ABSTRACT

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a primary etiological agent of childhood lower respiratory tract disease. Molecular patterns induced by active infection trigger a coordinated retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling response to induce inflammatory cytokines and antiviral mucosal interferons. Recently, we discovered a nuclear oxidative stress-sensitive pathway mediated by the DNA damage response protein, ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), in cytokine-induced NF-κB/RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation. Here we observe that ATM silencing results in enhanced single-strand RNA (ssRNA) replication of RSVand Sendai virus, due to decreased expression and secretion of type I and III interferons (IFNs), despite maintenance of IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3)-dependent IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs). In addition to enhanced oxidative stress, RSV replication enhances foci of phosphorylated histone 2AX variant (γH2AX), Ser 1981 phosphorylation of ATM, and IKKγ/NEMO-dependent ATM nuclear export, indicating activation of the DNA damage response. ATM-deficient cells show defective RSV-induced mitogen and stress-activated kinase 1 (MSK-1) Ser 376 phosphorylation and reduced RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation, whose formation is required for IRF7 expression. We observe that RelA inducibly binds the native IFN regulatory factor 7 (IRF7) promoter in an ATM-dependent manner, and IRF7 inducibly binds to the endogenous retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) promoter. Ectopic IRF7 expression restores RIG-I expression and type I/III IFN expression in ATM-silenced cells. We conclude that paramyxoviruses trigger the DNA damage response, a pathway required for MSK1 activation of phospho Ser 276 RelA formation to trigger the IRF7-RIG-I amplification loop necessary for mucosal IFN production. These data provide the molecular pathogenesis for defects in the cellular innate immunity of patients with homozygous ATM mutations.

IMPORTANCE RNA virus infections trigger cellular response pathways to limit spread to adjacent tissues. This “innate immune response” is mediated by germ line-encoded pattern recognition receptors that trigger activation of two, largely independent, intracellular NF-κB and IRF3 transcription factors. Downstream, expression of protective antiviral interferons is amplified by positive-feedback loops mediated by inducible interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) and retinoic acid inducible gene (RIG-I). Our results indicate that a nuclear oxidative stress- and DNA damage-sensing factor, ATM, is required to mediate a cross talk pathway between NF-κB and IRF7 through mediating phosphorylation of NF-κB. Our studies provide further information about the defects in cellular and innate immunity in patients with inherited ATM mutations.

INTRODUCTION

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a negative-sense, single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) virus of the Paramyxoviridae family, is one of the most important respiratory pathogens of young children worldwide (1). Epidemiological studies have shown that RSV infects almost all children in the United States by the age of 3, producing primarily upper respiratory tract infections and otitis media (2). In a small subset of immunologically naive or predisposed infants, RSV infection produces a more severe, lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI), an event that accounts for over 3 million hospitalizations and about 200,000 deaths (3, 4). Importantly, there are no effective vaccines or treatments available (2).

In seasonal epidemics, RSV is spread via large droplets and self-inoculation (3). Once infected, RSV replicates in the nasal mucosa intraepithelial bridges into the lower respiratory tract or by free virus in respiratory secretions binding to epithelial cilia (5, 6). In the lower airway, RSV replicates primarily in epithelial cells, where it generates bronchial inflammation, epithelial necrosis, sloughing, peribronchial mononuclear cell infiltration, and submucosal edema producing obstructive physiology (7–9). The pathogenesis of LRTI involves an interplay between viral inoculum, host factors, and immune response and is not fully understood (10). Children with bronchiolitis present symptoms at times when RSV titers are falling (11) and express increased markers of innate immune response activation (e.g., MIP-1α [12)]), indicating that an exaggerated host signaling response may play a contributory role in disease pathogenesis.

RSV replication in airway epithelial cells is a potent trigger of intracellular and endosomal pattern recognition receptors (13–16). Our work and that of others have shown that cytoplasmic viral genomic RNA is recognized initially by the cytoplasmic retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) and later by the endosomal Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) (17, 18), whose coordinated actions are required for an effective innate immune response (19–21). Upon binding to RSV or 5′ triphosphorylated RNAs, RIG-I undergoes a conformational switch via inducible K63-linked polyubiquitylation (22, 23). This process promotes conformational change of two caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD)-like domains, which then mediate downstream signaling by binding to CARD-like domains of mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS), inducing its oligomerization into prion-like signaling complexes (20, 24, 25). This signaling event primarily activates the downstream of the tank binding kinase (TBK1)/IκB kinase (IKK)ε complex, which leads to phosphorylation of the ubiquitous interferon (IFN) regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and its dimerization-coupled translocation into the nucleus.

Activated IRF3 is a major initial regulator of mucosal IFN expression (26), which mediates the antiviral response by inducing transcription of a network of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) (27–29) important in activating adaptive immunity and inhibiting viral entry or replication (30–32). Although IRF3 plays an important role as an initial trigger of the innate immune response (IIR), its actions are significantly modulated by cross talk with NF-κB signaling. For example, IFN-β is primarily an IRF3-dependent gene, activated NF-κB is required for rapid IFN-β expression by activating cooperative enhancers in the IFN-β promoter (33) and by promoting synthesis of the inducible IRF1 and IRF7 transcription factors to sustain and amplify the initial actions of IRF3 (34, 35). Our recent mathematical modeling of the integrated NF-κB-IRF3 pathway in response to double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) identified a functional role of IRF7 upregulation required for RIG-I amplification (36). Here, NF-κB-dependent activation of IRF7 was required for robust RIG-I expression and propagation of type I IFN signaling (36). Together, these data indicate that the NF-κB cross talk influences the dynamics of the IFN expression.

Previous work has shown that RSV-induced NF-κB activation consists of two, separable components: the first involving NF-κB/RelA liberation from cytoplasmic IκB inhibitors and the second involving its inducible Ser 276 phosphorylation, licensing its activation potential for induction of immediate early gene expression (37). RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation is controlled by a family of stimulus-dependent ribosomal S6 kinases (RS6Ks) (37, 38). In the case of RSV infection, RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation is mediated by the reactive oxygen species (ROS)-inducible RS6K family member MSK1 (mitogen and stress-activated kinase 1) (37). NF-κB/RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation is a rate-limiting posttranslational modification necessary for p300/CBP-dependent Lys 310 acetylation and complex formation with BRD4/CDK9 positive transcriptional elongation factor (14). As a result, RelA Ser 276 is a key posttranslational modification controlling immediate early cytokine gene expression by the process of transcriptional elongation (14). Understanding the oxidative pathways controlling inducible posttranslational modification of NF-κB/RelA is of obvious importance to the pathogenesis of RSV LRTI.

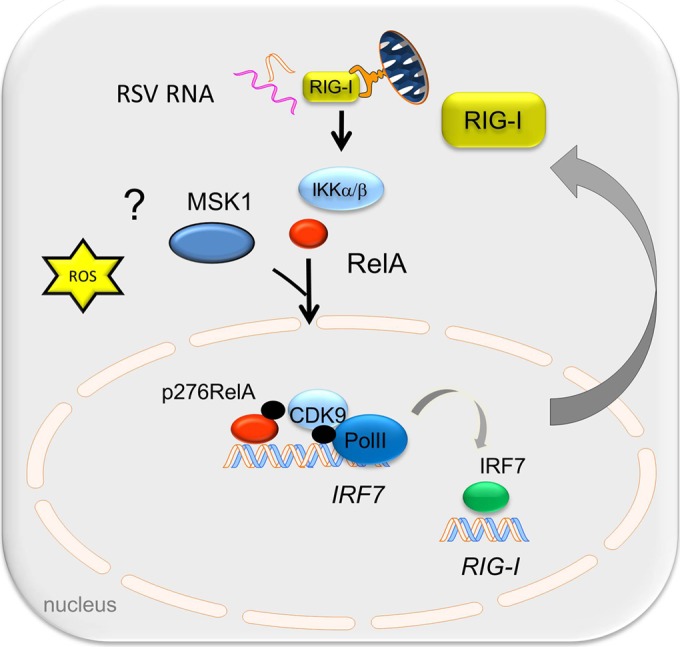

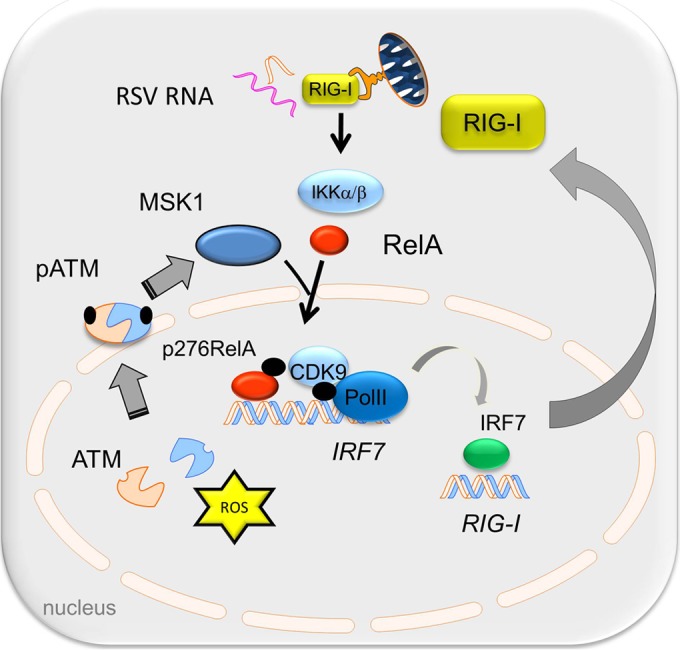

We have recently shown that intracellular ROS generated by activated tumor necrosis factor RI (TNFRI) is sensed by the nuclear phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3) kinase ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase (39). In response to TNF-induced oxidative stress, nuclear ATM is activated and translocates into the cytosol, where it forms a scaffold to engage the RS6K PKAc, promoting RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation and immediate early gene activation (39). In this study, we sought to determine whether the ATM pathway participates in the IIR activated by paramyxovirus virus replication (Fig. 1). We observed enhanced replication of RSV and SeV in airway cells depleted of ATM and in normal human airway epithelial cells treated with a selective ATM small molecule inhibitor. We observe that ATM is activated by RSV replication associated with the formation of DNA double-stranded breaks (DSBs) and transported from the nucleus into the cytosol in an IKKγ/NEMO-dependent manner. ATM is required for MSK1 activation and RelA Ser276 phosphorylation. We further demonstrate that RSV-induced IRF7 expression is RelA phospho-Ser 276 dependent and that ATM deficiency inhibits the IRF7-RIG-I gene amplification loop, decreasing IFN type I and III IFN expression. These results indicate that the ATM-phospho-Ser276 RelA-IRF7-RIG-I pathway plays an essential role in the IIR to ssRNA virus infections.

FIG 1.

Working model for the ROS-dependent formation of Ser 276-phosphorylated RelA in response to RSV infection. RSV dsRNA is sensed by RIG-I, triggering NF-κB release from cytoplasmic stores. In parallel, oxidative stress is required for RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation, mediated by the R6SK MSK1. Downstream, activated phospho-Ser 276 RelA triggers IRF7 gene expression and RIG-I upregulation. The resynthesized RIG-I sustains IFN expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and treatment.

Human A549 pulmonary epithelial cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were grown in F12K medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator (40). Primary human small airway epithelial cells (hSAECs; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were grown in small airway epithelial cell growth medium (SAGM; Lonza, Walkersville, MD). Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were grown in Eagle's minimum essential medium (Gibco) with 10% FBS with 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids and 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate (40).

Poly(I·C) was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). For poly(I·C) electroporation, A549 cells were trypsinized, washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and pelleted by centrifugation. The cell pellet was then resuspended in 100 μl Nucleofector solution (Amaxa; Lonza) with poly(I·C) into an electroporation cuvette. The cell suspension was electroporated using a Nucleofector I device (Amaxa; Lonza) with the Nucleofector Program X-001.

Virus preparation and infection.

The human RSV A2 strain was grown and prepared as stocks at 8 to 9 log PFU/ml by sucrose cushion centrifugation (41). Viral pools were aliquoted, quick-frozen on dry ice-ethanol, and stored at −80°C until they were used. The viral titer of cell-associated RSV was determined by a methylcellulose plaque assay (41). Sendai virus (SeV) was purchased from Charles River Laboratory. Cells were infected with 100 hemagglutinin units/ml (42).

shRNA-mediated ATM knockdown in A549 cells.

ATM and control short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) were gifts from Sankar Mitra (Methodist Hospital, Houston, TX). Plasmids were transfected into A549 cells using the FuGENE HD kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Five micrograms of plasmid was mixed with 15 μl of FuGENE HD transfection reagent for 5 min. Afterwards, the mixture was added to a 10-cm cell plate and mixed gently. Forty-eight hours later, cells were selected in medium containing puromycin (6 μg/ml) for 2 weeks.

Cellular extract preparation and protein quantification.

Whole-cell extracts (WCE) were prepared in radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) buffer as previously described (43). Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were fractionated as previously described (39). For Western blotting (WB), equal amounts of extracts were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The PVDF membranes were blocked in 5% milk–Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBST) buffer for 1 h and then incubated with specific primary antibody (Ab) overnight at 4°C followed by washing with TBST and incubation with secondary Ab for 1 h. Membranes were exposed by the ECL Western blotting solution (Amersham), and the films were developed by a Kodak machine or imaged with an Odyssey infrared scanner (LiCor BioSciences, Lincoln, NE). Anti-RSV and anti-γH2AX Abs were purchased from Abcam (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA); anti-SeV was purchased from MBL (MBL International Corporation, Woburn, MA); anti-β-actin and anti-RelA Abs were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); anti-pSer 1981 ATM, anti-ATM, anti-pSer 276 RelA, and anti-pSer 376 MSK1 Abs were purchased from Cell Signaling (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); anti-lamin B Ab was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). IFN-β secretion was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; PBL Biomedical Laboratories, Piscataway, NJ).

Q-RT-PCR.

For quantitative real-time PCR (Q-RT-PCR), total RNA was extracted using acid guanidium phenol extraction (Tri reagent; Sigma). For gene expression analyses, 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed using the SuperScript III first strand synthesis system (Life Technologies, Invitrogen) in a 20-μl reaction mixture (40). cDNA product (1 μl) was diluted at a ratio of 1:2; 2 μl of diluted product was amplified in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 10 μl of SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and a final concentration of 0.4 μM (each) forward and reverse gene-specific primers (Table 1). The reaction mixtures were aliquoted into a Bio-Rad 96-well clear PCR plate, and the plate was sealed with Bio-Rad Microseal B film. The plates were denatured for 90 s at 95°C and then subjected to 40 cycles of 15 s at 94°C, 60 s at 60°C, and 1 min at 72°C in an MyiQ Single Color Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). PCR products were subjected to melting curve analysis to ensure that a single amplification product was produced. Quantification of relative changes in gene expression was done using the threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) method (44).

TABLE 1.

Primer sets for Q-RT-PCR

| Primer set | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |

| RSVN | AAGGGATTTTTGCAGGATTGTTT | TCCCCACCGTAACATCACTTG |

| SeV | GGATCACTAGGTGATATCGAGC | ACCAGACAAGAGTTTAAGAGATATGTAT |

| hIFNα6 | GTGGTGCTCAGCTGCAAGTC | CCAGGAGCATCATGGTCCTC |

| hIFNβ1 | GCAGTTCCAGAAGGAGGACG | TCCAGCCAGTGCTAGATGAATC |

| hIL28A | GCCACATAGCCCAGTTCAAG | TCCTTCAGCAGAAGCGACTC |

| hISG54 | GGAGGGAGAAAACTCCTTGGA | GGCCAGTAGGTTGCACATTGT |

| hIRF7 | AGGGTGACAGGTACGGCTCT | CTCCTGGAGAGGGACAAGAA |

| hRIG-I | CTGGACCCTACCTACATCCTG | GGCATCCAAAAAGCCACGG |

| hGAPDH | ATGGGGAAGGTGAAGGTCG | GGGGTCATTGATGGCAACAATA |

| mIRF3 | GAGAGCCGAACGAGGTTCAG | CTTCCAGGTTGACACGTCCG |

| mIRF7 | GAGACTGGCTATTGGGGGAG | GACCGAAATGCTTCCAGGG |

| mRIG-I | AAGAGCCAGAGTGTCAGAATC | AGCTCCAGTTGGTAATTTCTTGG |

| mIFNα6 | TGGCTAGGCTCTGTGCTTTC | GTCCTTCCTGTCCTTCAGGC |

| mIFNβ1 | CAGCTCCAAGAAAGGACGAAC | GGCAGTGTAACTCTTCTGCAT |

| mIL28A | TACACAGCTTCAGGCCACAG | CAGGTTGGAGGTGACAGAGG |

| mISG54 | AGTACAACGAGTAAGGAGTCACT | AGGCCAGTATGTTGCACATGG |

| mISG56 | CTGAGATGTCACTTCACATGGAA | GTGCATCCCCAATGGGTTCT |

| mGAPDH | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG | TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA |

XChIP.

Dual cross-link chromatin immunoprecipitation (XChIP) was performed as described previously (45). Protein-protein cross-linking was first performed with disuccinimidyl glutarate (2 mM; Pierce), followed by protein-DNA cross-linking with formaldehyde. Equal amounts of sheared chromatin were immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C with 4 μg of the indicated Ab in ChIP dilution buffer (45). Immunoprecipitates were collected with 40 μl protein A magnetic beads (Dynal Inc.), washed, and eluted in 250 μl elution buffer for 15 min at room temperature. Samples were de-cross-linked in 0.2 M NaCl at 65°C for 2 h. The precipitated DNA was phenol-chloroform extracted, precipitated with 100% ethanol, and dried.

Q-gPCR.

Gene enrichment in XChIP was determined by quantitative genomic PCR (Q-gPCR) as previously described (45, 46) using region-specific PCR primers as follows: IRF7 forward, 5′-CCGCTGGTCGCATCCAATA-3′, and IRF7 reverse, 5′-GACGGGAAGTTTCGTCTCGC-3′; RIG-I forward, 5′-AGAACACAATTTTCGTGCCCT-3′, and RIG-I reverse, 5′-ACTTGAGTTCTGGCATTCCCT-3′. Standard curves were generated using a dilution series of genomic DNA (from 1 ng to 100 ng) for each primer pair. The fold change of DNA in each immunoprecipitate was determined by normalizing the absolute amount to the input DNA reference and calculating the fold change relative to that amount in unstimulated cells.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

A549 cells plated on coverslips were mock or RSV infected or VP-16 treated for the indicated times. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4. The cells were then incubated for 60 min at 37°C with anti-γH2AX Ab diluted 1:200 in PBS-T (PBS–0.1% Tween 20). Cells were washed three times in PBS-T and incubated with secondary fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-rabbit Ab in PBS-T for1 h at 22°C. Confocal microscopy was performed on a Zeiss LSM510 META system. Images were captured at a magnification of ×40.

Quantification of γH2AX was performed by converting images to 8-bit and integrating signal intensity above threshold in ImageJ. The signal threshold was determined by negative-control staining. Three images were analyzed for each treatment condition.

Statistical analysis.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed when looking for time differences followed by Tukey's post hoc test to determine significance. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Increased replication of RSV and Sendai virus in ATM-silenced A549 cells.

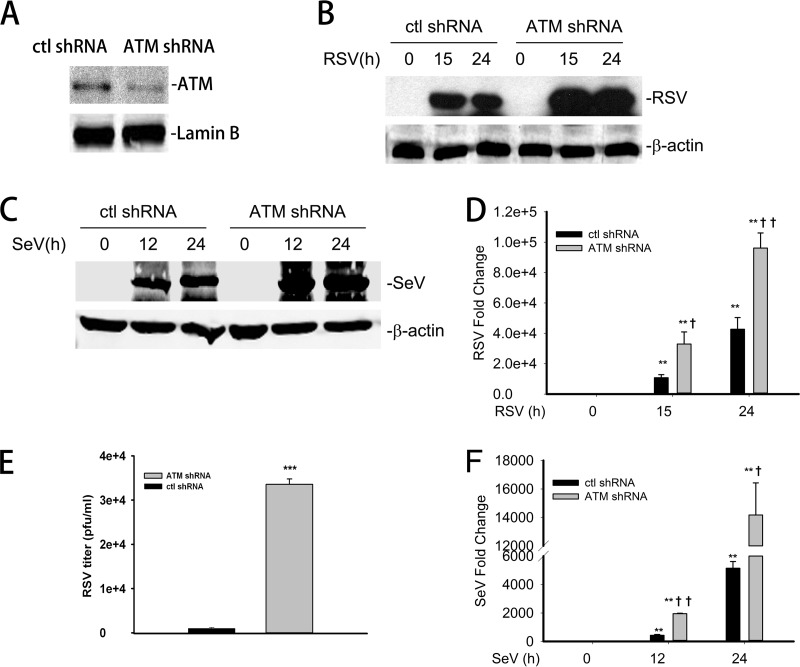

Our earlier studies documented that the nuclear ROS and DNA damage sensor, ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), plays a central role in cytokine-induced RelA activation (39). Here, we investigated whether ATM plays an essential role in the antiviral IIR (Fig. 1). First, we developed an A549 cell line stably transfected with either control shRNA (control-shRNA-A549 cells) or an ATM-specific shRNA (ATM-shRNA-A549 cells; see Materials and Methods). A549 cells were chosen because these are human epithelial cells that express surfactant and tannic acid-positive lamellar bodies, characteristics of type II alveolar cells, and are a well-established model of permissive RSV infection (13, 47, 48). We found that ATM-shRNA-A549 cells show ∼75% depletion of steady-state ATM by Western blotting compared to that of control-shRNA-A549 cells (Fig. 2A). Control- and ATM-shRNA-A549 lines were mock infected or infected with RSV (multiplicity of infection [MOI], 1.0) for 15 and 24 h. Cells were lysed, and the expression level of RSV F1 protein was measured by Western blotting. Undetectable in mock-infected cells, high expression of RSV F1 protein was observed after 15 h of infection in both cell types; however, RSV F1 was significantly higher in ATM-shRNA-A549 than in control-shRNA-A549 cells. RSV F1 expression continued to accumulate throughout the duration of the 24-h experiment (Fig. 2B). RSV transcription was quantified by Q-RT-PCR. We observed a >1,000-fold increase in the expression of RSV nucleocapsid (N) mRNA transcripts in control-shRNA-A549 cells after 15 h of RSV infection, which further increased to ∼4,000-fold 24 h after infection. Consistent with the Western blot data, an ∼4-fold-higher level of N mRNA transcripts was observed in ATM-shRNA-A549 cells than in controls at both time intervals after infection (Fig. 2D). Finally, RSV virion production was quantified in control- and ATM-shRNA-A549 cells. A significantly increased titer of RSV was observed in ATM-shRNA-A549 cells, consistent with the increase in RSV transcription (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2E). Together, these results demonstrated a robust increase in RSV replication in ATM shRNA-transfected A549 cells, suggesting that ATM depletion may result in an impaired cellular innate response.

FIG 2.

Enhanced RSV and Sendai virus replication in ATM knockdown cells. (A) A549 cells were transfected with ATM shRNA; 72 h later, equal amounts of nuclear extract (NE) were analyzed by Western blotting to detect ATM. Lamin B was used as internal control. (B) Control-shRNA-A549 or ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were infected with RSV (MOI, 1.0) for 0, 15, or 24 h. Equal amounts of whole-cell extract (WCE) were analyzed by WB to determine the level of RSV protein expression. β-Actin was used as internal control. (C) Control-shRNA-A549 or ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were mock infected or infected with SeV (MOI, 1.0) for 15 or 24 h. Equal amounts of WCE were used to determine the SeV protein expression by WB. Shown is SeV nucleoprotein (NP). β-Actin was used as internal control. (D) Control-shRNA-A549 or ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were mock or RSV infected (MOI, 1.0) for 15 or 24 h. Total RNA was extracted. Fold changes in the mRNA level of RSV N protein were measured. (E) Control-shRNA-A549 or ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were RSV infected (MOI, 1.0) for 48 h. The RSV titer (PFU/ml) was determined by methylcellulose plaque assay. (F) Control-shRNA-A549 or ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were mock or SeV infected (MOI, 1.0) for 15 or 24 h. The fold changes in SeV mRNA were measured. *, significantly different from RSV- or SeV-treated (0 h) samples, P < 0.05; **, significantly different from RSV- or SeV-treated (0 h) samples, P < 0.01; †, significantly different from ATM+/+ samples, P < 0.05; ††, significantly different from ATM+/+ samples, P < 0.01.

To further investigate whether the defective cellular response in ATM-depleted cells is specific only to RSV exposure, we challenged ATM-shRNA-A549 cells with Sendai virus (SeV). We also observed a significantly higher expression of SeV NP in the ATM-shRNA-A549 cells than in the control-shRNA-A549 cells 15 and 24 h after infection (Fig. 2C). This result was further confirmed by Q-RT-PCR measurement, which showed a ∼3-fold-higher mRNA expression of SeV NP in ATM-shRNA-A549 cells than in controls (Fig. 2F). Taken together, these results clearly demonstrated increased virus transcription and in ATM-depleted A549 cells, suggesting an essential role of ATM in mediating the antiviral response to paramyxoviruses.

RSV- and poly(I·C)-induced IFNs are ATM dependent.

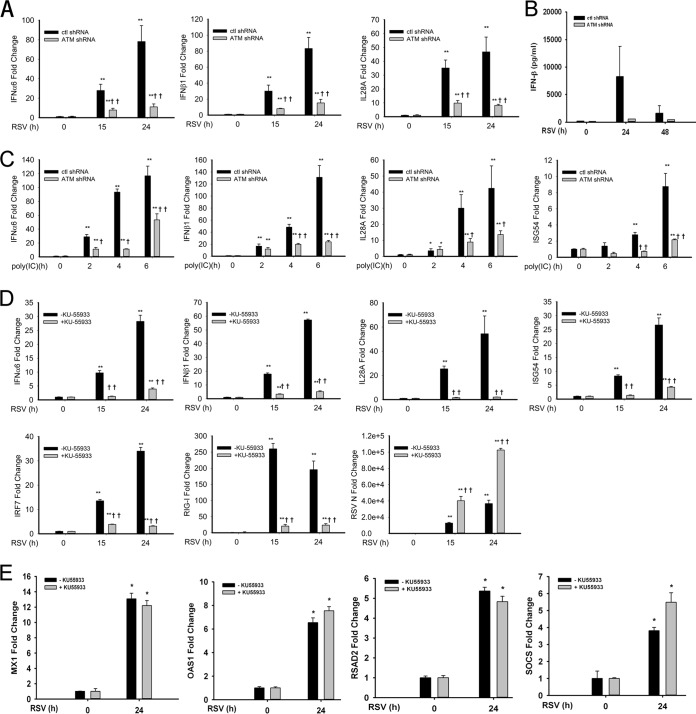

To further understand the role of ATM in the antiviral response, relative changes in mRNA abundance of type I IFN (IFN-α6 and IFN-β1) and type III IFN (interleukin-28A [IL-28A]) were measured after RSV infection. A time-dependent increase in the mRNA expression of these genes was observed in control shRNA-transfected cells. The mRNA transcript levels of IFN-α6, IFN-β1, and IL-28A genes were increased 80-fold, 90-fold, and 45-fold, respectively, 24 h postinfection (p.i.), compared to the levels in uninfected cells. In contrast, in ATM-shRNA-A549 cells, induction of the same genes was significantly lower at both 15 and 24 h after RSV infection (Fig. 3A). At 24 h p.i., transcript levels were reduced 18-fold, 20-fold, and 10-fold in ATM-shRNA-A549 cells (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3A). To confirm that changes in IFN-β synthesis were congruent with IFN-β secretion, the abundance of IFN-β protein in the cell culture supernatant was assayed by ELISA. In control-shRNA-A549 cells, RSV infection produced secretion of 7.5 ng/ml at 24 h p.i., falling to 2.0 ng/ml at 48 h p.i. (Fig. 3B) (P < 0.001 compared to mock-infected cells). In contrast, ATM-shRNA-A549 cells secreted significantly less IFN-β at each time point (P < 0.01 at 24 h, and P < 0.05 at 48 h). These results indicate an essential role of ATM in RSV-induced expression of mucosal IFNs.

FIG 3.

ATM disruption suppresses IFN and ISG expression after RSV infection or poly(I·C) treatment. (A) Control-shRNA-A549 and ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were mock or RSV infected (MOI, 1.0) for 15 or 24 h. Fold changes of mRNA for IFN-α6, IFN-β1, IL-28A, and ISG54 were measured by Q-RT-PCR. (B) Conditioned medium from control-shRNA-A549 and ATM-shRNA-A549 cells taken 0, 24, or 48 h p.i. was assayed for IFN-β protein by ELISA. (C) Control-shRNA-A549 and ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were electroporated with 10 μg poly(I·C) for 2, 4, or 6 h. Fold changes of mRNA for IFN-α6, IFN-β1, IL-28A, and ISG54 were measured. (D) hSAECs were infected with RSV (MOI, 1.0) for 0, 15, or 24 h with or without KU-55933 pretreatment (10 μM, 1 h). Fold changes in mRNA of IFN-α6, IFN-β1, IL-28A, ISG54, IRF7, and RIG-I were measured. (E) hSAECs were infected with RSV (MOI, 1.0) for 0 or 24 h with or without KU-55933 treatment as above. Fold changes in mRNA of MX1, OAS1, RSAD2/CIG5, and SOCS were determined by Q-RT-PCR. *, significantly different from RSV- or poly(I·C)-treated (0 h) samples, P < 0.05; **, significantly different from RSV- or poly(I·C)-treated (0 h) samples, P < 0.01; †, significantly different from ATM+/+ samples, P < 0.05; ††, significantly different from ATM+/+ samples, P < 0.01.

Furthermore, we investigated if ATM is required for IFN expression after stimulation with a dsRNA analog, poly(I·C). In control-shRNA-A549 cells, poly(I·C) stimulation induced 120-fold, 140-fold, 40-fold, and 10-fold inductions of mRNA expression of IFN-α6, IFN-β1, IL-28A, and ISG54 genes, respectively, 6 h after exposure. In contrast, ATM knockdown significantly prevented the poly(I·C)-induced expression of these same genes, with changes reduced to 55-fold, 25-fold, 15-fold, and 2-fold, respectively (Fig. 3C) (P < 0.01).

To establish that this effect was not observed in A549 cells only, we examined the requirement of ATM for the antiviral immune response in primary human small airway epithelial cells (hSAECs). For this purpose, we mock infected hSAECs or infected them with RSV for 15 and 24 h in the absence or presence of pretreatment with KU-55933, a specific small-molecule ATM inhibitor (49). RSV induced the expression of IFN-α6, IFN-β1, IL-28A, ISG54, IRF7, and RIG-I genes 30-fold, 60-fold, 55-fold, and 28-fold 24 h after infection. Expression of the same genes was significantly reduced in the presence of KU-55933, down to 5-fold, 5-fold, 2-fold, and 5-fold, respectively (Fig. 3D) (P < 0.01). To exclude an off-target effect of KU-55933 on RSV replication, RSV N transcripts were quantitated in the same experiment. Here, RSV N transcripts were even greater in the KU-55933-treated cells (Fig. 3D).

Finally, to examine the requirement of ATM on other ISGs, the expression of MX1, OAS1, RSAD2/CIG5, and SOCS was measured in hSAECs treated in the absence or presence of KU-55933 pretreatment. Here, RSV effected 12.5-fold, 7-fold, 4.8-fold, and 5.5-fold inductions, respectively. The expression levels of these ISGs were not significantly different between cells treated with or without KU-55933. Taken together, these results suggest a novel and critical role of ATM in type I and III IFN responses after RSV infection and poly(I·C) treatment, affecting a subset of ISGs (notably, ISG-54 and ISG-56).

RSV induces DSBs, activates ATM, and promotes IKKγ-dependent ATM export.

In response to oxidative stress and/or the induction of DNA DSBs, ATM is activated by autophosphorylation at Ser 1981 (50). Therefore, we sought to further explore whether cytoplasmic ssRNA viral replication activated ATM. A549 cells were infected with RSV for 15 and 24 h, and changes in formation of phospho-Ser 1981 ATM were measured by Western blotting. Phospho-Ser 1981 ATM levels were undetectable in extracts from uninfected cells, whereas phospho-Ser 1981 ATM was significantly increased at 15 and 24 h of RSV infection (Fig. 4A). These data clearly demonstrate that RSV replication activates ATM.

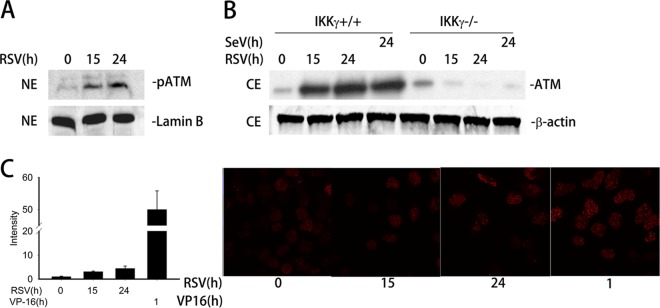

FIG 4.

ATM is activated by RSV-induced DSB and requires IKKγ for nuclear export. (A) A549 cells were mock or RSV infected (MOI, 1.0) for 15 or 24 h. Equal amounts of nuclear extract (NE) were assayed to detect the level of phospho-Ser 1981 ATM (pATM) by Western blotting (WB). Lamin B was used as internal control. (B) IKKγ+/+ and IKKγ−/− MEFs were mock or RSV infected (MOI, 1.0) for 15 or 24 h or with SeV (MOI, 1.0) for 24 h as indicated. ATM was detected in equal amounts of cell extract (CE) by WB. β-Actin was used as internal control. (C) Right panel, A549 cells were mock or RSV infected (MOI, 1.0) for 15 or 24 h or treated with VP16 (10 μM) for 1 h as indicated. The cells were fixed, incubated with anti-γH2AX Ab, and then stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary Ab. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). The slides were imaged using confocal microscopy. The expression of γH2AX is shown in red. Left panel, quantification of the signal intensity.

In both the DSB-induced DNA damage response and TNF-signaling pathways, ATM activation is coupled with IKKγ/NEMO-dependent nuclear-to-cytoplasmic export (39, 51). We next investigated whether RSV infection also induces IKKγ/NEMO-dependent ATM nuclear export. For this experiment, IKKγ+/+ and IKKγ−/− MEFs were mock or RSV infected for 15 and 24 h; cells infected with SeV served as a comparison. Cytoplasmic extracts (CEs) were prepared and assayed for changes in ATM abundance by Western blotting. Cytoplasmic abundance of ATM was very low in uninfected cells; however, ATM export was detectable in CEs of IKKγ+/+ MEFs 15 h after RSV infection and persisted until 24 h (Fig. 4B, left). Importantly, no cytoplasmic ATM was detected in IKKγ−/− MEFs at any time point (Fig. 4B, right). Similarly, SeV infection also resulted in the cytoplasmic accumulation of ATM only in IKKγ+/+ MEFs but not in IKKγ−/− MEFs (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that ATM activation following RSV infection is coupled with its nuclear export, an event that is dependent on IKKγ/NEMO.

Oxidative DNA strand damage precedes ATM activation following a variety of stimuli, including ionizing irradiation and TNF (39, 50). We next assessed whether RSV infection induces DSBs. An early cellular response to DSBs is the ATM-dependent phosphorylation of H2AX at Ser 139 to produce γH2AX (52, 53). Thus, we measured the intensity of γH2AX foci as a marker of DSB after RSV infection by immunofluorescence microscopy. A549 cells were mock or RSV infected for 15 and 24 h and then stained by γH2AX antibody. VP-16, a potent DSB-inducing chemotherapeutic drug (54), was used as a positive control. As shown in Fig. 4C, RSV infection induced a 5-fold increase in γH2AX foci compared to what was seen in uninfected cells (right panel). VP-16 induced a >50-fold increase in γH2AX foci, indicating that it is a much more potent stimulus of DSB formation. These results suggest that RSV infection weakly induces DSB and ATM activation.

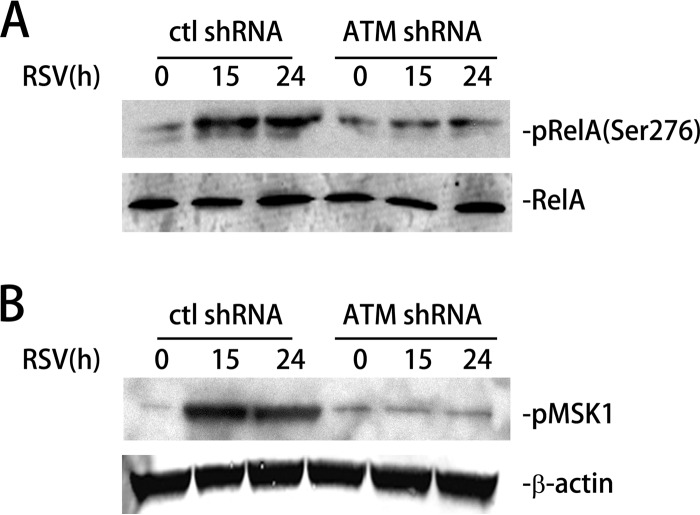

RSV-induced activation of the RelA Ser 276 kinase, MSK1, is ATM dependent.

Earlier, we reported that RSV infection increases ROS production, as measured by 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (H2DCF) oxidation and by time-dependent decrease in the cytoplasmic glutathione (GSH)-to-disulfide glutathione (GSSG) ratio (37). Elevated ROS leads to MSK1-mediated RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation, an essential posttranslational modification that is important for the expression of a subset of NF-κB-dependent genes (37). Therefore, we next examined whether RSV-induced RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation is ATM dependent. For this purpose, control-shRNA-A549 and ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were mock or RSV infected for 15 and 24 h. Cells were lysed, total RelA was immunoprecipitated, and the abundance of phospho-Ser 276 RelA was quantitated by Western blotting. Relative to mock-infected cells, RSV infection increased phospho-Ser 276 RelA levels 4-fold after 15 h, a level that persisted until 24 h (Fig. 5A). However, in the ATM-shRNA-A549 cells, the abundance of phospho-Ser 276 RelA levels was not changed relative to that of mock-infected cells, suggesting that ATM is important for RSV-induced RelA-Ser 276 phosphorylation (Fig. 5A).

FIG 5.

RSV-induced phospho-Ser 376 MSK1 and phospho-Ser 276 RelA formation is ATM dependent. (A) Control-shRNA-A549 and ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were mock or RSV infected (MOI, 1.0) for 15 or 24 h. Phospho-Ser 276 RelA (top) and total RelA (bottom) were detected in whole-cell extract (WCE) using Western blotting (WB). (B) Control-shRNA-A549 or ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were mock or RSV infected (MOI, 1.0) for 15 or 24 h. Phospho-Ser 375 MSK1 (pMSK1) was detected by WB. β-Actin was used as internal control.

Because RSV-induced RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation is MSK1 dependent (37), we further evaluated the requirement of ATM in RSV-induced MSK1 activation. For this purpose, control-shRNA-A549 and ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were mock or RSV infected for 15 and 24 h, and changes in phospho-Ser 376 MSK1 were determined by Western blotting. In control-shRNA cells, RSV infection induced a significant 10-fold induction of phospho-Ser 376 MSK1 at 15 h p.i. (Fig. 5B). However, in ATM-shRNA-A549 cells, the induction of phospho-Ser 376 MSK1 was completely attenuated (Fig. 5B). This result suggests that ATM is required for RSV-induced MSK1 Ser 276 phosphorylation and activation. Taken together, we conclude that ATM mediates RSV-induced RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation via MSK1.

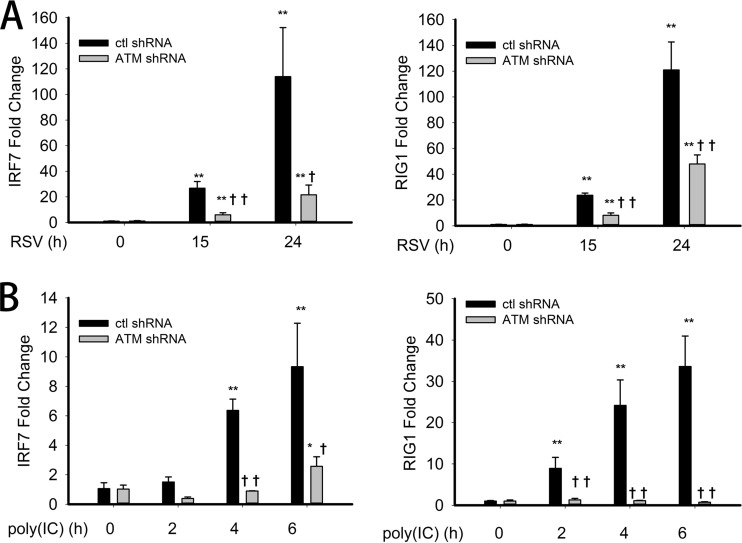

RSV- and poly(I·C)-induced IRF7 and RIG-I expression levels are ATM dependent.

Several studies have reported a link between NF-κB activation and IFN gene expression. In this context, IRF7 gene expression is NF-κB dependent, whereby IRF7 upregulates RIG-I expression (35, 36). Since observed ATM plays a critical role in RSV-induced RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation, we examined whether ATM affected RSV-induced IRF7 expression and that of its downstream target, RIG-I. For this purpose, control-shRNA-A549 and ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were mock or RSV infected for 15 and 24 h, and the expression of IRF7 and RIG-I mRNA was measured by Q-RT-PCR. In control-shRNA-A549 cells, RSV induced 20- and 100-fold induction of IRF7 gene expression 15 and 24 h after RSV infection, respectively. However, in ATM-shRNA-A549 cells, IRF7 expression was significantly reduced to 5-fold and 20-fold at the 15 and 24 h time points (Fig. 6A, left). RSV-induced RIG-I gene expression showed a similar behavior. RSV induced RIG-I mRNA 20-fold and 120-fold at the 15 and 24 h time points, respectively. These induction levels were reduced significantly to 10-fold and 50-fold, respectively, in ATM-shRNA-A549 cells (Fig. 6A, right panel) (P < 0.01). We note that a similar pattern of IRF7 and RIG-I expression was observed in the hSAECs treated with the ATM kinase inhibitor (Fig. 3B), indicating that this linkage is important in primary human small airway epithelial cells.

FIG 6.

Suppressed IRF7 and RIG-I expression upon RSV infection and poly(I·C) treatment in ATM knockdown cells. (A) Control-shRNA-A549 or ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were mock or RSV infected (MOI, 1.0) for 15 or 24 h. Fold changes in IRF7 and RIG-I mRNA abundance were measured by Q-RT-PCR. (B) Control-shRNA-A549 or ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were electroporated with 10 μg poly(I·C) for 0, 2, 4, or 6 h. Fold changes in IRF7 and RIG-I were measured. *, significantly different from RSV- or poly(I·C)-treated (0 h) samples, P < 0.05; **, significantly different from RSV- or poly(I·C)-treated (0 h) samples, P < 0.01; †, significantly different from ATM+/+ samples, P < 0.05; ††, significantly different from ATM+/+ samples, P < 0.01.

To further extend our findings, IRF7 and RIG-I gene expression was measured in poly(I·C)-stimulated control-shRNA-A549 or ATM-shRNA-A549 cell lines. Consistent with the expression pattern seen in response to RSV stimulation, poly(I·C) treatment induced an 8-fold increase in IRF7 mRNA abundance in control-shRNA-A549 cells 6 h after stimulation, which was significantly reduced to 3-fold in ATM-shRNA-A549 cells (Fig. 6B, left panel) (P < 0.01). Also, poly(I·C) induced RIG-I mRNA 35-fold in control-shRNA-A549 cells 6 h after stimulation but only 2-fold in ATM-shRNA-A549 cells (Fig. 6B, right panel) (P < 0.01). Taken together, these results demonstrated the requirement of ATM in RSV- and poly(I·C)-induced IRF7 and RIG-I gene expression.

Phospho-Ser 276 RelA is required for the cellular antiviral IFN response.

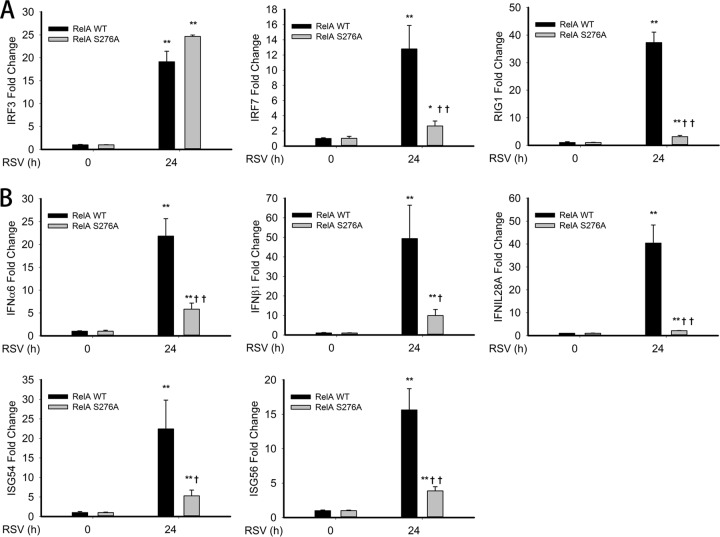

To further understand the role of phospho-Ser 276 RelA in RSV-induced IFN and ISG expression, we examined IRF7 and RIG-I expression in RelA−/− MEFs selectively expressing either RelA wild-type (WT) MEFs or the nonphosphorylatable RelA Ser276Ala (S276A) mutant MEFs (14). RelA WT and RelA S276A MEFs were mock or RSV infected for 24 h, and the corresponding antiviral gene expression was measured. We observed a 20-fold induction of IRF3, a 13-fold induction of IRF7, and a 38-fold induction of RIG-I gene expression after RSV infection in RelA WT MEFs (Fig. 7A). However, in RelA S276A MEFs, RSV infection induced IRF7 and RIG-I gene expression to levels that were significantly reduced (3-fold and 2-fold over mock infection, respectively) while IRF3 gene expression was unaffected (Fig. 7A). These findings indicate that both IRF7 and RIG-I, but not IRF3, mRNA expression is dependent on RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation after RSV infection.

FIG 7.

RSV-induced IRF7-RIG-I expression is RelA Ser276A dependent. (A) RelA-deficient MEFs stably expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-tagged RelA WT (RelA WT) or EGFP-tagged nonphosphorylatable Rel Ser 276 Ala mutant (RelA S276A) was mock or RSV infected (MOI, 1.0) for 24 h. Fold changes in IRF3, IRF7, and RIG-I mRNA expression were measured by Q-RT-PCR. (B) RelA WT and Rel Ser276A MEFs were mock infected or infected as described for Fig. 6A. IFN-α6, IFN-β1, IL-28A, ISG54, and ISG56 mRNA abundance was measured. *, significantly different from RSV- or poly(I·C)-treated (0 h) samples, P < 0.05; **, significantly different from RSV or poly(I·C)-treated (0 h) samples, P < 0.01; †, significantly different from RelA WT samples, P < 0.05; ††, significantly different from RelA WT samples, P < 0.01.

We next investigated the requirement of phospho-Ser 276 RelA in RSV-induced IFN and ISG gene expression. In RelA WT MEFs, we found that mRNA abundance of IFN-α6, IFN-β1, IL-28A, ISG54, and ISG56 genes were dramatically increased 24 h after RSV infection 20-, 50-, 40-, 20-, and 15-fold, respectively (Fig. 7B). However, expression levels of all these genes were significantly reduced in RelA S276A MEFs to 7-fold, 10-fold, 5-fold, 5-fold, and 4-fold, respectively (Fig. 7B). Together, these data suggest that RSV-induced type I/III IFN and ISG expression levels are RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation dependent. Taken together, these results demonstrated the requirement of the phospho-Ser 276 RelA-IRF7-RIG-I pathway in the antiviral response.

ATM is required for recruiting RelA-transcriptional elongation complex to the IRF7 gene promoter.

Our work demonstrates the requirement of ATM for RSV-induced phospho-Ser 276 RelA formation and that of phospho-Ser 276 RelA on IRF7 and RIG-I gene expression. Earlier, we reported that phospho-Ser 276 RelA-dependent immediate early gene expression is regulated via its interaction with cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) resulting in RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II) phosphorylation, a biochemical event necessary for gene expression via transcriptional elongation (55).

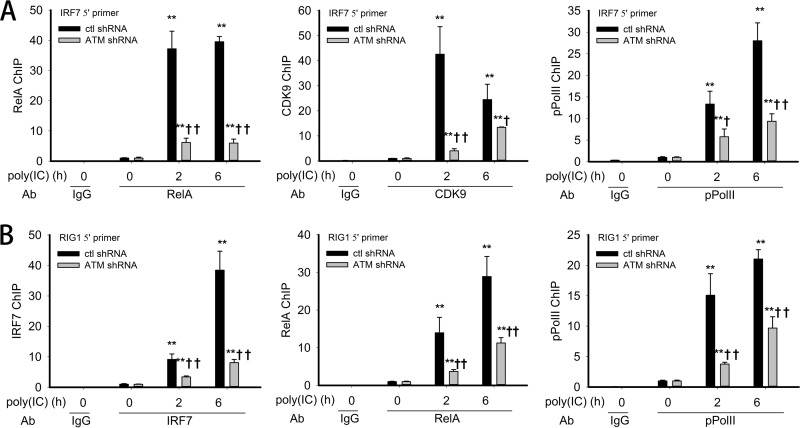

Reasoning that RSV-induced IRF7 expression might be mediated by a RelA-dependent transcriptional elongation mechanism, we next investigated whether ATM is required for the recruitment of RelA, CDK9, or phospho-Ser 2 Pol II to the endogenous IRF7 promoter. Control-shRNA-A549 or ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were electroporated with poly(I·C); cross-linked chromatin was subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-RelA, CDK9, or phospho-Ser 2 Pol II Abs using an optimized dual cross-link XChIP assay (see Materials and Methods). Relative to mock-infected cells, poly(I·C) stimulation rapidly induced a 40-fold induction of RelA binding to the IR7 promoter at 2 h, persisting after 6 h of treatment (Fig. 8A, left panel). We also observed an early, transient induction of CDK9 binding to the IRF7 promoter, peaking at 40-fold 2 h after stimulation and falling to 25-fold at 6 h (Fig. 8A, middle panel). Finally, phospho-Ser 2 Pol II binding increased to 15-fold after 2 h and further increased to 28-fold 6 h after treatment (Fig. 8A, right panel). However, in ATM-shRNA-A549 cells, RelA binding was reduced at both time points (Fig. 8A), with the early 2 h peak in CDK9 binding being significantly inhibited and the corresponding phospho-Ser 2 Pol II being reduced by half (Fig. 8A). These results illustrate that ATM regulates RSV-induced expression of the IRF7 gene by regulating the recruitment of RelA and the transcriptional elongation complex prior to RNA Pol II C-terminal domain (CTD) phosphorylation.

FIG 8.

Requirement of ATM in RelA/coactivator recruitment to IRF7 and IRF7 recruitment to RIG-I gene promoters. (A) Control-shRNA-A549 or ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were electroporated with 10 μg poly(I·C) for 0, 2, or 6 h. The corresponding chromatin was dually cross-linked and immunoprecipitated with anti-RelA, anti-CDK9, and anti-phospho Ser 2 Pol II (pPol II) Abs. IgG was the negative control. The fold change in IRF7 gene enrichment was quantified by Q-gPCR using the IRF7 5′ primer set. (B) XChIP was performed as described for Fig. 7A. The corresponding chromatin was immunoprecipitated with anti-IRF7, anti-RelA, and anti-pPol II Abs. IgG was the negative control. Fold change in RIG-I gene enrichment was quantified by Q-gPCR using the RIG-I 5′ primer set. *, significantly different from TNF-treated (0 h) samples, P < 0.05; **, significantly different from TNF-treated (0 h) samples, P < 0.01; †, significantly different from ATM+/+ samples, P < 0.05; ††, significantly different from ATM+/+ samples, P < 0.01.

ATM is required for recruiting IRF7 and RelA to the RIG-I gene promoter.

Earlier, we predicted and confirmed experimentally that RIG-I gene expression is functionally controlled by IRF7 (36); however, the transcriptional activation mode was not defined. To address this question, we investigated if poly(I·C) induced IRF7 and RelA binding to the endogenous RIG-I promoter. Control-shRNA-A549 or ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were stimulated with poly(I·C) and cross-linked chromatin immunoprecipitated with anti-IRF7, RelA, or phospho-Ser 2 Pol II Abs in the XChIP assay. In control shRNA-A549 cells, IRF7 binding was 8-fold at 2 h and 40-fold at 6 h after stimulation (Fig. 8B, left panel). Similarly, RelA binding was induced in control-shRNA-A549 cells 15-fold and 30-fold after poly(I·C) stimulation (Fig. 8B, middle panel). We note that these kinetics are delayed compared to the same transcription factors binding to the IRF7 gene (cf. Fig. 8A), suggesting that the IRF7 gene is in a more accessible chromatin environment than RIG-I. Finally, phospho-Ser 2 Pol II is inducibly enriched on the native RIG-I promoter 15-fold and 20-fold 2 and 6 h after poly(I·C) stimulation (Fig. 8B, right panel).

In contrast, in the ATM-shRNA-A549 cells, poly(I·C)-induced IRF7, RelA, and phospho-Ser 2 Pol II binding levels are significantly reduced compared to those of control-shRNA cells (Fig. 8B). Together, these data indicate that ATM is essential for dsRNA-inducible binding of the IRF7 and RelA transcription factors to the RIG-I gene promoter.

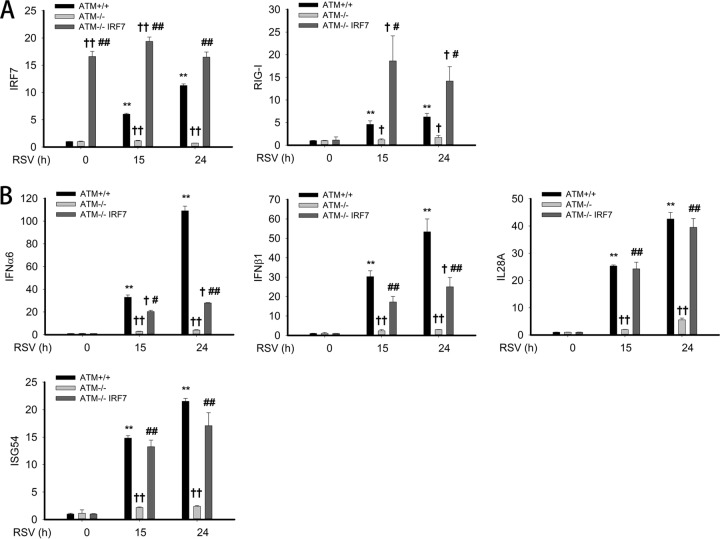

IRF7 overexpression restores antiviral response in ATM-silenced A549 cells.

Our experiments demonstrated that RSV- and poly(I·C)-induced IRF7 gene expression was significantly reduced in ATM-shRNA-A549 cells (Fig. 6) and that IRF7 was induced to bind the native RIG-I promoter (Fig. 8B). Interpreting these results together with our previous work showing that the functional requirement of IRF7 in RIG-I gene expression (36) suggested that IRF7 plays a major role in mediating RIG-I expression, we therefore examined whether overexpression of IRF7 can restore RIG-I gene expression and downstream IFN/ISG gene expression in ATM-silenced cells. ATM-shRNA-A549 cells were therefore transiently transfected with empty vector or IRF7 expression vector; 72 h later, cells were mock or RSV infected for 15 or 24 h. To confirm expression of IRF7, IRF7 mRNA expression was measured. Here, a 16-fold increase in IRF7 transcripts was observed relative to IRF7 transcripts in control-shRNA and ATM-shRNA-A549 cells, and their abundance was not affected by RSV infection (Fig. 9A). Confirming our previous experiments, we observed that RIG-I expression was induced in control-shRNA-A549 cells at 15 and 24 h to levels much greater than that seen in ATM-shRNA-A549 cells (note that because these data are expressed as fold change relative to uninfected controls, a number that is very close to 0, the absolute fold change number varies from experiment to experiment). Strikingly, RIG-I mRNA induction is highly induced in IRF7-transfected ATM-shRNA-A549 cells in response to RSV infection, to levels greater than that seen in control-shRNA-A549 cells (Fig. 9A). This result indicates that IRF7 expression is necessary and sufficient for virally inducible RIG-I gene expression and that RIG-I expression is rate limited by IRF7 abundance.

FIG 9.

Exogenous IRF7 rescues antiviral gene expression in ATM-shRNA-A549 cells. (A) Expression vectors encoding empty vector or IRF7 were transfected into ATM-shRNA-A549 cells; 72 h later, cells were mock or RSV infected (MOI, 1.0) for 15 or 24 h. mRNA levels of IRF7 and RIG-I were measured by Q-RT-PCR. (B) The same total RNA as in panel A were extracted. mRNA levels of IFN-α6, IFN-β1, IL-28A, and ISG54 were measured. †, significantly different from ATM+/+ samples, P < 0.05; ††, significantly different from ATM+/+ samples, P < 0.01; #, significantly different from ATM-shRNA-A549 samples, P < 0.05; ##, significantly different from ATM-shRNA-A549 samples, P < 0.01.

Next, we examined the transcript levels of type I IFN (IFN-α6, IFN-β1), type III IFN (IL-28A), and ISG54 in the same experiment. Ectopic IRF7 expression completely restored IL-28A and ISG54 expression to that of control-shRNA-A549 cells and partially restored IFN-α6 and IFN-β1 expression (Fig. 9B). Taken together, these results demonstrated the requirement of IRF7 in inducible RIG-I gene expression and type III IFN/ISG expression.

DISCUSSION

RSV is a significant respiratory pathogen of otherwise healthy children and of immunocompromised adults. Although the etiology of RSV-induced LRTI is probably multifactoral, current pathogenesis studies indicate a significant role for an exaggerated host mucosal innate immune response (56). RSV replicates in airway epithelial cells, inducing ROS production (57) and activating the innate immune response to produce protective antiviral ISGs and proinflammatory cytokines. In this study, we investigated the role of the nuclear ROS sensor, ATM, in regulating the antiviral immune response pathway. Our data suggest that RSV replication is enhanced in cells depleted of ATM and that these cells show major perturbations of type I and III expression yet retain IRF3-dependent gene expression. RSV replication activates ATM by enhanced ROS and weak induction of DSBs, resulting in its phosphorylation, and IKKγ/NEMO-dependent nuclear export and is required for RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation through phospho-Ser 376 MSK1 formation. Furthermore, we discovered that virus-inducible IRF7 gene expression is phospho-Ser 276 RelA dependent via a transcriptional elongation mechanism and that IRF7 is a primary regulator of RIG-I gene expression. RIG-I amplification is required for the downstream IFN expression and therefore affects the cellular antiviral response. More study will be required to identify the IFN-inducible factors responsible for restriction of RSV replication. We conclude that ATM plays a major role in the NF-κB-IRF cross talk pathway required for phospho-Ser 276 RelA formation, coupling to IRF7-RIG-I amplification of IFN expression and antiviral response (schematically shown in Fig. 10).

FIG 10.

Working model for the role of ATM in the phospho-RelA-mediated antiviral response. RSV-induced oxidative stress and/or DSB activates ATM to autophosphorylate and induces its IKKγ-dependent export. In the cytosol, ATM is required for RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation by MSK1. RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation is required for IRF7 gene expression. RIG-I gene expression is mediated by IRF7, and resynthesized RIG-I plays an essential role in the antiviral response.

The cellular DNA damage response pathway is known to be a target of DNA viruses, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), simian virus 40 (SV40), and others. Here, nuclear viral genetic replication is known to trigger the single-strand and nucleotide excision repair pathways (58). In this setting, activation of the DNA damage response occurs through γH2AX focus formation, ATM activation, and p53-mediated cell cycle arrest, events that promote viral replication and/or entrance into latency (59, 60). We interpret our findings that either RSV or SeV replication induces γH2AX focus formation, promotes ATM Ser 1981 phosphorylation, and stimulates cytoplasmic ATM accumulation to mean that ATM is activated also in response to cytoplasmic ssRNA virus replication. ATM activation by RSV and SeV has not yet been described to our knowledge. We note, however, that others have observed that RSV can induce lung epithelial cell cycle arrest through a p53-dependent pathway; these results are indirectly consistent with our findings because ATM is a major regulator of p53 activation (61). ATM is a nuclear ROS sensor activated by oxidative stress or by the induction of DSBs (63). We note that RSV, SeV, and poly(I·C) are potent inducers of ROS stress through mitochondrial and TLR-dependent mechanisms (37, 64). Others have shown that oxidative stress alone is sufficient to activate ATM Ser 1981 phosphorylation and nuclear export (65). Alternatively, ATM is activated by DSBs. In this pathway, the Mre11/RAD50/NBS1 (MRN) complex forms on DSBs, recruiting and activating ATM. We note that RSV is a relatively weak inducer of DSBs, assessed by an ∼5-fold change in γ2HAX foci compared to the much greater number of foci produced by the VP-16 DNA-damaging agent (Fig. 3). The relative contributions of ROS or DSBs in paramyxovirus-induced ATM activation will require further investigation.

Our data show that RSV- and SeV-induced ATM cytoplasmic-to-nuclear transport is dependent on the IKKγ/NEMO regulatory subunit of the IκB kinase. In the DNA damage response pathway, ATM undergoes IKKγ/NEMO export by sequential posttranslational modifications catalyzed by a complex containing poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase, the PARP-1/PIASy/ATM complex (66). Here it has been shown that sumoylated IKKγ is phosphorylated on Ser 85 of its NH2 terminus by ATM, a trigger for its ubiquitylation. The Ub-IKKγ then complexes with ATM for nuclear export (51). In contrast, in a cytokine-induced oxidative stress pathway, our prior studies were unable to demonstrate that IKKγ phosphorylation or direct ubiquitylation was involved in TNF-mediated ATM activation, although ATM formed complexes with IKKγ/NEMO (39). Together, these data suggest that IKKγ/NEMO modifications triggering ATM export may be stimulus dependent. More work is needed to understand how ssRNA virus infections modify the ATM-IKKγ complex.

NF-κB/RelA activation is mediated by two coordinated steps: RelA release from cytoplasmic IκB inhibition and RelA activation through Ser 276 phosphorylation (38, 55, 67). RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation is a critical posttranslational modification controlled by a family of RS6Ks in a stimulus-dependent manner, with RSV-induced RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation being MSK1 dependent, whereas TNF-induced RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation is PKAc dependent (14, 37, 38). In RSV infection, oxidative stress is required for Ser 376 MSK1 phosphorylation. How MSK1 responds to oxidative stress is not clearly known. Here we observed that the nuclear oxidative stress sensor ATM is required for RSV-induced pMSK1 formation and RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation. Previous work using ionizing irradiation has shown that ATM phosphorylates over 55 regulated phosphorylation sites on 31 target proteins in the DNA damage response pathway (68). However, direct phosphorylation of RS6K has not been observed. Our previous study of the role of ATM in the TNF pathway indicated that activated phospho-Ser 1981 ATM binds cytoplasmic PKAc and may serve as a scaffold for forming a PKAc-IKK-RelA complex, promoting RelA Ser 176 phosphorylation. However, we have not been able to demonstrate that ATM stably interacts with pMSK1 in RSV-infected cells (data not shown). Further study will be required to elucidate the details of mechanism of the requirement of ATM on MSK1 activation and RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation.

RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation is a rate-limiting posttranslational modification essential for the activation of a network of early-response genes via a transcriptional elongation mechanism (14, 55). In the setting of RSV infection, RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation is coupled with inducible complex formation with CDK9/BRD4, a ubiquitous transcriptional elongation complex required for Ser2 phosphorylation of the RNA Pol II CTD heptad repeats (14). CTD Ser2 phosphorylation is a rate-limiting activation step required for pausing the release of stalled RNA Pol II, enabling rapid expression of cytokine genes. Our finding here that inducible IRF7 expression is phospho-Ser 276 RelA dependent extends previous work showing that IRF7 expression is NF-κB dependent yet IRF3 independent (35, 69). The transcriptional activation mechanism of how NF-κB regulates IRF7 gene expression was previously unknown. Our XChIP assay data indicating that knockdown of ATM specifically affects CDK9 and phospho-Ser 2 CTD Pol II recruitment suggest that phospho-Ser 276 RelA controls IRF7 gene expression through a transcriptional elongation mechanism. Consistent with this process, we observe that CDK9 binding precedes that of phospho-Pol II (Fig. 7A). We and others have shown that CDK9 is the major Ser2 CTD kinase in epithelial cells (55). In this sense, IRF7 is regulated like an immediate early innate response gene to control RIG-I amplification and robust induction of antiviral IFNs.

RIG-I is a highly inducible pattern recognition receptor (PRR) whose upregulation plays a key role in the IFN amplification loop in response to dsRNA exposure (17). Our previous computational model of the integrated NF-κB-IRF3 signaling network led to the prediction and experimental validation that RIG-I was under IRF7 control (36). RIG-I expression is IRF7 dependent but IRF3 independent (70). Our study here demonstrates that either ATM depletion or the selective expression of the nonphosphorylated RelA S276A mutant significantly blocks RIG-I gene expression. Furthermore, our ChIP assay demonstrates that both IRF7 and RelA inducibly bind to the RIG-I gene promoter in response to viral replication. That IRF7 is necessary and sufficient for RIG-I induction is demonstrated by the rescue of RIG-I expression in ATM-shRNA-A549 cells. Our experiments cannot exclude the possibility that RelA may play a coordinating role in RIG-I induction similar to its cooperative effects on IRF3-induced IFN-β expression (71). Together, we interpret these findings to indicate that RSV-induced RIG-I expression is mediated by an ATM-phospho Ser 276 RelA-IRF7 pathway.

Despite previous findings demonstrating that IFN and ISG gene expression are IRF3 dependent (44), we observe here that depletion of ATM significantly blocks type I, type III, and ISG induction without affecting IRF3. Thus, our observation that IRF3 gene expression was unaffected by the nonphosphorylated mutation of RelA Ser 276 but the IRF7-RIG-I pathway was abated (Fig. 7) suggests that phospho-RelA participates in a cross talk pathway mediated by IRF7 and necessary for RIG-I amplification upstream of IFN/ISG expression. Using a quantitative proteomics reaction monitoring approach, we earlier found that in the early stage of poly(I·C) stimulation, RIG-I proteins decrease, indicating degradation of the activated RIG-I (36). Previous reports have shown that upon dsRNA stimulation, constitutively expressed RIG-I initially undergoes inducible K63-mediated ubiquitination, a modification that promotes its association with MAVS (72). Afterwards, the K63-linked ubiquitination is replaced with K48-linked ubiquitination by the RNF125 ubiquitin ligase, promoting RIG-I's proteasomal degradation (73). Concomitantly, RIG-I is resynthesized through a robust IRF7-dependent induction of its mRNA, replacing the degraded protein. Because ATM is required for virus-inducible IRF7 expression and RIG-I activation, we think that the protein abundance of RIG-I is low in ATM-deficient cells, thereby disrupting the antiviral IFN/ISG response. We interpret this result to mean that RIG-I resynthesis plays a key role in amplification of the antiviral response. It will be of interest to examine the effect of ATM silencing on the protein abundance of innate signaling molecules in response to viral infection.

Our findings for these multiple roles of ATM in regulating the innate pathway have implications for autosomal recessive ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T). A-T patients lack a functional ATM protein and exhibit a wide array of systemic defects, including immunodeficiency, cerebral degeneration, progressive ataxia, premature aging, increased incidence of lymphoid tumorigenesis, and type 2 diabetes (74–77). We note that the majority of A-T patients show humoral and cellular immunodeficiency that significantly contributes to morbidity and mortality in these subjects (78, 79). One mechanism previously proposed to explain immunodeficiency has been IgA and IgG2 immunoglobulin deficiency, but the role of ATM in innate immunity has not been investigated. Our studies are the first to suggest that ATM deficiency in A-T may be associated with primary defects in the innate pathway, affecting both the magnitude and the kinetics of the NF-κB-IRF cross talk pathway that could be a unifying explanation for the global defects in adaptive immunity seen in this disease.

Overall, our current findings suggest that the nuclear ROS and DSB sensor, ATM, plays a central role in the IIR to ssRNA virus infection. Our studies are the first to reveal a central role of ATM in mediating the NF-κB-IRF7 cross talk pathway mediated by phospho-Ser 276 RelA signaling coupled to the IRF7-RIG-I amplification loop required for IFN and ISG expression. These studies have significant implications for immune defects in the pathophysiology of the A-T phenotype.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health grants NCATS UL1TR000071 (to A.R.B.), NHLBI HHSN268201000037C (A.R.B. and I.B.), NIAID AI062885 (A.R.B.), and NIEHS P30 ES006676.

REFERENCES

- 1.Glezen WP, Taber LH, Frank AL, Kasel JA. 1986. Risk of primary infection and reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Dis Child 140:543–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welliver RC. 2004. Respiratory syncytial virus infection: therapy and prevention. Paediatr Respir Rev 5(Suppl A):S127–S133. doi: 10.1016/S1526-0542(04)90024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, Blumkin AK, Edwards KM, Staat MA, Auinger P, Griffin MR, Poehling KA, Erdman D, Grijalva CG, Zhu Y, Szilagyi P. 2009. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. N Engl J Med 360:588–598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nair H, Nokes DJ, Gessner BD, Dherani M, Madhi SA, Singleton RJ, O'Brien KL, Roca A, Wright PF, Bruce N, Chandran A, Theodoratou E, Sutanto A, Sedyaningsih ER, Ngama M, Munywoki PK, Kartasasmita C, Simoes EA, Rudan I, Weber MW, Campbell H. 2010. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 375:1545–1555. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60206-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall CB, Douglas RG Jr, Schnabel KC, Geiman JM. 1981. Infectivity of respiratory syncytial virus by various routes of inoculation. Infect Immun 33:779–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L, Peeples ME, Boucher RC, Collins PL, Pickles RJ. 2002. Respiratory syncytial virus infection of human airway epithelial cells is polarized, specific to ciliated cells, and without obvious cytopathology. J Virol 76:5654–5666. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5654-5666.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aherne W, Bird T, Court SD, Gardner PS, McQuillin J. 1970. Pathological changes in virus infections of the lower respiratory tract in children. J Clin Pathol 23:7–18. doi: 10.1136/jcp.23.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welliver TP, Garofalo RP, Hosakote Y, Hintz KH, Avendano L, Sanchez K, Velozo L, Jafri H, Chavez-Bueno S, Ogra PL, McKinney L, Reed JL, Welliver RC Sr. 2007. Severe human lower respiratory tract illness caused by respiratory syncytial virus and influenza virus is characterized by the absence of pulmonary cytotoxic lymphocyte responses. J Infect Dis 195:1126–1136. doi: 10.1086/512615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liesman RM, Buchholz UJ, Luongo CL, Yang L, Proia AD, DeVincenzo JP, Collins PL, Pickles RJ. 2014. RSV-encoded NS2 promotes epithelial cell shedding and distal airway obstruction. J Clin Invest 124:2219–2233. doi: 10.1172/JCI72948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tregoning JS, Schwarze J. 2010. Respiratory viral infections in infants: causes, clinical symptoms, virology, and immunology. Clin Microbiol Rev 23:74–98. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00032-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zorc JJ, Hall CB. 2010. Bronchiolitis: recent evidence on diagnosis and management. Pediatrics 125:342–349. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garofalo RP, Patti J, Hintz KA, Hill V, Ogra PL, Welliver R. 2001. Macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha, and ot T-helper type 2 cytokines is associated with severe forms of bronchiolitis. J Infect Dis 184:393–399. doi: 10.1086/322788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garofalo R, Sabry M, Jamaluddin M, Yu RK, Casola A, Ogra PL, Brasier AR. 1996. Transcriptional activation of the interleukin-8 gene by respiratory syncytial virus infection in alveolar epithelial cells: nuclear translocation of the RelA transcription factor as a mechanism producing airway mucosal inflammation. J Virol 70:8773–8781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brasier AR, Tian B, Jamaluddin M, Kalita MK, Garofalo RP, Lu M. 2011. RelA Ser276 phosphorylation-coupled Lys310 acetylation controls transcriptional elongation of inflammatory cytokines in respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Virol 85:11752–11769. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05360-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian B, Zhang Y, Luxon BA, Garofalo RP, Casola A, Sinha M, Brasier AR. 2002. Identification of NF-B-dependent gene networks in respiratory syncytial virus-infected cells. J Virol 76:6800–6814. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6800-6814.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Luxon BA, Casola A, Garofalo RP, Jamaluddin M, Brasier AR. 2001. Expression of respiratory syncytial virus-induced chemokine gene networks in lower airway epithelial cells revealed by cDNA microarrays. J Virol 75:9044–9058. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.9044-9058.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu P, Jamaluddin M, Li K, Garofalo RP, Casola A, Brasier AR. 2007. Retinoic acid-inducible gene I mediates early antiviral response and Toll-like receptor 3 expression in respiratory syncytial virus-infected airway epithelial cells. J Virol 81:1401–1411. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01740-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bibeau-Poirier A, Servant MJ. 2008. Roles of ubiquitination in pattern-recognition receptors and type I interferon receptor signaling. Cytokine 43:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato H, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Uematsu S, Matsui K, Tsujimura T, Takeda K, Fujita T, Takeuchi O, Akira S. 2005. Cell type-specific involvement of RIG-I in antiviral response. Immunity 23:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawai T, Takahashi K, Sato S, Coban C, Kumar H, Kato H, Ishii KJ, Takeuchi O, Akira S. 2005. IPS-1, an adaptor triggering RIG-I- and Mda5-mediated type I interferon induction. Nat Immunol 6:981–988. doi: 10.1038/ni1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang C, Kolokoltsova OA, Yun NE, Seregin AV, Poussard AL, Walker AG, Brasier AR, Zhao Y, Tian B, de la Torre JC, Paessler S. 2012. Junín virus infection activates the type I interferon pathway in a RIG-I-dependent manner. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6:e1659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoneyama M, Fujita T. 2008. Structural mechanism of RNA recognition by the RIG-I-like receptors. Immunity 29:178–181. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yount JS, Gitlin L, Moran TM, Lopez CB. 2008. MDA5 participates in the detection of paramyxovirus infection and is essential for the early activation of dendritic cells in response to Sendai Virus defective interfering particles. J Immunol 180:4910–4918. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seth RB, Sun L, Ea CK, Chen ZJ. 2005. Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-kappaB and IRF 3. Cell 122:669–682. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cai X, Chen J, Xu H, Liu S, Jiang QX, Halfmann R, Chen ZJ. 2014. Prion-like polymerization underlies signal transduction in antiviral immune defense and inflammasome activation. Cell 156:1207–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grandvaux N, Servant MJ, ten Oever B, Sen GC, Balachandran S, Barber GN, Lin R, Hiscott J. 2002. Transcriptional profiling of interferon regulatory factor 3 target genes: direct involvement in the regulation of interferon-stimulated genes. J Virol 76:5532–5539. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5532-5539.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoggins JW, Rice CM. 2011. Interferon-stimulated genes and their antiviral effector functions. Curr Opin Virol 1:519–525. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadler AJ, Williams BR. 2008. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat Rev Immunol 8:559–568. doi: 10.1038/nri2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Der SD, Zhou A, Williams BR, Silverman RH. 1998. Identification of genes differentially regulated by interferon alpha, beta, or gamma using oligonucleotide arrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:15623–15628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith PL, Lombardi G, Foster GR. 2005. Type I interferons and the innate immune response–more than just antiviral cytokines. Mol Immunol 42:869–877. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas E, Gonzalez VD, Li Q, Modi AA, Chen W, Noureddin M, Rotman Y, Liang TJ. 2012. HCV infection induces a unique hepatic innate immune response associated with robust production of type III interferons. Gastroenterology 142:978–988. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider WM, Chevillotte MD, Rice CM. 2014. Interferon-stimulated genes: a complex web of host defenses. Annu Rev Immunol 32:513–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balachandran S, Beg AA. 2011. Defining emerging roles for NF-kappaB in antivirus responses: revisiting the interferon-beta enhanceosome paradigm. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002165. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Honda K, Yanai H, Takaoka A, Taniguchi T. 2005. Regulation of the type I IFN induction: a current view. Int Immunol 17:1367–1378. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu R, Moore PA, Pitha PM. 2002. Stimulation of IRF-7 gene expression by tumor necrosis factor alpha: requirement for NFkappa B transcription factor and gene accessibility. J Biol Chem 277:16592–16598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111440200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bertolusso R, Tian B, Zhao Y, Vergara L, Sabree A, Iwanaszko M, Lipniacki T, Brasier AR, Kimmel M. 2014. Dynamic cross talk model of the epithelial innate immune response to double-stranded RNA stimulation: coordinated dynamics emerging from cell-level noise. PLoS One 9:e93396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jamaluddin M, Tian B, Boldogh I, Garofalo RP, Brasier AR. 2009. Respiratory syncytial virus infection induces a reactive oxygen species-MSK1-phospho-Ser-276 RelA pathway required for cytokine expression. J Virol 83:10605–10615. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01090-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jamaluddin M, Wang S, Boldogh I, Tian B, Brasier AR. 2007. TNF-alpha-induced NF-kappaB/RelA Ser(276) phosphorylation and enhanceosome formation is mediated by an ROS-dependent PKAc pathway. Cell Signal 19:1419–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fang L, Choudhary S, Zhao Y, Edeh CB, Yang C, Boldogh I, Brasier AR. 2014. ATM regulates NF-kappaB-dependent immediate-early genes via RelA Ser 276 phosphorylation coupled to CDK9 promoter recruitment. Nucleic Acids Res 42:8416–8432. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu P, Lu M, Tian B, Li K, Garofalo RP, Prusak D, Wood TG, Brasier AR. 2009. Expression of an IKKgamma splice variant determines IRF3 and canonical NF-kappaB pathway utilization in ssRNA virus infection. PLoS One 4:e8079. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ueba O. 1978. Respiratory syncytial virus. I. Concentration and purification of the infectious virus. Acta Med Okayama 32:265–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foy E, Li K, Wang C, Sumpter R Jr, Ikeda M, Lemon SM, Gale M Jr. 2003. Regulation of interferon regulatory factor-3 by the hepatitis C virus serine protease. Science 300:1145–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.1082604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choudhary S, Boldogh S, Garofalo R, Jamaluddin M, Brasier AR. 2005. Respiratory syncytial virus influences NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression through a novel pathway involving MAP3K14/NIK expression and nuclear complex formation with NF-kappaB2. J Virol 79:8948–8959. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.8948-8959.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tian B, Zhao Y, Kalita M, Edeh CB, Paessler S, Casola A, Teng MN, Garofalo RP, Brasier AR. 2013. CDK9-dependent transcriptional elongation in the innate interferon-stimulated gene response to respiratory syncytial virus infection in airway epithelial cells. J Virol 87:7075–7092. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03399-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nowak DE, Tian B, Brasier AR. 2005. Two-step cross-linking method for identification of NF-kappaB gene network by chromatin immunoprecipitation. Biotechniques 39:715–725. doi: 10.2144/000112014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tian B, Yang J, Brasier AR. 2012. Two-step cross-linking for analysis of protein-chromatin interactions. Methods Mol Biol 809:105–120. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-376-9_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foster KA, Oster CG, Mayer MM, Avery ML, Audus KL. 1998. Characterization of the A549 cell line as a type II pulmonary epithelial cell model for drug metabolism. Exp Cell Res 243:359–366. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jamaluddin M, Wang S, Garofalo RP, Elliott T, Casola A, Baron S, Brasier AR. 2001. IFN-beta mediates coordinate expression of antigen-processing genes in RSV-infected pulmonary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280:L248–L257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lau A, Swinbank KM, Ahmed PS, Taylor DL, Jackson SP, Smith GC, O'Connor MJ. 2005. Suppression of HIV-1 infection by a small molecule inhibitor of the ATM kinase. Nat Cell Biol 7:493–500. doi: 10.1038/ncb1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. 2003. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature 421:499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature01368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu ZH, Shi Y, Tibbetts RS, Miyamoto S. 2006. Molecular linkage between the kinase ATM and NF-kappaB signaling in response to genotoxic stimuli. Science 311:1141–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.1121513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Attikum H, Gasser SM. 2009. Crosstalk between histone modifications during the DNA damage response. Trends Cell Biol 19:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mah LJ, El-Osta A, Karagiannis TC. 2010. gammaH2AX: a sensitive molecular marker of DNA damage and repair. Leukemia 24:679–686. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ba X, Bacsi A, Luo J, Aguilera-Aguirre L, Zeng X, Radak Z, Brasier AR, Boldogh I. 2014. 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase-1 augments proinflammatory gene expression by facilitating the recruitment of site-specific transcription factors. J Immunol 192:2384–2394. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nowak DE, Tian B, Jamaluddin M, Boldogh I, Vergara LA, Choudhary S, Brasier AR. 2008. RelA Ser276 phosphorylation is required for activation of a subset of NF-kappaB-dependent genes by recruiting cyclin-dependent kinase 9/cyclin T1 complexes. Mol Cell Biol 28:3623–3638. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01152-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haeberle HA, Takizawa R, Casola A, Brasier AR, Dieterich HJ, Van Rooijen N, Gatalica Z, Garofalo RP. 2002. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced activation of nuclear factor-kappaB in the lung involves alveolar macrophages and toll-like receptor 4-dependent pathways. J Infect Dis 186:1199–1206. doi: 10.1086/344644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hosakote YM, Liu T, Castro SM, Garofalo RP, Casola A. 2009. Respiratory syncytial virus induces oxidative stress by modulating antioxidant enzymes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 41:348–357. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0330OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lilley CE, Schwartz RA, Weitzman MD. 2007. Using or abusing: viruses and the cellular DNA damage response. Trends Microbiol 15:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rohaly G, Korf K, Dehde S, Dornreiter I. 2010. Simian virus 40 activates ATR-Delta p53 signaling to override cell cycle and DNA replication control. J Virol 84:10727–10747. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00122-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hein J, Boichuk S, Wu J, Cheng Y, Freire R, Jat PS, Roberts TM, Gjoerup OV. 2009. Simian virus 40 large T antigen disrupts genome integrity and activates a DNA damage response via Bub1 binding. J Virol 83:117–127. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01515-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bian T, Gibbs JD, Orvell C, Imani F. 2012. Respiratory syncytial virus matrix protein induces lung epithelial cell cycle arrest through a p53 dependent pathway. PLoS One 7:e38052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reference deleted.

- 63.Lee JH, Paull TT. 2007. Activation and regulation of ATM kinase activity in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Oncogene 26:7741–7748. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jacobs JL, Coyne CB. 2013. Mechanisms of MAVS regulation at the mitochondrial membrane. J Mol Biol 425:5009–5019. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guo Z, Kozlov S, Lavin MF, Person MD, Paull TT. 2010. ATM activation by oxidative stress. Science 330:517–521. doi: 10.1126/science.1192912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stilmann M, Hinz M, Arslan SC, Zimmer A, Schreiber V, Scheidereit C. 2009. A nuclear poly(ADP-ribose)-dependent signalosome confers DNA damage-induced IkappaB kinase activation. Mol Cell 36:365–378. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brasier AR. 2008. The NF-k B signaling network: insights from systems approaches, p 119–135 InBrasier AR, Lemon SM, Garcia-Sastre A (ed), Cellular signaling and innate immune responses to RNA virus infections. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Smogorzewska A, McDonald ER III, Hurov KE, Luo J, Bakalarski CE, Zhao Z, Solimini N, Lerenthal Y, Shiloh Y, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ. 2007. ATM and ATR substrate analysis reveals extensive protein networks responsive to DNA damage. Science 316:1160–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.1140321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ning S, Huye LE, Pagano JS. 2005. Regulation of the transcriptional activity of the IRF7 promoter by a pathway independent of interferon signaling. J Biol Chem 280:12262–12270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hou F, Sun L, Zheng H, Skaug B, Jiang QX, Chen ZJ. 2011. MAVS forms functional prion-like aggregates to activate and propagate antiviral innate immune response. Cell 146:448–461. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Basagoudanavar SH, Thapa RJ, Nogusa S, Wang J, Beg AA, Balachandran S. 2011. Distinct roles for the NF-kappa B RelA subunit during antiviral innate immune responses. J Virol 85:2599–2610. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02213-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gack MU, Shin YC, Joo CH, Urano T, Liang C, Sun L, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Chen Z, Inoue S, Jung JU. 2007. TRIM25 RING-finger E3 ubiquitin ligase is essential for RIG-I-mediated antiviral activity. Nature 446:916–920. doi: 10.1038/nature05732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]