ABSTRACT

The transcription factor NF-κB is important for HIV-1 transcription initiation in primary HIV-1 infection and reactivation in latently HIV-1-infected cells. However, comparative analysis of the regulation and function of NF-κB in latently HIV-1-infected cells has not been done. Here we show that the expression of IκB-α, an endogenous inhibitor of NF-κB, is enhanced by latent HIV-1 infection via induction of the host-derived factor COMMD1/Murr1 in myeloid cells but not in lymphoid cells by using four sets of latently HIV-1-infected cells and the respective parental cells. IκB-α protein was stabilized by COMMD1, which attenuated NF-κB signaling during Toll-like receptor ligand and tumor necrosis factor alpha treatment and enhanced HIV-1 latency in latently HIV-1-infected cells. Activation of the phosphoinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)–JAK pathway is involved in COMMD1 induction in latently HIV-1-infected cells. Our findings indicate that COMMD1 induction is the NF-κB inhibition mechanism in latently HIV-1-infected cells that contributes to innate immune deficiency and reinforces HIV-1 latency. Thus, COMMD1 might be a double-edged sword that is beneficial in primary infection but not beneficial in latent infection when HIV-1 eradication is considered.

IMPORTANCE HIV-1 latency is a major barrier to viral eradication in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. In this study, we found that COMMD1/Murr1, previously identified as an HIV-1 restriction factor, inhibits the proteasomal degradation of IκB-α by increasing the interaction with IκB-α in latently HIV-1-infected myeloid cells. IκB-α protein was stabilized by COMMD1, which attenuated NF-κB signaling during the innate immune response and enhanced HIV-1 latency in latently HIV-1-infected cells. Activation of the PI3K-JAK pathway is involved in COMMD1 induction in latently HIV-1-infected cells. Thus, the host-derived factor COMMD1 is beneficial in suppressing primary infection but enhances latent infection, indicating that it may be a double-edged sword in HIV-1 eradication.

INTRODUCTION

HIV/AIDS could be a controllable infectious disease, in part because of drug developmental research for >30 years. Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), the standard regimen for HIV/AIDS, improves patients' life prognosis by blocking the HIV-1 life cycle at several steps and suppressing the viral load to an undetectable level (1, 2). However, cART cannot completely cure HIV/AIDS. HIV-1 can invade the host immune system and circumvent cART by obtaining several mutations in the viral genome and establishing latent infection in viral target cells (3). Therefore, HIV/AIDS patients are required to take cART drugs throughout their lifetimes. To eradicate HIV-1 in patients and achieve a complete cure of HIV/AIDS, examination of the molecular mechanism of HIV-1 latency is essential (4).

Latent HIV-1 infection is established by the transcriptional repression of integrated HIV-1 genes in HIV-1 reservoirs such as CD4 T cells, monocyte-macrophage lineage cells, and myeloid dendritic cells (5). HIV-1 gene expression is regulated mainly by activation of the long terminal repeat (LTR) after integration into the host genome. As inducible transactivators of HIV-1, HIV-1-derived transcription factor Tat and host-derived transcription factors NF-κB, NFAT, AP-1, and SP1 directly bind to the HIV-1 LTR and transactivate HIV-1 gene expression by forming the transcriptional initiation complex including p-TEFb (2). Tat is a critical transcriptional activator of HIV-1 gene expression in productive viral replication. Tat mutations were identified in latently HIV-1-infected cell lines and cART-treated HIV/AIDS patients (6–8). The importance of NF-κB, NFAT, and AP-1 binding to the HIV-1 LTR was confirmed by examining the frequency of in vitro latent HIV-1 infection. HIV-1 obtains mutations in these host-derived transcription factor binding sites in the LTR (9, 10). In particular, a recent study revealed that NF-κB activation is critical for transcription of the HIV-1 precursor mRNA that encodes Tat during primary HIV-1 infection prior to Tat-dependent full-length HIV-1 transcription, including the accessory and structural genes for Vpu and Gag (11). Uninfected resting CD4 T cells, a major latent-HIV-1 reservoir, showed the cytosolic retention of NF-κB and NFAT that is necessary for HIV-1 latency (2). Thus, the suppression of Tat and host-derived transcription factors such as NF-κB is thought to be required for the establishment of latent HIV-1 infection. Although the role of host-derived transcription factors in latently HIV-1-infected cells has been extensively studied, a comparative analysis of latently HIV-1-infected cells and parental cells has not been reported.

NF-κB is one of the most crucial host-derived transcription factors in HIV-1 replication, as mentioned above. Generally, NF-κB regulates diverse physiological functions, especially in the host defense against pathogen infection via its target genes (12), and then finally regulates innate and acquired immune responses. NF-κB transcriptional factors are dimers produced by a combination of five different monomers (p65, p50, p52, c-Rel, and RelB) (13). The representative NF-κB p65/p50 heterodimer is retained in the cytoplasm by binding to IκB-α and is consequently inactivated at the steady-state level. During the activation of upstream receptors such as cytokines and Toll-like receptors (TLRs), IκB-α is phosphorylated by the IKK complex and ubiquitinated by E3 ubiquitin ligase βTrcP1/2 and MIB1 (14–16). Ubiquitinated IκB-α is degraded by proteasomes and releases NF-κB, which translocates to the nucleus and transactivates target genes (13). During primary HIV-1 infection, NF-κB is identified as the initial transcription factor that is crucial for de novo synthesis of HIV-1 proteins such as Tat, Rev, and Nef (2, 11). Cytokines and TLR agonists also induce transient activation of NF-κB and reactivate HIV-1 replication in latently infected cells (17–20). Additionally, targeting of the NF-κB inhibitor IκB-α reactivates HIV-1 gene expression in latently infected cells (21). The baseline expression of NF-κB correlated with latent infection susceptibility (9). In the epigenetic gene silencing of HIV-1, the p50 homodimer binds to NF-κB-responsive elements in the LTR region and recruits histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), which enhances histone deacetylation and heterochromatin formation (22). Although the involvement of NF-κB in HIV-1 latency has been elucidated, a comparative analysis of the expression and function of NF-κB in latently HIV-1-infected cells and parental cells has not been done yet.

COMMD1/Murr1 has multiple functions in the regulation of protein stability at the cell membrane and in the cytoplasm (23). COMMD1 regulates ion homeostasis by binding to the epithelial sodium ion channel (ENaC) and the chloride ion channel cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (24–26). COMMD1 also regulates copper and zinc ion metabolism by binding to the copper ion channel ATP7A/B and is involved in the activation of superoxide dismutase 1, which is correlated with Wilson's disease (27–29). COMMD1 also regulates NF-κB signaling via its dual regulation in the cytosol and the nucleus (30). COMMD1 interacts with IκB-α to inhibit IκB-α proteasomal degradation in the cytosol and also with p65 to promote p65 nucleolar retention and proteasomal degradation (31–33). Interestingly, COMMD1 was previously identified as an HIV-1 restriction factor by its inhibition of NF-κB-dependent HIV-1 replication in primary HIV-1 infection via stabilization of IκB-α protein (34, 35). Among several HIV-1 restriction factors (APOPBEC3, TRIM5α, BST-2, SAMHD1, etc.), COMMD1 has a unique character in that it directly affects HIV-1 gene transcription through NF-κB regulation as a function of HIV-1 restriction (36). However, the expression and function of COMMD1 and other HIV-1 restriction factors in latently HIV-1-infected cells have not been investigated, although their expression and suppressive functions in primary HIV-1 infection have been well elucidated.

Here, we showed that IκB-α expression is enhanced by latent HIV-1 infection via induction of COMMD1 transcription in myeloid cell lines by using four sets of latently HIV-1-infected cells and the respective parental cells. NF-κB signaling and the cytokine response upon TLR and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) receptor stimulation were suppressed in latently HIV-1-infected U1 cells compared with those in parental U937 cells. Latent HIV-1 infection-induced COMMD1 expression positively correlated with IκB-α stabilization and maintenance of HIV-1 latency. Constitutive activation of the JAK/phosphoinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway was involved in COMMD1 induction in latently HIV-1-infected U1 cells. These results suggest that COMMD1 induction is the molecular mechanism of NF-κB inhibition in latently HIV-1-infected myeloid lineage cells. These findings raise the possibility that while HIV-1 host factors have beneficial effects on primary infection, they may have unfavorable effects on latent infection, especially in the context of HIV-1 eradication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies.

Poly(I·C) and bacterial DNA were purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). Peptidoglycan (PGN) from Staphylococcus aureus was obtained from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli O111:B4 was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). R848 was from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA). Recombinant human TNF-α, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and IL-6 were from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Alpha interferon (IFN-α) and IFN-β were provided by Astellas Pharma (Tokyo, Japan) and Toray Industries (Chiba, Japan). IFN-γ was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). LY294002 was from Wako (Tokyo, Japan), and Pan-JAK inhibitor was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. SP600125, SB203580, and PD98059 were from Wako (Osaka, Japan). Bortezomib was from Selleck Chemicals LLC (Houston, TX). Antibodies to p65 (sc-372), p50 (sc-114), MIB1 (sc-393811), β-Trcp1/2 (sc-15354), p300 (sc-584), γ-tubulin (sc-7396), normal mouse IgG (sc-2025), and normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies to IκB-α (9242), calnexin (2679), and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti-COMMD1 antibody (ab58322) was from Abcam Japan (Tokyo, Japan). Anti-Hsc70 (SPA-815) and anti-Hsp90 (SPA-830) antibodies were from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY). Anti-HDAC1 antibody (607401) was from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). Ubiquitinated-protein antibody was from Affiniti Bioreagents (Golden, CO).

Cell culture, treatment, and transfection.

Human promyeloid U937 and HL60 cells and human Jurkat T lymphocytes were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Human A3.01 T lymphocytes, latently HIV-1-infected U1 cells (derived from U937 cells), OM10.1 (HL60) cells, J1.1 (Jurkat) cells, J-Lat10.6 cells, and ACH2 (A3.01) cells were supplied by the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH (Rockville, MD). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen Japan, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Stimulation of cells with 10 μg/ml TLR agonists in serum-free medium was performed for 12 or 24 h. Treatment with 10 μg/ml of R848 and LPS was carried out at the times indicated. At the time of treatment, the culture medium was replaced with fresh, serum-free RPMI containing R848 and LPS. Treatment of U937 and U1 cells with bortezomib was performed for 2 h (proteasome activity assay), 6 h (Western blotting), or 24 h (3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide [MTT] assay). Cycloheximide (CHX) was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). For chase experiments, cells were treated with 0.5 mM CHX and cells were harvested immediately (0 h) or 1, 3, or 6 h after CHX treatment. For bortezomib treatment, cells were treated with 100 nM bortezomib or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; control) and cotreated with 0.5 mM CHX for 6 h. Cell lysates were collected immediately (0 h) or 6 h after treatment. The transfection of plasmids and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) into U1 cells with the AMAXA nucleofection system (Cologne, Germany) was performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Briefly, 1,000 μM si-COMMD1 and si-IκB-α duplex was transfected into 1 × 106 cells to knock down COMMD1 and IκB-α, respectively, for siRNA transfection. A negative-control siRNA (si-con, MISSION siRNA Universal Negative Control; Sigma-Aldrich, Tokyo, Japan) was also used. The cells were harvested 48 h after transfection. The siRNA oligonucleotide sequences are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. For plasmid transfection, 2 μg of pcDNA3.1 and hemagglutinin (HA)-COMMD1 was transfected into 1 × 106 cells. The pcDNA3.1 empty vector was used as a control.

MTT assay.

The antiproliferative activities of bortezomib against U937 and U1 cells were measured by the MTT method (Sigma-Aldrich). Briefly, 2 × 104 cells were incubated in triplicate in a 96-well microculture plate in the presence of different concentrations of bortezomib in a final volume of 0.1 ml for 24 h at 37°C. Subsequently, MTT (0.5 mg/ml, final concentration) was added to each well. After 3 h of additional incubation, 100 μl of a solution containing 10% SDS plus 0.01 N HCl was added to dissolve the crystals. Absorbance at 595 nm was determined with an automatic enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plate reader (Multiskan; Thermo Electron, Vantaa, Finland). Values are normalized to untreated (control) samples.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from cells with RNAiso Plus (TaKaRa Bio, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) analyses for TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, COMMD1, IκB-α, HIV-1 Tat-Rev, MIB1, βTrcp1, βTrcp2, ISG15, PML, SAMHD1, BST2, Apopbec3F/G, PKR, p21, and internal control 18S rRNA were carried out with Fast SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) by following the manufacturer's instructions. PCR amplifications were performed as described previously. The CT values for each gene amplification were normalized by subtracting the CT value calculated for 18S rRNA. The normalized gene expression values were expressed as the relative quantity of each gene-specific mRNA. The oligonucleotide primers used in the real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) amplifications are shown in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

Flow cytometric analysis.

Cell suspensions were prepared in staining medium (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] with 3% fetal bovine serum and 0.05% sodium azide) and stained with monoclonal antibodies as described above (37). After 30 min of incubation on ice, the cells were washed twice with washing medium, fixed in PBS with 0.1% paraformaldehyde for 20 min in the dark, and permeabilized in PBS with 0.01% saponin. After 10 min of incubation on ice, cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-HIV-1 p24 monoclonal antibody (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) for 30 min on ice. After being stained, the cells were analyzed on an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). Data were analyzed with FlowJo (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA) software.

Western blotting, immunoprecipitation, and fractionation.

To analyze COMMD1, IκB-α, MIB1, βTrcp1/2, p300, p-p85, p85, p110α, p110β, p110γ, p110δ, p-PTEN, p-PDK1, p-Akt, pJNK, JNK, p-p38, p38, p-ERK, ERK, and Hsc70 protein expression, we performed immunoblotting essentially as previously reported (38). For Western blotting of p65 and γ-tubulin, nuclear extracts were prepared from cells as previously described (39). The extraction efficiency was confirmed by comparison with a fractionation kit (Subcellular Protein Fractionation Kit for Cultured Cells; Thermo, Rockford, IL) as shown in Fig. S1F in the supplemental material. Protein samples were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. After blocking, the membrane was probed with the appropriate antibodies and the blot was visualized with Chemi-Lumi One Super (Nakalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan). To analyze the interaction of p65, COMMD1, and IκB-α, cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer as previously described (5). Cytosol extracts were incubated for 12 h at 4°C with 2 μg of anti-p65, anti-COMMD1, or control IgG immobilized on protein G Sepharose beads (Amersham Bioscience, Sweden). Immunoprecipitates were washed, eluted, and subjected to immunoblotting essentially by following our previously reported protocol. Blots of immunoprecipitate samples or the input fraction were probed with anti-p65, anti-IκB-α, anti-COMMD1, or anti-Hsc70 antibody (for the input fraction). For fractionation of COMMD1 protein, cytosol, membrane, and nuclear fractions were recovered with the Subcellular Protein Fractionation Kit for Cultured Cells (Thermo, Rockford, IL). Each fraction was subjected to immunoblotting. Fractionation efficiency was confirmed by the expression of each positive control by following the manufacturer's recommendations (Hsp90 for the cytosolic fraction, calnexin for the membrane fraction, and HDAC1 for the nuclear fraction).

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

Immunofluorescence staining was performed as previously reported (40). Briefly, cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde, permeabilized/blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin–0.05% Triton X-100–Tris-buffered saline, and immunostained for 2 h with 10 μg/ml of primary antibodies (anti-COMMD1, anti-IκB-α). Cells were then stained for 1.5 h with 2 μg/ml secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG [Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR]) at a 1:1,000 dilution. Finally, the nuclei were counterstained with 10 μg/ml of Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes) and the samples were mounted in PermaFluor aqueous mounting medium (Beckman Coulter, Marseille, France). Fluorescent images were acquired by BIOREVO BZ-9000 fluorescence microscopy (Keyence, Osaka, Japan).

ELISA.

The amount of p24 antigen in latently HIV-1-infected cells was determined with an HIV-1 p24 antigen ELISA kit (ZeptoMetrix Corp., Buffalo, NY) according to the manufacturer's protocol and our previous report (37). Briefly, the culture media of plasmids and siRNA-transfected cells were recovered and lysed with lysing buffer as the extracellular p24 sample. After removal of the medium, cells were washed by PBS two times and lysed with RIPA buffer to detect intracellular p24.

Proteasome activity assay.

For analysis of proteasome activity, U937 and U1 cells seeded onto 12-well plates were treated with or without bortezomib for 2 h. After being washed with PBS solution, the cell pellet was lysed on ice for 15 min in 200 μl lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES, 10 mM Na4P2O7·10H2O, 100 mM NaF, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1% Triton X-100). After clearing of cell debris by centrifugation at 4°C, the extract's (25 μg) proteasomal activity was assayed with the Proteasome-Glo cell-based assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol and a previous report (37). Briefly, each sample incubated with the luminogenic proteasome substrates Suc-LLVY-aminoluciferin (chymotrypsin-like activity), Z-LRR-aminoluciferin (trypsin-like activity), and Z-nLPnLD-aminoluciferin (caspase-like activity) for 30 min. Following cleavage by the proteasome, each substrate for luciferase (aminoluciferin) was released, allowing the luciferase reaction to proceed and produce light. Luminescence was measured on a Centro XS3 LB960 luminometer (Berthold Japan KK, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as mean values ± the standard errors (SE). For statistical analysis, the data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey-Kramer multiple-comparison test or Student's t test (JMP software; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) as indicated in the figure legends. A differences was considered statistically significant when the P value was <0.05.

RESULTS

IκB-α protein but not mRNA expression was increased in latently HIV-1-infected cells.

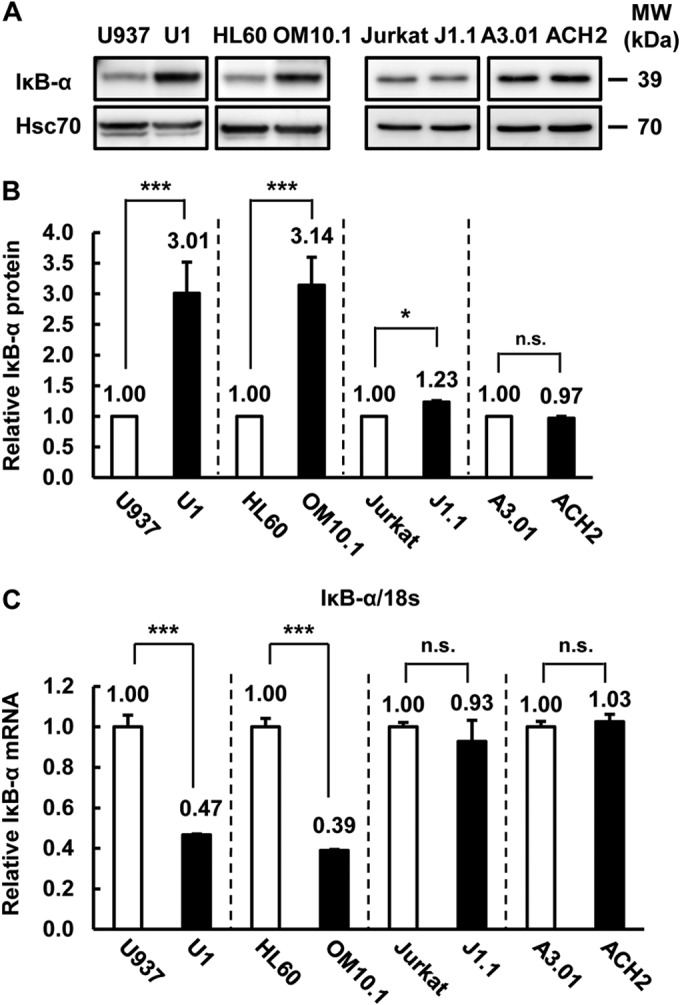

It was previously reported that reduction of IκB-α expression in latently HIV-1-infected cells reactivates HIV-1 replication and that low basal activity of NF-κB would be permissive for the establishment of latent HIV-1 infection (9, 21). However, there was no report comparing the expression level of IκB-α and NF-κB signaling between latently HIV-1-infected cells and their parental cells. Therefore, we first examined IκB-α protein and mRNA expression levels. IκB-α proteins were increased in latently HIV-1-infected myeloid cells (U937/U1, HL60/OM10.1) but not in lymphoid cells (Jurkat/J1.1, A3.01/ACH2) (Fig. 1A). Quantification of IκB-α proteins revealed that U1 and OM10.1 cells express a 3-fold higher level of IκB-α than the respective U937 and HL60 parental cells (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, the IκB-α mRNA level in latently HIV-1-infected myeloid cells was less than half of that in the parental cells. Lymphoid-derived J1.1 and ACH2 cells showed almost the same IκB-α protein and mRNA levels as the parental Jurkat and A3.01 cells, respectively (Fig. 1A and C). These results indicated that IκB-α protein was increased by latent HIV-1 infection of myeloid cells but not of lymphoid cells, which could affect the basal transcription of one of the NF-κB target genes, i.e., that for IκB-α (41) (Fig. 1C).

FIG 1.

IκB-α expression was increased by latent HIV-1 infection in myeloid cells. (A) IκB-α and Hsc70 protein expression was examined in latently HIV-1-infected cells (U1, OM10.1, J1.1, ACH2) and each parental cell line (U937, HL60, Jurkat, A3.01). Hsc70 was used as a loading control. MW, molecular mass. (B) IκB-α protein expression levels, relative to Hsc70 expression, in latently HIV-1-infected cells and parental cells determined with Image Gauge software (ver. 4.2; Fujifilm). Data are mean values ± SE from three independent experiments. (C) IκB-α mRNA expression was examined by qPCR. mRNA expression was normalized to that of human 18S RNA. Data are mean values ± SE from triplicate tests. For panels B and C, the P values were assessed by Student's t test. * and ***, P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively, versus parental cells. n.s., not significant.

Latent HIV-1 infection attenuated cytokine induction and NF-κB signaling.

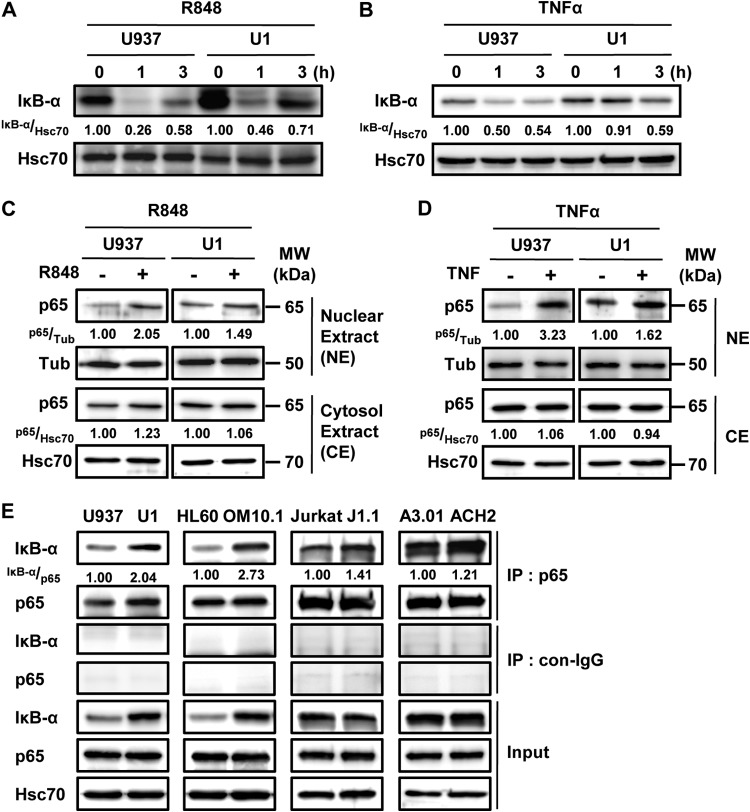

TLR agonists activate NF-κB signaling and induce cytokine expression (16). Previously, latently HIV-1-infected macrophages derived from U1 cells showed a cytokine response to LPS that was weaker than that of U937 cell-derived macrophages (42). Additionally, alveolar macrophages of HIV/AIDS patients also showed defective function compared with those of healthy donors (25, 43). In these experiments, phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) treatment was used for macrophage differentiation from monocytes. PMA is a diverse and strong signaling inducer and also affects HIV-1 reactivation (44). Consistently, we found that PMA stimulation affects IκB-α expression (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material), HIV-1 reactivation (see Fig. S1B and E in the supplemental material), and cytokine expression (see Fig. S1C and D) in U1 cells. We then compared the cytokine response to TLR agonists and TNF-α in steady-state (nondifferentiated) U937 and U1 cells to analyze the function of IκB-α induction in latently HIV-1-infected cells. TNF-α and IL-6 mRNA induction was statistically significantly suppressed in U1 cells compared with that in U937 cells at 12 and 24 h after TLR stimulation (Fig. 2A to D). Short-time-course treatment also showed the attenuated response to R848 in U1 cells compared with that in U937 cells at 1 to 6 h after stimulation (Fig. 2E and F). TNF-α-induced IL-1β and IL-8 expression was also significantly decreased in U1 cells (Fig. 2G and H). These results indicated that latent HIV-1 infection attenuates cytokine induction. Upon TLR and TNF-α receptor activation, IκB-α is immediately degraded by the proteasome. This releases an NF-κB such as the p65/p50 heterodimer from IκB-α, which translocates to the nucleus and transactivates its target genes (45). We next asked whether IκB-α degradation is affected by latent HIV-1 infection. Although R848 transiently decreased IκB-α protein levels in both U1 and U937 cells at 1 h after treatment, the reduction of IκB-α was attenuated in U1 cells (relative IκB-α expression level of 0.46) compared with that in U937 cells (relative expression level of 0.26) (Fig. 3A). Additionally, we also analyzed the activation of NF-κB by examining the nuclear expression of p65. Associated with the inhibition of IκB-α decrease, nuclear p65 induction was attenuated in U1 cells (relative p65 expression level of 1.49) compared with that in U937 cells (relative expression level of 2.05) (Fig. 3C). These effects were also observed upon TNF-α (Fig. 3B and D) and LPS (data not shown) treatments. Consistent with the induction of IκB-α by latent HIV-1 infection, the interaction of IκB-α and p65 was 2-fold higher in U1 cells than in U937 cells, as well as in OM10.1 compared with HL60 (Fig. 3E). Although the comparison of IκB-α expression showed a small but statistically significant increase in J1.1 compared with Jurkat cells and relatively similar levels in ACH2 and A3.01 cells, the interaction of IκB-α and p65 was slightly increased in latently HIV-1-infected cell (Fig. 1B and 3E). Therefore, other mechanisms might be involved in increasing the interaction of IκB-α and p65 in lymphoid cell types without increasing the expression of IκB-α. These results suggested that the increased IκB-α protein caused by latent HIV-1 infection could attenuate NF-κB signaling and its downstream cytokine induction by increasing the interaction of IκB-α and p65 in latently HIV-1-infected myeloid cells.

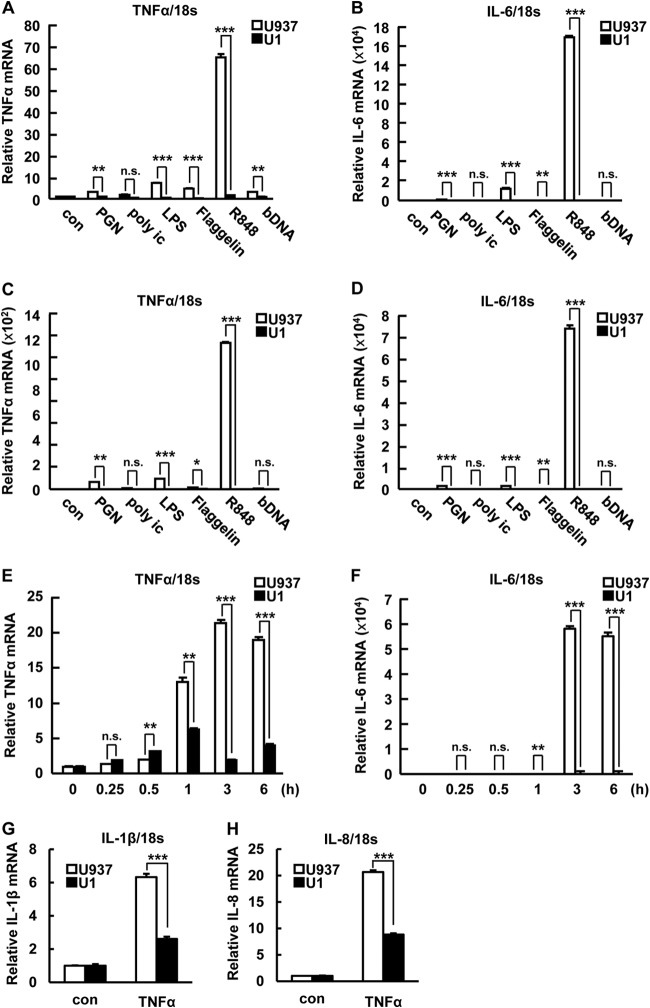

FIG 2.

IκB-α induction attenuates cytokine induction by TLR agonist and cytokine stimulation. (A to D) TNF-α (A, C) and IL-6 (B, D) mRNA expression was examined in U937 and U1 cells treated with 10 μg/ml of TLR agonists [PGN, poly(I·C), LPS, flagellin, R848, CpG DNA] for 12 h (A, B) or 24 h (C, D). (E, F) TNF-α (E) and IL-6 (F) mRNA expression was examined in U937 and U1 cells treated with R848 for the times indicated. (G, H) IL-1β (G) and IL-8 (H) mRNA expression was examined in U937 and U1 cells treated with 10 μg/ml of TNF-α for 12 h. mRNA expression was normalized to that of human 18S RNA. Data are mean values ± SE from triplicate tests. For panels A to H, the P values were assessed by Student's t test. con, control. *, **, and ***, P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively, versus U937 cells. n.s., not significant.

FIG 3.

IκB-α induction attenuates NF-κB activation by TLR agonist and cytokine stimulation. (A, B) U937 and U1 cells were treated with R848 (A) and TNF (B) for 0, 1, or 3 h, and the expression of IκB-α and Hsc70 was examined by Western blotting. (C, D) U937 and U1 cells were treated with R848 (C) and TNF-α (D) for 1 h, and the nuclear expression of p65 and γ-tubulin was examined by Western blotting. γ-Tubulin expression was used as a loading control. (E) IκB-α and p65 interaction was examined in latently HIV-1-infected cells (U1, OM10.1, J1.1, ACH2) and each parental cell line (U937, HL60, Jurkat, A3.01) by immunoprecipitation. Band intensity was quantified with Image Gauge software, and the relative ratios of the proteins indicated are shown in panels A to E. MW, molecular mass; con, control; IP, immunoprecipitate.

IκB-α protein stability was increased in latently HIV-1-infected myeloid cells but not in lymphoid cells.

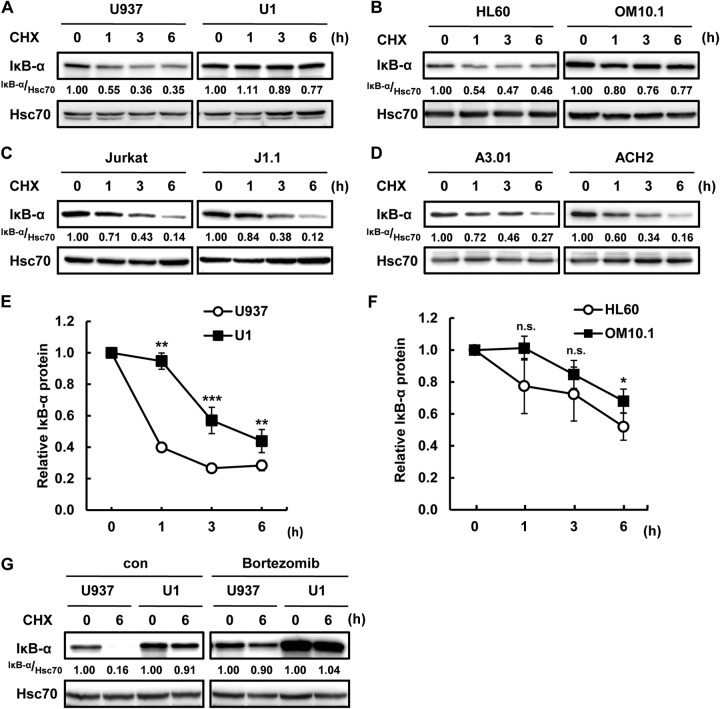

Because the induction of IκB-α in latently HIV-1-infected myeloid cells occurs at the protein level but not at the mRNA level, we next probed the effect of latent HIV-1 infection on the stability of IκB-α protein. We compared the degradation of IκB-α in latently HIV-1-infected cells with that in the respective parental cells by focusing on the proteasomal degradation of IκB-α (12). Interestingly, IκB-α protein stability was increased in latently HIV-1-infected myeloid cells (U937/U1, HL60/OM10.1) but not in lymphoid cells (Jurkat/J1.1, A3.01/ACH2) on the basis of the quantification of IκB-α protein expression (Fig. 4A to D). To further analyze the protein stability of IκB-α, we calculated the half-life of IκB-α protein in U937 and U1 cells by quantification of IκB-α protein expression upon treatment with CHX (Fig. 4E). The half-life of IκB-α protein in U937 cells was almost 1 h, while that in U1 cell was 5 h. The half-life of IκB-α protein was also extended in HL60 compared with that in OM10.1 cells (Fig. 4F). Additionally, the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib suppressed the degradation of IκB-α in both U937 and U1 cells (Fig. 4G). These results indicated that IκB-α protein stabilization via inhibition of IκB-α proteasomal degradation could affect the increased expression of IκB-α in latently HIV-1-infected myeloid cells. On the other hand, IκB-α degradation was not affected by latent HIV-1 infection in lymphoid cells, which is consistent with the basal IκB-α protein expression level (Fig. 1A, C, and D).

FIG 4.

Increased IκB-α protein stability in latently HIV-1-infected cells. (A to D) Latently HIV-1-infected cells and each parental cell line were treated with CHX for 0, 1, 3, or 6 h, and IκB-α expression was examined. Hsc70 was used as a loading control. Panels A to D show U937/U1, HL60/OM10.1, Jurkat/J1.1, and A3.01/ACH2, respectively. (E, F) Quantification of IκB-α expression in pairs of U937/U1 (E) and HL60/OM10.1 (F) immunoblot assays. Data are mean values ± SE from three independent experiments. The P values were assessed by Student's t test. *, **, and ***, P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively, versus U937 and HL60. n.s., not significant. (G) U937 and U1 cells were pretreated or not treated with bortezomib for 1 h and treated with CHX for 6 h. IκB-α and Hsc70 expression was analyzed by Western blotting. Band intensity was quantified with Image Gauge software, and the relative ratios of the proteins indicated are shown in panels A to D and G. con, control.

Latent HIV-1 infection does not affect the expression of E3 ubiquitin ligase of IκB-α and proteasomal protease activity.

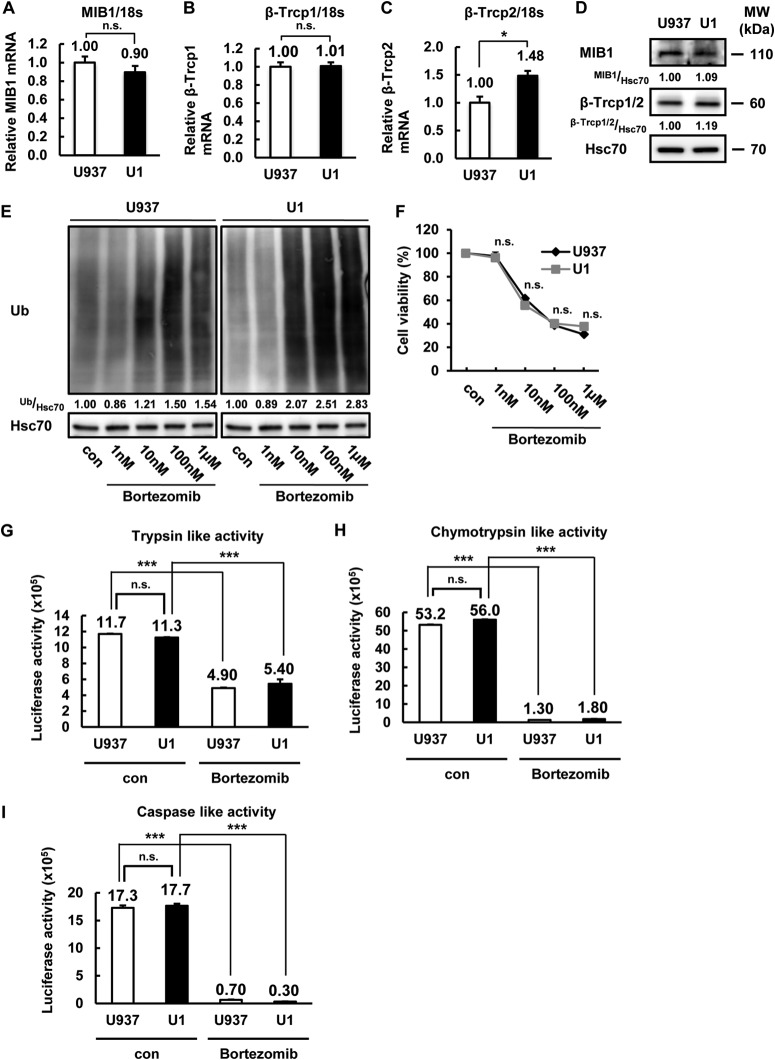

To address the molecular mechanism of IκB-α stabilization in latently HIV-1-infected cells, we focused on the E3 ubiquitin ligase of IκB-α. MIB1, βTrcp1, and βTrcp2 were previously identified as the IκB-α E3 ubiquitin ligases that induce the proteasomal degradation of IκB-α (14, 15). However, the mRNA expression levels of these E3 ubiquitin ligases were not lower in U1 cells than in U937 cells (Fig. 5A to C). Consistent with the mRNA levels, levels of MIB1, βTrcp1, and βTrcp2 protein expression were not lower in U1 cells than in U937 cells (Fig. 5D). Therefore, we next analyzed the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and the cytotoxic effect of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, which are relative markers of proteasome activity (46). Although the ubiquitinated-protein accumulation caused by bortezomib treatment was slightly (1.8-fold) higher in U1 cells than in U937 cells (Fig. 5E), the cellular sensitivity to the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib based on its cytotoxic effect showed that the effect of bortezomib on cellular growth inhibition was the same in these cells (Fig. 5F). Additionally, we analyzed the chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like, and caspase-like proteasomal protease activities in U937 and U1 cells. Although bortezomib clearly suppressed the activity of all of the proteasomal proteases in both cell lines, latent HIV-1 infection did not significantly affect protease activity (Fig. 5G to I). These results indicated that the stabilization of IκB-α is not due to the inhibition of IκB-α E3 ligase expression or proteasome activity.

FIG 5.

The E3 ligases of IκB-α expression and proteasomal proteinase activity were not affected by latent HIV-1 infection. (A to C) MIB1 (A) and βTrcp1/2 (B, C) mRNA expression in U937 and U1 cells was examined by qPCR. mRNA expression was normalized to that of human 18S RNA. Data are mean values ± SE from triplicate tests. (D) MIB1, βTrcp1/2, and Hsc70 protein expression was examined in U937 and U1 cells. Hsc70 was used as a loading control. Band intensity was quantified with Image Gauge software, and the relative ratios of MIB1 and βTrcp1/2 to Hsc70 are shown. (E, F) U937 and U1 cells were incubated for 24 h with the bortezomib doses indicated. Ubiquitinated (Ub)-protein expression was examined in U937 and U1 cells treated with increasing dose of bortezomib. Band intensity was quantified with Image Gauge software, and the relative ratios of ubiquitinated proteins to Hsc70 are shown (E). Cell proliferation assays were carried out with MTT (F). (G to I) Proteasomal proteinase (trypsin-like [G], chymotrypsin-like [H], and caspase-like [I]) activities were examined in U937 and U1 cells pretreated or not treated with bortezomib for 1 h. Luciferase activity was determined and is expressed as fold activation over that of the DMSO-treated group used as a control. Data are mean values ± SE from triplicate tests. For panels A to C and F to I, the P values were assessed by Student's t test. *, P < 0.05 versus U937 cells. ***, P < 0.001 versus the untreated control. MW, molecular mass; n.s., not significant; con, control.

COMMD1 expression was induced by latent HIV-1 infection in myeloid cells but not in lymphoid cells.

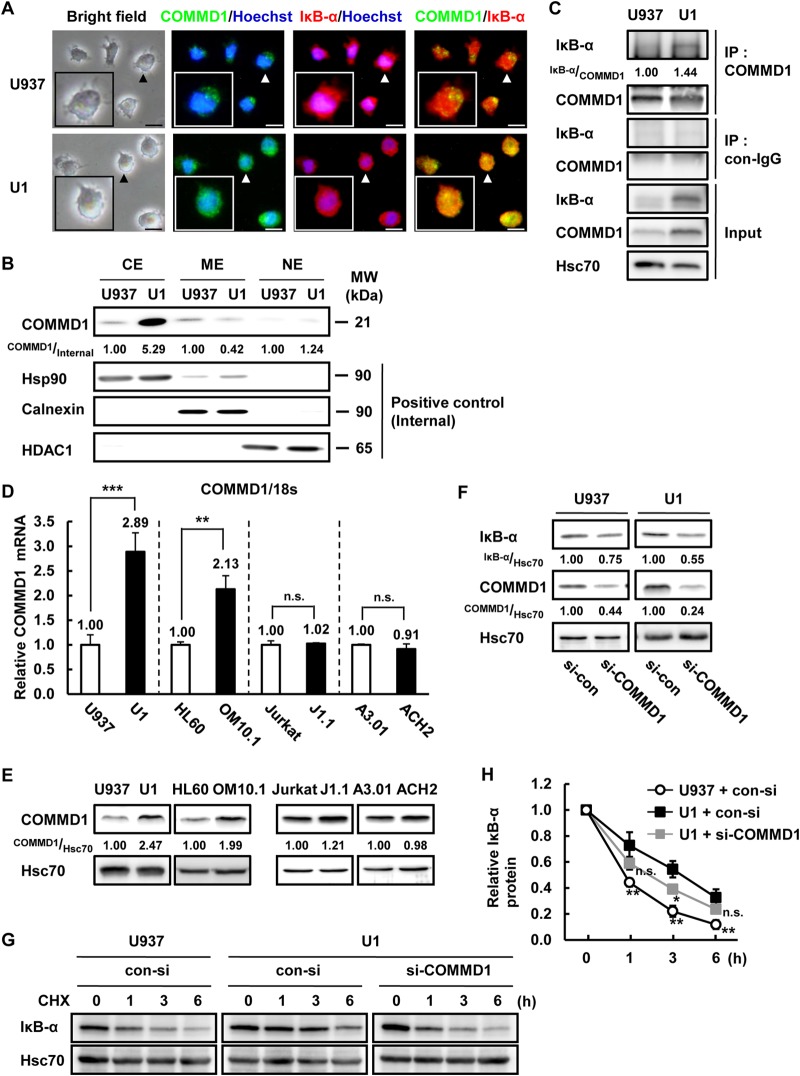

A previous report indicated that COMMD1 directly binds to IκB-α and suppresses the proteasomal degradation of IκB-α (34). COMMD1 was previously identified as an HIV-1 restriction factor that suppresses HIV-1 replication by inhibiting NF-κB activity. In this study, we focused on COMMD1 as a modulator of IκB-α stability in latently HIV-1-infected cells. First, we analyzed the localization of COMMD1 and IκB-α in U937 and U1 cells. Interestingly, photomicrographs and fractionation of cells showed that COMMD1 expression was higher and localized more extensively in the cytosolic region of U1 cells than in U937 cells (Fig. 6A [arrowheads] and B). Next, we examined the interaction between COMMD1 and IκB-α in both U937 and U1 cells. The interaction between COMMD1 and IκB-α was stronger in U1 cells than in U937 cells, which could be explained by higher quantities of both proteins in the cytosol (Fig. 6B and C). COMMD1 mRNA and protein expression was induced in latently HIV-1-infected myeloid cells but not in lymphoid cells (Fig. 6D and E), consistent with IκB-α protein expression (Fig. 1B). To check the effect of COMMD1 induction on IκB-α stabilization, we knocked down COMMD1 expression by using siRNA. COMMD1 siRNA suppressed the basal expression of IκB-α protein in U1 and U937 cells (Fig. 6F) and decreased the IκB-α protein stability in U1 cells (Fig. 6G and H). Although the IκB-α protein whose stability was rescued by si-COMMD1 in U1 cells is statistically significantly different from that in control siRNA-transfected U1 cells, it was not at the same level as in U937 cells, which is due to incomplete knockdown of COMMD1 by siRNA (Fig. 6F and H). These results indicated that the induction of COMMD1 transcription increases the expression of IκB-α via inhibition of IκB-α protein degradation in U1 cells.

FIG 6.

COMMD1 induction was correlated with IκB-α stabilization in latently HIV-1-infected cells. (A) U937 and U1 cells were fixed, permeabilized, and immunostained with anti-COMMD1 and anti-IκB-α antibodies and visualized with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated and Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated secondary antibodies, respectively. Cellular nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342. Green fluorescence is COMMD1, red fluorescence is IκB-α, and blue fluorescence is the nucleus. The overlap of COMMD1 and IκB-α is indicated by yellow fluorescence (merged images). Photomicrographs show representative cells (arrowheads). Scale bars, 10 μm. (B) COMMD1, Hsp90, calnexin, and HDAC1 protein expression was assessed in each cellular fraction of U937 and U1 cells. Hsp90 was used as a positive control for cytosol extract (CE), calnexin was used for membrane extract (ME), and HDAC1 was used for nuclear extract (NE). (C) IκB-α and p65 interaction in U937 and U1 cells was examined by immunoprecipitation. (D) COMMD1 mRNA expression in latently HIV-1-infected cells (U1, OM10.1, J1.1, ACH2) and each parental cell line (U937, HL60, Jurkat, A3.01) was examined by qPCR. P values were assessed by Student's t test. ** and ***, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively, versus each parental cell line. n.s., not significant. (E) COMMD1 and Hsc70 protein expression was examined by Western blotting. (F) IκB-α, COMMD1, and Hsc70 protein expression in U937 and U1 cells transfected with 1 mM si-COMMD1 for 48 h was analyzed by Western blotting. Band intensity was quantified with Image Gauge software, and the relative ratios of the proteins indicated are shown in panels B, C, E, and F. (G) U937 and U1 cells were transfected with si-COMMD1 and treated with CHX for 0, 1, 3, or 6 h. IκB-α and Hsc70 protein expression was examined by Western blotting. (H) Quantification of IκB-α expression in immunoblot assays (G). Data are mean values ± SE from three independent experiments. The P values were assessed by Student's t test. * and **, P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, versus si-con-transfected U1 cells. n.s., not significant; MW, molecular mass; IP, immunoprecipitate; con, control.

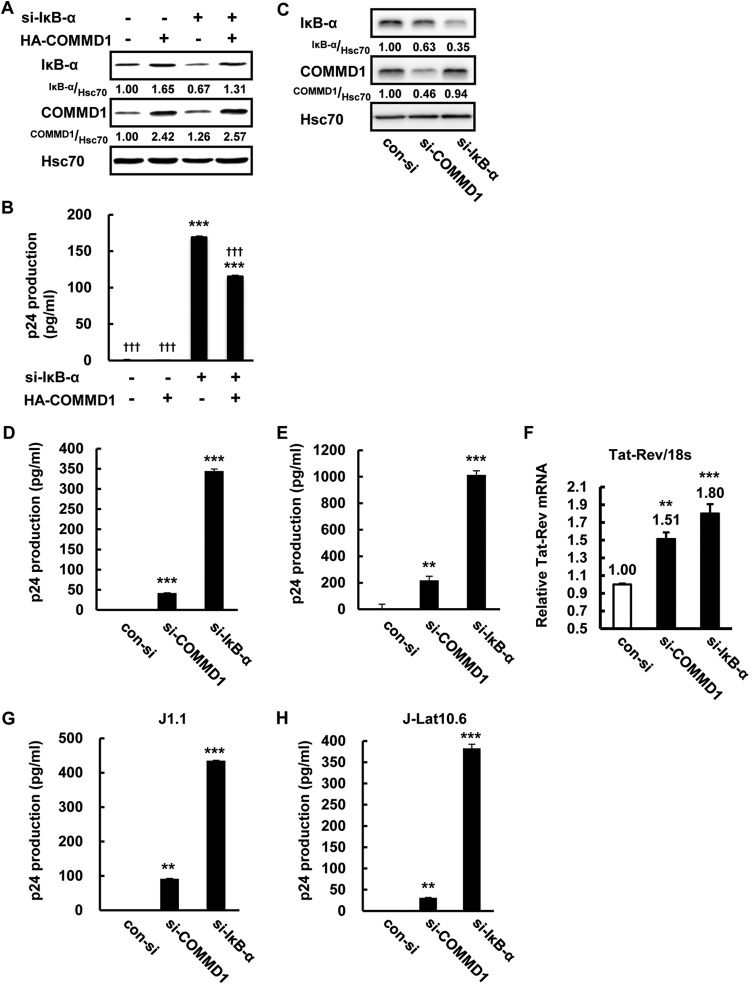

COMMD1 induction reinforces HIV-1 latency in U1 cells.

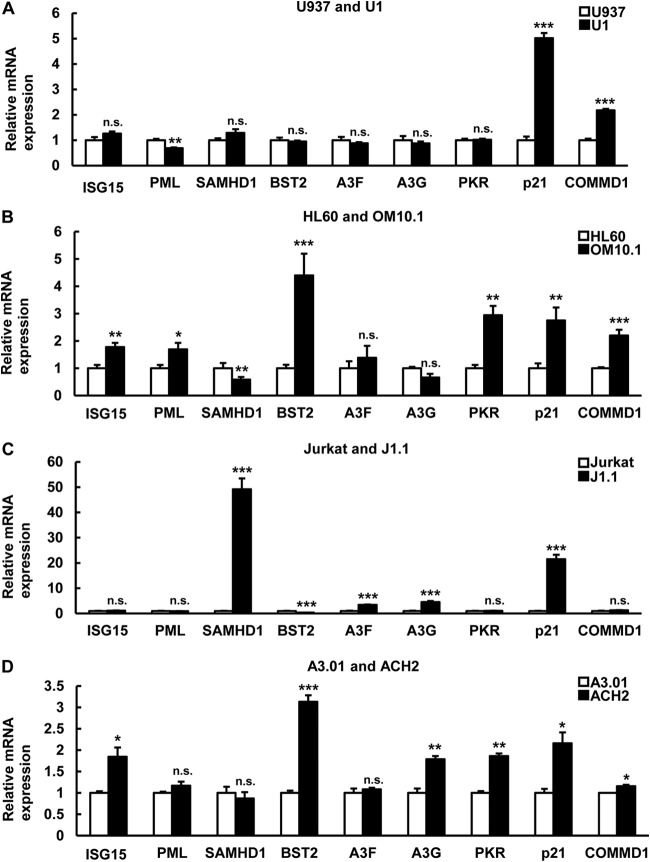

Previously, it was shown that inhibition of IκB-α reactivates HIV-1 in latently HIV-1-infected U1 and J-Lat cells (21). Because COMMD1 induction in U1 cells correlated with IκB-α expression (Fig. 6), HIV-1 reactivation might be affected by COMMD1 induction in latent HIV-1 infection. First, we checked the effect of COMMD1 on NF-κB-dependent HIV-1 reactivation. si-IκB-α decreased IκB-α protein and COMMD1 overexpression inhibited si-IκB-α-induced IκB-α suppression in U1 cells (Fig. 7A). COMMD1 overexpression decreased IκB-α knockdown-induced HIV-1 reactivation (Fig. 7B), the effect of which was partially similar to the effect on IκB-α stability (Fig. 6G). Consistent with the IκB-α stabilization by COMMD1 (Fig. 7C), COMMD1 knockdown induced HIV-1 particle release (Fig. 7D), HIV-1 protein synthesis (Fig. 7E), and HIV-1 transcription (Fig. 7F) in U1 cells, but its effect was moderate compared with that of IκB-α knockdown. We also examined the effect of COMMD1 knockdown in J1.1 and J-Lat10.6 lymphoid cells. Interestingly, COMMD1 knockdown reactivated HIV-1 in J1.1 and J-Lat10.6 cells (Fig. 7G and H). These results indicated that COMMD1 reinforces HIV-1 latency in latently HIV-1-infected cells. Because COMMD1 was reported as one of the host-derived factors (34) whose expression was induced in latently HIV-1-infected cells in this study (Fig. 6D and E), we examined the expression of mRNAs for other HIV-1 host factors. Induction of COMMD1 and p21 mRNAs was statistically significant in U1 cells (Fig. 8A). Other host factors (ISG15, PML, SAMHD1, BST2, Apopbec3F, PKR) were cell type dependently induced in latently HIV-1-infected cells, which might suggest the possibility of HIV-1-associated host factors as factors that reinforce HIV-1 latency (Fig. 8A to D).

FIG 7.

COMMD1 induction reinforces HIV-1 latency in U1 cells. Latently HIV-1-infected cells were transfected by electroporation. After 24 h, cells were recovered and analyzed for Tat-Rev mRNA expression. After 48 h, medium and cytosol were recovered and analyzed by Western blotting for protein expression and by ELISA for extracellular and intracellular HIV-1. (A, B) IκB-α, COMMD1, and Hsc70 protein expression (A) and p24 antigen production in culture medium (B) of U1 cells untransfected or transfected with si-con, si-IκB-α, pcDNA3.1, or HA-COMMD1 were measured by Western blotting and ELISA. (C) IκB-α, COMMD1, and Hsc70 protein expression in U1 cells transfected with si-con, si-IκB-α, or si-COMMD1. Band intensity was quantified with Image Gauge software, and the relative ratios of the proteins indicated are shown in panels A and C. (D, E) p24 antigen production in the culture medium (D) and cytosol (E) of U1 cells transfected with si-con, si-COMMD1, or si-IκB-α was measured by ELISA. The p24 value of each sample was calculated by subtracting the si-con value from each sample value. (F) Tat-Rev mRNA expression of the same samples as in panels C, D, and E was analyzed by qPCR. (G, H) J1.1 (G) and J-Lat10.6 (H) cells were transfected with si-con, si-COMMD1, and si-IκB-α. After 48 h, culture medium was collected and p24 antigen production was analyzed by ELISA. For panels B and D to H, the P values were assessed by ANOVA with the Tukey-Kramer test. ** and ***, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively, versus si-con- and pcDNA3.1-transfected U1 cells. †††, P < 0.001 versus pcDNA3.1- and si-IκB-α-transfected U1 cells. n.s., not significant.

FIG 8.

Host factor mRNA expression profiles in latently HIV-1-infected cells and each parental cell line. (A to D) The expression levels of the mRNAs for the genes indicated in latently HIV-1-infected cells (U1, OM10.1, J1.1, ACH2) and each parental cell (U937, HL60, Jurkat, A3.01) were compared. The P values were assessed by Student's t test. *, **, and ***, P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001, respectively, versus each parental cell line. n.s., not significant.

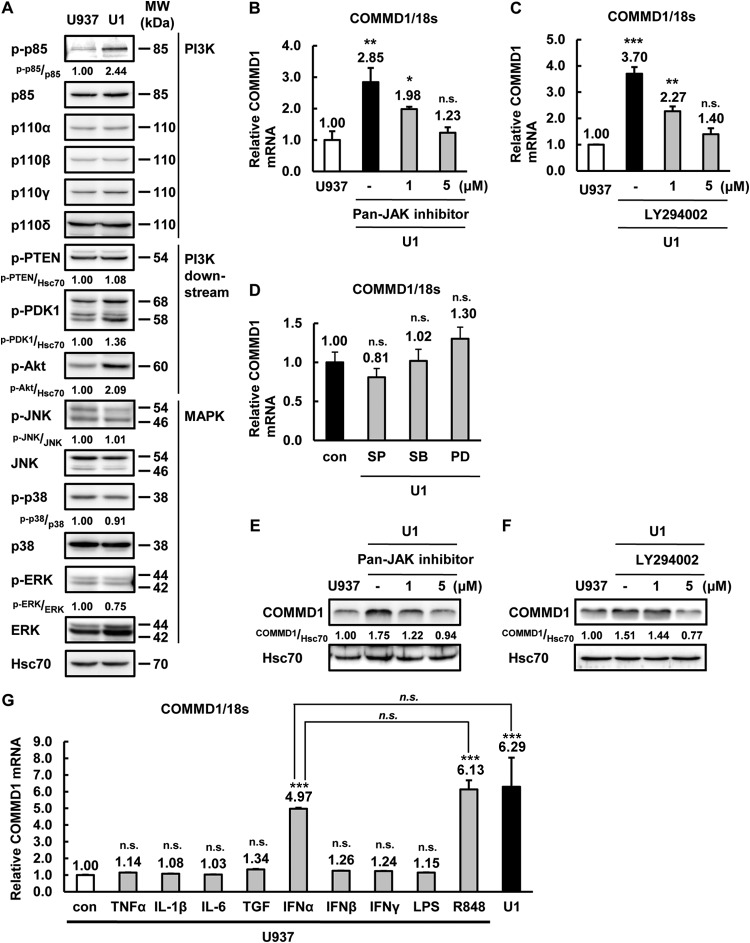

JAK-PI3K signaling regulates COMMD1 induction in latently HIV-1-infected U1 cells.

Although COMMD1 expression was induced in latently HIV-1-infected U1 and OM10.1 myeloid cells (Fig. 6D and E), the regulation of COMMD1 expression has not been examined yet. To clarify the mechanism of COMMD1 induction by latent HIV-1 infection, we compared the PI3K, PI3K-downstream, and MAPK molecules in U937 and U1 cells. The signaling molecule profile obtained by Western blotting indicated that phosphorylated p85 (PI3K) and Akt expression was induced in U1 cells at a steady-state level (Fig. 9A). PI3K and JAK inhibitors clearly suppressed COMMD1 mRNA and protein expression in U1 cells (Fig. 9B, C, E, and F), but MAPK inhibitors had no effect (Fig. 9D). Next, to determine the receptor-related signaling for the activation of COMMD1 expression, we analyzed the effect of cytokine treatment on U937 cells. IFN-α and R848 increased the expression of COMMD1 in U937 cells (Fig. 9G). Because R848 is a strong inducer of type I IFN (47), IFN-α and its downstream signaling molecules, including JAK and PI3K, could be correlated with COMMD1 induction by latent HIV-1 infection. These results indicated that JAK- and PI3K-associated signaling affects COMMD1 induction in U1 cells and the gene for COMMD1 could be a novel IFN-stimulated gene, similar to those for most previously reported HIV-1 host factors (48).

FIG 9.

The JAK-PI3K pathway is involved in COMMD1 induction in latently HIV-1-infected myeloid cells. (A) The expression of the proteins indicated in U937 and U1 cells was examined by Western blotting. (B, C) COMMD1 mRNA expression in U937 and U1 cells treated for 24 h with 0, 1, or 5 μM JAK inhibitor (B) or LY294002 (C). (D) COMMD1 mRNA expression in U1 cells left untreated or treated with 50 μM SP600125 (JNK inhibitor), SB203580 (p38 inhibitor), or PD98059 (ERK inhibitor) for 24 h. (E, F) COMMD1 and Hsc70 protein expression in U937 and U1 cells treated for 48 h with 0, 1, or 5 μM JAK inhibitor (E) or LY294002 (F). (G) COMMD1 mRNA expression in U937 cells treated for 24 h with 10 ng/ml of the indicated reagents and untreated U1 cells. Band intensity was quantified with Image Gauge software, and the relative ratios of the proteins indicated are shown in panels A, E, and F. For panels B, C, D, and G, the P values were assessed by Student's t test. ** and ***, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively, versus untreated U937 cells. n.s., no significant difference from untreated U1 cells; con, control; MW, molecular mass.

DISCUSSION

NF-κB is a crucial regulator of HIV-1 gene expression in latently HIV-1-infected cells, as confirmed by several previous reports (9, 21, 22, 49). NF-κB activity affects susceptibility to latent HIV-1 infection establishment after primary infection, and it also affects the maintenance of latent HIV-1 infection (9). p50 homodimer formation and its dominant negative effects on NF-κB p65, such as a competitive effect and a gene-silencing effect via HDAC1 recruitment, were also identified in latently HIV-1-infected cells for HIV-1 gene suppression (22). Additionally, the knockdown of IκB-α, the negative regulator of NF-κB, induced HIV-1 reactivation in latently infected cells (21). Recently, NF-κB activity was also reported as the determinant of silent infection, a novel model of latent HIV-1 infection (49). However, a comparative analysis of NF-κB and IκB-α in latently HIV-1-infected cells and noninfected cells has not been performed, although the importance of NF-κB has been well elucidated. In this study, we first identified that IκB-α protein is stabilized in latently HIV-1-infected myeloid cells, which contributes to the reinforcement of HIV-1 latency. Additionally, we clarified that host-derived factor COMMD1 induction is the molecular mechanism of IκB-α stabilization in HIV-1 latency. Considering the therapy of latent HIV-1 infection that uses cART together with reactivation of HIV-1 in the “kick-and-kill” strategy (4), our findings support the approach of NF-κB and IκB-α targeting as effective and optimal for reactivation of HIV-1. Moreover, IκB-α expression in latently infected cells is higher than that in noninfected cells (Fig. 1A).

COMMD1 was first reported as a host-derived HIV-1 restriction factor (34). In a previous study, higher expression of COMMD1 in resting CD4 T cells induced resistance to productive HIV-1 infection, in contrast to that in mature CD4 T cells. Since that first study of COMMD1 in HIV-1 infection, there has been no research showing the effect of COMMD1 on HIV-1 infection, and further verification of the function of COMMD1 in the host anti-HIV-1 defense is thought to be required, as reviewed in reference 50. Interestingly, we show here that higher expression of COMMD1 enhances HIV-1 latency in latent HIV-1 infection and COMMD1 overexpression also suppressed NF-κB-induced HIV-1 replication (Fig. 6 and 7). Therefore, COMMD1 actually suppressed HIV-1 replication not only in primary infection but also in latent infection via IκB-α stabilization and NF-κB inhibition in a molecular mechanism similar to that previously shown in a HIV-1 primary-infection study (34). Taken together, these studies suggest that COMMD1 has both beneficial and detrimental effects on the host anti-HIV-1 defense in the context of HIV-1 eradication. It is also possible that host factors other than COMMD1 have dual effects on the host anti-HIV-1 defense. This is hinted at by the observation that several HIV-1 host factors were induced in latently HIV-1-infected cells (Fig. 8). Although latent HIV-1 infection affected the expression of several host factors in four sets of latently HIV-1-infected cells and the respective parental cells, most of these effects were dependent on the cell type. Interestingly, p21 was induced in all latently HIV-1-infected cell lines and was previously reported as an HIV-1 restriction factor in hematopoietic stem cells and macrophages (51, 52). Therefore, on the basis of this concept, reevaluation of host factors by knockdown screening might clarify the effect of host factors on HIV-1 latency and improve our understanding of the roles of HIV-1 host factors. However, it is difficult to identify the host factor-encoding gene crucial for the enforcement of HIV-1 latency because of the background of the immortalized cell lines used. Additionally, latently HIV-1-infected cell lines such as those used in this study have mutations in the gene for Tat, and its RNA target has been shown to be responsible for the latency phenotype of proviruses harbored by these cell lines, limiting their significance in reflecting HIV-1 latency, as reviewed in reference 53. To elucidate the specific and bona fide HIV-1 restriction host factor that contributes to the maintenance of HIV-1 latency, analysis of latently HIV-1-infected primary cells and HIV/AIDS patients is required.

COMMD1 induction in latently HIV-1-infected myeloid cells reinforced HIV-1 latency, which was dependent on JAK/PI3K activation by latent infection (Fig. 6D and E and 7), and especially basal expression of COMMD1 in lymphoid cells also contributed to the maintenance of latency (Fig. 7G and H). However, we could not clarify the molecular details of COMMD1 gene regulation in these cell types. COMMD1 regulation might be different in myeloid and lymphoid cells, because we found that COMMD1 protein and mRNA expression is higher in lymphoid cells than in myeloid cells (unpublished data). A previous report indicated that COMMD1 expression is higher in CD4 T cells than in CD8 T cells (34). Therefore, COMMD1 expression is quite different among cell types and might be regulated in a lineage-specific manner. On the basis of our in silico analysis, there are several transcription factor binding sites (STAT, AP-1, NF-κB, NFAT) in the COMMD1 promoter region that could be downstream of JAK/PI3K (data not shown). PTEN, an endogenous inhibitor of PI3K, is mutated in the lymphoid (Jurkat, ACH2, J1.1, A3.01) cells that were used in this study (54). Therefore, lymphoid cell lines may not reflect the in vivo situation since PTEN is functionally defective in these lymphoid cell lines and the PTEN/JAK/PI3K pathway might be critical for expression of the gene for COMMD1 in the latent HIV-1 infection of not only myeloid cells but also lymphoid cells. A recent report indicated that the histone acetyltransferase p300 acetylates the COMMD1 protein and regulates its stability (55). On the basis of that report, we examined COMMD1 protein stability in U937 and U1 cells. COMMD1 protein stability was slightly greater in U1 cells than in U937 cells (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). p300 expression was barely decreased in U1 cells (see Fig. S2B). Considering that COMMD1 induction at the mRNA level was more robust than at the protein level, the upregulation of COMMD1 by latent HIV-1 infection might be dependent on COMMD1 mRNA induction rather than p300-dependent COMMD1 protein stabilization. COMMD1 directly binds the p65 protein and regulates its localization and stability upon treatment with TNF-α (31) and aspirin (33). In this study, we examined p65 protein degradation in steady-state and TNF-α-stimulated U937 and U1 cells. Although nuclear p65 expression was not detected at steady state (data not shown), p65 degradation by TNF-α treatment was not accelerated in U1 cells, despite the higher expression of COMMD1 (see Fig. S2C). Because COMMD1 expression in the nucleus was similar in U937 and U1 cells, in contrast to that in the cytosol (Fig. 6B) and TNF-α affects HIV-1 reactivation under this condition, COMMD1-dependent p65 degradation might not be a major factor in the present study. Consistent with our results, Ganesh et al. indicated that COMMD1 knockdown does not affect p65 in HEK293 cells under steady-state conditions (34). Therefore, NF-κB signal regulation by COMMD1 could occur through IκB-α regulation, at least in steady-state cells. COMMD1 has multiple functions, such as in ion metabolism, apoptosis, and transcription, via binding to various proteins, such as ATP7A/B, ENaC, CFTR, XIAP, NF-κB, and HIF-1 (56, 57). Therefore, these proteins might be related to the pathological output of HIV/AIDS. In fact, the levels of several ions in HIV/AIDS patients' peripheral blood are different from those of healthy subjects, as previously reported (58). XIAP is induced, which inhibits apoptosis, in latently HIV-1-infected cells (59). Further analysis of COMMD1 and proteins related to it is still required to show the importance of COMMD1 in HIV-1 latency.

Because latently HIV-1-infected cell lines were previously established by chronic HIV-1 infection of leukemic cell lines, the background of all latently HIV-1-infected cells was cancer cells, as mentioned above. Considering the physiological relevance and bona fide mechanism of HIV-1 latency, it is necessary to assess latent HIV-1 infection in primary cells or HIV/AIDS patient-derived cells. Myeloid cell types especially are thought to be a minor latent-HIV-1 reservoir population compared to CD4 T lymphoid cells, which are considered a major population. Although clinical studies have indicated the existence of HIV-1 latency in myeloid cells and ex vivo analysis also indicated the potential of myeloid cells as a latent-HIV-1 reservoir, the establishment of an optimal model of HIV-1 latency reflecting HIV/AIDS patients is required (60–62). Recently, a latent HIV-1 infection model was established by using isolated CD4 T cells from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (63, 64). However, there is no report of a model for the analysis of latent HIV-1 infection in primary myeloid cells. As a latent-HIV-1 reservoir, the myeloid cell population is thought to be quite small compared with CD4 T cells. That could make it difficult to analyze latently HIV-1-infected myeloid cells in HIV/AIDS patients. Therefore, to establish a latently HIV-1-infected primary myeloid cell model, we plan to use the double-labeled HIV-1 that encodes LTR-dependent and independent fluorescent proteins recently established by two groups (63, 64). This approach might resolve the lack of a primary model in the HIV-1 latency field of study.

HIV-1 latency is a crucial problem for the complete cure of HIV/AIDS. To overcome this problem, examination of the molecular mechanisms of HIV-1 latency is essential. In the present study, we first found that COMMD1, which was previously identified as an HIV-1 restriction factor in primary infection (34), reinforces HIV-1 latency in myeloid cells. Although further verification is required, we show here that HIV-1 host factors might have dual functions in the host anti-HIV-1 defense in the context of HIV-1 eradication in both primary and latent infections.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Science Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture (MEXT) of Japan (23107725 to S.O. and 248328 to M.T.); by the Global COE Programs (Research Center Aiming at the Control of AIDS) from MEXT; by a Health and Labor Sciences Research Grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan (H25-AIDS-I-002 to S.O.); by a Japan Foundation for AIDS Prevention fellowship (to M.T.); by a Japan Society for Promotion of Science fellowship (to M.T. and E.K.); and by a research grant from The Research Foundation for Pharmaceutical Sciences, The KANAE Foundation for the Promotion of Medical Science, and The SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation (to M.T.).

The following reagents were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: A3.01, ACH2, J1.1, and U1 from Thomas Folks; OM10.1 from Salvatore Butera; and full-length clone J-Lat10.6 from Eric Verdin.

We thank Y. Endo for secretarial assistance and I. Suzu and S. Fujikawa for research assistance.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.03105-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arts EJ, Hazuda DJ. 2012. HIV-1 antiretroviral drug therapy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2(4):a007161. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruelas DS, Greene WC. 2013. An integrated overview of HIV-1 latency. Cell 155:519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finzi D, Blankson J, Siliciano JD, Margolick JB, Chadwick K, Pierson T, Smith K, Lisziewicz J, Lori F, Flexner C, Quinn TC, Chaisson RE, Rosenberg E, Walker B, Gange S, Gallant J, Siliciano RF. 1999. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat Med 5:512–517. doi: 10.1038/8394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richman DD, Margolis DM, Delaney M, Greene WC, Hazuda D, Pomerantz RJ. 2009. The challenge of finding a cure for HIV infection. Science 323:1304–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1165706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman CM, Wu L. 2009. HIV interactions with monocytes and dendritic cells: viral latency and reservoirs. Retrovirology 6:51. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emiliani S, Van Lint C, Fischle W, Paras P Jr, Ott M, Brady J, Verdin E. 1996. A point mutation in the HIV-1 Tat responsive element is associated with postintegration latency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:6377–6381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emiliani S, Fischle W, Ott M, Van Lint C, Amella CA, Verdin E. 1998. Mutations in the tat gene are responsible for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 postintegration latency in the U1 cell line. J Virol 72:1666–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yukl S, Pillai S, Li P, Chang K, Pasutti W, Ahlgren C, Havlir D, Strain M, Gunthard H, Richman D, Rice AP, Daar E, Little S, Wong JK. 2009. Latently-infected CD4+ T cells are enriched for HIV-1 Tat variants with impaired transactivation activity. Virology 387:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duverger A, Jones J, May J, Bibollet-Ruche F, Wagner FA, Cron RQ, Kutsch O. 2009. Determinants of the establishment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 latency. J Virol 83:3078–3093. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02058-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnett JC, Lim KI, Calafi A, Rossi JJ, Schaffer DV, Arkin AP. 2010. Combinatorial latency reactivation for HIV-1 subtypes and variants. J Virol 84:5958–5974. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00161-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gringhuis SI, van der Vlist M, van den Berg LM, den Dunnen J, Litjens M, Geijtenbeek TB. 2010. HIV-1 exploits innate signaling by TLR8 and DC-SIGN for productive infection of dendritic cells. Nat Immunol 11:419–426. doi: 10.1038/ni.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheidereit C. 2006. IkappaB kinase complexes: gateways to NF-kappaB activation and transcription. Oncogene 25:6685–6705. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh S, Hayden MS. 2008. New regulators of NF-kappaB in inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 8:837–848. doi: 10.1038/nri2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaron A, Hatzubai A, Davis M, Lavon I, Amit S, Manning AM, Andersen JS, Mann M, Mercurio F, Ben-Neriah Y. 1998. Identification of the receptor component of the IkappaBalpha-ubiquitin ligase. Nature 396:590–594. doi: 10.1038/25159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu LJ, Liu TT, Ran Y, Li Y, Zhang XD, Shu HB, Wang YY. 2012. The E3 ubiquitin ligase MIB1 negatively regulates basal IkappaBalpha level and modulates NF-kappaB activation. Cell Res 22:603–606. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. 2006. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bagasra O, Wright SD, Seshamma T, Oakes JW, Pomerantz RJ. 1992. CD14 is involved in control of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 expression in latently infected cells by lipopolysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89:6285–6289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novis CL, Archin NM, Buzon MJ, Verdin E, Round JL, Lichterfeld M, Margolis DM, Planelles V, Bosque A. 2013. Reactivation of latent HIV-1 in central memory CD4(+) T cells through TLR-1/2 stimulation. Retrovirology 10:119. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thibault S, Imbeault M, Tardif MR, Tremblay MJ. 2009. TLR5 stimulation is sufficient to trigger reactivation of latent HIV-1 provirus in T lymphoid cells and activate virus gene expression in central memory CD4+ T cells. Virology 389:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlaepfer E, Audige A, Joller H, Speck RF. 2006. TLR7/8 triggering exerts opposing effects in acute versus latent HIV infection. J Immunol 176:2888–2895. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez G, Zaikos TD, Khan SZ, Jacobi AM, Behlke MA, Zeichner SL. 2013. Targeting IkappaB proteins for HIV latency activation: the role of individual IκB and NF-κB proteins. J Virol 87:3966–3978. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03251-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams SA, Chen LF, Kwon H, Ruiz-Jarabo CM, Verdin E, Greene WC. 2006. NF-kappaB p50 promotes HIV latency through HDAC recruitment and repression of transcriptional initiation. EMBO J 25:139–149. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Bie P, van de Sluis B, Klomp L, Wijmenga C. 2005. The many faces of the copper metabolism protein MURR1/COMMD1. J Hered 96:803–811. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esi110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ke Y, Butt AG, Swart M, Liu YF, McDonald FJ. 2010. COMMD1 downregulates the epithelial sodium channel through Nedd4-2. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298:F1445–1456. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00257.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang T, Ke Y, Ly K, McDonald FJ. 2011. COMMD1 regulates the delta epithelial sodium channel (deltaENaC) through trafficking and ubiquitination. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 411:506–511. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drévillon L, Tanguy G, Hinzpeter A, Arous N, de Becdelievre A, Aissat A, Tarze A, Goossens M, Fanen P. 2011. COMMD1-mediated ubiquitination regulates CFTR trafficking. PLoS One 6:e18334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tao TY, Liu F, Klomp L, Wijmenga C, Gitlin JD. 2003. The copper toxicosis gene product Murr1 directly interacts with the Wilson disease protein. J Biol Chem 278:41593–41596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Bie P, van de Sluis B, Burstein E, van de Berghe PV, Muller P, Berger R, Gitlin JD, Wijmenga C, Klomp LW. 2007. Distinct Wilson's disease mutations in ATP7B are associated with enhanced binding to COMMD1 and reduced stability of ATP7B. Gastroenterology 133:1316–1326. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vonk WI, Wijmenga C, Berger R, van de Sluis B, Klomp LW. 2010. Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase maturation and activity are regulated by COMMD1. J Biol Chem 285:28991–29000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.101477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maine GN, Burstein E. 2007. COMMD proteins and the control of the NF kappa B pathway. Cell Cycle 6:672–676. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.6.3989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maine GN, Mao X, Komarck CM, Burstein E. 2007. COMMD1 promotes the ubiquitination of NF-kappaB subunits through a cullin-containing ubiquitin ligase. EMBO J 26:436–447. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geng H, Wittwer T, Dittrich-Breiholz O, Kracht M, Schmitz ML. 2009. Phosphorylation of NF-kappaB p65 at Ser468 controls its COMMD1-dependent ubiquitination and target gene-specific proteasomal elimination. EMBO Rep 10:381–386. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thoms HC, Loveridge CJ, Simpson J, Clipson A, Reinhardt K, Dunlop MG, Stark LA. 2010. Nucleolar targeting of RelA(p65) is regulated by COMMD1-dependent ubiquitination. Cancer Res 70:139–149. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganesh L, Burstein E, Guha-Niyogi A, Louder MK, Mascola JR, Klomp LW, Wijmenga C, Duckett CS, Nabel GJ. 2003. The gene product Murr1 restricts HIV-1 replication in resting CD4+ lymphocytes. Nature 426:853–857. doi: 10.1038/nature02171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greene WC. 2004. How resting T cells deMURR HIV infection. Nat Immunol 5:18–19. doi: 10.1038/ni0104-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdel-Mohsen M, Raposo RAS, Deng XT, Li MQ, Liegler T, Sinclair E, Salama MS, Ghanem HEDA, Hoh R, Wong JK, David M, Nixon DF, Deeks SG, Pillai SK. 2013. Expression profile of host restriction factors in HIV-1 elite controllers. Retrovirology 10:106. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kudo E, Taura M, Matsuda K, Shimamoto M, Kariya R, Goto H, Hattori S, Kimura S, Okada S. 2013. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by a tricyclic coumarin GUT-70 in acutely and chronically infected cells. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 23:606–609. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taura M, Kariya R, Kudo E, Goto H, Iwawaki T, Amano M, Suico MA, Kai H, Mitsuya H, Okada S. 2013. Comparative analysis of ER stress response into HIV protease inhibitors: lopinavir but not darunavir induces potent ER stress response via ROS/JNK pathway. Free Radic Biol Med 65:778–788. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.08.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taura M, Suico MA, Koyama K, Komatsu K, Miyakita R, Matsumoto C, Kudo E, Kariya R, Goto H, Kitajima S, Takahashi C, Shuto T, Nakao M, Okada S, Kai H. 2012. Rb/E2F1 regulates the innate immune receptor Toll-like receptor 3 in epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol 32:1581–1590. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06454-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furusawa Y, Fujiwara Y, Campbell P, Zhao QL, Ogawa R, Hassan MA, Tabuchi Y, Takasaki I, Takahashi A, Kondo T. 2012. DNA double-strand breaks induced by cavitational mechanical effects of ultrasound in cancer cell lines. PLoS One 7:e29012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown K, Park S, Kanno T, Franzoso G, Siebenlist U. 1993. Mutual regulation of the transcriptional activator NF-kappa B and its inhibitor, I kappa B-alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:2532–2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tachado SD, Li X, Swan K, Patel N, Koziel H. 2008. Constitutive activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathway down-regulates TLR4-mediated tumor necrosis factor-alpha release in alveolar macrophages from asymptomatic HIV-positive persons in vitro. J Biol Chem 283:33191–33198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805067200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tachado SD, Li X, Bole M, Swan K, Anandaiah A, Patel NR, Koziel H. 2010. MyD88-dependent TLR4 signaling is selectively impaired in alveolar macrophages from asymptomatic HIV+ persons. Blood 115:3606–3615. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-250787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nowak P, Barqasho B, Treutiger CJ, Harris HE, Tracey KJ, Andersson J, Sonnerborg A. 2006. HMGB1 activates replication of latent HIV-1 in a monocytic cell-line, but inhibits HIV-1 replication in primary macrophages. Cytokine 34:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perkins ND. 2007. Integrating cell-signalling pathways with NF-kappaB and IKK function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8:49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrm2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Z, Ricker JL, Malhotra PS, Nottingham L, Bagain L, Lee TL, Yeh NT, Van Waes C. 2008. Differential bortezomib sensitivity in head and neck cancer lines corresponds to proteasome, nuclear factor-kappaB and activator protein-1 related mechanisms. Mol Cancer Ther 7:1949–1960. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jurk M, Heil F, Vollmer J, Schetter C, Krieg AM, Wagner H, Lipford G, Bauer S. 2002. Human TLR7 or TLR8 independently confer [sic] responsiveness to the antiviral compound R-848. Nat Immunol 3:499. doi: 10.1038/ni0602-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pillai SK, Abdel-Mohsen M, Guatelli J, Skasko M, Monto A, Fujimoto K, Yukl S, Greene WC, Kovari H, Rauch A, Fellay J, Battegay M, Hirschel B, Witteck A, Bernasconi E, Ledergerber B, Gunthard HF, Wong JK, Swiss HIV Cohort Study . 2012. Role of retroviral restriction factors in the interferon-alpha-mediated suppression of HIV-1 in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:3035–3040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111573109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dahabieh MS, Ooms M, Brumme C, Taylor J, Harrigan PR, Simon V, Sadowski I. 2014. Direct non-productive HIV-1 infection in a T-cell line is driven by cellular activation state and NFkappaB. Retrovirology 11:17. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-11-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zack JA, Kim SG, Vatakis DN. 2013. HIV restriction in quiescent CD4(+) T cells. Retrovirology 10:37. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allouch A, David A, Amie SM, Lahouassa H, Chartier L, Margottin-Goguet F, Barre-Sinoussi F, Kim B, Saez-Cirion A, Pancino G. 2013. p21-mediated RNR2 repression restricts HIV-1 replication in macrophages by inhibiting dNTP biosynthesis pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:E3997–E4006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306719110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang J, Scadden DT, Crumpacker CS. 2007. Primitive hematopoietic cells resist HIV-1 infection via p21. J Clin Invest 117:473–481. doi: 10.1172/JCI28971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Han Y, Wind-Rotolo M, Yang HC, Siliciano JD, Siliciano RF. 2007. Experimental approaches to the study of HIV-1 latency. Nat Rev Microbiol 5:95–106. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doyon G, Zerbato J, Mellors JW, Sluis-Cremer N. 2013. Disulfiram reactivates latent HIV-1 expression through depletion of the phosphatase and tensin homolog. AIDS 27:F7–F11. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283570620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O'Hara A, Simpson J, Morin P, Loveridge CJ, Williams AC, Novo S, Stark LA. 2014. p300-mediated acetylation of COMMD1 regulates its stability, and the ubiquitination and nucleolar translocation of the RelA NF-κB subunit. J Cell Sci 127(Pt 17):3659–3665. doi: 10.1242/jcs.149328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mufti AR, Burstein E, Duckett CS. 2007. XIAP: cell death regulation meets copper homeostasis. Arch Biochem Biophys 463:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bartuzi P, Hofker MH, van de Sluis B. 2013. Tuning NF-kappaB activity: a touch of COMMD proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1832:2315–2321. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beach RS, Mantero-Atienza E, Shor-Posner G, Javier JJ, Szapocznik J, Morgan R, Sauberlich HE, Cornwell PE, Eisdorfer C, Baum MK. 1992. Specific nutrient abnormalities in asymptomatic HIV-1 infection. AIDS 6:701–708. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199207000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berro R, de la Fuente C, Klase Z, Kehn K, Parvin L, Pumfery A, Agbottah E, Vertes A, Nekhai S, Kashanchi F. 2007. Identifying the membrane proteome of HIV-1 latently infected cells. J Biol Chem 282:8207–8218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McElrath MJ, Steinman RM, Cohn ZA. 1991. Latent HIV-1 infection in enriched populations of blood monocytes and T cells from seropositive patients. J Clin Invest 87:27–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI114981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mikovits JA, Lohrey NC, Schulof R, Courtless J, Ruscetti FW. 1992. Activation of infectious virus from latent human immunodeficiency virus infection of monocytes in vivo. J Clin Invest 90:1486–1491. doi: 10.1172/JCI116016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lambotte O, Taoufik Y, de Goer MG, Wallon C, Goujard C, Delfraissy JF. 2000. Detection of infectious HIV in circulating monocytes from patients on prolonged highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 23:114–119. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200002010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dahabieh MS, Ooms M, Simon V, Sadowski I. 2013. A doubly fluorescent HIV-1 reporter shows that the majority of integrated HIV-1 is latent shortly after infection. J Virol 87:4716–4727. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03478-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Calvanese V, Chavez L, Laurent T, Ding S, Verdin E. 2013. Dual-color HIV reporters trace a population of latently infected cells and enable their purification. Virology 446:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.