Abstract

Objectives

Unilateral haemodynamically significant large-vessel intracranial stenosis may be associated with reduced blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR), an indicator of autoregulatory reserve. Reduced CVR has been associated with ipsilateral cortical thinning and loss in cognitive function. These effects have been shown to be reversible following revascularisation. Our aim was to study the effects of unilateral revascularisation on CVR in the non-intervened hemisphere in bilateral steno-occlusive or Moyamoya disease.

Study Design

A retrospective observational study.

Setting

A routine follow-up assessment of CVR after a revascularisation procedure at a research teaching hospital in Toronto (Journal wants us to generalise).

Participants

Thirteen patients with bilateral Moyamoya disease (age range 18 to 52 years; 3 males), seven patients with steno-occlusive disease (age range 18 to 78 years; six males) and 27 approximately age-matched normal control subjects (age range 19–71 years; 16 males) with no history or findings suggestive of any neurological or systemic disease.

Intervention

Participants underwent BOLD CVR MRI using computerised prospective targeting of CO2, before and after unilateral revascularisation (extracranial–intracranial bypass, carotid endarterectomy or encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis). Pre-revascularisation and post-revascularisation CVR was assessed in each major arterial vascular territory of both hemispheres.

Results

As expected, surgical revascularisation improved grey matter CVR in the middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory of the intervened hemisphere (0.010±0.023 to 0.143±0.010%BOLD/mm Hg, p<0.01). There was also a significant post-revascularisation improvement in grey matter CVR in the MCA territory of the non-intervened hemisphere (0.101±0.025 to 0.165±0.015%BOLD/mm Hg, p<0.01).

Conclusions

Not only does CVR improve in the hemisphere ipsilateral to a flow restoration procedure, but it also improves in the non-intervened hemisphere. This highlights the potential of CVR mapping for staging and evaluating surgical interventions.

Keywords: NEUROPHYSIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study demonstrates how cerebrovascular reactivity mapping can provide important information concerning the efficacy of revascularisation.

Longitudinal design and a well-defined study population although heterogeneous (steno-occlusive disease and Moyamoya disease).

It is difficult to draw substantial conclusions from the patients who underwent encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis and carotid endarterectomy procedures due to the small cohort.

Future research on the association between post-revascularisation neuropsychological/cognitive performance and haemodynamic outcome is needed.

Introduction

Steno-occlusive cerebrovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis and Moyamoya disease (MMD), can result in impaired regional cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR).1 2 CVR, a measure of vascular autoregulation, is defined as the change in blood flow per unit change in a vasoactive stimulus. Cerebral autoregulation refers to the capacity of cerebrovascular beds to maintain constant perfusion despite changes in cerebral perfusion pressure and may also be defined in terms of changes in vascular resistance or arteriolar calibre in response to fluctuations in perfusion pressure.3

MMD is a progressive steno-occlusive process involving the supraclinoid segment of the internal carotid arteries (ICA) followed by development of fine local collateral vessels. Individuals with MMD commonly present with transient ischaemic attack or stroke due to impaired vascular reserve.4 Similarly, exhaustion of autoregulation occurs in the vascular beds downstream of severe large artery steno-occlusive disease due to the lowering of perfusion pressure distal to the stenosis/occlusion. These vascular beds consume vasodilatory reserve in order to maintain normal levels of perfusion at baseline. However, the ability to vasodilate in response to a vasoactive challenge is finite. When the ability to vasodilate is exhausted, the vascular bed can no longer lower resistance and can no longer compete for flow with other beds that retain this ability. Under a global vasodilatory stimulus, blood flow will be diverted away from beds that cannot lower resistance to those beds that can. This redistribution of perfusion is called the steal phenomenon.5 The presence of steal in steno-occlusive disease and MMD indicates a high risk of stroke.6 7 Steal physiology secondary to stenosis/occlusion in MMD has also been associated with ipsilateral cortical thinning2 and loss in cognitive function.8

Numerous surgical revascularisation techniques have been established for individuals with steno-occlusive and MMD to circumvent haemodynamic impairment. These surgical techniques range from direct revascularisation procedures such as superficial temporal artery (STA)–middle cerebral artery (MCA) bypass and carotid endarterectomy (CEA) to indirect procedures such as encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis (EDAS).9 If normalisation of CVR occurs following successful revascularisation, ipsilateral cognitive deficits and cortical thinning may also improve.10 However, the impact of surgical revascularisation on the contralateral hemisphere using blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) CVR has not been previously investigated.

Collateral circulation plays an important role in the pathophysiology of stroke and transient ischaemic attacks.11–13 Cerebral collateral circulation refers to the auxillary vascular network that stabilises cerebral blood flow (CBF) when primary conduits fail.12 Other supporting conduits with flow reversal include the ipsilateral ophthalmic and ipsilateral posterior communicating arteries (PCoAs).14 15 In addition, pathological recruitment of potential anastomotic intrahemispheric connections through leptomeningeal collaterals are frequently observed in patients with stenosis/occlusion.12 It is known that CVR is reduced ipsilateral to steno-occlusive disease,16 however, current knowledge of collateral circulation post-revascularisation and its effects on vascular reactivity in the non-intervened hemisphere remains limited. In cases of severe bilateral haemodynamic impairment, there is room for the autoregulatory reserve to improve. We hypothesise that unilateral revascularisation may improve CVR in the non-intervened hemisphere if the presurgical haemodynamic status is impaired.

The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of unilateral revascularisation on cortical BOLD CVR in the contralateral hemisphere in the presence of bilateral steno-occlusive or MMD. We identified 13 patients with MMD and seven patients with steno-occlusive disease (but with normal-appearing brain tissue on structural MRI pre-revascularisation and post-revascularisation). We assessed cortical CVR before and after surgical revascularisation in the intervened and non-intervened hemisphere.

Subjects and methods

Subject recruitment and assessment

Subjects were participants in ongoing studies of CVR in cerebrovascular disease. All studies were approved by the research ethics board (REB) at the University Health Network and all subjects provided informed consent. Following REB approval, images from 737 patients who were referred from neurosurgery or stroke prevention clinics and enrolled in one of the CVR studies at the Toronto Western Hospital between June 2005 and April 2013 were screened by an experienced neuroradiologist (DJM) using the following inclusion criteria: (1) angiographically confirmed diagnosis of bilateral ICA or MCA disease, greater than 70% stenosis or occlusion; (2) a pre-revascularisation CVR map showing impaired reactivity within one cerebral hemisphere (figure 1); (3) a surgical revascularisation procedure consisting of either extracranial–intracranial (EC–IC) bypass, CEA, or EDAS; (4) no evidence of cortical or subcortical infarcts greater than 2 cm, or intracranial haemorrhage, on pre-revascularisation and post-revascularisation MRI and (5) no evidence of significant vertebral or basilar stenosis greater than 70%. Patients with motion artefacts on BOLD images were excluded from the analysis. Thirteen patients with bilateral MMD (age range 18–52 years; 3 males) and seven patients with steno-occlusive disease (age range 18–78 years; 6 males) met the inclusion criteria (online supplementary table S1). Our database also included CVR studies in 27 approximately age-matched normal control subjects (age range 19–71 years; 16 males) with no history or findings suggestive of any neurological or systemic disease. These were non-smokers not on vasoactive medications.

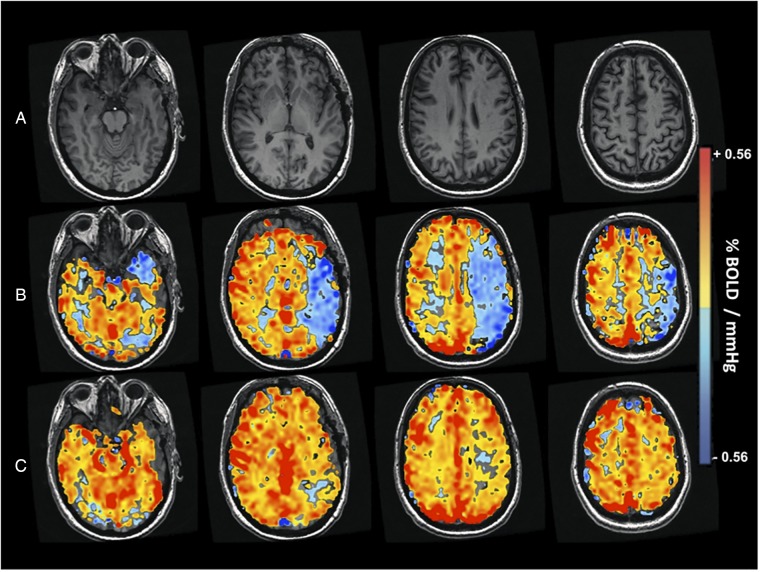

Figure 1.

CVR imaging study of patient with bilateral Moyamoya disease and impaired CVR (patient 14). BOLD, blood-oxygen-level-dependent; CVR, cerebrovascular reactivity.

MRI data acquisition

For all scans, MRI was performed on a 3.0T scanner (Signa HDX platform, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) with an 8-channel phased array head coil. T1-weighted anatomical images of the entire brain were acquired using a three-dimensional spoiled gradient echo pulse sequence (1.0 mm thick, matrix 256×256, field of view 22×22 cm). BOLD MR CVR data was acquired for the entire brain using a T2*-weighted echoplanar gradient-echo sequence (TR 2000 ms, TE 30 ms, flip 85°, slice thickness 5.0 mm, no gap, field of view 24×24 cm, matrix 64×64, 255 temporal frames) during manipulation of arterial CO2.

Vasodilatory stimulus (gas, end-tidal pCO2 and pO2 manipulation)

Precise carbon dioxide manipulation was applied by prospective end-tidal gas targeting using an automated gas blender. This device adjusts the gas composition and flow to a sequential gas delivery mask and breathing circuit (RespirAct, Thornhill Research Inc., Toronto, Canada) according to the methods described previously by Slessarev et al.17 18 This system enables independent control of PETCO2 and end-tidal partial pressure of oxygen (PETO2) in cooperative patients unaffected by breathing pattern and minute ventilation. The respiratory protocol used in this study consisted of PETCO2 40 mm Hg baseline for 60 s, a hypercapnic step change to a PETCO2 of 50 mm Hg for 90 s, a return to baseline for 90 s, and a second hypercapnic step for 120 s with a final return to baseline. All steps were implemented while maintaining normoxia (PETO2 ∼110 mm Hg). Previous work describes the PETCO2 and PETO2 sequences used during the analysis of BOLD MRI CVR in more detail.19 20

Image reconstruction

The acquired BOLD MRI and PETCO2 data were imported to AFNI21 software for analysis. BOLD images were slice time-corrected, volume-registered, and aligned to axial anatomical T1-weighted images. The CVR maps were then constructed by time-shifting the acquired PETCO2 data to the point of maximum correlation with the whole brain average BOLD signal using MATLAB software. This compensates for the temporal delay from pulmonary to cerebral circulation. To minimise the effect of head motion from the BOLD time series, the motion covariates were estimated by the volume registration and subsequently included in our regression model. A voxel by voxel linear least-squares fit of the BOLD signal time series to the PETCO2 data is then performed and the slope of the line of best fit was taken as CVR.

Data analysis

T1-weighted anatomical images were segmented into cerebrospinal fluid, grey matter and white matter using SPM8 (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, Institute of Neurology, University College, London, UK). CVR masks were generated that only contain grey matter. These were transformed into Montreal Neurological Institute space with SPM8. Unihemispheric SPM grey matter probability maps were thresholded at 70% in AFNI and served as a template for calculating hemispheric CVR for each participant. Manually traced regions of interest (ROIs) of each major arterial vascular territory (figure 2B–D) were identified by two neuroradiologists (DJM and DMM). An ROI was drawn for arterial territories supplied by the anterior cerebral artery (ACA), MCA, posterior cerebral artery (PCA) and cerebellum. Statistical analysis of pre-revascularisation and post-revascularisation CVR values comparisons were made using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed ranks test and comparisons with healthy controls were made using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Results were considered significant and accounted for multiple comparisons by Bonferroni correction if the per-comparison p value was less than 0.05/(12 comparisons)=0.004.

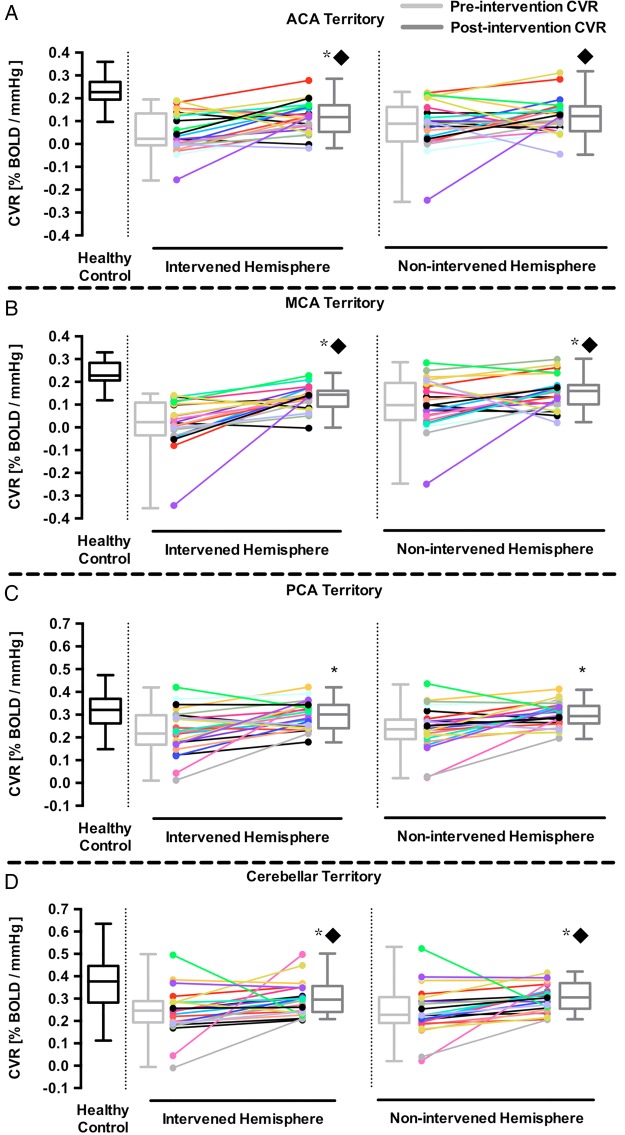

Figure 2.

Comparison of pre-revascularisation and post-revasculatisation grey matter CVR in the non-intervened and intervened hemispheres of patients with bilateral Moyamoya and steno-occlusive. The grey matter CVR of both the intervened and non-intervened hemisphere in the ACA (A) MCA (B) PCA (C) and cerebellar (D) territories. *p Value <0.05, compared to pre-revascularisation CVR. ▪p Value <0.05, compared to healthy subjects. The horizontal line in the box represents the median, box represents the interquartile range (25% to 75%), and the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum values. ACA, anterior cerebral artery; BOLD, blood-oxygen-level-dependent; CVR, cerebrovascular reactivity; MCA, middle cerebral artery; PCA, posterior cerebral artery.

Circle of Willis analysis

The images obtained from MR angiography of all 20 patients in this study were screened for variations in their circle of Willis (CoW) anatomy. Individuals were placed into four groups based on their anatomy: no anterior communicating artery (ACoA; n=5), missing one or both PCoAs (n=9), missing both ACoA and PCoA (n=3), or those having an intact CoW (n=3). CVR differences in each vascular territory were examined between all four groups and were tested for statistical significance using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction.

Results

The results from pre-revascularisation and post-revascularisation grey matter CVR in the intervened and non-intervened hemisphere of major arterial territories are summarised in table 1. The same analysis performed on fray matter was also performed on white matter and is summarised in online supplementary table S2 and shown in online supplementary figure S1.

Table 1.

Presurgical and postsurgical revascularisation grey matter CVR of major arterial territories compared to healthy subjects

| Territory | Hemisphere | Pre-revascularisation | Post-revascularisation | Healthy subjects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACA territory | Non-intervened | 0.078±0.024* | 0.126±0.017* | 0.229±0.010 |

| Intervened | 0.043±0.019* | 0.120±0.015*† | ||

| MCA territory | Non-intervened | 0.101±0.025* | 0.165±0.015*† | 0.229±0.012 |

| Intervened | 0.010±0.023* | 0.143±0.010*† | ||

| PCA territory | Non-intervened | 0.238±0.020 | 0.309±0.011† | 0.313±0.017 |

| Intervened | 0.228±0.022 | 0.309±0.012† | ||

| Cerebellar territory | Non-intervened | 0.249±0.025 | 0.309±0.014 | 0.370±0.027 |

| Intervened | 0.252±0.024 | 0.311±0.016 |

*p Value <0.005, compared to healthy subjects.

†p Value <0.005, compared to pre-revascularisation CVR.

All values in % MR signal change/mm Hg, mean±SE.

ACA, anterior cerebral artery; CVR, cerebrovascular reactivity; MCA, middle cerebral artery; PCA, posterior cerebral artery.

An analysis of CVR differences between patients with different CoW configurations is summarised in online supplementary table S3. Before each patient underwent a revascularisation procedure, all non-intervened hemispheres had visually normal vascular reserve (figure 1B). Quantitative analysis of grey matter CVR demonstrated that the pre-revascularisation cortical CVR in the MCA territory of the intervened hemisphere was 0.010±0.023%BOLD/mm Hg and 0.101±0.025%BOLD/mm Hg in the non-intervened hemisphere (figure 2). As expected, the post-revascularisation cortical CVR improved in the intervened hemisphere (0.010±0.023 to 0.143±0.010, p<0.05, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed ranks test). There was also a significant post-revascularisation improvement in grey matter CVR in the MCA territory of the non-intervened hemisphere (0.101±0.025 to 0.165±0.015, p<0.05, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed ranks test). Quantitative analysis of the white matter demonstrated post-revascularisation improvement in CVR in the MCA territory of the intervened hemisphere (−0.032±0.023 to 0.059±0.007, p<0.05, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed ranks test) but not in the non-intervened hemisphere (0.026±0.025 to 0.073±0.008, p<0.05, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed ranks test).

Discussion

The main finding of the study is that unilateral revascularisation of the symptomatic hemisphere in patients with bilateral steno-occlusive disease and MMD leads to improved haemodynamic vascular reserve in the cortex of the non-intervened hemisphere, particularly in the MCA, PCA and cerebellar territory. The non-intervened hemispheres had mean improvement of 46% compared with pre-revascularisation values. This implies that before intervention, collateral blood flow support from the non-intervened hemisphere to the affected hemisphere came at a cost of reduced reserve capacity. Revascularisation of the haemodynamically impaired hemisphere reduced its dependence for blood flow support from the non-intervened hemisphere, restoring vascular reserve, as indicated by an increase in CVR. This demonstrates that unilateral revascularisation can improve global CVR.

Literature comparison

Our results are consistent with previous studies showing that unilateral revascularisation increases blood flow in the contralateral non-intervened hemisphere. Importantly, Fierstra et al10 have shown that successful revascularisation in unilateral haemodynamically compromised patients with MMD can partially restore loss in cortical thickness in the non-intervened hemisphere.

Our results differ from those of Mandell et al22 who also examined pre-revascularisation and post-revascularisation (mainly STA–MCA bypass) CVR in 25 patients with intracranial steno-occlusive disease but in the context of determining the haemodynamic efficacy of EC–IC bypasses. The only significant post-revascularisation CVR changes were seen in the ipsilateral MCA territory. One important finding from this study was that the degree of post-revascularisation CVR improvement was correlated with the severity of haemodynamic impairment. The authors reported normal to near normal CVR in the non-operated hemisphere, which meant that there was little room for post-bypass CVR improvement. Our patient group had greater haemodynamic impairment indicated by the lower pre-bypass CVR values in the ACA, MCA, PCA and cerebellar territories in grey and white matter of both hemispheres (refer to table 1 and online supplementary table S2). Significant improvement in grey matter CVR was seen in both hemispheres of the MCA, PCA and cerebellar territories as well as the intervened territory of the ACA. Significant improvement in white matter CVR was seen in both hemispheres of the ACA, PCA and cerebellar territories as well as the intervened territory of the MCA. Although the post-revascularisation grey matter CVR of the non-intervened ACA territory and white matter CVR of the non-intervened MCA did not reach statistical significance, we can see that there is a trend toward haemodynamic improvement following revascularisation. In fact, we have seen CVR improvement in severe bilateral MMD (occurring in 11 of 13 patients; patients 3 and 4 did not improve) as well as in steno-occlusive disease from a single bypass (occurring in 5 out of 7 patients; patients 5 and 15 had reduced CVR following bypass). CVR assessment may therefore prove useful in surgical decision-making potentially obviating the need for bilateral bypass procedures in some cases.

Our results also differ from those of Ma et al.23 These authors examined CVR changes in the contralateral (non-intervened and asymptomatic) hemisphere using acetazolamide-enhanced Xenon-CT after unilateral STA–MCA bypass surgery in 15 patients with MMD. The authors reported a significant decrease in the CVR of the non-intervened hemisphere compared with preoperative values. The authors concluded that the unilateral STA–MCA bypass in patients with MMD led to a decrease in the CVR of the non-intervened hemisphere due to postsurgical reduction in collateral blood flow from the posterior circulation. However, regional CBF and CVR measurement time points were not consistently reported. Another limitation of Ma et al was the use of acetazolamide as a vasodilator. Acetazolamide is a drug that produces maximal vasodilatation for 20 min beginning 12–20 min after injection.24 According to the definition of CVR, the change in blood flow would be standardised by the administration of a standard dose of acetazolamide. This assumes that the dose of acetazolamide administered always achieves the same blood concentration of the drug. However, there is considerable variation in the blood concentration of the drug to a given dose and response to a given concentration, which raises issues concerning reproducibility of the test. Ito et al25 have shown that PETCO2 is equal to the partial pressure of CO2 in arterial blood in the method that we have applied in our study. As such, our stimulus was known and controlled with high precision.

Implications of the findings

Our results show that improvement in CVR can occur in both hemispheres following a unilateral revascularisation procedure. It would therefore seem that assessment of perfusion and/or CVR after any revascularisation procedure would be useful to determine the magnitude and spatial extent of improved flow metrics as an assessment of the efficacy of the revascularisation procedure.

We have previously reported that areas of impaired CVR are associated with cortical thinning that may be restored through successful surgical revascularisation.3 10 Whether restoration of vascular reactivity in the contralateral non-intervened hemisphere also leads to improvements in cognitive function remains to be resolved. A cross-sectional study by Balucani et al8 has recently shown that impaired haemodynamics are associated with cognitive dysfunction in patients with bilateral asymptomatic carotid stenosis. They report a significant reduction in performance scores of left and right brain cognitive tasks specific to the hemisphere that was haemodynamically impaired. Also, left and right brain performance scores were normal in hemispheres with preserved reserve. Although results from Balucani et al are not longitudinal, it does suggest better cognitive outcomes in areas with preserved CVR compared with areas of haemodynamic impairment. Longitudinal results from the RECON randomised trial demonstrated no benefit in cognition from EC–IC bypass surgery over medical therapy.26 Nonetheless, previous studies have demonstrated the association between improved vascular function with better cognitive performance.27 28

The precise mechanism for improved vascular reserve in the non-intervened hemisphere after unilateral revascularisation is unknown. In our study, a subanalysis was performed to analyse differences in CVR between those with variation in the anatomy of their CoW (online supplementary table S3). The magnitude of CVR increases post-revascularisation was similar regardless of whether or not patients had an intact CoW (table 2).

Table 2.

Grey matter CVR differences in the MCA territory between patients with and without an intact CoW

| Non-intervened hemisphere |

Intervened hemisphere |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-revascularisation | Post-revascularisation | Pre-revascularisation | Post-revascularisation | |

| Intact CoW | 0.131±0.044 | 0.197±0.041 | 0.024±0.016 | 0.147±0.005 |

| No ACoA+PCoA | 0.117±0.05 | 0.171±0.037 | 0.057±0.026 | 0.145±0.019 |

All values in per cent MR signal change/mm Hg, mean±SE.

No significant differences were seen between those with and without an intact CoW.

ACoA, anterior communicating artery; CoW, circle of Willis; CVR, cerebrovascular reactivity; MCA, middle cerebral artery; PCoA, posterior communicating artery.

In addition, only one patient had a fetal type PCA and this patient had similar pre-revascularisation CVR values and improvements in CVR post-revascularisation as those with an intact CoW. Those with an intact CoW have obvious conduits for collateral flow to the intervened hemisphere and therefore we expected the CVR in this group to be lower with a greater change in CVR post-revascularisation. Our findings show that those without an intact CoW had a lower CVR with a nearly similar increase in CVR after revascularisation. To our surprise, the results did not show statistically significant differences in the CVR of the MCA territory between those with an intact CoW and those without. Our expectations did not match our results and the CVR differences between each group may have been too subtle to detect with our small sample size. However, it is known that the leptomeningeal collaterals from the PCAs play an important role in maintaining perfusion in patients with MMD.29 We suspect that the revascularisation procedure reduces demand from the posterior circulation. As expected after successful revascularisation, compensation from the posterior circulation leptomeningeal collaterals is reduced resulting in improved PCA territory CVR (figure 2).

Another possibility for the non-differential CVR improvement despite differing CoW configurations is that during the initial stages of atherosclerosis or the formation of moyamoya-like vessels, the response of the downstream vasculature will be to lower flow resistance thereby attracting cross-flow from the contralateral hemisphere with relatively higher vascular reactivity. As stenoses become more advanced, the affected territory becomes maximally vasodilated and cannot lower flow resistance any further. In order to supply flow to the deficient region and maintain its own flow, donor regions lower flow resistance and in doing so consume vascular reserve. Donor flow sources do not necessarily need to supply flow through ACoA or PCoA conduits but would use leptomeningeal alternatives. When the resistance decreases, the autoregulatory reserve decreases as shown in the pre-revascularisation comparisons to healthy controls (table 1 and online supplementary table S2). When challenged with a global vasodilatory stimulus, flow will preferentially be redistributed to regions that can lower flow resistance to a greater degree. Restoring flow through surgical revascularisation will result in a global increase in perfusion pressure and resistance, particular in the intervened hemisphere. If restoration of vascular reactivity ensues in the bypassed territory, then vascular reserve will improve as well. There will be a reduced transfer of flow from donor territories. Theses territories will also therefore manifest restoration of vascular reactivity and reserve to more normal values.

Limitations

Our approach for assessing CVR is limited by the fact that the relationship between BOLD and blood flow is non-linear. However, the BOLD response to hypercapnia has already been shown to be dominated by CBF effects.24 30 31 Arterial spin labelling, which measures blood flow directly, may eventually replace BOLD for measurement of CVR, but it has not yet been validated for severe steno-occlusive disease associated with vascular occlusions and lengthy collateral circulation. Our subject population was also very heterogeneous as we made no attempt to select participants according to disease process, disease activity, medication or age. Chronic steno-occlusive disease and MMD differ in the development of various leptomeningeal, transdural and deep parenchymal collaterals13 that could affect the response to revascularisation in these two populations.

In summary, this work provides evidence that restoration of vascular reactivity can occur in the contralateral hemisphere following a unilateral revascularisation procedure. After restoration of baseline autoregulatory capacity in the haemodynamically compromised hemisphere by direct or indirect intervention, collateral blood flow support from the non-intervened hemisphere will decrease resulting in less blood being siphoned from the non-intervened hemisphere leading to global haemodynamic improvement. This important finding indicates that CVR mapping can provide important information concerning the efficacy of revascularisation. Although this research does not directly compare the efficacy of resting blood flow assessment (CT or MRI dynamic contrast perfusion methods) versus CVR methods for determining revascularisation efficacy, CVR is insensitive to transit time and input function issues that render the perfusion techniques unsuitable when extensive collateral networks have developed in patients with severe cerebrovascular disease. This confers a considerable advantage to CVR methods. As vascular function has been associated with cognitive performance, previous work suggests that restoration of blood flow may improve cognition.8 Future research on the association between post-revascularisation neuropsychological/cognitive performance and haemodynamic outcome is needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marat Slessarev and Alex Vesely for their contributions to the development of the breathing apparatus. They thank the Toronto Western Hospital RespirAct technologist Tien Wong as well as the MRI technologists, Eugen Hlasny and Keith Ta, for their contributions to the data acquisition.

Footnotes

Contributors: KS contributed to study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. JP contributed to data analysis and interpretation. OS, JSH and AB-C contributed to data interpretation and reviewed the manuscript. DMM, APC and JAF critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. MT was the neurosurgeon and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. DJM critically revised the manuscript and contributed to study supervision.

Funding: Financial support from the Canadian Stroke Network and the Ontario Research Fund (grant number RE 02-002) is gratefully acknowledged.

Competing interests: JAF is a co-inventor of the RespirAct, a device used in this study. He also holds shares and serves as a director of Thornhill Research Inc., a University of Toronto/University Health Network-related company, which retains an ownership position and will receive royalties should the RespirAct become a commercial product; DJM is a co-inventor of the RespirAct, a device used in this study; holds a minor equity position in Thornhill Research Inc., and has received research support from GE Healthcare, Siemens, Toshiba and the Ontario Research Fund.

Ethics approval: Health Canada's Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Conklin J, Fierstra J, Crawley AP et al. . Impaired cerebrovascular reactivity with steal phenomenon is associated with increased diffusion in white matter of patients with Moyamoya disease. Stroke 2010;41:1610–16. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.579540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fierstra J, Poublanc J, Han JS et al. . Steal physiology is spatially associated with cortical thinning. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81:290–3. 10.1136/jnnp.2009.188078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paulson OB, Strandgaard S, Edvinsson L. Cerebral autoregulation. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev 1990;2:161–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao WG, Luo Q, Jia JB et al. . Cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome after revascularization surgery in patients with Moyamoya disease. Br J Neurosurg 2013;27:321–5. 10.3109/02688697.2012.757294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandell DM, Han JS, Poublanc J et al. . Selective reduction of blood flow to white matter during hypercapnia corresponds with leukoaraiosis. Stroke 2008;39:1993–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.501692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silvestrini M, Vernieri F, Paqualetti P et al. . Impaired cerebral vasoreactivity and risk of stroke in patients with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA 2000;283:2122–7. 10.1001/jama.283.16.2122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoof J, Lubahn W, Baeumer M et al. . Impaired cerebral autoregulation distal to carotid stenosis/occlusion is associated with increased risk of stroke at cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;134:690–6. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balucani C, Viticchi G, Falsetti L et al. . Cerebral hemodynamics and cognitive performance in bilateral asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Neurology 2012;79:1788–95. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318270402e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown SC, Lam AM. Moyamoya disease—a review of clinical experience and anaesthetic management. Can J Anaesth 1987;34:71–5. 10.1007/BF03007690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fierstra J, Maclean DB, Fisher JA et al. . Surgical revascularization reverses cerebral cortical thinning in patients with severe cerebrovascular steno-occlusive disease. Stroke 2011;42:1631–7. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.608521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liebeskind DS, Cotsonis GA, Saver JL et al. ; Warfarin–Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) Investigators. Collateral circulation in symptomatic intracranial atherosclerosis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011;31:1293–301. 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liebeskind DS. Collateral circulation. Stroke 2003;34:2279–84. 10.1161/01.STR.0000086465.41263.06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shuaib A, Butcher K, Mohammad AA et al. . Collateral blood vessels in acute ischaemic stroke: a potential therapeutic target. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:909–21. 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70195-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liebeskind DS. Stroke: the currency of collateral circulation in acute ischemic stroke. Nat Rev Neurol 2009;5:645–6. 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liebeskind DS. Collaterals in acute stroke: beyond the clot. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2005;15:553–73. 10.1016/j.nic.2005.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gur AY, Bova I, Bornstein NM. Is impaired cerebral vasomotor reactivity a predictive factor of stroke in asymptomatic patients? Stroke 1996;27:2188–90. 10.1161/01.STR.27.12.2188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slessarev M, Han J, Mardimae A et al. . Prospective targeting and control of end-tidal CO2 and O2 concentrations. J Physiol 2007;581:1207–19. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.129395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kisilevsky M, Hudson C, Mardimae A et al. . Concentration dependent vasoconstrictive effect of hyperoxia on hypercarbia-dilated retinal arterioles. Microvasc Res 2008;75:263–8. 10.1016/j.mvr.2007.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vesely A, Sasano H, Volgyesi G et al. . MRI mapping of cerebrovascular reactivity using square wave changes in end-tidal PCO2. Magn Reson Med 2001;45:1011–13. 10.1002/mrm.1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fierstra J, Sobczyk O, Battisti-Charbonney A et al. . Measuring cerebrovascular reactivity: what stimulus to use? J Physiol 2013;591:5809–21. 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.259150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res 1996;29:162–73. 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandell DM, Han JS, Poublanc J et al. . Quantitative measurement of cerebrovascular reactivity by blood oxygen level-dependent MR imaging in patients with intracranial stenosis: preoperative cerebrovascular reactivity predicts the effect of extracranial-intracranial bypass surgery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011;32:721–7. 10.3174/ajnr.A2365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma Y, Li M, Jiao LQ et al. . Contralateral cerebral hemodynamic changes after unilateral direct revascularization in patients with Moyamoya disease. Neurosurg Rev 2011;34:347–54. 10.1007/s10143-011-0312-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuroda S, Houkin K, Kamiyama H et al. . Long-term prognosis of medically treated patients with internal carotid or middle cerebral artery occlusion: can acetazolamide test predict it? Stroke 2001;32:2110–16. 10.1161/hs0901.095692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito S, Mardimae A, Han J et al. . Non-invasive prospective targeting of arterial P(CO2) in subjects at rest. J Physiol 2008;586:3675–82. 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.154716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall RS, Festa JR, Cheung YK et al. ; RECON Investigators. Randomized Evaluation of Carotid Occlusion and Neurocognition (RECON) trial: main results. Neurology 2014;82:744–51. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moser DJ, Robinson RG, Hynes SM et al. . Neuropsychological performance is associated with vascular function in patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007;27:141–6. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000250973.93401.2d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haynes CD, Gideon DA, King GD et al. . The improvement of cognition and personality after carotid endarterectomy. Surgery 1976;80:699–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang APH, Liu HM, Lai DM et al. . Clinical significance of posterior circulation changes after revascularization in patients with Moyamoya disease. Cerebrovasc Dis 2009;28:247–57. 10.1159/000228254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogasawara K, Ogawa A, Yoshimoto T. Cerebrovascular reactivity to acetazolamide and outcome in patients with symptomatic internal carotid or middle cerebral artery occlusion: a xenon-133 single-photon emission computed tomography study. Stroke 2002;33:1857–62. 10.1161/01.STR.0000019511.81583.A8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vernieri F, Pasqualetti P, Matteis M et al. . Effect of collateral blood flow and cerebral vasomotor reactivity on the outcome of carotid artery occlusion. Stroke 2001;32:1552–8. 10.1161/01.STR.32.7.1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]