Abstract

Clostridium difficile infection causes serious diarrheal disease. Although several drugs are available for treatment, including vancomycin, recurrences remain a problem. LFF571 is a semisynthetic thiopeptide with potency against C. difficile in vitro. In this phase 2 exploratory study, we compared the safety and efficacy (based on a noninferiority analysis) of LFF571 to those of vancomycin used in adults with primary episodes or first recurrences of moderate C. difficile infection. Patients were randomized to receive 200 mg of LFF571 or 125 mg of vancomycin four times daily for 10 days. The primary endpoint was the proportion of clinical cures at the end of therapy in the per-protocol population. Secondary endpoints included clinical cures at the end of therapy in the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population, the time to diarrhea resolution, and the recurrence rate. Seventy-two patients were randomized, with 46 assigned to receive LFF571. Based on the protocol-specified definition, the rate of clinical cure for LFF571 (90.6%) was noninferior to that of vancomycin (78.3%). The 30-day sustained cure rates for LFF571 and vancomycin were 56.7% and 65.0%, respectively, in the per-protocol population and 58.7% and 60.0%, respectively, in the modified intent-to-treat population. Using toxin-confirmed cases only, the recurrence rates were lower for LFF571 (19% versus 25% for vancomycin in the per-protocol population). LFF571 was generally safe and well tolerated. The incidence of adverse events (AEs) was higher for LFF571 (76.1% versus 69.2% for vancomycin), although more AEs in the vancomycin group were suspected to be related to the study drug (38.5% versus 32.6% for LFF571). One patient receiving LFF571 discontinued the study due to an AE. (This study has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under registration no. NCT01232595.)

INTRODUCTION

Clostridium difficile infection is a potentially serious disease, with symptoms ranging from mild diarrhea to fatal complications, such as pseudomembranous colitis, toxic megacolon, bowel perforation, and sepsis, in approximately 5% of cases (1). Over the past decade, the severity of C. difficile infections has increased. This is due in part to the emergence of a more virulent C. difficile strain, NAP1/BI/027, which has caused outbreaks in the United States, Canada, and Europe since the early 2000s (2, 3). The current treatment regimens for C. difficile infection include therapy with oral vancomycin, metronidazole, or fidaxomicin. The initial response rates during and immediately after therapy are similar for all three agents in mild cases. Unfortunately, recurrent infection following successful initial treatment is a problem. Compared with oral vancomycin, the rate of recurrence can be lower for fidaxomicin and may be higher for metronidazole, although recently published data from two phase 3 studies revealed that the rates were similar for vancomycin- and metronidazole-treated patients (4–6). The recurrence rates associated with fidaxomicin appear to be reduced only in patients infected with strains other than NAP1/BI/027 (4, 5).

LFF571 is a novel thiopeptide antibiotic (7) derived from the natural metabolite GE2270 A (8). The compound inhibits prokaryotic translation by targeting elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu) (9). The data from three independent surveillance studies of LFF571 activity against C. difficile demonstrated consistent in vitro potency, with all strains inhibited by ≤0.5 μg/ml LFF571. A determination of the concentration at which 90% of the strains were inhibited (MIC90) indicated that LFF571 (MIC90, 0.25 μg/ml) was 8-fold more potent than vancomycin and metronidazole and 2-fold more potent than fidaxomicin against 50 clinical strains of C. difficile (10). When tested against 103 recent toxin-positive C. difficile isolates from geographically diverse locations within the United States, LFF571 was equipotent to metronidazole (MIC90, 0.5 μg/ml) and 2-fold more active than vancomycin (MIC90, 1 μg/ml) (11). Further testing against 398 clinical isolates from European hospitals indicated that LFF571 (MIC90, 0.25 μg/ml) was 2- to 4-fold more active than vancomycin and metronidazole and equal in potency to fidaxomicin (12). Studies of LFF571 in the Golden Syrian hamster model of C. difficile infection showed that oral administration of the drug once daily at 5 mg/kg of body weight decreased the risk of death by 69% (P = 0.0022) compared with 20 mg/kg of vancomycin (13). In healthy volunteers, single and multiple doses of LFF571 are safe and well tolerated, with limited systemic exposure (14). In this study (registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under registration no. NCT01232595), we evaluated the safety and efficacy (as well as pharmacokinetics [15]) of LFF571 compared to those of vancomycin inpatients with C. difficile infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Eligible patients were males and females between 18 and 90 years of age who were diagnosed with a primary episode or first recurrence of moderately severe C. difficile infections. Moderately severe infections were defined by the presence of ≥3 to ≤12 liquid or unformed stools in the 24 h prior to enrollment, positive C. difficile toxin A/B or B assay result, and one or more of the following in the 24 h prior to enrollment: abdominal pain, peripheral blood leukocyte count of >10 × 109/liter but <30 × 109/liter, or fever. The patients were required to have a positive C. difficile toxin A/B or B assay result within 48 h prior to enrollment in the study, although patients with an initial recurrence could be enrolled prior to obtaining a positive toxin result as long as stool samples were collected before the start of treatment. Recurrence for enrollment was defined by the occurrence of diarrhea within 60 days after an initial successful course of treatment had resulted in no C. difficile-associated symptoms for ≥1 week. The eligible patients could have received ≤24 h of therapy effective for C. difficile infection (≤4 oral doses of vancomycin or ≤3 oral or intravenous doses of metronidazole [fidaxomicin was not available during the enrollment period]) in the 3 days preceding enrollment. The eligible patients were not expected to require >72 h of antibiotics for other infections during the treatment period.

Patients were excluded from the study if the C. difficile infection was considered to be more severe, as defined by the presence of any of the following: hemodynamic instability, toxic megacolon, >12 liquid or unformed stools per day, peritonitis, ileus, elevated serum lactate levels, neutropenia, or clinically significant immunosuppression. Chemotherapy was allowed if it was not expected to result in neutropenia. Other exclusion criteria included severe underlying disease with expected survival of <3 months, more than one prior episode of C. difficile infection within the prior 3 months, and other causes of diarrhea present.

Study design.

This phase 2 exploratory study employed a multicenter, randomized, evaluator-blind, active-controlled, and parallel-group design to assess the safety and efficacy of LFF571. It consisted of a 7-day screening/baseline period, a treatment period, and a final evaluation 30 days after the completion of treatment. The patients could be enrolled as outpatients or as inpatients if they were already hospitalized. Toxin detection was performed on fresh stool samples collected prior to treatment at the local laboratory (using a health authority-approved method) and at the central laboratory, which detected toxin B (tcdB) by PCR. Additional samples were collected and went to the central laboratory for patients who were assessed as treatment failures, who developed a recurrence, or who withdrew from the study for any reason. Patients were randomized (initially 1:1 and then 5:1) to receive 200 mg of LFF571 (two 100-mg capsules) or 125 mg of vancomycin (one 125-mg capsule); each drug was administered orally, without regard to food intake, four times daily (QID) for a total of 40 doses. Site-specific allocation cards were used to randomize the patients. The randomization scheme was changed to minimize the number of LFF571-treated patients needed for a valid assessment of the primary outcome in this exploratory study.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and current good clinical practice. The protocol and amendments were approved by institutional review boards, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Assessments and definitions.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of clinical cures 1 to 3 days after the end of therapy. Clinical cure was defined as the resolution or improvement of the C. difficile infection such that additional therapy was not needed. Patients considered to be clinically cured had to have had two consecutive days with an absence of severe abdominal pain or fever, as well as <3 nonliquid stools per day. Clinical improvement was defined as the resolution or improvement of the C. difficile infection such that additional therapeutic intervention was not needed but the patient did not meet all the criteria of a clinical cure. In this exploratory study, clinical failure was defined based either on clinical criteria only (used for analysis of the primary endpoint) or on clinical criteria confirmed by toxin detection. The clinical definition used to define failure was insufficient resolution or worsening of C. difficile symptoms such that additional therapy was needed. Clinical indeterminates were patients who did not meet any of the above definitions. At the end-of-study visit, patients could also be classified as having a clinical recurrence, which was defined as the recurrence of symptoms and signs of C. difficile infection such that the patient had ≥3 liquid or unformed stools per day and additional therapy was needed.

Safety assessments consisted of the collection of all adverse events and regular monitoring of hematology, blood chemistry, and urine laboratory results, as well as regular assessments of vital signs and physical condition.

The safety population included all randomized patients who received at least one dose of the study drug. The modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population included all patients in the safety population with a documented C. difficile infection at baseline. The per-protocol population included all patients in the mITT population who were ≥80% compliant and for whom efficacy could be adequately assessed.

Statistical methods.

For the primary efficacy analysis, the posterior probability that the difference in the clinical cure rates 1 to 3 days after the end of therapy between the LFF571- and vancomycin-treated patients in the per-protocol population is above −20% was calculated. The noninferiority of LFF571 to vancomycin therapy was to be claimed if the interval excluded an absolute difference of −20%; this value was deemed adequate to make a decision if the observed efficacy outcome was sufficient to consider proceeding with subsequent confirmatory studies. The analysis used a noninformative prior probability distribution for the clinical cure rate for patients treated with LFF571. For the clinical cure rate associated with vancomycin therapy, an informative prior probability distribution derived from historical data was used. When the per-protocol population reached 25 LFF571-treated patients and if the true clinical cure rate associated with LFF571 treatment was ≥85% and equivalent to or better than the rate associated with vancomycin treatment, the probability of meeting the primary endpoint was calculated to be ≥80%.

Secondary analyses included clinical cures at end of therapy in the mITT population, time to diarrhea resolution, and recurrence rate. The survival analyses were done on the time to diarrhea resolution in the subset of subjects who were assessed as being clinically cured. Kaplan-Meier plots and the log rank test were used to investigate the differences between the treatment groups. None of the statistical methods for the other secondary and exploratory analyses were prespecified, including the analyses of potential confounding factors. A chi-square test was used to determine if potential confounding factors were associated with the clinical outcome or treatment group at the end-of-therapy visit in the mITT population.

RESULTS

Patients.

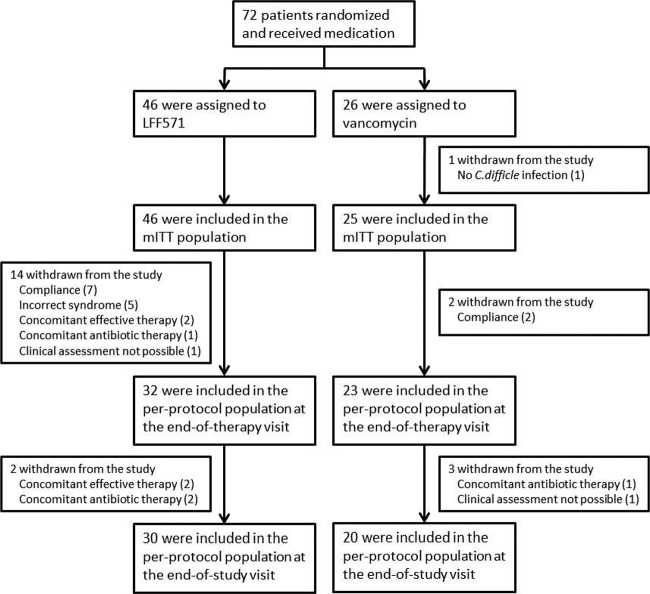

The study was conducted from January 2011 to January 2012. A total of 72 patients were enrolled and randomized, with 46 assigned to receive LFF571 and 26 to receive vancomycin (Fig. 1). The majority of patients (89.1% in the LFF571 group and 88.5% in the vancomycin group) completed the study, with two patients lost to follow-up, three withdrawn for administrative reasons, and one patient discontinued due to an adverse event. Only one patient, who had a suspected first recurrence and received vancomycin, did not have a confirmed C. difficile infection and was excluded from the mITT population; this population included a total of 71 patients (46 in the LFF571 group and 25 in the vancomycin group). The per-protocol population consisted of 55 patients at the end-of-therapy visit (32 in the LFF571 group and 23 in the vancomycin group) and 50 patients at the end-of-study visit (30 in the LFF571 group and 20 in the vancomycin group). All randomized patients were included in the safety analyses.

FIG 1.

Patient enrollment and disposition. Shown are the reasons why patients were excluded from the per-protocol and modified intent-to-treat (mITT) populations. The rates of recurrence at the end-of-study visit used a subset of the per-protocol or mITT populations, patients who were assessed as being clinically cured or improved at the end-of-therapy visit. Two LFF571-treated patients were excluded from the end-of-therapy and end-of-study per-protocol populations for two reasons.

The baseline characteristics were similar between the patients randomized to receive LFF571 and vancomycin (Table 1). However, more patients with an initial relapse or severe clinical symptoms received LFF571, while more patients who had been given prior C. difficile therapy or were infected with the NAP1/BI/027 strain received vancomycin. For assessing the severity at baseline, severe C. difficile infections were defined as ≥10 unformed bowel movements per day or a white blood cell count of >15.0 × 109/liter, similar to the definition used in the fidaxomicin development program (4). The population was overweight, with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 29.26 kg/m2.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristicsa

| Characteristic | LFF571 (n = 46) | Vancomycin (n = 26) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) (yr) | 59.8 ± 18.3 | 54.9 ± 23.9 |

| Male sex | 17 (37.0) | 8 (30.8) |

| Predominant race | ||

| Caucasian | 44 (95.7) | 23 (88.5) |

| Black | 1 (2.2) | 3 (11.5) |

| Asian | 1 (2.2) | 0 |

| Prior therapy with: | ||

| Metronidazole | 13 (28.3) | 12 (48.0) |

| Vancomycin | 2 (4.3) | 0 |

| Severe C. difficile infectionb | 11 (23.9) | 3 (12.0) |

| Previous episode of C. difficile infectionc | 13 (28.3) | 4 (16.0) |

| NAP1 C. difficile strainc | 9 (19.6) | 8 (32.0) |

Values are no. (%), unless otherwise noted. The baseline characteristics are for the safety population, unless otherwise noted.

Severe infection was defined as ≥10 unformed bowel movements per day or a white blood cell count of >15.0 × 109/liter (4).

Modified intent-to-treat population.

Clinical outcomes.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of clinical cures at the end of therapy in the per-protocol population. In this population, 90.6% (29 out of 32) of patients in the LFF571 treatment group and 78.3% (18 out of 23) in the vancomycin treatment group were assessed as being clinically cured at the end of therapy. The lower limits of the 90% one-sided Bayesian posterior intervals were 0% and −2% using noninformative and informative priors, respectively. Based on the protocol definition of noninferiority, these results indicated that LFF571 was noninferior to vancomycin (Table 2). While a higher proportion of LFF571-treated than vancomycin-treated patients in the per-protocol population fit the criteria for clinical cure at the end of therapy, this difference was not evident at the end-of-study visit (Table 2). Similar results were seen for the mITT population.

TABLE 2.

Proportion of patients with clinical cure by population

| Population | Time point | Proportion (no.) of patients with cure using: |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| LFF571 | Vancomycin | ||

| Per protocol | End of therapy | 0.91 (32) | 0.78 (23) |

| End of study | 0.57 (30) | 0.65 (20) | |

| mITT | End of therapy | 0.85 (46) | 0.80 (25) |

| End of study | 0.59 (46) | 0.60 (25) | |

Based on clinical symptoms and signs, 12 of 42 LFF571-treated and 7 of 24 vancomycin-treated patients who were assessed as being clinically cured or improved at the end-of-therapy visit developed recurrences of C. difficile infection during the 30-day follow-up period. The clinically defined recurrence rates were similar for the two treatment groups among the patients assessed as being clinically cured in the mITT population (30.8% for LFF571 versus 30.0% for vancomycin), although the rates in the per-protocol population were slightly higher for the LFF571-treated patients (37.0% versus 31.3% for LFF571 and vancomycin, respectively) (Table 3). The inclusion of patients assessed as being clinically improved in the mITT population did not significantly change the results (28.6% for LFF571 and 29.2% for vancomycin).

TABLE 3.

Proportion of patients with recurrences at the end of study, by population

| Population | Proportion (no.) of patients with recurrences using: |

|

|---|---|---|

| LFF571 | Vancomycin | |

| Per protocol | ||

| Clinical definition | 0.37 (27) | 0.31 (16) |

| Toxin confirmed | 0.19 (27) | 0.25 (16) |

| mITT | ||

| Clinical definition | 0.31 (39) | 0.30 (20) |

| Toxin confirmed | 0.15 (39) | 0.25 (20) |

The clinical diagnosis of recurrent C. difficile infection for the above analyses did not require recurrences to be microbiologically confirmed. Out of the 19 patients who developed a recurrence, 13 had adequate study-defined assessments for microbiological confirmation (8 who received LFF571 and 5 who received vancomycin). Two of these patients, both of whom had received LFF571, had documented eradication at the end-of-study visit, while the remaining patients had confirmed microbiological failures. An analysis of recurrence using only toxin-confirmed cases indicated that the recurrence rates were lower for LFF571-treated patients than those for vancomycin-treated patients in the per-protocol and mITT populations (Table 3). Among the 6 patients without adequate microbiological assessments, one LFF571-treated patient and one vancomycin-treated patient had toxin-confirmed recurrences that were based on local laboratory assays. Including these patients, as well as those assessed as being clinically improved, in the mITT population did not significantly change the results (data not shown).

An additional secondary efficacy outcome was the time to resolution of diarrhea. For patients in the mITT population assessed as being clinically cured at the end of therapy, the median time was 5.63 days for the LFF571-treated patients and 5.92 days for the vancomycin-treated group.

Analysis of potentially confounding factors.

Exploratory analyses were performed to determine if the efficacy results could be explained by potential confounding factors among patients in the mITT population. Three patient-associated factors trended (P < 0.200) toward being associated with a nonsuccessful clinical outcome at the end-of-study visit (clinical failure at the end-of-therapy or recurrence by the end-of-study visit): infection with an NAP1/BI/027 strain at baseline (P = 0.082), severe infection (P = 0.099), and ≥65 years of age (P = 0.140). A comparison of the potentially confounding patient-associated factors between the treatment arms did not reveal any statistically significant differences. LFF571-treated patients, however, tended to have had more potential risk factors for a poor outcome (older age [48.8 versus 41.7% for vancomycin-treated patients], more first recurrences [30.2 versus 16.7%, respectively], more severe infections [23.3 versus 12.5%, respectively], less prior effective therapy [27.9 versus 45.8%, respectively], and more concomitant antibiotic use [20.9 versus 13.0%, respectively]) than did vancomycin-treated patients (infection caused by NAP1/BI/027 [25.0 versus 38.1%, respectively], and more proton pump inhibitor use [39.5 versus 45.8%, respectively]).

Safety and tolerability.

Overall, multiple oral doses of LFF571 were safe and well tolerated in patients with C. difficile infection. The incidence of adverse events was slightly higher in LFF571-treated patients (76.1%) than in the vancomycin-treated group (69.2%), although slightly more adverse events in the vancomycin group were suspected to be related to the study drug (38.5% versus 32.6% for LFF571). Among the events that have differences in the incidences between the treatment groups of ≥5%, more LFF571-treated than vancomycin-treated patients developed anxiety and abdominal pain, while more vancomycin-treated patients developed back pain, upper respiratory infections, and hematochezia (Table 4). Abdominal pain and closely related events were more frequent in LFF571-treated (15.2%) than in vancomycin-treated (7.7%) patients, but most of the events were not suspected to be related to the study drug. Taking into account only the abdominal pain or closely related events suspected to be related to the study drug, the incidences were similar between LFF571-treated (4.3%) and vancomycin-treated (3.8%) patients. However, the small numbers of patients preclude a determination of any definitive associations of specific adverse events with LFF571 or vancomycin therapy that may exist.

TABLE 4.

Treatment-emergent adverse events reported in ≥5% in either treatment group

| Event | No. (%) with an adverse event using: |

|

|---|---|---|

| LFF571 (n = 46) | Vancomycin (n = 26) | |

| Anxiety | 5 (10.9) | 0 |

| Fall | 3 (6.5) | 2 (7.7) |

| Nausea | 4 (8.7) | 1 (3.8) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (8.7) | 0 |

| C. difficile colitis | 2 (4.3) | 2 (7.7) |

| Constipation | 3 (6.5) | 1 (3.8) |

| Flatulence | 2 (4.3) | 2 (7.7) |

| Headache | 2 (4.3) | 2 (7.7) |

| Hypokalemia | 2 (4.3) | 2 (7.7) |

| Back pain | 1 (2.2) | 2 (7.7) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 1 (2.2) | 2 (7.7) |

| Hematochezia | 0 | 2 (7.7) |

The numbers of patients with serious adverse events were similar for the two treatment groups, with 8 (17.4%) LFF571-treated patients and 5 (19.2%) vancomycin-treated patients who experienced these serious adverse events. The events that developed in the LFF571-treated patients were chemotherapy-related febrile neutropenia, leukocytosis, acute myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, cardiac arrest, adrenal insufficiency, abdominal pain, biliary dyskinesia, anal abscess, C. difficile colitis, septic shock, urinary tract infection, lung neoplasm, agitation, pulmonary mass, and hypertension. In vancomycin-treated patients, the events included C. difficile colitis, upper respiratory tract infection, urinary tract infection, aortic injury, and metastatic malignant melanoma. Each serious adverse event was reported in one patient only, except for C. difficile colitis, which was reported in two LFF571-treated patients and two vancomycin-treated patients. In general, the serious adverse events appear to reflect the underlying medical conditions of the enrolled patients. Consistent with this, all but three serious adverse events were assessed by the investigator as being not related to the study drug. The events that were possibly related to the study drug were leukocytosis and two episodes of C. difficile colitis. All three events developed in the LFF571-treated patients. One patient in the LFF571 treatment group suffered cardiac arrest and was discontinued from the study. No patient died during the study.

DISCUSSION

LFF571 was effective and well tolerated for the treatment of C. difficile infections. The primary efficacy analysis was the difference in the clinical cure rates at the end-of-therapy visit for the per-protocol population between the treatment arms. The cure rates were 90.6% and 78.3% for the LFF571- and vancomycin-treated patients, respectively. Based on the protocol-specified definition of noninferiority, it is concluded that LFF571 treatment is noninferior to vancomycin treatment. Similar results were obtained for the mITT population (84.8% versus 80.0% for LFF571 and vancomycin, respectively).

In this exploratory study, multiple additional analyses were performed to assess the impact of LFF571 on the recurrence of C. difficile infections and the appropriateness of different definitions of clinical cure and clinical relapse. When using a definition of C. difficile infection recurrence that does not require a positive toxin assay result, the recurrence rates were somewhat higher for the LFF571-treated patients than those for the vancomycin-treated patients in the per-protocol population, and they were similar in the two treatment groups for the mITT population. Classifying patients who were assessed as having clinical improvements as clinical successes did not significantly change the results for either population. The toxin-confirmed relapse rates were lower for the LFF571-treated patients than those for the vancomycin-treated patients in the per-protocol and mITT populations, with the rates for LFF571-treated (15.4%) and vancomycin-treated patients (25.3%) similar to those reported for fidaxomicin- and vancomycin-treated patients, respectively (4). The reasons for the differences in the recurrence rates based on a clinical definition or one that required confirmation with a positive toxin assay result are not clear. The study was not designed specifically to compare the rates of recurrence between the treatment arms, and the relatively small number of patients who relapsed makes the interpretation of the results difficult.

There were no statistically significant imbalances for potential confounding factors between the treatment groups. However, the LFF571-treated patients tended to have more potential risk factors for a poor outcome than did the vancomycin-treated patients. Among the LFF571-treated patients, these included older age, more first relapses, more severe infections, less prior effective therapy, and more concomitant antibiotic use. In contrast, vancomycin-treated patients were more likely to have infections caused by the NAP1/BI/027 strain of C. difficile and more proton pump inhibitor use. Although the NAP1/BI/027 strain has been associated with more severe disease, this has not been consistently reported (16, 17). The impact of any imbalances in potential confounding factors is difficult to assess given the small number of patients in the study and because none of the imbalances were statistically significant.

Multiple oral doses of LFF571 were well tolerated in patients with C. difficile infections. Although the incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events was slightly higher in the LFF571-treated patients than that in the vancomycin-treated patients, slightly more adverse events in the vancomycin group than in the LFF571 group were suspected to be related to the study drug. Abdominal pain and closely related events were more frequent in the LFF571-treated than in the vancomycin-treated patients, although the incidences were similar for events suspected to be related to the study drug. The frequencies of serious adverse events were similar for the two treatment groups, and these events appear to reflect the underlying condition of the patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support was provided by Novartis for conducting this study and preparing the manuscript.

K.D., J.P., J.A.L., J.B., and P.P. are employees of Novartis.

We thank the patients for their participation in the study. We also thank Catherine Jones for editorial support.

The study site investigators of this study were Christine Lee, St. Joseph's Healthcare, Ontario, Canada; Karl Weiss, Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Doria Grimard, Hopital de Chicoutimi, Chicoutimi, Quebec, Canada; Andre Poirier, Centre Hospitalier Regional de Trois-Rivieres, Quebec, Canada; Venkatesh Nadar, Holy Spirit Hospital, Camp Hill, PA, USA; Robert S. Jones, The Reading Hospital and Medical Center, West Reading, PA, USA; Thomas O. G. Kovacs, UCLA Digestive Diseases Clinic, Los Angeles, CA, USA; Michael S. Somero, Dr. Michael Somero Professional Corporation, Palm Desert, CA, USA; Herbert DuPont, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, TX, USA; Ian M. Baird, Remington Davis Research, Inc., Columbus, OH, USA; Ikeadi Maurice Ndukwu, St. Anthony Memorial Health Center, Michigan City, IN, USA; Curtis A. Baum, Cotton-O'Neil Clinical Research Center, Topeka, KS, USA; Alfred E. Bacon, III, Christiana Hospital, Newark, DE, USA; Robert Zajac, Alamo Clinical Research Consultants, San Antonio, TX, USA; Martha Buitrago, Idaho Falls Infectious Diseases, Idaho Falls, ID, USA; Adam Bressler, Atlanta Institute for Medical Research, Inc., Decatur, GA, USA; Kathleen M. Mullane, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA; Partha S. Nandi, Center for Digestive Health, Troy, MI, USA; John Pullman, Mercury Street Medical Group, Butte, MT, USA; Juanmanuel Gomez, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA; Miguel Trevino, Innovative Research of West Florida, Inc., Clearwater, FL, USA; Salam F. Zakko, Connecticut Gastroenterology, Bristol, CT, USA; John Stratidis, Danbury Hospital, Danbury, CT, USA; John S. Goff, Rocky Mountain Gastroenterology Associates, Lakewood, CO, USA; and Carl P. Griffin, Lynn Health Science Institute, Oklahoma City, OK, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Kelly CP, Loo VG, McDonald LC, Pepin J, Wilcox MH, Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 31:431–455. doi: 10.1086/651706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loo VG, Poirier L, Miller MA, Oughton M, Libman MD, Michaud S, Bourgault AM, Nguyen T, Frenette C, Kelly M, Vibien A, Brassard P, Fenn S, Dewar K, Hudson TJ, Horn R, Rene P, Monczak Y, Dascal A. 2005. A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med 353:2442–2449. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDonald LC, Killgore GE, Thompson A, Owens RC Jr, Kazakova SV, Sambol SP, Johnson S, Gerding DN. 2005. An epidemic, toxin gene-variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med 353:2433–2441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Louie TJ, Miller MA, Mullane KM, Weiss K, Lentnek A, Golan Y, Gorbach S, Sears P, Shue YK, OPT-80-003 Clinical Study Group. 2011. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med 364:422–431. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornely OA, Crook DW, Esposito R, Poirier A, Somero MS, Weiss K, Sears P, Gorbach S, OPT-80-004 Clinical Study Group. 2012. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for infection with Clostridium difficile in Europe, Canada, and the USA: a double-blind, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 12:281–289. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70374-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson S, Louie TJ, Gerding DN, Cornely OA, Chasan-Taber S, Fitts D, Gelone SP, Broom C, Davidson DM, Polymer Alternative for CDI Treatment (PACT) Investigators. 2014. Vancomycin, metronidazole, or tolevamer for Clostridium difficile infection: results from two multinational, randomized, controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis 59:345–354. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaMarche MJ, Leeds JA, Amaral A, Brewer JT, Bushell SM, Deng G, Dewhurst JM, Ding J, Dzink-Fox J, Gamber G, Jain A, Lee K, Lee L, Lister T, McKenney D, Mullin S, Osborne C, Palestrant D, Patane MA, Rann EM, Sachdeva M, Shao J, Tiamfook S, Trzasko A, Whitehead L, Yifru A, Yu D, Yan W, Zhu Q. 2012. Discovery of LFF571: an investigational agent for Clostridium difficile infection. J Med Chem 55:2376–2387. doi: 10.1021/jm201685h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selva E, Beretta G, Montanini N, Saddler GS, Gastaldo L, Ferrari P, Lorenzetti R, Landini P, Ripamonti F, Goldstein BP. 1991. Antibiotic GE2270 A: a novel inhibitor of bacterial protein synthesis. I. Isolation and characterization. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 44:693–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leeds JA, Sachdeva M, Mullin S, Dzink-Fox J, Lamarche MJ. 2012. Mechanism of action of and mechanism of reduced susceptibility to the novel anti-Clostridium difficile compound LFF571. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4463–4465. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06354-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Citron DM, Tyrrell KL, Merriam CV, Goldstein EJ. 2012. Comparative in vitro activities of LFF571 against Clostridium difficile and 630 other intestinal strains of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:2493–2503. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06305-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hecht D, Osmolski JR, Gerding D. 2012. In vitro activity of LFF571 against 103 clinical isolates of Clostridium difficile, abstr P-1440 Abstracts of the 22nd European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 31 March to 3 April 2012, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Debast SB, Bauer MP, Sanders IM, Wilcox MH, Kuijper EJ, ECDIS Study Group. 2013. Antimicrobial activity of LFF571 and three treatment agents against Clostridium difficile isolates collected for a pan-European survey in 2008: clinical and therapeutic implications. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:1305–1311. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trzasko A, Leeds JA, Praestgaard J, Lamarche MJ, McKenney D. 2012. Efficacy of LFF571 in a hamster model of Clostridium difficile infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4459–4462. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06355-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ting LS, Praestgaard J, Grunenberg N, Yang JC, Leeds JA, Pertel P. 2012. A first-in-human, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single- and multiple-ascending oral dose study to assess the safety and tolerability of LFF571 in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:5946–5951. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00867-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhansali SG, Mullane K, Ting LSL, Leeds JA, Dabovic K, Praestgaard J, Pertel P. 2015. Pharmacokinetics of LFF571 and vancomycin in patients with moderate Clostridium difficile infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:1441–1445. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04252-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson PE Jr, Walk ST, Bourgis AE, Liu MW, Kopliku F, Lo E, Young VB, Aronoff DM, Hanna PC. 2013. The relationship between phenotype, ribotype, and clinical disease in human Clostridium difficile isolates. Anaerobe 24:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sirard S, Valiquette L, Fortier LC. 2011. Lack of association between clinical outcome of Clostridium difficile infections, strain type, and virulence-associated phenotypes. J Clin Microbiol 49:4040–4046. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05053-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]