Cells lacking both nonvisual arrestins show excessive spreading, defects in focal adhesion disassembly, and sensitivity to microtubules. This phenotype is rescued by wild-type arrestins but not mutants deficient in clathrin binding, suggesting that arrestins regulate focal adhesion disassembly by linking microtubules and clathrin.

Abstract

Focal adhesions (FAs) play a key role in cell attachment, and their timely disassembly is required for cell motility. Both microtubule-dependent targeting and recruitment of clathrin are critical for FA disassembly. Here we identify nonvisual arrestins as molecular links between microtubules and clathrin. Cells lacking both nonvisual arrestins showed excessive spreading on fibronectin and poly-d-lysine, increased adhesion, and reduced motility. The absence of arrestins greatly increases the size and lifespan of FAs, indicating that arrestins are necessary for rapid FA turnover. In nocodazole washout assays, FAs in arrestin-deficient cells were unresponsive to disassociation or regrowth of microtubules, suggesting that arrestins are necessary for microtubule targeting–dependent FA disassembly. Clathrin exhibited decreased dynamics near FA in arrestin-deficient cells. In contrast to wild-type arrestins, mutants deficient in clathrin binding did not rescue the phenotype. Collectively the data indicate that arrestins are key regulators of FA disassembly linking microtubules and clathrin.

INTRODUCTION

Focal adhesions (FAs) are complex structural entities that play a key role in cell interactions with extracellular matrix (Gieger et al., 2009; Plotnikov and Waterman, 2013). Rapid formation and timely disassembly of FA are critical for the organization of actin cytoskeleton and cell motility. Microtubule proximity and clathrin-dependent internalization of integrins were implicated in FA disassembly (Kaverina et al., 1999; Small et al., 2002; Ezratty et al., 2005, 2009), but the connection between the two remains obscure.

Arrestins were first discovered as regulators of G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling (Gurevich and Gurevich, 2006a) and later found to bind >100 nonreceptor partners (Xiao et al., 2007). Recent studies implicated nonvisual arrestins in regulation of actin cytoskeleton and cell migration (Ge et al., 2003; Hunton et al., 2005; Scott et al., 2006; Min and DeFea, 2011), but how arrestins contribute to these processes is unclear. Of importance, arrestins directly bind both clathrin (Goodman et al., 1996) and microtubules (Hanson et al., 2007), suggesting that microtubule-bound arrestins might recruit clathrin to FAs. Therefore we investigated the role of arrestins in cell migration and regulation of cell shape. Here we show that both arrestin-2 and arrestin-3 regulate FA dynamics independently of GPCRs, with profound effects on cell spreading and migration. (We use the systematic names of arrestin proteins: arrestin-1 [historic names S-antigen, 48-kDa protein, visual or rod arrestin], arrestin-2 [β-arrestin or β-arrestin1], arrestin-3 [β-arrestin2 or hTHY-ARRX], and arrestin-4 [cone or X-arrestin; for unclear reasons, its gene is called “arrestin 3” in the HUGO database].)

RESULTS

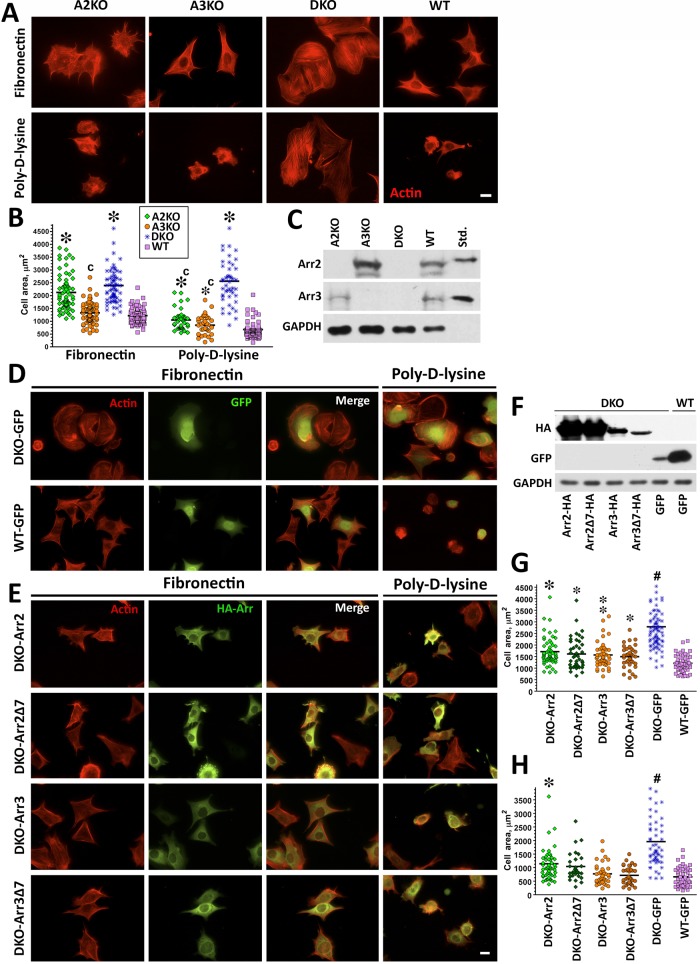

Arrestins regulate cell morphology by altering the cytoskeleton

Double arrestin-2/3 knockout (DKO) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were introduced more than a decade ago (Kohout et al., 2001), but their larger size and peculiar shape, dramatically different from that of wild-type (WT) MEFs, were routinely ignored. The actin cytoskeleton of arrestin DKO cells plated on fibronectin (FN) was drastically different from that in WT (Figure 1A), and DKO cells were twice as large (Figure 1B). DKO cell spreading on poly-d-lysine (PDL), which binds integrins but does not promote their clustering and activation, was similar to that on FN (Figure 1, A and B). In contrast, WT cells do not spread well on PDL: the average cell area was reduced nearly by half (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1:

Knockout of both nonvisual arrestins dramatically alters cytoskeleton. (A) Cells lacking arrestin-2 (A2KO), arrestin-3 (A3KO), or both (DKO) and WT cells were stained with rhodamine–phalloidin after spreading for 2 h on FN or PDL. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) The size of 50 cells in each of the three experiments was quantified at each time point on FN or PDL. The cell size data were analyzed by Kruskal–Wallis analysis of variance, followed by posthoc pairwise comparison by Mann–Whitney test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.001 compared with WT, cp < 0.001 compared with DKO. (C) Expression of arrestins in DKO and WT cells was detected by Western blot. Purified bovine arrestin-2 and arrestin-3 (0.2 ng/lane) were run for comparison. (D, E) DKO cells were retrovirally infected with Ha-tagged arrestin-2 (Arr2), arrestin-2-Δ7 (Arr2Δ7), arrestin-3 (Arr3), arrestin-3-Δ7 (Arr3Δ7), or GFP as a control (DKO and WT). Cells were plated on FN and PDL. Arrestin-expressing cells were stained for actin and HA (E), and control cells were stained for actin and GFP (D). Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) Western blots showing the expression of HA-arrestins and GFP. GAPDH is used as a loading control. (G) Cell size was measured on FN and analyzed as described for B. #p < 0.001 DKO from all other conditions, *p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 to WT. Data are from 37–82 cells/condition from three or four experiments. (H) Cell size was measured on PDL from 29–54 cells in three experiments and analyzed as in B. #p < 0.001 for DKO from all other conditions, *p < 0.001 from WT.

To confirm that the absence of arrestin-2/3 is responsible for the morphological phenotype of DKO cells, we tested whether retroviral expression of arrestin-2 or arrestin-3 rescues them. To ensure that infection did not affect cell morphology, we used cells infected with green fluorescent protein (GFP) as controls (Figure 1D). Cells plated on FN or PDL were stained for hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged arrestins and actin filaments (Figure 1E). The expression of either of the nonvisual arrestins (Figure 1F) reduces DKO cell size nearly back to WT on FN and PDL. Cells expressing arrestin-3 are closer to WT, whereas the rescue by arrestin-2 is partial (Figure 1, G and H). Thus each nonvisual arrestin significantly affects cell spreading. Single- arrestin-2 or -3–knockout cells do not reach the size of DKO MEFs and behave like WT MEFs on PDL, further supporting this notion (Figure 1, A–C).

The best-characterized function of arrestins is their high-affinity binding to active phosphorylated GPCRs (Gurevich and Gurevich, 2006b). To test whether arrestin interactions with GPCRs play a role in cell spreading, we used receptor binding–deficient arrestin mutants with a 7-residue deletion in the interdomain hinge (Δ7; Hanson et al., 2007; Breitman et al., 2012). Similar to WT arrestin-2 and -3, both Δ7 mutants effectively reduced the size of DKO cells to WT level on FN and PDL (Figure 1, D, E, G, and H). Thus GPCR binding is not essential for arrestin-dependent regulation of cell spreading.

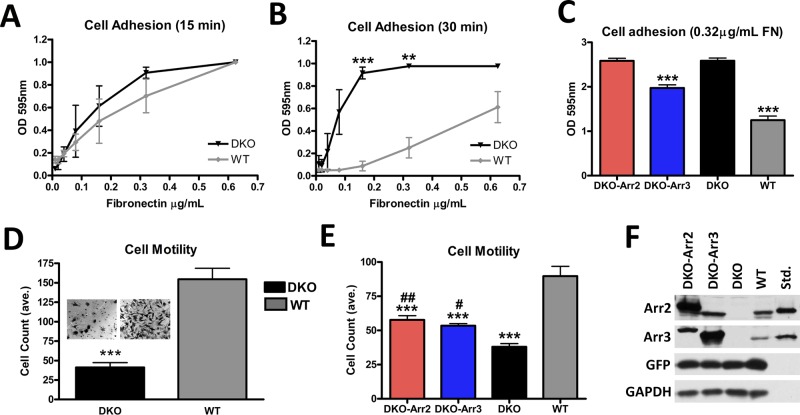

Arrestins regulate migration and adhesion

Cytoskeletal rearrangements drive cell movement and adhesion. Therefore we tested whether the lack of arrestins affects adhesion and migration. The adhesion of DKO cells was similar to WT after initial attachment (15 min; Figure 2A), but they adhered significantly better than WT as cells began to spread (30 min; Figure 2B). Thus DKO cells form initial attachments similar to WT but later demonstrate enhanced adhesion. Moreover, DKO cells demonstrated 3.8-fold- reduced migration toward the FN substrate in a Transwell assay (Figure 2D).

FIGURE 2:

Arrestins regulate cell migration and adhesion. (A, B) Adhesion was measured by plating cells on serial dilutions of FN (0.01–1.25 μg/ml) for 15 (A) or 30 (B) min. The data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with arrestin type as the main factor, which was highly significant at 30 min. DKO cells showed a dramatic increase in their ability to adhere compared with WT cells, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01. Means ± SD from three experiments. (C) Adhesion of DKO cells expressing arrestin-2 + GFP, arrestin-3 + GFP, or GFP alone (controls). Cells were plated on 0.32 μg/ml FN. Means ± SD from 24 data points in three experiments. ***p < 0.001 compared with DKO. (D) Cells were plated in Transwell chambers coated with 0.32 μg/ml FN and allowed to migrate for 4 h. Cells were counted in six fields/chamber in each of four independent experiments. The data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with cell type as the main factor, ***p <0.001. Insets, representative membranes postmigration. (E) Migration of DKO cells expressing arrestin-2 and GFP or arrestin-3 and GFP, or cells expressing GFP only (DKO and WT). Means ± SD from 5 fields/chamber from three independent experiments performed in duplicate analyzed by one-way ANOVA with cell type as the main factor. ***p < 0.001 compared with WT. DKO-Arr2, ##p < 0.01, and DKO-Arr3, #p < 0.05, compared with DKO. (F) Arrestin expression in DKO cells was determined using arrestin-2– or arrestin-3–specific antibodies, with corresponding purified bovine arrestins (0.1 ng/lane) run as standards.

To determine whether the reversal of DKO morphology by arrestin-2 or -3 rescues enhanced adhesion and motility deficit, were infected DKO cells with arrestin-2 or -3 in constructs that drive GFP coexpression, with controls expressing only GFP. Cells were sorted for GFP expression (Figure 2F) and used in adhesion and Transwell migration assays. Of interest, arrestin-3 but not arrestin-2 reduces the adhesion of DKO cells, although not to WT level (Figure 2C). Similarly, we found dramatically reduced adhesion of HEK293a cells overexpressing arrestin-3 compared with control cells expressing arrestin-2 or pcDNA3 (Supplemental Figure S1). However, both arrestin-2 and -3 partially rescued the migration defect of DKO cells (Figure 2E), suggesting that cell spreading and motility are regulated via the same arrestin-dependent mechanism(s), but the two nonvisual arrestins likely work in concert to yield WT behavior.

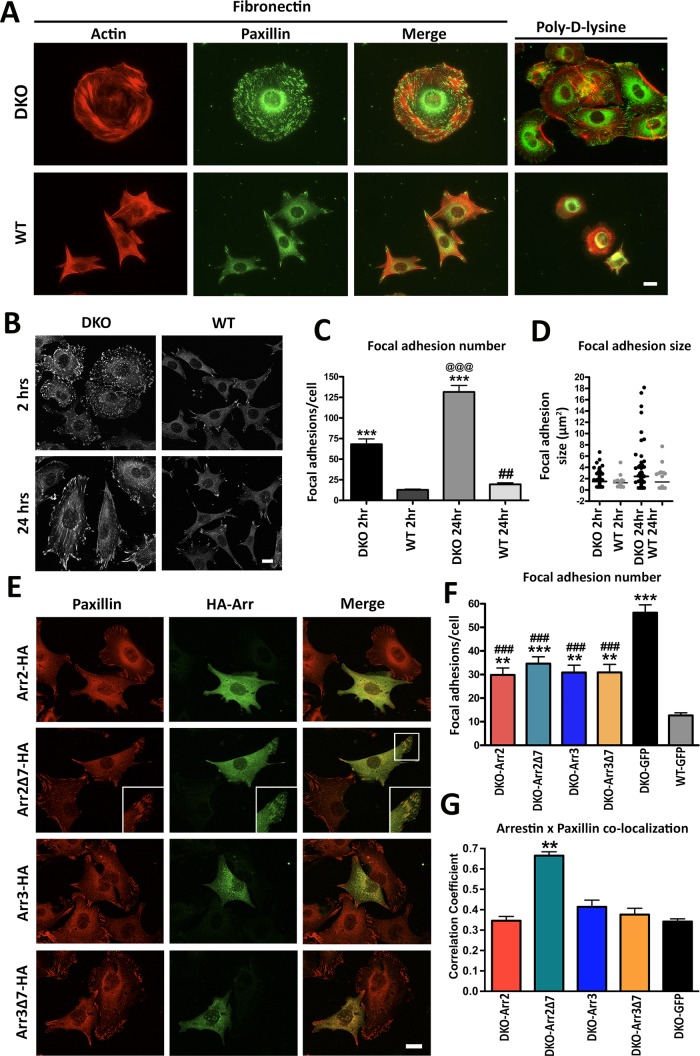

Focal adhesion number and size are increased in arrestin-deficient cells

FAs are key signaling hubs that recruit many proteins to the site of integrin activation (Sastry and Burridge, 2000; Gieger et al., 2009). Arrestins bind Src, ERK1/2, and JNK3 (Gurevich and Gurevich, 2006b), all of which regulate FAs (Webb et al., 2004; Huveneers and Danen, 2009). Rapid assembly and disassembly of these complexes plays a central role in cell adhesion and migration. On the basis of the decreased migration and increased adhesion of DKO cells, we hypothesized that FA dynamics is likely affected. To test this idea, we stained cells with rhodamine–phalloidin and an anti-paxillin antibody to visualize actin cytoskeleton and FAs, respectively. In WT MEFs, we observed a small number of FAs located primarily at the edges of cells plated on FN and virtually none in cells plated on PDL (Figure 3A). Strikingly, in DKO cells, the number of FAs was dramatically increased. In addition, FAs in DKO MEFs were present not only at the periphery but also throughout the cell on both FN and PDL (Figure 3A). Immunostaining for active phospho-paxillin (P-Y118) and phospho-FAK (P-Y397) also revealed similar differences in FA number and localization between WT and DKO cells (Supplemental Figure S2, A–C). Of importance, in single-knockout cells, the FA pattern was similar to WT on PDL, but cells lacking either arrestin had more FAs on FN, although not as many as DKO MEFs (Supplemental Figure S3, A–C). These data suggest that both arrestin-2 and -3 participate in the regulation of FAs and cell size, and the magnitude of DKO phenotype reflects the absence of both arrestins.

FIGURE 3:

Arrestin knockout increases number and size of focal adhesions. (A) Focal adhesions were detected in DKO and WT cells after 2 h on FN or PDL with anti-paxillin antibody. (B) Cells were plated on FN for 2 or 24 h, and focal adhesions were visualized by paxillin staining. (C) The focal adhesions in DKO and WT cells plated on FN for 2 or 24 h were quantified and analyzed by two-way ANOVA with genotype and time as main factors. ***p < 0.001 compared with WT, @@@p < 0.001 DKO 24 h compared with DKO 2 h, and ##p < 0.01 WT 24 h compared with WT 2h according to Bonferroni/Dunn posthoc test with correction for multiple comparisons. Means ± SD from three experiments (45–67 cells in each). (D) Distribution of focal adhesion size shown by scatter-plot. Focal adhesion size distributions were analyzed by nonparametric Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Revealed differences: DKO 2 h, p = 0.0023; DKO 24 h, p < 0.0001; WT 24 h, p < 0.0001, as compared with WT 2 h. Data for 600–5000 focal adhesions. (E) Confocal images of DKO and WT cells expressing HA-tagged arrestins and stained for paxillin. Inset, arrestin-2-Δ7 colocalization with paxillin. (F) Focal adhesion number was calculated in arrestin-expressing DKO cells (25–50 cells/condition). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with arrestin type as the main factor. **p < 0.01 DKO-arrestin-2, DKO-arrestin-3, DKO-arrestin-3Δ7 compared with WT; ***p < 0.001 DKO-arrestin-2-Δ7 compared with WT; ###p < 0.001 compared with DKO-GFP according to Bonferroni/Dunn posthoc test with correction for multiple comparisons. Scale bar, 10 μm (A, B, and E). (G) Colocalization of paxillin (red) and arrestins or GFP control (green) was determined using Coloc2 function in ImageJ after background correction in cells expressing HA-arrestins and stained for HA and endogenous paxillin, as described in Materials and Methods.

To assess the role of FA dynamics in this phenotype, we measured FA number as a function of time in WT and DKO MEFs (Figure 3, B and C). After 2 h on FN, DKO cells have approximately fivefold more FAs than WT. After 24 h, the number of FAs in DKO cells further doubled, whereas WT cells showed only a slight increase (Figure 3C). The difference in FA size distribution between DKO and WT cells also increased over time, with DKO cells demonstrating an accumulation of very large FAs at 24 h (Figure 3D). To determine whether the increase in FAs in DKO cells was associated with higher expression of FA components, we measured total paxillin and FAK by Western blot. Of interest, we found that total levels of FA proteins in DKO cells were similar to if not lower than in WT (Supplemental Figure S4, A–E). However, total and surface β1-integrin levels were significantly higher in DKO than in WT MEFs, as measured by both fluorescence-activated cell sorting and Western blot (Supplemental Figure S4, F and G). These results, along with our dynamic adhesion data (Figure 2, A and B) suggest that DKO MEFs form initial adhesions similar to WT but have an advantage in spreading due to increased availability of integrins.

To determine whether the FA phenotype of DKO cells can be rescued by arrestins, we expressed HA-tagged WT and Δ7 arrestin-2 and -3 and stained for paxillin to determine FA number (Figure 3E). DKO and WT cells expressing GFP served as controls, and only the cells expressing GFP- or HA-tagged arrestins were used for analysis (Supplemental Figure S3D). We found that the expression of WT arrestin-2 or arrestin-3, as well as of their GPCR binding–deficient mutants, reduces FA number, although not to WT level (Figure 3F). Although it was expected to be difficult to see clear colocalization of any protein with arrestins, which are widely distributed in the cytoplasm, with light microscopy, we detected colocalization of arrestin-2-Δ7 with FAs (Figure 3, E, insets, and G), likely because of its deficient GPCR binding and higher microtubule affinity (Hanson et al., 2007). Thus arrestins likely directly regulate FA dynamics via binding to one or more of FA-associated proteins.

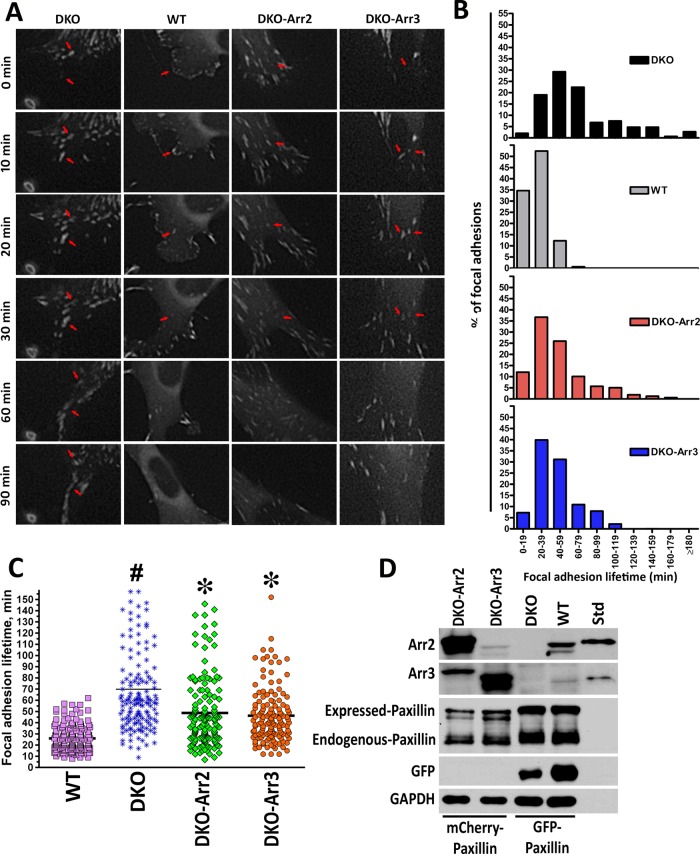

Arrestins are necessary for rapid FA disassembly

The accumulation and enlargement of FAs in DKO cells (Figure 3, C and D) suggest that the rate of FA disassembly might be reduced. To test this idea, we expressed GFP-paxillin in DKO and WT cells (Figure 4) and measured FA lifetimes using live-cell imaging (Figure 4, A and B). Individual FAs at the leading edge of the cell were tracked from formation to disassembly (representative FAs are indicated by red arrows in Figure 4A). All FAs in WT cells formed and disassembled within 20–40 min (Figure 4B), with a median lifetime of 23 min (Figure 4C). In contrast, lifetimes of FAs in DKO cells showed much broader distribution, with median ∼59 min. Of note, some FAs in DKO cells persisted >3 h (Figure 4B). DKO cells also demonstrated a defect in leading edge formation and loss of polarity (Supplemental Movies S1–S4). To test whether the defect in FA disassembly is a result of the lack of arrestins, we transfected red mCherry-paxillin into cells coexpressing GFP with arrestins (Figure 4D). Live-cell imaging revealed a shift in FA lifetimes toward WT (Figure 4, B and C), with median values reduced to 42 and 40.5 min in cells expressing arrestin-2 and arrestin-3, respectively (Figure 4C). Thus arrestins regulate FA turnover, and normal dynamics requires the presence of both subtypes.

FIGURE 4:

Arrestins regulate focal adhesion dynamics. (A) DKO and WT cells expressing GFP-paxillin were viewed with DeltaVision Core microscope, and images were captured at 1-min intervals. Representative images at 0, 10, 20, 30, 60, and 90 min. Arrowheads indicate representative focal adhesions. Scale bar, 10 μm. FA lifetimes were determined by counting the number of sequential frames where individual FA (GFP-paxillin) is visible. (B) Histogram distributions of FA lifetimes in 20-min intervals. Data from two or three experiments (150 FAs in 15 cells for each cell type). All distributions are significantly different from each other (p < 0.0001), except for DKO-Arr2 and DKO-Arr3 FA lifetimes, according to nonparametric Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. (C) The distribution of FA lifetimes in indicated cells. *p < 0.001 to DKO; bp < 0.01, #p < 0.001 to WT according to Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test (H = 170.637, p < 0.0001; H corrected for ties = 170.679, tied p < 0.001). The data were also analyzed with Mann–Whitney test for means (pairwise comparisons: WT–DKO p < 0.0001; DKO–DKO-Arr2 p < 0.0001; DKO–DKO-Arr3 p < 0.0001). (D) Expression of arrestins and tagged paxillin determined by Western blot with bovine arrestin-2 and arrestin-3 (0.1 ng/lane) as standards (Std).

Microtubule targeting of focal adhesions is impaired in DKO cells

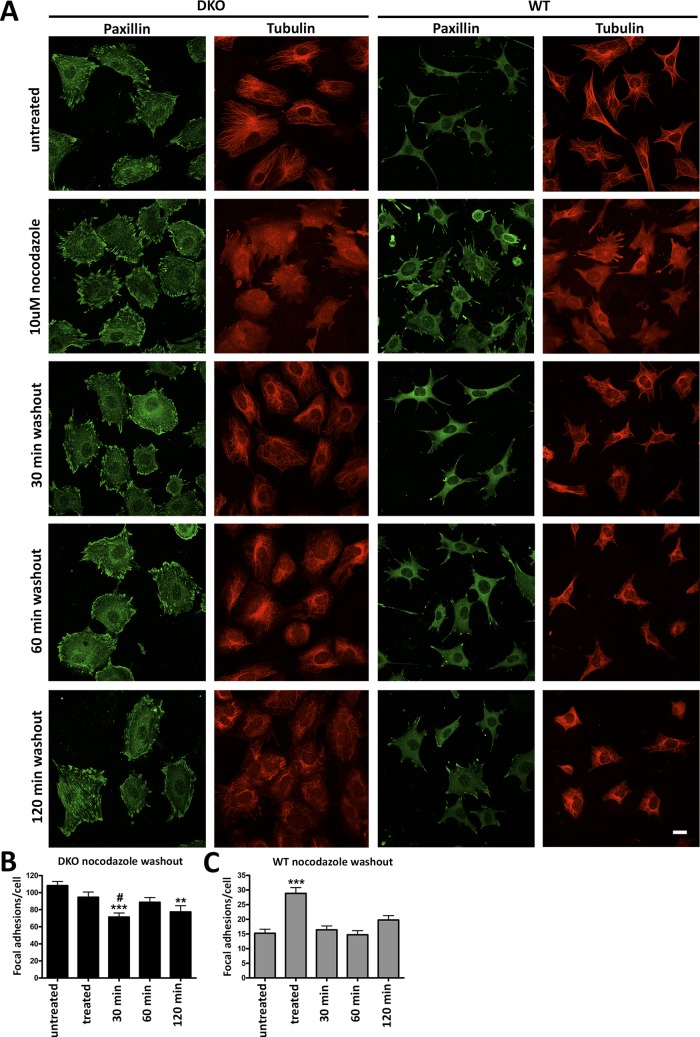

The dramatic defect in FA disassembly in DKO cells suggests that arrestins regulate FA turnover. Microtubule targeting of FAs promotes disassembly (Kaverina et al., 1999; Small et al., 2002) in a RhoA-independent manner (Ezratty et al., 2005, 2009). Because arrestins bind clathrin (Goodman et al., 1996) and microtubules (Hanson et al., 2007), we hypothesized that microtubule-bound arrestins might recruit clathrin necessary for FA turnover (Ezratty et al., 2009). To test whether the absence of arrestins specifically affects microtubule-dependent FA disassembly, we treated WT and DKO cells with nocodazole to destabilize microtubules, and then monitored FAs as the microtubules regrew (Figure 5A). Consistent with previous reports, upon nocodazole treatment of WT cells, the number of FAs doubled. In agreement with FA lifetimes determined in live-cell imaging (Figure 4), after 30 min of nocodazole washout, the number of FAs in WT cells returned to baseline level, paralleling microtubule regrowth (Figure 5C). In contrast, DKO cells did not respond to either microtubule destabilization or regrowth, suggesting that microtubules have little effect on FAs in cells lacking arrestins (Figure 5B). Thus arrestins likely participate in microtubule-dependent rapid FA disassembly.

FIGURE 5:

Nocodazole treatment reveals different focal adhesion dynamics in WT and DKO cells. (A) DKO and WT cells were plated for 24 h and treated with or without 10 μM nocodazole for 2 h. Nocodazole was washed out, and microtubules were allowed to regrow for 30, 60, or 120 min. Paxillin and microtubules were visualized with respective antibodies. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B, C) Means ± SD number of FAs in 40–50 cells/condition. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with treatment as the main factor, followed by Bonferroni/Dunn posthoc test with correction for multiple comparisons. (B) DKO cells: ***p < 0.001, 30-min washout compared with untreated cells; #p < 0.05 compared with treated cells; **p < 0.01, 120-min washout compared with untreated cells. (C) WT cells: ***p < 0.001, treated cells compared with all other conditions.

Arrestin interaction with clathrin is important for FA dynamics

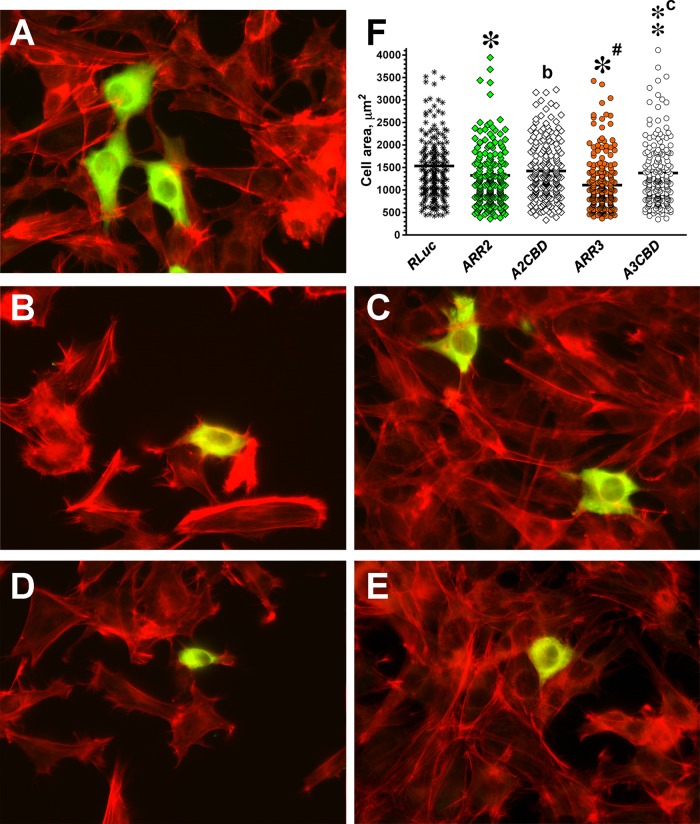

Arrestins promote GPCR internalization by virtue of their interaction with clathrin (Goodman et al., 1996) and the clathrin adaptor AP2 (Laporte et al., 2000). Mutations eliminating clathrin- or AP2-binding sites in the arrestin C-tail significantly reduce receptor internalization (Kim and Benovic, 2002). Clathrin was implicated in microtubule-dependent FA disassembly (Ezratty et al., 2009), suggesting that a defect in clathrin recruitment to FA in arrestin-2/3 DKO cells might contribute to their peculiar morphology. To test this idea, we compared DKO cell rescue by WT arrestin-2 and -3 and mutants with disabled clathrin-binding sites, A2CBD and A3CBD, respectively. These four-residue mutations do not perturb other arrestin functions (Kim and Benovic, 2002). DKO cells transfected with HA-tagged arrestins or HA-RLuc and plated on FN were stained for HA tag and actin (Figure 6A). HA-RLuc was used as a control to ensure appropriate selection of transfected cells and rule out the effect of transfection on cell morphology. We confirmed that the expression of WT arrestin-2 or -3 significantly reduced DKO cell size (Figure 6, A, B, D, and F). Arr2CBD had no effect, and the similar arrestin-3 mutant A3CBD reduced cell size much less effectively than WT arrestin-3 (Figure 6, C, E, and F). Partial effectiveness of this mutant might be the result of indirect clathrin binding via AP2. The AP2-binding site was not disabled because it includes an arginine that is part of the main phosphate sensor, and therefore AP2 binding cannot be completely eliminated without changing other functional characteristics of arrestins. The data suggest that arrestins are involved in microtubule-dependent FA regulation, and their binding to clathrin is necessary for the ability of arrestins to rescue the DKO phenotype.

FIGURE 6:

Arrestin interaction with clathrin contributes to arrestin-dependent regulation of cell morphology. (A–E) Representative images of DKO cells expressing HA-tagged arrestin stained with anti-HA antibodies (green) and rhodamine–phalloidin (red). (A) Control DKO MEFs transfected with HA-Rluc. (B) DKO MEFs transfected with WT arrestin-2. (C) DKO MEFs expressing clathrin binding–deficient A2CBD mutant. (D) DKO MEFs expressing WT arrestin-3. (E) DKO MEFS expressing A3CBD mutant. (F) Scatter plot showing the results of cell size analysis. The horizontal bars represent the medians. The cell size data were analyzed by Kruskal–Wallis analysis of variance, followed by posthoc pairwise comparison by Mann–Whitney test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Data are from ∼200 cells/condition from four independent experiments. *p < 0.001, **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05, as compared with cells expressing RLuc; ap < 0.05; cp < 0.001, as compared with cells expressing corresponding WT arrestins.

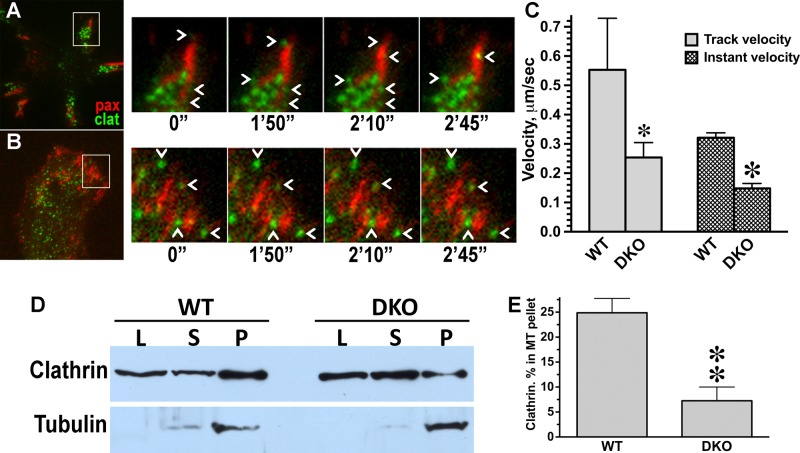

Arrestin DKO cells exhibit slower dynamics of clathrin-coated pits in focal adhesion areas

Clathrin was shown to facilitate FA disassembly by actively promoting endocytosis and removal of FA components (Gurevich et al., 2002; Ezratty et al., 2009). To test whether arrestins regulate this function of clathrin, we examined the dynamics of clathrin-coated pits in the vicinity of FAs in WT and DKO cells coexpressing GFP-paxillin (to label FAs) and mCherry-clathrin, using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM) live-cell analysis. We found significantly slower dynamics of clathrin-coated pits near FAs in DKO than with WT cells (Figure 7 and Supplemental Movies S5 and S6), suggesting that endocytic activity at these sites was strongly reduced. If clathrin is recruited to microtubules via arrestins, its association with the cytoskeleton should be reduced in DKO cells. To test this prediction experimentally, we pelleted Taxol-stabilized microtubules from WT and DKO cells and measured clathrin content in the pellet and supernatant by Western blot (Figure 7, D and E). Quantification showed that the fraction of microtubule-associated clathrin in DKO cells is dramatically lower than in WT MEFs, supporting arrestin dependence of clathrin recruitment to microtubules. Collectively our data implicate nonvisual arrestins in regulation of FA dynamics by modulating microtubule- and clathrin-dependent disassembly.

FIGURE 7:

Arrestins are required for normal clathrin dynamics at FA. (A, B) Frames from representative live-cell TIRF imaging sequences of MEFs coexpressing FA marker GFP-paxillin and mCherry-clathrin. (A) WT MEFs. (B) DKO MEFs. Cell overviews are shown on the left. Boxed regions from overviews are enlarged on the right over the time period of 2 min, 45 s. Chevrons indicate clathrin pits, which appear and disappear in WT but are stationary in DKO cell. (C) Velocity of clathrin pit movement at FA is significantly higher in WT than in DKO cells. *p < 0.05 for the track velocity, ★p < 0.001 for instant velocity, according to unpaired Student's t test. (D) DKO and WT MEFs were fractionated as described in Materials and Methods. Aliquots of lysate (L), supernatant (S), and microtubule pellet (P) were analyzed by Western blot using clathrin (top blot) and tubulin (bottom blot) antibodies. (E) The distribution of clathrin between supernatant and microtubule pellet was calculated for two experiments. **p < 0.01, unpaired Student's t test.

DISCUSSION

Arrestins were first identified as terminators of GPCR signaling that block G protein coupling upon binding to active phosphorylated receptors (Gurevich and Gurevich, 2006b). Subsequently arrestins were shown to bind a variety of other proteins, including components of the endocytic machinery clathrin (Goodman et al., 1996) and AP2 (Laporte et al., 2000), mitogen-activated protein kinases (McDonald et al., 2000; Luttrell et al., 2001; Bruchas et al., 2006; Song et al., 2009), ubiquitin ligases (Shenoy et al., 2001; Bhandari et al., 2007; Ahmed et al., 2011), and phosphodiesterase PDE4 (Perry et al., 2002). Arrestins have recently emerged as important players in cytoskeleton regulation via binding to microtubules (Hanson et al., 2007) and the centrosome (Shankar et al., 2010) and regulation of small GTPases (Barnes et al., 2004; Kim and Han, 2007; Anthony et al., 2011). Despite clear interest in arrestin-dependent control of the cytoskeleton (Chrzanowska-Wodnicka and Burridge, 1996; Min and DeFea, 2011), very few mechanistic details have been established. Here we describe a dramatic phenotype of arrestin-2/3 DKO MEFs and demonstrate that arrestins regulate cell morphology by altering FA dynamics in a receptor-independent manner. Cells lacking both arrestins demonstrate dramatically increased spreading in both matrix-dependent (FN) and matrix-independent (PDL) conditions.

Therefore we tested whether arrestins play a role in cell adhesion and migration and found that arrestin-2/3 knockout decreased cell migration (Figure 2D) and enhanced adhesion (Figure 2B). Individual arrestin-2 or arrestin-3 partially rescued the phenotype. We found that the numbers and sizes of FAs are dramatically increased in arrestin-null cells, and the difference with WT cells increases with attachment time (Figure 3, C and D). Of importance, the difference in adhesion was not due to gross changes in the total levels of FA proteins: if anything, total levels of paxillin and FAK in DKO cells were lower than in WT MEFs (Supplemental Figure S4). An increase in surface integrin (Supplemental Figure S4) is consistent with the impairment of FA turnover. Live-cell imaging showed that FA lifetimes in DKO cells are much longer than in WT (Figure 3). Of importance, expressed arrestin-2 or -3 in DKO cells partially rescued FA dynamics, suggesting that both are required for rapid FA turnover (Figure 3).

Microtubule targeting has been established as a major regulator of FA disassembly (Kaverina et al., 1999; Small et al., 2002). One study (Ezratty et al., 2005) revealed that FA disassembly requires microtubules and dynamin, neither of which participates in FA assembly. FAs in DKO cells do not respond to nocodazole treatment: additional FAs do not form when microtubules are destroyed, and FA disassembly is abnormal during microtubule regrowth in these cells (Figure 5, A and B). Therefore it is tempting to speculate that arrestins, known to bind microtubules (Hanson et al., 2007), are delivered by microtubules to FAs to facilitate disassembly. The involvement of dynamin in microtubule-induced disassembly suggested that endocytosis of integrins and/or other FA components is the rate-limiting step (Ezratty et al., 2005). This was shown to be the case: integrin endocytosis mediated by clathrin, and Dab2 is directly involved in microtubule-induced FA disassembly (Ezratty et al., 2009). It was suggested that microtubules deliver clathrin and Dab2 to FAs, and rapid accumulation of these proteins near FAs targeted by microtubules was documented (Ezratty et al., 2009). Our data are consistent with this hypothesis: the higher proportion of β1-integrin on the surface of DKO cells is an expected consequence of its impaired internalization. Arrestins participate in the endocytosis of GPCRs and other membrane receptors (Gurevich and Gurevich, 2004). Our finding that arrestin-2-Δ7 mutant with enhanced microtubule binding (Hanson et al., 2007) shows subcellular localization similar to paxillin suggests that arrestins likely localize to FAs, which would place them in the proximity of integrins. The fact that this mutant, frozen in the microtubule-bound conformation, shows stronger FA localization than WT (Figure 3E) suggests that binding to microtubules might facilitate arrestin localization to FAs.

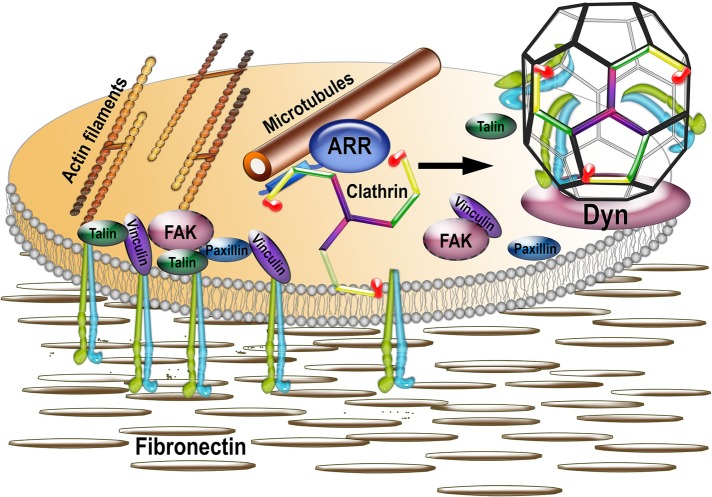

On GPCR binding, arrestins undergo a distinct conformational change (Gurevich and Gurevich, 2004) that exposes binding sites for AP2 and clathrin (Gurevich and Gurevich, 2003) to initiate receptor endocytosis. Arrestins bind microtubules via the same interface as GPCRs (Hanson et al., 2007). Although the conformations of GPCR- and microtubule-bound arrestins differ (Hanson et al., 2006), AP2- and clathrin-binding sites are exposed in both cases by virtue of similar release of the arrestin C-tail (Hanson et al., 2006, 2007). Thus it is entirely possible that arrestins provide the link between microtubules and integrin endocytosis by recruiting clathrin to FAs, thereby promoting integrin internalization. Our data strongly suggest that this is the case: arrestin mutants that do not bind clathrin fail to rescue the DKO phenotype (Figure 6), suggesting that the ability of arrestins to regulate FA disassembly is dependent on their interaction with clathrin. In addition, clathrin dynamics near FAs is also impaired in the absence of arrestins, and clathrin association with microtubules is severely reduced in DKO cells (Figure 7). Collectively these data suggest that the role of arrestins in FA disassembly is to link microtubules and clathrin, which is essential for endocytic machinery to be properly targeted to FAs to internalize integrin (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8:

Model of the mechanism of focal adhesion disassembly. Focal adhesions are multiprotein complexes organized around clustered active integrins that bind extracellular matrix (shown as fibronectin). FAs are connected to actin filaments and include numerous structural and signaling proteins, such as talin, vinculin, paxillin, focal adhesion kinase (FAK), and so on. FAs are very dynamic, and their disassembly is facilitated by the proximity of microtubules and triggered by clathrin-dependent internalization of integrins. Our data suggest that nonvisual arrestins, known to interact with both microtubules and clathrin, serve as a link between the two, being delivered together with associated clathrin by microtubules to FAs. The delivery of arrestin-bound clathrin to FAs facilitates integrin internalization via clathrin-coated pits (with the help of dynamin, which pinches coated vesicles off of the membrane) and thus FA disassembly.

Our data reveal a completely novel function of arrestins: they directly affect FA disassembly and cell migration, and this function requires both nonvisual arrestins but does not involve their binding to receptors. Thus nonvisual arrestins regulate cell spreading and migration via FA dynamics. Our results strongly suggest that nonvisual arrestins, via simultaneous binding to clathrin and FA-targeting microtubules, participate in the delivery of clathrin to FAs, serving as a missing link between microtubules and FA disassembly (Figure 8).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies

Rhodamine–phalloidin (for actin staining) was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA); anti–glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), anti-HA, phospho-paxillin (Y118), monoclonal anti-Cdc42 antibodies, anti-GFP monoclonal antibody, active 9EG7 and total Hmβ1-1 CD29 β1-integrin, and monoclonal paxillin antibodies were from BD Biosciences (Palo Alto, CA); rat immunoglobulin G (IgG) a,κ and hamster IgG isotype controls were from Biolegend (San Diego, CA). Monoclonal rat from Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Indianapolis, IN) or monoclonal rabbit (from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) anti-HA antibody was used for cell staining; antibodies against mouse FAK, phospho-FAK (Y397), vinculin, and α-tubulin were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Mouse monoclonal pan-arrestin F4C1 antibody recognizing epitope DGVVLVD in the N-domain was a generous gift of L. A. Donoso (Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia, PA). Arrestins were detected with arrestin-2-specific (1:6000; Mundell et al., 1999) or arrestin-3-specific (1:700; Orsini and Benovic, 1998) affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibodies. Total integrin antibody M-106 for Western blot was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Cell culture, transfection, and retroviral infection of cells

Arrestin DKO and WT MEF cell lines (a gift from R. J. Lefkowitz, Duke University, Durham, NC; Kohout et al., 2001) were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were retrovirally infected using genes inserted into pFB murine retrovirus vector (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA) transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) into Phoenix cell line. FuGENE HD (Promega, Fitchburg, WI) (1:3 DNA:lipid) or Lipofectamine 2000 (1:2.5 DNA:lipid) was used to transfect cells in some cases.

Protein preparation and Western blotting

Cells were lysed in Lysis solution (Ambion, Austin, TX) or 1% SDS lysis buffer and boiled for 5 min at 95°C. Protein concentration was measured with Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The protein was precipitated with nine volumes of methanol, pelleted by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min at room temperature), washed with 90% methanol, dried, and dissolved in SDS sample buffer at 0.5 mg/ml. Equal amounts of protein were analyzed by reducing SDS–PAGE and Western blotting onto Immobilon-P (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Triton X-100 (TBST) and incubated with appropriate primary and then secondary antibodies coupled with horseradish peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) in TBST with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Bands were visualized with SuperSignal enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and detected by exposure to x-ray film. The bands were quantified using VersaDoc and QuantityOne software (Bio-Rad).

Cell spreading and focal adhesion analysis

Serum-starved cells were plated on eight-well slides coated with 1.25 μg/ml FN or 0.1 mg/ml PDL. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.4% Triton X-100, and blocked with 2% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Most cells were stained with rhodamine–phalloidin. Rescue experiments in which DKO cells were infected to express HA-tagged arrestins were also stained with anti-HA antibody to detect expression. Images were taken on a Nikon TE2000-E automated inverted microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY) with 40× oil objective with additional 1.5 optical magnification. Focal adhesion numbers and size were quantified from confocal images taken on LSM 510 Meta Confocal (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with 40× oil objective and analyzed with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Migration assay

Cell migration analysis was performed as described (Chen et al., 2004). Transwell tissue culture inserts containing membranes with 0.8-µm pores and coated with 0.32 µg/ml FN in PBS on the underside were kept overnight at 4°C. Membranes were blocked in 1.5% BSA for 1 h at 37°C. The 24-well inserts were placed in serum-free medium, and 106 cells were seeded on the upper surface of the chamber and allowed to migrate for 4 h at 37°C. Cells that migrated were stained with 1% crystal violet, and six randomly chosen fields were counted at 200× magnification. Migration rescue experiments were performed using cells infected with bicistronic vector coexpressing arrestin and GFP or GFP alone (control). Cells were sorted for GFP expression on a FACSAria III cell sorter (BD, San Diego, CA).

Adhesion assay

Adhesion assays were performed as described (Goodwin and Pauli, 1995). The 96-well plates were coated with increasing concentrations of FN (0.01–1.25 μg/ml) and blocked with 5% milk at room temperature for 2 h. Serum-starved cells (6 × 105) were plated and allowed to adhere for 15 or 30 min. Unattached cells were removed using Percoll flotation medium (73 ml of Percoll, density 1.13 g/ml, plus 27 ml of distilled water and 900 mg of NaCl), and the remaining cells were fixed for 15 min with 25% glutaraldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich), washed with PBS, and stained with 0.5% crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich) in 20% methanol for 10 min. Plates were washed with PBS and eluted with 20% acetic acid. Absorbance was read at 595 nm. Bars represent mean absorbance ± SEM of each condition tested in triplicate.

Replating assay

Replating assays were performed by trypsinizing cells, incubating them in suspension in serum-free DMEM, and then plating serum-starved DKO and WT cells on 1.25 μg/ml FN for 0, 30, 60, and 120 min. Cells were lysed with 1% SDS lysis buffer. Levels of phosphorylated and total paxillin and FAK and total vinculin were determined in cell lysates (5 μg/lane) by Western blot.

Flow cytometry

To measure activity and surface expression of β1-integrin levels, cells incubated in Hank's balanced salt solution (Cellgro, Manassas, VA) overnight were washed with TBS (24 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl) and resuspended in 5% BSA. Cells were incubated with hamster HMβ1-1 (total integrin) antibody or hamster isotype controls. Cells were washed three times with 1% BSA in TBS and incubated for 45 min on ice with DyLight 488–conjugated goat anti-hamster (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) secondary antibody. At least 10,000 cells were analyzed using a 3 Laser LSRII machine to obtain mean fluorescence intensity values. To investigate total β1-integrin levels, equal numbers of DKO or WT cells were cultured for 2 d. Cell lysates were prepared in SDS lysis buffer after washing with PBS. Equal amounts of proteins (20 μg/lane) were analyzed by Western blot on 10% SDS–PAGE.

Cell-size rescue with clathrin-binding–deficient arrestins

DKO MEFS were transfected with HA-tagged WT or CBD mutants of arrestin-2 or -3 (with corresponding clathrin-binding sites LIEL and LIEF mutated to AAEA) and replated onto four-chambered glass slides 24 h posttransfection and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde 24 h later. Transfected cells were visualized by immunofluorescence with anti-HA rabbit monoclonal antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology), followed by biotinylated anti-rabbit antibody and streptavidin–Alexa 488. We found that the largest DKO MEFs that were successfully infected by retroviruses were resistant to transfection with plasmids. Cells were costained with rhodamine–phalloidin. Dual-color red-green images for cell size analysis were collected on Nikon TE2000-E automated inverted microscope with 40× oil objective using a motorized stage with 10-ìm step. All transfected cells in the view field were analyzed using Nikon NIS software. In each of three independent experiments, 50–90 cells/condition were measured.

Live-cell imaging to measure focal adhesion dynamics

Imaging to examine the FA dynamics was performed using a DeltaVision Core microscope with a Plan Apo 60× oil immersion objective lens (Applied Precision, Issaquah, WA). DKO and WT cells expressing GFP-paxillin were placed into a heated microscope chamber at 37°C for 2 h before imaging. Images were then obtained every minute and processed with 10 iterations of constrained iterative deconvolution using Softworx 5.0 (Applied Precision). Images were binned 2 × 2. Rescue experiments were performed with cells expressing arrestin-2-HA, arrestin-3-HA, and GFP.

Live-cell imaging to measure clathrin dynamics

To examine clathrin dynamics, TIRFM live-cell videos were acquired on a Nikon TE2000E microscope with Nikon TIRF2 system using TIRFM 100×/1.49 numerical aperture oil lens, Cascade 512B camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ), and IPLab software (Scanalytics, Fairfax, VA). To analyze the velocity of clathrin-coated vesicles at focal adhesions in WT and DKO MEFs coexpressing GFP-paxillin and mCherry-clathrin, 2-min double-channel TIRFM sequences (3 s/frame) were used. Analysis was limited to a region of interest (ROI) at focal adhesions defined by paxillin localization to examine clathrin velocity parameters specifically within this area. Individual clathrin-coated vesicles were automatically tracked within the ROI for the duration of the time sequence using Imaris software (Bitplane, South Windsor, CT). The average velocity of 72 clathrin tracks/condition (WT or DKO) and 1519 instantaneous velocities/condition were analyzed. These data were used to calculate average velocity and average instantaneous velocity of clathrin vesicles within the ROI, respectively.

Nocodazole washout

Serum-starved DKO and WT MEFs were grown overnight and treated with 10 μM nocodazole for 2 h to depolymerize microtubules. The drug was washed out 10 times with serum-free medium, and microtubules were allowed to repolymerize for 30, 60, and 120 min. To stain for microtubules, cells were fixed with 1% gluteraldehyde in 1× BRB80, followed by permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 in 1× BRB80 or fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, followed by treatment with 0.4% Triton X-100 in PBS before processing for immunofluorescence. Cells were stained with paxillin or α-tubulin antibodies. Focal adhesion numbers were quantified in confocal images acquired with 40× oil objective using ImageJ.

Cell fractionation

Microtubules and cytosol were separated as described (Hanson et al., 2007). Briefly, WT and DKO MEFs were incubated in DMEM with 1% serum overnight, treated with 5 μM Taxol (to stabilize microtubules) in DMEM for 2 h at 37°C, washed with 150 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid–Na, pH 7.3, and treated with 2 mM cross-linker DSP (Pierce) in the same buffer for 30 min at room temperature. Then DSP was quenched by 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5. Cells in 60-mm plates were scraped off in 0.6 ml of lysis buffer with 1% NP-40 and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Lysates were centrifuged for 5 min at 2000 rpm to remove debris. The top 0.6 ml was collected (lysate), and 2 × 250 μl of each lysate was loaded onto a 200-μl cushion of 60% glycerol and centrifuged at 90,000 rpm for 20 min at 25°C (TL120 tabletop ultracentrifuge; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Supernatant (2 × 350 μl/plate) was collected, and microtubule pellets were dissolved in 2 × 100 μl of SDS sample buffer. Aliquots of lysate, supernatant, and pellet were stored at −80°C until used.

Image and statistical analysis

Cell size analysis was from 10–15 randomly selected fields/experiment and measured for area using ImageJ or Nikon NIS software. Cells with moderate expression of either HA-arrestin were selected for cell size and focal adhesion number rescue measurements. To measure arrestin colocalization with paxillin, cells were transfected with HA-tagged arrestins and stained for HA and endogenous paxillin. Cells were imaged on an LSM 510 Meta Confocal with 40× oil objective. The Pearson coefficient was determined using Coloc2 function in ImageJ after background was corrected to eliminate nonspecificity. Focal adhesion size and number were measured from confocal images using ImageJ with qualifications for focal adhesion area: 0.5–100 μm2. Focal adhesion lifetimes were calculated using focal adhesions containing GFP-paxillin that assembled and disassembled from the leading edge of the cell. Because most data sets significantly deviated from normal distribution and thus violated assumption for parametric statistical tests, they were analyzed by nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis analysis of variance, followed by posthoc pairwise comparisons between groups of interest. To minimize the probability of type I error, Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison was applied. Focal adhesion size and lifetime distributions were compared using nonparametric Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Velocity and instantaneous velocity of clathrin particles were compared using an unpaired Student's t test. In all experiments, p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Christopher Turner for the GFP-paxillin construct. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM077561, GM081756, and EY011500 (V.V.G.); NS065868 and DA030103 (E.V.G.); CA163592, CA143069, and GM075126 (A.M.W.); GM078373 and American Heart Association Grant 13GRNT16980096 (I.K.); DK083187, DK075594, and DK383069221 and EI grant from the American Heart Association and VA Merit Review 1I01BX002196 (R.Z.); and training grants GM007628 and EY0713516 (W.M.C.). Confocal images were obtained using the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Cell Imaging Shared Resource (supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA68485, DK20593, DK58404, HD15052, DK59637, and EY08126).

Abbreviations used:

- DKO

double arrestin-2/3 knockout

- FA

focal adhesion

- FN

fibronectin

- GPCR

G protein–coupled receptor

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblast

- PDL

poly-d-lysine

- WT

wild type.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E14-02-0740) on December 24, 2014.

REFERENCES

- Ahmed MR, Zhan X, Song X, Kook S, Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV. Ubiquitin ligase parkin promotes Mdm2-arrestin interaction but inhibits arrestin ubiquitination. Biochemistry. 2011;50:3749–3763. doi: 10.1021/bi200175q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony DF, Sin YY, Vadrevu N, Advant N, Day JP, Byrne AM, Lynch MJ, Milligan G, Houslay MD, Baillie GS. b-Arrestin 1 inhibits the GTPase-activating protein function of ARHGAP21, promoting activation of RhoA following angiotensin II type 1A receptor stimulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1066–1075. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00883-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes WG, Reiter E, Violin JD, Ren XR, Milligan G, Lefkowitz RJ. b-Arrestin 1 and Gaq/11 coordinately activate RhoA and stress fiber formation following receptor stimulation. J Biol Chem. 2004;280:8041–8050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari D, Trejo J, Benovic JL, Marchese A. Arrestin-2 interacts with the ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase atrophin-interacting protein 4 and mediates endosomal sorting of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36971–36979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitman M, Kook S, Gimenez LE, Lizama BN, Palazzo MC, Gurevich EV, Gurevich VV. Silent scaffolds: inhibition of JNK3 activity in the cell by a dominant-negative arrestin-3 mutant. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:19653–19664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.358192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchas MR, Macey TA, Lowe JD, Chavkin C. Kappa opioid receptor activation of p38 MAPK is GRK3- and arrestin-dependent in neurons and astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18081–18089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513640200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Roberts R, Pohl M, Nigam S, Kreidberg J, Wang Z, Heino J, Ivaska J, Coffa S, Harris RC, et al. Differential expression of collagen- and laminin-binding integrins mediates ureteric bud and inner medullary collecting duct cell tubulogenesis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F602–611. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00015.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Burridge K. Rho-stimulated contractility drives the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:1403–1415. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezratty EJ, Bertaux C, Marcantonio EE, Gundersen GG. Clathrin mediates integrin endocytosis for focal adhesion disassembly in migrating cells. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:733–747. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezratty EJ, Partridge MA, Gundersen GG. Microtubule-induced focal adhesion disassembly is mediated by dynamin and focal adhesion kinase. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:581–590. doi: 10.1038/ncb1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge L, Ly Y, Hollenberg M, DeFea KA. A β-arrestin-dependent scaffold is associated with prolonged MAPK activation in pseudopodia during protease-activated receptor-2-induced chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34418–34426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieger B, Spatz JP, Bershadsky AD. Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:21–33. doi: 10.1038/nrm2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman OB, Krupnick JG, Santini F, Gurevich VV, Penn RB, Gagnon AW, Keen JH, Benovic JL. Beta-arrestin acts as a clathrin adaptor in endocytosis of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Nature. 1996;383:447–450. doi: 10.1038/383447a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin AE, Pauli BU. A new adhesion assay with buoyancy to remove nonadherent cells. J Immunol Methods. 1995;187:213–219. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich EV, Benovic JL, Gurevich VV. Arrestin2 and arrestin3 are differentially expressed in the rat brain during postnatal development. Neuroscience. 2002;109:421–436. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV. The new face of active receptor bound arrestin attracts new partners. Structure. 2003;11:1037–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV. The molecular acrobatics of arrestin activation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:59–112. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich EV, Gurevich VV. Arrestins are ubiquitous regulators of cellular signaling pathways. Genome Biol. 2006a;7:236. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-9-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV. The structural basis of arrestin-mediated regulation of G protein-coupled receptors. Pharm Ther. 2006b;110:465–502. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson SM, Cleghorn WM, Francis DJ, Vishnivetskiy SA, Raman D, Song S, Nair KS, Slepak VZ, Klug CS, Gurevich VV. Arrestin mobilizes signaling proteins to the cytoskeleton and redirects their activity. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson SM, Francis DJ, Vishnivetskiy SA, Klug CS, Gurevich VV. Visual arrestin binding to microtubules involves a distinct conformational change. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9765–9772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510738200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunton DL, Barnes WG, Kim J, Ren XR, Violin JD, Reiter E, Milligan G, Patel DD, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-arrestin 2-dependent angiotensin II type 1A receptor-mediated pathway of chemotaxis. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:1229–1236. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.006270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huveneers S, Danen EHJ. Adhesion signaling—crosstalk between integrins, Src, and Rho. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1059–1069. doi: 10.1242/jcs.039446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaverina I, Krylyshkina O, Small JV. Microtubule targeting of substrate contacts promotes their relaxation and dissociation. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:1033–1044. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.5.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim GH, Han JK. Essential role for b-arrestin 2 in the regulation of Xenopus convergent extension movements. EMBO J. 2007;26:2513–1526. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YM, Benovic JL. Differential roles of arrestin-2 interaction with clathrin and adaptor protein 2 in G protein-coupled receptor trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30760–30768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204528200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohout TA, Lin FS, Perry SJ, Conner DA, Lefkowitz RJ. beta-Arrestin 1 and 2 differentially regulate heptahelical receptor signaling and trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1601–1606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041608198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laporte SA, Oakley RH, Holt JA, Barak LS, Caron MG. The interaction of beta-arrestin with the AP-2 adaptor is required for the clustering of beta 2-adrenergic receptor into clathrin-coated pits. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23120–23126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell LM, Roudabush FL, Choy EW, Miller WE, Field ME, Pierce KL, Lefkowitz RJ. Activation and targeting of extracellular signal-regulated kinases by beta-arrestin scaffolds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2449–2454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041604898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald PH, Chow CW, Miller WE, Laporte SA, Field ME, Lin FT, Davis RJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-arrestin 2: a receptor-regulated MAPK scaffold for the activation of JNK3. Science. 2000;290:1574–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min J, DeFea KA. b-Arrestin-dependent actin reorganization: bringing the right players together at the leading edge. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:760–768. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.072470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundell SJ, Loudon RP, Benovic JL. Characterization of G protein-coupled receptor regulation in antisense mRNA-expressing cells with reduced arrestin levels. Biochemistry. 1999;38:8723–8732. doi: 10.1021/bi990361v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini MJ, Benovic JL. Characterization of dominant negative arrestins that inhibit beta2-adrenergic receptor internalization by distinct mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34616–34622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry SJ, Baillie GS, Kohout TA, McPhee I, Magiera MM, Ang KL, Miller WE, McLean AJ, Conti M, Houslay MD, Lefkowitz RJ. Targeting of cyclic AMP degradation to beta 2-adrenergic receptors by beta-arrestins. Science. 2002;298:834–836. doi: 10.1126/science.1074683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotnikov SV, Waterman CM. Guiding cell migration by tugging. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25:619–626. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry SK, Burridge K. Focal adhesions: a nexus for intracellular signaling and cytoskeletal dynamics. Exp Cell Res. 2000;261:25–36. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott MGH, Pierotti V, Storez H, Lindberg E, Thuret A, Muntaner O, Labbe-Jullie C, Pitcher JA, Marullo S. Cooperative regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation and cell shape change by filamin A and b-arrestins. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3432–3445. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3432-3445.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar H, Michal A, Kern RC, Kang DS, Gurevich VV, Benovic JL. Non-visual arrestins are constitutively associated with the centrosome and regulate centrosome function. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8316–8329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.062521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy SK, McDonald PH, Kohout TA, Lefkowitz RJ. Regulation of receptor fate by ubiquitination of activated beta 2-adrenergic receptor and beta-arrestin. Science. 2001;294:1307–1313. doi: 10.1126/science.1063866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small JV, Geiger B, Kaverina I, Bershadsky A. How do microtubules guide migrating cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:957–964. doi: 10.1038/nrm971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Coffa S, Fu H, Gurevich VV. How does arrestin assemble MAPKs into a signaling complex. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:685–695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806124200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb DJ, Donais K, Whitmore LA, Thomas SM, Turner CE, Parsons JT, Horwitz AF. FAK-Src signalling through paxillin, ERK, and MLCK regulates adhesion disassembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:154–161. doi: 10.1038/ncb1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao K, McClatchy DB, Shukla AK, Zhao Y, Chen M, Shenoy SK, Yates JR, Lefkowitz RJ. Functional specialization of beta-arrestin interactions revealed by proteomic analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12011–12016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704849104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.