Abstract

During the HIV-1 replicative cycle, the gp160 envelope is processed in the secretory pathway to mature into the gp41 and gp120 subunits. Misfolded proteins located within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) are proteasomally degraded through the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway, a quality control system operating in this compartment. Here, we exploited the ERAD pathway to induce the degradation of gp160 during viral production, thus leading to the release of gp120-depleted viral particles.

TEXT

The precursor of the viral envelope, gp160, undergoes extensive posttranslational modification in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and is subsequently cleaved into two subunits, gp120 and gp41, within the Golgi apparatus. The processed Env subunits then reach the plasma membrane, where they are incorporated into the budding viral particles (1).

Here, we present a novel strategy to reduce HIV-1 infectivity through the depletion of gp120 from viral particles. This approach is based on gp160 degradation during viral production obtained by using the targeted ER-associated degradation (TED) approach. This recently developed technique exploits the ER-associated degradation pathway (ERAD) machinery to promote specific downregulation of target proteins trafficking through the secretory pathway (2). TED uses chimeric molecules termed “degradins” that are characterized by two functional moieties: a target recognition moiety and a degradation-inducing moiety composed of the C-terminal fragment (amino acids [aa] 402 to 773) of the cellular ER-resident protein SEL1L. This protein is involved in the ERAD pathway by selecting misfolded proteins for retrotranslocation from the ER lumen to the cytosol for proteasomal degradation (3). SEL1L chimeras designed against selected targets have been demonstrated to specifically force the interaction of the target protein with the retrotranslocation machinery, leading to the export of the protein from the ER and its subsequent degradation in the cytosol (2).

To obtain gp160-specific degradins, we prepared SEL1L chimeras containing different target recognition moieties directed against various epitopes of HIV-1 gp160. We used three single-chain antibody fragments (scFv) derived from monoclonal antibodies (MAbs): Chessie1339, obtained from the anti-gp160 hybridoma Chessie 13-39.1 (4), to produce the 1339-SEL1L degradin; and VRC01 and VRC03, derived from two broad neutralizing MAbs directed toward the CD4 binding site of gp120 (5), to produce the VRC01-SEL1L and VRC03-SEL1L degradins, respectively. A general scheme of degradin design is reported in Fig. 1A.

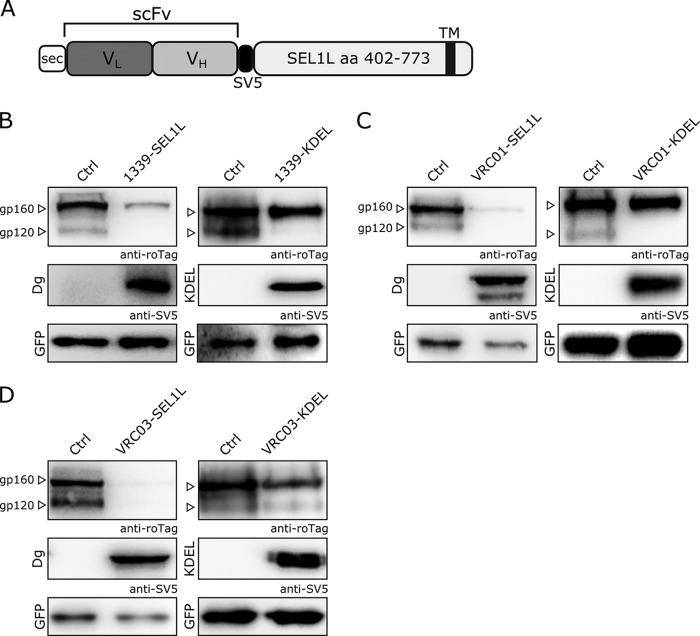

FIG 1.

gp160 degradation by specific degradins. (A) Schematic structure of anti-gp160 degradins. The target recognition moiety (scFv) is fused to the C-terminal portion of SEL1L (aa 402 to 773). The V5 tag is used for protein immunodetection. (B to D) gp160 intracellular levels, analyzed by Western blotting, on cell extracts from 293T cells cotransfected with gp160 and the degradin constructs 1339-SEL1L (B), VRC01-SEL1L (C), and VRC03-SEL1L (D) (right) or the corresponding KDEL-containing constructs (B to D, left). A GFP expression construct was used as a transfection and loading control. gp160 was detected with an anti-roTag antibody, degradins with an anti-V5 antibody.

We next tested the efficacy of the anti-gp160 degradins in 293T cells coexpressing the SEL-1L chimeras with a codon-optimized gp160. In these experiments, gp160 is expressed from a construct containing the codon-optimized sequence for gp120 (isolate JRFL, clade B) from the pSyngp120 plasmid (6) in frame with the optimized sequence for gp41 derived by gene synthesis from the same isolate. In addition, the N terminus of gp160 was modified by substituting the signal peptide for ER import and by adding the 10-amino-acid-long roTag for protein immunodetection (7). The gp160/degradin coexpression experiments showed that all degradins blocked the maturation of gp160, as indicated by the lack of formation of the band corresponding to the cleaved gp120 subunit (Fig. 1B to D, left). As a control, SEL-1L chimeras were produced by fusing the same gp160 target recognition moieties to the short ER-retaining C-terminal amino acid sequence KDEL, thus inducing gp160 retention in the ER but not its active degradation. Similarly to the gp160-specific degradins, the KDEL control chimeras showed no formation of matured gp120, as expected (Fig. 1B to D, right). Notably, all the tested anti-gp160 degradins significantly reduced the intracellular levels of gp160 (between 80% and 90% of the control, as measured by densitometry), while the corresponding control KDEL chimeras showed no intracellular gp160 reduction (compare Fig. 1B to D, top). These results suggest that the degradins induce gp160 envelope glycoprotein retention in the ER and its subsequent degradation through the ERAD pathway, as shown in previous work on different protein targets (2).

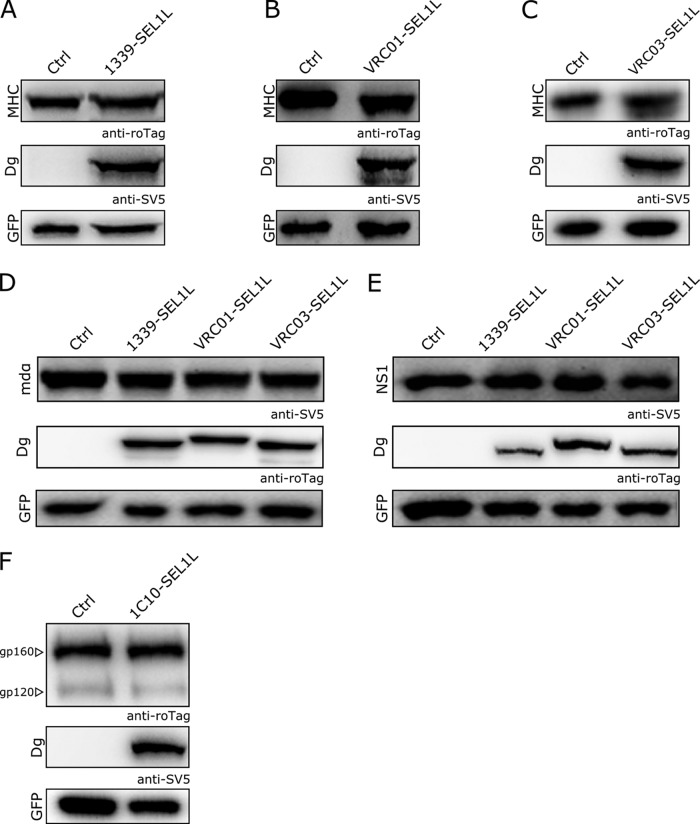

The specificity of gp160 degradation mediated by the degradins was validated by using at least three unrelated proteins trafficking through the ER: (i) the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I alpha chain (MHC-I), (ii) the nonsecreted antibody light-chain NS1 (8), and (iii) a membrane-bound form of the alpha chain of the human high-affinity IgE receptor (mdα) (2). As shown in Fig. 2A to E, anti-gp160 degradins did not modulate the level of expression of any of these unrelated substrates following their coexpression in 293T cells. To further test TED specificity, an off-target degradin containing an irrelevant scFv target recognition moiety (1C10-SEL1L [9]) was coexpressed with gp160 in 293T cells, showing no detectable variation of the intracellular levels of both gp160 and its maturation product, gp120 (Fig. 2F).

FIG 2.

Specificity of the anti-gp160 degradins. Expression levels of irrelevant targets in the presence of anti-gp160 degradins: (A to C) MHC class I alpha chain; (D) NS1-nonsecreted antibody light chain; and (E) a transmembrane version of the alpha chain of the human high-affinity IgE receptor as a fusion product of the receptor domain with the immunoglobulin γCH3 in its membrane-bound form (mdα). (F) WB of gp160 in extracts of cells cotransfected with the irrelevant degradin 1C10-SEL1L. A GFP expression construct was used as a transfection and loading control. Immunoblots were performed with the indicated antibodies.

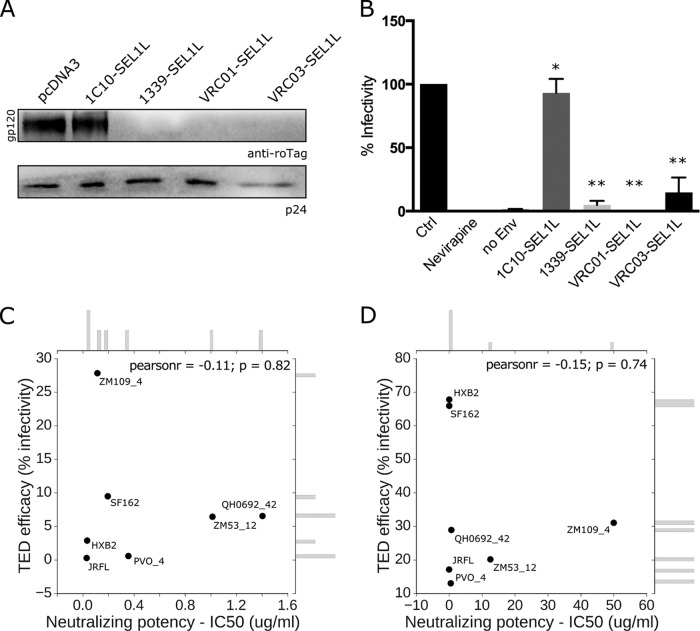

The amount of Env incorporated in neo-synthetized virions was then measured through Western blot analysis of concentrated viral particles produced in 293T cells expressing Env-targeting degradins. As shown in Fig. 3A, virions purified from these cells showed undetectable levels of gp120 compared to those of virions produced in the presence of the control degradin (1C10-SEL1L). In addition, unmodified levels of CA/p24 indicated no major alteration of viral protein content.

FIG 3.

Degradins impair HIV-1 infectivity. (A) Western blot of viral supernatants from degradin-expressing 293T cells. gp160 was detected with anti-roTag and p24 with MAb AG3.0. (B) Luciferase activity (normalized for total protein concentration) was measured at 48 h postinfection from extracts of CD4+ CCR5+ HeLa cells infected with HIV-1 viral vectors produced in degradin-expressing 293T cells (**, P < 0.01; *, P = 0.96, Student's paired t test). Correlation plot between TED efficacy and neutralizing potency (IC50) for the VRC01 (C) and VRC03 (D) MAbs. The insets report the marginal distribution frequency of the two correlated quantities.

To functionally test the activity of the anti-gp160 degradins on HIV-1 infectivity, the luciferase reporter clone NL4-3.Luc.R−.E− (Env−\Vpr−\Nef−) (10) and the JRFL codon-optimized Env expression plasmids were used to produce viral particles in the presence of all the above-described degradins and then tested for infectivity. HeLa cells stably expressing CD4/CCR5 (11) were infected with supernatants containing equal amounts of viral particles as measured by retrotranscriptase units (12) (corresponding to 30 ng of p24) and tested for luciferase activity after 48 h. All the gp160-specific degradins showed a strong reduction in viral infectivity (between 80% and nearly 100% inhibition), while no significant modulation was observed with the irrelevant degradin 1C10-SEL1L (Fig. 3B). To further assess the ability of TED to block viral infectivity, we tested its efficacy against a panel of Env, including four from clade B and two from clade C HIV-1 isolates. Similarly to JRFL, gp160-specific degradins induced a strong reduction of infectivity of the differentially pseudotyped viruses, producing a variable efficacy ranging from 40% up to an almost complete viral inhibition (Table 1). Interestingly, by plotting the neutralizing potency of the VRC01 and VRC03 antibodies (as reported from the CATNAP resource, HIV Databases, Los Alamos National Laboratory) against the efficacy of TED toward the same envelope, no correlation was found between the two quantities, as demonstrated by a Pearson's coefficient ranging from −0.11 to −0.15 (Fig. 3C and D). This is probably a result of the differential epitope exposure in the ER during maturation compared to the same epitope located on released viral particles. These data reveal that in comparison with alternative approaches, TED works with a broader spectrum of antibodies, including those that are not neutralizing. In addition, this tool allows designing degradins against conserved epitopes on gp160 that are normally inefficient for immune neutralization. Finally, an advantage offered by TED is its adaptability to multiple degradins targeting different epitopes, thus increasing its overall efficacy and preventing the evolution of escape mutants.

TABLE 1.

TED efficacy on gp160 from clade B and C HIV-1 isolates

| Degradin | Luciferase activitya |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRUb | HXB2b | SF162b | PVO, clone 4b | QH0692, clone 42b | ZM53 M.PB12c | ZM109F.PB4c | |

| 1C10-SEL1L | 158 ± 4 | 170 ± 60 | 157 ± 3 | 85 ± 11 | 70 ± 20 | 85 ± 2 | 94 ± 5 |

| 1339-SEL1L | 7 ± 2 | 6.44 ± 0.09 | 30.5 ± 0.20 | 2 ± 2 | 30 ± 10 | 9 ± 3 | 9.3 ± 0.6 |

| VRC01-SEL1L | 10 ± 3 | 3 ± 1 | 9 ± 8 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 7 ± 2 | 6 ± 3 | 28 ± 13 |

| VRC03-SEL1L | 11.0 ± 0.8 | 68 ± 4 | 65 ± 8 | 13 ± 3 | 28.94 ± 0.05 | 20 ± 2 | 31 ± 4 |

| Nevirapined | 0.229 ± 0.002 | 6 ± 2 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 0.229 ± 0.002 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 5.77 ± 0.02 |

Mean percentage ± standard deviation of luciferase activity normalized for total protein concentration.

Clade B.

Clade C.

Added during infection at a final concentration of 10 μM.

To reduce viral infectivity, several molecular strategies have been developed to target intracellular HIV-1 proteins, including Env (13). By the exploitation of the Env-CD4 binding affinity occurring in the ER and by using anti-gp160 intracellular single-chain antibodies, interference with gp160 maturation and trafficking was successfully obtained (14–21). These former approaches were based mainly on Env retention in the ER through classical ER-retaining signals.

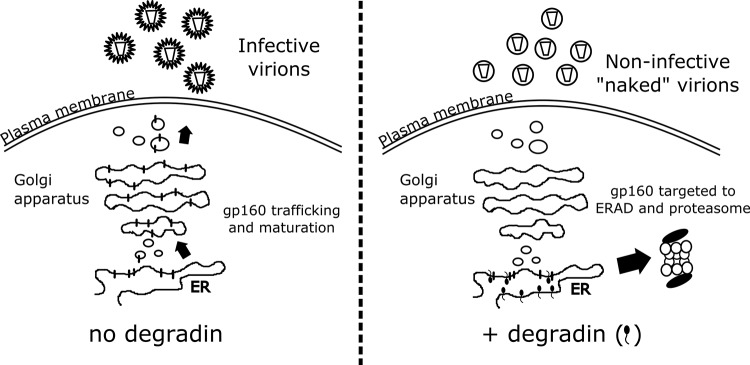

Despite these initial encouraging results in support of molecular strategies targeting Env maturation to block viral infectivity, the toxicity generated by Env accumulation in the ER remains a concern. To address this issue, we used the TED approach to specifically induce gp160-active degradation through the ERAD pathway (schematized in Fig. 4). In fact, by inducing gp160 degradation, our technique provides a great advantage by overcoming toxic effects due to ER overload of retained Env protein (22–24). Notably, it has been previously demonstrated that degradins do not elicit ER stress (2). Finally, due to the essential role of the proteasome in antigen presentation, it is possible to speculate that cells expressing gp160-specific degradins, thanks to its increased proteasomal degradation, will be more prone to load gp160-derived peptides on their MHC class I molecules, thus boosting the immune response against the virus.

FIG 4.

Schematic representation of the anti-gp160 degradins' mode of action. In the presence of the gp160-specific degradins, the envelope precursor is directed to proteasomal degradation, and the viral particles produced are Env deprived and noninfectious.

In conclusion, our degradin-based anti-HIV-1 approach may provide a novel molecular strategy aimed at decreasing HIV-1 infectivity through Env depletion in virus-producing cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: Chessie 13-39.1, pSyn-gp120-JRFL, the VRC01 and VRC03 light and heavy chains, the HIV-1 p24 (AG3.0) MAb, pNL4-3.Luc.R−.E−, and Env plasmids QH0692-clone 42, PVO-clone 4, ZM53M.PB12, ZM109F.PB4, and SF162.

We thank Gianluca Petris and Daniele Arosio for reading the manuscript and for useful suggestions.

This work was supported by the ISS Italian AIDS Program (grant 40H90) and by the Provincia Autonoma di Trento (COFUND Project, Team 2009–Incoming).

REFERENCES

- 1.Checkley MA, Luttge BG, Freed EO. 2011. HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein biosynthesis, trafficking, and incorporation. J Mol Biol 410:582–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vecchi L, Petris G, Bestagno M, Burrone OR. 2012. Selective targeting of proteins within secretory pathway for endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. J Biol Chem 287:20007–20015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.355107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller B, Klemm EJ, Spooner E, Claessen JH, Ploegh HL. 2008. SEL1L nucleates a protein complex required for dislocation of misfolded glycoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:12325–12330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805371105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abacioglu YH, Fouts TR, Laman JD, Claassen E, Pincus SH, Moore JP, Roby CA, Kamin-Lewis R, Lewis GK. 1994. Epitope mapping and topology of baculovirus-expressed HIV-1 gp160 determined with a panel of murine monoclonal antibodies. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 10:371–381. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu X, Yang Z-Y, Li Y, Hogerkorp C-M, Schief WR, Seaman MS, Zhou T, Schmidt SD, Wu L, Xu L, Longo NS, McKee K, O'Dell S, Louder MK, Wycuff DL, Feng Y, Nason M, Doria-Rose N, Connors M, Kwong PD, Roederer M, Wyatt RT, Nabel GJ, Mascola JR. 2010. Rational design of envelope identifies broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to HIV-1. Science 329:856–861. doi: 10.1126/science.1187659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas J, Park EC, Seed B. 1996. Codon usage limitation in the expression of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein. Curr Biol 6:315–324. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00482-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petris G, Bestagno M, Arnoldi F, Burrone OR. 2014. New tags for recombinant protein detection and O-glycosylation reporters. PLoS One 9:e96700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dul JL, Burrone OR, Argon Y. 1992. A conditional secretory mutant in an Ig L chain is caused by replacement of tyrosine/phenylalanine 87 with histidine. J Immunol 149:1927–1933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn SJ, Ward RL, McNeal MM, Cross TL, Greenberg HB. 1993. Identification of a new neutralization epitope on VP7 of human serotype 2 rotavirus and evidence for electropherotype differences caused by single nucleotide substitutions. Virology 197:397–404. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He J, Choe S, Walker R, Di Marzio P, Morgan DO, Landau NR. 1995. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R (Vpr) arrests cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle by inhibiting p34cdc2 activity. J Virol 69:6705–6711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verrier FC, Charneau P, Altmeyer R, Laurent S, Borman AM, Girard M. 1997. Antibodies to several conformation-dependent epitopes of gp120/gp41 inhibit CCR-5-dependent cell-to-cell fusion mediated by the native envelope glycoprotein of a primary macrophage-tropic HIV-1 isolate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:9326–9331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pizzato M, Erlwein O, Bonsall D, Kaye S, Muir D, McClure MO. 2009. A one-step SYBR green I-based product-enhanced reverse transcriptase assay for the quantitation of retroviruses in cell culture supernatants. J Virol Methods 156:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nielsen MH, Pedersen FS, Kjems J. 2005. Molecular strategies to inhibit HIV-1 replication. Retrovirology 2:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buonocore L, Rose J. 1990. Prevention of HIV-1 glycoprotein transport by soluble CD4 retained in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature 345:625–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buonocore L, Rose JK. 1993. Blockade of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 production in CD4+ T cells by an intracellular CD4 expressed under control of the viral long terminal repeat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:2695–2699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Degar S, Johnson J, Boritz E, Rose J. 1996. Replication of primary HIV-1 isolates is inhibited in PM1 cells expressing sCD4-KDEL. Virology 429:424–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.San José E, Muñoz-Fernández MA, Alarcón B. 1998. Retroviral vector-mediated expression in primary human T cells of an endoplasmic reticulum-retained CD4 chimera inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type-1 replication. Hum Gene Ther 9:1345–1357. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.9-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marasco WA, Haseltine WA, Chen SY. 1993. Design, intracellular expression, and activity of a human anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 single-chain antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:7889–7893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou P, Goldstein S, Devadas K, Tewari D, Notkins AL. 1998. Cells transfected with a non-neutralizing antibody gene are resistant to HIV infection: targeting the endoplasmic reticulum and trans-Golgi network. J Immunol 160:1489–1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu F, Kumar M, Ma Q, Duval M, Kuhrt D, Junghans R, Posner M, Cavacini L. 2005. Human single-chain antibodies inhibit replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 21:876–881. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen SY, Bagley J, Marasco WA. 1994. Intracellular antibodies as a new class of therapeutic molecules for gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther 5:595–601. doi: 10.1089/hum.1994.5.5-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ron D, Walter P. 2007. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishitoh H, Matsuzawa A, Tobiume K, Saegusa K, Takeda K, Inoue K, Hori S, Kakizuka A, Ichijo H. 2002. ASK1 is essential for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell death triggered by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Genes Dev 16:1345–1355. doi: 10.1101/gad.992302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leitman J, Ulrich Hartl F, Lederkremer GZ. 2013. Soluble forms of polyQ-expanded huntingtin rather than large aggregates cause endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Commun 4:2753. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]