Abstract

Background:

Hope is the most important factor in diabetic patients’ life. The level of hope may be changing among these individuals as a result of chronic nature of diabetes and its complications. When the level of hope increases among these patients, they can resist against physical and psychological complications of diabetes more, accept the treatment better, enjoy life more, and adapt with their situations more efficiently. This study aimed to define the efficacy of hope therapy on hope among diabetic patients.

Materials and Methods:

This was a quasi-experimental study conducted on 38 diabetic patients referring to Sedigheh Tahereh Research and Treatment Center affiliated to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Iran in 2012. The subjects were selected based on the goals and inclusion criteria of the study and then were randomly assigned to study and control groups. Herth Hope Index (HHI) was completed by both groups before, after, and 1 month after intervention. In the study group, 120-min sessions of hope therapy were held twice a week for 4 weeks. Descriptive and inferential statistical tests were adopted to analyze the data through SPSS version 12.

Results:

Comparison of the results showed that hope therapy significantly increased hope in diabetic patients after intervention in the study group compared to control (P < 0.001).

Conclusions:

The results showed that hope therapy increased hope among diabetic patients. This method is suggested to be conducted for diabetic patients.

Keywords: Diabetics, group therapy, hope, Iran

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes refers to a group of metabolic diseases with a common characteristic of increased blood sugar resulting from a defect in secretion of insulin or a defect in its function and/or both.[1] One of the reasons for the health and treatment system focusing on diabetes is its prevalence. Based on the International Federation for Diabetes report, there are 189 million diabetic patients in the world[2] and it is also predicted to reach 360 million people in 2030.[3,4]

The second reason to focus on diabetes is the complications and mortality associated with this disease. Blood sugar increase results in short- and long-term complications in diabetic patients.[1] Treatment and the costs associated with the care are very high for diabetes. The costs related to diabetes are divided into two groups: Direct costs which include treatment and medical services and the indirect ones which include short-term or long-term disability, job loss, and early mortality.[4] The imposed burden of diabetes is about 44 billion dollars as direct and 54 billion dollars as indirect costs. In Iran, yearly burden (physicians’ visit fee) accounts to 10 billion dollars.

On the other hand, per capita cost of a diabetic patient is 250 dollars.[5] Although chronic patients have longer life span compared to the past due to medical advancements, they simultaneously face adaptation problems more than before; therefore, despite the fact that the main concern in health and treatment was individuals’ life preservation, the main challenge of the present century is to care about general health and a qualified and joyful life.[6] Diabetic patients’ mental health is a specific concern.[7] Research shows that psychological, social, and disabling problems such as feeling of tiredness, irritability, anger, depression, and anxiety are seen more in diabetic patients than other individuals.[8] Concurrency of emotional problems such as depression and anxiety among diabetic patients is accompanied with reduction of quality of life, self-care defective behaviors, and reduction of blood sugar control among these patients. Management and control of diabetes can be disturbed by existence of diabetes-related emotional problems such as fear of hypoglycemia, worrying about complications, or not accepting the disease. Psychological and social problems may be caused by diet and activity limitations, the need for precise and constant self-care, and the possibility of serious physical complications like renal, ocular, cardiac, and medullary problems. Individuals’ acceptance of the disease to change their lifestyle based on that is not always easy.[9] There are numerous non-medicational methods and treatments to help diabetic patients to cope and adapt with these problems, such as complementary treatments. Hope therapy is one of the complementary treatments.

Various researches have shown that hope is a meaningful element in life and helps individuals to adapt with the disease and its problems, decrease their mental suffering, and enhance their quality of life and mental and social health.[10] It can also physiologically and emotionally help patients to tolerate the crisis of the disease.[11] Hope is an essential element in chronic patients’ life and has high effects on their adaptation with disease. Hope plays a major role in patients’ quality of life and affects their various stages of the disease. Hope has been defined as an internal power that can enrich life and enable the patients to have a perspective farther than their present state.[10] It is also an important issue in Islam as God always invites the human beings to hope and show optimism toward life and designs a brighter future for them. On the contrary, disappointment has been counted as hideous and is named as the second great sin as it leads to disappointment from mercy and compassion of God and not believing in His endless power and kindness.[11] In Quran, it is said, “who gets hopeless from Lord's compassion except the perverse”[12] and “keep hopeful to God's mercy as only the perverse give up hope.”[12] Positive effects of helpful psychological structures (like optimism and hope) on physical and mental health have been emphasized in various studies.[13] Positive individuals are healthier and happier and their immunity system functions better. They can cope with psychological tensions better through application of more efficient coping strategies like reevaluation and problem solving. They also actively avoid stressful events of life and make a better supportive social network around themselves. They have healthier biological styles which protect them against diseases, and if they are diseased, they follow medical recommendations better through behavioral patterns, which accelerate recovery.[14] Lack of hope and a goal in life leads to patients’ lower quality of life and hopeless beliefs. People who deal with chronic diseases have different physiologic, psychological, social, and emotional needs compared to healthy individuals.

Therefore, finding some methods to fulfill these needs is a part of the process of coping with the disease. During fulfillment of patients’ physical needs, their emotional and social needs may be ignored. So, the best option in either patients’ recovery or in relation with fulfillment of their needs is the group of interventions which not only consider physical treatments but also psychological and social treatments, for which hope therapy can play this role well.[10] Hope can be considered as a symbol of mental health in nursing investigations.[15] On the one hand, nurses spend more time with diabetic patients compared to physicians and have different responsibilities in diabetes team, and on the other hand, they play a helpful role in diagnosis and treatment of these patients’ emotional problems.[16] Through working with chronic patients, nurses are in relation with the whole of a person (regarding physical, mental, and social aspects) in addition to dealing with his/her physical problems and this holistic approach needs a vast field of knowledge in behavioral and psychological sciences.[17] Meanwhile, psychiatric nurses have numerous and efficient roles in complementary medicine related interventions whose education and application is among their duties in relation with promotion of individuals’ health. Psychiatric nurses are also counted as the practitioners, performers, and prescribers of this type of medicine.[18,19] Johnswin, a complementary medicine physician, has emphasized on the importance of psychiatric nurses’ role in conducting and performing complementary skills and medicine and highlights complementary interventions as nurses’ role.

He argues that psychiatric nurses often conduct those interventions that focus on mental, social, and biological aspects.[20] Application of group hope therapy, which is one among the complementary treatments, has a specific position, and despite the importance of hope therapy as a complementary treatment in motivating and causing behavior changes, it has been ignored in health-related domains, so poor research is observed in this field.[21] Research shows that promotion of hope is an efficient way to promote chronic patients’ quality of life. Increased hope consequently leads to an increase in self-care level, quality of life, and general health among this group of patients.[22] The highest volume of research on hope therapy in recent decades has been conducted by Seligman, the father of positive psychology (2000), and Snyder.[23] They believe that disappointment leads to physical and mental diseases.[21,24,25] Snyder's studies revealed that chronic patients undergoing hope therapy show a more appropriate response after receiving hope therapy intervention when faced with disease-related stress and tensions, resist more during treatment, and accept and follow the suggested treatment better.[26] Hope therapy in the present study is a combination of Snyder's hope therapy and hope program in Islam. As few studies have been conducted on the effect of hope therapy on the level of hope in diabetic patients, the present study aimed to investigate the effect of group hope therapy on the level of diabetic patients’ hope.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a quasi-experimental two-group (study and control) two-step study conducted on 38 diabetic patients in 2012. Study population included all diabetic patients having a medical record and referring to Sedigheh Tahereh Research and Treatment Center in Isfahan, Iran. Inclusion criteria were the interest to attend the study and Muslim diabetic patients aged 30-50 years residing in Isfahan, who could express their experiences and memories. On the other hand, the subjects were excluded in case of attending other psychotherapy programs during the study, taking psychotic medications, being involved in acute depression, and finally, in the event of death of any of their immediate relatives. Out of 250 patients’ medical files studied, 38 diabetic patients who met the inclusion criteria were selected through random convenient sampling. After getting their written informed consent, they were randomly assigned to two groups of study and control. Data collection tool was a two-section questionnaire. The first section was about personal characteristics including age, sex, marital status, education level, length of diabetes, types of complications due to diabetes, and types of diabetes medication taken or insulin. The second section included Herth Hope Index (HHI) containing 12 questions based on a 4-point Likert scale scored as score 1 (absolutely disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (agree), and 4 (absolutely agree). Questions 3 and 6 were scored inversely. HHI scores in the range 12-48 and higher scores show a better hopefulness status. Scores 12-24 show low level of hope (hopelessness), 25-32 indicate moderate level of hope, and 37-48 indicate high level of hope. Herth confirmed the validity of this index through Cronbach's alpha (0.97) and by test–re-test and calculation of correlation coefficient of 0.91. In Iran, after extraction and translation of Herth's questionnaire, Pourghaznein used both the above-mentioned methods to calculate test validity based on Cronbach's alpha of 0.76 and Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.84. He also confirmed the reliability of the tool through some expert psychologists.[27] The questionnaire was filled by both study and control groups before intervention. As in psychotherapy, the number of group members is 7-12 members,[28] the study group was divided into two groups of 9 and 10 members, and each group separately attended the hope therapy sessions based on an already made schedule on different days twice a week for eight sessions of 2 h duration. The location of the sessions was a classroom in Sedigheh Tahereh Center. The educational program comprised a combination of Snyder hope therapy and hope program in Islam (hope giving Hadis and verses and Quran stories like those of Joseph and Jonah). Hope therapy is a narrative and story-based approach on individuals’ life, in which every person tells his/her story of life based on his/her own culture. As this study was conducted in Iran which is an Islamic country, the researcher tried to make a combination of hope program in Islam and Snyder's hope therapy method. This model has already been localized concerning Iranian and Islamic culture.[22] After researcher's explanation about hope program in Islam and Snyder hope therapy model, every member framed his/her story of life and retold that. This program had been already localized for patients with basic hypertension,[22] but no localized study was conducted on diabetic patients.

Each session included four sections. In the first section, activities and assignments of the former session were discussed for 25 min, and the members were encouraged to help one another to solve problems and do their assignments like getting hopeful through telling their story of life, hope domination, and empowerment. In the second section, the subjects underwent education of psychological and hope-related skills through a treatment unity between the subjects and the therapist, lead to increase of hope through different techniques such as goal expanding optimizing techniques. They included providing a structure for uncovering goals, coming up with clear and workable goals, finding the silver lining, and Selgman optimism model, as well as hope maintaining skills for about 30 min. In this section, the subjects learned a new hope-related skill. In the third section, which lasted for 50 min, the methods of application for these skills in daily life were discussed and the subjects practically conducted them. The subjects were encouraged to go over the problems objectively and clearly and help one another to solve them by use of hope skills. In the last 15 min of the session, the assignments of the future session were determined. No intervention was conducted for the control group. Immediately after and month after the intervention, HHI questionnaire was completed by the study and control groups again. Finally, the collected data were analyzed by descriptive and inferential statistical tests such as independent t-test, Chi-square test, repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA), Mann–Whitney, and Fischer's exact test.

Ethical considerations

The selected patients were reassured about data confidentiality and their access to the final results. Participants read and understood the information necessary to make an informed decision about their voluntary participation

RESULTS

The obtained results in both groups showed that there was no significant difference in subjects’ baseline demographic characteristics such as age, number of children, length of diabetes, sex, marital status, types of complications that resulted from diabetes, types of medication consumed to control diabetes, and level of education (P > 0.05).

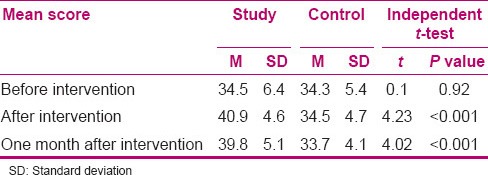

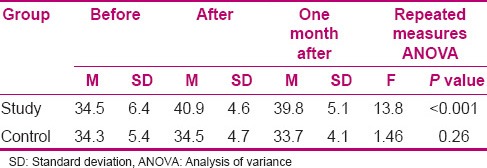

The results also showed that all subjects suffered from type 2 diabetes. Independent t-test showed no significant difference in the mean scores of hope before intervention in the study and control groups (P = 0.92), but immediately after and 1 month after the intervention, the mean scores of hope were significantly higher in the study group compared to the control group (P < 0.001) [Table 1]. Repeated measure ANOVA showed no significant difference in the mean scores of hope in the control group before, immediately after, and 1 month after intervention (P = 0.26), but a significant difference was observed in the mean scores of hope in the study group before, immediately after, and 1 month after intervention (P < 0.001). Since no intervention was conducted in the control group, the mean score of hope had no significant difference immediately after and 1 month after intervention compared to before intervention. Meanwhile, in the study group in which hope therapy intervention was conducted, the mean score of hope was notably increased after intervention compared to before intervention, and this increase continued until 1 month after intervention. Therefore, it can be concluded that hope therapy has been effective on increase of hope in diabetic patients [Table 2]. Least significant difference (LSD) post-hoc test showed a significant increase in the scores of hope before and after intervention (P < 0.001) and before and 1 month after intervention (P = 0.003) in the study group, but not before and 1 month after intervention in control group (P = 0.28), which showed that the effect of hope therapy continued until 1 month of follow-up.

Table 1.

Comparison of mean scores of hope in the two groups of study and control

Table 2.

Comparison of mean scores of hope at three time periods of intervention in the two groups

DISCUSSION

The results of the study showed that hope therapy could affect the level of hope among diabetic patients in the study group. It can be reasoned that hope is a strong adaptation mechanism among chronic patients including diabetic patients, so that hopeful individuals can tolerate the crisis of the disease more conveniently.[29] This finding is in line with that of some other studies. Irving et al.,[30] Klausner et al.,[31,32] and Hankins,[33] in their studies during the investigation on hope-based interventions among adults, showed that this therapy led to an increase in hope and a decrease in depression. Shekarabi et al. showed that group hope therapy significantly increased hope among mothers of children with cancer and reduced their depression, and the results of a 2-month follow-up showed no significant change in that high level of hope in this group of mothers compared to after intervention.[34] Cheavens et al.[35] in a community sample showed that group hope therapy based on Snyder and McDermott hope approach increased hope in the study group, but the difference was not significant, possibly due to lack of identical and homogenous subjects. Ghasemi et al.[36] showed that group education intervention based on Snyder hope theory style led to an increase in joyfulness of the elderly. Bijari et al.[37] showed that group therapy based on hope therapy approach significantly increased hope and decreased depression among women with cancer compared to the control group.

Although all of the aforementioned studies have emphasized that hope therapy can increase hope, they cannot be compared with the present study as none of them have been conducted among diabetic patients and used hope program in Islam; thus, the research in this field is poor.

Sotoudeh Asl et al.[22] showed that hope therapy promoted quality of life inpatients with hypertension more than medication, so that the effect of treatment remained until 3 months post intervention. The present study, like the study of Sotoudeh Asl et al., was a combination of Snyder hope therapy and hope program in Islam, with a difference in the length of follow-up (1 month in the present study).

This study cannot be compared with the study of Sotoudeh Asl et al. as the subjects were hypertensive patients and the variable of hope was not measured directly in their study. Ebadi et al.[38] showed that application of positivism with emphasis on Quran verses increased hope among widowed women in Ahwaz and the effect of intervention with regard to follow-up test results had the essential stability. Their results were similar to the results obtained by us to some extent, as they used the effect of Quran verses on the level of hope, which is a positive psychological component; this similarity is reinforced. No studies (even conducted on non-diabetic patients) were found to report that hope therapy had negative effects on hope and lowered that. The following factors have been effective in description and explanation of the efficacy and constant effect of hope therapy on increase of hope among diabetic patients:

Encouragement of the subjects to tell the story of their life is one of the principles in hope therapy. These stories let the therapist highlight the sparkles of hope, especially those that may disappear due to some memories and thoughts.[31]

Determination of realistic and measurable goals and changing the great goals to some minor and more accessible goals is a characteristic of hopeful individuals.[39] The diabetic subjects started this step by selection of minor and logical goals, so at to achieve them in 1 month.

Limitations of the study

Low sample size can be mentioned as one of our limitations. It is suggested to recruit a higher sample size in future studies. Another limitation was use of a self-report data collection tool. In future studies, objective behavior indexes or semi-structured interviews can be adopted. As the sessions were managed by the researcher, unexpected bias may have affected approval of the hypotheses, which can be counted as another limitation for the present study.

CONCLUSION

With concentration on hope-bringing thoughts, hope therapy helps individuals to use their problem-solving abilities better, and consequently, they use problem-solving skills more when faced with problems and challenges, instead of problem-avoiding behaviors.[40] Hope therapy used positive psychology instead of concentration on disabilities. Positive self-regard, hopeful imagination, healthy diet, sport, and being a member of social support networks are some characteristics of hopeful individuals which were focused in the present study.[41]

With regard to the results of the present study, it can be noted that group hope therapy can enhance hope among diabetic patients and it can be concluded that the efficacy of hope therapy can last during follow-up period.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Hereby, many appreciations go to all those who assisted us in conducting the present project and also other esteemed staff of Sedighe research center affiliated to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. This article was derived from a master thesis with project number 391027, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Grant No. 391027

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fauci A, Braunwald E, Braunwald E, Kasper D, Hauser S, Longo D, et al. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (endocrine and metabolic diseases) In: Sotodehnia AH, Asareh MH, translators. 18th ed. Tehran: Ketab Arjmand Publication; 2012. pp. 192–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schram MT, Baan CA, Pouwer F. Depression and quality of life in patients with diabetes: A systematic review from the European depression in diabetes (EDID) research consortium. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2009;5:112–9. doi: 10.2174/157339909788166828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunner LS, Smeltzer SC, Bare BG, Hinkle JL, Cheever KH. Nursing. 12th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2010. Brunner and Suddarth's textbook of medicalsurgical. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amrican Aiabetes Association. National diabetes fact sheet. [Last accessed on 2005 May 22]. Available from: http://www.diabetes.org/udeocumentations/nationaldiabetes fact sheetRev.pdf .

- 5.Soltanian AR, Bahreini F, Afkhami-Ardekani M. People awareness about diabetes disease and its complications among aged 18 years and older in Bushehr port inhabitants (Iran), Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews. 2007;1:245–249. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strine TW, Chapman DP, Balluz L, Mokdad AH. Health-related quality of life and health behaviors by social and emotional support: Their relevance to psychiatry and medicine. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43:151–9. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0277-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao W, Chen Y, Lin M, Sigal RJ. Association between diabetes and depression: Sex and age differences. Public Health. 2006;120:696–704. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahmodi A, Sharifi A. Comparison of Prevalence and factors associated with depression in patients with diabetes and non-diabetic individuals. Journal of Urmia Nursing and Midwifery Faculty. 2008;2:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moser A, van der Bruggen H, Widdershoven G. Competency in shaping one life: Autonomy of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a nurse-led, shared-care setting: A qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43:417–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdi N, Taghdisi M, Naghdi S. Vol. 14. Armaghane-danesh, Journal of Yasuj University of Medical Sciences; 2009. Efficacy of increasing hope interventions in cancer patient of Sanandag; pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebadi N, Faghihi A. Efficacy of positivism (optimism) on increase hope of widow Ahvaz women with emphasis on Koran. J Psychol Relig. 2010;2:61–74. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Josef Qoran.hojar, verse 56. verse 87. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Washington, Dc: American Psychhological Association; 2001. Optimism, pessimism, and psychological well-being». Change optimism and pessimism; pp. 182–216. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schram MT, Baan CA, Pouwer F. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2. Vol. 5. Bilthoven. The Netherlands: Research Consortium, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment.Centre for prevention and health services research; 2009. May, Depression and Quality of life in patients with diabetes: A Systematic Re-view from the European Depression in Diabetes (EDID) pp. 112–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dufault K, Martocchio B. C. 2. Vol. 20. Nursing Clinics of North America; 1985. Hope: Its spheres and dimensions; pp. 379–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pouwer F, Beekman AT, Lubach C, Snoek FJ. Nurses’ recognition and registration of depression, anxiety and diabetes-specific emotional problems in outpatients with diabetes mellitus. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60:235–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunner LS, Smeltzer SC, Bare BG. 12th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. Brunne and Suddarth's textbook of medical-surgical nursing. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kneisl CR, Trigoboff E. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc; 2009. Contemporary psychiatric mental health nursing. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stwurt GW. 9th ed. Mosby, Elsevier publication: 2009. Principle and practice of psychiatric nursing; pp. 123–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fortinash K. 4th ed. Mosby: Elsevier; 2008. Psychiatric mental health nursing. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seligman ME, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am Psychol. 2000;55:5–14. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sotodehasl N, Taherneshat dost H, Kalantari M, Talebi H, Khosravi A. Comparison of effectiveness of two methods of hope therapy and drug therapy on the quality of life in the Patients with Essential Hypertension. Journal of clinical psychology. 2010;2(1):27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snyder CR. USA: Academic Press; 2000. Handbook of hope: Theory, measures, and applications. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herth K. Development and implementation of a Hope intervention program. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1998;28(6):1009–1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snyder CR. New York: Free Press; 1994. The psychology of hope: You can get there from here. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snyder CR, Lopez S. Striking a balance: A complementary focus on human weakness and strength. In: Lopez SJ, Snyder CR, editors. Models and measures of positive assessment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porghaznin T, Ghafari F. Relationship between Hope and Self Steam of Clients with kidney transplantation in Emam Reza Mashhad Hospital. J Yazd Med Sci Univ. 2005;1:52–61. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snyder KM, Jerald K. Group therapy. In: Bahari S, Ranggar BA, Hossinshahi H, Mirhashemi M, Naghshbandi S, translators. 7th ed. Tehran: Ravan Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baljani E, Kazemi M, Amanpour E, Tizfahm T. Vol. 1. Medical Sciences Journal of Islamic Azad University, Uremia Medical Branch; 2011. A survey on relationship between religion, spiritual wellbeing, hope and quality of life in patients with cancer; pp. 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irving ML, Snyder CR, Gravel L, Hanke J, Hilberg P, Nelson N. Seattle, WA: Western psychological Association Convention; 1997. Hope and the effectiveness of a pre- therapy orientation group from community mental health center clients. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klausner E, Snyder CR, Cheavens J. A hope-based group treatment for depressed older adult outpatients. In: Williamson GM, Parmlee PA, Shaffer DR, editors. Physical Illness and Depression in older adults: A handbook of Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Plenum; 2000. pp. 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klausner EJ, Clarkin JF, Spielman L, Pupo C, Abrams R, Alexopoulos GS. Late-life depression and functional disability: The role of goal-focused group psychotherapy. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998;13:707–16. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(1998100)13:10<707::aid-gps856>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hankins SJ. Mississippi, United States: The University of Mississippi; 2004. Measuring the efficacy of the Snyder hope theory as an intervention with an inpatient population. A dissertation presented for the doctorate of philosophy. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shekarabi Ahari GH, Younesi J, Borjali A, Ansari Damavandi SH. The Effectiveness of group hope therapy on hope and depression of mothers with children suffering from Cancer in Tehran. Iran J Cancer Prev. 2012;4:183–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheavens SJ, Gum A, Feldman BD, Micheal ST, Snyder CR. San Francisco: American Psychological Association; 2001. A group intervention to increase hope in a community sample. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghasemi A, Baghban EI. Effectiveness of Group Hope Therapy Based Snyder hope theory on well-bing (fulfillment) of old people. Khorasghan Islamic Azad Univ. 2009;44:17–40. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bijari H, Ghanbari Hashemabadi B, Aghamohamadian H, Homaii SH. Effectiveness of Group therapy based on hope therapy on increase hope of women with cancer. Psychol Educ Stud Mashhad Ferdoosi Univ. 2009;1:171–84. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ebadi N, Sodani M, Faghihi A, Hossinpor M. Khozestan: Khozestan Islamic Azad university publication; 2009. Effectiveness education of optimism based on Koran verses on increase Hope of Ahvaz Divorced Women; pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snyder CR, Irving L, Anderson JR. Hope and health: Measuring the will and the ways. In: Snyder CR, editor. Handbook of social and clinical psychology: The health perspective. New York: Pergamon Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsevat J. Spirituality/religion and quality of life in patients with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:S1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benzein EG, Berg AC. The level of and relation between hope, hopelessness and fatigue in patients and family members in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2005;19:234–40. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm1003oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]