Abstract

Background:

Although nurses acknowledge that spiritual care is part of their role, in reality, it is performed to a lesser extent. The purpose of the present study was to explore nurses’ and patients’ experiences about the conditions of spiritual care and spiritual interventions in the oncology units of Tabriz.

Materials and Methods:

This study was conducted with a qualitative conventional content analysis approach in the oncology units of hospitals in Tabriz. Data were collected through purposive sampling by conducting unstructured interviews with 10 patients and 7 nurses and analyzed simultaneously. Robustness of data analysis was evaluated by the participants and external control.

Results:

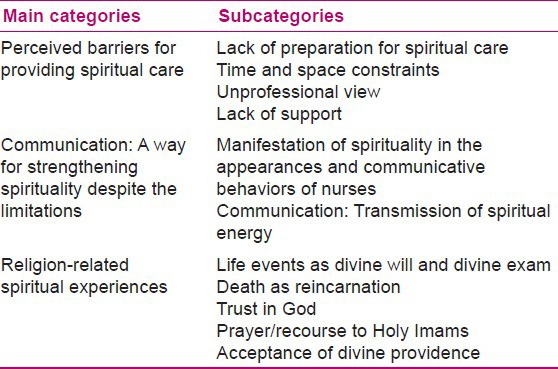

Three categories emerged from the study: (1) “perceived barriers for providing spiritual care” including “lack of preparation for spiritual care,” “time and space constraints,” “unprofessional view,” and “lack of support”; (2) “communication: A way for Strengthening spirituality despite the limitations” including “manifestation of spirituality in the appearances and communicative behaviors of nurses” and “communication: Transmission of spiritual energy”; and (3) “religion-related spiritual experiences” including “life events as divine will and divine exam,” “death as reincarnation,” “trust in God,” “prayer/recourse to Holy Imams,” and “acceptance of divine providence.” Although nurses had little skills in assessing and responding to the patients’ spiritual needs and did not have the organizational and clergymen's support in dealing with the spiritual distress of patients, they were the source of energy, joy, hope, and power for patients by showing empathy and compassion. The patients and nurses were using religious beliefs mentioned in Islam to strengthen the patients’ spiritual dimension.

Conclusions:

According to the results, integration of spiritual care in the curriculum of nursing is recommended. Patients and nurses can benefit from organizational and clergymen's support to cope with spiritual distress. Researchers should provide a framework for the development of effective spiritual interventions that are sensitive to cultural differences.

Keywords: Cancer, Iran, religion, spiritual interventions, spiritual care

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is one of the diseases with a growing incidence,[1] which alters the normal life of patients and creates a sense of fear and anxiety in them.[2] Cancer diagnosis and its prolonged and invasive treatments take the ability away from the patients to enjoy life[3,4] and increase their spiritual needs.[5] Spirituality is associated with both culture and religion and influences our understanding of health and disease.[6] In the case of a life crisis, spirituality arises as a serious issue for both patients and their families;[7] in other words, spirituality is a dimension through which cancer patients can fight the sense of fear and loneliness throughout their disease,[6] because spiritual and religious faith creates a kind of world view which is associated with optimism and hope.[8] Lin and Bauer-Wu believe that if spiritual distress of patients is reduced, and spiritual care is provided, then the patients may cope with their disease and better pass through the end stages of life.[9]

Spirituality can be viewed as a quality which goes beyond the religious affiliation that strives for answers about the infinity and comes into focus when the person faces emotional stress, physical illness, or death. In Islam, there is no distinction between religion and spirituality. The religion is embedded under the umbrella of spirituality and there is no spirituality without religious thoughts and practices, and the religion provides the spiritual path for rescue and a clear way to live. Muslims embrace the acceptance of the divine and they seek meaning, purpose, and happiness in worldly life and hereafter in the light of application of the orders in Qur’an and the guidance of Prophet Muhammad,[10,11] although in the western world spirituality is a more comprehensive concept than religion. However, there is consensus that spirituality embraces philosophical thoughts about life, its meaning and purpose,[12] and is a way through which human beings recognize the exalted meaning and value of their lives. Accordingly, many people have turned to religion and some others seek comfort in spiritual concepts outside the realm of organized religion.[13]

Religion and spirituality play a central role in patients’ coping with cancer, and providing comfort, hope, and meaning to them. As spirituality seems to be a universal concern in patients suffering from advanced stages of cancer, it is important that psychosocial interventions are developed to address this concern: “Future research is needed to further explore the different ways that patients conceptualize spirituality and to develop spiritually-based treatments that are not “one size fits all.””[14] Patients with cancer who are close to death suffer from spiritual grief to find meaning and purpose in life and death and what happens after death.[8] Meeting the psychosocial, emotional, and spiritual needs of people with cancer presents a real challenge to health professionals and, in particular, nurses, who spend more time with patients when they access health services.[15] The challenge for nurses lies in meeting the mental, social, cultural, spiritual, and developmental needs arising from patients’ emotional responses to their diagnoses and complexities of treatment.[16]

In practice, nurses are increasingly encouraged in caring the whole person, including the four domains: Physical, mental, social, and spiritual. Of these four domains, spiritual domain is the most neglected in daily nursing practice.[17] Although recent developments in health care show a growing awareness of the importance of patients’ spiritual needs,[18] the health professions have largely followed a medical model which seeks to treat patients by focusing on medicines and surgery and gives less importance to beliefs and to faith in healing.[17] While the nurses acknowledged that spiritual care was a part of their role, in reality, they responded less well and most studies attributed this to nurses feeling inadequately prepared to give spiritual care and respond to patients’ spiritual needs.[19,20,21] Some nurses reported responding personally, e.g. by listening/being there, but many were uncomfortable in doing so.[22]

The results in this case are different. Arries proposed that caregivers can reinforce patients’ spiritual dimension while respecting their human dignity, accepting and understanding them, as well as maximizing their capability to control themselves.[23] Rustoen et al. in 1998 emphasized on the interventions such as believing in yourself and your abilities, responding to patients’ feelings, communication with others, enabling patients to be engaged in care giving, and paying attention to the patients’ beliefs and values in communication processes to reinforce hope in patients.[24] Studies suggest that spiritual care can be promoted if nurses are aware of their spiritual beliefs;[20,22,25] they link with other professionals, e.g. chaplains/clergy;[25,26] the environmental conditions, e.g. nurse shortage, time allocated to patient, and/or resources, are corrected;[27] and are educated about spiritual care.[28]

Spirituality is a subjective and abstract concept that depends on the culture and context, so qualitative researches need to explore the patients’ spiritual experiences during nursing care[29] and to understand the ways in which they may be used for spiritual interventions.[14]

Religion as a way to answer the fundamental questions about life and death issues has been proposed in spiritual care models,[30] which, in the Islamic context of Iran, have played a special role in provision of spiritual care. On the other hand, according to the literature, nurses’ knowledge about spiritual care is limited;[31] there are a few studies on spiritual care for patients with cancer in Iran[32] and further research about the spiritual aspects of care in different cultural contexts is needed.[31] Few studies have been done on the spiritual interventions using qualitative research methods with respect to the experiences of both patients and nurses. Moreover, because of differences in background and clinical context, experiences of patients with cancer and their nurses of the interventions provided during spiritual care may be different from other countries and findings in other cultures and thus are not applicable in Iran. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore nurses’ and patients’ experiences on the conditions of spiritual care and spiritual interventions in the oncology units of Tabriz.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The qualitative conventional content analysis approach was used to explore nurses’ and caner patients’ experiences on the conditions of spiritual care and spiritual interventions used in oncology units. Study participants included 10 patients and 7 nurses who were selected through purposive sampling. The inductive approach is recommended to explain and interpret the data and elaborate the dominant and major themes as the essence of participants experiences at the conditions of lack of enough knowledge about a phenomenon.[33]

Setting and participants

In this study, in order to explore participants’ experiences of spiritual care and spiritual interventions in oncology units, qualitative content analysis approach was used. Participants (7 nurses and 10 patients) were chosen based on purposive sampling and saturation principles using the following inclusion criteria for patients: (1) Age at least 20 years and (2) not suffering from mental disorders according to their records. The criteria for nurses were: (1) Having at least 1 year of nursing experience in the oncology unit and (2) with at least a bachelor's degree in nursing. This study was conducted in two main oncology centers in Tabriz which were Ali-Nasab Hospital and Shahid Ayatollah Qazi Tabatabaee hospital.

Data collection

Unstructured interviews were conducted for gathering data. In addition, behaviors of patients and their nurses were observed in the natural environment during nursing care, chemotherapy, or other situations, and field notes were prepared in the same environment. The interviews that lasted between 30 and 95 min started with more general questions; however, the questions became more detailed with the progress of the interviews and simultaneous analyses of data and according to the findings of study. The major foci of the questions were “Can you explain the spirituality care in oncology unit according to your experience? What intervention is done to influence patients’ spirituality?” Some participants were interviewed twice (in two separate parts, in order to improve the depth of data gathering and to reach saturation in the subcategories and categories of the study). Data collection was done from May 2012 to February 2013 using unstructured interviews and consisted of 24 interviews with 17 participants. Maximum variation in sampling was considered with the participants’ gender, age, nursing experiences, and diagnosis of patients.

Data analyses

The interviews were recorded on tapes. The interviews were subsequently transcribed, read, re-read, and analyzed by the research team. The overt and covert messages in the transcribed texts were analyzed by qualitative content analyses approach. The approach focused on subject and context, and differences and similarities within categories and subcategories.[34] The researcher transcribed the interviews and field notes verbatim and read them all several times to obtain full understanding of the data. Whole interviews and field notes were considered as units of analysis. Words, sentences, and paragraphs considered as the meaning units were condensed according to their content and context. The condensed meaning units were abstracted and labeled with codes. Codes were sorted into subcategories and categories based on comparisons regarding their similarities and differences. Discussion about the process of coding and categorizing the data frequently continued until consensus was achieved on it.[34,35] In this study, we obtained 11 subcategories and three main categories. To increase the validity of the data, the codes were compared, and the differences were discussed and re-evaluated in group research until shared codes and categories were created. Throughout the entire analyses process, subcategories and categories were compared with the original texts until consensus among all authors was attained.

Credibility and conformability was established through member checking. The report of the analyses was given to the participants in order to get assurance that the researchers had portrayed their real world in codes and extracted categories. In addition, parts of two interviews that were converted to text had been sent to two expert researchers in the qualitative research on cancer. The agreement between the external coders with codes of researchers was measured using Holsti method,[36] which gave an average of 78%.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Hematology and Oncology Research Center affiliated to Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, which corroborated its ethical consideration. The ethical considerations of the study were anonymity, informed consent, withdrawal from the study, and recording permission. Prior to the study, participants were informed verbally about the aim of the study; it was mentioned that they could withdraw from the study at any time; then informed consent was obtained. To protect the privacy, confidentiality, and the identity of the participants, interviews were conducted only with the participation of the interviewer and the interviewee.

RESULTS

The patients were aged 20-61 years and consisted of four women and six men. They were diagnosed with and were being treated for leukemia, breast cancer, colon cancer, lymphoma, sarcoma, stomach cancer, and liver cancer, and all had experienced chemotherapy. All the participants were Muslims. Four participants had the experience of hospitalization and receiving treatment in the Cancer Institute of Imam Khomeini Hospital of Tehran. All the nurses participating in the study had a bachelor's degree, and their work experience in the oncology unit ranged from 1½ to 29 years. There was just one male. Two of them were head nurses. The codes extracted from the interviews were categorized into three categories as follows: (1) “Perceived barriers for providing spiritual care” including “lack of preparation for spiritual care,” “time and space constraints,” “unprofessional view,” and “lack of support”; (2) “communication: A way for strengthening spirituality despite the limitations” including “manifestation of spirituality in the appearances and communicative behaviors of nurses” and “communication: Transmission of spiritual energy”; and 3) “religion-related spiritual experiences” including “life events as divine will and divine exam,” “death as reincarnation,” “trust in God,” “prayer/recourse to Holy Imams,” and “acceptance of divine providence” [Table 1]. These categories refer to the issue that despite the limitations experienced by the participants and their disorganized conditions in the health care environment, nurses in a non-supportive work environment communicate with their patients in an empathic, compassionate, and kind manner and strengthen their spiritual beliefs based on religion to help them in dealing and coping with disease problems. Three categories and sub-categories will be discussed in this paper.

Table 1.

Main categories and subcategories that emerged from the data analyses

Perceived barriers for providing spiritual care

This category explains restrictions found in the oncology units for spiritual care according to participants’ experiences.

Lack of preparation for spiritual care

Insufficient awareness of spiritual care was mentioned by many participants. The participating nurses were not familiar with the systematic approach for assessing and addressing patients’ spiritual needs. Most of them believed that only long-term relationships with patients would make them understand the patients’ spiritual needs; otherwise, they had not received any training to assess the patients’ spiritual dimension and did not have the required skills for spiritual care.

Participant 11 (a nurse): “It is true that the patient's spiritual beliefs can be effective in his/her coping, but we cannot really assess the patient's spiritual dimension. The problem is in the education system that does not provide us the skills required for this task ….”

Time and space constraints

Although nurses were aware of this fact that the caring environment should be prepared for the patients to express their spiritual needs and do their religious practices such as saying prayers (Namaz), lack of suitable and private space and also lack of time were among the barriers that prevented it.

Participant 10 (a patient): “I could not say my prayers (Namaz) on time mostly because of chemotherapy …. For example, once there was the possibility for saying prayer before starting chemotherapy, but the nurse was in a hurry and I could not do it …, I want a private room to make my prayer and implore the Lord …. But there was no place in the ward and even anyone to ask for my spiritual needs.”

Nurses faced with being overworked and worked extra shifts due to shortage of nurses in oncology, which affected the detection and response to the whole needs of patients.

Participant 10 (nurse): “Workload of oncology is horrible. Due to the high workload, often routine care is a priority and there isn’t an opportunity to support the patient emotionally and spiritually.”

Unprofessional view

In addition to lack of time and heavy workload, the lack of holistic view and emphasis on routine-based approach made the nurses mostly focus on physical care regardless of the emotional and spiritual needs of patients.

Participant 1 (a patient): “Well, nurses emphasize more on routine works; most of them just gave medications, check blood pressure. Even during chemotherapy they did not say anything or ask any questions…. They (nurses) took care of my body, but my soul was more important.”

Lack of support

The participants in our study were not supported by responsible authorities in the organization or society for getting spiritual care and they did not know how to manage the situation when dealing with the patients’ spiritual distress. They perceived the absence of clergymen for providing spiritual support for patients and nurses as a challenge.

Participant 8 (a nurse): “I worked for 15 years in oncology; during this time, I have never seen anyone in the organization speaking of death and life to the patient…. There should be a relationship between the clergymen and hospital authorities, but there is none actually…. We cannot manage the patient's fear, we have not been trained in this field and we are not familiar with spiritual issues, we are stressed out, but no one supports us….”

Communication: A way for strengthening spirituality despite the limitations

This category shows that long-term nurse–patient interactions have a positive effect on the spiritual dimension of participants and they (nurses/patients with cancer) strengthen the spirituality of each other. It means that nurses who effectively communicate with their patients have more opportunity to provide spiritual care in a limited caring environment.

Manifestation of spirituality in the appearances and communicative behaviors of nurses

Nurses participating in the study spoke about their experiences of spiritual growth as forgiving, care giving with patience, and seeking God's satisfaction within people's satisfaction. This growth was reflected in the appearance and therapeutic communication behaviors of them.

Participant 2 (a nurse): “When you are in contact with patients with cancer, you will not love material world anymore, you will forgive easily, and you will learn patience from them…. Working in the oncology is self-examination, a divine test. What is important in it is how to behave as human beings … if the patient is satisfied, God will be satisfied.”

Based on participating patients’ opinion, the nurses’ spiritual aspect was manifested in their relationship with the patients as warmth, passion and joy, empathy, encouragement, caring, and treating patients kindly. With such characteristics, the nurses were sources of energy, comfort, hope, and power for the patients.

Participant 9 (a patient): “Those who are kinder influence spiritually on us and their passion and joy are transferred to us. We influence each other's spirits … when I get better, they become happy … their happiness and positive spirit lift my spirit.”

Communication: Transmission of spiritual energy

Nurses transfer this spiritual energy to their patients while interacting with them.

Participant 1 (a patient): “Love and affection of a nurse are like a spiritual energy flow. I found the power of them strong. When a nurse deals angrily with a patient, the patient becomes weak and helpless.”

Religion-related spiritual experiences

Participants of the study had beliefs about life, death, and disease, which are rooted in the teachings of Islam, and they had attained these beliefs in the context of their lives with family, people, and community like a hidden curriculum. Nurses know this issue and use it so that they could strengthen these beliefs in patients to help them deal and cope with problems of the disease.

Life events as divine will and divine exam

The results of the present study showed that belief in God was so deeply rooted in the patients’ heart that even in the first days of diagnosis; they considered it as a divine will and an opportunity to be examined in difficulties.

Participant 10 (a patient): “I think it was the trust in God that enabled me to cope with the illness. When doctor told me I have lymphoma, believe me, it did not bother me. I told myself I trust in God, maybe God wants to examine me in difficulties…. I was born one day and I should leave this world one day, too. It's God's will if I should die with cancer.”

Participant 8 (a nurse): “I’m using their religious beliefs. Say, we are Muslims; we must accept death, as we welcome the birth…. They are both the divine will.”

Death as reincarnation

The results of this study showed that patients’ spiritual dimension is not improved due to death approaching them; what makes a patient become strong is the sense of getting closer to God. Accordingly, death is only opening of the door between the patient and God.

Participant 3 (a patient): “I felt strong. When I saw myself at the end of the road, I knew that this place on which I was standing was not a hard place. When you get stronger, you no longer fear. You’ll see that dying is not difficult…. The end of the road means God and you’ll understand that there is nothing except God at the end of the road.”

Trust in God

If belief in God as a Supreme Power is identified and reinforced among patients, trust in God can lead to more coping responses in the patients toward diseases and their problems.

Participant 8 (a nurse): “Before the chemotherapy, I speak with them (patients) in terms of spiritual and religious affairs; I reinforce their relationship with God, trust in God….”

Participant 1 (a patient): “They (nurses) tell that God is great, do not miss God, God is first, then doctors. We and doctors are all tools. The main work is done by God…. Put your trust in God….”

The patients, their families, and even the nurses frequently prayed to God and demanded Him to heal patients through recourse to Holy Imams. They wanted Him to help patients tolerate hardships and achieve well-being.

Prayer/recourse to Holy Imams

Participants frequently pray for patients’ healing and for this purpose, seek healing from God either directly or indirectly through recourse (tawassul) to Holy Imams (holy grandsons of the Prophet of Islam as a channel of connection between creatures and the creator).

Participant 14 (a patient): “Yesterday, my nurse said, ‘I avow to Hazrat Zahra (daughter of Prophet Muhammad) to help you get better….’ The fact is that they (nurses) are praying for us and recourse to Holy Imams for our healing….”

Acceptance of divine providence

One of the strategies for reinforcing spirituality dimension was the emphasis on the faith in the divine providence, i.e. the belief that each person has a destiny that God has ordained and the fate of individuals in health and disease is in God's hands. Reinforcement of this belief in patients and their families was frequently done to prevent them from getting dejected.

Participant 3 (a patient): “Once I told my nurse that I think that I have reached at the end of line. But he/she told me, ‘Look, everything is in God's hands. We may live for 4 years or for 40 years. It is possible that you do not die because of this disease. Note that sometimes healthy people die in a bus accident. The life and death are in God's hands.’”

Participant 2 (a nurse): “I told the truth to the patient's relatives…. I told them that the patient has this disease and everyone has a destiny. One may die in a plane crash, and the other in an earthquake…. You’re a believer, you are a Muslim; you should not complain about the destiny of your patient … death is another birth for Muslims….”

DISCUSSION

This study explores nurses’ and patients’ experiences about the conditions of spiritual care and spiritual interventions in the oncology units of Tabriz. The first main category of the study showed that conditions governing the spiritual care in the oncology units of Tabriz are unorganized. Nurses believe that their ability for providing spiritual care is inadequate and based on their viewpoints, lack of adequate training, lack of support from clergymen to resolve patients’ spiritual distress, and inappropriate working environment are the main reasons for their lack of preparation to provide spiritual care. In the present study, inappropriate care environment and lack of private space and time allocation for religious practices prevented spiritual reinforcement and developed the assumption in patients that enough attention is not being paid to their spiritual needs. This lack of preparation in nurses can be related to their basic training, which involves less discussion about the issues of spirituality in nursing textbooks.[37] On the other hand, in this dimension of caring, neglecting the role of professional clergymen that could result from the historical conflict between science and religion is always seen.[38,39] Only in a good working environment and a facilitating care environment, the nurses can support their patients through understanding their spiritual experiences and prepare the circumstances of time and place for their spiritual practices and respect their spiritual beliefs.[40] The findings of this study show that based on the participants’ viewpoints, spiritual care can be provided in the context of an effective communication in which nurses could transfer joy, passion, affection, and empathy in dealing with patients and pray for their health, be patient when they care for them, and pay attention to the spiritual needs of their patients. The findings are in line with study of Iranmanesh et al. which revealed caring relationship as an attempt to meet the spiritual needs of patients with cancer.[41]

On the other hand, routine and duty-oriented care prevents them from paying attention to all the needs of patients, such as spiritual and emotional needs. This condition is dominated in Iran, where still the cultural and organizational structure is physician-centered and negatively affects the profession of nursing.[42] In 2010, Deal reported that spiritual care involves using a patient-centered approach instead of a provider-centered approach.[43]

Participants in this study mentioned the mutual influence of each other's spirituality so that spiritual energy is exchanged between them. Increased spirituality, which was described by the study participants as spiritual energy, is transferred through effective communication between patients with cancer and nurses. This energy is encoded in the form of empathy, joy, kindness, and compassion. The results of the study of Mahon-Graham indicated that nurses who have strong spiritual power transfer power, sense of comfort, and peace, despite their illness.[44] They help their patients get connected to the Supreme Power[43] and to grow their spirituality over time through relationship with God and living according to His commands as well as through relationship with others.[45]

In this study, nurses experienced spiritual growth as a stage in their professional development where in interaction with patients makes them strive to help patients and to advocate them through transfer of emotions, honestly dealing with the patients and encouraging them to trust in God and to accept God's will. The findings of Yong and Sun-Seu showed that nurses experience awakening and spiritual maturity in an ascending and gradual manner.[46] Communication with patients leads nurses to see their value as an effective nurse,[41] which is effective in providing spiritual care, so that it makes them invite patients and their family members to pray, to read spiritual books, to talk with others about spiritual issues, and to emphasize not to forget God.[44]

The third category of this study revealed that the participants mostly use the strategies that are rooted in Islamic culture to cope with their disease. The belief that life and death are in God's hands made the patients feel that cancer is a opportunity for them to be examined by God in difficulties and it is a divine pr ovidence, which is treated by them as an important factor in coping with cancer. According to the teachings of Islam, God asks humans to be patient in dealing with hardships and notes that everybody's return is toward Him. In verse 156 of Surah Baqara in the Qur’an (Muslims’ holy book), He says, “Those who are patient when they face with the hardships say we have come to this world by God's will and shall return to Him.” Although in Western culture it is believed that fatalism can reduce preventive behaviors, screening tests, and follow-up visits in patients,[47,48] a study conducted by Harandi et al. showed that despite the belief of many cancer patients about cancer as a will of God, they actively pursue medical treatments.[49] Walker et al. also demonstrated that fatalism has a positive correlation with the adherence to medication regimens, diets, and activities, as well as screening tests.[50] Cultural and religious differences between Muslim and Western countries can explain these differences, because spirituality in Islam is based on the Qur’an, and Muslims treat and mention worship and live according to the commandments of God in the Qur’an as the spiritual sources in the development of their spiritual life.[51]

Participants in this study consider God as the source of their power, and enhance their strength for fighting the disease and controlling the fear of death through trust in God and getting closer to Him. In some other studies, patients considered God to be the source of their power and peace, and also considered their power in enduring hardships of cancer as an opportunity for growing spiritually and getting closer to God.[49,51]

Based on the results of study, honesty and empathy in communication, strengthening relationships with God and trusting in God as the Supreme Power, recourse to Holy Imams for asking God to heal them are among spiritual coping sources. According to the teachings of Islam, what is meant by recourse is resorting to the special friends of Allah (the holy grandsons of the Prophet of Islam) in requesting God to fulfill one's needs.[52] In the view of patients of the study by Rahnama et al., spirituality can be defined in a religious context, wherein the religious resources that were used by the patients included worship practices and religious appealing through having faith in God and relying on Imams (Prophet Mohammad's household).[53] Participants in the study of Herbert et al. felt that it was important that their physicians develop their patients’ willingness for participating in the spiritual discussions through empathy and strong interpersonal communication skills.[54] In the study of Fallah et al., the participants believed that the mechanisms of prayer, trust in God, forgiveness, kindness, and trust were helpful in coping with their problems.[55] It is clear that cultural aspects play an important role in the perception of life experiences.[56] On the other hand, in Iran, religious beliefs play a special role in dealing with stressful events.

This study is based on the experiences of patients and nurses, and as the family members exert their influence on this issue, their non-participation is one of the limitations of this study. Moreover, the research findings are related to Tabriz and cannot be generalized to other areas and cultures in Iran.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this study showed the influence of spirituality, especially religion, in shaping the meaning of life and death and exploring the nursing interventions for meeting the spiritual needs of patients with cancer. Findings of our study show that researchers should provide a framework for the development of effective spiritual interventions that are sensitive to cultural and religious differences. Although all participants acknowledged the importance of spiritual care, existence of main obstacles in this area shows the necessity of paying attention to the issue of spirituality in the nursing curriculum and content of their training programs. In addition to improving communication skills for effective spiritual care, the health system should develop its relationship with clergymen to be able to use the potential spiritual force of this part of society in order to support patients and nurses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The researchers appreciate patients, nurses, managers, and administrators of Ali-Nasab and Shahid Ayatollah Qazi Tabatabaee hospitals. Approval to conduct this research with no. 5/74/474 was granted by the Hematology and Oncology Research Center affiliated to Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This research was conducted by financial support of Hematology and Oncology Research Center affiliated to Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Project number: 5/74/474).

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jabaaij L, Van den Akker M, Schellevis FG. Excess of health care use in general practice and of comorbid chronic conditions in cancer patients compared to controls. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adelbratt S, Strang P. Death anxiety in brain tumour patients and their spouses. Palliat Med. 2000;14:499–507. doi: 10.1191/026921600701536426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang CY, Schnoll RA. Impact of psychological distress on outcomes in cancer patients. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2002;2:495–506. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischbeck S, Maier BO, Reinholz U, Nehring C, Schwab R, Beutel ME, et al. Assessing somatic, psychosocial, and spiritual distress of patients with advanced cancer: Development of the advanced cancer patients’ distress scale. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30:339–46. doi: 10.1177/1049909112453640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearce MJ, Coan AD, Herndon JE, 2nd, Koenig HG, Abernethy AP. Unmet spiritual care needs impact emotional and spiritual well-being in advanced cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:2269–76. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Surbone A, Baider L. The spiritual dimension of cancer care. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;73:228–35. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penman J, Oliver M, Harrington A. The relational model of spiritual engagement depicted by palliative care clients and caregivers. Int J Nurs Pract. 2013;19:39–46. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McClain-Jacobson C, Rosenfeld B, Kosinski A, Pessin H, Cimino JE, Breitbart W. Belief in an afterlife, spiritual well-being and end-of-life despair in patients with advanced cancer. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26:484–6. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin HR, Bauer-Wu SM. Psycho-spiritual well-being in patients with advanced cancer: An integrative review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44:69–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheraghi MA, Payne S, Salsali M. Spiritual aspects of end-of-life care for Muslim patients: Experiences from Iran. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2005;11:468–74. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2005.11.9.19781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rassool GH. The crescent and Islam: Healing, nursing and the spiritual dimension. Some considerations towards an understanding of the Islamic perspectives on caring. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1476–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farsi Z, Salsali M. Concept of care and nursing metaparadigms in Islam. (8-21).Teb va Tazkieh. 2007:66–67. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McClain CS, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W. Effect of spiritual well-being on end-of-life despair in terminally-ill cancer patients. Lancet. 2003;361:1603–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13310-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stein EM, Kolidas E, Moadel A. Do spiritual patients want spiritual interventions?: A qualitative exploration of underserved cancer patients’ perspectives on religion and spirituality. Palliat Support Care. 2013;6:1–7. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513000217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCaughan E, Parahoo K. Medical and surgical nurses’ perceptions of their level of competence and educational needs in caring for patients with cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2000;9:420–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2000.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frost MH, Brueggen C, Mangan M. Intervening with the psychosocial needs of patients and families: Perceived importance and skill level. Cancer Nurs. 1997;20:350–8. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199710000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan MF. Factors affecting nursing staff in practising spiritual care. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:2128–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundmark M. Attitudes to spiritual care among nursing staff in a Swedish oncology clinic. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:863–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahmoodishan G, Alhani F, Ahmadi F, Kazemnejad A. Iranian nurses’ perception of spirituality and spiritual care: A qualitative content analysis study. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2010;3:6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ross L. Spiritual care: The nurse's role. Nurs Stand. 1994;8:33–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stranahan S. Spiritual perception, attitudes about spiritual care, and spiritual care practices among nurse practitioners. West J Nurs Res. 2001;23:90–104. doi: 10.1177/01939450122044970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor EJ, Amenta M, Highfield M. Spiritual care practices of oncology nurses. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22:31–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arries EJ. Editorial comment. Is an African nursing ethics possible? Nurs Ethics. 2009;16:681–2. doi: 10.1177/0969733009343138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rustoen T, Wiklund I, Hanestad BR, Moum T. Nursing intervention to increase hope and quality of life in newly diagnosed cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 1998;21:235–45. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199808000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross LA. Spiritual aspects of nursing. J Adv Nurs. 1994;19:439–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuuppelomaki M. Spiritual support for terminally ill patients: Nursing staff assessments. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10:660–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2001.00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ross L. Spiritual care in nursing: An overview of the research to date. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:852–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baldacchino DR. Nursing competencies for spiritual care. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:885–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Momennasab M, Moattari M, Abbaszade A, Shamshiri B. Spirituality in survivors of myocardial infarction. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2012;17:343–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Govier I. Spiritual care in nursing: A systematic approach. Nurs Stand. 2000;14:32–6. doi: 10.7748/ns2000.01.14.17.32.c2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ekedahl MA, Wengstrom Y. Caritas, spirituality and religiosity in nurses’ coping. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2010;19:530–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yousefi H, Abedi HA, Yarmohammadian MH, Elliott D. Comfort as a basic need in hospitalized patients in Iran: A hermeneutic phenomenology study. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65:1891–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borhani F, Alhani F, Mohammadi E, Abbaszadeh A. Professional Ethical Competence in nursing: The role of nursing instructors. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2010;3:3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rourke L. Methodological Issues in the Content Analysis of Computer Conference Transcripts. Int J Artif Intell Educ. 2001;12:8–22. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McEwen M. Analysis of spirituality content in nursing textbooks. J Nurs Educ. 2004;43:20–30. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20040101-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.VandeCreek L. Professional chaplaincy: An absent profession? J Pastoral Care. 1999;53:417–32. doi: 10.1177/002234099905300405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.VandeCreek L, Siegel K, Gorey E, Brown S, Toperzer R. How many chaplains per 100 inpatients? Benchmarks of health care chaplaincy departments. J Pastoral Care. 2001;55:289–301. doi: 10.1177/002234090105500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albaugh JA. Spirituality and life-threatening illness: A phenomenologic study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:593–8. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.593-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iranmanesh S, Abbaszadeh A, Dargahi H, Cheraghi MA. Caring for people at the end of life: Iranian oncology nurses’ experiences. Indian J Palliat Care. 2009;15:141–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.58461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adib Hajbaghery M, Salsali M. A model for empowerment of nursing in Iran. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deal B. A pilot study of nurses’ experience of giving spiritual care. Qual Rep. 2010;4:852–63. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahon-Graham PE. Omaha, NE: College of Saint Mary; 2008. Nursing students’ perception of how prepared they: Are to assess patients’ spiritual needs. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stoll R. The essence of spirituality. In spiritual dimensions of nursing practice. In: Carson V, editor. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun-Seo I, Yong J. Brisbane, Australia: Honor Society of Nursing, Sigma Theta Tau International; 2012. The experience of spiritual growth in hospital middle manager nurses. 23rd International Nursing Research Congress. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franklin MD, Schlundt DG, McClellan LH, Kinebrew T, Sheats J, Belue R, et al. Religious fatalism and its association with health behaviors and outcomes. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31:563–72. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.6.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miles A, Rainbow S, von Wagner C. Cancer fatalism and poor self-rated health mediate the association between socioeconomic status and uptake of colorectal cancer screening in England. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:2132–40. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harandy TF, Ghofranipour F, Montazeri A, Anoosheh M, Bazargan M, Mohammadi E, et al. Muslim breast cancer survivor spirituality: Coping strategy or health seeking behavior hindrance? Health Care Women Int. 2010;31:88–98. doi: 10.1080/07399330903104516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walker RJ, Smalls BL, Hernandez-Tejada MA, Campbell JA, Davis KS, Egede LE. Effect of diabetes fatalism on medication adherence and self-care behaviors in adults with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:598–603. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahmad F, Muhammad M, Abdullah AA. Religion and spirituality in coping with advanced breast cancer: Perspectives from Malaysian Muslim women. J Relig Health. 2011;50:36–45. doi: 10.1007/s10943-010-9401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.ImamRezaNetwork. Tawassul (Recourse) to Holy Imams (A.S.) [Last accessed on 2013 Sep 3]. Available from: http://www.imamreza.net/eng/imamreza.php?id=1275 .

- 53.Rahnama M, Khoshknab MF, Maddah SS, Ahmadi F. Iranian cancer patients’ perception of spirituality: A qualitative content analysis study. BMC Nurs. 2012;11:19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hebert RS, Jenckes MW, Ford DE, O’Connor DR, Cooper LA. Patient perspectives on spirituality and the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:685–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fallah R, Keshmir F, Lotfi-Kashani F, Azargashb E, Akbari ME. Post-traumatic growth in breast cancer patients: A qualitative phenomenological study. Middle East J Cancer. 2012;3:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, Kyriakopoulos D, Malamos N, Damigos D. Personal growth and psychological distress in advanced breast cancer. Breast. 2008;17:382–6. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]