Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is a commensal of the human nose and skin. Human skin fatty acids, in particular cis-6-hexadecenoic acid (C-6-H), have high antistaphylococcal activity and can inhibit virulence determinant production. Here, we show that sub-MIC levels of C-6-H result in induction of increased resistance. The mechanism(s) of C-6-H activity was investigated by combined transcriptome and proteome analyses. Proteome analysis demonstrated a pleiotropic effect of C-6-H on virulence determinant production. In response to C-6-H, transcriptomics revealed altered expression of over 500 genes, involved in many aspects of virulence and cellular physiology. The expression of toxins (hla, hlb, hlgBC) was reduced, whereas that of host defence evasion components (cap, sspAB, katA) was increased. In particular, members of the SaeRS regulon had highly reduced expression, and the use of specific mutants revealed that the effect on toxin production is likely mediated via SaeRS.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00203-014-1048-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: S. aureus, Skin fatty acid, C-6-H, Resistance

Introduction

The Gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus is able to survive as a commensal organism in the anterior nares and on human skin. A third of the human population are nasal carriers and two-thirds are intermittent carriers, forming a large reservoir for potential infection (Peacock et al. 2001). As a pathogen, S. aureus is highly adaptable, with an alarming spread of antibiotic resistance. This limits the range of effective therapies able to combat this organism. S. aureus is able to cause a wide range of diseases, from minor skin infections to severe systemic disease (such as bacteraemia, septic arthritis and endocarditis). Also, in the hospital environment, S. aureus is responsible for many infections associated with surgical wounds and catheters. The ability to inhabit so many niches with such a range of infectious sequelae is due to a large repertoire of virulence determinants.

The human body has many innate defence mechanisms to prevent infection by invading microbes. Physical barriers (human skin and mucosa) prevent pathogens from ingress. The human skin is composed of tightly bound epithelial cells and covered by a highly cross-linked layer of keratin and is therefore normally impenetrable to bacteria (Proksch et al. 2008). Additionally, the skin produces antimicrobial peptides as well as skin fatty acids which are crucial for host defence (Ong et al. 2002; Niyousaba and Ogawa 2005). Several fatty acids have been isolated from human skin, which have strong antimicrobial activity (Miller et al. 1988; Wille and Kydonieus 2003). The antibacterial activity of unsaturated fatty acids has been well known for many years (Kabara et al. 1972; Knapp and Melly 1986; Shin et al. 2007), the most effective antistaphylococcal skin fatty acid being cis-6-hexadecanoic acid (C-6-H, sapienic acid, C16:1Δ6) (Takigawa et al. 2005; Wille and Kydonieus 2003). As well as being antibacterial, C-6-H also has the ability to inhibit virulence determinant production and the induction of antibiotic resistance mechanisms (Clarke et al. 2007; Projan et al. 1994; Schlievert et al. 1992; Takigawa et al. 2005; Kenny et al. 2009). In fact, in murine models of S. aureus infection, C-6-H has shown to be an effective treatment. Thus, it is important to understand how C-6-H mediates its effects and the response of S. aureus to such assault. A surface protein, IsdA, has been shown to be involved in resistance of S. aureus to C-6-H by rendering the cells more hydrophilic (Clarke et al. 2007). Also, wall teichoic acids are required to prevent susceptibility to C-6-H (Kohler et al. 2009).

In order to define bacterial components important in resistance to C-6-H and how its effect on virulence determinant expression is mediated, a global study of gene expression and protein profile analysis in response to C-6-H was carried out.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1 and were grown in iron-limited tryptic soy broth (TSB−Fe) (Oxoid), Chelex-100 (Sigma Aldrich), with the addition of 20 µM 2,2′-dipyridyl (Baldassarri et al. 2001). Antibiotics used were erythromycin (5 µg/ml), lincomycin (25 µg/ml) or tetracycline (5 µg/ml) where appropriate. Cultures were grown at 37 °C and inoculated with an overnight culture to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05 into TSB−Fe, followed by incubation with agitation at 37 °C. Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring the OD600.

Table 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype/markers | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| SH1000 | Functional rsbU + derivative of 8325-4 | Horsburgh et al. (2001) |

| Newman | High level of clumping factor | Duthie and Lorent (1952) |

| JLA371 | SH1000 hla∷lacZ hla + (EryR) | Horsburgh et al. (2001) |

| SJF1293 | saeS∷Tn551 (SH1000) (EryR) | Needham et al. (2004) |

| SJF1295 | saeR∷Tn551 (SH1000) (EryR) | Needham et al. (2004) |

| Reynolds CP5 | Serotype 5 prototype strain (CP5) | Karakawa and Vann (1982) |

| Reynolds (CP−) | Capsule-negative mutant of Reynolds (CP5) (EryR) | Watts et al. (2005) |

| KC046 | mrgA∷lacZ (pAZ106) (EryR) | Cosgrove (unpublished) |

Bacterial killing assays

Bacteria were grown to an OD600 of approximately 0.6 in TSB−Fe. Cells from 10 ml of culture were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 5,000×g and 4 °C. The cell pellet was washed twice in sterile dH2O by resuspension and centrifugation as above. OD600 was measured, and cell suspension was adjusted to OD600 of 1.0. Cells were incubated at 37 °C with cis-6-hexadecanoic acid (C-6-H; Matreya) and cfu determined at intervals by plating onto TSB−Fe agar. For C-6-H pre-exposure experiments, bacteria were grown to an OD600 of 0.5 in TSB−Fe and 8 µg/ml C-6-H was added, prior to continued incubation, with shaking, for 2 h by 37 °C. Cells were then harvested, washed and exposed to C-6-H in the killing assay, as above.

Transcriptional analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cultures (OD600 of 0.5), prior to, 10 and 60 min after the addition of 10 µg/ml C-6-H. “RNAprotect Bacteria Reagent” (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) was added to 8 ml culture and incubated for 5 min, and cells were harvested by centrifugation (5,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C) and resuspended in 1 ml RLT buffer (Qiagen) including 10 µg/ml β-mercaptoethanol. Cells were lysed using a Fast Prep shaker (BIO 101 Savant, Haarlem, The Netherlands) for 3× 40 s at a speed of 6.5 units. RNA was isolated using an “RNeasy Mini Kit 250” from QIAGEN. RNA quantity was measured using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer and the quality checked by analysis with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Reverse transcription and fluorescent labelling reactions were performed using 10 µg total RNA, random hexamer primers mix (Invitrogen), SuperScript III™ Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and incubation for 1 h at 50 °C. The cDNA was labelled with Cy3- and Cy5-dyed d’CTPs (Amersham) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Scienion, Berlin, Germany).

RNA obtained from three independent biological experiments was utilised, and a dye switch experiment was performed to minimise errors based on the differential dye bleaching or incorporation absorption of Cy3 and Cy5 during the RT reaction. The microarray hybridization and washing of the slides were carried out as recommended by the manufacturer (Scienion, Berlin). Microarray hybridization was at 49 °C for 48 h. The microarrays (Scienion) contained the full genome of S. aureus N315. Each slide contained PCR products of 2,334 genes in duplicate copies of each open reading frame (ORF) and multiple controls. Slides were scanned using a Genepix 4000B laser scanner (Axon Instruments Inc., Union City, CA, USA), and the individual signal intensity was analysed using Acuity 4.0 software, according to the manufacture’s instructions. Briefly, data were normalised to the mean ratio of means of all features, and all experiments were normalised to each other. Standard deviations and mean values of gene expression ratios based on the two spot replicates on each microarray and three different hybridisation experiments were calculated. Significant changes in gene expression were identified by a mean ratio <0.5 or >2.0 and a p value <0.05.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

RNA was isolated as described for the transcriptional analysis. Two microgram of RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA as above. Master mixes were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using oligonucleotides specific for target genes listed in Table 2. SYBR Green (SensiMixPlus SYBR, Quantace, London, UK) was used as a fluorescent nucleic acid dye. RT-qPCR was performed in a Mx3000P Real-Time PCR System (Stratagene), and the following temperature profile was used for amplification. The initial denaturation was at 95 °C for 10 min, and templates were amplified by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s and 54 °C for 1 min. A final step, 1 min at 95 °C, 30 s at 54 °C and 30 s 95 °C was used. A dissociation curve was generated to ensure amplification of a single product and absence of primer dimmers (Nolan et al. 2006). Three reference genes (gyrB, yneR and ysxC) were used which showed no significant change in expression on microarrays at all times and under all conditions. For calculation of the relative levels of gene expression, only gyrB was used as the endogenous reference gene.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used for RT-PCR analysis

| Oligonucleotides | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| gyrB_QF | ATCACAGCATTTGGTACAGG |

| gyrB_QR | CGATAGAAGAATGTTAATAACAATGTT |

| ysxC_QF | GCAGTAAAAGAAGAACAATATCC |

| ysxC_QR | GGGTTGCTGTGATGTACG |

| asp23_QF | AAACAACAAGAACAAAATCAAGAG |

| asp23_QR | ACCACCTTCAACAGATACACC |

| hprT_QF | TGTAAGGAATTGGGAGCAC |

| hprT_QR | ACTTCACCAGTTGACTCAG |

| sceD_QF | TCGCATCATCATTAGCAGTAG |

| sceD_QR | GTGATAAGTAAACCCTTCATAGTC |

| saeS_QF | GTATTGGCATTATACCAGAACTAC |

| saeS_QR | GCGAGTTCATTAGCTATATATAAGC |

| saeR_QF | CCAAGGGAACTCGTTTTACG |

| saeR_QR | CATAGGGACTTCGTGACCAT |

| lytS_QF | AAAGTTGAAAGAAGTGCATACTAAAGAAG |

| lytS_QR | TGTACCGACGATAGAACCATG |

| lytR_QF | ATTAGGAGCTAAGATTCAAAAGATG |

| lytR_QR | TTGACTGCTTGTTCAATACG |

| lrgA_QF | GCATCAAAACCAGCACACTT |

| lrgA_QR | TGATGCAGGCATAGGAATTG |

| lrgB_QF | TATTTGGTGTGGCCTTCCTC |

| lrgB_QR | AAACAGATTGTTGCCGGTTC |

| PhoP_QF | TCGGGTATTAGGTTTAGAATTAGG |

| PhoP_QR | GGTAATATCATCGTCAATCTCTTC |

| PhoR_QF | AATCCGTCCCATTCAAGAAGTTAC |

| PhoR_QR | AGGCGTCGTGCTAAATCATTG |

| butA_QF | CGTCTGAAGGTATTACTGTGAATG |

| butA_QR | TGAGAAACTCTGCCCAAAGC |

| agrB_QF | TCTGACGGTACTTATGTGAC |

| agrB_QR | CCAGTGCTATTAGTTCCACTG |

| lytM_QF | GCTATACATTCGTAGATGCTCAAG |

| lytM_QR | CTCGCTGTGTAGTCATTGTTATC |

| hla_QF | ATGATAGAGATTCTTGGAACCC |

| hla_QR | AATAACTGTAGCGAAGTCTGG |

| katA_QF | ACGAGATCCTAGAACAAATATGAG |

| katA_QR | GTATGTGTGAGAACCGAACC |

| clfA_QF | AATGATTCAAGTAGCGTTAGTG |

| clfA_QR | TTCGTTGTCGTAGTAGTAGC |

| sarA_QF | GAGTTGTTATCAATGGTCACTTATGC |

| sarA_QR | CAGTTCTTTCATCATGCTCATTACG |

| cidA_QF | CTACTACTACAACTAGGAATCATC |

| cidA_QR | TTTAGCGTAATTTCGGAAGC |

| mrgA_QF | AGTACAATCTAACATACCCACAATTTCTTG |

| mrgA_QR | GAGTGCTAATTCAGTTACGACTTTCTTG |

| rsbU_QF | GAAATCGTTAAAGGCTTTGGTTATAG |

| rsbU_QR | GCTCATTGTGCCATCGTTATG |

| spa_QF | GCAAACCATGCAGATGCTAA |

| spa_QR | AACGCTGCACCTAAGGCTAA |

Preparation of protein extracts

For the preparation of extracellular protein extracts, cytoplasmic protein extracts, ionically bound proteins and membrane proteins, bacteria were grown in TSB−Fe (1 l) to exponential phase (OD600 of 1.0) and stationary phase (16 h).

Cells were harvested by centrifugation (9,000×g for 10 min), and extracellular proteins from the supernatant were precipitated using 100 % w/v fresh TCA (10 % w/v final volume) and incubated on ice for 30 min. Proteins were harvested by centrifugation (9,000×g for 5 min), and the pellet was washed 5 times with 100 % v/v acetone and air-dried for 1.5 h. The precipitated proteins were then washed twice with 100 % v/v ethanol, once with 70 % v/v ethanol and finally with 100 % v/v ethanol, prior to air-drying the pellet overnight at room temperature (RT). Proteins were dissolved in urea solution (8 M urea, 2 M thiourea), with incubation at RT for 30 min. In order to remove insoluble proteins, the suspension was centrifuged for 5 min at 20,000×g. The protein concentration was determined for each sample and adjusted to 200 µg protein.

For the isolation of the cytoplasmic proteins, harvested cells were broken by FastPrep as above and the suspension then centrifuged at 20,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The ensuing supernatant was centrifuged at 150,000×g for 2 h at 4 °C, using an ultracentrifuge (Optima™ LE-80 K, Beckman, USA). The supernatant was then centrifuged as above, and the cytoplasmic proteins were then precipitated using 10 % w/v TCA and prepared as described above (for supernatant proteins).

Analytical and preparative 2D-PAGE

Two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) was performed by using the immobilized pH gradient (IPG) technique as described previously (Bernhardt et al. 1999). First, protein samples were separated on linear IPG strips (ImmobilineTM DryStrips, GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). For extracellular and ionically bound protein samples, strips in the pH range 3–10 were used, and for cytoplasmic protein samples, the pH range 4–7 was used. 2D gels were loaded with 200 µg protein extract, and the resulting gels were fixed with 50 % v/v ethanol and 3 % v/v acetic acid, for 30 min. Afterwards, 2D gels were stained with SYPRO®-Ruby and fixed with 10 % v/v methanol and 7 % v/v acetic acid. The stained gels were finally scanned using a Typhoon 9400 Variable Mode Imager (Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany). For protein identification by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS), SYPRO stained protein spots were cut from gels using a spot cutter (Proteome Work™) with a picker head of 2 mm and transferred into 96-well microtiter plates. The proteins were digested with trypsin, and subsequent spotting of peptide solutions onto MALDI targets was performed automatically by using an Ettan Spot Handling Workstation (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) using a standard protocol as previously described (Eymann et al. 2004). Actual analyses of spotted peptide solutions were performed as previously described (Wolf et al. 2008).

Results and discussion

Induced resistance of S. aureus to C-6-H

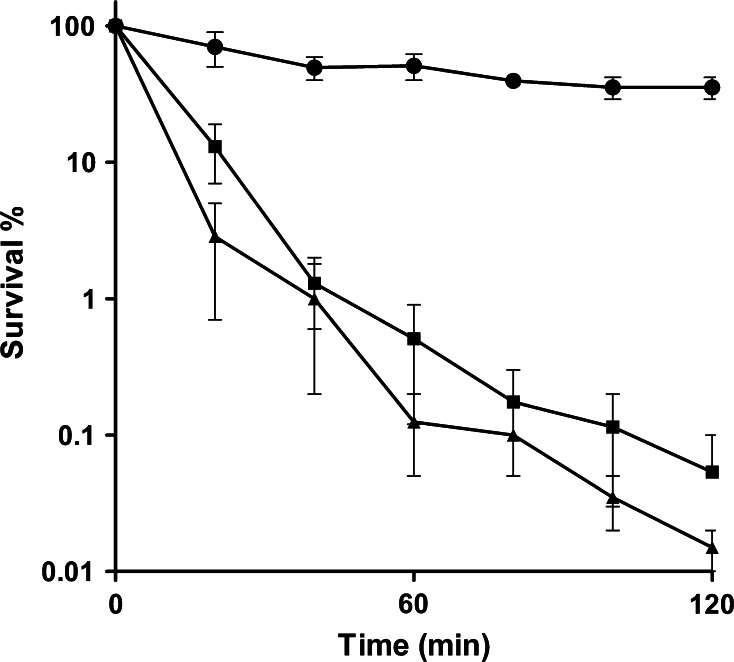

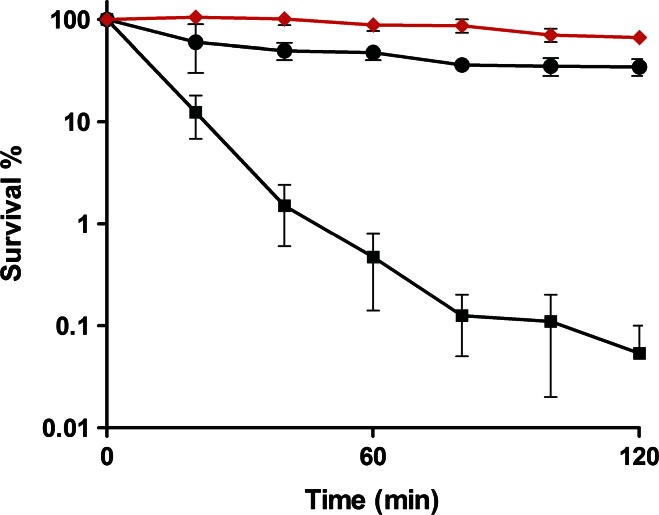

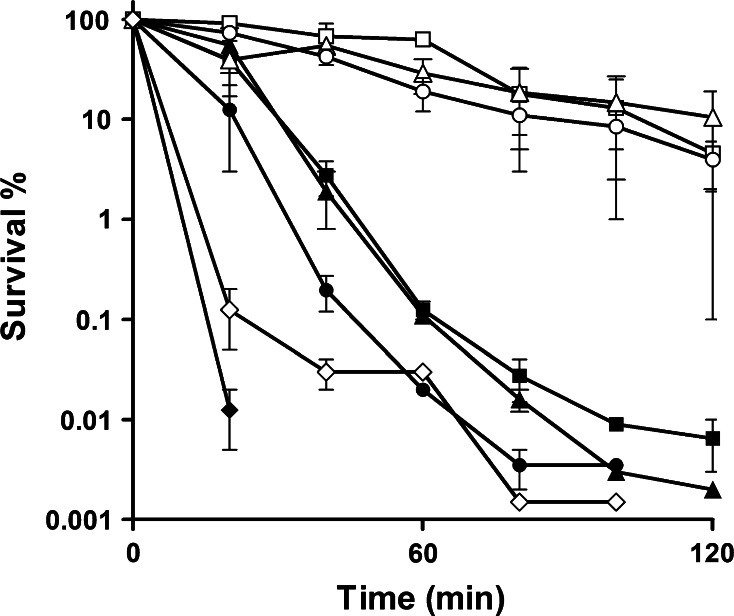

To determine whether S. aureus responds to C-6-H, the effect of preincubation with a sub-MIC level of the fatty acid on resistance was determined. Firstly, to confirm the bactericidal effect of C-6-H, SH1000 was grown in TSB−Fe to early exponential phase and challenged with 10 or 20 µg/ml C-6-H over 2 h. We observed a rapid decrease in survival rate. At t = 40 min, cells treated with 10 µg/ml showed only 1.3 % survival and cells treated with 20 µg/ml C-6-H showed a survival rate of 1 % (Fig. 1). The untreated control showed over 55 % survival after 120 min. Conversely, those cells previously exposed to subgrowth inhibitory level of C-6-H were much more resistant than naïve cells. After 1 h, 99 % of naïve cells were dead compared with only 12 % of those pretreated (Fig. 2). This indicates that S. aureus responds to C-6-H treatment by the induction of a resistance mechanism. In order to find out the level of C-6-H-induced resistance, additional assays were performed. C-6-H pretreated cells were incubated with 30, 40, 50 and 60 µg/ml C-6-H in the killing assay (Fig. 3). Pretreated cells showed resistance up to 50 µg/ml C-6-H challenge. Challenge with 50 µg/ml C-6-H killed over 99.9 % of naïve cells after 60 min of incubation, whereas pretreated cells were 80 % killed after this time. However, once 60 µg/ml C-6-H was used the induced resistance threshold was reached. There is no difference in sensitivity to C-6-H between the preincubated and non-preincubated cells (Fig. 3). Thus, a resistance mechanism is induced in response to C-6-H. S. aureus is an extremely adaptable organism able to respond to environmental assault. Chan and Foster (1998) reported an increase in resistance to acid stress (pH 2), when the cells were pre-exposed to non-lethal pH 4. How cells become more resistant to C-6-H is unknown, but no alteration in solvent partitioning by the cells was seen (data not shown). Cells grown in iron-limited conditions (as here) express isdA, which renders them hydrophilic (Clarke et al. 2007). IsdA is a major surface protein and has multiple roles as an adhesin, as a resistance determinant against human innate defences (including C-6-H), and is required for S. aureus survival on human skin (Clarke et al. 2004, 2007; Clarke and Foster 2008; Clarke 2010).

Fig. 1.

Bactericidal effect of C-6-H on strain SH1000 wt. SH1000 was grown in TSB−Fe until OD600 0.5–0.6. Cells were harvested, washed with dH2O and challenged with 0 (filled circle), 10 (filled square) or 20 (filled triangle) µg/ml C-6-H over 2 h. Samples were taken, and cfu was determined over time. Samples were plated in triplicate, and each experiment was repeated twice. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean

Fig. 2.

Induced C-6-H resistance of SH1000 by pre-incubation with a sub-MIC of C-6-H. SH1000 was grown in TSB−Fe with or without 10 µg/ml C-6-H until OD600 0.5–0.6. Cells were harvested, washed with dH2O and challenged with 0 (filled circle), 10 (filled square) or 10 with preincubation (filled diamond) µg/ml C-6-H over 2 h. Samples were taken, and cfu was determined over time. Samples were plated in triplicate, and each experiment was repeated twice. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean

Fig. 3.

Bactericidal effect of C-6-H on cells preincubated with a sub-MIC concentration. SH1000 was grown in TSB−Fe with (open symbols) or without (filled symbols) 8 µg/ml C-6-H until OD600 0.5–0.6, as described in chapter 2. Cells were harvested, washed with dH2O and challenged with 30 (open square, filled square), 40 (open triangle, filled triangle), 50 (open circle, filled circle) or 60 (open diamond, filled diamond) µg/ml C-6-H. Samples were taken, and cfu was determined over time. Samples were plated in triplicate, and each experiment was repeated twice. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean

Effect of C-6-H on global gene transcription

In order to determine mechanisms involved in response to C-6-H, including induction of resistance and inhibition of virulence determinant production, transcriptional profiling was carried out. The expression patterns from exponential phase culture of S. aureus SH1000 with and without 10 µg/ml C-6-H were compared. Under these conditions, C-6-H has no significant effect on growth rate or yield. Culture samples for analysis were taken 10 min and 60 min after C-6-H addition. After 10-min incubation with C-6-H, 290 genes were decreased and 293 genes were increased in expression level (Table S1). Besides many genes of unknown function and those encoding hypothetical proteins, there were also many genes whose expression was altered by C-6-H which encode ABC transporters, bacterial secretion systems, cell wall metabolism components, DNA replication and repair pathways as well as central metabolic and pathogenicity determinants. After 60-min incubation with C-6-H, 57 genes were reduced and 92 genes were increased in expression level compared with the untreated control (Table S1). These include genes encoding proteins involved in ABC transporter systems, metabolism of coenzymes and prosthetic groups, amino acid synthesis, stress response and many genes involved in virulence of S. aureus.

Effects of C-6-H on purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis

The greatest decrease in expression after 10-min C-6-H incubation was shown by genes encoding proteins involved in purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis (Table S1). In particular, pyrR, pyrP, pyrB, pyrC, pyrAA, pyrAB, pyrF and pyrE of the de novo pyrimidine metabolism were significantly down-regulated (spot vol. ratio 0.09 ± 0.04) in the presence of C-6-H compared with the control. This whole operon is regulated by pyrR and strongly depends on the presence of pyrimidine nucleotides (Turner et al. 1994; Paulus et al. 1982). Synthesis of pyrimidine is crucial for the cells to divide and therefore cell survival (Turnbough and Switzer 2008). The regulator pyrR showed a decrease in expression (spot vol. ratio of 0.06) in the presence of C-6-H (10-min incubation). Interestingly, after 60-min incubation with C-6-H, the operon pyrR-E (SA1041–SA1048) was highly increased in expression (Table S1). The regulator pyrR is increased in expression (spot vol. ratio 19.6), and genes pyrP, pyrB, pyrC and pyrAB were even more (spot vol. ratio 25 ± 5) up-regulated in expression, suggesting that the rapid response (10 min) of S. aureus to C-6-H may alter the intracellular pyrimidine pool, thus requiring increased expression of the genes after the initial adaptation period. Interestingly, the response to C-6-H may be specific as Kenny et al. (2009) reported no effect of linoleic or oleic acid on expression of genes involved in pyrimidine biosynthesis. How C-6-H and other fatty acids effect bacteria and differential responses alludes to fatty acid-specific mechanisms.

Genes that are involved in purine metabolism such as xprT (xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase), guaA (GMP synthase), guaB (inositol-monophosphate dehydrogenase) and relA(rsh) (GTP pyrophosphokinase) also showed a strong decrease in expression in the presence of C-6-H after 10-min incubation (spot vol. ratio 0.3 ± 0.2) (Table S1). After 60-min C-6-H incubation, the expression of xprT, guaA, guaB but not relA was still decreased. Interestingly, RelA as well as enzymes of the purine biosynthetic pathway has been described to be involved in resistance to lysostaphin (Gründling et al. 2006). Further, RelA (Rsh) may be important in the response to C-6-H as it effects the expression of a number of genes, including cap (via CodY) (Geiger et al. 2010; Pohl et al. 2009; Srivatsan and Wang 2008; Wolz et al. 2010).

Effects of C-6-H on cellular transport systems

The microarray data demonstrated that many genes encoding for ABC transporters were effected in expression in the presence of C-6-H. Two genes, cbiO (Cobalt import ATP-binding protein Cibo1) and cibO2 (Cobalt import ATP-binding protein CibO2), which are part of the cobalt transporter, are decreased in expression. After 10-min incubation with C-6-H, microarray data showed a spot vol. ratio of 0.42 and 0.49. Cobalt is an essential cofactor for several enzymes and other components such as vitamin B12 and must be imported into the cell (Kobayashi and Shimizu 1999). Surprisingly, other genes involved in cobalt transport such as cbiQ (transmembrane component) and cbiN (small membrane-bound component) were not affected in expression by C-6-H. After 60-min incubation with C-6-H, the cbiO genes showed no change in expression compared with the control (Table S1).

The expression of three genes, potA, potB and potC, from the potABCD operon were down-regulated after 10-min C-6-H incubation with a spot vol. ratio of 0.28 ± 0.05. After 60-min incubation with C-6-H, the expression of genes from the potABCD operon showed no change compared with the control. The operon encodes an ABC transporter that transports polyamines such as putrescine and spermidine across the membrane. Polyamines play an important role in cell proliferation and differentiation, as shown in E. coli (Kashiwagi et al. 1993).

Interestingly, the genes encoding for a putative monovalent cation/H+ antiporter were increased in expression in the presence of C-6-H (spot vol. ratio of 2.1 ± 0.1). SA0578 (putative antiporter subunit A), SA0579 (putative antiporter subunit B), SA0580 (putative antiporter subunit C), SA0581 (putative antiporter subunit D), SA0583 (putative antiporter subunit E) and SA0584 (putative antiporter subunit F) may be part of a Na+/H+ antiporter which is involved in resistance to high concentrations of K+, Li+ and Na+ ions. Antiporters play an important role in circulating Na+ and H+ across the cytoplasmic membrane (Padan and Schuldiner 1994) and are also important for the internal pH maintenance. Recently, we reported the bactericidal mechanisms of C-6-H at different concentrations (Cartron et al. 2014). C-6-H has multiple effects on the cell membrane including loss of the ability to maintain intracellular pH.

Compared with the genes that were affected after 10-min incubation, a completely different set was affected (positively as well as negatively) in expression after incubation with C-6-H for 60 min. The array data revealed that the genes sirA, proP, fhuA, glpF and SA2339 were increased in expression by C-6-H incubation. Interestingly, the gene SA2339 is highly up-regulated (spot vol. ratio over 11) in expression in the presence of C-6-H. SA2339 is, according to the database (NCBI), a hypothetical protein which shows similarities to an antibiotic transport-associated protein. The sirA gene (staphylococcal iron regulator) encodes for a lipoprotein, and the microarray data revealed a spot vol. ratio of 2.9, only after 60-min C-6-H incubation. The sirA gene is part of the operon sirABC. Heinrichs et al. (1999) reported that SirA acts as a membrane-associated siderophore-binding protein. The operon is iron regulated, and transcription is controlled by the Fur protein (Heinrichs et al. 1999). Interestingly, the regulatory gene fur showed a down-regulation (spot vol. ratio 0.48) after 10-min incubation with C-6-H. The fur gene encodes for the ferric uptake regulator which controls cellular iron homoeostasis (Horsburgh et al. 2001).

Furthermore, the gene fhuA (ferrichrome transport ATP-binding protein) was increased in expression after 60-min C-6-H incubation (spot vol. ratio 2.4). The fhuA gene is part of the fhu system which encodes for a ferric hydroxamate uptake system and therefore involved in iron acquisition from hydroxamate siderophore (Sebulsky et al. 2000). Interestingly, none of the other genes that belong to the fhu system were affected in expression by C-6-H. The fhuD2 gene (spot vol. ratio 3.9) showed an increase in expression after 60-min C-6-H treatment. Sebulsky et al. (2003) reported that fhuD2 encodes an iron (III)-siderophore-binding protein. After binding a siderophore, the FhuD2–siderophore complex will be recognised by the Fhu system. Iron is one of the most important nutrients for S. aureus and is required for various key metabolic processes. Its acquisition is vital for survival. The sirABC operon as well as the fhu genes is crucial components in the iron acquisition process.

The gene proP, which encodes for a proline/betaine transporter homologue (MacMillan et al. 1999), was increased (spot vol. ratio 2.4) in expression in the presence of C-6-H at 60 min only (Table S1). This transporter is important in balancing osmotic differences between S. aureus and its environment. The proP gene is part of the VraSR regulon, which includes 13 genes in total and is involved in regulation of the cell wall biosynthesis pathway (Kuroda et al. 2003).

Effects of C-6-H on the cell envelope and cell wall synthesis

The expression of many genes involved in cell envelope biogenesis, including lytM, dltABD, cidA, pbp2 and pbp4, was altered in response to C-6-H treatment. The peptidoglycan hydrolase LytM (autolysin) plays a role in cell wall turnover as well as cell division (Ramadurai et al. 1999). After 10-min incubation with C-6-H, the expression of lytM was decreased (spot vol. ratio 0.48) in expression, whereas after 60-min incubation no change in expression was observed. LytM hydrolyses peptidoglycan, and it has been proposed that it might play a role in the lysis of cells initiated by cell wall-acting antibiotics (Kusser and Ishiguro 1988), suggesting that C-6-H may induce lysis.

Genes of the dltABCD operon, which is important for d-alanylation of wall teichoic acids (WTA) as well as lipoteichoic acids (LTA), showed a strong decrease in expression in the presence of C-6-H after 10-min treatment. After 60-min C-6-H incubation, no change in expression of the dltABCD was observed. The dltA gene (spot vol. ratio 0.15) encodes a d-Alanyl carrier protein ligase and activates d-alanine using ATP. Also, dltB, a predicted transmembrane protein, and dltD, a membrane protein (Neuhaus and Baddiley 2003), showed a spot vol. ratio of 0.25 ± 0.02. Surprisingly, dltC expression showed no effect of C-6-H in the microarray data. Koprivnjak et al. (2006) reported that the dltABCD operon is highly repressed by a rising concentration of monovalent and divalent (Mg2+) cations. This group also mentioned that the transcriptional regulation may be partly due to the ArlSR two-component system. (Koprivnjak et al. 2006)

Weidenmaier et al. (2005) reported the role of the dltABCD operon in mediating resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMP). DltABCD is able to modify negatively charged cell envelope components with positively charged amino acids, to enhance the net positive surface charge of S. aureus leading to CAMP resistance (Peschel 2002). The down-regulation (due to C-6-H) of dltABD expression may affect surface charge. Kohler et al. (2009) showed that wall teichoic acids, which play an important role in S. aureus surface charge, are crucial for protection of S. aureus against human skin fatty acids such as C-6-H. However, the treatment with C-6-H showed a strong decrease in expression of the dltABCD operon within the first few minutes but then recovers.

Penicillin-binding proteins 2 and 4 had altered expression (spot vol. ratios of 2.04 and 0.46, respectively) after 10-min incubation with C-6-H. PBP2 is involved in cell wall metabolism and methicillin resistance (Giesbrecht et al. 1998), and PBP4 is mainly involved in secondary cross-linking of the peptidoglycan layer (Henze and Berger-Bachi 1996), further suggesting that the cell wall of S. aureus is involved in protection against fatty acids.

The regulator lytSR, which encodes for a sensor histidine kinase (LytS) and a response regulator (LytR), was reduced (spot vol. ratio 0.38 ± 0.04) after 10-min C-6-H incubation (Table S1). LytSR is a sensor–regulator system with both positive and negative regulatory effects on murein hydrolase activity and autolysis (Brunskill and Bayles 1996). It is proposed that LytSR is able to sense a decrease in membrane potential and initiates the transcription of lrgAB (Patton et al. 2006; Bayles 2007). The lrgAB genes are involved in the regulation of murein hydrolase activity and may play a role in autolysin regulation (Groicher et al. 2000; Bayles 2003). Further studies reported that the cidA gene encodes for a holing-like membrane protein that is an effector of murein hydrolase activity and cell lysis, whereas lrgA encodes an antiholin that is an inhibitor of CidA (Groicher et al. 2000; Rice et al. 2003). Interestingly, the array data showed that the expression of lrgAB is highly increased after 10-min incubation with C-6-H (spot vol. ratios of 89 and 20, for lrgA and lrgB, respectively) (Table S1) even if its regulatory activator (lytSR) is inhibited in expression by C-6-H. LrgA and LrgB are involved in regulation of peptidoglycan hydrolase activity by reducing extracellular activity (Groicher et al. 2000; Bayles 2003). Bayles (2007) suggested that LrgAB together with their antagonist proteins CidAB was involved in the control of bacterial death and lysis during biofilm formation. Interestingly, the expression of cidA was decreased after 10-min C-6-H incubation (spot vol. ratio over 4). The cidA gene is in an operon with cidB. The cidB gene showed no change in expression levels in the presence of C-6-H, but cidA was decreased in expression and cidC was increased in its expression, respectively.

Further, Rice et al. (2003) showed that a lytSR mutation leads to an increase in autolysis rate and a decrease in lrgAB expression. These data were confirmed when Sharma-Kuinkel et al. (2009) reported that a mutation in the lytS gene showed a drastic decrease in the expression of lrgAB operon. Interestingly, in this study, the expression of lytSR showed a decrease in its transcription in the presence of C-6-H and the expression of the lrgAB operon was highly increased in its expression, suggesting that there might be an additional so far unknown regulatory system involved in lrgAB control.

We have observed that the bactericidal activity of C-6-H occurs via a variety of mechanisms, including loss of proton motive force (PMF) (Cartron et al. 2014), which may lead to an increase in lytSR expression.

The biological role of the lrg and cid operons has been suggested to be in the control of cell death and lysis during biofilm formation, as well as release of genomic DNA to promote intracellular adhesion in biofilm stability (Bayles 2007). The increased lrgAB expression and decreased expression of cidA may be due to cell wall stress and is a response that may prevent cell death due to metabolic perturbation. In a separate study, Kenny et al. (2009) observed a decrease of lrgA expression in response to linoleic acid, which demonstrates distinct responses to specific unsaturated long-chain fatty acids by S. aureus.

Capsule biosynthesis genes (cap) showed a significant increase in expression (spot vol. ratio of 2.4–7) (Table S1). The capsule is involved in the pathogenicity of S. aureus by preventing phagocytosis and killing by macrophages (O’Riordan and Lee 2004). Thus, it was possible that the capsule may represent a C-6-H resistance mechanism. Strain SH1000 is not highly encapsulated, and so the role of capsule was determined using strain Reynolds. Killing assays using strain Reynolds and corresponding cap strains did not show any significant differences in C-6-H susceptibility (data not shown). Kenny et al. (2009) also observed an increase in cap gene expression in response to linoleic acid by strain MRSA252. As the capsule has an antiphagocytic effect, it may be that host-associated stresses (such as C-6-H) lead to its induction as a general response.

Effects of C-6-H on the expression of virulence determinants

Clarke et al. (2007) have previously reported a decrease in toxin production in response to C-6-H. The microarray data revealed altered expression of many genes involved in pathogenicity. After incubation with C-6-H, virulence-associated genes such as nuc, hla, hlb, rsbU, sarZ, sarA, clfA and two-component regulator saeRS were effected in expression (Table S1).

The thermonuclease (nuc) is an extracellular protein that degrades double- and single-stranded DNA and RNA. After 10-min incubation with C-6-H, the expression of nuc was decreased (spot vol. ratio 0.3), but after 60-min treatment with C-6-H the expression of nuc was increased (spot vol. ratio 2.4). The degradation of extracellular DNA plays an important role in host immune evasion to escape from neutrophils extracellular traps (NETs) (Berends et al. 2010).

Besides, the two-component regulator saeRS that encodes for a histidine kinase and a response regulator was affected by -6-H (Giraudo et al. 1999). After 10-min incubation with C-6-H, the expression of saeRS genes was decreased (spot vol. ratio 0.4). Novick and Jiang (2003) reported two additional ORFs in the SaeRS system, saeP and saeQ, which are likely to be important for the function of the operon (Adhikari and Novick 2008; Geiger et al. 2008). The saeP gene, but not saeQ, was decreased in expression (spot vol. ratio 0.28) after incubation with C-6-H for 10 min.

Previous reports have shown that SaeRS activates the expression of α-haemolysin (hla), β-haemolysin (hlb), fibronectin-binding protein (fnbA and fnbB), protein A (spa), coagulase (coa), thermonuclease (nuc), extracellular adherence protein Eap, IgG-binding protein (sbi) and extracellular matrix-binding protein Emp (Giraudo et al. 1994, 1997; Goerke et al. 2001, 2005; Harraghy et al. 2005). Furthermore, it represses the expression of V8 serine protease (sspA) and capsular polysaccharide (type 5) (cap5). As many of those virulence determinants (e.g. hla, hlb, fnbA, nuc) were decreased in expression due to C-6-H, this may be due to the activity of SaeRS (Table S1).

There was differential expression of surface proteins in response to C-6-H. Clumping factor A (clfA), a fibrinogen-binding protein, showed a high increase in expression after 10-min C-6-H incubation (spot vol. ratio 6.5). The ClfA protein plays an important role in the adhesion to host cells (McDevitt et al. 1994) and is responsible for clumping in host blood plasma (McDevitt et al. 1997). Kenny et al. (2009) reported a similar observation, where clfA expression is up-regulated. Interestingly, the surface protein-encoding genes fnbA and fnbB were decreased in expression by C-6-H. FnbA and B are cell surface-associated proteins which mediate the attachment to host cells (e.g. endothelial cells) and can also act during invasion (Peacock et al. 1999; Xu et al. 2008).

As already reported, the hla and hlb genes were highly decreased in expression after 60-min C-6-H incubation (spot vol. ratio 0.11 ± 0.02). These encode the major toxins α-haemolysin (hla) and β-haemolysin (hlb), which are membrane-damaging molecules, expressed in post-exponential phase, and are important for spreading into new host tissues (Bhakdi and Tranum-Jensen 1991). The effect of C-6-H on hla expression was expected as earlier reports have shown that fatty acids (e.g. glycerol monolaurate (GML) were able to inhibit the expression of virulence determinants in S. aureus (Schlievert et al. 1992; Projan et al. 1994). Clarke et al. (2007) found that C-6-H is able to inhibit the expression of α-haemolysin (hla) and protein A (spa) at the transcriptional level. Since no change in RNAIII expression (agr, the main regulator of virulence factors) has been observed after the exposure to C-6-H or GML, it leads to the suggestion that the effect of C-6-H on the expression of virulence determinants is due to another regulatory system (Projan et al. 1994; Clarke et al. 2007). In contrast, Kenny et al. (2009) observed that the expression of hla and spa was up-regulated after exposure of MRSA252 to linoleic or oleic acid.

The expression of sbi (IgG-binding protein) was negatively affected by C-6-H (spot vol. ratio 0.09 and 0.18 and after 10- and 60-min incubation, respectively). Sbi has an important role in adherence to host cells during the infective process and acts similarly to protein A (Zhang et al. 1998).

Effects of C-6-H on general intracellular processes

Microarray data revealed altered expression of genes involved in carotenoid biosynthesis. The genes crtN (squalene desaturase), crtM (squalene synthase), crtQ (putative glycosyl transferase), crtP (4,4′-diaponeurosporene oxidase) and SA2352 (hypothetical protein) were increased in expression after incubation for 10 min with C-6-H (spot vol. ratio 3.7 ± 1.7). It has been reported that there is a direct correlation between carotenoid production and cell membrane fluidity (Chamberlain et al. 1991; Mishra et al. 2009). The carotenoids insert into the membrane and increase its rigidity, which could lead to its stabilization in response to C-6-H. Previous studies reported that long-chain unsaturated fatty acids could lead to an increase in membrane fluidity (Chamberlain et al. 1991). In the presence of the fatty acid C-6-H, the transcriptome data also showed an increase in expression of genes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis (fabD, fabG, acpP) after 60-min challenge conditions with C-6-H (spot vol. ratio 2.1 ± 0.1) (Table S1). The synthesis of fatty acids is essential for membrane phospholipid formation and stability, suggesting that S. aureus responds to the potential loss of membrane integrity due to C-6-H by increasing the expression of genes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis.

Several genes involved in stress responses were affected in expression by C-6-H incubation. The katA gene encodes catalase and is increased in expression only after 10-min incubation with C-6-H (spot vol. ratio 5). It is important for S. aureus for neutralisation of H2O2, survival and nasal colonisation (Cosgrove et al. 2007).

The microarray data revealed that genes of the Clp family (clpC, clpB and clpL) were increased in expression in the presence of C-6-H (spot vol. ratio 2.4, 3.7 and 13.1, respectively). ClpC is a chaperone with ATPase activity, and together with ClpB, it is highly induced during thermal stress with a function to degrade heat-damaged proteins, as well as an important role in biofilm formation (Becker et al. 2001; Frees et al. 2003). ClpB is required for growth at high temperature (Frees et al. 2003). ClpL is also an ATP-dependent proteinase and is important in the thermotolerance of S. aureus (Frees et al. 2003).

In response to C-6-H, there is an up-regulation of urease (ureA-G) expression (60-min incubation, spot vol. ratio 4 ± 2, Table S1). Urease is involved in hydrolysing urea into NH3 (ammonia) and CO2 (carbon dioxide) as a nitrogen source and acid resistance.

The transcription of dhoM (homoserine dehydrogenase), thrC (threonine synthetase) and thrB (homoserine kinase) was increased after incubation with C-6-H for 10 min (spot vol. ratio 7.5 ± 3.5) and for 60 min (spot vol. ratio 3.1 ± 0.2). All three proteins are important for amino acid synthesis such as serine, glycine or threonine. ThrC catalyses the last reaction of threonine synthesis from asparate.

Real-time PCR (RT-PCR)

The transcriptome data of selected genes were validated using RT-PCR (Table 3), whereas all samples were amplified in triplicate. The focus was on genes involved in virulence and stress response. The RT-PCR analysis showed that hla was 20-fold down-regulated after 60-min incubation with C-6-H. For the genes lrgA, lrgB, katA, sarA, sceD, cidA, lytS and butA, RT-PCR data also confirmed the microarray results, verifying the high impact of C-6-H on the expression of those genes. However, not all qRT-PCR data are in correlation with the effect of C-6-H observed in the microarray data. For spa, hprT, phoP, asp23, lytR and saeRS, no effect on expression due to C-6-H was observed (Table 3). This demonstrates that multiple approaches should be undertaken to verify changes in expression using these types of technologies.

Table 3.

Effect of C-6-H on expression of genes determined by qRT-PCR

| ORF N315 | Gene | Gene product | Fold change RT-PCR | Spot vol ratio (microarray) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 min | 60 min | 10 min | 60 min | |||

| Cell envelope and cell wall | ||||||

| SA0252 | IrgA | Holin-like protein LrgA | 5.00 | 0.27 | 89.97 | 1.00 |

| SA0253 | IrgB | Holin-like protein LrgB | 4.00 | 0.43 | 20.73 | 1.00 |

| SA0265 | IytM | Peptidoglvcan hydrolase | 1.00 | 3.00 | 0.49 | 1.00 |

| SA2329 | cidA | Holin-like protein CidA | 0.23 | 1.00 | 0.22 | 1.00 |

| Virulence factors and regulators | ||||||

| SA0250 | lytS | Two-component sensor histidine kinase | 0.44 | 1.00 | 0.43 | 1.00 |

| SA0251 | lytR | Two-component response regulator | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.35 | 1.00 |

| SA0573 | sarA | Staphylococcal accessory regulator A | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.37 | 1.00 |

| SA0660 | saeS | Histidine protein kinase | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.44 | 1.00 |

| SA0661 | saeR | Response regulator | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.41 | 1.00 |

| SA0742 | clfA | Fibrinogen-binding protein A, clumping factor | 1.00 | 1.00 | 6.54 | 1.00 |

| SA1007 | hla | Alpha-haemolysin | 0.41 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 0.13 |

| SA1842 | agrB | Accessory gene regulator B | 3.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| SA1872 | rsbU | SigmaB regulation protein RsbU | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 1.00 |

| Stress response | ||||||

| SA1170 | katA | Catalase | 3.00 | 1.00 | 5.06 | 1.00 |

| SA1984 | asp23 | Alkaline shock protein 23, ASP23 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 7.52 | 1.00 |

| Butanoate metabolism | ||||||

| SAO122 | butA | Acetoin reductase | 5.00 | 1.00 | 16.89 | 2.72 |

| Transcriptional regulator | ||||||

| SA0641 | mrzA | HTH-type transcriptional regulator MgrA (NorA) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 |

| SA1515 | phoR | Alkaline phosphatase synthesis sensor protein | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| SA1516 | phoP | Alkaline phosphatase synthesis transcriptional regulation | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3.31 | 1.00 |

| Purine and/ or pyrimidine metabolism | ||||||

| SA0468 | hprT | Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase homologue | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.29 | 1.00 |

| Unknown functions and hypothetical proteins | ||||||

| SA1898 | sceD | Hypothetical protein, similar to SceD precursor | 1.00 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 3.18 |

| Housekeeping genes | ||||||

| SA0005 | gyrB | DNA gyrase subunit B | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| SA1186 | Hypothetical protein, homologue toyneS from B. subtilis | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| SA1497 | ysxC | Ribosome biogenesis GTP-binding protein YsxC | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

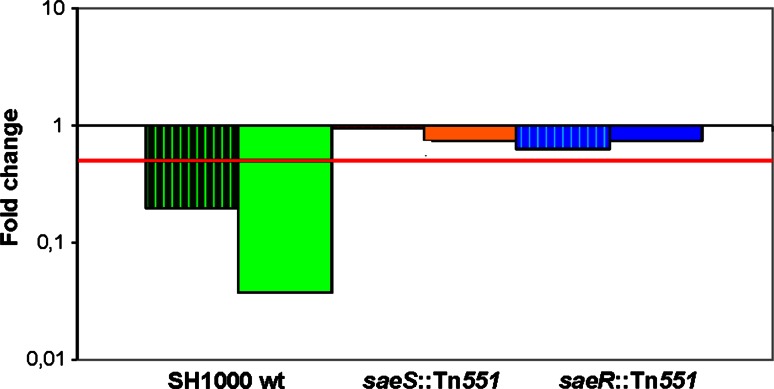

Effect of C-6-H on the S. aureus regulatory system saeRS

The SaeRS response regulator is a key system that controls the expression of virulence determinants in S. aureus and is required for pathogenesis (Giraudo et al. 1994, 1997; Goerke et al. 2001, 2005; Harraghy et al. 2005). Interestingly, saeRS was down-regulated in response to C-6-H as shown by the transcriptome data. Further, many members of its regulon were decreased in expression as well, which suggests that signal transduction by SaeS may be altered as a direct, or indirect, consequence of C-6-H. It has been proposed earlier that fatty acids (such as GML or lauric acid) might affect the cell membrane and therefore disrupt important signalling mechanisms (Schlievert et al. 1992; Holland et al. 1994; Projan et al. 1994; Ruzin and Novick 1998; Vetter and Schlievert 2005). To investigate the role of the SaeRS system in the molecular mechanism of C-6-H, qRT-PCR experiments were performed. The transcription of hla in the presence of a sub-MIC of C-6-H using the saeS (saeS∷Tn551) and saeR (saeR∷Tn551) mutant strains in the SH1000 background was measured. In SH1000 wt, the expression of hla showed a reduction of over fourfold and 20-fold in the presence of C-6-H for 10 and 60 min, respectively. The saeS mutant strain (saeS∷Tn551) revealed no significant change in hla expression in the presence of C-6-H, at 10 or 60 min (Fig. 4). Similar results were observed using the saeR mutant strain (saeR∷Tn551) which also showed no significant difference in hla expression in the presence of C-6-H, suggesting that the two-component system saeRS is implicated in the molecular mechanism of C-6-H. The molecular mechanism of C-6-H in virulence determinant inhibition has not as yet been revealed, but an interference of the signal transduction system in S. aureus is a possible scenario.

Fig. 4.

Effect of C-6-H on hla expression in saeRS mutant strains. S. aureus SH1000 wt, SH1000 saeS∷Tn551 and SH1000 saeR∷Tn551 were grown in TSB−Fe until OD600 0.5. 8 µg/ml C-6-H was added to the cultures, and cells were incubated for 10 (striped bars) or 60 (filled bars) min. Total mRNA was isolated, and an qRT-PCR experiment was performed determining hla expression. Red line shows significant change of at least 0.5-fold. The samples were measured in triplicate, and qRT-PCR experiment was carried out three times

Effect of C-6-H on protein profiles

Transcriptome analysis revealed a pleiotropic effect of C-6-H on gene expression but whether this is translated into significant changes in protein levels and thus activities required a proteomic analysis. The effect of a sub-inhibitory concentration of C-6-H on the extracellular proteins of S. aureus SH1000 was determined using the 2D gel technique (Table 4).

Table 4.

Growth phase associated changes in extracellular protein profile

| ORF N315 | Protein | Gene product | OD 1.0 versus 16 h | Spot ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA0009 | SerS | Seryl-tRNA synthetase | 0.65 | 331 |

| SA0091 | Plc | 1-Phosphatidylinositol phosphodiesterase precurosr | 2.29 | 563 |

| SA0091 | Plc | 1-Phosphatidylinositol phosphodiesterase precurosr | 4.83 | 565 |

| SA0091 | Plc | 1-Phosphatidylinositol phosphodiesterase precurosr | 38.19 | 571 |

| SA0128 | SodM (SodA1) | Superoxide dismutase | 1.60 | 698 |

| SA0131 | Pnp (DeoD1) | Purine nucleoside phosphorylase | 1.11 | 654 |

| SA0131 | Pnp (DeoD1) | Purine nucleoside phosphorylase | 0.06 | 187 |

| SA0162 | AldA | Aldehyde dehydrogenase homologue | 0.27 | 294 |

| SA0182 | Hypothetical protein, similar to indole-3-pyruvate decarboxylas | 1.12 | 280 | |

| SA0265 | LytM | Peptidoglycan hydrolase | 0.15 | 454 |

| SA0265 | LytM | Peptidoglycan hydrolase | 0.13 | 460 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 2.29 | 170 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 3.08 | 171 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 2.84 | 172 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 1.81 | 175 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 4.03 | 177 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 9.64 | 199 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 3.28 | 212 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 1.76 | 224 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 21.07 | 229 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 5.23 | 272 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 1.81 | 282 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 0.83 | 421 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 2.75 | 433 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 0.57 | 439 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 3.00 | 443 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 1.20 | 451 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 1.90 | 176 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 1.17 | 217 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 3.97 | 221 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 0.68 | 238 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 2.99 | 248 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 1.32 | 259 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 1.97 | 293 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 3.40 | 418 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 8.89 | 424 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 5.58 | 435 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 1.15 | 436 |

| SA0366 | AhpC | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C | 3.04 | 712 |

| SA0375 | GuaB | Inositol-monophosphate dehydrogenase | 0.34 | 308 |

| SA0376 | GuaA | GMP synthase | 2.00 | 274 |

| SA0382 | Set6 | Superantigen-like protein | 0.03 | 706 |

| SA0482 | Putative ATP: guanido phosphotransferase SA0482 | 0.76 | 366 | |

| SA0486 | GltX | Glutamyl-tRNA synthetase | 1.21 | 289 |

| SA0486 | GltX | Glutamyl-tRNA synthetase | 0.41 | 302 |

| SA0488 | CysS | Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase | 0.64 | 309 |

| SA0505 | FusA | Elongation factor G | 0.14 | 162 |

| SA0506 | Tuf | Elongation factor Tu | 0.69 | 371 |

| SA0506 | Tuf | Elongation factor Tu | 0.63 | 396 |

| SA0544 | Putative haem peroxidase | 0.21 | 618 | |

| SA0587 | Lipoprotein, streptococcal adhesin PsaA homologue | 1.63 | 561 | |

| SA0587 | Lipoprotein, streptococcal adhesin PsaA homologue | 0.22 | 610 | |

| SA0620 | Secretory antigen SsaA homologue | 0.28 | 626 | |

| SA0674 | Glycerol phosphate lipoteichoic acid synthase | 0.87 | 336 | |

| SA0674 | Glycerol phosphate lipoteichoic acid synthase | 0.53 | 343 | |

| SA0674 | Glycerol phosphate lipoteichoic acid synthase | 1.15 | 344 | |

| SA0674 | Glycerol phosphate lipoteichoic acid synthase | 0.70 | 346 | |

| SA0674 | Glycerol phosphate lipoteichoic acid synthase | 0.50 | 353 | |

| SA0686 | NrdE | Ribonucleotide-diphosphate reductase subunit alpha | 0.51 | 189 |

| SA0719 | TrxB | Thioredoxin reductase | 1.82 | 508 |

| SA0727 | Gap | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 0.54 | 447 |

| SA0728 | Pgk | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 0.57 | 409 |

| SA0731 | Eno | Phosphopyruvate hydratase | 0.55 | 384 |

| SA0732 | ClpP | ClpP | 1.07 | 729 |

| SA0775 | Hypothetical protein | 0.52 | 296 | |

| SA0787 | IS1181 transposase | 0.37 | 242 | |

| SA0802 | NADH dehydrogenase-like protein SA0802 | 0.94 | 411 | |

| SA0820 | GlpQ | Glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase | 2.31 | 569 |

| SA0820 | GlpQ | Glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase | 1.72 | 570 |

| SA0823 | Pgi | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 1.10 | 378 |

| SA0829 | Hypothetical protein | 0.16 | 573 | |

| SA0831 | Cdr | Coenzyme A disulphide reductase | 2.08 | 349 |

| SA0842 | FabH | FabH, 3-oxoacyl-(acyl carrier protein) synthase homologue | 1.04 | 489 |

| SA0843 | Fab (FabF) | 3-oxoacyl-synthase | 0.94 | 362 |

| SA0900 | SspB1 | Cysteine protease precursor SspB | 1.72 | 427 |

| SA0900 | SspB1 | Cysteine protease precursor SspB | 1.25 | 432 |

| SA0900 | SspB1 | Cysteine protease precursor SspB | 2.53 | 468 |

| SA0900 | SspB1 | Cysteine protease precursor SspB | 1.51 | 825 |

| SA0901 | SspA | V8 protease | 0.77 | 474 |

| SA0901 | SspA | V8 protease | 1.26 | 478 |

| SA0901 | SspA | V8 protease | 1.30 | 483 |

| SA0901 | SspA | V8 protease | 1.73 | 486 |

| SA0901 | SspA | V8 protease | 0.39 | 507 |

| SA0901 | SspA | V8 protease | 1.47 | 511 |

| SA0901 | SspA | V8 protease | 1.37 | 490 |

| SA0904 | Atl | ATL autolysin transcription regulator | 0.28 | 163 |

| SA0908 | Hypothetical protein | 1.80 | 417 | |

| SA0908 | Hypothetical protein | 1.90 | 419 | |

| SA0935 | PtsI | Phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphatase | 0.09 | 244 |

| SA0939 | Hypothetical protein | 0.12 | 676 | |

| SA0945 | PdhC | Branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase subunit E2 | 0.47 | 192 |

| SA0946 | PdhD | Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase | 1.04 | 287 |

| SA1007 | Hla | Alpha-haemolysin | 5.28 | 531 |

| SA1007 | Hla | Alpha-haemolysin | 2.71 | 536 |

| SA1007 | Hla | Alpha-haemolysin | 5.04 | 539 |

| SA1007 | Hla | Alpha-haemolysin | 4.60 | 541 |

| SA1007 | Hla | Alpha-haemolysin | 1.92 | 651 |

| SA1036 | IleS | Isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase | 0.41 | 132 |

| SA1098 | CodY | Transcriptional repressor CodY | 2.87 | 617 |

| SA1099 | RpsB | 30S ribosomal protein S2 | 0.55 | 514 |

| SA1100 | Tsf | Elongation factor Ts | 2.23 | 459 |

| SA1100 | Tsf | Elongation factor Ts | 1.58 | 470 |

| SA1128 | RecA | Recombinase A | 0.79 | 389 |

| SA1150 | GlnA | Glutamine–ammonia ligase | 1.70 | 323 |

| SA1170 | KatA | Catalase | 1.87 | 263 |

| SA1177 | Tkt | Transketolase | 0.40 | 197 |

| SA1177 | Tkt | Transketolase | 1.31 | 201 |

| SA1177 | Tkt | Transketolase | 3.11 | 401 |

| SA1533 | AckA | Acetate kinase homologue | 0.40 | 393 |

| SA1184 | CitB (AcnA) | Aconitate hydratase | 0.23 | 128 |

| SA1216 | PepF | Hypothetical protein, similar to oligoendopeptidase | 33.50 | 215 |

| SA1283 | Pbp2 | PBP2 | 0.57 | 220 |

| SA1308 | RpsA | 30S ribosomal protein S1 | 0.43 | 363 |

| SA1336 | Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase | 1.50 | 250 | |

| SA1342 | Gnd | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | 2.22 | 391 |

| SA1342 | Gnd | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | 2.20 | 400 |

| SA1359 | Efp | Elongation factor P | 0.40 | 560 |

| SA1409 | DnaK | Molecular chaperone DnaK | 0.69 | 226 |

| SA1409 | DnaK | Molecular chaperone DnaK | 2.15 | 546 |

| SA1499 | Tig | Trigger factor | 0.10 | 231 |

| SA1520 | PykA | Pyruvate kinase | 0.68 | 203 |

| SA1529 | Metal-dependent hydrolase | 6.88 | 669 | |

| SA1553 | Fhs | Formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase | 2.57 | 273 |

| SA1553 | Fhs | Formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase | 1.16 | 277 |

| SA1579 | LeuS | Leucyl-tRNA synthetase | 2.68 | 143 |

| SA1599 | Tal | Hypothetical protein, similar to transaldolase | 1.17 | 659 |

| SA1609 | PckA | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | 2.05 | 279 |

| SA1627 | SplF | Serine protease SplE, putative | 2.93 | 667 |

| SA1627 | SplF | Serine protease SplE, putative | 7.46 | 660 |

| SA1627 | SplF | Serine protease SplE, putative | 7.88 | 670 |

| SA1628 | SplD | Serine protease SplD | 4.68 | 666 |

| SA1629 | SplC | Serine protease SplC | 4.43 | 656 |

| SA1629 | SplC | Serine protease SplC | 1.41 | 657 |

| SA1630 | SplB | Serine protease SplB | 6.64 | 646 |

| SA1631 | SplA | Serine protease SplA | 4.55 | 642 |

| SA1631 | SplA | Serine protease SplA | 2.01 | 647 |

| SA1637 | LukD | Leukotoxin, LukD | 1.22 | 487 |

| SA1653 | TRAP | Signal transduction protein TRAP | 6.36 | 914 |

| SA1695 | AmpS | Aminopeptidase ampS | 1.34 | 397 |

| SA1709 | Ferritin | 0.32 | 910 | |

| SA1725 | SspB2 | Staphopain, cysteine proteinase | 1.76 | 725 |

| SA1725 | SspB2 | Staphopain, cysteine proteinase | 6.01 | 754 |

| SA1811 | Hlb | Beta-haemolsysin | 1.28 | 505 |

| SA1811 | Hlb | Beta-haemolsysin | 1.02 | 509 |

| SA1811 | Hlb | Beta-haemolsysin | 0.38 | 515 |

| SA1811 | Hlb | Beta-haemolsysin | 5.31 | 519 |

| SA1811 | Hlb | Beta-haemolsysin | 2.31 | 520 |

| SA1811 | Hlb | Beta-haemolsysin | 0.29 | 522 |

| SA1811 | Hlb | Beta-haemolsysin | 0.65 | 574 |

| SA1812 | Uncharacterized leukocidin-like protein 1 precursor | 1.64 | 499 | |

| SA1812 | Uncharacterized leukocidin-like protein 1 precursor | 2.19 | 500 | |

| SA1812 | Uncharacterized leukocidin-like protein 1 precursor | 1.21 | 502 | |

| SA1813 | Uncharacterized leukocidin-like protein 2 precursor | 0.72 | 494 | |

| SA182 | SodA (SodA2) | Superoxide dismutase SodA | 1.53 | 697 |

| SA1836 | GroEL | Chaperonin GroEL | 0.37 | 267 |

| SA1898 | Hypothetical protein, similar to SceD precursor | 0.27 | 552 | |

| SA1905 | AtpD | F0F1 ATP synthase subunit beta | 0.28 | 383 |

| SA1915 | GlyA | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase | 1.24 | 364 |

| SA1915 | GlyA | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase | 0.90 | 367 |

| SA1927 | FbaA | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | 0.61 | 530 |

| SA1959 | GlmS | Glucosamine-fructose-6-phosphate transferase | 1.12 | 218 |

| SA1984 | Asp23 | Alkaline shock protein 23 | 1.66 | 827 |

| SA2003 | HysA | Hyaluronate lyase precursor | 0.30 | 156 |

| SA2093 | SsaA | Secretory antigen precursor SsaA homologue | 0.09 | 592 |

| SA2093 | SsaA | Secretory antigen precursor SsaA homologue | 0.10 | 593 |

| SA2097 | Hypothetical protein, similar to secretory antigen precursor SsaA | 0.24 | 860 | |

| SA2204 | GpmA | Phosphoglycerate mutase, pgm homologue | 3.01 | 583 |

| SA2204 | GpmA | Phosphoglycerate mutase, pgm homologue | 1.36 | 585 |

| SA2206 | Sbi | IgG-binding protein SBI | 0.29 | 387 |

| SA2208 | HlgC | Gamma-haemolysin component C | 3.73 | 535 |

| SA2209 | HlgB | Gamma-haemolysin component B | 2.47 | 497 |

| SA2334 | MmvaS | 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthase | 0.68 | 434 |

| SA2336 | ClpL | ATP-dependent Clp proteinase chain clpL | 0.35 | 210 |

| SA2356 | IsaA | Immunodominant antigen A | 0.23 | 616 |

| SA2356 | IsaA | Immunodominant antigen A | 0.22 | 635 |

| SA2356 | IsaA | Immunodominant antigen A | 2.08 | 747 |

| SA2356 | IsaA | Immunodominant antigen A | 1.43 | 822 |

| SA2356 | IsaA | Immunodominant antigen A | 0.24 | 908 |

| SA2430 | Aur | Zinc metalloproteinase aureolysin | 0.21 | 471 |

| SA2430 | Aur | Zinc metalloproteinase aureolysin | 0.79 | 496 |

| SA2437 | Hypothetical protein, similar to autolysin precursor | 0.36 | 191 | |

| SA2437 | Hypothetical protein, similar to autolysin precursor | 0.19 | 193 | |

| SA2437 | Hypothetical protein, similar to autolysin precursor | 0.16 | 195 | |

| SA2437 | Hypothetical protein, similar to autolysin precursor | 0.11 | 200 | |

| SA2437 | Hypothetical protein, similar to autolysin precursor | 0.88 | 223 | |

| SA2437 | Hypothetical protein, similar to autolysin precursor | 1.11 | 235 | |

| SA2437 | Hypothetical protein, similar to autolysin precursor | 1.15 | 236 | |

| SA2437 | Hypothetical protein, similar to autolysin precursor | 0.10 | 245 | |

| SA2437 | Hypothetical protein, similar to autolysin precursor | 0.78 | 269 | |

| SA2437 | Hypothetical protein, similar to autolysin precursor | 0.41 | 422 |

Table of all identified protein spots from the extracellular fraction. Data for proteins with a spot vol. ratio of ≥2 and ≤0.5 are shown. All proteins had a significance level of 0.05 or less (T test 5 % cut-off). Proteins highlighted in italics are significantly changed in the two phases of growth

For the 2D gel analysis of extracellular proteins, culture supernatant was treated with 10 % (w/v) fresh TCA to precipitate all extracellular proteins. Figures 5 and 6 show the extracellular protein expression of S. aureus in early exponential phase (OD600 1.0) and stationary phase (16 h incubation). In total, 103 different proteins were identified in the extracellular protein fraction. Nine proteins showed an increase in the amount in stationary phase and 13 proteins showed a decrease in level compared with exponential phase (Table 5). As expected, virulence determinants that are involved in host defence evasion as well as invasion and tissue penetration showed an increased level in stationary phase. For example, α-haemolysin (Hla) was over 4.5-fold increased in level in stationary phase. Also, the glycerol ester hydrolase (Geh) main spots were increased ninefold to 21-fold (Table 4). Decreased protein levels in stationary phase were shown by several hypothetical proteins as well as the peptidoglycan hydrolase (LytM), immunodominant antigen A (IsaA) and secretory antigen (SsaA).

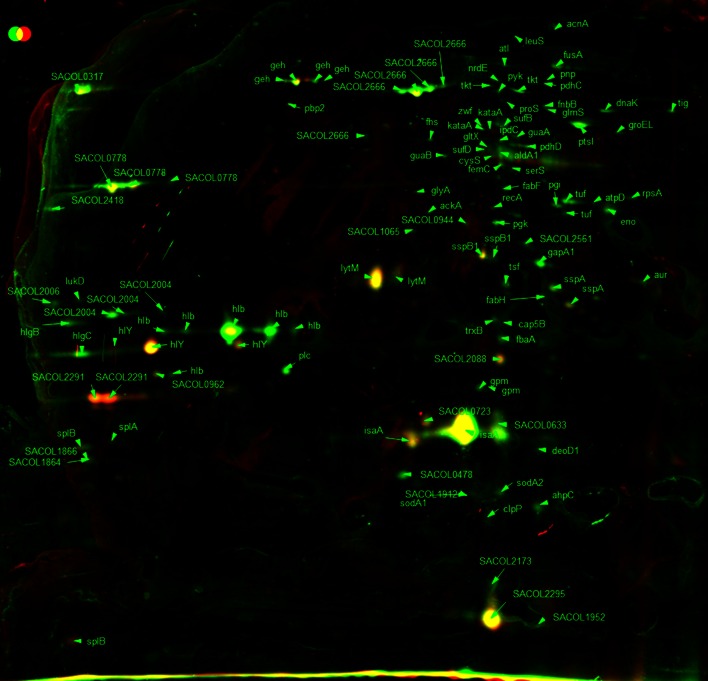

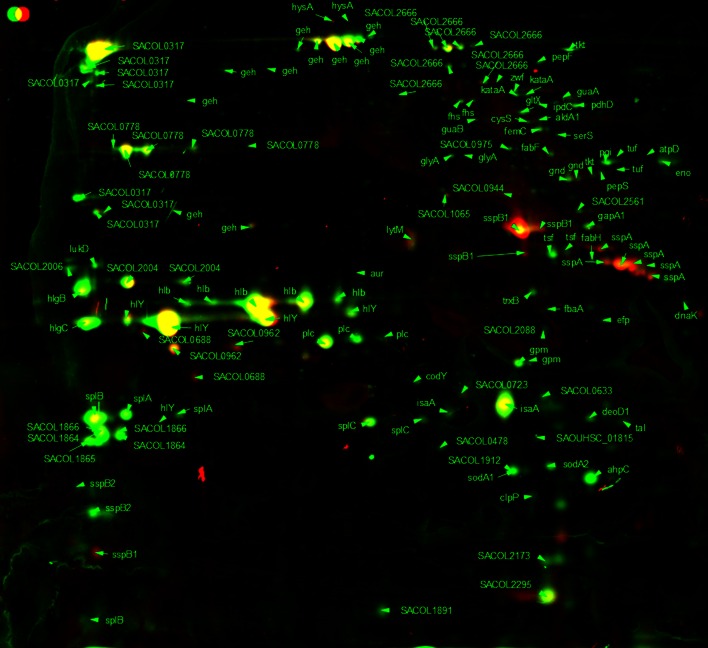

Fig. 5.

2D gel image false-colour dual-channel of extracellular proteins in exponential phase with and without C-6-H. Merged 2D gel images of S. aureus SH1000 extracellular proteins from exponential phase treated with or without 10 µg/ml C-6-H. Control gel shown in green, treated samples shown in red and equal expression shown in yellow. Spots were identified via MALDI-TOF

Fig. 6.

2D gel image false-colour dual-channel of extracellular proteins in stationary phase with and without C-6-H. Merged 2D gel images of S. aureus SH1000 extracellular proteins from stationary phase treated with or without 10 µg/ml C-6-H. Control gel shown in green, treated samples shown in red and equal expression shown in yellow. Spots were identified via MALDI-TOF

Table 5.

Growth phase-dependent changes in extracellular protein profile

| ORF N315 | Protein | Gene product | OD 1.0 versus 16 h | Spot ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA0265 | LytM | Peptidoglycan hydrolase | 0.15 | 454 |

| SA0265 | LytM | Peptidoglycan hydrolase | 0.13 | 460 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 3.08 | 171 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 9.64 | 199 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 21.07 | 229 |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 8.89 | 424 |

| SA0375 | GuaB | Inositol-monophosphate dehydrogenase | 0.34 | 308 |

| SA0393 | Set15 | Superantigen-like protein | 0.12 | 676 |

| SA0505 | FusA | Elongation factor G | 0.14 | 162 |

| SA0544 | Putative haem peroxidase | 0.21 | 618 | |

| SA0935 | PtsI | Phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphatase | 0.09 | 244 |

| SA0945 | PdhC | Branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase subunit E2 | 0.47 | 192 |

| SA1007 | Hla | Alpha-haemolysin | 5.28 | 531 |

| SA1007 | Hla | Alpha-haemolysin | 4.60 | 541 |

| SA1177 | Tkt | Transketolase | 0.40 | 197 |

| SA1499 | Tig | Trigger factor | 0.10 | 231 |

| SA1627 | SplF | Serine protease SplE, putative | 7.88 | 670 |

| SA1628 | SplD | Serine protease SplD | 4.68 | 666 |

| SA1630 | SplB | Serine protease SplB | 6.64 | 646 |

| SA1725 | Staphopain, cysteine proteinase | 6.01 | 754 | |

| SA1898 | Hypothetical protein, similar to SceD precursor | 0.27 | 552 | |

| SA2093 | SsaA | Secretory antigen precursor SsaA homologue | 0.09 | 592 |

| SA2093 | SsaA | Secretory antigen precursor SsaA homologue | 0.10 | 593 |

| SA2204 | GpmA | Phosphoglycerate mutase, pgm homologue | 3.01 | 583 |

| SA2208 | HlgC | Gamma-haemolysin component C | 3.73 | 535 |

| SA2209 | HlgB | Gamma-haemolysin component B | 2.47 | 497 |

| SA2356 | IsaA | Immunodominant antigen A | 0.22 | 635 |

| SA2437 | Hypothetical protein, similar to autolysin precursor | 0.16 | 195 | |

| SA2437 | Hypothetical protein, similar to autolysin precursor | 0.41 | 422 |

Comparison of the pattern of extracellular protein expression in exponential phase (OD600 1.0) and stationary phase of S. aureus. Data for proteins with a spot vol. ratio of ≥2 and ≤0.5 are shown. All genes had a significance level of 0.05 or less (T test 5 % cut-off)

In early exponential phase (OD600 1.0), the levels of 15 proteins were altered (≥twofold) in the presence of C-6-H (Table 6). Thirteen proteins showed a reduced level and 2 proteins showed an increased level in the presence of C-6-H. In stationary phase (16 h), 18 proteins showed an altered level of expression in the presence of C-6-H. Thirteen proteins were reduced and 5 were increased in level (Table 6). In the presence of C-6-H, several virulence determinants were reduced in level in exponential phase. The β-haemolysin (Hlb) and γ-haemolysin (HlgC) showed fivefold and 2.5-fold reduction in exponential phase. At stationary phase, Hlb showed no alteration due to C-6-H, but HlgC and HlgB were 3.5-fold reduced. The addition of C-6-H surprisingly showed no apparent effect on Hla level at either growth phase. The lipase (Geh) showed a growth phase-dependent response to C-6-H as it was reduced in exponential phase but induced in stationary phase (Table 5).

Table 6.

Effect of C-6-H on extracellular protein profile

| ORF N315 | Protein | Gene product | Expression C6H | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OD 1.0 | 16 h | Spot ID (OD 1.0) | Spot ID (16 h) | |||

| SA0131 | Pnp (deoD1) | Purine nucleoside phosphorylase | – | 0.33 | 654 | |

| SA0265 | LytM | Peptidoglycan hydrolase | 2.08 | – | 454 | |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | 0.23 | – | 421 | |

| SA0309 | Geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | – | 7.38 | 212 | |

| SA0366 | AhpC | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C | – | 0.18 | 712 | |

| SA0505 | FusA | Elongation factor G | 0.20 | – | 162 | |

| SA0506 | Tuf | Elongation factor Tu | 0.17 | – | 371 | |

| SA0820 | GlpQ | Glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase | – | 2.88 | 569 | |

| SA0843 | Fab (fabF) | 3-Oxoacyl-synthase | 0.10 | – | 362 | |

| SA0900 | SspB1 | Cysteine protease precursor SspB | – | 7.57 | 427 | |

| SA0900 | SspB1 | Cysteine protease precursor SspB | – | 5.78 | 432 | |

| SA0901 | SspA | V8 protease | – | 13.24 | 478 | |

| SA0901 | SspA | V8 protease | – | 9.44 | 483 | |

| SA0901 | SspA | V8 protease | – | 5.19 | 490 | |

| SA0935 | PtsI | Phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphatase | 0.18 | – | 244 | |

| SA1100 | Tsf | Elongation factor Ts | 0.47 | – | 470 | |

| SA1177 | Tkt | Transketolase | 0.25 | – | 201 | |

| SA1184 | CitB (acnA) | Aconitate hydratase | 0.13 | – | 128 | |

| SA1409 | Dnak | Molecular chaperone DnaK | 0.19 | – | 226 | |

| SA1627 | SplF | Serine protease SplE, putative | – | 0.36 | 670 | |

| SA1630 | SplB | Serine protease SplB | – | 0.29 | 646 | |

| SA1631 | SplA | Serine protease SplA | – | 0.27 | 642 | |

| SA1631 | SplA | Serine protease SplA | – | 0.13 | 647 | |

| SA1637 | LukD | Leukotoxin, LukD | – | 0.17 | 487 | |

| SA1671 | Hypothetical protein | – | 0.17 | 698 | ||

| SA1725 | SspB2 | Staphopain, cysteine proteinase | – | 0.19 | 754 | |

| SA1811 | Hlb | Beta-hemolsysin | 0.17 | – | 505 | |

| SA1811 | Hlb | Beta-hemolsysin | 0.19 | – | 509 | |

| SA1811 | Hlb | Beta-hemolsysin | 0.16 | – | 519 | |

| SA1812 | Hypothetical protein | – | 0.44 | 500 | ||

| SA1813 | Hypothetical protein | – | 0.07 | 494 | ||

| SA1959 | GlmS | Glucosamine-fructose-6-phosphate transferase | 0.05 | – | 218 | |

| SA2093 | SsaA | Secretory antigen precursor SsaA homologue | 4.74 | – | 592 | |

| SA2093 | SsaA | Secretory antigen precursor SsaA homologue | 6.24 | – | 593 | |

| SA2204 | GpmA | Phosphoglycerate mutase, pgm homologue | 0.08 | – | 585 | |

| SA2208 | HlgC | Gamma-haemolysin component C | 0.38 | – | 535 | |

| SA2208 | HlgC | Gamma-haemolysin component C | – | 0.33 | 535 | |

| SA2209 | HlgB | Gamma-haemolysin component B | – | 0.22 | 497 | |

| SA2356 | IsaA | Immunodominant antigen A | – | 0.28 | 616 | |

| SA2356 | IsaA | Immunodominant antigen A | – | 0.21 | 635 | |

| SA2356 | IsaA | Immunodominant antigen A | – | 0.16 | 747 | |

| SA2437 | Hypothetical protein, similar to autolysin | – | 0.43 | 223 | ||

| SA2437 | Hypothetical protein, similar to autolysin | – | 2.38 | 236 | ||

Comparison of extracellular protein production in exponential phase (OD600 1.0) and stationary phase in the presence of sub-MIC C-6-H. Data for proteins with a spot vol. ratio of ≥2 and ≤0.5 are shown. All proteins had a significance level of 0.05 or less (T test 5 % cut-off)

One hundred and sixty-six cytoplasmic soluble proteins were identified in total and analysed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. The differences in protein expression of exponential and stationary phase cell growth are shown in Table 7, and the effects of C-6-H are shown in Table 8 and Figs. 7, 8. The cytoplasmic proteins of S. aureus in early exponential phase (OD600 1.0) and stationary phase (16 h incubation) were compared. Twenty proteins show an increase and 22 a decrease in level in stationary phase (Table 7), with a variety of predicted roles.

Table 7.

Growth phase-dependent changes in cytoplasmic protein profile

| ORF N315 | Protein | Gene product | OD 1.0 versus 16 h |

|---|---|---|---|

| SA0149 | CapF | Capsular polysaccharide synthesis enzyme Cap5F | 2.18 |

| SA0218 | MB | Formate acetyltransferase | 3.20 |

| SA0224 | Hypothetical protein, similar to 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase | 28.28 | |

| SA0372 | Hypothetical protein | 4.24 | |

| SA0506 | Tuf | Elongation factor Tu | 0.28 |

| SA0506 | Tuf | Elongation factor Tu | 0.10 |

| SA0513 | Hypothetical protein | 0.35 | |

| SA0564 | ArgS | Arginyl-tRNA synthetase | 0.50 |

| SA0707 | Hypothetical protein | 3.06 | |

| SA0730 | Pgm | Phosphoglyceromutase | 0.30 |

| SA0755 | Organic hydroperoxide resistance protein-like | 2.34 | |

| SA0774 | Hypothetical protein | 0.34 | |

| SA0793 | DltA | d-alanine-poly(phosphoribitol) ligase subunit 1 | 0.40 |

| SA0842 | FabH | FabH, 3-oxoacyl-(acyl carrier protein) synthase homologue | 0.40 |

| SA0843 | Fab | 3-oxoacyl-synthase | 0.44 |

| SA0869 | FabI | Enoyl-(acyl carrier protein) reductase | 0.35 |

| SA0959 | GTP-binding elongation factor homologue | 0.32 | |

| SA1019 | Hypothetical protein | 2.19 | |

| SA1045 | PyrAA | Carbamoyl phosphate synthase small subunit | 0.39 |

| SA1073 | FabD | Malonyl CoA-acyl carrier protein transacylase | 0.48 |

| SA1096 | ClpQ | ATP-dependent protease peptidase subunit | 2.46 |

| SA1115 | RibC | Riboflavin kinase/FAD synthase ribC | 0.17 |

| SA1224 | ABC transporter (ATP-binding protein) homologue | 0.30 | |

| SA1224 | ABC transporter (ATP-binding protein) homologue | 0.36 | |

| SA1307 | EngA | GTP-binding protein engA | 0.34 |

| SA1309 | Cmk | Cytidylate kinase | 0.36 |

| SA1343 | Hypothetical protein, similar to tripeptidase | 7.03 | |

| SA1410 | GrpE | Heat shock protein GrpE | 0.46 |

| SA1456 | AspS | Aspartyl-tRNA synthetase | 0.49 |

| SA1456 | AspS | Aspartyl-tRNA synthetase | 0.41 |

| SA1522 | AccA | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase carboxyltransferase subunit alpha | 0.45 |

| SA1553 | Fhs | Formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase | 2.77 |

| SA1553 | Fhs | Formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase | 2.13 |

| SA1609 | PckA | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | 6.03 |

| SA1609 | PckA | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | 3.67 |

| SA1609 | PckA | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | 6.65 |

| SA1692 | Hypothetical protein | 2.37 | |

| SA1709 | Ferritin | 4.20 | |

| SA1724 | PurB | Adenylosuccinate lyase | 2.12 |

| SA1840 | Hypothetical protein | 2.02 | |

| SA1929 | PyrG | CTP synthase | 0.43 |

| SA1936 | LuxS | S-ribosylhomocysteinase | 0.39 |

| SA1984 | Asp23 | Alkaline shock protein 23 | 13.54 |

| SA1984 | Asp23 | Alkaline shock protein 23 | 10.13 |

| SA1984 | Asp23 | Alkaline shock protein 23 | 8.04 |

| SA2098 | Putative 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase SA2098 | 2.25 | |

| SA2125 | Formimidoylglutamase | 2.12 | |

| SA2240 | Hypothetical protein, similar to para-nitrobenzyl esterase chain A | 8.60 | |

| SA2317 | Hypothetical protein | 0.44 | |

| SA2336 | ClpL | ATP-dependent Clp proteinase chain clpL | 2.57 |

Comparison of the pattern of cytoplasmic protein expression in exponential phase (OD600 1.0) and stationary phase of S. aureus. Proteins with a spot vol. ratio of ≥2 and ≤0.5 are shown. All proteins had a significant level of 0.05 or less (T test 5 % cut-off)

Table 8.

Effect of C-6-H on cytoplasmic protein profile

| ORF N315 | Protein | Gene product | Expression C6H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OD600 1.0 | 16 h | |||

| SA0165 | Hypothetical protein, similar to alpha-helical coiled-coil | – | 0.15 | |

| SA0367 | NADPH-dependent oxidoreductase | – | 2.13 | |

| SA0419 | MetB | Cystathionine gamma-synthase | 2.11 | – |

| SA0506 | Tuf | Elongation factor Tu | 2.31 | – |

| SA0506 | Tuf | Elongation factor Tu | – | 2.46 |

| SA0513 | Hypothetical protein | 0.48 | – | |

| SA0707 | Hypothetical protein | 0.44 | – | |

| SA0758 | Hypothetical protein, similar to thioredoxin | 0.50 | – | |

| SA0869 | FabI | Enoyl-(acyl carrier protein) reductase | 0.40 | – |

| SA0884 | Lipoate-protein ligase homologue | – | 2.09 | |

| SA1045 | PyrAA | Carbamoyl phosphate synthase small subunit | 0.35 | – |

| SA1112 | InfB | Translation initiation factor IF-2 | – | 3.52 |

| SA1115 | RibC | Riboflavin kinase/FAD synthase ribC | 0.21 | – |

| SA1258 | Hypothetical protein | 0.10 | – | |

| SA1522 | AccA | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase carboxyltransferase subunit alpha | 0.35 | – |

| SA1868 | Hypothetical protein | 0.23 | – | |

| SA1943 | Hypothetical protein | 0.19 | – | |

| SA1959 | GlmS | Glucosamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase | – | 2.15 |

| SA1959 | GlmS | Glucosamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase | – | 2.95 |

| SA1959 | GlmS | Glucosamine-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase | 2.15 | – |

| SA1984 | Asp23 | Alkaline shock protein 23 | – | 0.37 |

| SA2084 | UreC | Urease subunit alpha | 14.42 | – |

| SA2085 | UreE | Urease accessory protein UreE | 5.85 | – |

| SA2085 | UreE | Urease accessory protein UreE | – | 3.28 |

| SA2098 | Putative 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase SA2098 | – | 2.09 | |

| SA2311 | Putative NAD(P)H nitroreductase SA2311 | – | 2.62 | |

| SA2312 | Ddh | d-lactate dehydrogenase | 2.44 | – |

| SA2336 | ClpL | ATP-dependent Clp proteinase chain clpL | – | 2.26 |

| SA2336 | ClpL | ATP-dependent Clp proteinase chain clpL | – | 2.62 |

| SA2400 | Mqo2 | Malate: quinone oxidoreductase | 0.44 | – |

| SA2400 | Mqo2 | Malate: quinone oxidoreductase | 0.27 | – |

Comparison of cytoplasmic protein expression in exponential phase (OD600 1.0) and stationary phase in the presence of sub-MIC C-6-H. Data for proteins with a spot vol. ratio of ≥2 and ≤0.5 are shown. All proteins had a significance level of 0.05 or less (T test 5 % cut-off)

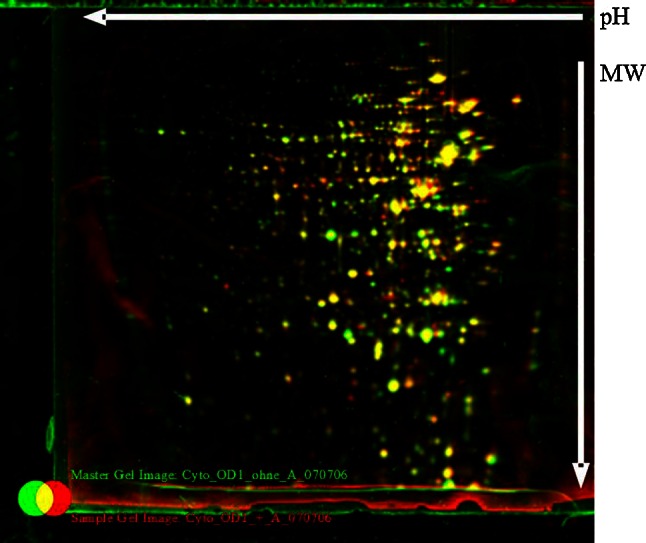

Fig. 7.

Comparison of the cytoplasmic protein pattern of S. aureus SH1000, with or without C-6-H, in exponential phase. Original staining and false-colour dual-channel images of 2D gels of cytoplasmic proteins without C-6-H (green) and with C-6-H (red). Proteins (200 µg) were isolated from the supernatant of SH1000 or grown in TSB−Fe medium to OD600 0.5, C-6-H was then added, and cultures were further incubated until OD600 1.0. Yellow protein spots represent equal amounts in both cultures, the green protein spots represent higher amounts in the culture without C-6-H, and protein spots that are red are present in higher amounts in the presence of C-6-H

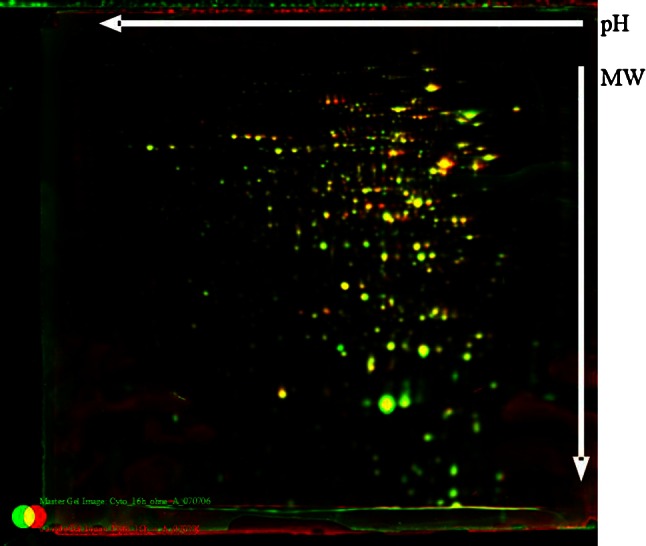

Fig. 8.

Comparison of the cytoplasmic protein pattern of S. aureus SH1000, with or without C-6-H, in stationary phase. Original staining and false-colour dual-channel images of 2D gels of cytoplasmic proteins without C-6-H (green) and with C-6-H (red). Proteins (200 µg) were isolated from the supernatant of SH1000 grown in TSB−Fe medium to OD600 0.5, C-6-H was then added, and cultures were further incubated for 16 h (stationary phase). Yellow protein spots represent equal amounts in both cultures, the green protein spots represent higher amounts in the culture without C-6-H, and protein spots that are red are present in higher amounts in the presence of C-6-H

In early exponential phase, the expression levels of 17 proteins were altered (≥2-fold) in the presence of C-6-H (Table 8). Eleven proteins showed a decrease and 6 an increase in level due to C-6-H. In stationary phase, 9 proteins were increased and 2 reduced in the presence of C-6-H. The greatest induction by C-6-H was seen for UreC in exponential phase (14-fold). Also, UreE showed a fivefold induction in protein level (Table 8). The increased urease level is in accordance with the array data (Table S1). A variety of other metabolic proteins were also affected by C-6-H, which alludes to a generalised effect of the inhibitor on cellular processes.

Conclusions