, Ripke S, Isaacs A, van Duijn CM. GenABEL: an R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1294–1296. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou X, Stephens M. Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nat Genet. 2012;44:821–824. doi: 10.1038/ng.2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gauderman WJ. Candidate gene association analysis for a quantitative trait, using parent-offspring trios. Genet Epidemiol. 2003;25:327–338. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2008 http://www.R-project.org.

- 58.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boraska V, Davis OS, Cherkas LF, Helder SG, Harris J, Krug I, Liao TP, Treasure J, Ntalla I, Karhunen L, Keski-Rahkonen A, Christakopoulou D, Raevuori A, Shin SY, Dedoussis GV, Kaprio J, Soranzo N, Spector TD, Collier DA, Zeggini E. Genome-wide association analysis of eating disorder-related symptoms, behaviors, and personality traits. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2012;159B:803–811. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wade T, Gordon S, Medland, Bulik CM, Heath A, Montgomery GW, Martin NG. Genetic variants associated with disordered eating. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:594–608. doi: 10.1002/eat.22133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fall T, Ingelsson E. Genome-wide association studies of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guo Y, Lanktree MB, Taylor KC, Hakonarson H, Lange LA, Keating BJ. Gene-centric meta-analyses of 108 912 individuals confirm known body mass index loci and reveal three novel signals. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:184–201. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neale BM, Medland SE, Ripke S, Asherson P, Franke B, Lesch KP, Faraone SV, Nguyen TT, Schafer H, Holmans P, Daly M, Steinhausen HC, Freitag C, Reif A, Renner TJ, Romanos M, Romanos J, Walitza S, Warnke A, Meyer J, Palmason H, Buitelaar J, Vasquez AA, Lambregts-Rommelse N, Gill M, Anney RJ, Langely K, O'Donovan M, Williams N, Owen M, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:884–897. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sklar P, Ripke S, Scott LJ, Andreassen OA, Cichon S, Craddock N, Edenberg HJ, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Rietschel M, Blackwood D, Corvin A, Flickinger M, Guan W, Mattingsdal M, McQuillin A, Kwan P, Wienker TF, Daly M, Dudbridge F, Holmans PA, Lin D, Burmeister M, Greenwood TA, Hamshere ML, Muglia P, Smith EN, Zandi PP, Nievergelt CM, McKinney R, Shilling PD, et al. Large-scale genome-wide association analysis of bipolar disorder identifies a new susceptibility locus near ODZ4. Nat Genet. 2011;43:977–983. doi: 10.1038/ng.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Genome-wide association study identifies five new schizophrenia loci. Nat Genet. 2011;43:969–976. doi: 10.1038/ng.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:497–511. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Watson HJ, Bulik CM. Update on the treatment of anorexia nervosa: review of clinical trials, practice guidelines and emerging interventions. Psychol Med. 2012:1–24. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gauderman WJ. Sample size requirements for association studies of gene-gene interaction. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:478–484. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.5.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Speliotes EK, Willer CJ, Berndt SI, Monda KL, Thorleifsson G, Jackson AU, Lango Allen H, Lindgren CM, Luan J, Magi R, Randall JC, Vedantam S, Winkler TW, Qi L, Workalemahu T, Heid IM, Steinthorsdottir V, Stringham HM, Weedon MN, Wheeler E, Wood AR, Ferreira T, Weyant RJ, Segre AV, Estrada K, Liang L, Nemesh J, Park JH, Gustafsson S, Kilpelainen TO, et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat Genet. 2010;42:937–948. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hinney A, Hebebrand J. Three at one swoop! Obes Facts. 2009;2:3–8. doi: 10.1159/000200020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bradfield JP, Taal HR, Timpson NJ, Scherag A, Lecoeur C, Warrington NM, Hypponen E, Holst C, Valcarcel B, Thiering E, Salem RM, Schumacher FR, Cousminer DL, Sleiman PM, Zhao J, Berkowitz RI, Vimaleswaran KS, Jarick I, Pennell CE, Evans DM, St Pourcain B, Berry DJ, Mook-Kanamori DO, Hofman A, Rivadeneira F, Uitterlinden AG, van Duijn CM, van der Valk RJ, de Jongste JC, Postma DS, et al. A genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies new childhood obesity loci. Nat Genet. 2012;44:526–531. doi: 10.1038/ng.2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scherag A, Dina C, Hinney A, Vatin V, Scherag S, Vogel CI, Muller TD, Grallert H, Wichmann HE, Balkau B, Heude B, Jarvelin MR, Hartikainen AL, Levy-Marchal C, Weill J, Delplanque J, Korner A, Kiess W, Kovacs P, Rayner NW, Prokopenko I, McCarthy MI, Schafer H, Jarick I, Boeing H, Fisher E, Reinehr T, Heinrich J, Rzehak P, Berdel D, et al. Two new loci for body-weight regulation identified in a joint analysis of genome-wide association studies for early-onset extreme obesity in French and German study groups. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Visscher PM, Brown MA, McCarthy MI, Yang J. Five years of GWAS discovery. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:7–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sullivan PF, Daly MJ, O'Donovan M. Genetic architectures of psychiatric disorders: the emerging picture and its implications. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:537–551. doi: 10.1038/nrg3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ripke S, O'Dushlaine C, Chambert K, Moran J, Kähler A, Akterin S, Bergen S, Collins A, Crowley J, Fromer M, Kim Y, Lee S, Magnusson P, Sanchez N, Stahl E, Williams S, Wray N, Xia K, Bettella F, Børglum A, Cormican P, Craddock N, de Leeuw C, Durmishi N, Gill M, Golimbet V, Hamshere ML, Holmans P, Hougaard D, Kendler K, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 13 new risk loci for schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1150–1159. doi: 10.1038/ng.2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.