Summary

Intestinal epithelial stem cells (IESCs) control the intestinal homeostatic response to inflammation and regeneration. The underlying mechanisms are unclear. Cytokine-STAT5 signaling regulates intestinal epithelial homeostasis and responses to injury. We link STAT5 signaling to IESC replenishment upon injury by depletion or activation of Stat5 transcription factor. We found that depletion of Stat5 led to deregulation of IESC marker expression and decreased LGR5+ IESC proliferation. STAT5-deficient mice exhibited worse intestinal histology and impaired crypt regeneration after γ-irradiation. We generated a transgenic mouse model with inducible expression of constitutively active Stat5. In contrast to Stat5 depletion, activation of STAT5 increased IESC proliferation, accelerated crypt regeneration, and conferred resistance to intestinal injury. Furthermore, ectopic activation of STAT5 in mouse or human stem cells promoted LGR5+ IESC self-renewal. Accordingly, STAT5 promotes IESC proliferation and regeneration to mitigate intestinal inflammation. STAT5 is a functional therapeutic target to improve the IESC regenerative response to gut injury.

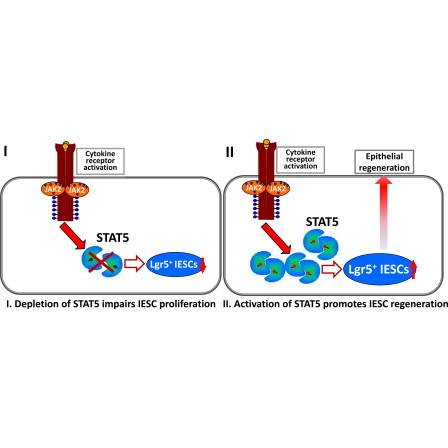

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Loss of STAT5 impairs intestinal stem cell proliferation

-

•

Activated STAT5 increases intestinal stem cell regeneration

-

•

Activation of cytokine-STAT5 signaling mitigates intestinal inflammation

In this article, Han and colleagues link STAT5 signaling to intestinal stem cell replenishment upon injury. They find that depletion of Stat5 leads to decreased stem cell proliferation, sensitizing mice to irradiation. In contrast, activation of STAT5 accelerates crypt regeneration, conferring resistance to gut injury. Therefore, activation of cytokine-induced STAT5 signaling promotes the regenerative capacity of intestinal stem cells to repair gut injury.

Introduction

Adult stem cells (SCs) retain the capacity of self-renewal and differentiation to generate multiple differentiated cell types (Barker et al., 2007). Thus, these adult SCs are utilized to functionally regenerate damaged tissues or reverse organ failure (Yui et al., 2012). However, SCs that are deregulated during inflammation, infection, or tissue regeneration may turn into invasive cancer SCs (CSCs) (Beachy et al., 2004). Accordingly, tight spatial-temporal regulation of adult SC behaviors may confer injury resistance, tissue regeneration, or tumor suppression, whereas SC deregulation may cause tumor initiation and/or recurrence (Merlos-Suárez et al., 2011). However, the lack of molecular markers that reflect the fine modulation of SC homeostatic response to injury or regeneration significantly hinders the development of regenerative medicine and cancer therapy.

Intestinal epithelial SCs (IESCs) are roughly categorized as either quiescent or active IESCs based in part on the expression of specific markers, including LGR5, Olfm4, Ascl2, BMI1, MTERT, and LRIG1 (Barker et al., 2007; Montgomery et al., 2011; Powell et al., 2012; Sangiorgi and Capecchi, 2008). They are believed to dynamically switch from one type to the other in response to inhibitory and stimulatory signals caused by cytokines, hormones, or growth factors (Li and Clevers, 2010). Active IESCs, the majority of which are LGR5+ crypt base columnar cells (CBCs), maintain intestinal lineage development and self-renewal with rapid cycling (Barker et al., 2007), and are highly sensitive to intestinal injury (Tian et al., 2011). In contrast, slow-cycling IESCs (label-retaining cells [LRCs]), which are present at the ‘‘+4 crypt position,’’ contribute to homeostatic regenerative capacity, particularly during recovery from injury (Takeda et al., 2011). These LRCs express markers such as BMI1, HOPX, LRIG1, and/or DCLK1, and can convert to rapidly cycling IESCs in response to injury (Yan et al., 2012). Signal transduction pathways, including WNT, NOTCH, TGF-β/BMP, Hedgehog, nuclear hormone receptor, and JAK-STAT, temporally and spatially regulate IESC homeostasis in cell-based tissue self-renewal and regeneration (Crosnier et al., 2006). Recent studies indicated that IESCs can regulate the intestinal homeostatic response to infection and inflammation (Buczacki et al., 2013). However, the mechanisms underlying this cellular regulation remain largely unknown.

JAK-STAT signaling was recently found to mediate IESC self-renewal and differentiation in response to bacterial infection and tissue impairment in Drosophila (Jiang et al., 2009). Compromised JAK-STAT signaling caused loss of IESC quiescence (Buchon et al., 2009), whereas JAK-STAT activation produced extra IESC-like and progenitor cells (Lin et al., 2010). However, the subsequent molecular events by which STAT signaling regulates adult IESCs are poorly defined in mammals. STAT5 activity, as well as its target genes, was predominantly associated with long-term self-renewal and maintenance of hematopoietic (Kato et al., 2005), mammary (Vafaizadeh et al., 2010), and embryonic SC (ESC) phenotypes (Kyba et al., 2003). Temporally controlled STAT5 expression and activation increased mammary SC proliferation, thereby contributing to the functional tissue formation upon chronic inflammatory injury (Vafaizadeh et al., 2010). We previously reported that epithelial STAT5 signaling is required for intestinal epithelial cell (IEC) integrity and homeostatic response to gut injury (Gilbert et al., 2012). Growth hormone (GH) and granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) can protect IECs against inflammatory injury through activation of STAT5 (Han et al., 2007, 2010). These findings suggest that STAT5 signaling mediates IEC repopulation through regulation of somatic IESC proliferation or differentiation. Here, utilizing Stat5-modified transgenic mouse models and mouse or human SCs, we characterized the role of STAT5 in IESC homeostasis and response to injury, and deciphered the molecular machineries of STAT5 activation in protecting gut injury. Furthermore, our findings suggest that STAT5 activation could be used as a functional marker for IESC intervention of gut injury.

Results

Depletion of Stat5 Leads to Deregulation of IESC Markers

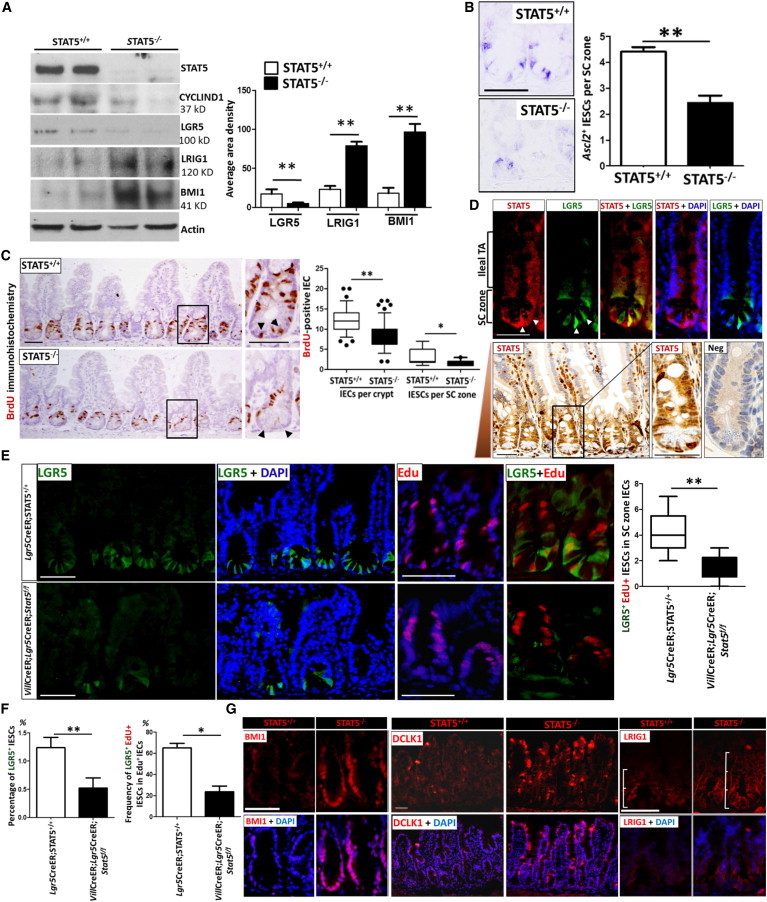

STAT5 has been demonstrated to govern hematopoietic SC fate and lineage commitment (Kato et al., 2005). Here, we sought to determine whether STAT5 signaling influences adult IESC activity. We previously reported that constitutively IEC STAT5-deficient mice (VilCre;Stat5f/f, hereafter called STAT5−/−) displayed dampened intestinal barrier regeneration and predisposition to intestinal inflammation (Gilbert et al., 2012). Infection, inflammation, and tumorigenesis occur mainly in the ileum or colon (Boland et al., 2005). Thus, we focused on the effects of STAT5 signaling on ileal and colonic IESCs. We first isolated IECs from STAT5−/− mice and littermate controls (Stat5f/f, STAT5+/+) to test the expression and distribution of IESC markers using immunoblotting, in situ hybridization, and immunofluorescence (IF). These analyses indicated that depletion of IEC STAT5 markedly decreased the expression of active IESC markers (LGR5, Ascl2, and Olfm4) (Figures 1A and 1B and Figure S1A available online) with concordant reduction of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation in the ileal crypt IECs (Figure 1C) and CBCs (insets in Figure 1C). To assess the effects of STAT5 signaling on LGR5+ IESCs (Kim et al., 2012), we generated inducible IEC STAT5-deficient mice with an Lgr5 knockin reporter gene (Lgr5-eGFP-IRES-CreERT2, hereafter called Lgr5CreER; Figure S1B). To investigate STAT5 expression in CBCs, we analyzed intestinal STAT5 and LGR5 GFP in Lgr5CreER;STAT5+/+ mice. STAT5+ IECs were robustly colocalized with LGR5 at the crypt base in the small and large bowel (Figures 1D, S1C, and S1D). Both IF and immunohistochemistry (IH) staining revealed that STAT5 was distributed in the intestinal crypt and transit-amplifying (TA) zone, and STAT5 expression displayed a gradient from the crypt to the villus tip (see arrow direction in Figure 1D). These data clearly indicate that both LGR5+ CBCs and LGR5− IESC have strong STAT5 expression, suggesting that STAT5 plays a role in CBCs, other IESC subpopulations, and progenitors. Using LGR5-GFP mice, we found that inducible depletion of IEC STAT5 markedly reduced LGR5+ IESCs (Figures 1E, 1F, and S1E). Double IF staining and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis with LGR5-GFP and 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) labeling showed a reduced LGR5+ IESC proliferation upon STAT5 depletion (Figures 1E, 1F, and S1E). These data were indicative of the requirement of STAT5 signaling for CBC proliferation. Consistently, depletion of Stat5 led to decreased percentage of EdU+ TA cells at the upper “+4” position (44.1% ± 5% in LgrCreER;STAT5+/+ mice versus 29% ± 3% in VilCreER;LgrCreER;Stat5f/f mice; p = 0.015, n ≥ 4 mice per group). In contrast to the reduced CBC and TA cell proliferation, STAT5 deficiency expanded the quiescent IESC pool as measured by IF staining of putative markers of quiescent IESC—BMI1 (Sangiorgi and Capecchi, 2008), LRIG1 (Powell et al., 2012), and DCLK1 (Westphalen et al., 2014; Figure 1G)—and remarkably increased the expression of these quiescent IESC markers (Figures 1A and 1G). Similarly, depletion of colonic IEC STAT5 caused suppression of active IESCs and expansion of quiescent IESC markers (Figures S1F–S1H). Therefore, intestinal Stat5 depletion is associated with deregulation of IESC markers, suggesting that IEC STAT5 signaling is required for maintenance of adult IESC homeostasis.

Figure 1.

Stat5 Depletion Leads to Deregulation of IESC Markers

STAT5−/− mice were generated using Villin Cre-mediated recombination to delete the Stat5 locus in IECs.

(A) Ileal IECs were isolated from STAT5−/− and STAT5+/+ mice. STAT5, CYCLIND1, LGR5, LRIG1, and BMI1 proteins were identified by immunoblotting. Signal intensity was determined by densitometry. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 5 mice per group; ∗∗p < 0.01).

(B) In situ hybridization analysis for Ascl2 in intestinal crypts. Ascl2+ IESCs were counted in 200 crypts and results are expressed as Ascl2+ IESCs per SC zone (n = 3 mice per group; ∗∗p < 0.01).

(C) IEC proliferation was determined by BrdU incorporation as measured by IH. Results are expressed as BrdU+ IECs per crypt or per SC zone and represented as box-and-whisker plots (black lines: medians; whiskers: 5%–95% percentiles; n ≥ 6 mice per group; ∗∗p < 0.01).

(D) Top panel: ileal frozen sections from LGR5 reporter mice were stained with STAT5 and LGR5-GFP double IF. Bottom panel: ileal STAT5 distribution was determined by IH staining. Arrow indicates the STAT5 expression gradient from the crypt to the villus tip. Antibody specificity was confirmed by lack of staining in STAT5-deficient intestine (Neg). TA, transit amplifying. Original magnification × 400, n = 3 mice.

(E) Lgr5-eGFP-IRES-CreERT2 (Lgr5CreER;STAT5+/+) and VillinCreERT2-Lgr5-eGFP-IRES-CreERT2-Stat5f/f (VilCreER;Lgr5CreER;Stat5f/f) mice were given Tam for 5 days. IF was used to detect GFP and EdU expression in ileal crypts. LGR5 GFP+ and EdU+ IESCs are shown. LGR5+EdU+ IESCs in the SC zone were counted and are represented as box-and-whisker plots (black lines: medians; whiskers: 5%–95% percentiles; n = 4 or 6 mice per group; ∗∗p < 0.01).

(F) IECs were dissociated and the frequency of LGR5 GFP+ and EdU+ IECs was measured by FACS. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6 mice per group; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01).

(G) Ileal frozen sections from STAT5−/− mice were immunostained with anti-BMI1 (red), DCLK1 (red), LRIG1 (red), and DAPI (blue). Scales represent ileal crypt length; n = 5 mice per group.

Scale bars, 50 μm. See also Figure S1.

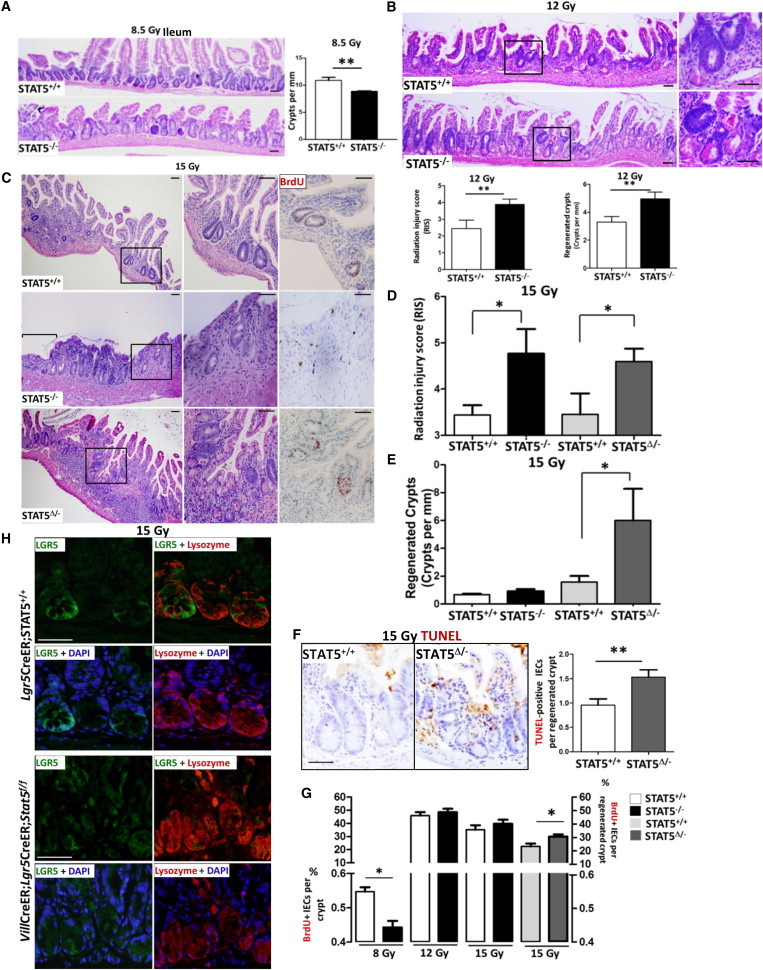

Depletion of Stat5 Impairs Crypt Regeneration to Deteriorate Radiation-Induced Mucositis

Dose-controlled radiation injury functionally distinguishes the IESC regenerative response (Hua et al., 2012; Metcalfe et al., 2014). After a high-dose exposure, CBCs undergo rapid apoptosis or mitotic death, whereas quiescent IESCs can be active and regenerate highly proliferative crypts (“microcolonies”) (Potten, 2004; Yan et al., 2012). Thus, we exposed both STAT5−/− and control mice to different doses of γ radiation (8.5, 12, or 15 Gy) and investigated IESC regenerative activity 3.5 days later. After exposure to 8.5 Gy radiation, which induces apoptosis and hyperproliferation of CBCs, but does not activate quiescent IESCs (Montgomery et al., 2011), STAT5−/− mice displayed moderate depletion of crypt numbers and mild crypt hyperplasia (Figure 2A), and pronounced flattened/blunt villi in jejunum compared with controls (Figure S2A). A dose of 12 Gy radiation led to intestinal mucositis in all mice (Figure 2B). STAT5−/− mice exhibited worse mucosal injury with a higher radiation injury score (RIS) and mucosal ulceration compared with controls (Figure 2B). Quiescent IESCs have been suggested to represent an IESC subpopulation that is committed to differentiation to Paneth cells or endocrine lineages, and can replenish the IESC pool upon injury (Buczacki et al., 2013). We found that depletion of STAT5 led to increased “immature” crypts in the ileum and jejunum, which were characterized by impaired regeneration and repair of irradiation-induced mucosal injury. The “immature” crypt regeneration coincided with an increased number of lysozyme+ Paneth cells (Figures 2B, S2B, and S2C), suggesting that quiescent IESCs could be activated in STAT5−/− mice. To rule out the influence of IEC barrier differentiation defects in STAT5−/− mice on the radiation response, we crossed Villin-CreERT2 with Stat5f/f mice to inducibly deplete IEC STAT5 using tamoxifen (Tam)-dependent Cre recombinase activation (STAT5Δ/−). LGR5+ CBCs can be greatly diminished after 12 Gy radiation, but a fraction of surviving LGR5+ CBCs may overcome the G1 arrest to reenter the cell cycle after DNA damage repair is completed (Hua et al., 2012; Van Landeghem et al., 2012). We thus escalated the radiation dose to 15 Gy and investigated the inducible depletion of STAT5 upon intestinal crypt regeneration (Hua et al., 2012). Consistently, inducible STAT5 depletion led to a significantly worse RIS and more severe mucosal injury compared with Tam-treated littermate controls (STAT5+/+) (Figures 2C and 2D). STAT5Δ/− mice also contained a significantly higher number of “immature” regenerated crypts (Figures 2C and 2E). Interestingly, by TUNEL staining, we found that the regenerative crypts with STAT5 deficiency displayed more apoptotic IECs than control mice after irradiation (Figure 2F), suggesting that STAT5 plays a nonredundant role in controlling crypt regeneration during injury. BrdU incorporation confirmed that 8.5 Gy radiation reduced intestinal crypt epithelial proliferation in the STAT5−/− mice compared with littermates (Figure 2G). However, 15 Gy radiation induced more crypt epithelial regenerative proliferation with greater apoptotic IECs in the STAT5Δ/− mice compared with Tam-treated littermate controls (Figures 2F, 2G, and S2D). These data indicate that STAT5 deficiency alters the regenerative capacity of IESCs, leading to “immature” crypt regeneration after irradiation. IEC STAT5-deficient mice with the Lgr5 reporter gene were then exposed to 15 Gy irradiation (Figure 2H). LGR5 GFP and lysozyme double IF staining showed that inducible depletion of STAT5 reduced LGR5+ IESCs, whereas lysozyme+ Paneth cells were coincidently increased in the “immature” regenerated crypts compared with littermate controls (Figure 2H), indicating increased radiation-induced damage in STAT5Δ/− mice. These regenerated crypts had less Ascl2 abundance than controls (Figure S2E), suggesting that STAT5 signaling is required for LGR5+ IESC regeneration upon radiation injury. Together, these data indicate that depletion of STAT5 impairs crypt regeneration, and STAT5 is indispensable for IESC regenerative activity to repair mucosal injury. We next tested the possible mechanisms of how STAT5 controls IESC regeneration.

Figure 2.

Stat5 Depletion Dampens IESC Regenerative Activity and Increases Radiation-Induced IESC Injury

(A and B) STAT5−/− and STAT5+/+ mice were exposed to γ radiation (8.5 or 12 Gy). Crypt proliferation in the ileum was determined 3.5 days after an initial 8.5 Gy radiation (A), and the RIS and crypt regeneration were determined 3.5 days after 12 Gy radiation (B). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6 mice per group; ∗∗p < 0.01).

(C–E) IEC STAT5 was depleted by intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of Tam (1 mg/mouse/day) for 5 consecutive days; simultaneously, controls were injected with sunflower oil. RIS and mucosal ulceration (C and D) and crypt regeneration (C and E) were determined in the mice with constitutive or inducible depletion of IEC STAT5 (STAT5−/− or STAT5Δ/−) at 3.5 days after 15 Gy radiation. Ulcer area is designated by brackets in (C). Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n ≥ 6 mice per group; ∗p < 0.05).

(F) Apoptotic IECs in the regenerated ileal crypts were detected by TUNEL staining and expressed as TUNEL+ IECs per regenerated crypt. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 5 mice per group; ∗∗p < 0.01). Representative images are shown.

(G) STAT5−/− and STAT5Δ/− mice were exposed to 8.5, 12, or 15 Gy radiation. At 3.5 days after radiation, mice were administered with BrdU and sacrificed 3 hr later. The percentages of proliferative IECs in the crypts or regenerated crypt were measured by BrdU incorporation. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 5 mice per group; ∗p < 0.05).

(H) Lgr5CreER;STAT5+/+ and VilCre;Lgr5CreER;Stat5f/f mice were exposed to 15 Gy radiation. Ileal frozen sections were double stained with LGR5 GFP (green) and lysozyme (red). Representative images are shown (n = 3 mice per group).

Scale bars, 50 μm. See also Figure S2.

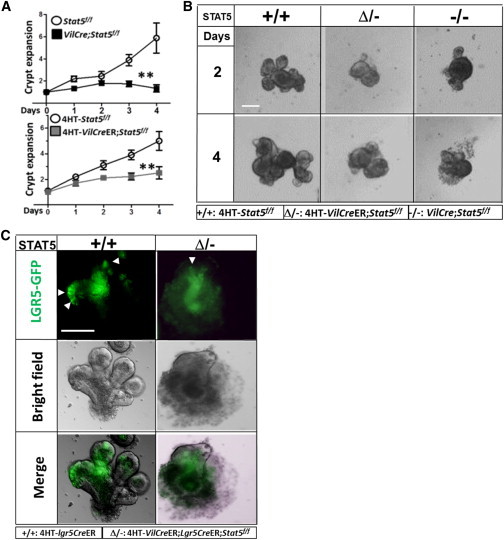

Depletion of Stat5 Inhibits CBC Activity, Leading to Reduced Crypt Expansion

To recapitulate STAT5 loss-of-function (LOF) phenotypes in vitro, we isolated mouse intact crypts from STAT5−/− and STAT5Δ/− mice, and generated intestinal enteroids to observe crypt formation over time. We found that enteroids from STAT5−/− mice were not capable of budding and forming crypts with the same enriched conditions as control enteroids (Figures 3A and S3A). The enteroids with Tam-inducible STAT5 depletion in IEC exhibited limited crypt expansion and formation (Figures 3A and 3B), indicating that STAT5 LOF dampened CBC self-renewal and differentiation. Intriguingly, the expression of Bmi1 was significantly increased by STAT5 depletion, whereas Lgr5 expression remained unaltered in the enteroids as assessed by quantitative PCR (qPCR; Figure S3B), suggesting that depletion of STAT5 could lead to BMI1+ IESC activation. However, using VilCreER;Lgr5CreER;Stat5f/f mice, we found that inducible STAT5 depletion resulted in reduced LGR5-GFP+ crypt buds in the enteroids (Figure 3C). Therefore, depletion of STAT5 inhibits CBC activity.

Figure 3.

Stat5 Depletion Reduces IESC Proliferation

(A and B) Ileal crypts were isolated from Stat5f/f, VilCreER;Stat5f/f, and VilCre;Stat5f/f mice, and resuspended in Matrigel with EGF, Noggin, and R-spondin for culture from day 1 through day 8. Then, 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4HT, 1 μM) was used to induce STAT5 depletion in the enteroids. Enteroids were cultured in six parallel wells per mouse for each experiment (n = 4 mice per group). The number of crypt buds was counted daily in a minimum of 10 enteroids per well with either persistent or 4HT-induced STAT5 depletion (−/− or Δ/−).

(A) Results are expressed as a graph of crypt expansion, showing the number of crypt buds versus time. One-way ANOVA was used to test for variance of two groups (∗∗p < 0.01).

(B) Representative expanded crypts are shown.

(C) Ileal crypts were isolated from Lgr5CreER and VilCreER;Lgr5CreER;Stat5f/f mice. GFP fluorescence and bright-field images of single LGR5-GFP cells in 7-day-old enteroids are shown. The data are representative of three independent experiments.

Scale bars, 100 μm. See also Figure S3.

Transgenic Mice with Inducible Expression of a Gain-of-Function Stat5 Variant

To study STAT5 gain of function (GOF) upon IESC response to gut injury, we generated an inducible transgenic mouse model with a GOF variant of Stat5a (termed icS5) using bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) recombineering (Muyrers et al., 1999). We selected the BAC RP23-362J7, which encompasses the entire endogenous Stat5a and Stat5b. The transgene vector was constructed with the appropriate 3′ and 5′ homologous arms and the enhanced and prolonged active Stat5a variant (FLAG tagged at the C terminus). Truncated human CD2 was used as a transgenic reporter marker (Figure S4A). We then performed RecE and RecT recombination of the construct into the BAC. The final BAC harbored the icS5-FLAG-IRES-hCD2 construct, flanked by LoxP sites in an antisense orientation within the endogenous Stat5a locus (Figure S4A). This allowed expression of the icS5 construct under regulation of the endogenous promoter after Cre recombination (Figure 4A). The recombination of the construct into the BAC was confirmed by two independent Southern blot strategies (for further details, see the Supplemental Experimental Procedures and Figures S4B–S4D).

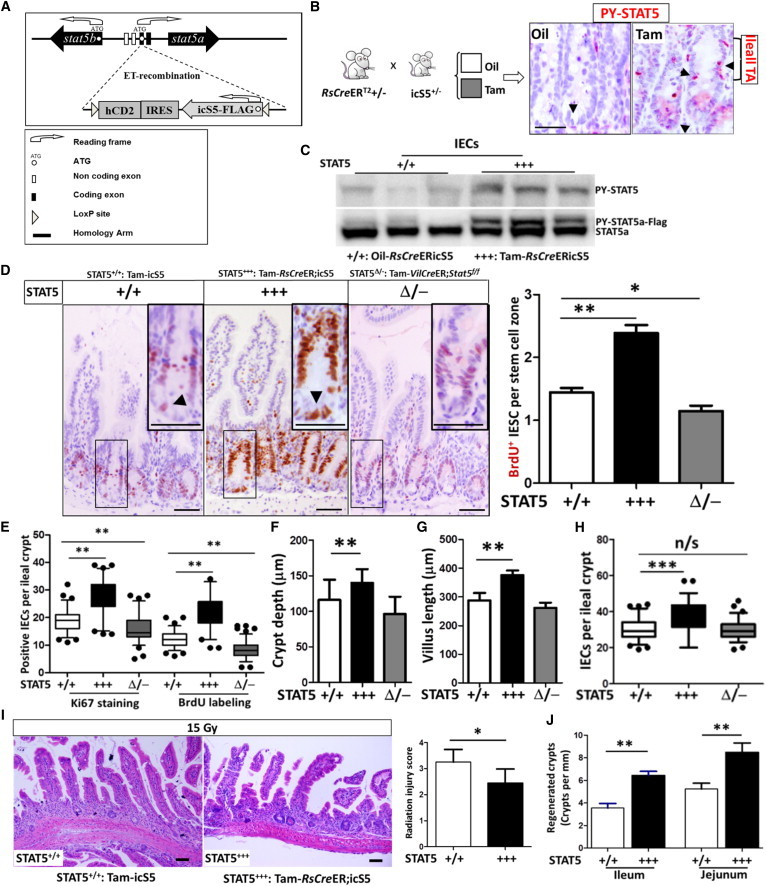

Figure 4.

STAT5 Activation Increases CBC Proliferation and Expands the IEC Progenitor Pool, Conferring Resistance to Radiation-Induced Intestinal Injury

(A) Schematic representation of the BAC construct used to generate inducible GOF Stat5a. The endogenous Stat5a locus in transgenic BAC is replaced by the icS5 construct in the “off” orientation. The transgene can be switched “on” upon recombination by Cre recombinase, leading to the expression of icS5 under endogenous promoter regulation.

(B and C) icS5 transgenic mice were crossed with RsCreER;icS5 mice. RsCreER;icS5 mice were then injected with oil or Tam.

(B) Tyrosine phosphorylated STAT5 (PY-STAT5) (pink, arrows) was determined in intestine by IH.

(C) IECs were isolated from oil- or Tam-treated RsCreER;icS5 mice (STAT5+++), and PY-STAT5 and STAT5a were determined by immunoblotting (n = 4 mice per group).

(D–H) Five days after Tam-induced STAT5 activation, IEC or CBC proliferation was determined by in situ BrdU incorporation or Ki67 staining. BrdU+ and Ki67+ IECs were quantified as positive IECs per IESC zone (D) or per ileal crypt (E). Ki67+ CBCs (arrows in the insets) and IECs were markedly increased by activation of STAT5, in contrast to the reduction of proliferating CBCs in STAT5-depleted crypts (D and E). Representative images are shown in (D). Ileal growth was evaluated according to crypt depth (F) and villus length (G), and the total cell count per ileal crypt (H) was measured using ImageJ. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6 mice per group; ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

(I and J) Mice with inducible STAT5 activation were exposed to γ-radiation. At 3.5 days after the initial 15 Gy radiation, the RIS (I) and crypt regeneration (J) were determined. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6 mice per group; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01).

Scale bars, 50 μm. See also Figures S4 and S5.

STAT5 Activation Increases CBC Proliferation and Expands the IEC Progenitor Pool, Conferring Resistance to Radiation-Induced Intestinal Injury

We next crossed icS5 mice with Rosa26-CreERT2 mice (RsCreER;icS5) to induce Cre-LoxP inversion (Figure 4B). The RsCreER;icS5 mice were then treated with Tam, and recombination of the icS5 transgene into the “on” orientation was confirmed by Southern blot (Figure S4B). Genomic recombination was detected in all organs tested, and full activation of the transgene reflected a monoallelic expression of the icS5 GOF variant, which is very sensitive to cytokine signaling. In liver, lung, kidney, bone marrow, and splenocytes, Southern blotting (Figure S4E) or FACS displayed hCD2, the reporter marker that is transcriptionally linked to icS5 preceded by an IRES sequence (Figure S4F). We also tested STAT5 activation (PY-STAT5) in the intestine. Ileal sections were stained with PY-STAT5 IH (Figure 4B) or the total proteins from isolated ileal IECs were immunoblotted for STAT5a or PY-STAT5 (Figure 4C). We found that STAT5 was robustly activated in IECs from Tam-induced RsCreER;icS5 mice (Tam-RsCreER;icS5, hereafter called STAT5+++; Figure 4C), which was mainly distributed in the ileal IESC and TA zone (Figure 4B). BrdU incorporation and Ki67 staining exhibited a pronounced crypt IEC proliferation compared with sunflower oil-treated RsCreER;icS5, Tam-induced icS5 (STAT5+/+), or Tam-induced VilCreER;Stat5f/f mice (STAT5Δ/−; Figures 4D and 4E). In particular, more proliferative CBCs were observed in STAT5+++ mice than in STAT5+/+ mice (insets in Figure 4D). These proliferating crypt IECs led to an elongated ileal crypt depth (Figure 4F) and villus height (Figures 4F and S5A) with enhanced IEC growth (Figure 4H), suggesting that in vivo activation of STAT5 enhances IESC self-renewal, leading to intestinal growth. We then exposed STAT5+++ mice to 15 Gy radiation. These mice exhibited milder mucositis compared with oil-induced RsCreER;icS5 or Tam-induced icS5 mice (Figure 4I). Intriguingly, 3.5 days after radiation, activation of STAT5 in mice gave rise to more regenerated crypts (Figure 4J) with robust expression of STAT5a and BrdU+ IECs (Figure S5B) compared with controls. Using Tam-inducible Cre recombinase driven by the IEC-specific Villin promoter, STAT5 was inducibly activated in the IECs. We consistently found that inducible activation of IEC STAT5 enhanced CBC proliferation in the ileum and jejunum (quantified as BrdU+ CBC per SC zone), and increased ileal crypt depth and crypt regeneration (Figures S5C and S5D). These data demonstrate that activation of IEC STAT5 may promote more active IESCs, leading to functional crypt regeneration. In contrast to depletion of IEC STAT5, activation of IEC STAT5 reduced the expression of quiescent markers (LRIG1 and DCLK1) as measured by IF and immunoblotting, suggesting a diminished number of quiescent IESCs in the STAT5-activated mice (Figure S5E). Therefore, our data suggest that GOF of STAT5 promotes IESC regeneration to repair intestinal injury.

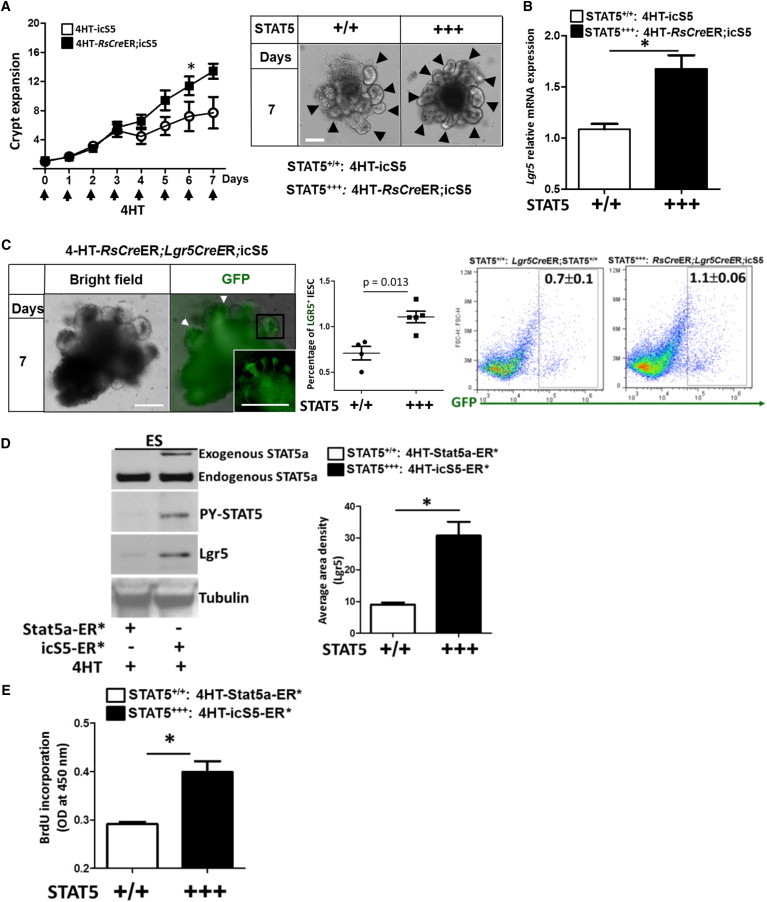

STAT5 Activation Promotes IESC Self-Renewal, Leading to Increased Crypt Expansion

To recapitulate our in vivo observation of STAT5 activation upon IESC activity, we cultured IESCs from RsCreER;icS5 mice and then induced activation of STAT5 using Tam. We found that STAT5 activation significantly enhanced crypt expansion (Figure 5A) along with a strongly upregulated Lgr5 expression in the IESCs compared with control enteroids (Figure 5B). We then crossed Lgr5CreER mice with RsCreER;icS5 mice and cultured LGR5+ IESCs. Consistently, FACS analysis showed that the frequency of LGR5+ IESCs was markedly increased by Tam-induced STAT5 activation (Figure 5C). These data suggest that STAT5 activation increases LGR5+ active IESC self-renewal. We then sought to determine whether our finding that STAT5 signaling impacts the regulation of mouse IESC activity is more broadly applicable to other SC types. To that end, we selected H1 human ESCs (hESCs) to confirm the findings from our adult mouse IESCs. We used lentivirus harboring a Tam inducible STAT5a (STAT5a-ER∗ or icS5-ER∗; Figure S6A; Grebien et al., 2008) to transduce the hESC cells. In this system, we were able to ectopically express activated STAT5 by addition of Tam (Figure 5D). We found that STAT5 activation significantly increased LGR5 (Figure 5D) and promoted hESC cellular proliferation as assessed by BrdU incorporation (Figure 5E), suggesting that the ability of STAT5 to regulate SC activation in vitro is not confined to mouse IESCs. Taken together, these results indicate that activation of STAT5 can accelerate CBC proliferation and enhance crypt formation and differentiation.

Figure 5.

STAT5 Activation Promotes IESC Activity, Increasing Crypt Expansion

Ileal and jejunal crypt crypts were isolated from icS5 and RsCreER;icS5 mice and cultured for 8 days; 200 nM 4HT was used to induce STAT5 activation during culture.

(A) The number of ileal crypt buds was counted per enteroid (n ≥ 10) from each of six wells from three independent experiments. The results are expressed as a graph of crypt buds versus time; the data are representative of three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA was used to test for variance of two groups (∗p < 0.05). Representative images are shown; arrows indicate the expanded crypts.

(B) Lgr5 expression was analyzed by qPCR in 4HT-treated ileal enteroids cultured from icS5 and RsCreER;icS5 mice. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 5 mice per group; ∗p < 0.05).

(C) The frequency of LGR5+ GFP cells was detected by FACS in 7-day old enteroids cultured from Lgr5CreER;STAT5+/+ and RsCreER;Lgr5CreER;icS5 mice. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 4 or 5 mice per group).

(D and E) H1 hESCs were transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing STAT5a-ER∗ or icS5-ER∗ variants.

(D) After puromycin selection, 200 nM 4HT was used to induce STAT5 activation. Total proteins were then extracted for anti-STAT5a, anti-PY-STAT5, anti-LGR5, and anti-Tubulin immunoblottings.

(E) H1 hESCs (2 × 104 cells/ml) were seeded into 96-well plates and BrdU incorporation was used to measure cell proliferation. Data represent three independent experiments and results are expressed as the mean ± SEM (∗p < 0.05).

Scale bars, 100 μm. See also Figure S6.

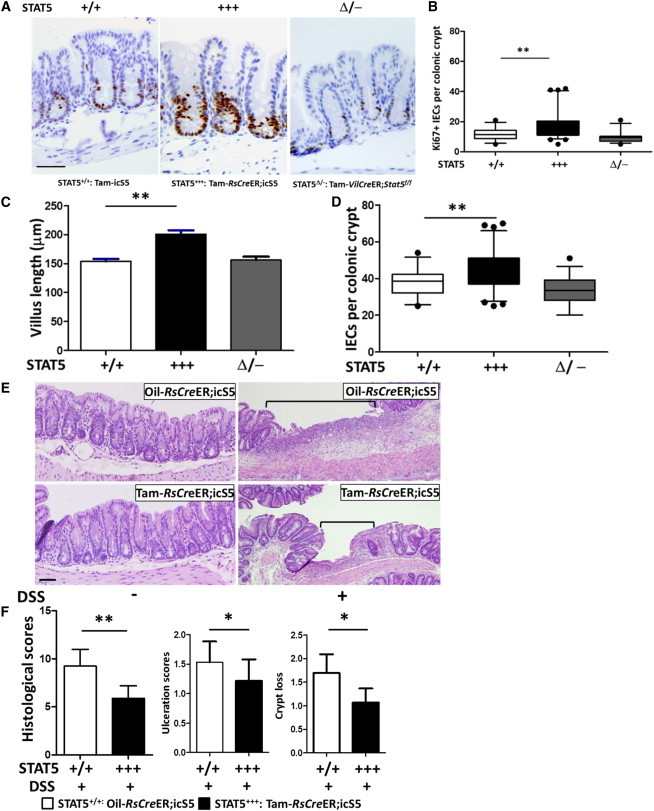

STAT5 Activation Increases Colonic IESC Growth in Response to Colitis-Induced Epithelial Injury and Ulceration

Dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colonic mucosal ulceration can be repaired by direct implantation of LGR5+ IESCs or significantly improved by induction of IESC proliferation (Ju et al., 2013; Yui et al., 2012). To explore the potential for clinical application of genetic activation of Stat5, we tested enhanced STAT5 activation upon experimental colitis-induced IEC injury. We first tested the effect of GOF of STAT5 on colonic IESCs in vivo. Similar to what was observed for ileal IESCs, inducible activation of STAT5 increased colonic IESC proliferation (Figures 6A and 6B), colonic crypt depth, and growth compared with controls (Figures 6C and 6D). These data indicate that activation of STAT5 leads to colonic epithelial growth by promoting IESC proliferation. We then exposed icS5 and RsCreER;icS5 mice treated with oil or Tam to 3% DSS for either a 7-day acute injury or a 5-day DSS exposure after 5-day water recovery (Gilbert et al., 2012). STAT5+++ mice exhibited resistance to DSS-induced colonic mucosal inflammation as characterized by lower histopathological scores, less crypt loss, and smaller ulcer area compared with controls (Figures 6E and 6F), but displayed mildly increased immune cell infiltration. However, after water recovery, there was no significant difference in colonic histological score between STAT5+++ and control mice (Figures S6B and S6C). These investigations further confirmed that activation of STAT5 protects against colonic epithelial injury, possibly through induction of colonic IESC growth. Thus, STAT5 is a functional therapeutic target to improve the regenerative response to gut inflammation.

Figure 6.

STAT5 Activation Increases Colonic IESC Growth to Protect against Colitis-Induced Epithelial Injury and Ulceration

(A–D) Colonic IEC proliferation was determined by Ki67 IH (A), and Ki67+ colonic IECs were increased by inducible activation of STAT5 (B). Colonic growth was measured by villus length (C) and total cell count per colonic crypt (D). Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 8 mice per group; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01).

(E and F) Colonic inflammation was induced by 3% DSS for 7 days. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed significant resistance to DSS-induced colonic injury and ulceration in STAT5+++ mice. Ulcer area is designated by brackets in (E). Mucosal injury, colonic mucosal ulceration, and crypt loss are scored in (F). Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 6 or 8 mice per group; ∗p < 0.05).

Scale bars, 50 μm. See also Figure S6.

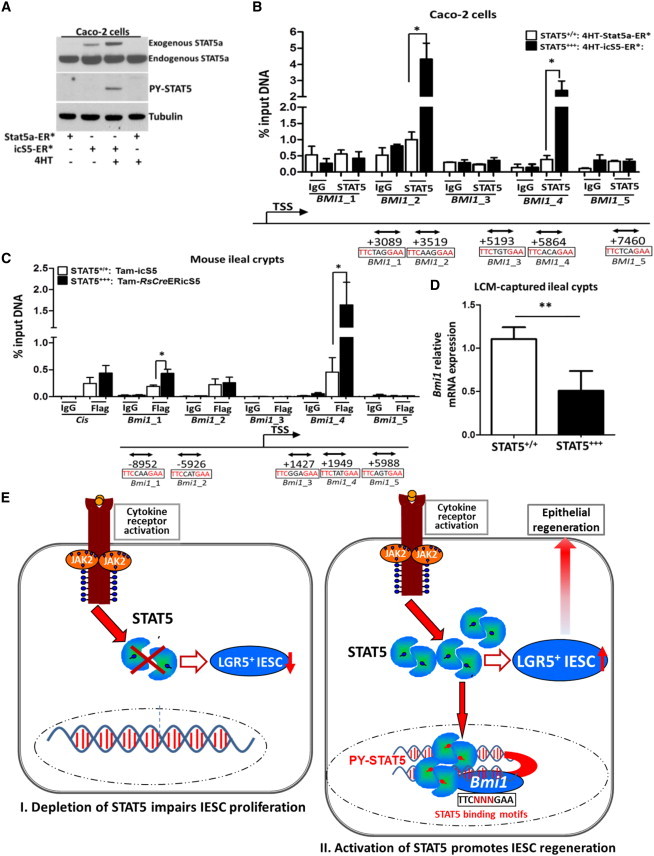

STAT5 Binds Directly to the Bmi1 Locus and STAT5 Activation Represses Bmi1 Expression

Human colonic carcinoma Caco-2 cells spontaneously differentiate into an enterocyte-like phenotype expressing IESC markers such as LGR5 and BMI1 (Pereira et al., 2013). To further explore the molecular mechanisms of how activated STAT5 enhances active IESC activity, we transduced subconfluent Caco-2 cells with lentivirus harboring a Tam-regulatable STAT5a (STAT5a-ER∗ or icS5-ER∗; Figure S6A). Initially, we demonstrated that Tam exposure stimulated the activation of STAT5 (Figure 7A). Given that STAT5 plays a critical role in trans-activating or -repressing target genes (Stine and Matunis, 2013), we then scanned the Bmi1 locus for putative STAT5 binding sites using the inverted repeat consensus (TTC(N3)GAA). Computational prediction indicated that there were seven putative binding sites in the human Bmi1 locus (Tables S1A and S1B) and 13 putative binding sites in the mouse Bmi1 locus (Tables S2A and S2B). Based on these predictions, we utilized chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay to study interactions between STAT5 protein and the Bmi1 locus. In Caco-2 cells, ChIP analysis with anti-STAT5 antibodies or control immunoglobulin G (IgG) followed by qPCR identified two GAS motifs (sites 2 and 4) in the BMI1 locus that showed mild STAT5 binding enrichment (Figure 7B) and in which the STAT5 binding intensity was significantly elevated by genetic activation of STAT5 (Figure 7B). To test our finding with primary cells, we next isolated mouse ileal crypts and subjected these crypts to in vivo ChIP analysis with anti-FLAG antibodies or control IgG to immunoprecipitate STAT5. We identified three GAS motifs (sites 1, 2, and 4) that exhibited moderate STAT5 binding enrichment, and two binding sites (sites 1 and 4) that revealed a markedly increased STAT5 binding intensity by genetic activation of STAT5 (Figure 7C). These ChIP data indicate that STAT5 protein can bind to the Bmi1 locus, and enhanced STAT5 protein activity correlates with more Bmi1 locus binding. Finally, we measured Bmi1 mRNA expression. We found a significant reduction of Bmi1 mRNA levels in ileal crypts of Stat5-activated mice compared with wild-type controls (Figure 7D). Collectively, our data suggest that activation of STAT5 controls IESC regeneration in mouse small intestines and human colonic cells in part through repression of Bmi1 expression.

Figure 7.

STAT5 Binds to the Bmi1 Locus to Repress Bmi1 Expression

(A) Subconfluent Caco-2 cells were transduced with lentiviral constructs expressing STAT5a-ER∗ or icS5-ER∗ variants. Then, 200 nM 4HT was used to induce activation of STAT5 and total proteins were extracted for anti-STAT5a, anti-PY-STAT5, and anti-Tubulin immunoblotting. Data represent three independent experiments.

(B and C) Proteins and DNA complexes from Caco-2 cells or mouse ileal crypts were crosslinked, sheared, and immunoprecitated.

(B) Purified DNA from the total input DNA, normal rabbit IgG, or anti-STAT5 immunoprecipitates from Caco-2 cells in three independent experiments were analyzed by qPCR for the human BMI1 locus.

(C) DNA complexes from ileal crypts were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies and the purified DNA was analyzed for the mouse Bmi1 locus. Consensus STAT5 binding sites are indicated as lines with double arrows, and positions relative to the Bmi1 transcription start site (TSS) are shown. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 4 mice per group; ∗p < 0.05).

(D) Ileal frozen sections were prepared from STAT5+++ mice. Ileal crypts were captured by laser capture microdissection. Bmi1 expression was determined by qPCR. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 5 mice per group; ∗∗p < 0.01).

(E) Schematic overview of the role of STAT5 signaling in IESCs. STAT5 LOF impairs IESC proliferation (I), and STAT5 GOF promotes IESC regeneration to repair IEC injury (II).

See also Figure S6 and Tables S1–S3.

Discussion

IESCs and intestinal progenitor cells maintain intestinal homeostasis and regeneration in response to gut injury (Zhang et al., 2014). LGR5+ IESCs play a critical role in intestinal homeostasis and regeneration (Metcalfe et al., 2014; Van Landeghem et al., 2012). Interestingly, BMI1+ IESCs are able to replenish LGR5+ IESC upon small-intestinal injury or regeneration (Yan et al., 2012). However, the molecular mechanisms that regulate these two IESC populations remain largely unexplored. Mucosal cytokines regulate IESC responses to inflammation, in part by JAK-STAT signaling (Farin et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2009). In this study, we investigated whether cytokine-STAT5 signaling plays a role in modulation of these two IESC populations during IEC regeneration. Based on the combined results of our LOF and GOF studies of STAT5 in murine models with cultured mouse or human SCs, we propose a model in which, first, loss of STAT5 impairs rapidly cycling IESCs (Figure 7E-I), and second, genetic activation of Stat5 promotes CBC proliferation and regeneration (Figure 7E-II). However, our current data cannot exclude the potential effects of STAT5 signaling on intestinal progenitors or mucosal cytokine secretion. Interestingly, ChIP analyses identified STAT5 binding to the Bmi1 locus, suggesting that activated STAT5 could directly regulate key genes involved in IESC identity. Collectively, STAT5 controls adult IESC activity upon intestinal injury. PY-STAT5 could be developed as a biomarker for IESC regeneration of inflamed epithelia.

Previous studies have used acute irradiation-induced injury models to provide mechanistic insight into the regeneration process, revealing that actively proliferating IESC (active IESC) and slowly proliferating IESC (quiescent IESC) populations occur within the lower regions of the crypt (Barker et al., 2007; Tian et al., 2011). Quiescent IESCs can be activated to replenish injured active IESCs upon high-dose irradiation (Tian et al., 2011). However, it is unclear which doses of irradiation can activate the quiescent IESCs (Hua et al., 2012; Potten, 2004; Yan et al., 2012). We found that 12 Gy irradiation did not completely ablate all ileal crypt regeneration in STAT5−/− mice, whereas 15 Gy irradiation significantly diminished the regeneration of ileal crypts in STAT5−/− mice. Thus, we utilized 15 Gy irradiation to investigate the effects of STAT5 LOF or GOF on IESC regeneration and “microcolony” formation.

It was previously reported that conditional deletion of HSC STAT5 results in loss of quiescence associated with reduced survival and loss of the long-term HSC pool (Wang et al., 2009). Conversely, hyperactivation of STAT5 increases erythroid differentiation, and low or intermediate activation of STAT5 enhances self-renewal of HSCs (Wierenga et al., 2008). Interestingly, oncogenic NrasG12D activation in HSCs defined a key role for STAT5 signaling in mediating both the increased proliferation and engraftment potential of NrasG12D/+ HSCs (Li et al., 2013). Here, we demonstrated that depletion of IEC STAT5 caused inhibition of CBC self-renewal, leading to limited crypt expansion in the cultured enteroids. In contrast, ectopic activation of STAT5 increased IESC proliferation and regeneration to promote crypt expansion. Therefore, STAT5 activity is required for IESC self-renewal and regenerative activity. However, our finding does not rule out possible effects of Stat5 depletion on IESC survival. In future studies, we will further measure the efficiency of enteroid formation with single IESCs to determine the direct effects of STAT5 on IESCs.

BMI1+ IESCs have a slower rate of proliferation compared with LGR5+ IESCs and can give rise to all IEC lineages, particularly during recovery from injury (Sangiorgi and Capecchi, 2008; Yan et al., 2012). However, there is no clear evidence of a cytokine-signaling pathway that regulates their switch from quiescence to active cycling. Our data show that deletion of IEC STAT5 led to increased expression of quiescent IESC makers in the crypts, suggesting that quiescent IESCs could be activated in the STAT5−/− mice. After exposure to radiation, STAT5 LOF mice displayed impaired crypt regeneration and developed more severe mucositis compared with controls. These data suggest that loss of STAT5 impairs IESC regenerative responses to small-intestinal injury, possibly by hindering the conversion from quiescent to active IESCs. In sharp contrast to STAT5 LOF, STAT5 activation repressed BMI1, LRIG1, and DCLK1 expression, and increased Lgr5 expression in mouse and human SCs. Inducible activation of STAT5 increased CBC activity to promote crypt regeneration, reducing radiation-induced mucosal injury. Interestingly, we found several putative STAT5 binding sites in the mouse Bmi1 and human BMI1 loci. ChIP analysis with Bmi1-specific primers demonstrated that hyperactivation of STAT5 increased STAT5 binding affinity at the Bmi1 locus. Accordingly, our data indicate that on the one hand, STAT5 signaling maintains IESC homeostatic proliferation, and on the other hand, activated STAT5 signaling gives rise to LGR5+ IESCs for injury-induced regeneration. These data suggest a model (Figure 7E) in which activated STAT5 signals promote IESC regeneration to reconstitute the impaired IECs, possibly by converting quiescent IESCs to active IESCs.

Intestinal secretory precursors can convert to IESCs upon irradiation injury to regain stemness (van Es et al., 2012). Interestingly, inhibition of CBC proliferation can induce premature differentiation of CBCs into Paneth cells (Lee et al., 2009). We found that depletion of Stat5 led to a reduction of LGR5+ IESCs coincidently with increased lysozyme+ Paneth cells in response to irradiation injury. Thus, these data suggest that STAT5 maintains IESC homeostasis in part by mediating secretory lineage differentiation, in addition to potential effects on quiescent IESCs. Furthermore, mucosal cytokine release could be critical for maintaining IESC homeostasis and response to gut injury (Farin et al., 2014). Our data demonstrate that activated STAT5 signaling increases IESC proliferation and regeneration to mitigate intestinal inflammation, possibly by affecting multiple intestinal compartments. In future studies, we will investigate which upstream cytokines of STAT5 are involved in the regulation of IESC responses to gut injury, and how to increase IESC survival by activating Stat5.

Taken together, our results demonstrate an essential role for STAT5 in the regulation of adult IESC homeostasis and response to intestinal injury and regeneration. Functionally, genetic activation of Stat5 increases IESC regeneration to replenish injured intestinal epithelia, conferring resistance to intestinal inflammation. Mechanistically, activated STAT5 could repress Bmi1 expression (a quiescent IESC marker). Overall, our work will be beneficial to obtain molecular insights into diseases driven by persistent enteric infection or inflammation.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

All chemicals and antibodies used in this work are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Animal Resources and Maintenance

The animal study protocol was approved by the CHRF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC2013-0051 1E03030, Han). All mouse lines used in this work are listed in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Radiation-Induced Injury Models and Animal Model of Colitis

The radiation-induced injury models and animal model of colitis are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Enteroid Culture and Differentiation

Ileal and jejunal crypts were isolated and IESCs were differentiated in vitro. Tam induction details are summarized in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Immunoblotting, IF, IH, In Situ Hybridization, and TUNEL Assay

Levels of LGR5, BMI1, LRIG1, DCLK1, Olfm4, Ascl2, and apoptosis were measured in the tissues and cultured cells. Details are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Flow Cytometry

IEC isolation, LGR5+ IESC, and EdU FACS analyses are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Laser Capture Microdissection

Details regarding laser capture microdissection are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

ChIP Assay and Real-Time qPCR

ChIP analyses are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

hESC Maintenance, Lentiviral Transduction of hESCs, and IEC Lines

pMSCV-STAT5a-ER∗ and pMSCV-icS5-ER∗ were cloned into lentiviral plasmids. The federally approved WA01 (H1) ESCs and Caco-2 cell differentiation are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as the mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and two-tailed Student's t test, the Mann-Whitney test (Prism; GraphPad) was used as appropriate, and p values ≤0.05 were considered significant.

Author Contributions

X.H., R.M., N.S., M.H., and C.M. conceived and designed the experiments. X.H., S.G., H.N., C.M., Y.L., T.N., J.V., W.T., and D.Z. performed the experiments. X.H., R.M., H.N., T.R., and M.M. generated transgenic mice. X.H., R.M., H.N., C.M., S.G., N.S., A.J., and M.H. analyzed the data. R.M., N.S., T.R., M.M., and M.H. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. X.H. and R.M. wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate Drs. James Wells, Mitchell Cohen, and Lee Denson at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) for supporting our research project. We thank Dr. Eilio Casanova at LBI-CR for Cancer for generating icS5 mice, and Dr. Yi Zheng’s laboratory for providing mouse lines. We also thank Dr. Maxime Mahe for providing technical support, and the CCHMC Pluripotent Stem Cell Facility for generating the lentivirus and assisting with hESC cultures. This work was supported by NIAID R21 (AI103388 to X.H.), CDMRP (PR121412 to X.H.), an AGA Elsevier Pilot Research Award (to X.H.), and CCHMC Research Innovation Funding (to X.H.) from CCHMC, and the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation Digestive Health Center (PHS grant P30 DK078392). R.M., H.N., M.M., and T.R. were supported by grant SFB F28 from the Austrian Science Funds (FWF). This work was completed in part in the NIH-funded Digestive Health Center and Laser Capture Microdissection Core at CCHMC.

Footnotes

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/).

Supplemental Information

References

- Barker N., van Es J.H., Kuipers J., Kujala P., van den Born M., Cozijnsen M., Haegebarth A., Korving J., Begthel H., Peters P.J., Clevers H. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beachy P.A., Karhadkar S.S., Berman D.M. Tissue repair and stem cell renewal in carcinogenesis. Nature. 2004;432:324–331. doi: 10.1038/nature03100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland C.R., Luciani M.G., Gasche C., Goel A. Infection, inflammation, and gastrointestinal cancer. Gut. 2005;54:1321–1331. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.060079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchon N., Broderick N.A., Chakrabarti S., Lemaitre B. Invasive and indigenous microbiota impact intestinal stem cell activity through multiple pathways in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2333–2344. doi: 10.1101/gad.1827009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczacki S.J., Zecchini H.I., Nicholson A.M., Russell R., Vermeulen L., Kemp R., Winton D.J. Intestinal label-retaining cells are secretory precursors expressing Lgr5. Nature. 2013;495:65–69. doi: 10.1038/nature11965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnier C., Stamataki D., Lewis J. Organizing cell renewal in the intestine: stem cells, signals and combinatorial control. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:349–359. doi: 10.1038/nrg1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farin H.F., Karthaus W.R., Kujala P., Rakhshandehroo M., Schwank G., Vries R.G., Kalkhoven E., Nieuwenhuis E.E., Clevers H. Paneth cell extrusion and release of antimicrobial products is directly controlled by immune cell-derived IFN-γ. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:1393–1405. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert S., Zhang R., Denson L., Moriggl R., Steinbrecher K., Shroyer N., Lin J., Han X. Enterocyte STAT5 promotes mucosal wound healing via suppression of myosin light chain kinase-mediated loss of barrier function and inflammation. EMBO Mol. Med. 2012;4:109–124. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grebien F., Kerenyi M.A., Kovacic B., Kolbe T., Becker V., Dolznig H., Pfeffer K., Klingmüller U., Müller M., Beug H. Stat5 activation enables erythropoiesis in the absence of EpoR and Jak2. Blood. 2008;111:4511–4522. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-102848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Benight N., Osuntokun B., Loesch K., Frank S.J., Denson L.A. Tumour necrosis factor alpha blockade induces an anti-inflammatory growth hormone signalling pathway in experimental colitis. Gut. 2007;56:73–81. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.094490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Gilbert S., Groschwitz K., Hogan S., Jurickova I., Trapnell B., Samson C., Gully J. Loss of GM-CSF signalling in non-haematopoietic cells increases NSAID ileal injury. Gut. 2010;59:1066–1078. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.203893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua G., Thin T.H., Feldman R., Haimovitz-Friedman A., Clevers H., Fuks Z., Kolesnick R. Crypt base columnar stem cells in small intestines of mice are radioresistant. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1266–1276. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.07.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Patel P.H., Kohlmaier A., Grenley M.O., McEwen D.G., Edgar B.A. Cytokine/Jak/Stat signaling mediates regeneration and homeostasis in the Drosophila midgut. Cell. 2009;137:1343–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju S., Mu J., Dokland T., Zhuang X., Wang Q., Jiang H., Xiang X., Deng Z.B., Wang B., Zhang L. Grape exosome-like nanoparticles induce intestinal stem cells and protect mice from DSS-induced colitis. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:1345–1357. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y., Iwama A., Tadokoro Y., Shimoda K., Minoguchi M., Akira S., Tanaka M., Miyajima A., Kitamura T., Nakauchi H. Selective activation of STAT5 unveils its role in stem cell self-renewal in normal and leukemic hematopoiesis. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:169–179. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.H., Escudero S., Shivdasani R.A. Intact function of Lgr5 receptor-expressing intestinal stem cells in the absence of Paneth cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:3932–3937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113890109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyba M., Perlingeiro R.C., Hoover R.R., Lu C.W., Pierce J., Daley G.Q. Enhanced hematopoietic differentiation of embryonic stem cells conditionally expressing Stat5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100(Suppl 1):11904–11910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1734140100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G., White L.S., Hurov K.E., Stappenbeck T.S., Piwnica-Worms H. Response of small intestinal epithelial cells to acute disruption of cell division through CDC25 deletion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:4701–4706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900751106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Clevers H. Coexistence of quiescent and active adult stem cells in mammals. Science. 2010;327:542–545. doi: 10.1126/science.1180794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Bohin N., Wen T., Ng V., Magee J., Chen S.C., Shannon K., Morrison S.J. Oncogenic Nras has bimodal effects on stem cells that sustainably increase competitiveness. Nature. 2013;504:143–147. doi: 10.1038/nature12830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G., Xu N., Xi R. Paracrine unpaired signaling through the JAK/STAT pathway controls self-renewal and lineage differentiation of Drosophila intestinal stem cells. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;2:37–49. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjp028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlos-Suárez A., Barriga F.M., Jung P., Iglesias M., Céspedes M.V., Rossell D., Sevillano M., Hernando-Momblona X., da Silva-Diz V., Muñoz P. The intestinal stem cell signature identifies colorectal cancer stem cells and predicts disease relapse. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:511–524. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe C., Kljavin N.M., Ybarra R., de Sauvage F.J. Lgr5+ stem cells are indispensable for radiation-induced intestinal regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery R.K., Carlone D.L., Richmond C.A., Farilla L., Kranendonk M.E., Henderson D.E., Baffour-Awuah N.Y., Ambruzs D.M., Fogli L.K., Algra S., Breault D.T. Mouse telomerase reverse transcriptase (mTert) expression marks slowly cycling intestinal stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:179–184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013004108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muyrers J.P., Zhang Y., Testa G., Stewart A.F. Rapid modification of bacterial artificial chromosomes by ET-recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1555–1557. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.6.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira B., Sousa S., Barros R., Carreto L., Oliveira P., Oliveira C., Chartier N.T., Plateroti M., Rouault J.P., Freund J.N. CDX2 regulation by the RNA-binding protein MEX3A: impact on intestinal differentiation and stemness. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:3986–3999. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potten C.S. Radiation, the ideal cytotoxic agent for studying the cell biology of tissues such as the small intestine. Radiat. Res. 2004;161:123–136. doi: 10.1667/rr3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell A.E., Wang Y., Li Y., Poulin E.J., Means A.L., Washington M.K., Higginbotham J.N., Juchheim A., Prasad N., Levy S.E. The pan-ErbB negative regulator Lrig1 is an intestinal stem cell marker that functions as a tumor suppressor. Cell. 2012;149:146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangiorgi E., Capecchi M.R. Bmi1 is expressed in vivo in intestinal stem cells. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:915–920. doi: 10.1038/ng.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine R.R., Matunis E.L. JAK-STAT signaling in stem cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2013;786:247–267. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-6621-1_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda N., Jain R., LeBoeuf M.R., Wang Q., Lu M.M., Epstein J.A. Interconversion between intestinal stem cell populations in distinct niches. Science. 2011;334:1420–1424. doi: 10.1126/science.1213214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H., Biehs B., Warming S., Leong K.G., Rangell L., Klein O.D., de Sauvage F.J. A reserve stem cell population in small intestine renders Lgr5-positive cells dispensable. Nature. 2011;478:255–259. doi: 10.1038/nature10408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vafaizadeh V., Klemmt P., Brendel C., Weber K., Doebele C., Britt K., Grez M., Fehse B., Desriviéres S., Groner B. Mammary epithelial reconstitution with gene-modified stem cells assigns roles to Stat5 in luminal alveolar cell fate decisions, differentiation, involution, and mammary tumor formation. Stem Cells. 2010;28:928–938. doi: 10.1002/stem.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Es J.H., Sato T., van de Wetering M., Lyubimova A., Nee A.N., Gregorieff A., Sasaki N., Zeinstra L., van den Born M., Korving J. Dll1+ secretory progenitor cells revert to stem cells upon crypt damage. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:1099–1104. doi: 10.1038/ncb2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Landeghem L., Santoro M.A., Krebs A.E., Mah A.T., Dehmer J.J., Gracz A.D., Scull B.P., McNaughton K., Magness S.T., Lund P.K. Activation of two distinct Sox9-EGFP-expressing intestinal stem cell populations during crypt regeneration after irradiation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G1111–G1132. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00519.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Li G., Tse W., Bunting K.D. Conditional deletion of STAT5 in adult mouse hematopoietic stem cells causes loss of quiescence and permits efficient nonablative stem cell replacement. Blood. 2009;113:4856–4865. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-181107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphalen C.B., Asfaha S., Hayakawa Y., Takemoto Y., Lukin D.J., Nuber A.H., Brandtner A., Setlik W., Remotti H., Muley A. Long-lived intestinal tuft cells serve as colon cancer-initiating cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:1283–1295. doi: 10.1172/JCI73434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierenga A.T., Vellenga E., Schuringa J.J. Maximal STAT5-induced proliferation and self-renewal at intermediate STAT5 activity levels. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;28:6668–6680. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01025-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan K.S., Chia L.A., Li X., Ootani A., Su J., Lee J.Y., Su N., Luo Y., Heilshorn S.C., Amieva M.R. The intestinal stem cell markers Bmi1 and Lgr5 identify two functionally distinct populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:466–471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118857109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yui S., Nakamura T., Sato T., Nemoto Y., Mizutani T., Zheng X., Ichinose S., Nagaishi T., Okamoto R., Tsuchiya K. Functional engraftment of colon epithelium expanded in vitro from a single adult Lgr5(+) stem cell. Nat. Med. 2012;18:618–623. doi: 10.1038/nm.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Yantiss R.K., Nam H.S., Chin Y., Zhou X.K., Scherl E.J., Bosworth B.P., Subbaramaiah K., Dannenberg A.J., Benezra R. ID1 is a functional marker for intestinal stem and progenitor cells required for normal response to injury. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;3:716–724. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.