Abstract

Background:

Nurses as the major group of health service providers need to have a satisfactory quality of work life in order to give desirable care to the patients. Workplace violence is one of the most important factors that cause decline in the quality of work life. This study aimed to determine the quality of work life of nurses in selected hospitals of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and its relationship with workplace violence.

Materials and Methods:

This was a descriptive-correlational study. A sample of 186 registered nurses was enrolled in the study using quota sampling method. The research instrument used was a questionnaire consisting of three parts: Demographic information, quality of work life, and workplace violence. Collected data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics by SPSS version 16.

Results:

The subjects consisted of 26.9% men and 73.1% women, whose mean age was 33.76 (7.13) years. 29.6% were single and 70.4% were married. About 76.9% of the subjects were exposed to verbal violence and 26.9% were exposed to physical violence during past year. Mean score of QNWL was 115.88 (30.98). About 45.7% of the subjects had a low level of quality of work life. There was an inverse correlation between the quality of work and the frequency of exposures to workplace violence.

Conclusions:

According to the results of this study, it is suggested that the managers and decision makers in health care should plan strategies to reduce violence in the workplace and also develop a program to improve the quality of work life of nurses exposed to workplace violence.

Keywords: Emergency room, nurses, quality of work life, violence workplace

INTRODUCTION

With regard to the importance and notable role of human power in an organization, investigation of the elements, which increase staff's function and reduce absenteeism and desertion and ultimately lead to an increase in efficiency, is of great importance for researchers and experts. One of the important issues in this context is the quality of work life.[1] Nursing managers should design an attractive workplace which can absorb new nurses in addition to preserving the existing staffs in the system.[2] Therefore, high quality of work life has been suggested as an important issue in many organizations including the World Health Organization (WHO) from 1970s.[3] Quality of work life was suggested in early 70s and was investigated from different angles during several past decades. Walton is one of the experts who have investigated work life in eight dimensions (fair and adequate payment, safe working environment, provision of opportunities for continued growth and security, rule of law in organization, social ties, life work, overall living space, integrity of the organization, and development of human capabilities).[4]

In the 80s, American and European managers pointed to quality of work life as one of the most interesting methods to cause motivation and as a solution for designing and job enrichment, as well as a tool to solve the problems and organizational Gordian knot.[5] Quality of work life was used in the nursing context by Attridge and Challahan from 1990.[6] The last version of nurses’ work life quality model was suggested by Brooks and Anderson in 2001, in which nurses’ quality of work life was considered in four dimensions.

Work life home life Work life/home life dimension reveals the nurses’ life experience at work and home. Work design dimension describes the real work the nurses do. Work context dimension describes the effect of workplace on nurses and patients. Work world dimension describes vast social impacts as well as the effects of changes on the functioning of nursing profession.[7] Nurses as a giant group of health providers who handle human lives should have an appropriate work life in order to take care of the clients properly.[8] Results of a study on quality of work life in nurses of Tehran University of Medical Sciences in 2006 showed that 70% of nurses were not satisfied with their work life quality, and complained of most of their work life dimensions.[9]

Research conducted in hospitals in Tehran in 2010 showed an inverse correlation between nurses’ level of anxiety and quality of work life.[8] Nurses are responsible for patients’ quality of life. They should firstly have a proper work life themselves.

This is why the human resources section should try to improve its personnel's quality of work life.[10] Improvement of personnel's quality of work life has been mentioned as one of the important issues to guarantee health system stability, as high work life quality is essential to absorb and preserve the staffs.[11] Results of a study conducted in 2010 on the association between work life quality and organizational commitment among fire fighters in Malaysia showed a significant association between the two factors.[12] Workplace is one of the factors affecting the quality of given care, retaining nurses, and cost efficacy.[13] Research on the necessity of nurses’ work life improvement in 2003 showed that an increase in nurses’ work life quality leads to an improvement in patients’ care and nurses’ communication with patients’ families.[14] Work life has a major share in satisfaction with other life dimensions like family, leisure, and health.[15] Results of a study conducted in 2008 on the association between occupational stress and work life quality in army nurses showed an inverse association between the two factors.[16] One of the duties of the managers in a health services organization is to take action for improvement of work life quality and education of coping strategies, as some stressful elements like workplace violence are inevitable in these organizations and prevention of their psychological and behavioral effects is essential.[17] Workplace violence is one of the factors that lead to a decline in nurses’ work life quality and satisfaction and has a negative effect on the quality of patients’ care and satisfaction as well as nurses’ efficiency and competency.[18] Workplace violence has been changed to a warning phenomenon all over the world. Its real level is unknown yet, as what we see is just the tip of an iceberg.[19] Violent behaviors in workplace cause the staffs to experience anxiety, stress, fatigue, and depression, and reduce job satisfaction and organizational commitment.[20] Higher frequency of exposure to workplace violence leads to major mental hazards and negatively affects the victim's behavior.[21] Negative atmosphere, created after workplace violence, affects patient-staff communication and results in lower responses of nurses to patients’ needs, and consequently, the patients are less satisfied with the quality of health care.[22] Many studies showed that nurses were dissatisfied with their job security, so they were worried about their unsafe workplace.[23,24,25] Results of a study conducted in 2011 on 384 employees of Kerman Bahonar Copper Company showed an inverse correlation between work life dimensions and employees’ aggression.[26]

The researchers of the present study aimed to define and conduct a study on the quality of work life and its association with workplace violence of nurses in the emergency departments, with regard to the effective role of nurses in health services efficiency and patients’ and families’ satisfaction. The obtained results can make nursing managers determined to make a more proper background for improvement of the function and work life of nurses exposed to workplace violence, as well as patients’ care through control and management of workplace violence and making necessary changes in the working conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a descriptive correlational study conducted in the emergency wards of selected hospitals in Isfahan in 2012. Data were collected in two stages. In the first stage, the number of nurses with at least 1 year of work experience in the emergency ward (n = 360) OK was determined by referring to nursing offices of the selected hospitals. To calculate the sample size, modified Cochran formula was adopted in which existence or absence of violence was considered 50. Total number of nurses with BS and at least 1 year of work experience in the research environment was 360. Total number of subjects was estimated to be 186 and the sample size of each hospital was randomly allocated by quota sampling through proportion. In the second stage, the questionnaires were completed by qualified nurses meeting the inclusion criteria (having a BS degree in nursing, being mentally balanced, and having at least 1 year of work experience in the emergency ward and working in this ward at the time of study). The nurses who defectively completed the questionnaire were left out of study and sampling went on until the required number of subjects was selected. The adopted questionnaire had three sections: 1. demographic information (10 questions), 2. investigation of workplace violence exposure in a 1-year period (4 questions), and 3. investigation of nurses’ work life quality (42 questions).

Each item was scored 1-6 based on Likert's scale (absolutely disagree = 1; disagree = 2; relatively disagree = 3; agree = 4; relatively agree = 5; and absolutely agree = 6).

Quality Of Nursing Work Life(QNWL) questionnaire was designed by Brooks and Anderson in 2001 and its validity was confirmed. All the participants were given verbal and written Information about the purpose of the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all nurses and they were free to withdraw from the study at any time. The ethics committee of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences approved this study.

It was used by Khani et al. (2007) and Salam Zadeh et al. (2008). Its reliability was calculated by Cronbach's alpha (α = 0.93, α = 0.917) which showed an acceptable value.[28] Questionnaire of exposure to workplace violence was a researcher-made brief form of a standard questionnaire which was designed by the WHO, International Nursing Association, and Public Services Association in 2003, whose questions were modified to four questions related to goals of the present study. Content validity was used for assessing its validity, wherein the questionnaire was given to 10 academic members of the nursing faculty after preparation of the primary draft, and then, their indications were applied to the questionnaire. Reliability was checked by test-retest (r = 75%). The data in the present study were quantitative and qualitative (nominal and ordinal).

Descriptive (mean, SD) and inferential (Pearson correlation coefficient) statistical tests were used to analyze the data through SPSS version 16.

RESULTS

Subjects’ mean age was 33.76 (7.13) years; 70.4% of nurses were married and 29.6% were single. About 26.9% were males and 73.1% were females, 32.3% had work experience of 1-5 years, 30.1% had 6–10 years, and 37.7% had >10 years work experience in the emergency ward. The highest number of exposures to verbal violence (41.4%) was more than four times, and for physical violence (9.1%), it was two times.

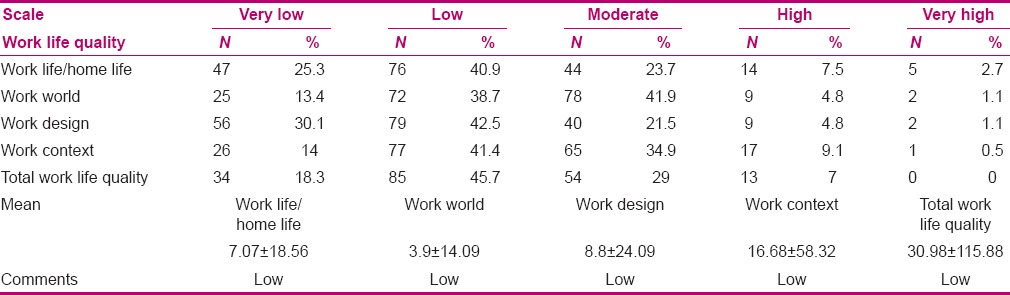

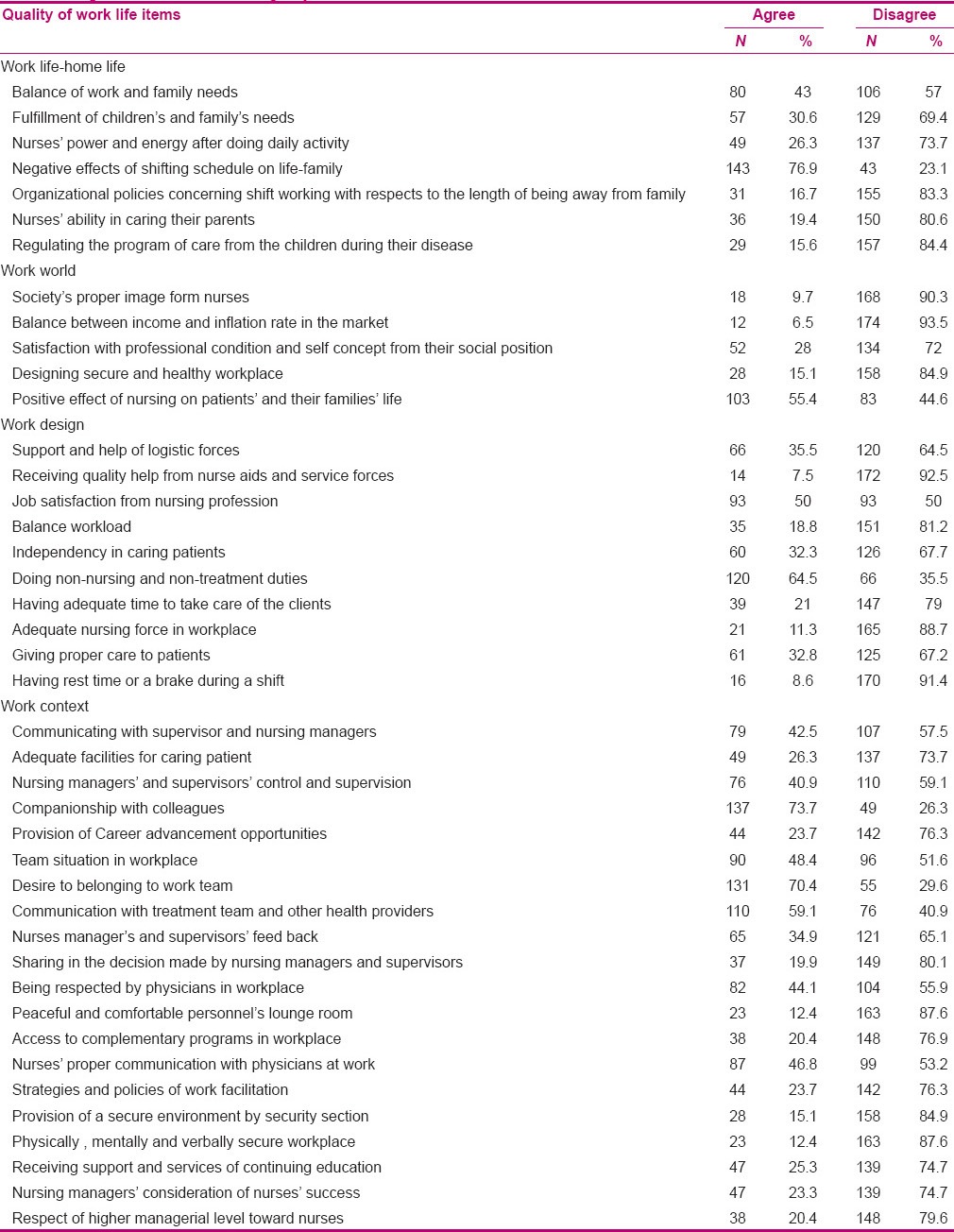

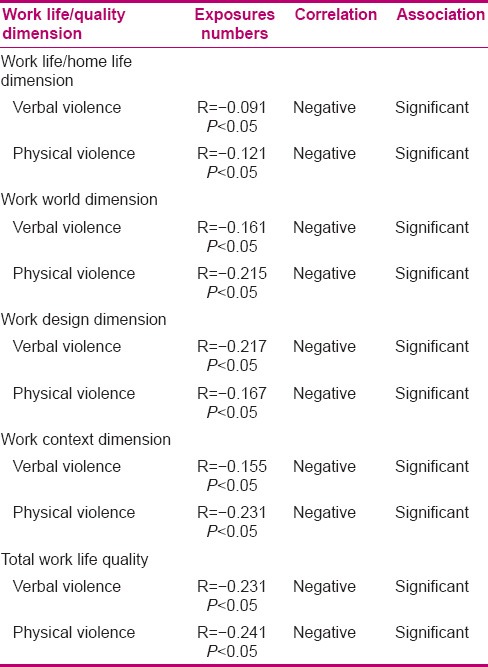

About 76.9% of the nurses were exposed to verbal violence and 26.9% to physical violence. Subjects’ work life quality and each of its dimensions and statistical indexes have been separately presented in Table 1. Nurses’ responses to work life quality items have been presented in Table 2. Association between the number of nurses exposed to verbal and physical workplace violence and their work life quality and its dimensions have been presented in Table 3.

Table 1.

Frequency distribution and mean scores of work life quality and its dimensions in emergency nurses

Table 2.

Responses of nurses in emergency wards to work life items

Table 3.

Association between the number of nurses’ exposure to verbal, physical workplace violence and work life quality and its dimensions

DISCUSSION

Improvement of work life quality is counted as a long-term and practical way to absorb and preserve human resources, which should be considered by health care managers.[27] Nurses’ work life quality dimensions and their association with the number of workplace violation exposures are discussed as follows.

Work life/home life dimension

Most of the nurses were dissatisfied with this dimension and mentioned the reasons as family's needs, working hours, and low energy after doing their daily tasks. Nurses reported that they spend a long time at their workplace, so they have little energy after work and cannot fulfill their families’ needs, which is consistent with the results reported in previous studies.[24,28,30]

Work world dimension

Disproportionate salary and reward was one of the reasons for nurses’ dissatisfaction with their work life quality. Behavioral theories like Mallow and Herzberg behavioral theories showed that fulfillment of primary needs is essential as the individuals cannot concentrate on higher needs if their primary needs are not met.[31] In the present study, 93.5% of nurses believed that their salary was not balanced with the inflation rate in market, which is in line with previous studies.[8,9,23,32,33] Meanwhile, 57% of nurses in the US believed their salary was balanced with their expenses.[24] Nurses’ low income is one of the major reasons for their job dissatisfaction and desertion.[34]

Work design dimension

About 81.2% of the nurses believed that they had high workload, which is consistent with previous studies.[32,33,35,36] On the other hand, 67.2% of the nurses believed they were not independent in taking care of the patients, which concords with former studies in which nurses reported they had low autonomy in decision making about patients’ care.[37,38] About 88.7% of the nurses believed there were not adequate nursing personnel in their work environment and 64.5% believed that they were given extra non-nursing tasks. Shortage in human resources and increase of nurses’ workload act as pressure factors among nurses, which lead to professional and organizational desertion.[39] Despite the shortage in human resources, nurses are assigned to non-nursing tasks. These dimensions of malutilization of nursing force can increase the shortage of nursing force in a vicious cycle and affect nurses’ skills and experiences. Such challenges may impose a notable pressure on nurses and negatively affect nurses’ perception of work life.[40]

Work context dimension

Managerial methods act as one of the problems in this dimension, which include lack of managers’ supervision, feedback, participation in decision making, higher level of managers’ respect toward nurses, inefficient nursing strategies and policies concerning facilitation of work, and modification of nurses’ concerns so that they think their struggles are not officially noted by nursing managers. Previous studies on quality of work life for nurses show that nurses’ recognition and function directly affect their intention to stay in nursing profession. Load of work in nurses, without authorities’ reward, leads to an increase in nurses’ intention to leave their profession.[41] About 58.5% of nurses believed they were not able to communicate with their supervisors and nurse managers. In a study on the quality of work life among nurses in the US, 72% of nurses reported to have proper communication with their nursing managers and supervisors, which is not consistent with the results of the present study.[24] Communication with supervisors and other colleagues is among the factors which are associated with job satisfaction.[36] About 84.9% of nurses believed that the security section did not make a secure environment for the nurses, and about 87.6% believed that their workplace was not physically, mentally, and verbally safe.

Previous research clearly revealed nurses’ concerns about workplace security. Insecure workplace is a major factor in nurses’ job dissatisfaction.[23,24] The findings of the present study showed that 76.9% and 26.9% of nurses were exposed to verbal and physical violence, respectively, in the year prior to study, which shows a high prevalence and is in line with a study conducted in Babol University of Medical science in 2009.[42] As the staffs in health care system are exposed to workplace violence, prevention of violence and providing education of the necessary interventions against violence should be followed at all levels of an institute.[43]

The authorities should also help promotion of staffs’ services, especially that of nurses, by making a secure workplace.[44] There is a negative correlation between the number of exposures to verbal and physical violence and work life quality and its dimensions, which has not been studied so far.

CONCLUSION

With regard to the above-mentioned negative correlation, it can be noted that workplace violence is a negative element reducing nurses’ work life quality.

Suggestions

-

As the work life quality of nurses working in selected hospitals in Isfahan is less than moderate, managers and authorities in hospitals should make policies for promotion of nurses’ work life quality through the following interventions:

Hospital managers should consider improvement of working conditions and making a supportive, friendly, and intimate environment for all the staffs, involving nurses in decision making and respecting their viewpoints, and designing a payment system based on nurses’ real function and nursing managers’ and supervisors’ more efficient humanistic communications.

Nurses’ work life quality is influenced by social, executive, managerial, and specific cultural conditions, and the present study revealed a negative correlation between the number of nurses exposed to violence and work life quality. With respect to the outcomes of workplace violence and its effect on work life quality, managers and authorities of these hospitals should think of solutions for the same. Violence management education in the form of educational workshops can be also effective.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This article is an extract of a research project and MS dissertation No. 391388 approved by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. We greatly appreciate the Vice-Chancellor for research of this university for the financial support provided. We also thank the authorities in hospitals and nurses in emergency wards who cooperated with us in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Salamzade Y, Mansury H, Farid D. The relationship between quality work life and prodictivity of human resourse in the care centers (case study: Hospital nurses yazed) JUNMR. 2008;6:60–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bare LL. Factors that most influence job satisfaction among cardiac nurses in an acute care setting. Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. 2004 Paper 322. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nasl Saraji G, Dargahi H. Study of quality of work life (QWL) Iran J Public Health. 2006;35:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walton R. Quality of Work Life: What is it? SMR. 1973;15:11–21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirkamali SM, Narenji Sani F. A Study on the Relationship between the Quality of Work Life and Job Satisfaction among the Faculty Members of the University of Tehran and Sharif University of Technology. IRPH. 2008;14:71–102. [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Brien-Pallas L, Baumann A. Quality of nursing worklife issues-a unifying framework. Can J Nurs Adm. 1992;5:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooks BA, Anderson MA. Defining quality of nursing work life. Nurs Econ. 2004;23:319–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohammadi A, Sarhanggi F, Ebadi A, Daneshmandi M, Reiisifar A, Amiri F. Relationship between psychological problems and quality of work life of Intensive Care Units Nurses. IJCCN. 2011;4:135–40. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dargahi H, Gharib M, Goodarzi M. Quality of work life in nursing employees of Tehran University of Medical Sciences hospitals. Hayat. 2007;13:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boonrod W. Quality of Working Life: Perceptions of Professional Nurses at Phramongkutklao Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92:7–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lees M, Kearns S. Florida: Longwood Publishing; 2005. Improving work life quality: A diagnostic approach model. Health care quarterly online case study. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Normala D. Investigating the relationship between quality of work life and organizational commitment amongst employees in Malaysian firms. Int J Bus Manage. 2010;5:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurst K. Relationships between patient dependency, nursing workload and quality. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmeyer A. A moral imperative to improve the quality of work-life for nurses: Building inclusive social capital capacity. Contemp Nurs. 2003;15:9–19. doi: 10.5172/conu.15.1-2.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sirgy J, Efraty D, Siegel P, Donng-Jin-Lee A new measure of quality of work life (QWL) based on need satisfaction and spillover theorie. Social Indicators Research. 2001;55:241–302. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khaghanizadeh M, Ebadi A, Cirati Nair M, Rahmani M. The study of relationship between job stress and quality of work life of nurses in military hospitals. MIL Med J. 2008;10:175–84. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McVicar A. Workplace stress in nursing: A literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44:633–42. doi: 10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Celik S, Celik Y, Agırbas I, Ugurluoglu O. Verbal and physical abuse against nurses in Turkey. Int Nurs Rev. 2007;54:359–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2007.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Martino V. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. Relationship of work stress and workplace violence in the health sector. Geneva: ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aytac S, Dursun S. The effect on employees of violence climate in the workplace. Work. 2012;41:3026–31. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-0559-3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rippon TJ. Aggression and violence in health care professions. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31:452–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winstanley S, Whittington R. Aggression towards health care staff in a UK general hospital: Variation among professions and departments. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khani A, Jaafarpour M, Dyrekvandmogadam A. Quality of nursing work life. J Clin Diagn Res. 2008;2:1169–74. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brooks BA, Anderson MA. Nursing work life in acute care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2004;19:269–75. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200407000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Gilany AH, El-Wehady A, Amr M. Violence against primary health care workers in Al-Hassa, Saudi Arabia. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25:716–34. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porkiani M, Mehdi Yadollahi, Zahra Sardini, Ghayoomi A. Relationship between the Quality of Work Life and Employees’ Aggression. Journal of American Science. 2011;7:687–706. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gifford BD, Zammuto RF, Goodman EA. The relationship between hospital unit culture and nurses’ quality of work life. J Healthc Manag. 2002;47:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khani A, Jaafarpour M, Dyrekvandmogadam A. Quality of nursing work life. J Clin Diagn Res. 2008;2:1169–74. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rastegari M, Khani A, Ghalriz P, Eslamian J. Evaluation of quality of working life and its association with job performance of the nurses. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2010;15:224–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Almalki MJ, FitzGerald G, Clark M. Quality of work life among primary health care nurses in the Jazan region, Saudi Arabia: A cross sectional study. Hum Resour Health. 2012;10:10–30. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-10-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dartey-Baah K, Amoako GK. Application of Frederick Herzberg's Two-Factor theory in assessing and understanding employee motivation at work: A Ghanaian Perspective. Einstein J Biol Med. 2011;3:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee H, Hwang S, Kim J, Daly B. Predictors of life satisfaction of Korean nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48:632–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hegney D, Eley R, Plank A, Buikstra E, Parker V. Workforce issues in nursing in Queensland: 2001 and 2004. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:1521–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.AbuAlRub RF. Job stress, job performance, and social support among hospital nurses. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004;36:73–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nuikka ML, Paunonen M, Hänninen O, Länsimies E. The nurse's workload in care situations. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33:406–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Best MF, Thurston NE. Measuring nurse job satisfaction. J Nurs Adm. 2004;34:283–90. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200406000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cook G, Gerrish K, Clarke C. Decision-making in teams: issues arising from two UK evaluations. J Interprof Care. 2001;15:141–51. doi: 10.1080/13561820120039874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mrayyan MT. Nurses’ autonomy: influence of nurse managers’ actions. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45:326–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen HC, Chu CI, Wang YH, Lin LC. Turnover factors revisited: A longitudinal study of Taiwan-based staff nurses. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45:277–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vagharseyyedin SA, Vanaki Z, Mohammadi E. Quality of work life: Experiences of Iranian nurses. Nurs Health Sci. 2011;13:65–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.AbuAlRub RF, AL-Zaru IM. Job stress, recognition, job performance and intention to stay at work among Jordanian hospital nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2008;16:227–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.RafatiRahimzadeh M, Zabihi A, Hosseini J. Verbal and Physical Violence on Nurses in hospitals of Babol University of Medical Sciences. Hayat. 2011;17:78–89. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wells J, Bowers L. How prevalent is violence towards Nurses working in general hospitals in the UK? J Adv Nurs. 2002;39:230–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chapman R, Styles I. An epidemic of abuse and violence: Nurse on the front line. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2006;14:245–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aaen.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]