Abstract

Insulin is the gold standard for treatment of hyperglycemia during pregnancy, when lifestyle measures do not maintain glycemic control during pregnancy. However, recent studies have suggested that certain oral hypoglycemic agents (metformin and glyburide) may be safe and be acceptable alternatives. There are no serious safety concerns with metformin, despite it crossing the placenta. Neonatal outcomes are also comparable, with benefit of reductions in neonatal hypoglycemia, maternal hypoglycemia and weight gain, and improved treatment satisfaction. Glibenclamide is more effective in lowering blood glucose in women with gestational diabetes, and with a lower treatment failure rate than metformin. Although generally well-tolerated, some studies have reported higher rates of pre-eclampsia, neonatal jaundice, longer stay in the neonatal care unit, macrosomia, and neonatal hypoglycaemia. There is also paucity of long-term follow-up data on children exposed to oral agents in utero. This review aims to provide an evidence-based approach, concordant with basic and clinical pharmacological knowledge, which will help medical practitioners use oral anti-diabetic agents in a rational and pragmatic manner. Pubmed search was made using Medical Subject Headings (MESH) terms “Diabetes” and “Pregnancy” and “Glyburide”; “Diabetes” and “Pregnancy” and “Metformin”. Limits were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analysis. The expert reviews on the topic were also used for discussion. Additional information (studies/review) pertaining to discussion under sub-headings like safety during breastfeeding; placental transport; long-term safety data were searched (pubmed/cross-references/expert reviews).

Keywords: Diabetes, Gestational diabetes mellitus, Glyburide, Glibenclamide, Metformin, Treatment

Introduction

The incidence of diabetes among reproductive-aged women is rising globally. Consequently, the prevalence of overt diabetes in pregnancy and glucose intolerance in pregnancy (Gestational diabetes mellitus) has also risen.[1] Diabetes in pregnancy is associated with an increased incidence of adverse outcomes, for both mother and infant, if the glycemic control during pregnancy is not adequate.[2] Optimal glycemic control can be achieved with medications. Standard treatment for achieving adequate glucose levels is insulin therapy.[2] However, this therapy requires multiple daily injections of insulin, which may reduce patient adherence. Furthermore, its high cost may preclude treatment for some patients. Oral anti-diabetic agents (OAAs) have been investigated as an alternative to insulin therapy because of their ease of use and lower cost. This has resulted in increased use of OAAs, especially metformin and glyburide in pregnancy. Understanding the effectiveness of OAAs in pregnancy and its safety during pregnancy for both mother and fetus, and thereafter for development of offspring is essential for the care of women with diabetes in pregnancy. This article will concentrate on metformin and glyburide, since these two OAAs are the ones among OAAs, most commonly used during pregnancy. Acarbose is briefly discussed.

Diabetic therapy in pregnancy

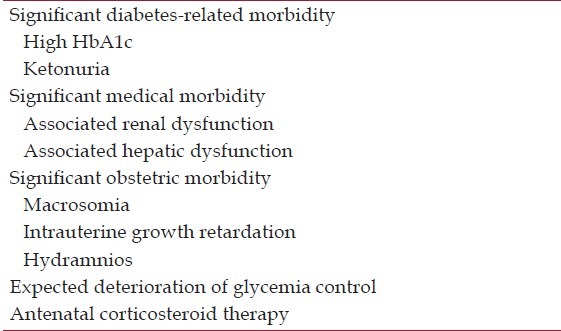

Drug of choice for management of diabetes in pregnancy has always been insulin. This choice has been decided on basis of unparalleled efficacy and safety as well as because of lack of any well-studied alternative. Studying any drug for safety and efficacy in pregnancy is always difficult due to ethical concerns. But some of the drugs, metformin and glyburide, have now reasonable amount of data to support their use in pregnancy, or at least to start a debate for usefulness and safety. As for any form of diabetes, medical nutrition therapy (MNT) remains the starting point of diabetic therapy in pregnancy. However, in pregnancy, need for rapid control is much desired. So, if a trial of MNT fails to achieve glycemic control within a week or less, diabetic therapy need to be escalated. Insulin remains the drug of choice in majority of women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). It is not necessary to give MNT trial in each and every case before putting patient on OAAs or insulin; women with high levels of hyperglycemia, which in the treating physician's opinion are unlikely to respond to MNT alone, may be started immediately on pharmacological treatment. The choice in such cases is usually insulin.[2] Women with significant obstetric morbidity (e.g., macrosomia, intrauterine growth retardation, hydramnios), expected deterioration of glycemia (e.g., planned antenatal corticosteroid therapy), and abnormal laboratory reports (e.g., ketonuria, increased fetal abdominal circumference on ultrasound) may also be started on insulin along with MNT [Table 1].

Table 1.

Absolute indications for insulin in pregnancy

Current place of OAAs in diabetes management

The use of oral anti-diabetic drugs in pregnancies is not recommended by the American Dental Association (ADA),[3] whereas UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines consider metformin and glyburide safe in pregnancy and lactation.[4] No OAA is approved by the US Food and Drug administration (FDA) for treatment of diabetes in pregnancy.[5] The Endocrine society has come out a very clear guidelines regarding use of OAAs (glyburide and metformin) in pregnancy.[2] They suggest that glyburide is suitable alternative to insulin therapy for glycemic control in women with gestational diabetes who fail to achieve sufficient glycemic control after a 1-week trial of MNT and exercise, except for those women with a diagnosis of gestational diabetes before 25-weeks gestation and for those women with fasting plasma glucose > 110 mg/dl (6.1 mmol/L), in which case insulin therapy is preferred. Regarding metformin, the suggestion for use is in those women with gestational diabetes, who do not have satisfactory glycemic control despite MNT, and who refuse or cannot use insulin or glyburide, and are not in the first trimester. The support behind glyburide as first alternative rather than metformin is controversial. Although metformin cross freely through the placenta, follow-up of MiG study had shown favorable effects on children in metformin group than in insulin group.[6] No such data is available for glyburide.

We discuss the data available for use of metformin and glyburide in pregnancy. Acarbose is briefly discussed. It should be kept in mind that little randomized evidence is available evaluating the use of OAAs in women with pre-existing diabetes mellitus/impaired glucose tolerance or previous gestational diabetes mellitus (planning a pregnancy or pregnant women with pre-existing diabetes mellitus) as per Cochrane review (till August 2010) and thereafter (till 25th February 2014).[7] So, discussion that follows is from data in women with GDM.

Metformin

Metformin is a bigaunide that functions by decreasing hepatic glucose output by inhibition of gluconeogenesis and enhanced peripheral glucose uptake. It also decreases intestinal glucose absorption and increases insulin sensitivity. It is metabolized by the CYP450 pathway, is excreted in the urine, and has a half-life of 6.2 hours.[8]

Rationale for use in pregnancy

Efficacy in pregnancy

In a recent meta-analysis of three randomized controlled studies comprising GDM patients, average fasting, and post-prandial glycemic levels were slightly lower in the metformin group than insulin group, but the difference was not statistically significant. There was no significant difference between the two groups in average HbA1c% level at gestational 36-37 week.[9] However, metformin failure was reported in up to 46.3% patients in largest of these studies. And in this study by Rowen et al., mean body mass index (BMI) of included patients was > 30 kg/m2.[10]

Safety

-

A.

Maternal: The average weight gain and pregnancy-induced hypertension rates in women after enrollment was significant lower in the metformin group than in insulin group in meta-analysis.[9] There was no significant difference in the pre-eclampsia rate between the two groups.[9] Average gestational ages at delivery was significantly lower in the metformin group. Pre-term birth rate was significantly more in the metformin group. There was no significant difference in the cesarean delivery rate between the two groups.[9]

-

B.

Fetal:

B.1 Placental Transport: Metformin has been shown to pass freely across the placenta.[11] Two in vivo studies measured maternal and cord blood samples in women taking metformin throughout pregnancy (850 mg twice daily in 15 women and 2,000 mg/day in 8 women).[11,12] The results of these trials showed that the fetus is exposed to concentrations as high or higher than those seen in the mother.

B.2 Teratogenicity: As previously mentioned, little randomized evidence is available evaluating the use of OAAs in women with pre-existing diabetes mellitus/impaired glucose tolerance. So, regarding teratogenicity, data is available from non-randomized studies primarily from two groups of women during pregnancy: a) pregnant women with polycystic ovary syndrome and b) pregnant women with diabetes, both pre-gestational and gestational diabetes.[8] The development of congenital anomalies that did occur in these studies was attributed to the presence of hyperglycemia during organogenesis and not to metformin itself. Therefore, metformin is not considered teratogenic.[8]

B.3 Fetal outcomes: In meta-analysis, the average birth weight of neonates was slightly lower in the metformin group as compared with the insulin group, but the difference was not statistically significant.[9] When compared with insulin group, the pooled result showed no significant difference between the metformin and insulin groups in large for gestational age (LGA) infants rate; the small for gestational age (SGA); hypoglycemia rate; in the incidence of shoulder dystocia; neonatal intensive-care unit (NICU) admission; respiratory distress syndrome; hyperbilirubinemia; in-birth defect rate; birth injury rate; phototherapy rate; and in the 5-min Apgar score.[9]

Metformin in women with type 2 diabetes in pregnancy (MiTy) trial is currently randomizing 500 women with type 2 diabetes in pregnancy to receive metformin or placebo in addition to their usual regimen of insulin (ClinicalTrials.gov). The primary outcome is a composite fetal outcome. This study will clarify whether adding metformin to insulin in women with type 2 diabetes will be beneficial to the mothers and infants.

B.4 During breastfeeding: Limited data from studies have demonstrated that breastfeeding is safe for the infant in women on metformin. The mean infant exposure to drug ranged from 0.11% to 0.65% of the weight normalized maternal dose.[13,14,15] This is below the 10% level of concern for breastfeeding. In addition, the blood glucose concentrations in infants 4 hours after a feeding were within the normal limit. Based on these findings, metformin use by breastfeeding mothers is safe.[13]

B.5 Long-term safety in offspring: Long-term safety data on infants whose mothers were treated with metformin is lacking. In first follow-up of the MiG (metformin in gestational diabetes) study, infants of women with GDM who had been randomized to receive either metformin or insulin during pregnancy have been examined at 2 years of age.[6] A healthier fat distribution was found in arm with metformin use in pregnancy. A study of offspring of women with Post-operative Cognitive Dysfunction (POCD) on metformin in pre-conception period and continued thereafter in pregnancy found normal weight and social and motor skills at 6 months of follow-up. There were no differences in height, weight, motor, or social skills between the neonatal groups at 18 months.[16]

It should be kept in mind that the earliest effects of diabetes in pregnancy on childhood obesity often do not become manifest until after 6-9 years of age.[17,18] Hence, longer follow-up studies will be required to determine the impact of in utero metformin exposure on the development of obesity and the metabolic syndrome in offspring.

Glyburide

Glyburide is a second generation oral sulfonylurea hypoglycemic agent. It acts by enhancing the release of insulin from the pancreatic beta cells, therefore for its action, some degree of pancreatic insulin-releasing function is required. It is well-absorbed following oral administration and is metabolized by the liver. The initial dose of glyburide is 2.5-5.0 mg once or twice a day with a maximum dose of 20 mg/day. The overall incidence of hypoglycemia from glyburide is 1-5%.[8]

Rationale for use in pregnancy

Efficacy in pregnancy

A systematic review which included three RCTs (478 participants; one trial was from India, which included 10 patients in glyburide group and 13 patients in insulin group) on comparison of glyburide with insulin found no differences in glycemic control including fasting blood glucose or 2-hour post-prandial glucose.[19] One RCT found significantly lower fasting blood glucose and 2-hour post-prandial glucose in insulin group as compared to glyburide group.[20] A recent prospective comparative study from India, which compared 32 patients each in glyburide and insulin group has found no significant difference in glycemic control.[21]

Safety

-

A.

Maternal: The rate of maternal hypoglycemia in the women who received insulin was higher (20%) as compared to glyburide (4%) in one study, but not in other two.[22,23,24] In meta-analysis of three RCTs including one from India, there were similar rate of cesarean delivery, with a range between 23-52%.[19] Overall, maternal outcomes were similar in women treated with glyburide compared with insulin in these studies.[25]

-

B.

Fetal

B.1 Placental Transport: The maternal-to-fetal transport of second generation sulfonylureas (glyburide) is significantly lower than the first-generation drugs (chlorpropamide and tolbutamide).[26] A 0.47-1.1% transport of glyburide from mother to fetus was demonstrated by Elliott using a single-cotyledon placental model.[27] In the randomized study of glyburide versus insulin in gestational diabetes, glyburide was not detected in the cord blood of any infant.[22]

B.2 Teratogenicity: In a well-designed study of 147 women (controlled for glycemic control) exposed to sulfonylureas (chlorpropamide, glyburide, or glipizide), there was no association between congenital anomalies and OAAs.[28] However, the maternal glycohemoglobin was independently associated with congenital anomalies. In a meta-analysis (10 studies on 471 exposed women to sulfonylureas and biguanides in first trimester), no significant difference was found in the rate of major malformations or neonatal death among women with first-trimester exposure to oral anti-diabetic agents compared with non-exposed women. The meta-analysis was limited by studies heterogeneity.[29]

B.3 Fetal health outcomes: Neonatal hypoglycemia was reported to be significantly high among those women who received glyburide compared with insulin in one RCT (odds ratio (OR): 11.67; 95% confidence interval (C.I.) 1.37-532.07), but not in the other two.[20,22,30] Birth weight was also significantly higher in same study.[30] There was no significant difference in LGA babies in two groups.[25]

B.4 During breastfeeding: There are limited studies on this aspect and that too with small number of women. In a study of eight women who had received a single oral dose of 5 or 10 mg glyburide, drug concentrations were measured in maternal blood and milk for 8 h after the dose.[31] In a separate study, five women were given a daily dosage (5 mg/day) of glyburide or glipizide, starting on the first postpartum day. Maternal blood and milk drug concentrations and infant blood glucose were measured 5-16 days after delivery.[32] Neither glyburide nor glipizide were detected in breast milk in either study and blood glucose was normal in the three infants (one glyburide and two glipizide) who were wholly breast-fed when the drug concentrations were at steady state. In addition, there were no neonatal cases of hypoglycemia.

It should be borne in mind, that the long-term effects of OAAs on breastfeeding infants have not yet been studied.

B.5 Long-term safety in offspring: There is lack of information on the long-term outcomes of the use of glyburide in pregnancy.

RCTs comparing metformin versus glyburide in GDM

Pubmed search revealed three RCTs comparing metformin versus glyburide in GDM, two were from same group of investigators (Silva et al.).[33,34,35] The larger of them is mentioned below.

Silva et al. evaluated the perinatal impact of metformin and glyburide in the treatment of GDM.[33] They studied 200 pregnant women with GDM who required adjunctive therapy to diet and physical activity. Patients were randomized to use metformin (n = 104) or glyburide (n = 96). They found significantly lower weight gain in metformin group. There was no significant difference in the percentage of cesarean deliveries, gestational age at delivery, number of newborns LGA, neonatal hypoglycemia, admission to intensive care unit, and perinatal death between the two groups. There was significant difference in birth weight of neonate (lower in metformin group) and neonatal blood glucose levels at the 1st hour after birth (lower in glyburide group).

Moore et al. compared the efficacy of metformin with glyburide for glycemic control in gestational diabetes.[35] Patients with gestational diabetes who did not achieve glycemic control on diet were randomly assigned to metformin (n = 75) or glyburide (n = 74) as single agents. In the patients who achieved adequate glycemic control, the mean fasting and 2-hour post-prandial blood glucose levels were not statistically different between the two groups. However, 26 patients in the metformin group (34.7%) and 12 patients in the glyburide group (16.2%) did not achieve adequate glycemic control and required insulin therapy (significant difference). The incidence of maternal hypoglycemia and pre-eclampsia was not different between the two groups. Cesarean deliveries were significantly higher with metformin. The mean birth weight of babies in the metformin group was significantly smaller than the mean birth weight of babies in the glyburide group. Other neonatal outcomes (LGA; neonatal hypoglycemia; NICU admission and shoulder dystocia) did not differ between the two groups.

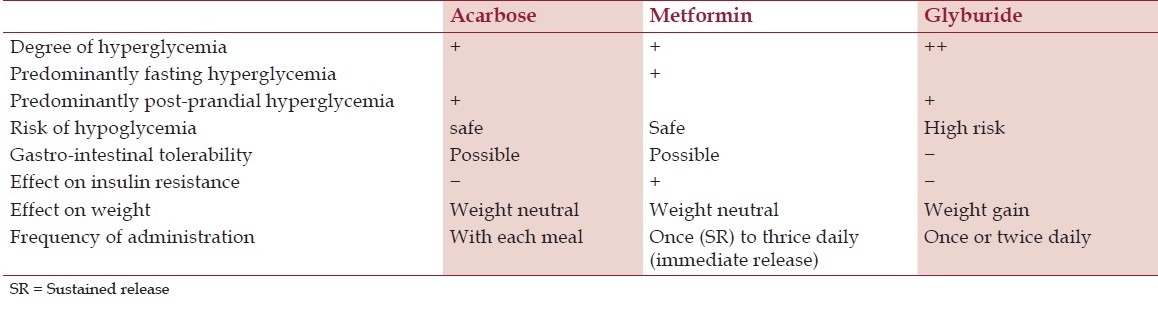

Acarbose

Acarbose reduce intestinal carbohydrate absorption by inhibiting the cleavage of disaccharides and oligosaccharides to monosaccharides in the small intestine, and reduces post-prandial hyperglycemia. Due to less than 2% absorption in the maternal circulation, these agents may have potential benefits in pregnancy.[36] Animal studies have suggested no harmful effects, but there are scanty data of its use in human pregnancy. There is no RCT available with acarbose regarding use of acarbose in pregnancy, and observational data is also limited. At present the use of a-glucosidase inhibitors is not currently recommended because of the lack of human pregnancy safety data.[36]

Pragmatic approach of use of OAAs in pregnancy

OAAs have a role to play at opposing ends of the spectrum of GDM. They can be used as mono-therapy in mild degrees of hyperglycemia, and as adjuvant to insulin in severe hyperglycemia which requires high doses of insulin for control. OAAs are not the drug of choice in women with GDM. However, they do have an important place in GDM management, provided they are used in a rational manner.

The choice of OAAs should be informed of a detailed knowledge of the concerned drug. It should be concordant with the pathophysiologic mechanisms which operate in GDM, and should target the main abnormality, viz., impaired glucose tolerance or insulin resistance. Recommendation for OAAs use in pregnancy should be in synchronous with guidelines framed for management of non-pregnant adults. Both maternal and foetal safety should be given equal importance.

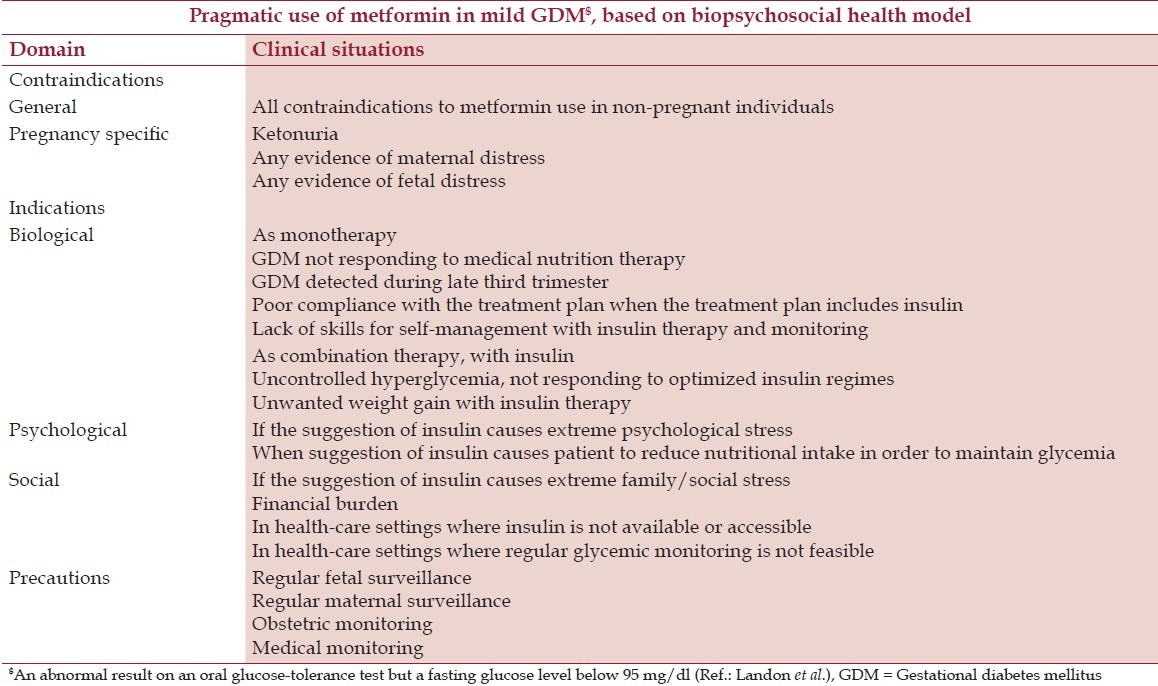

Prescription of any OAAs in pregnancy should be accompanied by an in-depth biopsychosocial assessment of the patient, explanation and discussion of potential limitations and side effects, and documentation of the reason why OAAs are being considered. We recently proposed the pragmatic use of metformin based on biopsychosocial model[Table 2].[37] Similar basis can be used for decision regarding use of glyburide.

Table 2.

Pragmatic use of metformin in mild GDM, based on biopsychosocial health model

The choice of OAAs in pregnancy depends upon various factors, which are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Glucose lowering drugs in pregnancy

Summary

Administration of an oral anti-diabetic agent instead of insulin appears to be tempting, but there is a paucity of data on the exposure of fetus to their mothers's OAAs during pregnancy as well as in infancy during breastfeeding. Insulin is not transferred through placenta as well into breast milk and therefore, remains the optimal anti-diabetic treatment during pregnancy and lactation. There is lack of RCTs evaluating the use of OAAs in women with pre-existing diabetes mellitus/impaired glucose tolerance. Both metformin and glyburide are not yet FDA approved for use in pregnancy. However, the results of RCTs comparing OAAs (metformin and glyburide) with insulin after first trimester in women with GDM has shown no significant differences in maternal and fetal health outcomes during pregnancy and short term outcomes in offspring. Therefore, patients of GDM who have mildly elevated blood glucose values, especially beyond 25 weeks of pregnancy,[2] or those who refuses to take insulin may be prescribed OAAs. However, the woman should be fully informed regarding lack of long-term safety data of use of OAAs in pregnancy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Guariguata L, Linnenkamp U, Beagley J, Whiting DR, Cho NH. Global estimates of the prevalence of hyperglycaemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103:176–85. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumer I, Hadar E, Hadden DR, Jovanovič L, Mestman JH, Murad MH, et al. Diabetes and pregnancy: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:4227–49. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitzmiller JL, Block JM, Brown FM, Catalano PM, Conway DL, Coustan DR, et al. Managing preexisting diabetes for pregnancy: Summary of evidence and consensus recommendations for care. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1060–79. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guideline Development Group. Management of diabetes from preconception to the postnatal period: Summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2008;336:714–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39505.641273.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berggren EK, Boggess KA. Oral agents for the management of gestational diabetes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;56:827–36. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182a8e0a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowan JA, Rush EC, Obolonkin V, Battin M, Wouldes T, Hague WM. Metformin in gestational diabetes: The offspring follow-up (MiG TOFU): Body composition at 2 years of age. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2279–84. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tieu J, Coat S, Hague W, Middleton P. Oral anti-diabetic agents for women with pre-existing diabetes mellitus/impaired glucose tolerance or previous gestational diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;10:CD007724. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007724.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Refuerzo JS. Oral hypoglycemic agents in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2011;38:227–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gui J, Liu Q, Feng L. Metformin vs insulin in the management of gestational diabetes: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowan JA, Hague WM, Gao W, Battin MR, Moore MP. MiG Trial Investigators. Metformin versus insulin for the treatment of gestational diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2003–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vanky E, Zahlsen K, Spigset O, Carlsen SM. Placental passage of metformin in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:1575–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charles B, Norris R, Xiao X, Hague W. Population pharmacokinetics of metformin in late pregnancy. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28:67–72. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000184161.52573.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briggs GG, Ambrose PJ, Nageotte MP, Padilla G, Wan S. Excretion of metformin into breast milk and the effect on nursing infants. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1437–41. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000163249.65810.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardiner SJ, Kirkpatrick CM, Begg EJ, Zhang M, Moore MP, Saville DJ. Transfer of metformin into human milk. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;73:71–7. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2003.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hale TW, Kristensen JH, Hackett LP, Kohan R, Ilett KF. Transfer of metformin into human milk. Diabetologia. 2002;45:1509–14. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0939-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glueck CJ, Goldenberg N, Pranikoff J, Loftspring M, Sieve L, Wang P. Height, weight, and motor-social development during the first 18 months of life in 126 infants born to 109 mothers with polycystic ovary syndrome who conceived on and continued metformin through pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1323–30. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feig DS, Moses RG. Metformin therapy during pregnancy: Good for the goose and good for the gosling too? Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2329–30. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silverman BL, Metzger BE, Cho NH, Loeb CA. Impaired glucose tolerance in adolescent offspring of diabetic mothers. Relationship of fetal hyperinsulinism. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:611–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicholson W, Bolen S, Witkop CT, Neale D, Wilson L, Bass E. Benefits and risks of oral diabetes agents compared with insulin in women with gestational diabetes: A systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:193–205. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318190a459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogunyemi D, Jesse M, Davidson M. Comparison of glyburide versus insulin in management of gestational diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract. 2007;13:427–8. doi: 10.4158/EP.13.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tempe A, Mayanglambam RD. Glyburide as treatment option for gestational diabetes mellitus. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2013;39:1147–52. doi: 10.1111/jog.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langer O, Conway DL, Berkus MD, Xenakis EM, Gonzales O. A comparison of glyburide and insulin in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1134–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010193431601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anjalakshi C, Balaji V, Balaji MS, Seshiah V. A prospective study comparing insulin and glibenclamide in gestational diabetes mellitus in Asian Indian women. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;76:474–5. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bertini AM, Silva JC, Taborda W, Becker F, Lemos Bebber FR, Zucco Viesi JM, et al. Perinatal outcomes and the use of oral hypoglycemic agents. J Perinat Med. 2005;33:519–23. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2005.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhulkotia JS, Ola B, Fraser R, Farrell T. Oral hypoglycemic agents vs insulin in management of gestational diabetes: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:457.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elliott BD, Schenker S, Langer O, Johnson R, Prihoda T. Comparative placental transport of oral hypoglycemic agents in humans: A model of human placental drug transfer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:653–60. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(94)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elliott BD, Langer O, Schenker S, Johnson RF. Insignificant transfer of glyburide occurs across the human placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:807–12. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90421-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Towner D, Kjos SL, Leung B, Montoro MM, Xiang A, Mestman JH, et al. Congenital malformations in pregnancies complicated by NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1446–51. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.11.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gutzin SJ, Kozer E, Magee LA, Feig DS, Koren G. The safety of oral hypoglycemic agents in the first trimester of pregnancy: A meta-analysis. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;10:179–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silva JC, Bertini AM, Taborda W, Becker F, Bebber FR, Aquim GM, et al. Glibenclamide in the treatment for gestational diabetes mellitus in a compared study to insulin. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2007;51:541–6. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302007000400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feig DS, Briggs GG, Kraemer JM, Ambrose PJ, Moskovitz DN, Nageotte M, et al. Transfer of glyburide and glipizide into breast milk. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1851–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.8.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glatstein MM, Djokanovic N, Garcia-Bournissen F, Finkelstein Y, Koren G. Use of hypoglycemic drugs during lactation. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:371–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silva JC, Fachin DR, Coral ML, Bertini AM. Perinatal impact of the use of metformin and glyburide for the treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus. J Perinat Med. 2012;40:225–8. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2011-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silva JC, Pacheco C, Bizato J, de Souza BV, Ribeiro TE, Bertini AM. Metformin compared with glyburide for the management of gestational diabetes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;111:37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore LE, Clokey D, Rappaport VJ, Curet LB. Metformin compared with glyburide in gestational diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:55–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c52132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holt RI, Lambert KD. The use of oral hypoglycaemic agents in pregnancy. Diabet Med. 2014;31:282–91. doi: 10.1111/dme.12376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalra B, Gupta Y. Pragmatic use of metformin in pregnancy based on biopsychosocial model of health. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17:1133–5. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.122654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]