Abstract

Single-nucleotide polymorphism in IFNL3 gene (rs12979860) predicts spontaneous and therapy-induced HCV clearance. In a previous study from our group PBMC from patients with favourable rs12979860 genotype showed higher levels of IFNAR-1 mRNA. Recently, a dinucleotide polymorphism, ss469415590 (TT or ΔG), has been discovered in the region upstream IFNL3 gene, which is in high linkage disequilibrium with rs12979860. ss469415590[ΔG] is a frameshift variant that creates a novel gene, designed IFNL4, encoding the interferon-lambda 4 protein (IFNL4). The aim of the present study was to extend the analysis of IFNAR-1 mRNA levels to the ss469415590 variants. Our results highlight that the difference of IFNAR-1 mRNA levels between favourable and unfavourable genotype combinations, at both rs12979860 and ss469415590 loci, is stronger than that observed for single polymorphisms at each locus. These findings suggest may represent the biological basis for the observed association between IFNL3 CC and IFNL4 TT/TT genotypes and favourable outcome of either natural HCV infection (clearance vs chronic evolution) or IFN-based therapy.

Introduction

The global prevalence of Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is estimated to be 2%, accounting for up to 180 million people infected worldwide [1]. The ability of HCV to inhibit the activation of endogenous type I interferon (IFN) system could underlie its success in establishing a chronic infection [2]. Type I IFN comprises a family of about 20 members that bind a common receptor complex, the type I IFN receptor (IFNAR) [3]. IFNs exhibit direct antiviral activity by inducing an antiviral state through expression of various intracellular genes (IFN-stimulated genes, ISGs), including IP10, whose levels are known to be prognostic factors of viral response to standard of care therapy (SOC) [4–6]. A group of recently discovered cytokines (IFN-lambda1/interleukin-29 [IL-29], IFN-lambda2/IL-28A, and IFN-lambda3/IL-28B, also designated IFNL1 to 3, respectively), assigned to a new type of IFN (type III IFN), gained increased attention in the HCV field [7]. The biological activity of type III IFN overlaps to some extent with that of type I IFN, and similar subsets of ISGs are induced as well [8]. However, there are important kinetic differences in the induction of ISGs by type I and type III IFN, and these differences may indeed produce distinct functional activities [9].

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) identified several single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in IFNL3 genomic region that are strongly related to spontaneous and therapy-induced HCV clearance rate [10–13]. Numerous investigators confirmed the importance of IFNL3 SNPs in the therapeutic response of HCV patients to SOC [14,15]. Among the identified SNPs, rs12979860 appeared the most relevant, being the rs12979860-favorable CC genotype associated with a more than two-fold increased rate of sustained virologic response (SVR) with respect to hapless (CT or TT) genotypes [16]. More recently, a new transiently induced gene near the IFNL3 gene has been discovered, harbouring a dinucleotide variant ss469415590 (TT or ΔG), which is in high linkage disequilibrium with rs12979860. The ss469415590 [ΔG] allele is a frameshift variant that creates a novel gene, IFNL4, encoding a fully functional protein designated interferon-lambda 4 (IFNL4) [17,18]. The ss469415590 [TT] allele, which abrogates the production of the IFNL4 protein, is considered the favourable haplotype towards response to SOC, while the ss469415590 [ΔG] is considered the unfavourable one [18,19].

The biological basis for the influence of IFNL3 polymorphisms on HCV infection is not clear so far, and is probably complex, involving several host functions, exerted both at tissue (liver) and systemic (i.e. blood) level [20]. To this respect, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) are important players in the struggle against HCV [21–23], and, although not considered as main target of HCV replication, their functions are impaired by indirect mechanisms involving HCV-induced cytokines or viral products [24–27]. It has been shown that enhanced expression of ISGs, not only in the liver, but also in PBMC, is a negative prognostic factor of virological response to IFN therapy [5, 28–30].

Previous findings from our group showed that IFNAR-1 mRNA levels are strongly reduced in HCV-infected subjects, and the reduction is much stronger in individuals with rs12979860 CT/TT alleles as compared to CC [31]. We hypothesized that endogenously produced IFN-lambda may be responsible for the partial reversal of the impairment IFNAR-1 expression in CC individuals, possibly conferring to these individuals a response advantage to either endogenous or exogenous IFN-alpha [31].

In the present study the analysis of IFNAR-1 mRNA levels was extended to the ss469415590 variants, either alone or in conjunction with the rs12979860 polymorphisms.

Materials and Methods

The project was approved by the Local Ethical Committee, and patients agreed to participate to the study by signing informed consent.

PBMC samples from 32 treatment-naїve patients, chronically infected with HCV (genotype 1 or 4), collected at the National Institute for Infectious Diseases and stored in the Institutional Biorepository, for whom the rs12979860 (here designated IFNL3) and ss469415590 (here designated IFNL4) genotypes were known, were retrospectively selected to perform a comparative analysis.

IFNL3 rs12979860 genotype was established on genomic DNA, using a custom made TaqMan assay previously described [31]. IFNL4 ss469415590 genotype was established using a method established by Prokunina-Olsson and collaborators [18]. Allelic discrimination was achieved using the SDS 1.3 software [18].

Total cellular RNA was extracted from PBMC using Trizol (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) and reverse-transcribed by TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagent kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The quantification of IFNAR-1 and IP10 mRNA was performed by Taqman real-time RT-PCR methods previously established in our laboratory [5,32]. Results were expressed as ratio to beta-actin.

In a set of experiments the PBMC were exposed for 3h to either medium or 103 IU/ml recombinant human IFN-alpha2b (Intron; Schering Corp., Kenilworth, NJ, USA; specific activity: 400MIU/mg,1IU corresponding to 2.5pg). The timing and dose of IFN–alpha experiment was selected on the basis of a preliminary experiment performed on healthy donor PBMC. In fact, the 3h time point corresponds to peak of IP10 mRNA, and at this time point the enhancement is at plateau from 102 IU/ml onward. However, we selected 103 IU/ml to avoid the individual variability due to the possible suboptimal induction at lower doses.

Statistical analyses were performed by Prism 4 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Differences were evaluated by the non parametric Mann-Whitney U test or by Student’s t test, as appropriate. Correlations were analyzed by Pearson r test. Differences with p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

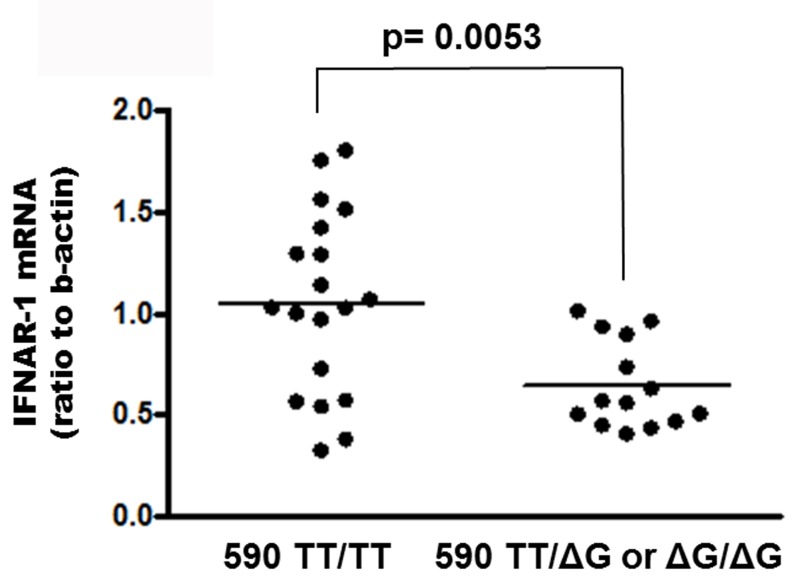

The distribution of IFNL3 genotypes was: 8 CC (25%), 13 CT (40.5%), 11 TT (34.5%); the distribution of IFNL4 genotypes was: 18 TT/TT (56.2%), 10 TT/ΔG (31.3%), 4 ΔG/ΔG (12.5%) (Table 1). As shown in Fig. 1, median levels of IFNAR-1 mRNA in PBMC from patients carrying IFNL4 TT/TT were 1,82 fold higher than those from patients carrying the ΔG allele (either TT/ΔG or ΔG/ΔG) [median: 1.026 (IQR: 0.5710–1.420) vs 0.5640 (0.4585–0.9135) p = 0.0053]. No correlation between IFNAR-1 expression and HCV viral load was observed (r = -0.1152; p = 0.6598).

Table 1. Characteristics of 32 treatment naive HCV-infected patients included in the study.

| Age [median (range)] years | 53.5 (30–81) |

| Sex (Male, Female) | 25, 7 |

| AST [median (range)] IU/L | 41.5 (17–162) |

| ALT [median (range)] IU/L | 63 (13–310) |

| γ-GT [median (range)] IU/L | 38 (9–599) |

| HCV load [median (range)] Log10 IU/ml | 6.12 (4.22–6.84) |

| HCV genotypes (gt1, gt4) | 22, 10 |

| IFNL3 rs 12979860 genotypes (CC, CT, TT) | 8, 13, 11 |

| IFNL4 ss469415590 genotypes (TT/TT, TT/ΔG, ΔG/ΔG) | 18,10, 4 |

Fig 1. Levels of IFNAR-1 mRNA in PBMC from HCV-infected naїve subjects carrying IFNL4 ss469415590 TT/TT genotype vs patients carrying the ΔG allele.

Results are expressed as ratio to beta-actin. The horizontal bar indicates median.

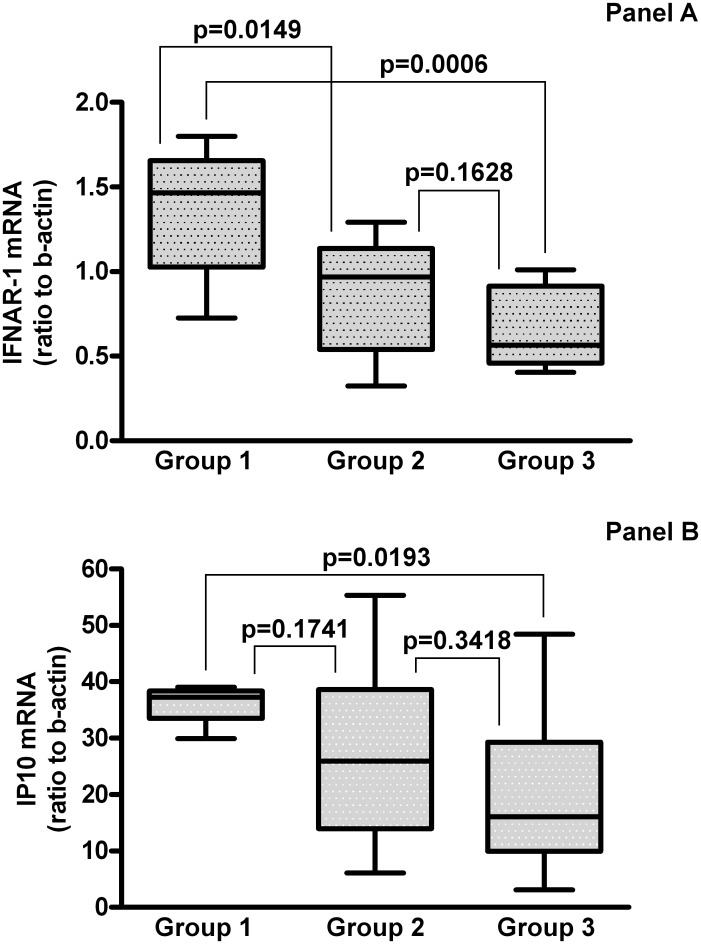

When considering the patients grouped according to the IFNL3 and IFNL4 genotype combinations, 8 patients were IFNL3 CC and IFNL4 TT/TT (IFNL3 and IFNL4 favourable), Group 1; 11 patients were IFNL3 CT or TT and IFNL4 TT/TT (IFNL3 unfavourable and IFNL4 favourable), Group 2; 14 patients were IFNL3 CT or TT and IFNL4 TT/ΔG or ΔG/ΔG (IFNL3 and IFNL4 unfavourable), Group 3.

The median levels of IFNAR-1 mRNA in PBMC from patients with the various IFNL3 and IFNL4 genotype combinations are shown in Fig. 2 Panel A. As can be seen (Fig. 2 Panel A) PBMC from patients with favourable combination at both IFNL3 and IFNL4 loci contain higher levels of IFNAR-1 mRNA as compared to the other groups. In particular, the most prominent difference (2.6 fold) was observed for Group 1 vs Group 3 [median: 1.466 (IQR: 1.025–1.655) vs 0.564 (IQR: 0.458–0.913); p = 0.0006]; an 1.51 fold difference was observed vs Group 2 [median:0.969 (IQR: 0.540–1.137); p = 0.0149]; the difference between Group 2 and Group 3 was not statistically significant [p = 0.1628].

Fig 2. Levels of IFNAR-1 mRNA in PBMC from the HCV-infected naïve subjects grouped according to their IFNL3 and IFNL4 genotype combinations.

Panel A. Group 1: IFNL3 CC and IFNL4 TT/TT (IFNL3 favourable, IFNL4 favourable), n = 8; Group 2: IFNL3 CT or TT and IFNL4 TT/TT (IFNL3 unfavourable and IFNL4 favourable) n = 10; Group 3: IFNL3 CT or TT and IFNL4 TT/ΔG or ΔG/ΔG (IFNL3 and IFNL4 unfavourable) n = 14. The results are expressed as ratio to beta-actin (median, IQR). Levels of IP10 mRNA in PBMC from the various groups after 3h of exposure to 103 IU/ml IFN-alpha2b in vitro, according to their IFNL3 and IFNL4 genotype combinations. Panel B. Group 1: IFNL3 CC and IFNL4 TT/TT (IFNL3 favourable, IFNL4 favourable) n = 6; Group 2: IFNL3 CT or TT and IFNL4 TT/TT (IFNL3 unfavourable and IFNL4 favourable) n = 11; Group 3: IFNL3 CT or TT and IFNL4 TT/ΔG or ΔG/ΔG (IFNL3 and IFNL4 unfavourable) n = 11. The results are expressed as ratio to beta-actin, after subtraction of values from unexposed cultures (median, IQR). The range of IP10 mRNA levels in unexposed PBMC cultures was 0,375 to 0,967.

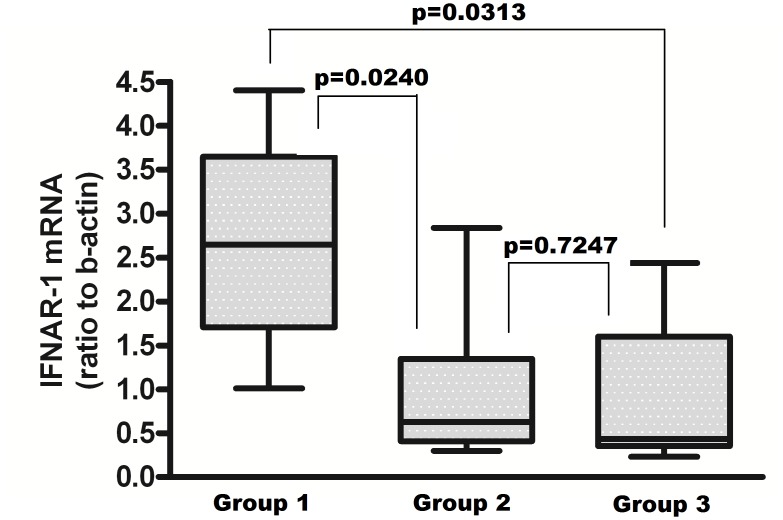

To explore whether the differences in the levels of IFNAR-1 mRNA could lead to an increased response to exogenously administered IFN-alpha, PBMC from patients with the various genotype combinations were exposed to IFN-alpha and the induction of mRNA for IP10, as biomarker of IFN activity, was measured. The results, shown in Fig. 2 Panel B, indicate a gradient of IFN response among the groups in term of IP10 mRNA induction, that paralleled the levels of IFNAR-1 expressed before IFN-alpha treatment (Fig. 2 Panel A). In particular, the difference between Group 1 and Group 3 was highly significant [median: 37.28 (IQR: 33.53–38.37) vs 16.06 (IQR: 9.979–29.27); p = 0.0193]. IFNAR-1 mRNA levels were not significantly modified by IFN-alpha treatment (Fig. 3), reflecting the differences among groups observed at baseline.

Fig 3. Levels of IFNAR-1 mRNA in PBMC from the HCV-infected naïve subjects after 3h of exposure to 103 IU/ml IFN-alpha2b in vitro, according to their IFNL3 and IFNL4 genotype combinations.

Group 1: IFNL3 CC and IFNL4 TT/TT (IFNL3 favourable, IFNL4 favourable) n = 6; Group 2: IFNL3 CT or TT and IFNL4 TT/TT (IFNL3 unfavourable and IFNL4 favourable) n = 11; Group 3: IFNL3 CT or TT and IFNL4 TT/ΔG or ΔG/ΔG (IFNL3 and IFNL4 unfavourable) n = 11. The results are expressed as ratio to beta-actin, after subtraction of values from unexposed cultures (median, IQR).

Discussion

Several studies confirmed the importance of IFNL3 SNPs in the kinetics of HCV RNA decay and, ultimately, in the response to PEG-IFN plus RBV treatment [14,15]. In addition, IFNL3 genotype has been correlated with the expression of IFN-lambda receptor-1 and with non-responsiveness to IFN-alpha therapy [33].

Recently, a polymorphism within the gene encoding IFNL4 protein (ss469415590 TT or ΔG), in strong linkage disequilibrium with rs12979860 polymorphism, has been described, being more strongly associated with HCV clearance and treatment outcome than the previous one [18,19].

More recently, IFNL4 genotype has also been shown to be correlated with the probability of virus eradication in patients receiving IFN-free therapy [34]. Based on these evidences and considering a previous study in which our group observed higher levels of IFNAR-1 mRNA in PBMC from patients with favourable IFNL3 genotype [31], we extended the analysis to IFNL4 polymorphisms, considering also the combination of alleles at both IFNL3 and IFNL4 loci.

Our results highlighted a significantly higher expression (1.82 fold) of IFNAR-1 mRNA in PBMC from patients carrying IFNL4 TT/TT genotype vs patients carrying the ΔG allele. More interestingly, the most prominent difference of IFNAR-1 mRNA levels was observed between patients with the most favourable combination at both IFNL3 and IFNL4 loci with respect to patients with combinations involving any unfavourable allele. Overall, the difference between the favourable and unfavourable combinations at both loci was much stronger than that observed for the single polymorphisms at each locus, i.e. 2.6 fold for the combination vs 1.82 fold for IFNL4 (present study) and 2.3 fold for IFNL3 [31].

The higher expression of IFNAR-1 in the favourable combination is biologically relevant, since it is connected with a stronger response to IFN-alpha exposure in vitro, in terms of IP10 mRNA induction.

One limitation of this study is that we could not evaluate any correlation between IFNL3 and IFNL4 genotypes, baseline levels of IFNAR-1 and therapeutic response, since only few patients included in this study underwent IFN-based treatment so far (12 overall, 4 SVR and 8 non SVR).

The findings from the present study, if confirmed in larger studies and supported by treatment outcome data, may offer a key for elucidating the biological basis of the advantage represented by IFNL3 and IFNL4 favourable genotypes towards natural or therapy-induced HCV clearance.

Acknowledgments

The contribution of Laboratory of Microbiology and Infectious Disease Biorepository from National Institute for Infectious Diseases “L. Spallanzani,” Rome, Italy, is warmly acknowledged.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This work was partly supported by grants from Italian Ministry of Health, Ricerca Corrente and Ricerca Finalizzata. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. El-Serag HB (2012) Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 142: 1264–1273. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Strader DB, Wright T, Thomas DL, Seeff LB, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (2004) Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C. Hepatology 39: 1147–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pestka S, Krause CD, Walter MR (2004) Interferons, interferon-like cytokines, and their receptors. Immunol Rev 202:8–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lagging M, Romero AI, Westin J, Norkrans G, Dhillon AP, et al. (2006) IP-10 predicts viral response and therapeutic outcome in difficult-to-treat patients with HCV genotype 1 infection. Hepatology 44: 1617–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lalle E, Calcaterra S, Horejsh D, Abbate I, D’Offizi G, et al. (2008) Ability of peripheral blood mononuclear cells to activate interferon response in vitro is predictive of virological response in HCV patients. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 22: 153–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Petry H, Cashion L, Szymanski P, Ast O, Orme A, et al. (2006) Mx1 and IP-10: biomarkers to measure IFN-beta activity in mice following gene-based delivery. J Interferon Cytokine Res 26: 699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Donnelly RP, Kotenko SV (2010) Interferon-lambda: a new addition to an old family. J Interferon Cytokine Res 30: 555–564. 10.1089/jir.2010.0078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sheppard P, Kindsvogel W, Xu W, Henderson K, Schlutsmeyer S, et al. (2003) IL-28, IL-29 and their class II cytokine receptor IL-28R. Nat Immunol 4: 63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bolen CR, Ding S, Robek MD, Kleinstein SH (2014) Dynamic expression profiling of type I and type III interferon-stimulated hepatocytes reveals a stable hierarchy of gene expression. Hepatology 59: 1262–72. 10.1002/hep.26657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, et al. (2009) Genetic variation in IL-28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature 461: 399–401. 10.1038/nature08309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, Berg T, Weltman M, et al. (2009) IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet 41: 1100–4. 10.1038/ng.447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, Kurosaki M, Matsuura K, et al. (2009) Genome-wide association of IL-28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet 41: 1105–1109. 10.1038/ng.449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thomas DL, Thio CL, Martin MP, Qi Y, Ge D, et al. (2009) Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature 461: 798–801. 10.1038/nature08463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mangia A, Thompson AJ, Santoro R, Piazzolla V, Tillmann HL, et al. (2010) An IL-28B polymorphism determines treatment response of hepatitis C virus genotype 2 or 3 patients who do not achieve a rapid virologic response. Gastroenterology 139: 821–827. 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McCarthy JJ, Li JH, Thompson A, Suchindran S, Lao XQ, et al. (2010) Replicated association between an IL-28B gene variant and a sustained response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Gastroenterology 138: 2307–2314. 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lange CM, Zeuzem S (2011) IL-28B single nucleotide polymorphisms in the treatment of hepatitis C. J Hepatol 55: 692–701. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hamming OJ, Terczyńska-Dyla E, Vieyres G, Dijkman R, Jųrgensen SE, et al. (2013) Interferon lambda 4 signals via the IFNλ receptor to regulate antiviral activity against HCV and coronaviruses. EMBO J 32: 3055–65. 10.1038/emboj.2013.232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prokunina-Olsson L, Muchmore B, Tang W, Pfeiffer RM, Park H, et al. (2013) A variant upstream of IFNL3 (IL28B) creating a new interferon gene IFNL4 is associated with impaired clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nat Genet. 45: 164–171. 10.1038/ng.2521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O’Brien TR, Prokunina-Olsson L, Donnelly RP (2014) IFN-λ4: The Paradoxical New Member of the Interferon Lambda Family. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 34: 829–38. 10.1089/jir.2013.0136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chinnaswamy S (2014) Genetic Variants at the IFNL3 Locus and Their Association with Hepatitis C Virus Infections Reveal Novel Insights into Host-Virus Interactions. J Interferon Cytokine Res 34: 479–97. 10.1089/jir.2013.0113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen AY, Zeremski M, Chauhan R, Jacobson IM, Talal AH, et al. (2013) Persistence of hepatitis C virus during and after otherwise clinically successful treatment of chronic hepatitis C with standard pegylated interferon α-2b and ribavirin therapy. PLoS One 8: e80078 10.1371/journal.pone.0080078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Inglot M, Pawlowski T, Szymczak A, Malyszczak K, Zalewska M, et al. (2013) Replication of hepatitis C virus in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with pegylated interferon alpha and ribavirin. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online) 67: 186–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pawełczyk A, Kubisa N, Jabłońska J, Bukowska-Ośko I, Caraballo Cortes K, et al. (2013) Detection of hepatitis C virus (HCV) negative strand RNA and NS3 protein in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC): CD3+, CD14+ and CD19+. Virol J 10: 346 10.1186/1743-422X-10-346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chattergoon MA, Latanich R, Quinn J, Winter ME, Buckheit RW 3rd, et al. (2014) HIV and HCV activate the inflammasome in monocytes and macrophages via endosomal Toll-like receptors without induction of type 1 interferon. PLoS Pathog 10: e1004082 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cimini E, Bonnafous C, Bordoni V, Lalle E, Sicard H, et al. (2012) Interferon-α improves phosphoantigen-induced Vγ9Vδ2 T-cells interferon-γ production during chronic HCV infection. PLoS One 7: e37014 10.1371/journal.pone.0037014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holder KA, Russell RS, Grant MD (2014) Natural Killer Cell Function and Dysfunction in Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Biomed Res Int. 2014: 903764 10.1155/2014/903764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Piazzolla G, Tortorella C, Schiraldi O, Antonaci S (2000) Relationship between interferon-gamma, interleukin-10, and interleukin-12 production in chronic hepatitis C and in vitro effects of interferon-alpha. J Clin Immunol 20: 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abbate I, Romano M, Longo R, Cappiello G, Lo Iacono O, et al. (2003) Endogenous levels of mRNA for IFNs and IFN-related genes in hepatic biopsies of chronic HCV-infected and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis patients. J Med Virol 70: 581–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lempicki RA, Polis MA, Yang J, McLaughlin M, Koratich C, et al. (2006) Gene expression profiles in hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HIV coinfection: class prediction analyses before treatment predict the outcome of anti-HCV therapy among HIV-coinfected persons. J Infect Dis 193: 1172–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pawlotsky JM, Hovanessian AG, Roudot-Thoraval F, Robert N, Bouvier M, et al. (1996) Effect of alpha interferon (IFN-alpha) on 2′-5′ oligoadenylate synthetase activity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with chronic hepatitis C: relationship to the antiviral effect of IFN-alpha. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 40: 320–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lalle E, Bordi L, Caglioti C, Garbuglia AR, Castilletti C, et al. (2014) IFN-alpha Receptor-1 Upregulation in PBMC from HCV Naïve Patients carrying CC genotype. Possible role of IFN-lambda. PlosOne 9: e93434 10.1371/journal.pone.0093434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Capobianchi MR, Lalle E, Martini F, Poccia F, D’Offizi G, et al. (2006) Influence of GBV-C infection on the endogenous activation of the IFN system in HIV-coinfected patients. Cell Mol Biol 52: 3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Duong FH, Trincucci G, Boldanova T, Calabrese D, Campana B, et al. (2014) IFN-λ receptor 1 expression is induced in chronic hepatitis C and correlates with the IFN-λ3 genotype and with non-responsiveness to IFN-α therapies. J Exp Med 211: 857–68. 10.1084/jem.20131557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Meissner EG, Bon D, Prokunina-Olsson L, Tang W, Masur H, et al. (2014) IFNL4-ΔG Genotype Is Associated With Slower Viral Clearance in Hepatitis C, Genotype-1 Patients Treated With Sofosbuvir and Ribavirin. J Infect Dis 209: 1700–4. 10.1093/infdis/jit827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.