Abstract

Functional mature cells are continually replenished by stem cells to maintain tissue homoeostasis. In the adult Drosophila posterior midgut, both terminally differentiated enterocyte (EC) and enteroendocrine (EE) cells are generated from an intestinal stem cell (ISC). However, it is not clear how the two differentiated cells are generated from the ISC. In this study, we found that only ECs are generated through the Su(H)GBE+ immature progenitor enteroblasts (EBs), whereas EEs are generated from ISCs through a distinct progenitor pre-EE by a novel lineage-tracing system. EEs can be generated from ISCs in three ways: an ISC becoming an EE, an ISC becoming a new ISC and an EE through asymmetric division, or an ISC becoming two EEs through symmetric division. We further identified that the transcriptional factor Prospero (Pros) regulates ISC commitment to EEs. Our data provide direct evidence that different differentiated cells are generated by different modes of stem cell lineage specification within the same tissues.

Keywords: Intestinal stem cell, Secretory enteroendocrine cell, Pre-enteroendocrine cell, Prospero, Drosophila

Summary: The generation of enteroendocrine cells from stem cells in the adult Drosophila midgut occurs via a distinct progenitor stage and involves the transcription factor Prospero.

INTRODUCTION

Adult stem cells maintain tissue homeostasis by continuously replenishing damaged, aged and dead cells in any organism (Weissman, 2000). As expected, adult stem cell self-renewal and differentiation are tightly regulated processes, and an imbalance in adult stem cell homeostasis can result in complications such as tumor formation and degenerative diseases. Moreover, adult stem cell behavior must be precisely regulated to ensure a prompt response to tissue damage and stress.

The Drosophila midgut is one of its largest organs, and it serves as the entry site not only for nutrients like food and water, but also for pathogens, such as harmful bacteria, viruses and toxins (Hakim et al., 2010). As a result, the midgut epithelium is constantly exposed to environmental assault and undergoes rapid turnover. The integrity of the epithelium is maintained by replenishing lost cells with intestinal stem cells (ISCs) (Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006; Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006). These ISCs lie adjacent to the basement membrane and divide approximately once a day to give rise to either absorptive enterocytes (ECs) or secretory enteroendocrine (EE) cells. Because of the simple cell lineage, ease of performing genetic analysis and availability of abundant mutants, the Drosophila midgut has served as a powerful model system for studying adult stem cell-mediated tissue homeostasis and regeneration.

Previous studies suggest that an ISC divides asymmetrically to produce one new ISC (self-renewal) and one immature daughter cell, an enteroblast (EB), which further differentiates into an EC or an EE cell (Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006; Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006). Notch (N) signaling plays a major role in regulating ISC self-renewal and differentiation (Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006; Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006, 2007). The ligand of the N pathway, Delta (Dl), is specifically expressed on an ISC and unidirectionally switches on the N-signaling pathway in the neighboring EB to promote the differentiation of an EB to an EC and to inhibit the differentiation of an EB to an EE (Bardin et al., 2010; Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006; Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006, 2007). In addition, commitment and terminal differentiation of ISCs require distinct levels of N activity; commitment requires high activity and terminal differentiation requires low activity (Perdigoto et al., 2011). Furthermore, the overexpression of Dl in ISCs does not affect ISC proliferation, but promotes EC fate at the expense of EE cells, suggesting that N signaling is not only necessary, but also sufficient, for specifying EC cell fate (Beebe et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2009).

The differentiated ECs can also regulate ISCs through a feedback mechanism to maintain tissue homeostasis (Biteau et al., 2011; Jiang and Edgar, 2011). Cells in the intestine are constantly exposed to numerous insults, from tissue damage to bacterial infection. It was reported that these events initially affect differentiated ECs, causing either ablation or activated JNK-mediated stress signaling in the ECs (Jiang and Edgar, 2011). The affected ECs would upregulate unpaired (Upd) ligands (Upd2 and Upd3) of the JAK-STAT signal transduction pathway, which would activate the JAK-STAT signal transduction pathway in ISCs. This activation would induce ISC division and differentiation to generate new ECs that would replenish the damaged epithelium.

Compared with the extent of knowledge on EC specification and regulation, relatively little is known about EE cell fate specification and regulation. In this study, we performed lineage-tracing experiments using a newly developed tracing system and found that EE was generated from ISCs through a distinct progenitor. We further found that Prospero (Pros) functions downstream of or parallel to the achaete-scute complex (AS-C) members to determine ISC commitment to EE.

RESULTS

Su(H)GBE+ EBs are progenitors of ECs but not EEs

Different cell types in the adult Drosophila posterior midgut can be identified morphologically as well as by their expression of different markers. ISCs are diploid, have a small nucleus, and express Dl and Sanpodo (Spdo). EBs are diploid and have a small nucleus; Su(H)GBE-lacZ, a transcriptional reporter of N signaling, was found to be highly expressed in the daughter cell (EB). ECs are polyploid, have a large nucleus and express the transcriptional factor Pdm-1. EEs are diploid, have a small nucleus, and express the transcription factor Pros and synaptic protein Bruchpilot (Brp/nc82) (Jiang et al., 2009; Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006; Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006, 2007; Perdigoto et al., 2011; Zeng et al., 2013). However, it is not clear whether all ISCs are Dl positive (Dl+), whether all EBs are Su(H)GBE+, whether all ECs are Pdm-1+ and whether all EEs are Pros+. In this study, we only examined Dl+ ISCs, Su(H)GBE+ EBs, Pdm-1+ ECs and Pros+ EEs.

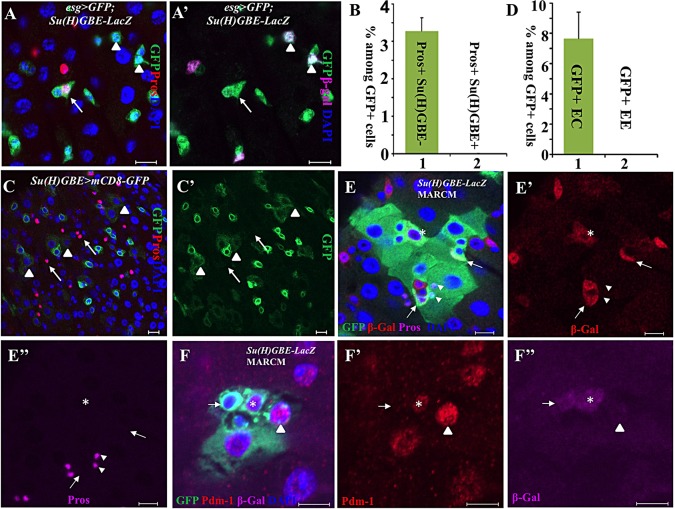

Both ISCs and EBs in the midgut express the transcriptional factor escargot (Esg) (Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006). Esg-Gal4 is widely used to manipulate gene expression in ISCs and EBs of the posterior midgut. During a routine staining of esg-Gal4, UAS-GFP midguts with the Pros antibody, we unexpectedly found that 3.3% of Esg+ diploid cells express the EE marker Pros (n=45 guts; Fig. 1A,B). Interestingly, these Esg+ Pros+ cells do not express the EB marker Su(H)GBE-lacZ (n=45 guts; Fig. 1A′,B). These Esg+ Su(H)GBE− Pros+ cells may be EE progenitors (or pre-EEs). We reasoned that some of the newly generated ECs and EEs might inherit weak green fluorescent protein (GFP) from Su(H)GBE-Gal4,UAS-mCD8-GFP-labeled EBs if they were developed from EBs. Indeed, we found that, among all GFP+ cells, 7.6% (32/472, n=12; Fig. 1C-D) of the cells are ECs that express weak GFP inherited from Su(H)GBE+ EBs; but surprisingly, we did not find any EEs that have inherited GFP from Su(H)GBE+ EBs (0/472, n=12; Fig. 1C-D). We further examined cell fate identification using the mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) technique (Lee and Luo, 1999). In wild-type MARCM clones with Su(H)GBE-lacZ, we found that none of the Pros+ EEs inherited the β-gal from Su(H)GBE+ EB among 75 clones (Fig. 1E-E″), whereas 23 out of 112 clones had at least one Pdm-1+ EC-expressing β-gal (Fig. 1F-F″). Additionally, we generated MARCM clones using Su(H)GBE-Gal4 instead of Tub-Gal4. Consistently, we found that some Pdm1+ ECs inherited weak GFP from Su(H)GBE+ EB (14 Pdm1+ cells expressing GFP among 153 GFP+ cells; supplementary material Fig. S1A-A″), but none of the EEs inherited GFP from Su(H)GBE+ EBs (0 Pros+ cells expressed GFP among 153 GFP+ cells; supplementary material Fig. S1A-A″). These data again indicate that ECs, but not EEs, are developed from Su(H)GBE+ EBs. The above data suggest that EEs may not be developed from Su(H)GBE+ EBs, but may be generated from ISCs through another mechanism. To further test this possibility, we developed a novel lineage-tracing system to trace cell lineage in the posterior midgut.

Fig. 1.

Su(H)GBE+ EBs are not EE progenitors. (A,A′) Esg+ (green) Pros+ (red) cells (arrows) do not express the EB marker Su(H)GBE-lacZ (arrowheads, purple in A′). (B) The quantification of Esg+ Pros+ Su(H)GBE− and Esg+ Pros+ Su(H)GBE+ cells among all Esg+ cells. Data are represented as mean±s.e.m. (C,C′) Some of the ECs (arrowheads) inherited weak GFP from Su(H)GBE+ EBs; none of the EEs (arrow) inherited GFP from Su(H)GBE+ EBs, suggesting that ECs, but not EEs, are developed from Su(H)GBE+ EBs. (D) The quantification of GFP+ ECs and EEs among all GFP+ cells in Su(H)GBE>GFP posterior midguts. Data are represented as mean±s.e.m. (E-E″) Wild-type MARCM clones with Su(H)GBE-lacZ. Some polyploid ECs (asterisks) express β-Gal inherited from Su(H)GBE-lacZ+ EBs (arrows). However, none of the EEs (arrowhead) expresses β-Gal, suggesting that ECs, but not EEs, are developed from Su(H)GBE+ EBs. (F-F″) Wild-type MARCM clones with Su(H)GBE-lacZ. The arrows indicate a β-Gal+ Pdm-1− EB. The asterisks indicate a β-Gal+ Pdm-1+ EC. The arrowheads indicate a β-Gal− Pdm-1+ EC. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Developing a new lineage-tracing system

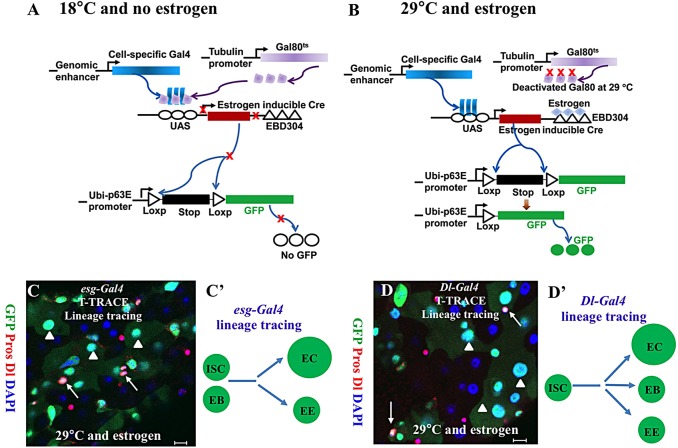

The lineage-tracing system that combines a tamoxifen-inducible Cre knock-in allele with the Rosa26-lacZ reporter strain has been successfully used to identify cell (particularly stem cell) lineages in adult mice (Barker et al., 2007; Takeda et al., 2011). In Drosophila melanogaster, FLP/FRT, an alternative site-specific recombination system originally identified in yeast, has been predominantly used, with great success, to generate a genetic mosaic for clonal analysis (Chou and Perrimon, 1996; Golic and Lindquist, 1989; Lee and Luo, 1999; Xu and Rubin, 1993). These experiments depend on inducing recombination in a few isolated progenitor cells, followed by clonal expansion of these recombined cells (Decotto and Spradling, 2005; Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006; Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006; Singh et al., 2007, 2011; Strand and Micchelli, 2011; Tulina and Matunis, 2001; Xie and Spradling, 1998). The mosaic clonal systems are effective for identifying a marked cell lineage, but they are not ideal for accurately identifying the origin of individual marked cells. A Gal4 technique for real-time and clonal expression (G-TRACE) was developed to identify more precisely the origin of individual cells (Evans et al., 2009). The TARGET system, in which Gal4 is combined with the temperature-sensitive GAL80 protein (Gal80ts), can be used for inducible control of Gal4 activity (McGuire et al., 2003). Theoretically, a combination of the G-TRACE and TARGET systems, which is akin to the mouse-inducible Cre/Rosa26-lacZ reporter system, would enable a precise lineage-tracing experiment to be performed. However, in our experience, the TARGET system always had a low level of leakage that complicated the interpretation of the lineage-tracing results. The Gal4s used in these experiments were all expressed in various cell types in embryos or during other earlier developmental stages. The marked progeny cells might come from other labeled cells during the earlier developmental stages instead of coming from the adult stem cells, if the leakage occurred during the earlier developmental stages. To overcome these complications, we developed a new (to our knowledge) lineage-tracing system (Fig. 2A,B), which combines the main features of the TARGET, G-TRACE and inducible Cre/loxP (Heidmann and Lehner, 2001) systems. We call this new system the TARGET technique for real-time and clonal expression system, or, for simplicity, the T-TRACE system. To prevent possible leakage before the adult stage, we used the double-leakage proofs: the first is a temperature-sensitive Gal4 inhibitor, Gal80ts (McGuire et al., 2003), which suppresses Gal4 activity at the permissive temperature (18°C); the second is an estrogen-inducible Cre whose activity depends on the presence of estrogen. To initiate cell lineage tracing (Heidmann and Lehner, 2001), the flies have to be cultured at a non-permissive temperature (29°C) and fed with food containing 150 μg/ml of estrogen. The stem cell/progenitor-specific Gal4 mediates expression of the Cre recombinase, which in turn removes a loxP-flanked transcriptional termination cassette inserted between a ubiquitin-p63E (Ubi-p63E) promoter fragment and the GFP open reading frame. Therefore, the Ubi-p63E promoter will drive GFP expression in all subsequent daughter cells derived from the initial Gal4-expressing progenitor cells.

Fig. 2.

The T-TRACE analysis system. (A,B) The molecular mechanisms of the T-TRACE system. In this system, TARGET mediates the expression of an estrogen-inducible Cre, which in turn removes a loxP-flanked transcriptional termination cassette inserted between a ubiquitin-p63E (Ubi-p63E) promoter fragment and the GFP open reading frame. Therefore, the Ubi-p63E promoter will drive GFP expression in all subsequent daughter cells derived from the initial Gal4-expressing progenitor cells. (C,C′) Fluorescence images showing T-TRACE analysis of the esg-Gal4 line at 29°C on food with estrogen (C). A schematic shows the result of lineage tracing using esg-Gal4 (C′). (D,D′) Fluorescence images showing T-TRACE analysis of the Dl-Gal4 line at 29°C on food with estrogen (D). A schematic diagram shows the result of lineage tracing using Dl-Gal4 (D′). In C and D, the adult fly posterior midguts were stained with anti-GFP (green), anti-Dl (cytoplasmic, red), anti-Pros (nuclear, red) and DAPI (blue). Arrows, GFP+ Pros+ EEs; arrowheads, GFP+ polyploid ECs. Scale bars: 10 μm.

We tested the T-TRACE system by using esg-Gal4 (in both stem cell ISCs and EBs) and Su(H)GBE-Gal4 [in Su(H)GBE+ EBs only] in the adult Drosophila posterior midgut (Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006; Zeng et al., 2010). When cultured on food without estrogen at 18°C, the flies of both Esg-Gal4/T-TRACE (supplementary material Fig. S2D) and Su(H)GBE-Gal4/T-TRACE (supplementary material Fig. S2H) grew to adulthood with no obvious phenotype, and they did not express GFP in their midguts; when cultured on food without estrogen at 29°C, or on food with estrogen at 18°C, the flies of both Esg-Gal4/T-TRACE (supplementary material Fig. S2B,C) and Su(H)GBE-Gal4/T-TRACE (supplementary material Fig. S2F,G) expressed GFP in a few cells in their midguts, indicating that either condition is causing partial leakage; when cultured on food with estrogen at 29°C, the flies of both Esg-Gal4/T-TRACE (supplementary material Fig. S2A) and Su(H)GBE-Gal4/T-TRACE (supplementary material Fig. S2E) expressed GFP in the cells of the respective Gal4 driver and daughter cells. These results suggest that the T-TRACE system is a reliable and leakage-proof system.

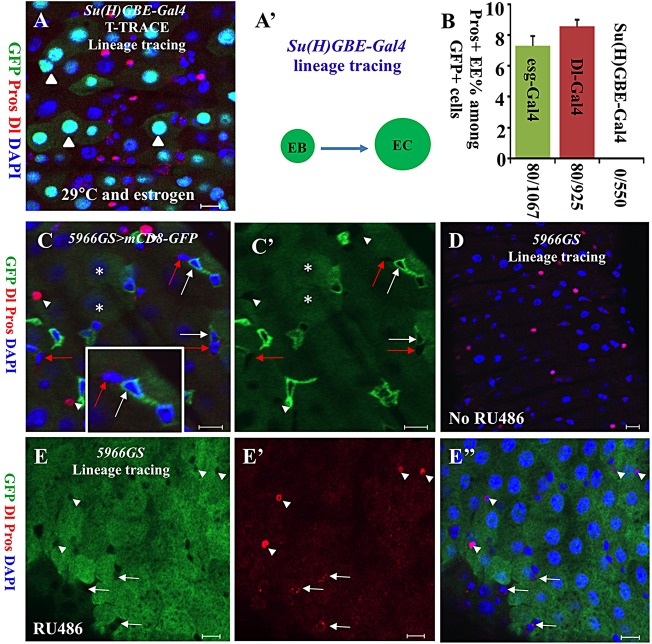

ECs, but not EEs, develop from Su(H)GBE+ EBs

To clarify cell lineage in the posterior midgut, we performed lineage-tracing experiments with the T-TRACE system on esg-Gal4, Dl-Gal4 (in ISCs only) and Su(H)GBE-Gal4 in the adult Drosophila posterior midgut (Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006; Zeng et al., 2010). We cultured the adult flies on food with estrogen at a restrictive temperature (29°C). After 1 week, the flies were dissected, stained and examined for expression of GFP, Dl (ISC marker) and Pros (EE cell marker) under a confocal microscope. We found that EE cells represent 7.5% (80/1067) of the GFP-positive cells from the Esg-Gal4/T-TRACE (Figs 2C,C′ and 3B) and 8.6% (80/925) of the GFP-positive cells from the Dl-Gal4/T-TRACE (Figs 2D,D′ and 3B). Surprisingly, Pros-positive EE cells are totally absent in GFP-positive cells from the Su(H)GBE-Gal4/T-TRACE (Fig. 3A-B). These data suggest that EE cells may be generated from ISCs through another cell type instead of Su(H)GBE+ EBs. Consistently, a recent study has also found that Su(H)GBE+ EBs do not have the capacity to generate EEs, but are rather EC-committed progenitors (Biteau and Jasper, 2014).

Fig. 3.

EEs are not developed from Su(H)GBE+ and 5966GS+ EBs. (A) A fluorescence image showing T-TRACE analysis of the Su(H)GBE-Gal4 line at 29°C on food with estrogen. Arrowheads, GFP+ polyploid ECs. (A′) A schematic diagram of the result of lineage tracing using Su(H)GBE-Gal4. (B) The quantitative percentages of Pros+ cells among GFP+ cells from T-TRACE analysis of esg-Gal4, Dl-Gal4 and Su(H)GBE-Gal4. Data are mean±s.e.m. (C,C′) 5966GS (PswitchPC)-Gal4/UAS-mCD8-GFP expression. GFP is expressed in EBs (white arrows) and ECs (asterisks), but is not expressed in ISCs (red arrows) and EEs (white arrowheads). The inset shows an enlarged view. (D-E″) Fluorescence images showing UAS-flp/5966GS/Act<y+<EGFP analysis at 22°C on food without RU486 (D), or at 22°C on food with RU486 (E-E″). Arrowheads, Pros+ EEs; arrows, Dl+ ISCs. The adult fly posterior midguts were stained with anti-GFP (green), anti-Dl (cytoplasmic, red), anti-Pros (nuclear, red) and DAPI (blue). Scale bars: 10 μm.

Su(H)GBE-lacZ was found highly expressed in the daughter cell (EB) of ISCs with high Dl levels (Ohlstein and Spradling, 2007); thus, EEs may develop from some Su(H)GBElow EBs. To rule out the possibility that some Su(H)GBElow EBs may be the progenitors of EEs, we performed further lineage-tracing experiments using a steroid (RU486)-inducible ‘GeneSwitch’ Gal4 (5966GS) (Mathur et al., 2010; Nicholson et al., 2008) in combination with an Act<y+<EGFP reporter line. The 5966GS is expressed in EBs and ECs, but is excluded from ISCs and EEs (Fig. 3C,C′) (Guo et al., 2014; Hur et al., 2013; Kapuria et al., 2012; Mathur et al., 2010). We cultured the adult flies on food with RU486 at room temperature (∼22°C). Again, we found that none of the 243 Pros-positive EE cells were GFP positive from the UAS-flp/5866GS/Act<y+<EGFP flies (Fig. 3E-E″), indicating that EEs are not generated from 5966GS+ EBs and ECs. No GFP-labeled cells were found when flies were not fed with RU486 (Fig. 3D). These data together suggest that Su(H)GBE+ and 5966GS+ EBs are the progenitors of only ECs, and EEs are likely generated from ISCs through another cell type.

EEs are generated from ISCs through a distinct progenitor

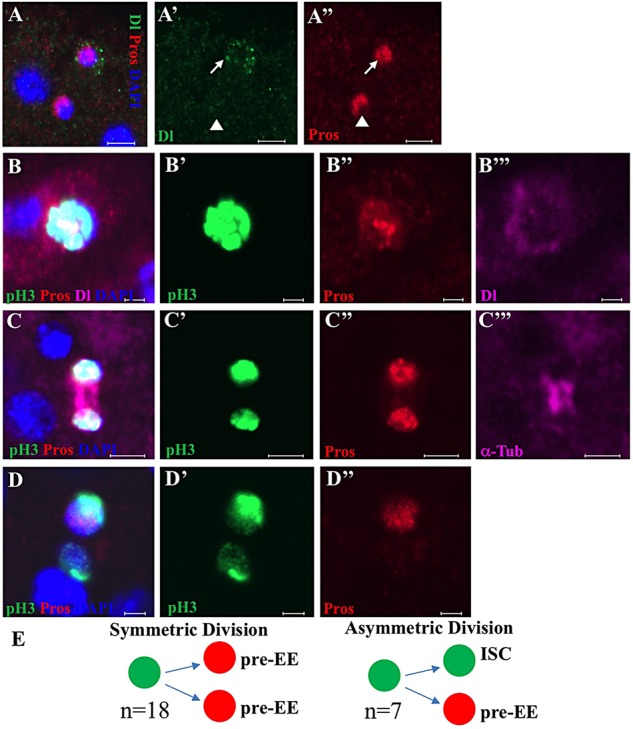

The data above suggest that EEs may not be developed from Su(H)GBE+ and 5966GS+ EBs, but are developed from ISCs through another way. This information suggests that there may be some transit cells expressing both the ISC marker Dl and EE marker Pros that exist during EE maturation from ISCs in the posterior midgut. To test this, we stained posterior midguts with the ISC marker Dl and the EE marker Pros and looked for some transit cells expressing both Dl and Pros. Indeed, about 1.9% of ISCs (11/566, n=11) expressed both Dl and Pros (Fig. 4A-A″) in wild-type posterior midguts. We renamed the Dl+ Pros+ cells ‘pre-EEs (or EE progenitor)’ and the Dl− Pros+ cells ‘mature EEs’ or just ‘EEs’.

Fig. 4.

EE generation during ISC division. (A-A″) A representative image showing a Dl+ Pros+ pre-EE cell (arrows) and Dl− Pros+ EE cell (arrowheads). (B-B‴) Representative images of a pH3+ Pros+ Dl+ cell in the posterior midgut of wild-type flies. (C-C‴) Representative images showing an ISC becoming two pre-EEs through symmetric division. α-Tubulin was used to label the spindle of the dividing cell. (D-D″) Representative images showing an ISC becoming a new ISC and a pre-EE through asymmetric division. In all images, the 1-week-old wild-type flies were stained using the antibodies indicated. Scale bars: 2 μm. (E) Schematic showing the quantitation of EE generation from ISCs through symmetric and asymmetric division in the posterior midguts of wild-type flies.

We unexpectedly found that Pros was expressed in some of the dividing phospho-Histone H3 (pH3)-positive ISC-like cells in NDN (esgts>NDN) midguts (supplementary material Fig. S3A-A″) when we were checking the mitotic index of NDN (esgts>NDN) midguts. This encouraged us to further examine the expression of Pros in dividing pH3+ ISCs in the wild-type posterior midgut. Strikingly, we found that 6.7% (42/628) of pH3+ ISCs express Pros (Fig. 4B-D″; supplementary material Fig. S4) in the wild-type posterior midguts. Consistently, a recent study shows that a few of Pros+ EEs can undergo S-phase and mitotic division (Zielke et al., 2014). We further found that these Pros+ dividing ISCs still also express the ISC marker Dl (pH3+ Dl+ Pros+ cells; Fig. 4B-B‴; supplementary material Fig. S4). Among the pH3+ Dl+ Pros+ cells, some (18/42) went through symmetric division to generate two pre-EEs from one ISC (Fig. 4C-C‴,E; supplementary material Fig. S4B-C‴), and some (7/42) went through asymmetric division to generate one new ISC and one pre-EE (Fig. 4D-E; supplementary material Fig. S4D-D‴) in the wild-type posterior midguts.

EEs are generated from ISCs in one of three ways

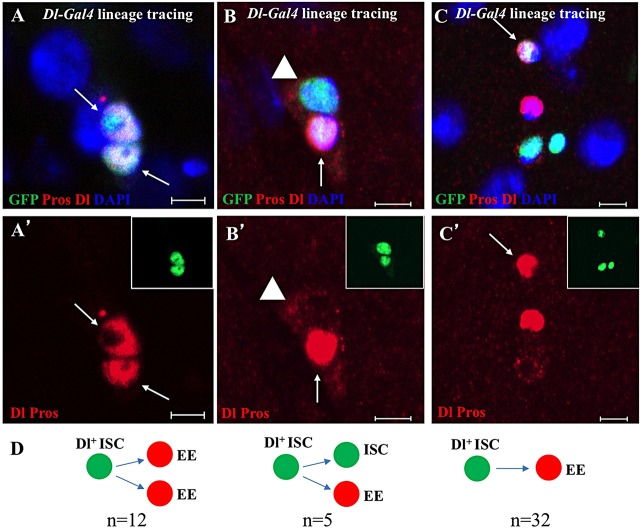

The data above indicate that an ISC can generate two EEs after symmetric division and one ISC and one EE after asymmetric division. To further verify the division pattern, we carefully examined the division patterns of ISCs during lineage tracing in the Dl-Gal4/T-TRACE flies (Fig. 5) at 5 days on food with estrogen at 29°C. In addition to the previously reported multiple-cell ISC lineages that contain ISCs, EBs, ECs and EEs (72% of ISC lineages contained at least three cells; Micchelli and Perrimon, 2006; Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006), we also detected that 11% of ISC lineages contained two cells and that 17% of ISC clones were one-cell ISC lineages. To understand EE generation in detail, we focused our analysis on the two-cell and one-cell ISC lineages containing EE cell(s) because they more likely represent the early division behaviors of individual ISCs, and it is technically difficult to precisely track cell lineages in the multiple-cell ISC clones. Consistent with symmetric and asymmetric division of ISCs to generate EEs, in some of the two-cell ISC lineages, both cells were Pros+ EE cells (n=12 from seven guts; Fig. 5A,A′); in others, one cell is a Pros+ EE and the other is a Dl+ ISC (n=5 from seven guts; Fig. 5B,B′). We also found one-cell ISC lineages in which the single cell is a Pros+ EE (n=32 from seven guts; Fig. 5C,C′), indicating that an ISC may directly convert to an EE through a post-mitotic EE progenitor.

Fig. 5.

EEs are generated by symmetric and asymmetric division of ISCs and are directly converted from ISCs. Fluorescence images showing T-TRACE analysis of the Dl-Gal4 line at 29°C on food with estrogen. The adult fly posterior midguts were stained with anti-GFP (green), anti-Dl (cytoplasmic, red), anti-Pros (nuclear, red) and DAPI (blue). Scale bars: 5 μm. (A,A′) An ISC becomes two EEs (arrows) through symmetric division. (B,B′) An ISC becomes a new ISC (arrowhead) and an EE (arrow) through asymmetric division. (C,C′) An ISC directly becomes an EE (arrow). (D) Schematic showing the quantitation of EE generation from ISCs. The GFP-marked cells are illustrated in the insets of A′,B′,C′.

The data above suggest that EE cells can be generated from ISCs in one of three ways: an ISC directly becoming one EE cell (32/49=65%; Fig. 5C-D); an ISC becoming two EE cells through symmetric division (12/49=24%; Fig. 5A,A′,D); or an ISC becoming one new ISC and one EE cell through asymmetric division (5/49=10%; Fig. 5B,B′,D). An EE cell occurs in either two-cell pairs (Ohlstein and Spradling, 2006) or in a single cell in the wild-type Drosophila midgut (supplementary material Fig. S5); the ratio of an EE cell pair to a single cell is 1:4.5. These EE cell pairs may be generated through symmetric ISC division, whereas the single EE cells may be generated through either asymmetric ISC division or direct conversion of an ISC into an EE cell.

Pros determines ISCs commitment to EEs

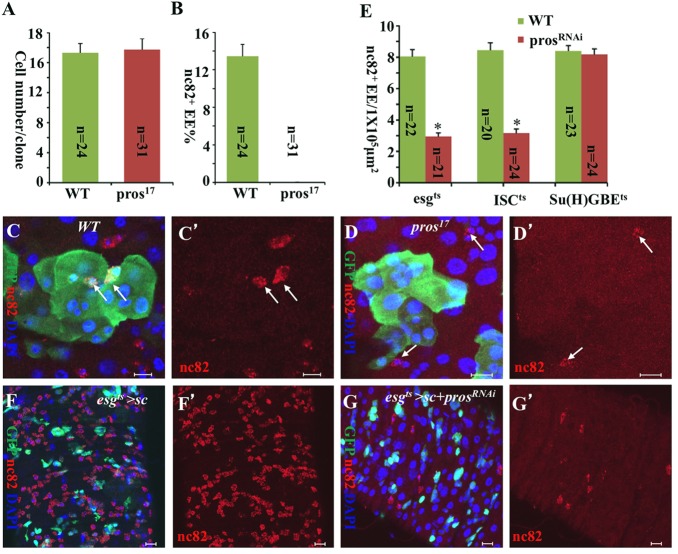

The expression of Pros in pre-EEs suggests that Pros may play an important role in the conversion of ISCs into EEs. To understand the function of pros in EE formation, we generated GFP-marked ISC clones that were homozygous for the loss-of-function allele pros17 (Cook et al., 2003), using the MARCM technique (Lee and Luo, 1999). Seven days after clone induction, we found that GFP-marked clones of pros17 were completely devoid of nc82+ EEs (Fig. 6B,D,D′) compared with their wild-type counterparts (Fig. 6B-C′), whereas the ISCs in the GFP-marked clones showed normal proliferation (Fig. 6A). Consistently, the EE population dramatically decreased when we knocked down pros in both ISCs and EBs by expressing UAS-prosRNAi in these cells using esgts driver (Fig. 6E). To rule out the possibility that Pros directly regulates the expression of the EE cell marker Brp (the antigen of nc82) in contexts other than in EE cell formation, we identified another EE cell-specific marker, Dachshund, which is a transcriptional regulator required for eye and leg development (Mardon et al., 1994). The anti-Dac antibody Mabdac1-1 specifically labeled Pros+ EEs in wild-type midguts (supplementary material Fig. S6A-A″), as well as excessive EEs in UAS-NDN- (supplementary material Fig. S6B) and UAS-ase- (supplementary material Fig. S6C) overexpressing midguts. Consistently, we did not detect Dac+ EEs in GFP-marked pros17 clones (supplementary material Fig. S6D,F,F′) compared with their wild-type counterparts (supplementary material Fig. S6D-E′). Together, these data suggest that Pros regulates EE cell fate determination.

Fig. 6.

Pros regulates EE cell fate determination in ISCs. (A) The quantitative cell numbers per clone in C-D′. (B) The quantitative percentages of nc82+ EEs in GFP+ clones in C-D′. Data are represented as mean±s.e.m. (C-D′) MARCM clones of wild-type control (C,C′) and pros17 (D,D′). Seven days after clone induction, GFP-marked clones of pros17 (D,D′) were completely devoid of nc82+ EEs (arrow) compared with their wild-type counterparts (C,C′), whereas the clone sizes are similar (A). (E) The numbers of nc82+ EE cells in the posterior midguts of prosRNAi driven by indicated Gal4, compared with wild-type controls. Data are represented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.01. (F,F′) The overexpression of sc in ISCs and EBs (esgts>sc). (G,G′) The overexpression of sc and prosRNAi in ISCs and EBs (esgts>sc+prosRNAi). The overexpression of prosRNAi suppressed the excess EE phenotype associated with sc overexpression, indicating that Pros functions either downstream of or parallel to Sc. The adult fly posterior midguts were stained with anti-GFP (green), anti-nc82 (red) and DAPI (blue). Scale bars: 10 μm.

To further clarify whether Pros functions in ISCs or Su(H)GBE+ EBs to regulate EE cell fate determination, we generated an ISC-specific Gal4 system, in which Su(H)GBE-Gal80 blocks the activation by Gal4 of Esg-Gal4 in Su(H)GBE+ EBs, but keeps it active in ISCs only (this study; Wang et al., 2014). We named this Gal4 ‘ISC-Gal4’ and found that it is much stronger than the previously published Dl-Gal4 (Zeng et al., 2010). Knockdown of pros in ISCs using the ISC-Gal4 system combined with tub-Gal80ts (esg-Gal4, UAS-GFP; Su(H)-Gal80, tub-Gal80ts; referred to as ISCts) resulted in fewer nc82+ EEs (Fig. 6E), whereas knockdown of pros in Su(H)GBE+ EBs using Su(H)GBE-Gal4.UAS-mCD8-GFP; tub-Gal80ts (referred to as Su(H)GBEts) generated a phenotype that was no different from that of the wild-type control (Fig. 6E). Surprisingly, however, the overexpression of pros in ISCs and EBs did not increase EEs in comparison with the wild-type control in the posterior midgut epithelium (data not shown).

These data suggest that Pros is necessary, but not sufficient, for EE cell fate determination in ISCs.

Pros functions downstream of or parallel to the achaete-scute complex to determine EE fate in ISCs

The members of the achaete-scute complex (AS-C), Scute (Sc) and Asense (Ase), have been shown to play a major role in EE cell fate determination and to be upregulated in the midgut that expressed a dominant-negative form of N (NDN) (Bardin et al., 2010). The overexpression of Sc or Ase in both ISCs and EBs by Esg-Gal4 resulted in a dramatic increase in EEs (Bardin et al., 2010). To further clarify whether Sc and Ase function in ISCs or EBs to regulate EE cell fate determination, we expressed UAS-sc specifically in ISCs or Su(H)GBE+ EBs using ISCts or Su(H)GBEts. Compared with the wild-type control (supplementary material Fig. S7A,D,I), the expression of UAS-sc in ISCs generated an excess number of EE cells (supplementary material Fig. S7B,I), which were indistinguishable from those generated previously by the expression of UAS-sc in both ISCs and EBs using Esg-Gal4 (Bardin et al., 2010); however, the expression of UAS-sc in Su(H)GBE+ EBs (supplementary material Fig. S7E,I) generated a phenotype that was no different from the wild-type control (supplementary material Fig. S7D,I). Likewise, the overexpression of the other three members of AS-C, including ase, l(1)sc and achaete (ac), in ISCs but not in Su(H)GBE+ EBs, resulted in a dramatic increase in EEs (data not shown). Conversely, we knocked down sc in ISCs or EBs by expressing UAS-scRNAi in these cells, and we found that the knockdown of sc in ISCs resulted in reduced EEs (supplementary material Fig. S7C,I), whereas the knockdown of sc in Su(H)GBE+ EBs did not change the EE cell population (supplementary material Fig. S8F,I).

Similarly, we expressed UAS-NDN in ISCs using cell type-specific Gal4 and found that the expression of UAS-NDNin ISCs caused both ISC and EE cell expansion phenotype, which is indistinguishable from those generated previously by the expression of UAS-NDN in both ISCs and EBs using Esg-Gal4 (supplementary material Fig. S8A,B; Bardin et al., 2010; Ohlstein and Spradling, 2007; Zeng et al., 2013). To explicitly evaluate the function of N in Su(H)GBE+ EBs, we expressed UAS-NDN in Su(H)GBE+ EBs using Su(H)GBE-Gal4 along with the T-TRACE system. Interestingly, compared with the wild-type control (supplementary material Fig. S8C), the expression of UAS-NDN in Su(H)GBE+ EBs completely blocked the differentiation of Su(H)GBE+ EBs into ECs (supplementary material Fig. S8D), whereas the EE cell density was not changed at all (supplementary material Fig. S8E). These data, plus previously published data, suggest that N regulates EE cells through Sc and Ase only in ISCs.

To further determine an epistatic relationship between AS-C and Pros, we expressed UAS-sc and UAS-prosRNAi in ISCs at the same time using esgts. Interestingly, compared with a dramatic increase in nc82+ EEs in the sc overexpression (esgts>sc) midgut, the expression of prosRNAi in the sc overexpression midgut (esgts>sc+prosRNAi; Fig. 6G,G′) suppressed the excess EE cell phenotypes associated with overexpressing sc (esgts>sc; Fig. 6F,F′). Likewise, the expression of prosRNAi in the ase midgut (esgts>ase+prosRNAi; supplementary material Fig. S7H) also suppressed the excess EE cell phenotypes associated with overexpressing ase (esgts>ase; supplementary material Fig. S7G). Together, Pros functions either downstream of or parallel to AS-C to regulate EE cell fate in ISCs.

DISCUSSION

In the adult Drosophila posterior midgut, both terminally differentiated EC and EE cells are generated from the ISC. However, it is not clear how the differentiated cells are generated from the ISC. In this study, we found that only ECs are generated through the Su(H)GBE+ immature progenitor EBs, whereas EEs are generated from ISCs through a distinct type of progenitors by an ISC converting to an EE, an ISC becoming a new ISC and an EE through asymmetric division, or an ISC becoming two EEs through symmetric division. The transcriptional factor Pros functions specifically in ISCs to guide the commitment of ISCs into EEs.

The anatomy and cell types in the Drosophila midgut are similar to those in the mammalian small intestine: both systems are a tubular epithelium composed of absorptive and secretory cells, which are constantly replenished by ISCs (Wang and Hou, 2010). We demonstrated that EEs are generated from ISCs through a distinct type of progenitor in the Drosophila, based on the following evidence. First, we found that some Esg+ cells express the EE marker Pros, but none of the Su(H)GBE+ cells expresses Pros. Second, we identified that Su(H)GBE+ EBs are the progenitors of ECs, instead of EEs, by using a novel lineage-tracing system: T-TRACE. To rule out the possibility that some Su(H)GBElow EBs may be the progenitors of EEs, we performed a lineage-tracing experiment using another EB Gal4 driver, 5966GS (Guo et al., 2014; Hur et al., 2013; Kapuria et al., 2012; Mathur et al., 2010), and further confirmed that 5966GS+ EBs are also not the progenitors of EE cells. Third, we identified a transit cell type called pre-EE (or EE progenitor), which expresses both the ISC marker Dl and the EE marker Pros. Finally, we demonstrated that ISCs can convert into EE cells without cell division, by which 65% of EE cells are generated. In addition to direct conversion of an ISC into an EE cell, ISCs can undergo mitotic division to generate two EE cells by symmetric division, and an EE cell and a new ISC by asymmetric division, by which 35% of EEs are generated. Consistently, quiescent ISCs in mice have been recently identified as direct precursors of secretory Paneth cells and EE cells (Buczacki et al., 2013). These quiescent ISCs can differentiate into secretory Paneth cells and EE cells with minimal cell division (Buczacki et al., 2013). Recent studies in ISCs of mice also suggest that stem cell pools are maintained through population asymmetry. Some stem cells are lost due to differentiation or damage and their positions are filled by other stem cells through symmetric division (Snippert et al., 2010; Simons and Clevers, 2011). Further insight into the mechanism of mouse ISC regulation has been provided by a combination of in vivo and in vitro assays (Sato et al., 2011). It was found that the Lgr5+ stem cells are closely associated with the niche-supporting Paneth cells. Lgr5hi cells undergo neutral competition for contact with Paneth cell surface after symmetrical division. The detached stem cells are unable to maintain stem cell competence without access to short-range signals and progressively differentiate. In Drosophila posterior midgut, the predominance of ISC symmetric division is one of the main mechanisms for increasing the gut cell number during adaptive growth (O'Brien et al., 2011). The method of EE generation by ISCs may also change during environmental and dietary stresses to meet physiological need. For example, symmetric division of an ISC into two EEs may predominate when more secreting EEs are needed.

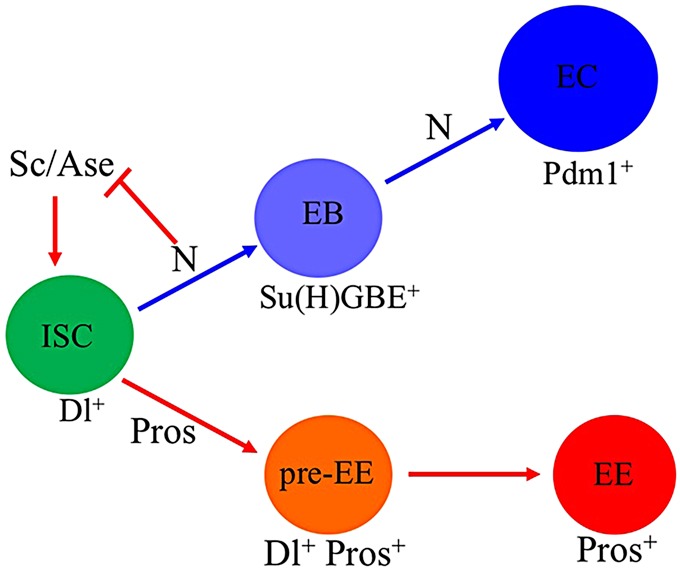

Based on the results of this study and previously published information (Bardin et al., 2010; Beebe et al., 2010; Ohlstein and Spradling, 2007; Perdigoto et al., 2011), we proposed a model of ISC lineage specification (Fig. 7). An ISC can generate an Su(H)GBE+ EB for EC lineage differentiation or a pre-EE for EE cell lineage differentiation. The N signaling promotes EC lineage differentiation and inhibits EE lineage differentiation through promoting ISC to Su(H)GBE+ EB commitment and blocking ISC to pre-EE commitment by repressing expression of sc and ase in ISCs, whereas N signaling in Su(H)GBE+ EBs is required for promoting Su(H)GBE+ EB to EC differentiation. The transcriptional factor Pros functions specifically in ISCs to determine commitment of ISCs into EEs. Both Pre-EEs and Su(H)GBE+ EBs are intermediate diploid cells, but they are different from each other. First, Su(H)GBE+ EBs do not express the ISC marker Dl, but pre-EEs do. Second, Su(H)GBE+ EBs are post-mitotic cells (Ohlstein and Spradling, 2007), but some pre-EEs are able to undergo mitotic division. Our understanding of the flexibility of stem cell commitment is of the utmost importance for not only basic stem cell biology, but also targeted tumor therapy.

Fig. 7.

Model of intestinal stem cell lineage generation. A model of intestinal stem cell lineage development in the adult Drosophila posterior midgut. More details are provided in the text.

The T-TRACE lineage-tracing method

In mouse, the combination of a tamoxifen-inducible Cre knock-in allele with the Rosa26-lacZ reporter strain has been successfully used to identify stem cell lineages in adult mice (Barker et al., 2007; Takeda et al., 2011). In Drosophila, the FLP/FRT-based site-specific recombination system and its derivatives (including MARCM system) have been successfully used to identify cell (particularly stem cell) lineages. The FLP/FRT-based mosaic clonal systems are very effective for identifying a marked cell lineage, but they are not ideal for accurately identifying the origin of individual marked cells. In this study, we developed a new lineage-tracing system: T-TRACE. Similar to the mouse lineage-tracing system, the T-TRACE lineage-tracing method is a gene-based system and allows the accurate identification of all cells derived from one marked cell. However, the T-TRACE method does not require chromosome segregation at mitosis to label cells and may have limitation in some applications. Additionally, as the T-TRACE system is estrogen inducible, the variable efficiency of estrogen delivery to different tissue may obscure the tracing result. Thus, the optimal concentration of estrogen has to be determined for T-TRACE for different tissue. The combination of the FLP/FRT-based site-specific recombination system and the T-TRACE system, such as first using the FLP/FRT-based site-specific recombination system to identify general cell (particularly stem cell) lineages and then using the T-TRACE system to accurately identify the origin of individually marked cells, will give more precise and accurate information.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly stocks

The following fly strains were used: esg-Gal4 line (from Shigeo Hayashi, RIKEN, Japan); Dl-Gal4 and Su(H)GBE-Gal4 were generated in our laboratory and have been described previously (Zeng et al., 2010); UAS-NDN (from Mark Fortini, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, USA); UAS-ase (from Yuh-Nung Jan, UCSF, CA, USA); UAS-Cre-EBD304 (from Christian Lehner, University of Zurich, Switzerland); FRT82B-pros17 and UAS-prosRNAi (from Tiffany Cook, University of Cincinnati, OH, USA); 5966 GS (from Haig Keshishian, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA); and Su(H)GBE-lacZ (from Sarah Bray, University of Cambridge, UK). The following strains were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center: UAS-sc; tub-Gal80ts; UAS-prosRNAi-1 (BL26745); and UAS-pros and fly lines used for MARCM clones, including FRT82B-piM; SM6,hs-flp; MKRS,hs-flp, and FRT82B tub-Gal80. UAS-scRNAi (v105951) and UAS-prosRNAi-2 (v101477) were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC).

Flies were raised on standard fly food at 25°C and 65% relative humidity, unless otherwise indicated.

Generation of Ubi-loxP-Stop-loxP-GFP (Ubi-p63E<Stop<GFP) transgenic flies

A 1.96 kb promoter of Ubi-p63E (CG11624) (Evans et al., 2009) was amplified from Drosophila genomic DNA and cloned into vector pStinger at the EcoRI and KpnI sites, using the following primers to produce the Ubi-GFP construct: 5′-GATGAATTCTGTCCGTATCCTTTAGGC-3′ and 5′-TGAGGTACCTTGGATTATTCTGCGGGA-3′.

Then the stop cassette with flanking loxP sites was amplified from the UAS-dBrainbow construct (Hampel et al., 2011) using the following primers: 5′- AGTGGTACCATAACTTCGTATAAAGTATCC-3′ and 5′-AG-TGGTACCATAACTTCGTATAGGATACTT-3′.

The PCR product was then cloned into Ubi-pStiner at the KpnI sites to produce the Ubi-loxP-Stop-loxP-GFP. The above construct was sequenced, purified, and microinjected into embryos using the standard method.

Lineage tracing

T-TRACE

The lineage-tracing system is doubly controlled by both temperature shift and estrogen induction. To perform lineage-tracing experiments, we used the following flies: Ubi-p63E<Stop<EGFP,esg-Gal4; tub-Gal80ts, UAS-cre-EBD304; Ubi-p63E<Stop<EGFP; Dl-Gal4/tub-Gal80ts, UAS-cre-EBD304; and Ubi-p63E<Stop<EGFP, Su(H)GBE-Gal4; tub-Gal80ts, UAS-cre-EBD304.

These flies were cultured on food without estrogen at 18°C. To initiate the lineage-tracing experiment, 3- to 5-day-old flies were transferred to new food containing 150 μg/ml of estrogen at 29°C for 7 days before dissection.

Pswitch tracing

UAS-flp/5966GS (PswitchPC)-Gal4/Act<y+<EGFP flies were cultured on food containing RU-486 (10 µg/ml) (Sigma) at 29°C for 7 days before dissection.

MARCM clonal analysis

To induce MARCM clones of FRT82B-piM (as a wild-type control) and FRT82B-pros17, we generated the following flies: act>y+>Gal4, UAS-GFP/SM6, hs-flp; FRT82B tub-Gal80/-piM (or -pros17). Three- or four-day-old adult female flies were heat-shocked for 45 min twice, at an interval of 8-12 h, at 37°C. The flies were transferred to fresh food daily after the final heat shock, and their posterior midguts were processed for staining at the indicated times.

RNAi-mediated gene depletion

Male UAS-RNAi transgene flies were crossed with female virgins of esg-Gal4, UAS-GFP; tub-Gal80ts, esg-Gal4,UAS-GFP; Su(H)GBE-Gal80, tub-Gal80ts (for ISC-specific expression) or of Su(H)GBE-Gal4,UAS-GFP; tub-Gal80ts [for Su(H)GBE+ EB-specific expression]. The flies were cultured at 18°C. Three- to five-day-old adult flies with the appropriate genotype were transferred to new vials at 29°C for 7 days before dissection.

Fly genotypes

Fig. 1A: Su(H)GBE-lacZ; esg-Gal4, UAS-GFP.

Fig. 1E-F‴: Su(H)GBE-lacZ/hs-flp, tub-Gal4, UAS-GFP; FRT82b, tub-Gal80/FRT82b, piM.

Fig. 2C: Ubi-p63E<Stop<EGFP, esg-Gal4; tub-Gal80ts, UAS-cre-EBD304.

Fig. 2D: Ubi-p63E<Stop<EGFP; Dl-Gal4/tub-Gal80ts, UAS-cre-EBD304.

Fig. 3A: Ubi-p63E<Stop<EGFP, Su(H)GBE-Gal4; tub-Gal80ts, UAS-cre-EBD304.

Fig. 3D-E″: UAS-flp; 5966GS/Act<y+<EGFP.

Fig. 5: Ubi-p63E<Stop<EGFP; Dl-Gal4/tub-Gal80ts, UAS-cre-EBD304.

Fig. 6C: act>y+>Gal4, UAS-GFP/SM6, hs-flp; FRT82B tub-Gal80/FRT82B, piM.

Fig. 6D: act>y+>Gal4, UAS-GFP/SM6, hs-flp; FRT82B tub-Gal80/FRT82B, pros17.

Fig. 6F-F′: esg-Gal4, UAS-GFP/UAS-scute; Tub-Gal80ts.

Fig. 6G-G′: esg-Gal4, UAS-GFP/UAS-scute; Tub-Gal80ts/UAS-ProsRNAi.

Histology and image capture

The fly intestines were dissected in PBS and fixed in PBS containing 4% formaldehyde for 20 min. After three 5-min rinses with PBT (PBS+0.1% Triton X-100), the samples were blocked with PBT containing 5% normal goat serum and kept overnight at 4°C. Then the samples were incubated with the primary antibody at room temperature for 2 h and incubated with the fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were mounted in the Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). We used the following antibodies: mouse anti-β-Gal (Promega, Z3781; 1:200); mouse anti-Dl (DSHB, C594.9B; 1:50); rabbit anti-Pdm-1 (a gift from Xiaohang Yang, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China; 1:1000); mouse anti-Pros (DSHB, MR1A; 1:50); nc82 (DSHB, nc82; 1:20); guinea pig anti-Pros (a gift from Tiffany Cook, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA; 1:3000); and chicken anti-GFP (Abcam, ab101863; 1:3000). Secondary antibodies used were goat anti-mouse, anti-chicken, and goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa 488, Alexa 568 or Alexa 647 (Molecular Probes, A-11039, A-11031, A-11029, A-11034, A-11036, A-21244, A-21236; all 1:400). Images were captured with the Zeiss LSM 510 confocal system and processed with the LSM Image Browser and Adobe Photoshop. Different subregions of the midgut have distinct molecular signatures and stem cells (Buchon et al., 2013; Marianes and Spradling, 2013). To avoid confusion, we focused only on the posterior midgut in this study.

Quantification and statistical analysis

To quantify the percentage of Pros+ or nc82+ EEs, the Pros+ or nc82+ EEs and total cells were counted in a 1×105 µm2 area of a single confocal plane. All the data were analyzed using Student's t-test; sample size (n) is shown in the text or figure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Jiangsha Zhao, Chhavi Chauhan and Jennifer Taylor for critical reading of the manuscript; Shigeo Hayashi, Mark Fortini, Yuh Nung Jan, Tiffany Cook, Christian Lehner, Haig Keshishian, Sarah Bray, VDRC, the Bloomington Stock Centers and TRiP at Harvard Medical School for fly stocks; Julie Simpson for the UAS-dBrainbow DNA construct; Utpal Banerjee for the Ubi-p63E DNA construct; Tiffany Cook, Xiaohang Yang and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for antibodies; and S. Lockett for help with the confocal microscope.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

X.Z. and S.X.H. conceived the project, designed and performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.113357/-/DC1

References

- Bardin A. J., Perdigoto C. N., Southall T. D., Brand A. H. and Schweisguth F. (2010). Transcriptional control of stem cell maintenance in the Drosophila intestine. Development 137, 705-714 10.1242/dev.039404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker N., van Es J. H., Kuipers J., Kujala P., van den Born M., Cozijnsen M., Haegebarth A., Korving J., Begthel H., Peters P. J. et al. (2007). Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 449, 1003-1007 10.1038/nature06196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe K., Lee W.-C. and Micchelli C. A. (2010). JAK/STAT signaling coordinates stem cell proliferation and multilineage differentiation in the Drosophila intestinal stem cell lineage. Dev. Biol. 338, 28-37 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biteau B. and Jasper H. (2014). Slit/Robo signaling regulates cell fate decisions in the intestinal stem cell lineage of Drosophila. Cell Rep. 7, 1867-1875 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biteau B., Hochmuth C. E. and Jasper H. (2011). Maintaining tissue homeostasis: dynamic control of somatic stem cell activity. Cell Stem Cell 9, 402-411 10.1016/j.stem.2011.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchon N., Osman D., David F. P. A., Fang H. Y., Boquete J.-P., Deplancke B. and Lemaitre B. (2013). Morphological and molecular characterization of adult midgut compartmentalization in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 3, 1725-1738 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczacki S. J. A., Zecchini H. I., Nicholson A. M., Russell R., Vermeulen L., Kemp R. and Winton D. J. (2013). Intestinal label-retaining cells are secretory precursors expressing Lgr5. Nature 495, 65-69 10.1038/nature11965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou T. B. and Perrimon N. (1996). The autosomal FLP-DFS technique for generating germline mosaics in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 144, 1673-1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook T., Pichaud F., Sonneville R., Papatsenko D. and Desplan C. (2003). Distinction between color photoreceptor cell fates is controlled by Prospero in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 4, 853-864 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00156-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decotto E. and Spradling A. C. (2005). The Drosophila ovarian and testis stem cell niches: similar somatic stem cells and signals. Dev. Cell 9, 501-510 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans C. J., Olson J. M., Ngo K. T., Kim E., Lee N. E., Kuoy E., Patananan A. N., Sitz D., Tran P., Do M.-T. et al. (2009). G-TRACE: rapid Gal4-based cell lineage analysis in Drosophila. Nat. Methods 6, 603-605 10.1038/nmeth.1356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golic K. G. and Lindquist S. (1989). The FLP recombinase of yeast catalyzes site-specific recombination in the Drosophila genome. Cell 59, 499-509 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90033-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Karpac J., Tran S. L. and Jasper H. (2014). PGRP-SC2 promotes gut immune homeostasis to limit commensal dysbiosis and extend lifespan. Cell 156, 109-122 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakim R. S., Baldwin K. and Smagghe G. (2010). Regulation of midgut growth, development, and metamorphosis. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 55, 593-608 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel S., Chung P., McKellar C. E., Hall D., Looger L. L. and Simpson J. H. (2011). Drosophila Brainbow: a recombinase-based fluorescence labeling technique to subdivide neural expression patterns. Nat. Methods 8, 253-259 10.1038/nmeth.1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidmann D. and Lehner C. F. (2001). Reduction of Cre recombinase toxicity in proliferating Drosophila cells by estrogen-dependent activity regulation. Dev. Genes Evol. 211, 458-465 10.1007/s004270100167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur J. H., Bahadorani S., Graniel J., Koehler C. L., Ulgherait M., Rera M., Jones D. L. and Walker D. W. (2013). Increased longevity mediated by yeast NDI1 expression in Drosophila intestinal stem and progenitor cells. Aging 5, 662-681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H. and Edgar B. A. (2011). Intestinal stem cells in the adult Drosophila midgut. Exp. Cell Res. 317, 2780-2788 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Patel P. H., Kohlmaier A., Grenley M. O., McEwen D. G. and Edgar B. A. (2009). Cytokine/Jak/Stat signaling mediates regeneration and homeostasis in the Drosophila midgut. Cell 137, 1343-1355 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapuria S., Karpac J., Biteau B., Hwangbo D. and Jasper H. (2012). Notch-mediated suppression of TSC2 expression regulates cell differentiation in the Drosophila intestinal stem cell lineage. PLoS Genet. 8, e1003045 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T. and Luo L. (1999). Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron 22, 451-461 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80701-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardon G., Solomon N. M. and Rubin G. M. (1994). dachshund encodes a nuclear protein required for normal eye and leg development in Drosophila. Development 120, 3473-3486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marianes A. and Spradling A. C. (2013). Physiological and stem cell compartmentalization within the Drosophila midgut. Elife 2, e00886 10.7554/eLife.00886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur D., Bost A., Driver I. and Ohlstein B. (2010). A transient niche regulates the specification of Drosophila intestinal stem cells. Science 327, 210-213 10.1126/science.1181958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire S. E., Le P. T., Osborn A. J., Matsumoto K. and Davis R. L. (2003). Spatiotemporal rescue of memory dysfunction in Drosophila. Science 302, 1765-1768 10.1126/science.1089035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micchelli C. A. and Perrimon N. (2006). Evidence that stem cells reside in the adult Drosophila midgut epithelium. Nature 439, 475-479 10.1038/nature04371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson L., Singh G. K., Osterwalder T., Roman G. W., Davis R. L. and Keshishian H. (2008). Spatial and temporal control of gene expression in Drosophila using the inducible GeneSwitch GAL4 system. I. Screen for larval nervous system drivers. Genetics 178, 215-234 10.1534/genetics.107.081968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlstein B. and Spradling A. (2006). The adult Drosophila posterior midgut is maintained by pluripotent stem cells. Nature 439, 470-474 10.1038/nature04333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlstein B. and Spradling A. (2007). Multipotent Drosophila intestinal stem cells specify daughter cell fates by differential notch signaling. Science 315, 988-992 10.1126/science.1136606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien L. E., Soliman S. S., Li X. and Bilder D. (2011). Altered modes of stem cell division drive adaptive intestinal growth. Cell 147, 603-614 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdigoto C. N., Schweisguth F. and Bardin A. J. (2011). Distinct levels of Notch activity for commitment and terminal differentiation of stem cells in the adult fly intestine. Development 138, 4585-4595 10.1242/dev.065292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., van Es J. H., Snippert H. J., Stange D. E., Vries R. G., van den Born M., Barker N., Shroyer N. F., van de Wetering M. and Clevers H. (2011). Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature 469, 415-418 10.1038/nature09637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons B. D. and Clevers H. (2011). Strategies for homeostatic stem cell self-renewal in adult tissues. Cell 145, 851-862 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. R., Liu W. and Hou S. X. (2007). The adult Drosophila malpighian tubules are maintained by multipotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 1, 191-203 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. R., Zeng X., Zheng Z. and Hou S. X. (2011). The adult Drosophila gastric and stomach organs are maintained by a multipotent stem cell pool at the foregut/midgut junction in the cardia (proventriculus). Cell Cycle 10, 1109-1120 10.4161/cc.10.7.14830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snippert H. J., van der Flier L. G., Sato T., van Es J. H., van den Born M., Kroon-Veenboer C., Barker N., Klein A. M., van Rheenen J., Simons B. D. et al. (2010). Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell 143, 134-144 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand M. and Micchelli C. A. (2011). Quiescent gastric stem cells maintain the adult Drosophila stomach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17696-17701 10.1073/pnas.1109794108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda N., Jain R., LeBoeuf M. R., Wang Q., Lu M. M. and Epstein J. A. (2011). Interconversion between intestinal stem cell populations in distinct niches. Science 334, 1420-1424 10.1126/science.1213214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulina N. and Matunis E. (2001). Control of stem cell self-renewal in Drosophila spermatogenesis by JAK-STAT signaling. Science 294, 2546-2549 10.1126/science.1066700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. and Hou S. X. (2010). Regulation of intestinal stem cells in mammals and Drosophila. J. Cell. Physiol. 222, 33-37 10.1002/jcp.21928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Zeng X., Ryoo H. D. and Jasper H. (2014). Integration of UPRER and oxidative stress signaling in the control of intestinal stem cell proliferation. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004568 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman I. L. (2000). Stem cells: units of development, units of regeneration, and units in evolution. Cell 100, 157-168 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81692-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie T. and Spradling A. C. (1998). decapentaplegic is essential for the maintenance and division of germline stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Cell 94, 251-260 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81424-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T. and Rubin G. M. (1993). Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development 117, 1223-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Chauhan C. and Hou S. X. (2010). Characterization of midgut stem cell- and enteroblast-specific Gal4 lines in Drosophila. Genesis 48, 607-611 10.1002/dvg.20661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Lin X. and Hou S. X. (2013). The Osa-containing SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex regulates stem cell commitment in the adult Drosophila intestine. Development 140, 3532-3540 10.1242/dev.096891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielke N., Korzelius J., van Straaten M., Bender K., Schuhknecht G. F. P., Dutta D., Xiang J. and Edgar B. A. (2014). Fly-FUCCI: a versatile tool for studying cell proliferation in complex tissues. Cell Rep. 7, 588-598 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.