Abstract

The rapid development of nanotechnology will inevitably release nanoparticles (NPs) into the environment with unidentified consequences. In addition, the potential toxicity of CeO2 NPs to plants, and the possible transfer into the food chain, are still unknown. Corn plants (Zea mays) were germinated and grown in soil treated with CeO2 NPs at 400 or 800 mg/kg. Stress related parameters, such as: H2O2, catalase (CAT) and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity, heat shock protein 70 (HSP 70), lipid peroxidation, cell death and leaf gas exchange were analyzed at 10, 15, and 20 days post germination. Confocal laser scanning microscopy was used to image H2O2 distribution in corn leaves. Results showed that the CeO2 NP treatments increased accumulation of H2O2, up to day 15, in phloem, xylem, bundle sheath cells, and epidermal cells of shoots. The CAT and APX activities were also increased in the corn shoot, concomitant with the H2O2 levels. Both 400 and 800 mg/kg CeO2 NPs triggered the up regulation of the HSP 70 in roots, indicating a systemic stress response. None of the CeO2 NPs increased the level of thiobarbituric acid reacting substances, indicating that no lipid peroxidation occurred. CeO2 NPs, at both concentrations, did not induce ion leakage in either roots or shoots, suggesting membrane integrity was not compromised. Leaf net photosynthetic rate, transpiration, and stomatal conductance were not affected by CeO2 NPs. Our results suggest that the CAT, APX and HSP 70 might help the plants defend against CeO2 NPs induced oxidative injury and survive NP exposure.

Keywords: CeO2 NPs, Zea mays, H2O2, stress enzymes, cell death, photosynthesis

The field of nanotechnology opens up potential novel applications for agriculture. Large amounts of nanoparticles (NPs) are administered to crops as novel delivery tools for fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides.1 However, the toxicity of NPs to plants has to be considered before their wide application in agriculture. Previous studies evaluated the phytotoxicity of various NPs to plants by measuring some growth-related parameters, such as germination rate, root elongation and biomass production.2,8 Lopez et al., for the first time, demonstrated the effects of CeO2 NPs to soybean (Glycine max) at the gene level.6 More recently, Khodakovskaya et al.9 discovered that multi-walled carbon nanotubes induced up-regulation of the stress-related genes in tomato leaves and roots. Atha et al. showed that copper oxide NPs induced DNA damage in radish (Raphanus sativus) and ryegrass (Lolium perenne and Lolium rigidum).10 There is an extensive interest in investigating whether the NPs can induce stress response in edible plants and how the plants tolerate the stress induced by NPs. Currently, the scientific community is in need of deep insight into the interaction of NPs with terrestrial plants.

CeO2 NPs are one of the 13 engineered nanomaterials included in the list of priority for immediate testing by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).11,12 CeO2 NPs are widely used as polishing material, additive in glass and ceramic, fuel cell materials, in agricultural products, and automotive industry. 13,14 Reports indicate that CeO2 NPs are toxic to inhabitants of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems like bacteria, green algae, fish, and soybean plants (Glycine max).6, 13-16 Corn is the most widely grown grain crop in the Americas, with 332 million metric tons harvested annually in the United States.17 The fate and response of corn plant grown in NPs contaminated soil are unknown. Asli and Neumann,18 reported that cell wall pores in corn primary roots have a mean diameter of 6.6 nm. Thus, particles, with diameter far greater than the cell wall pore dimensions, will not penetrate the root epidermal cell walls. Our previous study also showed that a very small percentage of CeO2 NPs could be transferred from corn roots to shoots.19 This suggests that CeO2 NPs could produce a low impact on the above ground plant parts. However, there is evidence that the attached NPs on root surfaces inhibited the water transpiration to the leaves.18 This indicates that NPs can cause impact on the upper part tissues, even though the main accumulation is localized in roots. Therefore, it would be very important to determine the stress in the upper plant parts, where there is low direct interaction with the CeO2 NPs.

Tan et al. 20 showed that multi-walled carbon nanotubes triggered reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in rice (Oryza sativa) cell lines. Shen et al. also showed the over accumulation of H2O2 in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and rice (Oryza sativa) leaf protoplasts induced by single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs).21 The NPs induced ROS generation and its potential damage to proteins and lipids in tissues have been reported less. In this study, corn plants were germinated and grown for 20 days in soils spiked with CeO2 NPs at 0, 400, and 800 mg/kg levels. The uptake of Ce in corn root and shoot tissues during 20 days was determined by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES). The stress related responses, e.g., H2O2, antioxidant enzyme, heat shock protein 70 (HSP 70), lipid peroxidation and cell death were determined every five days during growth. Additionally, localization of H2O2 was visualized by using a fluorescence probe and confocal microscopy. This study is the first report, to our knowledge, which describes the stress response of edible plants exposed to CeO2 NPs. Here, we demonstrated that CeO2 NPs induced oxidative stress, while CAT and APX play important roles to combat the stress. Oxidative damage did not occur due to the defensive system. These findings greatly enhance the understanding of the interaction of CeO2 NPs with crop plants.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

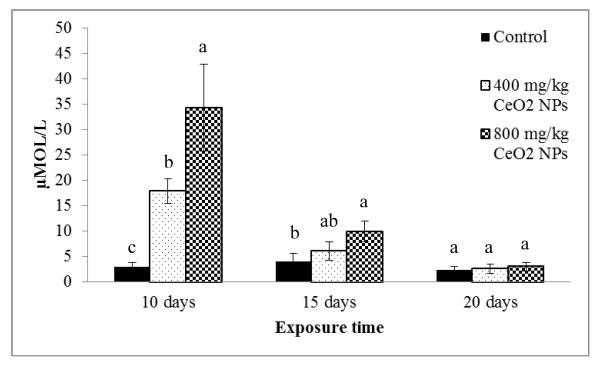

H2O2 Production and Localization

CeO2 NPs have a large hydrodynamic size (2124 ± 59 nm) in soil solution.19 Large sized CeO2 NP aggregates hardly penetrate root epidermis cell walls of corn plants. In addition, negative charged CeO2 NPs (−22.8 mV) may be retained by cation exchange sites of root cell walls restricting their transport to shoots. Our previous study showed a ratio of Ce shoot/Ce root close to 0.1, indicating that most of the CeO2 NPs accumulated in root tissues.19 This could indicate low toxicity to the above ground parts. However, over production of H2O2 was observed in shoots at the early stage of growth. As shown in Figure 1, both 400 and 800 mg/kg CeO2 NP treatments induced H2O2 over-accumulation in shoots at ten days. The H2O2 concentrations in shoots treated with 400 and 800 mg/kg CeO2 NPs were five and ten times higher compared to control, respectively (p≤ 0.05). These results indicate that corn plants suffered from a concentration-dependent oxidative stress at the early growth stage. As the exposure time increased, the generation of H2O2 gradually decreased in all CeO2 NP treated plants and no over production was observed at 20 days (Figure 1). The H2O2 expression pattern suggested that the plants may initiate an adaptive response to tackle the over expressed H2O2, that could, otherwise, cause further damage. Although a previous report showed increased ROS production in Arabidopsis and in rice following SWCNT treatments,21 a time course following the treatment was not performed, which might have missed an important adaptive responses. In the present study, it is very likely that an earlier response occurred before the tenth day; however, because the shoots biomass was too small to be collected at day five, the earlier response could not be recorded.

Figure 1.

H2O2 production in shoots of corn plants germinated and grown in soil treated with CeO2 NPs at 0, 400, and 800 mg/kg. All data show the means of a total of three replicates (nine plants/replicate). Error bars represent standard deviation. Means with same letters, within each exposure time, are not significantly different (Tukey’s HSD multiple comparison at p ≤ 0.05).

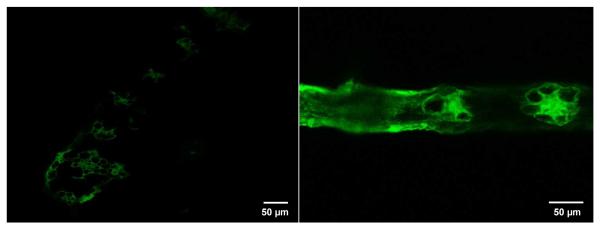

The knowledge about the contribution of different cells to the accumulation of H2O2 is important in order to gain deeper insights into the cellular response of plants to adverse conditions.22 Confocal laser scanning microscopy was used to image H2O2 distribution in corn plant shoots. As previously shown, the production of H2O2 at 800 mg/kg was highest at ten days; thus, only ten-day plants’ shoots were collected for H2O2 localization. The representative transversal sections of control and CeO2 NPs treated corn leaves incubated with DCF-DA were imaged by confocal microscope (Figure 2 A and B).

Figure 2.

Confocal microscopy imaging of H2O2 production in shoot cross sections of corn plants germinated and grown for 10 days in soil treated with CeO2 NPs at 0 and 800 mg/kg. DCF-DA fluorescence distribution in cross section of control (A) and (B) CeO2 NPs treated corn plants.

The green fluorescence signals, which represent the presence of H2O2, were found to be much brighter in the leaves of CeO2 NP treated plants, compared to control. This is consistent with the H2O2 concentration data (Figure 1). In control leaves, most of the H2O2 was localized at bundle sheets (Figure 2 A), while in NP treated plants the H2O2 was in epidermis cells, bundle sheet, and parenchyma (Figure 2 B). H2O2 in control leaves was associated to cell differentiation and elongation.23

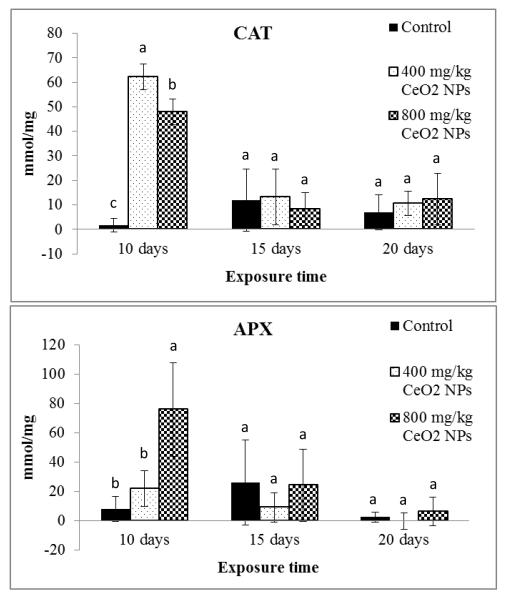

H2O2-Scavenging Enzyme Activity

The enzymes CAT and APX are known to be involved in the detoxification of H2O2 by converting the H2O2 to water and oxygen.21 We determined the dynamic changes of both enzymes at different growth stages. As shown in Figure 3, CAT activity was significantly up-regulated by CeO2 NPs at ten days (p≤ 0.05). The CAT activity, in shoots of plants treated with 400 and 800 mg/kg CeO2 NPs, were 39 and 30 times higher than the control, respectively. It was noted that CAT activity was lower at 800 mg/kg CeO2 NPs than at 400 mg/kg CeO2 NPs. This may indicate that high levels of NPs lead to inhibition of CAT enzyme activity. As time passed, CAT activity declined. At 15 days, the over production of CAT activity was not observed.

Figure 3.

Antioxidant enzyme CAT and APX activity in of corn plants germinated and grown in soil treated with CeO2 NPs at 0, 400, and 800 mg/kg. All data show the means of a total of three replicates (nine plants/replicate). Error bars represent standard deviation. Means with same letters within each exposure time are not significantly different (Tukey’s HSD multiple comparison at p ≤ 0.05).

Similar to CAT, the APX activity was also up-regulated at ten and 15 days. APX activity, in shoots of plants treated with 400 and 800 mg/kg CeO2 NPs, was three and ten times higher than the control, respectively; the difference at 800 mg/kg was statistically significant compared to control (p≤ 0.05). High concentrations of CeO2 NPs lead to high levels of APX activity. CAT and APX activities showed a concomitant decrease in corn shoots with a decrease in H2O2 levels, which suggests that corn plants increased the production of both enzymes in order to degrade the excess of H2O2. This explains why at 20 days the over production of H2O2 in shoots was not observed. CAT and APX activity in shoots may serve as a biomarker for CeO2 NP stress in corn plants.

Result from ICP-OES showed that the Ce concentration in corn shoots was very low at ten days (not detected and 4.6 mg/kg, respectively, for 400 and 800 mg/kg treatments) (Figure S1 in Supporting Information), where the highest H2O2 production was found (18 and 34 μmol/L, respectively). Moreover, at day 20, the concentration of Ce in shoots was the highest (1 and 20 mg/kg, respectively, for 400 and 800 mg/kg treatments), while the H2O2 levels were similar to the control levels (2.6 and 3.0 μmol/L). This suggests the oxidative stress observed in shoot tissues was not caused, directly, by the accumulated CeO2 NPs. The oxidative stress observed in shoots must be related to the interaction of NPs with roots. There is evidence that the attached NPs in root surface inhibited the water transport affecting the leaves’ responses.18 There are other possible mechanisms here as well (other than water transport) such as altered hormone production/distribution and impacts on endophytes. The changes in enzyme activities in shoots suggested that the roots NPs interactions also affected the physiology of the shoots. As shown above, the average size of CeO2 NP aggregates in soil solution was around 2 μm; thus, the toxicity probably was produced by the interaction between the NP aggregates and the root, not because of the accumulation in shoots.

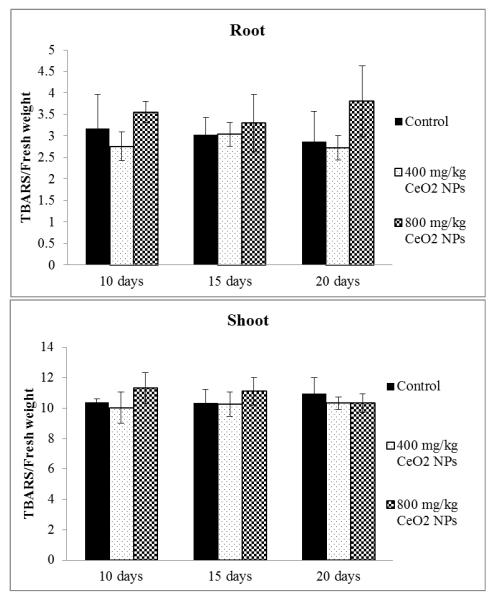

Lipid Peroxidation

To test if H2O2 accumulation causes membrane damage, lipid peroxidation in corn roots and shoots was analyzed. H2O2 acts as a signaling molecule and, at the same time, it has high permeability across membranes and can cause membrane damage. Whether H2O2 will act as a signaling or damaging molecule depends on the delicate equilibrium between its production and scavenging.24 As shown in Figure 4, none of the treatments produced significant changes in TBARS concentrations, in both roots and shoots.

Figure 4.

Biochemical detection of lipid peroxidation caused by CeO2 NPs in roots and shoots of corn plants germinated and grown for 20 days in soil treated with CeO2 NPs at 0, 400, and 800 mg/kg. All data show the means of a total of three replicates (nine plants/replicate). Error bars represent standard deviation. Means with same letters within each exposure time are not significantly different (Tukey’s HSD multiple comparison at p ≤ 0.05).

It is known that ROS molecules can rapidly attack lipids leading to irreparable membrane damage. At ten days, H2O2 was over produced in shoots of NP treated plants; however, lipid peroxidation was not induced. Considering both CAT and APX activity data, it is concluded that both antioxidant enzymes successfully eliminate the excess of H2O2 avoiding the potential lipid damage caused by the CeO2 NPs.

Heat Shock Protein 70

Heat shock proteins act as molecular chaperones in normal protein folding and assembly, but may also function in the protection and repair of proteins under stress conditions.25,26 There have been numerous reports of an increased HSP expression in plants, in response to heavy metal stress. Recently, there was a report about increased HSP90 gene expression in tomato plants, in response to CNTs stress9.

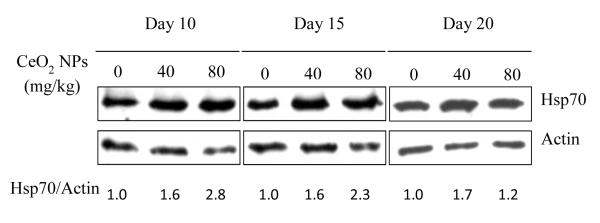

In corn shoots, the expression of HSP70 did not show differences due to the change in concentration of CeO2 NPs, at all exposure times (0 to 20 days) (Figure S2 in the Supporting Information). Interestingly, in roots, the western blot analysis showed that CeO2 NPs induced up-regulation of HSP70 (Figure 5). At all the exposure times, HSP70 levels in roots treated with either 400 or 800 mg/kg CeO2 NPs were significantly higher than control (p≤ 0.05). Wang et al.26 reported that HSPs can play a crucial role in protecting plants against stress by re-establishing normal protein conformation, and thus, cellular homeostasis. This suggests that the plants might initiate an adaptive process to the adverse conditions by up-regulation of HSP70. In addition, it was noted that even on day 20, at a time when the over produced H2O2 had been eliminated by the CAT and APX, the production of HSP70 was still higher compared to control. Agarwal et al.27 showed that, in rice, HSP101 was produced during the post-stress phase, implying its role in the plant’s recovery to normal conditions after stress. Our data suggest that the HSP70 protects the plants from potential damage, which might be caused by excessive deposition of NPs/NP aggregates. The mechanisms underlying the protection wait for further investigation.

Figure 5.

Western-blot results of the expression level of HSP 70 in roots of corn plant after 10, 15, and 20 days of growth in soil treated with CeO2 NPs at 0, 400 and 800 mg/kg. Equal amounts of total root proteins (20 μg) were loaded in each lane and resolved by SDS-PAGE, which was subsequently transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. HSP 70 was probed with rabbit anti-cytoplasmic HSP 70 antibody and visualized by goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Relative abundance of HSP 70 was normalized to the expression level of actin. The ratio of HSP 70 to actin was measured by densitometry software LABWORKs.

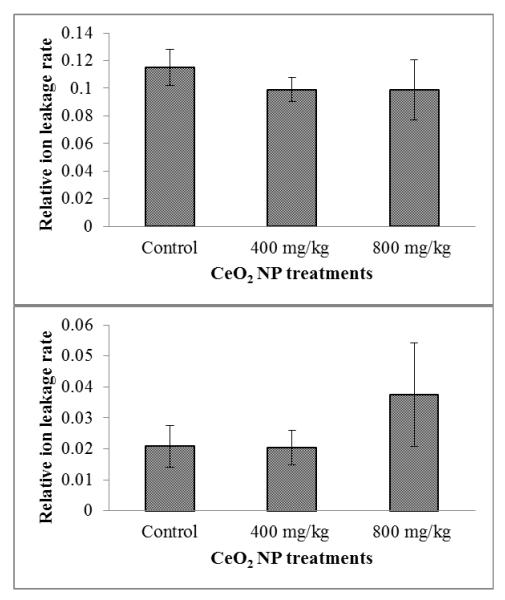

Detection of Cell Death (Plasma Membrane Integrity)

To test if the H2O2 accumulation leads to oxidative damage and cell death, we examined the relative ion leakage (plasma membrane integrity) in 20-day old corn roots and shoots. Relative ion leakage rates are shown in Figure 6. The levels of ion leakage in corn plants treated with 400 and 800 mg/kg CeO2 NPs were similar with control, indicating no membrane damage was induced, even when the NPs accumulated in the internal part of the cell wall, close to the membranes (see TEM in Figure S3 in the Supporting Information). This data is consistent with lipid peroxidation data. Very likely, CAT and APX protect the membrane from damage by scavenging the over produced H2O2. On the other hand, HSP 70 may also serve as a protective mechanism for membrane integrity. There have been several evidences that suggests HSP may be associated with a protective role on membranes. In soybean seedlings the accumulation of HSP15 in membrane fractions coincides with a decrease of solute leakage after heat-stress treatment.28 Neumann et al. reported that HSP70 could be involved in the protection of membranes against cadmium damage.29 They found that, in soybean treated with CdSO4 (10−3 M), a considerable amount of HSP70 was bound to membranes; perhaps connected with the formation of complexes between heavy metals and proteins and the resulting denaturation.

Figure 6.

Relative ion leakage of corn roots germinated and grown for 20 days in soil treated with CeO2 NPs at 0, 400, and 800 mg/kg. Data are means of a total of three replicates (nine plants/replicate). Error bars stand for standard deviation. Means with same letters within each exposure time are not significantly different (Tukey’s HSD multiple comparison at p ≤ 0.05).

There is evidence that carbon NPs induced the loss of membrane integrity in onion epidermis cells.30 The loss of membrane integrity was considered a result of mechanical damage exerted by C60(OH)20 aggregation instead of ROS.30

Photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is one of the physiological processes most sensitive to environmental stresses.31 Also, the capacity for the plant to maintain normal photosynthesis rate, under stressful conditions, can be a good indicator of plant adaptability.32 Gas exchange (net photosynthetic rate, transpiration, and stomatal conductance) of corn leaves were measured 20 days after sowing. Results showed (Table 1) no significant differences in gas exchanges between control and CeO2 NP treated plants (Table 1), indicating that at the concentrations tested and the growth stage evaluated, corn plants tolerated the CeO2 NPs.

Table 1.

Leaf net photosynthetic rate (Pn), transpiration (E), and stomatal conductance (gs) of corn plants germinated and grown for 20 days in soil treated with CeO2 nanoparticles at 0, 400, and 800 mg/kg.

| CeO2 NPs | Pn (μmol·m−2·s−1)z | E (mmol·m−2·s−1) | gs (mmol·m−2·s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.9 ± 0.2 ay | 1.6 ± 0.1 a | 93.8 ± 9.8 a |

| 400 | 3.0 ± 0.1 a | 1.4 ± 0.2 a | 83.6 ± 12.9 a |

| 800 | 3.2 ± 0.2 a | 1.4 ± 0.1 a | 81.5 ± 7.1 a |

Data are means ± standard error of five replicates, two plants per replicate, one leaf per plant.

Means followed by same letter are not significantly different among treatments by Tukey’s HSD multiple comparison at p ≤ 0.05.

CONCLUSIONS

The safe use of NPs in agriculture requires a thorough understanding of the interaction of NPs and edible plants. In the work presented herein, we grew corn in soil spiked with CeO2 NPs. These NPs are some of the most commonly used NPs and their environmental background level is expected to be continuously increasing. Utilizing multiple stress related assays, we found overproduction of H2O2 and up-regulated HSP 70, which demonstrated that CeO2 NPs caused stress response in corn plant. Even though we found a stress response, no loss of membrane integrity was observed. In addition, the corn photosynthetic pathways were not affected by CeO2 NPs. Our results indicate that corn plants have protective mechanisms to adapt to toxicity induced by CeO2 NPs. A long term observation, especially, the whole life cycle, is still needed in order to obtain a comprehensive evaluation of the impact of CeO2 NPs on corn plants.

METHODS

Nanoparticles Characterization

CeO2 NPs (Meliorum Technologies, primary size of 10 ± 1 nm) were obtained from the University of California Center for Environmental Implications of Nanotechnology (UC CEIN). The hydrodynamic size of CeO2 NPs in soil solution was 2124 ±59 nm, and zeta potential of −22.8 ± 4.5 mV. Size and zeta potential of the NPs in suspensions were measured using a Malvern Zetasizer (Nano-ZS 90, Malvern). All the size and zeta potential determinations were performed in CeO2 NP suspensions at 25 mg/L soil solution with sonication time of 30 min. Soil solution was extracted as 1:10 soil/deionized water at a pH of 8.2.

Exposure of Corn Plant to Soil Spiked with CeO2 NPs

Magenta boxes were filled out in triplicate with 250 g soil and sown with nine corn kernels (Golden variety, Del Norte Seeds Company, El Paso, TX) to have enough biomass for determinations. The nine corn plants from each box were used in each assay. Soil was collected from Fabens, TX and classified as sandy loam soil, with the following physicochemical properties: clay 3.73%, silt 12.15%, sand 84.10%, organic matter content 0.04% and pH 7.9. Triplicate CeO2 NP suspensions were sonicated for 30 min and applied to the soil to make final concentrations of 400 and 800 mg NPs/kg soil. Plants were grown for 20 days in an environmental growth chamber at 25 °C, 16/8 h light/dark cycle and 65% humidity.

ICP-OES Analysis of Ce in Corn Tissues

The corn shoots were harvested at 10, 15 and 20 days and were analyzed for Ce content by ICP-OES (Perkin-Elmer Optima 4300 DV, Shelton, CT). Prior to ICP analysis, shoots samples were digested with concentrated plasma-pure HNO3 and H2O2 (30%) (1:4) using a microwave acceleration reaction system (CEM Corp; Mathews, NC). Certified Reference Material (Peach leaves, NIST 1547) was processed as samples and the Ce recovery rate was 100.82 ± 0.48.

H2O2 Measurement

H2O2 concentration in crude extracts from fresh corn shoots was determined by spectrofluorometry, according to the method described by Gay and Gebicki.33 Fresh seedlings (500 mg) were ground in liquid nitrogen and suspended in 4 mL of 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8). The mixture was added with appropriate volumes of reagents to give a final concentration of 25 mM H2SO4, 100-150 μM xylenol orange, and 100-250 μM ferrous iron (ferrous ammonium sulfates) in a volume of 2 mL. After 30 min in the dark, the absorbance was measured at 560 nm, with XO/Fe2+ as blank.

Visualization of H2O2 in Tissues

Fluorescent probes 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF DA) (Sigma Aldrich) were used for in vivo observation of the distribution of H2O2 in different cells of the corn plant tissue.34 DCF-DA is a cell-permeant indicator for ROS that is nonfluorescent until it is oxidized to the brightly fluorescent DCF in presence of H2O2.35. Corn leaves segments (2 cm) were embedded in 10 μM DCF-DA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer for 30 min at 37°C in darkness. Then, the segments were washed three times in the same buffer for 15 min. Three leaf segments, one segment per plant, were sectioned at 10 μm using a Minotome plus cryostat (Triangle Biomedical Science, Durham, NC). DCF-DA green fluorescence (485 nm excitation, 530 nm emission) was observed with a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss, New York, NY), equipped with a 10X objective and assisted with ZEN 2009 software (Zeiss, New York, NY).

Catalase and Ascorbate Peroxidase Assay

The catalase (CAT) enzyme activity was assayed according to Gallego et al.36, with minor modifications. Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity was determined according to Murgia et al.37, with minor modifications. All the operations were performed in a cold room at 0 ~ 4°C. Specific details regarding the assay of CAT, and APX can be found in the Supporting Information (SI).

Estimation of Lipid Peroxidation

The degree of lipid peroxidation in plants was determined following the method of Heath and Packer.38 Fresh root/leaf (300 mg) was ground in 2 mL of 0.1% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) using mortar and pestle and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min. A 1 mL of the supernatant was added with 1 mL of TCA (20%) containing 0.5% (w/v) thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and 100 μL butylated hydroxyltoluene (BHT, 4% in ethanol). The mixture was heated at 95°C for 30 min, then quickly cooled in an ice bath and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 532 nm. The unspecific turbidity of the sample was measured at 600 nm and subtracted with the absorbance at 532 nm. A total of 0.25% TBA in 10% TCA served as blank. The concentration of lipid peroxides together with the oxidatively modified proteins of the plants were quantified and expressed as total TBARS, an index of lipid peroxidation, in terms of nmol g−1 fresh weight using an extinction coefficient of 155 mM−1 cm−1.

Protein Extraction and Western-blot Analysis of HSP 70

Corn plants were removed from soil at day 10, day 15 and day 20 and were thoroughly washed with tap water followed by deionized water. The tissues were immediately stored at −80°C for later use. One gram of frozen root or shoots tissues were ground in liquid N2 and extracted with 2 ml QB buffer (SI). The extracted solutions containing protein samples were centrifuge for 20 min at 16,000 g at 4 °C. The supernatants were carefully transferred to 1.5 ml eppendorf tubes. Protein quantitation was performed by BCA protein assay kit (Bio-rad).

Protein quantitation was performed according to Nieto Sotelo et al. with some modifications.39 Specifically, twenty micrograms of protein were separated in 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels and wet transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and then blocked for 1 h at room temperature in Tris-buffered saline with Tween (TBS-T) [50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20] buffer containing 5% nonfat milk. Membranes were then incubated with the primary antibodies rabbit anti-heat cytoplasmic shock protein 70 (1:3000), rabbit anti-rubisco (1:10,000) or mouse anti-actin (1:1000) (Agrisera antibodies, Vannasa, Sweden) over night at 4 °C with gentle shaking. Goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used to visualize the stained bands with an enhanced chemiluminescence visualization kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Detection of Cell Death (Plasma Membrane Integrity)

Cell death was estimated by measuring ion leakage from root followed the method of Coskun et al., with minor modifications.40 Specifically, four root segments (around 4 cm long) were cut and rinsed three times with deionized water to remove leakage ion related to the immediate injury inflicted on the tissue during cutting. The root segments were incubated in 15 mL vials containing 10 mL deionized water for 3 h in a rotary shaker at room temperature. Following 3 h incubation, the conductivity of the solution was measured (Meter conductivity 3 star W/PRB) and boiled at 100 °C for 20 min. When the solution was cooled to room temperature, the conductivity was measured again and the results were expressed as relative conductivity [(conductivity after incubation/conductivity before boiling) *100].

Gas Exchange Measurement

Leaf net photosynthetic rate (Pn), transpiration (E), and stomatal conductance (gs) were measured by placing the leaf in the cuvette of a portable gas exchange system (CIRAS-2; PP Systems, Amesbury, MA). The environmental conditions in the cuvette were controlled at leaf temperature = 25 °C, PPF = 600 μmol·m−2·s−1, and CO2 concentration = 380 μmol·mol−1. The data was recorded when the environmental conditions and gas exchange parameters in the cuvette were stable.

Statistical Analysis

The plants for Ce concentration, H2O2 concentration, lipid peroxidation, antioxidant enzymes and ion leakage rate analysis were grown separately. At harvest, the tissues from nine plants were collected, mixed, and the mixture was separated into three groups. The data was reported as averages of three replicates. A one-way ANOVA test was performed, and Tukey-HSD multiple comparisons conducted test performed using the statistical package SPSS Version 12.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Statistical significance was based on probabilities of p ≤0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation and the Environmental Protection Agency under Cooperative Agreement Number DBI-0830117. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation or the Environmental Protection Agency. This work has not been subjected to EPA review and no official endorsement should be inferred. The authors also acknowledge the USDA grant number 2008-38422-19138, the Toxicology Unit of the BBRC (NIH NCRR Grant # 2G12RR008124-16A1), and the NSF Grant # CHE-0840525. Also, the authors thank the staff of the Cell Culture and High Throughput Screening (HTS) Core Facility of UTEP for services and facilities provided. This core facility is supported by grant 5G12RR008124 to the Border Biomedical Research Center (BBRC), granted to the University of Texas at El Paso from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) of the NIH. J. L. Gardea-Torresdey acknowledges the Dudley family for the Endowed Research Professorship in Chemistry.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: The CAT and APX activities determination, the QB buffer preparation, TEM sample preparation, the uptake of Ce in corn plant tissues, Western Blot result of corn leaves, TEM images, gas exchange results are available as Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perez-de-Luque A, Rubiales D. Nanotechnology for Parasitic Plant Control. Pest Manag. Sci. 2009;65:540–545. doi: 10.1002/ps.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang L, Watts DJ. Particle Surface Characteristics May Play an Important Role in Phytotoxicity of Alumina Nanoparticles. Toxicol. Lett. 2005;158:122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin DH, Xing BS. Phytotoxicity of NPs: Inhibition of Seed Germination and Root Growth. Environ. Pollut. 2007;150:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stampoulis D, Sinha SK, White JC. Assay-Dependent Phytotoxicity of Nanoparticles to Plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43:9473–9479. doi: 10.1021/es901695c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma Y, Kuang L, He X, Bai W, Ding Y, Zhang Z, Zhao Y, Chai Z. Effect of Rare Earth Oxide Nanoparticles on Root Elongation of Plants. Chemosphere. 2010;78:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez-Moreno ML, de La Rosa G, Hernandez-Viezcas JA, Castillo-Michel H, Botez CE, Peralta-Videa JR, Gardea-Torresdey JL. Evidence of the Differential Biotransformation and Genotoxicity of ZnO and CeO2 Nanoparticles on Soybean (Glycine max) Plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44:7315–7320. doi: 10.1021/es903891g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietz K, Herth S. Plant Nanotoxicology. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:582–589. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khodakovskaya M, Dervishi E, Mahmood M, Xu Y, Li Z, Watanabe F, Biris AS. Carbon Nanotubes Are Able to Penetrate Plant Seed Coat and Dramatically Affect Seed Germination and Plant Growth. ACS Nano. 2009;3:3221–3227. doi: 10.1021/nn900887m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khodakovskaya MV, Silva K, Nedosekin DA, Dervishi E, Biris AS, Shashkov EV, Galanzha EI, Zharov VP. Complex Genetic, Photothermal, and Photoacoustic Analysis of Nanoparticle-Plant Interactions. PNAS. 2011;108:1028–1033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008856108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atha DH, Wang H, Petersen EJ, Cleveland D, Holbrook RD, Jaruga P, Dizdaroglu M, Xing B, Nelson BC. Copper Oxide Nanoparticle Mediated DNA Damage in Terrestrial Plant Models. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:1819–1827. doi: 10.1021/es202660k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nanotechnology Consumer Product Inventory. Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and the Pew Charitable Trusts; Washington, DC: 2011. Available at http://www.nanotechproject.org/consumerproducts. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development . List of Manufactured Nanomaterials and List of Endpoints for Phase One of the OECD Testing Programme. Paris, France: 2008. (Series on the Safety of Manufactured Nanomaterials No. 6). http://www.olis.oecd.org/olis/2008doc.nsf/LinkTo/NT000034C6/$FILE/JT03248749.PDF. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kosynkin VD, Arzgatkina AA, Ivanov EN, Chtoutsa MG, Grabko AI, Kardapolov AV, Sysina NA. The Study of Process Production of Polishing Powder Based on Cerium Dioxide. J. Alloys Compd. 2000;303-304:421–425. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corma A, Atienzar P, Garcia H, Chane-Ching JY. Hierarchically Mesostruc-tured Doped CeO2 with Potential form Solar-cell Use. Nat. Mater. 2004;3:394–397. doi: 10.1038/nmat1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thill A, Zeyons O, Spalla O, Chauvat F, Rose J, Auffan M, Flank AM. Cytotoxicity of CeO2 Nanoparticles for Escherichia Coli. Physico-Chemical Insight of the Cytotoxicity Mechanism. Sci. Total Environ. 2006;40:6151–6156. doi: 10.1021/es060999b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston BD, Scown TM, Moger J, Cumberland SA, Baalousha M, Linge K, van Aerle R, Jarvis K, Lead JR, Tyler CR. Bioavailability of Nanoscale Metal Oxides TiO2, CeO2, and ZnO to Fish. Sci. Total Environ. 2010;44:1144–1151. doi: 10.1021/es901971a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Statistics Division “Maize, rice and wheat: area harvested, production quantity, yield”. 2009.

- 18.Asli S, Neumann PM. Colloidal Suspensions of Clay or Titanium Dioxide NPs Can Inhibit Leaf Growth and Transpiration via Physical Effects on Root Water Transport. Plant Cell Environ. 2009;32:577–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao L, Peralta-Videa JR, Varela-Ramirez A, Castillo-Michel H, Li C, Zhang J, Aguilera RJ, Keller AA, Gardea-Torresdey JL. Effect of Surface Coating and Organic Matter on the Uptake of CeO2 NPs by Corn Plants Grown in Soil: Insight into the Uptake Mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012;225:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan XM, Lin C, Fugetsu B. Studies on Toxicity of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on Suspension Rice Cells. Carbon. 2009;47:3479–3487. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen C, Zhang Q, Li J, Bi F, Yao N. Induction of Programmed Cell Death in Arabidopsis and Rice by Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes. Am. J. Bot. 2010;97:1602–1609. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez-Serrano M, Romero-Puertas MC, Pazmino DM, Testillano PS, Risueno MC, Rio LAD, Sandalio LM. Cellular Response of Pea Plants to Cadmium Toxicity: Cross Talk between Reactive Oxygen Species, Nitric Oxide, and Calcium. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:229–243. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.131524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez AA, Grunberg KA, Taleisnik EL. Reactive Oxygen Species in the Elongation Zone of Maize Leaves Are Necessary for Leaf Extension. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:1627–1632. doi: 10.1104/pp.001222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma P, Jha AB, Dubey RS, Pessarakli M. Reactive Oxygen Species, Oxidative Damage, and Antioxidative Defense Mechanism in Plants under Stressful Conditions. J. Bot. 2012 doi:10.1155/2012/217037. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall JL. Cellular Mechanisms for Heavy Metal Detoxification and Tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2002;53:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang W, Vinocur B, Shoseyov O, Altman A. Role of Plant Heat-shock Proteins and Molecular Chaperones in the Abiotic Stress Response. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agarwal M, Sahi C, Katiyar-Agarwal S, Agarwal S, Young T, Gallie DR, Sharma VM, Ganesan K, Grover A. Molecular Characterization of Rice HSP101: Complementation of Yeast HSP104 Mutation by Disaggregation of Protein Granules and Differential Expression in Indica and Japonica Rice Types. Plant Mol. Biol. 2003;51:543–553. doi: 10.1023/a:1022324920316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin C-Y, Chen YM, Key JL. Solute Leakage in Soybean Seedlings under Various Heat Shock Regimes. Plant Cell Physiol. 1985;26:1493–1498. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neumann D, Lichtenberger O, Gunther D, Tschiersch K, Nover L. Heat-shock Proteins Induce Heavy-Metal Tolerance in Higher Plants. Planta. 1994;194:360–367. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen R, Ratnikova TA, Stone MB, Lin S, Lard M, Huang G, Hudson JS, Ke P. Differential Uptake of Carbon Nanoparticles by Plant and Mammalian Cells. Small. 2010;6:612–617. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsiao TC, Acevedo E. Plant Response to Water Deficits, Water Use Efficiency, and Drought Resistance. Agr. For. Meteorol. 1974;14:59–84. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niu G, Rodriguez DS. Growth and Physiological Response to Drought Stress in Four Oleander Clones. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 2008;133:188–196. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gay C, Gebicki JM. A Critical Evaluation of the Effect of Sorbitol on the Ferric-Xylenol Orange Hydroperoxide Assay. Anal. Biochem. 2000;284:217–220. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodríguez-Serrano M, Romero-Puertas MC, Zabalza A, Corpas FJ, Gómez M, del Río LA, Sandalio LM. Cadmium Effect on Oxidative Metabolism of Pea (Pisum sativum L.) Roots. Imaging of Reactive Oxygen Species and Nitric Oxide Accumulation in vivo. Plant Cell Environ. 2006;29:1532–1544. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2006.01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garza KM, Soto KF, Murr LE. Cytotoxicity and Reactive Oxygen Species Generation from Aggregated Carbon and Carbonaceous Nanoparticulate Materials. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2008;3:83–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallego SM, Benavides MP, Tomaro ML. Effect of Heavy Metal Ion Excess on Sunflower Leaves Evidence for Involvement of Oxidative Stress. Plant Sci. 1996;121:151–159. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murgia I, Tarantino D, Vannini C, Bracale M, Carravieri S, Soave C. Arabidopsis thaliana Plants Overexpressing Thylakoidal Ascorbate Peroxidase Show Increased Resistance to Paraquat-Induced Photooxidative Stress and to Nitric oxide-Induced Cell Death. Plant J. 2004;38:940–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heath RL, Packer L. Photoperoxidation in Isolated Chloroplasts I. Kinetics and Stoichiometry of Fatty Acid Peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1968;125:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90654-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nieto-Soteo J, Martinez LM, Ponce G, Cassab GI, Alagon A, Meeley RB, Ribaut J, Yang R. Maize HSP101 Plays Important Roles in both Induced and Basal Thermotolerance and Primary Root Growth. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1621–1633. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coskun D, Britto DT, Jean Y, Schulze LM, Becker A, Kronzucker HJ. Silver Ions Disrupt K+ Homeostasis and Cellular Integrity in Intact Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Roots. J. Exp. Bot. 2011;63:151–162. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.