Summary

Breast cancer bone micrometastases can remain asymptomatic for years before progressing into overt lesions. The biology of this process, including the microenvironment niche and supporting pathways, is unclear. We find that bone micrometastases predominantly reside in a niche that exhibits features of osteogenesis. Niche interactions are mediated by heterotypic adherens junctions (hAJs) involving cancer-derived E-cadherin and osteogenic N-cadherin, the disruption of which abolishes niche-conferred advantages. We further elucidate that hAJ activates the mTOR pathway in cancer cells, which drives the progression from single cells to micrometastases. Human datasets analyses support the roles of AJ and the mTOR pathway in bone colonization. Our study illuminates the initiation of bone colonization, and provides potential therapeutic targets to block progression toward osteolytic metastases.

Significance

In advanced stages, breast cancer bone metastases are driven by paracrine crosstalk among cancer cells, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts, which constitute a vicious osteolytic cycle. Current therapies targeting this process limit tumor progression, but do not improve patient survival. On the other hand, bone micrometastases may remain indolent for years before activating the vicious cycle, providing a therapeutic opportunity to prevent macrometastases. Here, we show that bone colonization is initiated in a microenvironment niche exhibiting active osteogenesis. Cancer and osteogenic cells form heterotypic adherens junctions, which enhance mTOR activity and drive early-stage bone colonization prior to osteolysis. These results reveal a strong connection between osteogenesis and micrometastasis and suggest potential therapeutic targets to prevent bone macrometastases.

Introduction

When diagnosed in the clinic, breast cancer bone metastases are primarily osteolytic and driven by a vicious cycle between cancer cells and osteoclasts (Ell and Kang, 2012; Kozlow and Guise, 2005; Mackiewicz-Wysocka et al., 2012; Mundy, 2002; Weilbaecher et al., 2011). Bisphosphonates (Diel et al., 1998) and denosumab (Lipton et al., 2007) have been used to inhibit this vicious cycle and achieved a significant delay of metastasis progression but has not improved the patient survival (Coleman et al., 2008; Mackiewicz-Wysocka et al., 2012; Onishi et al., 2010). Recent studies have elucidated roles for various pathways in osteolytic bone metastasis, including TGFβ, hypoxia, Hedgehog, Integrin and Notch (Bakewell et al., 2003; Buijs et al., 2011; Dunn et al., 2009; Heller et al., 2012; Kang et al., 2003; Sethi et al., 2011). Molecular and cellular events that initiate the vicious cycle have also been identified. Specifically, cancer cell-derived VCAM-1 expressed has been shown to engage osteoclast progenitor cells and accelerate their differentiation, which may represent a critical step for microscopic bone metastases to progress into clinically significant lesions (Lu et al., 2011). These findings provide further therapeutic targets to intervene in the osteolytic vicious cycle.

In contrast to our knowledge of overt bone metastases, we know much less about microscopic bone metastases prior to the osteolytic cycle. In fact, such micrometastases may remain asymptomatic for a prolonged period of time before being re-activated to progress, a clinical phenomenon often referred to as metastasis dormancy (Aguirre-Ghiso, 2007). Disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) in the bone marrow have been detected in patients that appear tumor-free (Pantel et al., 2009; Pantel et al., 2008). DTCs may establish their first foothold in the bone marrow by competing with hematopoietic stem cells for the niche occupancy (Shiozawa et al., 2011). However, it remains elusive how cancer cells interact with the niche cells to begin colonization and whether there are intermediate stages between solitary DTCs and osteolytic metastases.

Results

Intra-iliac artery (IIA) injection of breast cancer cells enriches for microscopic bone lesions, allowing inspection of pre-osteolytic bone colonization

We used IIA injection to monitor early-stage bone colonization. This approach selectively delivers cancer cells to hind limb tissues and bone through the external iliac artery (Figure 1A) without damaging local tissues. We characterized this approach and compared it to intra-cardiac (IC) injection, a widely used technique in bone metastasis research. Specifically, we examined: 1) the course of metastatic colonization; 2) organ distribution of disseminated tumor cells; and 3) the potential Darwinian selection process. Cell lines of different subtypes were analyzed to reveal the diverse metastatic behaviors of breast cancer cells.

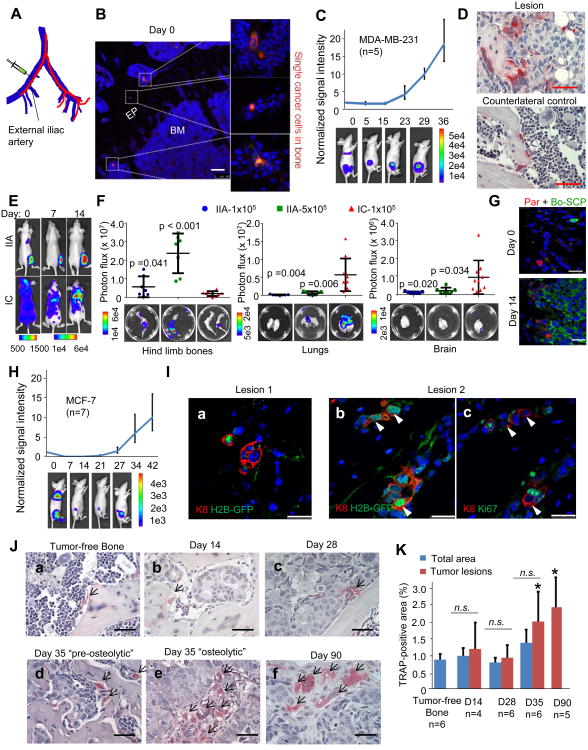

Figure 1. Intra-Iliac Artery (IIA) Injection to Introduce and Model Indolent Bone Lesions.

(A) Diagram illustrates IIA injection. Red and blue lines indicate arteries and veins, respectively.

(B) Fluorescence imaging shows RFP-labeled MDA-MB-231 cells in bone 4 hours after IIA injection. Blue: DAPI, Red: RFP. EP: epiphyseal plate, BM: bone marrow. Scale 100 μm.

(C) MDA-MB-231 bone colonization kinetics after IIA injection. Top, bone colonization growth curves of a representative experiment of 1 × 105 cells injected. Bottom: representative BL images at indicated time points. Error bars 95% Confidence Interval (C.I.).

(D) TRAP staining of the osteolytic bone lesions or counterlateral tumor-free control of MDA-MB-231 IIA model.

(E) Representative BL images showing the organ-distribution of MDA-MB-231 cells introduced by IIA vs. IC.

(F) Quantification of BL signals from hind limb bones, lungs, and brain, respectively, in animals receiving IIA injection of 1×105 cells (IIA-1×105), IIA injection of 5×105 cell (IIA-5×105), or IC injection of 1×105 cell (IC-1×105). Bottom: ex vivo BL imaging. p values were computed between IIA and IC models. Error bars SD.

(G) Bone colonization of admixed MDA-MB-231 parental cells (Par, RFP+) and a bone-tropicsingle cell population (Bo-SCP, GFP+) at indicated time points after IIA injection.

(H) Same as (C) except that 2 × 105 MCF-7 cells were examined. Error bars 95% C.I.

(I) IF co-staining of Keratin 8 (K8, red) and H2B-GFP (green) (a) and (b), or Ki67 (green) (c) on two MCF-7 bone lesions on Day 14. (b) and (c) are consecutive sections.

(J) TRAP staining of normal bone or MCF-7 osteolytic bone lesions after IIA injection. (a) Tumor-free control, (b) Day 14, (c) Day 28, (d) Day 35 “pre-osteolytic”, (e) Day 35 “post-osteolytic”, and (f) Day 90.

(K) Quantification of the TRAP staining of different time points after IIA injection. *: TRAP staining coverage is significantly higher in lesions on Day 35 (p=0.01) and Day 90 (p=0.002) than that of tumor-free control. On Day 90, the bone lesions occupied almost all metaphysis area. Error bars SD.

Scale 25 μm except (B).

See also Figure S1.

MDA-MB-231 cells (ER-/PR-/Her2-) are known to metastasize aggressively in xenograft models. Single cancer cells were readily detectable in the bone marrow immediately after IIA injection (Figure 1B). Strong bone lesions developed within 40 days, as indicated by the bioluminescence (BL) signals (Figure 1C). We stained the bone lesions for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), a hallmark of activated osteoclasts, to ask if the lesions will progress fully. Positive staining was markedly increased compared to tumor-free counter-lateral legs of the same animals, indicating ongoing osteolytic cycle (Figure 1D). Compared to IC injection, cancer cells injected via IIA are predominantly localized to the hind limb bones, sparing lungs, the brain, and other soft tissue organs excessive tumor burdens (Figure 1E and 1F). A larger quantity of cancer cells (e.g., 5 × 105 MDA-MB-231 cells) can be injected through IIA without causing thrombosis-related deaths to animals (Figure 1F), a phenomenon often seen during IC injection. As a result of the highly targeted delivery of cancer cells, full body BL signals strongly correlated with those from dissected bones (Figure S1A). We then designed a clonal competition assay to ask if IIA-injected cancer cells encounter a Darwinian selection process. We admixed RFP-tagged parental MDA-MB-231 cells with a GFP-tagged bone-tropic clone MDA-MB-231 SCP28 (Minn et al., 2005) at a 1:1 ratio. In two weeks, the GFR+/RFP+ shifted dramatically from 1:1 to > 10:1 (Figure 1G and S1B) in both IIA and IC models, reflecting the Darwinian selection process during bone colonization.

We then examined MCF-7 cells (ER+/PR+/Her2-), a cell line experimentally more indolent than MDA-MB-231 cells. IIA injection delivered MCF-7 cells primarily to hind limb. IC injection only resulted in detectable bone colonization in 2/5 mice, whereas IIA injection gave rise to bone lesions in all 5 animals examined (Figure S1C and S1D). The kinetics of MCF-7 bone colonization was slow in the first 2-4 of weeks, but accelerated afterwards (Figure 1H). We used an inducible H2B-GFP system to track the proliferation history of individual cells (Figure S1E) (Fuchs and Horsley, 2011). Although some cancer cells progressed to microscopic lesions in two weeks, a proportion stayed positive for H2B-GFP (Figure 1Ia and 1Ib). Ki67 staining on consecutive sections confirmed that these H2B-GFP+ cells are not proliferative (Figure 1Ic). Therefore, the fates of cancer cells vary upon their arrival in the bone marrow. There was no enrichment of TRAP staining in or surrounding tumor lesions on Day 28 or earlier (Figure 1Ja-1Jc). Starting on Day 35, some lesions showed increased TRAP staining, indicating a transition toward the osteolytic cycle (Figure 1Jd-1Jf and 1K). We used this information to define a “pre-osteolytic” stage. The “pre-osteolytic phase can be much longer in other models such as MDA-MB-361 cells (ER+/PR+/Her2+), which did not exhibit increased TRAP signals until 4 months after IIA injection (Figure S1F and S1G) in a minority of mice (2 out of 10). Taken together, these data show that IIA injection is useful to investigate the early stage of bone colonization prior to the osteolytic vicious cycle.

The microenvironment niche of microscopic bone lesions is primarily comprised of alkaline phosphatase-positive (ALP+) and Collagen I-positive (Col-I+) cells

To ask if bone colonization initiation requires interactions with specific bone cells, we performed IIA injection of MCF-7 cells and MDA-MB-361 cells. We also examined 4T1 and 4TO7 cells into syngeneic Balb/c mice to include the competent immune system. In the pre-osteolytic stage, we conducted immunofluorescence (IF) staining of various cell type markers in conjunction with GFP (for MCF-7, 4T1, and 4TO7 cells) or Keratin 8 (for MDA-MB-361). We found that the niche cells express abundant ALP and Col-I, markers of the osteoblast lineage (Figure 2Aa-2Ah). In contrast, only a minority of lesions directly contact CTSK+ osteoclasts (Figure 2Ai-2Al), and there are largely fewer CTSK+ cells surrounding the microscopic lesions, confirming the pre-osteolytic status.

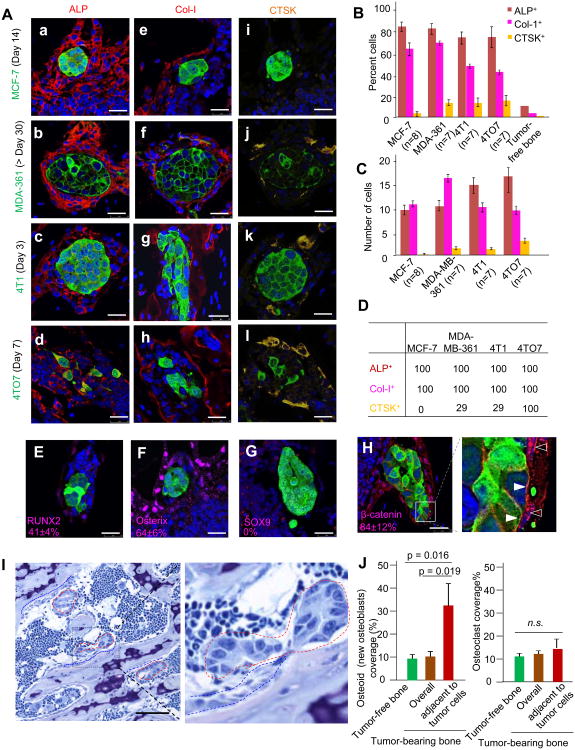

Figure 2. The Microenvironment Niche of Microscopic Lesions Is Primarily Comprised of Cells of the Osteoblast Lineage and Exhibits Active Osteogenesis.

(A) IF co-staining of cancer cells (green) and ALP (a-d), Col-I (e-h), or CTSK (i-l). Cancer cell lines are indicated to the left of images. Time points are indicated in parentheses.

(B) Quantification of indicated cell types in the osteogenic niche. Y axis: percent of indicated cell types that directly contact bone microscopic lesions (first four series) or in tumor-free metaphysis area (the last series).

(C) Same as (B) except that the absolute numbers of indicated cell types are quantified.

(D) Percent microscopic bone lesions that have in their niche at least two cells of the indicated type directly contacting cancer cells.

(E-G) IF staining of RUNX2 (E), Osterix (F) and Sox9 (G) in vicinity of MCF-7 lesions (green) is shown. The frequency of the cells expressing these markers in the microenvironment niche is shown in the corresponding figure in the form of percent ± SD.

(H) IF staining MCF-7 cells (green) and β-catenin (red) on bone lesions is shown. Open arrows point to β-catenin staining localized to nucleus, and solid arrows indicate the membrane localization of this protein.

(I) Representative picture of toluidine blue staining and bone histomorphometry analysis. Red dotted lines enclose bone lesions, and blue dotted lines indicate osteoid. Scale 50 μm

(J) Quantification (n=3 mice) of osteoid (left) and osteoclast (right) coverage based on histomorphometry analyses shown in (I) and Figure S2D, respectively.

Error bars SD. Scale 25 μm except (I).

See also Figure S2.

We then quantitated niche composition. The niche was defined as the single layer of cells that directly contact bone lesions. We quantitated: 1) the frequency of each cell type relative to other cell types, and 2) the frequency of niches containing each cell type. For 1), ALP+ cells account for about 80% of niche cells, Col-I+ cells account for 40-65%, and CTSK+ cells account for less than 20% (Figure 2B). The frequencies of ALP+ and Col-I+ cells are 10% and 3% in the tumor-free metaphysis area, suggesting enrichment of these cells in the niche. The absolute numbers of each cell type were also counted (Figure 2C), leading to the same conclusion. For 2), we assessed the proportion of lesions that have at least two cells of each type in the niche (Figure 2D). All niches contain ALP+ and Col-I+ cells, strongly suggesting that these cells are associated with the progression to multi-cell lesions. CTSK+ cells were only found in a minority of niches in MCF-7, MDA-MB-361, and 4T1 models. In the 4TO7 model, CTSK+ cells were found in all niches examined with a relatively low frequency in each niche (Figure 2B and 2C). We also examined cells expressing Nestin, CD31, αSMA, and CD45 (Figure S2A). None of these cell types are nearly as frequent as ALP+ and Col-I+ cells.

Taken together, these findings suggest that ALP+ and Col-I+ cells are the primary components of the microenvironment niche in early stage bone colonization. In contrast, the abundance of CTSK+ osteoclasts and other cell types in the niche is relatively minor.

The microenvironment niche of microscopic bone lesions exhibits features of osteogenesis

ALP and Col-I are associated with osteogenesis, or bone formation, and have been used as cell markers of osteoblasts (Lynch et al., 1995; Pittenger et al., 1999). Several lines of evidence indicate that the niche of the microscopic lesions involves an active osteogenesis process. First, a variable proportion of the niche cells expressed RUNX2 and Osterix (Osx) (Figure 2E, 2F, and S2B), master regulators of osteogenesis. In contrast, the chondrogenesis regulator SOX9 was not detected in the niche (Figure 2G). Second, the niche cells displayed active canonical WNT signaling as indicated by the nuclear localization of β-catenin (Figure 2H, open arrows), and LEF-1 expression (Figure S2C). WNT signaling is a major driving force of osteogenesis (Baron and Kneissel, 2013; Long, 2012). Of note, β-catenin was also observed along the membrane, suggesting adherens junctions (Figure 2H, solid arrows). Third, histomorphometry analyses showed a 3-5 fold higher osteoid (newly formed osteoblasts) coverage in areas directly adjacent to the lesions (Figure 2I and 2J). In contrast, the osteoclast coverage was not affected (Figure 2J and S2D). Collectively these findings strongly support that the osteogenesis process is associated with the niche of microscopic lesions. Therefore, we will use the term “osteogenic niche” to describe the microenvironment of early-stage bone colonization.

Cells at different stages of osteogenesis (referred to as “osteogenic cells”) promote cancer cell proliferation in a cell-cell contact-dependent manner

To model the interaction with niche cells, we performed co-culture assays using bone cells representing different stages of osteogenesis. Specifically, we used an immortalized human MSC cell line (Liu et al., 2011) and primary murine MSCs of Balb/c mice. We also used MC3T3 cells and FOB1.19 cells to represent more differentiated osteoblast precursor cells and osteoblasts, respectively. The osteogenesis capacity of some of these cells has been validated in vitro (Figure S3A). To ask if cells from other lineages will have similar effects, we chose U937, and RAW264.7, two monocyte lines that can differentiate into osteoclasts.

In 2D cultures, MSCs promote cancer cell growth in a dose-dependent manner (Figure S3B). When the two cell types were separated using Boyden Chamber, the promoting effects were diminished (Figure S3C), suggesting the necessity of direct cell-cell contact. We next performed co-cultures in 3D suspension conditions widely used in mammosphere assays. Interestingly, cancer cells and osteogenic cells formed a heterotypic organoid structure with an “oncogenic shell” and an “osteogenic core” (Figure 3Aa-3Af). This structure was not observed with the same cancer cells labeled with another color or with RAW264.7 cells (Figure 3Ag and 3Ah). Compared to the osteogenic niche structure in vivo (Figure 2A), the relative positioning (or polarity) of cancer and osteogenic cells is inverted in the heterotypic organoids. However, the organoids do recapitulate the extensive and direct contact between two cell types. Both MSC and FOB1.19 cells were able to accelerate tumor cell proliferation, with the effects increasing over time (Figure 3B). The effects of the monocytes were modest (Figure 3B), even after they differentiate into osteoclasts. Cancer cells in the heterotypic organoids exhibited a large increase of Ki67 staining, whereas the osteogenic cells in this structure appeared to differentiate with increased ALP expression (Figure 3C). The effects of MSCs on MCF-7 cells can be reproduced in a number of other cancer cell models as well as using more differentiated osteogenic cells (Figure 3D).

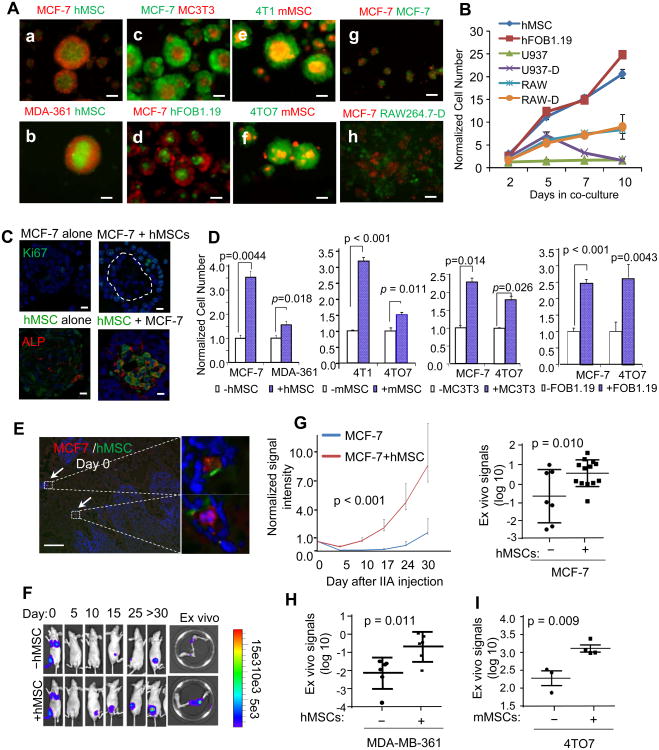

Figure 3. Osteogenic Cells Directly Contact Cancer Cells to Confer Proliferative Advantages and Accelerate Bone Colonization.

(A)(a-h) Fluorescence imaging of the mammosphere or heterotypic organoid structures in 3D cultures (Day 3). Cell names are indicated in each panel in respective fluorescence colors. (g) the admixture of the same MCF-7 cells tagged with two different colors. hMSC: human MSCs; mMSCs mouse (Balb/c) MSCs; RAW264.7-D: differentiated mouse osteoclasts derived from RAW264.7 cells; hFOB1.19: human osteoblast cell line. Scale 50 μm.

(B) Quantification of growth advantages conferred by different cells 3D cultures as a function of time. U937: human monocytes; U937-D: differentiated human monocytes (osteoclasts); RAW264.7: mouse monocytes; RAW264.7-D: differentiated RAW264.7 cells (osteoclast). The data were then normalized to the values of control group for each well (n=3-5).

(C) Upper: IF staining of Ki67 on MCF-7 mammospheres and heterotypic organoids (MCF-7+ hMSCs). The dotted line indicates the border between the two cell types. Bottom: IF staining of GFP (green) and ALP (red) on MSC-spheres (GFP-labeled MSCs alone) and the heterotypic organoids (unlabeled MCF-7+GFP-labeled MSCs). Scale 25 μm.

(D) Quantification of firefly luciferase-labeled cancer cells (as indicated below the x-axes) with or without co-culturing with equal numbers of osteogenic cells (indicated by white/blue boxes) in 3D cultures. The BL signal intensity was measured on Day 3 to reflect the alteration of cancer cell quantities. The data were then normalized to the values of control group for each well (n=3-5).

(E) IF co-staining of RFP (MCF-7 cells) and GFP (hMSCs) within 4 hours after IIA injection. Arrows indicate co-localization of the two cell types. Scale 100 μm.

(F) Representative in vivo and ex vivo BL images showing the bone colonization processes at the indicated time points. 2 × 105 MCF-7 cells with or without equal amounts of MSCs were injected.

(G) Left: BL signal intensity as a function of time after IIA injection of MCF-7 cells, with or without co-injection of human MSCs (n=7, 13 for mono- and co-injection, respectively). Error bars 95% C.I. Right: Quantification of ex vivo BL signals at the terminal time point. The intensity is normalized to the Day 0 values followed by log-transformation.

(H) Same as (G) except that 5 × 105 MDA-MB-361 cells were used for IIA injection.

(I) Same as (G) except for 5 × 103 4TO7 cells and mouse (Balb/c) MSCs were used for IIA injection.

Error bars SD unless otherwise noted.

See also Figure S3.

Provision of exogenous MSCs promotes bone colonization in vivo

To ask if osteogenic cells promote cancer cell proliferation in the bone microenvironment, we performed IIA injection using admixed cancer cells and osteogenic cells at a 1:1 ratio. Upon arrival at the bone marrow, about 50% of MCF-7 cells paired with MSCs via direct cell-cell contact (Figure 3E). The exogenous MSCs significantly decreased the latency and increased the tumor burden of bone colonization (Figure 3F and 3G). Similar results were also obtained using MDA-MB-361 cells (Figure 3H and S3D), and 4TO7 cells (Figure 3I). For the latter, the co-injection was performed on immunocompetent Balb/c mice.

Cancer cells and osteogenic cells form heterotypic adherens junctions (hAJs) using E-cadherin (E-cad) and N-cadherin (N-cad), respectively

The direct and tight contact between microscopic lesions and the osteogenic niche led us to hypothesize that they form cell-cell junctions. The cancer cells used in previous experiments express variable levels of E-cad (Figure S4A). Interestingly, E-cad in cancer cells appears to be required for effects of osteogenic cells, as cancer cell lines without E-cad could not gain proliferative advantages from co-cultured MSCs (Figure S4B). On the other hand, the osteogenic cells primarily express N-cad and OB-cadherin (OB-cad), but not E-cad. Since N-cad and E-cad have been reported to form heterotypic adherens junctions (E-N hAJs) in vitro (Straub et al., 2011), we first focused on the interaction between these two cadherins. Several lines of evidence support the formation of E-N hAJs. First, co-staining of E- and N-cad in heterotypic organoids confirmed that they are exclusively expressed in cancer cells and osteogenic cells, respectively, and are co-localized to the border of the two cell types (Figure 4A, arrows), where β-catenin is also localized (Figure 4B). Likewise, in the bone lesions, E-cad, N-cad and β-catenin were aligned to the cancer-niche interface as well (Figure 4C and 2H). Second, a biochemical assay showed that E-cad was co-immunoprecipiated with N-cad, indicating that they physically interact with each other in vitro (Figure S4C). Third, a Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA), which reflects molecular interaction in situ (Soderberg et al., 2006), showed that E-cad and N-cad are co-localized in vitro and in microscopic bone lesions in vivo (Figure 4D, S4D). Co-staining of N-cad and other markers revealed that N-cad is mainly expressed by ALP+ cells, but not CTSK+ cells, both in the niche of microscopic lesions (Figure 4E) and in the normal bone (Figure S4E). We also asked if endothelial cells are another major source of N-cad. However, endothelial cells only account for a minority of cells in the niche (Figure S2A) and only a small proportion of N-cad is co-localized with the endothelial cell marker, CD31 (Figure S4E). Taken together, these data strongly support that the E-N hAJ mediates the interaction between cancer cells and osteogenic cells in vitro and in vivo.

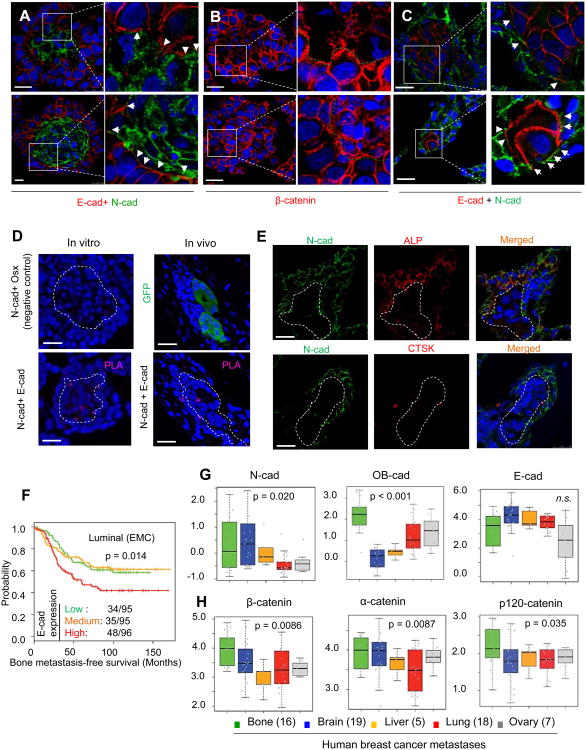

Figure 4. The Heterotypic Adherens Junctions Are Comprised of E-cad of Cancer Cells and N-cads of the Osteogenic Cells.

(A) IF co-staining of E-cad and N-cad on heterotypic organoids between MCF-7 cells and MSCs (upper) or osteoblasts (lower) is shown. Signals from three channels (blue=DAPI, green=N-cad,red=E-cad) are merged. Arrows indicate close proximity or overlap between E- and N-cad signals.

(B) IF staining of β-catenin (red) on heterotypic organoids between MCF-7 cells and MSCs (upper) or osteoblasts (lower). The green dashed line indicates the border between the two cell types.

(C) IF co-staining of E-cad and N-cad on bone lesions of different sizes. Signals are merged from three channels (blue=DAPI, green=N-cad, red=E-cad). Arrows indicate close proximity or overlap between E- and N-cad signals.

(D) Proximity Ligation Assays (PLAs) showing the interaction between E-cad and N-cad. Left: PLAs performed on heterotypic organoids in 3D culture. Right: PLAs performed on bone lesions in vivo. Upper left: a negative control experiment using antibodies against N-cad (membrane) and Osterix (nuclear). Lower left: PLA using N-cad and E-cad antibodies. Purple dots indicate successful reactions. Upper right: GFP staining on bone lesions shows the presence of a metastasis. Lower right: PLA using N-cad and E-cad antibodies. Dashed lines indicate the border of cancer cell cores and microscopic lesions.

(E) IF staining of N-cad (green) and ALP or CTSK on microscopic bone lesions. MCF-7 lesions are unlabeled but indicated by the dashed line. Signals merged from three channels are shown on the right. Blue=DAPI, green=N-cad, red=ALP (upper) or CTSK (lower).

(F) Kaplan-Meier plot of the probability of cumulative bone metastasis-free survival Erasmus (EMC) dataset (GSE5327, GSE2034, and GSE12276) in relationship to the expression of E-cad (CDH1). The numbers of bone metastases and total patients in each group are indicated. p value was calculated by log rank test.

(G-H) Box-whisker plots show the relative expression of indicated genes in breast cancer metastases at different anatomical sites. Grey dots superimposed on each box indicate individual specimen. Sample sizes are shown in parentheses. p values are between bone metastases and all other metastases combined.

Scale 25 μm.

See also Figure S4.

Evidence supporting the role of E-N hAJs in clinical specimens

In the clinic, bone metastases most frequently occur in tumors of the luminal subtype, which are typically ER+ (Kennecke et al., 2010; Smid et al., 2008). E-cad is the major cadherin in this subtype (Figure S4F) (Perou et al., 2000; Sorlie et al., 2001). Our data suggest that E-cad in cancer cells mediates tumor-niche interaction, and might provide an explanation for the bone-tropism of luminal breast cancer. Expression of E-cad is weakly but significantly associated with worse overall survival and distant metastasis-free survival in the METABRIC (Curtis et al., 2012) and Erasmus datasets (Smid et al., 2008), respectively (Figure S4G). A further analysis revealed that E-cad is associated with bone metastasis specifically in the luminal subtype, which expresses a high level of E-cad (Figure 4F and S4F), but not in the basal subtype (Figure S4F and S4H). These results support the hypothesis that E-cad may mediate bone colonization if expressed in cancer cells, the “seeds” of metastasis.

On the other hand, the “soil” of bone metastasis, namely the bone and bone marrow, is largely E-cad-low or -negative (Figure 4C and S4I). The osteogenic cells including MSCs highly express N-cad and OB-cad (Figure S4A). Thus, if AJs are required for cancer cells to colonize the bone, they are likely to be constituted by E-cad of cancer cells and N- or OB- cad of osteogenic cells.

The cadherin expression of human bone metastases retains the features of normal bone, in that N- and OB-cads are expressed at a higher level than metastases in other organs (Figure 4G). This suggests that metastatic bone lesions are heavy infiltrated by osteogenic cells. E-cad is expressed at a slightly lower level (Figure 4G), which is counterintuitive because cancer cells in bone metastases are mostly ER+ and expected to express E-cad (75% of bone metastases versus 47% of other metastases are ER+). A plausible explanation is that the infiltrated mesenchymal cells, rich in N- and OB-cads but scarce in E-cad, may “dilute” the overall level of E-cad of the entire lesion. Indeed, at the transcriptomic level bone metastases exhibit mesenchymal characteristics as reported in previous studies (Zhang et al., 2013).

Bone metastases also differ from other metastases in their enhanced expression of constitutive AJ components including α-catenin, β-catenin, and p120-catenin, suggesting the prevalence of AJ machinery (Figure 4H). Taken together, these data support the importance of AJs in human bone metastases.

The hAJs mediate the cancer-promoting effects of the osteogenic niche

We used EGTA to titrate Ca2+ and disrupt AJs. At 1mM, EGTA significantly decreased cancer cell proliferation in the heterotypic organoids, but had little effects on mammospheres formed by only cancer cells, suggesting a selectively more stringent dependence on Ca2+ of hAJs (Figure 5A). Antagonizing E-cad by a neutralizing antibody (anti-Ecad) or by inducible expression of dominant negative E-cad (EN-Ecad) (Nieman et al., 1999) both led to decreased cancer cell proliferation in the heterotypic organoids (Figure 5B, 5C and S5A). We next perturbed N-cad in osteogenic cells by a neutralizing antibody (anti-Ncad) and siRNAs (si-Ncads). Both treatments resulted in decreased ability of osteogenic cells to promote tumor proliferation (Figure 5D, 5E and S5B). In contrast, siRNAs against OB-cad did not have the same effects (Figure S5C). Finally, N-cad-coated plates conferred a stronger growth advantage to E-cad-expressing cancer cells as compared to other recombinant cadherins (Figure 5F and S5D). Collectively, these results strongly argue that hAJs are required for the osteogenic cell-conferred proliferative effects on cancer cells in vitro.

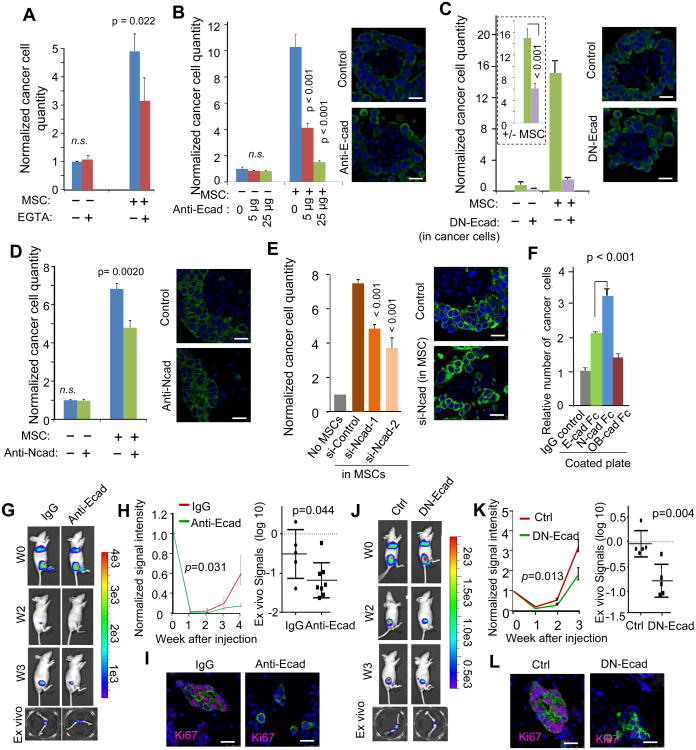

Figure 5. Disruption of the Heterotypic Adherens Junctions Abolishes the Promoting Effects of the Osteogenic niche.

(A) Quantification of firefly luciferase-labeled MCF-7 cells cultured with or without equal amount of MSCs in 3D cultures under treatments of 1mM EGTA. EGTA treatment started on Day 0. BL signals were measured on Day 3 and normalized to untreated MCF-7 cells without MSCs (n=3-5). p values between treated and untreated conditions are indicated. n.s.: not significant

(B-E) Quantification of firefly luciferase-labeled MCF-7 cells with or without co-culture of equal amount of MSCs in under different treatments with neutralizing antibody against E-cad (Anti-Ecad) (B), doxycycline (Dox) to induce the expression of dominant negative E-cad (DN-Ecad) in cancer cells (C), neutralizing antibody against N-cad (anti-Ncad) (D) or siRNAs against N-cad in MSCs (siNcad) (E). BL signals were measured on Day 5 to allow the treatments to take effects, and normalized to untreated MCF-7 cells without MSCs (n=3-5). For (C), the ratio between +MSC and −MSC conditions (+/- MSC) is calculated for each condition and shown in the box of dotted line, and a p value is calculated and shown for the ratios (C). Pictures to the right of the bar graphs show the representative fluorescent imaging of the heterotypic organoids formed by GFP-labeled MCF-7 cells and unlabeled MSCs with or without the corresponding treatment.

(F) Quantification of MCF-7 cells growing in plates coated with the indicated recombinant proteins (n=5).

(G) Representative BL images of mice that were subjected to IIA injection of 5 × 105 MCF-7 cells and treated with E-cad neutralizing antibody (Anti-Ecad) or control IgG are shown. The images at the bottom show extracted bones examined after resection. W0-W3: Week 0 to 3 after IIA injection.

(H) Left: BL intensity (normalized to Day 0 values) as a function of time after IIA injection of 5 × 105 MCF-7 cells with or without treatment of anti-Ecad (n=5 and 8 for IgG and anti-Ecad, respectively). Error bars 95% C.I. p value was determined by fitting a generalized linear model as implemented by R. Right: dot plots show ex vivo BL signal intensity of hind limb bones from the same experiment described in (G).

(I) IF staining of Ki67 and cancer cells in microscopic bone lesions (GFP-tagged MCF-7 cells) with or without the treatment of E-cad neutralizing antibody (Anti-Ecad). Blue=DAPI, Purple=Ki67, and Green=GFP.

(J-L) The same as (G)-(I), respectively, except that doxycycline induction of DN-Ecad was used to treat mice instead of anti-Ecad (n=5 for each group). Error bars 95% C.I.

Error bars SD except (H) and (K).

Scale 25 μm. See also Figure S5.

To test the importance of AJs in vivo, we administered Anti-Ecad on animals receiving MCF-7 cells through IIA. This treatment significantly delayed early bone colonization (Figure 5G and 5H), and resulted in microscopic lesions that appear smaller and less proliferative (Figure 5I). Inducible expression of DN-Ecad achieved similar effects (Figure 5J-5L). The effects of DN-Ecad appear to be specific to bone metastasis, as the inducible expression did not suppress orthotopic tumor growth (Figure S5E). Taken together, these results provide support for an important role of AJs in early-stage of bone colonization.

Interaction between osteogenic cells and cancer cells activates the mTOR pathway in cancer cells

We performed a phospho-antibody array on the heterotypic organoids formed by MCF-7 cells and MSCs. Spheres of MCF-7 cells alone, MSCs alone and their admixture were used as controls to delineate molecular reactions selectively elicited by direct MSC-cancer contact (Figure 6A). Among the total of 39 phospho-proteins, the phosphorylation on Ser235/236 of ribosomal protein S6 (pS6RP[S235/S236]) displayed a marked increase in the heterotypic organoids (Figure 6A). S6RP is a substrate of S6 kinase (S6K), which is in turn a direct substrate of the mTOR kinase. A more quantitative analysis of low-intensity signals of other phophos-proteins on the array revealed a 1.7-1.8 fold increase of pAKT(Ser473) and pAKT(T308) (Figure S6A). To validate the activation of the AKT-mTOR pathway in the heterotypic organoids, we performed Western blots to examine the phosphorylation status of AKT, S6K and 4EBP1. Like S6, S6K and AKT are significantly activated (Figure 6B). We asked if the enhancement of mTOR activity occurs in cancer cells. MSCs exhibited a constitutively high level of p4EBP1(T37/T46), masking any alterations in cancer cells (Figure 6B). However, the S6K activity is exclusively restricted to the cancer cells in the heterotypic organoids (Figure 6C). A similar observation was also made using MC3T3 cells (Figure S6B). Taken together, these results indicate that the direct contact between cancer and osteogenic cells activates the mTOR pathway in cancer cells.

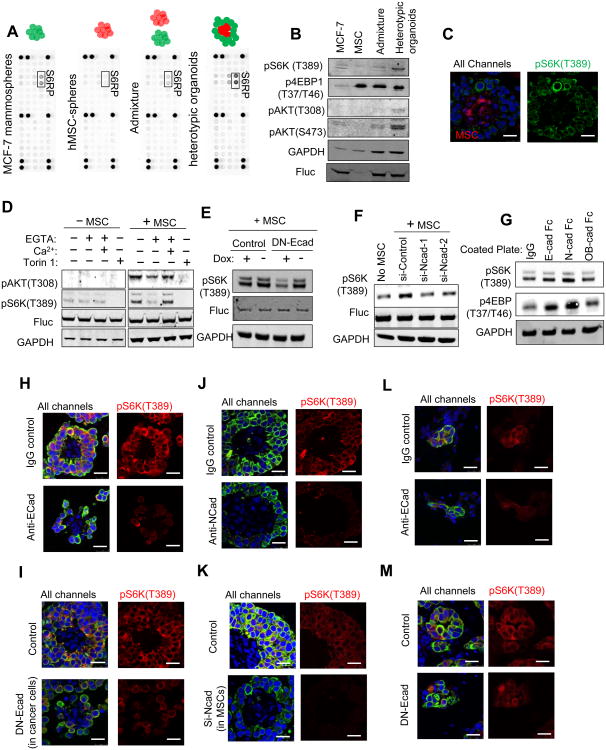

Figure 6. The hAJs between Cancer Cells and the Osteogenic Niche Activate the mTOR Pathway in Cancer Cells.

(A) Phospho-antibody arrays hybridized with protein lysates of MCF-7 mammospheres, MSC-spheres, admixture of pre-formed mammospheres and MSC-spheres, and heterotypic organoids.

(B) Western blots show the expression level of indicated proteins and phospho-proteins in the cell lysates after 4 hour co-culturing with or without equal amount of MSCs.

(C) IF staining of RFP (red) and pS6K(T389) (green) in the heterotypic organoids of RFP-labeled MSCs and unlabeled MCF-7 cells. Left: signals from all three channels (blue=DAPI); Right: signals from green channel only.

(D) Western blots show the level of indicated proteins and phospho-proteins in MCF-7 mammospheres or heterotypic organoids of MCF-7 cells and equal number of MSCs. The protein lysates were prepared 4 hours after the cultures began. MCF-7 cells were tagged with firefly luciferase (Fluc), which was used as the control of cancer cell quantities. Torin 1 is an mTOR inhibitor.

(E) Western blots show the impact of doxycycline (Dox)-induced expression of dominant negative E-cad (DN-Ecad) on pS6K(T389).

(F) Western blots show the impact of the expression of siRNA against N-cad in MSCs on pS6K(T389).

(G) Western blot shows the effects of coated cadherin proteins on pS6K(T389) and p4EBP (T37/T46) in MCF-7 cells.

(H-K) IF staining of GFP and pS6K(T389) of heterotypic organoids formed between MCF-7 cells and MSCs with or without treatment of an E-cad neutralizing antibody (Anti-Ecad) (H), inducible expression of dominant negative E-cad in cancer cells (DN-Ecad) (I), an N-cad neutralizing antibody (anti-Ncad) (J) or expression of siRNA against N-cad in MSCs (K). All channels:blue=DAPI, green=GFP, red =pS6K(T389]

(L-M) IF staining of GFP-labeled MCF-7 cells (green) and pS6K(T389) (red) of microscopic lesions in bones with or without treatment of Anti-Ecad (L) or DN-Ecad (M). All channels: blue=DAPI, green=GFP, red=pS6K(T389],

Scale 25 μm.

See also Figure S6.

The enhancement of mTOR activity requires hAJs in vitro and in vivo

EGTA abolished osteogenic cell-induced increase of mTOR activity in cancer cells, and the abolishment was rescued by Ca2+ (Figure 6D and S6C). Similarly, induction of DN-Ecad also led to a reduction of pS6K(T389) (Figure 6E). N-cad depletion in osteogenic cells decreased their effects on the mTOR activity in cancer cells (Figure 6F). Finally, N-cad-coated plates stimulated the mTOR activity in cancer cells to a greater degree than E-cad and OB-cad (Figure 6G). These data strongly support that hAJs promote cancer cell proliferation via enhancing the activity of mTOR pathway in cancer cells.

To validate the cellular source of the mTOR activity in heterotypic organoids, we examined the in situ IF staining of pS6K(T389) when E-cad in cancer cells was blocked by anti-Ecad (Figure 6H) or by expression of DN-Ecad (Figure 6I), or when N-cad in osteogenic cells was antagonized by anti-Ncad (Figure 6J) or by si-Ncad (Figure 6K). Under these conditions, pS6K(T389) signals remained exclusively to cancer cells, and exhibited significant decrease in intensity.

In vivo, IF staining of pS6K(T389) revealed robust mTOR signaling in multi-cell lesions (Figure S6D, red arrows). Very weak or no pS6K(T389) staining was detected in cancer cells that remain solitary or in loose clusters in the same field (Figure S6D, white arrow), suggesting that the activation of mTOR accompanies bone metastasis progression from single cells to microscopic lesions. Both anti-Ecad or DN-Ecad treatment resulted in a lower pS6K(T389) level (Figure 6L and 6M) in the bone lesions, suggesting that the enhanced mTOR activity in cancer cells is dependent on their interaction with osteogenic cells via hAJs both in vitro and in vivo.

Inhibition of the mTOR pathway reversed the osteogenic cell-conferred growth advantage

We transduced MCF-7 cells with shRNAs against Raptor or Rictor, the necessary components of mTOR Complex 1 and 2, respectively (Figure S7A). The depletion of these proteins in cancer cells partially abolished the growth osteogenic cell-conferred advantages in 3D co-cultures (Figure S7B). Furthermore, MCF-7 cells with Raptor or Rictor knockdown exhibited significantly decreased bone colonization in the pre-osteolytic stage (Figure 7A). In contrast, the orthotopic tumor growth was only modestly affected by the same shRNAs during the same timeframe (Figure S7C). Depletion of Raptor or Rictor in osteogenic cells did not affect their ability to promote cancer cell proliferation (Figure S7D). We then used mTOR inhibitors to achieve a more complete, pharmacological blockade of this pathway. Two inhibitors, Torin 1 (Thoreen et al., 2009) and rapamycin, without affecting the proliferation or survival of osteogenic cells (Figure S7E), potently reduced osteogenic cell-conferred advantages on cancer cells (Figure S7F and S7G). In contrast, the MEK inhibitor, PD98085, failed to achieve the same effects (Figure S7F), arguing against a role of MAPK pathway in this process. Torin 1 also abolished the N-cad-induced proliferation (Figure S7H), suggesting that mTOR mediates the downstream signaling of E-N hAJs.

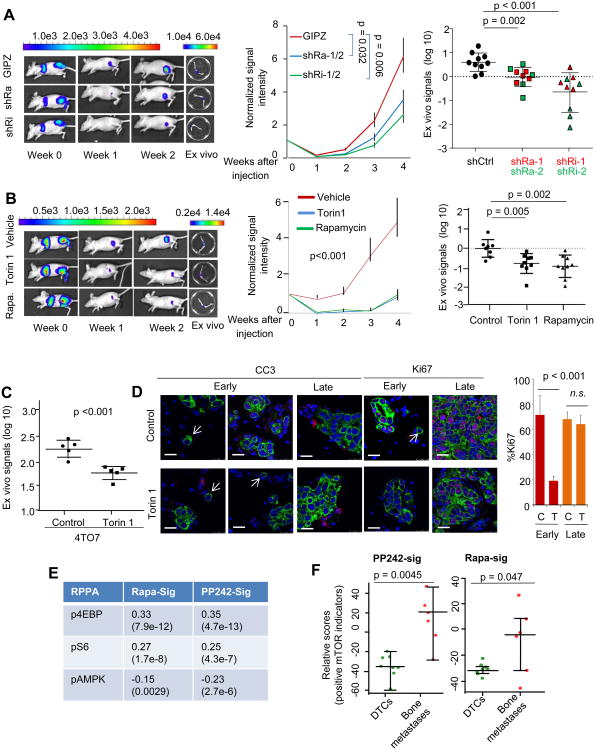

Figure 7. The mTOR Pathway Mediates the Initiation of Bone Colonization.

(A) Left: Representative BL pictures of mice receiving IIA injection of 5 × 105 MCF-7 cells expressing shRNAs against Raptor (shRa) or Rictor (shRi) or control vectors (GIPZ). Middle: BL signal intensity (normalized to Day 0 values) as a function of time after IIA injection of 5 × 105 MCF-7 cells expressing shRNAs against Raptor (shRa) or Rictor (shRi), or vehicle control (n=10 for each group). Mice with cancer cells expressing shRNAs against the same gene were pooled together in this plot (shRa-1/2 or shRi1/2)). The statistical significance was assessed by fitting a generalized linear model as implemented by R. Error bars SEM. Right: Quantification of BL signal intensity of bone lesions at the terminal time point (Week 4). Different shRNAs against the same gene (shRa-1/2 or shRi1/2) were distinguished by color. Error bars SD.

(B) Left: Representative BL pictures of mice that were subjected to IIA injection of 5 × 105 MCF-7 cells and treated with indicated drugs are shown. Middle: BL signal intensity (normalized to Day 0 values) as a function of time after IIA injection of 5 × 105 MCF-7 cells under the treatment of Torin 1, rapamycin, and vehicle control (n=8-9 for each group). The statistical significance was assessed by fitting a generalized linear model as implemented by R. Error bars SEM. Right: Dot plots show BL signal intensity of bone lesions at the terminal time point (Week 4) in the same experiment. Error bars SD.

(C) Same as (B) except that 5 × 103 4TO7 cells are used instead of MCF-7 cells. Error bars SD.

(D) Left: Cleaved Caspase 3 (CC3, red) and Ki67 (red) staining of bone metastases at different time points is shown. Cancer cells are stained with Keratin 8 (green). Arrows indicate solitary cancer cells. Scale 25 μm. Right: Quantification of Ki67-positive cells in bone lesions at different stages with or without treatment of Torin 1 is shown (n=5, Error bars SD). C=control, T= Torin 1 treatment, Early: Day 21 after injection. Late: Day 42 after injection.

(E) Validation of the rapamycin-responsive signature (Rapa-Sig) and PP242-responsive signature (PP242-Sig.) in TCGA dataset. The signature scores were calculated as specified in Experimental Procedures. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed between the scores and the level of phospho-proteins in Reverse Phase Protein Array (RPPA). The p values were determined based on Student's t-tests and are shown in parentheses below the correlation coefficients.

(F) PP242-Sig. and Rapa-Sig were applied to GSE14776. The scores are tabulated by the sample type (DTC vs overt bone metastases). Error bars SD.

See also Figure S7.

In vivo treatment of Torin 1 or rapamycin significantly delayed bone colonization of MCF-7 cells (Figure 7B). Torin 1 treatment of 4TO7 bone lesions in Balb/c mice resulted in a similar effect (Figure 7C). Solitary disseminated cancer cells are largely Ki67- and cleaved Caspase 3-negative in both treated and control groups, suggesting that these cells are quiescent and do not respond to Torin 1 (Figure 7D, white arrows). This is consistent with the fact that solitary cancer cells in the bone marrow in general possess low mTOR activity (Figure S6D and S7I). Multi-cell lesions, on the other hand, exhibited decreased proliferation under Torin 1 treatment (Figure 7D), although the survival/apoptosis appeared unaffected. Interestingly, at later stages of bone colonization, although the mTOR activity remained high (Figure S7I), Torin 1 treatment no longer delayed bone colonization (Figure 7D and S7J). These results suggest that the bone colonization process may be dependent on the enhanced mTOR activity specifically at the early stage when cancer cells are associated with the osteogenic niche. In later stages, although the mTOR activity might still be on, it may not be essential for the further progression of bone metastases.

The increase of mTOR activity is associated with bone metastasis progression from DTCs in human breast cancer

We interrogated the mTOR activity in a previously published dataset comprised of transcription profiles of human DTCs and overt bone metastases (Cawthorn et al., 2009). The mTOR activity was inferred using two signatures derived by profiling transcriptional responses of various cell line models to rapamycin (Wei et al., 2006) and PP242 treatment (Wang et al., 2011). Like Torin 1, PP242 is a newly developed mTOR inhibitor targeting both mTORC1 and mTORC2 (Hsieh et al., 2010). We first applied these signatures to the TCGA microarrays with matched RPPA data (TCGA, 2012), and confirmed their correlation with upstream regulators and downstream substrates of the mTOR pathway (Figure 7E). Using these signatures, we found that the predicted mTOR activity is significantly higher in bone metastases compared to in DTCs (Figure 7F), supporting that enhancement of mTOR activity is associated with bone metastasis progression.

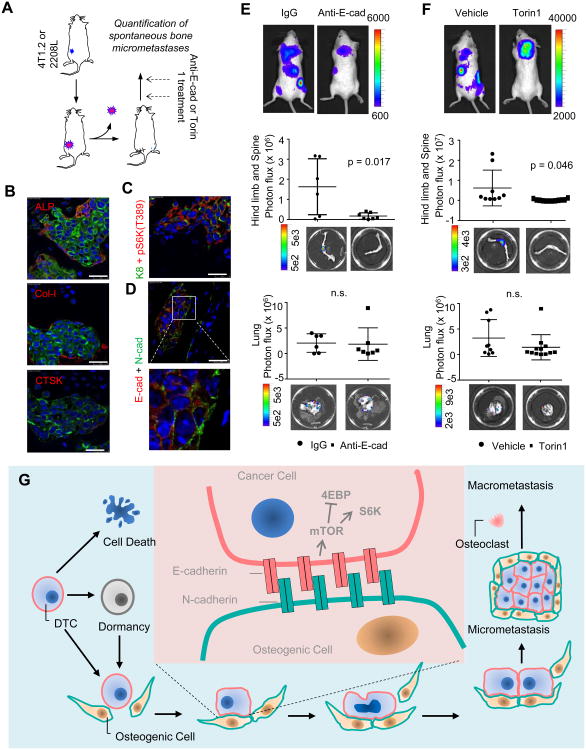

The osteogenic niche of spontaneous bone micrometastases

To validate our findings in spontaneous metastasis models, we utilized the 4T1.2 cell line, which was shown to give rise to spontaneous metastasis to bone and other organs (Figure S8A) (Eckhardt et al., 2005). In addition, we identified one tumor line derived from p53-null Balb/c mice (Herschkowitz et al., 2012), termed 2208L, which spontaneously metastasizes to bone and bone marrow as indicated by tumor-specific PCR (Figure S8B). Both 4T1.2 and 2208L express E-cad (Figure S8C). We examined hind limb bones two weeks or one month after resection of orthotopic 4T1.2 or 2208L tumors, respectively (Figure 8A). All microscopic multi-cell lesions we could observe in the bone (n=3) directly contacted ALP+ and Col-I+ cells, but not CTSK+ cells (Figure 8B and S8D). Further experiments revealed that 4T1.2 spontaneous bone metastases exhibited positive pS6K(T389) staining (Figure 8C) and expressed E-cad that was co-localized with the N-cad of the niche (Figure 8D). We next investigated the effects of anti-E-cad and Torin 1 treatment on spontaneous bone metastases. Orthotopic 4T1.2 tumors were resected prior to the treatment of anti-E-cad (Figure 8E) or Torin 1 (Figure 8F). While anti-Ecad and Torin 1 significantly decreased bone metastases they had little effects on lung metastasis (Figure 8E and 8F) or residual orthotopic tumors (Figure S8E), suggesting bone specificity. Similar effects of Torin 1 treatment on 2208L bone lesions were observed using a qPCR-based approach. (Figure S8F). Taken together, these results strongly support the conclusion that hAJs and mTOR signaling drives early-stage bone colonization in both IIA and spontaneous models.

Figure 8. The Osteogenic Niche and the mTOR pathway Mediate Spontaneous Bone Metastases.

(A) Schematic showing the experimental design to investigate spontaneous bone metastases in the 4T1.2 or 2208L models.

(B)-(D) 4T1.2 spontaneous bone micrometastasis. (B) IF co-staining of Keratin 8 (for cancer cells, green) and ALP, Col-I, or CTSK (red). (C) IF co-staining of Keratin 8 (K8) (green) and pS6K(T389) (red). (D) IF co-staining of E-cad (red) and N-cad (green).

(E) Top: Representative BL pictures show spontaneous metastases arising from orthotopic 4T1.2 tumors with or without treatment of anti-E-cad antibody. Middle: Quantification of spontaneous 4T1.2 bone metastases with treatment of anti-E-cad antibody or the IgG control. Bottom: representative ex vivo BL images. Bottom: lung metastases of the same mice are quantified and shown. n=6 and 7 for IgG and anti-Ecad, respectively. n.s.: not significant.

(F) Same as (E), except that Torin 1 or its vehicle were used instead of E-cad antibody or IgG.n=9 and 12 for Vehicle and Torin 1 treatment, respectively. n.s.: not significant.

(G): A model of osteogenic niche-dependent early-stage bone colonization. DTC: disseminated tumor cells.

Error bars SD. Scale 25 μm.

See also Figure S8.

Discussion

We have characterized the microenvironment niche of bone microscopic lesions, which is primarily comprised of cells in the osteoblast lineage and possess osteogenic potential (Figure 8G). Our data showed that a substantial proportion of the osteogenic cells still express Osterix and RUNX2, markers of osteo-progenitor cells, suggesting an ongoing osteogenesis process. Thus, the microenvironment niche of bone micrometastases is dynamic. An important question is the relationship between the osteogenic niche observed here with the long-proposed endosteal osteoblastic niche harboring hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) (Calvi et al., 2003)? A previous study showed IC injection of prostate cancer cells increased HSC frequency in the blood, suggesting that cancer cells may compete against HSC for niches as the first foothold of bone colonization (Shiozawa et al., 2011). Our data cannot directly test this hypothesis as the exact constitution and organization of the HSC niche remain largely uncertain. The answers to these questions will need to be addressed in future studies.

Our data indicate an important role of AJs in early-stage bone colonization. When E-cad-positive cancer cells disseminate to the bone and bone marrow as single cells, the first AJs they are able to form are likely to be E-N hAJs, because of the scarcity of E-cad and the abundance of N-cads in the microenvironment (Figure 8G). Thus, the formation of E-N hAJs may represent the first critical step of bone colonization. After the first few cell divisions, E-E homotypic junctions will form between daughter cancer cells, which may contribute to fuel further progression, although according to our data E-N heterotypic AJs may still confer a stronger proliferative advantage. Other cadherins expressed in cancer cells may also be involved in heterotypic AJs. In fact, 4TO7 only expresses a minimal level of E-cad (Figure S4A), which is consistent with previous studies (Korpal et al., 2011). Correspondingly, the effects of E-cad neutralization were modest in 4TO7 co-culture assays (Figure S5A), despite the similar dependency of these cells on osteogenic cell-derived N-cad (Figure S5B) and the mTOR pathway (Figure S7F). Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that other cadherins contribute to the formation of hAJs with N-cad.

We found that the enhancement of the mTOR pathway is a consequence of E-N hAJs. The mTOR signaling has been implicated in resistance to endocrine therapies in ER+ breast cancer (Boulay et al., 2005; Schiff et al., 2004). A recent Phase III clinical trial on postmenopausal endocrine resistant breast cancer revealed an increase in progression-free-survival when Everolimus, a rapamycin analog, was used in combination with an aromatase inhibitor Exemestane (Baselga et al., 2012). 76% of patients in this trial had bone metastases, indicating that the mTOR inhibitor may efficiently inhibit the progression of metastatic colonization in bone. However, another Phase III trial using a different combination of rapalog and aromatase inhibitor as the first-line therapy failed to achieve the same efficacy (Wolff et al., 2013). Thus, additional studies are required to understand how different mTOR inhibitors act on breast cancer of various subtypes, in distinct stages, at different sites, and with diverse treatment history. Our findings and experimental models should help facilitate the understanding of how mTOR functions to promote progression from single DTCs to microscopic bone metastases.

Experimental Procedures

Animal Studies

All animal work was done in accordance with a protocol approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Intra-iliac artery injection

Anesthetized mice were restrained on a plastic board. An 1.5 cm incision was made on the skin along the line between femoral and ilium bones. Blunt dissection was performed to separate muscles and reveal common iliac artery. Cancer cells suspended in 0.1 ml PBS were injected using 31G needles. A cotton tip was used to press injected artery until the bleeding stopped (in about 10 minutes). The wound was then sutured, and the mouse was monitored until awake and moving normally.

Spontaneous bone metastasis assay

Balb/c mice received mammary fat pad transplantation of 1-2 mm fragments of 2208L tumors or 5 × 105 4T1.2 cells suspended in 100 μl PBS. When tumors reached ∼1 cm3, surgical resection was used to remove the tumors. Mice are excluded from experiments if their tumor size is exceptionally large or small (2 standard deviation from the group mean), or the residual tumor signals were exceptionally strong after resection. The remaining mice were randomized into different treatment groups, and closely monitored for a month (2208L) or two weeks (4T1.2) before sacrificed. Immediately after euthanasia, hind limb bones (for 2208L and 4T1.2 models), spines (4T1.2) and lungs (4T1.2) were extracted for further analyses. In 2208L experiments, genomic DNA was purified from homogenized tissue. Quantitative PCR was then conducted using the primer sequences: 5′-CTCTGATGCCGCCGTGTT-3′ and 5′- TGCCTCGTCTTGCAGTTCATT-3′ to specifically detect cells with the p53-KO locus. The actin gene was used as the control. The relative quantity was calculated using the formula, log2(10000/ΔCt) (Eckhardt et al., 2005). The Student's t-test was used to compute the p value.

See the rest of animal study procedures in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Quantification of cells in the microenvironment niche

Toluidine blue and TRAP staining were performed, and montaged images of femur were taken and analyzed in the BCM bone Histomorphometry Core following standard procedures. We defined the microenvironment niche as the collection of stromal cells immediately adjacent to and directly contacting cancer cells, where there was neither discernible space between the plasma membranes of the two cells nor additional nucleus between the nuclei of the two cells.

Statistical Tests

Differences among growth curves were assessed using generalized linear models in the “statmod” package of the R statistical software. Values at growth curve time points were first converted to log scale to approximate the normal distribution, and then used to derive the standard deviation or 95% confidence interval of the mean using standard procedures. For other analyses, Student's t tests were used unless noted otherwise.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Related to Figure 1. Intra-Iliac Artery (IIA) Injection as a Novel Approach to Introduce and Model Indolent Bone Lesions. (A) Scatter plots between in vivo bioluminescence signals at hind limbs against ex vivo signals from extracted bones, both log-transformed. Pearson correlation coefficient is shown and the p value was computed using Student's t-test. (B) Bone colonization of admixed MDA-MB-231 parental cells (Parental) and a MDA-MB-231 bone-tropic single cell progeny (Bo-SCP) at indicated time points were quantified by qPCR on RFP and GFP tags, respectively. (C-D) Same as Figure 1E and 1F except that 5 × 105 MCF-7 cells were used to compare IIA and IC injection. (E) Histogram of fluorescence intensity of H2B-GFP transduced MCF-7 cells under various treatments and time points by FACS. +Dox: MCF-7 cells treated with Dox for at least 3 days to induce H2B-GFP expression. –Dox, 3/8/14/21 days: H2B-GFP-induced cells are subjected to Dox withdrawal for 3, 8, 14, or 21 days. Dox + Aphidicolin: H2B-GFP induced cells are subjected to Dox withdrawal and Aphidicolin (a cell cycle inhibitor) treatment. (F-G) Same as Figure 1C and 1D, respectively, except that 5 × 105 MDA-MB-361 cells are examined. Scale 25 μm. Error bars (D) SD (F) 95% Confidence Interval.

Figure S2. Related to Figure 2. The Microenvironment Niche of Microscopic Lesions Is Primarily Comprised of Cells of the Osteoblast Lineage and Exhibits Active Osteogenesis. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of Nestin αSMA, CD31, and CD45 on microscopic bone lesions formed by MCF-7 cells 14 days after IIA injection is shown. MCF-7 cells are labeled with GFP and are stained green. The number below each marker indicates the frequency of the cells stained positive for this marker in the niche. Scale 25 μm. (B) Left: Bar graphs show the quantification of indicated cell types in the microenvironment niche. Right: Percent microscopic bone lesions that have in their niche at least two cells of the indicated type directly contacting cancer cells. Error bars SEM. (C) Immunofluorescence staining of LEF1 on microscopic bone lesions formed by MCF-7 cells 14 days after IIA injection is shown. Scale 25 μm. (D) Representative picture of TRAP staining for bone histomorphometry analysis. Black arrows indicate the dark red TRAP staining of activated osteoclasts. Red dotted lines indicate area of microscopic metastases. Scale 50 μm.

Figure S3. Related to Figure 3. Osteogenic Cells Directly Contact Cancer Cells to Confer Proliferative Advantages and Accelerate Bone Colonization. (A) Osteogenesis assays of MSCs from different sources. Scale 10 μm. (B) Bar graphs show the quantification of cancer cells admixed with various ratios of MSCs in 2D co-cultures. Cancer cells used in each experiment are indicated below the bars. MSCs are chosen to match the species of cancer cells (human MSCs for MDA-MB-361 and MCF-7 cells, and mouse MSCs for 4T1 and 4TO7 cells). Bioluminescence signal intensity is used for the quantification, which is measured on Day 7 under each condition and normalized to that of untreated cancer cells. The color coding of different MSC to cancer cell ratios is indicated above the bars. Error bars SD (n=3-5 biological replicates). (C) Bar graphs show the quantification of cancer cells admixed with various ratios of MSCs in Boyden Chamber assays. The experimental procedures and quantification were the same as described in (B) except for the usage of Boyden Chambers. The color coding of different MSC to cancer cell ratios is indicated above the bars. Error bars SD (n=3-5 biological replicates), n.s.: no statistical significance. (D) Bioluminescence signal intensity (normalized to Day 0 values) as a function of time after IIA injection of 5 × 105 MDA-MB-361 cells (n=6 for each group, error bars 95% C.I.). p value is computed by fitting a generalized linear model using R.

Figure S4. Related to Figure 4. The Heterotypic Adherens Junctions Are Comprised of E-Cadherin of Cancer Cells and N-Cadherins of Osteogenic Niche Cells. (A) Western blots show the expression of indicated proteins in various osteogenic, cancer, and other cell types. Cad: cadherin, mMSC: murine (Balb/c) MSCs, hMSC: human MSCs, 3T3: MC3T3 cells, MDA-361: MDA-MB-361 cells, U937-D: differentiated osteoclasts derived from U937 cells, RAW264.7-D: differentiated osteoclasts derived from RAW264.7 cells, MDA-436: MDA-MB-436 cells. (B) Bar graphs show growth advantages conferred by hMSCs on indicated cancer cells in suspension medium as a function of time. The data were normalized to the values of control group for each well (“Normalized Cell Number”). Error bars SD (n=3-5 biological replicates). (C) Co-Immunoprecipitation assay shows E-cadherin co-precipitates with N-caderin. Proteins were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies against N-cadherin, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting both E and N cadherin antibodies. (D) Proximity Ligation Assays (PLAs) performed on heterotypic organoids formed by MCF-7 cells and hMSCs. Left: A negative control experiment using antibodies against N-cadherin (membrane) and Osterix (nuclear). Due to the different cellular locations of the two molecules, no reactions are expected. Middle: A positive control experiment using antibodies against N-cadherin and β-catenin. The two proteins are known to interact to form adherens junctions. Right: PLAs using antibodies against N-cadherin and E-cadherin. A high-magnification picture is shown in Figure 4G. Scale 100 μm. (E) Immunofluorescent co-staining of N-cadherin and ALP, CTSK or CD31 on mouse hind limb bone in tumor-free area is shown. Pictures show signals merged from three channels (blue=DAPI, green=N-cadherin, red = ALP, CTSK or CD31. Scale 25 μm. (F) Box-whisker plots show CDH1 gene expression (encoding E-cadherin) in different subtypes of breast cancer in the TCGA dataset. The statistical difference between ER- and ER+, and between Luminal-A/B (lumA and LumB) and other subtypes are highly significant (p < 0.0001). (G) Kaplan-Meier plot of the probability of cumulative 10-year overall survival in the METABRIC dataset (Left) or cumulative overall survival in the Erasmus dataset (Right) in relation to the expression of E-cadherin (CDH1). All patients are divided into three groups of equal numbers with low-, medium- and high-expression of E-cadherin. The number of events (deaths) and the total number of patients (excluding those without known survival time) are indicated for each group. p value was calculated according to log rank test. (H) Kaplan-Meier plot of the probability of cumulative bone metastasis-free survival in non-luminal subtype breast cancer patients of the Erasmus (EMC) dataset in relation to the expression of E-cadherin (CDH1). All patients are divided into three groups of equal numbers with low-, medium- and high-expression of E-cadherin. The number of events (deaths) and the total number of patients (excluding those without known survival time) are indicated for each group. n.s.: not significant according to log rank test. (I) Immunofluorescent co-staining of E-cadherin and N-cadherin on mouse hind limb bone in tumor-free area is shown. The picture shows signals merged from three channels (blue=DAPI, green=N-cadherin, red = E-cadherin. Scale bars 50 μm.

Figure S5. Related to Figure 5. Disruption of Adherens Junctions Abolishes the Promoting Effects of the Osteogenic Niche. (A) Bar graph shows the quantification of firefly luciferase-labeled cancer cells with or without co-culture of equal amount of indicated osteogenic cells in 3D suspension cultures under treatment with 25 μg/ml neutralizing antibody against E-cadherin (Anti-Ecad). Bioluminescence signals were measured on Day 5 to allow the treatments to take effects, and normalized to untreated 4T1 cells without MSCs. Error bars SD (n=3-5 biological replicates). If the effects of treatment are not significant (n.s.) on cancer cells alone, p values are shown to indicate the statistical significance between treated and untreated groups in the presence of MSCs. Otherwise, the ratio between +FOB and −FOB conditions is calculated for each condition (+/-FOB) and shown in the box of dotted line), and a p value is calculated and shown between the ratios. n.s: not significant. (B) Same as Figure 5E except that hFOB1.19 cells (FOB) are used instead of MSCs, and multiple cancer cell lines are used as indicated in each panel. Error bars SD (n=3 biological replicates). p values between treated and untreated conditions are indicated; n.s: not significant. (C) Same as Figure 5E except that hFOB1.19 cells (FOB) are used instead of MSCs and siRNAs against OB-cadherin was used instead of those against N-cadherin. Error bars SD (n=3 biological replicates). (D) Same as Figure 5F except that 4T1 or MDA-361 cells are used instead of MCF-7. Error bars SD (n=3 biological replicates). p values between treated and untreated conditions are indicated. (E) Left: Western blots show the expression of indicated proteins in MCF-7 cells expressing inducible DN-Ecad or the pINDUCER vector as a control. Right: Growth curves of orthotopic tumors formed by 1.5 × 106 MCF-7 cells with or without Dox-induced overexpression of DN-Ecad are shown. Error bars SEM (n=5 for each group).

Figure S6. Related to Figure 6. The Heterotypic Adherens Junctions between Cancer Cells and the Osteoblastic Niche Activate the mTOR Pathway in Cancer Cells. (A) Bar graphs show the quantification of chemiluminescence signals of indicated proteins on the phospho-antibody arrays exhibited in Figure 6A. Quantification was performed using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor, Nebraska). The fold change between the signal intensity of heterotypic organoids and that of MSC/cancer admixture is indicated for each phospho-protein. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of GFP and pS6K(T389) on mammospheres formed by MCF-7 cells alone, or on heterotypic organoids formed between MCF-7 cells and MC3T3 cells is shown. MCF-7 cells are labeled with GFP. Images in the left column show signals from all three channels (blue=DAPI, green=GFP, red = pS6K[T389]), whereas those in the second column show signals from red channel only. The exposure time is the same for all pictures. Scale 25 μm. (C) Western blots show the level of indicated proteins and phospho-proteins in mammospheres or heterotypic organoids. The protein lysates were prepared four hours after the cultures began. Cancer cells are labeled with firefly luciferase (Fluc), which was used as control of cancer cell quantities. (D) Immunofluorescent staining of GFP-labeled MCF-7 cells (green) and pS6K(T389) (red) on two representative microscopic lesions in bone is shown. White arrows indicate cancer cells that remain single or in loose clusters presumably before the initiation of colonization. Red arrows indicate multi-cell lesions in the same field. The first column shows an overlay picture of all three staining colors, the second column shows the pS6K signal only (red) and the third column shows pS6K signal of magnified area with solitary tumor cell (upper panel) and of magnified area containing microscopic lesion (lower panel) to exhibit a comparison of pS6K signals in lesion 1 and a single cancer cell nearby. Scale 25 μm.

Figure S7. Related to Figure 7. The mTOR Pathway Mediates the Initiation of Bone Colonization. (A) Western blots show the expression of indicated proteins in MCF-7 cells expressing shRNAs against Raptor (shRa-1 and shRa-2), Rictor (shRi-1 and shRi-2), or the empty vector control (GIPZ). (B) Bar graphs show the quantification of MCF-7 cells with and without admixture of equal amount of MSCs (left) or hFOB1.19 (FOB) cells (right). MCF-7 cells were transduced with constructs expressing shRNAs against Raptor (shRa-1 and shRa-2) or Rictor (shRi-1 and shRi-2), or vehicle control (GIPZ). The cell number was assessed by bioluminescence signal intensity on Day 5, and normalized to that of control MCF-7 cells. Osteogenic cell-conferred advantage values are shown in dotted boxes. p values are shown to indicate the statistical significance between the respective treatment and vehicle control (DMSO). Error bars SD (n=3-5 biological replicates). (C) Growth curves of orthotopic tumors formed by 1 × 106 MCF-7 cells expressing shRNAs against Rictor or Raptor, or control vectors. Error bars SEM (n=6 for each group). Significant difference does not show up until the 5th week, the timeframe of pre-osteolytic bone colonization (indicated by the grey dashed line). *: Tumors expressing shRNA against Rictor show significant difference from the GIPZ control group (p<0.05); #: Tumors expressing shRNA against either Rictor or Raptor show significant difference from the GIPZ control group (p<0.05). (D) Effects of the expression of shRNAs against Raptor (shRa) and Rictor (shRi) in FOB1.19 cells (FOB) on cancer cell proliferation. Error bars SD (n=3 biological replicates). (E) Quantification of MSC numbers with or without admixture of equal amount of MCF-7 cells and Torin 1 treatment in suspension medium. MSCs are labeled with renilla luciferase and bioluminescence intensity was used to quantify MSCs. Error bars SD (n=3 biological replicates). (F) Bar graphs show the quantification of MCF-7 cells (left) or 4TO7 cells (right) with and without admixture of equal amount of MSCs and under the treatment of indicated drugs. Inhibitor treatments start on Day 0. The cell number was assessed by bioluminescence signal intensity on Day 3, and normalized to that of untreated MCF-7 cells. Osteogenic cell-conferred advantage values are shown in dotted boxes. p values are shown to indicate the statistical significance between the respective treatment and vehicle control (DMSO). Error bars SD (n=3-5 biological replicates). (G) Same as (F) except that MC3T3 or hFOB1.19 cells are used instead of MSCs, or MDA-MB-361 and 4T1 cells are used instead of MCF-7 cells. If the effects of treatment are not significant (n.s.) on cancer cells alone, p values are shown to indicate the statistical significance between treated and untreated groups in the presence of osteogenic cells. Otherwise, the ratio between co-culture and mono-culture conditions is calculated for each condition (+/- FOB, +/-MSC, or +/- mMSC) and shown in the box of dotted line), and a p value is calculated and shown between the ratios. Error bars SD (n=3 biological replicates) (H) Quantification of MCF-7 cells under the indicated conditions. The N-cadherin-conferred advantage (defined by cell quantity on N-cadherin-coated plates divided by cell quantity on lgG-coated plates under otherwise the same condition) is shown in the box. The number in the box indicates statistical significance of the difference between Torin 1-treatment and control. Error bars SD (n=3 biological replicates). (I) Immunofluorescence co-staining of Keratin 8 (K8) (green) and pS6K(T389) (red) on bone lesions formed by MCF-7 cells 42 days after IIA injection is shown. Left panel: three channels overlaid (blue=DAPI). Right panel: red channel only. The white arrow indicates a cancer cells that remains solitary with low mTOR activity. Scale 50 μm. (J) Dot plots show the quantification of bioluminescence signal increase between Day 28 and Day 42 after IIA injection with or without Torin 1 injection. Error bars SD.

Figure S8. Related Figure 8. The Osteogenic Niche and the mTOR pathway Mediate Spontaneous Bone Metastases. (A) Representative bioluminescence pictures of 4T1.2-transplanted animals and the ex vivo imaging of extracted organs (from top to bottom: the lungs, the spine, and the hind limb). (B) PCR amplification of DNA fragment specific to the p53-null breast cancer genome is shown. Positive controls are cancer cells from p53-null murine tumors. Negative controls include bone marrows from tumor-free mice and non-p53-null tumors. Four individual mice were examined, two of which exhibited positive results indicating presence of spontaneous bone micrometastases in bone. (C) Two 2208L tumors and the 4T1.2 cell line were subjected to Western blotting for E-cadherin expression. (D) Representative spontaneous bone microscopic lesions of the 2208L model are examined by immunofluorescence co-staining of osteoblasts, osteoclasts and cancer cells, using ALP/Col-I/CTSK (red) and Keratin 8 (for cancer cells, green) as markers, respectively. Blue DAPI staining indicates nucleus. Scale 25 μm. (E) Dot plots show quantification of residual 4T1.2 orthotopic tumors after resection with or without treatment of anti-E-cadherin antibody (left panel), or with or without Torin 1 treatment (right panel). The differences between the treated and control groups are not statistically significant. Error bars SD. (F) Dot plots show qPCR quantitation of 2208L bone lesions with or without Torin 1 treatment. Error bars SD.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Max Wicha and S. Liu for generously providing us with the immortalized human MSC cells, Dr. Robin.L. Anderson for 4T1.2 cells, Baylor Breast Center Pathology Core for technical assistance, and I.S. Kim, H.C. Lo,and Z. Duan for helpful discussion. X. H.-F. Z. is supported by NCI CA151293, CA183878, Breast Cancer Research Foundation, US Department of Defense DAMD W81XWH-13-1-0195, a Pilot Award of CA149196-04, and McNair Medical Institute. H.W. is supported by US Department of Defense DAMD W81XWH-13-1-0296. H. Z. and S.T.C.W. are supported by NIH Grant U54CA149196, John S Dunn Research Foundation and TT & WF Chao Foundation. Studies with the p53 null tumors were supported by NIH grant CA148761 to J.M.R.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Models, mechanisms and clinical evidence for cancer dormancy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:834–846. doi: 10.1038/nrc2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakewell SJ, Nestor P, Prasad S, Tomasson MH, Dowland N, Mehrotra M, Scarborough R, Kanter J, Abe K, Phillips D, et al. Platelet and osteoclast beta3 integrins are critical for bone metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14205–14210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2234372100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Kneissel M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat Med. 2013;19:179–192. doi: 10.1038/nm.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baselga J, Campone M, Piccart M, Burris HA, 3rd, Rugo HS, Sahmoud T, Noguchi S, Gnant M, Pritchard KI, Lebrun F, et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:520–529. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay A, Rudloff J, Ye J, Zumstein-Mecker S, O'Reilly T, Evans DB, Chen S, Lane HA. Dual inhibition of mTOR and estrogen receptor signaling in vitro induces cell death in models of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5319–5328. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs JT, Stayrook KR, Guise TA. TGF-beta in the Bone Microenvironment: Role in Breast Cancer Metastases. Cancer Microenviron. 2011;4:261–281. doi: 10.1007/s12307-011-0075-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, Martin RP, Schipani E, Divieti P, Bringhurst FR, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawthorn TR, Amir E, Broom R, Freedman O, Gianfelice D, Barth D, Wang D, Holen I, Done SJ, Clemons M. Mechanisms and pathways of bone metastasis: challenges and pitfalls of performing molecular research on patient samples. Clinical & experimental metastasis. 2009;26:935–943. doi: 10.1007/s10585-009-9284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman RE, Guise TA, Lipton A, Roodman GD, Berenson JR, Body JJ, Boyce BF, Calvi LM, Hadji P, McCloskey EV, et al. Advancing treatment for metastatic bone cancer: consensus recommendations from the Second Cambridge Conference. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6387–6395. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis C, Shah SP, Chin SF, Turashvili G, Rueda OM, Dunning MJ, Speed D, Lynch AG, Samarajiwa S, Yuan Y, et al. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature. 2012;486:346–352. doi: 10.1038/nature10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diel IJ, Solomayer EF, Costa SD, Gollan C, Goerner R, Wallwiener D, Kaufmann M, Bastert G. Reduction in new metastases in breast cancer with adjuvant clodronate treatment. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:357–363. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808063390601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LK, Mohammad KS, Fournier PG, McKenna CR, Davis HW, Niewolna M, Peng XH, Chirgwin JM, Guise TA. Hypoxia and TGF-beta drive breast cancer bone metastases through parallel signaling pathways in tumor cells and the bone microenvironment. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt BL, Parker BS, van Laar RK, Restall CM, Natoli AL, Tavaria MD, Stanley KL, Sloan EK, Moseley JM, Anderson RL. Genomic analysis of a spontaneous model of breast cancer metastasis to bone reveals a role for the extracellular matrix. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell B, Kang Y. SnapShot: Bone Metastasis. Cell. 2012;151:690–690. e691. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E, Horsley V. Ferreting out stem cells from their niches. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:513–518. doi: 10.1038/ncb0511-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller E, Hurchla MA, Xiang J, Su X, Chen S, Schneider J, Joeng KS, Vidal M, Goldberg L, Deng H, et al. Hedgehog signaling inhibition blocks growth of resistant tumors through effects on tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2012;72:897–907. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschkowitz JI, Zhao W, Zhang M, Usary J, Murrow G, Edwards D, Knezevic J, Greene SB, Darr D, Troester MA, et al. Comparative oncogenomics identifies breast tumors enriched in functional tumor-initiating cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2778–2783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018862108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh AC, Costa M, Zollo O, Davis C, Feldman ME, Testa JR, Meyuhas O, Shokat KM, Ruggero D. Genetic dissection of the oncogenic mTOR pathway reveals druggable addiction to translational control via 4EBP-eIF4E. Cancer cell. 2010;17:249–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Siegel PM, Shu W, Drobnjak M, Kakonen SM, Cordon-Cardo C, Guise TA, Massague J. A multigenic program mediating breast cancer metastasis to bone. Cancer cell. 2003;3:537–549. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennecke H, Yerushalmi R, Woods R, Cheang MC, Voduc D, Speers CH, Nielsen TO, Gelmon K. Metastatic behavior of breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3271–3277. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpal M, Ell BJ, Buffa FM, Ibrahim T, Blanco MA, Celia-Terrassa T, Mercatali L, Khan Z, Goodarzi H, Hua Y, et al. Direct targeting of Sec23a by miR-200s influences cancer cell secretome and promotes metastatic colonization. Nat Med. 2011;17:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nm.2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlow W, Guise TA. Breast cancer metastasis to bone: mechanisms of osteolysis and implications for therapy. Journal of mammary gland biology and neoplasia. 2005;10:169–180. doi: 10.1007/s10911-005-5399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton A, Steger GG, Figueroa J, Alvarado C, Solal-Celigny P, Body JJ, de Boer R, Berardi R, Gascon P, Tonkin KS, et al. Randomized active-controlled phase II study of denosumab efficacy and safety in patients with breast cancer-related bone metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4431–4437. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.8604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]