Abstract

Mutations in the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) gene cause familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), a disorder characterized by coronary heart disease (CHD) at young age. We aimed to apply an extreme sampling method to enhance the statistical power to identify novel genetic risk variants for CHD in individuals with FH. We selected cases and controls with an extreme contrast in CHD risk from 17 000 FH patients from the Netherlands, whose functional LDLR mutation was unequivocally established. The genome-wide association (GWA) study was performed on 249 very young FH cases with CHD and 217 old FH controls without CHD (above 65 years for males and 70 years of age for females) using the Illumina HumanHap550K chip. In the next stage, two independent samples (one from the Netherlands and one from Italy, Norway, Spain, and the United Kingdom) of FH patients were used as replication samples. In the initial GWA analysis, we identified 29 independent single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with suggestive associations with premature CHD (P<1 × 10−4). We examined the association of these SNPs with CHD risk in the replication samples. After Bonferroni correction, none of the SNPs either replicated or reached genome-wide significance after combining the discovery and replication samples. Therefore, we conclude that the genetics of CHD risk in FH is complex and even applying an ‘extreme genetics' approach we did not identify new genetic risk variants. Most likely, this method is not as effective in leveraging effect size as anticipated, and may, therefore, not lead to significant gains in statistical power.

Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is one of the leading causes of death.1 Multiple genetic risk variants with small to moderate effects on the susceptibility to CHD have been identified in genome-wide association (GWA) studies; however, these variants explain only a small fraction of the heritable component of the risk of CHD.2, 3 Therefore, many genetic variants remain to be discovered. Among the discovered genes, many are related to lipid metabolism.4, 5 New study designs will be necessary for uncovering additional associated variants. Selecting the populations who already have high lipid levels are well suited to search for genes that increase the risk of CHD beyond dyslipidemia.6 Therefore, we performed a GWA study in a selected sample of familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) patients having severe hypercholesterolemia caused by mutations in the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) gene (MIM 143890).7

Traditional GWA studies are performed on extremely large sample sizes including tens of thousands of individuals.8 In contrast, we used an extreme genetics approach to enhance the statistical power. In this method, only the individuals with an extreme of the phenotype are genotyped. In our study, we genotyped FH patients who had CHD at very young age as cases, and elderly patients who, despite their high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol level, had not experienced CHD as controls. We hypothesized that using this design would enhance the identification of additional genetic risk variants of CHD in FH.

Materials and methods

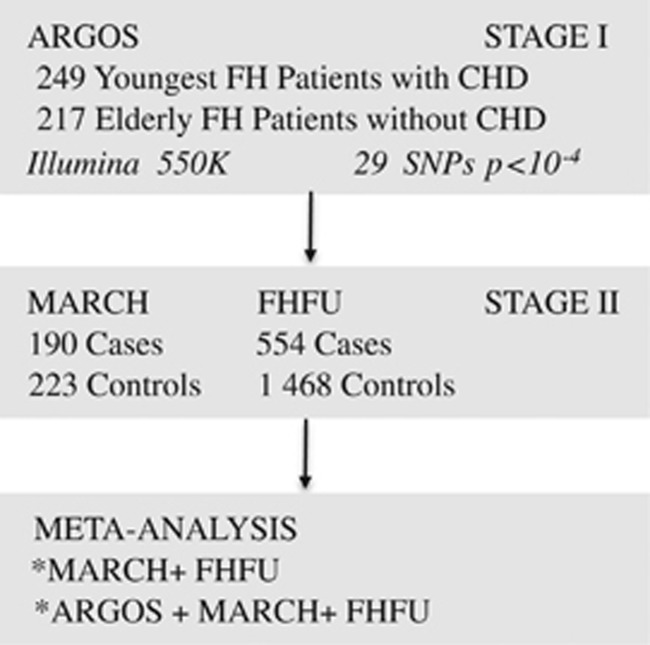

The schematic study design is shown in Figure 1. We performed the study in two stages. Stage I included a GWA study in the Dutch ‘Association of CHD Risk in a Genome-wide Old-versus-young Setting' (ARGOS) sample. Stage II consisted of genotyping of a second case–control sample, refer to as Mutations Associated with Risk of Cardiovascular disease in volunteers with Hypercholesterolemia (MARCH) and a large FH cohort, refer to as FH Follow-up (FHFU). All patients were of Caucasian descent. In ARGOS, this was confirmed by multi-dimensional scaling of identical-by-state pairwise distances. All patients gave informed consent and the local ethics committees approved the protocol.

Figure 1.

Study design. Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; FH, familial hypercholesterolemia; GWA, genome-wide association; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Description of the populations

Gene-finding stage

ARGOS. The ARGOS sample consists of 500 patients, who were selected from 17 000 Dutch FH patients with a mutation in the LDLR gene. They were recruited in the Netherlands by the nationwide molecular screening program of the ‘Stichting Opsporing Erfelijke Familiare Hypercholesterolemie'.9 Phenotypic data (including CHD events) were acquired from general practitioners and by reviewing medical records at the lipid and cardiologic clinics. We selected the 264 youngest patients with premature CHD and the 236 oldest patients without any CHD, stratified for sex. The maximum age of the female cases was 60 years and that of the male cases 45 years. The minimum age of the controls was 65 years for males and 70 years for females. First and second degree family members were excluded. CHD was defined as the presence of at least one of the following: (i) myocardial infarction (MI), proved by at least two of the following: (a) classical symptoms (>15 min), (b) specific abnormalities on electrocardiography, and (c) elevated cardiac enzymes (>2 × upper limit of normal); (ii) percutaneous coronary intervention or other invasive procedures; (iii) coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Patients with angina pectoris were excluded because in the majority of cases this diagnosis could not be assured by objective data.

MARCH

The MARCH study group consisted of 413 FH patients (190 cases, 223 controls), from Italy, Norway, Spain, and the United Kingdom. A few patients were born in another country but all were Caucasian. All patients had clinically proven FH and a mutation in either the LDLR or the APOB gene. The maximum age of the female cases was 59 and that of the male cases 45 years. The minimum age of the controls was 50 years for males and 60 for females. For the cases in this cohort, the same CHD definition was applied as described above for the ARGOS sample with the addition of (iv) angina pectoris (AP), as this phenotype was accurately addressed in this cohort. AP was diagnosed as classical symptoms in combination with at least one unequivocal positive result of one of the following: (a) exercise test, (b) nuclear scintigram, (c) dobutamine stress ultrasound, or (d) >70% stenosis on a coronary angiogram. The controls had no manifest CHD.

FHFU study

The second replication cohort consisted of Dutch clinically proven heterozygous FH patients who were recruited from 27 lipid clinics in the Netherlands between 1989 and 2002.10, 11 For the cases in this cohort, the same CHD definition was applied as described above for the MARCH sample. The controls had no manifest CHD. The DNA of 2073 unrelated patients was available for the present analysis. A total of 51 FH patients had already been included in the ARGOS sample and were, therefore, removed from the FHFU group, leaving 2022 DNA samples for analyses.

Additional cohorts

In addition to these three FH cohorts, selected single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were also genotyped in population-based cohorts that have been described in detail previously: The Rotterdam Study (n=5207, a cohort of elderly inhabitants of a suburb of Rotterdam, from which we selected patients with prevalent CHD to ascertain that CHD occurred at relatively young age; 777 CHD cases), deCODE (n=12 848, selected from the national Islandic deCODE database; 726 cases with premature MI) and GerMIFSII (n=2520, a German cohort with 1222 proven MI cases before the age of 60).12, 13, 14

Genotyping in ARGOS

The samples of participants of the ARGOS group were assayed with Illumina Infinium HumanHap550K Chips (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Samples were processed according to the Illumina Infinium II manual. In brief, each sample was whole-genome amplified, fragmented, precipitated, and resuspended in the appropriate hybridization buffer. After hybridization, these denatured samples were processed for the single-base extension reaction and were stained and imaged on an Illumina Bead Array Reader. Normalized bead-intensity data obtained for each sample were loaded into the Illumina Beadstudio software where the fluorescent intensities were converted into SNP genotypes. Using Quanto software (http://biostats.usc.edu/software) considering ARGOS as a conventional case–control study and assuming large effect sizes owing to only genotyping the phenotypic extremes, we estimated that had >80% statistical power to detect effect sizes >2.5 at a genome-wide significant level and than 1.46 for a P-value threshold of 0.05.

Genotyping frequencies have been deposited at the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ega/) which is hosted at the EBI, under accession number EGAS00001000734. The genotyping data are also available via the Dutch Biobanking and Biomolecular Research Infrastructure (https://catalogue.bbmri.nl/biobanks/, accession number 199).

Quality-control filtering

After genome-wide genotyping, a call-rate threshold above 98% was used for inclusion of the samples. Subjects were excluded from the sample if their sex was inconsistent with genetic data from the X chromosome and if duplicate samples produced inconsistent genotypes. SNPs were excluded if they had (i) successful genotyping in <90% of the cases and controls, (ii) a minor allele frequency <1% in the population, (iii) showed deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P-value<0.0001), or (iv) were monomorphic across all samples. After these exclusions, 535 179 SNPs remained.

Genotyping in MARCH and FHFU

In MARCH and FHFU, the genotypes of selected SNPs were determined using fluorescence-based TaqMan allelic discrimination assays and analyzed on an ABI Prism 7900 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Reaction components and amplification parameters were based on the manufacturer's instructions using an annealing temperature of 60 °C. Results were scored blinded to CHD status. SNPs were excluded following the same quality criteria as in the gene-finding stage.

Statistical analysis

The genomic inflation factor was calculated using the mean of the χ2-tests generated on all SNPs that were tested. For each SNP which passed the quality control in the ARGOS population, the association with risk of CHD was examined in an additive genetic model using a logistic regression model adjusted for sex. Given the fact that age was an inclusion criterion to generate the contrast between cases and controls of the ARGOS population, we did not adjust for age.

We selected all SNPs that were associated with CHD with a P-value <1.00 × 10−4 in ARGOS to analyze in the second stage. In the second stage, the association with risk of CHD was examined using logistic regression in MARCH and the FHFU. In MARCH, we adjusted for sex only, as age was a selection criterion similar to ARGOS. In the FHFU cohort, we adjusted for age, sex, and statin use, as statin use was expected to be a confounder and, in contrast to ARGOS and MARCH, it was well documented in that cohort. Using Bonferroni correction, significance threshold was 0.0017 (0.05/29). We performed a z-based meta-analysis to combine the results of MARCH and FHFU in the second stage. Furthermore, we combined the results of all three studies using z-based meta-analysis.

We used Plink version 1.03 to run GWA study in ARGOS, SPSS version 15 to run logistic regression models in MARCH and FHFU and finally ‘meta' and ‘rmeta' packages running under R to perform the meta-analysis.15, 16, 17

Replication of well-known SNPs associated with CHD

To test the effect of earlier defined genetic risk variants on CHD in ARGOS, we analyzed the SNPs described in a large-scale meta-analysis in the CARDIoGRAM consortium (22 233 cases and 64 762 controls). Whenever the SNP was not available on the IlluminaHap550, we used a proxy as identified by SNAP (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/snap/ldsearchs.php).

Results

Characteristics of the ARGOS cohort

Out of 17 000 Dutch FH patients with a known LDLR mutation, we selected the 264 youngest FH patients with CHD and the 236 oldest FH patients without any CHD. The mean±SD (range) age was 41.7±8.3 (23–59 years) in cases and 75.6±5.9 (65–years) in controls. A total of 249 cases and 217 controls were successfully genotyped. There were no significant differences in age, smoking, or plasma cholesterol levels between the patients who were and those who were not successfully genotyped (data not shown). General characteristics of the genotyped patients are shown in Table 1 and the age distribution in Supplementary Figure 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the ARGOS population and the replication populations.

| Diabetes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | N | Males (%) | Age (years) | Smoking (%) | Mellitus (%) | Hypertension (%) | Total Cholesterol (mmol/l) |

| Stage I: genome-wide analysis | |||||||

| ARGOS | |||||||

| CHD cases | 249 | 55.0 | 41.7±8.4a | 74.2a | 2.4a | 19.7a | 11.3±2.6a |

| Controls | 217 | 47.9 | 75.6±5.9a | 51.2a | 9.2a | 30.0a | 10.6±2.8a |

| Stage II: replication | |||||||

| MARCH | |||||||

| CHD cases | 190 | 63.2 | 39.4±7.4 | 49.5b | 10.0 | 36.3 | 11.0±2.2a |

| Controls | 223 | 60.1 | 63.6±9.2 | 47.1b | 11.2 | 34.5 | 10.5±1.7a |

| FHFU | |||||||

| CHD cases | 554 | 65.5a | 48.9±10.6a | 83.0a | 4.8a | 16.7a | 9.5±2.1 |

| Controls | 1468 | 43.5a | 46.6±12.7a | 70.3a | 1.7a | 6.0a | 9.4±1.9 |

Abbreviations: CHD, coronary heart disease; N, number of participants.

Continuous variables are given as mean±SD.

P<0.05 for the difference between CHD cases and controls within the cohort.

Cases and controls were matched for smoking in the MARCH Study.

Eighty-one cases (32.5%) had a negative LDLR mutation, for example, a mutation leading to complete loss of function of the LDL receptor, whereas only 42 controls (19.4%) had a receptor-negative mutation (P=0.004). This was mainly due to an overrepresentation of the c.1359-1G>A mutation, which was present in 46 cases and only in 21 controls. The other mutations were equally distributed (Supplementary Table 1). On average, the controls were 34 years older than the cases (P-value <0.001). Consequently, hypertension and diabetes mellitus were more often present in the controls than in the cases. More cases than controls were ever smokers (Table 1).

Stage I (GWA analysis)

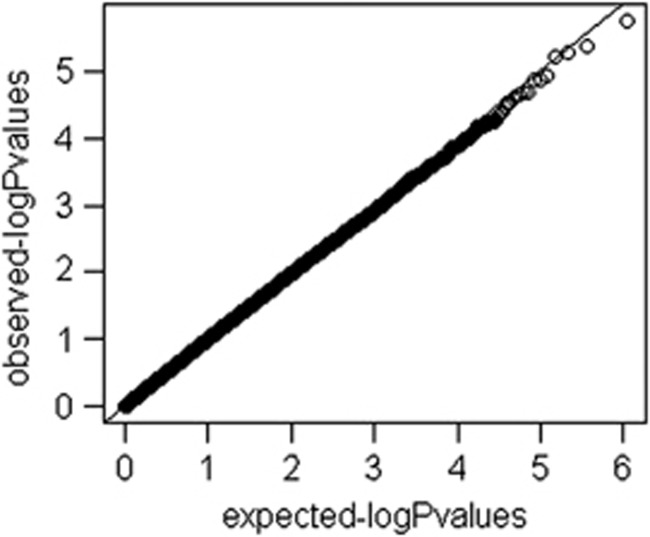

After quality-control filtering, we included 535 179 SNPs in the GWA analysis. A quantile–quantile plot of the observed against expected P-value distribution is shown in Figure 2. The genomic inflation factor (λgc) was 1.01 in the total sample. Supplementary Figure 2 illustrates the primary findings from the GWA analysis in the ARGOS population and presents P-values for each of the interrogated SNPs across the chromosomes. For a total of 40 SNPs clustered around 21 loci on all chromosomes except 3, 6, 12, 15, 16, and 18–21 the P-value was lower than the threshold of 1 × 10−4 (Table 2). Of these, 11 were in complete linkage disequilibrium (LD) with a leading SNP in the same locus. Twelve out of 40 SNPs were located in a cluster on chromosome 11p15; they were located in four different LD blocks and could be tagged by six SNPs. We took 29 SNPs, including the 6 SNPs in11p15, to stage II.

Figure 2.

QQ Plot.

Table 2. SNPs influencing coronary heart disease risk in the ARGOS population (with P<1.0 × 10−4).

| SNP | Chr | Position | Accession number | Reference allele | Alternate allele | SNP type | Gene | Freq cases | Freq controls | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs12087224 | 1p22 | 83 902 972 | NT_032977.8 | G | A | Intergenic | TTLL7 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 2.54 | 1.59–4.04 | 8.86 × 10−5 |

| rs7581691 | 2p24 | 13 953 005 | NT_005334.15 | G | A | — | — | 0.16 | 0.07 | 2.62 | 1.67–4.11 | 2.93 × 10−5 |

| rs1406333 | 2q32 | 184 155 187 | NT_005403.16 | A | G | Intergenic | NUP35 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.59 | 0.45–0.77 | 8.23 × 10−5 |

| rs2412397 | 4q12 | 53 804 380 | NT_022853.14 | A | G | Intronic | SCFD2 | 0.31 | 0.44 | 0.57 | 0.43–0.76 | 9.98 × 10−5 |

| rs778940 | 4q13 | 62 926 680 | NT_022778.15 | A | G | Intergenic | LPHN3 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 2.44 | 1.57–3.77 | 6.74 × 10−5 |

| rs6835823 | 4q32 | 155 191 807 | NT_016354.18 | A | C | Intergenic | DCHS2 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 1.77 | 1.36–2.30 | 2.11 × 10−5 |

| rs4696207 | 4q32 | 155 488 838 | NT_016354.18 | C | A | Intronic | DCHS2 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 1.80 | 1.36–2.38 | 3.36 × 10−5 |

| rs7691894 | 4q32 | 167 900 239 | NT_022792.17 | A | G | Intronic | SPOCK3 | 0.39 | 0.23 | 2.06 | 1.53–2.77 | 1.74 × 10−6 |

| rs11950716 | 5p15.2 | 14 141 834 | NT_006576.15 | G | A | Intergenic | TRIO | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.51 | 0.36–0.71 | 9.45 × 10−5 |

| rs17638888 | 7q22 | 98 335 561 | NT_007933.14 | G | A | Intronic | TRRAP | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.27 | 0.14–0.51 | 5.89 × 10−5 |

| rs12544799 | 8q24.2 | 130 732 692 | NT_008046.15 | A | G | Intergenic | MLZE | 0.41 | 0.28 | 1.87 | 1.40–2.50 | 2.53 × 10−5 |

| rs6985166 | 8q24.2 | 130 748 358 | NT_008046.15 | A | G | Intergenic | MLZE | 0.38 | 0.26 | 1.81 | 1.35–2.43 | 7.81 × 10−5 |

| rs13291498 | 9p21 | 28 326 185 | NT_008413.17 | A | C | Intronic | LINGO2 | 0.21 | 0.33 | 0.55 | 0.41–0.73 | 5.44 × 10−5 |

| rs10761805 | 10q21 | 65 294 147 | NT_008583.16 | G | A | Intergenic | REEP3 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 1.89 | 1.42–2.51 | 1.36 × 10−5 |

| rs955353 | 10q21 | 65 314 593 | NT_008583.16 | G | A | — | — | 0.37 | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.43–0.75 | 7.20 × 10−5 |

| rs2111995 | 10q25 | 107 497 352 | NT_030059.12 | A | G | Intergenic | SORCS3 | 0.28 | 0.17 | 1.97 | 1.42–2.72 | 4.10 × 10−5 |

| rs2647547 | 11p15 | 5 359 744 | NT_009237.17 | A | C | Intergenic | OR51M1 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 1.75 | 1.33–2.31 | 5.85 × 10−5 |

| rs1532514 | 11p15 | 5 373 198 | NT_009237.17 | C | A | Intergenic | OR51M1 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 1.71 | 1.32–2.23 | 6.37 × 10−5 |

| rs10838092 | 11p15 | 5 400 443 | NT_009237.17 | G | A | Exonic | OR51Q1 | 0.45 | 0.31 | 1.73 | 1.32–2.26 | 6.73 × 10−5 |

| rs10838102 | 11p15 | 5 414 207 | NT_009237.17 | G | A | Intergenic | OR51I1 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 1.78 | 1.36–2.33 | 3.06 × 10−5 |

| rs1498486 | 11p15 | 5 418 567 | NT_009237.17 | A | C | Exonic | OR51I1 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 1.81 | 1.38–2.38 | 2.02 × 10−5 |

| rs2133235 | 11p15 | 5 423 352 | NT_009237.17 | C | A | Intergenic | OR51I1 | 0.44 | 0.30 | 1.82 | 1.28–2.40 | 2.27 × 10−5 |

| rs2846186 | 11q25 | 134 203 586 | NT_033899.7 | A | G | Intergenic | B3GAT1 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.36–0.68 | 1.18 × 10−5 |

| rs2661969 | 11q25 | 134 223 427 | NT_033899.7 | A | G | Intergenic | B3GAT1 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.54 | 0.39–0.73 | 9.16 × 10−5 |

| rs1380945 | 13q13 | 31 739 619 | NT_024524.13 | A | G | Intronic | FRY | 0.48 | 0.35 | 1.74 | 1.32–2.30 | 9.76 × 10−5 |

| rs4982548 | 14q11 | 21 605 911 | NT_026437.11 | G | A | Intergenic | OR4E2 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.42–0.73 | 2.43 × 10−5 |

| rs2531851 | 17p13 | 9 141 140 | NT_010718.15 | G | A | Intronic | STX8 | 0.40 | 0.27 | 1.92 | 1.43–2.59 | 1.40 × 10−5 |

| rs5755595 | 22q12 | 33 848 839 | NT_011520.11 | G | A | Intergenic | RAXLX | 0.38 | 0.26 | 1.84 | 1.36–2.48 | 6.28 × 10−5 |

| rs5928090 | Xp21 | 32 780 853 | NT_011757.15 | A | G | — | — | 0.42 | 0.27 | 1.75 | 1.18–2.60 | 4.20 × 10−5 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; Chr, chromosome; Freq, frequency; OR, odds ratio; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Chromosome base position according to NCBI Genome build 36.3. Intergenic is defined as <500 Mb from the gene.

Stage II

We successfully genotyped 28 SNPs in MARCH and all 29 SNPs in FHFU (Supplementary Table 2). For none of the SNPs, the P-value was lower than the Bonferroni corrected threshold of 0.017 either in MARCH or FHFU. The smallest P-value was found for rs176388 (odds ratio OR 0.33, P=0.042) in MARCH. Although the direction of the effect was the same in FHFU, the association was not significant (OR 0.80, P=0.36). We performed a meta-analysis to combine the results of the analysis in MARCH and FHFU. None of the SNPs reached the Bonferroni significant threshold after combining the results of MARCH and FHFU.

Finally, we combined the results of ARGOS, MARCH, and FHFU; however, none of the top SNPs identified in ARGOS reached the genome-wide significance level. The smallest combined P-value was 4 × 10−4 for rs176388, for which the A allele showed a protective effect in all cohorts. Second best was rs1380945, for which all cohorts showed that the G allele was associated with increased CHD risk (Table 3 and Supplementary Figure 3).

Table 3. Results of the genome-wide association study in the two FH replication populations.

| MARCH (n=413) | FHFU (N=2022) | Meta-analysis MARCH+FHFU | Meta-analysis ARGOS+MARCH +FHFU | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Risk allele | OR | P-value | OR | P-value | OR | P-value | OR | P-value |

| rs12087224 | A | 1.01 | 0.96 | 1.06 | 0.70 | 1.04 | 0.73 | 1.27 | 3.1 × 10−2 |

| rs7581691 | A | 1.07 | 0.79 | 0.86 | 0.35 | 0.91 | 0.51 | 1.20 | 1.2 × 10−1 |

| rs1406333 | G | 0.98 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.71 | 0.98 | 0.68 | 0.84 | 1.5 × 10−2 |

| rs2412397 | G | NA | NA | 0.91 | 0.36 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| rs778940 | G | 0.86 | 0.53 | 1.29 | 0.06 | 1.16 | 0.17 | 1.35 | 2.9 × 10−3 |

| rs6835823 | C | 1.07 | 0.63 | 0.94 | 0.66 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 1.24 | 8.4 × 10−3 |

| rs4696207 | A | 0.90 | 0.48 | 1.10 | 0.33 | 1.03 | 0.70 | 1.19 | 1.4 × 10−2 |

| rs7691894 | G | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.74 | 1.02 | 0.80 | 1.20 | 1.2 × 10−2 |

| rs11950716 | A | 0.83 | 0.35 | 0.94 | 0.60 | 0.91 | 0.34 | 0.78 | 5.8 × 10−3 |

| rs17638888 | A | 0.52 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.36 | 0.69 | 0.05 | 0.54 | 2.0 × 10−4 |

| rs12544799 | G | 1.06 | 0.70 | 0.94 | 0.52 | 0.98 | 0.77 | 1.14 | 7.6 × 10−2 |

| rs6985166 | G | 1.05 | 0.76 | 1.09 | 0.38 | 1.08 | 0.36 | 1.22 | 6.4 × 10−3 |

| rs13291498 | C | 0.92 | 0.62 | 1.22 | 0.06 | 1.12 | 0.21 | 0.92 | 2.9 × 10−1 |

| rs10761805 | A | 1.05 | 0.76 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.87 | 1.18 | 2.2 × 10−2 |

| rs955353 | A | 0.88 | 0.36 | 1.01 | 0.91 | 0.97 | 0.67 | 0.85 | 1.9 × 10−2 |

| rs2111995 | G | 0.81 | 0.22 | 1.14 | 0.23 | 1.03 | 0.74 | 1.20 | 2.3 × 10−2 |

| rs2647547 | C | 0.98 | 0.90 | 1.04 | 0.67 | 1.02 | 0.79 | 1.17 | 2.4 × 10−2 |

| rs1532514 | A | 1.04 | 0.79 | 1.01 | 0.88 | 1.02 | 0.81 | 1.16 | 2.6 × 10−2 |

| rs10838092 | A | 1.09 | 0.59 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.02 | 0.80 | 1.18 | 2.4 × 10−2 |

| rs10838102 | A | 1.20 | 0.21 | 0.96 | 0.70 | 1.03 | 0.71 | 1.19 | 1.5 × 10−2 |

| rs1498486 | C | 1.11 | 0.45 | 1.07 | 0.51 | 1.08 | 0.34 | 1.23 | 3.1 × 10−3 |

| rs2133235 | A | 1.20 | 0.22 | 1.93 | 0.48 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 1.17 | 2.5 × 10−2 |

| rs2846186 | G | 0.83 | 0.26 | 1.06 | 0.63 | 0.97 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 1.1 × 10−2 |

| rs2661969 | G | 0.83 | 0.23 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 0.35 | 0.79 | 4.9 × 10−3 |

| rs1380945 | G | 1.25 | 0.13 | 1.14 | 0.19 | 1.17 | 0.06 | 1.29 | 3.0 × 10−4 |

| rs4982548 | A | 1.02 | 0.89 | 1.07 | 0.45 | 1.05 | 0.48 | 0.91 | 1.7 × 10−1 |

| rs2531851 | A | 1.07 | 0.63 | 0.89 | 0.23 | 0.95 | 0.51 | 1.11 | 1.4 × 10−1 |

| rs5755595 | A | 0.80 | 0.15 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.86 | 0.10 | 1.05 | 5.4 × 10−1 |

| rs5928090 | G | 1.04 | 0.73 | 0.95 | 0.54 | 0.98 | 0.73 | 1.08 | 2.3 × 10−1 |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Combined P-value given for replication populations.

Genotyping additional cohorts from the general population did not show any genome-wide significance.

Replication of well-known SNPs associated with CHD in the general population

To examine if the genetic risk variants identified in GWA studies in the general population also showed an effect in ARGOS and to test whether effect sizes were larger in our ‘extreme genetics' population, we examined the association of 25 previously reported genetic risk factors in CARDIoGRAM. In this meta-analysis, 9 out of 12 previously reported CHD loci were confirmed with a P-value of <5.0 × 108 and 13 new ones identified (Table 4).5 None of the studied SNPs were significantly associated with CHD in ARGOS. Lowest P-values were obtained for rs4977574 at 9p21 (CARDIoGRAM OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.23–1.36; P=1.35 × 10−22; ARGOS OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.00–1.67; P=0.05) and for the SNP in the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) gene that did not show genomic signficance in CARDIoGRAM (CARDIoGRAM OR 1.08, 95% CI 1.05–1.11; P=9.1 × 10−8; ARGOS OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.10–2.12, P=0.01).

Table 4. Results of earlier identified genetic risk factors in ARGOS5.

| CARDIoGRAM | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Chr | Gene(s) in region | Accession number | Ref. allele | Risk allele (frequency) | OR | P-value | Genotyped | Proxya | ORb | P-value |

| rs11206510 | 1p32.3 | PCSK9 | NT_032977.9 | C | T (0.82) | 1.08 | 9.1 × 10−8 | Yes | 1.52 | 0.01 | |

| rs17114036c | 1p32.2 | PPAP2B | NT_039277.8 | G | A (0.91) | 1.17 | 2.2 × 10−6 | No | rs9970807 | 0.87 | 0.56 |

| rs599839 | 1p13.3 | SORT1 | NT_019273.18 | G | A (0.78) | 1.11 | 2.9 × 10−10 | No | rs646776 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| rs17465637 | 1q41 | MIA3 | NT_021877.18 | A | C (0.74) | 1.14 | 1.4 × 10−8 | No | No proxy | ||

| rs6725887 | 2q33.1 | WDR12 | NT_005403.16 | T | C (0.15) | 1.14 | 1.1 × 10−9 | Yes | 1.07 | 0.76 | |

| rs2306374 | 3q22.3 | MRAS | NT_005612.15 | T | C (0.18) | 1.12 | 3.3 × 10−8 | Yes | 0.96 | 0.81 | |

| rs12526453 | 6p24.1 | PHACTR1 | NT_007592.14 | G | C (0.67) | 1.10 | 1.2 × 10−9 | No | rs4714990 | 1.03 | 0.8 |

| rs17609940c | 6p21.31 | ANKS1A | NT_007592.14 | C | G (0.75) | 1.07 | 2.2 × 10−6 | No | rs820082 | 0.83 | 0.25 |

| rs12190287c | 6q23.2 | TCF21 | NT_025741.14 | G | C (0.62) | 1.08 | 4.6 × 10−11 | No | No proxy | ||

| rs3798220 | 6q25.3 | LPA | NT_007422.13 | T | C(0.02) | 1.09 | 3.0 × 10−11 | No | No LD data | ||

| rs11556924c | 7q32.2 | ZC3HC1 | NT_007933.14 | T | C (0.62) | 1.09 | 2.2 × 10−9 | No | No proxy | ||

| rs4977574 | 9p21.3 | CDKN2A, CDKN2B | NT_008413.17 | A | G (0.46) | 1.25 | 1.4 × 10−22 | Yes | 1.28 | 0.05 | |

| rs579459c | 9q34.2 | ABO | NT_035014.4 | T | C (0.21) | 1.10 | 1.2 × 10−7 | No | rs495828 | 1.35 | 0.08 |

| rs1746048 | 10q11.21 | CXCL12 | NT_033985.6 | T | C (0.87) | 1.33 | 2.9 × 10−10 | Yes | 1.41 | 0.1 | |

| rs12413409c | 10q24.32 | CYP17A1, CNNM2, NT5C2 | NT_030059.12 | A | G (0.89) | 1.12 | 1.5 × 10−6 | Yes | 1.23 | 0.36 | |

| rs964184c | 11q23.3 | ZNF259, APOA5-A4-C3-A1 | NT_03899.8 | C | G (0.13) | 1.13 | 8.0 × 10−10 | No | No proxy | ||

| rs3184504 | 12q24.12 | SH2B3 | NT_033899.7 | C | T (0.44) | 1.13 | 6.4 × 10−6 | Yes | 1.01 | 0.96 | |

| rs4773144c | 13q34 | COL4A1, COL4A2 | NT_009952.14 | A | G (0.44) | 1.07 | 4.2 × 10−7 | No | No proxy | ||

| rs2895811c | 14q32.2 | HHIPL1 | NT_026437.11 | T | C (0.43) | 1.07 | 2.7 × 10−7 | Yes | 1.05 | 0.72 | |

| rs3825807c | 15q25.1 | ADAMTS7 | NT_01094.16 | G | A (0.57) | 1.08 | 9.6 × 10−6 | No | rs7177699 | NA | NA |

| rs216172c | 17p13.3 | SMG6, SRR | NT_010718.15 | G | C (0.37) | 1.07 | 6.2 × 10−7 | No | rs2281727 | 0.85 | 0.26 |

| rs12936587c | 17p11.2 | RASD1, SMCR3, PEMT | NT_010718.15 | A | G (0.56) | 1.07 | 4.9 × 10−7 | No | rs11871738 | 0.83 | 0.14 |

| rs46522c | 17q21.32 | UBE2Z, GIP, ATP5G1, SNF8 | NT_010783.14 | C | T (0.53) | 1.06 | 3.6 × 10−6 | No | rs962272 | 1.04 | 0.73 |

| rs1122608 | 19p13.2 | LDLR | NT_011295.10 | T | G (0.77) | 1.14 | 9.7 × 10−10 | No | rs3786725 | 0.81 | 0.17 |

| rs9982601 | 21q22.11 | MRPS6 | NT_011512.10 | C | T (0.15) | 1.18 | 4.2 × 10−10 | No | rs7278204 | 1.28 | 0.19 |

Abbreviation: Ref., reference.

Chromosome position according to NCBI Genome build 36.3.

Using SNAP (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/snap/ldsearchs.php).

Risk allele or representative proxy.

OR representing combined analysis CARDIoGRAM & replication cohort.5

Discussion

In this study, by using an extreme genetics approach, we aimed to fortify our statistical power to identify novel genetic risk variants for CHD. However, none of the suggestive findings were either confirmed in the second stage or reached the genome-wide significant threshold in a meta-analysis of all populations combined.

We expected to identify larger effect sizes in our GWA study, compared with traditional GWA studies on CHD, for two reasons. First, we studied genetic risk variants for CHD in a cohort of FH patients, and hypercholesterolemia is one of the most important risk factors for CHD. Based on Rothman's model of causation, one would expect that in the presence of similar environmental factors, risk variants in genes will be associated with larger outcome effects.6 Second, we applied an extreme selection approach. Therefore, the genetic contrast between cases and controls was expected to increase.18 This incremental contrast has been shown to increase the power in simulation studies in quantitative traits. The effect sizes found when selectively genotyping only the phenotypic extremes will be increased.18, 19, 20 Plomin suggested that common disorders could also be considered as quantitative traits, as risk on a common disease in the population could be regarded as a distribution of ‘polygenetic liability' to a disease. The extreme sampling approach should, therefore, produce larger effect sizes in our study as well. Thus, the power was expected to be relatively high, despite the reduction in number of individuals as a result of the selection criteria.18, 19, 21 Our study is the first to apply this method using real data. Using Quanto, we confirmed that the study was sufficiently powered to identify risk variants with large effect sizes in this high-risk group of subjects. Our findings, being more specific our odds ratios, indicate that the leverage in effect size using this approach is, in fact, quite modest. This is also clear from the data from CARDIoGRAM in our study, as an example, the well-replicated locus at 9p21.3 had an OR of 1.28, very close to the 1.25 value that was found in the original study of subjects from the general population. Most other known CHD risk SNPs identified in earlier studies and published by Schunkert et al5 were not associated with statistically significant effects in this FH sample. However, our study was underpowered for this analysis if the true effect sizes were the same as reported and less increased by our design than anticipated, so we can only look at the direction of the effect. Out of 18 SNPs that could be tested, 11 ORs were in the same direction, whereas only 6 were not (Table 4). Of these 11, most interesting was the SNP in PCSK9. This SNP is associated with an 8% higher risk of CHD in the general population; however, the odds in ARGOS were increased by >50%. Although the P-value in CARDIoGRAM did not reach genome-wide significance, it is tempting to speculate that this finding and the enhanced effect in ARGOS is not due to chance, but might reflect an interaction between this gene and cholesterol levels. PCSK9 is a gene encoding proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9, involved in the intracellular degradation of LDL receptors. PCSK9 levels correlated inversely with LDL cholesterol levels in FH patients.22 PCSK9 inhibitors are being tested in phase III trials23 now, and are expected to be highly effective in FH patients.24, 25

Our definition of extreme groups might have been too restrictive, as it constitutes a very small proportion of the FH sample (500 out of 17 000).

Nevertheless, our findings may help to understand why genetic risk prediction models have not yet succeeded. In our approach, we attempted to identify novel genes by selecting the extreme groups of the CHD risk distribution spectrum. Genetic risk prediction studies, on the other hand, start with genetic information and estimate who will end up in the low- and the high-risk group.26 As we could demonstrate that the effect sizes in this design are not as enlarged as we expected, the contrast needed for prediction might be less than anticipated as well: genetic risk factors most likely have a more gradual distribution over the population instead of being over- or underrepresented in the phenotypic extremes and the combination of classical and genetic risk factors defines the CHD risk.

Our approach has a number of limitations. Finding extreme cases is a challenging effort. Although FH is a relatively common genetic disorder, collecting a large sample of subjects either with early onset CHD or healthy aging is difficult. The low genomic inflation factor (1.01) in the total sample indicated that population admixture was not likely.27 We do realize that from a statistical point of view our sample size was not enough to detect genes with small effects. Another issue might be whether difference in age between cases and controls might bring in extra confounding. Although only Caucasian patients were studied, first and second degree family members were excluded and we had phenotypic data, we cannot exclude the presence of an unknown confounder. A last limitation of a GWA study in FH subjects is that the results may not necessarily apply to the general population.28 Results may be restricted to FH patients or to hypercholesterolemic patients in general. Also, it might be possible that CHD risk in the young is genetically different from CHD risk at an older age.

We conclude that the genetics of CHD risk in FH is complex and even applying an ‘extreme genetics' approach, we did not identify new genetic risk variants. Most likely, this method is not as effective in leveraging effect size as anticipated, and may, therefore, not lead to significant gains in statistical power. Also, this study might explain why genetic risk prediction modeling is yielding disappointment. The odds ratio associated with genetic variation at the PCSK9 locus points to important consequences for PCSK9 activity in FH patients and provides hope for the novel approach to lower these levels through monoclonal antibodies in order to prevent CHD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carl Jarman and David Gunn for help in sample preparation and data collection. CIBERobn is an initiative of ISCIII, Spain. This work was supported by the Dutch Heart Foundation (2006B190) and Unilever, UK. Additional funding was provided by Pfizer and MSD The Netherlands. SEH acknowledges BHF support (RG 2008/008) and also funding from the Department of Health's NIHR Biomedical Research Centre funding scheme. ER is supported by grant FIS PS09/01292 from ISCIII, Spain.

Professor Kastelein is a recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award of the Dutch Heart Foundation. Keith J Johnson was an employé of Pfizer in Groton, CT, USA. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2008 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117:e25–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peden JF, Farrall M. Thirty-five common variants for coronary artery disease: the fruits of much collaborative labour. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:R198–R205. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So HC, Gui AH, Cherny SS, Sham PC. Evaluating the heritability explained by known susceptibility variants: a survey of ten complex diseases. Genet Epidemiol. 2011;35:310–317. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathiresan S, Voight BF, Purcell S, et al. Genome-wide association of early-onset myocardial infarction with single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variants. Nat Genet. 2009;41:334–341. doi: 10.1038/ng.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schunkert H, Konig IR, Kathiresan S, et al. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:333–338. doi: 10.1038/ng.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Causation and causal inference in epidemiology. Am J Public Health. 2005;95 (Suppl 1:S144–S150. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs HH, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Molecular genetics of the LDL receptor gene in familial hypercholesterolemia. Hum Mutat. 1992;1:445–466. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380010602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MI, Abecasis GR, Cardon LR, et al. Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:356–369. doi: 10.1038/nrg2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umans-Eckenhausen MA, Defesche JC, Scheerder RL, Cline F, Kastelein JJ. [Tracing of patients with familial hypercholesterolemia in the Netherlands] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1999;143:1157–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen AC, van Aalst-Cohen ES, Hutten BA, Buller HR, Kastelein JJ, Prins MH. Guidelines were developed for data collection from medical records for use in retrospective analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen AC, van Aalst-Cohen ES, Tanck MW, et al. The contribution of classical risk factors to cardiovascular disease in familial hypercholesterolaemia: data in 2400 patients. J Int Med. 2004;256:482–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofman A, Breteler MM, van Duijn CM, et al. The Rotterdam Study: 2010 objectives and design update. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24:553–572. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9386-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgadottir A, Thorleifsson G, Manolescu A, et al. A common variant on chromosome 9p21 affects the risk of myocardial infarction. Science. 2007;316:1491–1493. doi: 10.1126/science.1142842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdmann J, Grosshennig A, Braund PS, et al. New susceptibility locus for coronary artery disease on chromosome 3q22.3. Nat Genet. 2009;41:280–282. doi: 10.1038/ng.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer G.The Meta Package wwwcranr-projectorg/src/contrib/Descriptions/rmetahtml , 2005

- Lumley T.The rmeta package http://wwwcranr-projectorg/src/contrib/Descriptions/rmetahtml , 2004

- Van Gestel S, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Adolfsson R, van Duijn CM, Van Broeckhoven C. Power of selective genotyping in genetic association analyses of quantitative traits. Behav Genet. 2000;30:141–146. doi: 10.1023/a:1001907321955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing C, Xing G. Power of selective genotyping in genome-wide association studies of quantitative traits. BMC Proc. 2009;3 (Suppl 7:S23. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-3-s7-s23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang BE, Lin DY. Efficient association mapping of quantitative trait loci with selective genotyping. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:567–576. doi: 10.1086/512727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, Haworth CM, Davis OS. Common disorders are quantitative traits. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:872–878. doi: 10.1038/nrg2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijgen R, Fouchier SW, Denoun M, et al. Plasma levels of PCSK9 and phenotypic variability in familial hypercholesterolemia. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:979–983. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P023994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom DJ, Hala T, Bolognese M, et al. A 52-week placebo-controlled trial of evolocumab in hyperlipidemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1809–1819. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1316222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH, Jr, Hobbs HH. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1264–1272. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjouke B, Kusters DM, Kastelein JJ, Hovingh GK. Familial hypercholesterolemia: present and future management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2011;13:527–536. doi: 10.1007/s11886-011-0219-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis JP. Prediction of cardiovascular disease outcomes and established cardiovascular risk factors by genome-wide association markers. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:7–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.833392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin B, Roeder K. Genomic control for association studies. Biometrics. 1999;55:997–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Net JB, Oosterveer DM, Versmissen J, et al. Replication study of 10 genetic polymorphisms associated with coronary heart disease in a specific high-risk population with familial hypercholesterolemia. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2195–2201. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.