Abstract

Objective

Individuals with serious mental illnesses are more likely to have substance-related problems than those without mental health problems. They also face more difficult recovery trajectories as they cope with dual disorders. Nevertheless, little is known about individuals’ perspectives regarding their dual recovery experiences.

Methods

This qualitative analysis was conducted as part of an exploratory mixed-methods study of mental health recovery. Members of Kaiser Permanente Northwest (a group-model, not-for-profit, integrated health plan) who had serious mental illness diagnoses were interviewed four times over two years about factors affecting their mental health recovery. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded with inductively-derived codes. Themes were identified by reviewing text coded “alcohol or other drugs.”

Results

Participants (N = 177) were diagnosed with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder (n = 75, 42%), bipolar I/II disorder (n = 84, 48%), or affective psychosis (n = 18, 10%). At baseline, 63% (n = 112) spontaneously described addressing substance use as part of their mental health recovery. When asked at follow-up, 97% (n = 171) provided codeable answers about substances and mental health. We identified differing pathways to recovery, including through formal treatment, self-help groups or peer support, “natural” recovery (without the help of others), and continued but controlled use of alcohol. We found three overarching themes in participants’ experiences of recovering from serious mental illnesses and substance-related problems: Learning about the effects of alcohol and drugs provided motivation and a foundation for sobriety; achieving sobriety helped people to initiate their mental health recovery processes; and achieving and maintaining sobriety built self-efficacy, self-confidence, improved functioning and a sense of personal growth. Non-judgmental support from clinicians adopting chronic disease approaches also facilitated recovery.

Conclusions

Irrespective of how people achieved sobriety, quitting or severely limiting use of substances was important to initiating and continuing mental health recovery processes. Substance abuse treatment approaches that are flexible, reduce barriers to engagement, support learning about effects of substances on mental health and quality of life, and adopt a chronic disease model of addiction may increase engagement and success. Peer-based support like Alcoholics or Narcotics Anonymous can be helpful for people with serious mental illnesses, particularly when programs accept use of mental health medications.

Keywords: dual recovery, serious mental illnesses, substance use, schizophrenia, biopolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, affective psychosis

Individuals with serious mental illnesses are much more likely to have substance-related problems than individuals without mental health problems (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005; Regier et al., 1990; Wilk et al., 2006). They also face substantially more difficult recovery trajectories because they must learn to cope with two different types of serious and life-changing conditions.

Recovery from serious mental illnesses often includes self-assessing strengths and weaknesses, evaluating progress and setbacks, and learning and developing the agency and capacity, over time, to manage the challenges of living with serious mental health problems (Green, 2004; Davidson & Strauss, 1992; Drake & Whitley, 2014). These challenges include coping with: (1) ongoing and episodic symptoms, (2) disruptions in normal human development, life trajectories, and social relationships, (3) the often stigmatizing reactions of others, and (4) the experiences of receiving treatment, whether positive or negative. Recovery from addiction includes similar processes of self-assessment, and of coming to recognize that use of substances can cause a variety of problems in areas including health, family, and work or school (Hanninen & Koski-Jannes, 1999). In the case of individuals with serious mental illnesses, recovery may also include coming to understand the ways in which mental health problems and use of substances interact.

For these reasons, integrated dual diagnosis treatment programs tailored to address the complex intersection of mental illness and substance use are likely to be more effective than separate programs (Mueser, Bellack, & Blanchard, 1992; Drake et al., 2001; Drake, O'Neal, & Wallach, 2008), and have come to be considered the standard for evidence-based treatment for individuals with co-occurring mental illnesses and substance use disorders (Ziedonis et al., 2005; Dixon et al., 2010). Taking an organizational perspective, however, Horsfall and colleagues (Horsfall, Cleary, Hunt, & Walter, 2009) argue that regardless of whether services are integrated or parallel, it is essential that they be well-coordinated, multidisciplinary team-based, allow 24-hour access to specialist-trained personnel, include a variety of program formats and long-term follow-up. Taking the perspective of service users, Davidson and colleagues argue that the formal organization of services is of less practical importance than individuals’ experiences of recovery, and that processes of recovery from substance-related problems have commonalities with processes of recovery among individuals with serious mental health diagnoses (Davidson & White, 2007; Davidson et al., 2008). Recent evidence showing benefit from traditional addiction treatment among individuals with serious mental illnesses (Boden & Moos, 2013), and a comprehensive review showing no particular advantages of different treatment approaches other than motivational interviewing (Cleary, Hunt, Matheson, Siegfried, & Walter, 2008; Cleary, Hunt, Matheson, & Walter, 2009), suggest that the greatest effects on treatment outcomes may come from a focus on increasing personal control, confidence, a commitment to change, hope for the future, a positive redefinition of self, and a place in the community (Davidson et al., 2008). Indeed, Xie and colleagues (Xie, Drake, McHugo, Xie, & Mohandas, 2010) found that, in addition to altering their patterns of substance use, people who experienced 6-month remissions followed by substance use recovery developed a number of resources and tools to sustain stable remission: They learned to manage their illnesses, experienced improvements in psychiatric symptoms, became employed or worked more hours, and experienced greater life satisfaction.

Much remains to be known, however, about the perspectives and experiences of individuals who are recovering from both serious mental illnesses and substance-related problems, or about how those perspectives and experiences are affected by their treatment experiences. For example, Henwood and colleagues (Henwood, Padgett, Smith, & Tiderington, 2012) found that formerly homeless individuals with mental health and substance problems had varying recovery trajectories, and that substance use recovery was rarely attributed to formal treatment. Hipolito and colleagues (Hipolito, Carpenter-Song, & Whitley, 2011) reported that dual recovery required coming to terms with and gaining knowledge about psychiatric and substance use problems, staying focused in the present, and moving through a process of transformation and growth while maintaining hope.

In this paper, we use interview data from a mixed-methods longitudinal study of recovery from serious mental illnesses to examine participants’ substance use, substance-related problems, and substance-related recovery experiences. We explore their views about how substance use affected their mental health recovery trajectories and use these experiences to suggest clinical and systems-based approaches to increasing engagement and improving mental health and addiction recovery outcomes. Such information should be valuable to clinicians and administrators working to develop patient-centered services that meet the differing needs of service users with co-occurring disorders.

METHODS

Data reported here were derived from a larger exploratory mixed methods study of factors affecting recovery from serious mental illnesses. Sociodemographic and other descriptive data were collected from health plan records and paper and pencil questionnaires; qualitative results were derived from four in-depth interviews conducted with each participant over two years (2 at baseline, 1 each at 1- and 2-year follow-ups).

Setting and Recruitment

The Study of Transitions and Recovery Strategies (STARS) sample consisted of members of Kaiser Permanente Northwest, a group-model not-for-profit integrated health plan that provides comprehensive medical and behavioral health care to nearly 500,000 members. Using health plan diagnostic records, we identified 1,827 potential participants who were 16 years of age or older, had at least 12 months of health plan membership and had received an inclusion diagnosis at least twice in the prior year. Potential participants were selected randomly within strata defined by gender and diagnosis (schizophrenia spectrum versus mood disorders). Individuals with diagnoses of organic brain disorders, dementia, or moderate to severe mental retardation were excluded, as were participants whose mental health providers felt they would be unable to participate at the time of recruitment. Recruitment letters were signed by the principal investigator and the individual’s mental health clinician or primary care provider. We exceeded recruitment goals after sending letters to 418 of the 1,827 potential participants. Of the 418 sent letters, we reached 350 and enrolled 184, though the final sample equaled 177 because three did not complete both baseline interviews and 4 were determined to have been identified based on diagnostic coding errors. The distributions for age and sex of the enrolled sample, within diagnosis, did not differ from the study-eligible population of health plan members.

After a complete discussion of what study participation would involve and their rights as research participants, all study participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved and monitored by the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Research Subjects Protection Office and the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects.

Interviews and Data Management

Interviews were conducted between February 2004 and August 2006 at the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research or the participant’s home. Master’s and doctoral level mental health interviewers led the interviews, each of which lasted, on average, about 60 minutes. Interview recordings were transcribed and coded with an inductively-derived set of coding categories, developed after reading subsets of transcripts at each interview wave. Codes were defined, tested, and adapted to ensure they adequately captured interview content. Once codes were finalized, transcripts were coded by study investigators and study interviewers, using Atlas.ti software (Friese, 2011). We met weekly during the coding process to review each coder’s codes for the same assigned section of text, discussed and resolved discrepancies, and clarified code definitions as needed. We also completed check coding to assess and improve coder agreement. Check coding of 10% of baseline interviews produced 80.9% agreement; agreement increased to 87.3% at the first follow-up interview and to 88.8% at the second follow-up interview. To increase rigor (Boyatzis, 1998), we involved researchers and clinicians with different academic backgrounds (sociology, psychology, psychiatry, systems science, public health, anthropology, statistics) in the design and analysis process, received feedback from a consumer advisory panel after each wave of results and analyses, and considered rival explanations throughout data analysis. We also compared our findings to those of other researchers and to recovery theories in the addiction and mental health literatures.

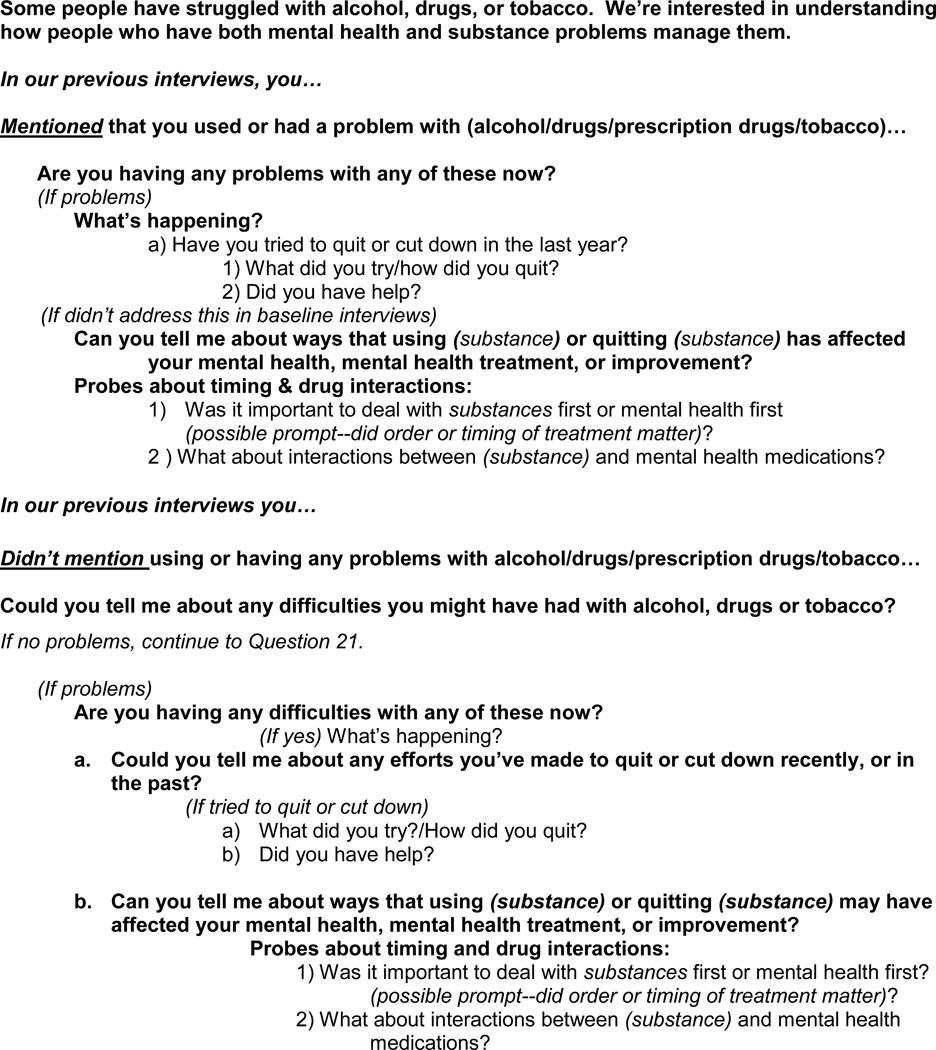

We did not systematically inquire about substance use at baseline, though 63% (n = 112) of participants spontaneously volunteered information about drugs and alcohol in response to interview questions about general mental health recovery. At the first follow-up interview (at 12 months) we asked the questions included in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Questions from interview guide addressing use of alcohol and other drugs and mental health recovery.

All information addressing alcohol or drug use, whether in response to these questions or in response to other parts of the interviews, was coded as related to “alcohol or drug use” and analyzed by study staff to identify and describe themes in participants’ responses. Thus themes derived from this analysis were emergent and not a result of systematic query (e.g., not everyone was asked about every theme, so no denominator was available). For this reason, we do not present data on the prevalence of each theme, because to do so would systematically underrepresent endorsement of the themes and lead to misinterpretations of the results. A majority of participants’ transcripts included codeable information about alcohol or drug use and mental health, however.

At baseline, 63% (n = 112) of participants spontaneously offered answers that addressed alcohol or other drugs as part of their recovery process. At follow-up, when asked directly about substance use, 97% (n = 171) provided codeable answers. Thus, nearly all participants provided information useable for analyses. Quotes presented here were chosen because they were deemed to be particularly illuminating, or because they clearly illustrated identified themes.

RESULTS

Study participants (N = 177) had diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (n = 75, 42%), bipolar I or II disorder (n = 84, 48%), or affective psychosis (n = 18, 10%). Fifty-two percent of participants were women (n = 92), and age ranged from 16–84 years (M = 48.8 years, SD = 14.8). The majority were white (n = 167, 94%), 54% (n = 93, overall N = 173) were married or living with a partner, and 40% (n = 69, N = 173) reported being employed. In a self-report questionnaire, nearly half (n = 77, N = 170 45% of the sample reported using alcohol or street drugs to help manage their mental health symptoms in the past, while 8% (n = 14, N = 170) reported doing so currently. About one-third (n = 59, N = 173) reported drinking alcohol in the past month, 15% (n = 26, N = 171) reported that drug or alcohol use had been a problem in the past four weeks, and 29% (n = 51, N = 173) were current smokers. We identified three overarching themes regarding the ways that use and abuse of substances affected recovery from serious mental illnesses and a variety of pathways to sobriety. Detailed descriptions of these themes and pathways follow.

Learning about the Effects of Alcohol and Drug Use

Participants described learning, sometimes over long periods, about how substances affected them individually, and about the need for information about how alcohol and other drugs interact with mental health medications and mental health conditions more generally. Though these learning processes came about in different ways, the outcomes were common, leading to increased motivation to change substance use and providing an underlying foundation to support sobriety. For example, some participants had bad experiences that led to the realization that they had to quit using drugs:

The last time I did amphetamines, I was so scared because I was kind of like hallucinating and I got really freaked out…I realized that I was a bad person and that I needed to change.

Others had clinicians who warned them about the effects of substances on their mental health, and the risks of using substances with mental health medications:

Participant: I don’t drink at all.

Interviewer: You resolved that on your own? Did you get treatment?

Participant: No… The doctor said, “You’ve got the Irish curse, you’re not to drink, you’re not to drink with the medications. Just forget that part of it.” And I did, for my own good.

Some learned about the effects of substances through formal treatment programs:

Interviewer: Did you ever receive any treatment for substance use?

Participant: I went to a place where you go in and you learn about alcohol and drugs… They don’t lock you up. I think it lasted about a month and you would go in for classes…It taught me a lot about what it was doing to my body…I had no idea.

Learning and coming to a clear understanding of the effects of substances could take years:

I guess it took place when I first started going to AA, but I didn't get sober for 5 years, I didn't get a year of sobriety for 6 years after I started going to meetings, but I knew something was working because my quality of life had improved after a year of sobriety, and I recognized that so I kept doing the same things.

Another participant told how her psychiatrist continued to work with her over a period of years until she was ready to address her drug use:

Participant: …I got hooked up with (DOCTOR) when I was 22. I was in touch with him during this whole time. He was a person. He was monitoring my medications. I wouldn't take my medications because I would not remember because I would be really out of it, but he was talking to me, and he was the person who helped me get into drug and alcohol treatment…because he saw what was happening. I didn't see him that often but I would come in and he would talk to me about it, and eventually I did go through drug and alcohol treatment here at Kaiser.

Interviewer: Was it something he said?

Participant: It was things he said over a period of time. I remember going in one day saying I've cut way back, I just use a little cocaine, he said, "Any cocaine is too much," he was helping me, because I was in this whole drug mentality, and I would go in and…he talked a lot about how the drugs and alcohol were making my condition worse and how…people tend to self-medicate when they have that condition, and I was a person that was going to suffer a lot more with drugs and alcohol than other people who maybe didn't have a condition. He talked a lot about that. He was just there, and I would go in and I could just talk to him.

Recovery Pathways

At the first follow-up interview, we specifically asked participants about their perspectives on the order and timing of dual diagnosis treatment (“Was it important to deal with substances first or mental health first?”); what emerged in participants’ responses were a wide range of pathways to overcoming addictions. Some were focused on formal treatment, others reported “natural” self-directed recovery, and a few reported controlled use of substances. Self-help groups were crucial supports for some participants. In general, coming to grips with the fact that alcohol and drug use made mental health problems worse led to important turning points for many participants:

Interviewer: What about turning points in your life, times when your life changed or you started to look at things differently?

Participant: The major thing was the end of my drinking…

Formal treatment

A number of participants attended formal treatment programs, and found those programs to be helpful and educational, providing the support, knowledge and skills to become and remain clean and sober:

…it's really hard to get off, especially the cocaine, but when I walked in it was me and 15 men…but actually then one woman came in so there was 2 women and a lot of men, but the drug counselor was really good…It was getting an education about the facts about the drugs, and then having groups and talking about it, I finally was able to do it…I haven't used cocaine since July of [year]. I went about 2 years and 4 months and then I used alcohol so I had to start my clean date over again…I had to totally get rid of those friends. I had a boyfriend for 7 years, I had to get rid of him, I had to start over. I couldn't see those people because they're all still doing it.

This participant appreciated the treatment program’s support of family involvement in her recovery process:

Interviewer: Tell me about that experience [30–day residential stay]… What made it positive?

Participant: The steps. The recovery, due to treatment I had a very good relationship with my girls [daughters], we went to treatment dances all the time, we just had a ball. They went right through it with me, after I got out of residential I stayed in recovery…

Other participants encountered program-related problems that arose as a result of the effects of mental health medications on their ability to attend treatment sessions:

… the amount of frustration in going through [substance-related] recovery, going through group therapy and treatment that way, at the same time attempting to readdress and figure out what's going on with your mental health issue…I went on the Effexor, and I was missing appointments because I couldn't drive, those drugs were just kicking my ass, then I got a phone call, told I couldn't miss any more or I'd be kicked out, because recovery has to come first. What good is recovery if I'm going to die in a car crash on the way over there?

With relapse common among people with addictions (McLellan, Lewis, O'Brien, & Kleber, 2000) and dual disorders (Dixon, 1999; Drake, Wallach, & McGovern, 2005), strict treatment program rules presented additional barriers to recovery among people with dual disorders:

I was in this program for dual diagnosis with alcohol and drug problems, and mental health problems…but I got kicked out of there because I was still using methamphetamines. I was taking my meds too…they did a UA and the doctor said he didn’t see any meds in my system, just the drugs. About a year after that I got the dirty UA in the [military], and another year after that I was still drinking, so it was a few years after I started taking my meds that I really got serious about it, knew I had to abstain totally in order for them to work correctly.

In contrast, another participant was given a chance after a relapse and was successful in achieving sobriety:

…it was a 5-week program and I relapsed in the middle of it, in treatment, and there was another guy…he had relapsed and they just kicked him out right then… I knew I had relapsed and I was petrified. I knew that if I got kicked out of there I didn't know where I was going to go, and I didn't want to go back to where I had been, so I told the whole group and the drug counselor…I knew he was going to kick me out, and he didn't. He let me stay for 2 more weeks, I stayed there for 7 weeks, and I asked him later why you kicked this other guy out, why didn't you kick me out, he said, "Because I knew you really wanted it, that you were working at it and you really wanted to make it happen." If that drug counselor had kicked me out…I don't know what would have happened to me, but they really hung in there with me and I got my sobriety date after that.

“Natural” recovery

Participants described various methods of managing their substance use, including quitting or reducing on their own, without help:

Interviewer: How long did you drink?

Participant: …25 years, I thought it had already damaged my liver, my doctor had said liver is moderately enlarged, so I thought this can't go on…So I had tried just cold turkey like the AA people, giving it up, one drink is too many and a thousand is not enough. So I said let me do it my own way, so I chose Monday, no alcohol on Monday. I had tea and juice, maybe I got some ice cream. No alcohol. No problem, several weeks of that, I knew on Monday I wouldn't be drinking any beer, then Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday, so pretty soon, I was only drinking Saturday and Sunday. Pretty soon I was only drinking Saturday, and eventually I thought, I don't need this. I got to the point I completely re-educated myself to, I could drink occasionally when family would get together for a Sunday morning brunch with champagne, I could have the champagne, I had no need for any more later in the day, or visit one of the boys and I'd have 1 or 2 beers, and that would be all, no more. I had learned to drink, I had educated myself to drink socially, which the AA people say can't be done, once a drinker always a drinker, so you see, it can be done.

Continued controlled use

A few participants reported light alcohol consumption without negative consequences, despite warnings from clinicians:

Participant: [My clinician] discourages me from drinking because I’m on medication. I understand that and I respect that.

Interviewer: Is that something that you would like to do, do you think?

Participant: No, I like getting off work and having a glass of wine. I don’t get drunk. I’m not falling down.

Interviewer: You just like having a drink.

Participant: Yeah, I just like having a glass of wine when I get off of work.

Interviewer: Do you feel like you have a sense of control over your drinking?

Participant: Yes, I do.

Self-help groups and peer support

Others mentioned self-help groups as essential components of managing or overcoming addictions, despite difficulties faced by people with mental illnesses in some abstinence-oriented groups. These participants’ stories illustrate the ways in which self-help groups provide wide-ranging support for recovery and self-development:

Participant: …once a term, I see my psychiatrist, but the biggest thing is AA, cause when I need therapy that’s where I go.

Interviewer: How often are you going there?

Participant: About once a day…early on…I was sitting in the meeting and…they said, (SELF) would you like to read?…I said I guess I will, and I was sweating bullets because I didn't read well. I never read a book or anything, so I started reading and this old guy is sitting next to me, I'm really having a lot of trouble, and (NAME), he says, "What's wrong?" I said, "It's those damn words moving off the end of the page." I said, "I don't see how you keep them straight." He said, “…nobody cares in here, none of us are that good of readers, it doesn't matter, relax," and when I started relaxing and looking that nobody was staring at me and going to hit me, everything started to straighten up. Yeah, it's totally changed my life…

Self-help groups also provided opportunities for community integration through social support and by helping to build social confidence:

Interviewer: What was it about the mental health programs or AA or other groups that helped you?

Participant: The fellowship. The fact that you are with another warm human being either talking by them or sitting by them or just sharing the same space as another human being. A lot of the mentally ill hole up in a room by themselves and just wall people out. The fellowship with another human being is important, whether or not that human being does much associating. At least that human being tolerates your company and you eat meals with that human being. That is helpful.

Self-help groups also provided spiritual sustenance for people who found it lacking in formal treatment agencies or services.

Interviewer: Was the mental health program helpful to you at all?

Participant: I don't know. Too humanistic. I started going to AA meetings, and stuff, with my issues about alcohol…Everything that helped me was…more of a religious nature.

Another participant noted:

I relapsed a lot, 30 days to a year then I'd go back to smoking pot. When I finally accepted my concept of a higher power, God, whatever, not religion but spirituality, I was able to get over the hump, got a year of sobriety and ever since then I haven't relapsed.

For those who decided to enter drug treatment or self-help programs like Alcoholics or Narcotics Anonymous, conflicts with program requirements could lead to setbacks. For example, some self-help programs were unwilling to allow the use of mental health medications:

It's like, oh my God, I'm in a full blown panic attack and I'm not sure right now how to get out of it. Then the old timers in AA were adamant about “you don't take medication because that's drugs.”

Sobriety Helped to Initiate Mental Health Recovery Processes

Once participants took control of their substance use, they began to recover from their mental health problems. For some participants, substances had masked their mental health symptoms or kept them from accepting their mental health problems, making them unable to recognize such problems until addictions had been addressed. For example:

Participant: Yeah, I had to kick the crutches away so I could look at the problem, because…the problem was hiding. It was still there, but I could not see it because I was elsewhere mentally. I was experiencing the problem, but a person could be experiencing crossing the street but that doesn't mean they know where the hell they're going.

This participant provided a similar comment:

…when I had the alcohol problem, I didn't know I had a mental health problem too…the alcohol was covering it up.

For others, the clarity of mind that came from overcoming substance problems provided the ability to address mental health problems:

I think not being on drugs and alcohol makes my mind a lot clearer so I can work on [my mental health].

Sobriety Built Self-efficacy and Self-confidence, and Improved Functioning

Overcoming substance problems, including with the help of others, gave many participants a sense of agency, helped to build self-confidence and increased self-efficacy. These successes fostered a strong sense of personal growth among some participants, improved functioning, and helped people with goal attainment. Participants identified these successes as important turning points in their recovery.

…my first goals were to get off using narcotics, which was probably around the ninth grade, so three years ago…I set that goal and I had the determination from my girlfriend to get that accomplished. I got that, and that didn’t take more than four months…[it] was a big self-esteem boost. That was the first time that I had put my mind to actually accomplishing something.

Once sobriety was achieved, each clean and sober day built confidence and a sense that a better life was possible:

…the cycle continues till you come to the point where you say okay, I hate feeling like that, I hate looking at myself like that…I'm not going to do that no more…You start feeling strong about yourself, stay clean for a week or two and it be one day at a time, but still you know, not being in that environment, you could do okay, regardless of what kind of drug it is.

In addition, for some participants, overcoming addictions led to strong feelings of having successfully grown personally:

When I finally found out that I could do without the drinking, that was a big change for me…When I wasn’t drinking at all anymore, I felt like I had really grown.

For some participants, abstinence led to significant improvements in functioning and ability to achieve personal goals. This included individuals who were receiving treatment for mental health problems while continuing to struggle with addictions:

Interviewer: …do you think it was more important for you to get mental health treatment first, or to get clean first, or some combination?

Participant: I wish it could have happened at the same time… Because even though I was struggling with mental health issues, I didn't really see an improvement in my life until I got clean and sober.

Interviewer: So you got the mental health treatment first?

Participant: Yeah, but…my quality of life was not that good. I was a [dishwasher] and I really was going nowhere, and then I quit using and drinking, and I turned around and got an MSW.

Finally, in addition to providing a sense of personal achievement, quitting substances helped to reduce exacerbations of mental health symptoms, and to improve social relationships for some participants:

Interviewer: Could you tell me about ways that quitting has affected your mental health?

Participant: Night and day, if people just wouldn’t use, try to self-medicate and use street drugs, they’d be so much better off…when you’re using drugs it aggravates it [mental health problems], and it makes it hard for you and everybody around you.

DISCUSSION

Irrespective of the pathways people took to sobriety, participants reported that quitting, or severely limiting, use of alcohol and substances was essential to initiating or continuing the process of mental health recovery. Pathways to sobriety were diverse, and included formal treatment programs, self-help groups like Alcoholics or Narcotics Anonymous, quitting substances with or without help, and reducing and maintaining alcohol consumption at light-to-moderate levels.

Despite the long-term successes of many in our sample, participants’ efforts to quit or control substance use took significant time. Individuals had to learn about the effects of substance use on their mental health and quality of life, and about the interactions of substances with their mental health medications. In addition, quitting or limiting use took substantial effort and, not surprisingly, was often characterized by repeated relapses and multiple attempts to quit. Consistent with treatment philosophies that define addictions as chronic illnesses (McLellan et al., 2000), when programs and clinicians accepted relapses and continued to work with people, they were grateful for this understanding and acceptance, and reported that these approaches helped them achieve sobriety. When achieved, sobriety led to turning points in peoples’ lives, while the process of learning to take control over substances increased agency, self-efficacy and self-confidence, and produced greater personal insight. These changes led to a sense of personal growth, helped to improve functioning and goal achievement and spurred recovery processes.

Our work is consistent with that of other researchers who have found both highly individualized recovery trajectories and common processes, including turning points from which recovery eventuated (Henwood et al., 2012; Davidson & White, 2007). Our results extend these findings as well, indicating that formal treatment programs that give people with serious mental illnesses more leeway regarding medications, and recognize and accept that these people experience non-substance related functional deficits and medication side-effects that affect their ability to engage and attend treatment, may be more effective in promoting dual recovery. It should also be reiterated that many people recover outside of formal treatment settings, as some of our participants described.

Limitations

Limitations of this study are related primarily to the representativeness of our sample. Our participants were predominantly Caucasian and all were insured members of an integrated health plan. Therefore, their experiences may not reflect those of individuals in ethno-racial minority groups, those disengaged from healthcare, or those receiving care in community treatment settings, though many had received care in community settings prior to becoming insured, and people were in various stages of recovery from both mental health and substance-related problems. Another limitation is that the themes we identified were emergent, thus we have no denominator to assess prevalence of these perspectives or experiences in our sample. Future research could address this limitation.

Conclusions

Substance abuse treatment approaches that are flexible and reduce barriers to engagement among people with serious mental illnesses, support learning about the effects of substances on mental health and quality of life, and that adopt a chronic disease model of addiction are likely to be more effective at helping people to quit substances. Peer support programs such as Alcoholics or Narcotics Anonymous can be particularly helpful for people with serious mental illnesses if programs are accepting of needed mental health medications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank interviewers Sue Leung, David Castleton, and Alison Firemark for their help developing the qualitative coding scheme, and for coding interviews.

FUNDING

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (Recoveries from Severe Mental Illness, R01 MH062321).

All authors have received grant support from the National Institutes of Health and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Green has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Purdue Pharma, the Kaiser Permanente Center for Safety and Effectiveness Research, and the Kaiser Permanente Community Benefit Initiative. Dr. Green has also provided research consultation for the Industry PMR, a consortium of nine companies who are working together to conduct FDA-required post-marketing studies that assess known risks related to extended-release, long-acting opioid analgesics. The Industry PMR consortium is comprised of Pfizer, Purdue Pharma, Roxane Laboratories, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Mallinckrodt, Actavis, Endo Pharmaceuticals, Rhodes Pharmaceuticals, and Zogenix. Dr. Yarborough has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Kaiser Permanente Center for Safety and Effectiveness Research, Purdue Pharma, and the Kaiser Permanente Community Benefit Initiative. Mr. Yarborough has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health, Purdue Pharma, and the Kaiser Permanente Community Benefit Initiative. Ms. Janoff has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the Kaiser Permanente Center for Safety and Effectiveness Research, and Purdue Pharma.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Polen reports no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Contributor Information

Carla A. Green, Email: carla.a.green@kpchr.org, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest.

Micah T. Yarborough, Email: micah.yarborough@kpchr.org, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest.

Michael R. Polen, Email: michaelpolen@centurytel.net, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest.

Shannon L. Janoff, Email: shannon.l.janoff@kpchr.org, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest.

Bobbi Jo H. Yarborough, Email: bobbijo.h.yarborough@kpchr.org, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest.

REFERENCES

- Boden MT, Moos R. Predictors of substance use disorder treatment outcomes among patients with psychotic disorders. Schizophrenia Research. 2013;146(1–3):28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary M, Hunt GE, Matheson S, Siegfried N, Walter G. Psychosocial treatment programs for people with both severe mental illness and substance misuse. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34(2):226–228. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary M, Hunt GE, Matheson S, Walter G. Psychosocial treatments for people with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance misuse: Systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65(2):238–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Andres-Hyman R, Bedregal L, Tondora J, Frey J, Kirk TA. From "Double Trouble" to "Dual Recovery": Integrating models of recovery in addiction and mental health. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2008;4(3):273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Strauss JS. Sense of self in recovery from severe mental illness. The British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1992;65(Pt 2):131–145. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1992.tb01693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, White W. The concept of recovery as an organizing principle for integrating mental health and addiction services. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2007;34(2):109–120. doi: 10.1007/s11414-007-9053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L. Dual diagnosis of substance abuse in schizophrenia: Prevalence and impact on outcomes. Schizophrenia Research. 1999;35(Suppl):S93–S100. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00161-3. doi: doi.org/10.1016/S0920-9964(98)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS, Bennett M, Dickinson D, Goldberg RW, Kreyenbuhl J. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36(1):48–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Essock SM, Shaner A, Carey KB, Minkoff K, Kola L, Rickards L. Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(4):469–476. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, O'Neal EL, Wallach MA. A systematic review of psychosocial research on psychosocial interventions for people with co-occurring severe mental and substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34(1):123–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Wallach MA, McGovern MP. Future directions in preventing relapse to substance abuse among clients with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(10):1297–1302. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.10.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Whitley R. Recovery and severe mental illness: Description and analysis. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;59(5):236–242. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese S. User's manual for ATLAS.ti (6.0) Berlin: ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.atlasti.com/uploads/media/atlasti_v6_manual.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Green CA. Fostering recovery from life-transforming mental health disorders: A synthesis and model. Social Theory & Health. 2004;2(4):293–314. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.sth.8700036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanninen V, Koski-Jannes A. Narratives of recovery from addictive behaviours. Addiction. 1999;94(12):1837–1848. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941218379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henwood BF, Padgett DK, Smith BT, Tiderington E. Substance abuse recovery after experiencing homelessness and mental illness: Case studies of change over time. Joutnal of Dual Diagnosis. 2012;8(3):238–246. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2012.697448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipolito MM, Carpenter-Song E, Whitley R. Meanings of recovery from the perspective of people with dual diagnosis. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2011;7(3):141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Horsfall J, Cleary M, Hunt GE, Walter G. Psychosocial treatments for people with co-occurring severe mental illnesses and substance use disorders (dual diagnosis): A review of empirical evidence. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2009;17(1):24–34. doi: 10.1080/10673220902724599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(13):1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Bellack AS, Blanchard JJ. Comorbidity of schizophrenia and substance abuse: Implications for treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60(6):845–856. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.6.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264(19):2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk JE, West JC, Narrow WE, Marcus S, Rubio-Stipec M, Rae DS, Pincus HA, Regier DA. Comorbidity patterns in routine psychiatric practice: Is there evidence of underdetection and underdiagnosis? Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2006;47(4):258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Xie L, Mohandas A. The 10-year course of remission, abstinence, and recovery in dual diagnosis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2010;39(2):132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziedonis DM, Smelson D, Rosenthal RN, Batki SL, Green AI, Henry RJ, Weiss RD. Improving the care of individuals with schizophrenia and substance use disorders: Consensus recommendations. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2005;11(5):315–339. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200509000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]