Abstract

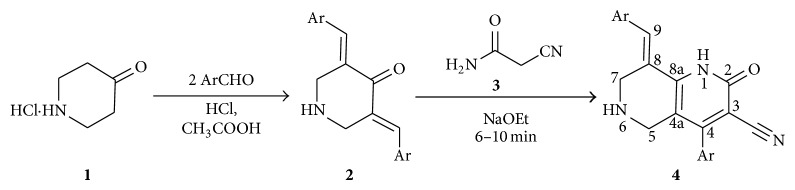

A series of hexahydro-1,6-naphthyridines were synthesized in good yields by the reaction of 3,5-bis[(E)-arylmethylidene]tetrahydro-4(1H)-pyridinones with cyanoacetamide in the presence of sodium ethoxide under simple mixing at ambient temperature for 6–10 minutes and were assayed for their acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitory activity using colorimetric Ellman's method. Compound 4e with methoxy substituent at ortho-position of the phenyl rings displayed the maximum inhibitory activity with IC50 value of 2.12 μM. Molecular modeling simulation of 4e was performed using three-dimensional structure of Torpedo californica AChE (TcAChE) enzyme to disclose binding interaction and orientation of this molecule into the active site gorge of the receptor.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is associated with loss of cholinergic neurons in basal forebrain, which results in loss or failure of memory which slowly worsens and eventually incapacitates the patients [1, 2]. According to the World Alzheimer report, AD is one among the most significant social, health, and economic crises of the 21st century [3]. Although the exact factors initiating AD are unclear, genetic and environmental factors have been implicated [4]. In general, pharmacological therapies have twin objectives: (i) to prevent the loss of the neurons and (ii) to restore the cholinergic functions of AD patients. Cholinesterase inhibitors have been used clinically for symptomatic treatment of AD [5]. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme is involved in the breakdown of acetylcholine in the brain and inhibition of this enzyme may increase the efficacy of treatment and broaden the indications [6]. Effects of cholinesterase inhibitors are mainly due to enhancement of cholinergic transmission at cholinergic autonomic synapses and at the neuromuscular junction [7].

AChE inhibitors are one of the most actively investigated classes of compounds in the search for an effective treatment of AD. Although there are many ongoing research activities in the search of drugs for treating AD, only few drugs like galantamine, donepezil, and rivastigmine are now available [8], and these drugs do not show potential cure rates; additional treatments are still being developed. The treatment of AD still remains an area of significant unmet need, with drugs that only target the symptoms of the disease. Therefore, there is considerable need for disease-modifying therapies. To meet the need of disease-modifying drugs for AD, in recent years, new approaches have emerged in medicinal chemistry. In particular the concept has recently been proposed that due to the multifactorial and complex etiology of AD, the modulation of a single factor might not be sufficient to produce the desired efficacy. Researchers are now paying attention to the design of structures that could be able to simultaneously interact with different targets involved in the pathogenic process [9, 10].

Naphthyridine structural motif has been extensively synthesized and incorporated into biologically active molecules [11]. In particular, 1,6-naphthyridines exhibit a broad spectrum of biological activities such as being inhibitor of HIV-1 integrase [12, 13], HCMV [14, 15], FGF receptor-1 tyrosine kinase [16], and the enzyme acetylcholinesterase [17]. Many routes for the syntheses of 1,6-naphthyridines derivatives have previously been reported [18–21]. In continuation of our previous work towards the synthesis of novel hybrid heterocycles employing new synthetic methodologies and/or their potential as inhibitors of AChE [22–26], herein we report the synthesis and AChE inhibitory activities of nitrogen heterocyclic hybrids comprising naphthyridine structural motif.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemistry

General Methods. Melting points were measured in KRUSS melting point meter using open capillary tubes and are uncorrected. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 300 MHz instrument in DMSO using TMS as internal standard. Standard Bruker software was used throughout. Chemical shifts are given in parts per million (δ-scale) and the coupling constants are given in Hertz. IR spectra were recorded in a Perkin Elmer system 2000 FT IR instrument (KBr). Elemental analyses were performed on a Perkin Elmer 2400 Series II Elemental CHNS analyser. Mass spectra were recorded in Agilent technologies 7820A GC-MS system.

2.1.1. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Naphthyridines (4a–k)

A mixture of 3,5-bis[(E)-arylmethylidene]tetrahydro-4(1H)-pyridinones (1 mmol) and 2-cyanoacetamide (1 mmol) in ethanol (200 μL) in the presence of catalytic amount of sodium ethoxide (5 mg) were ground well in a semimicro boiling tube at ambient temperature for about 6–10 min. After completion of the reaction as evident from TLC, water (50 mL) was added to the reaction mixture and the product was filtered, washed with water, and dried in vacuo.

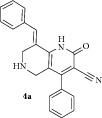

(E)-8-Benzylidene-2-oxo-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6,7,8-hexahydro-1,6-naphthyridine-3-carbonitrile ( 4a ). Pale yellow solid; IR (KBr) ν max 3372, 2945, 2213, 1642, 1625 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO): δ H 3.15 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.35 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.60 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 3.69 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 7.07–7.38 (m, 10H, Ar-H), 7.81 (s, 1H, Arylmethylidene-H), 8.15 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO): δ C 45.48, 45.76, 79.31, 101.70, 115.22, 116.94, 126.21, 127.81, 128.84, 129.50, 130.78, 131.10, 134.71, 135.54, 137.90, 146.85, 159.18, 162.83. EIMS: m/z 341 [M+1]. Anal. calcd for C22H17N3O: C, 77.86; H, 5.05; N, 12.38; found: C, 77.69; H, 5.22; N, 12.25%.

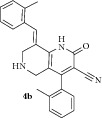

(E)-8-(2-Methylbenzylidene)-2-oxo-4-(o-tolyl)-1,2,5,6,7,8-hexahydro-1,6-naphthyridine-3-carbonitrile ( 4b ). Yellow solid; IR (KBr) ν max 3380, 2948, 2210, 1640, 1627 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO): δ H 2.13 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.30 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.14 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.33 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.62 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 3.68 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 7.04–7.35 (m, 8H, Ar-H), 7.80 (s, 1H, Arylmethylidene-H), 8.14 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO): δ C 19.75, 20.56, 45.43, 45.82, 79.76, 101.32, 115.23, 116.91, 126.21, 127.03, 127.79, 128.89, 129.33, 129.53, 129.92, 130.78, 131.19, 134.76, 135.42, 135.55, 137.91, 146.96, 159.08, 162.92. EIMS: m/z 369 [M+1]. Anal. calcd for C24H21N3O: C, 78.45; H, 5.76; N, 11.44; found: C, 78.32; H, 5.98; N, 11.29%.

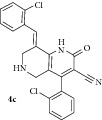

(E)-8-(2-Chlorobenzylidene)-4-(2-chlorophenyl)-2-oxo-1,2,5,6,7,8-hexahydro-1,6-naphthyridine-3-carbonitrile ( 4c ). Pale yellow solid; IR (KBr) ν max 3384, 2950, 2214, 1642, 1625 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO): δ H 3.16 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.34 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.61 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 3.68 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 7.10–7.36 (m, 8H, Ar-H), 7.81 (s, 1H, Arylmethylidene-H), 8.12 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO): δ C 45.38, 45.95, 79.70, 101.64, 115.21, 116.90, 126.28, 127.01, 127.85, 128.90, 129.31, 129.54, 129.93, 130.69, 131.26, 134.73, 135.40, 135.52, 137.90, 146.91, 159.13, 162.90. EIMS: m/z 408 [M+1]. Anal. calcd for C22H15Cl2N3O: C, 64.72; H, 3.70; N, 10.29; found: C, 64.80; H, 3.87; N, 10.48%.

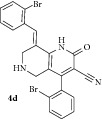

(E)-8-(2-Bromobenzylidene)-4-(2-bromophenyl)-2-oxo-1,2,5,6,7,8-hexahydro-1,6-naphthyridine-3-carbonitrile ( 4d ). Pale yellow solid; IR (KBr) ν max 3381, 2950, 2210, 1644, 1626 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO): δ H 3.18 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.34 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.62 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 3.69 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 7.16–7.39 (m, 8H, Ar-H), 7.82 (s, 1H, Arylmethylidene-H), 8.09 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO): δ C 44.93, 45.80, 79.78, 101.61, 115.20, 116.96, 126.25, 127.05, 127.81, 128.98, 129.35, 129.62, 129.92, 130.73, 131.24, 134.71, 135.43, 135.51, 137.93, 146.90, 159.17, 162.92. EIMS: m/z 498 [M+1]. Anal. calcd for C22H15Br2N3O: C, 53.15; H, 3.04; N, 8.45; found: C, 53.38; H, 3.16; N, 8.37%.

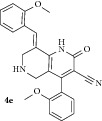

(E)-8-(2-Methoxybenzylidene)-4-(2-methoxyphenyl)-2-oxo-1,2,5,6,7,8-hexahydro-1,6-naphthyridine-3-carbonitrile ( 4e ). Yellow solid; IR (KBr) ν max 3385, 2944, 2210, 1641, 1627 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO): δ H 3.14 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.31 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.60 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 3.68 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 3.74 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.82 (s, 3H, OCH3), 7.11–7.38 (m, 8H, Ar-H), 7.83 (s, 1H, Arylmethylidene-H), 8.10 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO): δ C 45.39, 45.93, 55.51, 55.70, 79.70, 101.67, 114.20, 114.81, 115.20, 116.94, 126.31, 127.81, 128.93, 129.56, 130.66, 131.29, 134.70, 135.42, 137.90, 146.95, 159.07, 159.14, 160.04, 162.95. EIMS: m/z 401 [M+1]. Anal. calcd for C24H21N3O3: C, 72.16; H, 5.30; N, 10.52; found: C, 72.30; H, 5.53; N, 10.39%.

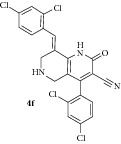

(E)-8-(2,4-Dichlorobenzylidene)-4-(2,4-dichlorophenyl)-2-oxo-1,2,5,6,7,8-hexahydro-1,6-naphthyridine-3-carbonitrile ( 4f ). Pale yellow solid; IR (KBr) ν max 3380, 2951, 2219, 1646, 1628 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO): δ H 3.18 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.37 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.60 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 3.68 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 7.14–7.42 (m, 6H, Ar-H), 7.82 (s, 1H, Arylmethylidene-H), 8.09 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO): δ C 45.35, 45.97, 79.65, 101.62, 115.26, 116.81, 126.30, 127.12, 127.87, 128.94, 129.43, 129.60, 129.94, 130.74, 131.27, 134.72, 135.47, 135.53, 137.94, 146.97, 159.16, 162.95. EIMS: m/z 478 [M+1]. Anal. calcd for C22H13Cl4N3O: C, 55.38; H, 2.75; N, 8.81; found: C, 55.29; H, 2.92; N, 8.70%.

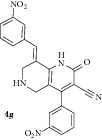

(E)-8-(3-Nitrobenzylidene)-4-(3-nitrophenyl)-2-oxo-1,2,5,6,7,8-hexahydro-1,6-naphthyridine-3-carbonitrile ( 4g ). Yellow solid; IR (KBr) ν max 3389, 2942, 2210, 1645, 1626 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO): δ H 3.21 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.39 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.61 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 3.70 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 7.12–7.38 (m, 8H, Ar-H), 7.80 (s, 1H, Arylmethylidene-H), 8.11 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO): δ C 45.32, 45.95, 79.66, 101.60, 115.24, 116.79, 126.31, 127.15, 127.86, 128.93, 129.41, 129.64, 129.96, 130.75, 131.30, 134.71, 135.49, 135.61, 137.92, 146.95, 159.14, 162.93. EIMS: m/z 431 [M+1]. Anal. calcd for C22H15N5O5: C, 61.54; H, 3.52; N, 16.31; found: C, 61.27; H, 3.75; N, 16.18%.

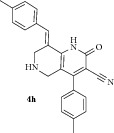

(E)-8-(4-Methylbenzylidene)-2-oxo-4-(p-tolyl)-1,2,5,6,7,8-hexahydro-1,6-naphthyridine-3-carbonitrile ( 4h ). Pale yellow solid; IR (KBr) ν max 3387, 2940, 2212, 1647, 1625 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO): δ H 2.25 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.29 (s, 3H, CH3), 3.20 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.41 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.63 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 3.72 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 7.12–7.40 (m, 8H, Ar-H), 7.83 (s, 1H, Arylmethylidene-H), 8.12 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO): δ C 21.4, 21.8, 45.35, 45.97, 79.68, 101.64, 115.25, 116.80, 126.32, 127.18, 127.82, 128.91, 129.45, 129.96, 130.69, 131.35, 134.73, 135.47, 135.64, 137.90, 139.21, 146.94, 159.17, 162.90. EIMS: m/z 369 [M+1]. Anal. calcd for C24H21N3O: C, 78.45; H, 5.76; N, 11.44; found: C, 78.66; H, 5.87; N, 11.35%.

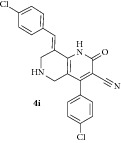

(E)-8-(4-Chlorobenzylidene)-4-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-oxo-1,2,5,6,7,8-hexahydro-1,6-naphthyridine-3-carbonitrile ( 4i ). Yellow solid; IR (KBr) ν max 3385, 2942, 2210, 1645, 1627 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO): δ H 3.17 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.40 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.62 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 3.71 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 7.16–7.48 (m, 8H, Ar-H), 7.87 (s, 1H, Arylmethylidene-H), 8.15 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO): δ C 45.39, 45.94, 79.70, 101.65, 115.26, 116.81, 126.34, 127.21, 127.85, 128.94, 129.48, 129.91, 130.76, 131.39, 134.71, 135.51, 135.60, 137.90, 146.92, 159.25, 162.97. EIMS: m/z 409 [M+1]. Anal. calcd for C22H15Cl2N3O: C, 64.72; H, 3.70; N, 10.29; found: C, 64.95; H, 3.84; N, 10.21%.

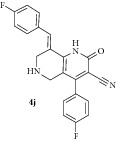

(E)-8-(4-Fluorobenzylidene)-4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-oxo-1,2,5,6,7,8-hexahydro-1,6-naphthyridine-3-carbonitrile ( 4j ). Pale yellow solid; IR (KBr) ν max 3387, 2940, 2213, 1645, 1624 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO): δ H 3.15 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.37 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.63 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 3.70 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 7.13–7.45 (m, 8H, Ar-H), 7.84 (s, 1H, Arylmethylidene-H), 8.11 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO): δ C 45.37, 45.93, 79.72, 101.64, 114.36, 114.58, 115.23, 116.85, 126.37, 127.84, 128.92, 129.45, 130.72, 131.35, 134.78, 135.43, 137.94, 146.96, 159.25, 160.23, 161.18, 162.95. EIMS: m/z 377 [M+1]. Anal. calcd for C22H15F2N3O: C, 70.39; H, 4.03; N, 11.19; found: C, 70.65; H, 4.27; N, 11.10%.

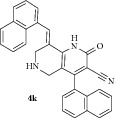

(E)-4-(Naphthalen-1-yl)-8-(naphthalen-1-ylmethylene)-2-oxo-1,2,5,6,7,8-hexahydro-1,6-naphthyridine-3-carbonitrile ( 4k ). Pale yellow solid; IR (KBr) ν max 3384, 2946, 2214, 1645, 1629 cm−1; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO): δ H 3.17 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.41 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H, 5-CH2), 3.61 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 3.70 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H, 7-CH2), 7.02–7.65 (m, 14H, Ar-H), 7.91 (s, 1H, Arylmethylidene-H), 8.17 (s, 1H, NH). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO): δ C 45.31, 45.84, 79.68, 101.65, 115.28, 116.80, 123.46, 124.03, 125.12, 125.57, 126.30, 126.42, 126.80, 127.20, 127.85, 128.22, 129.12, 129.48, 129.94, 130.79, 131.43, 132.10, 132.67, 134.73, 135.54, 135.68, 137.92, 146.90, 159.28, 162.94. EIMS: m/z 441 [M+1]. Anal. calcd for C30H21N3O: C, 81.98; H, 4.82; N, 9.56; found: C, 81.80; H, 4.95; N, 9.48%.

2.2. In Vitro Cholinesterase Enzymes Inhibitory Assay

Cholinesterase inhibitory activity of the synthesized compounds was evaluated using the Ellman's microplate assay [27]. For acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitory assay, 140 μL of 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8) was first added to a 96-well microplate followed by 20 μL of test samples and 20 μL of 0.09 units/mL acetylcholinesterase enzyme from Electrophoruselectricus (Sigma). After 15 minutes of incubation at 25°C, 10 μL of 10 mM 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) was added into each well followed by 10 μL of acetylthiocholine iodide (14 mM). At 30 minutes after the initiation of enzymatic reaction, absorbance of the colored end-product was measured using BioTek Power Wave X 340 Microplate Spectrophotometer at 412 nm.

Galantamine was used as positive control. Test samples and galantamine were prepared in DMSO at an initial concentration of 1 mg/mL (1000 ppm). The concentration of DMSO in final reaction mixture was 1%. At this concentration, DMSO has no inhibitory effect on acetylcholinesterase enzyme.

The initial screening was carried out at 10 μg/mL of test samples in 1% DMSO and each test was conducted in triplicate. Absorbencies of the test samples were corrected by subtracting the absorbance of their respective blank. Percentage enzyme inhibition is calculated using the following formula:

| (1) |

Subsequently, the determination of IC50 was carried out using a set of five concentrations.

2.3. Molecular Modeling

Using Glide (version 5.7, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2011), most active compound was docked onto the active site of TcAChE derived from three-dimensional structure of the enzyme complex with anti-Alzheimer's drug, galantamine (PDB ID: 4EVE).

Water molecules and hetero groups were deleted from enzyme beyond the radius of 5 Å of reference ligand (galantamine), resulting protein structure refined and minimized by Protein Preparation Wizard using OPLS-2005 force field. Receptor Grid Generation program was used to prepare TcAChE grid and the ligand was optimized by LigPrep program by using OPLS-2005 force field to generate lowest energy state. Docking stimulations were carried out on bioactive compound, handed in 5 poses per ligand, in which the best pose with highest score was displayed for each ligand.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemistry

In the present investigation, the reaction of a series of bisarylmethylidene piperidones with 2-cyanoacetamide in the presence of sodium ethoxide with few drops of ethanol under simple mixing at ambient temperature for 6–10 min afforded functionalized 1,6-naphthyridines in good yields (65–78%; Scheme 1). The prerequisite bisarylmethylidene piperidones were synthesized following the literature reported method [28]. In a typical reaction, an equimolar mixture of 3,5-bis[(E)-2-methylphenylmethylidene]tetrahydro-4(1H)-pyridinones (2b) and 2-cyanoacetamide (3) in catalytic amount of sodium ethoxide were ground well in a semimicro boiling tube with few drops of ethanol at ambient temperature for about 7 min and after completion of the reaction water was added to the mixture and the product was filtered and dried in vacuo. In this case, the 2-pyridone was obtained as a sole reaction product and does not require column chromatography for purification. Easy availability of the reagents, short reaction time, and simple reaction condition rendered this method more attractive from the viewpoint of green chemistry.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of naphthyridines (4a–k).

The structure of 1,6-naphthyridines was elucidated using IR, NMR, and CHN analysis. In the 1H NMR spectrum of 4b, the two doublets at 3.14 and 3.33 ppm with J = 15.9 Hz are due to 5-CH2 protons while the other doublets at 3.62 and 3.68 ppm with J = 15.6 Hz are due to 7-CH2 protons of the piperidine ring. The singlets at 8.14 and 7.80 ppm can be attributed to the NH of 2-pyridone ring and arylmethylidene proton, respectively. The two –CH3 protons of aromatic ring appear as singlets at 2.13 and 2.30 ppm while the multiplets around 7.04–7.35 ppm are due to aromatic protons. In the 13C NMR spectrum, the chemical shifts at 19.75 and 20.56 ppm were due to the two –CH3 carbons whilst the two methylene carbons of the piperidine ring resonated at 45.43 and 45.82 ppm. The aromatic carbons resonated at 101.32–162.92 ppm. The molecular ion peak at 369 [M+1] confirms the presence of compound 4b. The elemental analysis result of 4b was within ±0.4% of the theoretical values. The structure of other 2-pyridones was also assigned by similar considerations. Presumably, the 1,6-naphthyridine (4) is formed via a cascade heterocyclization mechanism involving an initial Michael addition followed by cyclization and air oxidation as reported by Jain et al. [29].

3.2. In Vitro Evaluation

All newly synthesized 1,6-naphthyridines were evaluated in vitro for their inhibitory potential against AChE enzyme from electric eel using colorimetric Ellman's method (Table 1). All the 1,6-naphthyridines (4a–k) displayed good to moderate inhibitory activities with IC50 values ranging from 2.12 to 24.72 μM, irrespective of the position of the substituent on the aryl ring. Among the 1,6-naphthyridines, compounds 4i with p-chloro, 4k with 1-naphthyl, 4h with p-methyl, and 4b with o-methyl substituent in the aromatic ring displayed good activities (<10 μM) with IC50 3.86 μM, 6.86 μM, 7.16 μM, and 7.20 μM, respectively. Compounds 4a, 4c, 4d, 4g, and 4j displayed moderate activities (IC50 = 11.18–18.16 μM) while compound 4f displayed the lowest activity (IC50 = 24.72 μM). Compound 4e with o-methoxy phenyl rings displayed the highest activity with IC50 value of 2.12 μM, comparable to the standard drug galantamine (IC50 = 2.09 μM). It is also observed that the AChE inhibitory activities were directly correlated to the size of substituents in the phenyl ring. For instance, derivative bearing bulky moieties, such as m-nitro, o,p-dichloro, and p-bromo, displayed lower inhibition than the derivatives carrying smaller functions irrespective of their position in the phenyl ring.

Table 1.

Physical data and AChE inhibitory activity of naphthyridines (4a–k).

| Entry | Product | Reaction time (min) | Yield (%) |

mp °C | AChE inhibition (IC50 ± SD) mol/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

8 | 75 | 211-212 | 11.18 ± 0.02 |

|

| |||||

| 2 |

|

7 | 72 | 229-230 | 7.20 ± 0.02 |

|

| |||||

| 3 |

|

7 | 76 | 220-221 | 15.21 ± 0.1 |

|

| |||||

| 4 |

|

6 | 70 | 208-209 | 18.16 ± 0.02 |

|

| |||||

| 5 |

|

9 | 67 | 215-216 | 2.12 ± 0.02 |

|

| |||||

| 6 |

|

6 | 72 | 225-226 | 24.72 ± 0.01 |

|

| |||||

| 7 |

|

6 | 70 | 206-207 | 16.86 ± 0.02 |

|

| |||||

| 8 |

|

7 | 73 | 235-236 | 7.16 ± 0.02 |

|

| |||||

| 9 |

|

6 | 78 | 221-222 | 3.86 ± 0.02 |

|

| |||||

| 10 |

|

7 | 74 | 218-219 | 14.16 ± 0.02 |

|

| |||||

| 11 |

|

10 | 65 | 204-205 | 6.86 ± 0.02 |

|

| |||||

| 12 | Galantamine.HBr | — | — | — | 2.09 ± 0.02 |

The active site of AChE enzyme is located inside a 20 Å long, narrow gorge which is dominantly composed of amino acids possessing aromatic side chains such as tryptophan and tyrosine. Therefore, the derivatives bearing a relatively small and/or electron donating moieties in phenyl rings, such as methyl and methoxy, displayed better inhibitory activities than derivatives carrying bulky and/or electron withdrawing groups, plausibly due to the better insertion into the active site channel and also more efficient binding interaction with aforementioned aromatic residues. However with limited substituent on the aryl ring, it is difficult to ascertain the exact structure activity relationship based on their activities observed.

3.3. Docking Studies

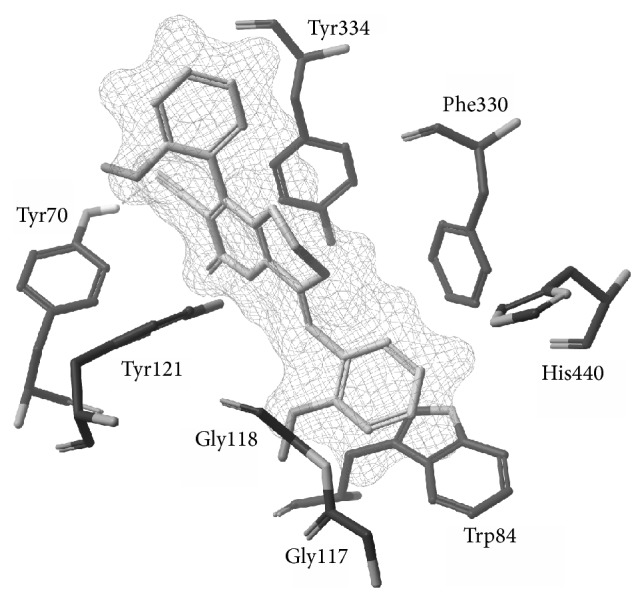

The most active AChE inhibitor, 4e, was docked into the active site of AChE enzyme derived from crystal structure of Torpedo californica AChE (TcAChE). The docking analysis revealed that this compound is properly inserted into the active site of AChE enzyme with free binding energy of 8.71 kcal/mol and strongly bound to the residues comprising aromatic side chains such as Tyr70 (H-bonding 1.16 Å), Tyr121 (hydrophobic), Tyr334 (hydrophobic) at peripheral anionic site as well as Phe330 (hydrophobic), and Trp84 (π,π-stacking) at choline binding site of the enzyme (Figure 1). 4e also exhibited mild polar interaction with Gly116 and Gly117 at oxyanion hole of the AChE enzyme. The crystal structure of the TcAChE in complex with available AD drugs such as galantamine and huperzine A showed similar interactions with residues composing peripheral anionic site along with stacking against Trp84 at bottom of the gorge. It seems that the presence of methoxy group in 4e has notable influence on proper positioning of this compound in AChE active site. This orientation effectively avoids insertion and hydrolysis of substrate inside the AChE active site channel and completely coincides with the activity observed for this compound.

Figure 1.

Binding interaction of 4e with active site of AChE receptor. (Hydrogen atoms are not shown for clarity.)

4. Conclusion

A series of novel 1,6-naphthyridines were synthesized in good yields and evaluated for their inhibitory potentials against AChE enzyme, using colorimetric Ellman's method. Among them, compound 4e displayed the highest AChE inhibition with remarkable IC50 value of 2.12 μM, comparable to standard drug, galantamine. Molecular modeling analysis for this compound manifested its orientation inside the active site cavity and its effective binding interactions to the residues lining the active site channel, which coincided with its in vitro activity.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for the Research Grant RGP-VPP-026.

Conflict of Interests

The authors confirm that this paper content has no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Nordberg A. Biological markers and the cholinergic hypothesis in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 1992;85(139):54–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1992.tb04455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terry A. V., Jr., Buccafusco J. J. The cholinergic hypothesis of age and Alzheimer's disease-related cognitive deficits: recent challenges and their implications for novel drug development. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2003;306(3):821–827. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.041616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prince M., Bryce R., Ferri C. World Alzheimer Report 2011: The Benefits of Early Diagnosis and Intervention. London, UK: Alzheimer's Disease International (ADI); 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson P. T., Head E., Schmitt F. A., et al. Alzheimer's disease is not ‘brain aging’: neuropathological, genetic, and epidemiological human studies. Acta Neuropathologica. 2011;121(5):571–587. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0826-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabet N. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease: anti-inflammatories in acetylcholine clothing! Age and Ageing. 2006;35(4):336–338. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giacobini E. Cholinesterase inhibitors: new roles and therapeutic alternatives. Pharmacological Research. 2004;50(4):433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giacobini E. Invited review. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease therapy: from tacrine to future applications. Neurochemistry International. 1998;32(5-6):413–419. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(97)00124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rampa A., Piazzi L., Belluti F., et al. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: SAR and kinetic studies on omega-[N-methyl-N-(3-alkylcarbamoyloxyphenyl)methyl]-amino-alkoxyaryl derivatives. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2001;44(23):3810–3820. doi: 10.1021/jm010914b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morphy R., Rankovic Z. Designed multiple ligands. An emerging drug discovery paradigm. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2005;48(21):6523–6543. doi: 10.1021/jm058225d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavalli A., Bolognesi M. L., Minarini A., et al. Multi-target-directed ligands to combat neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;51(7):347–372. doi: 10.1021/jm800210c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larner A. J. Alzheimer's disease: targets for drug development. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 2002;2(1):1–9. doi: 10.2174/1389557023406593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melamed J. Y., Egbertson M. S., Varga S., et al. Synthesis of 5-(1-H or 1-alkyl-5-oxopyrrolidin-3-yl)-8-hydroxy-[1,6]-naphthyridine-7-carboxamide inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2008;18(19):5307–5310. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egbertson M. S., Moritz H. M., Melamed J. Y., et al. A potent and orally active HIV-1 integrase inhibitor. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2007;17(5):1392–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falardeau G., Lachance H., Pierre A. S., et al. Design and synthesis of a potent macrocyclic 1,6-napthyridine anti-human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) inhibitors. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2005;15(6):1693–1695. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan L., Jin H., Stefanac T., et al. Discovery of 1,6-naphthyridines as a novel class of potent and selective human cytomegalovirus inhibitors. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1999;42(16):3023–3025. doi: 10.1021/jm9902483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson A. M., Connolly C. J. C., Hamby J. M., et al. 3-(3,5-Dimethoxyphenyl)-1,6-naphthyridine-2,7-diamines and related 2-urea derivatives are potent and selective inhibitors of the FGF receptor-1 tyrosine kinase. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2000;43(22):4200–4211. doi: 10.1021/jm000161d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanlaer S., Voet A., Gielens C., de Maeyer M., Compernolle F. Bridged 5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-1,6-naphthyridines, analogues of huperzine A: synthesis, modelling studies and evaluation as inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase. European Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2009;(5):643–654. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200800972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jachak M. N., Bagul S. M., Kazi M. A., Toche R. B. Novel synthetic protocol toward pyrazolo[3,4-h]-[1,6] naphthyridines via Friedlander condensation of new 4-aminopyrazolo[3,4-b] pyridine-5-carbaldehyde with reactive α-methylene ketones. Journal of Heterocyclic Chemistry. 2011;48(2):295–300. doi: 10.1002/jhet.242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rote R. V., Bagul S. M., Shelar D. P., Patil S. R., Toche R. B., Jachak M. N. Synthesis of benzo[3,4-h][1,6]naphthyridines via Friedländer condensation with active methylenes. Journal of Heterocyclic Chemistry. 2011;48(2):301–307. doi: 10.1002/jhet.391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toche R. B., Pagar B. P., Zoman R. R., Shinde G. R., Jachak M. N. Synthesis of novel benzo[h][1,6]naphthyridine derivatives from 4-aminoquinoline and cyclic β-ketoester. Tetrahedron. 2010;66(27-28):5204–5211. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2010.04.085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandra A., Singh B., Upadhyay S., Singh R. M. Copper-free Sonogashira coupling of 2-chloroquinolines with phenyl acetylene and quick annulation to benzo[b][1,6] naphthyridine derivatives in aqueous ammonia. Tetrahedron. 2008;64(51):11680–11685. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basiri A., Murugaiyah V., Osman H., Kumar R. S., Kia Y., Ali M. A. Microwave assisted synthesis, cholinesterase enzymes inhibitory activities and molecular docking studies of new pyridopyrimidine derivatives. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry. 2013;21(11):3022–3031. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kia Y., Osman H., Kumar R. S., et al. A facile chemo-, regio- and stereoselective synthesis and cholinesterase inhibitory activity of spirooxindole-pyrrolizine-piperidine hybrids. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2013;23(10):2979–2983. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basiri A., Murugaiyah V., Osman H., et al. An expedient, ionic liquid mediated multi-component synthesis of novel piperidone grafted cholinesterase enzymes inhibitors and their molecular modeling study. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2013;67:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar R. S., Ramar A., Perumal S., Almansour A. I., Arumugam N., Ali M. A. Three-component synthesis and 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of highly functionalized pyrans with nitrile oxides: easy access to 1,2,4-oxadiazoles. Synthetic Communications. 2013;43(20):2763–2772. doi: 10.1080/00397911.2012.740647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar R. S., Almansour A. I., Arumugam N., et al. An expedient synthesis and screening for antiacetylcholinesterase activity of piperidine embedded novel pentacyclic cage compounds. Medicinal Chemistry. 2014;10(2):228–236. doi: 10.2174/157340641002140131170054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellman G. L., Courtney K. D., Andres V., Jr., Featherstone R. M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1961;7(2):88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dimmock J. R., Padmanilayam M. P., Puthucode R. N., et al. A conformational and structure-activity relationship study of cytotoxic 3,5-bis(arylidene)-4-piperidones and related N-acryloyl analogues. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2001;44(4):586–593. doi: 10.1021/jm0002580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jain R., Roschangar F., Ciufolini M. A. A one-step preparation of functionalized 3-cyano-2-pyridones. Tetrahedron Letters. 1995;36(19):3307–3310. doi: 10.1016/0040-4039(95)00615-J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]