Abstract

Objective

Smokers with depressive symptoms have more difficulty quitting smoking than the general population of smokers. The present study examines a web-based treatment using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for smokers with depressive symptoms. The study aimed to determine participant receptivity to the intervention and its effects on smoking cessation, acceptance of internal cues, and depressive symptoms.

Methods

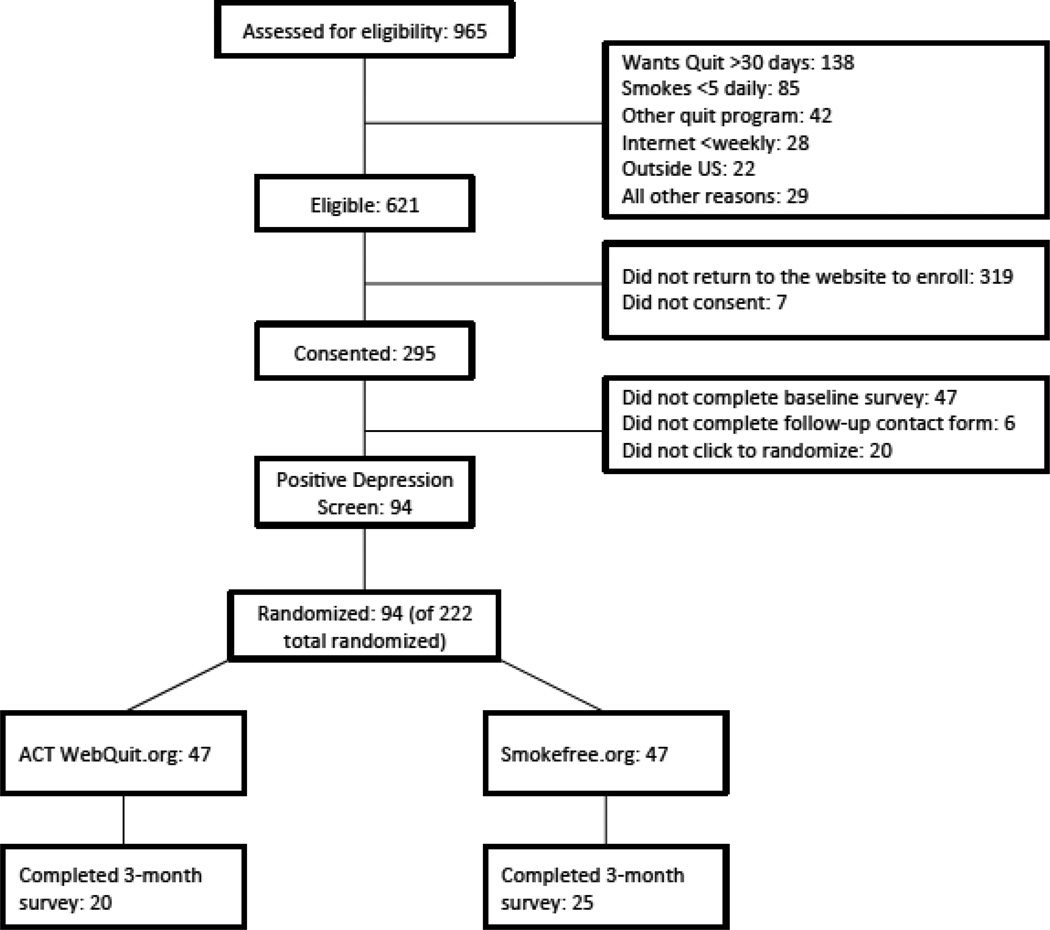

Smokers who screened positive for depressive symptoms at baseline (n = 94) were selected from a randomized controlled trial (N = 222) comparing web-based ACT for smoking cessation (Webquit.org) with Smokefree.gov. Forty-five participants (48%) completed the three-month follow-up.

Results

Compared to Smokefree.gov, WebQuit participants spent significantly more time on site (p = 0.001) and had higher acceptance of physical cravings (p = 0.033). While not significant, WebQuit participants were more engaged and satisfied with their program and were more accepting of internal cues overall. There was preliminary evidence that WebQuit participants had higher quit rates (20% vs. 12%) and lower depressive symptoms at follow-up (45% vs. 56%) than those in Smokefree.gov.

Conclusions

This was the first study of web-based ACT for smoking cessation among smokers with depressive symptoms, with promising evidence of receptivity, efficacy, impact on a theory-based change process, and possible secondary effects on depression. A fully powered trial of the ACT Webquit.org intervention specifically for depressed smokers is needed. This was part of a clinical trial registered as NCT#01166334, at www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Keywords: smoking cessation, web-based treatment, symptom of depression, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Cigarette smoking is the primary cause of preventable death in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). Smokers with symptoms of depression are particularly at-risk for smoking-related morbidity and mortality for a number of reasons (e.g., Brown, Lejuez, Kahler, Strong & Zvolensky, 2005). First, smokers with symptoms of depression are heavier, more dependent on nicotine (Pratt & Brody, 2010). Second, they make fewer quit attempts (McClave, Dube, Strine, Kroenke, Caraballo & Mokdad, 2009), and when they do attempt to quit, they are 40% less likely to succeed than smokers with no depressive symptoms (Anda, Williamson, Escobedo, Mast, Giovino & Remington, 1990).

Several lines of evidence suggest that a major challenge to cessation among smokers with depressive symptoms is the greater salience of internal cues to smoke. Smokers with depressive symptoms report higher levels of nicotine withdrawal, including craving, irritability, and restlessness (e.g., Kinnunen, Doherty, Militello & Garvey, 1996; Sonne, Nunes, Jiang, Tyson, Rotrosen & Reid, 2010), and are prone to experiencing heightened negative affect during a quit attempt (Carmody, Vieten & Astin, 2007). Negative affect, in turn, is a robust predictor of relapse to smoking following a cessation attempt (Anda et al., 1990).

Given the key role of internal cues for smokers with depressive symptoms, smoking cessation treatments that help people learn new ways to cope with their internal cues hold great promise (Brown et al., 2005). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is an intervention that proposes a novel mechanism of behavior change: helping individuals accept aversive and disturbing internal events while committing to actions that are supported by their values (Hayes, Strosahl & Wilson, 1999). In contrast with standard smoking cessation approaches (e.g., traditional cognitive behavioral therapy), ACT focuses on changing the relationship between the internal cues and the smoking behavior (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006) rather than on changing the internal cues themselves. Several studies have provided preliminary evidence of ACT’s potential as a novel treatment for smoking cessation (Bricker, Mann, Marek, Liu & Peterson, 2010; Gifford et al., 2004; Hernandez-Lopez, Luciano, Bricker, Roales-Nieto & Montesinos, 2009).

Our group recently completed the first trial of web-based ACT for smoking cessation (Bricker, Wyszynski, Comstock, & Heffner, 2013). In this double-blind randomized controlled pilot trial, we compared web-based ACT for smoking cessation (Webquit.org) with the National Cancer Institute’s Smokefree.gov web site in a general population sample of smokers. We found that the quit rate for Webquit.org was double that of Smokefree.gov (23% vs. 10%, p=.05; Bricker et al., 2013). These preliminary results were promising and motivated examining the effects of this intervention on the sub-population of smokers with symptoms of depression. Few studies to date have examined outcomes of web-based smoking cessation treatment for smokers with symptoms of depression. Results of a series of studies by Muñoz and colleagues showed very limited success of a web-delivered intervention for currently depressed smokers, with quit rates ranging from 0% to 4% in three out of the four studies reported (Muñoz, Lenert, Delucchi, Stoddard, Perez, 2006).

In order to determine whether web-based ACT benefits smokers with depressive symptoms, we conducted a post hoc analysis of data from our randomized, controlled trial of web-based ACT, focusing on the subset of smokers with depressive symptoms (n=94). Since ACT is well-suited to address the unique challenges of quitting among smokers with depressive symptoms (i.e., more salient internal cues, such as greater negative affect and craving), we explored whether ACT participants would be: (1) more receptive to the intervention, (2) more likely to quit smoking, (3) more accepting of internal cures to smoke, and (4) at a lower likelihood of continuing to experience depressive symptoms at the three-month follow-up.

METHODS

Participants

Study participants were recruited via traditional media (radio and television), web-based media, paid Internet advertising, social networking sites, and emails to healthcare organizations and employers. Participants met the following eligibility criteria: (1) age 18 or older, (2) smokes 5 or more cigarettes/day for the past 12 months, (3) intends to quit in the next 30 days, (4) willing to be randomized, (5) resides in the U.S., (6) has access to high speed internet, (7) willing and able to read English, (8) not participating in other smoking cessation interventions, and (9) has never used the Smokefree.gov website.

A total of 222 eligible respondents were assigned to one of two treatment conditions using stratified randomization based on key variables known to predict smoking cessation: (1) gender (Hughes & Kalman, 2006) and (2) presence of current depression symptoms (McClave et al., 2009). The current study includes only the subset of randomized participants who screened positive for depression at baseline (n=94). Participants received $10 in compensation for completing study assessments.

All elements of the study were explained to study participants, and written informed consent was obtained following an opportunity for questions and discussion. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Interventions

WebQuit.org was presented as a self-paced program consisting of eight ACT modules. Webquit.org contained no interventions specifically targeting depressive symptoms and their relationship to quitting, as it was designed as an intervention for the general population of smokers. A complete description of the WebQuit.org intervention can be found elsewhere (Bricker et al., 2013). Smokefree.gov is also a self-paced program, with content based on the current standard of care for behavioral smoking cessation interventions--the U.S. Clinical Practice Guidelines (Fiore et al., 2008).

Measures

Demographics and smoking

Self-reported demographics, smoking history, and current smoking behaviors were assessed in the baseline survey.

Anxiety and Depression Detector (Means-Christensen, Sherbourne, Roy-Byrne, Craske & Stein, 2006)

Depressive symptoms were screened with the following question: “In the past three months, did you have a period of one week or more when you lost interest in most things like work, hobbies and other things you usually enjoyed?” (yes/no). The screener was administered at baseline and at three-month follow-up. This scale has shown good sensitivity (.85) and specificity (.73) as a screening device for depressive disorders.

Satisfaction

Treatment satisfaction was measured with a brief survey at the three-month follow-up. A sample item was: “Overall, how satisfied were you with your assigned website?” Response choices ranged from “Not at all” (1) to “Very much” (5).

Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale (AIS-27; adapted from Gifford et al., 2004)

The AIS is a 27-item adaptation of the Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale that measures ACT theory-based acceptance processes. It was administered at baseline and at three-month follow-up. The AIS-27 has three subscales: willingness to experience (a) physical sensations (9 items), (b) cognitions (9 items), and (c) emotions (9 items) that cue smoking. Response choices for each item range from “Not at all” (1) to “Very willing” (5). Construct and predictive validity of the modified AIS have been established in our prior work (Bricker et al., 2013). Scores for each of the three subscales, as well as a total score combining all three subscales (Cronbach’s α = 0.87 at baseline and 0.97 at follow-up), were derived by averaging their respective items.

Thirty-day point prevalence cessation outcome

This outcome was measured at three-month follow-up via consistent responses to the following two items: (1) “When was the last time you smoked, or even tried, a cigarette?” Response choices ranged from “Earlier today” to “Over 31 days ago” and (2) “Have you smoked cigarettes at all, even a puff, in the last 30 days?” Response choices were “Yes” or “No.”

Data Analysis

Demographic characteristics and baseline smoking were assessed for balance between study groups (see Table 1). Logistic regression models examined whether baseline factors predicted three-month retention. AIS scores were compared between study groups using two-sample t-tests, and logistic regression was used to compare smoking cessation outcomes. A similar model compared satisfaction between the two assigned study websites. These models adjusted for participation in other treatments, which was the only variable that differed between groups. Consistent with the methods of handling missing smoking outcome data in the larger study (Bricker et al., 2013), complete case analysis was used for the primary outcome. Statistical significance was set at .05. Analyses were performed using Stata software (Stata version 11.0 for Mac, College Station, TX).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and their Prediction of Outcome Data Retention of Trial Participants Randomized to each Arm for Smokers with Depressive Symptoms (N = 94)

|

WebQuit.org(ACT) (n=47) |

Smokefree.gov (Control) (n=47) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | p-value* | |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age | 43.6 (14.5) | 43.2 (12.2) | 0.90 | ||

| Male | 23 (49%) | 20 (43%) | 0.68 | ||

| Caucasian | 46 (98%) | 41 (87%) | 0.06 | ||

| Hispanic | 2 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 0.99 | ||

| Married | 18 (38%) | 17 (36%) | 0.91 | ||

| Working | 30 (64%) | 29 (62%) | 0.99 | ||

| HS or less education | 13 (28%) | 14 (30%) | 0.49 | ||

| Smoking Behavior | |||||

| Nicotine Dependence | 20 (43%) | 22 (47%) | 0.84 | ||

| Smokes more than half pack per day | 35 (74%) | 37 (79%) | 0.94 | ||

| Smoked for 10 or more years | 36 (77%) | 36 (77%) | 0.99 | ||

| Quit attempts in past 12mos | 1.5 (2.8) | 1.3 (2.0) | 0.75 | ||

| Commitment to quitting | 4.0 (0.9) | 4.2 (0.7) | 0.25 | ||

| Friend & Partner Smoking | |||||

| Close friends who smoke | 1.8 (1.6) | 1.7 (1.7) | 0.76 | ||

| Living with partner who smokes | 7 (15%) | 10 (21%) | 0.92 | ||

| ACT Theory-Based Acceptance | |||||

| Acceptance of physical triggers | 2.64 (0.81) | 2.73 (0.81) | 0.60 | ||

| Acceptance of emotional triggers | 2.38 (0.58) | 2.40 (0.53) | 0.87 | ||

| Acceptance of cognitive triggers | 2.03 (0.58) | 2.02 (0.62) | 0.94 | ||

| Acceptance total score | 2.42 (0.58) | 2.45 (0.53) | 0.78 | ||

Note: ACT=Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.

P-values compare baseline variables between the WebQuit.org ACT and Smokefree.gov arms. The p-values were generated from two-sample t-tests for continuous variables and Fisher's exact test for categorical variables.

RESULTS

As can be seen in Table 1, 43 participants were male (46%), 87 were Caucasian (93%), 4 were Hispanic (9%), 35 were married (37%), and 59 were working (63%). Almost half were dependent on nicotine (n = 42, 45%), 72 (77%) smoked more than half a pack of cigarettes per day and 72 (77%) had smoked for 10 years or longer. Table 1 also shows that demographic and smoking variables were balanced at baseline across the two treatment arms (all p > .05). Forty-five participants (48%) completed the three-month follow-up assessment. None of the baseline characteristics predicted follow-up data retention status (all p-values > .05).

Participant Receptivity: Utilization and Satisfaction

Table 2 shows that WebQuit.org participants remained on the site for a significantly greater number of minutes per login than Smokefree.gov participants (21.7 vs. 9.4; p = .001). While not statistically significant, two trends were seen that were in line with study hypotheses. WebQuit.org participants reported greater satisfaction with their assigned website (75% vs. 52%; p = .15) and greater agreement that their assigned program was a good fit for them (60% vs. 38%; p = .15)

Table 2.

Comparison of Webquit.org and Smokefree.gov on Receptivity to Assigned Website, 30-day Quit Rate, and ACT Theory-Based Process of Change (nI = 45)

| Receptivity Measures | WebQuit.org | Smokefree.gov | p-value1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Utilization of assigned website | n | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | |

| Length of each login, in minutes | 21 | 21.7 (13.8) | 18 | 9.4 (7.1) | 0.001 |

| Times logged in | 19 | 7.9 (5.8) | 21 | 5.7 (6.1) | 0.14 |

| Satisfaction with assigned website, | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Satisfied overall2 | 20 | 15 (75 %) | 21 | 11 (52 %) | 0.15 |

| Recommend to friend | 21 | 13 (62 %) | 21 | 14 (67 %) | 0.74 |

| Overall approach for quitting a good fit2 | 20 | 12 (60 %) | 21 | 8 (38 %) | 0.15 |

| Utility of program’s quit plan2 | 21 | 9 (43 %) | 22 | 6 (27 %) | 0.28 |

| Cessation Outcome | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| 30-day quit status at 3-month follow-up | 20 | 4 (20%) | 25 | 3 (12%) | 0.42 |

| ACT Theory-Based Process of Change | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Acceptance of physical triggers | 20 | 3.30 (1.01) | 25 | 2.69 (0.75) | 0.033 |

| Acceptance of emotional triggers | 20 | 2.97 (0.81) | 25 | 2.69 (0.75) | 0.131 |

| Acceptance of cognitive triggers | 20 | 2.70 (1.13) | 25 | 2.57 (0.82) | 0.672 |

| Acceptance total score | 20 | 3.03 (0.88) | 25 | 2.64 (0.57) | 0.104 |

Note: ACT=Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.

Two-sided p values calculated from logistic regression models adjusted for participation in other quit programs (n=3 in Smokefree.gov, n=2 in Webquit.org [ACT]). Participants in other quit programs had four times higher odds (OR = 4.67; p =0.135) of not smoking in the last 30 days. Unadjusted two-sided p values were very similar.

Responses dichotomized as “Somewhat” or “Very Much” vs. “Not at all” or “A little.”

Smoking Cessation at Three-Month Follow-up: 30-day Point Prevalence Quit Rates

Although the difference was not statistically significant and must be viewed with caution, descriptive evidence suggests that participants in the WebQuit.org group were somewhat more successful in quitting than Smokefree.gov participants. Results showed that 20% (4/20) of the participants in the WebQuit.org (ACT) arm quit smoking, as compared to 12% (3/25) in the Smokefree.gov arm (p = .42).

Acceptance Processes of ACT’s Effects on Smoking

At three-month follow-up, WebQuit.org participants were significantly more willing to experience physical triggers than Smokefree.gov participants (p = .033). Again, while not statistically significant, there was a trend showing that WebQuit.org participants were somewhat more willing to experience emotional triggers (p = .13) and had somewhat higher total scores for acceptance than those in the Smokefree.gov arm (p = .104).

Presence of Depressive Symptoms at Three-Month Follow-up and Relationship to Quitting

A lower percentage of WebQuit.org participants (45%; 9/20) than Smokefree.gov participants (56%; 14/25) screened positive for depression at three-month follow-up, however this did not approach statistical significance (p = .66). Although the sample size was inadequate to conduct formal tests of mediation, we also examined whether change in depressive symptoms (defined as screening negative for depressive symptoms at the three-month follow-up) was correlated with 30-day point prevalence abstinence at three months. The quit rate at follow-up for smokers who remained positive for depression was not significantly different than that for smokers who no longer remained positive for depression; 22% (5/23) versus 9% (2/22), p = .41. This finding must be considered with caution given the high p value.

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to preliminarily evaluate whether an innovative web-based intervention for smoking cessation based on ACT might potentially benefit smokers with depressive symptoms as compared to a standard of care smoking cessation website (Smokefree.gov) on measures of participant satisfaction, efficacy, impact on ACT’s theory-based process of change (i.e., acceptance of internal cues to smoke), and persistence of depressive symptoms at follow-up.

Compared to Smokefree.gov, WebQuit.org participants were significantly more engaged with their assigned program, and their treatment had a significant impact on ACT’s theory-based mechanism of change: acceptance of cravings. Although not statistically significant, we observed several trends. WebQuit.org participants reported being more satisfied with their program, felt that the program was a good fit for them, and showed increases in acceptance of emotional triggers as well as overall acceptance of internal smoking cues. While certainly not approaching a trend toward significance, we observed changes in two clinically important outcomes: higher quit rates (20% in ACT vs. 12% in Smokefree.gov) and lower prevalence of depressive symptoms (45% in ACT vs 56% in Smokefree.gov) at three-month follow-up in ACT as compared to Smokefree.gov. Notably, smokers who were no longer depressed at follow-up were descriptively (although not significantly) less likely to quit smoking, so it does not appear on the basis of these preliminary analyses that ACT facilitates cessation in depressed smokers by reducing depressive symptoms. This finding is consistent with ACT’s theory-based mechanism of change, which emphasizes increasing willingness to experience uncomfortable physical and psychological states in order to make meaningful changes rather than attempting to alter these states directly (Hayes et al., 2006). Thus, ACT may facilitate cessation in smokers with depressive symptoms by breaking the link between depressed mood and quitting rather than by changing mood directly.

This study suggests that ACT has considerable potential as a treatment for smokers with elevated levels of depression at the time of a quit attempt. ACT’s effect size in this subsample of smokers with depressive symptoms was very similar to that of the parent study, which enrolled a general population sample of smokers. The finding that intervention effects were upheld in a group of smokers at risk for worse smoking cessation outcomes (Anda et al., 1990) is noteworthy, adding further preliminary support for the intervention’s potential.

In addition to low statistical power that prevents definitive conclusions, this study has key limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, depressive symptoms were measured with a one-item screener. Although the screener is highly correlated with the results of expert diagnostic interview, it tends to overestimate the prevalence of depressive symptoms (Means-Christensen et al., 2006), and we did not assess the full diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode. Second, rates of follow-up data retention in the study were modest (48%). While this figure is consistent with other published rates of retention in web-based treatment studies (Berg, 2011; Civljak, Sheikh, Stead & Car, 2010), this level of retention cautions the interpretation of the observed quit rates in each arm. Third, we relied exclusively on self-reported abstinence in our estimate of 30-day point prevalence abstinence. However, expert consensus (SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification, 2002) suggests that biochemical verification of abstinence is impractical and unnecessary in population-based studies that do not involve in-person contact. Moreover, there is no reason to believe that the validity of self-reported abstinence would differ by treatment group.

This study was the first to preliminarily evaluate a web-based ACT intervention for smoking cessation among smokers with depressive symptoms, with promising early evidence of receptivity, efficacy, and impact on a theory-based change process. We also found possible secondary effects on depression, although these were very preliminary findings that should be replicated in a larger sample using a more comprehensive evaluation of depressive symptoms with demonstrated sensitivity for detecting treatment-related change. These results are noteworthy because WebQuit.org does not contain any elements focusing on depression. Thus, it is conceivable that the results could be stronger if WebQuit.org was adapted for depressed smokers. A fully powered trial of the ACT Webquit.org intervention tailored specifically to depressed smokers could be a promising strategy in helping these smokers to quit.

Figure 1.

Participant Flow Diagram

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the volunteer study participants. The authors also thank Leela Holman for editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript and Madelon Bolling PhD for conceptual input on the study design.

FUNDING

This study was funded by a grant from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. The writing of this manuscript was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (K23DA026517 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse to JLH, T32MH082709 from the National Institute of Mental Health to RV, and R01CA166646 and R01CA151251 from the National Cancer Institute to JBB.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Contributor Information

Helen A. Jones, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Division of Public Health Sciences, 1100 Fairview Ave N., PO Box 19024, Mail Stop M3-B232, Seattle, WA 98109, U.S.A.; Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Box 358080, Seattle, WA 98195, U.S.A.; joneshelen11@gmail.com

Jaimee L. Heffner, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Division of Public Health Sciences, 1100 Fairview Ave N., PO Box 19024, Mail Stop M3-B232, Seattle, WA 98109, U.S.A.; jheffner@fhcrc.org

Laina Mercer, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Division of Public Health Sciences, 1100 Fairview Ave N., PO Box 19024, Mail Stop M3-B232, Seattle, WA 98109, U.S.A.; Department of Statistic, University of Washington, Box 354322, Seattle, WA 98195-4322, U.S.A.; mercel@uw.edu

Christopher M. Wyszynski, Department of Psychology, Rutgers University, Busch Campus, Department of Psychology, 152 Frelinghuysen Road, Piscataway, NJ 08873, U.S.A.; Christopher.w@rutgers.edu

Roger Vilardaga, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Division of Public Health Sciences, 1100 Fairview Ave N., PO Box 19024, Mail Stop M3-B232, Seattle, WA 98109, U.S.A.; Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington, Box 359911, 325 Ninth Ave, Seattle, WA 98104-2499, U.S.A.; vilardag@uw.edu

Jonathan B. Bricker, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Division of Public Health Sciences, 1100 Fairview Ave N., PO Box 19024, Mail Stop M3-B232, Seattle, WA 98109, U.S.A.; Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Box 358080, Seattle, WA 98195, U.S.A.; jbricker@fhcrc.org

REFERENCES

- Anda RF, Williamson DF, Escobedo LG, Mast EE, Giovino GA, Remington PL. Depression and the dynamics of smoking: A national perspective. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264(12):1541–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ. Internet-based interventions for smoking cessation show inconsistent effects across trials, with only some trials showing a benefit. Evidence-Based Nursing. 2011;14(2):47–48. doi: 10.1136/ebn.14.2.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Mann SL, Marek PM, Liu J, Peterson AV. Telephone-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy for adult smoking cessation: A feasibility study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12(4):454–458. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Wyszynski C, Comstock B, Heffner JL. Pilot randomized trial of the first web-based Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for smoking cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15(10):1756–1764. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Zvolensky MJ. Distress tolerance and early smoking lapse. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:713–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody TP, Vieten C, Astin JA. Negative affect, emotional acceptance, and smoking cessation. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39(4):499–508. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: Current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years --- United States, 2005--2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2011;60:1207–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civljak M, Sheikh A, Stead LF, Car J. Internet-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;(9):CD007078. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007078.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ, Wewers ME. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford EV, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Antonuccio DO, Piasecki MM, Rasmussen-Hall ML, Palm KM. Acceptance-based treatment for smoking cessation. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:689–705. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;55:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An experimental approach to behavior change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Lopez M, Luciano MC, Bricker JB, Roales-Nieto JG, Montesinos F. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for smoking cessation: A preliminary study of its effectiveness in comparison with cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(4):723–730. doi: 10.1037/a0017632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Kalman D. Do smokers with alcohol problems have more difficulty quitting? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;82(2):91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnunen T, Doherty K, Militello FS, Garvey AJ. Depression and smoking cessation: Characteristics of depressed smokers and effects of nicotine replacement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(4):791–798. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClave AK, Dube SR, Strine TW, Kroenke K, Caraballo RS, Mokdad AH. Associations between smoking cessation and anxiety and depression among U.S. adults. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Means-Christensen AJ, Sherbourne CD, Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Stein MB. Using five questions to screen for five common mental disorders in primary care: Diagnostic accuracy of the Anxiety and Depression Detector. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2006;28(2):108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz RF, Lenert LL, Delucchi K, Stoddard J, Perez JE, Penilla C, Pérez-Stable EJ. Toward evidence-based Internet interventions: A Spanish/English Web site for international smoking cessation trials. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006;8(1):77–87. doi: 10.1080/14622200500431940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt LA, Brody DJ. Depression and smoking in the U.S. household population aged 20 and over, 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2010;34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonne SC, Nunes EV, Jiang H, Tyson C, Rotrosen J, Reid MS. The relationship between depression and smoking cessation outcomes in treatment-seeking substance abusers. The American Journal on Addictions. 2010;19(2):111–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2009.00015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2002;4(2):149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]