Abstract

As part of a larger study using 454 pyrosequencing to investigate the vaginal microbiota of women with bacterial vaginosis (BV), we found an association between a novel BV-associated bacterium (BVAB1) and high Nugent scores and propose that BVAB1 is the curved Gram-negative rod traditionally identified as Mobiluncus spp. in vaginal Gram stains.

Keywords: Bacterial vaginosis, Mobiluncus, BVAB1, Nugent score

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is the most common vaginal infection (Hillier et al., 2008; Sobel, 2005). It is associated with preterm birth, pelvic inflammatory disease, and increased risk of acquisition and transmission of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV (Brotman et al., 2010; Cherpes et al., 2003; Leitich et al., 2003; Martin et al., 1999; Sweet, 2000). BV is characterized by depletion of H2O2-producing lactobacilli and increases in facultative (Gardnerella vaginalis) and strict anaerobic (Prevotella spp., Mycoplasma hominis, Bacteroides spp., Peptostreptococcus spp., Mobiluncus spp., Atopobium vaginae, etc.) bacteria (Hillier et al., 2008). In research settings, BV is defined by Gram stain of vaginal secretions using the Nugent scoring system (Nugent et al., 1991). To determine the Nugent score, Gram stains are evaluated at 1000× magnification for large Gram-positive rods (lactobacillus morphotypes), small Gram-variable rods (G. vaginalis morphotypes), small Gram-negative rods (Bacteroides spp. morphotypes), and curved Gram-negative or Gram-variable rods (Mobiluncus spp. morphotypes). A score of 0–3 is graded as lactobacillus-predominate normal vaginal flora; 4–6 as intermediate flora (emergence of G. vaginalis); and 7–10 as abnormal vaginal flora consistent with BV (disappearance of Lactobacillus spp. with numerous G. vaginalis and strict anaerobes). The sensitivity and specificity of the Nugent score compared with the Amsel criteria (Amsel et al., 1983) (used for the clinical diagnosis of BV) are 89% and 83%, respectively (Schwebke et al., 1996).

While cultivation-dependent techniques have identified G. vaginalis and other BV-associated bacteria (Eschenbach et al., 1989; Hillier et al., 2008; Marrazzo et al., 2002; Spiegel et al., 1983), recent advances in high-throughput sequencing have facilitated the detection and identification of previously uncultivated BV-associated bacteria (Marrazzo et al., 2010; Srinivasan and Fredricks, 2008). These advances could potentially impact the definition of the Nugent score. As part of a larger study using pyrosequencing to investigate the vaginal microbiota of sexual risk behavior groups of women with BV (Muzny et al., 2013), we found an association between a novel BV-associated bacterium (BVAB1) (Fredricks et al., 2005) and high Nugent scores. This association suggests that BVAB1 may be the curved Gram-negative rod traditionally assumed to be Mobiluncus spp. in vaginal Gram stains, as noted in previous studies (Srinivasan et al., 2013; Zozaya-Hinchliffe et al., 2010).

This study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, the Mississippi State Department of Health (MSDH), and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Vaginal swabs were collected at a single visit from eligible women with BV (based on 3 or 4 Amsel criteria and a Nugent score of 7–10; Nugent scores were read by an experienced technician in the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center STD Pathogens Laboratory who was blinded to the molecular analysis results of this study) aged 18 years or older presenting to the MSDH STD Clinic and enrolled in a Women's Reproductive Health Program between February 2009 and October 2010 (Muzny et al., 2011) (n = 68) or a Mycoplasma genitalium cohort study between October 2006 and January 2009 (data unpublished) (n = 44). Total genomic DNA was purified, and 454 pyrosequencing was performed, as previously reported (Muzny et al., 2013). Briefly, total genomic DNA was isolated and purified using the QIAamp kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The V1–V3 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the primers 28F: 5′-GAGTTTGATCNTGGCTCAG-3′ and 519R: 5′-GTNTTACNGCGGCKGCTG-3′, and amplicons were reamplified with bar-coded primers for sequencing by 454 pyrosequencing (Research Laboratories, Lubbock, TX, USA). Raw sequences were analyzed and organized using QIIME, as previously reported (Muzny et al., 2013). The number of reads per sample ranged from 2499 to 25, 274 with an average of 8467 reads per sample. The average read length was 492 bases across all samples.

Sequences were grouped into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using the clustering program UCLUST (Edgar, 2010) at a similarity threshold of 0.97. The Ribosomal Database Program (RDP) classifier (Wang et al., 2007) was used to assign taxonomic category to all OTUs at a confidence threshold of 80% (0.8). The RDP classifier uses the 16S rRNA RDP database, which has taxonomic categories predicted to the genus level (Cole et al., 2009). Since the RDP classifier provides taxonomic identification of OTUs only to the genus level, selected highly abundant OTUs (including OTU-624, the most highly abundant OTU across all samples in this study at 26% (Muzny et al., 2013) and subsequently identified as BVAB1) were manually searched using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) against a nonredundant database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Web site (available at http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), as previously reported (Muzny et al., 2013). If top BLAST hits had species information, that information was assigned to the OTU. If more than 1 top BLAST hits had similar alignment quality, the lowest common taxonomy was used for assignment. For validation, BLAST alignments were reviewed manually for coverage and alignment quality.

Specifically regarding the assignment of reads to BVAB1, BVAB1 sequences were aligned with all OTU sequences using BLAST. It was found that OTU-624 had >99% identity with the BVAB1 sequence (gi|66878803|gb|AY959097.1|). OTU-624 is classified by the RDP classifier as Lachnospiraceae with no genus-level classification given. This OTU-624 sequence also demonstrated the highest degree of homology to BVAB1 when submitted to the NCBI database (13 May, 2014). All OTUs classified as Lachnospiraceae by the RDP Classifier were not BVAB1, although the overwhelming majority (>99%) were most identical to BVAB1. As seen in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, 98 OTUs belonged to Lachnospiraceae, of which 13 were classified to the genus level. Of all OTUs belonging to Lachnospiraceae, 99.33% belonged to OTU-624, which was consistently called BVAB1 by the NCBI database. Of the remaining 85 OTUs classified to the family level, a single OTU (OTU 624) made up 99.44% of all sequences. These findings suggest that Lachnospiraceae sequences classified only to the family level were, indeed, overwhelmingly BVAB1.

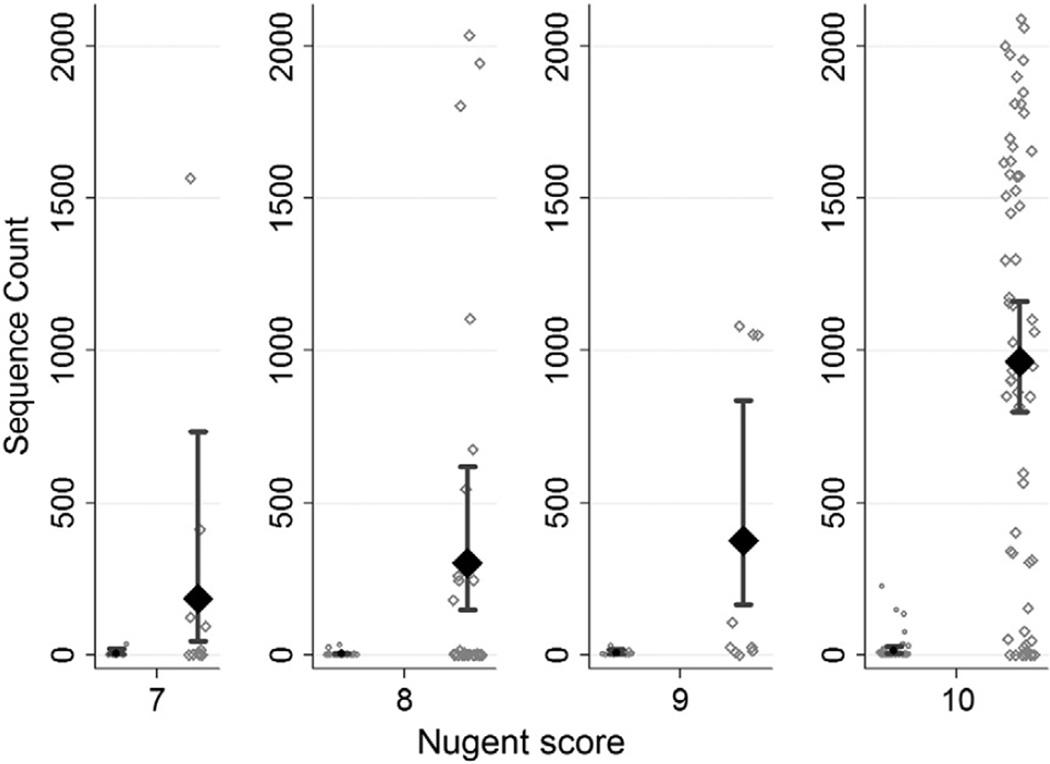

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Generalized linear models with gamma distributions and log link functions were used to estimate means and relative ratios (RR) of sequence reads for comparison between BVAB1 and Mobiluncus spp., stratified by Nugent score. Huber–White robust SEs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. A plot was constructed for visual comparison of the means and 95% CIs.

A total of 112 women with BV were included (Table 1). Demographic characteristics of this cohort have been presented previously (Muzny et al., 2013); 109/112 (97.3%) women were African American. The mean number of raw sequence reads mapped to Mobiluncus spp. or BVAB1 among women in this cohort, stratified by Nugent score (Amsel et al., 1983; Brotman et al., 2010; Nugent et al., 1991; Schwebke et al., 1996), is shown in Fig. 1. There was a statistically significant relative increase in the mean number of reads/sample for BVAB1 compared to Mobiluncus spp. for a Nugent score of 7 (RR: 59; 95% CI [06, 558]; P< 0.001), for a Nugent score of 8 (RR: 112; 95% CI [34, 366]; P< 0.001), for a Nugent score of 9 (RR: 53; 95% CI [17, 169]; P< 0.001), and for a Nugent score of 10 (RR: 71; 95% CI [33, 148]; P< 0.001). The mean number of reads/sample for BVAB1 was highest among women with Nugent scores 9–10.

Table 1.

Sequences of Mobiluncus spp. and BVAB1 stratified by Nugent score among women with BV.

| Nugent score | Na | Mobiluncus spp.b | BVAB1b | Relative ratio (95% CI) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 12 | 3.16 (±2.9) | 185 (±130) | 59 (06, 558) | <0.001 |

| 8 | 30 | 2.70 (±1.3) | 302 (±111) | 112 (34, 366) | <0.001 |

| 9 | 10 | 6.99 (±3.1) | 374 (±154) | 53 (17, 169) | <0.001 |

| 10 | 60 | 13.7 (±5.0) | 963 (±92) | 71 (33, 148) | <0.001 |

Numbers are rounded to nearest whole values.

Mean number of sequences/sample ± SE.

Fig. 1.

Estimated mean plot for mean number of Mobiluncus spp. and BVAB1 reads/sample among the cohort of women (n = 112). Black solid diamond: Estimated mean with 95% CI; black solid circle: Estimated mean with 95% CI; hollow diamonds or circles represent sequence counts of BVAB1 and Mobiluncus spp. reads for each observation, respectively.

In this study, analysis of BVAB1 relative abundance and Nugent score showed that BVAB1 was significantly associated with high Nugent scores, particularly scores of 9–10. These results confirman observation made by Zozaya-Hinchliffe et al. (2010) in which BV cases with a Nugent score of 10 had a high abundance of BVAB1. Using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), Fredricks et al. (2005) have demonstrated that BVAB1 is a thin, curved rod. Mobiluncus is also a thin, curved rod similar to BVAB1, but slightly larger. Although Mobiluncus spp. (i.e. Mobiluncus curtisii and Mobiluncus mulieris) are morphologically similar to BVAB1, their 16S rRNA genes share only 80% nucleotide identity. When the Nugent score was originally developed (Nugent et al., 1991), it was assumed, based on vaginal flora culture data available at the time, that Mobiluncus was the curved gram negative rod observed on vaginal Gram stains. Our data and the Zozaya-Hinchliffe data indicate that this assumption may be incorrect and that, in fact, it is predominately BVAB1 that accounts for the 2 points necessary for Nugent scores of 9 and 10. Our findings also support those reported in a study of bacteria detected by broad-range 16S rRNA gene sequencing and bacterial morphotypes detected in vaginal Gram stains from 220 women with and without BV (Srinivasan et al., 2013). They found evidence that curved Gram-negative rods designated Mobiluncus spp. by Gram stain were more likely to be BVAB1. This study also used species-specific quantitative PCR to determine concentrations of Mobiluncus spp. and BVAB1 and found that, among women with Nugent scores 9–10, the mean concentration of BVAB1 DNA was 100-fold greater than that of Mobiluncus spp. (P< 0.001). Additionally, FISH analyses in this study revealed that the mean number of BVAB1 cells was 2 log units greater than Mobiluncus cells in women with high Nugent scores (P< 0.001).

The majority of participants in our study were African American and represented 3 different groups of women related to sexual activity. Differences in the composition of vaginal microbial communities of women with and without BV of different racial, ethnic, and sexual behavior groups have been noted (Muzny et al., 2013; Ravel et al., 2011; Srinivasan et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2007), and our results may not be generalizable to all women. We were also not able to include an age-matched control group of women who have sex with women (WSW), women who have sex with women and men (WSWM), and women who have sex with men (WSM) with normal vaginal flora to reveal the baseline microbiome in each sexual behavior group. In addition, it is possible that bacteria other than BVAB1 present in high Nugent scoring samples in this study could possess the same morphotype as Mobiluncus spp. Direct visual confirmation using FISH, for example, would be a rational next step in this analysis; however, this pilot study did not have any material available after sequencing was performed. It is of interest to note, however, that other highly abundant taxonomic groups in this sample (including Prevotella, Sneathia, Megasphaera, and Atopobium) (Muzny et al., 2013) do not have morphotypes consistent with that of curved Gram-negative rods (Murray et al., 2007). Nevertheless, despite these limitations, our data are consistent with that of prior studies (Srinivasan et al., 2013; Zozaya-Hinchliffe et al., 2010) and suggest that BVAB1 is the curved Gram-negative rod traditionally identified as Mobiluncus spp. in vaginal Gram stains. Additional studies exploring the association between BVAB1 and high Nugent scores are necessary, as this could impact the definition of the Nugent score.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Heather King, Julia Siren, Tina Barnes, Tim Brown, Haitham Bhagdady, and the MSDH STD Clinic nursing staff for their assistance in recruiting and enrolling patients whose stored vaginal swab specimens were used in this study. In addition, the authors would like to acknowledge the support and assistance of Mary Jane Burton, MD. Bioinformatics support was made possible by the UAB Center for Clinical and Translational Science Grant Number UL1TR000165 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the National Center for Research Resources component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.09.008.

References

- Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KC, Eschenbach D, Holmes KK. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983;74(1):14–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman RM, Klebanoff MA, Nansel TR, Yu KF, Andrews WW, Zhang J, et al. Bacterial vaginosis assessed by gram stain and diminished colonization resistance to incident gonococcal, chlamydial, and trichomonal genital infection. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(12):1907–1915. doi: 10.1086/657320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpes TL, Meyn LA, Krohn MA, Lurie JG, Hillier SL. Association between acquisition of herpes simplex virus type 2 in women and bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(3):319–325. doi: 10.1086/375819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JR, Wang Q, Cardenas E, Fish J, Chai B, Farris RJ, et al. The Ribosomal Database Project: improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D141–D145. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn879. (Database issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(19):2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenbach DA, Davick PR, Williams BL, Klebanoff SJ, Young-Smith K, Critchlow CM, et al. Prevalence of hydrogen peroxide-producing Lactobacillus species in normal women and women with bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27(2):251–256. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.2.251-256.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks DN, Fiedler TL, Marrazzo JM. Molecular identification of bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(18):1899–1911. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier SL, Marrazzo J, Holmes KK. Bacterial vaginosis. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, et al., editors. Sexually transmitted diseases. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. pp. 737–768. [Google Scholar]

- Leitich H, Bodner-Adler B, Brunbauer M, Kaider A, Egarter C, Husslein P. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for preterm delivery: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):139–147. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrazzo JM, Koutsky LA, Eschenbach DA, Agnew K, Stine K, Hillier SL. Characterization of vaginal flora and bacterial vaginosis in women who have sex with women. J Infect Dis. 2002;185(9):1307–1313. doi: 10.1086/339884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrazzo JM, Martin DH, Watts DH, Schulte J, Sobel JD, Hillier SL, et al. Bacterial vaginosis: identifying research gaps proceedings of a workshop sponsored by DHHS/NIH/NIAID. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(12):732–744. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181fbbc95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin HL, Richardson BA, Nyange PM, Lavreys L, Hillier SL, Chohan B, et al. Vaginal lactobacilli, microbial flora, and risk of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and sexually transmitted disease acquisition. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(6):1863–1868. doi: 10.1086/315127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray PR, Baron EJ, Jorgensen JH, et al. Manual of clinical microbiology. 9th ed. Washington DC: ASM Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Muzny CA, Sunesara IR, Martin DH, Mena LA. Sexually transmitted infections and risk behaviors among African American women who have sex with women: does sex with men make a difference? Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(12):1118–1125. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31822e6179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzny CA, Sunesara IR, Kumar R, Mena LA, Griswold ME, Martin DH, et al. Characterization of the vaginal microbiota among sexual risk behavior groups of women with bacterial vaginosis. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29(2):297–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.297-301.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SS, McCulle SL, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl. 1):4680–4687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002611107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwebke JR, Hillier SL, Sobel JD, McGregor JA, Sweet RL. Validity of the vaginal gram stain for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88(4 Pt 1):573–576. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel JD. What's new in bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis? Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19(2):387–406. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel CA, Eschenbach DA, Amsel R, Holmes KK. Curved anaerobic bacteria in bacterial (nonspecific) vaginosis and their response to antimicrobial therapy. J Infect Dis. 1983;148(5):817–822. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.5.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S, Fredricks DN. The human vaginal bacterial biota and bacterial vaginosis. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2008;2008:750479. doi: 10.1155/2008/750479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S, Hoffman NG, Morgan MT, Matsen FA, Fiedler TL, Hall RW, et al. Bacterial communities in women with bacterial vaginosis: high resolution phylogenetic analyses reveal relationships of microbiota to clinical criteria. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e37818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S, Morgan MT, Liu C, Matsen FA, Hoffman NG, Fiedler TL, et al. More than meets the eye: associations of vaginal bacteria with gram stain morphotypes using molecular phylogenetic analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e78633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet RL. Gynecologic conditions and bacterial vaginosis: implications for the non-pregnant patient. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2000;8(3–4):184–190. doi: 10.1155/S1064744900000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(16):5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Brown CJ, Abdo Z, Davis CC, Hansmann MA, Joyce P, et al. Differences in the composition of vaginal microbial communities found in healthy Caucasian and black women. ISME J. 2007;1(2):121–133. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zozaya-Hinchliffe M, Lillis R, Martin DH, Ferris MJ. Quantitative PCR assessments of bacterial species in women with and without bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(5):1812–1819. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00851-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.