The benefits of a photorespiratory bypass depend on its metabolic and chloroplast membrane diffusion properties.

Abstract

Bypassing the photorespiratory pathway is regarded as a way to increase carbon assimilation and, correspondingly, biomass production in C3 crops. Here, the benefits of three published photorespiratory bypass strategies are systemically explored using a systems-modeling approach. Our analysis shows that full decarboxylation of glycolate during photorespiration would decrease photosynthesis, because a large amount of the released CO2 escapes back to the atmosphere. Furthermore, we show that photosynthesis can be enhanced by lowering the energy demands of photorespiration and by relocating photorespiratory CO2 release into the chloroplasts. The conductance of the chloroplast membranes to CO2 is a key feature determining the benefit of the relocation of photorespiratory CO2 release. Although our results indicate that the benefit of photorespiratory bypasses can be improved by increasing sedoheptulose bisphosphatase activity and/or increasing the flux through the bypass, the effectiveness of such approaches depends on the complex regulation between photorespiration and other metabolic pathways.

In C3 plants, the first step of photosynthesis is the fixation of CO2 by ribulose bisphosphate (RuBP). For every molecule of CO2 fixed, this reaction produces two molecules of a three-carbon acid, i.e., 3-phosphoglycerate (PGA), and is catalyzed by the Rubisco enzyme. A small portion of the carbon in PGA is used for the production of Suc and starch, whereas the remainder (i.e. five-sixths) is used for the regeneration of RuBP (Fig. 1). The regeneration of the Rubisco substrate RuBP in the Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) cycle ensures that ample RuBP is available for carbon fixation (Bassham, 1964; Wood, 1966; Beck and Hopf, 1982). Rubisco is a bifunctional enzyme that catalyzes not only RuBP carboxylation but also RuBP oxygenation (Spreitzer and Salvucci, 2002). RuBP oxygenation generates only one molecule of PGA and one molecule of 2-phosphoglycolate (P-Gly; Ogren, 1984). The photorespiratory pathway converts this P-Gly back to RuBP in order to maintain the CBB cycle.

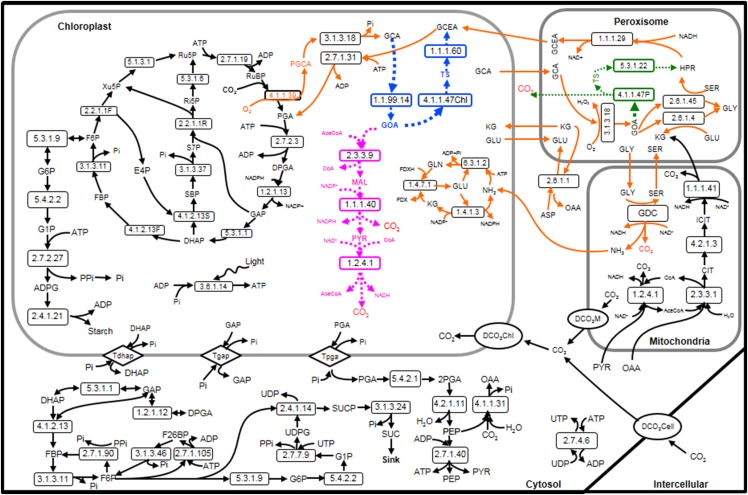

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the C3 photosynthesis kinetic model with three different photorespiratory bypass pathways. The bypass described by Kebeish et al. (2007) is indicated in blue, the bypass described by Maier et al. (2012) in pink, and the bypass described by Carvalho et al. (2011) in green. The original photorespiratory pathway is marked in orange, and CO2 released from photorespiration (including the original pathway and bypass pathways) is indicated in red. 2PGA, 2-Phosphoglyceric acid; ASP, Asp; CIT, citrate; ICIT, isocitrate; PGA, 3-phosphoglycerate; DPGA, glycerate-1,3-bisphosphate; GAP, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; SBP, sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphate; S7P, sedoheptulose-7-phosphate; Ri5P, ribose-5-phosphate; Ru5P, ribulose-5-phosphate; FBP, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase; F6P, fructose 6-phosphate; Xu5P, xylulose-5-phosphate; G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; G1P, glucose-1-phosphate; ADPG, ADP-glucose; F26BP, fructose-2,6-bisphosphate; UDPG, uridine diphosphate glucose; SUCP, sucrose-6F-phosphate; SUC, Suc; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; OAA, oxaloacetate; PGCA, phosphoglycolate; GCA, glycolate; GOA, glyoxylate; GCEA, glycerate; MAL, malate; PYR, pyruvate; GLU, glutamate; KG, alfa-ketoglutarate; GLN, Gln; HPR, hydroxypyruvate; RuBP, ribulose bisphosphate; SER, Ser; GLY, Gly; TS, tartronic semialdehyde.

In higher plants, P-Gly is dephosphorylated to glycolate, which is transferred into the peroxisomes, where it is oxidized to hydrogen peroxide and glyoxylate. Then, glyoxylate is aminated to produce Gly, which is subsequently transferred to the mitochondria. There, two molecules of Gly are converted into one Ser plus one CO2 and one NH3 (Ogren, 1984; Peterhansel et al., 2010). The Ser is ultimately converted back to PGA (Tolbert, 1997). CO2 and NH3 are gasses that can escape to the atmosphere (Sharkey, 1988; Kumagai et al., 2011), and the loss of carbon and nitrogen essential for biomass accumulation will decrease the efficiency of photosynthesis and plant growth (Zhu et al., 2010). Fortunately, both substances are partially reassimilated in the chloroplast, but this results in decreased photosynthetic energy efficiency. At 25°C and current atmospheric CO2 concentrations, approximately 30% of the carbon fixed in C3 photosynthesis may be lost via photorespiration and the size of this loss increases with temperature (Sharkey, 1988; Zhu et al., 2010). As a result, photorespiration has been regarded as a pathway that could be altered to improve photosynthetic efficiency (Zelitch and Day, 1973; Oliver, 1978; Ogren, 1984; Zhu et al., 2008, 2010).

There are several approaches that may be used to alter photorespiration to improve photosynthetic efficiency. First, it might be possible to increase the specificity of Rubisco to CO2 versus oxygen (Sc/o; Dhingra et al., 2004; Spreitzer et al., 2005; Whitney and Sharwood, 2007). However, previous studies have shown that there is an inverse correlation between Sc/o and the maximum carboxylation rate of Rubisco (Jordan and Ogren, 1983; Zhu et al., 2004), and there are some indications that the Sc/o of different organisms may be close to optimal for their respective environments (Tcherkez et al., 2006; Savir et al., 2010). Second, a CO2-concentrating mechanism could be engineered into C3 plants. For example, introducing cyanobacterial bicarbonate transporters (Price et al., 2011) or introducing C4 metabolism could be used to concentrate CO2 in the vicinity of Rubisco and, thereby, suppress the oxygenation reaction of Rubisco (Furbank and Hatch, 1987; Mitchell and Sheehy, 2006). Past efforts to introduce a C4 pathway into C3 plants have focused on biochemical reactions related to C4 photosynthesis without taking into account the anatomical differences between C3 and C4 plants, which may have been responsible for the limited success of such endeavors (Fukayama et al., 2003). Recently, there has been renewed interest in engineering C4 photosynthetic pathways into C3 plants, with efforts focusing on understanding and engineering the genetic regulatory network related to the control of both the anatomical and biochemical properties related to C4 photosynthesis (Mitchell and Sheehy, 2006; Langdale, 2011).

Transgenic approaches have been used to knock down or knock out enzymes in the photorespiratory pathway. Unfortunately, the inhibition of photorespiration by the deletion or down-regulation of enzymes in the photorespiratory pathway resulted in a conditional lethal phenotype (i.e. such plants cannot survive under ambient oxygen and CO2 concentrations but may be rescued by growing them under low-oxygen or high-CO2 conditions; for review, see Somerville and Ogren, 1982; Somerville, 2001). Another approach to reduce photorespiration is to block (or inhibit) enzymes in this pathway using chemical inhibitors. Zelitch (1966, 1974, 1979) reported that net photosynthesis increased by inhibiting glycolate oxidase or glycolate synthesis. However, other groups showed that the inhibition of glycolate oxidase or Gly decarboxylation led to the inhibition of photosynthesis (Chollet, 1976; Kumarasinghe et al., 1977; Servaites and Ogren, 1977; Baumann et al., 1981). It turns out that plants cannot efficiently metabolize photorespiratory intermediates without a photorespiratory pathway, and suppression of this pathway inhibits the recycling of carbon back toward RuBP, which is necessary for maintaining the CBB cycle (Peterhansel et al., 2010; Peterhansel and Maurino, 2011). Moreover, the accumulation of toxic metabolic intermediates (e.g. P-Gly) can strongly inhibit photosynthesis (Anderson, 1971; Kelly and Latzko, 1976; Chastain and Ogren, 1989; Campbell and Ogren, 1990). This may explain why earlier attempts to block or reduce photorespiration have failed to improve carbon gain.

Instead of reducing photorespiration directly, a promising idea is to engineer a photorespiratory bypass pathway. Such a pathway would metabolize P-Gly produced by RuBP oxygenation but minimize carbon, nitrogen, and energy losses and avoid the accumulation of photorespiratory intermediates. Kebeish et al. (2007) introduced the glycolate catabolic pathway from Escherichia coli into Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana); we will subsequently call this type of bypass the Kebeish bypass. In such transgenic plants, glycolate is converted to glycerate in the chloroplasts without ammonia release (Fig. 1). Previous studies suggested that this pathway theoretically requires less energy and shifts CO2 release from mitochondria to chloroplasts (Peterhansel and Maurino, 2011; Peterhansel et al., 2013); experimental results indicated that the bypass allowed for increased net photosynthesis and biomass production in Arabidopsis (Kebeish et al., 2007). There are reports of two other photorespiratory bypass pathways in the literature (Carvalho, 2005; Carvalho et al., 2011; Maier et al., 2012). In the Carvalho bypass (Carvalho, 2005; Carvalho et al., 2011), glyoxylate is converted to hydroxypyruvate in the peroxisome. Similar to the Kebeish bypass, the ammonia release is abolished, one-quarter of the carbon from glycolate is released as CO2 in the peroxisomes, and three-quarters of the carbon from glycolate is converted back to PGA. However, this pathway has only been partially realized in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum); that is, the enzyme of the second reaction of this pathway was not detectable in the transgenic plants, and plants expressing this pathway showed stunted growth when grown in ambient air (Carvalho et al., 2011). The Maier bypass (Maier et al., 2012) is characterized by complete oxidation of glycolate in the chloroplasts. Initial results suggested that the photosynthesis and biomass of transgenic Arabidopsis with this pathway were enhanced (Maier et al., 2012).

Recently, the design and benefits of the three bypass pathways were reviewed (Peterhansel et al., 2013), and it was suggested that a photorespiratory bypass can contribute to an enhanced photosynthetic CO2 uptake rate by lowering energy costs and minimizing carbon and nitrogen losses. However, a systematic and quantitative analysis of the potential contributions of these different factors to photosynthesis improvement has not yet been conducted. Systems modeling can help to design new metabolic pathways and improve our understanding of biochemical mechanisms (McNeil et al., 2000; Wendisch, 2005; Zhu et al., 2007; Bar-Even et al., 2010; Basler et al., 2012). Such models have been used successfully to gain insight into the photosynthetic metabolism (Laisk et al., 1989, 2006; Laisk and Edwards, 2000; Zhu et al., 2007, 2013; Wang et al., 2014). In this study, we use an extended kinetic model of C3 photosynthesis based on earlier work by Zhu et al. (2007) to systematically analyze the potential of three photorespiratory bypass pathways for improving photosynthetic efficiency (Supplemental Model S1). In addition, we determined under what conditions such bypass pathways may lead to increased photosynthesis and biomass production in C3 plants and how to further improve the photosynthesis of plants with such a bypass. Our analysis suggests that the benefit of a photorespiratory bypass varies dramatically if it is engineered into different crops.

RESULTS

We first extended the kinetic model of C3 photosynthesis (Zhu et al., 2007) by incorporating the ATP cost of NH3 refixation, CO2 diffusion in the mesophyll, and part of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (Fig. 1). This model can predict the response of photosynthetic CO2 uptake rate to intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) and to light intensity (Fig. 2). Using default model parameters (Supplemental Tables S1–S3), the predicted rate of CO2 release by photorespiration at ambient CO2 partial pressures (38.5 Pa; Ci = 27 Pa, which corresponds to a CO2 concentration of 9 µm in the liquid phase) is about 38% of the net CO2 assimilation (Supplemental Table S4), which is comparable to previous reports (Gerbaud and Andre, 1987; Sharkey, 1988).

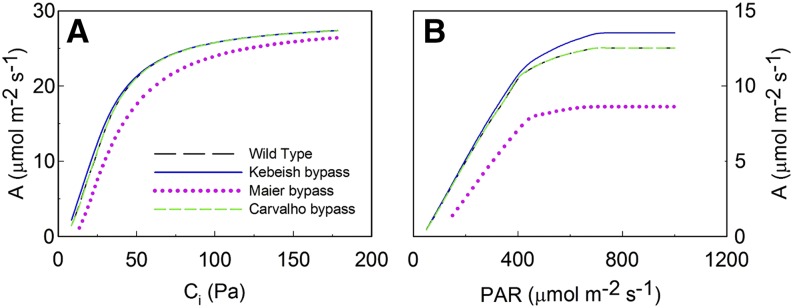

Figure 2.

Simulated CO2 response curves (A; where A = photosynthetic CO2 uptake rate) under saturating light conditions (photosynthetically active radiation [PAR] = 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1) and light response curves (B) under ambient CO2 conditions (Ci = 27 Pa; 9 µm in the liquid phase) for wild-type and bypass plants.

We further modified the C3 primary metabolism model to evaluate the effects of three photorespiratory bypass pathways on the net photosynthetic rate. To this end, we added three different bypass pathways to the model. In Figure 1, the normal C3 metabolism and the three photorespiratory bypass pathways are shown.

The responses of photosynthesis to different intercellular CO2 concentrations and light intensities were estimated using the kinetic model for wild-type and bypass plants. The results suggested that the Kebeish bypass pathway could enhance photosynthesis (Fig. 2; Supplemental Fig. S1), whereas the Maier bypass pathway decreased the photosynthetic rate. The Carvalho bypass pathway did not affect the photosynthetic rate under the tested conditions (Fig. 2; Supplemental Fig. S1).

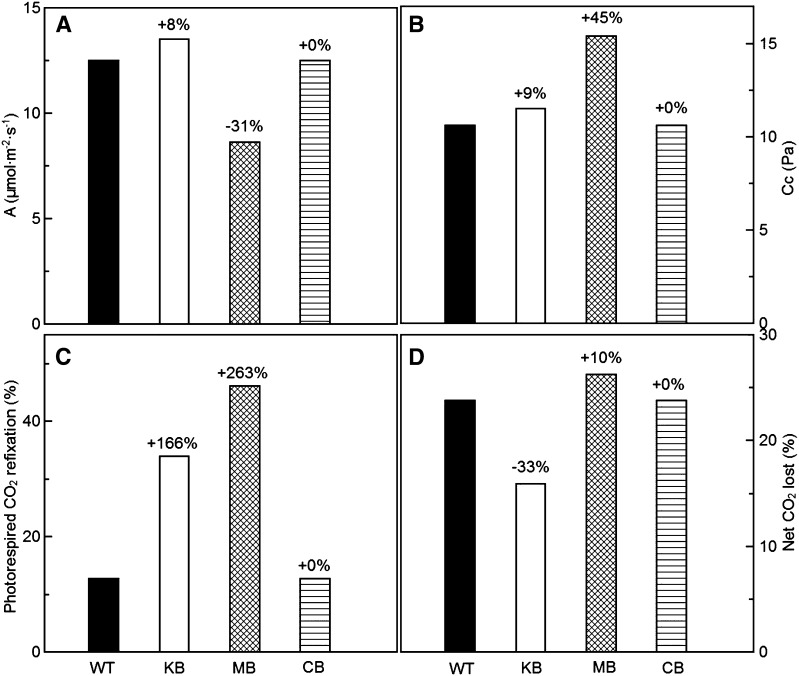

Specifically, our model indicated that, compared with wild-type controls, chloroplast CO2 concentrations and the amount of photorespired CO2 that is refixed by Rubisco are increased in plants expressing the Kebeish or Maier bypass (Fig. 3). At saturating light and at ambient CO2 levels, the results using the default parameterization (Supplemental Tables S1–S3) suggested that the photosynthetic rate of plants expressing the Kebeish bypass is about 8% higher than that of wild-type plants (Fig. 3A). However, the photosynthetic rate predicted for plants expressing the Maier bypass was 31% lower than that of the wild type (Fig. 3A). The photosynthetic rate of plants with the Carvalho bypass was indistinguishable from that of the wild type (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

A, Simulated photosynthetic rates (where A = photosynthetic CO2 uptake rate). B, Partial pressure of CO2 inside the chloroplasts (Cc). C, Percentage of (photo)respired CO2 that is refixed. D, Flux of CO2 lost to the atmosphere relative to the total CO2 fixation rate of wild-type (WT) and bypass plants with the default parameters. CB, Carvalho bypass; KB, Kebeish bypass; MB, Maier bypass. Ci = 27 Pa (corresponds to 9 µm in the liquid phase), and PAR = 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1.

To explore why the photosynthetic rate was not predicted to increase in plants expressing the Carvalho bypass, or why it even decreased in plants with the Maier bypass, we examined the fluxes through the bypasses and normal photorespiratory pathways in detail. In contrast to the situation in the wild type and in plants expressing the Kebeish bypass, where only part of the carbon (25%) in glyoxylate is released as CO2, plants expressing the Maier bypass release all carbons of glyoxylate as CO2. Indeed, the flux of CO2 that escapes to the atmosphere relative to the total CO2 fixation rate dramatically increased in the model with a Maier bypass, while it was decreased in the Kebeish bypass (Fig. 3D). Mainly as a result of the high Km for glyoxylate of glyoxylate carboligase (EC 4.1.1.47), the flux through the Carvalho bypass pathway was extremely low (Supplemental Table S5).

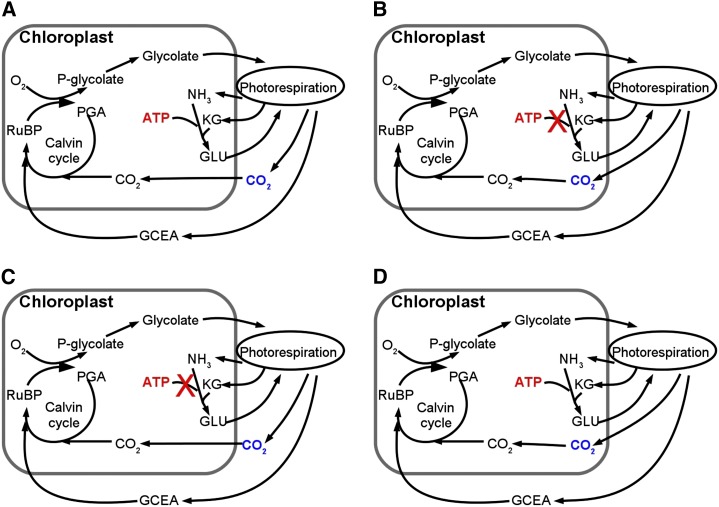

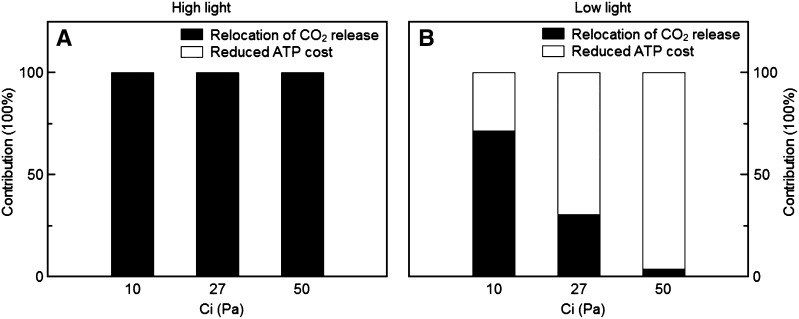

To understand why plants expressing the Kebeish bypass have higher rates of photosynthesis, we separately examined the contributions of avoiding ammonium loss and of relocating photorespiratory CO2 release from mitochondria to chloroplast. Models representing three different hypothetical scenarios were constructed. The first scenario was similar to that with a Kebeish bypass, in that photorespiratory CO2 release was relocated from mitochondria to chloroplasts and no ammonium was released by photorespiration (i.e. no ATP is needed for the refixation of released ammonia). However, in contrast to the plants expressing the Kebeish bypass, where part of the photorespiratory flux still goes through the normal photorespiratory pathway, these effects were applied to 100% of the flux (Fig. 4B). In the second scenario, all release of photorespiratory CO2 was relocated to the chloroplasts, but ammonium was still released by photorespiration and refixed as in the wild type (Fig. 4C). For the third scenario, CO2 was released in the mitochondria as in the wild type but no ammonium was released by photorespiration (Fig. 4D). Again, for all three scenarios, we assumed that the flux through the normal photorespiration pathway was zero. Simulations show that, under high light, the increase of the photosynthetic rate can be fully attributed to the relocation of CO2 release from mitochondria to chloroplasts (Fig. 5A). Under low light, these lower ATP costs contributed to an enhanced photosynthesis, especially at higher CO2 concentrations (Fig. 5B). Therefore, under low light and ambient or high CO2 concentrations, the enhanced photosynthesis of bypass plants can be mainly attributed to the lower ATP costs of the bypass plant compared with a plant with the normal photorespiratory pathway (Fig. 5). However, the benefit of lower ATP costs was rather small (Supplemental Table S6).

Figure 4.

A, The wild-type pathway. B, A photorespiratory pathway that does not use ATP for the refixation of ammonia and relocates CO2 release into the chloroplasts. C, A photorespiratory pathway that does not use ATP for the refixation of ammonia. D, A scenario where only the CO2 release has been relocated from mitochondria to chloroplasts. GCEA, Glycerate; KG, α-ketoglutarate.

Figure 5.

The relative contribution of abolishing the energy cost for ammonia refixation (white bars) and relocating photorespiratory CO2 release into chloroplasts (black bars) on the change in the rate of photosynthesis in bypass under different light intensities and CO2 partial pressures when all the flux goes through the bypass. For high light (A), PAR = 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1; for low light (B), PAR = 200 μmol m−2 s−1.

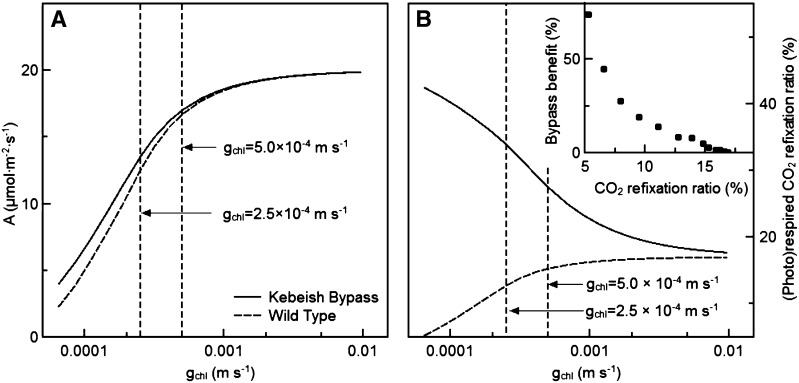

The conductance of CO2 between the cytosol and the site of fixation in the chloroplast stroma (gchl) may influence the effect of relocating the site of CO2 release from mitochondria to chloroplasts. Therefore, we tested the effect of changing gchl on photosynthetic rates of the wild type and the bypass. In bypass and wild-type plants, increasing gchl would also increase the overall conductance of CO2 between the atmosphere and the Rubisco enzyme, resulting in higher photosynthetic rates (Fig. 6A). In addition, in wild-type plants, such an increase in gchl would also allow a greater amount of (photo)respired CO2 to be refixed by Rubisco (Fig. 6B). By contrast, in bypass plants, where CO2 is released inside the chloroplast stroma, increasing gchl would allow for more CO2 to escape from the stroma and, thus, lower the amount of photorespiratory CO2 that can be refixed. This would result in a much greater effect of the bypass on photosynthesis in plants with a low gchl compared with plants with a high gchl (Fig. 6). For example, doubling the default gchl increased the photosynthetic rate of the wild type by 34%, but at the same time it decreased the benefit of the bypass to photosynthesis to only 1.8% (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

The predicted effects of gchl on photosynthesis (A; where A = photosynthetic CO2 uptake rate) and on the percentage of (photo)respired CO2 that is refixed (B) for wild-type plants (dashed lines) and plants expressing a Kebeish bypass (continuous lines). The relationship between the predicted CO2 refixation ratio and bypass benefit is shown in the inset in B. Ci = 27 Pa (9 µm in the liquid phase), and PAR = 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1.

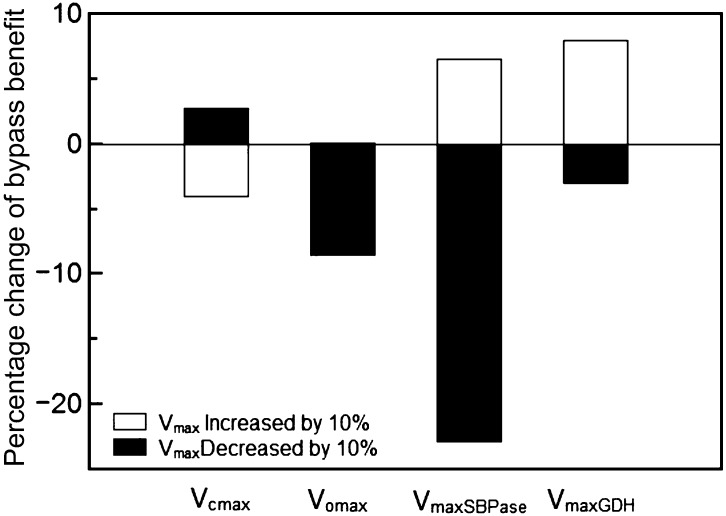

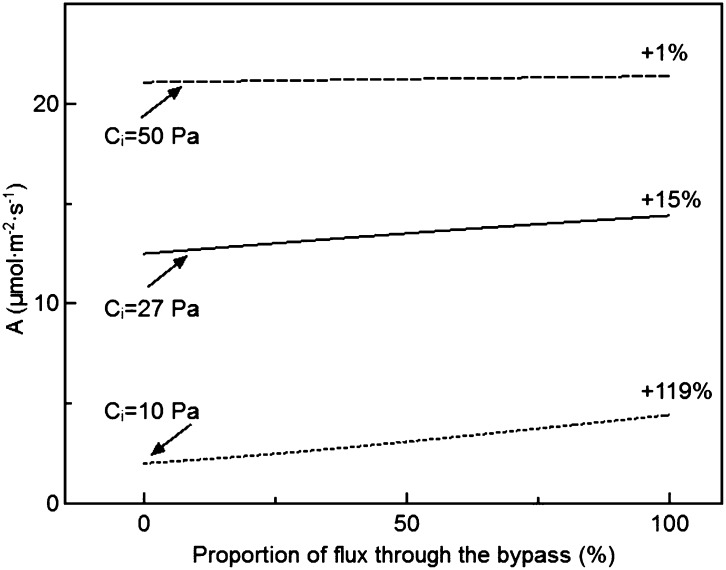

We further explored whether the effect of the Kebeish bypass on photosynthetic rate depends on enzyme activities used in the model. To this end, we systematically increased and decreased each enzyme’s capacity (Vmax) by 10% and simulated the corresponding photosynthetic rates. All of these simulations were conducted with the default parameters listed in Supplemental Tables S1 to S3. The results show that increasing Rubisco carboxylation capacity decreased the effect of the bypass, whereas increasing Rubisco oxygenation, sedoheptulose bisphosphatase (SBPase), or glycolate dehydrogenase (GDH) capacity increased the benefit effect of the bypass (Fig. 7). Increasing GDH capacity led to an increased flux through the bypass pathway, which enhanced the benefit effect of the bypass (Fig. 8; Supplemental Fig. S2). Under ambient conditions, if all photorespiratory flux was forced through the Kebeish bypass (by blocking the flux through the normal photorespiration pathway), the photosynthetic rate could be enhanced by 15% (Fig. 8) under the default conditions listed in Supplemental Tables S1 to S3. The capacities of all the other enzymes in our model had no significant effect on the benefit of the Kebeish bypass (Supplemental Table S7).

Figure 7.

The effects of changing the maximal activity (Vmax) of different enzymes on the estimated benefit of the Kebeish bypass to photosynthesis. Vcmax is the maximum carboxylation capacity of Rubisco, Vomax is the maximum oxygenation capacity Rubisco, VmaxSPBase is the maximum capacity of SBPase, and VmaxGDH is the maximum capacity of GDH. Ci = 27 Pa (9 µm in the liquid phase), and PAR = 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1.

Figure 8.

The predicted benefit to photosynthesis of the proportion of the photorespiratory flux through the Kebeish bypass relative to the total oxygenation rate at three different CO2 levels. PAR = 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1. A, Photosynthetic CO2 uptake rate.

DISCUSSION

Engineering a bypass for photorespiration is regarded as a promising approach to increase photosynthesis and plant productivity (Peterhansel and Maurino, 2011; Peterhansel et al., 2013). So far, there are only a few experimental studies suggesting that the photosynthetic rate may be increased as a result of the introduction of photorespiratory bypasses (Kebeish et al., 2007; Maier et al., 2012). This study systematically evaluated different photorespiratory bypass strategies using a systems and synthetic biology approach. Our results indicated that under certain conditions, a photorespiratory bypass can indeed increase photosynthesis by up to 8%. Such an effect may seem small, but it will, as a result of exponential growth rates, result in large differences in biomass over time and significantly improve a plant’s competitive ability (Givnish, 1986; Kirschbaum, 2011). We showed that reduced energy cost by avoiding ammonium refixation and an increase in the refixation of photorespiratory CO2 as a result of releasing CO2 inside the chloroplasts contributed to the enhancement of photosynthesis. We further demonstrated that the permeability of the chloroplast envelopes and the activities of key enzymes can influence the potential benefit of the photorespiratory bypass pathway.

The Benefit of Different Bypass Strategies to Photosynthesis

Similar to the normal photorespiration pathway, the Kebeish-pathway releases 0.5 mol of CO2 for every 1 mol of glyoxylate produced. However, in the bypass, CO2 is released in the chloroplast stroma instead of in mitochondria (Kebeish et al., 2007). This shift in the site of CO2 release can potentially increase the CO2 concentration in the chloroplast stroma, resulting in a reduced RuBP oxygenation rate. In addition, the relocation of the CO2 release to the chloroplast stroma also improves the refixation of photorespiratory CO2, improving the CO2 fixation rate (Peterhansel et al., 2013). The release and refixation of NH3, which occurs during normal photorespiration, are avoided in this bypass pathway. Thus, this bypass also has the potential benefit of reducing ATP costs associated with carbon assimilation (Kebeish et al., 2007; Maurino and Peterhansel, 2010; Peterhansel et al., 2010, 2013). Since all these features could enhance photosynthesis, we evaluated their relative magnitude and dependence on physiological characteristics and environmental conditions. Our simulations suggested that, under high light, the enhanced photosynthesis in bypass plants can be completely attributed to the relocation of the CO2 release from mitochondria to chloroplasts. By contrast, under low light, the reduced ATP cost as a result of the absence of ammonium refixation also contributed to an improved photosynthetic efficiency.

In agreement with experimental observations (Kebeish et al., 2007), our simulations showed that, compared with the wild type, the Kebeish bypass results in higher photosynthetic rates under a range of CO2 and light conditions (Fig. 2). The chloroplast CO2 concentration and the amount of photorespiratory CO2 that is refixed by Rubisco also were predicted to be increased in plants containing such a bypass (Fig. 3). However, in contrast to experimental observations suggesting that transgenic plants only show an enhanced biomass under low-light growth conditions (Kebeish et al., 2007), our modeled results indicated that photosynthetic rates in bypass plants also could be enhanced, even to a greater extent, under high light (Fig. 2B). This discrepancy between experiment and simulation may be caused by model simplifications of the photosynthetic pathway. In particular, the effect of redox signaling (Foyer et al., 2009; Foyer and Noctor, 2009) and the inhibition of glyoxylate on Rubisco activation (Campbell and Ogren, 1990) are not included in the current model. In this respect, it is worthwhile to note that both the redox state and the chloroplast glyoxylate concentrations of bypass plants are different from those of wild-type controls (Kebeish et al., 2007; Maurino and Peterhansel, 2010; Peterhansel and Maurino, 2011). Under high light, such effects would be enhanced as a result of increased photorespiration rates and may explain the difference between modeled and experimental results.

The bypass pathway described by Maier et al. (2012) also shifts the photorespiratory CO2 release from mitochondria into chloroplasts, and it was suggested that chloroplast CO2 concentrations increased (Peterhansel et al., 2010, 2013). In contrast to experimental observations that such transgenic plants show an enhanced photosynthetic rate (Maier et al., 2012), our simulation predicted a reduced photosynthetic rate in plants with the Maier bypass (Fig. 3A). This may be explained by the fact that 2 mol of CO2 is released per 1 mol of glyoxylate in the Maier bypass (an 8-fold increase compared with the release in a normal photorespiratory pathway; for review, see Peterhansel and Maurino, 2011). Our results indicated that the amount of photorespiration that is lost to the atmosphere relative to the CO2 fixation rate is increased dramatically in Maier bypass plants (Fig. 3D), suggesting that the benefit of an increased chloroplast CO2 concentration cannot fully compensate for the loss of CO2 in this bypass pathway.

In the pathway described by Carvalho (2005) and Carvalho et al. (2011), a bypass was implemented in the peroxisome and NH3 release is avoided; hence, the energy necessary for NH3 refixation is saved. The lower energy cost in such a bypass has potential benefits for photosynthesis (for review, see Peterhansel et al., 2013). Our simulation results suggested that lowering ATP costs during photorespiration may enhance the photosynthesis under low light intensity (Fig. 5; Supplemental Table S6). However, simulations of the Carvalho bypass indicated that the photosynthetic rate in plants with this bypass was not substantially different from that of controls even under low-light conditions (Fig. 2B), in agreement with experimental results (Carvalho et al., 2011). Further analysis suggested that the lack of an effect was the result of an extremely low reaction flux through this bypass pathway (Supplemental Table S5). The reaction flux of this bypass pathway was limited by the glyoxylate carboligase activity, especially by the high Km for glyoxylate (Supplemental Table S5). Increasing the proportion of photorespiratory fluxes through the bypass by modifying the kinetic parameters of glyoxylate carboligase in this pathway slightly increased photosynthetic rates of bypass plants under low light intensity (Supplemental Table S5). This was expected because completely abolishing ATP cost for NH3 fixation resulted in an enhancement of photosynthesis of only 4.6% under low-light conditions (Supplemental Table S6). Since experimental results have indicated that the expression of some of the bypass enzymes was low or absent (Carvalho et al., 2011), a low flux through this bypass may explain the lack of a significant effect on photosynthesis in the transgenic plants.

Mechanisms Underlying Enhanced Photosynthesis in Plants Expressing the Kebeish Bypass

As mentioned in the previous section, plants with a Kebeish bypass benefit from a lower ATP cost for ammonia refixation and from shifting the site of photorespiratory CO2 release into the chloroplasts. The relative contribution of these factors to the improvement of photosynthesis is still unknown (Peterhansel and Maurino, 2011; Peterhansel et al., 2013).

Peterhansel et al. (2013) suggested that the benefit of the relocation of photorespiratory CO2 release in the bypass plant may strongly depend on the amount of photorespiratory CO2 that is released and subsequently refixed. If photorespiratory CO2 release by the mitochondria results in a relatively large flux of CO2 escaping to the atmosphere instead of being refixed by Rubisco, the introduction of a bypass that shifts CO2 release into the chloroplasts may increase refixation and, therefore, photosynthesis. The amount of CO2 that escapes from the leaf to the atmosphere depends on the resistance between the site of CO2 release and the atmosphere and on the resistance between the site of CO2 release and the site of CO2 fixation. The most important factor that controls this last resistance is the permeability of the chloroplast envelopes to CO2 (Evans et al., 2009). Most C3 photosynthetic models implicitly assumed that the chloroplast envelopes offer no significant resistance to diffusion and that the only barrier to refixation is the relatively slow turnover rate of Rubisco itself (Tholen et al., 2012b). This ignores the fact that current experimental estimates of the permeability of isolated chloroplast envelopes in Arabidopsis put it at much lower values (2 × 10−5 m s−1; Uehlein et al., 2008), although it must be emphasized that considerable uncertainty surrounds these values (i.e. about 4 orders of magnitude; Evans et al., 2009; Kaldenhoff et al., 2014). As explained by Tholen et al. (2012a, 2012b), estimates of the effective in vivo resistances are not only a result of the membrane permeability itself but also take into account the structural arrangement of the organelles in the cell. For example, in rice (Oryza sativa), more than 95% of the cell periphery is covered by chloroplast or chloroplast extrusions, forcing CO2 to exit the cells via chloroplasts. Such a cellular anatomy will increase the effective gchl, and this may explain the relatively large amount of photorespiratory CO2 (up to 38% at a CO2 concentration of 20 Pa, which corresponds to a CO2 concentration of 6.6 µm in the liquid phase) that can be refixed in such leaves (Busch et al., 2013).

Because the presence of the Kebeish bypass resulted in increased CO2 concentrations inside the chloroplast stroma (Fig. 3B), the gchl was expected to affect the leakage of photorespired CO2 from chloroplast to cytosol and, correspondingly, the potential enhancement to photosynthesis by the photorespiratory bypass. In our simulations, we used a value for gchl of 2.5 × 10−4 m s−1, which is between the estimate by Uehlein et al. (2008; 1.85 × 10−5 m s−1) and that by Evans et al. (2009; 3.5 × 10−3 m s−1; Fig. 6A). To account for the uncertainty in these values, we tested how our model predictions depended on the magnitude of gchl. The results indicated that, although the photosynthetic rate of both wild-type and bypass plants increase with an increase in gchl, the advantage of the bypass over wild-type plants decreased with an increase in gchl (Fig. 6A). If gchl is doubled (5 × 10−4 m s−1), the photosynthesis of the wild type increased dramatically; however, the positive effect of the bypass on photosynthesis was decreased by a factor of 4. Nevertheless, even with such a large gchl, the bypass may still be beneficial to photosynthesis under low-CO2 conditions (Supplemental Fig. S2).

We further examined the effects of gchl on the amount of photorespired CO2 that was refixed by Rubisco in wild-type and bypass plants. Our analysis shows that in wild-type plants, the refixation ratio increased with an increase in gchl, whereas the refixation ratio of bypass plants gradually decreased with an increase in gchl (Fig. 6B). The benefit of the photorespiratory bypass to photosynthesis gradually decreased with an increase in the CO2 refixation ratio of wild-type plants. When about 30% of the photorespired CO2 can be refixed, as is the case under current atmospheric conditions in species like wheat (Triticum aestivum) and rice (Busch et al., 2013), the effect of the bypass was negligible (Fig. 6). Given these results, it seems unlikely that introducing a photorespiratory bypass would be beneficial for enhancing the rate of photosynthesis in such species.

How Can the Effect of a Photorespiratory Bypass Be Increased?

The simulations using our systems model suggested that, under ambient conditions, the bypass only has significant benefits when gchl is relatively low (Fig. 6). In fact, such a low gchl would be somewhat suboptimal for photosynthesis, and engineering plants with a higher gchl may allow for a greater enhancement of photosynthesis compared with introducing a bypass. However, it is possible that the biochemical composition of the chloroplast envelope prevents such highly permeable chloroplast envelopes (Kaldenhoff et al., 2014). Our findings highlight the need to obtain more reliable estimates for the permeability of chloroplast membranes to CO2.

We analyzed whether the photosynthesis of bypass plants could be further enhanced by altering the activities of enzymes in the photosynthetic metabolism. Our simulations showed that changing the maximal activity of GDH, SBPase, and Rubisco influenced the benefit of the Kebeish bypass for photosynthesis (Fig. 7), while changing the capacity of other enzymes in our model has virtually no effect (Supplemental Table S7). A number of earlier reports suggested that increasing SBPase concentration can improve photosynthetic energy conversion efficiency (Lefebvre et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2007; Rosenthal et al., 2011). If the relative activities of these different enzymes used in the model were not altered in the photorespiratory bypass plant, then the overexpression of SBPase will, in theory, also improve the photosynthetic CO2 uptake rate. The default flux through the Kebeish bypass in our model was about equal to the flux through the normal photorespiratory pathway. We found that the GDH enzyme in this bypass is rate limiting for the flux, and increasing the maximal activity of GDH leads to an increased flux through the Kebeish bypass and an enhanced rate of photosynthesis (Fig. 8; Supplemental Fig. S3). By contrast, increasing the flux through the Maier bypass by increasing the maximal activity of GDH leads to a decreased photosynthetic rate as a result of the large amount of CO2 that would be lost (Supplemental Fig. S4). The benefit of the bypass also was increased when the Rubisco carboxylation capacity decreased or the Rubisco oxygenation capacity increased (Fig. 7). However, such changes of the Rubisco kinetics would result in lower photosynthetic rates for both wild-type and bypass plants (Supplemental Table S7). It is worth emphasizing here that the actual benefit of the proposed targets for manipulation to gain increased photosynthesis in the bypass plants will be dependent on the existing activities of enzymes in the bypass plants. Once enzyme activities of all those involved enzymes can be measured, the modeling framework presented here can be used to determine the precise targets for engineering for increased efficiency.

CONCLUSION

Using a systems model, this study demonstrated that photorespiratory bypasses can increase carbon assimilation under specific conditions. Based on this theoretical analysis, not all previously described bypasses are expected to be functional or beneficial to photosynthesis. Relocation of the photorespiratory CO2 release from mitochondria into chloroplast and reducing energy costs by avoiding ammonium release were shown to be the main factors that contribute to an improved photosynthetic efficiency. The gchl greatly influences the potential benefit of a photorespiratory bypass. Specifically, the benefit of a bypass is expected to decrease with an increase in gchl. Given the scarcity and uncertainty of the available estimates for membrane permeability, it remains difficult to predict whether introducing a bypass is a viable approach to optimize photosynthetic rates in crop species. The photorespiratory pathway may interact closely with many other pathways, such as nitrogen metabolism, respiration, and mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism (for review, see Ogren 1984; Foyer et al., 2009; Bauwe et al., 2010). More research on unraveling the regulatory networks controlling the association between photorespiration and other biochemical pathways is needed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Model Development

We extended the photosynthetic carbon metabolism model developed by Zhu et al. (2007) by incorporation of a more detailed description of the light reaction, CO2 diffusion, ammonia refixation during photorespiration, and dark respiration (Fig. 1). In addition, some of the parameters (e.g. enzyme activities) were updated based on the literature. The default values for all parameters used in the current model are listed in Supplemental Tables S1 and S2. Here, we briefly describe the reactions that were added to the model.

Light Reactions

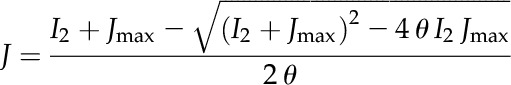

We assumed that the electron transport rate is much faster than the biochemical reactions of carbon fixation such as the CBB cycle. Therefore, we based the light reaction in the kinetic model on the steady-state biochemical description by von Caemmerer (2000). The relationship between the electron transport and the absorbed irradiance was described using an empirical equation (Ogren and Evans, 1993; von Caemmerer, 2000):

|

(1) |

where I2 is the light (μmol m−2 s−1) absorbed by PSII, Jmax is the maximal electron transport rate, and θ is an empirical curvature factor (default value is 0.7; von Caemmerer, 2000). J is the electron transport rate (μmol m−2 s−1) that is directly related to the rate of ATP synthesis in the model as described below. I2 is related to incident irradiance I by:

|

(2) |

where α is the leaf absorptance (default value is 0.85; von Caemmerer, 2000), f corrects for the spectral quality of the light (default value is 0.15; Evans, 1987), and the 2 in the denominator indicates that 50% of the light is absorbed by each photosystem.

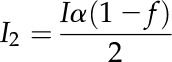

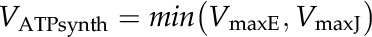

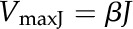

The maximum rate of ATP synthesis is described as:

|

(3) |

where VmaxE (μmol m−2 s−1) is the maximum rate of ATP synthesis reactions determined by the enzyme kinetics and VmaxJ (μmol m−2 s−1) is the maximum rate of ATP synthesis reactions limited by the electron transport rate:

|

(4) |

where J is the electron transport rate (in μmol m−2 s−1) calculated by the steady-state model (Eq. 1). β is the ATP:e− ratio. By assuming that the H+:ATP ratio is 4, and assuming that protons are generated through the whole electron transport chain with the Q cycle through cytochrome b6f, the default value of β used in our model is 0.75 (von Caemmerer, 2000). The NADPH concentration is assumed to be a constant in the current model.

CO2 Diffusion

The diffusion of CO2 from intercellular airspaces to the site of fixation in the chloroplasts forms a significant limitation to photosynthesis in C3 plants (Evans et al., 2009). Since some photorespiratory bypasses release CO2 in other cellular compartments than in wild-type plants, the effects of the diffusion within the cell have to be taken into account by our model. Tholen and Zhu (2011) described this diffusion on a subcellular level using a reaction-diffusion model, but such a detailed approach is beyond the scope of this work. However, the diffusion of CO2 between the different compartments of the biochemical model were explicitly considered using conductances. To calculate the contribution of CO2 mass transfer between different organelles on the biochemical fluxes, we added to following rate equation for each compartment:

|

(5) |

where S is the surface area of a compartment (i.e. chloroplast, cytosol, or mitochondrion), Vol is the volume of the compartment, g is the conductance for CO2 (through the cell wall and plasmalemma, chloroplast envelopes, or mitochondrial envelopes), and ΔCO2 is the CO2 concentration difference between two compartments.

Calculation of the CO2 Refixation Ratio

CO2 released by photorespiration can escape to the atmosphere or be refixed by Rubisco in the chloroplasts and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPc) in the cytosol. To quantify the amount of refixation, Tholen et al. (2012b) defined the refixation ratio as the flux of refixed (photo)respired CO2 relative to the total flux of CO2 that is released from respiration and photorespiration. We used individual identifiers for (photo)respiratory and atmospheric CO2 in the model; this allowed us to distinguish between the flux of CO2 that was released by (photo)respiration and subsequently refixed by Rubisco or PEPc (FR) and the flux of CO2 released from respiration and photorespiration (Frelease):

|

(6) |

The net flux of CO2 that is lost to the atmosphere as a result of photorespiration (FL) relative to the CO2 fixation rate by Rubisco (FRubisco) and PEPc (FPEPC) is:

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

Implementation of Three Different Photorespiratory Bypass Pathways

Three different models representing different photorespiratory bypass pathways were implemented. We refer to the pathways described by Kebeish et al. (2007), Maier et al. (2012), and Carvalho et al. (2011) as the Kebeish bypass, the Maier bypass, and the Carvalho bypass, respectively. The different pathways are described in Figure 1. The Kebeish bypass converts glycolate into glycerate in the chloroplast, and CO2 is released in the chloroplast stroma instead of in the mitochondria. The Maier bypass consists of glycolate dehydrogenase, malate synthase, malic enzyme, and pyruvate dehydrogenase. This pathway allows for the complete decarboxylation of glycolate, and the resulting CO2 is released in the chloroplast stroma. In the Carvalho bypass, CO2 is released in the peroxisome instead of in mitochondria or chloroplasts.

The metabolites and reactions used by the different photorespiratory bypass pathways were added to the Zhu et al. (2007) model (Fig. 1). The initial concentrations of metabolites and the kinetic parameters used in our model are listed in Supplemental Tables S1 and S3. The reaction rates of the additional enzymes are described using Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Supplemental Equations S1).

Analysis of Three Scenarios to Study the Mechanisms Underlying Increased Photosynthesis in the Kebeish Bypass Pathway

Peterhansel et al. (2013) suggested several characteristic features of photorespiratory bypasses that can explain why such bypasses can achieve a higher rate of photosynthesis and growth. To quantitatively analyze such features, we designed three theoretical scenarios that captured features of photorespiratory bypasses (Fig. 2). These theoretical scenarios enable us to test whether photosynthesis enhancement in the bypass plants was due to reduced ATP cost for photorespiration or was a consequence of releasing CO2 inside the chloroplast stroma instead of in mitochondria. In the first scenario, we assumed that CO2 was released in chloroplasts and that there was also no ATP cost for NH3 refixation in the chloroplast (Fig. 4B). In the second scenario, we assumed that CO2 was released in mitochondria but there was no ATP cost for NH3 refixation in the chloroplast (Fig. 4C). For the third scenario, we assumed that the CO2 was released inside chloroplasts but NH3 was released and its refixation in the chloroplast required ATP (Fig. 4D). The first scenario is similar to the situation in which all photorespiratory flux would enter the Kebeish bypass pathway, the second scenario examines the effect of reduced ATP costs, and the third scenario tests whether releasing photorespiratory CO2 in the chloroplast instead of in mitochondria has an effect on photosynthesis.

The Benefit of a Photorespiratory Bypass to Photosynthesis

The benefit of a photorespiratory bypass to photosynthesis was defined as the percentage of increase in photosynthetic rates in plants with a photorespiratory bypass pathway compared with the wild type:

|

(9) |

where Abypass is the photosynthetic rate of a plant with a photorespiratory bypass pathway and Awt is the photosynthetic rate of the wild type.

Our model is built with the Simbiology Toolbox provided by MATLAB (version 2008a; MathWorks). The sundials solver of Simbiology was chosen to solve the system. The solution of the ordinary differential equations provided by sundials provides the time series changes of each metabolite in every compartment, which in turn were used to calculate reaction fluxes.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Simulated photosynthetic rate of wild type and different bypass pathways under multiple combinations of light intensity and CO2 concentrations.

Supplemental Figure S2. Simulated CO2 response curves (PAR = 1000 μmol m−2 s−1) and light response curves (Ci = 27 Pa) of wild type and the bypass described by Kebeish et al. (2007).

Supplemental Figure S3. The predicted effect of GDH activity (VmaxGDH) on the proportion of photorespiratory flux through the Kebeish bypass pathway and the photosynthetic rate of Kebeish bypass.

Supplemental Figure S4. The predicted effect of GDH activity (VmaxGDH) on the proportion of photorespiratory flux through the Maier bypass pathway and the photosynthetic rate of the Maier bypass.

Supplemental Table S1. Enzyme kinetic parameters used in the model.

Supplemental Table S2. Initial values of metabolite concentrations used in the model.

Supplemental Table S3. Additional parameters used in the model.

Supplemental Table S4. Predicted photosynthesis of wild type plants under ambient conditions.

Supplemental Table S5. The effects of glyoxylate carboligase and hydroxypyruvate isomerase enzyme parameters on the photosynthetic rate and on the proportion of the photorespiratory fluxes through the Carvalho bypass under low light conditions.

Supplemental Table S6. The photosynthetic rate predicted for several hypothetical scenarios based on the Kebeish pathway.

Supplemental Table S7. Effect of variation in the maximal enzyme activity (Vmax) on the photosynthetic rates of wild type and Kebeish bypass plants under ambient conditions.

Supplemental Equations S1. Equations used in the systems models.

Supplemental Model S1: The model used in the study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Yu Wang and Jeroen Van Rie for comments on the article.

Glossary

- RuBP

ribulose bisphosphate

- PGA

3-phosphoglycerate

- CBB

Calvin-Benson-Bassham

- P-Gly

2-phosphoglycolate

- Sc/o

specificity of Rubisco to CO2 versus oxygen

- Ci

intercellular CO2 concentration

- gchl

conductance of CO2 between the cytosol and the site of fixation in the chloroplast stroma

- SBPase

sedoheptulose bisphosphatase

- GDH

glycolate dehydrogenase

- PEPc

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase

- PAR

photosynthetically active radiation

Footnotes

This work was supported by Bayer CropScience, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Max Planck Society, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation project Realizing Improved Photosynthetic Efficiency (grant no. OPP1060461).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Anderson LE. (1971) Chloroplast and cytoplasmic enzymes. II. Pea leaf triose phosphate isomerases. Biochim Biophys Acta 235: 237–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Even A, Noor E, Lewis NE, Milo R (2010) Design and analysis of synthetic carbon fixation pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 8889–8894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler G, Grimbs S, Nikoloski Z (2012) Optimizing metabolic pathways by screening for feasible synthetic reactions. Biosystems 109: 186–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassham J. (1964) Kinetic studies of the photosynthetic carbon reduction cycle. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 15: 101–120 [Google Scholar]

- Baumann G, Balfanz J, Gunther G (1981) Inhibitory effects of alpha-hydroxypyridine methane sulfonate (HPMS) on net photosynthesis of Beta vulgaris (sugar beet) and Chenopodium album. Biochem Physiol Pflanz 176: 423–438 [Google Scholar]

- Bauwe H, Hagemann M, Fernie AR (2010) Photorespiration: players, partners and origin. Trends Plant Sci 15: 330–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck E, Hopf H (1982) Carbohydrate metabolism. In H Ellenberg, K Esser, K Kubitzki, E Schnepf, H Ziegler, eds, Progress in Botany (Fortschritte der Botanik) SE - 7. Springer, Berlin, pp 132–153 [Google Scholar]

- Busch FA, Sage TL, Cousins AB, Sage RF (2013) C3 plants enhance rates of photosynthesis by reassimilating photorespired and respired CO2. Plant Cell Environ 36: 200–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell WJ, Ogren WL (1990) Glyoxylate inhibition of ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activation in intact, lysed, and reconstituted chloroplasts. Photosynth Res 23: 257–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho JdFC (2005) Manipulating carbon metabolism to enhance stress tolerance (short circuiting photorespiration in tobacco). PhD thesis. University of Lancaster, Lancaster, UK [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho JdeF, Madgwick PJ, Powers SJ, Keys AJ, Lea PJ, Parry MA (2011) An engineered pathway for glyoxylate metabolism in tobacco plants aimed to avoid the release of ammonia in photorespiration. BMC Biotechnol 11: 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chastain CJ, Ogren WL (1989) Glyoxylate inhibition of ribulosebisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activation state in vivo. Plant Cell Environ 30: 937–944 [Google Scholar]

- Chollet R. (1976) Effect of glycidate on glycolate formation and photosynthesis in isolated spinach chloroplasts. Plant Physiol 57: 237–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra A, Portis AR Jr, Daniell H (2004) Enhanced translation of a chloroplast-expressed RbcS gene restores small subunit levels and photosynthesis in nuclear RbcS antisense plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 6315–6320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR. (1987) The dependence of quantum yield on wavelength and growth irradiance. Aust J Plant Physiol 14: 69–79 [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, Kaldenhoff R, Genty B, Terashima I (2009) Resistances along the CO2 diffusion pathway inside leaves. J Exp Bot 60: 2235–2248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Bloom AJ, Queval G, Noctor G (2009) Photorespiratory metabolism: genes, mutants, energetics, and redox signaling. Annu Rev Plant Biol 60: 455–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Noctor G (2009) Redox regulation in photosynthetic organisms: signaling, acclimation, and practical implications. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 861–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukayama H, Hatch MD, Tamai T, Tsuchida H, Sudoh S, Furbank RT, Miyao M (2003) Activity regulation and physiological impacts of maize C(4)-specific phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase overproduced in transgenic rice plants. Photosynth Res 77: 227–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furbank RT, Hatch MD (1987) Mechanism of C4 photosynthesis: the size and composition of the inorganic carbon pool in bundle sheath cells. Plant Physiol 85: 958–964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbaud A, Andre M (1987) An evaluation of the recycling in measurements of photorespiration. Plant Physiol 83: 933–937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givnish TJ, editor (1986) On the Economy of Plant Form and Function: Proceedings of the Sixth Maria Moors Cabot Symposium, Evolutionary Constraints on Primary Productivity, Adaptive Patterns of Energy Capture in Plants, Harvard Forest, August 1983. Cambridge University Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- Jordan DB, Ogren WL (1983) Species variation in kinetic properties of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Arch Biochem Biophys 227: 425–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaldenhoff R, Kai L, Uehlein N (2014) Aquaporins and membrane diffusion of CO2 in living organisms. Biochim Biophys Acta 1840: 1592–1595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebeish R, Niessen M, Thiruveedhi K, Bari R, Hirsch HJ, Rosenkranz R, Stäbler N, Schönfeld B, Kreuzaler F, Peterhänsel C (2007) Chloroplastic photorespiratory bypass increases photosynthesis and biomass production in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Biotechnol 25: 593–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly GJ, Latzko E (1976) Inhibition of spinach-leaf phosphofructokinase by 2-phosphoglycollate. FEBS Lett 68: 55–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum MUF. (2011) Does enhanced photosynthesis enhance growth? Lessons learned from CO2 enrichment studies. Plant Physiol 155: 117–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai E, Araki T, Hamaoka N, Ueno O (2011) Ammonia emission from rice leaves in relation to photorespiration and genotypic differences in glutamine synthetase activity. Ann Bot (Lond) 108: 1381–1386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumarasinghe KS, Keys AJ, Whittingham CP (1977) Effects of certain inhibitors on photorespiration by wheat leaf segments. J Exp Bot 28: 1163–1168 [Google Scholar]

- Laisk A, Edwards GE (2000) A mathematical model of C(4) photosynthesis: the mechanism of concentrating CO(2) in NADP-malic enzyme type species. Photosynth Res 66: 199–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laisk A, Eichelmann H, Oja V (2006) C3 photosynthesis in silico. Photosynth Res 90: 45–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laisk A, Eichelmann H, Oja V, Eatherall A, Walker DA (1989) A mathematical model of the carbon metabolism in photosynthesis: difficulties in explaining oscillations by fructose 2,6-bisphosphate regulation. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 237: 389–415 [Google Scholar]

- Langdale JA. (2011) C4 cycles: past, present, and future research on C4 photosynthesis. Plant Cell 23: 3879–3892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre S, Lawson T, Zakhleniuk OV, Lloyd JC, Raines CA (2005) Increased sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase activity in transgenic tobacco plants stimulates photosynthesis and growth from an early stage in development. Plant Physiol 138: 451–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier A, Fahnenstich H, von Caemmerer S, Engqvist MKM, Weber APM, Flügge UI, Maurino VG (2012) Transgenic introduction of a glycolate oxidative cycle into A. thaliana chloroplasts leads to growth improvement. Front Plant Sci 3: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurino VG, Peterhansel C (2010) Photorespiration: current status and approaches for metabolic engineering. Curr Opin Plant Biol 13: 249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil SD, Rhodes D, Russell BL, Nuccio ML, Shachar-Hill Y, Hanson AD (2000) Metabolic modeling identifies key constraints on an engineered glycine betaine synthesis pathway in tobacco. Plant Physiol 124: 153–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PL, Sheehy JE (2006) Supercharging rice photosynthesis to increase yield. New Phytol 171: 688–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogren E, Evans JR (1993) Photosynthetic light-response curves. I. The influence of CO2 partial pressure and leaf inversion. Planta 189: 182–190 [Google Scholar]

- Ogren WL. (1984) Photorespiration: pathways, regulation and modification. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 35: 415–442 [Google Scholar]

- Oliver DJ. (1978) Inhibition of photorespiration and increase of net photosynthesis in isolated maize bundle sheath cells treated with glutamate or aspartate. Plant Physiol 62: 690–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterhansel C, Blume C, Offermann S (2013) Photorespiratory bypasses: how can they work? J Exp Bot 64: 709–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterhansel C, Horst I, Niessen M, Blume C, Kebeish R, Kürkcüoglu S, Kreuzaler F (2010) Photorespiration. The Arabidopsis Book 8: e0130, doi/10.1199/tab.0130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterhansel C, Maurino VG (2011) Photorespiration redesigned. Plant Physiol 155: 49–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price GD, Badger MR, von Caemmerer S (2011) The prospect of using cyanobacterial bicarbonate transporters to improve leaf photosynthesis in C3 crop plants. Plant Physiol 155: 20–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal D, Locke A, Khozaei M, Raines C, Long S, Ort DR (2011) Over-expressing the C3 photosynthesis cycle enzyme Sedoheptulose-1-7 Bisphosphatase improves photosynthetic carbon gain and yield under fully open air CO2 fumigation (FACE). BMC Plant Biology 11: 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savir Y, Noor E, Milo R, Tlusty T (2010) Cross-species analysis traces adaptation of Rubisco toward optimality in a low-dimensional landscape. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 3475–3480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servaites JC, Ogren WL (1977) Chemical inhibition of the glycolate pathway in soybean leaf cells. Plant Physiol 60: 461–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD. (1988) Estimating the rate of photorespiration in leaves. Physiol Plant 73: 147–152 [Google Scholar]

- Somerville CR. (2001) An early Arabidopsis demonstration: resolving a few issues concerning photorespiration. Plant Physiol 125: 20–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville CR, Ogren WL (1982) Genetic modification of photorespiration. Trends Biochem Sci 7: 171–174 [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer RJ, Peddi SR, Satagopan S (2005) Phylogenetic engineering at an interface between large and small subunits imparts land-plant kinetic properties to algal Rubisco. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 17225–17230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer RJ, Salvucci ME (2002) Rubisco: structure, regulatory interactions, and possibilities for a better enzyme. Annu Rev Plant Biol 53: 449–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez GGB, Farquhar GD, Andrews TJ (2006) Despite slow catalysis and confused substrate specificity, all ribulose bisphosphate carboxylases may be nearly perfectly optimized. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 7246–7251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholen D, Boom C, Zhu XG (2012a) Opinion: prospects for improving photosynthesis by altering leaf anatomy. Plant Sci 197: 92–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholen D, Ethier G, Genty B, Pepin S, Zhu XG (2012b) Variable mesophyll conductance revisited: theoretical background and experimental implications. Plant Cell Environ 35: 2087–2103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholen D, Zhu XG (2011) The mechanistic basis of internal conductance: a theoretical analysis of mesophyll cell photosynthesis and CO2 diffusion. Plant Physiol 156: 90–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolbert NE. (1997) The C2 oxidative photosynthetic carbon cycle. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 48: 1–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehlein N, Otto B, Hanson DT, Fischer M, McDowell N, Kaldenhoff R (2008) Function of Nicotiana tabacum aquaporins as chloroplast gas pores challenges the concept of membrane CO2 permeability. Plant Cell 20: 648–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S. (2000) Biochemical Models of Leaf Photosynthesis. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Australia, pp 29–71 [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Long SP, Zhu XG (2014) Elements required for an efficient NADP-malic enzyme type C4 photosynthesis. Plant Physiol 164: 2231–2246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendisch V. (2005) Towards improving production of fine chemicals by systems biology: amino acid production by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Chimica Oggi-Chemistry Today 23: 49–52 [Google Scholar]

- Whitney SM, Sharwood RE (2007) Linked Rubisco subunits can assemble into functional oligomers without impeding catalytic performance. J Biol Chem 282: 3809–3818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood WA. (1966) Carbohydrate metabolism. Annu Rev Biochem 35: 521–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelitch I. (1966) Increased rate of net photosynthetic carbon dioxide uptake caused by the inhibition of glycolate oxidase. Plant Physiol 41: 1623–1631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelitch I. (1974) The effect of glycidate, an inhibitor of glycolate synthesis, on photorespiration and net photosynthesis. Arch Biochem Biophys 163: 367–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelitch I. (1979) Photosynthesis and plant productivity. Chem Eng News 57: 28–48 [Google Scholar]

- Zelitch I, Day PR (1973) The effect on net photosynthesis of pedigree selection for low and high rates of photorespiration in tobacco. Plant Physiol 52: 33–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XG, de Sturler E, Long SP (2007) Optimizing the distribution of resources between enzymes of carbon metabolism can dramatically increase photosynthetic rate: a numerical simulation using an evolutionary algorithm. Plant Physiol 145: 513–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XG, Long SP, Ort DR (2008) What is the maximum efficiency with which photosynthesis can convert solar energy into biomass? Curr Opin Biotechnol 19: 153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XG, Long SP, Ort DR (2010) Improving photosynthetic efficiency for greater yield. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61: 235–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XG, Portis R, Long SP (2004) Would transformation of C3 crop plants with foreign Rubisco increase productivity? A computational analysis extrapolating from kinetic properties to canopy photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ 27: 155–165 [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XG, Wang Y, Ort DR, Long SP (2013) e-Photosynthesis: a comprehensive dynamic mechanistic model of C3 photosynthesis: from light capture to sucrose synthesis. Plant Cell Environ 36: 1711–1727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.