Abstract

Solutions of hypochlorous acid (HOCl) decay over time. This decay indicates the necessity for methods and reagents for the routine measurement of this oxidant. 2-Nitro-5-thiobenzoate is commonly used to measure HOCl concentrations. The following article describes a method for the preparation of 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate that is stable for at least three months. This method relies on the partial rather than full reduction of 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) and the resulting equilibrium between the substrate and product.

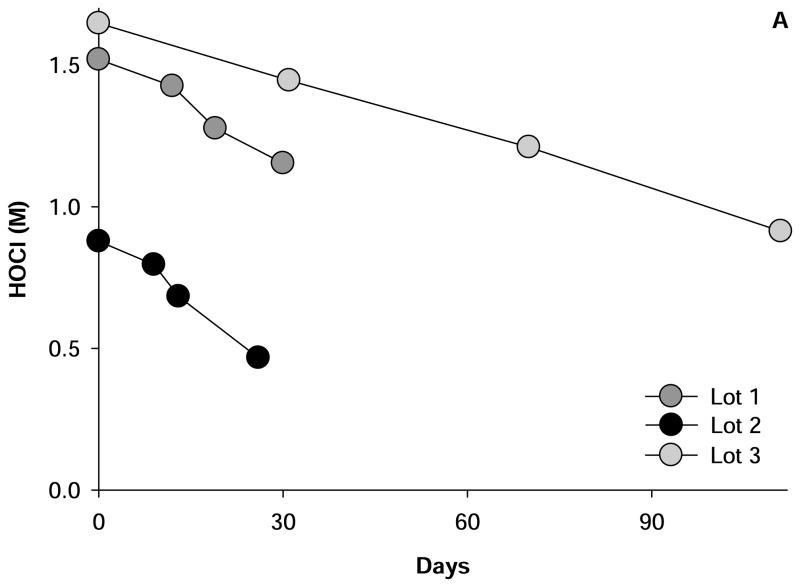

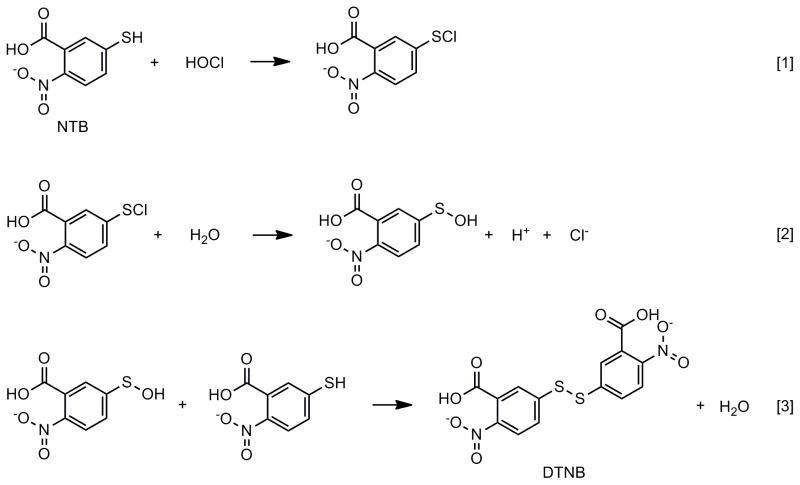

Commercially available solutions of HOCl decay in content over time (Fig. 1A). The increasing use of HOCl in research indicates the need for convenient methods to measure this oxidant (≥ 70 articles per year with HOCl or sodium hypochlorite as a major subject, were published from 2010 on). HOCl reacts rapidly with thiol moieties [1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6], and in our experience, the oxidation of 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate (NTB) by this oxidant provides the most robust estimates of the latter’s concentration [7]. This measurement relies on the oxidation of two moles of NTB per mole of HOCl as shown in Fig. 2. Loss of NTB is readily quantified in terms of its extinction coefficient of 14,140 M−1.s−1 at 412 nm [8] and application of the Beer-Lambert expression (i.e. optical density = concentration x path length (cm) x extinction coefficient). The measurement of HOCl by this method, therefore, relies on the availability of NTB.

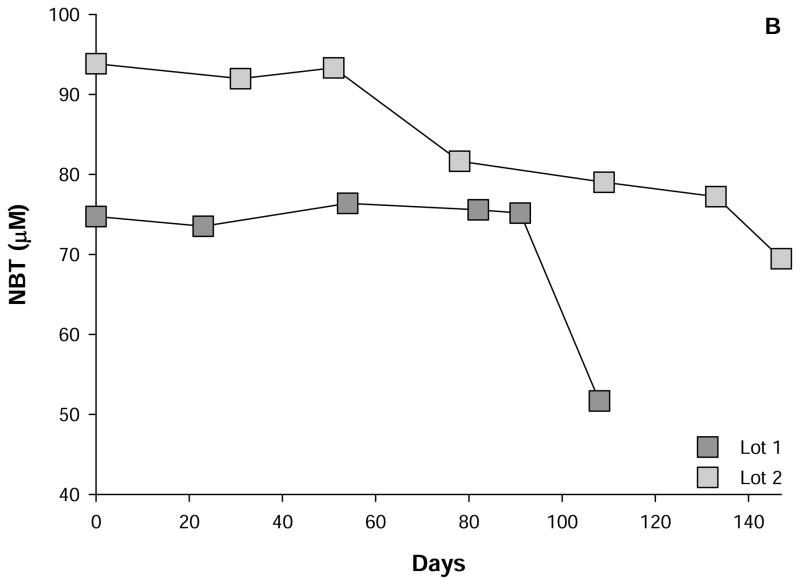

Figure 1. Stability of reagent HOCl and NTB.

Shown are the changes in the concentration of three lots of reagent HOCl (A) and two lots NTB (B) over time. HOCl was supplied by the Sigma-Aldrich Company and stored at 4°C as per the supplier’s intruction. NTB was prepared as described in the text and a fresh aliquot was measured at each time. The mean values of several determinations at each time point that did not vary by more than 5% of the mean are depicted.

Figure 2.

Oxidation of NTB by HOCl

NTB is typically generated by the reduction of Ellman’s reagent (5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid): DTNB) by sodium borohydride (NaBH4) (e.g. [9]). The extent of this reduction is variable regardless of the source of the NaBH4 and reflects the highly reactive nature of the hydride. To counter this variability, we routinely determined the amount of hydride added to the solutions of DTNB empirically. DTNB can be dissolved to a final concentration of 1.5 mM in an unbuffered solution of 50 mM monobasic sodium phosphate at room temperature. This solution is stable for several months at 4°C. Solutions of NaBH4 decompose rapidly and consequently the hydride was prepared immediately prior to its use as a 100 mM solution in H2O on ice. NaBH4 was then titrated into a mixture of 60 μL 1.5 mM DTNB in 50 mM sodium monobasic phosphate and 840 μL sodium dibasic phosphate (final pH = 7.9) in a 1 mL cuvette to a final optical density of 1.414 (i.e. 100 μM NTB) was obtained. The amount of NaBH4 was then scaled to reduce six parts of 1.5 mM DTNB in 50 mM sodium monobasic to 84 parts phosphate sodium dibasic phosphate in the volume of choice (e.g. 1 L). Prior to this determination, the DTNB-containing solution was transferred to a suction flask and kept on ice. Suction was applied immediately following the addition of the NaBH4 and continued till no more bubbles were evident in the solution, a period of approximately four hours. The solution was also stirred throughout and kept dark. At the end of this procedure, the contents of the flask were divided into aliquots and stored at −80°C. Most protocols stipulate acidifying the NTB solution prior to storage to slow thiol:disulfide interchange (e.g. [9; 10]). The amounts of NaBH4 and DTNB used in the above procedure would ensure the production of ~100 μM NTB with ~50 μM DTNB remaining. We reasoned that any molecule of NTB undergoing thiol:disulfide exchange under our conditions, would release a molecule of NTB from DTNB and therefore maintain the concentration of this thiol. The alkaline conditions of our degassed preparation would also slow the dissolution of atmospheric oxygen, and thereby, stem the oxidation of the NTB to either a sulfoxide or sulfone. NTB produced in this manner was stable for at least three months (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 1B, the concentration of NTB produced by this protocol was less than the expected concentration of 100 μM. This difference is likely due to the aging of the sodium borohydride during the titration process and the amplification of errors when scaling from 0.9 mL to 1 L volumes. Even so, thawed aliquots of the NTB, prepared as described above, are ready for the determination of HOCl diluted 100 times in ice-cold H2O. This determination becomes a simple matter of applying the Beer-Lambert expression to the difference in optical densities of NTB prior to and after reaction with 1 to 2 μL diluted HOCl. In summary, this procedure produces NTB for the convenient and routine measurement of reagent HOCl.

Acknowledgments

These studies were funded by RO3-NS074286 and the Theresa Pantnode Santmann Foundation Award.

List of Abbreviations

- DTNB

5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid)

- NTB

2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- 1.Cook NL, Pattison DI, Davies MJ. Myeloperoxidase-derived oxidants rapidly oxidize and disrupt zinc-cysteine/histidine clusters in proteins. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:2072–2080. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakamura M, Shishido N, Akutsu H. Reactions of 1-methyl-2-mercaptoimidazole with hypochlorous acid and superoxide. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2004;57:S34–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prutz WA. Hypochlorous acid interactions with thiols, nucleotides, DNA, and other biological substrates. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;332:110–120. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peskin AV, Winterbourn CC. Kinetics of the reactions of hypochlorous acid and amino acid chloramines with thiols, methionine, and ascorbate. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:572–579. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peskin AV, Winterbourn CC. Taurine chloramine is more selective than hypochlorous acid at targeting critical cysteines and inactivating creatine kinase and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stacey MM, Peskin AV, Vissers MC, Winterbourn CC. Chloramines and hypochlorous acid oxidize erythrocyte peroxiredoxin 2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1468–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeitner TM, Xu H, Gibson GE. Inhibition of the alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex by the myeloperoxidase products, hypochlorous acid and mono-N-chloramine. J Neurochem. 2005;92:302–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collier HB. Letter: A note on the molar absorptivity of reduced Ellman’s reagent, 3-carboxylato-4-nitrothiophenolate. Anal Biochem. 1973;56:310–311. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(73)90196-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aune TM, Thomas EL. Accumulation of hypothiocyanite ion during peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation of thiocyanate ion. Eur J Biochem. 1977;80:209–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vissers MC, Winterbourn CC. Oxidation of intracellular glutathione after exposure of human red blood cells to hypochlorous acid. Biochem J. 1995;307(Pt 1):57–62. doi: 10.1042/bj3070057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]