Abstract

Background

It is assumed that clear and complete information on the internet can reduce healthcare consumption.

Aim

We assessed in a randomised clinical trial whether a personalised online parent information program on infant respiratory symptoms can reduce primary care utilisation.

Design and setting

Randomised clinical trial in primary healthcare centres in a new residential area in the Netherlands.

Method

A web-based program (WHISTLER-online) was developed for parents that offered general information on childhood respiratory disease and personalised risk assessments. Parents of infants who enrolled from June 2009 to June 2012 in WHISTLER, an ongoing population-based birth cohort, were randomly allocated to ‘WHISTLER-online’ or ‘usual care’. Information about, first, consultations and, second, associated prescriptions for respiratory symptoms during the first year of life was collected from the electronic patient files.

Results

A total of 323 infants were randomly assigned to WHISTLER-online and 322 to usual care, and 314 and 305, respectively, were analysed. Of the parents, 70% used WHISTLER-online, and 99% of them judged it to be clear and useful information. There were differences neither in consultation rates for respiratory symptoms (incidence rate ratio 0.96 [95% CI = 0.85 to 1.09, P = 0.532]) nor in associated drug prescriptions.

Conclusion

Although parents greatly appreciate the provided facilities, a personalised e-support program on respiratory illnesses in infants does not substantially reduce healthcare utilisation.

Keywords: infant; internet; primary health care; signs and symptoms, respiratory

INTRODUCTION

The internet plays an increasing role in providing healthcare information,1–3 because it is widely available, accessible 24 hours a day, and anonymous. The internet is used to gather symptom information, to find extra information after a consultation, to participate in an online support group, or to be aware of other treatment alternatives.4

Parents appear to be frequent internet users when searching for health information,5–8 especially mothers seeking information during pregnancy and infancy.9 Young children experience many, particularly respiratory, symptoms that were shown to cause anxiety in parents.10–13 While care utilisation for respiratory symptoms in infancy is high,10,14,15 most symptoms of this nature are harmless and self-limiting, and not influenced by medication.16–19 Therefore, doctors can often only explain the course and self-limiting nature of the symptoms, and reassure the parents. This may imply that accurate online health information beneficially modifies health behaviour and care utilisation. Despite many initiatives on online information systems, there is only sparse evidence about effects on health behaviour. Most available evidence was collected retrospectively, is contradictory,20–25 includes only two studies on children,20,25 and contains no randomised clinical trials. Before large-scale implementation of internet programs with health information on common symptoms in young children, it is important to evaluate their effect on healthcare behaviour.

We developed an online electronic support program for parents offering both general information on childhood respiratory disease and personalised risk assessments for their own child (WHISTLER-online). This program aimed to provide sufficient objective information to help parents decide about healthcare utilisation. We conducted a randomised clinical trial to study whether infants of parents with access to WHISTLER-online use fewer healthcare services for respiratory symptoms than parents with ‘usual care’.

METHOD

Study population

This study was embedded in the ongoing WHeezing Illnesses STudy LEidsche Rijn (WHISTLER), a prospective population-based birth cohort study on determinants of respiratory illnesses. The study design and rationale of WHISTLER were described elsewhere.26 Briefly, healthy infants were enrolled in this study at the age of 2–3 weeks, before any respiratory symptoms had occurred and were followed for respiratory illnesses. Exclusion criteria were: gestational age <36 weeks, major congenital abnormalities, and neonatal respiratory disease. Extra exclusion criteria for WHISTLER-online were the absence of a computer or access to the internet, or the inability to use a computer or the internet. The study was approved by the local medical ethics committee (UMC Utrecht) and during the visit all parents signed for informed consent (WHISTLER-online added to WHISTLER informed consent form).

How this fits in

The internet plays an increasing role in providing healthcare information. Despite many initiatives on online information systems, there is only sparse evidence about effects on health behaviour in the general population and evidence from randomised clinical trials has been lacking. This study suggests that, although parents greatly appreciate the provided facilities, a personalised e-support program on respiratory illnesses in infants does not substantially reduce healthcare utilisation.

Randomisation and masking

From July 2009 until June 2012, all parents of children who participated in the WHISTLER project were randomised in a ‘WHISTLER-online group’ or a ‘usual care group’.

Randomisation was done during regular WHISTLER visits by a computer program allocating families without stratification on a 1:1 ratio. During this visit lung function was measured, which was only possible when children were asleep. Because lung function data were necessary for follow-up in WHISTLER, only children with a successful lung function measurement were randomised. The parents were introduced onto the internet program by researchers who were not involved in primary health care and outcome registration. Parents in the ‘usual care group’ were not informed about the existence of WHISTLER-online to prevent non-habitual internet searching about respiratory symptoms. Also the parents were not aware of study outcome parameters to prevent influencing their healthcare behaviour. Eligible twins or younger siblings also participating in WHISTLER during WHISTLER-online recruitment were allocated to the same family intervention.

WHISTLER-online intervention

A panel of parents was actively involved in the development of WHISTLER-online. Part one was based on frequently asked questions as collected in WHISTLER, and answers by participating paediatric pulmonologists and GPs. It contained general information about respiratory illnesses in infants, prevalence of respiratory symptoms, innocent self-limiting symptoms and symptoms requiring medical attention, risk factors for development of symptoms (like smoking), and general self-help measures. Part two was a personalised section in which an infant’s risk factors could be entered, shortly after birth, into a WHISTLER-derived prediction algorithm. This could reasonably discriminate between a low and high risk for clinically relevant respiratory disease during the first year of life.27 This algorithm included sex, head circumference, maternal smoking during pregnancy, season of birth, maternal history of allergy, maternal education, and maternal age as predictors. Infants in the lowest algorithm-predicted risk quintile have a 12%/year risk; the highest quintile have a 43%/year risk. This algorithm aimed to indicate an infant’s risk and prepare parents for expected symptoms. Part three enabled parents to introduce the number of days of symptoms of cough, wheeze, and fever of their child during the last month, and compare with respective mean symptom scores (+/– 1 SD) observed in all other children within WHISTLER. Fever was an alarm symptom in children aged <3 months. This comparison was intended to give parents insight into the usual prevalence and duration of respiratory symptoms in infants.

At enrolment, families received the internet address and a personal login code for their child. Parents were given both a verbal and written introduction to the internet program. While it was meant to inform on respiratory symptoms and support decisions about contacting primary care physicians, it was explained that such decisions remained the responsibility of the parents. A monthly letter, accompanying the WHISTLER questionnaire, reminded the parents about WHISTLER-online.

The patients in the control group received usual care, which was primary care, without a specific program to support in decision-making.

Outcomes

The primary outcome parameter was the number of visits for respiratory symptoms to primary health care during the entire first year of life, as recorded in the patient’s electronic database (Medicom®, PharmaPartners). GPs recorded visits according to the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC).28 GP visits for respiratory symptoms were defined as the occurrence of a ‘respiratory ICPC’, that is, dyspnoea (R02), wheezing (R03), cough (R05), acute upper tract infection (R74), acute bronchi(oli)tis (R78), pneumonia (R81), asthma-like symptoms (R96), or other less prevalent respiratory ICPCs (breath problems [R04], sneeze [R07], other symptoms of the nose [R08], symptoms of the throat [R21], abnormal sputum [R25], concern about respiratory illness [R27], acute laryngitis [R77], influenza [R88], other infection of the airways [R92], and other respiratory diseases [R99]). In Medicom, emergency and inpatient visits were also registered. Parents were also asked to write down the number of consultations for respiratory symptoms in the past month on the monthly questionnaire that was used in WHISTLER.

Secondary outcome parameters were the number of visits for lower respiratory symptoms to primary health care during the entire first year of life and the number of associated drug prescriptions as recorded in Medicom. Medication was classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification.

Because of the registration of all medical interventions by Medicom, the safety of the use of the program could be analysed at the end of the study (to check whether the program had caused children not to visit the GP in a timely way). To study whether parents experienced the program as burdensome, their worries were requested on a Likert-scale (0–100) on the monthly questionnaire.

The web program registered the number of visits, and allowed for questions and remarks. At the end of the children’s first year, an evaluation questionnaire about the program was sent to the parents.

Power calculation and statistical analysis

WHISTLER-online was assumed to reduce the proportion of visiting children and the mean number of visits for children. At a power of 90% and α of 0.05, 350 children randomised to each arm could detect a reduction of the proportion of children who visit their GP in their first year from 0.5929 to 0.47, an absolute 12% reduction. Outcomes were expressed as incidence rate ratios (IRRs) or relative risks with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and P-values. Poisson regression was used to analyse the association between intervention group and number of primary care visits as documented in the electronic patient file and parental reported consultations. As effects in children from one family are not independent, a mixed-effects analysis was performed. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The results were analysed based on the intention-to-treat principle. Analyses were performed using SPSS, 2001 (version 15.0), and the statistical program R (Package 2.12.2).

RESULTS

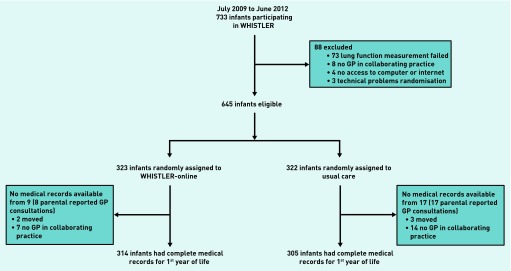

Between June 2009 and June 2012, 733 infants participated in WHISTLER. Pre-trial exclusions, randomisation, and follow-up are shown in Figure 1. The baseline characteristics of enrolled and non-eligible infants did not differ, although enrolled children had a slightly lower gestational age and their fathers were more often allergic to pollen, house dust mites, food, or pets. (Table 1). Of 645 infants, 323 were randomly assigned to WHISTLER-online and 322 to usual care. Fifty-three siblings (five twins, n = 31 WHISTLER-online, n = 22 usual care) were randomised. Table 2 shows no relevant differences for baseline characteristics between interventions. For 25 out of 26 infants (96%) who had moved and had no GP in a collaborating practice (9 WHISTLER-online, 17 usual care), it was possible to collect parental reported outcome data by the monthly questionnaires. Of all children 50.6% consulted the physician for respiratory symptoms, with a mean number of 3.4 (SD 2.3) consultations per infant per year. There were no differences between proportions of various numbers of consultations for respiratory illnesses in WHISTLER-online and usual care (Table 3). The mixed-effects analysis was not materially different (IRR 0.97 [95% CI = 0.76 to 1.26, P = 0.846]). Also, when parental reported consultations were taken into account no differences were found (IRR 1.05 [95% CI = 0.93 to 1.19, P = 0.44]). Also no difference was found in any of the secondary outcomes (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Trial profile.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the children who were randomised and who were not

| Not randomised (n = 88) | Randomised (n = 645) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) boys [N = 733] | 45 (51.1) | 308 (47.8) | 0.551 |

| Birth weight, mean grams (SD) [N = 733] | 3538.7 (487.0) | 3558.4 (500.2) | 0.726 |

| Birth length, mean cm (SD) [N = 733] | 51.0 (2.1) | 50.7 (2.2) | 0.315 |

| Gestational age, mean days (SD) [N = 733) | 281.1 (9.1) | 278.2 (9.5) | 0.009a |

| Maternal asthma in last 12 months, n (%) [N = 641] | 3 (5.2) | 44 (7.5) | 0.508 |

| Maternal allergy (allergy to pollen, house dust mite, food, or pets), n (%) [N = 653] | 21 (35.6) | 218 (36.7) | 0.866 |

| Paternal asthma in last 12 months, n (%) [N = 628] | 3 (5.2) | 29 (5.1) | 0.978 |

| Paternal allergy (allergy to pollen, house dust mite, food, or pets), n (%) [N = 638] | 16 (27.1) | 247 (42.7) | 0.021a |

| Siblings, n (%) with at least one [N = 727] | 55 (65.5) | 385 (59.9) | 0.323 |

| Pet ownership during pregnancy, n (%) [N = 728] | 29 (34.1) | 246 (38.3) | 0.459 |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy, n (%) [N = 727] | 6 (7.1) | 33 (5.1) | 0.442 |

| Maternal higher education, n (%) [N = 647] | 39 (66.1) | 444 (75.5) | 0.113 |

| Birth season, n (%) [N = 733] | 0.590 | ||

| Winter | 18 (20.5) | 148 (22.9) | |

| Spring | 20 (22.7) | 179 (27.8) | |

| Summer | 26 (29.5) | 173 (26.8) | |

| Autumn | 24 (27.3) | 145 (22.5) | |

| Age of the mother at birth, mean years (SD) | 32.5 (3.6) | 32.9 (4.3) | 0.491 |

| Ethnicity mother, n (%) Western [N = 658] | 54 (91.5) | 539 (90.0) | 0.705 |

| Ethnicity father, n (%) Western [N = 642] | 54 (93.1) | 531 (90.9) | 0.578 |

The only statistically significant results. SD = standard deviation.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the study population in the WHISTLER-online and usual care group

| WHISTLER-online (n = 323) | Usual care (n = 322) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) boys [N = 645] | 150 (46.4) | 158 (49.1) |

| Birth weight, mean grams (SD) [N = 645] | 3559.4 (509.9) | 3558.4 (490.9) |

| Birth length, mean cm (SD) [N = 606] | 50.6 (2.3) | 50.8 (2.2) |

| Gestational age, mean days (SD) [N = 645] | 278.7 (9.1) | 277.8 (9.8) |

| Maternal asthma in last 12 months, n (%) [N = 583] | 26 (8.7) | 18 (6.4) |

| Maternal allergy (allergy to pollen, house dust mite, food, or pets), n (%) [N = 594] | 110 (36.5) | 108 (36.9) |

| Paternal asthma in last 12 months, n (%) [N = 570] | 16 (5.6) | 13 (4.6) |

| Paternal allergy (allergy to pollen, house dust mite, food, or pets), n (%) [N = 579] | 127 (43.9) | 120 (41.4) |

| Siblings, n (%) with at least one [N=645] | 190 (58.8) | 197 (61.2) |

| Pet ownership during pregnancy, n (%) [N = 645] | 124 (38.4) | 124 (38.5) |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy, n (%) [N = 643] | 15 (4.6) | 18 (5.6) |

| Maternal higher education, n (%) [N = 588] | 227 (76.4) | 217 (74.6) |

| Birth season, n (%) [N = 645] | ||

| Winter | 76 (23.5) | 72 (22.4) |

| Spring | 90 (27.9) | 89 (27.6) |

| Summer | 93 (28.8) | 80 (24.8) |

| Autumn | 64 (19.8) | 81 (25.2) |

| Age of the mother at birth, mean years (SD) | 32.7 (4.0) | 33.0 (4.6) |

| Ethnicity mother, n (%) Western [N = 599] | 275 (90.8) | 264 (89.2) |

| Ethnicity father, n (%) Western [N = 584] | 268 (91.8) | 263 (90.1) |

SD = standard deviation.

Table 3.

Number of visits for respiratory symptoms per child and effect of WHISTLER-online on number of visits (primary outcome)

| WHISTLER-online (n = 314) | Usual care (n = 305) | IRRa (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visits for respiratory symptoms in first year, n (%) | ||||

| None | 156 (49.7) | 150 (49.2) | 0.96 (0.85 to 1.09) | 0.532 |

| 1 | 27 (8.6) | 27 (8.9) | ||

| 2 | 49 (15.6) | 39 (12.8) | ||

| 3 | 32 (10.2) | 37 (12.1) | ||

| >3 | 50 (15.9) | 52 (17.0) | ||

IRR for the effect of WHISTLER-online on the number of visits for RS. IRR = incidence rate ratio.

Table 4.

Secondary outcomes

| WHISTLER-online (n = 314) | Usual care (n = 305) | Relative risk (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants visiting the GP for LRS, n (%) | 68 (21.7) | 75 (24.6) | 0.88 (0.66 to 1.17) | 0.387 |

| Infants receiving asthma medication for RS, n (%) | 55 (17.5) | 46 (15.1) | 1.16 (0.81 to 1.67) | 0.413 |

| Infants receiving beta-2 agonists, n (%) | 55 (17.5) | 44 (14.4) | 1.21 (0.84 to 1.75) | 0.294 |

| Infants receiving antibiotics, n (%) | 64 (20.4) | 71 (23.3) | 0.88 (0.65 to 1.18) | 0.383 |

LRS = lower respiratory symptoms. RS = respiratory symptoms.

Additional subgroup analyses in infants with above-median days of wheezing or coughing did not differ from overall analysis (data not shown). The program had no disadvantages; percentages of hospital visits or admissions were comparable (WHISTLER-online versus usual care respectively 3.5% versus 6.2%, P = 0.11). The median degree of worries of the parents on the Likert scale was a bit lower in the WHISTLER-online group (for mothers 13 [interquartile range {IQR} 10–19] in the WHISTLER-online group compared with 14 [IQR 10–20] in the usual care group [P = 0.351], for fathers 12 [IQR 7–15] and 12 [IQR 9–18] respectively (P = 0.03). Two hundred and twenty-seven parents used the program (70.3%), of whom 100 used it twice or more (31%) (Table 5). Infants of program users were more often first children. Subgroups with different program use showed the same healthcare use. The first 215 WHISTLER-online families received an evaluation questionnaire, and 178 were returned (82%). Table 6 shows that 99% of parents found the information of the program clear, 78% could find the information they were looking for, and 90% thought the program would be useful for other parents. Only 9.6% changed their behaviour because of the program.

Table 5.

Differences between users and non-users of the program

| Non-users (n = 96) | Once used (n = 127) | Used >1 (n = 100) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, % | 47.4 | 41.7 | 51.0 | 0.367 |

| Birth weight, mean grams (SD) | 3603.1 (528.7) | 3484.8 (469.6) | 3605.4 (536.5) | 0.121 |

| Birth length, mean cm (SD) | 50.7 (2.4) | 50.4 (1.9) | 50.8 (2.7) | 0.303 |

| Gestational age, mean days (SD) | 277.2 (9.9) | 277.9 (8.7) | 281.0 (8.6) | 0.008a |

| Maternal asthma in last 12 months, % | 10.6 | 8.5 | 7.1 | 0.708 |

| Maternal allergy (allergy to pollen, house dust mite, food, or pets), % | 34.9 | 39.8 | 33.7 | 0.607 |

| Paternal asthma in last 12 months, % | 2.5 | 8.8 | 4.2 | 0.133 |

| Paternal allergy (allergy to pollen, house dust mite, food, or pets), % | 50.0 | 45.6 | 36.5 | 0.173 |

| Siblings, % with at least one | 70.1 | 60.3 | 45.0 | 0.001a |

| Pet ownership during pregnancy, % | 38.1 | 34.6 | 42.0 | 0.526 |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancy, % | 4.1 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 0.831 |

| Maternal higher education, % | 71.4 | 76.7 | 80.6 | 0.345 |

| Birth season, % | 0.837 | |||

| Winter | 25.8 | 25.2 | 19.0 | |

| Spring | 29.9 | 26.0 | 29.0 | |

| Summer | 24.7 | 30.7 | 30.0 | |

| Autumn | 19.6 | 18.1 | 22.0 | |

| Age of the mother at birth, mean years (SD) | 32.5 (3.9) | 33.2 (4.1) | 32.4 (3.8) | 0.231 |

| Ethnicity mother, % | 86.2 | 93.2 | 91.9 | 0.205 |

| Ethnicity father, % | 87.5 | 91.4 | 95.9 | 0.126 |

| Infants visiting the GP for respiratory symptoms in first year, % | 40.2 | 40.9 | 53.0 | 0.116 |

| Infants visiting the GP for lower respiratory symptoms in first year, % | 20.6 | 27.6 | 20.0 | 0.317 |

| Infants receiving beta-2 agonists first year, % | 17.5 | 19.7 | 22.0 | 0.733 |

| Infants receiving antibiotics first year, % | 24.7 | 23.6 | 19.0 | 0.585 |

The only statistically significant results. SD = standard deviation.

Table 6.

Percentage results from the evaluation questionnaire that parents of the WHISTLER-online group filled in when their child reached the age of 1 year

| Evaluation forms (n = 178 [82% returned]) | |

|---|---|

| Filled in by mother, % | 87.6 |

| Frequency of program use, % | |

| Never | 34.3 |

| Once | 36.0 |

| 2–3 times | 26.4 |

| >3 times | 3.4 |

| Reason for non-use (more options possible) (when applicable), % | |

| No time | 27.3 |

| Not interested | 13.6 |

| Child has no respiratory complaints | 51.5 |

| Not in need of information | 12.1 |

| Did not want to see the prediction score | — |

| Most interesting part (when applicable), % | |

| FAQ | 26.4 |

| Prediction score | 62.7 |

| Comparison of complaints | 10.9 |

| Clear information on program (when applicable), % yes | 99.1 |

| Possibility to find information that was needed (when applicable), % | |

| Yes | 77.5 |

| No | 1.3 |

| Partly | 21.3 |

| Behaviour changed (when applicable), % | |

| Yes, because of the information I went to the doctor | 3.8 |

| Yes, because of the information I did not go to the doctor | 5.8 |

| No, I wanted to go and I did | 65.4 |

| No, I did not want to go and I didn’t | 25.0 |

| More concerned because of the program, % | |

| No, my concerns stayed the same | 85.3 |

| No, my concerns decreased | 11.9 |

| Yes | 2.8 |

| Expect that other parents can use such a program, % | |

| Yes | 90.4 |

| No | 8.4 |

| No opinion | 1.2 |

| In need of other health-related programs, % | |

| Yes | 58.3 |

| No | 41.7 |

| Ever searched the internet for information on health problems in children % | |

| No | 16.2 |

| Yes | 83.8 |

DISCUSSION

WHISTLER-online, an online parental information program on respiratory illnesses in infants, showed similar healthcare consumption to usual care, despite parents’ use and appreciation of the program.

This study has several strengths. It is thought that this is the first randomised clinical trial in which the effect of internet-provided information for parents on common symptoms in infants on healthcare utilisation was compared with usual care. The program was personalised and all the parents received an individual introduction from one of the researchers. Parents were involved in the development of the program. Furthermore, only 4% loss to follow-up occurred, thus there was minimal risk of selection bias. Data on primary care visits and prescriptions were obtained from the GPs’ electronic patient files. There was standardisation in primary care, as all GPs used ICPC coding for every consultation and were unaware of the allocation.

There are also limitations. This randomised clinical trial was embedded in the ongoing WHISTLER-study. A high percentage of mothers in WHISTLER are highly educated (college or university) and this applied even more so for the participants of WHISTLER-online. Although it is expected that the findings will hold for less educated parents, the findings might only be generalisable to middle and high socioeconomic class families. Because more children of one family can participate in WHISTLER, siblings were allocated to the same family intervention. With respect to the small numbers of twins and siblings, the intervention groups were comparable, and additional analyses accounting for clustering effects showed no differences. Parents were unaware of randomisation and of study outcomes to prevent their behaviour from being influenced. The intervention was not harmful and parents themselves decided to use the program or not. It is the opinion of the authors that this study design was the only possible way to receive reliable information. The proportion of infants that consulted the physician (with their parents) for respiratory symptoms was lower than previously seen in the cohort; however, the mean number of consultations per infant per year was higher. As there was no difference at all between the interventions, this had not influenced the outcome.

The power calculation was based on a clinically meaningful reduction of consultations. A larger study might statistically demonstrate a small reduction with public health and economic implications.

Very little evidence exists for the use of web-based health information on healthcare utilisation. No randomised clinical trial was found that studied the effect of online health information on healthcare consumption in a general population. In contrast, there have been randomised clinical trials in patients with specific diseases like asthma, depression, or diabetes.30–32 The primary outcome of these trials was most often quality of life or clinical improvement. In some of these, hospitalisations and emergency department visits were studied but with inconsistent results.30 Some randomised clinical trials aimed to assess the effectiveness of information leaflets on minor symptoms in children. A recent trial among children who already consulted primary care showed that an interactive booklet about childhood respiratory tract infections led to a reduction in antibiotic prescribing and reconsultations.33 Other studies only found a limited effect of an information booklet on consultations34 or did not show an effect at all.35 None of these studies used the internet, and information was not individualised. Some studies, only two exclusively on children,20,23 analysed the way the internet interacts in healthcare consumption and especially in replacing health care. Some of these showed the use of internet to increase healthcare consumption,21 while others showed a decrease22,23 or no effect at all.20,24,25

A recent review demonstrated that, in order to be most effective, interventions to influence parental consulting and antibiotic use should engage children, occur prior to an illness episode, and provide guidance on specific symptoms.36 While this intervention meets these recommendations, one of the reasons that this program did not influence healthcare behaviour could be that there is already so much information on the internet. Although it was developed with the input of parents, and most parents judged it as clear and complete, the content may not fully connect to the desired information. However, this program was individualised with personal instructions. Personal information in particular is generally highly valued,37 and in this study parents appreciated the risk score the most. Parents are interested in trustworthy health information on the internet.38 However, such information seems to be used as a supplement to health services rather than as a replacement. Indeed, a recent study showed that paediatricians’ advice was more completely followed by parents than other sources of information.39 Although almost all parents used the internet to find health information, only a few followed most of the advice provided there.39 It could also be that a child’s symptoms can lead parents to make emotional rather than rational decisions on whether to consult a physician. This study emphasises the irreplaceability of direct contact with doctors. Many healthcare organisations spend substantial resources on building online information systems. This study showed no effect of an online e-support program on reducing healthcare utilisation for respiratory symptoms in an unselected population of young families.

Although parents appreciate the information, this study suggests that an online information program on respiratory illnesses in infants does not reduce healthcare consumption.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the parents and children who participated, and Mrs Rolien Bekkema and Mrs Liesbeth van der Feltz-Minkema from the Department of Paediatric Pulmonology, for assisting in recruiting the subjects and collecting the data, and Mrs Myriam Olling-de Kok from the Department of Paediatric Pulmonology, University Medical Center Utrecht, for assisting in secretarial work.

Funding

The WHISTLER study is supported by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZON-MW, nr 80-82315-98-09008), by the University Medical Center Utrecht, and by an unrestricted research grant from GlaxoSmithKline, the Netherlands. The funding agencies did not have any role in study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or the writing of the article and the decision to submit it for publication.

Ethical approval

The medical ethics committee of the University Medical Centre Utrecht approved the study. Written informed parental consent was obtained from all parents. Trial registration: Dutch trial register, number NTR1590.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

Cornelius van der Ent has received unrestricted research grants from Grünenthal and GlaxoSmithKline. Theo Verheij has received unrestricted research grants and fees for participation on an advisory board from Pfizer. The other authors have no competing interests to disclose.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Renahy E, Parizot I, Chauvin P. Health information seeking on the Internet: a double divide? Results from a representative survey in the Paris metropolitan area, France, 2005–2006. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larner AJ. Searching the Internet for medical information: frequency over time and by age and gender in an outpatient population in the UK. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(4):186–188. doi: 10.1258/135763306777488816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkinson NL, Saperstein SL, Pleis J. Using the internet for health-related activities: findings from a national probability sample. J Med Internet Res. 2009 doi: 10.2196/jmir.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMullan M. Patients using the Internet to obtain health information: how this affects the patient-health professional relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63(1–2):24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldman RD, Macpherson A. Internet health information use and e-mail access by parents attending a paediatric emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(5):345–348. doi: 10.1136/emj.2005.026872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson R, Baird W, Davis-Reynolds L, et al. Qualitative analysis of parents’ information needs and psychosocial experiences when supporting children with health care needs. Health Info Libr J. 2008;25(1):31–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2007.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khoo K, Bolt P, Babl FE, et al. Health information seeking by parents in the Internet age. J Paediatr Child Health. 2008;44(7–8):419–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2008.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Semere W, Karamanoukian HL, Levitt M, et al. A pediatric surgery study: parent usage of the Internet for medical information. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(4):560–564. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2003.50122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernhardt JM, Felter EM. Online pediatric information seeking among mothers of young children: results from a qualitative study using focus groups. J Med Internet Res. 2004 doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.1.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jong BM, van der Ent CK, van Putte Katier N, et al. Determinants of health care utilization for respiratory symptoms in the first year of life. Med Care. 2007;45(8):746–752. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180546879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen J, Dyas J, Jones M. Minor illness in children: parents’ views and use of health services. Br J Community Nurs. 2002;7(9):462–468. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2002.7.9.10657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monto AS. Epidemiology of viral respiratory infections. Am J Med. 2002;112(Suppl 6A):4S–12S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)01058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mallol J, Garcia-Marcos L, Solé D, Brand P. International prevalence of recurrent wheezing during the first year of life: variability, treatment patterns and use of health resources. Thorax. 2010;65(11):1004–1009. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.115188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuhlbrigge AL, Adams RJ, Guilbert TW, et al. The burden of asthma in the United States: level and distribution are dependent on interpretation of the national asthma education and prevention program guidelines. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(8):1044–1049. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens CA, Turner D, Kuehni CE, et al. The economic impact of preschool asthma and wheeze. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(6):1000–1006. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00057002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arroll B, Kenealy T. Antibiotics for the common cold and acute purulent rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD000247. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000247.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spurling GK, Fonseka K, Doust J, Del Mar C. Antibiotics for bronchiolitis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;1:CD005189. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005189.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chavasse R, Seddon P, Bara A, McKean M. Short acting beta agonists for recurrent wheeze in children under 2 years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3:CD002873. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panickar J, Lakhanpaul M, Lambert PC, et al. Oral prednisolone for preschool children with acute virus-induced wheezing. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(4):329–338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouche G, Migeot V. Parental use of the Internet to seek health information and primary care utilisation for their child: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:300. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholson W, Gardner B, Grason HA, Powe NR. The association between women’s health information use and health care visits. Women’s Health Issues. 2005;15(6):240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eastin MS, Guinsler NM. Worried and wired: effects of health anxiety on information-seeking and health care utilization behaviors. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2006;9(4):494–498. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azocar F, McCabe JF, Wetzel JC, Schumacher SJ. Use of a behavioral health web site and service utilization. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(1):18. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagner TH, Hibbard JH, Greenlick MR, Kunkel L. Does providing consumer health information affect self-reported medical utilization? Evidence from the Healthwise Communities Project. Med Care. 2001;39(8):836–847. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner TH, Greenlick MR. When parents are given greater access to health information, does it affect pediatric utilization? Med Care. 2001;39(8):848–855. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katier N, Uiterwaal CS, de Jong BM, et al. The Wheezing Illnesses Study Leidsche Rijn (WHISTLER): rationale and design. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19(9):895–903. doi: 10.1023/B:EJEP.0000040530.98310.0c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Jong BM. University of Utrecht. 2008. Lower respiratory tract illness in young children: predictors of disease and health care utilization; pp. 76–88. Thesis/dissertation. http://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/25922 (accessed 19 Nov 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verbeke M, Schrans D, Deroose S, De Maeseneer J. The International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC-2): an essential tool in the EPR of the GP. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2006;124:809–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Jong BM, van der Ent CK, van der Zalm MM, et al. Respiratory symptoms in young infancy: child, parent and physician related determinants of drug prescription in primary care. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(7):610–618. doi: 10.1002/pds.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stinson J, Wilson R, Gill N, et al. A systematic review of internet-based self-management interventions for youth with health conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(5):495–510. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boren SA, Gunlock TL, Peeples MM, Krishna S. Computerized learning technologies for diabetes: a systematic review. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008;2(1):139–146. doi: 10.1177/193229680800200121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF. Delivering interventions for depression by using the internet: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;328(7434):265. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37945.566632.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Francis NA, Butler CC, Hood K, et al. Effect of using an interactive booklet about childhood respiratory tract infections in primary care consultations on reconsulting and antibiotic prescribing: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Little P, Somerville J, Williamson I, et al. Randomised controlled trial of self management leaflets and booklets for minor illness provided by post. BMJ. 2001;322(7296):1214–1216. 1217. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heaney D, Wyke S, Wilson P, et al. Assessment of impact of information booklets on use of healthcare services: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322(7296):1218–1221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrews T, Thompson M, Buckley DI, et al. Interventions to influence consulting and antibiotic use for acute respiratory tract infections in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaw E, Howard M, Chan D, et al. Access to web-based personalized antenatal health records for pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30(1):38–43. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32711-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ayantunde AA, Welch NT, Parsons SL. A survey of patient satisfaction and use of the Internet for health information. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(3):458–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moseley KL, Freed GL, Goold SD. Which sources of child health advice do parents follow? Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2011;50(1):50–56. doi: 10.1177/0009922810379905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]