Abstract

The majority of azole resistance mechanisms in Aspergillus fumigatus correspond to mutations in the cyp51A gene. As azoles are less effective against infections caused by multiply azole-resistant A. fumigatus isolates, new therapeutic options are warranted for treating these infections. We therefore investigated the in vitro combination of posaconazole (POSA) and caspofungin (CAS) against 20 wild-type and resistant A. fumigatus isolates with 10 different resistance mechanisms. Fungal growth was assessed with the XTT [2,3-bis (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide inner salt] method. Pharmacodynamic interactions were assessed with the fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index (FICi) on the basis of 10% (FICi-0), 25% (FICi-1), or 53 0% (FICi-2) growth, and FICs were correlated with POSA and CAS concentrations. Synergy and antagonism were concluded when the FICi values were statistically significantly (t test, P < 0.05) lower than 1 and higher than 1.25, respectively. Significant synergy was found for all isolates with mean FICi-0 values ranging from 0.28 to 0.75 (median, 0.46). Stronger synergistic interactions were found with FICi-1 (median, 0.18; range, 0.07 to 0.47) and FICi-2 (0.31; 0.07 to 0.6). The FICi-2 values of isolates with tandem-repeat-containing mutations or codon M220 were lower than those seen with the other isolates (P < 0.01). FIC-2 values were inversely correlated with POSA MICs (rs = −0.52, P = 0.0006) and linearly with the ratio of drug concentrations in combination over the MIC of POSA (rs = 0.76, P < 0.0001) and CAS (rs = 0.52, P = 0.0004). The synergistic effect of the combination of POSA and CAS (POSA/CAS) against A. fumigatus isolates depended on the underlying azole resistance mechanism. Moreover, the drug combination synergy was found to be increased against isolates with elevated POSA MICs compared to wild-type isolates.

INTRODUCTION

The opportunistic fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus has been associated with several life-threatening infections in immunocompromised patients. Although azoles are the mainstay of antifungal therapy, treatment of aspergillosis is a difficult task which is further complicated by the lack of therapeutic efficacy in infections due to multiply azole-resistant A. fumigatus (1–3).

Azoles are inhibitors of the 14-α sterol demethylase in A. fumigatus, which is a product of cyp51A and cyp51B. Since the discovery of these orthologs to the Candida albicans egr11 gene, a number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been found, several of which have been associated with elevated azole MICs in vitro, corresponding to treatment failure in vivo (1, 4–7). It is believed that SNPs may develop through azole treatment or through exposure to azole fungicides in the environment (8–10). Treatment-induced SNPs in cyp51A are mainly allocated at codon 38, 54, or 220, while fungicide-induced SNPs are mostly located at codon 98, usually combined with tandem repeats within the promoter (8–10). Very recently, a new environmental azole resistance mechanism consisting of TR46/Y121F/T289A was reported to be associated with voriconazole treatment failure in patients with invasive aspergillosis (11, 12).

Regardless of the factor that triggers the development of SNPs in cyp51A, no tradeoff between resistance and loss of virulence has been observed (13). Indeed, animal experiments performed with isolates harboring cyp51A-mediated resistance mechanisms and the numerous reported cases of acute pulmonary aspergillosis, central nervous system aspergillosis, and disseminated disease indicate that resistant mutants retain their virulence properties (1–3, 14, 15).

The increased emergence of resistance has reduced the already limited repertoire of available antifungal agents against aspergillosis, thereby necessitating the need for developing new treatment alternatives. In recent years, combination therapy has been gaining interest and popularity, as this can enhance therapeutic efficacy and broaden the antifungal spectrum (16).

Although posaconazole is mainly proposed as a prophylactic against fungal infections, in a recent monocentric and retrospective study, the combination of caspofungin and POSA was suggested as a therapeutic regimen for effective and tolerable treatment of invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients with disease refractory to primary treatment (17). Moreover, in vitro and in vivo studies showed synergy between POSA and CAS against A. fumigatus wild-type strains (18, 19). Lepak and colleagues, however, showed that therapy using a combination of POSA and CAS (POSA/CAS) in vivo did not enhance efficacy for POSA-susceptible isolates but produced synergistic activity against two POSA-resistant isolates (20).

Whether the interaction of POSA/CAS activity against azole-resistant isolates is specific and hence is dependent on the underlying mechanisms of resistance or on the MIC factor is unknown. Therefore, the goal of the present study was to investigate the in vitro interactions of this drug using clinical A. fumigatus isolates with a wide range of azole MICs and, most importantly, with different resistance mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical isolates.

A total of 20 clinical A. fumigatus isolates were selected based on the azole resistance mechanisms (Table 1). Three isolates were defined as wild type (isolates AZN 8196, v52-76, and v28-29) on the basis of the in vitro susceptibility profile and the lack of mutations in cyp51A. Thirteen isolates were defined as non-wild type on the basis of the in vitro susceptibility profile and the presence of mutations in cyp51A that have been shown to be associated with azole resistance. Three isolates (v52-35, v45-07, and v61-76) harbored the TR34/L98H resistance mechanism, two isolates (v94-10 and v107-65) harbored TR46/Y121F/T289A, and one isolate (v49-29) harbored TR53. Four isolates harbored substitutions at codon M220 (M220I, isolate v28-77; M220V, v13-09; M220K, v59-07; and M220R, 3038), two isolates a substitution at codon G54 (G54W, v59-73 and v79-25), and one isolate a substitution at codon G138 (G138C, isolate v59-72).

TABLE 1.

MICs of posaconazole and MECs of caspofungin based on the CLSI-M38A2 methodologya

| Isolate ID | Disease | Mutation(s)c | Visual reading |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POSA MIC (mg/liter) | CAS MEC (mg/liter) | |||

| v52-35 | Proven invasive aspergillosis | TR34/L98H | 0.5 | 1 |

| v45-07 | Proven invasive aspergillosis | TR34/L98H | 1 | 1 |

| v61-76 | Proven invasive aspergillosis | TR34/L98H | 0.5 | 1 |

| v094-10 | Proven invasive aspergillosis | 46/TR | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| v107-65 | Proven CNS aspergillosis | 46/TR | 1 | 1 |

| v049-29 | Proven Aspergillus osteomyelitis | 53/TR | 0.5 | 1 |

| v059-73 | Clinical isolate (unknown entity) | G54W | >8 | 1 |

| v079-25 | Clinical isolate (unknown entity) | G54W | >8 | 1 |

| 3038 | Proven invasive aspergillosis | M220R | >8 | 0.25 |

| v28-77 | Aspergilloma | M220I | 1 | 1 |

| v59-27 | Allergic pulmonary aspergillosis | M220K | 16 | 1 |

| v13-09 | Probable invasive aspergillosis | M220V | 1 | 1 |

| v59-72 | Aspergilloma | G138C | >8 | 1 |

| AZN 8196 | Proven invasive aspergillosis | — | 0.06 | 0.5 |

| v52-76 | Proven invasive aspergillosis | — | 0.06 | 1 |

| v28-29 | Proven invasive aspergillosis | — | 0.06 | 1 |

| v67-38 (S1)b | Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis | — | 0.06 | 1 |

| v67-37 (S2)b | Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis | — | 0.125 | 1 |

| v67-36 (R1)b | Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis | HapE/P88L | 0.5 | 1 |

| v67-35 (R2)b | Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis | HapE/P88L | 0.5 | 1 |

ID, identifier; MEC, minimal effective concentration.

These four isolates were cultured consecutively from a single patient (21). Two isolates exhibited a wild-type (WT) susceptibility profile (S1 and S2), while two were azole resistant (R1 and R2). Microsatellite genotyping of all four isolates showed identical genotypes. No cyp51A mutations were found, but a P88L substitution in the CCAAT-binding transcription factor complex subunit HapE seemed to be responsible for the azole-resistant profile (22).

—, no mutations in cyp51A and/or hapE.

In addition, four isogenic A. fumigatus isolates (isolates S1, S2, R1, and R2) were used that were cultured serially from a single patient with chronic granulomatous disease (21). The patient failed azole-echinocandin therapy for treatment of chronic pulmonary Aspergillus infection. At the outset of treatment, the first two recovered isolates (S1 and S2) showed a wild-type profile; however, after 2 years of therapy, the next two isolates (R1 and R2) gained properties of resistance to all azoles. Despite elevated expression of cyp51A in isolates R1 and R2 compared to the S1 and S2 isolates, no SNPs were found in cyp51A, indicating regulation of cyp51A by the HapE resistance mechanism (21, 22). In fact, the novel resistance mechanism was caused by a P88L substitution in CCAAT-binding transcription factor complex subunit HapE (22).

As previously described, all isolates were stored at −80°C and subcultured (23, 24). All A. fumigatus isolates were identified based on the morphological characteristics and sequencing of the β-tubulin and calmodulin genes, as described previously (7). The cyp51A coding region and its promoter were sequenced as previously described (5, 25). Candida krusei ATCC 63058, C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019, and A. fumigatus MYA3561 were used as quality controls.

Susceptibility testing.

Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed based on the M38-A2 method of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (26). The drug interaction assay was performed using an 8-by-12-square checkerboard design, as previously described (27). POSA and CAS concentrations ranged from 8 to 0.002 mg/liter and from 4 to 0.06 mg/liter, respectively. Fungal growth was assessed using spectrophotometry with the modified XTT [2,3-bis (2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide inner salt] method after incubation for 48 h, as described previously (28, 29). The MIC of POSA and the minimal effective concentration (MEC) of CAS were determined as the lowest concentration showing complete inhibition (>90%) and partial inhibition (>50%; MIC-2) of growth (27). All experiments were performed in three independent replicates.

Pharmacodynamic interaction analysis.

The synergistic, additive, or antagonistic effect of paired (or more) combinations of drugs was captured by the fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index (FICi). This numerical value is calculated by the summation of the FIC for each drug (drugs A and B), where the FIC is determined by dividing the MIC of the combination of two drugs (drug A plus drug B) by the MIC of each drug alone as follows:

If the FICi ∑FICmin value is lower than 1, this indicates synergistic interaction between two drugs; if the FICi ∑FICmax value is higher than 1.25, then an antagonistic interaction exists, while the additivity range is within ∑FICmin values and ∑FICmax values of 1 to 1.25. In the current study, the fractional inhibitory concentration index was assessed as CPOSA/MICPOSA + CCAS/MICCAS, where MIC and C are the concentrations of POSA and CAS alone and in combination, respectively, corresponding to at least 10% (FICi-0), 25% (FICi-1), or 50% (FICi-2) of growth. The different endpoints of fungal growth were used in order to assess pharmacodynamic interactions at low (FICi-2), intermediate (FICi-1), and higher (FICi-0) drug concentrations. To capture both synergistic and antagonistic interactions, the FICmin and FICmax were calculated as the minimum and maximum FICi for each isolate and replicate. Synergy and antagonism were concluded when the log2 FICi values of the three independent replicates were statistically significantly (P < 0.05) lower than 1 and higher than 1.25, respectively, by Student's t test as proposed previously based on in vitro-in vivo correlation studies (30). In any other case, an additive effect was claimed.

Isolates were categorized into 5 groups based on their genetic and phenotypic characteristics as follows: (i) a wild-type group harboring neither cyp51A nor hapE mutations and demonstrating low MIC values; (ii) A TR group of isolates containing tandem repeats in the promoter (the TR group can be also referred to as the environmental resistance group because of its reported relationship with development of azole resistance due to pesticides [see introduction]); (iii) a M220 group which contained diverse substitutions at codon M220 and which were found in patients only after prolonged treatment; (iv) a G54W and G138C group (G/W) recovered from patients after prolonged azole treatment; and (v) a HapE group to be used as a control given the identical genetic backgrounds as well as the previously reported very low growth rate. Using these groups, we aimed to determine whether the FIC can be affected by a slow-growth phenotype.

Analysis.

To associate in vitro interactions with azole resistance mechanisms, the FICis of the isolates from each group were compared using analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test. To explore whether in vitro interactions were dependent on in vitro susceptibility to POSA and CAS, FICis were correlated with POSA and CAS MICs by Spearman correlation analysis. Similarly, in vitro interactions were also correlated with drug concentrations in synergistic combinations corresponding to the FICmin as absolute concentrations and as multiples of MICs after calculation of the drug concentration in combination/MIC ratio. All replicates were analyzed individually. Approximated FICs calculated from off-scale MICs were excluded from the analysis.

RESULTS

The results of FICi analysis for three growth levels are shown in Table 1, where the median and range of the MICs of the drugs alone, the FICmin, and the FICmax and the drug concentrations in combination are shown. The MIC (<10% growth endpoint) of POSA was 0.06 (range, 0.03 to 0.06) mg/liter for the wild-type isolates, whereas higher MICs were found for isolates harboring the tandem repeats (TR group), namely, the M220, G54W, and G138C mutations, for which the MICs were 0.5 (range, 0.25 to 1) mg/liter, 1 (0.5 to 4) mg/liter, and 0.25 (0.06 to 4) mg/liter, respectively, and the S1 and S2 isolates without mutations in cyp51A, for which the MIC was 0.13 (0.06 to 0.5) mg/liter. The median CAS MEC (<50% growth endpoint) ranged from 0.5 to 1 mg/liter for all isolates.

Pharmacodynamic interactions.

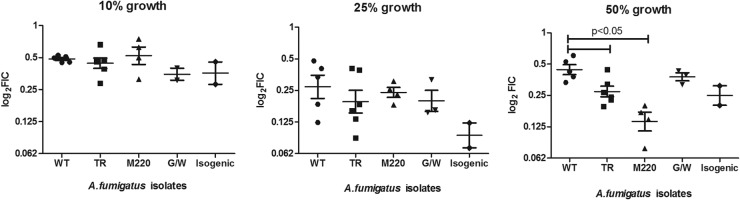

The FICimins for all isolates and growth endpoints were significantly lower than 1, indicating synergy (P < 0.05) (Table 2). None of the FICimaxs were significantly higher than 1.25, indicating that no antagonism was observed (data not shown). The lowest FICimins were found at the 25% growth endpoint for all three groups of isolates, with FICimins ranging from 0.06 to 0.76. Statistically significant differences between the four groups of isolates were found at the 50% growth endpoint, where the lowest FICimins were found for isolates of the M220 group (0.13 [range, 0.05 to 0.5] mg/liter) followed by the TR group (0.27 [0.08 to 0.76] mg/liter) and the HapE isolates (0.25 [0.13 to 0.62] mg/liter) (Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

Results of FIC index analysis based on 50%, 25%, and 10% growth endpoints for each group of A. fumigatus azole-resistant and azole-susceptible isolates harboring different or no mutations in cyp51A

| Growth endpoint (%) | Isolates | FIC index (range) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs alone |

Drugs in combinations |

|||||

| MICPOSA | MICCAS | FICimina | CPOSA | CCAS | ||

| 50 | Wild types | 0.03 (0.02–0.03) | 0.5 (0.5–1) | 0.44 (0.19–1.06)* | 0.01 (0.01–0.02) | 0.13 (0.06–0.5) |

| TR group | 0.13 (0.01–0.5) | 0.5 (0.25–1) | 0.27 (0.08–0.76)* | 0.01 (0.01–0.06) | 0.06 (0.06–0.5) | |

| M220 group | 4 (0.02–4) | 1 (0.5–8) | 0.13 (0.05–0.5)* | 0.01 (0.01–1) | 0.13 (0.06–1) | |

| G54/G138 | 4 (0.01–4) | 0.5 (0.13–2) | 0.5 (0.13–0.56)* | 0.01 (0.01–0.25) | 0.06 (0.06–0.5) | |

| HapE | 0.03 (0.01–0.13) | 1 (0.5–8) | 0.25 (0.13–0.62)* | 0.01 (0.01–0.03) | 0.13 (0.06–1) | |

| 25 | Wild types | 0.05 (0.03–0.06) | 8 (1–8) | 0.22 (0.09–0.76)* | 0.01 (0.01–0.02) | 0.5 (0.13–2) |

| TR group | 0.5 (0–1) | 8 (1–8) | 0.13 (0.06–0.52)* | 0.01 (0.01–0.13) | 0.5 (0.06–1) | |

| M220 group | 4 (0.25–4) | 8 (1–8) | 0.25 (0.07–0.5)* | 0.02 (0.01–0.25) | 1 (0.5–2) | |

| G54/G138 | 4 (0.06–4) | 5 (0.5–8) | 0.2 (0.06–1)* | 0.01 (0.01–0.13) | 0.5 (0.06–1) | |

| HapE | 0.13 (0.03–0.5) | 8 (2–8) | 0.16 (0.06–0.62)* | 0.01 (0.01–0.03) | 0.5 (0.13–2) | |

| 10 | Wild type | 0.06 (0.03–0.06) | 8 (8–8) | 0.53 (0.38–0.64)* | 0.02 (0.01–0.03) | 1 (0.06–2) |

| TR group | 0.5 (0.25–1) | 8 (8–8) | 0.52 (0.25–0.75)* | 0.13 (0.06–0.5) | 1 (0.13–2) | |

| M220 group | 1 (0.5–4) | 8 (8–8) | 0.63 (0.31–0.75)* | 0.25 (0.25–0.5) | 2 (1–2) | |

| G54/G138 | 0.25 (0.06–4) | 8 (8–8) | 0.25 (0.19–1.02)* | 0.06 (0.03–1) | 1 (0.06–2) | |

| HapE | 0.13 (0.06–0.5) | 8 (8–8) | 0.5 (0.28–0.56)* | 0.06 (0.02–0.13) | 0.5 (0.25–2) | |

*, P < 0.05.

FIG 1.

Graphical representation of FICimins determined at 10%, 25%, and 50% of growth. Five groups are presented: (i) the azole-susceptible group (wild type [WT]) with mutations neither in cyp51A nor in hapE, (ii) the azole-resistant TR group (TR34/L98H, TR46/Y121F/T289A, TR53/L98), (iii) the azole-resistant M220 group (M220V, M220K, M220I, M220R), (iv) the azole-resistant G/W group (G138C and G54W), and (v) the isogenic group consisting of the two azole-resistant R1 and R2 strains with substitutions in hpaE. The parental S1 and S2 azole-susceptible strains from R1 and R2 were added to the WT group. Significant differences were found at the 50% growth endpoint, with the strongest synergy found for isolates harboring the M220 mutation.

Drug concentrations.

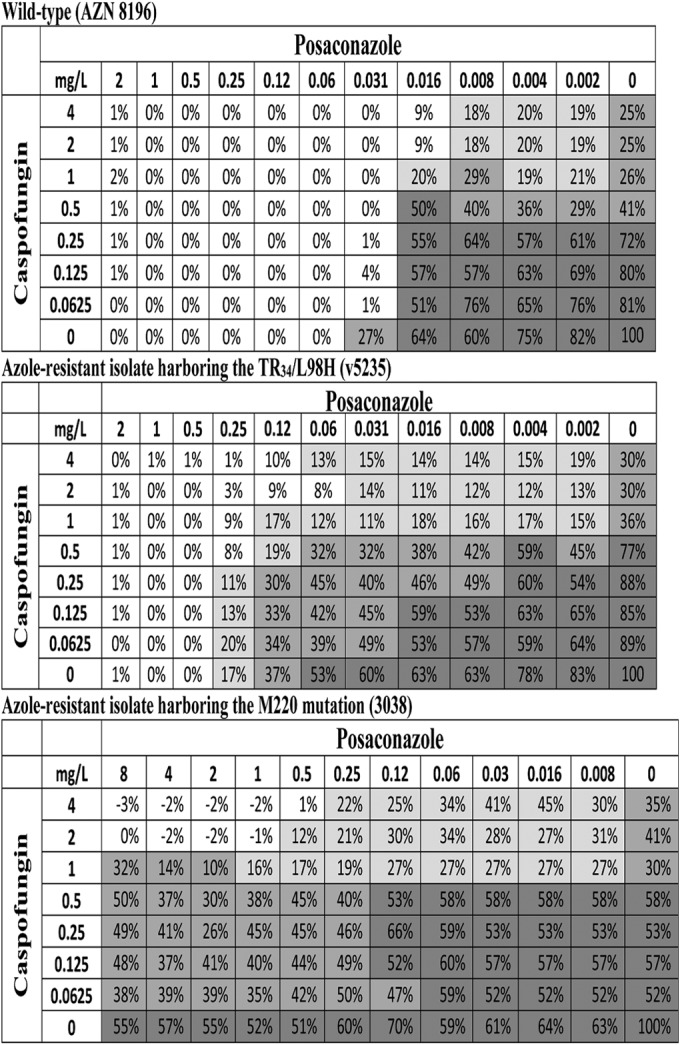

The synergistic interactions at the 10% growth endpoint (MIC effect level) were found at median POSA concentrations of 0.02 mg/liter for wild-type isolates, 0.13 and 0.25 mg/liter for the TR group and M220 group, respectively, and 0.06 mg/liter for the G54W and G138C group and HapE isolates (Table 1), which corresponded to 0.25× to 0.5× MIC for all isolates irrespective of the MICs. At higher growth endpoints (sub-MIC effect levels), lower drug concentrations (<0.25× MIC) were required to show a synergistic effect. The median CAS concentrations of the synergistic interactions at the 50% growth endpoint (MEC effect level) were 0.06 to 0.13 mg/liter and corresponded to 0.125× to 0.25× MEC. At lower growth endpoints (supra-MEC effect level), the synergistic interactions were found at concentrations of 0.5 to 2 mg/liter, which corresponded to the MEC of CAS (Table 1). In Fig. 2, three checkerboard data are shown for three A. fumigatus isolates, 1 wild type and 2 with different azole resistance mechanisms (TR34/L98H and M220), demonstrating similar FIC-0mins but different FIC-2mins. The drug concentrations where these synergistic interactions occur can be visualized for each drug and growth endpoint.

FIG 2.

Checkerboard of the POSA/CAS combination with an azole-susceptible A. fumigatus wild-type isolate (top checkerboard) and two azole-resistant A. fumigatus isolates harboring TR34/L98H (middle checkerboard) and M220 (bottom checkerboard) mutations in cyp51A. Note that the FICi-0min values (0.504, 0.376, and 0.5) were not significantly different, whereas significant differences were found for FICi-2min (1.064, 0.311, and 0.125) for the three isolates, respectively. Numbers inside the checkerboard cells represent percentages of fungal growth assessed with the modified XTT methodology, whereas the intensities of background color represent the three growth endpoints (<10%, white; <25%, light gray; <50%, dark gray).

Correlation of FICs with MICs and drug concentrations in combinations.

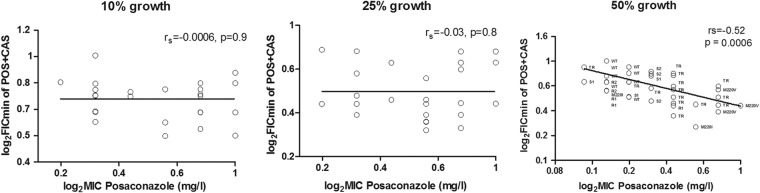

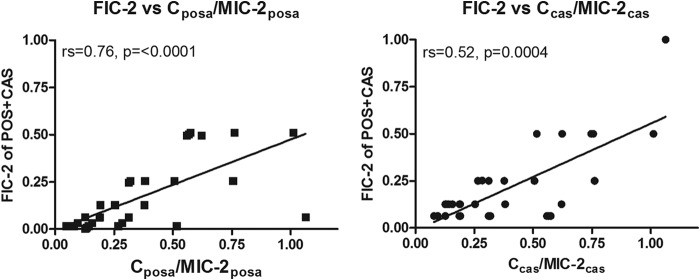

The FICi-2 values but not FICi-0 values and FICi-1 values were significantly correlated with POSA MICs (rs = −0.52, P = 0.0004), as shown in Fig. 3. No significant correlation was found with the 50% growth CAS MIC (MIC-2) values (rs = −0.17, P = 0.25). When drug concentrations in synergistic combination were analyzed as multiples of MIC but not as absolute concentrations, significant correlations between FICi-2s and POSA (rs = 0.76, P = <0.0001) and CAS (rs = 0.52, P = 0.0004) concentration/MIC-2 ratios were found (Fig. 4). In general, FICs lower than 0.25 corresponded to drug concentration/MIC ratios lower than 0.5.

FIG 3.

Correlation between FIC indices and posaconazole MICs. rs = Spearman correlation coefficient.

FIG 4.

Correlation between FICi-2s of POS/CAS combination and POSA (left graph) and CAS (right graph) concentrations over MIC-2 ratio. rs = Spearman correlation coefficient. posa, posaconazole; cas, caspofungin.

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated the potential synergism of the combination of POSA and CAS against strains with different azole-resistant mechanisms and different POSA MICs. We used strains with single mutations in cyp51A or hapE which were isolated from patients with proven aspergillosis subjected to azole therapy (1, 21, 31, 32). In addition, we used a set of azole-resistant strains isolated from patients who were potentially infected through inhalation from the environment (33–35). These environmental azole-resistant strains carried different numbers of tandem repeats in the promoter of cyp51A (10, 33).

We found that the combination of POSA/CAS was synergistic against all A. fumigatus isolates. Note that synergism between POSA and CAS was identified not only in A. fumigatus but also in Zygomycetes and Candida spp. (36–38). The previously reported FICi of 0.32 against azole-susceptible A. fumigatus was similar to the FICi found in the present study.

In the current study, however, POSA/CAS synergy in isolates with cyp51A-mediated azole resistance revealed unexpected differences in drug interactions between the different resistance mechanisms and MICs. Interestingly, the strongest synergy was found for the group of isolates harboring the tandem repeats at the promoter region of cyp51A and for the group with substitutions at the M220 hot spot region. Our results are supported by a murine model of pulmonary aspergillosis in which POSA monotherapy and CAS monotherapy demonstrated suboptimal outcomes (40% to 50% survival); however, the drug combination led to enhanced efficacy (70% to 80% survival), mostly for the groups infected with POSA-resistant isolates with drug MICs of 2 and 8 mg/liter, respectively (20). These two resistant isolates were also reported to contain G138C and TR34/L98H mutations in cyp51A.

To the best of our knowledge, drug synergy that is dependent on the resistance mechanism has not yet been reported for fungi. Although a marked synergistic effect between POSA and CAS was demonstrated in previous investigations, the mechanism of this remains unclear (18, 37). Our data show that the POSA MIC is a major determinant of the strength of the synergistic interaction and that this synergistic effect is concentration dependent, with strong interactions observed at concentrations of <0.5× MIC. In order to explain the synergistic interaction between POSA and CAS, Guembe et al. suggested that the inhibition of ergosterol biosynthesis by POSA may change the membrane, making the FKS1 enzyme more accessible or sensitive to inhibition by CAS (37). They also suggested that cell wall alterations by CAS may facilitate the penetration of POSA into the cell (37). Although these hypotheses may explain the synergistic azole-echinocandin interaction, they do not explain the differential synergistic interactions of the POSA/CAS combination that depend on the azole resistance mechanism in A. fumigatus. This phenomenon could be explained by specific qualitative or quantitative modifications of membrane sterols directly altering the membrane and indirectly altering the cell wall function. Recently, Alcazar-Fuoli et al. investigated the sterol composition of azole-susceptible and azole-resistant A. fumigatus strains (39). Resistance in these mutants developed due to deficiencies in different enzymatic steps of the ergosterol biosynthesis pathway (Cyp51A, Cyp51B, Erg3A, Erg3B, and Erg3C). The analysis showed that, although membrane sterols of azole-resistant A. fumigatus strains were qualitatively and quantitatively similar to those of the susceptible strains, the relative compositions differed, depending on the deficient enzyme (39). This indicates that alterations in the fungal membrane sterol composition may lead to differential penetration characteristics of azoles, thereby affecting POSA/CAS interaction. Yet further studies of membrane and cell wall changes performed using isolates carrying the substitutions presented in this paper will shed further light on the mechanism of azole resistance and POSA/CAS drug synergy. Earlier reports proposed that azole resistance developed by cyp51A substitutions was associated with a lack of or a reduced drug binding affinity to the 14a-demethylases due to altered amino acids close to the heme factor (40). However, the authors reported that the enzyme activity of azole-resistant isolates was not affected despite the low affinity to azoles. Thus, ergosterol is still produced in cyp51A mutants, most likely by the same or other enzymes activated in order to overcome stress situations and to preserve survival. These changes of fungal membrane sterol composition caused by azoles may also affect the 1,3-β-d-glucan synthetase function and thereby the CAS activity.

Furthermore, in a murine model of disseminated aspergillosis, although increased area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) plasma concentration values were associated with increased survival in the groups infected with the TR34/L98H and M220I isolates (MIC = 0.5 mg/liter), the G54W-infected groups (MIC > 16 mg/liter) showed no improved response (23). Apparently, this occurs because the heme factor in G54W mutants is completely blocked, thereby preventing access for POSA (41). Interestingly, the current in vitro study showed that even this obstinate POSA-resistant isolate was significantly inhibited with the combination of POSA/CAS, reaching an FIC similar to that observed in wild-type isolates.

Additionally, we recently found that acquisition of azole resistance mechanisms by A. fumigatus is sometimes associated with a fitness penalty in terms of slow growth (13). To determine the relationship between virulence and fungal growth, 15 of the 20 strains involved in the current study were used (13). That investigation revealed a strong relationship between in vivo virulence and in vitro fungal-growth-curve parameters, leading to the development of a novel mathematical model which is able to predict virulence based on in vitro growth characteristics. One of three TR34/L98H strains and isolates harboring M220K were slower growers than other isolates with either identical or nonidentical mutations and were consequently less virulent. However, the slowest growers in vitro which also demonstrated the lowest virulence in vivo were the two HapE isolates. Intriguingly, although the HapE strains were the slowest growers of the 20 isolates, we did not find a POSA/CAS synergy similar to that of the M220I or TR groups. In fact, the POSA/CAS effect on the HapE isolates revealed no significant synergistic difference from the wild-type group, indicating that the growth rate did not play a role in this unique drug interaction phenomenon.

Understanding of the acquired azole resistance mechanisms may be important to increase treatment efficacy. Overall, the current study demonstrated that POSA at concentrations ranging from 0.002 mg/liter to 0.1 mg/liter combined with CAS at concentrations from 0.06 to 0.13 mg/liter resulted in 50% reduction of growth. What is of great interest is that these levels of both drugs are clinically achievable and that the combination may therefore be clinically useful for treatment of azole-resistant aspergillus diseases (42, 43).

REFERENCES

- 1.Howard SJ, Webster I, Moore CB, Gardiner RE, Park S, Perlin DS, Denning DW. 2006. Multi-azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Int J Antimicrob Agents 28:450–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howard SJ, Cerar D, Anderson MJ, Albarrag A. 2009. Frequency and evolution of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus associated with treatment failure. Emerg Infect Dis 15:1068–1076. doi: 10.3201/eid1507.090043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verweij PE, Mellado E, Melchers WJ. 2007. Multiple-triazole-resistant aspergillosis. N Engl J Med 356:1481–1483. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc061720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mann PA, Parmegiani RM, Wei SQ, Mendrick CA, Li X, Loebenberg D, DiDomenico B, Hare RS, Walker SS, McNicholas PM. 2003. Mutations in Aspergillus fumigatus resulting in reduced susceptibility to posaconazole appear to be restricted to a single amino acid in the cytochrome P450 14alpha-demethylase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:577–581. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.2.577-581.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mellado E, Diaz-Guerra TM, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. 2001. Identification of two different 14-alpha sterol demethylase-related genes (cyp51A and cyp51B) in Aspergillus fumigatus and other Aspergillus species. J Clin Microbiol 39:2431–2438. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.7.2431-2438.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellado E, Garcia-Effron G, Alcazar-Fuoli L, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. 2004. Substitutions at methionine 220 in the 14alpha-sterol demethylase (Cyp51A) of Aspergillus fumigatus are responsible for resistance in vitro to azole antifungal drugs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:2747–2750. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2747-2750.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snelders E, van der Lee HA, Kuijpers J, Rijs AJ, Varga J, Samson RA, Mellado E, Donders AR, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2008. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus and spread of a single resistance mechanism. PLoS Med 5:e219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snelders E, Huis In 't Veld RA, Rijs AJ, Kema GH, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2009. Possible environmental origin of resistance of Aspergillus fumigatus to medical triazoles. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:4053–4057. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00231-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verweij PE, Snelders E, Kema GH, Mellado E, Melchers WJ. 2009. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: a side-effect of environmental fungicide use? Lancet Infect Dis 9:789–795. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lockhart SR, Frade JP, Etienne KA, Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Balajee SA. 2011. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from the ARTEMIS global surveillance study is primarily due to the TR/L98H mutation in the cyp51A gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4465–4468. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00185-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vermeulen E, Maertens J, Schoemans H, Lagrou K. 2012. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus due to TR46/Y121F/T289A mutation emerging in Belgium, July 2012. Euro Surveil 29:17:pii=20326 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Linden JW, Camps SM, Kampinga GA, Arends JP, Debets-Ossenkopp YJ, Haas PJ, Rijnders BJ, Kuijper EJ, van Tiel FH, Varga J, Karawajczyk A, Zoll J, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2013. Aspergillosis due to voriconazole highly resistant Aspergillus fumigatus and recovery of genetically related resistant isolates from domiciles. Clin Infect Dis 57:513–520. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mavridou E, Meletiadis J, Jancura P, Abbas S, Arendrup MC, Melchers WJ, Heskes T, Mouton JW, Verweij PE. 2013. Composite survival index to compare virulence changes in azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates. PLoS One 8:e72280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nascimento AM, Goldman GH, Park S, Marras SA, Delmas G, Oza U, Lolans K, Dudley MN, Mann PA, Perlin DS. 2003. Multiple resistance mechanisms among Aspergillus fumigatus mutants with high-level resistance to itraconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:1719–1726. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.5.1719-1726.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Linden JWM, Melchers WJG, Verweij PE, Jansen RR, Visser CE, Geerlings SE, Bresters D, Kuijper EJ. 2009. Azole-resistant central nervous system aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis 48:1111–1113. doi: 10.1086/597465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marr KA HS, Rottinghaus ST, Jagannatha S, Bow EJ, Wingard JR, Pappas P, Herbrecht R, Walsh TJ, Maertens J. 2012. A randomised, double-blind study of combination antifungal therapy with voriconazole and anidulafungin versus voriconazole monotherapy for primary treatment of invasive aspergillosis, poster LB 2812. Abstr 22nd Eur Congr Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lellek H, Waldenmaier D, Dahlke J, Ayuk FA, Wolschke C, Kroger N, Zander AR. Caspofungin plus posaconazole as salvage therapy of invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients. Mycoses 54 (Suppl 1):S39–S44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cacciapuoti A, Halpern J, Mendrick C, Norris C, Patel R, Loebenberg D. 2006. Interaction between posaconazole and caspofungin in concomitant treatment of mice with systemic Aspergillus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:2587–2590. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00829-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lepak AJ, Marchillo K, Vanhecker J, Andes DR. 2013. Posaconazole pharmacodynamic target determination against wild-type and Cyp51 mutant isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus in an in vivo model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:579–585. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01279-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lepak AJ, Marchillo K, VanHecker J, Andes DR. 2013. Impact of in vivo triazole and echinocandin combination therapy for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: enhanced efficacy against Cyp51 mutant isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5438–5447. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00833-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arendrup MC, Mavridou E, Mortensen KL, Snelders E, Frimodt-Moller N, Khan H, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2010. Development of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus during azole therapy associated with change in virulence. PLoS One 5:e10080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Camps SM, Dutilh BE, Arendrup MC, Rijs AJ, Snelders E, Huynen MA, Verweij PE, Melchers WJ. 2012. Discovery of a HapE mutation that causes azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus through whole genome sequencing and sexual crossing. PLoS One 7:e50034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mavridou E, Bruggemann RJ, Melchers WJ, Mouton JW, Verweij PE. 2010. Efficacy of posaconazole against three clinical Aspergillus fumigatus isolates with mutations in the cyp51A gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:860–865. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00931-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mavridou E, Bruggemann RJ, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE, Mouton JW. 2010. Impact of cyp51A mutations on the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of voriconazole in a murine model of disseminated aspergillosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:4758–4764. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00606-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mellado E, Garcia-Effron G, Alcázar-Fuoli L, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodríguez-Tudela JL. 2007. A new Aspergillus fumigatus resistance mechanism conferring in vitro cross-resistance to azole antifungals involves a combination of cyp51A alterations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:1897–1904. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01092-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CLSI. 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungals susceptibility testing of conidium-forming filamentous fungi: approved standard, 2nd ed M38-A2 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antachopoulos C, Meletiadis J, Sein T, Roilides E, Walsh TJ. 2007. Use of high inoculum for early metabolic signalling and rapid susceptibility testing of Aspergillus species. J Antimicrob Chemother 59:230–237. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meletiadis J, Mouton JW, Meis JF, Bouman BA, Donnelly PJ, Verweij PE. 2001. Comparison of spectrophotometric and visual readings of NCCLS method and evaluation of a colorimetric method based on reduction of a soluble tetrazolium salt, 2,3-bis 2,3-bis [2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-[(sulfenylamino) carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium-hydroxide], for antifungal susceptibility testing of Aspergillus species. J Clin Microbiol 39:4256–4263. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.12.4256-4263.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meletiadis J, Mouton JW, Meis JF, Bouman BA, Donnelly JP, Verweij PE. 2001. Colorimetric assay for antifungal susceptibility testing of aspergillus species. J Clin Microbiol 39:3402–3408. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3402-3408.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Te Dorsthorst DT, Verweij PE, Meis JF, Punt NC, Mouton JW. 2004. In vitro interactions between amphotericin B, itraconazole, and flucytosine against 21 clinical Aspergillus isolates determined by two drug interaction models. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:2007–2013. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.6.2007-2013.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellete B, Raberin H, Morel J, Flori P, Hafid J, Manhsung RT. Acquired resistance to voriconazole and itraconazole in a patient with pulmonary aspergilloma. Med Mycol 48:197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Felton TW, Baxter C, Moore CB, Roberts SA, Hope WW, Denning DW. Efficacy and safety of posaconazole for chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis 51:1383–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chowdhary A, Sharma C, van den Boom M, Yntema JB, Hagen F, Verweij PE, Meis JF. 2014. Multi-azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in the environment in Tanzania. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:2979–2983. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vermeulen E, Lagrou K, Verweij PE. 2013. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: a growing public health concern. Curr Opin Infect Dis 26:493–500. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snelders E, Camps SM, Karawajczyk A, Schaftenaar G, Kema GH, van der Lee HA, Klaassen CH, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2012. Triazole fungicides can induce cross-resistance to medical triazoles in Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS One 7:e31801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manavathu EK, Alangaden GJ, Chandrasekar PH. 2003. Differential activity of triazoles in two-drug combinations with the echinocandin caspofungin against Aspergillus fumigatus. J Antimicrob Chemother 51:1423–1425. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guembe M, Guinea J, Pelaez T, Torres-Narbona M, Bouza E. 2007. Synergistic effect of posaconazole and caspofungin against clinical zygomycetes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:3457–3458. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00595-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oliveira ER, Fothergill AW, Kirkpatrick WR, Coco BJ, Patterson TF, Redding SW. 2005. In vitro interaction of posaconazole and caspofungin against clinical isolates of Candida glabrata. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:3544–3545. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3544-3545.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alcazar-Fuoli L, Mellado E, Garcia-Effron G, Lopez JF, Grimalt JO, Cuenca-Estrella JM, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. 2008. Ergosterol biosynthesis pathway in Aspergillus fumigatus. Steroids 73:339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly SL, Lamb DC, Corran AJ, Baldwin BC, Kelly DE. 1995. Mode of action and resistance to azole antifungals associated with the formation of 14 alpha-methylergosta-8,24 (28)-dien-3 beta,6 alpha-diol. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 207:910–915. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Snelders E, Karawajczyk A, Verhoeven RJ, Venselaar H, Schaftenaar G, Verweij PE, Melchers WJ. 2011. The structure-function relationship of the Aspergillus fumigatus cyp51A L98H conversion by site-directed mutagenesis: the mechanism of L98H azole resistance. Fungal Genet Biol 48:1062–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Howard SJ, Lestner JM, Sharp A, Gregson L, Goodwin J, Slater J, Majithiya JB, Warn PA, Hope WW. 2011. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of posaconazole for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: clinical implications for antifungal therapy. J Infect Dis 203:1324–1332. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiederhold NP, Kontoyiannis DP, Chi J, Prince RA, Tam VH, Lewis RE. 2004. Pharmacodynamics of caspofungin in a murine model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: evidence of concentration-dependent activity. J Infect Dis 190:1464–1471. doi: 10.1086/424465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]